ABSTRACT

This paper reports the first case of predation on the nests of Asian Hornet Vespa velutina by the European Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus, as well as the use of this resource by a breeding pair to provision their nestlings. The Asian Hornet is listed among the 100 most invasive alien species and is expanding in Western Europe. Our finding opens the door to a number of questions, including the effects of this additional allochthonous resource on the European Honey Buzzard populations, as well as the potential of this raptor as a biocontrol agent.

Invasive alien species represent a major factor of the current biodiversity crisis, the sixth global extinction, second only to habitat loss and fragmentation (Mack et al. Citation2000). Understanding predation dynamics between native and alien species is crucial (Carlsson et al. Citation2009). The Asian Hornet Vespa velutina is a highly invasive alien wasp that was introduced to France in 2004 (Haxaire et al. Citation2006) and has since expanded across Western Europe (Smit et al. Citation2018 and references therein). The presence of this wasp creates an important social alarm because it is a threat to native biodiversity, to economic activities in the first sector (especially due to predation on Western Honey Bee Apis mellifera) and to human health (Monceau et al. Citation2014).

A number of birds are known to predate on the Asian Hornet in its native range, notably the Crested Honey Buzzard Pernis ptilorhynchus (Becking Citation1989) but, to date, the few species reported as predators in Europe have only involved birds taking individual adult wasps (e.g. European Bee-eater Merops apiaster) or attacking abandoned nests (Eurasian Magpie Pica pica, Great Tit Parus major and Eurasian Nuthatch Sitta europaea; Villemant et al. Citation2010). In this paper, we report the first case of Asian Hornet nest predation by the European Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus, as well as the use of this resource by a breeding pair to provision their nestlings. This migratory raptor breeds in Europe during the summer and overwinters in Africa. The adults have specific adaptations in order to prey on wasps, which form the bulk of their diet (76.4%; Gamauf Citation1999).

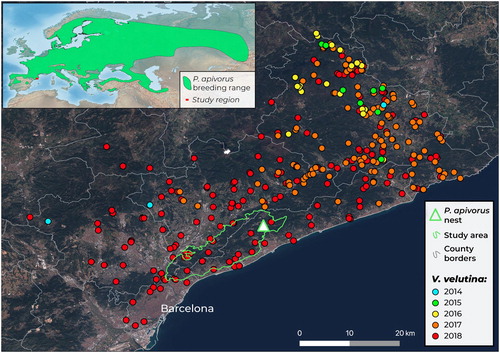

During 2011–2018 we surveyed a breeding population of European Honey Buzzards in Catalonia, Spain. The area covered 177 km2 (), including the protected area Serres del Litoral Septentrional (Zona Especial de Conservació ES5110011). The breeding density of the species was relatively low (0.6-2.8 pairs/100 km2 during 2010–2015, Macià et al. Citation2017). Remains of preys were collected in one or two nests per year, except for 2017, when no breeding pairs were detected. In parallel, camera-traps were installed at five of these nests. For the first time, three fragments of a wasp nest with unusually large larval cells were observed and collected, on 2nd August 2018, from a nest with nestlings (). These fragments were not present on the 20th July, when samples were previously taken. Only a few fragments of wasps were found inside the cells, and morphological identification of the insect species was not possible. However, based on the nest morphology, they could only belong to either the native European Hornet Vespa crabro, which is uncommon in the area, or the alien Asian Hornet. Molecular analysis of the wasp remains through DNA barcoding, using a 658 bp fragment of the mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase I (COI) gene sequence, following the protocol by Dincă et al. (Citation2013): DNA was extracted using Chelex resin and amplified with the primers LepF1 and LepR1. The sequences obtained from the nest fragments were uploaded to the BOLD Identification Engine (www.uni.boldsystems.org/index.php/IDS_OpenIdEngine) and an unambiguous 100% match to Asian Hornet was obtained.

