ABSTRACT

Young people living in regional and rural areas of Australia are at an increased risk of suicide and have unique barriers and facilitators to seeking mental health support. As such, specific mental health and suicide prevention programmes that are tailored to young people within their communities are required. Despite this, peer-reviewed literature on such interventions is scant. In this commentary, we outline an existing rural place-based programme; Live4Life, created in 2009 in the Macedon Ranges, Victoria, and now running in nine Australian regional communities. We demonstrate that Live4Life shows promise in building the capacity of whole communities to support young people to recognise and seek help for mental health concerns. As such, we argue the need for further evaluation comparing Live4Life communities with matched control communities to assess the long-term impact of the programme and to support the upscaling of Live4Life across Australian regional and rural communities.

Key Points

What is already known about this topic:

Young people face the highest burden of mental ill-health in Australia, with adolescent mental health challenges having long-lasting impacts on functioning and quality of life.

Regional and rural Australians are particularly at risk, experiencing increased suicide rates and additional barriers to accessing mental health services.

Place-based approaches to suicide prevention, which engage local communities have been identified as a need for regional and rural communities.

What this topic adds:

We outline the community-led programme Live4Life, which aims to increase community knowledge of youth mental health and encourage help-seeking behaviour in young people.

We discuss the existing evidence demonstrating the potential impact of the Live4Life model on the communities in which it is implemented.

We offer suggestions for future research evaluating the efficacy of the programme by comparing communities with Live4Life implemented to matched control communities.

Introduction

“We’re not saying we can solve suicide. But we can try to get to those young people earlier, and build another layer, a protective layer into that community”. Founder, Youth Live4Life Macedon Ranges

Young people face a high mental ill-health burden, with suicide being the leading cause of death in 15-24-year-olds in Australia (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2022). Adolescent mental health challenges can have lasting consequences, including poor functioning, social isolation, and reduced participation in education and the workforce (McGorry & Mei, Citation2018). Rural and regional Australians are particularly impacted, with suicide rates increasing with remoteness classification (i.e., 15.1 per 100,000 in the inner regional compared with 19.3 per 100,000 in remote areas) (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, Citation2020). The mental health gap between metropolitan and regional areas has increased significantly since 2016 as rates of depression, anxiety, and self-harm increase in regional areas (Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Citation2019). Importantly, some evidence suggests that upwards of 60% of the young people attempting to access mental health services in regional and rural areas are unable to do so (Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System, Citation2019). Responding to the mental health needs of young Australians provides a powerful opportunity as 75% of those who develop mental illness have their first experience of mental ill-health before the age of 25 (Productivity Commission, Citation2019). Consequently, preventative programmes tailored towards young people and their communities that build mental health literacy and promote help-seeking are required to support the prevention of long-term detrimental impacts of mental ill-health.

The National Mental Health Commission (Citation2014) Review of Mental Health Programs and Services highlighted an imbalanced focus on acute and crisis services rather than on prevention and early intervention, with services being provided too late in a person’s life or disease trajectory, resulting in avoidable escalation of illness and associated implications (National Mental Health Commission, Citation2014). For those in rural communities, issues can be further compounded by limited access to services, along with stigma and a lack of knowledge of mental ill-health and potential supports which serve as barriers to help-seeking (Kaukiainen & Kõlves, Citation2020; Marshall & Dunstan, Citation2013). These barriers of stigma and low mental health literacy may be amenable to change through programmes targeting awareness and psychoeducation (Kaukiainen & Kõlves, Citation2020). Indeed, mental health literacy, community cohesion and engagement, and trusting relationships with adults (parents, teachers, and counsellors) have been identified as facilitators to help-seeking (Velasco et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, for young people who are unlikely to disclose feelings of distress (Calear et al., Citation2016), building capacity of communities to recognise the signs of mental ill-health in young people will aid in early identification and response to distress.

