Formation of This Group Since the mid-2000s beekeepers began to report cases of widespread, elevated mortalities of honey bee colonies () in different parts of the world. Today, international scientific monitoring of honey bee colony losses is organised as one of three ‘Core Projects’ of the non-profit honey bee research association COLOSS (prevention of honey bee COlony LOSSes). The topic of this Core Project, colony losses, is reflected in the acronym COLOSS, underlining its importance to the association! Since the very beginning of COLOSS as an EU COST-funded action in 2008, a working group has been dedicated to collect standardised data on honey bee colony losses. This group was termed “monitoring & diagnosis” and was first led and largely shaped by Romée van der Zee from the Netherlands. It is important also to note the involvement of other members who have been very active from the early days until today. These include Flemming Vejsnæs from the Danish Beekeepers Association, Victoria Soroker from Israel, Franco Mutinelli from Italy, and recently retired Preben Kristiansen from Sweden. No other international and long-lasting effort on honey bee colony health and mortality was established in Europe prior to this effort.

Figure 1. A lost honey bee colony after winter 2016/17 showing sealed honey stores, beebread and remains of a small winter cluster of bees (all dead). Photo: Robert Brodschneider.

It was the aim of the group to coordinate the efforts of several countries to find common ground in surveying beekeepers about losses of their honey bee colonies, and to use the data for risk analysis. In the European-dominated group, winter was defined as the most important period of honey bee colony losses, as most losses occur then, and the first coordinated surveys were soon conducted in a number of European countries (van der Zee et al., 2012). Lively discussions often prevailed during the group meetings, including, for example, on how to define the extent of winter, what actually is a dead honey bee colony, and much more. Scientists are often confronted with such discussions, but different climatic backgrounds, languages, and philosophies of beekeepers as addressees were new to the researchers. It is important to note that communicating with beekeepers as peers, and their valued involvement, were always important issues in this group, as was the premise to keep the study as simple as possible. Important definitions, study designs and methods for analysis were finally established in an article published in the COLOSS BEEBOOK (van der Zee et al., Citation2013). This project is only the first level of investigating honey bee colony losses. For precise identification of causes, prevalence of diseases, etc., expensive field studies are needed. Nevertheless, van der Zee et al. (Citation2012) provides a first glimpse of honey bee colony mortality in Europe. Furthermore, it described apicultural best management practices, and demonstrated that achieving very high sample sizes (participation rates) in a highly cost-effective way is possible. The strength of this ongoing study undoubtedly is the large dataset it generated and continues to generate.

The Current Position

Representing only a few countries initially, the Core Project has grown to nearly 40 coordinators for monitoring in as many countries today. The backgrounds and working environments of these coordinators are extremely varied. Our colleagues include university researchers, and employees of veterinary agencies or beekeeping associations. They conduct the monitoring research as part of their profession, with national funding, or even without any funding.

From 2014 onwards, the authors of the current article have shared the administrative responsibilities of this Core Project. We host workshops each February to plan the forthcoming monitoring in the participating countries. The average in-person attendance is between 15 and 20 coordinators, though we also had to adjust to limited travel resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic and began to host online meetings. The 2021 online meeting attracted more than 50 participants, some of whom would not normally be able to attend because of travel costs.

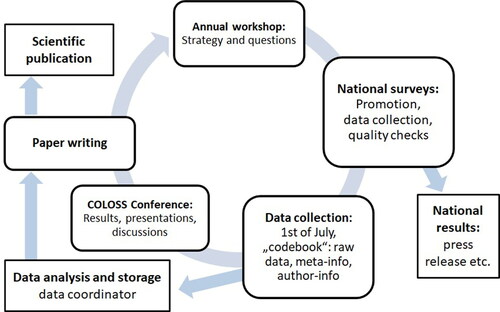

The COLOSS monitoring year starts with the workshop in February, followed by the data collection period (). The survey is comprised of questions on the apiary location and number of colonies before winter, and the number of colonies lost due to natural disaster, queen failure or dead colonies or empty hives. Additionally, questions on migratory beekeeping, Varroa destructor control, forage sources, etc. inform us about hive management practices. The COLOSS monitoring Core Project provides a backbone of mandatory and optional questions, but coordinators are welcome to add questions of local importance for use at national level. National coordinators translate the survey into local languages, and distribute and promote it via various channels, including beekeeping magazines and in-person meetings. Over the past few years, internet-based surveys have gained considerable importance and have been gradually implemented within more countries. The opening and duration of the survey is at the discretion of the national coordinators, but April and May are the most important months for data collection. We aim for as many responses as possible from each country. Due to data protection issues, beekeepers can participate anonymously, but even if they leave contact details, these will never be shared with third parties. After data collection, aggregated national results can be quickly communicated to beekeepers, e.g., via press releases.

