ABSTRACT

Objective

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) for social anxiety disorder (SAD) can be delivered through several modalities, including individually-administered CBT (ICBT), group-based CBT (GCBT), and CBT delivered remotely (RCBT). We synthesised the current literature on ICBT, GCBT, and RCBT approaches in adults with SAD, and compared their relative effectiveness using a meta-analytic approach.

Method

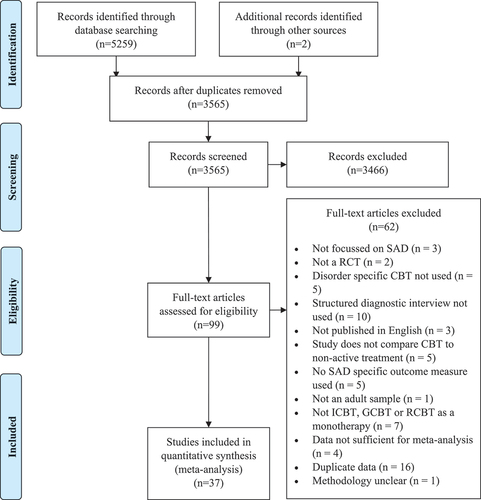

This review included randomised controlled trials comparing a disorder specific CBT monotherapy (ICBT, GCBT, or RCBT) to a non-active control group in adults with diagnosed SAD. Eligible studies were searched through PsycINFO, Scopus, and EMBASE databases to April 2023. A total of 37 studies met the inclusion criteria (with 55 between-group comparisons; N = 3234). Between-group effect sizes were conducted using random effects models.

Results

Analyses indicated that RCBT (k = 23; g = 0.90; 95% CI = 0.74–1.06) and ICBT (k = 17; g = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.66–1.23) demonstrated large effects, while GCBT demonstrated medium effects (k = 15; g = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.49–0.94). The groups, however, did not differ significantly (Q2 = 2.17, p > .05).

Conclusions

This study builds on the existing literature demonstrating the efficacy of these treatment approaches.

Key Points

What is already known about this topic:

Cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT) is an effective treatment for adults with social anxiety disorder (SAD).

CBT for SAD can be delivered using a variety of treatment approaches.

Individually-administered CBT, group-based CBT and remotely-delivered CBT are the primary treatment modalities.

What this topic adds:

This study compared the effectiveness of different CBT delivery methods.

Individually-administered CBT and remotely delivered CBT result in large effect sizes, while group-based CBT results in medium effect sizes.

Individually-administered CBT, group-based CBT and remotely-delivered CBT can be delivered with equal confidence based on client preference.

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is characterised by an intense fear of negative evaluation (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). This fear results in an individual avoiding feared situations or enduring them with intense anxiety/distress (American Psychiatric Association, Citation2022). The lifetime prevalence of SAD is estimated to be approximately 11% and most individuals tend to develop SAD during adolescence (Kessler et al., Citation2012). The course of SAD is often chronic (Keller, Citation2006) and it has high levels of comorbidity (Ruscio et al., Citation2008). Symptoms of SAD can significantly reduce quality of life (Kroenke et al., Citation2007; Ruscio et al., Citation2008) and SAD results in a considerable social and economic burden (Dams et al., Citation2017; Stuhldreher et al., Citation2014). Symptoms of SAD are generally under-recognised and under-treated with psychological interventions (Kroenke et al., Citation2007; Ruscio et al., Citation2008).

Multiple meta-analyses now demonstrate the efficacy of cognitive-behaviour therapy (CBT) for SAD (Carpenter et al., Citation2018; Mayo-Wilson et al., Citation2014). This treatment has also been shown to be effective in routine care (i.e., effectiveness studies) (Hans & Hiller, Citation2013). CBT for SAD typically involves cognitive interventions, such as cognitive restructuring or behavioural experiments to address maladaptive thinking and/or behavioural interventions such as exposure to reduce avoidance behaviours (Stein & Stein, Citation2008). CBT for SAD has also been shown to be durable (Kindred et al., Citation2022). As a result, CBT is recommended as a first line treatment for SAD in various clinical practice guidelines including the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE, Citation2013) and Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists (Andrews, Bell, et al., Citation2018).

Despite the demonstrated efficacy and effectiveness of CBT for SAD across multiple treatment formats, there is significant variability in the delivery of the interventions provided across the literature. These different treatment formats can be broadly classified into three categories: 1) individual face-to-face CBT (ICBT), where a single therapist provides treatment to a single client within the same therapy office; 2) group face-to-face CBT (GCBT), where multiple clients are treated simultaneously by one or more therapists; and 3) remote CBT (RCBT) modalities, where the intervention is provided without the client and the therapist being physically present in the same room. This may include internet-delivered CBT, bibliotherapy-delivered CBT, or videoconferencing delivered CBT.

Each of the treatment approaches have obvious advantages and disadvantages. For example, ICBT arguably has the strongest research base, and reflecting this ICBT is recommended as the first line treatment approach for SAD in the NICE guidelines (NICE, Citation2013). This approach has demonstrated large pooled effect sizes in meta-analytic studies (Mayo-Wilson et al., Citation2014). The main limitation of ICBT is that it is costly to deliver in terms of therapist time, often requiring 12–16 sessions with the therapist (Mörtberg et al., Citation2007).

GCBT offers potentially a more cost-effective approach when compared with ICBT given multiple clients can be treated simultaneously. Given that a large part of the treatment for SAD involves exposure to social settings, GCBT may also have positive therapeutic benefits. GCBT has considerable empirical support, demonstrating large pooled effects (Mayo-Wilson et al., Citation2014). However, despite the demonstrated efficacy of GCBT for SAD, this treatment approach is not currently recommended by the NICE guidelines as a first line treatment for SAD (NICE, Citation2013). There is also some research to indicate that GCBT is less clinically effective than ICBT (Stangier et al., Citation2003). This may be because group-based treatments are seen as less acceptable to participants than other treatment modalities (Black et al., Citation2023) or due to the potential for less therapist time with each group participant in group-based treatments.

