ABSTRACT

Objective

Bullying victimisation is well known to be associated with social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder among adolescents. Study 1 reports on a systematic review to examine these relationships. Study 2 employed a survey to investigate the relationship between overt, reputational, and relational bullying with self-endorsement of social anxiety disorder, generalised anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Method

Study 1 consists of a systematic review of the literature published between 2011 and 2021. Multiple sources were used to identify potentially eligible studies using keywords in varying combinations and the PRISMA guidelines were followed. The quality of included studies was assessed using a critical appraisal tool. Study 2 collected data through an online questionnaire completed by 338 high-school students aged 12–18 years.

Results

Study 1 demonstrated that bullying victimisation research limits anxiety outcomes to social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder. Results also demonstrated that overt and covert bullying types are typically not defined. Study 2 found that covert bullying types (reputational and relational) uniquely predicted increased levels of all anxiety subtypes, while overt bullying did not. Relational bullying was the best predictor of all anxiety subtypes, except obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Conclusion

These results suggest the need to consider different types of bullying and the need to assess anxiety subtype symptoms more broadly.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about the topic:

Bullying-victimisation is associated with social anxiety disorder and general anxiety disorder among adolescents.

Previous research has identified three bullying victimisation subtypes; overt, and two covert types being reputational and relational.

Covert bullying victimisation is more strongly related to depression and social anxiety symptomology than overt.

What this topic adds:

Overt bullying victimisation does not predict self-endorsement of generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Covert bullying victimisation predicts separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Subtypes of bullying victimisation demonstrate unique relationships with a range of anxiety disorder symptomology beyond that of generalised anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder.

The detrimental effects of bullying victimisation on the mental health of adolescents have been studied for the past 30 years resulting in a vast amount of literature on the topic (Hawker & Boulton, Citation2000; Moore et al., Citation2017). It is now well evidenced that being a victim of bullying during adolescence is associated with a myriad of physical and mental health concerns, including increased levels of depression, anxiety, and psychosomatic symptomology (Moore et al., Citation2017), as well as decreased school engagement (Hawker & Boulton, Citation2000). Considering that anxiety is the most commonly experienced mental health disorder among Australian adolescents (Australian Insitute of Health and Welfare, Citation2021) and adolescents globally (World Health Organisation, Citation2022), the association between bullying victimisation and anxiety is of concern.

Unfortunately, the vast majority of studies to date have limited anxiety outcomes to social anxiety disorder and less commonly, generalised anxiety disorder (Hawker & Boulton, Citation2000). This has resulted in a gap in the literature as the relationships between bullying victimisation and other anxiety disorders commonly experienced during adolescence, specifically panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and separation anxiety disorder remain unknown (The Australian Government, Citation2015; The Department of Health, Citation2005).

A second gap in the literature has emerged as despite increased awareness that some types of bullying are more detrimental than others (Ferraz de Camargo & Rice, Citation2020; Siegel et al., Citation2009), bullying typically continues to be defined as a single construct (Moore et al., Citation2017). This has resulted in a lack of detailed understanding of these relationships that is crucial for the development of targeted psychological intervention and treatment. As such, this investigation into the relationships between types of bullying and types of anxiety will aim to address two identified gaps in the literature. Study 1 aims to conduct a systematic review of the literature to ascertain the extent to which bullying victimisation has been studied in relation to separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, social anxiety disorder, and generalised anxiety disorder symptomology. Study 2 aims to extend past research by exploring the relationship between three types of bullying victimisation being overt, and two covert types (reputational and relational) and symptomology associated with generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. This research offers important practical implications for practitioners involved in the assessment and treatment of adolescent mental health and may offer much needed support for bullying victims.

Bullying victimisation and links with anxiety

Bullying victimisation and anxiety are both common experiences during adolescence (Jadambaa et al., Citation2020). Approximately one in four Australian school students aged 8–14 years report being victims of bullying (Ford et al., Citation2017). Further, a survey of 10, 273 12–16 year old Australian students found 31% were victims of verbal bullying, 11% physical bullying, 14% were subjected to rumour spreading, and 14% were socially excluded (Thomas et al., Citation2016). However, the covertness of the bullying in these estimates is often not clarified. Prevalence estimates of anxiety disorders are also high with a survey of over 6,300 Australian families finding that 7% of Australian adolescents experienced one or more anxiety disorder within a 12-month period. The same study found social anxiety disorder and separation anxiety to be equally prevalent at 3.4%, followed by generalised anxiety disorder at 2.9% and obsessive-compulsive disorder at 0.8% (The Australian Government, Citation2015). Research suggests that these experiences are inextricably related (Moore et al., Citation2017), with bullying victimisation recognised as a risk factor for anxiety in the (Global Burden of Disease, Citation2017) study for the first time (Stanaway et al., Citation2018). Bullying victimisation was found to be the leading risk factor for mental disorder associated disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) and the 35th leading risk factor of all 54 risks for all non-communicable diseases (NCDs) in 2017 (Stanaway et al., Citation2018).

Bullying victimisation and anxiety subtypes

The ongoing trend of limiting outcomes to social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder, may be due to bullying victimisation being conceptualised as a social problem that is expected to impact social relationships (Swearer & Hymel, Citation2015). It is true that the definition of bullying highlights the impact on social relationships such persistent intent to cause damage to personal relationships through social isolation and exclusion, and deliberate and harmful manipulation of social bonds (Siegel et al., Citation2009). Additionally, bullying involves an imbalance of power between the victim and the perpetrator that the victim struggles to combat (Çoban et al., Citation2021; Olweus, Citation1978; Putallez et al., Citation2007; Siegel et al., Citation2009). However, Olweus (Citation1993) empathises that the three criteria, being 1. Intent to harm, 2. Repetitive, and 3. Imbalance of power, characterise bullying as an experience of chronic trauma. This is in line with later commentary that bullying is an interpersonal trauma (Idsoe et al., Citation2012). Conceptualising bullying victimisation as a traumatic event shifts the focus from the impact on social relationships to the associated response of perceived threat, the emotional response of fear, and subsequent avoidance behaviour.

