ABSTRACT

Objective

While previous systematic reviews have focused on individual interventions for refugees, the current study aims to contribute to the literature by systematically reviewing the effectiveness of group and community-based interventions, to provide insight into ways current treatments can be scaled and integrated into stepped-care interventions.

Method

A systematic review was conducted. In September 2022, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Embase and CINAHL were systematically searched and findings were analysed using narrative thematic analysis.

Results

Key findings were that in general the group format was effective, especially when paired with an intervention such as cognitive behavioural therapy. The findings also point to barriers and facilitators for accessing group interventions, including language, cultural safety, and gender considerations.

Conclusion

In general, while groups were not typically seen as a replacement for individual therapy, the included studies suggested the complementary value of group modalities, as well as their utility as an early access intervention. Ultimately, the existing body of research concerning group interventions indicates that treatments delivered in a group format have utility and scalability and should be considered for integration into stepped models of care for people with refugee backgrounds.

KEY POINTS

What is already known about this topic:

Stepped care enhances access to mental health care.

Refugees have a higher vulnerability to developing mental illness and lower access to services.

Group programmes are often more culturally responsive for refugees.

What this topic adds:

Stepped care should include group-based and community interventions at the lower tiers of stepped care models.

In-language culturally adapted group interventions are generally effective and accessible for refugees.

To enhance accessibility, practitioners should consider providing transport and childcare as part of facilitating group-based interventions.

Introduction

A significant body of previous literature indicates that while many refugees have remarkable adaptive skills (Simich & Andermann, Citation2014), they face significant obstacles to maintaining positive mental health. These include exposure to war, experiences of torture and trauma, and challenges in resettlement such as family separation, language barriers, discrimination, acculturation stressors, and social isolation (Due et al., Citation2020; Li et al., Citation2016). As a result, people with refugee backgrounds (hereafter: termed “refugees” for brevity) are more vulnerable to mental disorders (e.g., see Bogic et al., Citation2015; Turrini et al., Citation2017), and have a corresponding increased need for psychological interventions that are appropriate, effective and accessible (Byrow et al., Citation2020; Hynie, Citation2018). One way to enhance accessibility is through a stepped care approach to treatment, where group and community-based interventions form an integral “step” or component of care (Cornish, Citation2020). While there is growing evidence for the role of stepped care in mental health service delivery in the general population, there is very little research on stepped care interventions for refugees and particularly for group and community-based interventions (Böge et al., Citation2020; Maehder et al., Citation2018). A literature review of group interventions with survivors of torture and severe violence by Bunn et al. (Citation2018) indicated group treatment as an effective approach in providing care to larger groups of survivors. The current study aimed to add to these findings. Specifically, this research aimed to provide a systematic literature review of the effectiveness of group-based psychological interventions with refugees.

Background and previous literature

In terms of previous research related to effectiveness of mental health interventions for refugees, a systematic review of social, psychological and welfare interventions with torture survivors, many of whom were refugees (Patel et al., Citation2014), reported moderate effects – maintained at 6-month follow-up – for Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) and Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (CBT) in treatment of PTSD symptoms. These findings are supported by other reviews (e.g., see Slobodin & de Jong, Citation2015; Tribe et al., Citation2019). Additionally, a recent meta-analysis by Turrini et al. (Citation2019) of psychosocial interventions in asylum seekers and refugees supported the effectiveness of CBT in reducing PTSD symptom severity for refugees and also found Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR) effective in reducing depression symptoms. Trauma-focused psychotherapy (TFP) has also been indicated as effective, albeit by a small number of studies (Nosè et al., Citation2017). Finally, an overview of systematic reviews on mental health promotion, prevention, and treatment of common mental disorders for refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons by Uphoff et al. (Citation2020) identified CBT and NET and a range of different integrative and interpersonal therapies as the most frequently used interventions.

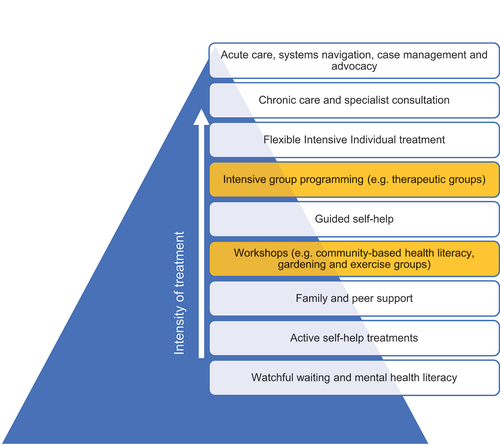

Stepped-care refers to a model of service delivery in which individuals are offered lower intensity options before progressing to more intensive interventions if there is no improvement in mental health outcomes, with the aim of improving accessibility of mental health support (Cornish, Citation2020). Stepped-care is an evidence-based model of care that has empirical support; Pottie et al. (Citation2011) research offered a stepped-care approach in their clinical guidelines for refugees and immigrants. Generally, psychoeducation and group interventions are proposed as early-level care options, with more resource and cost-intensive steps such as individual psychotherapy higher in the care hierarchy (Cornish, Citation2020). Stepped-care models may be particularly suitable for refugees and culturally diverse populations since they can increase access to mental health care by reducing potential barriers to engaging in individualistic treatments. However, there is currently little research regarding the use of stepped care models of mental healthcare for refugees. German researchers have proposed one model, although evaluation is underway and not yet published (Böge et al., Citation2020; Schneider et al., Citation2017).

There is good evidence for group interventions in culturally diverse populations more generally in terms of reductions in mental disorders. Examples in Australia include a music therapy group in a cross-cultural aged care sample (Vannie & Denise, Citation2011), a group CBT intervention with war affected young migrants (Ooi et al., Citation2016), and a community-based mindfulness programme for Arabic and Bangla-speaking migrants (Blignault et al., Citation2021). International research has also demonstrated effectiveness of group interventions for culturally diverse groups, including a CBT support group for Latina migrant workers living in the United States (Hovey et al., Citation2014) and group sandplay therapy for migrant women living in South Korea (Jang & Kim, Citation2012).

As such, a stepped-care approach may offer more flexibility for mental health interventions for refugees, including the use of group interventions at lower levels of the model (Mitschke et al., Citation2017). Thus, group-based interventions may present alternatives to individually administered treatments while maintaining cultural safety for refugee service users. This systematic review of the literature therefore aimed to collate existing evidence concerning group interventions for mental healthcare for refugees.

Materials and methods

Protocol registration

This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO No. CRD42020214814).

Selection strategy

This review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA; Page et al., Citation2021), and the search strategy for this systematic review was developed using the PICO method (Methley et al., Citation2014). All empirical, peer-review studies with primary data were included, with mixed methods, quantitative and qualitative studies eligible. Studies were required to be published in English. However, in two cases, the authors of papers not published in English but which seemed relevant were contacted to try and obtain English translated versions, but this did not lead to any response.

