ABSTRACT

Objective

Older adults are vulnerable to isolation and poor emotional wellbeing during COVID-19, however, their access to appropriate supports is unknown. The aim of this study was to explore older adults’ experiences accessing social and emotional support during the COVID-19 pandemic in Australia.

Method

Ten older adults from Western Australia (Australia) aged 68 to 78 years participated in individual semi-structured interviews between December 2020 and January 2021. Responses were investigated using thematic analysis.

Results

Three key themes emerged: adaptability and self-sufficiency; informal support-seeking; and digital and online technologies. Older adults were adaptable to COVID-19 restrictions; however, some were anxious about reconnecting with their social networks once restrictions had eased. Older adults relied on their informal support networks to maintain their social and emotional wellbeing during lockdown. Digital platforms (e.g., Zoom, social media) enabled older adults to stay connected with others, yet some older people were unable or reluctant to use technology, leaving them vulnerable to social isolation.

Conclusions

Older adults are resilient to the challenges of COVID-19. Informal supports and digital technologies are important to maintaining social and emotional wellbeing during lockdown. Local governments and community groups may benefit from increased funding to deliver services that promote social connectedness during times of crisis.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

(1) Older adults are vulnerable to social isolation and poor mental health during COVID-19.

(2) Older adults are less likely to seek and receive help for their emotional and social health than younger age groups.

(3) Barriers to accessing appropriate supports include physical health problems, stigma, negative attitudes towards help-seeking and system-level factors.

What this topic adds:

(1) Older adults were able to adapt well to COVID-19 restrictions and relied on informal supports to maintain their wellbeing.

(2) Older adults with limited social networks and poor access to and/or knowledge of digital technologies are at the greatest risk of social and emotional declines.

(3) Telephone “warm” lines, volunteering opportunities, and programs to improve digital literacy may help to protect older adults’ social and emotional wellbeing during times of crises.

Introduction

Elevated rates of psychological distress have been reported globally since COVID-19, and older adults are one of the groups most vulnerable to isolation and psychosocial harms during- and post-pandemic (Usher et al., Citation2020). In Australia, people aged 70+ and those with chronic medical condition(s) aged 60+ have been advised to self-isolate during COVID-19 due to their increased risk of serious illness and death if they contract the virus (Healthdirect, Citation2021; Xiong et al., Citation2020). Such restrictions can have a profound impact on older adults’ social and emotional wellbeing, leading to loneliness and social isolation (Smith et al., Citation2020; Wu, Citation2020). This can result in higher rates of anxiety and depression, lower quality of life, and increased complications of pre-existing health conditions (Ogrin et al., Citation2021; Sepúlveda-Loyola et al., Citation2020).

Due to self-isolation, the dynamics of social support networks that older adults relied on changed during COVID-19, most obviously through decreased face-to-face contact with their networks. Social support, defined as the “support accessible to an individual through social ties to other individuals, groups and the larger community”, can be further divided into formal and informal support depending on who is delivering the support (Lin et al., Citation1979). Formal support is support provided by organisations or individuals that are governed by laws or policies such as a general practitioner (GP), psychologists, counsellors or therapists. Informal is provided by informal organisations or groups such as include recreational or spiritual groups, family members, or neighbours. Irrespective of the type of support provided, social support has been shown to have a positive impact on the health and wellbeing of older adults and a lack of support has been shown to increase anxiety and depression in older adults (Shen et al., Citation2022; Zhao et al., Citation2022).

Understanding older adults’ social and emotional support needs during COVID-19, and access to appropriate supports, is crucial to protecting their wellbeing and informing service delivery, now and in future times of crisis. This is particularly evident given the challenges in delivering and accessing health and social services during COVID-19 (Bhome et al., Citation2021). Older adults often experience greater barriers to healthcare access than younger age groups, regardless of the events of the global pandemic (Choi & Gonzalez, Citation2005; Pywell et al., Citation2020). Older adults are also less likely to seek and receive support for their mental and social health (Lavingia et al., Citation2020; Solway et al., Citation2010). Much of the research on COVID-19 has been on the extent older adults’ experienced poor mental health, social isolation and their access to services (Giebel et al., Citation2021; Sepúlveda-Loyola et al., Citation2020; Wong et al., Citation2020). Few studies have explored older adults’ personal experiences accessing social and emotional support during the pandemic. Studies that have investigated this relationship delivered surveys and found perceived social support was related to lower levels of psychological wellbeing and depression (Levkovich et al., Citation2021; Su et al., Citation2022). However, insight into the lived experiences of older adults managing their social and emotional wellbeing during COVID-19 and navigating formal and informal support systems is lacking. Such knowledge is important to ensure any action taken to better support older people reflects their day-to-day needs.

