ABSTRACT

Understanding students’ learning dispositions has been a focus for research in education for many years. A range of alternative approaches to conceptualising and measuring this broad construct have been developed. Traditional psychometric measures aim to produce scales that satisfy the requirements for research; however, such measures have an additional use – to provide formative feedback to the learner. In this article we reanalyse 15 years of data derived from the Effective Lifelong Learning Inventory. We explore patterns and relationships within its practical measures and generate a more robust, parsimonious measurement model, strengthening its research attributes and its practical value. We show how the constructs included in the model link to relevant research and how it serves to integrate a number of ideas that have hitherto been treated as separate. The new model suggests a view of learning that is an embodied and relational process through which we regulate the flow of energy and information over time in order to achieve a particular purpose. Learning dispositions reflect the ways in which we develop resilient agency in learning by regulating this flow of energy and information in order to engage with challenge, risk and uncertainty and to adapt and change positively.

1. Introduction

The concept of learning power and its assessment tool, the Effective Lifelong Learning Inventory (ELLI), was developed in the late 1990s. It was the outcome of research that tested constructs suggested within the literature of the time as having some relevance for the establishment of dispositions, attitudes and values associated with being an effective learner. The result was both a measurement model and a set of research-validated strategies. Both have proven to be of value for education, business and corporate organisations seeking to innovate in how they support individual and collaborative learning. In contrast to the skill-based approach that became popular during the same period, the concern with learning power was to develop a range of competences crucial for success in the complex, networked, information-rich and radically uncertain world of the emerging twenty-first century. These competencies are now to the forefront – forming the outcomes focus for institutions and organisations the world over. Unsurprisingly then, since the first assessment tool was published in 2002, it has been in significant demand from both practitioner and research users.

The scientific foundation for the research programme that led to the development of the ELLI emerged from the synthesis of two concepts: (i) learning power and (ii) assessment for learning. The original research was funded by the Lifelong Learning Foundation. The research questions were (i) Can we identify the qualities and characteristics of people who are able to engage effectively with new learning opportunities? and (ii) If we can answer question (i), can we develop an approach to assessment that will enable students and teachers to focus on strengthening students’ ability to learn? The overall vision of the funders and the aims of the research were to provide a practical challenge to the then dominant focus on high stakes, summative testing and assessment that, the evidence suggested, actually depressed students’ motivation for learning (Harlen and Deakin Crick, Citation2003a, Citation2003b). The focus from the beginning was on the production of research that would impact on practice in classrooms.

An exploratory quantitative research design was selected to answer question (i). First, a literature review and a practitioner-and-expert consultation identified constructs that would be candidates for inclusion in the construction of a questionnaire. This review explicitly incorporated a sociocultural theoretical perspective which assumed that students’ engagement in the processes of learning would be influenced by the quality of relationships and the social practices of classrooms and schools. In addition to this it incorporated the Vygotskyan notion of ‘perezhivanie’ – the cognitive and affective experience that students bring to the classroom which reflects the personal and environmental characteristics of the student’s particular family, community and tradition (Mahn and John-Steiner, Citation2002). The resulting questionnaire produced an initial data set (N = 2000) for interrogation through exploratory factor analysis to identify any latent variables that would summarise the data and provide a basis for the development of assessment strategies. The reduction of this broad data set to a set of latent variables which ‘summarised’ it was particularly significant for practice. Typically the range of ‘literatures’ in educational research creates a challenge for practitioners who wish to be research-informed because there are different traditions, which focus on specific and apparently different aspects of learning while, in classrooms, teachers deal with complexity and unpredictability. In these conditions an understanding of these different aspects of learning and how they relate together at an appropriate level of generality is an important pedagogical skill in practice.

Although there is a range of studies which have identified variables that have an impact on the individual’s capacity and motivation to learn, such as self-esteem, locus of control, learning dispositions, goal orientations, learning styles and intrinsic versus extrinsic motivation … few attempts have been made to explore the notion of the conglomerate of variables as they might operate in persons in particular social contexts, and in particular trajectories in time. Thus the study reported here arguably breaks new ground in its attempt to begin to identify these variables and the relationships between them. It is an attempt to be able to provide working hypotheses about the ecology of variables that together make up an individual’s learning orientation. (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2004, p. 249)

Both the research and practical purposes were thus addressed within this design (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2002a, Citation2002b). The factor analytic studies identified seven latent variables and established scales to measure them (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2004). These variables were described as ‘qualities necessary for learning’, and they informed the first iteration of the ELLI self-assessment instrument – changing and learning: growth orientation, meaning making, critical curiosity, resilience, creativity, learning relationships and strategic awareness (2004, p. 259). One criticism of the set of scales (unpublished) was in the reported degree of shared variance between these scales and thus their construct validity. For academic research use this was undesirable but in a measurement model designed to reflect back to students what they said about themselves as learners – and whole people – it was more authentic and thus fit for purpose.

