Introduction

Recent studies estimate that the population of insects has declined in total biomass, and many species are endangered (Hallmann et al., Citation2021). It identifies deforestation, urbanisation, pollution and the widespread use of pesticides in commercial agriculture as causes for this (Franco, Citation2020). There are some recommendations for improving honey bee health, which include: reducing exposure to insecticides; preventing and limiting the spread of disease and providing a greater diversity of floral resources throughout the year (Goulson et al., Citation2015).

Urban beekeeping or beekeeping in the cities is a trending topic, as more and more citizens are willing to live in a sustainable and green environment, when nature is fully integrated into modern city infrastructure. Urban agriculture also is becoming an important part of official cities development strategies with the urban beekeeping popularity rising as well (Pires, Citation2011). Urban beekeeping positively impacts agricultural functions, such as pollination, honey production, community building, environmental education, and ecosystem sustainability (Matsuzawa et al., Citation2020). Urban beekeeping is booming and raising awareness of pollinator importance (Casanelles-Abella & Moretti, Citation2022). In many parts of the world, bee species are being studied in urban environments (Baldock et al., Citation2015; Banaszak-Cibicka and Zmihorski, Citation2012). Urban beekeeping supports many social benefits, from food production to environmental awareness (Lorenz & Stark, Citation2015).

Cities are increasingly committed to sustainability goals (Sustainable Development Goal 11), leading to initiatives to enhance environmental justice and promote biodiversity. Most municipalities do not have any guidelines for beekeeping in the cities or this information is very limited (Matsuzawa et al., Citation2020). For example, in Jelgava, Latvia there are no policies or directions for urban beekeeping or for urban agriculture, only one separate regulation that states how the beehives should be placed in a city. Other cities, like Helsinki, published an introduction for small-scale beekeeping in the city (City of Helsinki, Citation2021). The action is controlled by the city government as the beekeepers need to have permission from the city to keep bees, also the city has many instructions on how to start beekeeping, when the permission is handed out and beekeepers have bees in the city. In other countries urban beekeeping is more known and there are a lot of big cities that have beehives on rooftops. Urban beekeeping has been rapidly expanding globally in major urban areas such as London, Paris, Sydney, Warsaw, Hong Kong, these are the big known cities that have a lot of city beehives (Matsuzawa & Kohsaka, Citation2021). In Tallinn, the city municipality is very supportive towards urban agriculture and beekeeping (Solba, Citation2020). Also, there is a study, which analyses the status and details of regulations at national, regional and local levels in Australia, US and Japan (Matsuzawa & Kohsaka, Citation2022).

Within the cities, honey bees can also act as a means for environment monitoring, as bees can be considered as mobile samplers and bioindicators of chemical contamination (Girotti et al., Citation2020). For example, in Rome bees are also being used as biodiversity indicators. An area up to 2 km in distance from the hive is being monitored by bees in order to acquire extra information about the situation with pollution in the city (Orlandi, Citation2022).

Looking at the authors’ local country Latvia, despite the fact that beekeeping is an old and classical branch of agriculture, there are not many examples of urban beekeeping there. Some colonies are placed on rooftops in the capital city Riga. Recently also the so-called bee embassy was established to demonstrate bee colonies and their potential deployment in an urban environment. As well in Jelgava city an urban apiary is established on a hospital rooftop (Uz Jelgavas…, Citation2022).

Local beekeepers state that up to 2000 colonies are deployed in the capital city Riga during the linden tree flowering time each year, but only some of them are located constantly in urban environment, others are owned by migratory beekeepers (LETA, Citation2022).

The aim of this paper and social research is to analyse the citizens’ awareness about the urban beekeeping topic and conclude about its popularity and development in Latvia.

Materials and Methods

A survey was conducted to study the awareness of Latvian citizens about the urban beekeeping topic and what is their attitude towards its development and spread. The survey was implemented as an online questionnaire in Latvian language using Google Forms. The questions focused on multiple choice answers and open-ended responses.

