ABSTRACT

Objective: Two common mood induction procedures (MIPs) use autobiographical recall (AR) or video clips. The first relies upon internal generation of mood states whereas the second presents external information to elicit emotion. Often new video clips are created for each experiment. However, no study has examined the efficacy and specificity of a freely available video clip compared to AR for use in other studies.

Method: In the present experiment, participants watched either video clips or engaged in autobiographical recall to induce an emotional state. Participants were 53 University first year psychology students who took part for course credit.

Results: The anger video clip was more effective compared to AR at increasing the target emotion (anger) and decreasing the non-target emotions - happiness and serenity. Compared to baseline both the video and AR anger scores were higher than sadness scores.

Conclusion: The response to recalling personal events is more influenced by personality characteristics such as trait anger and neuroticism compared to the response to the video stimulus, which proved a cleaner stimulus. Implications for future research in both mood induction and media are discussed.

Key points

What is already known about this topic:

Mood affects cognitive prowess and memory recall.

Emotional reactions are usually created by autobiographical recall, such that the person creates their own mood state by remembering an emotionally congruent scenario from their past.

Autobiographical recall is an internal experience and leaves the experimenter with little chance of standardising or manipulating the stimulus, unlike with the use of video inductions.

What this topic adds:

Personality predicts anger when under the autobiographical recall method of mood generation, but not with a video clip induction (of animal cruelty).

The video clip was more effective compared to autobiographical recall at increasing the target emotion (anger).

The video induction relies less upon participant characteristics (e.g., imagination ability and personality), is cheap to administer, has now been standardised, and the content is in the public domain.

Mood can influence an individual’s response to media, as well as performance on cognitive tasks and memory (Unsworth et al., Citation2007; Van Damme, Citation2012). In order to examine these effects researchers have developed various techniques to induce mood states. Until now there has been no study which has used freely available resources to develop a brief and effective mood induction procedure (MIP). We aim here to address this shortfall.

The ability to effectively induce mood in a controlled manner has aided the process in dis-entangling the complexities of emotional states such as depression and anxiety (e.g., Brewer et al., Citation1980) and the nature of memory (e.g., Teasdale & Taylor, Citation1981). These mood induction procedures allow researchers to create analogies to real emotions with the aim of establishing ecological validity in the testing of psychological mechanisms. These MIPs attempt to create a controlled transient change in a participant’s state mood. The ability to induce a mood has varied applications in psychological experimentation. In order to see the effects of a specific stimuli on a specific mood, researchers commonly need to induce the mood first. For example, we may wish to induce a specific mood to understand the effects of sales advertising after exposure to stimuli which creates that mood. An obvious example of this would be understanding the type of advertising which works best (i.e., sells more) during or after a horror film or a romantic comedy. It may even be that we wish to study the effects of mood on compliance or perhaps on the effects of alcohol on mood states. In our own research (Devilly et al., Citationin press) we have needed to induce mood states to test the effects of violent videogames on anger and aggression. In a previous study (Unsworth et al., Citation2007) we found differential responses depending upon personal traits and current state. For example, playing violent videogames when in an angry state led labile adolescents (i.e., 11 to 17 years old, high in neuroticism, trait anger and psychoticism) to reduce their state anger. In order to test this effect in a University population we had the problem of a floor effect in state anger ratings and needed to induce an angrier state before experimentation. Media classification systems are constantly under revision and there is a big push in the USA by some academics to have violent gaming banned due to the perceived harm of gaming. Under such circumstances, we argue that the imposition of an induced, short-term, negative mood state in participants is outweighed by the common good that comes from pertinent research which informs policy. We also argue that the use of a relaxing activity at the end of the research study ensures that induced negative mood states remain within the experimental paradigm.

There are a variety of MIPs with differing levels of efficacy, each of which have their own strengths and weaknesses (see Gerrards-Hesse et al., Citation1994; Martin, Citation1990; Rottenberg et al., Citation2007; Westermann et al., Citation1996). One of the most commonly used MIPs is autobiographical recall (AR), which involves imagining a situation from one’s life that evokes the experimentally desired mood (Brewer et al., Citation1980). This technique can also involve writing down the event to intensify the experienced emotion (Westermann et al., Citation1996). We would argue that due to each participant imagining a personal event, the experimenter has little control over the stimulus. Furthermore, although participants are generally instructed to imagine the event as vividly as possible, there is large variability in an individual’s willingness/ability to do so. For example, Cui et al. (Citation2007) found they could objectively quantify individual differences in mental imagery ability via examination of brain activity using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). In effect, we have different abilities when it comes to imaginal vividness and, with vividness of memory being associated with changes in induced mood (Richardson & Taylor, Citation1982), a weakness of AR is this interpersonal variation. Despite these limitations, AR is one of the most effective MIPs we have and can be used to induce both positive and negative moods (Baker & Guttfreund, Citation1993).

Another often implemented MIP is the use of video. Westermann et al. (Citation1996) suggests that this, in combination with explicit instructions provided to the participants to enter a mood state, is the most effective MIP. It has been used by many researchers with various stimuli. For example, Marston et al. (Citation1984) adapted a video called “The Champ” which lasted for 55 minutes to induce sadness, whereas Papousek et al. (Citation2009) used brief (1 minute, 20 second) clips of an actress depicting various moods (sadness, anxiety, anger, cheerfulness, and neutral). These two studies highlight the stimulus variability used across mood induction studies (cf. Martin, Citation1990). It appears that many studies “re-invent the wheel” and develop a new video MIP for each study. This inconsistency in methodology across research reduces the ability to compare results and confidently establish mechanisms. Moreover, it appears there has never been a study which standardizes a brief video MIP that can be made freely available for general use.