This suggests that the perceived threat of being bullied may manifest in other types of behavioural disturbances associated with other types of anxiety. For example, Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders fifth edition (DSM-5) criteria for separation anxiety requires an environmental risk factor being the experience of a stressful or traumatic event (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). When bullied at school, the school environment may elicit fear in bullying victims that manifests as behaviour consistent with separation anxiety symptomology. For example, distress when separated from major attachment figures, in the school environment, not wanting to attend school camps, or worrying about losing major attachment figures. Indeed, school refusal is well known to be associated with bullying victimisation (Hutzell & Payne, Citation2012) and may reflect the victim avoiding the perpetrator and likelihood of further bullying.

Relatedly, DSM-5 criteria states that panic attacks are associated with concerns of being embarrassed and receiving negative social judgement due to panic symptoms being noticed by others (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Behavioural disturbances involve avoidance of agoraphobia-type situations such as large crowds or places where the individual feels trapped, by not wanting to leave home (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Considering school attendance is required by law (Victorian State Government, Citation2022), the school environment may be perceived in this way by bullied adolescents and may also result in panic disorder-related school absenteeism. Although the DSM-5 categorises obsessive-compulsive disorder under obsessive-compulsive and related disorders, the close relationship with anxiety disorders is recognised (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Stressful or traumatic events are deemed environmental risk factors for the development of obsessive-compulsive disorder, once again indicating a possible link with bully victimisation experiences.

The cognitive model

Applying a cognitive model to bullying victims’ experiences provides an empirical theoretical basis on which to understand the hypothesised connection between bullying and anxiety disorders beyond that of social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder. Well known in the field of psychology, the cognitive model explains the influence of cognitions on emotional, behavioural, and physiological responses (Beck, Citation1976). In the case of anxiety disorders, the driving cognitions of perceived threat result in fear, anxiety, and behavioural disturbances, typically avoidance behaviour (Beck et al., Citation1987). Research to-date has focussed on the perceived threat of being bullied and fear of social situations as in social anxiety disorder and fear of various events or activities such as school performance as in generalised anxiety disorder (Moore et al., Citation2017). However, according to the DSM-5, fear, anxiety, and behavioural disturbances are shared features of all anxiety disorders (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013).

Indeed, being bullied is a chronic, traumatic experience (Idsoe et al., Citation2012), and given the underlying fear associated with the anxiety disorders, extending past research to include separation anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder symptomology is warranted. Moreover, research has also neglected to investigate whether the associations between bullying victimisation and specific anxiety disorder symptomology differ between adolescents being bullied in different ways. Understanding these relationships is crucial to the development of empirical-based psychological treatment and school-based interventions.

Covert versus overt bullying

Over four decades of research have focussed on the traditional conceptualisation of bullying defined as overt, physical behaviour such as hitting, kicking, or overt teasing and name-calling (Moore et al., Citation2017; Olweus, Citation1978, Citation1996). However, two covert types have been subsequently identified: reputational and relational (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Citation2004; Siegel et al., Citation2009). Covert bullying can occur in person or through information and communication technology (Barnes et al., Citation2105). Reputational bullying refers to attempts to damage a peer’s reputation through rumour spreading within the wider peer group. Relational bullying occurs within the victim’s close friendship group and involves using one’s own relationship to harm the victim by manipulating friendships (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Citation2004). The bully may encourage others to dislike the victim, threaten to end friendships, damage the victim’s reputation, and socially exclude the victim (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Citation2004; Siegel et al., Citation2009). Although victims are aware of the perpetrator of covert bullying, this behaviour remains hidden from adults (Cross et al., Citation2009).

There is growing awareness among researchers that covert bullying is associated with more severe mental health outcomes than overt bullying (Hawker & Boulton, Citation2000). For example, Ferraz de Camargo and Rice (Citation2020) investigated the relationships between the three types of bullying and depressive symptomology among Australian high-school students aged from 12 to 18 years. Results demonstrated that relational bullying accounted for the most unique variance in levels of depression followed by reputational bullying. Of note is that overt bullying did not uniquely predict a significant amount of variance (Ferraz de Camargo & Rice, Citation2020). This supports previous research that found relational victimisation was associated with higher levels of depressive symptomology than physical bullying (Baldry, Citation2004). Similar results have been shown with social anxiety outcomes. For example, overt, reputational, and relational bullying together were found to account for a significant portion of the variance in social anxiety disorder symptomology among 14–19 year old victims, additionally, relational bullying was also uniquely and strongly associated (Siegel et al., Citation2009).

Despite the growing evidence that mental health outcomes differ according to the type of bullying, research typically continues to investigate bullying as a single construct and defines bullying as the traditional overt form (for example, see Jadambaa et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2017). This is concerning as the results of this research may drive anti-bullying programs and interventions to focus on traditional overt bullying rather than on the more harmful covert bullying. As a result, victims of covert bullying may be deprived of vital support.

Rationale

The harmful impact of bullying victimisation on adolescents’ experiences of social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder is well documented. However, the extent to which the effects of bullying victimisation extend to other anxiety subtypes is unclear. Further, the role of overt and covert bullying types in these relationships has not been explored. This lack of empirical knowledge is a barrier to the development of targeted anti-bullying programs and individual psychological treatment and intervention for bullying victims. The current study will address two important gaps in the literature: 1. Explore the relationship between bullying victimisation and anxiety disorder symptomology beyond that of generalised anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder to include symptomology associated with separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, and 2. Explore overt and two covert types of bullying (reputational and relational) within these relationships.

Aims and hypotheses

Study 1

The aim of Study 1 was to assess the relationship between bullying victimisation and symptomology associated with generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder symptomology. A narrative synthesis is provided.

Study 2

Study 2 aims to build on and fill gaps in the literature identified in Study 1 by examining the relationship between specific types of bullying victimisation (overt, reputational, and relational) and symptomology associated with the specific anxiety disorders generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder, among Australian high-school students aged 12–18 years.

It is hypothesised that overt, reputational, and relational bullying victimisation will uniquely predict levels of specific anxiety disorder symptomology. It is also hypothesised that relational and reputational bullying victimisation will predict higher levels of anxiety symptomology compared with overt bullying victimisation.

