ABSTRACT

Objective

For optimal clinical utility of neuropsychological assessment (NPA), we need to understand what aspects referrers value. We aimed to use quantitative and qualitative methods to evaluate the value of NPA for a diverse range of Australian private practice referrers.

Method

Forty-nine referrers to Australian private neuropsychology practices completed a 25-item online survey evaluating referrer satisfaction, report preferences, barriers to referral, and views on the most beneficial outcome(s) of NPA. Sixteen referrers participated in individual online semi-structured interviews to provide richer accounts of these issues.

Results

Referrers’ survey responses indicated high satisfaction, and that NPA was considered valuable for diagnostic clarification, management planning, and access to support. Participants valued individualised reports with user-friendly explanations of findings and tailored recommendations. Interview data revealed four themes: (1) neuropsychologists possess unique expertise which carries weight amongst referrers and services, (2) neuropsychology enhances understanding of the person and problem, (3) neuropsychology guides healthcare and support, (4) financial, structural, and geographical barriers occur in accessing NPA and implementing supports.

Conclusions

Referrers’ perspectives can inform neuropsychologists’ approach to their work and optimise clinical utility. Future clinical trials should measure the reported useful outcomes of NPA to demonstrate more rigorously the evidence for the value of NPA.

Key Point

What is already known about this topic:

There are barriers to accessing NPA services within Australian youth mental health settings.

Although multiple systematic reviews support the usefulness of NPA, some trials have not, which may relate to outcome measures not reflecting the most valuable outcomes of NPA.

Prior surveys evaluating referrers’ perspectives in the US and Australian youth mental health settings found referrers were satisfied and found NPA useful for treatment planning, diagnostic clarification, and service access.

What this topic adds:

Australian referrers from a diverse range of professional backgrounds are satisfied with NPA services, finding NPA valuable for diagnostic clarification, management planning, and access to support services and funding.

Referrers reported NPA benefited clients’ and families’ understanding of their condition and how to manage it, via comprehensive case formulation and individualised recommendations.

Referrers perceive that neuropsychologists’ unique expertise improves the understanding of the person and presenting problem, which guides healthcare and support. Logistical, financial, and systemic barriers to access of NPA and implementation of recommendations were identified.

Neuropsychology assessments (NPAs) are beneficial for individuals with neurological, psychological, degenerative, and neurodevelopmental conditions, and serve a range of purposes, including clarifying diagnoses, characterising baseline cognitive functioning, guiding management, determining capacity for specific roles, and predicting prognosis (Gruters et al., Citation2021; Harvey, Citation2012). Individuals commonly encounter neuropsychology services after referral from medical practitioners, allied health clinicians, legal service providers, and support coordinators, among others. It is crucial to establish the value of NPA empirically, especially given the unmet need for NPA services (Delagneau, Bowden, van der-el, et al., Citation2021; E. Fisher et al., Citation2022). Systematic reviews support the usefulness of NPA in enhancing diagnostic accuracy and healthcare (Belleville et al., Citation2017; Donders, Citation2020; Watt & Crowe, Citation2018), however, two frequently cited randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (Lincoln et al., Citation2002; McKinney et al., Citation2002), did not find NPA was beneficial for people with multiple sclerosis and stroke. Potential explanations for these discrepancies include trainees conducting the NPA, and the lack of feedback provided to participants (Gruters et al., Citation2022). Perhaps more critically, the outcomes measured may not represent the most valuable outcomes of NPA. Implications from these studies may hinder the utilisation and perception of the profession’s value, emphasising the need for studies that accurately reflect neuropsychology’s impact. Identifying what referrers perceive to be the most useful impacts of NPA is an important step in ensuring future RCTs measure the most appropriate outcomes when appraising neuropsychology’s value.

Neuropsychologists in Australia mainly conduct assessments in the public health system; in rehabilitation hospitals, memory clinics, or psychiatric services (Ponsford, Citation2016). Although the lack of Medicare rebate poses a substantial constraint for private neuropsychologists, a large number of private practitioners work with self-funded clients, such as children with possible neurodevelopmental or learning difficulties, or adult clients referred by private medical practitioners to investigate cognitive changes (Ponsford, Citation2016). This cohort of clients who are ineligible for a public NPA are most impacted by the current lack of subsidisation. Moreover, this financial barrier is particularly likely to affect people from low socioeconomic backgrounds, who are at higher risk for brain conditions (Resende et al., Citation2019). Previous Australian studies of youth mental health services report that NPA would benefit a third of clients, yet only 12% can access it (Allott et al., Citation2019). Additionally, limited accessibility reduces referral rates (Delagneau, Bowden, van der-el, et al., Citation2021). Increasing the understanding of the value of private practice neuropsychology and how barriers impact the provision of optimal care by referrers is crucial. This will inform policymakers and support advocacy for private sector funding.

Past studies investigating referrers’ perceptions of neuropsychology have focused on physicians (public and private) in the US, finding they are highly satisfied with neuropsychological services and perceive them as useful for their practice (Postal et al., Citation2017; Temple et al., Citation2006). Two more US-based studies expanded these findings to include non-medical referrers (Hilsabeck et al., Citation2014; Mahoney et al., Citation2017). Within a Veterans Administration Medical Centre, shorter wait times for the NPA and report, and increased communication with neuropsychologists influenced the perceived value of NPA for referrers (Hilsabeck et al., Citation2014). Mahoney et al. (Citation2017) recruited referrers from a range of professional backgrounds through professional listservs and email lists, finding they appreciated the thoroughness and integration of the NPA, and that they were least comfortable with recommendations for laboratory work, medication, and neuroimaging. In the Australian context, studies of referrers in youth mental health settings report several useful outcomes of NPA, including treatment planning modifications, diagnostic changes, improved clinical assessment, and increased access to services (Allott et al., Citation2011; Delagneau, Bowden, Bryce, et al., Citation2020; C. Fisher et al., Citation2017). It is important to expand these findings within other contexts in Australia.

