ABSTRACT

Objective

Beliefs about the controllability and usefulness of emotions may influence successful emotion regulation across multiple emotional disorders and could thus be influential mechanisms in long-term mental health outcomes. However, to date there has been little empirical work in this area. Our aim was to fill this gap, by examining the links between emotion beliefs and common emotional disorder symptoms. Specifically, we examined whether emotion beliefs can account for significant variance in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, and explored which profiles of emotion beliefs might characterise each of these symptom categories.

Methods

A sample of 948 Australian university students completed self-report measures of emotion beliefs and emotional disorder symptoms.

Results

A path analysis indicated that emotion beliefs accounted for a modest but significant 11%, 12%, and 9% of the variance in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, respectively (ps < .001). A latent profile analysis revealed six different profiles of combinations of emotion beliefs and emotional disorder symptom levels, collectively reinforcing the transdiagnostic relevance of emotion beliefs across each symptom category.

Conclusions

Overall, our results indicate the importance of considering emotion beliefs in conceptualisations of depression, anxiety, and stress, and suggest that emotion beliefs may be a useful assessment and treatment target.

Key Points

What is already known about this topic:

Ford and Gross’s (2018, 2019) theoretical framework of emotion beliefs posits that believing positive and negative emotions are uncontrollable and useless is detrimental for emotion regulation efforts and mental health outcomes.

Beliefs about emotions being uncontrollable are associated with increased emotional disorder symptoms.

The limited research examining beliefs about the usefulness of emotions indicates that believing emotions are useless is also associated with increased emotional disorder symptoms.

What this topic adds:

This study is the first to comprehensively examine controllability and usefulness beliefs across the negative and positive valence domains.

We systematically mapped the emotion belief profiles characterising depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, and found profiles with stronger maladaptive emotion beliefs tended to have greater emotional disorder symptoms.

We found that both belief categories across both valence domains are relevant to emotional disorder symptoms, but beliefs about the controllability of negative emotion were particularly important.

Introduction

Emotion regulation difficulties that are characteristic of emotional disorders, such as depressive and anxiety disorders (Bullis et al., Citation2019), have important clinical implications for assessment and treatment, yet much remains unknown about the mechanisms underlying emotion dysregulation (Gross & Jazaieri, Citation2014). Preliminary research indicates that emotion beliefs may be a factor that contributes to the maintenance of these disorders, although more research is needed to understand which emotion beliefs are most strongly associated with symptoms (Kneeland et al., Citation2020). Emotion beliefs are beliefs about the nature, meaning, and utility of emotions, which impact how individuals perceive and respond to their emotions, and the emotions of those around them (Ford & Gross, Citation2018).

Beliefs and emotional disorders: theoretical background

Ford and Gross (Citation2018, Citation2019) recently developed a new framework for conceptualising and organising emotion beliefs, based within the widely used process model of emotion regulation (Gross, Citation2015). This framework seeks to explain how emotion beliefs contribute to the development and maintenance of emotional disorders. In particular, Ford and Gross’s (Citation2018) theoretical framework posits two main types of beliefs about emotions relevant to this area: beliefs about the controllability of emotions and beliefs about the usefulness of emotions. The nature of beliefs in these areas can differ along a continuum; from the belief that emotions are completely uncontrollable to completely controllable. Similarly, some people believe emotions have a high degree of utility and value, whereas others consider them to be useless and harmful (Ford & Gross, Citation2018).

Ford and Gross (Citation2018) theorise that controllability beliefs influence whether people attempt to modify their emotional response in a particular context, whilst usefulness beliefs influence the trajectory of emotion regulation (i.e., increasing or decreasing an emotional response) by influencing what people want to feel or not feel. In this way, emotion beliefs are theorised to be powerful determinants of acute emotional responses, which, over time, accumulate to contribute to longer-term emotional health outcomes (Ford & Gross, Citation2019).