The second part of the research was addressed by a qualitative phase in which three schools, 12 teachers and a total of 380 students, selected from the original study, were provided with data for each individual student and mean scores for each group, from the ELLI questionnaire. Teachers were invited to use these data in learning design in their regular teaching during the following year. Classroom practices, in which both teachers and students participated, were studied during the year, including the teachers as ‘co-researchers’. The following pedagogical themes were identified as significant: (i) teacher commitment to learner-centred values and willingness to make pedagogical judgements; (ii) positive interpersonal relationships characterised by trust, affirmation and challenge; (iii) development of a language for learning particularly using metaphor and image; (iv) modelling by teachers of learning power and imitation of teachers’ or other ‘experts’’ behaviour by students; (v) active learning dialogue; (vi) personal and collaborative reflection on learning power; (vii) the development of learner self-awareness and ownership of their own learning power; (viii) student choice and responsibility for learning decisions and (ix) re-sequencing of the content of the curriculum to support enquiry-based learning. These themes were supported by a range of strategies and skills for developing learning power, either drawn from National guidance or organically developed by the schools themselves (Deakin Crick, Citation2007).

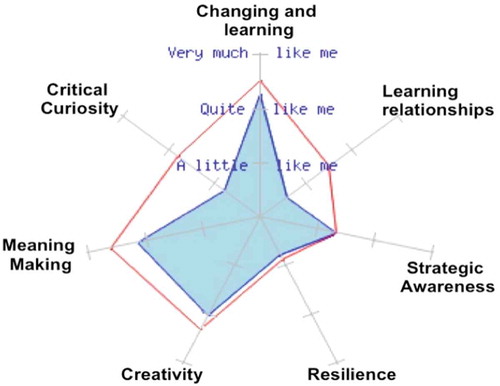

ELLI assessment data included aspects of a person’s learning that were both ‘internal’ and ‘social’ – influenced by a person’s sense of ‘self’ in a sociocultural and historical context. Feedback was in the form of an immediate visual image of an individual’s learning ‘profile’ as a spider diagram. This provided a framework for a coaching conversation which moved between the coachee’s identity as a learner and his or her learning experiences and purposes. The ELLI instrument was designed to identify and strengthen an individual’s learning dispositions, attitudes and values and provide a starting point for self-directed learning and teacher-facilitated pedagogical change. The coaching conversation created ‘space’ for individuals to identify their unique sense of identity as a learner and to begin to ‘own’ and formulate a particular purpose or desired outcome. With skilled pedagogical interventions, these conversations formed a starting point for the individual to determine what they wanted to achieve in a learning context (why) and how they would go about achieving that purpose (how). The responsibility for the processes of learning shifted from the teacher to the learner.

The second phase of the original research created significant practitioner interest as well as commercial interest in the instrument. From 2003 its development trajectory continued on three distinct pathways – university-led research, practitioner-led research and development and commercialisation. Each pathway had its own governance mechanisms, and various attempts were made to link them through the concept of an Advisory Board constituted to reflect and respect research, practice, policy and enterprise. This article reports on two of these tracks – university-led research and practitioner-led research and development.

Ongoing research explored learning and teaching facilitation strategies which enable individuals to become responsible, self-aware learners by responding to their learning power profiles. For example the Learning Futures mixed methods case study (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2010b; Deakin Crick et al., Citation2011) explored the relationships between teacher facilitation of enquiry-based learning and the development of learning power and from a stratified sample of students with ‘low, medium and high’ levels of reported learning power undertook a narrative study of student learning identities (Deakin Crick and Goldspink, Citation2014). The relationship between the sequencing of the curriculum and the development of learning power in enquiry-based learning was explored in qualitative studies, the context of learning with disengaged and gifted and talented students in action enquiries (Deakin Crick, Citation2009a), in a mixed methods evaluation of postgraduate teaching on sustainable systems in engineering (Godfrey et al., Citation2014) and theoretically (Deakin Crick, Citation2009b; Jaros and Deakin Crick, Citation2007). Qualitative studies undertaken in Australia with indigenous communities enabled a deeper qualitative and narrative exploration of the ubiquitous use of metaphor, narrative and image – visual literacy – in the development of learning power (Deakin Crick and Grushka, Citation2009; Goodson and Deakin Crick, Citation2009; Grushka, Citation2009). An explorative quantitative study reported on the ecology of learner-centred variables in complex classroom contexts which interact with learning power (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2007a). Huang’s (Citation2014) mixed methods case study explored the contribution of learning power to authentic pedagogy and its role in classrooms as complex adaptive systems. Coaching for learning emerged as a key strategy for change in a person’s learning identity in two mixed methods studies (Aberdeen, Citation2014; Ren, Citation2010; Wang, Citation2013) explored the relationship between a teacher’s own self-reflection on his or her learning power and its impact on his or her practice.