The survey addressed several sub-topics: 1) Several questions were used to describe a respondent’s profile: residence, age and gender; 2) Questions related to the emotional relationships with bees and bee products; 3) Basic questions about the urban beekeeping topic and observed locations of the bee apiaries within the cities; 4) Direct questions about the development perspectives of urban beekeeping in Latvia (where to place hives, how many, benefits of urban beekeeping); 5) Several questions about the attitude towards locations where beehives are placed (is it required to place a special sign, is a map required to provide beehive locations, potential risk factors etc.).

The survey was conducted between June and August 2022. The questionnaire in its original form was disseminated using social networks, Latvian University of Life Sciences and Technologies homepage and bee related portals.

Results and Discussion

In total, 207 respondents completed the survey and below we present the main findings and results of the questionnaire, analysing the citizens answers and attitude towards urban beekeeping.

Respondents Profile

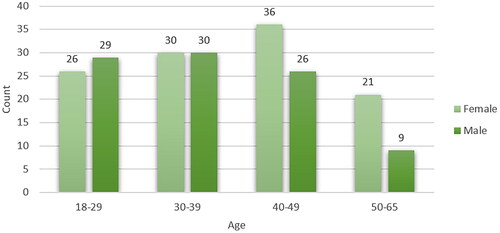

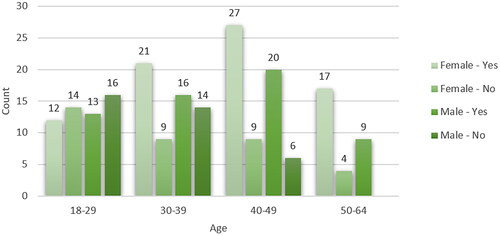

There were 113 women and 94 men participating in the aged from 18 to 64. shows gender and age distribution among the respondents. It can be seen that in two age groups (18–29 and 30–39) gender distribution is almost equal, but with increasing age, distribution is biased towards woman.

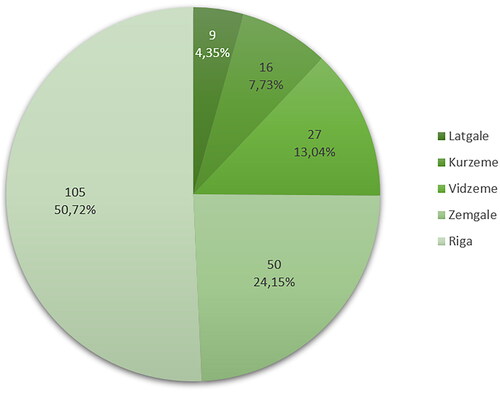

Analysing the geographical region of the participants (see ), most of the respondents were from the capital city Riga (50.72%), 24.15% were from Zemgale region where authors’ university is located, but few from Latgale region (4,35%). For the reference on planning regions of Latvia please see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Planning_regions_of_Latvia.

Questions Related to the Emotional Relationships with Bees and Bee Products

It is known that in general bees are not aggressive insects, but defensive and not attacking without reason (Anderson, Citation2022), thus it was interesting to investigate peoples’ awareness of this fact. Only 10 participants (4,83%) (5 men and 5 women) stated that bees can be considered as aggressive insects.

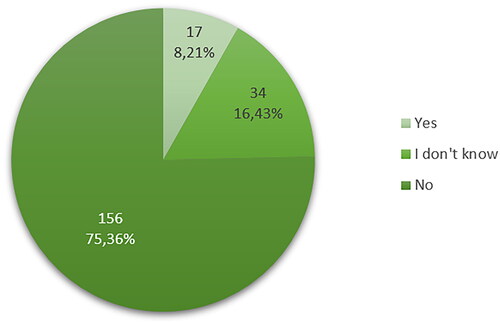

It is important to know if one has an allergic reaction to bee stings, so this question was included as well (see ). It was surprising that 16.43% of participants do not even know if they have an allergic reaction. Most of the respondents (75.36%) do not have any allergy to bee stings.