A seminal study by Salas et al. (Citation2012) examined the effectiveness and selectivity of four video clips and matching Affective Story Recall (ASR) tasks designed to elicit fear, anger, joy and sadness. This study utilised a smaller duration of recall time with the range across ASR mood groups being 40 to 236 seconds and the duration range for video clips being similar (122–246 seconds). They found that both the internal and external MIPs induced the target mood more so than the non-target moods. With the exception of the mood “joy”, the video clips and ASR were equally effective at inducing the target mood. However, the internal MIP appeared to increase non-target emotions more so than the video clips partly due to an overall higher level of intensity. Salas et al. (Citation2012) suggest this increased blend of emotions may be due to the ASR being more dynamic and complex compared to observing a video clip. More specifically, they found in, a qualitative analysis, that the written recording of participants’ events often included mention of multiple emotions.

The proposed benefit of using a video MIP compared to AR is standardisation of the stimulus and the engaging nature of this media, in that it actively provides information for the visual and auditory senses. This suggests that it relies less upon participant motivation and imagination ability. The more the MIP relies upon self-generation the more susceptible it will become to the influence of individual differences. For example, Larsen and Ketelaar (Citation1989) found that introverts (in comparison to extraverts) displayed greater emotional reaction to positive MIPs, and individuals high in neuroticism (compared to stable participants) demonstrated more emotional reactivity to negative MIPs. Trait anger also influences individuals’ response to stimuli. Honk et al. (Citation2001) suggest people high on trait anger have increased selective attention for angry stimuli. Moreover, individuals high on trait anger will more readily process semantic anger related stimuli (Parrott et al., Citation2005). More generally high trait anger is associated with greater anger in many different provocations (Deffenbacher et al., Citation1996). Although video MIPs present a standardised stimulus, they are still subject to interpretation by the individual.

It is impossible to control the reactions of participants as they draw upon previous experiences and memories when interacting with the world. This is likely partly why MIPs at times induce moods that were unintended. For example, Salas et al. (Citation2012) found that although the affective recall task increased the target mood significantly more than non-target emotions, participants in this condition displayed more negative and mixed blends of emotions compared to the video MIP. This non-target emotion increase is difficult to avoid, yet it can be explored by the use of self-report mood questionnaires which include a range of mood groups. A major criticism of mood induction studies is that they often provide manipulation check measures which are self-confirming (Martin, Citation1990). Papousek et al. (Citation2009) in their examination of the influence of mood on cognitive performance completed a manipulation check by asking “how sad did this video make you?” This forced-choice format may create artificial change as the participant is able to “guess” the desired response and thus their response reflects demand effects rather than mood change (Westermann et al., Citation1996). This forced choice, demand effect fuels the argument that MIPs do not create real emotions. Larsen and Sinnett (Citation1991) found in their meta-analysis that when participants are explicitly told the purpose of the mood induction procedure the mean ratings of the mood are higher. Whether this is an example of demand effects or a useful way of increasing the effectiveness of a MIP is questionable. Demand characteristics are an experimental artefact where it is difficult to discern whether a participant’s response is due to the stimuli or social desirability. For example, if told to “imagine and write down an event which made you angry” the participants’ affect rating could reflect both the effect of the autobiographical recall and the unconscious drive to please the experimenter by responding according to the experimental “hypothesis” (Marlow & Crowne, Citation1961).

Westermann et al. (Citation1996) found that the majority of MIPs were more effective at inducing negative moods. This is likely due to the more general positive mood participants are at baseline before engaging in experiments. It is much more difficult to enhance an already pleasurable mood than to depress it. This concept also applies to the induction of anger. This is a significant issue when considering the breadth of research investigating the effect of media such as visual media and video games on anger. In laboratory studies examining media exposure research typically focusses on the difference in self-reported anger from a neutral baseline. However, what we call neutral maybe more in line with pleasurable. For example, Devilly et al. (Citation2012) found at intake that participants’ state anger was on average 11 – just one point above the minimum score. Thus, individuals are typically not experiencing anger at baseline, so when attempting to induce anger either via media or a MIP we are changing a whole emotional state from comfortable to angry. These scores are much larger than when attempting to enhance an already existing emotional state. It is important to note that individuals view and engage in media when experiencing various moods and this in turn has varying effects on their affect. For example, Posse et al. (Citation2003) found participants’ anger ratings both increased and decreased following exposure to a violent video game (Quake III) – a result also found in Unsworth et al. (Citation2007). The ability to artificially manipulate participants’ anger effectively in a laboratory setting will further the ability to investigate the interaction between affect and media.

When considering the usefulness of MIPs it is necessary to consider both their effectiveness and specificity. Techniques focussed on inducing sadness often influence non-targeted moods such as anger (Polivy, Citation1981). However, Mayer et al. (Citation1995) argued that MIPs are still useful despite the modest influence on alternative moods. Mood is a complicated phenomenon and many attempts have been made to conceptualise its mechanisms. Research suggests valence and arousal are two independent dimensions of affect (Russell & Barrett, Citation1999). Valence is the subjective experience of pleasure and is typically defined as the pleasant/unpleasant aspect of mood, whereas arousal is the sense of activity or energy associated with affect. For example, Russell and Barrett (Citation1999) suggest an affect both high on valence (pleasure) and arousal (stimulated) would be excitement. Jallais and Gilet (Citation2010) suggest that the level of arousal can distinguish emotions similarly rated on the valence dimension. Thus, exploring the effect of MIPs on both of these dimensions allows a better understanding of the mechanism of these techniques.