The population of interest (P) was adult refugee participants and/or mental health service providers, defined as psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers, occupational therapists, mental health nurses, and cultural or peer support workers reporting on the experiences of adult refugees in group therapy. Articles were excluded if participants were aged under 18.

If samples included asylum seekers, refugee data had to be disaggregated so that refugee data was clear. The term “refugee” was defined as humanitarian migrants who meet the UNHCR criteria for refugee status (United Nations High Commisioner for Refugees [UNHCR], Citation1951). Asylum seeker’s are people who have not yet met this criteria but are seeking asylum outside their country of origin (UNHCR, Citation1951). The decision to exclude asylum seekers in this review was made since in many countries asylum seekers are ineligible for health services and therefore considerations for this group are likely to be different (Spike et al., Citation2011).

Where studies included both refugee and asylum seeker participants, authors were contacted to see if there was refugee-specific data available. Two authors responded (Fish & Fakoussa, Citation2018; Logie et al., Citation2016); however, refugee-specific data was not available and the studies were excluded. Studies conducted in refugee camps were also excluded; only those related to resettled refugees were eligible.

Group-based psychological and psychosocial interventions were the intervention (I). Again, if studies included both individual and group interventions, group data had to be disaggregated; one paper fell into this category and the authors (Karageorge et al., Citation2018) were contacted. However, they did not respond and the study was excluded.

There was no comparison (C) group, while the outcome (O) component related to effectiveness. Specifically, studies needed to explore the effectiveness (or perceptions of effectiveness, in the case of qualitative studies) of group interventions for refugees in relation to psychological or psychosocial wellbeing, or report on the barriers and facilitators to accessing group interventions.

Database searches

In September 2022, PsycINFO, PubMed, Scopus, Embase and CINAHL were systematically searched for papers published in English between 1 January 2010 and 11 September 2022. This timeframe was chosen for recency of evidence, and also because two major systematic reviews on the topic were published in 2010; namely Murray et al. (Citation2010) review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement and Crumlish and OʼRourke’s (Citation2010) review of treatments for PTSD among asylum-seekers and refugees. As such, 2010 was chosen as the earliest date of publication in order not to duplicate past reviews, but rather build on this earlier work. Database alerts were set when the initial search was conducted.

Search strategies were developed in consultation with a university research librarian and key terms related to the population, disorder and intervention were tailored to each database. Key terms related to populations (i.e., “refugee”, “humanitarian migrant”), disorder or wellbeing (i.e., “trauma”, “wellbeing”) and intervention (i.e., “psychotherapy”, “support group”). Reference checks of included studies and relevant systematic reviews were also undertaken; no further studies were identified through this process. For an example of the search strategy used, see Supplementary Table S1.

Study selection

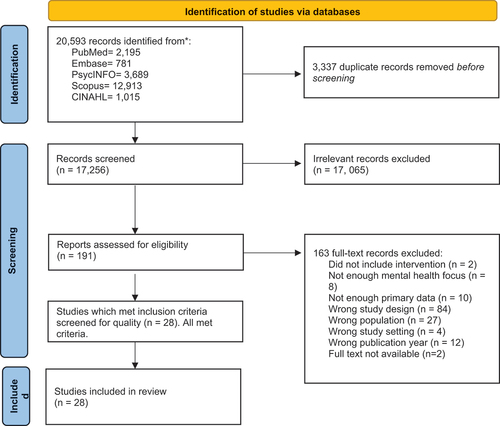

The initial search strategy resulted in identification of 20,593 articles. After duplicates were removed, there were 17,256 unique papers. The second author undertook preliminary title and abstract screening using Covidence software to manually screen the papers against the inclusion criteria. Papers that did not meet inclusion criteria were excluded (n = 17,065). One hundred and ninety-one potentially eligible papers were identified, and full-texts screened against the inclusion criteria. The first author screened a random selection of 10% of the papers, with high interrater reliability (98%). This process resulted in 28 relevant papers. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion between the two reviewers. The PRISMA flow chart () below depicts the study selection process. Additionally, database search alerts between 11 September 2022 and 30 June 2023 were scanned (titles and abstracts of 972 papers), resulting in no new papers meeting inclusion criteria.

Quality assessment

Issues of quality in the reported papers were considered with reference to the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (Hong et al., Citation2018) consistent with systematic review protocols. The MMAT allows an appraisal of quality based on the following criteria: clarity of the research questions, whether the data allows consideration of the research questions and then (depending on the study methodology), questions related to sampling, measurements, and data analysis. Article quality was only considered with respect to the papers as they appeared in their published form. Authors were not contacted for further information about the quality of their studies. Notably, the MMAT guide (Hong et al., Citation2018) explicitly discourages exclusion of studies based on quality. However, it is recognised that the quality of included papers is an important consideration for the conclusions of any systematic review, and thus information about quality of the papers is provided below and in the Discussion.

Data extraction

Due to the diverse designs and aims of the studies, no meta-analysis was performed. Instead, results of the studies were synthesised using inductive thematic analysis. This was performed according to Finlayson and Dixon’s (Citation2008) guidelines for data extraction. Consistent with this methodology, the first author explored the findings of the included studies for patterns of meaning, following which relevant findings were collated in an Excel spreadsheet. Initially, key information including study design (mixed methods, quantitative, qualitative), participant group (refugees, service providers, both), sample size, resettlement country, outcome focus (therapeutic group, health-promotion group, community-based intervention) was extracted). Further codes were then developed based on effectiveness, accessibility, and broader benefit, as well as cultural elements such as cultural safety. Subsequently, the authors grouped the codes into subthemes and then into broader themes. These thematic groupings were formed based on the perceived fit of the coded data against the research question. Quotes were extracted from the qualitative studies but are not included here for brevity. Finally, themes were reviewed, refined and named.

Results

Twenty-eight peer-reviewed papers met the inclusion criteria.

Description of studies

provides an overall summary of study characteristics.

Table 1. Summary of included articles.

The 28 studies comprised 12 quantitative, five qualitative and 11 mixed methods papers. Twenty-four studies included refugee participants, while one study included service providers only, and three included a mixed sample of service providers and refugees. All studies were conducted in high-income resettlement countries, with most studies conducted in the United States (US).

With regard to intervention modality, groups were categorised as either: therapeutic groups (10 papers; incorporating a range of psychological therapeutic modalities as shown in ), health promotion groups (11 papers; incorporating mental health literacy or trauma-informed group interventions) or community-based interventions (seven papers; incorporating a range of interventions that also included mental health outcomes such as financial empowerment, exercise, and gardening groups). For a comprehensive summary of interventions see .