By 1st of July each year, all collected raw data should be returned in an anonymised form to the Core Project chairs for analysis. The most obvious outcome is the annual winter mortality rate. Without doubt, this study is the world’s largest investigation using standardised data on honey bee colony mortality, collecting at present information on more than 700,000 colonies from ∼28,000 beekeepers in 35 countries (Gray et al., 2020).

Beekeeper Involvement

The monitoring Core Project is probably the best-known activity of COLOSS amongst beekeepers, given the regular calls for their participation. Beekeepers may perceive this study as a survey, but we prefer to understand their contribution in the context of citizen science as those of experts in the field. They understand the terminology and report the empirical over-winter outcome of their colonies for the purposes of science. However, in our opinion, there should be even more levels of involvement of beekeepers in this research. First, beekeepers are participating as volunteers to help science. Second, in some countries, a close involvement of beekeepers enables their input in pre-trials of the survey, co-creation workshops for study design, comments on which questions should be included or open discussions on how data/results should be presented. In some countries, beekeeper contacts may be very important to recruit other beekeepers for participation in the survey.

The response rate as a proportion of the known beekeeper population is highly variable among the participating countries, ranging from less than 1% in some countries to more than 10% in Denmark, Germany, Ireland, Netherlands, Malta, Scotland, Sweden and Norway (Brodschneider et al., Citation2016; Gray et al., Citation2020).

Dissemination of results is crucial for the success of this Core Project, and, like the promotion of the survey, greatly depends on the coordinators. When beekeepers kindly support us with valuable data on the well-being of their colonies, there should also be feedback to them to encourage future participation. This ranges from openly communicated loss rates to compare with their own over-wintering success, to the depiction of most common management practices, and science-based recommendations. Such feedback is given via articles in beekeeping magazines, websites dedicated to dissemination of the results, talks to beekeeping groups, etc.

The Outcome for Both Science and Beekeeping

The monitoring Core Project has published a series of open access articles in the Journal of Apicultural Research, reporting comparable honey bee colony loss rates for many countries. A typical winter loss rate is around 16%, with large variations among countries. Losses at national level can be as low as <5%, but can also be more than 30% (Gray et al., 2019; 2020). A minority (usually 4-5 percentage points) of these losses are due to colonies with unsolvable queen problems, while the majority (around 10 percentage points) are dead colonies or empty hives. A very small proportion of the losses (typically 1 − 2 percentage points) are colonies lost due to natural disasters of various kinds such as flooding, fire, or storm.

Besides calculating colony loss rates, the data are used for statistical identification of risk factors and best beekeeping practice methods. It is important to point out the very diverse beekeeping management styles across the surveyed areas, from Scandinavia to the Mediterranean, as generalisations about best practice methods may not always be feasible. So far, the following risk factors have been identified as related to colony mortality: operation size (large beekeeping operations often have lower losses, Brodschneider et al., Citation2016, Citation2018), migratory beekeeping (the nature of the effect varies from year to year and between countries; see Brodschneider et al., 2018, Gray et al., Citation2019, Citation2020), forage sources (effects differ among countries, Gray et al., 2019) and percentage of young queens (Gray et al., 2020). To elaborate the effect of young queens: this finding is based on the question “How many of the wintered colonies had a new queen in the year before wintering?”. The percentage of colonies going into winter with a new queen was estimated as 55.0%, which is probably an underestimation, as supersedure is often not recognised by beekeepers. Higher percentages of young queens correspond to lower losses from unresolvable queen problems, and lower losses from winter mortality (and naturally the sum of losses of those two classes). Having young queens for good development of strong colony populations is therefore one clear recommendation that can be drawn from the investigation (Gray et al., 2020).

Where We Can Improve

We also want to use this article to evaluate the work of this Core Project critically.