Beliefs and emotional disorders: empirical findings

To date, most empirical studies in the field have focused on controllability beliefs and negative emotions, but not usefulness beliefs or positive emotions (for some exceptions, see Becerra et al., Citation2020, Citation2023). Multiple studies using self-report measures have highlighted the importance of controllability beliefs for good mental health, with the belief that emotions are uncontrollable being associated with fewer emotion regulation efforts (Kneeland et al., Citation2016), increased depressive or anxiety symptoms (Deplancke et al., Citation2022; Ford et al., Citation2018; Veilleux, Pollert, et al., Citation2021), increased negative affect (Kneeland et al., Citation2020), more persistent social anxiety disorder symptoms (De Castella et al., Citation2013), decreased wellbeing (De Castella et al., Citation2013; Tamir et al., Citation2007), and increased stress (De Castella et al., Citation2013). The existing body of research on usefulness beliefs, albeit smaller, also indicates that believing emotions are useless or harmful is associated with poorer emotion regulation decisions and more severe emotional disorder symptoms (Ford et al., Citation2018; Manser et al., Citation2012; Veilleux, Chamberlain, et al., Citation2021; Veilleux, Pollert, et al., Citation2021).

In summary, the above findings suggest that controllability and usefulness beliefs may be associated with emotional disorder symptoms. However, there is a gap in understanding how these beliefs function differently across the valence spectrum. Valence is theorised to be a particularly salient category by which individuals organise their emotion beliefs (Ford & Gross, Citation2018), but little work has examined emotion beliefs across both negative and positive emotions. According to Ford and Gross’s (Citation2018) framework, individuals might simultaneously hold distinct beliefs about the usefulness or controllability of negative versus positive emotions, such that one could believe a negative emotion like anger is uncontrollable, whilst also believing a positive emotion like happiness is controllable. Recent psychometric studies utilising the Emotion Beliefs Questionnaire (EBQ; Becerra et al., Citation2020), a measure of controllability and usefulness emotion beliefs, have indeed found the EBQ’s factor structure separates according to valence, indicating statistical value in differentiating between positive and negative emotion beliefs (Becerra et al., Citation2023; Ranjbar et al., Citation2023). Furthermore, given that research in other emotion domains such as emotion regulation has demonstrated that positive and negatively valenced emotions can function differently (Preece et al., Citation2018), it is important to examine how emotion beliefs function across the valence spectrum. Finally, more work is needed to understand the potentially complex interplay between usefulness and controllability beliefs in both the negative and positive emotion space. More specifically, it remains to be seen which configurations of beliefs are more or less related to different symptoms of emotional disorders and what are the unique contributions of each domain of emotion beliefs.

The present study

Our aim in this study was to examine the associations between emotion beliefs and three common types of emotional disorder symptoms (depression, anxiety, and stress). We utilised the EBQ (Becerra et al., Citation2020) to enable a comprehensive and differentiated mapping of the emotion beliefs construct. We conducted a path analysis to examine whether emotion beliefs (i.e., controllability and usefulness beliefs across both valence domains) explained a significant proportion of variance in depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms and determine which emotion beliefs were significantly associated with each symptom category. We additionally used Latent Profile Analysis (LPA) to further explore profiles of emotion beliefs, or combinations of different beliefs, that might uniquely characterise depression, anxiety, and stress symptom categories. Given that the emotion belief field is currently understudied, and this study is exploratory in nature, we decided to not propose any formal hypotheses about how specific emotion beliefs may differentially relate to depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms.

Method

Participants and procedure

Our sample was 948 undergraduate psychology students from an Australian university. They had a mean age of 22.59 years (SD = 6.64, range = 16–56). The majority of participants were female (76.20%), born in Australia (69.62%), and answered yes to a question asking whether they had previously been diagnosed with a mental health disorder at some point in their life (64%). Participants completed a battery of self-report measures as part of a larger online survey using Qualtrics software. Participants received course credit for survey completion.