Study 1: method

Study design

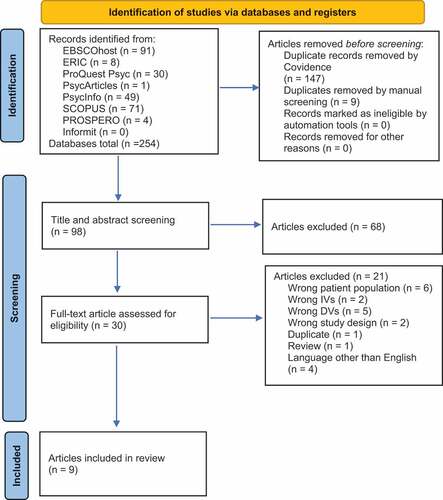

This paper consists of a selective review of the literature published between 2011 and 2021. The authors followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., Citation2009).

Search strategy

Multiple sources were used to identify potentially eligible studies including EBSCOHost, ProQuest ERIC, ProQuest Psych, PsychArticles, PsycInfo, and SCOPUS. The following keywords were used in varying combinations to conduct an ABTI search: peer victimisation, bullying, adolescents, teenagers, high school, secondary school, generalised anxiety, social anxiety, separation anxiety, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Second reference sections of the retrieved studies were examined to identify other potentially eligible studies.

Selection criteria, data extraction, and data management

This systematic review included studies meeting the following inclusion criteria: (1) reported original, quantitative, empirical research published in a peer reviewed journal; (2) examined the relationship between experiences of bullying victimisation and the specified anxiety disorders; (3) participants aged from 12 to 18 years, (4) publication dated from 2011 to 19 September 2021. Results were expanded by accepting articles that explored any type of bullying, for example, bullying measured as a single construct, physical, cyberbullying, overt, covert, relational, or reputational. Additionally, this study targeted anxiety subtypes as specified by DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013) and as such did not examine internalising symptomology. Finally, studies published in a language other than English were excluded. The PRISMA flow chart is presented in .

Critical appraisal

The final sample of the systematic review included nine quantitative studies that met the inclusion criteria; four were short-term longitudinal and five were cross-sectional. Study designs were rated using the Newcastle Ottawa scale (NOS; Wells et al., Citation2013) for cross-sectional studies. The scale is a globally recognised and well-validated critical appraisal tool (Luchini et al., Citation2017). The NOS uses a “star system” which supports objective rating of studies on three perspectives; selection of study groups, comparability of the groups, and the ascertainment of outcome of interest for cohort and cross-sectional studies. According to this system, the five cross-sectional studies were rated as medium quality and of the five cohort studies, four were rated as high quality and one as medium quality.

Results

The principal author and research assistant assessed each included study for risk of bias, and extracted data about the independent and dependent variables, and relevant outcomes. As presented in , key study aspects were extracted including author, date, country, participants, study type, independent and dependent variables, outcomes, and quality based on the critical appraisal tools. In line with the Cochrane rapid review recommendations, a narrative synthesis of results was conducted (Garrity et al., Citation2021).

Table 1. Characteristics of Included Studies.

The emerging theme among studies was that outcomes were typically limited to social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder with all nine studies exploring the former and only one exploring the latter. Investigation beyond social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder was limited to one study which included separation and panic symptomology.

Several types of bullying victimisation were considered as independent variables across the studies, including traditional bullying, overt, online/cyberbullying, verbal, relational, physical and belonging snatch. However, the theme among studies was that overt and covert types of bullying were not clearly defined or explored. Mediating variables included neuroticism, extraversion, peer support, continent self-worth, shame, and self-esteem.

Unexpectedly, two studies demonstrated a lack of association between bullying and social and generalised anxiety disorders. This may be explained by the Depression and Anxiety scale (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) which has not been validated for younger participants. For example, Pabian and Vandebosch’s (Citation2016) study included participants aged 10–17 years, while the scale is recommended for ages 14 years and older only. Similar concerns surround the second study by Chu et al. (Citation2019) which used the Chinese version of the Revised Cyberbullying Inventory (Chu et al., Citation2019; Topcu & Erdur-Baker, Citation2010) which has been validated for children aged 13–21 years, while participants were aged 11–15 years. As such, face validity of these questionnaires may have been reduced, thus impacting the quality of these studies and interpretation of results.

Considering the nine studies identified through the systematic review, there was no homogeneity among the study variables and outcomes. Further, differences in methodology among the studies prevented a quantitative synthesis. Therefore, a narrative synthesis is required (Campbell et al., Citation2020).

Study 2: method

Participants

Australian high-school students (N = 349, 49.4% females) who had experienced bullying victimisation during the past 8 months were recruited to take part in an online survey. Participants’ age ranged from 12 to 18 years (M = 14.25, SD = 1.51). Consent was obtained from parents and students.

Measures

Total and scale scores for the measures were created by obtaining the summed total for each measure.

Bullying victimisation

The Revised Peer Experiences Questionnaire (RPEQ; De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Citation2004; Prinstein et al., Citation2001) was used to assess overt, relational, and reputational bullying victimisation. Each subscale consists of three items representing each type of bullying. The frequency of each victimisation experience is rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = never, 5 = a few times a week). Higher scores reflect higher levels of bullying victimisation.

In line with Prinstein et al. (Citation2001), questions were introduced with:

For the next question, please think about things that might have happened to you at school, or out of school since the beginning of this school year. Include texts, Facebook etc. as well as face-to-face contact. Do not include things that happened with your close family members (such as brothers and sisters).

Internal consistency estimates (Cronbach’s alpha) for the subscales have been reported to be relational = .84, reputational = .83, and overt = .78 (De Los Reyes & Prinstein, Citation2004). In this study, the internal consistency estimates were overt victimisation = .76, reputational = .88, and relational = .80. Additionally, in this study, McDonald’s Omega was overt victimisation = .778, reputational = .845, and relational = .886.

Anxiety disorder symptomology

The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale (RCADS; Chorpita et al., Citation2015) is a 47-item, youth self-report questionnaire based on DSM-IV criteria with subscales including generalised anxiety disorder, social phobia, panic disorder, separation anxiety disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. Subscales consist of 6–9 items. Items are rated on a 4-point Likert-scale from 0 (“never”) to 3 (“always”).