Two major quantitative reliability and validity studies were conducted to test the original scales on data that were collected through research and practitioner use of the instrument. This enabled the development of an adult version of the instrument (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2013; Deakin Crick and Yu, Citation2008) and demonstrated the stability of the scales across domains and cultures, enjoying considerable face validity with school-age students and adult learners and corresponding acceptance with both populations. These studies also demonstrated that reported learning power drops significantly as children get older and increases as adults mature. Distinctive patterns of learning power profiles were demonstrated in underachieving students (Ren, Citation2010; Ren and Deakin Crick, Citation2013), in young people with prosocial values (Arthur et al., Citation2006) and antisocial values (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2014).

Demand for access to ELLI from users was such that it has been translated into German, Italian, Chinese, Arabic and Malay. It has again enjoyed face validity in those contexts although full re-validation tests have not yet been conducted (Deakin Crick and Ren, Citation2011; Ren and Deakin Crick, Citation2012). It has been applied to schools, to work-based learning, piloted with a major UK retailer; a bank and in the financial services industry (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2013; Deakin Crick and Davies, Citation2014); Indigenous Australian communities (Willis, Citation2014); the education of young offenders (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2014; Deakin Crick and Salway, Citation2006); leadership studies (Ritchie and Deakin Crick, Citation2007); engineering education (Godfrey et al., Citation2014) and teaching in higher education (Harding and Thompson, Citation2011; Small and Deakin Crick, Citation2008).

Reflection on this evidence, and on practitioner experience accumulated over this period of time (Deakin Crick, Citation2006) (which is generally not reported in academic contexts), supported and extended the original qualitative findings from phase 2 of the original research study, particularly by focusing on coaching relationships, enquiry-based learning and authentic pedagogy, as pedagogical practices which encourage individuals to take responsibility for their own learning. In our view the value of the instrument was in providing a specific measurement model, a conceptual framework, a language with which to describe a complex ‘messy’ human process and an assessment technology that permitted the use of research data for stimulating self-directed change. It thus provided specificity, assess-ability and rigour to the conceptually and empirically complex social processes implicated in effective learning. The same data points were useful for practice as well as for organisational improvement research and for more fundamental university-led research – thus organically promoting a networked improvement community whenever it was used in this way.

Nothing, however, stays static and with the accumulation of deeper and richer data from this wide range of contexts, as well as of experience of working with the constructs with learners in the field, limitations in the original conceptualisation of learning power became increasingly evident. In particular the relationships between the seven scales were problematic. The R&D programme and to an extent the commercial programme required organisations to undergo training in the use of the instrument as a means of quality assurance. Despite this, it was clear that there was a tendency on the part of teachers and providers of the survey to focus on ‘resilience’ at the expense of other scales, and although the researchers would argue that the profiles should be understood as a ‘whole’, we had not undertaken a statistical exploration of the internal structure of learning power and the relationships between the scales. In particular, the assumption that people reporting themselves as ‘not at all fragile and dependent’ must therefore be ‘resilient’ generated serious research questions. These issues are discussed in more detail later.

At the same time the development of more sophisticated data capture, analysis and delivery systems gave rise to new possibilities for both research, development and practice and more demand from entrepreneurs. The challenge of an integrated approach to impact-oriented research became more important as an ethical issue – the wider the take-up of the instrument, the more important it was to have a vibrant, generative research agenda to inform it. This was particularly important because the instrument itself stimulated learning at leadership, teacher and student levels through the provision of rapid feedback and helped to develop data literacy on the part of teachers, leaders and managers: a key skill in the digital era.

2. Learning Analytics and the Generation of Data

In making available both research and immediate, visual, diagnostic information for self-directed change, ELLI provided an early example of a learning analytic tool (Buckingham Shum and Deakin Crick, Citation2012). Learning analytics is an emerging practical field of study which refers to the ways in which computational support for capturing digital data can help to inform decision making for the processes and outcomes of learning (Buckingham Shum, Citation2012). Key to this is the rapid feedback of data to users at all levels of the system and the capability of technology to re-present complex data visually. ELLI represented an early example of an online learning analytic platform, which provided data useful for feedback at four levels (individuals, teams, organisations and system). The level of demand it enjoyed has enabled the accumulation of a large data set which has been collated and archived at the University of Bristol. A 3-year research programme for mining and exploring this secondary data set has now been established. This includes an ongoing research programme to extend, replicate and validate the measures, including in alternative cultural contexts, to generate new knowledge and know-how and also to explore the affordances of this type of survey in the emerging field of learning analytics.