The neuropsychologist’s report is often the main communication to referrers, so it is important that it is written effectively. Previous studies have reported inconsistencies between how NPA reports are written and what referrers value the most (Postal et al., Citation2017). Referrers found the recommendations and diagnostic impressions most useful, and the history section least useful, consistent with Mahoney et al.’s (Citation2017) study. Hilsabeck et al. (Citation2014) found the length and detail of NPA reports influenced their value for referrers, with the “summary and impressions” section rated as most useful. Further understanding of referrers’ preferences regarding reports is critical to optimise their impact and inform neuropsychologists’ practice.

Past studies examining the value of NPA have primarily used survey methodology, which is useful for capturing common opinions, but does not allow for in-depth exploration of different experiences and novel or nuanced ideas about the value of NPA. One exception analysed qualitative data but focused on a single open-ended question derived from a cross-sectional survey (Delagneau, Bowden, Bryce, et al., Citation2020), limiting in-depth exploration. Qualitative data gleaned from semi-structured interviews provides richer perspectives, and the opportunity to pursue participants’ responses to explore new or unexpected ideas (Nalder et al., Citation2017).

Although existing research provides support for the value of neuropsychology, the perceptions of a professionally diverse range of referrers to private practice neuropsychologists in Australia are important to further understand how best to maximise the utility of NPA. Our objective was to address this gap with an initial survey that aimed to evaluate a) referrers’ satisfaction with NPA services; b) their preferences for the report; c) the barriers they face to referring clients; and d) their views on the most beneficial outcome(s) of neuropsychology. These same topics were then followed up qualitatively through semi-structured interviews to enable a deeper investigation of referrers’ experiences and opinions regarding NPA.

Methods

Participants

This study was approved by the La Trobe University Human Research Ethics Committee (HEC21127). Eligibility criteria comprised of those: a) living in Australia, b) aged 18 years or above, c) had referred at least one client who completed an NPA, and d) identified as a referrer by an Australian private practice neuropsychologist. Recruitment occurred exclusively through private practice neuropsychologists who were contacted via researchers’ professional networks and email listservs to which most Australian neuropsychologists belong (NPinOz; BRAINSPaN). Referrers were recruited during July and August 2021.

Procedure and materials

Participants followed a link in an email received from the neuropsychologist who identified them as a referrer. This link presented the information and consent form, followed by a 25-item online QuestionPro survey (https://www.questionpro.com/au/) (Appendix A). This survey was adapted from previous studies (Allott et al., Citation2011; Mahoney et al., Citation2017; Temple et al., Citation2006) with additional questions suitable for the Australian private practice context. Questions covered: demographic information, how and why responders refer clients for NPA, referrers’ opinions on the neuropsychological report and process, the usefulness of NPA and its outcomes for referrers’ practice and clients. Most responses were indicated on a 4- or 5-point Likert scale with an N/A option to enhance accuracy. Open-ended questions were included to prompt further detail. The survey was piloted with one referrer to ensure it was well-understood, and no changes were required.

On the “Thank you” page after survey completion, participants were invited to fill out an expression of interest for participation in interviews. Interviews were conducted via videoconferencing (Zoom) with a mean length of 35 minutes (standard deviation = 10 minutes). Interviews were conducted by a psychology undergraduate female student (RA) as part of her Honours thesis, and this information was related to participants. RA had no prior relationship with any of the participants. One of the student’s supervisors (DW) (PhD; Clinical Neuropsychologist and experienced qualitative researcher) was also present for the first interview. A 16-question interview guide (Appendix B) was used to expand on the survey questions and obtain richer perspectives from referrers. Comments relevant to the research question were further explored with follow-up questions. Interview audio files were saved and professionally transcribed through “GoTranscript”.

Data analysis

This was a mixed methods cross-sectional observational study consisting of an online survey and videoconference qualitative interviews with a subset of participants. Survey responses were exported into Excel and screened for missing data. Cases with > 50% missing data were excluded. Descriptive statistics were analysed in Excel for the survey questions and were grouped under the following main categories: a) demographic information, b) characteristics of the referral process, c) satisfaction with neuropsychology, d) report preferences, e) barriers to referral and f) NPA’s useful outcomes. Content analysis; a process of identifying and quantifying repeated concepts, was employed for open-ended survey questions (Neuendorf, Citation2017).

Qualitative interview data was analysed using Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-stage approach to reflexive thematic analysis, and followed a data-driven approach within a critical realist framework. Initial codes were created by RA using NVivo (released in March Citation2018), and one interview was cross coded with an independent student researcher. Discrepancies were examined, and edits to the codebook were discussed with the student cross-coder and the research team. A further 20% of the interviews were cross coded, and themes were generated by the research team (KP, DW, and RA). A table of the themes, the key codes that explain them, and examples from the raw data, was developed. Themes were then conceptualised using a figure to describe the relationships between them. An email was sent to all interviewees to confirm that the themes reflected their opinions and experiences. No participants indicated any changes were needed.