Quality of evidence base in the reported papers

The MMAT has two initial criteria to consider: 1) whether there are clear research questions and 2) whether the collected data allow the research questions to be addressed. All studies in this review met these criteria. In relation to the quantitative studies, the one quantitative randomised control trial (Kananian et al., Citation2020) met all criteria (randomisation was appropriately performed, groups were comparable at baseline, there was complete outcome data, participants adhered to the assigned intervention and outcome assessors were blinded to the intervention). In terms of the quantitative non-randomised studies, all had collected data reported in the papers which allowed for the stated research questions to be answered. In addition, in terms of other criteria 1) all had participants who were representative of the target population, although it should be noted that, as shown in sample sizes were often very small. The second criterion asks if appropriate measures are used, and this was also met by all studies, although it is worth noting that there are issues with the cultural appropriateness of many standardised mental health measures which may have impacted quality in this domain. All but one study had complete outcome data (the third criterion); in the study by Mitschke et al. (Citation2013) an item in one measure was deemed culturally inappropriate by the researchers (specifically an item relating to sexual libido), and as such was omitted during data collection. All studies accounted for confounds in the design, addressing the fourth criterion. Again however, it should be noted that research with resettled refugees is very difficult to complete, with challenges associated with cultural applicability, relevance of measures, language, and recruitment. Thus while no studies clearly did not account for confounds, it is important to note the complexity of research in this area. Finally, analysis and interventions were administered as intended in all studies, addressing the final criterion.

For qualitative studies, all of the other five criteria were met, namely 1) the qualitative approach was appropriate; 2) the qualitative data collection methods were adequate; 3) the findings were clearly derived from the data; 4) the results were clearly based on the data, and; 5) and there was a coherence between the data, the analysis and the conclusions.

Finally, for the mixed-methods studies, MMAT criteria are as follows: 1) there is an adequate rationale for using mixed methods; 2) the different components of the study are clearly integrated to answer the research questions; 3) the outputs of the integration are clearly interpreted; 4) inconsistencies between qualitative and quantitative arms are addressed; and 5) the different components of the study adhere to the quality criteria of each tradition of the methods involved. Two studies met all criteria (Baird et al., Citation2017; Gerber et al., Citation2017). Five studies did not provide an adequate rationale for using a mixed-methods design (Brochmann et al., Citation2019; Haefner et al., Citation2019; Hartwig & Mason, Citation2016; Husby et al., Citation2020; Salt et al., Citation2017). Three studies did not effectively synthesise the different components of the study (Hartwig & Mason, Citation2016; Im & Swan, Citation2020; Subedi et al., Citation2015). Divergencies in quantitative and qualitative findings were not adequately addressed in two of the studies (Eriksson-Sjöö et al., Citation2012; Haefner et al., Citation2019). For one study, no method for the qualitative component of data collection was described (Haefner et al., Citation2019).

As noted above, given the complexities of research in this area it is again worth noting generally small sample sizes across many of the studies in particular. However, as also noted above, the MMAT does not recommend excluding studies, and given the aforementioned challenges of research in this space the authors feel that all evidence is valuable in addressing this research question. However, the review attempts to synthesise findings with respect to quality and especially the low sample sizes, which may affect conclusions. This is further addressed particularly in the Discussion.

Thematic findings

The thematic synthesis of the findings is discussed across two sections: the first regarding effectiveness, and the second regarding broader challenges and benefits to the group format.

Effectiveness of interventions

Effectiveness of interventions varied by intervention type. A summary of findings related to effectiveness is provided below, organised by type of intervention.

Effectiveness of therapeutic groups: CBT based interventions

Overall, all three studies exploring group CBT – or a modification thereof – found at least some significant reductions in psychological distress. However, there were variations in which mental health outcomes showed improvements. In their study of a group CBT intervention with North Korean refugees resettled in South Korea, Jeon et al.’s (Citation2020) results indicated all participants (n = 38) showed a significant difference in both anxiety and depression scores before and after treatment. In Kananian et al.’s (2017) study of the effects of group-based culturally adapted-CBT with Farsi-speaking refugees (n = 9) resettled in Germany, large improvement effects were seen for general psychopathology and quality of life. However, moderate but not significant improvement effects were seen in depression and trauma. Finally, Haefner et al. (Citation2019) study of their CBT+ intervention (incorporating elements of mindfulness, psychoeducation, stress management and interpersonal effectiveness skills) with refugees resettled in the United States (n = 18) found a reduction in PTSD symptoms. While these studies show improvement, the small samples are worth noting.

Effectiveness of therapeutic groups: cognitive processing/EMDR based interventions

Overall studies concerning group-based CM-CPT and EMDR showed mixed findings, with potential effectiveness for trauma especially. In their study of culturally modified cognitive processing therapy (CM-CPT) with Karen refugees resettled in Australia (n = 7), Bernardi et al. (Citation2019) found mixed reliable change results for PTSD in particular, with improvement initially followed by increased symptoms for four participants. In contrast, in an evaluation by Han et al. (Citation2012) of CM-CPT delivered to Cambodian refugees resettled in the US, all nine participants reported significantly improved PTSD. Lehnung et al. (Citation2017) intervention with Syrian and Iraqi refugees (n = 18) resettled in Germany indicated that two sessions of group Eye Movement Desensitisation and Reprocessing (EMDR G-TEP) following general psychoeducation reduced trauma. There was no statistically significant improvement in depression.

Effectiveness of therapeutic groups: other interventions

Two studies examined other types of therapeutic interventions and again found mixed results. Following their delivery of a transdiagnostic intervention which incorporated psychoeducation, Acceptance and Commitment Therapy and problem-solving therapeutic principles among others, van Heemstra et al. (Citation2019) found a significant increase in self-efficacy, and a significant decrease in general psychopathology with small-medium effects in their sample of refugees resettled in the Netherlands (n = 49). Robertson et al. (Citation2019) study of a psychoeducational, health realisation intervention with Somalian refugees resettled in the United States (n = 65), reported no statistically significant differences for anxiety and depression.

Effectiveness of health promotion: mental health literacy/mental health first aid training

Five studies focussed on mental health first aid training (MHFA) for refugees; specifically correct identification of various mental disorders and/or specific treatments. Studies found improvement in recognition of depression (Mitschke et al., Citation2013; Subedi et al., Citation2015) and the role of anti-depressants (Slewa-Younan et al., Citation2020b), anxiety (Mitschke et al., Citation2013), trauma (Mitschke et al., Citation2013), schizophrenia (Gurung et al., Citation2020) as well as general mental health literacy and de-stigmatisation of mental illness more generally (Gurung et al., Citation2020; Slewa-Younan et al., Citation2020b). In their delivery of MHFA training, Subedi et al. (Citation2015) found participants were also more likely to report feeling confident in providing help. Notably these studies had higher sample sizes, ranging from 31 to 458.