Remote treatment can be delivered in either a high intensity or low-intensity format. High intensity remote interventions are analogous to standard face-to-face treatment and provide interventions in real time, using either video-conferencing or the telephone to conduct the session. Several small-scale studies have demonstrated that CBT for SAD can be delivered effectively using this treatment methodology (Matsumoto et al., Citation2018; Yuen et al., Citation2013). While this format of intervention overcomes many of the barriers that individuals face when trying to access CBT interventions, it is similar to ICBT in terms of cost of delivery.

Low intensity remote interventions provide the patient with standardised, largely self-help materials, which are often supplemented with asynchronous clinician support. This clinician support is generally provided via email, telephone, or text messaging services. Several meta-analyses have now examined the efficacy of low intensity remote treatments for SAD and have demonstrated large effect sizes (Andrews, Basu, et al., Citation2018; Kampmann, Emmelkamp, & Morina, Citation2016). Other studies have demonstrated that such interventions are equivalent to ICBT for SAD (Andrews et al., Citation2011; Botella et al., Citation2010), and have high levels of acceptability (Aydos et al., Citation2009; Dear et al., Citation2016). While such interventions can be costly to set up (Klein et al., Citation2011), once established the intervention can be widely disseminated as part of routine care (Titov et al., Citation2020). Given that the majority of the intervention is automated, it is thus standardised, and may protect against therapist drift (Speers et al., Citation2022; Waller & Turner, Citation2016). However, this treatment modality may be affected by client motivation due to the largely self-help nature of the intervention.

A meta-analysis by Mayo-Wilson et al. (Citation2014) examined the pooled efficacy of various pharmacological and psychological interventions for SAD including individual, group, and remote treatment modalities. They found large effect sizes for ICBT (g = 1.19), GCBT (g = 0.92) and RCBT treatments with support (g = 0.86), and a moderate effect size for RCBT treatment without support (g = 0.75). While this is an important contribution to the literature there are a number of important limitations to this study. First, this meta-analysis included studies that did not confirm SAD with a structured diagnostic interview, thus results may not be generalisable to those with SAD. Second, much research, including studies with large sample sizes (Boettcher et al., Citation2018; Clark et al., Citation2023; Neufeld et al., Citation2020) have been published since this 2014 meta-analysis was conducted, and thus an update based on this new literature is required. Third, Mayo-Wilson et al. (Citation2014), did not examine moderators of treatment outcome across the different CBT modalities. Given the limitations of the existing literature, the aim of the current review was to evaluate the effectiveness of CBT for SAD by examining the relative pooled effect sizes for the three primary treatment modalities of CBT for SAD (ICBT, GCBT, and RCBT). A secondary aim was to examine potential exploratory moderators of treatment outcome. We examined a range of moderators, including year of publication, mean age of the sample, proportion of female participants in the sample, treatment duration, type of data analysis (intention-to-treat or completer analysis), risk of bias and type of guidance (clinician-guided or self-guided) in RCBT interventions. We anticipate that the findings from this review might assist in treatment planning of adults with SAD.

Method

Design and search strategy

Relevant studies were identified through PsycINFO, Scopus and EMBASE databases. The search terms used were “cognitive therap*” OR “behavio* therap*” OR “cognitive behavior* therap*” OR “cbt” OR “treatment” AND “social anxiety” OR “social phobia” AND “rct” OR “randomi* control* trial” OR “trial”. See Supplementary Table 1 for search terms used in each database. The reference list of each study that met all screening criteria were examined to identify other potentially relevant studies and no other references were examined. The initial search was conducted in 2018 by author [MH]. Another author [BW] updated the search on 24 April 2023. No unpublished data were included in this study. There were no limitations placed on the search. The review was not pre-registered and a review protocol was not prepared. The PRISMA checklist is outlined in Supplementary Table 2.

Selection criteria

Eligible studies were required to satisfy the following criteria: 1) a study published in a peer reviewed journal; 2) the study must be a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing a disorder-specific CBT treatment to a non-active control group (i.e., waitlist control groups); 3) participants required a primary diagnosis of SAD confirmed by a semi-structured or structured diagnostic interview; 4) the study must be published in the English language; 5) the study must use cognitive and/or behavioural interventions and at a minimum challenge maladaptive thoughts and/or use an exposure-based intervention; 6) the study must use a SAD specific severity scale as a primary outcome measure (see below) and report outcomes for individuals with SAD vs. other psychiatric disorders separately; 7) participants were all aged at least 18 years of age and the sample targeted the general adult population rather than specific subgroups of adults (i.e., young adults or older adults); 8) the intervention must be solely ICBT, GCBT or RCBT rather a combination of different approaches; and 9) means, standard deviations and sample sizes, for pre- and post-intervention for all groups, were reported.

When studies did not specify a primary outcome measure or had multiple primary outcome measures, data from the clinician administered Liebowitz Social Anxiety Scale (LSAS; Liebowitz, Citation1987); were extracted where possible, followed by the self-report version of the LSAS if the clinician-administered version was not available. If either version of the LSAS was not available, then data from other outcome measures, such as the Social Interaction Anxiety Scale (SIAS; Mattick & Clarke, Citation1998), the Brief Social Phobia Scale (Davidson et al., Citation1997), the Fear of Negative Evaluation scale (Weeks et al., Citation2005), and/or Social Avoidance and Distress Scale (Watson & Friend, Citation1969) were extracted.

Data collection and analysis

Studies were extracted from the relevant database to Endnote and then exported to a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet where results from each database were combined, duplicates were identified and removed, and studies were screened against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The final search was conducted by the last author (BW) with 10% of the entries reviewed at title/abstract and full text stages by another author (NB). Any discrepancies were resolved via discussion; inter-rater reliability analyses were not conducted. Data were extracted into a developed Excel spreadsheet for a range of categories, including (i) Author name and year of publication, (ii) Country that the study was conducted in, (iii) number of active treatment groups. (iv) treatment modality (ICBT, GCBT, RCBT), (v) number of participants, (vi) primary outcome measure, (vii) mean age of sample, (viii) percentage of females in the sample, (ix) type of control group used, (x) duration of treatment (in weeks), type of analysis (intention to treat or completer analysis), and (xi) outcome data (i.e., post-treatment means and standard deviations, standard difference in means, or effect sizes). All extracted data were independently checked by a second author.

