?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Objective

Internalising disorders are one of the most common mental health problems in children under 12 years, yet mixed findings exist for current treatment options. This pilot involves a novel 10-session intervention, BEST-Foundations, to treat internalising symptoms in children using a family-inclusive model. Initial findings and feasibility using a mixed-methods approach are reported.

Method

Twenty-two participants from eight families (n = 8 children; n = 8 mothers; n = 6 fathers) participated in an uncontrolled single treatment design. Included children (aged 3–11 years) reported clinical-level internalising symptoms on the Child Behaviour Checklist. Data were collected across four timepoints: baseline, pre-intervention, post-intervention, and 4-weeks follow-up.

Results

As predicted, mothers reported large improvements in child internalising symptoms pre-post (SMD = −.83; 95% CI = 50.58–70.42) and maintained pre to follow-up (SMD = −.92; 95% CI = 50.14–69.11). Sustained improvements were also found in externalising problems and total problems. Qualitative analysis indicated families reported positive improvements in targeted areas including parent confidence and parent–child relationships.

Conclusions

Findings demonstrate initial feasibility data and effect size estimates comparable to previous trials using the “BEST” framework, and larger than CBT-based interventions. Results are considered preliminary due to the small sample. Further evaluation is warranted, showing the value of family-inclusive interventions to treat child internalising problems.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Modifiable family-based risk and protective factors influence internalising symptoms in children.

Currently, inconclusive support exists for targeted treatment options for child internalising symptoms, highlighting the need to explore novel, feasible, evidence-based approaches for children under 12 years.

Parental involvement in treatment is considerably heterogeneous, and the inclusion of fathers is lacking.

What this topic adds:

The BEST-Foundations intervention translates from theory to practice, demonstrating initial feasibility with families in improving internalising symptoms in children under 12 years.

Fathers may express initial hesitation, yet engaging them in treatment is important.

Parents reported improved confidence and perspective taking after taking part in the BEST-Foundations intervention.

Introduction

Internalising disorders, such as depression and anxiety, are amongst the most prevalent mental health disorders impacting children in Australia. Current rates are consistent with those found internationally (Polanczyk et al., Citation2015) with almost 3% of children under the age of 12 years diagnosed with depression, and nearly one in ten with an anxiety disorder (Lawrence et al., Citation2015). These rates may be conservative due to the internalising nature of these disorders, with symptoms often undiagnosed and untreated. If left untreated, the effects can be pervasive and debilitating, impacting relationships, self-esteem and academic performance and attendance (Lawrence et al., Citation2015). Limited research has disaggregated findings between children and adolescents in relation to interventions aimed to improve internalising disorders. It appears there are missed opportunities for early identification and targeted early intervention, as well as the prevention of further exacerbation of symptoms into adolescence. The current study sought to address this by developing and piloting a novel intervention, BEST-Foundations.

Existing interventions that treat internalising-related symptoms in children under 12 years, commonly target specific anxiety disorders (e.g., social phobia, specific phobias) or treat depression using variations of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), albeit with mixed success. Cognitive theory (the foundation for CBT) proposes that depression occurs through an individual’s negative beliefs about themselves, their experiences and their future, while anxiety disorder occurs as a result of a sense of imposing physical or psychological danger (Beck & Dozois, Citation2011). Metaanalytic findings demonstrate variations of CBT interventions that treat anxiety-related disorders were found to produce small-to-medium effects in children, compared to larger effects for adolescents (Reynolds et al., Citation2012). Meta-analytic findings of CBT-based outcomes to treat depression revealed no significant effects in children under 12 years (Forti-Buratti et al., Citation2016). CBT-based interventions rely on change at an individual level which children at a younger age might not be developmentally equipped for (Reynolds et al., Citation2012) whereas research indicates family-level risk factors are associated with internalising symptoms in children (Kemmis-Riggs et al., Citation2020; Yap & Jorm, Citation2015) including insecure attachment which is largely independent of children’s individual characteristics (Groh et al., Citation2017). While CBT has an established evidence base and is prominent in clinical practice guidelines, empirical support for its effectiveness is less established for children prior to adolescence, highlighting the need to continue to investigate novel treatment approaches (Forti-Buratti et al., Citation2016).

Prior to adolescence, children are embedded more closely in the family system, meaning family-inclusive intervention provides an opportune environment for family-level change (Andershed & Andershed, Citation2015; Drake & Ginsburg, Citation2012; Lewis, Citation2020; Yap & Jorm, Citation2015). Meta-analytic findings suggest that family conflict, child-directed conflict, parental aversive attitudes, lack of warmth, maltreatment and over-control are precursors for the development of depression and internalising symptoms in children under 12 years (Yap & Jorm, Citation2015). More recent population-level Australian longitudinal findings (Kemmis-Riggs et al., Citation2020), found that hostile parenting and a lack of parental self-efficacy were associated with internalising problems in children, however in contrast, parental warmth was not associated with internalising problems in younger children. Further, insecure attachment in the early years is associated with future internalising and externalising problems (Andershed & Andershed, Citation2015). Specifically, metaanalytic findings demonstrate an association between avoidant attachment and internalising and externalising symptoms, and disorganised attachment and externalising symptoms (Groh et al., Citation2017). To summarise, it appears that children with parents that lack confidence utilise more punitive parenting practices, and are more avoidant are at greater risk for mental health problems in childhood.

Despite this, evidence in support of manualised family-inclusive treatment is currently inconclusive (Breinholst et al., Citation2012; Carr, Citation2019; Thulin et al., Citation2014). This may be explained by the diverse ways in which the concept of “parental involvement” is operationalised within existing treatment programs and evaluations (Carr, Citation2019). Parental involvement ranges from psychoeducation about aetiology, involvement as co-clients, training to act as co-therapists, and parent-led contingency management.