Measures

Emotion beliefs

The EBQ (Becerra et al., Citation2020) is a 16-item self-report measure of beliefs about emotions based on Ford and Gross’s (Citation2018) theoretical framework. Four subscale scores can be derived, assessing each belief for negative and positive emotions separately: negative-controllability (e.g., “People cannot control their negative emotions”), positive-controllability (e.g., “It doesn’t matter how hard people try, they cannot change their positive emotions”), negative-usefulness (e.g., “People don’t need their negative emotions”), and positive-usefulness (e.g., “Positive emotions are harmful”). Items are rated on a 7-point Likert scale from 1 (“Strongly disagree”) to 7 (“Strongly agree”), with higher scores reflecting stronger beliefs that emotions are uncontrollable and useless (i.e., stronger maladaptive emotion beliefs). The EBQ has previously demonstrated good validity and reliability (e.g., Becerra et al., Citation2020), and had good internal consistency in the current sample across all subscales (Cronbach’s α = .81–.87).

Depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms

The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21; Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995) was used to measure symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress over the past week. The DASS-21 is a 21-item self-report scale answered using a 4-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (“Did not apply to me at all”) to 3 (“Applied to me very much, or most of the time”), with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. Three subscale scores can be derived, including (1) depression (e.g., “I felt I had nothing to look forward to”), (2) anxiety (e.g., “I felt I was close to panic”), and (3) stress (e.g., “I found it hard to wind down”). The DASS-21 has previously demonstrated good validity and reliability (e.g., Osman et al., Citation2012), and had good internal consistency across the subscales (α = .88–.92) in our sample.

Analytic strategy

Correlation matrix and path Analysis

Using IBM SPSS (Version 28) we calculated Pearson’s bivariate correlations to determine the raw associations among the variables. A path analysis was conducted using Mplus (Version 7.4), with the four EBQ subscales as the predictors and the DASS-21 subscales as the criterion variables. The DASS-21 subscales were free to covary. The model was fully saturated, so goodness of fit could not be formally assessed. However, our intention was to estimate the parameters within the model with 95% confidence intervals as an indication of precision. Given that previous studies show significant age and gender differences on DASS-21 scores (e.g., Crawford & Henry, Citation2003), age and gender were included as covariates, to partial out any effects they may have on depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms.

Latent profile analysis

Our LPA was conducted using R software with the TidyLPA package (Rosenberg et al., Citation2018) to explore how different combinations of emotion beliefs might uniquely characterise depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. This analysis thus had seven variables in total: the four emotion belief subscales, plus the symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress subscales. Sample size requirements are currently understudied for LPA; however existing research recommends a minimum sample size of 250 participants (Tein et al., Citation2013). Given this, our sample of 948 participants was adequate.

We tested solutions for one to 10 profiles using the default model type in TidyLPA (equal variances and covariances fixed to zero; Rosenberg et al., Citation2018). We evaluated the fit of each model to determine the optimal solution (i.e., optimal number of profiles to explain the data) according to five common fit index values: the Akaike Information Criterion (AIC), the Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), the Classification Likelihood Criterion (CLC), the Kullback Information Criterion (KIC), and the Appropriate Weight of Evidence Criterion (AWE; Akogul & Erisoglu, Citation2017). Lower values on each index indicates a better fitting model (Tein et al., Citation2013). Each of the five index values were considered, with a particular focus on the BIC, as previous research indicates this is the best performing indicator of optimal profile solutions (Nylund et al., Citation2007). We also considered entropy values, which can range from 0 to 1, where higher scores indicate a better model fit and values above .80 are deemed acceptable (Tein et al., Citation2013). Finally, model solutions were evaluated for generalisability, where profiles containing less than 5% of the sample were considered insubstantial and thus unacceptable within the optimal solution (Ferguson et al., Citation2020).

Results

Correlation matrix and path analysis

The Pearson’s bivariate correlation matrix, descriptive statistics, and reliability statistics are presented in . There were significant, positive correlations between symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, and all the emotion belief variables (r = .18 to r = .33), indicating that stronger beliefs that emotions are uncontrollable and useless were associated with higher levels of symptoms. These patterns were present across both the negative and positive valence domains. Across all four emotion belief domains, depression, anxiety, and stress had the strongest positive correlation with beliefs about the uncontrollability of negative emotions, and the weakest positive correlation with beliefs about the uselessness of negative emotions.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics, reliability statistics, and Pearson correlation matrix for demographic variables, emotion belief variables, and symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress.