The purpose of the following study was to investigate the effectiveness and specificity of a video MIP (V) procedure designed to elicit anger. The change in mood following this stimulus was compared against the commonly used autobiographical recall (AR) task. Further, this study explored the effect of personality on an individual’s response to MIPs. This current study expands upon Salas et al. (Citation2012) through the examination of trait variables, arousal, and use of freely available MIP stimuli.

The first prediction was that, overall, the anger conditions (both V and AR) would significantly increase self-report ratings of anger compared to neutral versions of the stimuli. Secondly, based upon Westermann et al. (Citation1996), it was predicted that the video condition would lead to significantly more anger compared to AR. Thirdly, it was predicted that higher ratings on trait aggression and neuroticism would be associated with greater emotional reactivity to the anger conditions. Furthermore, in an attempt to explore the concept of demand effects, this study provided no instructions for the video condition other than to watch it, whereas the AR condition explicitly requested the participants to enter a desired mood. It was hypothesised that, despite not requesting the participants to become angry, the video condition will specifically increase anger ratings with less increase in non-target emotions compared to the AR condition.

Method

Design

This study used a between and within subjects mixed design, utilising a convenience sample of students. The between subjects variable related to MIP type (AR vs V) and the within subjects compared across the neutral and anger versions of each MIP type. Materials and data are available at the Open Science Foundation project page: https://osf.io/6qyn4/

Participants

Participants were 53 University first year psychology students who took part for course credit, of whom 24.5% (n = 13) were males and 75.5% (n = 40) were females, all with a mean age of 21 years (SD 6.59). provides data concerning the marital status, ethnic origin, highest level of education, and annual family income of the complete sample. As is evident in , the majority of participants were not in a relationship (83%, n = 44), identified themselves as Australian/Northern European ethnic origin (64.1%, n = 34), were part way through tertiary education (96.2%, n = 51), and predominantly had an annual household income of less than $25,999 (54.7%, n = 29). These ratios are consistent with our psychology course make-up and suggests that there were no obvious self-selection biases into a study that was advertised as “Mood and Media: The effects of different media on psychological factors” and which stated that they would be required to: “Watch a small youtube clip (<2 minutes) where you may see a video published by the RSPCA about animal cruelty (containing some distressing scenes) or one published by the BBC introducing a documentary on dogs; or complete a 10 minute task where you will recall and write about a recent event in your life which either made you angry or serene”.

Table 1. Socio-demographic information

Measures

Personality

Two questionnaires were included to measure personality traits, specifically the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire Revised Edition (EPQ-RSS; Eysenck & Eysenck, Citation1975; Eysenck et al., Citation1985) and the State Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI; Spielberger, Citation1991). The EPQ-RSS is a 48-item version of the original 100 item measure (correlations of r = .87 or above on dimensions). The neuroticism dimension is conceptualised as emotional instability and reactiveness. High scores on this scale indicate a tendency to be anxious, depressed, emotional, shy and have low self-esteem. A neurotic individual is suggested to have a lower activation point for their autonomic nervous system (Eysenck et al, Citation1985). Both neuroticism and psychoticism have been linked to increased likelihood of adverse effects following exposure to activities such as violent video games (e.g., Markey & Markey, Citation2010; Unsworth et al., Citation2007). The STAXI measures both state (see below) and trait anger. The measure has good divergent and convergent validity and strong concurrent validity for trait anger (Spielberger, Citation1991). A two-week test-retest study yielded reliability coefficients of .74 and .88 for trait anger and anger expression, respectively.

Valence and arousal

Before and after each MIP participants were asked to complete questionnaires in order to assess their mood on both the valence and arousal dimensions:

Brief mood introspection scale

To assess the specificity of a valence change in response to MIPs, participants completed a modified version of the Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS; Mayer & Gaschke, Citation1988). This modification had been made by Corson (Citation2006) and Corson and Verrier (Citation2007), increasing a 4-point Likert Scale to a 7-Point Likert Scale. The scale has four mood state measures: Pleasant to Unpleasant and Arousal to Calm scales. Recent research (Cavallaro et al., Citationin preparation) has shown the 7-point scale to be at least as reliable as the 4-point scale (Pleasant-Unpleasant α = .83; Calm-Arousal = .58). This measure has shown to be sensitive to changes in mood following induction (Cavallaro et al., Citationin preparation) and to converge with measures one would expect to covary with positive mood, such as flourishing (r = .26), self-liking (r = .46; Totan, Citation2014) and self-esteem and sense of personal coherence (r = .43 and .51, respectively; Greitemeyer et al., Citation2014) and diverge from loneliness (r = −.32). Mean scores were obtained for each group of adjectives.

Affect grid

Following the BMIS participants completed a modified version of the affect grid designed by Russell et al. (Citation1989). The first question regarding valence asked participants using the aid of a visual anagram to rate on a 9-point scale how “happy” they felt. The second question queried how aroused they were, also on a 9-point scale. The scale has demonstrated to be reliable between groups (r = .98), convergent with similar measures (r = .89 to .95) and discriminates between the two affects (r = .01 to .17; Russell et al., Citation1989).

State anger – STAXI

The STAXI was also utilised to provide a pre-post measure of participants’ state anger following the MIPs. State anger has a very low two-week test-retest reliability, as one would expect (r = .01; Bishop & Quah, Citation1998). Test-retest for state anger is .77 after 20 minutes (Cahill, personal communication 11 February 2003).

Stimulus

Videos

Two open-sourced videos were obtained from YouTube to induce either “anger” or “serenity”. The anger video is a 1 minute 47 second clip created by the RSPCA (https://youtu.be/twrFHemSgrw) that depicts various images of both cats and dogs being maltreated including the final segment showing a male repeatedly kicking his dog. The serene video was shortened to match the length of the anger video and was from the BBC documentary “secret life of dogs” (https://youtu.be/0U41yzF-JGk). It depicts images of dogs in various natural states while a voice over describes the abilities of these animals.