Further, the inclusion of fathers in research and programs warrants attention. While contemporary fathers tend to be more involved in everyday parenting, pressures associated with working long hours may limit time and energy spent with their families (Coles et al., Citation2018). Time and financial pressure associated with being the family “breadwinner” may also limit the availability of fathers to be involved in clinical settings, with families typically assuming stereotypical gender-based parenting roles (Coles et al., Citation2018). Further, father involvement appears to lack synthesis and overall coherence within existing programs (Panter‐Brick et al., Citation2014). Findings from a systematic review of 199 studies investigating the inclusion of fathers in treatment found inadequate reporting of the extent of father involvement, pooling mothers’ and fathers’ data into “parent” findings on outcomes, and poor engagement with fathers (Panter‐Brick et al., Citation2014).

The Behavioural Exchange Systems Training (BEST) manualised treatment framework has been applied successfully to adolescent depression and anxiety. As such, it is a promising family-based model to extend into treatment of child internalising symptoms. The BEST framework encompasses several theoretical perspectives including family systems therapy, attachment theory, and elements of cognitive therapy. It was initially designed to help parents with a substance using adolescent and since 1997, has been adapted to include all family members (see Bamberg et al., Citation2008; Bertino et al., Citation2013; Blyth et al., Citation2000; Lewis et al., Citation2013, Citation2015; Poole et al., Citation2017; Toumbourou et al., Citation1997). To date, BEST trials have demonstrated positive change including targeted areas designed to reduce parent and sibling stress, reduce family conflict, increase family communication, improve parental self-care, skills, and confidence, and increase family cohesion.

Most recently, BEST-MOOD was developed to incorporate a stronger focus on parent–child relationships to treat adolescent depression by further incorporating attachment theory and mentalisation (Lewis et al., Citation2013; Poole et al., Citation2017). Quantitative findings from a randomised control trial showed that participating family members benefited, with reductions in adolescent depression (d = .83), and parents’ overall anxiety (d = .35). In qualitative analyses of feedback, participating families reported seeing early signs of depression and/or anxiety in their children, years prior to referral to adolescent services, and specifically requested the development of a similar intervention targeting children under 12 (Lewis et al., Citation2012). These quantitative findings and qualitative consumer feedback informed the motivation to develop and pilot BEST-Foundations.

BEST-Foundations is a 10-session program primarily designed to reduce internalising symptoms in children aged between 3 and 11 years (see ). While the program is manualised, it also includes case formulation for each family and flexible strategies so that clinicians can personalise treatment to suit individual family needs and the developmental level of the child. It is designed with the intention to suit families with different parental set-ups (e.g., single parents, divorced, re-partnered, same sex, etc). Like BEST-MOOD it is informed by attachment theory, mentalisation, family-systems, and psychoeducation. Sessions are designed to target modifiable family-level risk and protective factors. Specifically, to build positive parent–child relationships and interactions, increase capacity for parent and child mentalisation, improve communication, problem solving, and stress management, improve mental health literacy, establish family rituals in line with the families’ vision, improve family cohesion and encourage parental self- care.

Table 1. Theoretical Framework Informing BEST-Foundations Sessions and Activities (adapted from Benstead, Citation2019).

We aimed to explore the feasibility of a novel 10-session intervention, BEST-Foundations, to treat internalising symptoms in children. It was hypothesised that (1) children who participate in the BEST-Foundations intervention will experience statistically significant lower internalising symptoms at the end of the active treatment period, and these improvements will be sustained after a 4-week follow-up. We expected improvements in internalising symptoms of around 0.6–0.8 SMD based on findings from the BEST-MOOD trial (Poole et al., Citation2017); (2) improvements in secondary outcomes (child externalising symptoms/total problems, disorganised caregiving, and parent mental health) will be demonstrated; and (3) participants in the BEST-Foundations program will qualitatively report improvements in positive parent–child interactions, and in parents’ ability to reflect post-intervention, based on previous BEST programs receiving similar positive qualitative evaluations (Lewis et al., Citation2012).

Method

Study design

The study utilised a non-experimental pilot design to test feasibility and determine proof of concept based on recommendations for manualised intervention development (Craig et al., Citation2013). The pilot sought information and data on practicality, acceptability, and effect sizes (Rounsaville et al., Citation2001). A mixed-methods design was utilised, including a repeated-measures analysis to assess quantitative improvements in child internalising symptoms, and qualitative feedback to evaluate feasibility and acceptability. Parent-report data were collected for both primary (child internalising symptoms) and secondary outcomes (e.g., child externalising symptoms, total problems) using the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL). Data were collected on commencement at baseline (baseline), 4 weeks later immediately pre intervention (pre), immediately after the 8-week intervention (post), and at a 4-week follow-up (follow-up). No control group was included as we were interested in establishing a proof of concept before moving to a larger control trial.

