?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Objective

The relationship between ADHD and procrastination is recognised among therapists and educators. However, only a few studies confirm this correlation, and even fewer offer a theoretical explanation. A model of procrastination exists in Steel’s Temporal Motivation Theory, according to which procrastination is fostered by the following motivation factors: a low expectancy of completing the task successfully, negative task value, and impulsiveness – the sensitivity to the delay until realisation. This study aims to establish the correlation between procrastination and ADHD and examine whether these motivation factors explain this correlation.

Method

Two hundred and two adult participants completed an online survey containing demographic background and scales of adult ADHD symptoms, procrastination, expectancy, task aversiveness, and impulsiveness.

Results

ADHD symptoms significantly and positively correlated with procrastination, task aversiveness, and impulsiveness and negatively correlated with expectancy (all Ps < .001). Mediation analysis suggested that lower expectancy and higher impulsiveness partially explained the correlation between ADHD and procrastination.

Conclusions

These findings help establish the strong relationship between ADHD and procrastination while demonstrating that the relationship is partially explained by a low expectancy of completing a task successfully and high levels of impulsiveness.

Key Points

What is already known about this topic:

Adult ADHD symptoms are associated with functional impairment.

The relationship between ADHD and procrastination is recognised among therapists and educators.

Few controlled studies established and explained the link between ADHD and procrastination.

What this topic adds:

In an adult sample, ADHD symptoms are related to a higher level of procrastination.

ADHD symptoms and procrastination correlated with low expectancy of completing the task, high task aversiveness, and high impulsiveness.

Mediation analysis suggested that lower expectancy and higher impulsiveness partially explained the correlation between ADHD and procrastination.

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is a neurodevelopmental condition characterised by a persistent pattern of inattentive, hyperactive, and impulsive behaviour, leading to functional impairment (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). ADHD is often fraught with co-occurring mental health conditions and adversely affects long-term academic outcomes, health-related quality of life, work productivity, and regular daily activities (Faraone et al., Citation2021). Procrastination is a major challenge for many individuals, and those with ADHD are even more likely to struggle with it. This article will examine the relationship between procrastination and ADHD and suggest an explanation for this relationship based on the temporal motivation theory.

The presence of procrastination among individuals with ADHD is well-recognised by educators and clinicians (Langberg et al., Citation2018; Prevatt, Citation2016; Ramsay, Citation2020; Safren, Citation2006; Solanto & Scheres, Citation2020; Solanto et al., Citation2008; Young & Myanthi Amarasinghe, Citation2010). Procrastination, defined as a voluntary but irrational delay of an intended course of action (Steel, Citation2007), is yet to be officially acknowledged as an ADHD symptom or functional impairment. To illustrate this association, a newly developed adult ADHD screening scale comprises six items, one of which probes procrastination: “How often do you put things off until the last minute?” (Ustun et al., Citation2017). Using a question about procrastination in screening for ADHD attests to a frequent co-occurrence of these two phenomena.

Procrastination is increasingly recognised as contributing to several adverse outcomes in different domains, including academic performance (Kljajic et al., Citation2021), health behaviour (Sirois, Citation2021), personal finance (Gamst-Klaussen et al., Citation2019), work (Metin et al., Citation2018; Nguyen et al., Citation2013), and general well-being (Sirois & Pychyl, Citation2016). In light of the critical impact that ADHD and procrastination have on a wide variety of aspects of life, it is vital to understand their relationship.

Hitherto, few studies have documented the association between ADHD and procrastination. Adults with ADHD reported significantly higher rates of different types of procrastination than similar demographic profile adults without ADHD (Ferrari & Sanders, Citation2006). Measures of procrastination, hoarding, and ADHD were positively correlated among adults referred for evaluation of adult ADHD (Ashworth & Mccown, Citation2018). Niermann and Scheres (Citation2014) used various measures of procrastination to study the association with ADHD in a sample of university students. It was found that inattention, rather than hyperactivity and impulsivity, correlated with general procrastination.

Notably, one of the symptoms of ADHD is “Often avoids, dislikes, or is reluctant to do tasks that require mental effort over a long period of time (such as schoolwork or homework)” (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013). As this symptom largely overlaps with the definition of procrastination, it might underlie the association. The first goal of the current study was to examine the association between ADHD and procrastination further while controlling for this overlapping symptom.