Autobiographical recall

Originally described by Mosak and Dreikurs (Citation1973) AR was modified by Krauth-Gruber and Ric (Citation2000). According to this version, participants are asked to recall and write down a situation in which they had experienced serenity or anger. The participants were encouraged to provide as many details as they could and to report events as vividly as possible. The participants were given 10 minutes to perform this task.

Induction of serenity was used as the comparative neutral condition due to the possibility that requesting participants to recall a more mundane task (e.g., going shopping) could induce an undesired negative mood such as boredom and frustration.

Procedure

Prior to commencement of data collection, ethics permission was granted by the University Human Research Ethics Committee. Participants completed the study which ran for approximately 45 minutes in computer labs with 10 participants being the maximum per group.

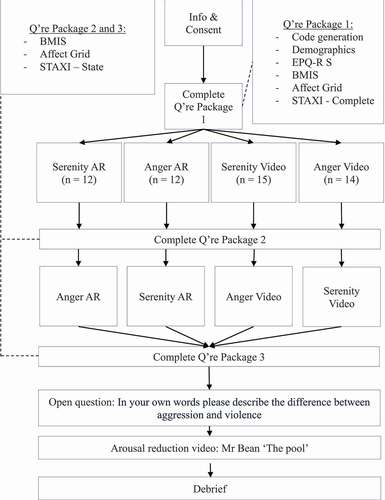

demonstrates the order of the study and sample size per condition. There were four conditions in this study based upon a 2 × 2 design (MIP video vs. autobiographical recall) × Order (Serenity/Neutral or Anger condition first). Participants were randomly assigned (utilising a seeded random number generator) into MIP type then order. Participants then watched a 10 minute 46 second open-source video from YouTube which was segment of a Mr Bean episode called “The swimming pool”. This was done to improve the mood of our participants following the experiment.

Figure 1. Flow diagram of study procedure. AR = Autobiographical Recall; Q’re = Questionnaire; The Eysenck Personality Questionnaire-Revised Short Scale (EQR-R S) is from Eysenck et al. (Citation1985); The Brief Mood Introspection Scale (BMIS) is from Mayer and Gaschke (Citation1988) modified by (Corson, Citation2006; Corson & Verrier, Citation2007); The State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory (STAXI) is from Spielberger (Citation1991); and the affect grid is from Russell et al. (Citation1989). There were no drop-outs from conditions

Results

Approach to analysis

The sample was drawn from a student population and, measuring state lability, we expected a non-normal distribution. The results are arranged into four sections: data screening; Valence and arousal from MIPS; effectiveness and specificity of MIPS; and Personality variables and MIPS. Analyses were performed using ClinTools 4.1 (Devilly, Citation2007), SPSS 22.0 (IBM Corp Inc., Citation2013) and Statistica 9 (Statsoft Inc., Citation2010)

Data screening and order effects

As outlined in there were four conditions in this study. To increase the sample size for analysis and, therefore, improve the robustness of results it was our intention to combine data for conditions 1 and 2, and conditions 3 and 4, if there were no ordering effects. No outliers based upon the criteria of 3.29 standard deviations above the mean were found for the mood measures. Data was also screened for violations of normality, variables which had either skewness or kurtosis statistics which were greater than twice the standard error were noted. The difference between baseline and neutral, and baseline and anger scores were created for the state anger (STAXI) and each mood group of the BMIS and Affect Grid. Analysis (either paired-samples t-test or Wilcoxon Signed-ranks test where data was non-normal) were completed for all of these change scores and there was no significant difference in mood change due to order of presentation. From this point onwards conditions will be referred to by stimulus Video (N = 29) and AR (N = 24).

In the combined data, and across all variables, ten data points were above the 3.29 sd cut-off. However, these were also in variables that violated assumptions of normality beyond the influence of these outliers. Although relatively robust to violations of normality, t-tests and ANOVA are more susceptible to the influence of outliers (Schmider et al., Citation2010). Therefore, non-parametric analyses (Wilcoxon Rank-sum tests and Wilcoxon Signed-ranks tests) were used when the variable violated assumptions of normality and contained outliers.

Examining specificity of mood was achieved by computing mean scores for each of the four subscales of the BMIS (Happiness: lively, happy, cheerful, peppy; Sadness: sad, gloomy, unhappy, depressed; Anger: furious, hostile, mad, angry; Serenity: peaceful, serene, calm, relaxed). These subscales were then used to examine changes in moods other than the target mood anger.

Within stimulus condition results

depicts the means and standard deviations for baseline, post-neutral and post-anger scores for both the Video and AR stimulus. Related-samples Wilcoxon Signed-ranks tests and paired samples t-tests were used to examine the repeated measure differences.

Table 2. Means and standard deviations for baseline, neutral stimuli and anger stimuli

Video

Analysis indicates that compared to baseline the Anger video significantly increased Anger as measured by both the STAXI and BMIS. It also significantly increased sadness ratings and arousal. Furthermore, it significantly decreased ratings of happiness, serenity and pleasurable valence. These were all at the p < .001 significance level. The neutral video appeared to increase happiness, arousal and pleasurable valence and decreased sadness compared to baseline, but all at a p < .05 level. With 14 analyses within each MIP, and accounting for familywise error, one would normally only have faith in probability levels of greater than .004 (overall) or .007 within each mood induction.