The aim of the present study was to explore older adults’ experiences accessing social and emotional support during COVID-19. The research question was: How did older adults maintain their social and emotional wellbeing during the 2020 COVID-19 restrictions in Western Australia (WA), Australia?

Materials and methods

Setting

The 2020 COVID-19 restrictions in WA were imposed between mid-March and early-June 2020. During this time, the state government implemented social and work restrictions and advised older adults aged 70+ and those with chronic medical condition(s) aged 60+ to stay at home to reduce their risk of infection. This period became known as a “lockdown”, and we refer to it as such throughout this paper.

Study design and participants

The study uses interpretative phenomenology as its approach and interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) for data analysis. We conducted qualitative semi-structured interviews with older adults as our primary method of data collection. Duranti (Citation2010) argues that social worlds are accessible through interpretative phenomenology due to the fundamentally social nature of lived experience (Duranti, Citation2010). An interpretative phenomenological approach thus recognises the value of in-depth interviews to provide insight into interviewees’ lived experiences (Smith & Osborn, Citation2015).

Inclusion criteria for participants were adults aged 70+ years or 60+ years with chronic health conditions living in WA, Australia. Participants were excluded if they were not fluent in English or if they had cognitive impairments, as sufficient memory recall was required to reflect on the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown.

Consumer participation

A consumer reference group (CRG) was established, comprising eight older adults, who informed on the design and conduct of the research, interpretation of results, and research dissemination tools. Consumer groups have a key role in research by ensuring community needs are met, improving trust and confidence in research findings, and improving translation of research outcomes (Brett et al., Citation2014; Domecq et al., Citation2014). The CRG in this project provided the research team with community and consumer perspectives on the research design, study materials, provided links between community, consumers and researchers, and advocated on behalf of older adults in the community. The CRG met with the research team throughout the project and provided input into all stages of the research process. During the design phase, the CRG co-developed the information letter, consent form, and interview schedule with the researchers. Once data had been collected, key themes were discussed with the CRG and they provided insights into credibility of these themes. The CRG also had a key role in the development of an infographic for dissemination. Additional information on the role of the CRG in this research can be found in (Adams et al., Citation2022).

Procedure

Participants were recruited through flyers shared with service providers throughout WA, through word-of-mouth and via snowball recruiting. Potential participants were initially screened via telephone for suitability according to our inclusion and exclusion criteria, and a time, date and place was set with the individual if they were deemed eligible to participate. Recruitment in the study ceased once data saturation had been reached (i.e., no new data was forthcoming from interviews).

Data were collected between December 2020 and January 2021. Interviews were conducted via Zoom, telephone, or face-to-face, ensuring that the interviewer (Author 1) followed the necessary COVID-19 management protocols. The average length of interviews was 40 minutes. The semi-structured interview schedule explored participants’ experiences during the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown including ways they maintained their social and emotional wellbeing. Questions included “What sort of personal support network did you have before, during, and after the lockdown?” and “How familiar are you with emotional or social support services that are available?”, for example.

Data analysis

Interviews were transcribed verbatim by a third-party transcription service and imported into NVivo for analysis. Interpretative phenomenological analysis (IPA) was used to analyse the data. IPA involves understanding ones lived experiences and is interested in major life events (Howitt, Citation2016). Author 1 analysed data initially, first reading transcripts closely and in full and taking notes. Author 1 then coded each interview in NVivo to capture salient themes within and across participant’s testimonies. Codes were then grouped into larger themes based on the research question. Author 1 discussed the themes with the research team to enhance rigour, and explore the interpretation. After clarifying the queries on interpretation, the resulting themes were agreed upon by the research team and the reference group. Quotes are provided throughout the results section and in the supporting document additional quotes are provided (Supporting Table S1).

