ABSTRACT

Measures to control the COVID-19 pandemic have disrupted social networks and employment security worldwide. Longitudinal data in representative samples are required to understand the corresponding mental health impacts. We aimed to estimate the prevalence of depressive symptoms in Australian women raising young families during the first Victorian lockdown and to identify risk factors. Participants comprise 347 mothers of children aged 7 (mean age: 32·11 years [4·27]), from the Barwon Infant Study (BIS). Mothers had previously completed Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) at child ages zero, two, four. Following the lock down, mothers again completed EPDS along with questions regarding current household and employment demographics. Depressive symptoms were substantially more prevalent in the lockdown sample than at any prior assessment (EPDS10+; 30·6%); and were particularly high in women with previous poor mental health. Anticipated and actual job loss were twice as common relative to previous assessment (5% to 13%, p = 0 006) and (4% to 10%, p = 0 001) and were associated with depressive symptoms. While further studies are required to confirm causal associations, these findings highlight the need to support mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic, particularly in the context of employment insecurity and previous mental illness.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Emerging reports from convenience samples demonstrate elevated depressive symptoms during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Maternal mental health is important for child mental health.

Representative, longitudinal data are needed to further improve targeting of policy and health service delivery to prevent a post-COVID-19 mental health crisis.

What this topic adds:

This early report from a population-derived cohort demonstrates high rates of depression symptomatology in mothers of school aged children following the first COVID-19 lockdown.

A past history of depression and current threats to employment are identified as key risk factors for adverse mental health.

Our findings are consistent with concerns regarding an increase in mental health burden in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic but further studies are required to assess causality. Interventions and broader community resources to support the mental health of women of school aged children are required, and should target those with a history of depression and current threats to employment.

There is widespread concern about a possible “mental health tsunami” resulting from the unprecedented lockdown measures taken globally to combat the spread of COVID-19 (Royal College of Psychiatrists, Citation2020; Tsirtsakis, Citation2020). Physical distancing measures in particular have disrupted social networks which are central to emotional regulation and social connection (Aida et al., Citation2013). Lockdown has also had profound consequences on economic security which also plays a key role in mental health (Ribeiro et al., Citation2017).

The mental health impacts of the resulting disrupted family and broader social networks, job losses, economic uncertainty, increased childcare commitments and social isolation are likely to be considerable. Emerging evidence suggests disproportionate mental health burden in groups with pre-existing mental health problems (Institute, Citation2020) and also in women (Wenham et al., Citation2020). Given finite resources, representative, longitudinal data are urgently needed to guide government policy and health service delivery to those most in need of support during this pandemic.

Here we report data on the mental health profile in mothers of primary school aged children participating in the Barwon Infant Study (BIS), which is a large, birth cohort recruited using an unselected antenatal sampling frame in southern Victoria, Australia (Vuillermin et al., Citation2015). The aims of the study were: (1) to estimate the prevalence of maternal depressive symptoms, including thoughts of self-harm, during the first lockdown in Australia and (2) to identify those most at risk of poor mental health across the pandemic on the basis of depression in the postnatal period and contemporaneous contextual factors.

Methods

Participants

The Barwon Infant Study (n = 1074) is a longitudinal birth cohort study recruited 2010–2012 with serial questionnaires in sequential reviews (antenatal, four weeks, two years, four years and seven to eight years – current) with recruitment from two hospitals capturing 90% of births in a geographic catchment area, the demographics of which is representative of the broader Australian population (Vuillermin et al., Citation2015). Here, participants comprise 347 mothers (mean age: 32·11 years [4·27]), who represent the first third (32·3%) of the Barwon Infant Study inception cohort to respond to the 2020 online questionnaires, during the period 29th April to 22 May 2020.

Pandemic lockdown context

The Stage 2 lockdown associated with the first wave of COVID-19 infection in Australia commenced in Victoria on 24 March 2020. It required all Australians to stay at home unless necessary to access goods or services, for care or compassionate reasons, to attend work or education where not possible by remote work/learning, and for socially distanced outdoor exercise (Sutton, Citation2020). There was widespread closure of non-essential recreational, cultural and entertainment venues. The Australian government introduced the JobKeeper program on 30th of March to support part-time and full-time workers in certain sectors affected by the lockdown.

Measures

Depressive Symptoms: The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) (Cox et al., Citation1987) was administered at birth, four weeks, two years, four years and seven to eight years (the current review). A cut point of 10+was used to indicate pre-clinical (mild) depressive symptoms (Edmondson et al., Citation2010) and 13+ was used to indicate a high likelihood of depression (positive predictive value of 70–90%) (Buist et al., Citation2002). Both cut-points have been validated in an Australian sample (Buist et al., Citation2002; Eastwood et al., Citation2011; Matthey et al., Citation2006). The EPDS has demonstrated validity and use in mothers of older children; none of the items are specific to the postnatal period (Cox et al., Citation1996; Woolhouse et al., Citation2015).