Operation Level versus Apiary Level Study

A sometimes-raised point is that we investigate colony losses at operation level, not apiary level, as differences among apiaries may occur. Most respondents have a single apiary, and those who do not may well manage all their apiaries in the same way. This is one of the compromises we need to make; the alternative would be that larger beekeeping operations must fill out the survey for each apiary separately. This would increase spatial resolution, but also complicate identifying the effect of the same beekeeper managing these colonies!

Aspects of Sampling

Important aspects of sampling are coverage of the hive and beekeeper population by the survey (reach) and achieving a high response rate. These issues are discussed in detail in van der Zee et al. (2013). Low coverage may mean lack of geographic coverage, for example, or omitting part of the beekeeper population, such as older beekeepers, so that a representative sample is not obtained. A high response rate is also needed. For example, if few older beekeepers respond to the survey, there may be non-response bias in the results. Random sampling of the whole population is traditionally recommended for representative results and working to achieve a high response rate from those selected to participate. Implementing random sampling does require more information about the beekeeper population than is often available.

Most countries in the monitoring group now aim to reach as large a proportion of the beekeeper population as possible, through making the survey available as widely as possible. It is clear, however, that coverage and response rates vary widely between countries. This includes small sample sizes, i.e., a low proportion of the estimated beekeeper population responding and/or responses being limited to a few regions of the country.

Data Sharing and Repository

Data collected are analysed within the group and results of analysis, including calculated loss rates at country level, are made publicly available through group publications. Coordinators may analyse their own national data as they feel is appropriate and may choose to share their own national aggregated level data in suitable data repositories, subject to any undertakings they may have given to their participating beekeepers and appropriate data protection regulation. Sharing the complete dataset for analysis by researchers from outside the group is currently not available as we want to protect intellectual property, but this is a frequently addressed issue in the monitoring group.

Multifactorial Modelling

Beekeepers and policy makers want the results of our research to include a ranking of the most significant causes of colony mortality. Researchers broadly agree that the causes of colony losses are multifactorial, and a remote diagnosis based on reports from beekeepers is not very reliable, as they cannot detect, for example, virus infections or pesticide residues. It is possible to carry out multifactorial modelling of the risk of colony loss, as in van der Zee et al. (Citation2014), and the statistical significance of effects and their importance in the model can be examined; however, these factors are limited to what the beekeeper can reliably answer questions about, such as aspects of hive management, and cannot consider all relevant risk factors. We, therefore, refrain from asking about some factors such as virus or pesticide load, or varroa infestation levels. These factors definitively need thorough scientific investigation, but cannot reliably be reported by beekeepers.

Seasonal and Annual Losses

As more countries from hotter climates have been participating in the survey, it has become apparent that the term “winter” cannot be applied universally, and that summer losses or annual losses are relevant outside of the temperate regions. The recently growing participation of North African and Middle East countries could develop into a subgroup focussing more on how to best survey these. Inclusion of countries where Apis cerana is kept would probably make these steps even more necessary.

Conclusion

The Core Project hopes to extend its outreach to gradually include more countries from other continents and increase response rates from beekeepers in the countries already participating. Our research relies critically on cooperation with beekeepers. We hope that the findings of our work, disseminated to the beekeepers, help to reduce colony losses. We also believe that the current monitoring since 2008 has educated society and beekeepers by reflecting on the welfare of honey bee colonies, and has provided a foundation for further investigations with participation of beekeepers as citizen scientists. Finally, the outcomes of this large-scale investigation deliver empirical international honey bee colony loss rates as demanded by many stakeholders and decision makers.

Institute of Biology, University of Graz, Graz, Austria

*Email: robert.brodschneider@uni-graz

Robert Brodschneider https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2535-0280

Alison Gray

Department of Mathematics and Statistics, University of Strathclyde, Glasgow, UK

Alison Gray https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6273-0637

COLOSS Monitoring Core Project

The Active National Coordinators of the COLOSS Core Project “Monitoring of Honey Bee Colony Losses”