To investigate the relationship between the four emotion belief variables and depression, anxiety, and stress, we conducted a path model controlling for age and gender. Path estimates and 95% confidence intervals are reported in , with the standardised estimates illustrated in . Results indicated significant positive pathways between beliefs about the uncontrollability of negative emotions and depression (B = 0.37, 95% CI[0.20, 0.53], β = 0.30, unstandardised SE = .08, p < .001), anxiety (B = 0.21, 95% CI[0.07, 0.34], β = .19, unstandardised SE = .07, p < .001), and stress (B = 0.25, 95% CI[0.12, 0.39], β = 0.22, unstandardised SE = .07, p < .001) scores. There was also a significant positive pathway between beliefs that positive emotions are useless and anxiety scores (B = 0.15 95% CI[0.02, 0.26], β = 0.11, unstandardised SE = .06, p < .05). In total, the model accounted for 11% of the variance in depression scores, 12% of the variance in anxiety scores, and 9% of the variance in stress scores (ps < .001).

Figure 1. Path analysis modelling the relationship between emotion beliefs and depression, anxiety, and stress.

Table 2. Results of path analysis predicting depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms.

Latent profile analysis

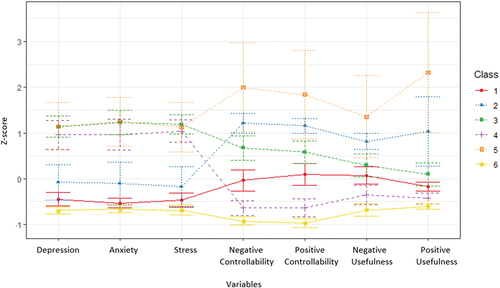

Our LPA indicated the data were best represented by a six-profile solution. Initially, the LPA indicated the data were well represented by a nine-profile solution (see Table S2 in supplementary materials). However, further examination revealed the nine-profile solution (along with the seven-, eight-, and ten-profile solutions) contained profiles consisting of less than 5% of the sample. Given this, the six-profile solution was judged as the best solution. The six-profile solution had the best fit indices compared to the other five remaining solutions, had an acceptable entropy value, and all six profiles in this solution contained more than 5% of the data. The six profiles varied in their levels of depression, anxiety, stress, and emotion beliefs, with levels interpreted as “low” “average” or “high” compared to the z-standardised sample means. Generally, Z scores around 0 are considered average (i.e., representing the mean score in the sample), with higher scores indicating a higher level of maladaptive beliefs about emotions or higher emotional disorder symptoms (see ). No distinct depression, anxiety, or stress profile emerged. Rather, all profiles had either low, average, or high levels of all three emotional disorder symptoms.

Figure 2. Visual representation of the six-profile solution from the latent profile analysis.

Three of the profiles had similarly elevated symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. We refer them here as “high symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” (Profile 3, n = 116), “high symptoms/low maladaptive beliefs” (Profile 4, n = 123), and “high symptoms/high maladaptive beliefs” (profile 5, n = 51). Whilst displaying similar symptom severity, these profiles had notable differences in their patterns of emotion beliefs. The “high symptoms/high maladaptive beliefs” profile had higher than average beliefs that emotions were uncontrollable and useless across both valence domains, which were the most extreme maladaptive beliefs in the sample. Relative to this, the “high symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” had much lower levels of maladaptive beliefs, which were within the average range across both belief categories and both valence domains, and the “high symptoms/low maladaptive beliefs” profile held much more adaptive beliefs about the controllability and usefulness emotions across both valence domains.

The remaining three profiles shared lower levels of emotional disorder symptoms, and again differed in their emotion belief profiles. We refer to them here as “low symptoms/low maladaptive beliefs” (Profile 6, n = 256), “low symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” (Profile 1, n = 280), and “moderate symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” (Profile 2, n = 122). The “low symptoms/low maladaptive beliefs” profile had the lowest symptom severity and held the most adaptive beliefs about the controllability and usefulness of emotions across both valence domains in the sample. The “low symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” profile only had slightly higher symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress, yet much stronger beliefs about emotions being uncontrollable and useless. The “moderate symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” profile had higher levels of symptom severity (albeit still within the average range) and was characterised by elevated beliefs that both positive and negative emotions were uncontrollable and useless.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to examine the relationship between emotion beliefs and depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms. Overall, our results support the notion that maladaptive emotion beliefs, across both valence domains, may play an important role in emotional disorder symptoms.