Self-Harm: Given the context of a life-threatening pandemic, we specifically examined women’s responses to the single EPDS item: “The thought of harming myself has occurred to me”. We further examined this in combination with a score of 13 or above on the EPDS.

Current Household and Social Context: As listed in , BIS has detailed pre-pandemic data on household characteristics (e.g., number of adults and children in the house; living with the biological father; parental employment), social support (i.e., contact with extended family and friends), parental stress and substance use, and the occurrence of major life events in the previous 12 months (e.g., serious illness, injury and death; employment and financial upheaval, adapted from the Social Readjustment Rating Scale (Holmes & Rahe, Citation1967)). Sociodemographic factors at conception are described in and were used for backweighted adjustment by inverse probability weighting.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of 2020 review sample and inception cohort

Table 2. Subgroup analyses of current EPDS scores by past depressive symptoms

Table 3. Univariate associations between EPDS scores and household, family, community and employment characteristics

Statistical analysis

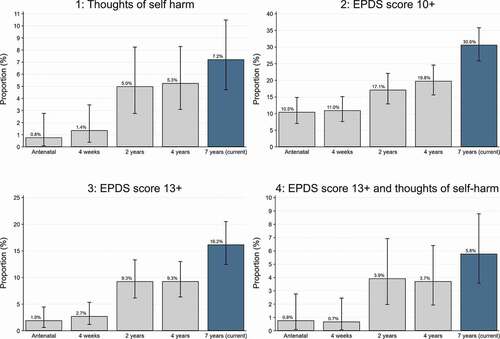

We show the proportion of mothers reporting (1) thoughts of self-harm (EPDS Item 10), (2) EPDS 10+, (3) EPDS 13+, and (4) thoughts of self-harm with EPDS 13+. To assess any potential selection bias in the respondent sample included in this report, we also present results unadjusted as well as backweighted using inverse probability weighting (Little & Rubin, Citation2019). Backweighting was done in terms of age, history of asthma (a primary outcome of interest in the BIS cohort during recruitment), socio-economic disadvantage of postcode, remoteness of postcode and household size. We have used the same weights in our previous work (Allen et al., Citation2013) see Supplementary Figure 1 for the distribution of inverse probability weights used. All estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals

To examine the potential role of previous mental health difficulties, we assessed associations between previous postnatal depressive symptoms (no elevated score, elevated at two or four years, elevated at both two and four years) and the current EPDS score.

To examine the potential role of current context, we assessed associations between household, family, community and employment characteristics relevant to the pandemic and depression, adjusting for an EPDS 10+at the two year or four year reviews (termed past depressive symptoms).

Binomial regression was used to estimate risk ratios for the four dichotomous depression outcomes, prior mental health status, and contemporary contextual factors and major life events such as job loss (Wacholder, Citation1986). Population attributable fractions (Greenland & Drescher, Citation1993) were calculated for associations between major life events that had (i) increased in prevalence from child age four to age seven-eight, and were also (ii) associated with depressive symptoms in .

Table 4. Major life events that increased in prevalence at 7 year review

Results

outlines the sociodemographic characteristics of the 2020 review sample and the inception cohort at birth. While they are similar in most respects, the current lockdown sample had a higher proportion of mothers with university level education (63% vs 51%), were less likely to live in a disadvantaged postcode, and had fewer older siblings in the house at birth than the full inception cohort. Questionnaires were completed an average of 42 days (SD: 6 days) since lockdown began. No families reported positive COVID-19 tests.

Increased prevalence of depressive symptoms in the current review

Depressive symptoms were more prevalent in the current lockdown sample than at any prior wave of assessment (antenatal, four week, two year or four year reviews), with 30.6% (95% CI: 25·8–35·8) of the sample scoring EPDS 10+and 16·2% (95% CI: 12·5–20·5) scoring EDPS 13+ (Panels 2 and 3, ). Furthermore, thoughts of self-harm were present in 7.2% (95% CI: 4··7–10·5) of the sample (Panel 1, ). Thus, there was a high burden of depressive symptoms and 1 in 14 had thoughts of self-harm.