Ethical consideration

Information for the study was discussed in an initial screening call and via email with the participant, to ensure that they understood the terms of their participation in the study. Written, informed consent was either provided by email or in person before the recorded interview commenced and after any questions or concerns from the participant had been addressed to their satisfaction. Participants were made aware they could cease the interview at any time without any penalty. All participants were given a post-interview debrief and, if needed, a referral to their GP. Anonymity was assured to all participants as a condition of their participation. The interviewer maintained this anonymity by labelling all data files according to a confidential code and removing all reference to personal details (including names, places) from transcripts. Ethics approval was obtained through the Edith Cowan University Human Ethics Committee (2020–01693-STROBEL).

Results

Participant characteristics are presented in .

Table 1. Characteristics of participants.

Overview of participants

We recruited 10 participants aged between 68 and 78 years. An even gender distribution was obtained, and 90% (n = 9) of participants lived with at least one chronic health condition. Most participants (n = 7) had obtained a tertiary qualification, and all were able to make ends meet either always (n = 7) or most of the time (n = 3). Most participants were married and living with their spouse (n = 8). Most participants (n = 7) had accessed mental health services in their lifetime; however, only 40% (n = 4) had accessed such services in the two years prior to 2021, and no participants accessed mental health services during the pandemic. See for further participant characteristics.

Overview of themes

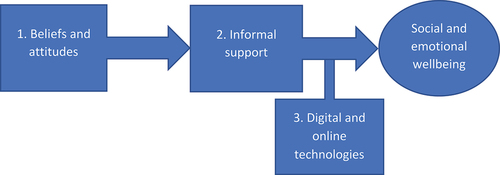

We sought to understand older adults’ experiences accessing social and emotional support during the COVID-19 state-wide lockdown in 2020. We found that respondents’ beliefs and attitudes about adaptability and resilience informed their likelihood of seeking help from either formal or informal supports, and that participants often sought informal social connection instead of formal services when they experienced distress. As such, we explored the role of informal support in participants’ lives as it arose inductively in the interviews. We found that strong social support networks reduced the need for accessing formal services, and where need persisted these networks and GPs provided assistance to seek help. Our sample thus provides insight into how older adults seek and utilise their social networks to improve their wellbeing.

Data were organised into three key themes (as illustrated in ):

Figure 1. The diagram shows how the three key themes are interrelated. Arrows represent respondents’ agency and actions taken towards improving their social and emotional wellbeing.

Participants’ beliefs and attitudes about adaptability and self-sufficiency informed their likelihood of reaching out or seeking help;

How older adults facilitated social connectedness by seeking support through their informal networks, such as family, friends and neighbours;

The role of digital and online technologies as both barriers and facilitators of social connectedness.

Participants also made recommendations for future periods of crisis. We summarise these recommendations under sub-heading 4: Recommendations.

Key theme 1: adaptability and self-sufficiency

Participants’ ability to adapt to COVID-19 restrictions affected their social and emotional wellbeing. Some participants were pragmatic about the lockdown and reported coping as best they can and then moving on with their lives:

You exist within the situation you are in, cope with it as well as you can, when things improve you can move on out. Until things improve, you stay calm, quiet and considerate, that’s how I look at it anyway, and I’m going to stay that way. The farm and the army taught me that, that’s my creed in life I suppose you could say.

While others were more concerned about the emotional wellbeing of those around them, and coped by offering support rather than receiving it:

I felt that I should be the strong one … I did see myself as the support rather than the supported in that sense, because others had more extreme issues to deal with.

Participants who viewed the lockdown as an opportunity to reconnect with themselves and their family enjoyed their time at home:

We’re used to being in our own environment and our own thing, we didn’t miss out on, really, social interaction that much. Not that we’re hermits …

However, others had anxiety around leaving home and were hesitant to reconnect with their social networks once restrictions had eased:

I have noticed a number of people who I knew that were very active, socially… When they went into lockdown, they found it quite comfortable, and didn’t want to come out of it … a lot of them have got so comfortable, that they don’t want to come out of their shell.

