Abstract

The present study extended previous research into the role of cognitive style in predicting depressive symptoms in children by examining positive attributional style for positive events in a prospective manner, with a focus on the influence of prior life experience. A non-clinical sample of 102 children (aged 10–12 years) was recruited. Participants completed self-report measures of depression, attributional style, stressful life events, and positive life events on two occasions (approximately 6 months apart). Positive attributional style for positive events moderated the relationship between negative life events and follow-up depressive symptoms. Number of positive events did not significantly moderate the negative life events–depression symptoms relationship although there was a trend in the expected direction. Positive attributional style for positive events appeared to act as both a mediator and moderator in the positive events–depression symptoms relationship. Theoretical and clinical implications of these findings are discussed.

It is estimated that 1–2% of children under the age of 12 years experience a clinical level of depression (Horowitz & Garber, Citation2006). Cognitive diathesis–stress theories propose a number of developmental pathways to the disorder, but these pathways are generally based on research using adult populations. Given that depression may present differently in children (Campbell, Citation1986), it is important to consider the complex interplay between biopsychosocial factors that may contribute to the development of depression in a child population. The present study examined relationships between positive attributional style, life events and depressive symptoms in children in a prospective fashion.

In terms of wellbeing, developmental psychopathology purports that a continuum exists with normal mood at one end and pathological manifestations of emotion at the other end (Muris, Citation2007). Muris (Citation2007) argues that children move along the continuum based on a multi-factorial model in which various vulnerability and protective factors interact overtime. As a result, when they experience stressful life events their levels of depression are determined by their current constellation of vulnerability and protective factors.

Vulnerability factors for depression in children include both negative life experiences and cognitive factors, such as attributional style, that is, the causal inferences that an individual makes following life events (Conley, Haines, Hilt, & Metalsky, Citation2001). According to cognitive diathesis–stress theory, those at risk of depression have a consistent style in which they make internal, stable, global attributions for negative events and external, unstable, specific attributions for positive events. As intimated above, however, neither negative life events nor attributional style alone is wholly predictive of mood change (Abramson, Metalsky, & Alloy, Citation1989). Rather, it is the interaction of cognitive styles (i.e., diathesis) and negative life events (i.e., stress) that predict future affective states (Needles & Abramson, Citation1990). Thus, the same stressful life event may happen to two different children but depending on their cognitive vulnerability one may be more susceptible to becoming depressed following aversive events and one may be more resilient.

Resilience is the phenomenon whereby individuals show positive adaptation despite significant life adversities (Schoon, Citation2006). Research on resilience in children has focused on a variety of variables that appear to moderate the impact of stress and transient symptoms on wellbeing (Muris, Citation2007; Tram & Cole, Citation2000). Protective factors can be truly protective (i.e., reduce a child's exposure to risk) or they can be compensatory (Rutter, Citation1985); they can be intrinsic to the child (i.e., attributional style) or part of the environment (Coie et al., Citation1993). Research suggests that the presence of more protective factors regardless of the number of vulnerability factors may lower the level of risk of psychological dysfunction (Resnick et al., Citation1997).

To date, there is a paucity of research on the role of positive experience as an independent factor in wellbeing (MacLeod & Moore, Citation2000). Positive experience is defined as those activities that are small in magnitude and frequent in occurrence, for example, eating good meals, taking a walk, having someone agree with you (Needles & Abramson, Citation1990). A handful of studies in adults (Johnson, Han, Douglas, Johannet, & Russell, Citation1998; Needles & Abramson, Citation1990; Phillips, Citation1968) and even fewer with young people indicate that positive experiences may be a protective factor in reducing the effect of stressful experiences. Of note, Shahar and Priel (Citation2002) observed that positive life events, particularly positive interpersonal events, had a direct protective effect on the development of depression and appeared to shield against the impact of negative life events in a non-clinical sample of 14–16-year-olds.