Reviews of youth-focused mental health and suicide prevention programmes position schools as a critical gateway for delivering universal mental health interventions given their reach with young people, teachers, and parents or carers (Calear et al., Citation2016; Morken et al., Citation2020; Robinson et al., Citation2018a). Existing interventions offer insight into the potential of such programs; for example, the Youth Aware of Mental Health Program (YAM) has been shown to facilitate increased mental health knowledge and help-seeking intentions (McGillivray et al., Citation2021), decreased mental health stigma (Lindow et al., Citation2020), and reduced suicidal ideation and attempts in young people (McGillivray et al., Citation2021; Wasserman et al., Citation2015). In conjunction with school-based interventions, place-based approaches, which engage the community as an active partner to support those with an identified need are particularly suitable to, and necessary for, rural and regional areas (Jones et al., Citation2015; Zaheer et al., Citation2011). Despite this, a recent scoping review identified a lack of peer-reviewed evidence for co-produced community mental health initiatives in regional and rural Australia, with only three of the 13 initiatives reviewed having a youth focus (De Cotta et al., Citation2021). Taken together and with the rural context in mind, programmes that can be embedded within local communities, and that are developed specifically for, and acceptable to, young people are required (Robinson et al., Citation2018a). Live4Life fills this gap; targeting awareness of mental health through the implementation of evidence-based mental health literacy programmes that engage with young people, teachers, and parents, building the capacity of communities to identify, respond to, and support young people experiencing mental distress.

The Live4Life model

Youth Live4Life Ltd. (Youth Live4Life) is a not-for-profit entity; its mission is to expand the reach of the Live4Life model into rural and regional Australia. The Live4Life initiative commenced in 2009 in response to the suicides of two young people in the Shire of Macedon Ranges in Victoria, where it has undergone progressive innovations into the current model. The initiative engages local councils, schools, health and community organisations in a governance group called the Partnership Group, which oversees the implementation of the Live4Life model in the local area.

Youth Live4Life’s purpose is to reduce youth suicide in rural communities through reducing barriers to help seeking, decreasing mental health stigma, increasing awareness of local professional help, increasing the mental health knowledge of secondary school-aged students, school staff, parents, and community members, and building community resilience to address common mental health problems. The Live4Life model adopts schools as a key site for intervention, with additional wrap-around intervention and supports. Live4Life is intended to drive generational change. By delivering successive interventions to all young people in the community, the response capacity and prevalence of normalising attitudes and behaviours in the community is anticipated to expand upwards through the generations over time.

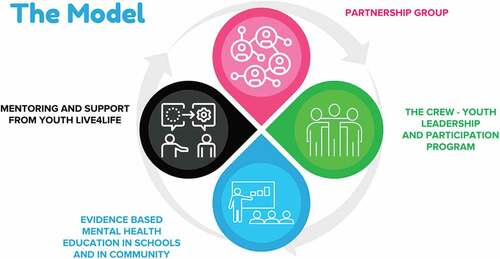

Youth Live4Life implements established and evidence-based Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training as part of its model to increase mental health literacy and promote help-seeking. Youth MHFA is delivered to adults supporting young people, and Teen MHFA is delivered directly to young people using age-appropriate learning materials (Ng et al., Citation2021). Youth Live4Life works with rural communities to establish and implement the Live4Life model. The four essential and locally adaptable components of the Live4Life model are:

Support, mentoring and evaluation by Youth Live4Life, whereby Youth Live4Life staff guide communities through implementation of the model using a community engagement approach valuing local knowledge and skills.

The development of a School and Community Partnership Group. Senior community and school leaders drive implementation and provide local oversight. A lead agency is appointed (commonly local government) for contractual and funding arrangements.

Delivery of evidence-based suicide prevention and mental health education across all local secondary schools and community settings.

Delivery of the youth leadership and participation programme with a “Crew” of young people aged 15 and 16 (Years 9 and 10). The Crew is given further mental health education and with support, collectively “drives” reinforcing messaging across all schools and delivers promotional events.

Critically, the model focuses on engaging a range of community stakeholders and allows for some tailoring of approaches to the specific community. Programme settings are described in .

Table 1. Live4life programme settings.