Beliefs about self-sufficiency also informed how participants were able to cope; some participants felt their beliefs about maintaining independence and self-reliance are common across their generation, which informed their unwillingness to seek social and emotional support from formal services:

I haven’t experienced any [anxiety around COVID-19], and I didn’t know any from other people. It’s just a matter of these things occur, and you have to adapt and move on, that’s what older people have had to do in our lives, adapt and move on.

Key theme 2: informal support-seeking

Participants relied more on informal social networks than on formal services throughout the 2020 COVID-19 lockdown. Participants cited family and friends as the most important source of support during this time. Neighbours and community groups also provided support, including volunteer, recreational, and religious groups. For those who were single, widowed, and/or without children, extended social networks provided crucial support throughout lockdown.

The establishment and maintenance of trust is key to emotional and social support for older adults. Participants established trust with those who shared common ground (e.g., through culture, language, religion, location) and such connections provided safety to reach out, where needed:

For [my mother], she needed community members who spoke her language, who could go in and have a cup of coffee with her or say a prayer with her. That’s what she needed, and that would open up other doors for her. The formal helping services wouldn’t help her … the community, they’re the bridge. Without that community, they don’t trust … the community and the carer are very important.

As participant A01 describes, informal social networks often operated as “the bridge” to formal services; providing a means of support for those who were otherwise isolated, who lacked informal support systems, or who were reluctant to seek formal support. Conversely, a lack of trust in services is seen as a barrier to access:

My sister, she doesn’t trust a lot of these [mental health services]. My sister has got serious mental health issues … she doesn’t trust a lot of these telephone services. I don’t know why … But she trusts [service X], and she trusts the one that she’s been to in [place].

Participants also provided insight into the role of general practitioners (GPs) as a crucial facilitator of support and reliable source of information:

I don’t know [about social and emotional support services], just go to my doctor if I need something.

Participants viewed neighbours and community groups as particularly impactful during the lockdown, especially to those without local family networks and at risk of isolation:

My family are all interstate, or overseas, and so, lockdown was not an easy time. I found it very challenging … I felt very isolated from everybody … My emotional support comes from family, and some very good friends … I talk to them every week, more than once … I can [also] go across the road to neighbours next door, and behind me. I’ve not felt the need for any formal [support].

I’ve always known my neighbours … We have each other’s numbers. So the lifesaver for me, was being able to still go out into the park and walk … I would still meet a friend, who also lives on her own, and we would walk …

Due to the substantive role of informal support in providing social and emotional wellbeing, participants recommended the provision of informal support to be expanded, such as establishing local telephone “warm” lines designed to meet older adults’ social needs. We discuss this in further detail under heading 4.4: Recommendations.

Key theme 3: digital and online technologies

Prior to the COVID-19 lockdown, many participants relied on in-person social groups to maintain their social and emotional wellbeing. The 2020 COVID-19 lockdown presented challenges on how to maintain social connections through other means. Digital and online technologies became crucial to the social and emotional lives of participants to circumvent social isolation. Participants often held conflicting views regarding the value of online platforms in maintaining social connections and accessing services.

Facilitator to social connection and services

Many participants felt online and digital technologies (e.g., Zoom, social media) enabled them to connect with loved ones and continue their religious practices:

A lot of my friends are all over Australia, as well as in WA, so, lots of Zoom meetings where we caught up about social issues, not only work issues, and that was nice.

[Social media] for me is the lifesaver … I have spent more time than I can think, this year, on FaceTime, and Zoom … that has at least let me keep in touch with everybody. We’re a close family anyway, but we’ve all made even more effort this year

As indicated above, and especially for those who already relied on these platforms for work, participants found digital and online technologies to be a weak alternative for face-to-face connection. Online fatigue played a role:

When I got up to 475 Zoom meetings during the COVID period I was well and truly Zoomed out, and I certainly didn’t want to add in extra ones for social … I don’t like [Zoom] … but I guess I had to adapt to because that was the only way that I could keep things going.