Further, limited attention has been given to the role of positive attributional style for positive events as a protective factor in mental health. Macleod and Moore (Citation2000) argue that this may be because a uni-dimensional view of positive and negative cognitive style is promoted, one that is inverse in nature. They claim this perspective is misleading and argue that positive and negative cognitive styles are more usefully thought of as reflecting the operation of two separate systems. Needles and Abramson (Citation1990) also support this view point. Using an adult population, they found that attributional styles for positive and negative events show little correlation even among individuals who have a depressogenic attributional style for negative events and, as a result, that there may be a good deal of variance in attributional style for positive events. Curry and Craighead (Citation1990) observed similar findings with adolescent inpatients diagnosed with depression. They reported that individuals who presented with more severe depression had significantly lower positive attributional style for positive events. Conley, Haines, Hilt, and Metalsky (Citation2001) made similar observations with a non-clinical child population; they observed that children with a more negative attributional style for positive events had greater increases in depressed symptoms across time than did children with a more positive attributional style for positive events. They concluded that the combination of negative attributional style (for positive events) and negative life stress predicted increases in depressive symptoms. These findings are consistent with a multi-factorial model and suggest that the interaction of positive life events and “an enhancing” cognitive style (Needles & Abramson, Citation1990), may be protective, fostering resilience in the face of adversity and moderating the impact of stress and transient symptoms on wellbeing.

That said, intuitively it makes sense that the experience of positive events in childhood might actually lead to the development of a positive attributional template for positive events, which may in turn mediate the relationship between positive events and follow-up depressive symptoms. Indeed it is recognised that moderational and mediational models are not necessarily mutually exclusive but rather that they can amalgamate to produce more complex models of functioning (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986). Inconsistent findings in prospective research of the diathesis–stress interaction in children (e.g., Dixon & Ahrens, Citation1992; Hilsman & Garber, Citation1995; Nolan-Hoeksema, Girgus, & Seligman, Citation1986; Turner & Cole, Citation1994) may be explained by this. Turner and Cole (Citation1994) argued that a mediational rather than a moderational model might better explain the stress–depression relationship in middle childhood, with attributional style becoming a more powerful cognitive moderator of the stress–depression relationship with later development. Of note, there is no empirical investigation to date of the competing hypothesis (moderator vs. mediator) for relations between positive events and positive attributional style for positive events and depressive symptoms in children.

In summary, research supports the association between cognitive styles, life events and depression in children (Conley et al., 2001; Hilsman & Garber, Citation1995). Evidence is less clear, however, with regard to the protective role that cognitive factors, such as positive atributional style, and life events play in the development of depressive symptoms in children. Transactions between these factors may be dynamic and reciprocal, and change over time and developmental course (Muris, 2007; Shortt & Spence, Citation2006). In essence, few studies have investigated the interaction between positive attributional style for positive events and life events in prospectively predicting depressive symptoms in children. Nor have studies considered the interaction between positive events and negative life events in prospectively predicting follow-up depressive symptoms in children. Empirical investigation of cognitive response to positive experience in the wellbeing of children is important to clarify issues related to causal and temporal relationships between these variables and to more accurately identify the trend of their effects across time.

The present study was designed to prospectively examine the relationships between positive attributional style for positive events, life events and depression in children. A non-clinical sample of children was recruited. Participants completed a battery of self-report measures of depression, attributional style, stressful life events, and positive life events on two occasions (approximately 6 months apart).

Drawing on the available literature, it was predicted that positive attributional style would moderate the relationship between number of negative life events and depression severity. Specifically, it was expected that the relationship between negative events and depression would be weaker in children with higher levels of positive attributional style versus children with lower levels. Further, it was predicted that number of positive life events would moderate the relationship between number of negative life events and depression severity. Specifically, it was expected that more positive life events would buffer (i.e., minimise) the degree to which children experienced depression symptoms following negative life events. Finally, based on the premise that moderational and mediational models may join to form more complicated models of functioning (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986), the potentially moderating and mediating role of positive attributional style was explored. In terms of moderation, whether positive attributional style would moderate the relationship between number of positive life events and depression severity was tested; that is, that children high in positive attributional style would experience less depression in the context of fewer positive events relative to children low in positive attributional style. Similarly mediation was also tested. Specifically it was tested whether the relationship between positive life events and depression might also be mediated by attributional style for positive events in children.