Theory of change

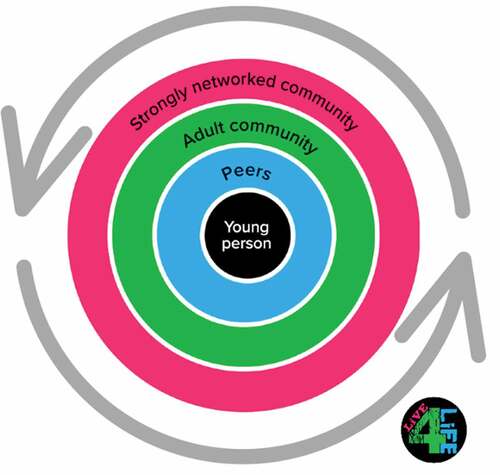

A theory of change for the Live4Life model has been developed (see ). Live4Life places young people at the centre, delivering targeted, evidence-based mental health education at ages 14 and again at ages 16 or 17. Wrapped around the intervention with students, is the peer-led Crew component, and around them the community more broadly. Further, the Partnership Group structure of Live4Life is designed to strengthen the links between local government, schools, and health services, so that the community is well placed to respond to issues impacting the mental health of young people.

Figure 1. A wrap around model with the young person at the centre. Figure reprinted with permission from Live4Life.

The formal education component is reinforced through repeated and engaging peer-led messaging delivered by the Live4Life Crew, in recognition of the influence of peers on the target cohorts. Whole-of-community events for year 8 students involve participation by and promotion of local mental health services, to further break down stigma and build familiarity among young people with local counsellors and clinicians. Adults who are engaged with young people (parents, teachers, and others) are also delivering formal MHFA training to increase their competence and confidence to identify and respond to mental health issues appropriately. Over time, the critical mass of Live4Life alumni is assumed to influence broader community attitudes and behaviours relating to mental illness. These components aim to ensure that young people experiencing mental health issues are referred to appropriate clinical support. Further, where young people experience access issues and lengthy wait times to access support in rural communities, Live4Life aims to better resource the community to support these young people in the interim. See for a full overview of the Youth Live4Life model.

Community reflections and future research directions

Since its conception in 2009, Live4Life has expanded across nine regional communities in Victoria. In 2017, Live4Life was expanded to two additional pilot sites in Benalla and Glenelg, with potential to expand into further regional communities in subsequent years. In 2018, Youth Live4Life was funded to work with the Benalla and Glenelg communities for a further three years (2018–2020). In expressing interest in implementing the Live4Life model, communities highlight the impact that youth mental ill-health and suicide is having on their community, and the need for primary prevention programmes. At the commencement of 2022, Live4Life is now being implemented in an additional six communities: Bass Coat, Baw Baw Shire, Central Goldfields Shire, Moira Shire, South Gippsland, and Southern Grampians Shire.

Youth Live4Life implements evidence-based mental health education, embedded within, and tailored to local communities, empowering local organisations to take ownership of the programme and facilitating sustainable cultural change. Systematic review provides strong evidence for the Youth and Teen MHFA training implemented as part of the Live4Life model in facilitating significant improvements in knowledge and recognition of mental illness, confidence to provide help, and help-seeking intentions, as well as reducing stigmatising attitudes, with promising evidence for sustained outcomes post training (Ng et al., Citation2021). Preliminary evaluation of the Live4Life model has shown that the model aligns well with national and international policy on suicide prevention and is consistent with current state and federal policy in identifying young people in rural and regional communities as a particularly vulnerable group, and in recognising the importance of a holistic, community-based approach (Robinson et al., Citation2018b). Further independent evaluation was undertaken with 954 participants (818 young people and 136 adults) across two Live4Life communities in the second and third years of programme implementation. Findings validated the effectiveness of the model as it is transferred to new communities, with support from Live4Life, adequate and ongoing funding, and engagement of initiative champions at each school identified as key factors supporting model transferability and sustainability (Ludowyk, Citation2020). Further, findings indicate that the model increases the knowledge and confidence of young people, and those around them (such as teachers, parents, and others in the community), to identify mental health issues in young people and link them with appropriate support (Ludowyk, Citation2020). These findings indicate the promise of the Live4Life model in its ability to reach all young people engaged at school in its communities and support the community members to “hold” their young people experiencing mental health needs who frequently experience challenges gaining timely access to services. “Holding” young people in this context does not imply attempting to replace treatment or clinical care, but rather to hold supportive and empathetic attitudes, and be informed about pathways to professional support. Live4Life community members identified the need to acquire these skills in the context of service scarcity, where the alternative; young people receiving little community support whilst experiencing mental ill-health was seen as unacceptable (Ludowyk, Citation2020).