Thus far, even fewer studies have examined possible explanations for the association between ADHD and procrastination. An exception is a recent study by Altgassen et al. (Citation2019), which found that both ADHD and procrastination were related to deficits in everyday prospective memory, i.e., difficulties with remembering to carry out intentions. Statistically, prospective memory performance mediated the link between ADHD symptoms and procrastination behaviour (Altgassen et al., Citation2019). Given this gap in the literature, this study’s second goal was to examine a theory-based explanation of the association between ADHD and procrastination.

Probably the most influential theory aiming to explain procrastination is the Temporal Motivation Theory (TMT), which emphasises the impact of time on allocating attention and effort to particular tasks (Steel & König, Citation2006). According to this theory, the mechanism underlying motivation to complete a task can be primarily represented by the following equation:

The greater one’s expectancy for completing the task, the higher will be one’s motivation (and lower one’s procrastination). The more aversive the task value, the longer the delay until the outcome is realised, and the higher the impulsiveness (the sensitivity to that delay), the lower one’s motivation (and higher one’s procrastination). Specifically, TMT argues that motivation increases exponentially as the completion deadline nears.

Past research suggests that ADHD relates to these three motivational factors. The expectancy of task completion is strongly represented by self-efficacy, assessed primarily for the academic and work domains. It was demonstrated that adult ADHD symptoms correlated with low self-efficacy (Schmidt-Barad et al., Citation2021). Aversive task value is strongly represented by boredom, which was consistently associated with ADHD (Golubchik et al., Citation2020; Malkovsky et al., Citation2012; Pironti et al., Citation2016). Sensitivity to delay overlaps with steeper delay discounting, which has been linked to ADHD in several meta-analyses (Jackson & MacKillop, Citation2016; Marx et al., Citation2018, Citation2021; Patros et al., Citation2016). The current study aims to establish the correlation between ADHD and procrastination further and examine whether the motivation factors derived from the temporal motivation theory and related to both ADHD and procrastination explain their association. It was hypothesised that the positive association between ADHD symptoms and procrastination would be mediated by lower expectancy, higher task aversiveness, and higher impulsiveness.

Material and methods

Participants

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Seymour Fox School of Education, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem. Ethical approval code 2018C03,42020C0. A convenience sample of N = 202 students from the Hebrew University and adults from the general population was recruited through social media and the university experiment management system (SONA). The only inclusion criterion was age 18–50. Students received course credit for participation through the university experiment management system as acceptable in research involving students.

In order to determine the required sample size, we used a Monte Carlo simulation-based tool for calculating power in path analysis developed by Schoemann et al. (Citation2017). It was found that a sample of 200 participants will be sufficient for detecting the three indirect effects in a three parallel mediation model with a 95% confidence level, a power of .90, expected moderate correlations (r = 0.3) between ADHD symptoms and three motivation factors, and moderate-to-large correlations (r = 0.4) between these variables and procrastination.

Measures

Demographic questionnaire

Participants provided background information on age, gender, marital status, level of education, religiousness, employment, and history of diagnosis of ADHD.

The ADHD Self-Report Scale, version 1.1 (ASRS-V1.1)

The Hebrew version of the ASRS-V1.1 (Kessler et al., Citation2005; Konfortes, Citation2010) was completed as a dimensional measure of ADHD symptoms. A dimensional model of ADHD was adopted for this study, as taxometric and genetic evidence has shown that a dimensional conceptualisation of ADHD has merits for research purposes (Coghill & Sonuga-Barke, Citation2012). The Hebrew version was found to have a reliability of α = .89 (Konfortes, Citation2010). As an ADHD screener, the scale’s sensitivity and specificity were established as 68.4% and 99.6%, respectively (Adler et al., Citation2006). The main score was the average of all items except for item 4 (“When you have a task that requires a lot of thought, how often do you avoid or delay getting started?”) because of the similarity with the definition of procrastination. For secondary analyses, separate mean inattention, hyperactivity, impulsivity, and hyperactivity-impulsivity subscale scores were computed.

The Irrational Procrastination Scale (IPS)

The IPS features nine items measuring the degree of irrational delay. Its English version has yielded a good internal consistency with Cronbach’s α = .91 and correlates with the Pure Procrastination Scale at r = .87, or r = .96, after correcting for attenuation due to unreliability (Steel, Citation2010). The IPS was translated to Hebrew by the translation and back-translation method.