Results

Participants

Fifty-eight neuropsychologists were sent a unique survey code to share with their referrers. Of these, 23 neuropsychologists reported sharing the survey with a total of 1,117 referrers. A total of 55 survey responses were received. After excluding those with >50% missing data, the final sample consisted of 49 survey participants, 16 of whom agreed to participate in interviews. As shows, most of the 49 referrers were aged above 40, female, and located in Victoria and New South Wales, with a diverse range of occupations which were also represented in the interview sample ().

Table 1. Survey participants’ demographic information.

Table 2. Interview participants’ occupational information.

Characteristics of the referral process

As shows, most survey participants reported they usually: refer to multiple neuropsychology services (51%), referred a client for NPA “a few times a year” (59.2%), and that clients’ NPA was usually self-funded (44.9%). Good past experience was the most common reason in choosing which neuropsychologist to refer to (87.8%). Diagnostic clarification was the most common reason for referral (79.6%), followed by management recommendations (69.4%), and assessment of cognitive strengths and weaknesses (67.4%).

Table 3. Information about the referral process and measures of referrers’ satisfaction with neuropsychology.

Referrers’ satisfaction with neuropsychology

Approximately 90% of referrers reported their referral question was “usually” or “always” answered satisfactorily and reported being “very likely” to refer a client for NPA again (). Most referrers found the neuropsychologist’s diagnostic impressions “very valuable” (57.1%). Over 90% of referrers were satisfied or very satisfied with the quality of their communication with the neuropsychologist and the length of the report, while over 85% were satisfied or very satisfied with the turnaround time (see ).

How can neuropsychological assessment improve?

Responses to an open-ended question regarding suggested changes to NPA indicated issues with long waitlists and lack of availability, especially in public hospitals and forensic contexts (n = 10). Increasing affordability was considered important (n = 12), with many referrers suggesting Medicare subsidisation (n = 7). Referrers also mentioned requiring more specific guidance for client management (n = 4), faster turnaround times (n = 2), development of multi-cultural norms (n = 1) and telehealth NPA (n = 2), having multidisciplinary clinics that function as a “comprehensive one-stop shop” (n = 2), and the increased recognition of NPA as part of the National Disability Insurance Scheme (NDIS) mainstream service (n = 2). Other points mentioned by one participant each included: greater cultural awareness when working with Indigenous people, improved referral pathways, more consistent provision of feedback sessions, the need for neuropsychologists to focus on and clarify the boundaries of their expertise, and improving the limitations of symptom-based diagnostic criteria.

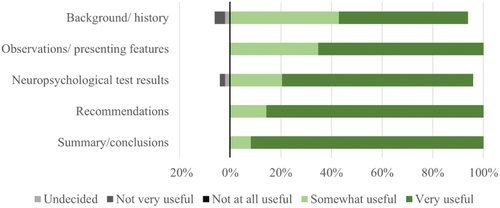

Preferences regarding the report

As demonstrated in , most referrers reported finding all sections of the report to be somewhat or very useful, and most frequently reported the summary/conclusion section to be “very useful”. Regarding the reporting style, most referrers indicated they prefer that the neuropsychologist includes information and recommendations beyond the referral question (71.4%), rather than a concise report focused solely on answering the referral question (28.6%).

Figure 1. Usefulness of neuropsychological report sections for referrers.

During interviews, referrers identified the following features of good reports: 1) accessible and well-organised, 2) detailed and comprehensive, 3) include a summary/conclusion section, 4) include user-friendly explanations of test results, 5) written in a targeted way that addresses the referral question, and 6) specific and concise. These features are detailed further in .

Table 4. Preferences regarding the neuropsychological report as identified in interviews.

Barriers to referring clients for NPA

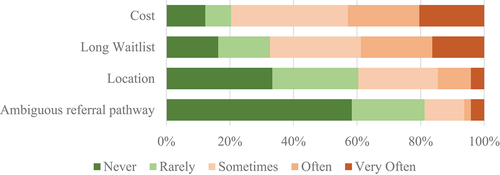

Cost was the most common barrier to referring clients (42.9% indicating encountering this “often” or “very often”), closely followed by long waitlists. represents barriers to referring clients for NPA, with greener blocks indicating the barrier was experienced less often than redder blocks.

Useful outcomes of NPA

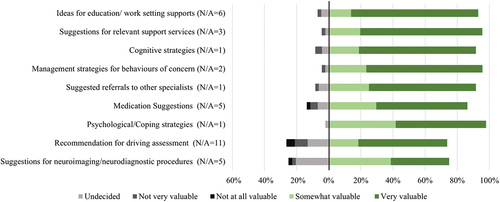

Most referrers (93.9%) indicated they find the NPA and report to be “very useful” or “useful” for their practice. highlights that referrers find almost all types of recommendations somewhat or very valuable. Suggestions for support services and cognitive strategies were most frequently perceived as “very valuable” (over 70%), while suggestions for neurodiagnostic procedures were least frequently rated as “very valuable” (32.7%).

Figure 3. Referrers’ perceived value of different recommendations.

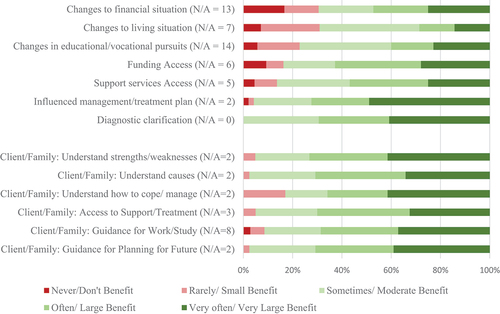

Referrers reported that NPA can lead to a wide range of beneficial outcomes, as evident in . Diagnostic clarification, influence on management plan, access to support services, and access to funding were reported as outcomes occurring often or very often by over 50% of referrers. Most referrers (87.8%) said they usually discuss the NPA results and experience with their clients. Of these, over 60% reported that clients and their families benefit to a large or very large extent from understanding their cognitive strengths and weaknesses and the causes of their presenting problem, improved coping, access to support or treatment, and guidance with planning for their future (see ).