Links between emotion beliefs and emotional disorder symptoms

In terms of raw associations, our Pearson’s correlations revealed that individuals holding stronger beliefs that emotions are uncontrollable and useless also generally had more severe symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress. Crucially, these patterns were present across both negative and positive emotions. This therefore represents a novel extension of past work, which has previously tended to focus only on controllability beliefs (e.g., De Castella et al., Citation2013) or on beliefs about only negative emotions (e.g., Manser et al., Citation2012). Consistent with Ford and Gross’s (Citation2018) theorising, our results highlight the importance of broadening this scope to usefulness beliefs and positive emotions too.

Our path analysis also indicated that, of all the belief categories, beliefs about the uncontrollability of negative emotions appear to be particularly important, as the EBQ’s negative-controllability subscale was the only significant unique path to all three symptom categories. The salience of this particular emotion belief makes theoretical sense here; if individuals believe they are incapable of controlling their negative emotions, they may be more distressed by them, and less likely to use adaptive emotion regulation strategies to decrease negative emotional experiences (Ford & Gross, Citation2019) that centrally characterise states of depression, anxiety, and stress (Lovibond & Lovibond, Citation1995). However, the reverse direction of influence was not explored, but may also be true; experiencing severe negative emotional states may make emotion regulation more difficult, contributing to heightened beliefs about the uncontrollability of negative emotions (Deplancke et al., Citation2022). Our path analysis also revealed that believing positive emotions are useless significantly predicted anxiety symptoms. One potential explanation for this belief being a predictor of anxiety symptoms, but not depression or stress symptoms, could be because of the perceived value of worry, a regulation strategy for negative emotions, in anxiety disorders (Georgiades et al., Citation2021). Individuals with anxiety often see worry as advantageous, in that it increases cautiousness to help avoid unfavourable outcomes (e.g., “worry stops me from doing something to embarrass myself”; Wells, Citation1995). It is possible then that in comparison to this usefulness of negative emotions, people with anxiety may not believe positive emotions serve this same utility. Moreover, if positive emotions are not believed to have utility, individuals may be less motivated to engage in pursuits likely to increase positive affect and buffer against negative emotions. Again, it is possible that this relationship is bidirectional or reversed, so it will be important for future research to further examine this finding.

Profiles of emotion beliefs and emotional disorder symptoms

Our study is, to the best of our knowledge, the first to utilise a LPA approach to explore different profiles of emotion beliefs, and how different combinations of emotion beliefs may exist together (for similar applications to other constructs, see Preece et al., Citation2021). These LPA findings appear to reinforce the transdiagnostic relevance of the emotion belief construct, as we did not find distinct profiles for depression, anxiety, and stress amongst our sample; rather, profiles were either globally high, average, or low in all three symptom categories. However, it is worth noting that this is likely due in part to the fact that there were high correlations between the depression, anxiety, and stress subscales in the current study. Similarly, another key finding here was that profiles did not seem to differ dramatically in their level of controllability versus usefulness beliefs, or their level of beliefs for negative versus positive emotions. Profiles instead tended to have either globally high levels of maladaptive beliefs across all categories, or more average or adaptive beliefs across all categories. This lack of differentiation within each emotion belief profile appears to suggest that individuals might either hold none of the maladaptive emotion beliefs, or the full “set”, which could collectively have a transdiagnostic impact across all three of the emotional disorder symptom categories (or, if the reverse direction of influence is true, be impacted by all three of the emotional disorder symptom categories). It is also possible that individuals may have finer emotion belief differentiation at the level of discrete emotions rather than global positive and negative valence domains. For example, a person might believe that anxiety is relatively uncontrollable despite often being quite useful, while at the same time believing that anger is neither controllable nor useful. Examining this kind of more granular belief differentiation may shed additional light onto the roles of emotion beliefs in emotional disorders.