Motivational Diagnostic Test (MDT)

The MDT was built to measure the three factors that can increase the likelihood of procrastination according to the Temporal Motivational Theory: expectancy, task (aversive) value and impulsiveness. It consists of 24 items, each measuring one of the three factors. Example items are “I can overcome difficulties with the necessary effort”, “Work bores me”, and “It takes a lot for me to delay gratification” for expectancy, task value, and impulsiveness, respectively. In a validation study, the reliability of the MDT scales was high, with .83 for expectancy, .84 for value, and .83 for impulsiveness. The results showed that expectancy, value, and impulsiveness accounted for 49% of the variance in the reported procrastination (Steel, Citation2011). The MDT was translated to Hebrew by the translation and back-translation method.

Procedure

Data collection was performed over three months using the online survey system Qualtrics. Participants were directed to a welcome web page, allowing them to select their gender. This page explained the purpose of the study and that participation was anonymous and voluntary and could be stopped at any time. Participants agreed to participate by actively pressing a survey button. Once the survey was started, items on a given page had to be rated before proceeding to the next page. The mean completion time of the survey was 12 min.

Data analyses

Skewness and kurtosis tests were used to assess the normality of the continuous variables. Pearson correlations were calculated to evaluate the relationship between the study variables. The primary analysis examined whether the different scores of the MDT mediated the relation between the mean ASRS and IPS scores. Demographic variables that were correlated with ASRS scores were co-variated. For a secondary analysis, partial correlations were computed to estimate the specific contribution of inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity subscale scores to predicting procrastination after correcting for other subscales.

The direct and indirect effects of the ASRS score on the IPS score were calculated using the multiple mediation approach and the SPSS macro (PROCESS, Model 6) provided by Hayes (Citation2017). The multiple mediation model (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008) involves analyses of the total indirect effect (the aggregate of all the mediators examined) and the specific mediators’ indirect effects. The significance of the indirect effects was tested via a bootstrap analysis (5000 samples), which allows for greater statistical power in multiple mediator analyses. The bootstrap analysis does not assume multivariate normality in the sampling distribution, only that the sample is representative of the population (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). Mediation is demonstrated when the indirect effect is significant (i.e., the 95% bias-corrected confidence interval for the estimated parameter does not contain zero). All analyses were conducted using SPSS 27.0, including an SPSS macro designed for assessing multiple mediation models.

Results

Descriptive statistics

The mean age of the sample was and the majority of the sample consisted of females (71%). Seven per cent of the sample reported having been diagnosed with ADHD. Additional demographics for all participants are reported in .

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

summarises the descriptive statistics of the study variables. Skewness and Kurtosis statistics were within the range of −1.5 to 1.5, and therefore their distribution was considered normal.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics of the study variables.

Correlation analysis

None of the demographic characteristics significantly correlated with the IPS (r = −.01–.07, p 0.3). presents the bivariate correlations between the study variables. The ASRS, IPS, and MDT scores were all interrelated significantly, with most relations in the moderate-to-large size range.

Table 3. Correlations between the study variables.

Regression analysis

Two separate multiple linear regression models were conducted in order to assess the predictive strength of the three dimensions of the temporal motivation theory. In a regression model predicting procrastination, the three predictors together explained 41.6% of the variance in procrastination, F(3, 198) = 47.09, p < .001. Lower expectancy (B = −0.32, p < .001) and higher impulsiveness (B = 0.48, p < .001) predicted higher levels of procrastination, while task aversiveness did not significantly predict procrastination (B = 0.18, p = .13). A second regression model, predicting ADHD revealed that the three predictors explained 45.5% of the variance in ADHD, F(3,198) = 55.07, p < .001. Higher impulsiveness (B = 0.50, p < .001) and task aversiveness (B = 0.13, p = .041) predicted higher ADHD symptoms. Expectancy was not found to significantly predict ADHD (B = −0.07, p = .252).

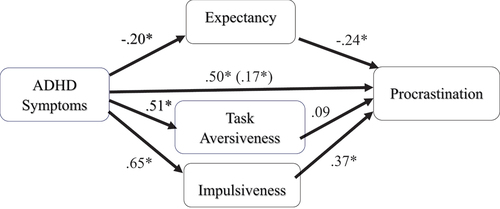

Mediation analysis

The path analysis depicts the direct and indirect effects of ADHD symptoms on procrastination through their effects on expectancy, task aversiveness, and impulsiveness, as they were operationalised in the model (see ). Together the model accounted for 44% (p < .001) of the variance in the level of procrastination. The standardised regression coefficient of ADHD symptoms in predicting procrastination (not considering any mediators) was statistically significant (p < .001). The bootstrapped standardised indirect effects of the pathways mediated by expectancy and impulsiveness were significant. The indirect effect of the pathway mediated by task aversiveness was not significant. shows the coefficients and confidence intervals (CIs).