Figure 4. Reported useful outcomes of NPA.

In-depth exploration of referrers’ opinions regarding NPA’s value

Forty codes were generated from thematic analysis of the qualitative interview data. From these, four main themes were generated, representing the value referrers perceive in neuropsychology (). The first theme (neuropsychologists possess unique expertise which carries weight with referrers and services), highlights interviewees’ appreciation of neuropsychologists’ specific expertise, and the impact and influence of NPA reports in legal settings and in enabling access to NDIS and other support services. A subtheme (being in safe hands) refers to how the neuropsychologist’s expertise and approach influences the client’s experience of the NPA process. As one referrer explained; “One of the reasons I keep working with the person I work with is that she’s got a warm, friendly personality, and she’s very good at putting people at their ease” (R5). The second theme (neuropsychology engenders and enhances the understanding of the person and the problem) encapsulates interviewees’ perspective on NPA’s value through its ability to provide a comprehensive case formulation for the referrer and the client, which is a holistic process. One referrer described this process: “’join[ing] the dots’ is where neuropsychologists write a report and finally, we see the picture because the way that they work shows us the history, shows us the current deficits, and gives us the recommendations. That for us is premium”. (R6). The third theme (neuropsychology guides healthcare and support) describes referrers valuing that the NPA empowers the referrer and the client regarding their future healthcare; “recommendations that are really targeted” (R1); “I think it just allowed me to better understand how I approach a client”. (R7). The final theme (barriers in accessing NPA and implementing supports) covered factors that hinder the utilisation of NPA, such as the family’s unwillingness or lack of awareness about NPA, the cost, the unavailability, and inadequate support to implement recommendations. Many interviewees highlighted the significance of reducing access barriers; “a lot of people just fall through the cracks … if it ended up being more accessible, it could be very helpful because you’re going to save yourself a lot of pain and suffering down the track as a society, actually”. (R4)

Table 5. Main Themes generated from interviews.

illustrates the interactions between themes, and how they can be understood in an ordered manner; with neuropsychologists’ unique expertise (1) leading to the understanding of the person and presenting problem (2) which then allows for confident future management (3). The figure also reflects how barriers (4) have an influence on achieving the benefits of neuropsychology throughout, with barriers to accessing NPA at the beginning of the process, followed by barriers to implementing the recommendations of the neuropsychologist, which may inhibit useful outcomes.

Discussion

This mixed-methods study aimed to investigate the value and clinical utility of NPA services from the perspectives of medical and non-medical referrers to neuropsychologists in Australian private practices. Overall, referrers were highly satisfied with NPA, highlighting its value for diagnostic clarification, management planning, and access to support services and funding. Importantly, referrers described benefits to clients and their families’ understanding of their neuropsychological problems and how to manage them with individualised recommendations based on a comprehensive case formulation. They valued recommendations for feasible, relevant cognitive strategies and support services more than recommendations for additional diagnostic investigations (e.g., neuroimaging). Referrers also preferred detailed, targeted reports with user-friendly explanations of findings and recommendations. Four inter-related themes were generated from qualitative interviews, whereby neuropsychologists’ unique expertise (theme 1) leads to enhanced understanding of the person and presenting problem (theme 2). This enhanced understanding guides healthcare and support (theme 3), although logistical, financial, and systemic barriers prevent access to NPA and implementation of recommendations (theme 4). Our findings highlight the unique value that NPA offers referrers, and the need to address access barriers.

Satisfaction with neuropsychology services

Compared to previous studies, fewer referrers in this study reported their referral question was “always” answered to their satisfaction; 30.6% in this study compared to around 60% in two previous studies (Allott et al., Citation2011; Mahoney et al., Citation2017). This may reflect the variety of different neuropsychologists addressing a broader range of referral questions in this survey. Surprisingly, referrers were highly satisfied with report length, compared to 42% reporting it was too long in Mahoney et al. (Citation2017) US-based study. This may indicate a difference in report length between countries, or in referrers’ preferences, as those who refer to private neuropsychologists may be more tolerant of longer reports.

Referrers reported being less satisfied with report turnaround time than other aspects of the NPA process. However, it should be noted that the exceptionally long waitlist for NPA was a more prominent concern than report-writing time, akin to another Australian study (Allott et al., Citation2011). Previous work suggests slow report turnaround times negatively affects patient care, which highlights the importance of ensuring optimal efficiency (Postal et al., Citation2017).

Consistent with previous research (Delagneau, Bowden, Bryce, et al., Citation2020; Howieson, Citation2019; Ponsford, Citation2016), suggested improvements included faster turnaround times, more specific recommendations, multidisciplinary care team integration, and increased client involvement through the direct provision of feedback and continuation of care. Referrers also highlighted the need for telehealth or remote NPA and improvement in assessing people from diverse cultural backgrounds, highlighting important directions for future research into best practice and service development (Hewitt et al., Citation2020; Page et al., Citation2022).