Another key finding from our LPA was that although profiles with greater symptoms of depression, anxiety, and stress tended to hold stronger beliefs that emotions were uncontrollable and useless, this pattern was not ubiquitous. For example, participants in the “high symptoms/low maladaptive beliefs” profile had high levels of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms, yet held relatively adaptive beliefs about the controllability and usefulness of positive and negative emotions. Moreover, participants in the “moderate symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” profile did not have elevated symptoms, but held relatively maladaptive beliefs about emotions. We think these findings make conceptual sense, as emotion beliefs are but one of many factors that might exert an influence on an individual’s emotional experience and emotional disorder risk (e.g., Kneeland et al., Citation2016). In cases where individuals hold beliefs that emotions are uncontrollable and useless, but do not have elevated symptoms, these beliefs may still mean the individual is at higher risk of developing emotional disorders in the future. Conversely, if this relationship is operating in reverse, it’s possible that individuals who are not experiencing emotional disorder symptoms are still having difficulty regulating their emotions, which may contribute to stronger beliefs that emotions are less controllable or useful. Contextual factors, such as the presence environmental stressors, may be contributing to disorder symptomatology in individuals with low maladaptive beliefs (i.e., the “high symptoms/low maladaptive beliefs” profile), whilst the absence of environmental stressors might be cushioning individuals with lower symptomatology despite higher maladaptive beliefs (i.e., the “moderate symptoms/moderate maladaptive beliefs” profile). Future research should consider the potential influence of such factors.

Implications for theory and practice

These findings have several important theoretical and clinical implications. Theoretically, our pattern of results support Ford and Gross’s (Citation2018) emotion belief framework, whereby both controllability and usefulness beliefs, across both valence domains, are theorised to play an important role in long term mental health outcomes, likely via their role in providing a foundation for successful (or impaired) emotion regulation patterns. Our findings suggest that the full breadth of emotion beliefs are likely important to consider in the conceptualisation of symptoms associated with common emotional disorders. Not all individuals with high emotional disorder symptoms will necessarily hold beliefs about emotions being uncontrollable and useless, but when such beliefs are present this appears to put people at greater risk. If these findings are replicated in clinical samples, they may indicate that it would be beneficial to routinely assess for such emotion beliefs and target them in treatment. In assessments, validated tools like the EBQ (Becerra et al., Citation2020) are likely to have high utility. In terms of treatments, many existing cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) approaches focus on broadly targeting and challenging unhelpful beliefs (Beck, Citation1964), and have central focuses on developing emotion regulation skills. It is rarer, however, for treatments to directly focus on changing emotion beliefs, particularly with respect to the controllability and usefulness of positive emotions. Considering that much of psychotherapy is based upon the premise that emotions are changeable, individuals who already believe in the controllability and usefulness of emotion may be more likely to engage in psychotherapy (Kneeland et al., Citation2016). Contrarily, individuals holding less adaptive emotion beliefs might benefit from clinicians beginning the treatment process with psychoeducation and targeted CBT focused on the nature of emotions, to initially address maladaptive emotion beliefs (Kneeland et al., Citation2016), prior to moving on to interventions aimed at developing more adaptive emotion regulation abilities (Ford & Gross, Citation2019).

Limitations and future directions

Although we believe this study makes a useful contribution, there are some limitations that could be addressed in future research. First, the cross-sectional nature of the data precludes conclusions about directionality and causality. Future longitudinal and experimental work would be beneficial in providing a direct examination of the impact of emotion beliefs on emotional disorder symptoms (Ford & Gross, Citation2018). The reverse direction of influence should also be examined. It is possible that individuals with emotional disorders may experience emotions that are less controllable and useful, which leads them to form accurate beliefs that reflect the reality of their lived experience. Second, the scope of this paper was focused only on exploring the links between emotion beliefs and common emotional disorder symptoms. In future, it would be beneficial for researchers to extend on this work by examining emotion beliefs alongside other variables that might interact to influence emotional disorders, such as alexithymia (Preece et al., Citation2022) or emotion regulation (Ford & Gross, Citation2019). Third, although nearly two thirds (64%) of our participants self-reported having received a mental health diagnosis in the past, we did not use a clinical sample. The extent to which emotion beliefs exert an influence over emotional disorder symptoms might be different for those with and without severe mental health disorders (Becerra et al., Citation2020). As such, future research should consider comparing the emotion belief profiles of clinical versus nonclinical populations. Furthermore, the current sample was predominantly White, Australian born, and female. Culture can exert a pervasive influence over perceptions towards emotions and motivation to regulate emotions (Ford & Mauss, Citation2015). Thus, we cannot infer whether the current patterns would replicate cross-culturally. Future work examining cross-cultural associations between emotion beliefs and emotional disorders would be beneficial (Ford & Gross, Citation2019).