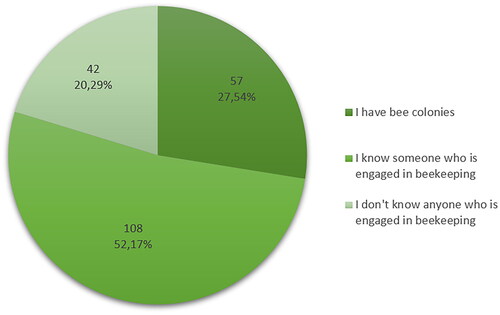

Honey and honey products are widespread nowadays: 91% of the participants like honey and other bee related products. 79.71% of respondents know a beekeeper or are beekeepers themselves (see ). This could correlate with a more positive attitude towards urban beekeeping.

Basic Questions about the Urban Beekeeping Topic

Men know a little bit less about urban beekeeping compared to women (see ): 61,7% out of male respondents know something about urban beekeeping and 68.14% of female respondents have heard about urban beekeeping. The knowledge about urban beekeeping is evenly distributed across all age groups and genders.

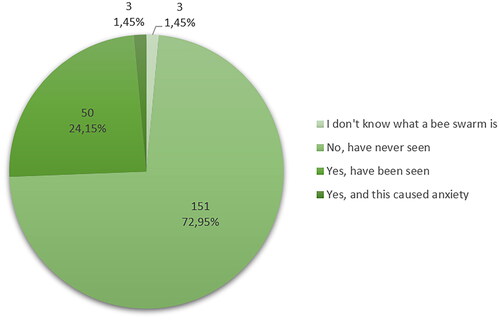

One of the natural bee colony behaviours is swarming, thus it was important to know if people know what it is and if they ever encountered a swarm. It is very positive that only 3 respondents do not know what swarming is (see ). 50 respondents have seen swarms in the city, but only for 3 respondents it looked dangerous and causes anxiety.

Next open question was regarding citizens’ knowledge about urban apiary locations in Latvia and also abroad. As stated by participants, in Latvia urban apiaries and individual colonies were seen in several main cities, like Riga, Jelgava, Jurmala, Cesis, Liepaja, Kuldiga, Talsi, Dagda, Kalnciems and Smiltene.

In other countries such cities as Vienna, Graz (Austria); Peterhead (Scotland); Apeldoorn (Netherlands); London (UK); Siauliai (Lithuania); Oslo (Norway), Paris (France); Berlin, Stuttgart, Hamburg (Germany); Brussels (Belgium); Belgrade (Serbia); New York (USA); Malta and cities in Switzerland were mentioned in the survey.

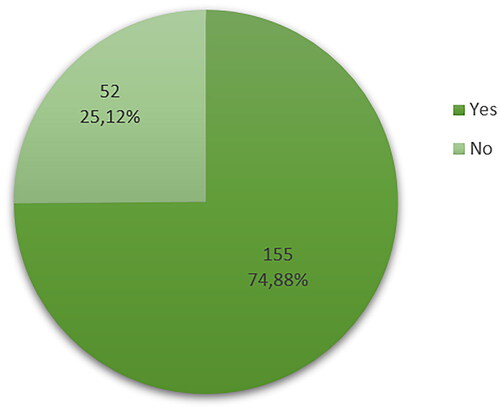

The next question, “Would you support placing beehives in the urban environment?” was the most important in this survey, which directly reflects the citizens’ attitude towards urban beekeeping and its perspective (see ). 74.88% participants would support urban beekeeping. Furthermore, among respondents who themselves are beekeepers or know some beekeepers 79,4% support urban beekeeping. It is interesting that even people with an allergy to bee stings are supporting urban beekeeping, 6 of 17 with an allergy would not support this.

Direct Questions about the Development Perspectives of the Urban Beekeeping in Latvia

Next questions were asked only to persons, who support urban beekeeping. Questions were about the potential location of urban beehives, optimal number of hives and if the respondents can advise exact location for the urban apiary in their city.