Report preferences

Over 75% of referrers rated the NPA test results as “very useful”, which contrasted with other studies reporting referrers do not strongly value test results (E. Fisher et al., Citation2022; Hilsabeck et al., Citation2014). This may relate to the high number of case managers in the current study, who, as some interviewees indicated, use objective data as evidence to justify supports or funding. Nevertheless, the importance of specific and user-friendly explanations of test results was also emphasised, consistent with past research (Postal et al., Citation2017).

Although it is often recommended that neuropsychological reports are brief and focus exclusively on the referral question (Donders, Citation2016), over 70% of this sample preferred reports that include information and recommendations beyond the referral question. This may be attributable to different approaches to NPA between the US and Australia, with US services being more diagnostic, and less focused on recommendations and management. Consistent with US studies reporting the background section was the least read (e.g., Mahoney et al., Citation2017; Postal et al., Citation2017), this study found this section was least often rated as very useful, likely due to referrers’ adequate familiarity with clients’ history. Nonetheless, referrers mostly indicated finding the background section useful and reading the full report. This suggests referrers to private practice neuropsychologists are more appreciative of a comprehensive report due to the multiple audiences and potential uses for the report. Some interviewees complained of the lack of standardised reporting, while others noted that different framing was critical depending on the purpose (e.g., a report for NDIS focuses on the impact of disability in everyday function, compared to a diagnostic report that focuses on patterns of findings related to various health conditions). Indeed, the importance of targeting reports to the referral question while being specific and concise, yet providing a comprehensive report and a conclusive summary, all arose as important themes in referrers’ reflections on NPA reports. It is important that neuropsychologists are flexible and work collaboratively with regular referrers to determine what is important within each referral context (Baum et al., Citation2018). This may manifest as providing different reports for various stakeholders, as noted by one interviewee, who conveyed gratitude for the neuropsychologist who writes separate reports with appropriate detail and language for the referrer, caregivers, and the child client.

Barriers to accessing neuropsychology

Confirming and expanding on past Australian research within youth mental health, we found that cost and availability pose significant barriers to NPA referrals across settings (Allott et al., Citation2019; Delagneau, Bowden, Bryce, et al., Citation2020). Many referrers mentioned their clients cannot afford private NPA, but public services are often inaccessible due to ineligibility or long waitlists. Subsidising NPA through the Medicare Benefits Schedule would improve accessibility. This has potential long-term benefits, as NPA is associated with cost reductions and economic benefit (Glen et al., Citation2020; Horner et al., Citation2014; Sieg et al., Citation2019; VanKirk et al., Citation2013). As the study’s sample was mostly metropolitan based, location barriers were reported to a lesser extent. Nevertheless, our participants noted the scarcity of neuropsychologists in regional areas, consistent with previous Australian research (Delagneau, Bowden, van der-el, et al., Citation2021). Lack of awareness of NPA was another commonly cited barrier, suggesting that education regarding the process and outcomes of NPA targeted within healthcare and NDIS settings may improve access.

Usefulness of neuropsychology

Referrers reported NPA was highly useful for their practice. The reported outcomes and preferred recommendations were consistent with past research (Mahoney et al., Citation2017; Tremont et al., Citation2002). Referrers expressed they perceived positive outcomes for clients and their families, including understanding their cognitive strengths and weaknesses. Interview data revealed that referrers rely on the unique expertise of neuropsychologists to achieve specific outcomes. Referrers conveyed that, due to this expertise, NPA reports are respected documents that fast-track desirable outcomes. Furthermore, NPA clarifies case formulation and improves the referrer’s, client’s, and family’s understanding of the client. Consistent with previous research, interviewees noted that although the NPA can be distressing for some clients, it often resulted in positive outcomes (Bennett-Levy et al., Citation1994; Gruters et al., Citation2021). This highlights the importance of clients feeling they are “in safe hands” with a neuropsychologist who is warm, and compassionately guides the client through the NPA. Moreover, an enhanced understanding for referrers and clients enables them to manage the presenting problem and move forward with more certainty.

Our results suggest that future RCTs evaluating the impact of neuropsychology should measure the outcomes referrers reported as valuable, i.e.: diagnostic clarity; characterisation of cognitive strengths and weaknesses; cultivating the client and family’s understanding of the presenting problem and how to manage it in their everyday lives; improving the referrer’s confidence in management planning; establishing functional and decision-making capacity; and enabling access to funding, treatment, and support services. Comparing these outcomes between people who have and have not undergone an NPA, as well as comparing the perspectives of their referrers and families will strengthen the current understanding of NPA’s unique utility.

Our findings also have several clinical practice implications regarding neuropsychologists’ approach to their work (such as being flexible and adapting the intensity of the assessment to the client’s needs); efficient and useful report-writing (such as including specific examples of how test results are reflected in the client’s daily functioning); and educational efforts to enhance consumers’ awareness of the service. Implications are summarised in .

Table 6. Clinical implications of the study findings.

Limitations and future directions

This study had several limitations. First, the survey sample was smaller than the target sample size for a representative data set. This may partially be explained by the COVID-19 pandemic and the associated pressures on healthcare workers during the recruitment period. Secondly, although this study aimed to focus on referrers to private neuropsychologists (given the lack of research into this group who have different referral patterns and barriers), many participants had experience referring clients both publicly and privately. It may have been difficult to disentangle these when responding. Positive bias in the sample must also be considered, as neuropsychologists may have selectively shared the study with referrers whom they have a positive relationship. It is also possible that only referrers who appreciate neuropsychology were motivated to respond. Furthermore, since only those who have previously referred were included, this study cannot provide insights into why other professionals do not utilise NPA. Therefore, selection bias is a possibility for both the survey participants and those who chose to be interviewed, as they may have had more experience and passion regarding NPA and the barriers they face. It is important to consider the opinions of those who do not utilise NPA to draw comparisons on the outcomes NPA may impact. Another area currently lacking research is evaluating NPA from clients’ perspectives. Although patient satisfaction surveys have been previously conducted (e.g., Lanca et al., Citation2020; Rosado et al., Citation2018), there is a lack of qualitative research exploring client’s perspectives about the assessment feedback process in the Australian context. Additionally, high quality RCTs measuring key outcomes of NPA are urgently needed.