Conclusion

Our data suggest that beliefs about both the controllability and usefulness of emotions, across both the negative and positive valence domains, are related to common emotional disorder symptoms. Our findings thus highlight the importance of comprehensively considering emotion beliefs in the conceptualisation, assessment, and treatment of depression, anxiety, and stress symptoms.

Ethics statement

Ethics approval was granted for this project. All requirements of the ethics committee were followed. All participants provided informed consent for their data to be used.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (14.3 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data will be made available on request by contacting the corresponding author.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2023.2290734

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akogul, S., & Erisoglu, M. (2017). An approach for determining the number of clusters in a model-based cluster analysis. Entropy, 19(9), 452–466. https://doi.org/10.3390/e19090452

- Becerra, R., Gainey, K., Murray, K., & Preece, D. A. (2023). Intolerance of uncertainty and anxiety: The role of beliefs about emotions. Journal of Affective Disorders, 324, 349–353. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.12.064

- Becerra, R., Preece, D. A., Gross, J. J., & Blanch, A. (2020). Assessing beliefs about emotions: Development and validation of the Emotion Beliefs Questionnaire. PLoS One, 15(4), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0231395

- Beck, A. T. (1964). Thinking and depression: II. Theory and therapy. Archives of General Psychiatry, 10(6), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.1964.01720240015003

- Bullis, J. R., Boettcher, H., Sauer‐Zavala, S., Farchione, T. J., & Barlow, D. H. (2019). What is an emotional disorder? A transdiagnostic mechanistic definition with implications for assessment, treatment, and prevention. Clinical Psychology Science & Practice, 26(2), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0101755

- Crawford, J. R., & Henry, J. D. (2003). The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS): Normative data and latent structure in a large non‐clinical sample. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 42(2), 111–131. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466503321903544

- De Castella, K., Goldin, P., Jazaieri, H., Ziv, M., Dweck, C. S., & Gross, J. J. (2013). Beliefs about emotion: Links to emotion regulation, well-being, and psychological distress. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 35(6), 497–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/01973533.2013.840632

- Deplancke, C., Somerville, M. P., Harrison, A., & Vuillier, L. (2022). It’s all about beliefs: Believing emotions are uncontrollable is linked to symptoms of anxiety and depression through cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. Current Psychology, 42(25), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03252-2

- Ferguson, S. L., G Moore, E. W., & Hull, D. M. (2020). Finding latent groups in observed data: A primer on latent profile analysis in mplus for applied researchers. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 44(5), 458–468. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025419881721

- Ford, B. Q., & Gross, J. J. (2018). Emotion regulation: Why beliefs matter. Canadian Psychology / Psychologie Canadienne, 59(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000142

- Ford, B. Q., & Gross, J. J. (2019). Why beliefs about emotion matter: An emotion-regulation perspective. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 28(1), 74–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721418806697

- Ford, B. Q., Lwi, S. J., Gentzler, A. L., Hankin, B., & Mauss, I. B. (2018). The cost of believing emotions are uncontrollable: Youths’ beliefs about emotion predict emotion regulation and depressive symptoms. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 147(8), 1170–1190. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000396

- Ford, B. Q., & Mauss, I. B. (2015). Culture and emotion regulation. Current Opinion in Psychology, 3, 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2014.12.004

- Georgiades, J., Cusworth, K., MacLeod, C., Notebaert, L., & Manelis, A. (2021). The relationship between worry and attentional bias to threat cues signalling controllable and uncontrollable dangers. PloS One, 16(5), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0251350

- Gross, J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/1047840x.2014.940781