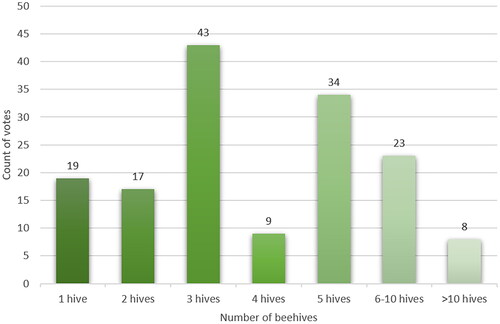

Answers regarding the optimal number of hives in one location are highly variable (see ). Most of the votes (28.10%) went to 3 hives in one location, little bit less votes (22.22%) went to 5 hives, 15.03% stated that from 6-10 hives should be placed, almost equal votes (12.42% and 11.11%) suggested 1 or 2 hives and surprisingly 8 people suggested more than 10 hives to be placed.

Rooftops are mentioned as the most suitable location − 120 (77.42%), then small private gardens, which are situated within the city borders 95 (61.29%) and parks 77 (49.68%). Rooftops are most popular as they look more safer for the citizens to have colonies there, as it decreases bee and human traffic interaction probability. Last question in this section was related to the benefits of urban beekeeping, it was a question with several possible answers. Almost all respondents (92.3%) acknowledged that urban beekeeping would facilitate the pollination of urban trees, shrubs and flowers. 68,4% of respondents mentioned that urban beekeeping would encourage the interest of children and young people in beekeeping. 61,9% mentioned that biological diversity would be promoted. And only 14,2% think that urban beekeeping would allow beekeepers to harvest more ecological honey, thus it can be concluded that citizens are aware of the honey quality and are concerned about the air pollution within the cities.

Attitude towards Locations Where Beehives Are Placed

The last section of the questionnaire was related to the general attitude to the locations where beehives could be placed.

76.33% of participants would generally attend such places, knowing that there are bee colonies. The majority (95.17%) of the respondents pointed out that it is necessary to add visible signs and information that bee colonies are placed nearby. Authors emphasise the importance of this topic and propose to include requirements for markings in further policies and guidelines.

65.70% of respondents positively evaluated the option of a map with urban apiary locations in the city, thus this could be developed as stand-alone service or integrated with Google Map or other map services and applications.

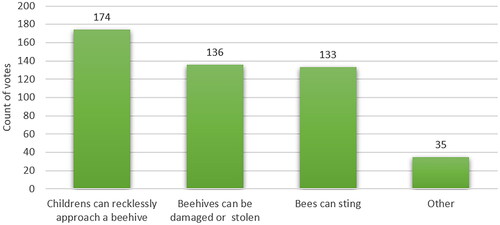

Evaluating the risk factors of urban beekeeping (see ), most of the respondents 174 (84.06%) mentioned the risk that children can recklessly approach a beehive. The second important risk mentioned by 136 (65.7%) respondents is that beehives could be damaged or even stolen. 133 (64.25%) respondents are worried about bee stings. Other factors such as: “this would threaten other pollinators”, “bee products would lack quality” or even “stating that the city is not for bees” gained very low agreement (from 2 to 8%).

87.44% affirmatively stated that regulations and guidelines should be developed for urban beekeepers, where and how hives should be placed.

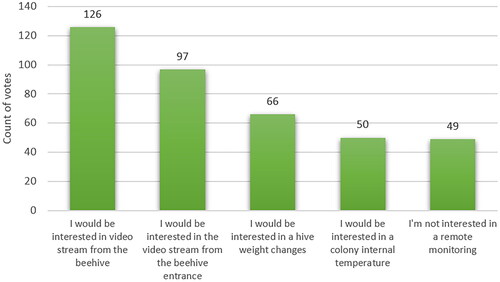

The last question of the survey was related to the application of information and communication technologies in beekeeping, asking if citizens would be interested to track and look at some colony internal parameters remotely within some app or web interface (see ). It is concluded that most of the people are interested in video monitoring (video from the inside or from the hive entrance): 126 (60.87%) and 97 (46.86%) respondents mentioned this respectively. 66 responses were for weight monitoring and 50 responses for temperature monitoring. 49 respondents are not interested in remote monitoring at all.