Effect size data were analysed with Comprehensive Meta-Analysis Version 3.0 (Borenstein et al., Citation2013). Between-group analyses were conducted using random effects models and intention-to-treat data were used wherever possible. Between-group analyses are comparisons between the two groups at a particular time-point (i.e., post-treatment). To obtain between-groups effect sizes, it was necessary to first compute Cohen’s d, this was subsequently converted to Hedge’s g via the correction factor J. This conversion is used to control for the overestimation of the population parameter in smaller sample sizes that occurs with effect size estimates using Cohen’s d (Borenstein et al., Citation2009). Effect sizes are interpreted as 0.2 (small effect), 0.5 (medium effect), and 0.8 (large effect) (Cohen, Citation1988). Larger g values correspond to greater overall treatment effect. The between-group effect was firstly calculated for all the CBT studies, the treatment type (ICBT, GCBT, RCBT) was then examined as a moderator. Where there were two or more active treatment groups in an included study, the between-group effect size was calculated for each active group using the same waitlist control group as the comparator.

The Q test and I2 statistic were used to identify and evaluate the significance of heterogeneity within the dataset, respectively. A significant Q test indicates the presence of heterogeneity, while I2 quantifies how much heterogeneity is present. I2 values up to 25% indicate low, 50% moderate, and 75% or greater indicate high heterogeneity, respectively (Higgins et al., Citation2003). Publication bias was assessed using Egger’s regression intercept (Egger et al., Citation1997) and Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method (Duval & Tweedie, Citation2000), which removes the most extreme studies by substituting a mirror-image that yields an unbiased estimate of effect size generated by the dataset (Borenstein et al., Citation2009). The “one-study removed” method was used to analyse the impact of each study on the summary effect; this method systematically removes one study and re-computes the analysis to examine the change in overall effect size caused by each study.

Moderator analyses were conducted for each modality separately. Continuous moderators included year of publication, mean age in study, percentage female participants in the study, and treatment duration (in weeks), and were examined using meta-regression. In the analyses for treatment duration, studies that did not used a fixed number were excluded. Categorical moderators included data analysis type (i.e., intention to treat or completer), and study risk of bias, and were examined by exploring group differences based on the Q statistic. Type of guidance (clinician-guided or self-guided) was also examined in the RCBT moderator analyses.

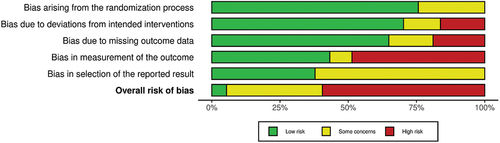

Risk of Bias

Risk of bias (RoB) was assessed with the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool for randomised controlled trials (Version 2) (Sterne et al., Citation2019). The RoB tool assesses bias associated with 1) the randomisation process, 2) deviations from the intended intervention, 3) missing data, 4) measurement of outcome, and 5) selection of the reported results. Only part 2 of Domain 2 was rated given it is generally impossible to blind treatment conditions in psychological studies. RoB was assessed by the last author (BW) and 10% were co-rated by another author (KM). Any discrepancies were resolved through discussion.

Results

Study selection

The initial search yielded 5259 studies and two additional records were identified through reference list searches of included studies (N = 5261). The 5261 studies were examined for duplicates, and 1695 were removed following which, abstracts of 3563 were reviewed and 3466 studies were excluded. This left 99 studies for full text review, following which 37 studies met inclusion criteria and were included in the meta-analysis. The PRISMA flow diagram is outlined in .

Study characteristics

Details of all included studies are outlined in . Thirty-seven studies (with 55 between-group comparisons) comprising a total of 3234 participants (n = 2057 in treatment groups and n = 1177 in control groups) were included in the final analysis. On average, participants were aged in their early thirties [mean age range was 24.92 years (Wang et al., Citation2020) to 46.57 years (Newman et al., Citation1994)]. The majority of the sample was female [range 35% (Alden & Taylor, Citation2011) to 82% (Botella et al., Citation2010)]. There were 17 ICBT treatment conditions, 15 GCBT treatment conditions, and 23 RCBT conditions included in the study. All control groups consisted of waitlist controls. RCBT conditions primarily included internet-delivered CBT (18/23; 78.26%), as well as bibliotherapy-administered CBT (3/23; 13.04); application-delivered CBT (1/23; 4.35%) and mixed remote CBT methodologies 1/23; 4.35%). 15/23 (65.22%) of these interventions were delivered with some clinician-guidance and 8/23 (34.78) were self-guided interventions.

Table 1. Characteristics of included studies.

Risk of bias

The risk of bias (RoB) assessment for each study is outlined in Supplement 3. A summary of the RoB assessment is outlined in . For Domain 1 (randomisation process), Domain 2 (deviations from the intended intervention) and Domain 3 (missing data), the majority of studies were classified as “low risk”. For Domain 4 (measurement of outcome), there was a roughly equal number of “low risk” (43.24%) and “high risk” (48.65%) studies. For Domain 5 (selection of the reported results), none of the studies were classified as “high risk”, and as such was a strength of these included studies. Overall, 2/37 studies (5.41%) were classified as “low risk” of bias, 13/37 studies (35.14%) were classified as having “some concerns”, and 22/37 studies (59.46%) were classified as “high risk”.

Meta-analytic findings

provides a summary of meta-analytical results and findings for each treatment comparison are described below:

Table 2. Summary of meta-analytic results.

CBT vs. control

The pooled between-group effect size for all CBT interventions was large at post-treatment (k = 55; g = 0.87; 95% CI = 0.75 to 0.99). The Q statistic was significant (p < .01) and heterogeneity was moderate across studies (I2 = 67.35), indicating significant variability in outcomes between the studies. Sensitivity analyses using the one-study removed method indicated the outcome was robust. Egger’s regression test indicated no issues with publication bias (t = 1.62, df = 53, p > .05) and no studies were trimmed from the analysis using Duval and Tweedie’s trim and fill method.