I’m quite comfortable with Zoom [as opposed to other platforms] … [but] I don’t like it … there’s no opportunity for networking, or sharing ideas, and that type of thing. There’s nothing that beats face to face meeting.

Some older adults required assistance to adopt digital and online technologies. One participant recalled helping her father connect with his friends through FaceTime, and how important this was for his social and emotional wellbeing. FaceTime provided valuable social connection throughout the lockdown period that he would have otherwise not experienced without his family’s assistance:

“As soon as [lockdown] happened, we raced over to Pop’s place and said to him, ‘give us your iPad’. And we set him up on FaceTime, with us. But we said to him, ‘tell us all your friends that you want to talk to’. So, we set him up with all his friends. And we rang them that day and made sure … that they knew he had it, and that it was actually working. And for him, that’s been a godsend. And for us too. Yes. Because our grandkids have got into the habit now, if they want to say something to us, they just FaceTime us”.

Participants also reported the use of such technologies for formal services saved time that would otherwise be spent travelling to appointments:

I’m not a big fan of Zoom, but it is convenient, and it was great with my specialist, because I used to have to see him on a Tuesday, which is my bowling day, so it would wipe out a whole day of bowls …

Barrier to social connection and services

Some participants did not have access to the internet or were uncomfortable using technologies, which limited their opportunities for networking and restricted access to accurate and current information. These participants reported anxieties about technology as they did not know how to use them and/or could not afford them:

Early in the piece I saw something that said there was concern about people using Zoom, so I thought no I won’t bother to try and start using it, so I didn’t. I only use the computer to see what comes in, and occasionally send something out, but usually when I see whatever comes in, otherwise I don’t do much on the computer. I’m not much on it, I’m a very slow typist, so I don’t type much.

Recommendations

During interviews participants provided recommendations on how to support older peoples social and emotional wellbeing. Quotes to support these recommendations are provided in Table S2 of the Supplement. The recommendations were:

(1) Telephone warm line for older adults

They would provide an avenue for older adults to reach out to another person before reaching the level of psychological distress requiring a crisis line.

(2) Provide direct assistance for older adults to get online

Due to the importance of digital and online technologies for affording social connectedness to older adults, participants recommended providing direct assistance to older adults to adopt digital technologies and get online.

(3) Better coordinating local volunteers

Volunteers were crucial in providing informal support to older adults. Participants felts that a greater coordination of volunteers meant that there was less risk of social isolation occurring.

Discussion

Our study aimed to explore older adults’ experiences accessing social and emotional support during COVID-19. We interviewed ten older adults in WA and found overall that older adults were resilient, able to adapt to lockdowns, draw on their social networks for support, and use online and digital technologies to support their social and emotional wellbeing during COVID-19. However, many people also experienced difficulties with using online technologies and felt this was a barrier to social connectedness. These results are consistent with other research in this area that suggests older adults are resilient and often engaged in proactive coping during COVID-19 (Fuller & Huseth-Zosel, Citation2021; Strutt et al., Citation2022). The results are also consistent with our CRG member’s experiences personally and within their communities during the pandemic.

The dominant role of informal social support was an important finding of our research. Many studies investigated the relationship of informal caregivers in providing support to their partners, with studies showing that this relationship was highly impacted by COVID-19, especially for caregivers (Baik et al., Citation2022; Lion et al., Citation2022) Indeed, some of our participants acted as important supports to family members who had a strong distrust of formal support systems. In our study, people relied on their families and social networks to keep socially connected during isolation. Informal networks through sporting and religious groups, and neighbours, were particularly important when people did not have a family network around them. However, our participants were aware that some people had limited people or no informal supports. A “warm line” was considered a way of mitigating increased loneliness and providing people with the opportunity to talk to someone and reduce levels of social isolation. This recommendation was endorsed by our CRG.