Participants

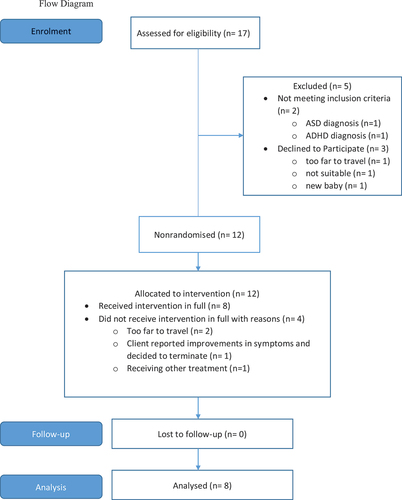

Seventeen families were initially screened for eligibility, with eight families completing the program in full. Reasons for exclusion and attrition are outlined in the TREND diagram (see ). The final sample (N = 22) consisted of five boys and three girls, aged between 3 and 11 years (M = 8.88; SD = 3.14), eight mothers (age: M = 42.75 years, SD = 3.65), and six fathers (age: M = 48.33 years, SD = 6.83). Parents reported being married (n = 4), separated/divorced (n = 3), re-partnered, living in a de-facto relationship (n = 1). Family income ranged from <$20,000 to >$230,000 (Median fell within the $50,000–$80,000 category) per annum. Parent education levels included up to year 10 (n = 4), up to year 12 (n = 1), TAFE/Diploma (n = 2), Undergraduate degree (n = 5), Postgraduate degree (n = 2).

Measures

Child screening

Preschool Mood Scale (PMS)

The PMS is a composite measure combining items from two validated measures: the Preschool Feelings Checklist (PFC; Luby et al., Citation2004) and the Pre-school Anxiety Scale (PAS; Edwards et al., Citation2010). The PFC has 16-item and is a parent-report measure identifying the presence or absence of major depressive disorder (MDD) symptoms in children. It is derived from the PAS which is a 24-item parent-report measure used to identify symptoms of generalised anxiety (GAD), social anxiety (SA), separation anxiety (SEP) and specific fears (SF) in children, and rate stressful life events (past 12 months) on a 5-point Likert scale. Cut-off points were used to initially screen for elevated symptoms: MDD > 3.00; SA > 9.26; SF > 12.91; SEP > 8.24; GAD > 9.20. The scale had excellent internal consistency (α = .90).

Child outcomes

Child Behaviour Checklist (CBCL; 1.5–5 years; 6–18 years)

(Achenbach & Rescorla, Citation2000, Citation2001): The CBCL is a parent-report measure for common child behaviour and adjustment problems. It is scored across three broad categories: internalising symptoms, externalising symptoms, and total problems. Normalised T-scores determine the clinical cut-point of 64, and a sub-clinical score between 60 and 63. Parents rate children’s behavioural and emotional problems (past 2 months) using a 3-point scale. The CBCL 1.5–5 consists of 100 items and the CBCL 6–18 consists of 118 items. For the purpose of the current study, internalising symptoms were the primary outcome, and externalising symptoms and total problems were considered secondary outcomes. Cronbach’s alpha was unable to be determined for the CBCL 1.5–5 due to an N = 2. The CBCL 6–18 had good internal consistency (α = .80).

Secondary parent outcomes

Child Helplessness Questionnaire

(CHQ; George & Solomon, Citation2010) The CHQ is a 19-item measure designed to assess disorganised caregiving. Caregivers self-rate feelings of helplessness, frightened or frightening behaviour, and caregiving-related behaviours on a 5-point Likert scale. Score on the helplessness subscale range from 7 to 35, and the remaining subscales scores range from 6 to 30. The scale had acceptable internal consistency (α = .76)

Edinburgh Depression Scale

(EDS) (Cox et al., Citation1987) is a 10-item self-report scale used primarily to assess post-natal depression in women. Items are rated on a 4-point scale and assess how they have felt over the previous week (minimum to maximum score is 0–30). It has been validated as a measure of depression for populations other than perinatal women including in women with older children (Cox et al., Citation1996), and fathers (Matthey et al., Citation2001). The scale had poor internal consistency (α = .42)

State-Trait Anxiety Inventory

(STAI; Spielberger et al., Citation1983): The STAI is a 40-item self-report questionnaire for adults consisting of 20 items assessing trait-based anxiety symptoms (STAI-T) and 20 items assessing state-based anxiety symptoms (STAI-S) in parents. All items are rated on a 4-point Likert scale and scores range from 20 to 80. The STAI scale had excellent internal consistency (α = .98)

Qualitative interview

A semi-structured “follow-up interview” with 14 base questions (see Supplementary file) was conducted in the final session to gain an in-depth understanding of families’ experiences and feedback about the intervention. All family members were present and encouraged to contribute to the discussion. Example questions: “How do your initial expectations relate to how or what was delivered in the program?”; “Were there any aspects of the program that you found particularly challenging or difficult?”.

Procedure

Ethics approval was received from the Deakin University Human Research Ethics Committee (DUHREC) on 5 February 2015 (Ref: 2014–227). Families were primarily recruited through the intake team of a not-for-profit community service organisation, Drummond Street Services (DS). Intake staff were provided with a script outlining the program and requirements for the study involvement. Further, advertising was also provided through the distribution of leaflets at DS, and an online blog on the University’s online platform. An initial screening was conducted by intake staff at DS to identify children with elevated scores on the PMS, and those that were invited to participate. Parents who expressed interest were contacted by the research team. An initial session was booked with the research team, and parents were sent a copy of the questionnaire. The CBCL was used to establish caseness (i.e., a minimum of sub-clinical internalising symptom scores). Informed consent was obtained by both parents where possible. Parents completed questionnaires at 4 timepoints: baseline, pre, post, and follow-up.

Families attended the BEST-Foundations sessions on a weekly basis. If families were unable to attend a session, the session was rescheduled. The first four families completed the sessions at Deakin University (DU), and the remaining four families completed sessions at DS. The manual was developed by senior clinical psychologist AL, and MB, and documented by MB. Training was conducted by AL and MB. All sessions were facilitated by MB and an additional co-facilitator (one doctoral clinical psychology level student, one registered counsellor, and four family therapists). Clinical guidance and supervision were provided by AL at DU (n = 4), and a senior child and family practitioner at DS (n = 4). All sessions were video-recorded and transcribed verbatim by MB. De-identified data were used in analysis and reporting.