Previous studies have reported good internal consistency of the RCADS (Chorpita et al., Citation2000, Citation2005; Piqueras et al., Citation2017). The RCADS has been validated in an Australian community sample (N = 405) of children and adolescents aged 8–18 years (De Ross et al., Citation2002) and in general and clinical populations of children and adolescents (Chorpita et al., Citation2000, Citation2005; De Ross et al., Citation2002). The results of the analysis of alpha coefficients showed excellent reliability for the five RCADS anxiety disorder subscales, with the mean alpha values ranging from good to excellent (range = .81 to .91). Further, McDonald’s Omega demonstrated excellent reliability with values ranging from .818 to .914.

Scale descriptives are presented in .

Table 2. Means, Standard Deviations (SD), Theoretical Ranges, Observed Ranges, and Cronbach’s α among the Main Study Variables (N = 338).

Procedure

A web-based survey was created using Qualtrics survey software. Parental consent was obtained through the distribution of an online ethical statement on the parent portal of the three high schools in Melbourne. Students who had parental consent were then invited to gather at the school hall where they were provided with a link to access the ethical statement and survey. Students were informed that participation was anonymous and voluntary and counselling was offered. Students’ participation was overseen by a school staff member and submission indicated consent. Research ethics approval from the authors’ Universities was obtained prior to data collection (approval number HE18–128) and from the Department of Education and Training (approval number 1028_003795).

For ethical considerations, participants that may be experiencing mental health issues were screened out by the following two screening questions: “Do you see a psychologist or doctor for help with your emotions?” and “Is it likely that answering questions about being a victim of bullying will be highly upsetting for you?”. A positive response to either question redirected the participant to the end of the survey. Participants provided demographic information including gender, age, and year level. Contact details for Kids Helpline, Child and Youth Mental Health Service (CYMHS), and the School Counsellor were supplied in the case that participants felt upset about the survey.

Statistical analysis

A power analysis using an alpha of .05, a power level of .95, a medium effect size (f2 = .15), and 3 predictors suggests 74 participants for this study. Subsequently, data from a sample of 526 participants was collected. Cases that did not progress to the survey include; 134 cases (25.5%) due to giving positive responses to the screening questions, 25 cases (4.7%) due to not agreeing for the study to be published and 12 cases (2.3%) due to not agreeing to participate in the study. A further 17 cases (3.2%) were deleted due to discontinuation. Overall, usable data was obtained from 338 participants (64.26%). The majority (25.5%) of cases were excluded due to giving a positive response to having seen a psychologist for mental health concerns thus removing those experiencing mental health issues at the clinical level. This measure was intended to protect the mental health of the young participants and to target a general population sample. No missing values were detected. Bivariate correlations were used to investigate intercorrelations among study variables. Examination of the hypothesised relationships were conducted through linear multiple regression analysis. These analyses were performed using IBM SPSS 25 (IBM Corp, Citation2017).

Analysis was performed using IBM SPSS REGRESSION and EXPLORE for evaluation of assumptions which confirmed no violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, multicollinearity and homoscedasticity. Several outliers were detected; however, this violation of the normal distribution only had a small effect on the analysis. Moreover, due to the large sample size, these cases were retained (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). Skewness and kurtosis were detected on all anxiety subscales; however, inspection of the histograms indicated normal distribution for the generalised anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder scales. Inverse transformation was conducted on the separation anxiety disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder scales. However, this violation was found to have only a small effect on the analysis and raw data was used in the final analyses (Tabachnick & Fidell, Citation2013). Effect sizes were calculated as Cohen’s f 2 with small, medium, and large effect sizes considered to be 0.02, 0.15, and 0.35, respectively (Cohen, Citation1988).

Results

To investigate the relationships between overt, reputational, and relational bullying victimisation with generalised anxiety, social anxiety, separation anxiety, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and panic disorder, five multiple-regression analyses were completed. Prior to running the main analyses, correlations between variables were completed. Due to violations of normality, Spearman correlations were conducted and results demonstrated that all of the correlations were significant and in the expected direction (see ).

Table 3. Spearman Correlations Between Types of Anxiety and Predictor Variables.

Multiple regression results

Multiple regression was used to assess the ability of overt, reputational, and relational bullying victimisation to predict levels of symptomology associated with generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder and overall anxiety scores.

Generalised anxiety disorder

The regression model was statistically significant F(3, 334) = 23.152, p < .001, R2 = .17. Overt, reputational, and relational bullying-victimisation together predicted 17.2% (16.5% adjusted) of the variance in levels of generalised anxiety disorder with a medium-to-large effect size. The best predictor of levels of generalised anxiety was relational bullying-victimisation accounting for 3.6% of the variance followed by reputational bullying-victimisation which accounted for 1.8% of the variance. However, overt bullying-victimisation does not uniquely predict a significant amount of variance (see ).

Table 4. Regression Analysis Summary Different Bullying Types Predicting Generalised Anxiety Disorder.

Social anxiety

The regression model was statistically significant F (3, 334) = 23.380, p < .001, R2 = .17. Overt, reputational, and relational bullying-victimisation together predicted 17.4% (16.6% adjusted) of the variance in levels of social anxiety with a medium-to-large effect. The best predictor of levels of social anxiety was relational bullying-victimisation accounting for 6.2% of the variance followed by reputational bullying-victimisation which accounted for 1.9% of the variance. However, overt bullying-victimisation does not uniquely predict a significant amount of variance (see ).

Table 5. Regression Analysis Summary Predicting Social Anxiety.

Separation anxiety disorder

The regression model was statistically significant F (3, 334) = 21.947, p < .001, R2 = .17. Overt, reputational, and relational bullying-victimisation together predicted 17% (15.7% adjusted) of the variance in levels of separation anxiety with a medium effect size. The best predictor of levels of separation anxiety was relational bullying-victimisation accounting for 5.2% of the variance followed by reputational bullying-victimisation which accounted for 1.4% of the variance. However, overt bullying-victimisation does not uniquely predict a significant amount of variance (see ).

Table 6. Regression Analysis Summary Predicting Separation Anxiety.