Acknowledgements

We thank all national coordinators for their efforts and their continuous input and discussion. We acknowledge COLOSS for supporting our networking activities. Open access funding has been provided by the University of Graz.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Brodschneider, R., Gray, A., van der Zee, R., Adjlane, N., Brusbardis, V., Charrière, J.-D., Chlebo, R., Coffey, M. F., Crailsheim, K., Dahle, B., Danihlík, J., Danneels, E., de Graaf, D. C., Dražic´, M. M., Fedoriak, M., Forsythe, I., Golubovski, M., Gregorc, A., Grze˛da, U., … Woehl, S. (2016). Preliminary analysis of loss rates of honey bee colonies during winter 2015/16 from the COLOSS survey. Journal of Apicultural Research, 55(5), 375–378. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2016.1260240

- Brodschneider, R., Gray, A., Adjlane, N., Ballis, A., Brusbardis, V., Charrière, J.-D., Chlebo, R., Coffey, M. F., Dahle, B., de Graaf, D. C., Dražic´, M. M., Evans, G., Fedoriak, M., Forsythe, I., Gregorc, A., Grze˛da, U., Hetzroni, A., Kauko, L., Kristiansen, P., … Danihlík, J. (2018). Multi-country loss rates of honey bee colonies during winter 2016/2017 from the COLOSS survey. Journal of Apicultural Research, 57(3), 452–457. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2018.1460911

- Gray, A., Brodschneider, R., Adjlane, N., Ballis, A., Brusbardis, V., Charrière, J.-D., Chlebo, R., F. Coffey, M., Cornelissen, B., Amaro da Costa, C., Csáki, T., Dahle, B., Danihlík, J., Dražic´, M. M., Evans, G., Fedoriak, M., Forsythe, I., de Graaf, D., Gregorc, A., … Soroker, V. (2019). Loss rates of honey bee colonies during winter 2017/18 in 36 countries participating in the COLOSS survey, including effects of forage sources. Journal of Apicultural Research, 58(4), 479–485. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2019.1615661

- Gray, A., Adjlane, N., Arab, A., Ballis, A., Brusbardis, V., Charrière, J.-D., Chlebo, R., Coffey, M. F., Cornelissen, B., Amaro da Costa, C., Dahle, B., Danihlík, J., Dražic´, M. M., Evans, G., Fedoriak, M., Forsythe, I., Gajda, A., de Graaf, D. C., Gregorc, A., … Brodschneider, R. (2020). Honey bee colony winter loss rates for 35 countries participating in the COLOSS survey for winter 2018–2019, and the effects of a new queen on the risk of colony winter loss. Journal of Apicultural Research, 59(5), 744–751. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00218839.2020.1797272

- van der Zee, R., Pisa, L., Andonov, S., Brodschneider, R., Charrière, J.-D., Chlebo, R., Coffey, M. F., Crailsheim, K., Dahle, B., Gajda, A., Gray, A., Drazic, M. M., Higes, M., Kauko, L., Kence, A., Kence, M., Kezic, N., Kiprijanovska, H., Kralj, J., … Wilkins, S. (2012). Managed honey bee colony losses in Canada, China, Europe, Israel and Turkey, for the winters of 2008–2009 and 2009–2010. Journal of Apicultural Research, 51(1), 100–114. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.51.1.12

- van der Zee, R., Gray, A., Holzmann, C., Pisa, L., Brodschneider, R., Chlebo, R., Coffey, M. F., Kence, A., Kristiansen, P., Mutinelli, F., Nguyen, B. K., Noureddine, A., Peterson, M., Soroker, V., Topolska, G., Vejsnaes, F., & Wilkins, S. (2013). Standard survey methods for estimating colony losses and explanatory risk factors in Apis mellifera. In V. Dietemann, J. D., Ellis, & P. Neumann, (Eds.), The COLOSS BEEBOOK, Volume II: Standard methods for Apis mellifera research. Journal of Apicultural Research, 52(4), 1-36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.52.4.18

- van der Zee, R., Brodschneider, R., Brusbardis, V., Charrière, J.-D., Chlebo, R., Coffey, M. F., Dahle, B., Drazic, M. M., Kauko, L., Kretavicius, J., Kristiansen, P., Mutinelli, F., Otten, C., Peterson, M., Raudmets, A., Santrac, V., Seppälä, A., Soroker, V., Topolska, G., Vejsnaes, F., & Gray, A. (2014). Results of international standardised beekeeper surveys of colony losses for winter 2012-2013: Analysis of winter loss rates and mixed effects modelling of risk factors for winter loss. Journal of Apicultural Research, 53(1), 19–34. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3896/IBRA.1.53.1.02