Data analysis

To test hypotheses 1 and 2, all quantitative data were entered into an SPSS file (IBM Corp. Version 23.0) for analysis. The statistical analysis for this study consisted of assessing change across the four time points using a repeated measures ANOVA. No change in primary or secondary outcomes was expected between baseline and pre- intervention (no-treatment period), while reductions were expected pre-post (active treatment period) and sustained at follow-up. A series of within-subject repeated measures ANOVA analyses were conducted to determine change, significant at p < .05. Mauchly’s test for Sphericity was checked for significance, and in cases where p > .05Sphericity was assumed. In cases where Sphericity was p < .05, the Greenhouse-Geisser correction was applied to adjust the degrees of freedom. In cases where the results reached significance at p < .05, post hoc pairwise comparisons using the Bonferroni correction were examined to assess significant reported difference in measures across time-points.

To test hypothesis 3, qualitative data obtained from the follow-up interview was analysed using a reflexive thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). This involved a 6-step process, in which two members of the research team MB and TK immersed themselves in the data. MB was involved in the development of the program, delivery of sessions, collection of data, and transcription process. TK was blinded to the session content and was not involved in the delivery of the program and was consulted due to her expertise in qualitative analysis. Data were independently coded, collated, and findings were discussed. Overarching themes were generated and refined, and then defined and named. Finally, themes were contextualised in an analytic narrative. A deductive approach to analysis was taken with the researchers approaching the data using an attachment and mentalisation-informed lens. While no themes were pre-determined, the researchers drew from prior knowledge of attachment theory and mentalisation, including concepts such as parental reflective capacity, child–parent interactions, attachment security, and parental sensitivity when coding.

Results

Of the 13 recruited families eligible to participate, eight completed treatment in full (refer to TREND diagram in for reasons families declined to participate). There were no drop-outs at follow-up; however, one father came to one session and did not return.

Initial screening on the PMS revealed that all children presented with elevated symptoms of major depressive disorder (n = 8), and at least one of the anxiety subscales (SA (n = 4), SF (n = 5), SEP (n = 2), and GAD (n = 4)). At baseline, all children also scored above the clinical cut-off on the internalising symptoms subscale on the CBCL (n = 8) indicating caseness.

Primary outcome: child internalising symptoms

As expected, there was little change in mother-reported internalising during the no- treatment period from baseline to pre-intervention (p = 1.00). As hypothesised, mother reported internalising improved from baseline (M = 69.75, SD = 9.63) to follow-up (time point 4) (M = 59.63, SD = 11.35; F(3, 21) = 10.93, p < .001). Pairwise comparison revealed a significant reduction in mother-reported internalising from baseline to follow-up (Mdiff = 10.13, p = .02), and from pre to follow-up (Mdiff = 8.63, p = .02). Reductions in internalising of 1.05 standard deviations from baseline to follow-up were observed.

Child secondary outcomes: externalising symptoms and total problems

As expected, there was little change from baseline to pre-intervention in externalising symptoms (p = 1.00), or total problems (p = .44). Significant reductions in externalising symptoms were found from baseline (M = 65.63, SD = 10.78) to follow-up (M = 57.13, SD = 11.14), F(3, 21) = 8.88, p = .001. Pairwise comparison revealed a significant mean difference of 8.50 (p = .01). Reductions in externalising symptoms of 0.79 standard deviations were demonstrated. Furthermore, significant reductions in total problems were demonstrated from baseline (M = 62.88, SD = 16.22) to follow-up (M = 53.25, SD = 16.20), F(3, 21) = 19.13, p < .001. Pairwise comparisons revealed a significant reduction in mean difference (Mdiff) total problems for each subsequent wave: From baseline to post (Mdiff = 7.25, p = .03), baseline to follow-up (Mdiff = 9.63, p = .002), and from pre to follow-up (Mdiff = 8.25, p = .01). Reductions in total problems of −0.59 standard deviations were demonstrated.

Parent secondary outcomes: disorganised caregiving and mental health

As anticipated, there was little change in scores from baseline to pre in disorganised caregiving (p = 1.00). Non-significant reductions on the mother-reported frightening/frightened behaviour subscale was found from baseline (M = 11.88, SD = 5.17) to post (M = 9.25, SD = 4.83), F(1.49, 10.40) = 3.35, p = .09. Pairwise comparison revealed a significant mean difference between baseline and post of 2.63 (p = .05). Reductions in mother frightened/frightening behaviour of −.44 standard deviations were observed.

Reductions in fathers frightened/frightening behaviour from baseline (M = 14.83, SD = 1.72) to follow-up (M = 6.50, SD = .84), F(3, 15) = 3.44, p = .04 were observed. Post-hoc pairwise comparisons revealed no significant mean differences across the four timepoints.

A non-significant increase of almost half a standard deviation in mother self-reported state-anxiety was found between pre and post, returning to just below baseline at follow-up. A non-significant decrease of nearly three-quarters of a standard deviation in father-reported depression was found from baseline to post, returning to baseline levels at follow-up.

Changes in mean scores and standard deviations across the four time points for primary and secondary outcomes are presented in . No significant changes were demonstrated in the non-treatment period (baseline-pre). Significant mother-reported improvements were found in child internalising symptoms, externalising symptoms and total problems after completing the BEST-Foundations intervention.

Table 2. Descriptive summaries, within-group effect sizes of the parent-reported outcomes across four time points.