Figure 1. Indirect and direct pathways from ADHD symptoms to procrastination.

Table 4. Indirect and direct effects of ADHD symptoms upon procrastination.

Secondary analysis

Niermann and Scheres (Citation2014) examined partial correlations between procrastination and the specific clusters of ADHD symptoms, i.e., inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity. They reported that only inattention symptoms correlated with procrastination after correcting for other clusters. To replicate Niermann and Scheres’ findings, we performed the same analyses on the current database. While all subscales scores correlated with the IPS score (see ), only inattention still correlated after controlling for hyperactivity and impulsivity (.543, p < 0.01). Hyperactivity and impulsivity correlated negatively with procrastination after controlling for other subscales, though these correlations did not reach statistical significance (−.128, −.086, and −.037, for hyperactivity-impulsivity, hyperactivity only, and impulsivity only, respectively).

Discussion

Only a few studies focused on the disturbing link between ADHD and procrastination, and even fewer attempted to explain the link. The current study used an online survey to show that (a) adult ADHD symptoms correlated with higher levels of procrastination, and (b) this link was explained by higher delay sensitivity and lower expectancy of completing the task.

ADHD symptoms predict procrastination

It is widely acknowledged among clinicians and educators that ADHD and procrastination are positively correlated (e.g., Ramsay, Citation2020; Safren, Citation2006; Solanto & Scheres, Citation2020); however, it is rarely documented in controlled studies (Altgassen et al., Citation2019; Niermann & Scheres, Citation2014). The current study further suggested that this link exists even after controlling for an overlapping item in the ADHD scale. Furthermore, the study replicated findings concerning the contribution of the different ADHD symptoms clusters and demonstrated that inattention symptoms are the major contributor to the link with procrastination.

ADHD symptoms relate to the motivational factors that promote procrastination

The current study measured the three motivational factors that promote procrastination according to the TMT (Steel, Citation2007): lower expectancy (self-efficacy), greater task aversiveness (boredom), and greater impulsiveness (steeper delay discounting). As predicted by the TMT, it was found that these factors correlated with procrastination, though regression analysis revealed that task aversiveness did not predict procrastination beyond the other two factors. In addition and consistent with previous research, the motivation factors correlated with the level of ADHD symptoms (e.g., Marx et al., Citation2021; Pironti et al., Citation2016; Schmidt-Barad et al., Citation2021).

Mediation analysis revealed two indirect pathways between ADHD and procrastination, the main one through impulsiveness and the other one through low expectancy. These findings suggest that people with high levels of ADHD symptoms procrastinate because they are too impulsive and do not give much weight to future positive outcomes and also because they are less certain about their ability to complete the task satisfactorily and attain the positive outcomes.

Altgassen et al. (Citation2019) found that deficits in everyday prospective memory explained the association between ADHD and procrastination. Forgetfulness and delay sensitivity may both reflect insufficient weight to future outcomes. Future studies may examine whether prospective memory and impulsiveness comprise independent contributions to procrastination or whether they reflect a common mechanism.

Interestingly, despite the role of impulsiveness in mediating the link between ADHD and procrastination, the latter was more related to inattention symptoms than impulsivity (or hyperactivity) symptoms. This finding may highlight the importance of referring to the symptoms’ content rather than their designation. The impulsivity symptoms of ADHD depict social situations in which individuals respond by finishing the sentences of the people they are talking to, not waiting for their turn, and interrupting others. On the other hand, at least some inattention symptoms portray individuals who have problems completing academic and occupational tasks. Examples are difficulties in wrapping up the final details of a project, getting things organised, remembering chores, avoiding careless mistakes and being distracted.