Previous mental health difficulties, demographic and lockdown characteristics associated with elevated depressive symptoms

At child age seven to eight years, coinciding with lockdown, 56·5% (95% CI: 34·5–76·8) of the respondents who had past depressive symptoms at two prior timepoints reported current symptom burden concordant with diagnosable depression (EPDS score 13+), compared to 11·5% (95% CI: 7·3–16·8) of those who did not have past depressive symptoms (p < 0 · 001). Those with past depressive symptoms were therefore more likely to have depressive symptoms in the 2020 lockdown. See for subgroup analyses of current symptoms by past depressive symptoms.

Of the household and related social contextual factors considered, an important factor was living with the biological father (of the child/ren), associated with reduced risk of EPDS 10+ (RR 0·42, 95% CI: 0·35–0·50, p < 0 · 001), with weaker evidence of associations with EPDS 13+and thoughts of self-harm (RR 0.59, 95% CI: 0.33–1.05, p = 0.07; RR 0.45, 95% CI 0.18–1.10, p = 0.08). The numbers of other household residents were not significantly associated with EPDS score. The death of a “parent, partner or child” or “close family friend or relative” were both strongly associated with EPDS 10+ (RR 2·83, 95% CI: 1.18–7.68, p = 0.02; RR 1·43, 1.04–1.96, p = 0.03), however these associations were not consistent across EPDS 13+and thoughts of self-harm, or following adjustment for backweighting.

The prevalence of recent adverse life events, particularly pertaining to employment or finance increased from child age four to age seven-eight. The proportion of respondents concerned about imminent job loss more than doubled (5% to 13%, p = 0 · 006) as did the proportion who had already lost their jobs (4% to 10%, p = 0 · 002; see ). Most respondents stated that these two employment-related events had occurred due to COVID-19 (73% and 80%, respectively). Both threat of job loss and actual job loss were positively associated with EPDS 13+ (RR 2·23, 95% CI: 1·34–3·68, p = 0 · 002; RR 2·10, 95% CI: 1·25–3.53, p = 0 · 005; respectively) and with thoughts of self-harm (RR 5·25, 95% CI: 2·26–12·19, p < 0.001; 3·39, 1·54–7·45, p = 0 · 002, respectively). The population attributable fractions from these employment factors indicate that the impacts on depression could be considerable (threat of job loss: 15.29%, 95% CI: 2.95–26.06; actual job loss: 9.79, 95% CI: 0.61–18.12) although the estimates are imprecise. Overall, as expected, depressive symptoms were positively associated with higher perceived stress scores.

Backweighting by inverse probability weighting did not materially change the estimates of prevalence, subgroup analyses or associations with current household, social and adverse life events characteristics reported here, with the exception of death of a “parent, partner or child” or “close family friend or relative” (Supplementary Tables 1–4).

Discussion

Our results indicate that around one in three mothers with primary school aged children experienced elevated pre-clinical depressive symptomology (EPDS 10+), close to 2 in 10 (16%) experienced more severe depression (EDPS 13+), and 1 in 14 experienced thoughts of self-harm. There are no published data on depression in mothers of early primary school aged children, from prior to and/or during the pandemic, with which our results can be compared. This limits our capacity to infer that the observed increase in adverse maternal mental health is in fact caused by the COVID-19 lockdown.

At more severe clinical levels of depression, as indicated by EPDS 13+scores, the prevalence we report is similar to that reported in the pre-COVID literature. The most comparable estimates come from a large, population-based Australian study conducted in 2014 which reported approximately 14% of first-time mothers had EPDS scores of 13+when their children were four-years old, and again when their children were ten (using the equivalent cut-off score on the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale at this later follow-up) (Brown et al., Citation2020; Woolhouse et al., Citation2015). The prevalence of EDPS 13+scores in parents of primary school aged children during lockdown was only marginally higher (16·2%). However, we observed a clear increase between the four and the seven-eight year reviews for both pre-clinical and clinical level symptoms and a parallel increase in adverse life events such as job insecurity, indicating a potential effect of the COVID-19 lockdown. Nonetheless, it is impossible to make robust causal inferences in the absence of counterfactual data i.e., measures conducted among women who were not exposed to the COVID-19 lockdown. Of particular importance to clinical services planning, more than half of those who had previously experienced depressive symptoms reported depressive symptoms concordant with diagnosable depression following the lockdown.

Of the household, social and adverse life events factors we considered, currently living with the biological father of the child/ren was protective. Threats to job security, commonly reported by participants as occurring due to the pandemic, were associated with higher depressive symptoms. These work-related major life events increased in prevalence relative to the four-year review. However, the greatest risk for reporting either EPDS 10+or 13+was in those mothers with previous mental health difficulties, echoing other reports of vulnerability in this group during times of stress (Milgrom et al., Citation2008). This study did not include questions regarding domestic violence, which has since emerged as highly relevant to mental health and wellbeing during COVID-19 lockdown restrictions (Neil, Citation2020).