Effectiveness of health promotion: psychoeducation

Three mixed methods studies found that psychoeducation groups showed efficacy in reducing psychological distress, while one reported no significant effects. Research by Small et al. (Citation2016) comparing office-based counselling, home-based counselling and a community-based psychoeducational group with refugees resettled in the US (n = 81), found all three groups showed significant improvements in anxiety, somatisation, and PTSD, but that the psychoeducational group was particularly effective “due to its accessibility, feasibility, and cost-effectiveness” (p. 355). Baird et al. (Citation2017) (n = 12 refugees) and Husby et al. (Citation2020) (n = 32 refugees) both explored psychoeducation groups and found significant wellbeing improvements. However, research into a community sewing group with African women led by Salt et al. (Citation2017), which incorporated a psychoeducation component for refugee participants (n = 12) found no statistically significant difference in the total scores for the general distress.

Effectiveness of health promotion: general health information

Eriksson-Sjöö et al. (Citation2012) mixed-methods evaluation of a general health information group training course conducted with Arabic-speaking refugees (n = 39) resettled in Sweden found that the course led to lower levels of depression. Im and Swan (Citation2020) also conducted a mixed methods study on cross-cultural trauma-informed care workshops including refugees and service providers (total n = 124). They reported significant improvements in providers’ knowledge of culturally responsive trauma-informed care.

Effectiveness of community-based interventions

Seven studies explored community-based interventions which included two financial empowerment groups, two exercise groups, and three gardening-based group interventions.

Two studies, one quantitative (Mitschke et al., Citation2013) and one qualitative (Praetorius et al., Citation2016) examined financial education programmes. Mitschke et al. (Citation2013) found significant reductions in PTSD, depression, anxiety, and somatization among refugees from Bhutan (n = 65). Praetorius et al. (Citation2016) found that refugees also from Bhutan (n = 12) reported improvements in their perceptions of their mental health.

Two studies delivered group exercise-based interventions. In Hashimoto‐Govindasamy and Rose’s (Citation2011) qualitative analysis of exercise-based intervention with Sudanese refugee women resettled in Australia (n = 12), participants spoke repeatedly of “forgetting their miseries” and the past. Similarly, in Nilsson et al. (Citation2019) qualitative analysis of a structured physical activity and exercise intervention with Arabic-speaking refugee women resettled in Sweden (n = 33), participants reported a range of improvements to wellbeing.

Three studies involved group gardening-based interventions. A mixed methods study by Hartwig and Mason (Citation2016) that included South-East Asian refugee participants and service providers (n = 97) resettled in the US found improvements in depression. A mixed methods gardening intervention by Gerber et al. (Citation2017) with Bhutanese refugees (n = 50) resettled in the US demonstrated gardeners reported greater social support than nongardeners. However, there was no statistically significant difference in distress. Finally, in Poulsen et al. (Citation2020) horticultural vocational programme with refugees resettled in Denmark (n = 28), the intervention was reported to reduce social isolation and improve mental wellbeing of participants.

Challenges and benefits of group interventions

The following subthemes were identified in relation to the challenges and benefits of group interventions.

The group format brings benefit to participants

The benefit of the group format in delivering therapeutic interventions was highlighted by 10 studies. For example, group learning benefits were highlighted in Kananian et al.’s (Citation2017) delivery of Culturally Adapted-CBT, where one participant said: “I saw how some other in the group begin to feel better and I tried to practice the things we talked about at home and it worked out”. Preferences for group formats to improve learning around mental health were also seen in studies by Mitschke et al. (Citation2017) and Im and Swan (Citation2020).

Seven papers also reported that a key benefit of groups was that they reduced isolation for participants or promoted other community connections, particularly with people from the same community who had lived in the resettlement country for longer periods of time (Brochmann et al., Citation2019; Haefner et al., Citation2019; Hartwig & Mason, Citation2016; Husby et al., Citation2020; Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Poulsen et al., Citation2020; Praetorius et al., Citation2016).

Enhancing accessibility: food, transport, childcare, reimbursement, location, gender and language

Ten studies reported implementing resources to enhance accessibility for participants. Namely, the provision of food, transport, childcare and reimbursement were key components of enhancing accessibility. For example, Hashimoto‐Govindasamy and Rose (Citation2011), Baird et al. (Citation2017) and Salt et al. (Citation2017) all incorporated food in their group interventions. Other studies provided transport assistance (Baird et al., Citation2017; Hashimoto‐Govindasamy & Rose, Citation2011) or highlighted the importance of this following their group intervention (Haefner et al., Citation2019). Of the eight studies with female participants only, three provided childcare, which participants viewed positively (Baird et al., Citation2017; Haefner et al., Citation2019; Hashimoto‐Govindasamy & Rose, Citation2011). Eight studies reimbursed participants (Baird et al., Citation2017; Gerber et al., Citation2017; Mitschke et al., Citation2013, Citation2017; Praetorius et al., Citation2016; Salt et al., Citation2017; Slewa-Younan et al., Citation2020; Small et al., Citation2016). An intervention by Praetorius et al. (Citation2016) in which participants knitted scarves for sale at a market provided payment to women for their work.

Three studies delivered interventions in communities where refugees lived at local community centres, citing enhanced accessibility as the primary reason for doing so (Mitschke et al., Citation2013, Citation2017; Praetorius et al., Citation2016).

All of the studies considered language issues either through using interpreters or by using bilingual/bicultural staff members, including mental health clinicians themselves. The remaining two studies did not require interpretation, as the resettlement country and language spoken in participants’ country of origin were the same (Brochmann et al., Citation2019; Jeon et al., Citation2020).

Of the included studies, 18 interventions incorporated a mixed gender sample, while eight studies included only women and two included only men. Three studies considered the benefits of segregating participants by gender explicitly. For example, in Hashimoto‐Govindasamy and Rose (Citation2011) evaluation of an exercise group, participants valued that the programme was specifically for women, as this enabled women to speak openly, and also to care for their children (including breastfeeding). Kananian et al.’s (Citation2020) and Nilsson et al. (Citation2019) studies echoed these findings.

Peer-delivered interventions and consulting communities

Four interventions used peer facilitators to deliver group interventions, some of whom were former refugees themselves (Gurung et al., Citation2020; Mitschke et al., Citation2017; Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Small et al., Citation2016). In the study by Nilsson et al. (Citation2019), refugees themselves suggested future interventions should incorporate peer facilitators.