Autobiographical recall

Related-samples Wilcoxon Signed-ranks tests and paired samples t-tests indicate that compared to baseline the anger AR significantly increased Anger as measured by both the STAXI and BMIS. Furthermore, it significantly decreased ratings of happiness, serenity and pleasurable valence. The neutral AR appeared to decrease anger and sadness compared to baseline but, similarly to the video, these changes to neutral are not reliable when the number of analyses is taken into account.

Difference to baseline within stimulus

In order to compare the effect of the neutral stimulus versus the anger stimulus for both video and autobiographical recall difference scores to baseline were computed for each measure. As such the greater the negative score the more change (positive increase) from baseline is a score. These within condition scores and effects sizes for the analyses are depicted in .

Table 3. Comparing difference to baseline scores within stimulus condition

Video

In comparison to the neutral video, the anger video significantly increased Anger and Sadness ratings. Furthermore, it decreased Happiness and Serenity more than the neutral video increased these. Moreover, the anger video decreased pleasurable valence more effectively than the neutral video increased it. These results suggest the Anger video was more effective at increasing negative affect compared to the Neutral video’s ability to increase positive affect.

Autobiographical recall

In comparison to the neutral AR, the anger AR significantly increased Anger and Sadness ratings compared to baseline. Also, it decreased Happiness and Serenity more than the neutral video increased these. These results suggest the Anger AR was more effective at increasing negative affect compared to the Neutral AR’s ability to increase positive affect. With 14 analyses, the mean difference between the neutral AR and angry AR conditions on sadness should be treated as unproven. All other significant distinctions reach a level of p < .001.

Comparing video to autobiographical recall

State anger (STAXI)

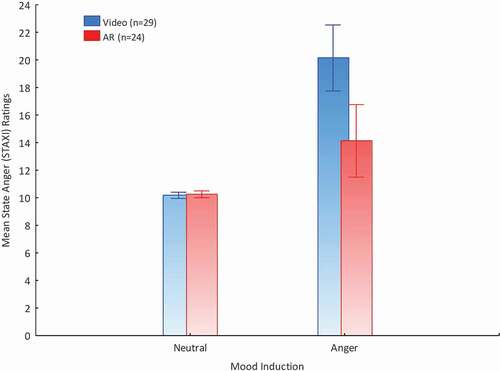

In order to examine the different MIPs’ effectiveness in changing state anger (STAXI) a 2 × 2 (Mood Group [neutral, anger] × Stimulus Type [Video, AR]) repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. Both the mood group F(1, 51) = 61.22, p < .001, ηp2 = 0.55 and stimulus type F(1, 51) = 11.00, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.18 main effects were significant, as well as the Mood Group × Stimulus Type interaction, F(1, 51) = 11.86, p = .001, ηp2 = 0.19. visually depicts this interaction, displaying that on the STAXI measure of anger the response to the neutral video and neutral AR were similar, whereas state anger scores following the anger video were higher than the anger AR task. This difference between conditions will be further examined utilising both baseline post MIP difference (BD) scores and difference of difference scores (DD). DD scores are created by subtracting baseline to anger difference scores away from baseline to neutral difference scores for each stimulus. The larger the negative DD scores the more effective the neutral stimulus was at increasing this measure and the better the anger stimulus was at decreasing it. The larger the positive DD score the more effective the neutral stimulus was at decreasing this affect and the better the anger stimulus was at increasing it. presents the comparison effect sizes within mood group (baseline to stimulus difference score) between stimulus type (AR versus video). It also presents the means and standard deviations of stimulus difference scores (AR and Video) and effect sizes for the interaction between these difference scores.

Table 4. Comparing difference to baseline scores and difference of difference scores between stimuli

Figure 2. Mean state anger score (STAXI; Spielberger, Citation1991) for each mood group and stimulus type

Neutral stimuli

As can be seen in with respect to difference to baseline scores there are no significant differences between the neutral video and neutral AR, suggesting similar effects across mood groups between these stimuli.

Anger stimuli

also shows that the Anger Video difference scores from baseline were significantly higher for Sadness and Anger (as measured by both the BMIS and STAXI) compared to the anger AR task. Furthermore, the Anger Video significantly decreased Happiness, Serenity and Pleasurable valence compared to the Anger AR, but only at p < .05 significance level. With 7 analyses within each comparison column we do not have confidence in this difference. The same trend was found for the difference of difference scores. This suggests that, in combination, the neutral video and anger video were better at increasing or decreasing moods in the expected direction compared to the AR task. Thus, as one would want with a mood induction procedure, overall difference to baseline, and difference of difference scores, suggest that the anger video was more effective in both increasing low pleasure affects (sadness and anger) compared to the Anger AR task.

Specificity analysis

In order to establish whether there was a difference in the Anger Video and Anger AR effect on sadness and anger, a specificity analysis was conducted.

Video

A Wilcoxon Signed-ranks test (n = 29) indicated that anger ratings (Mdn = 5.00) and sadness ratings (Mdn = 5.00) were not significantly different post the anger video, Z = −.47, p = .64, g = −0.13, 95% CI [−0.65, 0.38]. However, the video appears to be better at increasing anger than increasing sadness: a paired-samples t-test (n = 29) indicated that, for the Anger Video participants, difference scores from baseline to anger were significantly larger (M = −3.36, SD = 1.77) compared to baseline to sadness scores (M = −2.45, SD = 1.83) t(28) = −2.58, p = .015, g = −0.50, 95% CI [−1.07, 0.08]. While the 95% confidence interval effect size statistics seem to pass through zero it should be noted this is a between samples effect size for a within samples t-statistic (which intrinsically has less error).