Emerging reports of psychological symptoms in adults from the general population completing online surveys from Australia, the UK and China suggest elevated symptoms relative to population norms during COVID-19 lockdowns (Newby, Citation2020; Shevlin et al., Citation2020; Wang et al., Citation2020). A meta-analysis of eight studies of pregnancy or postpartum women from different countries during the pandemic showed strong evidence for increased anxiety symptoms, and weaker evidence for increased depressive symptoms (Hessami et al., Citation2020). None of the above studies were in representatively sampled or pre-existing cohorts, leaving open the possibility of selection bias. Selection bias into the initial cohort or early responders in the current wave have been investigated using inverse probability weighting and do not appear to be substantial. However, the absence of the counterfactual (i.e., those not exposed to lockdown) precludes causal inference about the effects of lockdown. It is also unclear whether the prevalence of pre-clinical depressive symptoms (EPDS 10+) requires intervention or reflects understandable adjustment difficulties in the context of social adversity, which are likely to be transient and self-limiting. Ongoing research regarding the mental health of men as well as women who are not mothers, and across other age groups and geography during the COVID-19 pandemic will be required to generalise and extend upon these findings.

The Australian government has attempted to protect household incomes through the JobKeeper program. Even in this context, the impact of short-term work-related events on mental health appears substantial and these findings need to be taken into account for future policy decisions as the COVID-19 pandemic continues. Our findings also indicate the need to make mental health services accessible to those with a mental health history. In countries that have experienced different COVID-19 infection rates, stricter lockdowns and different policy responses, the effects on mental health may be greater than those reported here. Further, the mental health burden is likely to have increased in the context of the second wave and stricter lockdown in Victoria from July to October 2020.

Here we show the first data from a representative sample of Australian mothers, revealing a strong pattern of increasing depressive symptoms as their children age from birth to seven/eight years of age, the latter being coincident with the first COVID-19 lockdown. We show that mothers most in need of support at child age seven/eight are those with prior depression. Whilst causality cannot be inferred, findings coincide with the first lockdown due to COVID-19, and may reflect the impact of physical distancing, and other measures, to control the spread of disease. Our findings echo established calls for increased mental health support for women across the early childhood period, and highlight the importance of supporting parents of school age children. We further suggest that measures taken to deal with the COVID-19 pandemic may intensify risk in this group and require additional support, including targeted programs for those at increased risk (Galea et al., Citation2020). Increasing the availability of community supports more broadly, such as social support community groups, telephone counselling services and other neighbourhood initiatives may also be relevant preventative action for mental health during the pandemic.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aida, J., Kawachi, I., Subramanian, S., & Kondo, K. (2013). Disaster, social capital, and health. In I. Kawachi, S. Takao, & S. V. Subramanian (Eds.), Global perspectives on social capital and health (pp. 167–187). Springer.

- Allen, K. J., Koplin, J. J., Ponsonby, A.-L., Gurrin, L. C., Wake, M., Vuillermin, P., Martin, P., Matheson, M., Lowe, A., Robinson, M., Tey, D., Osborne, N. J., Dang, T., Tan, H.-T. T., Thiele, L., Anderson, D., Czech, H., Sanjeevan, J., Zurzolo, G., … Dharmage, S. C. (2013). Vitamin D insufficiency is associated with challenge-proven food allergy in infants. Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, 131(4), 1109–1116.e1106. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2013.01.017

- Brown, S. J., Mensah, F., Giallo, R., Woolhouse, H., Hegarty, K., Nicholson, J. M., & Gartland, D. (2020). Intimate partner violence and maternal mental health ten years after a first birth: An Australian prospective cohort study of first-time mothers. Journal of Affective Disorder, 262, 247–257. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.015

- Buist, A. E., Milgrom, J., Barnett, B. E. W., Pope, S., Condon, J. T., Ellwood, D. A., Boyce, P. M., Austin, M.-P. V., & Hayes, B. A. (2002). To screen or not to screen — That is the question in perinatal depression. Medical Journal of Australia, 177(S7), S101–S105. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2002.tb04866.x

- Cox, J. L., Chapman, G., Murray, D., & Jones, P. (1996). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 39(3), 185–189. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782–786. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

- Eastwood, J. G., Phung, H., & Barnett, B. (2011). Postnatal depression and socio-demographic risk: Factors associated with Edinburgh Depression Scale scores in a metropolitan area of New South Wales, Australia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(12), 1040–1046. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2011.619160

- Edmondson, O. J., Psychogiou, L., Vlachos, H., Netsi, E., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2010). Depression in fathers in the postnatal period: Assessment of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale as a screening measure. Journal of Affective Disorder, 125(1–3), 365–368. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2010.01.069

- Galea, S., Merchant, R. M., & Lurie, N. (2020). The mental health consequences of COVID-19 and physical distancing: The need for prevention and early intervention. JAMA Internal Medicine, 180(6), 817–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2020.1562

- Greenland, S., & Drescher, K. (1993). Maximum likelihood estimation of the attributable fraction from logistic models. Biometrics, 49(3), 865–872.