Feasibility of BEST-Foundations

The feedback received from families was largely positive and highlighted the feasibility of the BEST-Foundations intervention as an acceptable treatment model for families. Four overarching themes were generated using a deductive approach including “Nurturing parental reflection”; “Filling up the toolkit: Boosting parental confidence”; “Prioritising new practices takes time”; “Assessing feasibility: Expectations, experiences and engagement”. Themes are outlined below, and relevant quotes are presented in .

Table 3. Generated themes and relevant quotes.

Theme 1: nurturing parental reflection

The majority of parents reported increases in being aware of how their own emotions impacted their children and described becoming more consciously aware of how they responded to their children. Rather than impulsively reacting, a new self-care approach was adopted involving stopping and breathing and taking time to think before reacting or responding to their child’s behaviour. This greater awareness extended to being able to pick up on the child’s emotional and behavioural cues. Parents reported being more inclined to give the child space to calm down, or provide support when the child was stressed, and approach the situation with greater empathy.

Theme 2: ‘filling up the toolkit’: boosting parental confidence

Parents reported understanding that the program aimed to improve communication and strengthen familial relationships and cohesiveness. Overall, “special time” (characterised by at least 10 min of quality child-centred parent–child time), and increased family time appeared to be the most popular activity suggested, for both parents and children. One parent described the interaction during special time felt natural and not forced, suggesting that the parent–child interactions were positive. Parents who were in a

relationship reported learning to form a united front, which was an aspect targeted by the program that aimed to improve parents’ communication and problem-solving skills.

Theme 3: prioritising new practices takes time

Finding time to engage in self-care and “special time” with children was difficult for some families, and particularly when competing stressors occurred. For example, moving house or having another family member experience a difficult time, meant that parents were less likely to prioritise taking care of themselves or to engage in “special time” with children. All parents described making progress, yet admitted there was still work to be done.

Theme 4: assessing feasibility: expectations, experiences, and engagement

Most parents reported experiencing initial feelings of hopelessness, and beliefs that things could not improve. Almost all the parents stated they did not have initial expectations of the program; however, several admitted feeling quite cynical and not believing it would be helpful. While fathers mostly reported coming along because their partners had told them to, at completion, all the participating fathers reported the overall experience was positive with one father mentioning that it “exceeded his initial expectations”.

There was an overwhelmingly positive response to the hands-on, whole-of-family, approach taken. It appeared parents became more aware of the importance of family cohesion and building positive relationships with all family members. Children detailed they were unsure of what to expect, and anticipated more talking would be involved. One child reported feeling more “grown-up” after taking part and felt their parents heard their requests better now. Another child expected there to be more homework, and one voiced not expecting activities but had enjoyed engaging in them.

Expectations may have been influenced by previous experiences in therapy, and families stated they enjoyed the family-inclusive setting. One parent described previous therapy as being too child-focused, not practical and felt like it was “done in a vacuum”.

Another family had sought family counselling previously, yet felt it was difficult for the psychologist to “elicit much response” from each of the family members as they were always in the room together.

All of the parents described BEST-Foundations as being engaging, useful and would recommend the program to others. One parent stated that the way the program was devised was “particularly useful” in that it was designed “to help parents help their children”. The structure and format were suggested as mechanisms that enabled everyone to be heard, thus improving communication. One parent stated that by including the whole family, everyone benefitted and were all more reflective as a result.

Children offered mixed responses relating to engagement, with one suggesting it was tiring coming on a weekly basis. Yet overall, most children, including siblings, reported being excited to come along.

How BEST-Foundations may be improved

One of the first families to participate suggested a program overview, which was subsequently introduced. Two fathers suggested that fathers should initially be made more aware that they would receive assistance to improve the situation. Separated families expressed finding the family-inclusive environment “a little challenging”. In cases where parents are separated, it was suggested that the other parent be called ahead of time to discuss the content in more detail.

All parents stated that the evaluation questionnaires were quite “challenging”, “repetitive”, and “arduous”, yet despite this, they were also described as “thought-provoking” and “assisted with reflection”.

Discussion

The aim of the current study was to evaluate the initial feasibility of the newly developed and novel program, BEST-Foundations. Primarily, we were interested in whether it was able to reduce clinical levels of internalising symptoms in clinic-referred children aged 3–11 years. As expected, no significant change was found between baseline and pre- intervention for included outcomes demonstrating stability over a 4 week no treatment period. As hypothesised, children demonstrated significant reductions in internalising symptoms after participating in the BEST-Foundations, and of note, further reductions at the 4-week follow-up. The observed reductions in internalising symptoms from baseline to follow-up were 1.05 standard deviations which was above our predicted estimate of 0.6–0.8 standard deviations based on findings from BEST-Mood (Poole et al., Citation2017).

Our second hypothesis was partially supported. Anticipated significant reductions in child externalising symptoms and total problems were demonstrated after participating in BEST- Foundations. Contrary to predictions, no significant improvement was found in parent mental health outcomes. Significant mean differences were found in disorganised caregiving, specifically mother frightened/frightening behaviours.

In line with our third hypothesis, BEST-Foundations appeared acceptable to families. As found in previous BEST trials (Poole et al., Citation2017), most recruited families completed the program in full. Early feasibility trials can determine the ability to recruit, which can be challenging when working with at-risk families in clinical settings (Rounsaville et al., Citation2001). All the families that completed the program overwhelmingly offered positive feedback. Qualitatively, families reported positive parent–child interactions post-intervention (as targeted by activities such as “special time”), and all liked the family-inclusive approach. Improvements in parents’ ability to reflect post-intervention was supported both quantitatively and qualitatively.