Seven studies consulted with refugee communities when developing content to enhance relevance and ensure cultural appropriateness. Some studies achieved this by establishing focus groups with refugees (Baird et al., Citation2017; Subedi et al., Citation2015; van Heemstra et al., Citation2019), while others enlisted the support of working groups made up of refugee mental health experts and community leaders (Jeon et al., Citation2020; Mitschke et al., Citation2013; Slewa-Younan et al., Citation2020a). Another study engaged a Bhuddist monk to develop and deliver the treatment content (Han et al., Citation2012). Consulting refugees and community stakeholders was supported by refugees themselves, with participants in Mitschke et al.’s (Citation2013) community-based psychoeducation group stressing “the need for a participatory model of program development … expressing a strong desire to be involved in the creation and delivery of program content”.

Establishing participant safety

Establishing participant safety was discussed by two studies. Specifically, in interviewing service providers of group interventions with refugees, Brochmann et al. (Citation2019) noted that some participants reported formalising group norms, utilising the same key therapists, and ensuring individual clients could be attended to where necessary within the group programme. Facilitators also specified the importance of explaining the concept of confidentiality: a core fear of participants. Similarly, group-determined codes of conduct were deemed highly important in Husby et al. (Citation2020) community-based psychoeducational intervention.

Cultural adaptations of content

Seven of the included studies made modifications to group content to reflect culturally relevant adaptations. While some of the interventions engaged in intercultural sharing (Hashimoto‐Govindasamy & Rose, Citation2011; van Heemstra et al., Citation2019), others incorporated culturally specific modifications, such as culturally sensitive practices including seeking spiritual advice, guidance and prayer (Slewa-Younan, 2020b). Other studies included culturally adapted case vignettes (Bernardi et al., Citation2019; Gurung et al., Citation2020; Subedi et al., Citation2015). Some studies adopted cultural concepts of distress and culturally appropriate imagery. For example, in delivering CA-CBT to Afghan refugees, Kananian et al. (Citation2020) included idioms of distress such as “thinking a lot” and a “Persian garden” guided imagery component.

Managing the ending of group interventions

Three studies referred to the need for sensitivity in ending group treatment, and that participants reported not wanting groups to end (Eriksson-Sjöö et al., Citation2012; Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Praetorius et al., Citation2016); suggesting that this is an important consideration in designing group-based interventions

Discussion

This review aimed to explore effectiveness of group-based psychological interventions for resettled refugees. Overall, the majority of papers included in this review reported mixed findings with respect to the effectiveness of group and community-based interventions in terms of reducing psychological distress or mental disorder symptoms. In terms of broader benefits, the review found that community-based interventions were typically effective in improving refugee’s social support and connectedness: group-based exercise, financial empowerment and gardening groups all showed promised is this review, mirroring previous research with general populations (Jiménez-Solomon et al., Citation2016; Luth-Hanssen et al., Citation2020; Smidl et al., Citation2017). Some challenges were identified with respect to accessibility for group interventions for refugees, especially women. These included transport, language, gender considerations in group settings, childcare, and ensuring participant safety and confidentiality.

Overall, therapeutic groups such as those involving CA-CBT or CPT appeared to be more effective in reducing distress and enhancing wellbeing for refugees, while health promotion interventions were effective in improving refugees’ mental health literacy. However, this evidence is impacted by the generally small samples of this research, pointing to the need for higher-quality studies including randomised controlled trials. However, group-based delivery of psychological interventions such as CA-CBT, CPT and EMDR have also been shown to be effective in non-refugee samples (e.g., Jarero et al., Citation2015; Lenz et al., Citation2014; Naeem et al., Citation2015), as have transdiagnostic interventions (Brassington et al., Citation2016), suggesting that the early results of this review are promising in terms of the potential for this mode of delivery. In relation to group-based health promotion interventions, Dolan et al. (Citation2021) also found moderate pre-post treatment reductions in anxiety and depression in their systematic review and meta-analysis of large group psychoeducation in the general population. Some studies in this review reported mixed findings about health promotion (Bernardi et al., Citation2019; Lehnung et al., Citation2017), although this could be attributed to sample size. Overall, more research is required to confirm the efficacy of group interventions in relation to specific mental disorders in refugees.

Several studies identified additional needs of refugees both inside and outside groups which, if implemented, would enhance accessibility and engagement. For example, being aware of and providing support around stressors facing refugees, such as transport, housing, employment and language learning were deemed important (Brochmann et al., Citation2019; Eriksson-Sjöö et al., Citation2012; Hartwig & Mason, Citation2016; Hashimoto‐Govindasamy & Rose, Citation2011; Mitschke et al., Citation2017; Praetorius et al., Citation2016; Robertson et al., Citation2019; Salt et al., Citation2017; Subedi et al., Citation2015), as was ensuring confidentiality and safety for refugees, especially in the context of potential mental health stigma and gender considerations. While many of these components have been documented previously in group interventions with non-refugees (Brabender et al., Citation2004), this review highlights the importance of considering the unique needs of refugees in a group context.

A key consideration when facilitating group interventions was the need for additional support in managing the ending of group treatment, as transitioning out was particularly difficult for refugees (Eriksson-Sjöö et al., Citation2012; Mitschke et al., Citation2017; Nilsson et al., Citation2019; Praetorius et al., Citation2016). The additional needs of refugees aside from mental health treatment has been documented in previous research (e.g., Hynie, Citation2018). Likewise, the difficulty clients experience in care ending is not limited to group therapy: it has also been well documented as a challenge in need of consideration in individual therapy, as discussed in research by Murdin et al. (Citation2015).

While this review has mixed results, and is impacted by the quality of some of the included studies especially with regard to sample sizes and the lack of higher-order evidence such as randomised controlled trials, it is nevertheless suggested that services consider utilising groups within a stepped care model to enhance accessibility and to meet refugees’ needs. In imagining what integrating group and community interventions may look like within service design, Cornish (Citation2020) suggests nine steps, ranging from watchful waiting and mental health literacy as the least intensive step, through to workshops and intensive group programmes as mid-intensity care options, while individual therapy and acute care are as higher intensity tiers of care. Thus, group and community-based interventions with refugees may easily be integrated into a stepped care service model, as suggested in (adapted from Cornish, Citation2020), with two additional steps highlighted in yellow).

This review has some limitations, both in relation to the nature of the included articles and in terms of the conduct of this review itself. In terms of the latter, a key limitation relates to the choice to only include studies published in English, potentially presenting bias. Further, while the authors had no control over the body of literature, the included studies were conducted in high-income resettlement countries only, which reduces the applicability of findings to other settings. Finally, the current study’s decision to exclude asylum seekers from the sample may have introduced bias, as many studies used mixed samples of refugees and asylum seekers and were excluded where data could not be separated. Future research could usefully examine asylum seeker experience and differences across immigration status. Additionally, our focus on group and community-based interventions means that it is outside the scope of this review to comment on the effectiveness of individually administered interventions in refugees and future research could seek to focus on this with regard to all the levels of stepped care models. The exclusion of refugees under 18 years of age also means the model may not be applicable to this group. In terms of limitations of the studies themselves, as noted throughout the results and discussion key concerns related to sample size and study design limited the quality of the included studies and therefore the evidence included in this review. However, again the authors stress that research with refugees is challenging and quality must be viewed in this context. However, these issues do temper the evidence for group interventions, leading to a pressing need for more research.