While the above evidence demonstrates the potential of the Live4Life model, formal research evaluating the programme is required. Specifically, longitudinal methodologies implementing pragmatic designs that allow for comparisons between Live4Life communities and those without the programme are needed. As the Live4Life intervention is designed to be delivered to young people at multiple timepoints across high school, designs, which look at the impact of the model at different age brackets would allow researchers to see the impact of Live4Life as young people age, assessing key outcomes with comparisons to matched control communities. Beyond self-report methods, researchers were able to look at population data indicative of help-seeking behaviour and distress, including youth suicide rates, emergency presentations, and mental health care items in Live4Life communities to evaluate the impact. Such investment in longitudinal methodologies would provide rigorous evaluation data strengthening the knowledge base around what works in community-based youth suicide prevention.

The above research recommendations could be considered within a participatory action research (PAR) framework (Baum et al., Citation2006). PAR involves conducting research with communities instead of on communities and has been promoted as appropriate for evaluation of health and wellbeing interventions in socially or economically disadvantaged communities (Kidd et al., Citation2018), as community members are engaged in the design and conduct of the research (Grattidge et al., Citation2021). Such an approach is congruent with the Live4Life model given community-based approaches, allowing for intervention implementation and evaluation research to occur in tandem. PAR has been used previously in suicide prevention with success (Grattidge et al., Citation2021).

In this commentary, we describe the Live4Life model, discussing how the initiative responds to the rural context and effectively engages local communities. An early evaluation of Live4Life highlights the programmes potential positive impacts on young people, their teachers and carers, and whole communities in the areas in which it has been established (Ludowyk, Citation2020). Formal evaluation data would aid in understanding the efficacy of the Live4Life model as a youth suicide prevention programme, supporting the upscaling of the model across rural and regional areas in Australia to address the growing mental health needs of young people and their communities.

Acknowledgements

Youth Live4Life would like to acknowledge Macedon Ranges Shire Council and foundational funders: The Myer Foundation, The Jack Brockhoff Foundation and The Ross Trust, as well as the support of the Victorian Government.

Disclosure statement

Natasha Ludowyk sits on the the Program Lifecycle Review Subcommittee for the board of Youth Live4Life, as a voluntary member. The Editor-in-Chief of Australian Psychologist also sits on the Program Lifecycle Review Subcommittee for the board of Youth Live4Life as a voluntary member, and was previously on the Youth Live4Life Board, as a voluntary board member in 2018/19.

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2020). Deaths by suicide by remoteness area. https://www.aihw.gov.au/suicide-self-harm-monitoring/data/geography/suicide-by-remoteness-areas

- Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2022). Deaths in Australia. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/life-expectancy-death/deaths-in-australia/contents/leading-causes-of-death

- Baum, F., MacDougall, C., & Smith, D. (2006). Participatory action research. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 60(10), 854–857. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech.2004.028662

- Calear, A. L., Christensen, H., Freeman, A., Fenton, K., Busby Grant, J., van Spijker, B., & Donker, T. (2016). A systematic review of psychosocial suicide prevention interventions for youth. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(5), 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-015-0783-4

- De Cotta, T., Knox, J., Farmer, J., White, C., & Davis, H. (2021). Community co-produced mental health initiatives in rural Australia: A scoping review. The Australian Journal of Rural Health, 29(6), 865–878. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12793

- Grattidge, L., Purton, T., Auckland, S., Lees, D., & Mond, J. (2021). Participatory action research in suicide prevention program evaluation: Opportunities and challenges from the National Suicide Prevention Trial, Tasmania. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 45(4), 311–314. https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.13116

- Jones, S., Walker, C., Miles, A. C., De Silva, E., & Zimitat, C. (2015). A rural, community-based suicide awareness and intervention program. Rural and Remote Health, 15(1), 2972. https://doi.org/10.22605/rrh2972

- Kaukiainen, A., & Kõlves, K. (2020). Too tough to ask for help? Stoicism and attitudes to mental health professionals in rural Australia. Rural and Remote Health, 20(2), 5399. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH5399

- Kidd, S., Davidson, L., Frederick, T., & Kral, M. J. (2018). Reflecting on participatory, action-oriented research methods in community psychology: Progress, problems, and paths forward. American Journal of Community Psychology, 61(1–2), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12214