Autobiographical recall

A paired-samples t-test (n = 24) indicated that participants’ anger ratings (M = 3.10, SD = 1.39) and sadness ratings (M = 2.96, SD = 1.39) were not significantly different after the anger AR, t(23) = −0.76, p = .46, g = −0.10, 95% CI [−.67, 0.46]. However, and similarly to the video stimulus, a paired-samples t-test (n = 24) indicated that, for the Anger AR participants, difference scores from baseline to anger were significantly larger (M = −1.41, SD = 1.52) compared to baseline to sadness scores (M = −0.37, SD = 1.20) t(23) = −4.23, p < .001, g = −0.75, 95% CI [−1.33, −0.16].

The previous analyses demonstrate that, without accounting for baseline variation, both the Anger Video and Anger AR have similar ratings for BMIS sadness and anger. With the use of difference scores, it appears both are more specifically increasing anger.

Personality correlations and response to MIPs

In order to better understand the difference between responses to the Anger Video and Anger AR, correlation matrices between mood variables and personality traits were constructed. is the correlational matrix for participants in the video and AR condition. Difference scores refer to the difference between baseline and anger video responses. As demonstrated in , only the correlation between Neuroticism and difference of difference (DD) arousal scores was significant. This positive correlation suggests the higher an individual rates on Neuroticism, the greater the disparity of responses to the anger video compared to the neutral video. While this is consistent with the emotional lability hypothesis, in that the participants are more reactive in the expected direction to both mood groups, replication is required.

Table 5. Correlation matrix for response to anger video or anger AR in relation to trait variables

Looking at participants in the AR condition, BD scores refer to the difference between baseline and anger AR responses. There is a significant negative correlation between Trait Anger, Trait Anger T, and anger difference scores rated by the BMIS and difference of difference scores calculated from the STAXI. This suggests that as Trait Anger increases anger responses to the anger AR condition do also. Further, for difference of difference scores obtained via the BMIS, both sadness and anger ratings were significantly correlated to both trait anger and neuroticism. Trait Anger T was also significantly related to STAXI difference scores. Overall responses to the Anger AR condition appear to be more influenced by personality variables compared to the anger video.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the effectiveness of a video mood induction procedure (MIP) and autobiographical recall MIP and compare their relative performance on changes in valence and arousal as measured by self-report. Overall, and as predicted, both the anger Video and anger AR significantly increased anger ratings as measured by both the STAXI and BMIS. Despite this similarity, there are multiple differences in the results between the two MIPs. Firstly, as predicted, the anger video was more effective in increasing anger ratings compared to the anger AR. This is despite the fact that the AR took longer in induction time and specifically requested participants to enter the desired mood state.

While the Video significantly increased arousal compared to baseline and the AR did not, between groups analysis did not reach significance. With regards to specificity, the anger video significantly reduced both serenity and happiness ratings to a lesser degree and increased sadness and anger ratings to a larger degree. Analysis suggests that the increase in anger was higher than sadness. The anger AR did not significantly increase sadness compared to baseline but did reduce happiness and serenity ratings.

Overall, the results suggest that the video condition was more effective in both increasing low pleasure affects (sadness and anger) and decreasing higher pleasure affects (happiness and serenity) compared to the AR condition. While the AR did increase anger it did not significantly increase sadness ratings compared to baseline. This may seem to demonstrate specificity, however, it may be more a function of differing intensity between stimulus types. In contrast to the results found by Salas et al. (Citation2012) the video in the current study displayed overall higher intensity compared to the AR. It is possible that if the AR task was as salient as the video it would have displayed similar effects on non-target emotions. Due to this lack of saliency the AR results were more susceptible to differences in baseline mood. There are two other valid reasons for the difference between stimuli in their induction of anger and sadness: firstly, demand effects, as discussed by Westermann et al. (Citation1996), may have led participants to respond more exclusively to the anger components of the BMIS following the AR; secondly, it might just be that the Video MIP simply induces both sadness and anger.

This study also examined the influence of personality characteristics in response to mood induction procedures. It was hypothesised that trait anger and neuroticism would be associated with increased response to the Anger MIPs (Deffenbacher et al., Citation1996; Larsen & Ketelaar, Citation1989). This hypothesis was supported only in part. It appears the response to the anger video stimulus is largely independent of trait variables with the possible exception of neuroticism. Conversely, increases in both sadness and anger ratings following the anger AR were significantly correlated with neuroticism and trait anger. Upon consideration this result appears consistent with the fundamental differences between the stimuli. The video condition relies less upon participant characteristics (e.g., imagination ability and personality) due to its external presentation of information, whereas the AR condition utilises individual, internally generated, personal stories to induce the mood. Arguably this highlights a relative strength of the anger video stimulus, in that it appears to more generally induce anger in all participants. The AR MIP appears more effective for those with predisposing personality variables. This is important when considering research investigating psychological, behavioural and neurological responses to mood. Utilising a MIP which is largely influenced by personality characteristics reduces the generalizability of results, as differences may be driven by trait variables rather than experimental variables.

Further, sometimes we would prefer not to alert the participant to the mood state we desire to induce for experimentation, and, in such cases, videos allow us to do this without specifically telling the participant to think of something which makes them angry. A good cover story (e.g., “we wish to also survey people’s opinions on the role of the RSPCA” or “we also wish to look at opinions on the legal consequences of animal cruelty”) allows us to obtain the desired mood state without disclosure of this goal but also without the use of procedural deception (as long as these “opinions” are also surveyed). Obviously, this is finely balanced issue, and one which needs to encompass disclosure that the participant will be viewing animal cruelty stimuli. This also raises the issue of self-selection into the study. In our study, the sample make-up was unremarkable to our usual samples of students and we also appeared not to have a sample with high psychoticism.