Panic disorder

The regression model was statistically significant F (3, 334) = 27.099, p < .001, R2 = .2. Overt, reputational, and relational bullying-victimisation together predicted 19.6% (18.9% adjusted) of the variance in levels of panic disorder with a medium-to-large effect. The best predictor of levels of panic disorder was relational bullying-victimisation accounting for 4.2% of the variance followed by reputational bullying-victimisation which accounted for 3.5% of the variance. However, overt bullying-victimisation does not uniquely predict a significant amount of variance (see ).

Table 7. Regression Analysis Summary Predicting Panic Disorder.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder

The regression model was statistically significant F (3, 334) = 23.523, p < .001, R2 = .17. Overt, reputational, and relational bullying-victimisation together predicted 17% (16.7% adjusted) of the variance in levels of obsessive-compulsive disorder with a medium-to-large effect size. The best predictor of levels of obsessive-compulsive disorder was reputational bullying-victimisation accounting for 3.2% of the variance followed by relational bullying-victimisation which accounted for 2.8% of the variance. However, overt bullying-victimisation does not uniquely predict a significant amount of variance (see ).

Table 8. Regression Analysis Summary Predicting Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder.

Discussion

Study 1 identified the gap in the literature. Study 2 explored the relationships between overt, reputational, and relational bullying victimisation and subtypes of anxiety. It was hypothesised that overt, reputational, and relational bullying victimisation would uniquely predict levels of generalised anxiety disorder, social anxiety disorder, separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder. It was also hypothesised that covert types of bullying victimisation, being relational and reputational types, would predict higher levels of anxiety symptomology compared with overt bullying victimisation in these relationships.

Study 1

The results of the systematic review support the well-evidenced relationship between bullying victimisation and social/generalised anxiety disorder (Jadambaa et al., Citation2020; Moore et al., Citation2017). Although two of the papers failed to demonstrate this association, this may be due to the types of bullying explored: traditional and cyberbullying. For example, traditional bullying has been shown to be less impactful in comparison to covert bullying on experiences of social anxiety (Ferraz de Camargo & Rice, Citation2020; La Greca & Harrison, Citation2005), and the anonymity of cyberbullying may be protective of anxiety outcomes (Slonje & Smith, Citation2013). In recognition of the more harmful effects of covert bullying, calls have been made for research to explore types of bullying rather than consider bullying as a single construct (Ferraz de Camargo & Rice, Citation2020). However, of the nine studies, eight did not measure covert bullying, thus losing this important detail.

As expected, research investigating bullying victimisation with anxiety disorders beyond that of social and generalised anxiety is rare. Only one cross-sectional study explored four dimensions of anxiety symptomology; social anxiety disorder, physical symptoms, harm avoidance, and separation/panic (Yen et al., Citation2013). Of these dimensions, social anxiety disorder, panic disorder and separation anxiety disorder were defined in line with DSM-5 criteria (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). This study was also the only one to consider types of bullying victimisation beyond that of traditional bullying and cyberbullying; verbal, relational, physical bullying, and “belongings snatch” (Yen et al., Citation2013). However, the overt and covert nature of the types of bullying was not clearly defined and differences between the two were not investigated. Despite these limitations, the study offered some insight that victims of verbal, relational, physical bullying, and belongings snatch experienced higher levels of social anxiety and separation/panic symptomology in comparison to non-victims (Yen et al., Citation2013).

While the body of research on bullying is large, the number of studies that met eligibility criteria was relatively small. This may reflect the diversity of bullying victimisation research including a focus on investigating perpetration rather than victimisation, alternative outcomes, and preventative measures, mainly, reducing bullying behaviour. This systematic review confirms that bullying research continues to be limited to two types of anxiety outcomes: social anxiety and, less often, generalised anxiety disorder. Further, bullying research continues to neglect to define and investigate covert types of bullying which are known to be more detrimental and to have longer-lasting effects on mental health (Cross et al., Citation2009; Ferraz de Camargo & Rice, Citation2020).

Study 2

Drawing on the cognitive model as developed by Beck (Citation1976), Study 2 found that the first hypothesis was partially supported with results demonstrating unique, significant, positive relationships between reputational and relational bullying victimisation and each specific anxiety disorder. However, results demonstrated that overt bullying did not significantly predict levels of subtypes of anxiety symptomology. This is consistent with past research by the authors that found covert bullying to be related to depressive outcomes among adolescents, while overt bullying was not found to be significantly related (Ferraz de Camargo & Rice, Citation2020). It is plausible that the increased support, empathy, and intervention for victims of overt bullying due to this behaviour being more easily detected (Bauman & Del Rio, Citation2006) may reduce victims’ experience of anxiety overall. Indeed, victims are more likely to report overt bullying and seek help as they believe they can rely on teachers to intervene and support them (Hazler et al., Citation2001).

Interestingly, considering the two covert types of bullying, relational bullying tended to be a better predictor of each anxiety subtype than reputational bullying, except for OCD, which demonstrated that both were of equal strength. These results are in line with past research that found relational bullying to be more strongly related to social anxiety disorder and depressive symptomology than reputational (Ferraz de Camargo & Rice, Citation2020; Siegel et al., Citation2009). Due to relational bullying occurring within the victim’s inner circle of friends, this type of bullying may be more psychologically scarring than relational bullying, which is more removed and occurs in the wider peer group.

It should be noted that participants were screened out of this study if they reported seeing a mental health practitioner, thus resulting in a general population sample. Inclusion of these participants may have strengthened results. That these results were demonstrated with a general population sample is significant.

Bullying as a perceived threat

The results of the combined studies highlight that conceptualising bullying victimisation as a social issue has resulted in a narrow body of literature limited to researching generalised anxiety disorder and social anxiety disorder as the expected mental health outcomes. This means that vulnerable adolescents experiencing separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder as a result of bullying victimisation may be deprived of much needed psychological treatment and support. Shifting the conceptualisation of bullying victimisation to chronic trauma provides rationale based on the cognitive model framework (Beck, Citation1976). That is, the perceived threat in bullying situations results in fear and anxiety which drives avoidance behaviour that is in line with a range of anxiety subtypes as defined by DSM-5 criteria (APA, 2103).