Conclusion

This review found mixed evidence for the effectiveness of group interventions for refugees, particularly in relation to symptom reduction and sustained benefits across time. Key benefits for refugees found in the studies included enhanced social support and increased knowledge of mental disorders and mental health first aid. For service providers, group programmes may help to alleviate waitlist burden and increase client flow. It is important to consider accessibility to group interventions in the context of the additional needs refugees may have such as housing, employment, language learning and transportation. Additionally, care needs to be taken in managing stigma and patient safety in a group setting. Future group and community-based interventions should be delivered in participants’ primary language and, where appropriate, be separated by gender. In summary, this review highlights that more research is needed before group-based programmes can be considered effective in reducing mental illness for refugees. However, the studies included in the review suggest that group programmes may have an important role in a stepped care approach, especially where there is capacity to more those with more significant mental illness further up the model into individual care.

Ethical approval

There is no ethical approval relevant to this study, as a systematic review with no human or animal involvement.

Supplementary Table 1

Download MS Word (27.6 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Vikki Langton, a research librarian at the University of Adelaide, for assistance with database searching. We also thank the authors of studies who kindly responded to our requests for additional data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

As a review, the data for this study is the papers that are included. These are fully referenced and can therefore be freely found.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2024.2343745.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Baird, M., Bimali, M., Cott, A., Brimacombe, M., Ruhland-Petty, T., & Daley, C. (2017). Methodological challenges in conducting research with refugee women. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(4), 344–351. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1291775

- Bernardi, J., Dahiya, M., & Jobson, L. (2019). Culturally modified cognitive processing therapy for Karen refugees with posttraumatic stress disorder: A pilot study. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 26(5), 531–539. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.2373

- Blignault, I., Saab, H., Woodland, L., Mannan, H., & Kaur, A. (2021). Effectiveness of a community-based group mindfulness program tailored for Arabic and Bangla-speaking migrants. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 15(1), 32–32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-021-00456-0

- Böge, K., Karnouk, C., Hahn, E., Schneider, F., Habel, U., Banaschewski, T., Meyer-Lindenberg, A., Joachim Salize, H., Kamp-Becker, I., Padberg, F., Hasan, A., Falkai, P., Rapp, M. A., Plener, P. L., Stamm, T., Elnahrawy, N., Lieb, K., Heinz, A., & Bajbouj, M. (2020). Mental health in refugees and asylum seekers (MEHIRA): Study design and methodology of a prospective multicentre randomized controlled trail investigating the effects of a stepped and collaborative care model. European Archives of Psychiatry and Clinical Neuroscience, 270(1), 95–106. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00406-019-00991-5

- Bogic, M., Njoku, A., & Priebe, S. (2015). Long-term mental health of war-refugees: A systematic literature review. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 15(1), 29–29. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-015-0064-9

- Brabender, V., Fallon, A., & Smolar, A. I. (2004). Essentials of group therapy. Wiley.

- Brassington, L., Ferreira, N. B., Yates, S., Fearn, J., Lanza, P., Kemp, K., & Gillanders, D. (2016). Better living with illness: A transdiagnostic acceptance and commitment therapy group intervention for chronic physical illness. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 5(4), 208–214. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2016.09.001

- Brochmann, H. D., Calundan, J. H. N., Carlsson, J., Poulsen, S., Sonne, C., & Palic, S. (2019). Utility of group treatment for trauma‐affected refugees in specialised outpatient clinics in Denmark: A mixed methods study of practitioners’ experiences. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 19(2), 105–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/capr.12208

- Bunn, M., Goesel, C., Kinet, M., & Ray, F. (2018). Group treatment for survivors of torture and severe violence: A literature review. Torture Journal, 26(1), 23. https://doi.org/10.7146/torture.v26i1.108062

- Byrow, Y., Pajak, R., Specker, P., & Nickerson, A. (2020). Perceptions of mental health and perceived barriers to mental health help-seeking amongst refugees: A systematic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 75, 101812–101812. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101812

- Cornish, P. (2020). Stepped care 2.0: A paradigm shift in mental health (1st ed. 2020 ed.). Springer International Publishing.

- Crumlish, N., & OʼRourke, K. (2010). A systematic review of treatments for post-traumatic stress disorder among refugees and asylum-seekers. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 198(4), 237–251. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181d61258

- Dolan, N., Simmonds‐Buckley, M., Kellett, S., Siddell, E., & Delgadillo, J. (2021). Effectiveness of stress control large group psychoeducation for anxiety and depression: Systematic review and meta‐analysis. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 60(3), 375–399. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12288

- Due, C., Green, E., & Ziersch, A. (2020). Psychological trauma and access to primary healthcare for people from refugee and asylum-seeker backgrounds: A mixed methods systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1), 71. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00404-4

- Eriksson-Sjöö, T., Cederberg, M., Östman, M., & Ekblad, S. (2012). Quality of life and health promotion intervention - a follow up study among newly-arrived Arabic-speaking refugees in Malmö, Sweden. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 8(3), 112–126. https://doi.org/10.1108/17479891211267302

- Finlayson, K. W., & Dixon, A. (2008). Qualitative meta-synthesis: A guide for the novice. Nurse Researcher, 15(2), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.7748/nr2008.01.15.2.59.c6330

- Fish, M., & Fakoussa, O. (2018). Towards culturally inclusive mental health: Learning from focus groups with those with refugee and asylum seeker status in Plymouth. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 14(4), 361–376. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-12-2017-0050

- Gerber, M. M., Callahan, J. L., Moyer, D. N., Connally, M. L., Holtz, P. M., & Janis, B. M. (2017). Nepali Bhutanese refugees reap support through community gardening. International Perspectives in Psychology: Research, Practice, Consultation, 6(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1037/ipp0000061

- Gurung, A., Subedi, P., Zhang, M., Li, C., Kelly, T., Kim, C., & Yun, K. (2020). Culturally-appropriate orientation increases the effectiveness of mental health first aid training for Bhutanese refugees: Results from a multi-state program evaluation. Journal of Immigrant & Minority Health, 22(5), 957–964. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-00986-8

- Haefner, J., Abedi, M., Morgan, S., & McFarland, M. (2019). Using a veterans affairs posttraumatic stress disorder group therapy program with refugees. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services, 57(5), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.3928/02793695-20181220-02

- Han, M., Valencia, M., Lee, Y. S., & De Leon, J. (2012). Development and implementation of the culturally competent program with Cambodians: The pilot psycho-social-cultural treatment group program. Journal of Ethnic & Cultural Diversity in Social Work, 21(3), 212–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/15313204.2012.700494