- Gross, J. J., & Jazaieri, H. (2014). Emotion, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: An affective science perspective. Clinical Psychological Science, 2(4), 387–401. https://doi.org/10.1177/2167702614536164

- Kneeland, E. T., Dovidio, J. F., Joormann, J., & Clark, M. S. (2016). Emotion malleability beliefs, emotion regulation, and psychopathology: Integrating affective and clinical science. Clinical Psychology Review, 45, 81–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2016.03.008

- Kneeland, E. T., Goodman, F. R., & Dovidio, J. F. (2020). Emotion beliefs, emotion regulation, and emotional experiences in daily life. Behavior Therapy, 51(5), 728–738. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2019.10.007

- Lovibond, S. H., & Lovibond, P. F. (1995). The structure of negative emotional states: Comparison of the Depression Anxiety Stress Scales (DASS) with the Beck Depression and Anxiety Inventories. Behavioural Research and Therapy, 33(3), 335–343. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)00075-U

- Manser, R., Cooper, M., & Trefusis, J. (2012). Beliefs about emotions as a metacognitive construct: Initial development of a self-report questionnaire measure and preliminary investigation in relation to emotion regulation. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 19(3), 235–246. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.745

- Nylund, K. L., Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2007). Deciding on the number of classes in latent class analysis and growth mixture modeling: A Monte Carlo simulation study. Structural Equation Modeling, 14(4), 535–569. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701575396

- Osman, A., Wong, J. L., Bagge, C. L., Freedenthal, S., Gutierrez, P. M., & Lozano, G. (2012). The Depression Anxiety Stress Scales-21 (DASS-21): Further examination of dimensions, scale reliability, and correlates. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 68(12), 1322–1338. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.21908

- Preece, D. A., Becerra, R., Robinson, K., Dandy, J., & Allan, A. (2018). Measuring emotion regulation ability across negative and positive emotions: The Perth Emotion Regulation Competency Inventory (PERCI). Personality and Individual Differences, 135, 229–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.025

- Preece, D. A., Goldenberg, A., Becerra, R., Boyes, M., Hasking, P., & Gross, J. J. (2021). Loneliness and emotion regulation. Personality and Individual Differences, 180, 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110974

- Preece, D. A., Mehta, A., Becerra, R., Chen, W., Allan, A., Robinson, K., Boyes, M., Hasking, P., & Gross, J. J. (2022). Why is alexithymia a risk factor for affective disorder symptoms? The role of emotion regulation. Journal of Affective Disorders, 296, 337–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.085

- Ranjbar, S., Mazidi, M., Gross, J. J., Preece, D., Zarei, M., Azizi, A., Mirshafiei, M., & Becerra, R. (2023). Examining the cross cultural validity and measurement invariance of the Emotion Beliefs Questionnaire (EBQ) in Iran and the USA. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 45(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-023-10068-2

- Rosenberg, J. M., Beymer, P. N., Anderson, D. J., & Schmidt, J. A. (2018). TidyLPA: An R package to easily carry out latent profile analysis (LPA) using open-source or commercial software. The Journal of Open Source Software, 3(30), 978. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.00978

- Tamir, M., John, O. P., Srivastava, S., & Gross, J. J. (2007). Implicit theories of emotion: Affective and social outcomes across a major life transition. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(4), 731–744. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.4.731

- Tein, J. Y., Coxe, S., & Cham, H. (2013). Statistical power to detect the correct number of classes in latent profile analysis. Structural Equation Modeling, 20(4), 640–657. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2013.824781

- Veilleux, J. C., Chamberlain, K. D., Baker, D. E., & Warner, E. A. (2021). Disentangling beliefs about emotions from emotion schemas. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(4), 1068–1089. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.23098

- Veilleux, J. C., Pollert, G. A., Skinner, K. D., Chamberlain, K. D., Baker, D. E., & Hill, M. A. (2021). Individual beliefs about emotion and perceptions of belief stability are associated with symptoms of psychopathology and emotional processes. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110541

- Wells, A. (1995). Meta-cognition and worry: A cognitive model of generalized anxiety disorder. Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 23(3), 301–320. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1352465800015897