For instance, reductions in features of the caregiving system targeted by the intervention and thought to be associated with insecure attachment were observed in both mothers and fathers as reported by the Child Helplessness Questionnaire. Specifically, improvements of almost half a standard deviation were found for mothers’ frightened or frightening behaviour. The overall results did not reach significance, yet a significant post- hoc pairwise comparison was found from baseline to post-intervention. For fathers, an overall significance was found for frightened or frightening behaviour, yet no significant post- hoc comparisons were observed. It is possible that these findings could be explained by the small sample as it had low statistical power to detect small differences.

The mixed findings on parent frightened or frightening behaviour may be partially explained by drawing globally upon the qualitative findings. At follow-up parents reported feeling more in control and confident when responding to their child in situations of heightened emotion. Research suggests that parents approaching situations in a consistent and predictable manner avoid negatively activating the attachment system (Fonagy et al., Citation1998; Slade, Citation2005). Parents also reported being more conscious of how they personally influence a situation, had greater awareness of their child’s emotional and behavioural cues, and took more time before responding, rather than reacting. This is suggestive of parents’ improved capacity for mentalisation, one of the theoretical underpinnings of BEST-Foundations. According to Fonagy et al. (Citation1998), children’s actions and behaviours are more predictable to parents with an enhanced ability to engage in greater reflective functioning associated with the capacity to mentalise. Our findings align with previous research demonstrating that improved child-focused parental reflective functioning promotes child attachment and assists in improving internalising symptoms (Borelli et al., Citation2016).

The findings provide further support for the notion that family-level factors associated with more confident parenting and less hostile and more secure approaches to parenting, may be a protective factor against child internalising problems (Andershed & Andershed, Citation2015; Groh et al., Citation2017, Kemmis-Riggs et al., Citation2020; Yap & Jorm, Citation2015) and may extend to the findings relating to externalising symptoms (Groh et al., Citation2017). While not the primary focus of the intervention, reductions in externalising symptoms provide us with some confidence that the program is targeting common underlying constructs between internalising and externalising in the children (e.g., emotion dysregulation, irritability).

When examining patterns in the data, some interesting findings in relation to parent helplessness warrant attention. For mothers, quantitative scores increased between baseline and pre-intervention and while scores decreased over time, they remained slightly higher at follow-up than initial baseline. For fathers, the pattern in quantitative findings decreased steadily from baseline to follow-up. This was supported by qualitative reports in which parents reported feeling more hopelessness and cynical about improvement to begin with. Given mothers were the one to make initial contact and were involved in the initial sessions with their child, it is likely that this may have impacted their experience. Further, parents became more aware of how their expressions of emotions impacted their children so may have had a heightened sense of awareness. That said, fathers were more likely to report feeling like they had “filled their toolkit” when dealing with their child’s behaviour. Similar findings in relation to parental helplessness have been found in parents seeking mental health services for young children (Ofonedu et al., Citation2017) suggesting that improved strategies to support, particularly around parents’ early engagement is warranted.

The overall aim was to examine the initial feasibility in line with best practice guidelines (Craig et al., Citation2013; Rounsaville et al., Citation2001). An important consideration for future is to examine parental mental health more closely. The current study did not identify improvements in parent mental health as found in previous trials (Bertino et al., Citation2013; Poole et al., Citation2017; Toumbourou et al., Citation2001). On admission to our study, mothers’ mean scores for depression were elevated, yet not in the clinical range, and mean scores for anxiety were higher by approximately one standard deviation compared to an Australian normative sample (Crawford et al., Citation2011). While no improvements were found post-intervention, BEST-Foundations was not specifically designed to treat parental mental health. Rather, the focus of the intervention is on reducing parent stress and interpersonal conflict and boosting parental confidence.

A further consideration when comparing to the BEST-MOOD trials is that parents reported moderate depressive symptoms and mild stress level pre-treatment (Poole et al., Citation2017). Given that adolescent depression is often associated with higher levels of suicidal ideation which would be a concern for parents, it is reasonable that when this subsides, parents’ mental health also improves. That said, the scale utilised in the current study to measure depression had poor internal consistency which more than likely impacted the ability to confidently interpret these findings. To address this, future trials should ensure well-validated measures are used to measure parental mental health more broadly.

There are several key strengths associated with the current study. First, initial findings show good potential to translate well from research to practice. This was demonstrated by the program being delivered across multiple sites, including a family service organisation, with several trained practitioners. A second strength was the mixed-methods design. The inclusion of the qualitative data provided very important additional insights into the consumer experience as well as an opportunity to examine the program logic. A further strength is that we followed the best practice guidelines for developing a novel, complex intervention (Craig et al., Citation2013). This has enabled us to refine the program, consider consumer feedback, reassess included measures, and work towards determining the program logic. Finally, it has also provided an estimation of likely effect size essential for further larger subsequent trials.

We acknowledge that the study is limited by the small sample size, absence of randomisation to a control, and short follow-up period. That said, it does provide initial feasibility required as a preliminary to a randomised controlled trial (RCT; Craig et al., Citation2013). To determine efficacy and control for the noted limitations, and adequately powered RCT, with a diverse sample should be conducted with a longer follow-up period. Practitioner feedback and fidelity should also be considered where dissemination into family service practice occurs (Craig et al., Citation2013), and a more strongly validated measure of parental mental health is needed.