- Hartwig, K. A., & Mason, M. (2016). Community gardens for refugee and immigrant communities as a means of health promotion. Journal of Community Health, 41(6), 1153–1159. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10900-016-0195-5

- Hashimoto‐Govindasamy, L. S., & Rose, V. (2011). An ethnographic process evaluation of a community support program with Sudanese refugee women in Western Sydney. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 22(2), 107–112. https://doi.org/10.1071/HE11107

- Hong, Q. N., Fàbregues, S., Bartlett, G., Boardman, F., Cargo, M., Dagenais, P., & Pluye, P. (2018). The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Education for Information, 34(4), 285–291. https://doi.org/10.3233/EFI-180221

- Hovey, J. D., Hurtado, G., & Seligman, L. D. (2014). Findings for a CBT support group for Latina migrant farmworkers in Western Colorado. Current Psychology, 33(3), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-014-9212-y

- Husby, S. R., Carlsson, J., Mathilde Scotte Jensen, A., Glahder Lindberg, L., & Sonne, C. (2020). Prevention of trauma‐related mental health problems among refugees: A mixed‐methods evaluation of the MindSpring group programme in Denmark. Journal of Community Psychology, 48(3), 1028–1039. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.22323

- Hynie, M. (2018). The social determinants of refugee mental health in the post-migration context: A critical review. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 63(5), 297–303. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743717746666

- Im, H., & Swan, L. E. T. (2020). Capacity building for refugee mental health in resettlement: Implementation and evaluation of cross-cultural trauma-informed care training. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 22(5), 923–934. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-020-00992-w

- Jang, M., & Kim, Y.-H. (2012). The effect of group sandplay therapy on the social anxiety, loneliness and self-expression of migrant women in international marriages in South Korea. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 39(1), 38–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aip.2011.11.008

- Jarero, I., Artigas, L., Uribe, S., García, L. E., Cavazos, M. A., & Givaudan, M. (2015). Pilot research study on the provision of the EMDR integrative group treatment protocol with female cancer patients. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 9(2), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.9.2.98

- Jeon, S., Lee, J., Jun, J. Y., Park, Y. S., Cho, J., Choi, J., Jeon, Y., & Kim, S. J. (2020). The effectiveness of cognitive behavioral therapy on depressive symptoms in North Korean refugees. Psychiatry Investigation, 17(7), 681–687. https://doi.org/10.30773/pi.2019.0134

- Jiménez-Solomon, O. G., Méndez-Bustos, P., Swarbrick, M., Díaz, S., Silva, S., Kelley, M., Duke S., & Lewis-Fernández, R. (2016). Peer-supported economic empowerment: A financial wellness intervention framework for people with psychiatric disabilities. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(3), 222–233. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000210

- Kananian, S., Ayoughi, S., Farugie, A., Hinton, D., & Stangier, U. (2017). Transdiagnostic culturally adapted CBT with Farsi-speaking refugees: A pilot study. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 8(Suppl. 2), 1390362. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2017.1390362

- Kananian, S., Soltani, Y., Hinton, D., & Stangier, U. (2020). Culturally adapted cognitive behavioral therapy plus problem management (CA‐CBT+) with Afghan refugees: A randomized controlled pilot study. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 33(6), 928–938. https://doi.org/10.1002/jts.22615

- Karageorge, A., Rhodes, P., & Gray, R. (2018). Relationship and family therapy for newly resettled refugees: An interpretive description of staff experiences. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 39(3), 303–319. https://doi.org/10.1002/anzf.1325

- Lehnung, M., Shapiro, E., Schreiber, M., & Hofmann, A. (2017). Evaluating the EMDR group traumatic episode protocol with refugees: A field study. Journal of EMDR Practice and Research, 11(3), 129–138. https://doi.org/10.1891/1933-3196.11.3.129

- Lenz, S., Bruijn, B., Serman, N. S., & Bailey, L. (2014). Effectiveness of cognitive processing therapy for treating posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Mental Health Counseling, 36(4), 360–376. doi: https://doi.org/10.17744/mehc.36.4.1360805271967kvq

- Li, S. S. Y., Liddell, B. J., & Nickerson, A. (2016). The relationship between post-migration stress and psychological disorders in refugees and asylum seekers. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(9), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0723-0

- Logie, C. H., Lacombe-Duncan, A., Lee-Foon, N., Ryan, S., & Ramsay, H. (2016). “It’s for us -newcomers, LGBTQ persons, and HIV-positive persons. You feel free to be”: A qualitative study exploring social support group participation among African and Caribbean lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender newcomers and refugees in Toronto, Canada. BMC International Health and Human Rights, 16(1), 18–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12914-016-0092-0

- Luth-Hanssen, N., Fougner, M., & Debesay, J. (2020). Well-being through group exercise: Immigrant women’s experiences of a low-threshold training program. International Journal of Migration, Health and Social Care, 16(3), 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJMHSC-06-2019-0059

- Maehder, K., Löwe, B., & Weigel, A. (2018). Management of psychiatric and somatic comorbidity in primary-care-based stepped-care models: A systematic review. Journal of Psychosomatic Research, 109, 117–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychores.2018.03.095

- Methley, A. M., Campbell, S., Chew-Graham, C., McNally, R., & Cheraghi-Sohi, S. (2014). PICO, PICOS and SPIDER: A comparison study of specificity and sensitivity in three search tools for qualitative systematic reviews. BMC Health Services Research, 14(1), 579–579. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-014-0579-0

- Mitschke, D. B., Aguirre, R. T. P. & Sharma, B.(2013). Common threads: Improving the mental health of Bhutanese refugee women through shared learning. Social Work in Mental Health, 11(3), 249–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2013.769926

- Mitschke, D. B., Praetorius, R. T., Kelly, D. R., Small, E., & Kim, Y. K. (2017). Listening to refugees: How traditional mental health interventions may miss the mark. International Social Work, 60(3), 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872816648256

- Murdin, L., Balick, A., Chalfont, A., Johnson, S., Pollecoff, M., & Wilkinson, H. (2015). Managing difficult endings in psychotherapy: It’s time (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Murray, K. E., Davidson, G. R., & Schweitzer, R. D. (2010). Review of refugee mental health interventions following resettlement: Best practices and recommendations. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 576–585. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01062.x

- Naeem, F., Gul, M., Irfan, M., Munshi, T., Asif, A., Rashid, S., Khan, M. N. S., Ghani, S., Malik, A., Aslam, M., Farooq, S., Husain, N., & Ayub, M. (2015). Brief culturally adapted CBT (CaCBT) for depression: A randomized controlled trial from Pakistan. Journal of Affective Disorders, 177, 101–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.02.012