Figure 1. Map of the study region. The inset shows the location of the study region and the breeding distribution range of European Honey Buzzard (BirdLife International Citation2004). The green triangle represents the European Honey Buzzard nest with Asian Hornet remains, sampled in 2018. The green line shows the area that was surveyed and grey lines the county borders. Points show the Asian Hornet nests recorded each year since its arrival in 2014 to the surrounding counties. Records were obtained from the Catalan Cos d’Agents Rurals del Departament d’Agricultura, Ramaderia, Pesca i Alimentació.

Figure 2. (A) Picture of the European Honey Buzzard nest interior at the moment of the collection (2nd August 2018). Nest remains of Vespidae are visible and the one of the Asian Hornet (with larger cells) is marked with a red circle. (B) The three Asian Hornet nest fragments analysed in the lab (scale bar represents 1 cm).

This finding represents the first unambiguous case of predation on an Asian Hornet nest during the active breeding period of the wasp. A few potential cases, also by European Honey Buzzard, were mentioned in the mass media but apparently not yet scientifically confirmed (Vigneaud Citation2013, mentioned in Monceau et al. Citation2014). The Asian Hornet is extremely aggressive and venomous, and thus, it is remarkable that the European Honey Buzzard exploits the active nests.

The main foraging range of breeding European Honey Buzzards does not usually surpass 10 km (van Manen et al. Citation2011). Until 2018, no Asian Hornet nests were documented within this distance of the nests monitored in this study. The Asian Hornet arrived in Catalonia in 2012 (Pujade-Villar et al. Citation2012-Citation2013) and to the study region in 2014. Since then, recorded wasp nest-to-bird nest distances were: 2014, 21 km; 2015, 29 and 42 km; 2016, 25 km; 2017, no breeding recorded. On the contrary, in 2018 the monitored European Honey Buzzard nest was much nearer to a number of Asian Hornet nests, the closest being only 1.8 km away ().

Assuming that the wasp presence records are accurate, which is likely given the social alarm due to the expected arrival of the species in the area, we can infer that the European Honey Buzzard started using the Asian Hornet to provision their offspring within a maximum of a year since nests were accessible. It is well known that this raptor has a number of behavioural (e.g. excavation of the wasp nests) and morphological (e.g. densely imbricated feathers) adaptations to predate wasps, as is also the case for its sister species, the Crested Honey Buzzard.

Despite our discovery being limited to a few fragments on a single nest, it opens the door to a number of questions, and long-term quantitative studies in various parts of the European Honey Buzzard range will be needed to establish the extent and evolution of the trophic exploitation of the Asian Hornet. The effects of this additional allochthonous resource on the European Honey Buzzard populations are especially intriguing.

Large colonies by social wasps that last 5–6 months, such as those of the Common Wasp Vespula vulgaris and the German Wasp Vespula germanica, are the preferred food source of the European Honey Buzzard (Gamauf Citation1999). Thus, in principle, the species should easily detect the Asian Hornet secondary nests, which are spherical and large (up to 1×0.8 m), built preferentially in tree canopies (Villemant et al. Citation2010) and easier to find compared to other native species that nest in the ground or close to it (e.g. German Wasp and Polistes spp.). In this sense, taking advantage of the Asian Hornet may decrease the risk for the European Honey Buzzard to attacks from terrestrial or aerial predators (e.g. Northern Goshawk Accipiter gentilis, Voskamp Citation2000) while manipulating the nest and extracting the fragments suitable for transportation.

Taking into account the dates when samples in the nest of the European Honey Buzzard were collected, the transport of the Asian Hornet nest fragments was made between 20th July and 2nd August 2018, coinciding with the period of maximum activity of the invasive wasp colonies. The Asian Hornet builds secondary nests mainly from August and the production of individuals may be active until December (Rome et al. Citation2015). The European Honey Buzzard requires more food between mid-June and September, in order to provision the nestlings (Hardey et al. Citation2013), but also because fuel deposition in Europe is critical for post-nuptial migration (Hake et al. Citation2003). Thus, the Asian Hornet could be a particularly profitable resource due to the huge amounts of larvae available in the nests exactly at the time when the trophic needs of the raptor are greatest (Rome et al. Citation2015).