Consistent with the cognitive model, avoidance behaviour is a key maintaining factor of anxiety due to the individual missing out on gaining new evidence for their distorted thoughts, in this case the over estimation of threat (Beck, Citation1976). Avoidance behaviour may present as not wanting to attend school camps, not wanting to be separated from major attachment figures or the home, avoidance of large crowds of students, and school absenteeism; all common behaviours of bullying victims (Wolke & Lereya, Citation2015). Exploring bullying victimisation as underlying reasons means that the victim can receive appropriate support to combat avoidance behaviour, thus breaking the anxiety cycle and reducing anxiety outcomes. For example, supporting the victim to face their fear by attending camp or school may allow them to learn that they can manage the bullying situation thus reducing their experience of anxiety.

Anxiety subtypes and DSM criteria

Understanding these fear and avoidance responses in the context of DSM diagnostic criteria would increase clinician’s awareness of the types of anxiety disorders bullying victims might experience and would facilitate diagnosis and treatment. For example, through use of the RCADS, a psychometrically valid scale based on DSM criteria, study 2 demonstrated that bullying victimisation is associated with specific DSM defined anxiety disorders (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). Based on this information, clinicians working with bullying victims are guided to assess for the identified DSM anxiety subtypes and provide appropriate evidence-based treatment.

For example, Study 1 identified a cross-sectional study involving 5537 Taiwanese adolescents that explored the relationships between bullying (verbal, relational, physical, and “belongings snatch”) and four different anxiety subtypes; physical symptoms, harm avoidance, social anxiety disorder, and separation/panic as measured by the Taiwanese version of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC; Yen et al., Citation2010). It was found that verbal and relational bullying were associated with higher levels of physical symptoms, social anxiety disorder, and separation/panic symptomology. Additionally, victims of physical bullying and belongings snatch reported more severe anxiety symptoms on all four dimensions than did non-victims (Yen et al., Citation2013). However, van Gastel and Ferdinand (Citation2008), have suggested that the self-reported MASC may not be a psychometrically valid screening tool for DSM-related anxiety symptomology. Indeed, the MASC harm avoidance scale was not found to predict any DSM-IV diagnosis, while the social anxiety scale moderately predicted social phobia and the separation anxiety scale moderately predicted panic disorder (van Gastel & Ferdinand, Citation2008). In order to provide bullying victims evidence-based, targeted psychological treatment, accurate diagnosis is essential. As such, utilisation of a psychometrically valid scale based on DSM criteria, such as the RCADS (Chorpita et al., Citation2015), is valuable.

Overt and covert bullying victimisation

The studies included in the systematic review also highlight that covert bullying is often not clearly defined or investigated. Given that Study 2 found that covert bullying, not overt, negatively impacts adolescents’ mental health across five types of anxiety, it is essential for practitioners and researchers to also investigate covert bullying. Several reasons have been suggested for this difference. Covert bullying is hidden from adults and victims report lacking confidence they will be believed and supported (Hazler et al., Citation2001). Indeed, teachers report feeling less confident addressing covert bullying, less empathy for the victims, and they believe this type to be less serious and are less likely to intervene and more likely to dismiss victims’ concerns (Bauman & Del Rio, Citation2006; Yoon & Kerber, Citation2003). Moreover, schools often have anti-bullying policies that address overt bullying but not covert bullying (Archer & Coyne, Citation2005).

As demonstrated in Study 2, considering subtypes of covert bullying provides a detailed understanding of this hidden behaviour. For example, relational bullying was found to be a stronger predictor than reputational bullying for all anxiety subtypes except OCD. It has been suggested that these results reflect the distress of being excluded or rejected within the close friendship group at a developmental phase when adolescents increasingly rely on friendships (Siegel et al., Citation2009). This offers new and important insight for the development of anti-bullying programs and suggests that targeting bullying within close friendship groups may be beneficial.

Practical implications

The results of this study offer important practical considerations for practitioners, school educators, and caregivers. This study raises awareness of the far-reaching effects of being bullied and the impact on victims’ experience of anxiety. In the clinical setting, screening adolescents presenting with anxiety-related mental health concerns for bullying victimisation is essential. Adolescents may not offer information regarding being bullied, particularly in the case of covert types, due to not expecting to be supported or due to expecting to be dismissed. It is the responsibility of practitioners to explore this with vulnerable clients as identifying experiences of bullying offers the opportunity to implement appropriate treatment and support. It is hoped that this study will also raise awareness among school educators and care givers that behaviours including school absenteeism, obsessive behaviours, or panic may be related to bullying. It is hoped that this new understanding will increase much needed empathy, support, and intervention for victims, thus alleviating suffering.

Limitations

This study offers important new insight into the effects of types of bullying victimisation on adolescents’ experience of types of anxiety symptomology; however, limitations should be considered. The detection of bullying victimisation and anxiety symptomology was made on the basis of self-reported evaluations and may have caused some bias, thus social desirability should be considered when interpreting results. Further, the cross-sectional nature of this study does not allow for conclusions about directions of influence or existence of causal effects. Future research should consider longitudinal study designs to offer clarification.

Conclusion

Results of this study demonstrate that covert bullying victimisation is associated with higher anxiety symptoms than traditional overt bullying. It is time that research shifts from defining bullying as a single construct or focusing solely on overt bullying victimisation. Instead, increased investigation of clearly defined and assessed covert types of bullying is needed. It is also time for bullying victimisation research to extend mental health outcomes to include a range of anxiety subtypes and to consider the common factor of perceived fear that underlies these disorders. Indeed, the results of this study identify the need to apply a multi-dimensional scale to evaluate anxiety subtypes in adolescent bullying victims when developing preventative and intervention programs. These findings suggest that other anxiety symptoms such as separation anxiety disorder, panic disorder, and obsessive-compulsive disorder may be related to bullying victimisation and highlights the lack of research in this area. Therefore, it is important that practitioners screen for all symptoms, not only social or generalised anxiety disorder symptomology when assessing bullying victims. Finally, practitioners being alert to the associations between types of bullying victimisation and anxiety disorder symptomology may expediate the identification of bullied adolescents through assessing and screening adolescents for bullying experiences. It is hoped that this research encourages much needed psychological treatment and support for bullying victims.