- Hessami, K., Romanelli, C., Chiurazzi, M., & Cozzolino, M. (2020). COVID-19 pandemic and maternal mental health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Maternal Fetal and Neonatal Medicine, 1–8. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14767058.2020.1843155

- Holmes, T. H., & Rahe, R. H. (1967). The social readjustment rating scale. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 11(2), 213–218. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0022-3999(67)90010-4

- Institute, B. D. (2020). Mental health ramifications of COVID-10: The Australian context. Report.

- Little, R. J., & Rubin, D. B. (2019). Statistical analysis with missing data (Vol. 793). John Wiley & Sons.

- Matthey, S., Henshaw, C., Elliott, S., & Barnett, B. (2006). Variability in use of cut-off scores and formats on the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale: Implications for clinical and research practice. Archives of Womens Mental Health, 9(6), 309–315. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-006-0152-x

- Milgrom, J., Gemmill, A. W., Bilszta, J. L., Hayes, B., Barnett, B., Brooks, J., Ericksen, D., & Buist, A. (2008). Antenatal risk factors for postnatal depression: A large prospective study. Journal of Affective Disorders, 108(1–2), 147–157. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2007.10.014

- Neil, J. (2020). Domestic violence and COVID 19. Australian Journal for General Practitioners. https://www1.racgp.org.au/ajgp/coronavirus/domestic-violence-and-covid-19

- Newby, J. M. (2020). Acute mental health responses during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia. medRxiv (Preprint). medRxiv. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.05.03.20089961

- Ribeiro, W. S., Bauer, A., Andrade, M. C. R., York-Smith, M., Pan, P. M., Pingani, L., … Evans-Lacko, S. (2017). Income inequality and mental illness-related morbidity and resilience: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 4(7), 554–562. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30159-1

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (2020). Psychiatrists see alarming rise in patients needing urgent and emergency care and forecast a ‘tsunami’ of mental illness [Press release]. https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/news-and-features/latest-news/detail/2020/05/15/psychiatrists-see-alarming-rise-in-patients-needing-urgent-and-emergency-care?searchTerms=tsunami

- Shevlin, M., McBride, O., Murphy, J. (2020). Anxiety, depression, traumatic stress, and COVID-19 related anxiety in the UK general population during the COVID-19 pandemic. BJPsych Open, 6(6), e125–e.

- Stay at Home Directions (No 6), Section 200 C.F.R. (2020).

- Sutton, B. (2020). Directions issued by Victoria’s Chief Health Officer. Victorian State Government. https://www.dhhs.vic.gov.au/victorias-restriction-levels-covid-19

- Tsirtsakis, A. (2020). Fears of post-pandemic ‘tsunami of health problems’. RACGP. https://www1.racgp.org.au/newsgp/clinical/gps-fear-post-pandemic-tsunami-of-health-problems

- Vuillermin, P., Saffery, R., Allen, K. J., Carlin, J. B., Tang, M. L., Ranganathan, S., Burgner, D., Dwyer, T., Collier, F., Jachno, K., Sly, P., Symeonides, C., McCloskey, K., Molloy, J., Forrester, M., & Ponsonby, A.-L. (2015). Cohort profile: The Barwon infant study. International Journal of Epidemiology, 44(4), 1148–1160. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyv026

- Wacholder, S. (1986). Binomial regression in GLIM: Estimating risk ratios and risk differences. American Journal of Epidemiology, 123(1), 174–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a114212

- Wang, C., Pan, R., Wan, X., Tan, Y., Xu, L., Ho, C. S., & Ho, R. C. (2020). Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(5), 1729. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17051729

- Wenham, C., Smith, J., & Morgan, R. (2020). COVID-19: The gendered impacts of the outbreak. The Lancet, 395(10227), 846–848. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)30526-2

- Woolhouse, H., Gartland, D., Mensah, F., & Brown, S. J. (2015). Maternal depression from early pregnancy to 4 years postpartum in a prospective pregnancy cohort study: Implications for primary health care. BJOG, 122(3), 312–321. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/1471-0528.12837