The pooled effect sizes at post-treatment for each type of intervention (ICBT, GCBT, and RCBT) are noted in the following sections. The difference between each type of intervention was not statistically significant (Q2 = 2.17, p > .05), indicating that each of the pooled effects did not differ statistically. The funnel plot is outlined in .

ICBT vs. control

The pooled between-group effect size for ICBT interventions was large at post-treatment (k = 17; g = 0.95; 95% CI = 0.66 to 1.23). The Q statistic was significant (p< .01) and heterogeneity was high across studies (I2 = 77.55), which indicates significant variability in outcomes between the studies. Sensitivity analyses using the one-study removed method indicated the outcome was robust. Egger’s regression test indicated no issues with publication bias (t = 0.62, df = 15, p > .05) and no studies were trimmed from the analysis.

Meta-regression analyses indicated that the mean age of the sample was a significant predictor of between-group treatment effects at post-treatment (k = 16; Q(1) = 5.80, p = 0.016), with those with older samples having a smaller between-group effect size. There was also a significant difference in the between-group effect sizes depending on the risk of bias classification (Q2 = 24.429, p < .001). “Low risk” studies had the highest effect size (k = 1; g = 2.36; 95% CI: 1.792–2.923), followed by those with “some concerns” (k = 8; g = 0.95; 95% CI: 0.602–1.301), and “high risk” studies (k = 8; g = 0.73; 95% CI: 0.406–1.061).

Year of publication (k = 17; Q(1) = 1.21, p = 0.272), percentage of female participants (k = 16; Q(1) = 0.15, p = 0.695), treatment duration (k = 16; Q(1) = 0.02, p = 0.896) and data type (Q1 = 0.830, p = .362) did not moderate ICBT outcomes.

GCBT vs. control

The pooled between-group effect size at post-treatment for GCBT was medium at post-treatment (k = 15; g = 0.71; 95% CI = 0.49 to 0.94). The Q statistic was significant (p = .02) and heterogeneity was moderate across studies (I2 = 49.45), which indicates moderate variation in outcomes between the included studies. Sensitivity analyses using the one-study removed method indicated the outcome was robust. Egger’s regression test indicated no issues with publication bias (t = 0.22, df = 13, p > .05), and no studies were trimmed from the analysis.

Meta-regression analyses indicated that the mean age of the sample was a significant predictor of between-group treatment effects at post-treatment (k = 14; Q(1) = 4.48, p = 0.034), with those with older samples having a smaller between group effect size. Year of publication (k = 15; Q(1) = 1.64, p = 0.201), percentage of female participants (k = 14; Q(1) = 2.53, p = 0.112), treatment duration (k = 15; Q(1) = 1.63, p = 0.201), data type (Q1 = 2.177, p = .140), and risk of bias classification (Q1 = 0.121, p = .728) did not moderate GCBT outcomes.

RCBT vs. control

The pooled between-group effect size at post-treatment for RCBT was large at post-treatment (k = 23; g = 0.90; 95% CI = 0.74 to 1.06). The Q statistic was significant (p < .01), and heterogeneity was moderate across studies (I2 = 65.15), which indicates some variation in outcome between the included studies. Sensitivity analyses using the one-study removed method indicated the outcome was robust. Egger’s regression test indicated some potential issues with publication bias (t = 3.43, df = 21, p = .001); however, no studies were trimmed from the analysis.

Meta-regression analyses indicated that the duration of treatment was a significant predictor of between-group treatment effects at post-treatment (k = 22; Q(1) = 4.91, p = 0.027), with those with longer durations having a larger between group effect size. There was also a significant difference between the two data types (Q1 = 5.796, p = .016) with those using an intention-to-treat approach having a larger between-group effect size (k = 16; g = 0.99; 95% CI: 0.775–1.211) than the studies using a completer analysis (k = 7; g = 0.67; 95% CI: 0.512–0.819). Additionally, there was a significant difference between the risk of bias levels (Q2 = 37.713, p < .001). “Low risk” studies had the highest effect size (k = 2; g = 2.24; 95% CI: 01.788–2.684), followed by those with “some concerns” (k = 4; g = 0.80; 95% CI: 0.538–1.055), and “high risk” studies (k = 17; g = 0.79; 95% CI: 0.659–0.912). Finally, there was a significant difference between the guidance levels with those studies using clinician-guided interventions having a larger between-group effect size (k = 15; g = 1.08; 95% CI: 0.864–1.295) than those using self-guided interventions (k = 8; g = 0.60; 95% CI: 0.467–0.740) (Q1 = 13.383, p < .001). Year of publication (k = 23; Q(1) = 3.50, p = 0.061), mean age of the sample (k = 19; Q(1) = 0.02, p = 0.889) and percentage of female participants (k = 21; Q(1) = 0.72, p = 0.396) did not moderate treatment outcomes.

Discussion

This review study synthesised the available literature and conducted a meta-analysis to examine the effectiveness of different CBT modalities (ICBT, GCBT, and RCBT) for adults with SAD. The overall analysis indicated that CBT is a highly efficacious treatment, producing large between-group effect sizes at post-treatment when compared with a waitlist control. The present study found large effect sizes for the ICBT and RCBT studies, and a medium effect size for GCBT studies, albeit the differences between each intervention type were not statistically significant. The magnitude of effect sizes in the current study are largely consistent with the existing literature (Mayo-Wilson et al., Citation2014), however with a few notable exceptions, as discussed below.

First, the pooled effect for GCBT was smaller in the current study (g = 0.71) compared with the Mayo-Wilson et al. (Citation2014) study, which found a pooled effect of g = 0.92. A smaller effect size for GCBT treatment compared to ICBT treatments is consistent with studies demonstrating that ICBT outperforms GCBT (Stangier et al., Citation2003), and further controlled studies comparing the two approaches are needed to ensure individuals with SAD receive the most efficacious treatment. This is also important as recent research has found that GCBT is less acceptable to patients with SAD than either ICBT or RCBT (Black et al., Citation2023).