Conclusion

NPAs in Australian private practice are valuable for a diverse set of referrers, aiding case formulation and confident management planning, and enabling access to vital services and funding. Neuropsychologists are viewed as having unique expertise which is respected by referrers and services, including the legal system and support services. NPAs enhance understanding of the person and their problem – for the referrer, the client, and their family. They also guide healthcare and support. Future studies should develop validated measures of the outcomes referrers identified as most valuable. These can be utilised in future clinical trials to systemically build the evidence base for neuropsychology’s value, and aid advocacy for increased funding to help overcome financial, structural, and geographical barriers to accessing neuropsychology services.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful for the neuropsychologists who shared this study with their referrers and for the participants, both those who completed the survey and those who took time out of their busy schedule to share their ideas and experiences with us in interviews. We would also like to thank Jessie Hill for her help with the coding of the qualitative data. This work was supported by a La Trobe University Tracey Banivanua Mar Fellowship awarded to KP.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, KP. The data are not publicly available due to their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allott, K., Brewer, W., McGorry, P., & Proffitt, T. (2011). Referrers’ perceived utility and outcomes of clinical neuropsychological assessment in an adolescent and young adult public mental health service. Australian Psychologist, 46(1), 15–24. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00002.x

- Allott, K., Van‐der‐el, K., Bryce, S., Hamilton, M., Adams, S., Burgat, L., Killackey, E., & Rickwood, D. (2019). Need for clinical neuropsychological assessment in headspace youth mental health services: A national survey of providers. Australian Journal of Psychology, 71(2), 108–116. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12225

- Baum, K., von Thomsen, C., Elam, M., Murphy, C., Gerstle, M., Austin, C., & Beebe, D. (2018). Communication is key: The utility of a revised neuropsychological report format. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(3), 345–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1413208

- Belleville, S., Fouquet, C., Hudon, C., Zomahoun, H., & Croteau, J. (2017). Neuropsychological measures that predict progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s type dementia in older adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Neuropsychology Review, 27(4), 328–353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-017-9361-5

- Bennett-Levy, J., Klein-Boonschate, M., Batchelor, J., McCarter, R., & Walton, N. (1994). Encounters with Anna Thompson: The consumer’s experience of neuropsychological assessment. Clinical Neuropsychologist, 8(2), 219–238. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854049408401559

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Delagneau, G., Bowden, S., Bryce, S., van‐der‐EL, K., Hamilton, M., Adams, S., Burgat, L., Killackey, E., Rickwood, D., Allott, K. (2020). Thematic analysis of youth mental health providers’ perceptions of neuropsychological assessment services. Early Intervention in Psychiatry, 14(2), 220–227. https://doi.org/10.1111/eip.12876

- Delagneau, G., Bowden, S., van der-el, K., Bryce, S., Hamilton, M., Adams, S., Burgat, L., Killackey, E., Rickwood, D., & Allott, K. (2021). Perceived need for neuropsychological assessment according to geographic location: A survey of Australian youth mental health clinicians. Applied Neuropsychology: Child, 10(2), 123–132. https://doi.org/10.1080/21622965.2019.1624170

- Donders, J. (2016). Neuropsychological report writing (1st ed.). Guilford Publications.

- Donders, J. (2020). The incremental value of neuropsychological assessment: A critical review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(1), 56–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2019.1575471

- Fisher, C., Hetrick, S., Merrett, Z., Parrish, E., & Allott, K. (2017). Neuropsychology and youth mental health in Victoria: The results of a clinical service audit. Australian Psychologist, 52(6), 453–460. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12259

- Fisher, E., Zimak, E., Sherwood, A., & Elias, J. (2022). Outcomes of pediatric neuropsychological services: A systematic review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 36(6), 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1853812

- Glen, T., Hostetter, G., Roebuck-Spencer, T., Garmoe, W., Scott, J., Hilsabeck, R., Arnett, P., & Espe-Pfeifer, P. (2020). Return on investment and value research in neuropsychology: A call to Arms. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 35(5), 459–468. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acaa010

- Gruters, A., Christie, H., Ramakers, I., Verhey, F., Kessels, R., & de Vugt, M. (2021). Neuropsychological assessment and diagnostic disclosure at a memory clinic: A qualitative study of the experiences of patients and their family members. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(8), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1749936

- Gruters, A., Ramakers, I., Verhey, F., Kessels, R., & de Vugt, M. (2022). A scoping review of communicating neuropsychological test results to patients and family members. Neuropsychology Review, 32(2), 294–315. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-021-09507-2

- Harvey, P. D. (2012). Clinical applications of neuropsychological assessment. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 14(1), 91–99. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2012.14.1/pharvey

- Hewitt, K. C., Rodgin, S., Loring, D. W., Pritchard, A. E., & Jacobson, L. A. (2020). Transitioning to telehealth neuropsychology service: Considerations across adult and pediatric care settings. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 34(7–8), 1335–1351. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2020.1811891