The present findings suggest access to informal supports help maintain connectedness, and digital technologies are a protective factor against social isolation for those able and willing to use them. Indeed, the use of digital technologies amongst older adults during COVID-19 has been of great benefit not only for maintaining and improving social support and connectedness but also for health outcomes such as physical activity (Kirwan et al., Citation2022). However, there have been several barriers cited in the literature that prohibit the effective use of digital technologies, including those who do not have a wide social network, whose access to the internet is limited, who do not know how to use digital technologies, who lack the funds to buy an appropriate device or those with cognitive impairment (Gauthier et al., Citation2022; Hall Dykgraaf et al., Citation2022; Murciano-Hueso et al., Citation2022). These barriers were also articulated by participants in our study. Recommendations to develop older adults digital literacy and working with informal and formal support systems to improve access and uptake of digital technologies is echoed throughout the literature and our studies highlights the continued need for such services among older Australians (Angel & Mudrazija, Citation2020; Murciano-Hueso et al., Citation2022).

A key strength of this study is the establishment of a CRG who informed the design and implementation of this research, increasing the accuracy of our interpretations and relevance of our findings. The results from this study have been used to inform a survey on access to mental health and social support services that was disseminated to a broader sample of older adults living in WA, and may inform future research in this area to improve our understanding of older adults social and emotional support needs and interventions to target such needs (Adams et al., CitationUnder review). A limitation of this study is that participants had high educational attainment and were predominantly living with a partner. Previous research indicates this sample may be at lower risk of mental and social declines due to having a higher education level and being partnered. These factors have been shown to be a protective factor against psychosocial decline (Niemeyer et al., Citation2019; van Gaans & Dent, Citation2018). Sampling bias occurred whereby despite our efforts we were unable to recruit a diverse group of participants. In particular, we did not have any minority groups such as culturally and linguistically diverse community members, people who were highly impacted from COVID-19 or who had poor mental health during the period of social isolation. Future research may benefit from targeting older adults from diverse backgrounds, who may experience different inequalities in access to formal and informal supports, to better understand the support needs of these groups (Solway et al., Citation2010; van Gaans & Dent, Citation2018).

This paper has important implications for services providers in Western Australia and in other regions. Firstly, given older adults relied on informal supports to maintain their social and emotional wellbeing during COVID-19, opportunities to enhance community participation and connectedness are important to older adults’ wellbeing, and can be provided through local governments and community organisations. Services to improve older people’s digital literacy are pivotal to preventing social and emotional declines, given the modern day reliance on digital technologies to stay connected with others. To facilitate the translation of our findings in WA, we co-developed with our CRG infographics to disseminate the findings to community organisations (Adams et al., Citation2022). The aim of the infographics was to share with the community and local organisations how older adults coped with social isolation during the pandemic and how they can best support people in their community to build and maintain social and emotional wellbeing. This can help to inform service provision and identify target areas for funding. These findings and practice implications are of particular relevance now, as our communities recover from the height of the pandemic, and will help us to better prepare for future crises. A copy of the infographics are provided in Appendix 1.

Conclusions

This study demonstrates the role of informal support networks and digital technologies in maintaining social and emotional wellbeing during COVID-19. There is an opportunity for local governments and community groups to promote social connectedness among older adults to better prepare for times of increased social isolation.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge our CRG members Paul Albert, Tim Benson, Anne Cordingley, Barbara Daniels, Noreen Fynn, Mary Gurgone, Chris Jeffery and Ann White. All members contributed equally and are highly valued.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Dr Natalie Strobel, upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00049530.2022.2141584.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, C., Albert, P., Benson, T., Cordingley, A., Daniels, B., Fynn, N., Gurgone, M., Jeffery, C., White, A., & Strobel, N. (2022). The realities and expectations of community involvement in COVID-19 research: A Consumer Reference Group perspective. Research Involvement and Engagement, 8(1), 54. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40900-022-00389-z

- Adams, C., Gringart, E., McAullay, D., Sim, M., Scarfe, B., Budrikis, A., & Strobel, N. (Under review). Older adults access to mental health and social care services during COVID-19 restrictions in Western Australia.