Method

Participants

Participants were 102 children (aged 10–12 years) recruited from 10 public and one private primary school in South Australia. The specified age group was targeted on the basis that cognitive risk factors change markedly from childhood to adolescence (Conley et al., 2001) and to reduce cognitive variability. Of the families that completed a demographic information questionnaire (N = 58), 79% indicated that the children lived in a two-parent household; 48% of the families had gross earning >AUD$70,000 p.a. and 16% had gross earnings under AUD$30,000 p.a., with 5% of families earning under AUD$10,000 p.a.

Procedure

Participants were recruited using the following procedure. In the first instance, 15 primary school principals were approached regarding the study. An information pack was then sent to approximately 1700 families at the 11 schools that chose to participate in the research. The information pack contained a participant information sheet, parent/guardian consent and child assent forms and a cover letter provided by each school. In line with ethics approval, the participant information sheet warned parents that questionnaires would be used to probe children's experience of high-impact trauma and suicidality; this likely led to the extremely modest response rate of 6%. Parents/guardians who allowed their children in the study were requested to complete the necessary consent forms and return them to the researcher in the reply-paid envelope as provided. A battery of self-report questionnaires was administered to participants at Time 1 and Time 2 during regular lessons, prior to recess time, at school.

Measures

Depression

The Child Depression Inventory–Short Form (CDI-S: Kovacs, Citation1992) is an established 10-item forced-choice scale designed to assess depression reactions in children and has comparable psychometric properties with the full-form version (Kovacs, Citation1992). It was administered at Time 1 to control for initial levels of depression. Cronbach's alphas were .84 at T1 and .86 at T2 in the present sample.

Attributional Style

The Children's Attributional Style Questionnaire, Revised (CASQ-R: Thompson, Kaslow, Weiss, & Nolan-Hoeksema, Citation1998) is a commonly used 24-item, forced-choice questionnaire, developed to assess children's causal explanations for positive and negative events. Participants were instructed to imagine themselves in a series of events, for example “You get a bad grade at school”, and to decide what caused the event to happen by ticking one of two boxes related to the event, for example, “I am not a good student” or “Teachers give hard tests”. Half of the items in the questionnaire addressed positive outcomes and half addressed negative outcomes. Higher scores reflected a more positive response, while lower scores were associated with elevated depression. Cronbach's alpha for the CASQ-R (administered at T2) was .70 in the present sample, consistent with previous reports of moderate internal consistency reliability (Thompson et al., Citation1998).

Negative life events

The Cambridge Life Development Measure (Goodyer, Herbert, Tamplin, Secher, & Pearson, Citation1997) is a 13-item self-report instrument developed to measure stressful life events (e.g., moving school, losing a family pet). Participants were instructed to answer “yes” or “no” to indicate whether or not each event had occurred within the past 6 months at Time 2. A total scored was calculated for each phase based on the number of events endorsed.

Positive events

The Positive Life Events Checklist is a 36-item self-report measure developed by the author for the present study to measure positive life events such as receiving an award, going to the movies, being praised by a parent (available on request). Participants were instructed to rate how often positive events had happened to them within the past 6 months at Time 2. Each item was answered on a 3-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all) to 2 (lots of the time). A total score was calculated for each phase based on a summation of these responses.

Results

Data screening

Data were screened and cleaned as recommended by Tabachnick and Fidell (1996). Normality testing indicated that some measures were positively skewed, however, results remained the same for both transformed and untransformed data, thus untransformed data are reported.

Participant characteristics

A total of 102 children completed the questionnaires at either T1 or T2: 93 children (51 boys, 42 girls) at T1, and 89 children (49 boys, 40 girls) at T2. No significance difference in child depression levels was found based on parental income (low, medium, high) at T1, F(2,47) = 0.82, p = .44. The psychometric data for the variables of interest for T1 and T2 are detailed in . As expected in a non-clinical group, levels of depressive symptoms were low. Two children scored above the clinical cut-off (>13) on the CDI-S at T1, and one child at T2.