- Nilsson, H., Saboonchi, F., Gustavsson, C., Malm, A., & Gottvall, M. (2019). Trauma-afflicted refugees’ experiences of participating in physical activity and exercise treatment: A qualitative study based on focus group discussions. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1699327–1699327. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1699327

- Nosè, M., Ballette, F., Bighelli, I., Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Tol, W., & Barbui, C. (2017). Psychosocial interventions for post-traumatic stress disorder in refugees and asylum seekers resettled in high-income countries: Systematic review and meta-analysis. PLOS ONE, 12(2), e0171030–e0171030. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0171030

- Ooi, C. S., Rooney, R. M., Roberts, C., Kane, R. T., Wright, B., & Chatzisarantis, N. (2016). The efficacy of a group cognitive behavioral therapy for war-affected young migrants living in Australia: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1641–1641. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01641

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., & Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ: British Medical Journal, 372, n71. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

- Patel, N., Kellezi, B., & Williams, A. (2014). Psychological, social and welfare interventions for psychological health and well‐being of torture survivors. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009317.pub2

- Pottie, K., Greenaway, C., Feightner, J., Welch, V., Swinkels, H., Rashid, M., Narasiah, L., Kirmayer, L. J., Ueffing, E., MacDonald, N. E., Hassan, G., McNally, M., Khan, K., Buhrmann, R., Dunn, S., Dominic, A., McCarthy, A. E., Gagnon, A. J., Rousseau, C., Tugwell, P., & Coauthors of the Canadian Collaboration for Immigrant and Refugee Health. (2011). Evidence-based clinical guidelines for immigrants and refugees. Canadian Medical Association Journal (CMAJ), 183(12), E824–E925. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.090313

- Poulsen, D. V., Pálsdóttir, A. M., Christensen, S. I., Wilson, L., & Uldall, S. W. (2020). Therapeutic nature activities: A step toward the labor market for traumatized refugees. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(20), 7542. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17207542

- Praetorius, R. T., Mitschke, D. B., Avila, C. D., Kelly, D. R., & Henderson, J. (2016). Cultural integration through shared learning among resettled Bhutanese women. Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment, 26(6), 549–560. https://doi.org/10.1080/10911359.2016.1172997

- Robertson, C. L., Halcon, L., Hoffman, S. J., Osman, N., Mohamed, A., Areba, E., Savik, K., & Mathiason, M. A. (2019). Health realization community coping intervention for Somali refugee women. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, 21(5), 1077–1084. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10903-018-0804-8

- Salt, R. J., Costantino, M. E., Dotson, E. L., & Paper, B. M. (2017). “You are not alone” strategies for addressing mental health and health promotion with a refugee women’s sewing group. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(4), 337–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1289287

- Schneider, F., Bajbouj, M., & Heinz, A. (2017). Mental treatment of refugees in Germany: Model for a stepped approach. Der Nervenarzt, 88(1), 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00115-016-0243-5

- Simich, L., & Andermann, L. (2014). Refuge and resilience promoting resilience and mental health among resettled refugees and forced migrants (1st ed.). Springer Netherlands.

- Slewa-Younan, S., Guajardo, M. G. U., Mohammad, Y., Lim, H., Martinez, G., Saleh, R., & Sapucci, M. (2020). An evaluation of a mental health literacy course for Arabic speaking religious and community leaders in Australia: Effects on posttraumatic stress disorder related knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1), 69–69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00401-7

- Slewa-Younan, S., Guajardo, M. G. U., Mohammad, Y., Lim, H., Martinez, G., Saleh, R., & Sapucci, M. (2020b). An evaluation of a mental health literacy course for Arabic speaking religious and community leaders in Australia: Effects on posttraumatic stress disorder related knowledge, attitudes and help-seeking. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 14(1), 69–69. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-020-00401-7

- Slewa-Younan, S., McKenzie, M., Thomson, R., Smith, M., Mohammad, Y., & Mond, J. (2020a). Improving the mental wellbeing of Arabic speaking refugees: An evaluation of a mental health promotion program. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 314–314. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-02732-8

- Slobodin, O., & de Jong, J. T. V. M. (2015). Mental health interventions for traumatized asylum seekers and refugees: What do we know about their efficacy? International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 61(1), 17–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764014535752

- Small, E., Kim, Y. K., Praetorius, R. T., & Mitschke, D. B. (2016). Mental health treatment for resettled refugees: A comparison of three approaches. Social Work in Mental Health, 14(4), 342–359. https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2015.1080205

- Smidl, S., Mitchell, D. M., & Creighton, C. L. (2017). Outcomes of a therapeutic gardening program in a mental health recovery center. Occupational Therapy in Mental Health, 33(4), 374–385. https://doi.org/10.1080/0164212X.2017.1314207

- Spike, E. A., Smith, M. M., & Harris, M. F. (2011). Access to primary health care services by community-based asylum seekers. Medical Journal of Australia, 195(4), 188–191. https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.2011.tb03277.x

- Subedi, P., Li, C., Gurung, A., Bizune, D., Dogbey, M. C., Johnson, C. C., & Yun, K. (2015). Mental health first aid training for the Bhutanese refugee community in the United States. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 9(1), 20–20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-015-0012-z

- Tribe, R. H., Sendt, K.-V., & Tracy, D. K. (2019). A systematic review of psychosocial interventions for adult refugees and asylum seekers. Journal of Mental Health, 28(6), 662–676. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1322182

- Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Acarturk, C., Anttila, M., Au, T., Ballette, F., & Barbui, C. (2019). Efficacy and acceptability of psychosocial interventions in asylum seekers and refugees: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 28(4), 376–388. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796019000027

- Turrini, G., Purgato, M., Ballette, F., Nosè, M., Ostuzzi, G., & Barbui, C. (2017). Common mental disorders in asylum seekers and refugees: Umbrella review of prevalence and intervention studies. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 11(1), 51–51. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-017-0156-0

- United Nations High Commisioner for Refugees. (1951). Convention and protocol relating to the status of refugees. www.unhcr.org/3b66c2aa10.html

- Uphoff, E., Robertson, L., Cabieses, B., Villalón, F. J., Purgato, M., Churchill, R., & Barbui, C. (2020). An overview of systematic reviews on mental health promotion, prevention, and treatment of common mental disorders for refugees, asylum seekers, and internally displaced persons. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 2020(9). https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD013458.pub2

- van Heemstra, H. E., Scholte, W. F., Haagen, J. F. G., & Boelen, P. A. (2019). 7ROSES: A transdiagnostic intervention for promoting self-efficacy in traumatized refugees: A first quantitative evaluation. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), 1673062–1673062. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1673062

- Vannie, I.-W., & Denise, G. (2011). Group music therapy methods in cross-cultural aged care practice in Australia. Australian Journal of Music Therapy, 22, 59–80. https://doi.org/10.3316/informit.686713451144847