Second, the pooled effect for RCBT interventions (g = 0.90) was slightly larger than the effect sizes found in the Mayo-Wilson et al. (Citation2014) study (g = 0.75 without clinician support and g = 0.86 with clinician support). In the current study, moderator analyses for clinician guidance were significant and indicated that clinician-guided interventions were more effective (g = 1.08) compared with self-guided interventions (g = 0.60). This finding is consistent with a recent meta-analysis of studies comparing clinician-guided and self-guided interventions for a variety of mental health disorders (Oey et al., Citation2023), however, this study also found that the differences were no longer significant at follow-up (Oey et al., Citation2023). Given these findings, it is important to examine the relative effect sizes of clinician-guided and self-guided treatments in controlled trial with longer follow-up periods.

The current study also has important implications for current SAD treatment guidelines. For example, the United Kingdom’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidelines currently do not encourage the use of remote treatment unless there is a significant face-to-face component (NICE, Citation2013). The results of our study highlight that RCBT approaches may be a helpful initial treatment for SAD, as long as the remote service has initially undergone significant evaluation, and potentially that the intervention includes some level of clinician support. The current study also indicated that duration was a significant predictor of outcome in RCBT interventions, with longer interventions having better outcomes. Reflecting this, it is possible that current treatment guidelines for SAD may require updating. However, it is also important to examine optimal length of treatment in future studies in order to inform treatment planning.

While the current study adds to the existing literature and provides a contemporary analysis of the effectiveness of various CBT modalities for adults with SAD, it is important to consider these results in light of several limitations. First, the original search for this study was conducted in 2018, which is prior to the widespread pre-registration of meta-analytic studies. Thus, for this reason the study was not pre-registered. Second, unpublished research was not included in this study, potentially increasing the risk of publication bias and influencing overall interpretability study outcomes. However, publication bias was assessed in the present study, therefore, minimising the potential risk of any publication bias caused by not including unpublished research. Third, in order to compare ICBT, RCBT and GCBT equally, this study only included RCTs that used a waitlist “passive” control group. Future research could include RCTs with active control groups and also limit the included studies to those with lower risk of bias. Finally, some of the moderator analyses were underpowered and these findings should be interpreted with caution. The moderator analyses were exploratory and thus a more conservative p-value was not used. Future research could replicate the present findings and use a more stringent p-value (i.e., <0.01).

This present review builds on the current body of literature examining the relative comparability of three CBT modalities in the treatment of adults with SAD. It was found that compared to control conditions, ICBT and RCBT result in large treatment effects, while GCBT results in medium treatment effects. It is therefore recommended for future research to continue building on the evidence base through examining the comparative effectiveness of RCBT, ICBT, and GCBT in the treatment of individuals with SAD. In particular, controlled trials comparing the various treatment approaches are urgently required. Future research investigating who responds best to each type of treatment might assist health care providers in the delivery of evidence-based treatment for SAD in the most cost-efficient way.

Supplemental Material 1 Search terms

Download MS Word (15.4 KB)Supplemental Material 2 PRISMA checklist

Download MS Word (21.1 KB)Supplemental Material 3 Risk of Bias Assessment

Download MS Word (27 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed at https://doi.org/10.1080/00050067.2024.2356804.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alden, L. E., & Taylor, C. T. (2011). Relational treatment strategies increase social approach behaviors in patients with generalized social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 25(3), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2010.10.003

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th Text Revision ed.).

- Anderson, P. L., Price, M., Edwards, S. M., Obasaju, M. A., Schmertz, S. K., Zimand, E., & Calamaras, M. R. (2013). Virtual reality exposure therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(5), 751–760. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033559

- Andrews, G., Basu, A., Cuijpers, P., Craske, M. G., McEvoy, P., English, C. L., & Newby, J. M. (2018). Computer therapy for the anxiety and depression disorders is effective, acceptable and practical health care: An updated meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 55, 70–78. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2018.01.001

- Andrews, G., Bell, C., Boyce, P., Gale, C., Lampe, L., Marwat, O., Rapee, R., & Wilkins, G. (2018). Royal Australian and New Zealand college of psychiatrists clinical practice guidelines for the treatment of panic disorder, social anxiety disorder and generalised anxiety disorder. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(12), 1109–1172. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867418799453

- Andrews, G., Davies, M., & Titov, N. (2011). Effectiveness randomized controlled trial of face to face versus Internet cognitive behaviour therapy for social phobia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 45(4), 337–340. https://doi.org/10.3109/00048674.2010.538840

- Aydos, L., Titov, N., & Andrews, G. (2009). Shyness 5: The clinical effectiveness of Internet-based clinician-assisted treatment of social phobia. Australasian Psychiatry, 17(6), 488–492. https://doi.org/10.1080/10398560903284943

- Beidel, D. C., Alfano, C. A., Kofler, M. J., Rao, P. A., Scharfstein, L., & Wong Sarver, N. (2014). The impact of social skills training for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 28(8), 908–918. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2014.09.016

- Bell, C. J., Colhoun, H. C., Carter, F. A., & Frampton, C. M. (2012). Effectiveness of computerised cognitive behaviour therapy for anxiety disorders in secondary care. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 46(7), 630–640. https://doi.org/10.1177/0004867412437345

- Berger, T., Hohl, E., & Caspar, F. (2009). Internet-based treatment for social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(10), 1021–1035. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20603

- Black, J. A., Paparo, J., & Wootton, B. M. (2023). A preliminary examination of treatment barriers, preferences, and histories of women with symptoms of social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Change, 40(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1017/bec.2022.26

- Boettcher, J., Magnusson, K., Marklund, A., Berglund, E., Blomdahl, R., Braun, U., Delin, L., Lundén, C., Sjöblom, K., Sommer, D., von Weber, K., Andersson, G., & Carlbring, P. (2018). Adding a smartphone app to internet-based self-help for social anxiety: A randomized controlled trial. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 98–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2018.04.052

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., & Higgins, J. P. (2009). Introduction to meta analysis. Wiley.