Table I. Psychometric data

Preliminary analyses

Preliminary analyses were conducted to determine if any of the measures of life events, attributional style or symptoms of depression varied as a function of age or gender. The only observed significant correlation was between gender and negative attributional style at T2, r(88) = .29, p = .03. Testing indicated that girls made more adaptive judgements about negative events than boys (girls: M = 21.99, SD = 2.17; boys: M = 20.99, SD = 2.17), t(86) = 2.17, p = .03. Controlling for gender, however, did not impact on any findings relating to this variable, and it was not included as a correlate in any analysis.

Zero-order correlations between each of the T2 predictor variables, number of negative life events, number of positive life events and level of positive attributional style for positive events, and the dependent measure, depression, are reported in . Of note, a moderate correlation was evidenced between attributional styles for positive and negative events r(87) = .41, p < .01, contrary to findings in an adult population (Needles & Abramson, Citation1990).

Table II. Zero-order correlations among variables of interest

Main analyses

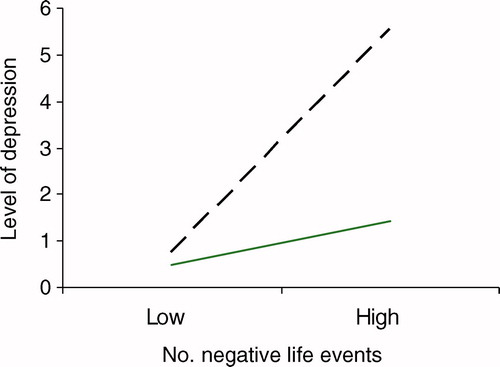

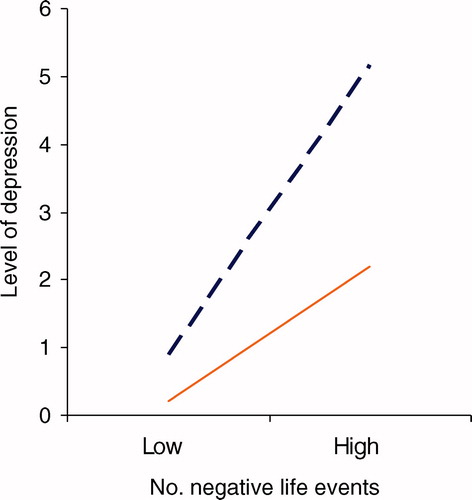

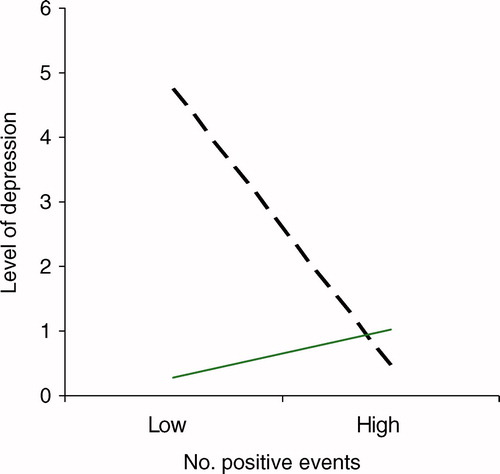

Hierarchical multiple regression analysis (MRA) was used to test moderating hypotheses, with relevant variables centered as per Aiken and West (Citation1993). Where moderational relationships are graphed (–), 1 SD above and below mean values was used to plot interactions. Mediation was tested following the recommendations of Baron and Kenny (Citation1986). Depression at T1 was controlled at Step 1 for all relevant analyses.

Does positive attributional style for positive events moderate the relationship between number of negative life events over the past 6 months and depression at T2?