- Hilsabeck, R., Hietpas, T., & McCoy, K. (2014). Satisfaction of referring providers with neuropsychological services within a veterans administration medical center. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 29(2), 131–140. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/act084

- Horner, M., VanKirk, K., Dismuke, C., Turner, T., & Muzzy, W. (2014). Inadequate effort on neuropsychological evaluation is associated with increased healthcare utilization. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 28(5), 703–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2014.925143

- Howieson, D. (2019). Current limitations of neuropsychological tests and assessment procedures. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 33(2), 200–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2018.1552762

- Lanca, M., Giuliano, A. J., Sarapas, C., Potter, A. I., Kim, M. S., West, A. L., & Chow, C. M. (2020). Clinical outcomes and satisfaction following neuropsychological assessment for adults: A community hospital prospective quasi-experimental study. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 35(8), 1303–1311. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acz059

- Lincoln, N., Dent, A., Harding, J., Weyman, N., Nicholl, C., Blumhardt, L., & Playford, E. (2002). Evaluation of cognitive assessment and cognitive intervention for people with multiple sclerosis. Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery and Psychiatry, 72(1), 93–98. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.72.1.93

- Mahoney, J., Bajo, S., De Marco, A., Arredondo, B., Hilsabeck, R., & Broshek, D. (2017). Referring providers’ preferences and satisfaction with neuropsychological services. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 32(4), 427–436. https://doi.org/10.1093/arclin/acx007

- McKinney, M., Blake, H., Treece, K., Lincoln, N., Playfordand, E., & Gladman, J. (2002). Evaluation of cognitive assessment in stroke rehabilitation. Clinical Rehabilitation, 16(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1191/0269215502cr479oa

- Nalder, E., Clark, A., Anderson, N., & Dawson, D. (2017). Clinicians’ perceptions of the clinical utility of the multiple errands test for adults with neurological conditions. Neuropsychological Rehabilitation, 27(5), 685–706. https://doi.org/10.1080/09602011.2015.1067628

- Neuendorf, K. (2017). The content analysis guidebook (2nd ed.). SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071802878

- Page, Z. A., Croot, K., Sachdev, P. S., Crawford, J. D., Lam, B. C. P., Brodaty, H., Miller Amberber, A., Numbers, K., & Kochan, N. A. (2022). Comparison of computerised and pencil-and-paper neuropsychological assessments in older culturally and linguistically diverse Australians. Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society, 28(10), 1050–1063. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1355617721001314

- Ponsford, J. (2016). The practice of clinical neuropsychology in Australia. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 30(8), 1179–1192. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2016.1195015

- Postal, K., Chow, C., Jung, S., Erickson-Moreo, K., Geier, F., & Lanca, M. (2017). The stakeholders’ project in neuropsychological report writing: A survey of neuropsychologists’ and referral sources’ views of neuropsychological reports. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(3), 326–344. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1373859

- QSR International Pty Ltd. (2018). NVivo (Version 12). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Resende, E., Llibre Guerra, J., & Miller, B. (2019). Health and socioeconomic inequities as contributors to brain health. JAMA Neurology, 76(6), 633. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2019.0362

- Rosado, D. L., Buehler, S., Botbol-Berman, E., Feigon, M., León, A., Luu, H., Carrión, C., Gonzalez, M., Rao, J., Greif, T., Seidenberg, M., & Pliskin, N. H. (2018). Neuropsychological feedback services improve quality of life and social adjustment. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(3), 422–435. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1400105

- Sieg, E., Mai, Q., Mosti, C., & Brook, M. (2019). The utility of neuropsychological consultation in identifying medical inpatients with suspected cognitive impairment at risk for greater hospital utilization. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 33(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2018.1465124

- Temple, R., Carvalho, J., & Tremont, G. (2006). A national survey of physicians’ use of and satisfaction with neuropsychological services. Archives of Clinical Neuropsychology, 21(5), 371–382. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acn.2006.05.002

- Tremont, G., Westervelt, H., Javorsky, D., Podolanczuk, A., & Stern, R. (2002). Referring physicians’ perceptions of the neuropsychological evaluation: How are we doing? The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 16(4), 551–554. https://doi.org/10.1076/clin.16.4.551.13902

- VanKirk, K., Horner, M., Turner, T., Dismuke, C., & Muzzy, W. (2013). Hospital service utilization is reduced following neuropsychological evaluation in a sample of U.S. veterans. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 27(5), 750–761. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2013.783122

- Watt, S., & Crowe, S. (2018). Examining the beneficial effect of neuropsychological assessment on adult patient outcomes: A systematic review. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 32(3), 368–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2017.1414885

APPENDICES Appendix A

Online Survey:

About You

What is your age?

Under 18

18-24

25-29

30-39

40-49

50-64

65 or above

What is your gender?

Male

Female

Non-binary

Prefer not to say

What is your state of practice?

VIC

NSW

QLD

NT

TAS

SA

WA

ACT

Where is your practice located?

Major city/Metropolitan suburb

Regional City

Rural area

Please select your occupation:

Psychologist

Psychiatrist

General Practitioner

Geriatrician

Neurologist

Rehabilitation Physician

Epileptologist

Allied health clinician (e.g., occupational therapist, speech and language therapist)

Social Worker

Legal service providers

Case Manager

Other (please specify):

Referring for Neuropsychological assessment:

Do you always refer to the same neuropsychology clinic or to multiple services/clinicians?