A limitation of this study, as with all convenience-based samples, is the difficulty of generalising the results to the population. The other side of this is that we were able to look at our sample to evaluate self-selection bias and, it is worth noting, that one might equally expect even larger differences in a less homogenous population, with the introduction of more variability in responses. Moreover, as we utilised psychology students, one might propose that the AR condition was more effective due to their more natural proclivity towards introspection. However, it may be less effective if compared to a different student sample, possibly one more focussed on practical study, such as engineering. Another limitation is that the two stimuli were not equal in length of time for administration, thus some results may be influenced by presentation length rather than content differences. Although this reduces the clarity of deductions it further supports the effectiveness of the video MIP. Despite being close to one 10th of the length of the AR condition, the video MIP significantly increased anger ratings from baseline more effectively.

This study examined short term changes in affect. However, it will be useful for future research to investigate the longevity of the mood change. Information regarding the stability of the induced mood change will allow researchers to decide which MIP is best for them considering their experimental length and procedure. Further, as a wide range of research relies upon the validity and reliability of pre-established MIPs, further research is needed in understanding the influence of individual characteristics such as imaginal ability, absorption, fantasy proneness and other personality factors. Thus, normative data should not only include specificity and effectiveness results but also correlations between trait variables. For the current results to be further validated and more reliable norms established, future research will need to examine the effect of the video on various representative samples. Importantly due to the task being computer based, easy to administer and brief, collecting data online is viable and further investigation of this video MIP is relatively easy.

Overall, this study demonstrates the relative complexity of an often-overlooked component of investigation of mood. The brevity utilised in describing MIPs in research (usually a brief description in the manipulation check section of a report) suggests they are simple and clear mechanisms. However, results from this study and Westermann et al. (Citation1996) suggest that there is large variability in the efficacy of MIPs and the degree to which they are influenced by personality variables. Theories of emotional change caused by various stimuli tend to see dispositional variables as incidental or not relevant to this emotional change (e.g., the General Aggression Model following violent video game play; Anderson & Bushman, Citation2002), while others see such variables as central to any change (e.g., Markey & Markey, Citation2010; Unsworth et al., Citation2007). The current research reiterates that emotional change passes through the lens of trait variables. AR as a stimulus to induce mood necessarily is an internal process and appears to be more affected by these variables.

The effect of, say, media on individuals’ mood and aggression has been a controversial topic since televised violence. An effective and easily administered MIP such as the anger video described in this study will hopefully assist in the experimental examination of the influence of various stimuli (e.g., media) on people by having more control of participants’ mood prior to that exposure.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27–51. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231

- Baker, R. C., & Guttfreund, D. O. (1993). The effects of written autobiographical recollection induction procedures on mood. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(4), 563–568. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(199307)49:4<563::aid-jclp2270490414>3.0.co;2-w

- Bishop, G. D., & Quah, S.-H. (1998). Reliability and validity of measures of anger/hostility in Singapore: Cook & Medley Ho Scale, STAXI and Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 24(6), 867–878. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(98)00024-5

- Brewer, D., Doughtie, E. B., & Lubin, B. (1980). Induction of mood and mood shift. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 36(1), 215–226. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-

- Cavallaro, R. M., Bryan, V., & Mayer, J. D. (in preparation). A review and evaluation of an open-source mood assessment, the brief mood introspection scale. Manuscript in Preparation.

- Corson, Y., & Verrier, N. (2007). Emotions and false memories: Valence or arousal? Psychological Science, 18(3), 208–211. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9280.2007.01874.x

- Corson, Y. (2006). Émotions et propagation de l’activation en mémoire sémantique [Emotions and propagation of activation in semantic memory]. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology/Revue Canadienne De Psychologie Expérimentale, 60(2), 127–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/cjep2006013

- Cui, X., Jeter, C. B., Yang, D., Montague, P. R., & Eagleman, D. M. (2007). Vividness of mental imagery: Individual variability can be measured objectively. Vision Research, 47(4), 474–478. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.visres.2006.11.013

- Deffenbacher, J. L., Oetting, E. R., Thwaites, G. A., Lynch, R. S., Baker, D. A., Stark, R. S., & Eiswerth-Cox, L. (1996). State-trait anger theory and the utility of the trait anger scale. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 43(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.43.2.131

- Devilly, G J, O'Donohue, R P, and Brown, K. (in press). Personality and frustration predict aggression and anger following violent media. Psychology, Crime & Law.

- Devilly, G. J. (2007). ClinTools (Version 4.1) [Computer software]. www.clintools.com

- Devilly, G. J., Callahan, P., & Armitage, G. (2012). The effect of violent videogame playtime on anger. Australian Psychologist, 47(2), 98–107. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00008.x

- Eysenck, H. J., & Eysenck, S. B. G. (1975). Manual of the Eysenck Personality Questionnaire (Junior and Adult). Hodder & Stoughton.

- Eysenck, S. B. G., Eysenck, H. J., & Barrett, P. (1985). A revised version of the psychoticism scale. Personality and Individual Differences, 6(1), 21–29. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(85)90026-1

- Gerrards-Hesse, A., Spies, K., & Hesse, F. W. (1994). Experimental inductions of emotional states and their effectiveness: A review. British Journal of Psychology, 85(1), 55–78. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8295.1994.tb02508.x

- Greitemeyer, T., Mügge, D. O., & Bollermann, I. (2014). Having responsive Facebook friends affects the satisfaction of psychological needs more than having many Facebook friends. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 36(3), 252–258. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2014.900619

- Honk, J. V., Tuiten, A., De Haan, E., Vann de Hout, M., & Stam, H. (2001). Attentional biases for angry faces: Relationships to trait anger and anxiety. Cognition and Emotion, 15(3), 279–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930126112

- IBM Corp. (2013). SPSS statistics for windows (Version 22.0) [Computer software].