Additionally, this raptor could be considered as a potential biocontrol agent, because it is possibly the only European bird species capable of destroying active Asian Hornet nests (i.e. secondary aerial nests) during the period of maximum generation of individual insects. Predators near the top of the food chain are crucial in ecosystem processes and can structure the biological communities (Schmitz et al. Citation2000, Sergio et al. Citation2007). It is premature to speculate about the impact of the European Honey Buzzard on the apparently unstoppable expansion of the Asian Hornet, but it seems wise to favour the presence of this raptor.

The bioaccumulation process means that raptors are highly sensitive to pollutants and, in the case of the European Honey Buzzard, it has been reported the presence of neonicotinoids in the blood (Byholm et al. Citation2018 and references therein); a group of insecticides which have negative effects on birds (Millot et al. Citation2017 and references therein). This underlines the need to eliminate from the natural environment the wasp colonies treated with pesticides (Beggs et al. Citation2011), a practice that is frequently ignored or even discouraged by the official protocols (e.g. those issued by the Government of Catalonia in 2018).

The discovery here reported highlights the need for research on the breeding biology of the European Honey Buzzard, one of the less well-studied raptors in Europe (Hagemeijer & Blair Citation1997), with the aim of obtaining detailed information on its ecological relationship with the Asian Hornet and the derived consequences for the populations of both species.

Acknowledgements

We thank Toni Arrizabalaga and Constantí Stefanescu (Museu de Ciències Naturals de Granollers) for putting in contact the authors. Eric Corella, Xavier Larruy, José Moreno and Ramón Sanz help in the fieldwork. Diputació de Barcelona and the Parc de la Serralada Litoral, Parc de la Serralada de Marina and Parc del Montnegre i el Corredor supported the fieldwork. Permits were kindly issued by Servei de Fauna i Flora de la Direcció General de Polítiques Ambientals i Medi Natural. We are grateful to Cos d’Agents Rurals del Departament d’Agricultura, Ramaderia, Pesca i Alimentació, who provided records for the Asian Hornet.

References

- Becking, J.H. 1989. Henri Jacob Victor Sody (1892–1959): His Life and Work: a Biographical and Bibliographical Study. Brill Archive, Leiden.

- Beggs, J.R., Brockerhoff, E.G. Corley, J.C., Kenis, M., Masciocchi, M., Muller, F., Rome, Q. & Villemant, C. 2011. Ecological effects and management of invasive alien Vespidae. BioControl 56: 505–526. doi: 10.1007/s10526-011-9389-z

- BirdLife International. 2004. Pernis apivorus. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2004. Downloaded on 17 May 2019.

- Byholm, P., Mäkeläinen, S., Santangeli, A. & Goulson, D. 2018. First evidence of neonicotinoid residues in a long-distance migratory raptor, the European honey buzzard (Pernis apivorus). Sci. Total Environ 639: 929–933. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2018.05.185

- Carlsson, N.O., Sarnelle, O. & Strayer, D.L. 2009. Native predators and exotic prey–an acquired taste? Front. Ecol. Environ 7: 525–532. doi: 10.1890/080093

- Dincă, V., Runquist, M., Nilsson, M. & Vila, R. 2013. Dispersal, fragmentation and isolation shape the phylogeography of the European lineages of Polyommatus (Agrodiaetus) ripartii (Lepidoptera: Lycaenidae). Biol. J. Linnean Society 109: 817–829. doi: 10.1111/bij.12096

- Gamauf, A. 1999. Der Wespenbussard (Pernis apivorus) ein Nahrungsspezialist? Der Einfluß sozialer Hymenopteren auf Habitatnutzung und Home Range-Größe. Egretta 42: 57–85.

- Hagemeijer, E.J.M. & Blair, M.J., (eds) 1997. The EBCC Atlas of European Breeding Birds: Their Distribution and Abundance. T & AD Poyser, London.

- Hake, M., Kjellén, N. & Alerstam, T. 2003. Age-dependent migration strategy in honey buzzards Pernis apivorus tracked by satellite. Oikos 103: 385–396. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0706.2003.12145.x

- Hardey, J., Crick, H., Wernham, C., Riley, H., Etheridge, B. & Thompson, D. 2013. Raptors: A Field Guide to Survey and Monitoring. 3rd edn. The Stationery Office, Edinburgh.