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L., Higgins, J., & Rotherstein, H. (2013). Comprehensive meta-analysis (Version 3.0). Biostat Inc.

- Botella, C., Gallego, M. J., Garcia-Palacios, A., Guillen, V., Baños, R. M., Quero, S., & Alcañiz, M. (2010). An internet-based self-help treatment for fear of public speaking: A controlled trial. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 13(4), 407–421. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2009.0224

- Bouchard, S., Dumoulin, S., Robillard, G., Guitard, T., Klinger, E., Forget, H., Loranger, C., & Roucaut, F. X. (2017). Virtual reality compared with in vivo exposure in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A three-arm randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 210(4), 276–283. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.184234

- Caetano, K. A. S., Depreeuw, B., Papenfuss, I., Curtiss, J., Langwerden, R. J., Hofmann, S. G., & Neufeld, C. B. (2018). Trial-based cognitive therapy: Efficacy of a new CBT approach for treating social anxiety disorder with comorbid depression. International Journal of Cognitive Therapy, 11(3), 325–342. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41811-018-0028-7

- Carlbring, P., Gunnarsdóttir, M., Hedensjö, L., Andersson, G., Ekselius, L., & Furmark, T. (2007). Treatment of social phobia: Randomised trial of internet-delivered cognitive-behavioural therapy with telephone support. British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(2), 123–128. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020107

- Carpenter, J. K., Andrews, L. A., Witcraft, S. M., Powers, M. B., Smits, J. A. J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2018). Cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety and related disorders: A meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Depression and Anxiety, 35(6), 481–591. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.22728

- Clark, D. M., Ehlers, A., Hackmann, A., McManus, F., Fennell, M., Grey, N., Waddington, L., & Wild, J. (2006). Cognitive therapy versus exposure and applied relaxation in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 74(3), 568–578. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.74.3.568

- Clark, D. M., Wild, J., Warnock-Parkes, E., Stott, R., Grey, N., Thew, G., & Ehlers, A. (2023). More than doubling the clinical benefit of each hour of therapist time: A randomised controlled trial of internet cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder. Psychological Medicine, 53(11), 5022–5032. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291722002008

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2nd ed. ed.). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Connor, K. M., Davidson, J. R. T., Erik Churchill, L., Sherwood, A., Weisler, E., & Foa, R. H. (2000). Psychometric properties of the social phobia inventory (SPIN). New self- rating scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 176(4), 379–386. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.176.4.379

- Dams, J., König, H. H., Bleibler, F., Hoyer, J., Wiltink, J., Beutel, M. E., Salzer, S., Herpertz, S., Willutzki, U., Strauß, B., Leibing, E., Leichsenring, F., & Konnopka, A. (2017). Excess costs of social anxiety disorder in Germany. Journal of Affective Disorders, 213, 23–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2017.01.041

- Davidson, J. R. T., Miner, C. M., De Veaugh-Geiss, J., Tupler, L. A., Colket, J. T., & Potts, N. L. S. (1997). The brief social phobia scale: A psychometric evaluation. Psychological Medicine, 27(1), 161–166. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291796004217

- Dear, B. F., Staples, L. G., Terides, M. D., Fogliati, V. J., Sheehan, J., Johnston, L., Kayrouz, R., Dear, R., McEvoy, P. M., & Titov, N. (2016). Transdiagnostic versus disorder-specific and clinician-guided versus self-guided internet-delivered treatment for social anxiety disorder and comorbid disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 42, 30–44. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.05.004

- Duval, S., & Tweedie, R. (2000). A nonparametric “trim and fill” method of accounting for publication bias in meta-analysis. Journal of the American Statistical Association, 95(449), 89–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/01621459.2000.10473905

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. British Medical Journal, 315(7109), 629–634. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

- Furmark, T., Carlbring, P., Hedman, E., Sonnenstein, A., Clevberger, P., Bohman, B., Eriksson, A., Hållén, A., Frykman, M., Holmström, A., Sparthan, E., Tillfors, M., Ihrfelt, E. N., Spak, M., Eriksson, A., Ekselius, L., & Andersson, G. (2009). Guided and unguided self-help for social anxiety disorder: Randomised controlled trial. British Journal of Psychiatry, 195(5), 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.108.060996

- Goldin, P. R., Morrison, A., Jazaieri, H., Brozovich, F., Heimberg, R., & Gross, J. J. (2016). Group CBT versus MBSR for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 84(5), 427–437. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000092

- Goldin, P. R., Ziv, M., Jazaieri, H., Werner, K., Kraemer, H., Heimberg, R. G., & Gross, J. J. (2012). Cognitive reappraisal self-efficacy mediates the effects of individual cognitive-behavioral therapy for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 80(6), 1034–1040. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0028555

- Gruber, K., Moran, P. J., Roth, W. T., & Taylor, C. B. (2001). Computer-assisted cognitive behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behavior Therapy, 32(1), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(01)80050-2

- Hans, E., & Hiller, W. (2013). A meta-analysis of non-randomized studies on outpatient cognitive behavioral therapy for adult anxiety disorders. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(8), 954–964. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2013.07.003

- Härtling, S., Klotsche, J., Heinrich, A., & Hoyer, J. (2016). Cognitive therapy and task concentration training applied as intensified group therapies for social anxiety disorder with fear of blushing—A randomized controlled trial. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 23(6), 509–522. https://doi.org/10.1002/cpp.1975

- Higgins, J. P. T., Thompson, S. G., Deeks, J. J., & Altman, D. G. (2003). Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. British Medical Journal, 327(7414), 557–560. https://doi.org/10.1136/BMJ.327.7414.557

- Hope, D. A., Heimberg, R. G., & Bruch, M. A. (1995). Dismantling cognitive-behavioral group therapy for social phobia. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 33(6), 637–650. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7967(95)00013-N