Mediation analysis revealed two indirect pathways, while the indirect effect of the pathway mediated by task aversiveness was not significant. In a first-order correlation analysis, ADHD and task aversiveness were found to have a significant relationship, as did procrastination and task aversiveness. However, the relationship between task aversiveness and procrastination became insignificant when expectancy and impulsiveness were also included in the model. The contribution of task aversiveness in predicting procrastination above and beyond other TMT factors has yet to be examined. The few studies that did examine this question yielded inconsistent results (Steel et al., Citation2022; Wypych et al., Citation2018), possibly due to differences in the statistical power and the analytic approaches employed or in the sampled populations. Future studies should further establish whether task aversiveness has a marginal role in explaining procrastination and its relation to ADHD. According to the present results, the influence of the inherent impulsivity and lack of belief in one’s ability to achieve a goal may be the most influential factors in predicting procrastination. Consequently, they deserve more emphasis in interventions targeting procrastination in general and in the context of ADHD in particular.

Limitations

The findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. First, our sample consisted predominantly of young females, making it hard to assess the generalisability of our findings beyond this population. Second, the convenience sampling method was used. This study also measured ADHD symptoms, motivation, and procrastination only by self-reports and not by family or friends’ reports. There is, however, evidence that adults with ADHD report their symptoms more accurately than their partners (Sandra Kooij et al., Citation2008). In addition, the study was powered to detect indirect effects based on moderate-to-large size correlations with the level of procrastination. A larger sample size may also detect a smaller indirect pathway through task aversiveness.

We used a general population and not a clinical sample for this study. As taxometric and genetic evidence has shown the advantage of a dimensional conceptualisation of ADHD for research purposes, we adopted the continuum of symptoms approach (Coghill & Sonuga-Barke, Citation2012). Consistent with this approach, Wood et al. (Citation2021) found that students who self-reported ADHD symptoms also reported significantly higher rates of all symptom types, impairment, and procrastination than controls, regardless of whether the students had professional diagnoses of ADHD. We also considered that when looking at the difference between individuals diagnosed with ADHD and individuals reporting symptoms consistent with ADHD (based on responses to the ASRS-V1.1), Pawaskar et al. (Citation2020) found that symptomatic respondents have even worse outcomes in measures of work productivity, quality of life, functioning, and self-esteem. However, a study in a clinical population may yield different results. Future research is needed on this topic.

The study employed a cross-sectional design, in which all the variables were measured simultaneously, making it impossible to determine the directions and causal relations between ADHD symptoms and the motivation factors and between these factors and procrastination. Lastly, Steel’s TMT inspired the study, but other theories identify other factors underlying procrastination, e.g., emotion regulation failure (Sirois & Pychyl, Citation2016), which were not addressed in this study.

This study also had several relevant strengths. First, it included students and participants from the general population, and the age range was wide. The survey was relatively short and easy to answer. Aspects of temporal motivation theory were examined in this study in order to determine whether certain aspects of this concept contributed to the findings. Lastly, this study was novel in that no previous studies to our knowledge have investigated expectancy, task’s aversive value, delay and impulsiveness as mediators of the association between ADHD symptoms and procrastination.

Clinical implications

The findings of the study may have clinical implications. As discussed by Steel and Klingsieck (Citation2016), revealing the factors (i.e., impulsiveness) at the core of procrastination informs the treatment of procrastinators is recommended. The current study revealed that individuals with high levels of ADHD symptoms often procrastinate, and that impulsiveness and expectancy explain this association. Therefore, interventions focusing on helping clients to give more weight to the delayed outcomes of the task and perceive task completion as more achievable, are recommended.

To conclude, our findings demonstrate that in an adult sample, ADHD symptoms are related to a higher level of procrastination. ADHD symptoms and procrastination correlated with low expectancy of completing the task, high task aversiveness, and high impulsiveness. Mediation analysis suggested that lower expectancy and higher impulsiveness partially explained the correlation between ADHD and procrastination.

Acknowledgment

The authors want to thank Prof. Adina Maeir from the School of Occupational Therapy, Faculty of Medicine, The Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Hadassah Medical Center for her insightful comments on this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data are not publicly available to ensure participant privacy, but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adler, L. A., Spencer, T., Faraone, S. V., Kessler, R. C., Howes, M. J., Biederman, J., & Secnik, K. (2006). Validity of pilot adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS) to rate adult ADHD symptoms. Annals of Clinical Psychiatry: Official Journal of the American Academy of Clinical Psychiatrists, 18(3), 145–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10401230600801077

- Altgassen, M., Scheres, A., & Edel, M. A. (2019). Prospective memory (partially) mediates the link between ADHD symptoms and procrastination. Attention Deficit and Hyperactivity Disorders, 11(1), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12402-018-0273-x