Usually the same clinic/neuropsychologist

Multiple

Which of the following best describes why you choose to refer to a particular neuropsychologist? Please choose all responses that apply to you:

Recommended by a colleague

Good experience with them in the past

They have the relevant expertise

Institutional affiliation

They charge reasonable fees

They are available/have a quick turnaround

Other

Approximately how often do you refer a client for neuropsychological assessment?

Weekly

Fortnightly

Once a month

A few times a year

Once a year or less often

On average, most of your clients that were referred for a neuropsychology assessment were funded through (please choose all that apply):

Self-funded

Transport accident insurance, e.g., the Transport Accident Commission (TAC) – VIC, NT Motor Accidents Compensation Commission (MACC), Motor Accident Insurance Commission – QLD, Motor Accident Injuries Commission (MAI) – ACT, State Insurance Regulatory Authority (SIRA) – NSW, Motor Accidents Insurance Board (MAIB) – TAS, The Motor Accident Commission (MAC) – SA, Insurance Commission of Western Australia (ICWA) – WA

Workplace insurance

NDIS

Department of Veterans’ Affairs (DVA)

Legal Aid

Other

How often have you encountered the following barriers to referring someone who needs neuropsychological assessment?

Please indicate the most common reason(s) for you to refer someone for neuropsychological assessment (please choose all that apply):

For diagnostic clarification

To establish baseline functioning prior to an intervention/procedure

To assess their cognitive strengths and weaknesses

For guidance/recommendations for management or treatment

To find out if they are eligible for funding or support services

To determine their decision-making capacity

For a medicolegal opinion

Other

Characteristics of the neuropsychology report and process:

On average, how satisfied or dissatisfied are you with the following aspects of the neuropsychology process:

Please indicate the extent to which you find the following sections of the neuropsychology report useful:

Please choose what you prefer in terms of the information included in neuropsychology reports:

That the report is concise and focuses on answering the referral question

That the neuropsychologist includes information, observations, and recommendations beyond the referral question

Please mention any other comments you have on neuropsychology reports (e.g. the style you find most efficient, what parts you find most useful, what you would change):

Usefulness and outcomes of the neuropsychological assessment:

How often is the referral question answered to your satisfaction?

Always

Usually

Sometimes

Rarely

On average, how valuable do you find the following types of recommendations when made in a neuropsychology report:

On average, how useful/valuable do you find the diagnostic impressions made by the neuropsychologist?

Not at all valuable

Not very valuable

Somewhat valuable

Valuable

Very valuable

Overall, how useful do you find the neuropsychological assessment and report to be for your practice in general?

Not at all useful

Not very useful

Somewhat useful

Useful

Very useful

How often has the neuropsychological assessment led to the following outcomes?

How likely are you to refer a client for neuropsychological assessment again in the future?

Very likely

Likely

Somewhat likely

Unlikely

Not at all likely

Do you usually discuss with the client their experience of the neuropsychological assessment?

Yes

No

If yes, to what extent do clients and their family/support people generally appear to benefit from the following:

If you could identify the biggest benefit of neuropsychology, what would it be?

What would you change about neuropsychological assessment services? In your opinion, how can the field of neuropsychology improve?

Please leave any final comments or suggestions you have here:

After you click ‘Done’, you will be invited to join the interview component of this research study. Please read the following page for more information and for the link to sign up!

Thank You Page:

We are also looking for referrers to participate in a short interview to explore your opinions and attitudes about the value of neuropsychology for your practice and how it can be improved.

Interviews will be over Zoom and should not take more than 15 minutes of your time. The Zoom call will be recorded, the video part will be deleted immediately after, while the audio recording will be deleted once it has been transcribed so that your responses cannot be linked to you. Your participation and responses will not affect your relationship with any neuropsychologists you have worked with or the researchers involved in this study.

If you consent to participating in this study, you will be contacted to arrange a suitable date and time for the interview. Please click on this link to provide your details to indicate your willingness to participate:

https://interviewsignup.questionpro.com

We thank you for your time and contribution to this research!

Appendix B

Interview Guide

Referral process:

How do you usually decide to refer a client for neuropsychological assessment?

Can you tell me about the process of referring a client for neuropsychology assessment in your area of practice?

Have you faced any barriers to referring clients? What barriers are these and what do you believe is the cause for these barriers?

What proportion of your clients do you think would benefit from neuropsychological assessment that did not end up being assessed?

Report:

When you receive a neuropsychology report, how do you usually go about reading it? Is there a certain part that you jump to or focus on?

What types of recommendations do you usually find useful in the report?

What gets in the way of implementing those recommendations?

Is there anything you would change about neuropsychology reports or wish was different?

Usefulness and outcomes:

In what ways has the neuropsychology service been useful for your practice and for client care overall? In what ways does the neuropsychologist’s opinion on the client guide your own decision making and confidence when it comes to the client?

Can you tell me about the process of discussing the neuropsychological assessment results with your client? Do you usually give feedback to your client based on the report or do you rely on the neuropsychologist’s feedback to the client?

From your experience, what impact does the neuropsychological assessment have on the client?

From your experience, what impact does the neuropsychological assessment have on the client’s family or loved ones?

How satisfied have you been overall with the outcomes of the neuropsychology assessment in answering your referral questions?

Have you had any negative experiences with any neuropsychology services? In your experience, do you suspect it has ever led to any unhelpful/negative outcomes?

In what ways would you like to see the field of neuropsychology change in the future? Should anything change about the role of neuropsychologists in the future?

Is there anything else you would like to add about the usefulness of neuropsychology?

Note: These questions are a guide only, and any interesting and relevant ideas that emerge during interview will be followed up with additional prompts and questions.