As expected, initial depressive symptoms were a significant predictor of T2 depressive symptoms, accounting for 39% of the variance explained (). Both number of negative life events and level of positive attributional style for positive events were significant predictors of T2 depressive symptoms, accounting for an additional 19% of the residual change in depressive symptoms. Most importantly, as predicted, level of positive attributional style moderated the relationship between number of negative life events and follow-up depressive symptoms, explaining approximately 5% of unique variance. In other words, children high in positive attributional style for positive events appeared to experience less depression in response to negative life events than children low in positive attributional style for positive events ().

Figure 1. Predicted depressive symptoms as a function of life events and level of attributional style for positive events. (– –) Low positive attributional style; (––) high positive attributional style.

Table III. Prediction of depressive symptoms in children at T2: no. negative life events and level of positive attributional style for positive events

Does number of positive life events over the past 6 months moderate the relationship between number of negative life events and depression at T2?

Similar to the above findings, both number of negative life events and number of positive events were significant predictors of T2 depressive symptoms, explaining an additional 16% of the residual change in depressive symptoms. In contrast to predictions, number of positive life events did not appear to moderate the relationship between number of negative life events and follow-up depressive symptoms, accounting only for an additional 2% of unique variance (). Although the interaction effect did not reach significance, it indicated a positive trend in the predicted direction (p < .06; ).

Figure 2. Predicted depressive symptoms in children as a function of frequency of negative events and frequency of positive events. (– –) Low no. positive events; (––) high no. positive events.

Table IV. Prediction of depressive symptoms in children at T2: no. negative and positive life events

Does level of positive attributional style for positive events moderate the relationship between number of positive life events over the past 6 months and depression at T2?

As predicted, positive attributional style for positive events moderated the relationship between number of positive life events and depressive symptoms at T2, explaining approximately 5% of unique variance (). In other words, children high in positive attributional style for positive events in this period tended to experience fewer depressive symptoms in the context of fewer positive events than children low in positive attributional style for positive events (). As detailed below, however, attributional style also appeared to act as a mediator in this relationship.

Figure 3. Predicted depressive symptoms as a function of frequency of positive events and level of positive attributional style for positive events. (– –) Low positive attributional style; (––) high positive attributional style.

Table V. Prediction of depressive symptoms in children at T2: no. positive life events and level of attributional style for positive life events

Does level of positive attributional style for positive events mediate the relationship between number of positive life events over the past 6 months and depression at T2?

A mediation analysis was conducted following the Baron and Kenny (Citation1986) guidelines, with the significance of any reduced effect reported as a z score. The significance of the indirect effect was tested using the Arioan version of the Sobel test (Baron & Kenny, Citation1986) and the associated beta values are reported in . T1 depression was controlled at Step 1. As predicted, the first three conditions of mediation were met and the strength of the indirect effect was significant, indicating full mediation. The proportion of variance explained by number of positive life events was no longer significant after controlling for level of positive attributional style for positive events, reducing from 7%, F(2,76) = 33.48, p < .001, to 2%F(1,73) = 3.47, p = .07.

Table VI. Positive attributional style mediates relationship between no. positive events and later depressive symptoms: Test

Discussion

This study investigated the relationship between positive attributional style, life events and follow-up depression in children. The hypothesis that positive attributional style would moderate the relationship between number of negative life events and depression severity was supported. As predicted, having a more positive attributional style for positive events minimised the degree to which children experienced depression symptoms following negative life events. The hypothesis that number of positive life events would moderate the relationship between number of negative life events and depression severity, although not supported, indicated a positive trend in the predicted direction. Children who experienced more positive events tended to experience less depression in response to increased negative events relative to children who experienced fewer positive events.