To conclude, this paper has outlined the initial feasibility evaluation of a novel intervention, BEST-Foundations, developed to treat internalising symptoms in children. Significant reductions in internalising symptoms, externalising symptoms and total problems were observed. Overall, families reported changes in theoretically targeted domains and appeared highly acceptable based on consumer feedback. These preliminary findings provide evidence in support of further development of family interventions in the treatment of child mental health problems such as internalising and externalising symptoms. Specifically, BEST-Foundations shows promise and further evaluation using an RCT design to determine efficacy is warranted.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (19.4 KB)Acknowledgements

This paper summarises research reported in Michelle L. Benstead’s thesis. Michelle Benstead was the recipient of an Australian Rotary Health Youth Mental Health scholarship for her PhD. Michelle would like to express gratitude to the Rotary Club of Richmond in conjunction with Motto Fashions, and Deakin University for their financial assistance. The authors would also like to thank the staff at Drummond Street Services for their contribution, as well as Deakin students Jo Hansen and Claire Joseph.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data are available by contacting Michelle L. Benstead.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2023.2282544.

References

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2000). Manual for the ASEBA preschool forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

- Achenbach, T. M., & Rescorla, L. A. (2001). Manual for the ASEBA school-age forms & profiles. University of Vermont, Research Center for Children, Youth, & Families.

- Andershed, A. K., & Andershed, H. (2015). Risk and protective factors among preschool children: Integrating research and practice. Journal of Evidence-Based Social Work, 12(4), 412–424. https://doi.org/10.1080/15433714.2013.866062

- Bamberg, J., Toumbourou, J., & Marks, R. (2008). Including the siblings of youth substance abusers in a parent-focused intervention: A pilot test of the BEST-Plus program. Journal of Psychoactive Drugs, 40(3), 281–291. https://doi.org/10.1080/02791072.2008.10400643

- Beck, A. T., & Dozois, D. J. (2011). Cognitive therapy: Current status and future directions. Annual Review of Medicine, 62(1), 397–409. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-med-052209-100032

- Benstead, M. L. (2019). BEST-Foundations: A family-focused Attachment-based intervention treating emotional disorders in children. Deakin University.

- Bertino, M., Richens, K., Knight, T., Toumbourou, J., Ricciardelli, L., & Lewis, A. (2013). Reducing parental anxiety using a family based intervention for youth mental health: A randomized controlled trial. Open Journal of Psychiatry, 3(1), 173–185. https://doi.org/10.4236/ojpsych.2013.31A013

- Blyth, A., Bamberg, J., & Toumbourou, J. (2000). BEST. Behaviour exchange systems training: A program for parents stressed by adolescent substance abuse. ACER Press.

- Borelli, J. L., St John, H. K., Cho, E., & Suchman, N. E. (2016). Reflective functioning in parents of school-aged children. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 86(1), 24. https://doi.org/10.1037/ort0000141

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Breinholst, S., Esbjørn, B. H., Reinholdt-Dunne, M. L., & Stallard, P. (2012). CBT for the treatment of child anxiety disorders: A review of why parental involvement has not enhanced outcomes. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 26(3), 416–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2011.12.014

- Buck, J. (1948). The H-T-P technique, a qualitative and quantitative scoring Method. Journal of Clinical Psychology Monograph Supplement No 5, 1–120. https://doi.org/10.1002/1097-4679(194810)4:4<317:aid-jclp2270040402>3.0.co;2-6

- Carr, A. (2019). Family therapy and systemic interventions for child‐focused problems: The current evidence base. Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 153–213. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6427.12226

- Coles, L., Hewitt, B., & Martin, B. (2018). Contemporary fatherhood: Social, demographic and attitudinal factors associated with involved fathering and long work hours. Journal of Sociology, 54(4), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783317739

- Cox, J. L., Chapman, G., Murray, D., & Jones, P. (1996). Validation of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) in non-postnatal women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 39(3), 185–189. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-0327(96)00008-0

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of postnatal depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782

- Craig, P., Dieppe, P., Macintyre, S., Michie, S., Nazareth, I., & Petticrew, M. (2013). Developing and evaluating complex interventions: The new medical research council guidance. British Journal of Medicine, 337, 1655. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.a1655

- Crawford, J., Cayley, C., Lovibond, P. F., Wilson, P. H., & Hartley, C. (2011). Percentile norms and accompanying interval estimates from an Australian general adult population sample for self‐report mood scales (BAI, BDI, CRSD, CES‐D, DASS, DASS‐21, STAI‐X, STAI‐Y, SRDS, and SRAS). Australian Psychologist, 46(1), 3–14. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-9544.2010.00003.x

- Drake, K. L., & Ginsburg, G. S. (2012). Family factors in the development, treatment, and prevention of childhood anxiety disorders. Clinical Child and Family Psychological Review, 15(2), 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-011-0109-0

- Edwards, S. L., Rapee, R. M., Kennedy, S. J., & Spence, S. H. (2010). The assessment of anxiety symptoms in preschool-aged children: The revised preschool anxiety scale. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 39(3), 400–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374411003691701

- Fonagy, P., Target, M., Steele, H., & Steele, M. (1998). Reflective-functioning manual, version 5.0, for application to adult attachment interviews. University College London.

- Forti-Buratti, M. A., Saikia, R., Wilkinson, E. L., & Ramchandani, P. G. (2016). Psychological treatments for depression in pre-adolescent children (12 years and younger): Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 25(10), 1045–1054. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00787-016-0834-5

- George, C., Kaplan, N., & Main, M. (1996). Adult attachment Interview ( 3rd ed.). Unpublished manuscript, Department of Psychology, University of California.

- George, C., & Solomon, J. (2010). Caregiving helplessness: The development of a screening measure for disorganized maternal caregiving. Guilford Publications.