It is very positive that people are interested in such monitoring options, thus accepting a precision beekeeping approach (Zacepins et al., Citation2015; Citation2021).

Conclusion

After the survey authors were satisfied with its outcome. For sure not everyone supports the urban beekeeping direction and is aware of it, but in general it has perspectives and potential in Latvia.

Definitely there can be some negative points within the urban beekeeping topic. If it becomes unregulated then it can have a negative impact on the general ecosystem, when the number of honey bees is rising too high they can start out-numbering other pollinators, because all of the insects feed on pollen and nectar (Geldmann and Gonzales-Varo, Citation2018).

Also, there should be legal regulation of the urban beekeeping activities and recommendations. For example, the density of hives in an urban environment should be controlled (Heaf, Citation2009). Higher honey bee densities could threaten urban wild insect pollinators and their important ecological functions, which includes pollination of wild and cultivated plants (Baldock, Citation2020). Municipalities should also develop the urban beekeeper’s registration or use the existing overall beekeeping register to track the number of hives and also to have the possibility to identify the owner of the hives in case of some emergency or accidents.

In Latvia there is only one regulation stating that beehives in cities should be placed 25 m from the traffic roads or from neighbour properties or should be fenced by 2,5 m high fences (Civil law. Part three. Case law, 1101 article).

From a conversation with Latvian beekeeper and researcher of the Latvian Beekeeping Association Valters Brusbardis, he was stating that: “Bee colonies should be placed in a way so that they do not disturb people. If the bee colony disturbs the neighbours or other citizens it should be relocated to another place.” This statement makes a lot of sense and if every beekeeper will act in such a way in the urban environment then successful co-existence of bees and humans will be achieved.

Next investigations should be targeted at the evaluation of potential honey resources in the cities and development of the methodology for optimal location identification and evaluation, where urban bee colonies should be placed.

Urban beekeeping is a growing trend and in the future bees should be welcomed in every city. This paper was focused on a social part of urban beekeeping research. In the future it is required to complete spatial research to investigate and identify optimal places for the urban apiaries within the Latvian cities. Social research allowed us to identify citizens’ awareness and attitude towards bees and urban beekeeping. Based on the questionnaire, the citizens are mostly aware about the beekeeping in cities, as 135 (65.22%) people from 207 have heard or know something about urban beekeeping. In Latvia 74.88% would support urban beekeeping and have a positive attitude towards its further development. It is worth mentioning that many respondents acknowledged the need for the specific guidelines, regulations and recommendations for urban beekeeping.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, C. (2022). Why are my bees suddenly aggressive? Retrieved September 6, 2022, from https://carolinahoneybees.com/aggressive-bees-in-late-summer/

- Baldock, K. C. (2020). Opportunities and threats for pollinator conservation in global towns and cities. Current Opinion in Insect Science, 38, 63–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cois.2020.01.006

- Baldock, K. C. R., Goddard, M. A., Hicks, D. M., Kunin, W. E., Mitschunas, N., Osgathorpe, L. M., Potts, S. G., Robertson, K. M., Scott, A. V., Stone, G. N., Vaughan, I. P., & Memmott, J. (2015). Where is the UK’s pollinator biodiversity? The importance of urban areas for flower-visiting insects. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 282(1803), 20142849. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2014.2849

- Banaszak-Cibicka, W., & Z.mihorski, M. (2012). Wild bees along an urban gradient: Winners and losers. Journal of Insect Conservation, 16(3), 331–343. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10841-011-9419-2

- Casanelles-Abella, J., & Moretti, M. (2022). Challenging the sustainability of urban beekeeping using evidence from Swiss cities. Npj Urban Sustainability, 2(1), 1–5. https://doi.org/10.1038/s42949-021-00046-6