Due to the lack of previous research on the relationship between positive attributional style for positive events, life events and depression in children, it is difficult to directly compare present findings to previous research. That said, the observation that self-reported positive attributional style for positive events may buffer the experience of depression following adverse events in children is consistent with a previous child study (Conley et al., Citation2001). Of note, the present study improved on that of Conley et al. (Citation2001) by increasing the follow-up period from 3 weeks to approximately 6 months. Of further note, the current finding of moderate correlations between attributional styles for positive and negative events is in contrast to adult research (e.g., Needles & Abramson, Citation1990), which has showed little correlation among these variables. It may well be that the operation of two separate attributional systems (Macleod & Moore, Citation2000) develops or becomes more noticeable with age; or that the experience of negative life events over time can change attributional style. This is highly speculative, however, and requires further investigation. The observed trend that number of positive events experienced by children may become an increasingly important protective factor with greater exposure to negative events is consistent with both adolescent (Shahar & Priel, Citation2002) and adult studies (Needles & Abramson, Citation1990) that found that positive events had a direct protective effect on level of depression following adverse experience.

These finding are in line with a multi-factorial model for the development of psychopathology in children (Muris, Citation2007), and suggest that positive attributional style for positive events and perhaps positive events themselves may be protective factors that could reduce children's vulnerability to depressive symptoms regardless of the number of negative life events they experience. The present study further demonstrated that positive attributional style moderates the relationship between number of positive life events and depression severity; as predicted, children high in positive attributional style experienced less depression in the context of fewer positive events relative to children low in positive attributional style. Of note, the study also demonstrated that positive attributional style appeared to mediate the relationship between positive life events and depressive symptoms in the present age group; children who experienced more positive events experienced less depression, but positive events explained less variance in depressive symptoms after controlling for positive attributional style.

The observation that positive attributional style can act as both a mediator and moderator may explain inconsistent results in research of the diathesis–stress interaction across childhood (Turner & Cole, Citation1994). Although speculative, it may well be that early experience of positive events contributes to the development of a positive attributional style for positive events, and this construct simultaneously starts to moderate the relationship between positive events and depression in children. It may even be that over time, the construct becomes a more robust moderator of the relationship between positive events and depression.

This preliminary support for a combined model has implications for future research. If the development of children's positive attributional style is related to the positive events they experience, it would seem important to examine the nature of this relationship further. For instance, are some positive events more important than others? Does frequency of occurrence of positive experience make any difference to outcome? Further, if positive attributional style is an unstable construct in middle childhood (Cole & Turner, Citation1993), when does it start to stabilise? What happens to the proposed mediational–moderational model with age?

Several limitations are acknowledged in the present study. First, participants were primary school students who experienced considerably milder depressive symptoms than may be the case in a clinical population. As such it would be important to replicate these findings in a more clinically relevant population. Second, given the low response rate of 6%, the sample was small in size and unlikely to be representative. Anecdotally, it is worth noting that several parents contacted the researcher during the recruitment phase of the study to report that although they approved of the study, they were not comfortable with their children being asked questions related to trauma and suicidality. Further, staff at three schools reported concerns about parents being approached, given the nature of the test battery, and as a result denied recruitment access to their school. The low response rate dictated that the study was very preliminary in nature. That said, findings justify further examination of issues raised in a larger sample. Strategies for addressing the low uptake rate in future research of these issues might include providing parents with more detailed information about the nature of the questions being asked (e.g., highlighting that they are not harmful, perhaps via information sessions at parents' evening). Alternatively, research instruments might be accessed online, once ethics considerations have been taken into account, to further promote anonymity.

Third, despite its prospective design, the present study restricted its cohort to children between the ages of 10 and 12 years. Although this strategy reduced variability in cognitive vulnerability, it precluded the examination of developmental effects. As suggested above, developmental effects are important considerations given inconsistent research findings regarding mediational and moderational models of attributional functioning across childhood (Dixon & Ahrens, Citation1992; Hilsman & Garber, Citation1995; Turner & Cole, Citation1994). Fourth, the present study was correlational in nature, indicating that results do not represent a complete test of causality. Future research is likely to be fruitful if it is more longitudinal in nature, beginning with much younger children. This will enable the relationship of critical variables to be examined more fully in a prospective manner. Further, a larger sample size would provide a more representative sample and allow more complex statistical analyses, for example, structural equation modelling (SEM) to better understand mediational, moderational and bi-directional relationships. Fifth, a self-report measure of depression cannot replace clinical interview and diagnosis. Future investigation could incorporate clinical interview and thus the possibility of testing more clinically relevant populations alongside asymptomatic child populations. This would be useful, given findings with adolescent inpatients (Curry & Craighead, Citation1990) that report significantly lower positive attributional style for positive events in more severely depressed subjects; and given studies with adults populations (e.g., Southall & Roberts, Citation2002) that suggest that the interaction of the present predictor variables may enhance recovery from depression. That is, that depressed adults who have a more adaptive style for positive events may experience greater improvement in symptoms following positive events than those with a less adaptive attributional style. Sixth, demographic information suggested that the majority of participants resided in two-parent, relatively high-income families. Thus, it is conceded that the present sample was likely a stable group, from reasonably affluent, intact families, and experiencing minimal symptoms. Given these potential floor effects, it would seem pertinent that the present study evidenced significant results, and that the proportion of variance explained, although small, constituted reasonably sized effects for interaction analyses.