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596

- Ashworth, B., & Mccown, W. (2018). Trait procrastination, hoarding, and continuous performance attention scores. Current Psychology, 37(2), 454–459. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-017-9696-3

- Coghill, D., & Sonuga-Barke, E. J. (2012). Annual research review: Categories versus dimensions in the classification and conceptualisation of child and adolescent mental disorders–implications of recent empirical study. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 53(5), 469–489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02511.x

- Faraone, S. V., Banaschewski, T., Coghill, D., Zheng, Y., Biederman, J., Bellgrove, M. A., Wang, Y. (2021). The world federation of ADHD international consensus statement: 208 Evidence-based conclusions about the disorder. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, 128, 789–818. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2021.01.022

- Ferrari, J. R., & Sanders, S. E. (2006). Procrastination rates among adults with and without AD/HD: A pilot study. Counseling & Clinical Psychology Journal, 3(1), 2–9.

- Gamst-Klaussen, T., Steel, P., & Svartdal, F. (2019). Procrastination and personal finances: Exploring the roles of planning and financial self-efficacy. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 775. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00775

- Golubchik, P., Manor, I., Shoval, G., & Weizman, A. (2020). Levels of proneness to boredom in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder on and off methylphenidate treatment. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology, 30(3), 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2019.0151

- Hayes, A. F. (2017). Introduction to mediation, moderation, and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach (2nd ed.). Guilford publications.

- Jackson, J. N., & MacKillop, J. (2016). Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and monetary delay discounting: A meta-analysis of case-control studies. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 1(4), 316–325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.01.007

- Kessler, R. C., Adler, L., Ames, M., Demler, O., Faraone, S., Hiripi, E. V. A., & Walters, E. E. (2005). The world health organization adult ADHD Self-Report Scale (ASRS): A short screening scale for use in the general population. Psychological Medicine, 35(2), 245–256.. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0033291704002892

- Kljajic, K., Schellenberg, B. J. I., & Gaudreau, P. (2021). Why do students procrastinate more in some courses than in others and what happens next? Expanding the multilevel perspective on procrastination. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 786249. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.786249

- Konfortes, H. (2010). Diagnosing ADHD in Israeli adults: The psychometric properties of the adult ADHD Self Report Scale (ASRS) in Hebrew. Israel Journal of Psychiatry, 47(4), 308. [ PMID: 21270505]

- Langberg, J. M., Dvorsky, M. R., Molitor, S. J., Bourchtein, E., Eddy, L. D., Smith, Z. R., Oddo, L. E., Eadeh, H. M. (2018). Overcoming the research-to-practice gap: A randomized trial with two brief homework and organization interventions for students with ADHD as implemented by school mental health providers. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(1), 39–55. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000265

- Malkovsky, E., Merrifield, C., Goldberg, Y., & Danckert, J. (2012). Exploring the relationship between boredom and sustained attention. Experimental Brain Research, 221(1), 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-012-3147-z

- Marx, I., Hacker, T., Yu, X., Cortese, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2018). ADHD and the choice of small immediate over larger delayed rewards: A comparative meta-analysis of performance on simple choice-delay and temporal discounting paradigms. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(2), 171–187. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718772138

- Marx, I., Hacker, T., Yu, X., Cortese, S., & Sonuga-Barke, E. (2021). ADHD and the choice of small immediate over larger delayed rewards: A comparative meta-analysis of performance on simple choice-delay and temporal discounting paradigms. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(2), 171–187.

- Metin, U. B., Peeters, M. C. W., & Taris, T. W. (2018). Correlates of procrastination and performance at work: The role of having “good fit”. Journal of Prevention & Intervention in the Community, 46(3), 228–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/10852352.2018.1470187

- Nguyen, B., Steel, P., & Ferrari, J. R. (2013). Procrastination’s impact in the workplace and the workplace’s impact on procrastination. International Journal of Selection and Assessment, 21(4), 388–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsa.12048

- Niermann, H. C., & Scheres, A. (2014). The relation between procrastination and symptoms of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) in undergraduate students. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 23(4), 411–421. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1440

- Patros, C. H., Alderson, R. M., Kasper, L. J., Tarle, S. J., Lea, S. E., & Hudec, K. L. (2016). Choice-impulsivity in children and adolescents with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 43, 162–174. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2015.11.001