Acknowledgements

The first author gratefully acknowledges the Victorian Department of Education and Training and the Melbourne High Schools where the data https://www.cloud.une.edu.au were collected. In particular, thanks are extended to the Principals and Assistant Principals for their approval and endorsement of the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). The diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Author.

- Archer, J., & Coyne, S. M. (2005). An integrated review of indirect, relational, and social aggression. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 9, 212–17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327957pspr0903_2

- The Australian Government. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents. Part 2: Prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. The Department of Health. http://www.health.gov.au/internet/main/publishing.nsf/content/mental-pubs-m-child2

- Australian Insitute of Health and Welfare. (2021). Australia’s youth: Mental illness. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/children-youth/mental-illness

- Baldry, A. C. (2004). The impact of direct and indirect bullying on the mental and physical health of Italian youngsters. Aggressive Behaviour, 30(5), 343–355. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20043

- Barnes, A., Cross, D., Lester, L., Heam, L., Epstein, M., & Monks, H. (2105). The invisibility of covert bullying among students: Challenges for school intervention. Australian Journal of Guidance and Counselling, 22, 206–226. https://doi.org/10.1017/jgc.2012.27

- Bauman, S., & Del Rio, A. (2006). Preservice teachers’ responses to bullying scenarios: Comparing physical, verbal, and relational bullying. Journal of Educational Psychology, 98, 219–231. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.98.1.219

- Beck, A. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. International Universities Press.

- Beck, A., Brown, G., Steer, R. A., Eidelson, J. I., & Riskind, J. H. (1987). Differentiating anxiety and depression: A test of the cognitive content-specificity hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 96(3), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.96.3.179

- Calvete, E., Orue, I., & Gámez-Guadix, M. (2016). Cyberbullying victimization and depression in adolescents: The mediating role of body image and cognitive schemas in a one-year prospective study. European Journal of Criminal Policy and Research, 22(2), 271–284. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-015-9292-8

- Campbell, M., McKenzie, J., Sowden, A., Vittal Katikireddi, S., Brennan, S. E., Ellis, S., Hartmann-Boyce, J., Ryan, R., Shepperd, S., Thomas, J., Welch, V., & Thomson, H. (2020). Synthesis without meta-analysis (SWiM) in systematic reviews: Reporting guideline. BMJ, 368, 16890. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l6890

- Cañas, E., Estevez, E., Martínez-Monteagudo, M., & Delgado, B. (2020). Emotional adjustment in victims and perpetrators of cyberbullying and traditional bullying. Social Psychology of Education, 23(4), 917–942. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-020-09565-z

- Chorpita, B. F., Ebesutani, C., & Spence, S. H. (2015). Revised Children’s Anxiety and Depression Scale: User’s guide. www.childfirst.ecla.edu

- Chorpita, B. F., Moffitt, C., & Gray, J. (2005). Psychometric properties of the Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale in a clinical sample. Behavioural Research and Therapy, 43, 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2004.02.004

- Chorpita, B. F., Yim, L., Moffitt, C. E., Unemoto, I. A., & Francis, S. E. (2000). Assessment of symptoms of DSM-IV anxiety and depression in children: A Revised Child Anxiety and Depression scale. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 38(8), 835–855. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0005-7967(99)00130-8

- Chu, X. W., Fan, C. Y., Lian, S. L., & Zhou, Z. K. (2019). Does bullying victimization really influence adolescents’ psychosocial problems? A three-wave longitudinal study in China. Journal of Affective Disorders, 246, 603–610. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2018.12.103

- Çoban, Ö. G., Bedel, A., Önder, A., Adanır, A. S., Tuhan, H., & Parlak, M. (2021). Psychiatric disorders, peer-victimization, and quality of life in girls with central precocious puberty. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 143, 110401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2021.110401

- Cohen, J. W. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Coyle, S., Malecki, C., & Emmons, J. (2019). Keep your friends close: exploring the associations of bullying, peer social support, and social anxiety. Contemporary School Psychology, 25(2), 230–242. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-019-00250-3

- Cross, D., Shaw, R., Hearn, L., Epstein, M., Monks, H., Lester, L., & Thomas, L. (2009). Australian covert bullying prevalence study. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/ecuworks/6795/

- De Los Reyes, A., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). Applying depression-distortion hypotheses to the assessment of peer victimization in adolescents. Journal of Clinical and Adolescent Psychology, 33, 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3302_14

- The Department of Health. (2005). What is panic disorder and agoraphobia? The Australian Government. Retrieved November, 2021, from https://www1.health.gov.au/internet/publications/publishing.nsf/Content/mental-pubs-p-panic-toc mental-pubs-p-panic-wha

- De Ross, R. I., Gullone, E., & Chorpita, B. F. (2002). The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale: A psychometric investigation with Australian youth. Behaviour Change, 19(2), 90–101. https://doi.org/10.1375/bech.19.2.90

- Fahy, A. E., Stansfeld, S. A., Smuk, M., Smith, N. R., Cummins, S., & Clark, C. (2016). Longitudinal associations between cyberbullying involvement and adolescent mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 59(5), 502–509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2016.06.006

- Ferraz de Camargo, L., & Rice, K. (2020). Positive reappraisal moderates depressive symptomology among adolescent bullying victims. Australian Journal of Psychology, 72, 368–379. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12288

- Ford, R., King, T., Priest, N., & Kavanagh, A. (2017). Bullying and mental health and suicidal behaviour among 14- to 15-year-olds in a representative sample of Australian children. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 51, 897–908. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867417700275

- Garrity, C., Gartlehner, G., Nussbaumer-Streit, B., King, V. J., Hamel, C., Kamel, C., Affengruber, L., & Stevens, A. (2021). Cochrane Rapid Reviews Methods Group offers evidence-informed guidance to conduct rapid reviews. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology, 130, 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2020.10.007

- Ghoul, A., Niwa, E. Y., & Boxer, P. (2013). The role of contingent self-worth in the relation between victimization and internalizing problems in adolescents. Journal of Adolescence, 36(3), 457–464. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.01.007

- Hawker, D. S. J., & Boulton, M. (2000). Twenty years’ research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 41(4), 441–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00629

- Hazler, R. J., Miller, D., Carney, J., & Green, S. (2001). Adult recognition of school bullying situations. Educational Research, 43(2), 133–146. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131880110051137

- Hutzell, K. L., & Payne, A. (2012). The impact of bullying victimisation on school avoidance. Youth violence and juvenile justice, 10, 370–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204012438926

- IBM Corp. (2017) . IBM Statistics for Windows Version 25. IBM Corp.