- Angel, J. L., & Mudrazija, S. (2020). Local government efforts to mitigate the novel coronavirus pandemic among older adults. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 32(4–5), 439–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2020.1771240

- Baik, D., Coats, H., & Baker, C. (2022). Experiences of older family care partners of persons with heart failure 1 year after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic: A qualitative study. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 48(10), 47–52. https://doi.org/10.3928/00989134-20220908-07

- Bhome, R., Huntley, J., Dalton-Locke, C., San Juan, N. V., Oram, S., Foye, U., & Livingston, G. (2021). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on older adults mental health services: A mixed methods study. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 36(11), 1748–1758. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.5596

- Brett, J., Staniszewska, S., Mockford, C., Herron-Marx, S., Hughes, J., Tysall, C., & Suleman, R. (2014). A systematic review of the impact of patient and public involvement on service users, researchers and communities. The Patient - Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 7(4), 387–395. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40271-014-0065-0

- Choi, N. G., & Gonzalez, J. M. (2005). Barriers and contributors to minority older adults’ access to mental health treatment. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 44(3–4), 115–135. https://doi.org/10.1300/J083v44n03_08

- Domecq, J. P., Prutsky, G., Elraiyah, T., Wang, Z., Nabhan, M., Shippee, N., Brito, J. P., Boehmer, K., Hasan, R., Firwana, B., & Erwin, P. (2014). Patient engagement in research: A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 89. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-14-89

- Duranti, A. (2010). Husserl, intersubjectivity and anthropology. Anthropological Theory, 10(1–2), 16–35. https://doi.org/10.1177/1463499610370517

- Fuller, H. R., & Huseth-Zosel, A. (2021). Lessons in resilience: Initial coping among older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Gerontologist, 61(1), 114–125. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa170

- Gauthier, A., Lagarde, C., Mourey, F., & Manckoundia, P. (2022). Use of digital tools, social isolation, and lockdown in people 80 years and older living at home. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(5), 2908. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19052908

- Giebel, C., Pulford, D., Cooper, C., Lord, K., Shenton, J., Cannon, J., Shaw, L., Tetlow, H., Limbert, S., Callaghan, S., & Whittington, R. (2021). COVID-19-related social support service closures and mental well-being in older adults and those affected by dementia: A UK longitudinal survey. BMJ Open, 11(1), e045889. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2020-045889

- Hall Dykgraaf, S., Desborough, J., Sturgiss, E., Parkinson, A., Dut, G. M., & Kidd, M. (2022). Older people, the digital divide and use of telehealth during the COVID-19 pandemic. The Australian Journal of General Practice, 51(9), 721–724. https://doi.org/10.31128/ajgp-03-22-6358

- Healthdirect. (2021). COVID-19 information for older Australians. https://www.healthdirect.gov.au/coronavirus-covid-19-information-for-older-australians-faqs

- Howitt, D. (2016). Introduction to qualitative research methods in psychology (3rd ed.). Pearson Education.

- Kirwan, M., Chiu, C. L., Laing, T., Chowdhury, N., & Gwynne, K. (2022). A web-delivered, clinician-led group exercise intervention for older adults with type 2 diabetes: Single-arm pre-post intervention. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 24(9), e39800. https://doi.org/10.2196/39800

- Lavingia, R., Jones, K., & Asghar-Ali, A. A. (2020). A systematic review of barriers faced by older adults in seeking and accessing mental health care. Journal of Psychiatric Practice, 26(5), 367–382. https://doi.org/10.1097/pra.0000000000000491

- Levkovich, I., Shinan-Altman, S., Essar Schvartz, N., & Alperin, M. (2021). Depression and health-related quality of life among elderly patients during the COVID-19 pandemic in Israel: A cross-sectional study. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 12, 2150132721995448. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150132721995448

- Lin, N., Ensel, W. M., Simeone, R. S., & Kuo, W. (1979). Social support, stressful life events, and illness: a model and an empirical test. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 20(2), 108–119. https://doi.org/10.2307/2136433

- Lion, K. M., Moyle, W., Cations, M., Day, S., Pu, L., Murfield, J., Gabbay, M., & Giebel, C. (2022). How did the COVID-19 restrictions impact people living with dementia and their informal carers within community and residential aged care settings in Australia? A qualitative study. Journal of Family Nursing, 28(3), 205–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/10748407221101638

- Murciano-Hueso, A., Martín-García, A. V., & Cardoso, A. P. (2022). Technology and quality of life of older people in times of COVID: A qualitative study on their changed digital profile. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(16), 10459. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191610459