- City of Helsinki. (2021). Beekeeping in public areas in the city. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.hel.fi/helsinki/en/housing/plots-land-buildings/permits-for-public-areas/renting-of-land-areas/beekeeping/

- Franco, E. G. (2020). The global risks report 2020 - 15th Edition. In World Economic Forum. Retrieved September 6, 2022, from https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_Global_Risk_Report_2020.pdf

- Geldmann, J., & González-Varo, J. P. (2018). Conserving honey bees does not help wildlife. Science (New York, N.Y.), 359(6374), 392–393. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.aar2269

- Girotti, S., Ghini, S., Ferri, E., Bolelli, L., Colombo, R., Serra, G., Porrini, C., & Sangiorgi, S. (2020). Bioindicators and biomonitoring: Honeybees and hive products as pollution impact assessment tools for the Mediterranean area. Euro-Mediterranean Journal for Environmental Integration, 5(3), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41207-020-00204-9

- Goulson, D., Nicholls, E., Botías, C., & Rotheray, E. L. (2015). Bee declines driven by combined stress from parasites, pesticides, and lack of flowers. Science (New York, N.Y.), 347(6229), 1255957. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1255957

- Hallmann, C. A., Ssymank, A., Sorg, M., de Kroon, H., & Jongejans, E. (2021). Insect biomass decline scaled to species diversity: General patterns derived from a hoverfly community. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(2), e2002554117. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.2002554117

- Heaf, D. (2009). Towards sustainable beekeeping. The Beekeepers Quarterly, 91, 2–4.

- LETA. (2022). Apbišota-s pilse-tas. Retrieved April 1, 2022, from https://www.saimnieks.lv/raksts/apbisotas-pilsetas#

- Lorenz, S., & Stark, K. (2015). Saving the honeybees in Berlin? A case study of the urban beekeeping boom. Environmental Sociology, 1(2), 116–126. https://doi.org/10.1080/23251042.2015.1008383

- Matsuzawa, T., Kohsaka, R., & Uchiyama, Y. (2020). Application of environmental DNA: Honey bee behavior and ecosystems for sustainable beekeeping. In Modern beekeeping-bases for sustainable production. IntechOpen. https://doi.org/10.5772/intechopen.92717

- Matsuzawa, T., & Kohsaka, R. (2021). Status and trends of urban beekeeping regulations: A global review. Earth, 2(4), 933–942. https://doi.org/10.3390/earth2040054

- Matsuzawa, T., & Kohsaka, R. (2022). A systematic review of urban beekeeping regulations of Australia, the United States, and Japan: Towards evidence-based policy making. Bee World, 99(3), 89–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/0005772X.2022.2073952

- Orlandi, G. (2022). The fuzz with the buzz: How bees are helping Italy’s Carabinieri police fight pollution. Euronews.green. Retrieved June 15, 2022, from https://www.euronews.com/green/2022/05/30/the-fuzz-with-the-buzz-how-busy-bees-are-helping-italy-s-carabinieri-police-fight-pollutio

- Pires, V. (2011). Planning for urban agriculture planning in Australian cities. In Proceedings of the State of Australian Cities Conference (SOAC) (Vol. 5).

- Solba, S. (2020). Urban beekeeping and people awareness about it based on Tartu [Master’s thesis], Eesti Maaülikool.

- Uz Jelgavas poliklı-nikas jumta top bišu da-rzs. (2022). Retrieved September 6, 2022, from http://www.jelgavniekiem.lv/?l=2&act=10&date=1657746000&cat=10&art=54596

- Zacepins, A., Brusbardis, V., Meitalovs, J., & Stalidzans, E. (2015). Challenges in the development of precision beekeeping. Biosystems Engineering, 130, 60–71. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biosystemseng.2014.12.001

- Zacepins, A., Kviesis, A., Komasilovs, V., Brusbardis, V., & Kronbergs, J. (2021). Status of the precision beekeeping development in Latvia. Rural Sustainability Research, 45(340), 86–92. https://doi.org/10.2478/plua-2021-0010