- Lindow, J. C., Hughes, J. L., South, C., Gutierrez, L., Bannister, E., Trivedi, M. H., & Byerly, M. J. (2020). Feasibility and acceptability of the Youth Aware of Mental Health (YAM) intervention in US adolescents. Archives of Suicide Research : Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 24(2), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2019.1624667

- Ludowyk, N. (2020). Evaluation of Live4Life in Benalla rural city council and Glenelg Shire summary report. Ludowyk Evaluation. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5f0d6fe4e9641e63d8cad956/t/5f7bb8805ec0ad374a7ff0a5/1601943714359/1+2020+Live4Live+Evaluation+Two-year+Report.pdf

- Marshall, J. M., & Dunstan, D. A. (2013). Mental health literacy of Australian rural adolescents: An analysis using vignettes and short films. Australian Psychologist, 48(2), 119–127. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2011.00048.x

- McGillivray, L., Shand, F., Calear, A. L., Batterham, P. J., Rheinberger, D., Chen, N. A., Burnett, A., & Torok, M. (2021). The Youth Aware of Mental Health program in Australian secondary schools: 3-and 6-month outcomes. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00503-w

- McGorry, P. D., & Mei, C. (2018). Early intervention in youth mental health: Progress and future directions. Journal of Evidence Based Mental Health, 21(4), 182–184. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmental-2018-300060

- Morken, I. S., Dahlgren, A., Lunde, I., & Toven, S. (2020). The effects of interventions preventing self-harm and suicide in children and adolescents: An overview of systematic reviews. F1000Research, 8, 890. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.19506.2

- National Mental Health Commission. (2014). The national review of mental health programmes and services. NMHC. https://www.mentalhealthcommission.gov.au/getmedia/b51d09c5-c7d9-405a-b9eb-911b2b5ca9a6/Monitoring/Vol-1.pdf

- Ng, S. H., Tan, N. J. H., Luo, Y., Goh, W. S., Ho, R., & Ho, C. S. H. (2021). A systematic review of youth and teen mental health first aid: Improving adolescent mental health. Journal of Adolescent Health, 69(2), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadohealth.2020.10.018

- Productivity Commission. (2019). Mental health, draft report. https://www.pc.gov.au/inquiries/completed/mental-health/draft

- Robinson, J., Bailey, E., Witt, K., Stefanac, N., Milner, A., Currier, D., Pirkis, J., Condron, P., & Hetrick, S. (2018a). What works in youth suicide prevention? A systematic review and meta-analysis. EClinicalMedicine, 4, 52–91. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eclinm.2018.10.004

- Robinson, J., Thorn, P., Byrne, S., Bailey, E., & Kennedy, V. (2018b). An evaluation of the implementation of the Live4Life community youth suicide prevention and mental health promotion model in two rural Victorian communities. Orygen, the National Centre of Excellence in Youth Mental Health.

- Royal Commission into Victoria’s Mental Health System. (2019). Interim Report. Parl Paper No. 87 (2018-2019). http://rcvmhs.archive.royalcommission.vic.gov.au/interim-report.html

- Velasco, A. A., Cruz, I. S. S., Billings, J., Jimenez, M., & Rowe, S. (2020). What are the barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for common mental health problems in adolescents? A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 293. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02659-0

- Wasserman, D., Hoven, C. W., Wasserman, C., Wall, M., Eisenberg, R., Hadlaczky, G., Kelleher, I., Sarchiapone, M., Apter, A., Balazs, J., Bobes, J., Brunner, R., Corcoran, P., Cosman, D., Guillemin, F., Haring, C., Iosue, M., Kaess, M., Kahn, J. P. … Carli, V. (2015). School-based suicide prevention programmes: The SEYLE cluster-randomised, controlled trial. The Lancet, 385(9977), 1536–1544. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61213-7

- Zaheer, J., Links, P. S., Law, S., Shera, W., Hodges, B., Tsang, A. K. T., Huang, Z., & Liu, P. (2011). Developing a matrix model of rural suicide prevention. International Journal of Mental Health, 40(4), 28–49. https://doi.org/10.2753/IMH0020-7411400403