- Idsoe, T., Dyregrov, A., & Idsoe, E. (2012). Bullying and PTSD symptoms. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(6), 901–911. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-012-9620-0

- Jadambaa, A., Thomas, H. J., Scott, J. G., Graves, N., Brain, D., & Pacella, R. (2020). The contribution of bullying victimisation to the burden of anxiety and depressive disorders in Australia. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 29, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000489

- La Greca, A. M., & Harrison, H. M. (2005). Adolescent peer relations, friendships, and romantic relationships: Do they predict social anxiety and depression? Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 26, 83–94. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1022684520514

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). Manual for the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (2nd ed.). Psychological Foundation.

- Luchini, C., Stubbs, B., Solmi, M., & Veronese, N. (2017). Assessing the quality of studies in meta-analyses: Advantages and limitations of the Newcastle Ottawa Scale. Journal of Meta-Analysis, 5, 80–84. https://doi.org/10.13105/wjma.v5.i4.80

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Annals of Internal Medicine, 151, 264–269. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

- Moore, S. E., Norman, R. E., Suetani, S., Thomas, H. J., Sly, P. D., & Scott, J. G. (2017). Consequences of bullying victimization in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Journal of Psychiatry, 7, 60–76. https://doi.org/10.5498/wjp.v7.i1.60

- Olweus, D. (1978). Aggression in the schools: Bullies and whipping boys. Hemisphere Publishing.

- Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying in school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell Publishers.

- Olweus, D. A. (1996). The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire.

- Pabian, S., & Vandebosch, H. (2016). Short-term longitudinal relationships between adolescents’ (cyber)bullying perpetration and bonding to school and teachers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 40(2), 162–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025415573639

- Piqueras, J. A., Martin-Vivar, M., Sandin, B., San Luis, C., & Pineda, D. (2017). The Revised Child Anxiety and Depression Scale: A systematic review and reliability generalization meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 218, 153–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.04.022

- Prinstein, M. J., Boergers, J., & Vernberg, E. M. (2001). Overt and relational aggression in adolescents: Social-psychological adjustment of aggressors and victims. Journal of Clinical Child Psychology, 30(4), 479–491. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15374424JCCP3004_05

- Putallez, M., Grimes, C. L., Foster, K. J., Kupersmidt, J. B., Coie, J. D., & Dearing, K. (2007). Overt and relationship aggression and victimisation: Multiple perspectives within the school setting. Journal of School Psychology, 45, 523–547. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2007.05.003

- Siegel, R. S., La Greca, A. M., & Harrison, H. M. (2009). Peer victimisation and social anxiety in adolescents: Prospective and reciprocal relationships. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 38, 1096–1109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-009-9392-1

- Slonje, R., & Smith, P. K. (2013). The nature of cyberbullying, and strategies for prevention. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 26–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.024

- Stanaway J. D., Afshin A., Gakidou E., Lim S. S., Abate D., Abate K. H., Abbafati C., Abbasi N., Abbastabar H., Abd-Allah F., & Abdela J. (2018). Global, regional, and national comparative risk assessment of 84 behavioural, environmental and occupational, and metabolic risks or clusters of risks for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet, 392, 1923–1994. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32225-6

- Swearer, S., & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the psychology of bullying: Moving toward a social-ecological diathesis-stress model. The American Psychologist, 70, 344–353. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038929

- Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6th ed.). Pearson Education Limited.

- Thomas, H. J., Chan, G. C., Scott, J. G., Connor, J. P., Kelly, A. B., & Willians, J. (2016). Association of different forms of bullying victimisation with adolescents’ psychological distress and reduced emotional wellbeing. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 50, 371–379. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867415600076

- Topcu, C., & Erdur-Baker, O. (2010). The revised cyber bullying inventory (RCBI): Validity and reliability studies. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences, 5, 660–664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2010.07.161

- van Gastel, W., & Ferdinand, R. F. (2008). Screening capacity of the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for Children (MASC) for DSM-IV anxiety disorders. Journal of Depression and Anxiety, 12, 1046–1052. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20452

- Victorian State Government. (2022). Attendance and missing school. Retrieved September 19, from https://www.vic.gov.au/attendance-and-missing-school

- Wells, G. A., Shea, B., O’Connell, D., Peterson, J., Welch, V., Losos, M., & Tugwell, P. (2013). The Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (NOS) for assessing the quality of nonrandomised studies in meta-analysis. http://www.ohri.ca/programs/clinical_epidemiology/oxford.asp

- Wolke, D., & Lereya, S. T. (2015). Long-term effects of bullying. Archives of Disease in Childhood, 100, 879–885. https://doi.org/10.1136/archdischild-2014-306667

- World Health Organisation. (2022). Adolescent Mental Health. Retrieved September 16, from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

- Wu, X., Qi, J., & Zhen, R. (2021). Bullying victimization and adolescents’ social anxiety: Roles of shame and self-esteem. Child Indicators Research, 14(2), 769–781. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09777-x

- Yen, C. F., Huang, M. F., Kim, Y. S., Wang, P. W., Tang, T. C., Yeh, Y. C., Lin, H. C., Liu, T. L., Wu, Y. Y., & Yang, P. (2013). Association between types of involvement in school bullying and different dimensions of anxiety symptoms and the moderating effects of age and gender in Taiwanese adolescents. Child Abuse & Neglect, 37(4), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2013.01.004

- Yen, C. F., Ko, C. H., Wu, Y. Y., Yen, J. Y., Hsu, F. C., & Yang, P. (2010). Normative data on anxiety symptoms on the Multidimensional Anxiety Scale for children in Taiwanese children and adolescents: Differences in sex, age, and residence and comparison with an American sample. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 41, 614–623. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-010-0191-4

- Yoon, J. S., & Kerber, K. (2003). Bullying: Elementary teachers’ attitudes and intervention strategies. Research in Education, 69, 27–35. https://doi.org/10.7227/RIE.69.3