- Kählke, F., Berger, T., Schulz, A., Baumeister, H., Berking, M., Auerbach, R. P., Bruffaerts, R., Cuijpers, P., Kessler, R. C., & Ebert, D. D. (2019). Efficacy of an unguided internet-based self-help intervention for social anxiety disorder in university students: A randomized controlled trial. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 28(2), Article e1766. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1766

- Kampmann, I. L., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., Hartanto, D., Brinkman, W. P., Zijlstra, B. J. H., & Morina, N. (2016). Exposure to virtual social interactions in the treatment of social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 147–156. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.016

- Kampmann, I. L., Emmelkamp, P. M. G., & Morina, N. (2016). Meta-analysis of technology-assisted interventions for social anxiety disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 42, 71–84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.06.007

- Keller, M. B. (2006). Social anxiety disorder clinical course and outcome: Review of Harvard/Brown Anxiety Research Project (HARP) findings. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 67(Suppl. 12), 14–19. http://www.scopus.com/inward/record.url?eid=2-s2.0-33751549949&partnerID=40&md5=9c91c7832170e2d091d3af066b2d23b4

- Kessler, R. C., Petukhova, M., Sampson, N. A., Zaslavsky, A. M., & Wittchen, H. U. (2012). Twelve-month and lifetime prevalence and lifetime morbid risk of anxiety and mood disorders in the United States. International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research, 21(3), 169–184. https://doi.org/10.1002/mpr.1359

- Kindred, R., Bates, G. W., & McBride, N. L. (2022). Long-term outcomes of cognitive behavioural therapy for social anxiety disorder: A meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 92, Article 102640. 102640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2022.102640

- Klein, B., Meyer, D., Austin, D. W., & Kyrios, M. (2011). Anxiety online-A virtual clinic: Preliminary outcomes following completion of five fully automated treatment programs for anxiety disorders and symptoms. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 13(4), Article e89. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.1918

- Kocovski, N. L., Fleming, J. E., Hawley, L. L., Huta, V., & Antony, M. M. (2013). Mindfulness and acceptance-based group therapy versus traditional cognitive behavioral group therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 51(12), 889–898. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2013.10.007

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R. L., Williams, J. B. W., Monahan, P. O., & Löwe, B. (2007). Anxiety disorders in primary care: Prevalence, impairment, comorbidity, and detection. Annals of Internal Medicine, 146(5), 317–325. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-146-5-200703060-00004

- Leary, M. R. (1983). A brief version of the fear of negative evaluation scale. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 9(3), 371–375. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167283093007

- Ledley, D. R., Heimberg, R. G., Hope, D. A., Hayes, S. A., Zaider, T. I., Dyke, M. V., Turk, C. L., Kraus, C., & Fresco, D. M. (2009). Efficacy of a manualized and workbook-driven individual treatment for social anxiety disorder. Behavior Therapy, 40(4), 414–424. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2008.12.001

- Leichsenring, F., Salzer, S., Beutel, M. E., Herpertz, S., Hiller, W., Hoyer, J., Huesing, J., Joraschky, P., Nolting, B., Poehlmann, K., Ritter, V., Stangier, U., Strauss, B., Stuhldreher, N., Tefikow, S., Teismann, T., Willutzki, U., Wiltink, J., & Leibing, E. (2013). Psychodynamic therapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy in social anxiety disorder: A multicenter randomized controlled trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(7), 759–767. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2013.12081125

- Liebowitz, M. R. (1987). Social phobia. Modern Problems of Pharmacopsychiatry, 22, 141–173. https://doi.org/10.1159/000414022

- Matsumoto, K., Sutoh, C., Asano, K., Seki, Y., Urao, Y., Yokoo, M., Takanashi, R., Yoshida, T., Tanaka, M., Noguchi, R., Nagata, S., Oshiro, K., Numata, N., Hirose, M., Yoshimura, K., Nagai, K., Sato, Y., Kishimoto, T., Nakagawa, A., & Shimizu, E. (2018). Internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy with real-time therapist support via videoconference for patients with obsessive-compulsive disorder, panic disorder, and social anxiety disorder: Pilot single-arm trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(12), e12091. https://doi.org/10.2196/12091

- Mattick, R. P., & Clarke, J. C. (1998). Development and validation of measures of social phobia scrutiny fear and social interaction anxiety. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 36(4), 455–470. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(97)10031-6

- Mattick, R. P., Peters, L., & Clarke, J. C. (1989). Exposure and cognitive restructuring for social phobia: A controlled study. Behavior Therapy, 20(1), 3–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(89)80115-7

- Mayo-Wilson, E., Dias, S., Mavranezouli, I., Kew, K., Clark, D. M., Ades, A. E., & Pilling, S. (2014). Psychological and pharmacological interventions for social anxiety disorder in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 368–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70329-3

- Mörtberg, E., Clark, D. M., Sundin, Ö., & Åberg Wistedt, A. (2007). Intensive group cognitive treatment and individual cognitive therapy vs. treatment as usual in social phobia: A randomized controlled trial. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 115(2), 142–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1600-0447.2006.00839.x

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. (2013). Social anxiety disorder: Recognition, assessment and treatment.