- Niemeyer, H., Bieda, A., Michalak, J., Schneider, S., & Margraf, J. (2019). Education and mental health: Do psychosocial resources matter? SSM Population Health, 7, 100392. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2019.100392

- Ogrin, R., Cyarto, E. V., Harrington, K. D., Haslam, C., Lim, M. H., Golenko, X., Bush, M., Vadasz, D., Johnstone, G., & Lowthian, J. A. (2021). Loneliness in older age: What is it, why is it happening and what should we do about it in Australia? Australasian Journal on Ageing, 40(2), 202–207. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajag.12929

- Pywell, J., Vijaykumar, S., Dodd, A., & Coventry, L. (2020). Barriers to older adults’ uptake of mobile-based mental health interventions. Digit Health, 6, 2055207620905422. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207620905422

- Sepúlveda-Loyola, W., Rodríguez-Sánchez, I., Pérez-Rodríguez, P., Ganz, F., Torralba, R., Oliveira, D. V., & Rodríguez-Mañas, L. (2020). Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: Mental and physical effects and recommendations. The Journal of Nutrition, Health & Aging, 24(9), 938–947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12603-020-1500-7

- Shen, T., Li, D., Hu, Z., Li, J., & Wei, X. (2022). The impact of social support on the quality of life among older adults in China: An empirical study based on the 2020 CFPS. Front Public Health, 10, 914707. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2022.914707

- Smith, J., & Osborn, M. (2015). Interpretative phenomenological analysis as a useful methodology for research on the lived experience of pain. British Journal of Pain, 9(1), 41–42. https://doi.org/10.1177/2049463714541642

- Smith, M., Steinman, L., & Casey, E. (2020). Combatting social isolation among older adults in a time of physical distancing: The COVID-19 social connectivity paradox. Frontiers in Public Health, 8, 403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00403

- Solway, E., Estes, C. L., Goldberg, S., & Berry, J. (2010). Access barriers to mental health services for older adults from diverse populations: Perspectives of leaders in mental health and aging. Journal of Aging & Social Policy, 22(4), 360–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959420.2010.507650

- Strutt, P. A., Johnco, C. J., Chen, J., Muir, C., Maurice, O., Dawes, P., Siette, J., Botelho Dias, C., Hillebrandt, H., & Wuthrich, V. M. (2022). Stress and coping in older Australians during COVID-19: Health, service utilization, grandparenting, and technology use. Clinical Gerontologist, 45(1), 106–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1884158

- Su, C., Yang, L., Dong, L., & Zhang, W. (2022). The psychological well-being of older Chinese immigrants in Canada amidst COVID-19: The role of loneliness, social support, and acculturation. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(14), 8612. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19148612

- Usher, K., Bhullar, N., & Jackson, D. (2020). Life in the pandemic: Social isolation and mental health. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(15–16), 2756–2757. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15290

- van Gaans, D., & Dent, E. (2018). Issues of accessibility to health services by older Australians: A review. Public Health Reviews, 39(1), 20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40985-018-0097-4

- Wong, S. Y. S., Zhang, D., Sit, R. W. S., Yip, B. H. K., Chung, R. Y., Wong, C. K. M., Chan, D. C., Sun, W., Kwok, K. O., & Mercer, S. W. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 on loneliness, mental health, and health service utilisation: A prospective cohort study of older adults with multimorbidity in primary care. British Journal of General Practice, 70(700), e817–824. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp20X713021

- Wu, B. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness among older adults in the context of COVID-19: A global challenge. Global Health Research and Policy, 5(1), 27. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41256-020-00154-3

- Xiong, J., Lipsitz, O., Nasri, F., Lui, L. M. W., Gill, H., Phan, L., Chen-Li, D., Iacobucci, M., Ho, R., Majeed, A., & McIntyre, R. S. (2020). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health in the general population: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 277, 55–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2020.08.001

- Zhao, L., Zheng, X., Ji, K., Wang, Z., Sang, L., Chen, X., Tang, L., Zhu, Y., Bai, Z., & Chen, R. (2022). The relationship between social support and anxiety among rural older people in elderly caring social organizations: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(18), 11411. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph191811411