- Jallais, C., & Gilet, A.-L. (2010). Inducing changes in arousal and valence: Comparison of two mood induction procedures. Behav Res Methods, 42(1), 318–325. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012815

- Krauth-Gruber, S., & Ric, F. (2000). Affect and stereotypic thinking: A test of the mood-and-general-knowledge model. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 26(12), 1587–1597. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672002612012

- Larsen, R. J., & Ketelaar, T. (1989). Extraversion, neuroticism and susceptibility to positive and negative mood induction procedures. Personality and Individual Differences, 10(12), 1221–1228. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0191-8869(89)90233-X

- Larsen, R. J., & Sinnett, L. M. (1991). Meta-analysis of experimental manipulations: Some factors affecting the Velten mood induction procedure. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(3), 323–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167291173013

- Markey, P. M., & Markey, C. N. (2010). Vulnerability to violent video games: A review and integration of personality research. Review of General Psychology, 14(2), 82–91. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019000

- Marlow, D., & Crowne, D. P. (1961). Social desirability and response to perceived situational demands. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 25(2), 109–115. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/h0041627

- Marston, A., Hart, J., Hileman, C., & Faunce, W. (1984). Toward the laboratory study of sadness and crying. The American Journal of Psychology, 97(1), 127–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/1422552

- Martin, M. (1990). On the induction of mood. Clinical Psychology Review, 10(6), 669–697. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/0272-7358(90)90075-L

- Mayer, J. D., Allen, J. P., & Beauregard, K. (1995). Mood inductions for four specific moods: A procedure employing guided imagery vignettes with music. Journal of Mental Imagery, 19(1–2), 151–159.

- Mayer, J. D., & Gaschke, Y. N. (1988). The experience and meta-experience of mood. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 55(1), 102–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.55.1.102

- Mosak, H. H., & Dreikurs, R. (1973). Adlerian psychotherapy. In R. Corsini (Ed.), Current psychotherapies (pp. 52–95). Peacock.

- Papousek, I., Schulter, G., & Lang, B. (2009). Effects of emotionally contagious films on changes in hemisphere-specific cognitive performance. Emotion, 9(4), 510–519. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016299

- Parrott, D. J., Zeichner, A., & Evces, M. (2005). Effect of trait anger on cognitive processing of emotional stimuli. The Journal of General Psychology, 132(1), 67–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3200/genp.132.1.67-80

- Polivy, J. (1981). On the induction of emotion in the laboratory: Discrete moods or multiple affect states? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 41(4), 803–817. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.41.4.803

- Posse, S., Fitzgerald, D., Gao, K., Habel, U., Rosenberg, D., Moore, G. J., & Schneider, F. (2003). Real-time fMRI of temporolimbic regions detects amygdala activation during single-trial self-induced sadness. NeuroImage, 18(3), 760–768. https://doi.org/http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00004-1

- Richardson, A., & Taylor, C. C. (1982). Vividness of memory imagery and self-induced mood change. The British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 21(Pt 2), 111–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1982.tb00539.x

- Rottenberg, J., Ray, R. R., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Emotion elicitation using films. In J. A. Coan & J. J. B. Allen (Eds.), The handbook of emotion elicitation and assessment (pp. 9–28). Oxford University Press.

- Russell, J. A., & Barrett, L. F. (1999). Core affect, prototypical emotional episodes, and other things called emotion: Dissecting the elephant. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 76(5), 805–819. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.76.5.805

- Russell, J. A., Weiss, A., & Mendelsohn, G. A. (1989). Affect grid: A single-item scale of pleasure and arousal. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57(3), 493–502. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.3.493

- Salas, C. E., Radovic, D., & Turnbull, O. H. (2012). Inside-out: Comparing internally generated and externally generated basic emotions. Emotion, 12(3), 568–578. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025811

- Schmider, E., Ziegler, M., Danay, E., Beyer, L., & Bühner, M. (2010). Is it really robust?: Reinvestigating the robustness of ANOVA against violations of the normal distribution assumption. Methodology, 6(4), 147–151. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1027/1614-2241/a000016

- Spielberger, C. D. (1991). State-Strait Anger Expression Inventory revised research edition: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources Inc.

- Statsoft. (2010). Statistica (Version 9) [Computer Software].

- Teasdale, J. D., & Taylor, R. (1981). Induced mood and accessibility of memories: An effect of mood state or of induction procedure? British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 20(1), 39–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8260.1981.tb00494.x

- Totan, T. (2014). Distinctive characteristics of flourishing, self-esteem, and emotional approach coping to mood. International Online Journal of Educational Sciences, 6(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.15345/iojes.2014.01.004

- Unsworth, G., Devilly, G. J., & Ward, T. (2007). The effect of playing violent video games on adolescents: Should parents be quaking in their boots? Psychology, Crime and Law, 13(4), 383–394. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10683160601060655

- Van Damme, I. (2012). Mood and the DRM paradigm: An investigation of the effects of valence and arousal on false memory. The Quarterly Journal of Experimental Psychology, 66(6), 1060–1081. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17470218.2012.727837

- Westermann, R., Spies, K., Stahl, G., & Hesse, F. W. (1996). Relative effectiveness and validity of mood induction procedures: A meta-analysis. European Journal of Social Psychology, 26(4), 557–580. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/(sici)1099-0992(199607)26:4<557::aid-ejsp769>3.0.co;2-4