- Neufeld, C. B., Palma, P. C., Caetano, K. A. S., Brust-Renck, P. G., Curtiss, J., & Hofmann, S. G. (2020). A randomized clinical trial of group and individual cognitive-behavioral therapy approaches for social anxiety disorder. International Journal of Clinical and Health Psychology, 20(1), 29–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijchp.2019.11.004

- Newman, M. G., Hofmann, S. G., Trabert, W., Roth, W. T., & Taylor, C. B. (1994). Does behavioral treatment of social phobia lead to cognitive changes? Behavior Therapy, 25(3), 503–517. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7894(05)80160-1

- Oey, L. T., McDonald, S., McGrath, L., Dear, B. F., & Wootton, B. M. (2023). Guided versus self-guided internet delivered cognitive behavioural therapy for diagnosed anxiety and related disorders: A preliminary meta-analysis. Cognitive Behaviour Therapy, 52(6), 654–671. https://doi.org/10.1080/16506073.2023.2250073

- Rapee, R. M., Abbott, M. J., Baillie, A. J., & Gaston, J. E. (2007). Treatment of social phobia through pure self-help and therapist-augmented self-help. British Journal of Psychiatry, 191(3), 246–252. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.106.028167

- Ruscio, A. M., Brown, T. A., Chiu, W. T., Sareen, J., Stein, M. B., & Kessler, R. C. (2008). Social fears and social phobia in the USA: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication. Psychological Medicine, 38(1), 15–28. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291707001699

- Schulz, A., Stolz, T., Vincent, A., Krieger, T., Andersson, G., & Berger, T. (2016). A sorrow shared is a sorrow halved? A three-arm randomized controlled trial comparing internet-based clinician-guided individual versus group treatment for social anxiety disorder. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 84, 14–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2016.07.001

- Schweden, T. L. K., Pittig, A., Bräuer, D., Klumbies, E., Kirschbaum, C., & Hoyer, J. (2016). Reduction of depersonalization during social stress through cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 99–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.09.005

- Speers, A. J. H., Bhullar, N., Cosh, S., & Wootton, B. M. (2022). Correlates of therapist drift in psychological practice: A systematic review of therapist characteristics. Clinical Psychology Review, 93, Article 102132. 102132. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102132

- Stangier, U., Heidenreich, T., Peitz, M., Lauterbach, W., & Clark, D. M. (2003). Cognitive therapy for social phobia: Individual versus group treatment. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 41(9), 991–1007. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00176-6

- Stangier, U., Schramm, E., Heidenreich, T., Berger, M., & Clark, D. M. (2011). Cognitive therapy vs interpersonal psychotherapy in social anxiety disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Archives of General Psychiatry, 68(7), 692–700. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2011.67

- Stein, M. B., & Stein, D. J. (2008). Social anxiety disorder. The Lancet, 371(9618), 1115–1125. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60488-2

- Sterne, J. A. C., Savović, J., Page, M. J., Elbers, R. G., Blencowe, N. S., Boutron, I., Cates, C. J., Cheng, H. Y., Corbett, M. S., Eldridge, S. M., Emberson, J. R., Hernán, M. A., Hopewell, S., Hróbjartsson, A., Junqueira, D. R., Jüni, P., Kirkham, J. J., Lasserson, T., Li, T., … Higgins, J. P. T. (2019). RoB 2: A revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. The BMJ, 366, Article l4898. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.l4898

- Stolz, T., Schulz, A., Krieger, T., Vincent, A., Urech, A., Moser, C., Westermann, S., & Berger, T. (2018). A mobile app for social anxiety disorder: A three-arm randomized controlled trial comparing mobile and PC-based guided self-help interventions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 86(6), 493–504. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000301

- Stuhldreher, N., Leibing, E., Leichsenring, F., Beutel, M. E., Herpertz, S., Hoyer, J., Konnopka, A., Salzer, S., Strauss, B., Wiltink, J., & König, H. H. (2014). The costs of social anxiety disorder: The role of symptom severity and comorbidities. Journal of Affective Disorders, 165, 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2014.04.039

- Thew, G. R., Kwok, A. P. L., Lissillour Chan, M. H., Powell, C. L. Y. M., Wild, J., Leung, P. W. L., & Clark, D. M. (2022). Internet-delivered cognitive therapy for social anxiety disorder in Hong Kong: A randomized controlled trial. Internet Interventions, 28, Article 100539. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2022.100539

- Titov, N., Andrews, G., Choi, I., Schwencke, G., & Mahoney, A. (2008). Shyness 3: Randomized controlled trial of guided versus unguided internet-based CBT for social phobia. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(12), 1030–1040. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802512107

- Titov, N., Andrews, G., & Schwencke, G. (2008). Shyness 2: Treating social phobia online: Replication and extension. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(7), 595–605. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802119820

- Titov, N., Andrews, G., Schwencke, G., Drobny, J., & Einstein, D. (2008). Shyness 1: Distance treatment of social phobia over the Internet. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42(7), 585–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802119762

- Titov, N., Dear, B., Nielssen, O., Wootton, B., Kayrouz, R., Karin, E., Genest, B., Bennett-Levy, J., Purtell, C., Bezuidenhout, G., Tanudjaja, T. R., Minissale, C., Thadhani, P., Webb, N., Willcock, S., Andersson, G., Hadjistavropoulos, H., Mohr, D., Kavanagh, D. J., … Staples, L. (2020). User characteristics and outcomes from a national digital mental health service: An observational study of registrants of the Australian MindSpot Clinic. Lancet Digital Health, 2(11), e582–e593. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(20)30224-7

- Waller, G., & Turner, H. (2016). Therapist drift redux: Why well-meaning clinicians fail to deliver evidence-based therapy, and how to get back on track. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 129–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.005

- Wang, H., Zhao, Q., Mu, W., Rodriguez, M., Qian, M., & Berger, T. (2020). The effect of shame on patients with social anxiety disorder in internet-based cognitive behavioral therapy: Randomized controlled trial. JMIR Mental Health, 7(7), Article e15797. e15797. https://doi.org/10.2196/15797

- Watson, D., & Friend, R. (1969). Measurement of social-evaluative anxiety. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 33(4), 448–457. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0027806

- Weeks, J. W., Heimberg, R. G., Hart, T. A., Fresco, D. M., Turk, C. L., Schneier, F. R., & Liebowitz, M. R. (2005). Empirical validation and psychometric evaluation of the brief fear of negative evaluation scale in patients with social anxiety disorder. Psychological Assessment, 17(2), 179–190. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.17.2.179

- Yuen, E. K., Herbert, J. D., Forman, E. M., Goetter, E. M., Juarascio, A. S., Rabin, S., Goodwin, C., & Bouchard, S. (2013). Acceptance based behavior therapy for social anxiety disorder through videoconferencing. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 27(4), 389–397. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2013.03.002