- Haxaire, J., Bouguet, J.P. & Tamisier, J.P. 2006. Vespa velutina Lepeletier, 1836, une redoutable nouveauté pour la faune de France (Hym., Vespidae). Bull. Soc. Entomol. Fr 111: 194–194.

- Macià, F.X., Larruy, X., Grajera, J. & Mañosa, S. 2017. Mida poblacional i densitat de rapinyaires forestals a la Serralada Litoral. In III Trobada d’Estudiosos de la Serralada Litoral Central i VII del Montnegre i el Corredor, 260–273. Diputació de Barcelona, Barcelona. https://www1.diba.cat/llibreria/pdf/58237.pdf.

- Mack, R.N., Simberloff, D., Lonsdale, W.M., Evans, H., Clout, M. & Bazzaz, F.A. 2000. Biotic invasions: causes, epidemiology, global consequences, and control. Ecol. Appl 10: 689–710. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2000)010[0689:BICEGC]2.0.CO;2

- Millot, F., Decors, A., Mastain, O., Quintaine, T., Berny, P., Vey, D., Lasseur, R. & Bro, E. 2017. Field evidence of bird poisonings by imidacloprid-treated seeds: a review of incidents reported by the French SAGIR network from 1995 to 2014. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res 24: 5469–5485. doi: 10.1007/s11356-016-8272-y

- Monceau, K., Bonnard, O. & Thiéry, D. 2014. Vespa velutina: a new invasive predator of honeybees in Europe. J. Pest. Sci 87: 1–16. doi: 10.1007/s10340-013-0537-3

- Pujade-Villar, J., Torrell, A. & Rojo, M. 2012-2013. Confirmada la presència a Catalunya d’una vespa originària d’Àsia molt perillosa per als ruscs. Butll. Inst. Cat. Hist. Nat 77: 173–176.

- Rome, Q., Muller, F.J., Touret-Alby, A., Darrouzet, E., Perrard, A. & Villemant, C. 2015. Caste differentiation and seasonal changes in Vespa velutina (Hym.: Vespidae) colonies in its introduced range. J. Appl. Entomol 139: 771–782. doi: 10.1111/jen.12210

- Sergio, F., Marchesi, L., Pedrini, P. & Penteriani, V. 2007. Coexistence of a generalist owl with its intraguild predator: distance-sensitive or habitat-mediated avoidance? Anim. Behav 74: 1607–1616. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2006.10.022

- Schmitz, O.J., Hamback, P.A. & Beckerman, A.P. 2000. Trophic cascades in terrestrial ecosystems: a review of the effects of carnivore removals on plants. Am. Nat 155: 141–153. doi: 10.1086/303311

- Smit, J., Noordijk, J. & Zeegers, T. 2018. De opmars van de Aziatische hoornaar (Vespa velutina) naar Nederlant. Entomol. Ver 78: 2–6.

- van Manen, W., van Diermen, J., van Rijn, S. & van Geneijgen, P. 2011. Ecologie van de Wespendief Pernis apivorus op de Veluwe in 2008-2010 Populatie, broedbiologie, habitatgebruik en voedsel. Natura 2000 rapport, Provincie Gelderland Arnhem NL / stichting Boomtop www.boomtop.org Assen NL.

- Vigneaud, J.P. 2013. Gironde: fait rarissime, un rapace dévore un nid de frelons asiatiques. Sud Ouest 20/08/2013. https://www.sudouest.fr/2013/08/20/le-tueur-de-frelons-1145390-2777.php. Accessed on 13 August 2019.

- Villemant, C., Rome, Q. & Haxaire, J. 2010. Le Frelon asiatique (Vespa velutina). In Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle [Ed]. 2010. Inventaire national du Patrimoine naturel, site Web. https://inpn.mnhn.fr. Traducción Juli Pujade-Villar. Accessed on 13 August 2019.

- Voskamp, P. 2000. Population biology and landscape use of the Honey Buzzard Pernis apivorus in Salland. Limosa 73: 67–76.