In terms of life events, it is conceded that recall and memory biases may exist in self-report; children who are more depressed may have a bias for recalling negative events that more positive children do not have or forget about. Equally, children who are more depressed may recall less positive events than positive children. Further, it is noted that the present study measured only occurrence of life events without reference to the degree of pleasure or distress that events caused. With this in mind, the present study attempted to reduce the effect of children's mood on their rating of life events by controlling for prior depressive symptoms, but it is acknowledged that future investigations could be extended to encompass interview-based assessments of life events (Southall & Roberts, Citation2002) and perhaps confirmation of children's experience from parents. Finally, attention is drawn to the fact that the present study focused on the occurrence of negative events such as moving house or school, spending time in hospital or having difficulties with friendships, without reference to traumatic events such as assault or motor vehicle accident. That said, hassles experienced by participants proved to be significant events in their lives. Future research may benefit from multiple measures of life events, including those of both daily hassles and higher impact traumatic events to determine whether the relationships noted above hold for high impact traumatic events too.

In conclusion, the present findings highlight the possibility that protective factors may foster resilience in the face of adversity and reduce the potential impact of depressive symptoms in children. They also illustrate, however, that future research is needed to develop a clearer understanding of the development of positive attributional style, and the manner in which it moderates and/or mediates the association between life events and depressive symptoms throughout childhood. This will provide increased evidence of both vulnerability and protective factors. These are important considerations because they have very real implications for prevention and early intervention in childhood depression (Barrett & Ollendick, Citation2004).

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the schools and their staff who participated in the study for their help and assistance. We would also like to thank the families, and particularly the children who participated in the study.

References

- Abramson, L. Y., Metalsky, G. I., and Alloy, L. Y., 1989. Hopelessness depression: A theory-based subtype of depression, Psychological Review 96 (1989), pp. 358–372.

- Aiken, L. S., and West, S. G., 1993. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Newbury Park, CA: Sage; 1993.

- Baron, R. M., and Kenny, D. A., 1986. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (1986), pp. 1173–1182.

- Barrett, P. M., and Ollendick, T. H., 2004. Handbook of interventions that work with children and adolescents. UK: John Wiley & Sons; 2004. pp. 430–469.

- Campbell, S. B., 1986. "Developmental issues in childhood anxiety". In: Gittelman, R., ed. Anxiety disorders of childhood. New York: Guilford; 1986. pp. 24–52.

- Coie, J. D., Watt, N. F., West, S. G., Hawkins, J. D., Asarnow, J. R., Markman, H. J., et al., 1993. The science of prevention: A conceptual framework and some directions for a national research program, American Psychologist 48 (1993), pp. 1013–1022.

- Cole, D. A., and Turner, J. E., 1993. Models of cognitive mediation and moderation in child depression, Journal of Abnormal Psychology 102 (1993), pp. 271–281.

- Conley, C. S., Haines, B. A., Hilt, L. M., and Metalsky, G. I., 2001. The children's attributional style interview: Developmental tests of cognitive diathesis-stress theories of depression, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 29 (2001), pp. 445–463.