- Green, J., Stanley, C., Smith, V., & Goldwyn, R. (2000). A new method of evaluating attachment representations in young school-age children: The manchester child attachment story task. Attachment & Human Development, 2(1), 48–70. https://doi.org/10.1080/146167300361318

- Groh, A. M., Fearon, R. P., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Bakermans‐Kranenburg, M. J., & Roisman, G. I. (2017). Attachment in the early life course: Meta‐analytic evidence for its role in socioemotional development. Child Development Perspectives, 11(1), 70–76. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12213

- Kemmis-Riggs, J., Grove, R., McAloon, J., & Berle, D. (2020). Early parenting characteristics associated with internalizing symptoms across seven waves of the longitudinal study of Australian children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 48(12), 1603–1615. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-020-00700-0

- Lawrence, D., Johnson, S., Hafekost, J., Boterhoven De Haan, K., Sawyer, M., Ainley, J., & Zubrick, S. R. (2015). The mental health of children and adolescents. Report on the second Australian child and adolescent survey of mental health and wellbeing. Department of Health.

- Lewis, A. J. (2020). Attachment-based family therapy for adolescent substance use: A move to the level of systems. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 10(948). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00948

- Lewis, A. J., Bertino, M. D., Robertson, N., Knight, T., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2012). Consumer feedback following participation in a family-based intervention for youth mental health. Depression Research and Treatment, 2012, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/235646

- Lewis, A., Bertino, M., Skewes, J., Shand, L., Borojevic, N., Knight, T., Lubman, D., & Toumbourou, J. W. (2013). Adolescent depressive disorders and family based interventions in the family options multi-centre evaluation: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials, 14(1), 384. https://doi.org/10.1186/1745-6215-14-384

- Lewis, A. J., Knight, T., Germanov, G., Benstead, M. L., Joseph, C. I., & Poole, L. (2015). The impact on family functioning of social media use by depressed adolescents: A qualitative analysis of the family options study. Frontiers in Psychology, 6(131). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2015.00131

- Luby, J. L., Heffelfinger, A., Koenig McNaught, A. L., Brown, K., & Spitznagel, E. (2004). The preschool feelings checklist: A brief and sensitive screening measure for depression in young children. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(6), 708–717. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.chi.0000121066.29744.08

- Matthey, S., Barnett, B., Kavanagh, D. J., & Howie, P. (2001). Validation of the edinburgh postnatal depression scale for men, and comparison of item endorsement with their partners. Journal of Affective Disorders, 64(2–3), 175–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0165-0327(00)00236-6

- Ofonedu, M. E., Belcher, H. M., Budhathoki, C., & Gross, D. A. (2017). Understanding barriers to initial treatment engagement among underserved families seeking mental health services. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(3), 863–876. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0603-6

- Panter‐Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers–recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(11), 1187–1212. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12280

- Polanczyk, G. V., Salum, G. A., Sugaya, L. S., Caye, A., & Rohde, L. A. (2015). Annual research review: A meta-analysis of the worldwide prevalence of mental disorders in children and adolescents. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 56(3), 345–365. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.12381

- Poole, L., Knight, T., Toumbourou, J. W., Lubman, D., Bertino, M. D., & Lewis, A. J. (2017). A randomized controlled trial of the impact of a family-based adolescent depression intervention on both youth and parent mental health outcomes. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 46(1), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-017-0292-7

- Pyle, N. R. (2006). Therapeutic letters in counselling practice: Client and counsellor experiences. Canadian Journal of Counselling, 40(1), 17–31.

- Reynolds, S., Wilson, C., Austin, J., & Hooper, L. (2012). Effects of psychotherapy for anxiety in children and adolescents: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychological Review, 32(4), 251–262. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2012.01.005

- Rounsaville, B. J., Carroll, K. M., & Onken, L. S. (2001). A stage model of behavioral therapies research: Getting started and moving on from stage I. Clinical Psychology Science & Practice, 8(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.8.2.133

- Shmueli-Goetz, Y. (2001). The child attachment interview: Development and validation [ Doctoral thesis]. University College London.

- Slade, A. (2005). Parental reflective functioning: An introduction. Attachment & Human Development, 7(3), 269–281. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616730500245906

- Spielberger, C., Gorsuch, R., Lushene, R., Vagg, P., & Jacobs, G. (1983). Manual for the state-Trait anxiety Inventory. Consulting Psychologists Press.

- Steele, H., & Steele, M. (2008). Ten clinical uses of the adult attachment interview. In H. Steele & M. Steele (Eds.), Clinical applications of the adult attachment interview (pp. 3–30). Guilford Press. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.054817

- Steele, M., Steele, H., Bate, J., Knafo, H., Kinsey, M., Bonuck, K., Meisner, P., & Murphy, A. (2014). Looking from the outside in: The use of video in attachment-based interventions. Attachment & Human Development, 16(4), 402–415. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616734.2014.912491

- Thulin, U., Svirsky, L., Serlachius, E., Andersson, G., & Öst, L. G. (2014). The effect of parent involvement in the treatment of anxiety disorders in children: A meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 43(3), 185–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2014.923928

- Toumbourou, J. W., Blyth, A., Bamberg, J., & Forer, D. (2001). Early impact of the BEST intervention for parents stressed by adolescent substance abuse. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 11(4), 291–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/casp.632

- Toumbourou, J. W., Blyth, A., & Blyth, A. (1997). Behaviour exchange systems training: The ‘BEST’ approach for parents stressed by adolescent drug problems. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 18(2), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1467-8438.1997.tb00273.x

- Winnicott, D. W. (1971). Therapeutic consultations in child psychiatry. Basic Books.

- Yap, M. B. H., & Jorm, A. F. (2015). Parental factors associated with childhood anxiety, depression, and internalising problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 175, 424–440. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.050

- Zeanah, C. H., & Benoit, D. (1995). Clinical applications of a parent perception interview in infant mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 4(3), 539–554. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1056-4993(18)30418-8