- Pawaskar, M., Fridman, M., Grebla, R., & Madhoo, M. (2020). Comparison of quality of life, productivity, functioning and self-esteem in adults diagnosed with ADHD and with symptomatic ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 24(1), 136–144.. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054719841129

- Pironti, V. A., Lai, M. C., Müller, U., Bullmore, E. T., & Sahakian, B. J. (2016). Personality traits in adults with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder and their unaffected first-degree relatives. BJPsych Open, 2(4), 280–285. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjpo.bp.116.003608

- Preacher, K. J., & Hayes, A. F. (2008). Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behavior Research Methods, 40(3), 879–891. https://doi.org/10.3758/brm.40.3.879

- Prevatt, F. (2016). Coaching for college students with ADHD. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(12), 110. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0751-9

- Ramsay, J. R. (2020). Rethinking adult ADHD: Helping clients turn intentions into actions. American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/0000158-000

- Safren, S. A. (2006). Cognitive-behavioral approaches to ADHD treatment in adulthood. The Journal ofClinical Psychiatry, 67(Suppl 8), 46–50.

- Sandra Kooij, J. J., Marije Boonstra, A., Swinkels, S. H. N., Bekker, E. M., de Noord, I., & Buitelaar, J. K. (2008). Reliability, validity, and utility of instruments for self-report and informant report concerning symptoms of ADHD in adult patients. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(4), 445–458. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707299367

- Schmidt-Barad, T., Asheri, S., & Margalit, M. (2021). Memories and self-efficacy among adults with attention deficit disorder symptoms. European Journal of Special Needs Education, 38(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/08856257.2021.2017146

- Schoemann, A. M., Boulton, A. J., & Short, S. D. (2017). Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Social Psychological & Personality Science, 8(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617715068

- Sirois, F. M. (2021). Trait procrastination undermines outcome and efficacy expectancies for achieving health-related possible selves. Current Psychology, 40(8), 3840–3847. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00338-2

- Sirois, F. M., & Pychyl, T. A. (2016). Procrastination, health, and well-being. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-397045-9.00166-X

- Solanto, M. V., Marks, D. J., Mitchell, K. J., Wasserstein, J., & Kofman, M. D. (2008). Development of a new psychosocial treatment for adult ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 11(6), 728–736. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054707305100

- Solanto, M. V., & Scheres, A. (2020). Feasibility, acceptability, and effectiveness of a new cognitive-behavioral intervention for college students with ADHD. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(14), 2068–2082. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054720951865

- Steel, P. (2007). The nature of procrastination: A meta-analytic and theoretical review of quintessential self-regulatory failure. Psychological Bulletin, 133(1), 65–94. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.133.1.65

- Steel, P. (2010). Arousal, avoidant and decisional procrastinators: Do they exist? Personality & Individual Differences, 48(8), 926–934. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2010.02.025

- Steel, P. (2011). A diagnostic measure of procrastination. The 7th Procrastination Research Conference Biennial Meeting, Amsterdam. https://doi.org/10.1037/t10499-000

- Steel, P., & Klingsieck, K. B. (2016). Academic procrastination: Psychological antecedents revisited. Australian Psychologist, 51(1), 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12173

- Steel, P., & König, C. J. (2006). Integrating theories of motivation. Academy of Management Review, 31(4), 889–913. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2006.22527462

- Steel, P., Taras, D., Ponak, A., & Kammeyer-Mueller, J. (2022). Self-regulation of slippery deadlines: The role of procrastination in work performance. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 6278. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.783789

- Ustun, B., Adler, L. A., Rudin, C., Faraone, S. V., Spencer, T. J., Berglund, P., Gruber M. J., Kessler R. C. (2017). The world health organization adult attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder self-report screening scale for DSM-5. JAMA Psychiatry, 74(5), 520–526. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0298

- Wood, W. L. M., Lewandowski, L. J., & Lovett, B. J. (2021). Profiles of diagnosed and undiagnosed college students meeting ADHD symptom criteria. Journal of Attention Disorders, 25(5), 646–656. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054718824991

- Wypych, M., Matuszewski, J., & Dragan, W. Ł. (2018). Roles of impulsivity, motivation, and emotion regulation in procrastination–path analysis and comparison between students and non-students. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 891. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00891

- Young, S., & Myanthi Amarasinghe, J. (2010). Practitioner review: Non-pharmacological treatments for ADHD: A lifespan approach. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 51(2), 116–133. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2009.02191.x