- Curry, J. F., and Craighead, W. E., 1990. Attributional style in clinically depressed and conduct disordered adolescents, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 58 (1990), pp. 109–115.

- Dixon, J. F., and Ahrens, A. H., 1992. Stress and attributional style as predictors of self-reported depression in children, Cognitive Therapy and Research 16 (1992), pp. 623–634.

- Goodyer, I. M., Herbert, J., Tamplin, A., Secher, S. M., and Pearson, J., 1997. Short term outcome of M.D.II, life events, family dysfunction and friendship differences as predictors of persistent disorder, Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry 36 (1997), pp. 474–480.

- Hilsman, R., and Garber, J., 1995. A test of the cognitive diathesis-stress model of depression in children: Academic stressors, attributional style, perceived competence and control, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 69 (1995), pp. 370–380.

- Horowitz, J. L., and Garber, J., 2006. The prevention of depressive symptoms in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 74 (2006), pp. 401–415.

- Johnson, J. G., Han, Y., Douglas, C. J., Johannet, C. M., and Russell, T., 1998. Attributions for positive life events predict recovery from depression among psychiatric inpatients: An investigation of the Needles and Abramson model of recovery from depression, Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology 66 (1998), pp. 369–376.

- Kovacs, M., 1992. The Children's Depression Inventory (CDI). Tonawanda, NY: Multi-Health Systems; 1992.

- Macleod, A. K., and Moore, R., 2000. Positive thinking revisited: Positive cognitions, well-being and mental-health, Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy 7 (2000), pp. 1–10.

- Muris, P., 2007. Normal and abnormal fear and anxiety in children and adolescents. California: Elsevier Inc; 2007.

- Needles, D. J., and Abramson, L. Y., 1990. Positive life events, attributional style, and hopelessness: Testing a model of recovery from depression, Journal of Abnormal Psychology 99 (1990), pp. 156–165.

- Nolan-Hoeksema, S., Girgus, J. S., and Seligman, M. E. P., 1986. Learned helplessness in children: A longitudinal study of depression, achievement, and attributional style, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 51 (1986), pp. 435–442.

- Phillips, D. L., 1968. Social class and psychological disturbance: The influence of positive and negative experiences, Social Psychiatry 3 (1968), pp. 41–46.

- Resnick, M. D., Bearman, P. S., Blum, R. W., Bauman, K. E., Harris, K. M., Jones, J., et al., 1997. Protecting adolescents from harm: Findings from the National Longitudinal Study of Adolescent Health, Journal of the American Medical Association 278 (1997), pp. 823–832.

- Rutter, M., 1985. Resilience in the face of adversity: Protective factors and resistance to psychiatric disorders, British Journal of Psychiatry 147 (1985), pp. 598–611.

- Schoon, I., 2006. Risk and resilience: Adaptations in changing times. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006.

- Shahar, G., and Priel, B., 2002. Positive life events and adolescent emotional stress. In search of protective-interactive processes, Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology 21 (2002), pp. 645–668.

- Shortt, A. L., and Spence, S. H., 2006. Risk and protective factors for depression in youth, Behaviour Change 23 (2006), pp. 1–30.

- Southall, D., and Roberts, J. E., 2002. Attributional style and self-esteem in vulnerability to adolescent depressive symptoms following life stress: A 14 week prospective study, Cognitive Therapy and Research 26 (2002), pp. 563–579.

- Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S., 1996. Using multivariate statistics. New York: Harper Collins; 1996.

- Thompson, M., Kaslow, N. J., Weiss, B., and Nolan-Hoeksema, S., 1998. Children's Attributional Style Questionnaire–Revised: Psychometric examination, Psychological Assessment 10 (1998), pp. 166–170.

- Tram, J. M., and Cole, D. A., 2000. Self perceived competence and the relation between life events and depressive symptoms in adolescence: Mediator or moderator?, Journal of Abnormal Psychology 109 (2000), pp. 753–760.

- Turner, J. E., and Cole, D. A., 1994. Developmental differences in cognitive diatheses for child depression, Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology 22 (1994), pp. 15–32.