In the context of virtual learning ecologies, data from such surveys can be analysed alongside other data – such as trace data of the behaviour of people in virtual environments – to inform the use of technology to support deep learning and learning to learn – at all stages of the learning journey from purpose to performance (Deakin Crick, Citation2012, Citation2014). The challenge was, and remains, the development of a robust learning analytic that can be used in practice across domains and cultures and stimulate self-directed learning at all levels. It was therefore decided that the revised framework and associated tools be kept in a research phase for at least 3 years and to quarantine the development from commercialisation pressures which might tend to short-circuit the redevelopment effort during that period through an approach to the generation of value that does not serve all the stakeholders’ needs.

3. Purpose of This Paper and Hypotheses Generation

This article addresses the first priority of this 3-year research phase. It represents a thorough re-examination of the internal structure of ‘learning power’. The factors that led to this re-examination have been discussed earlier – questions that emerged about the internal structure of learning power through its ongoing application and ensuing rich data collection and the ethical need for an integrated approach to research-led practice which generates wider stakeholder value.

Our extensive experience of working with ELLI enabled us to form tentative hypotheses about the deeper structure of learning power, the relationship between its various aspects and the sensitivity of the dimensions of learning power to individual and contextual factors. This experience had also highlighted several problems or dilemmas with the existing framework which could be explored and hopefully resolved through this work. The developing hypotheses were developed in an international research community that had extensive experience in working with ELLI over time and in different cultural contexts (see, e.g., www.learningemergence.net) theoretically, empirically and practically. The comparison of ELLI data with data from the Teaching for Effective Learning Project in South Australia, for example, led to our understanding that learning identity and openness to learning were critical prerequisites for learning (Deakin Crick and Goldspink, Citation2014; Deakin Crick et al., Citation2013; Goldspink and Foster, Citation2013). An early unpublished study in prisons gave cause for concern about the concept of resilience as represented in the original ELLI structure (Deakin Crick and Salway, Citation2006) with an emerging hypothesis that to become resilient a person needed to utilise all the learning power dimensions over time. The quantitative studies (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2004, Citation2013; Deakin Crick and Yu, Citation2008) demonstrated a coherent pattern within the ‘active learning power dimensions’ and their relationship with desirable learning outcome variables. ‘Learning relationships’ as a scale had less discriminatory power statistically. In summary we hypothesised that:

The set of active learning power dimensions were related to each other.

Strategic awareness was predictive of the active learning dimensions.

Learning relationships could work negatively and positively – towards both dependence and isolation and towards challenge and change.

Learning identity and trust were foundational in determining whether people would engage at all.

Resilience was about the ability to adapt and change positively in response to challenge and therefore was a complex construct which drew on all the other learning power dimensions.

The extensive and diverse data set, with records from individuals of all ages and from a range of cultures, enabled us to test these hypotheses systematically. In this article we explore the sub-components of each learning power scale statistically and theoretically, then present a revised set of eight new and more parsimonious scales with levels of reliability similar to those in the original ELLI instrument.

A powerful influence on the development of the working hypotheses was the community’s engagement with complexity theory, and this forms the focus of the next section.

4. Theoretical Starting Point: Learning as a Complex, Dynamic Process

This work has led us to conclude that whilst the concept of learning power captures a number of salient dispositional characteristics of more or less effective learners, these form part of a complex and dynamic process of learning which has lateral and temporal connectivities (Bloomer, Citation2001; Bloomer and Hodkinson, Citation2000). This complexity is not only ‘intra–personal’ and ‘inter-personal’ but also social and organisational – that is, it is significantly influenced by the social organisations, cultural practices and world views of the learning contexts in which learners find themselves (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2011; Ren, Citation2010; Ren and Deakin Crick, Citation2013; Tracy, Citation2014). This realisation led us to develop a conceptual framework of learning as a complex process, whose boundaries are defined by a purpose, and which operates recursively at different layers and levels in social organisations which are themselves characterised by socio-technical and political complexity (Buckingham Shum and Deakin Crick, Citation2012; Buckingham Shum and Ferguson, Citation2011; Deakin Crick et al., Citation2014; Ferguson and Buckingham Shum, Citation2011; Ullmann et al., Citation2011). Drawing on work in systems designing from engineering (Blockley, Citation2010; Blockley and Godfrey, Citation2000), we developed a complex systems architecture for learning journeys which valorises the identification of a personally chosen purpose, that is integrated and internalised by the learner as a prerequisite for meaningful learning. A complex systems architecture is a conceptual framework that sets out the key parts of a system, what they do and how they fit and work together. Thinking about learning as a complex system allows us to theorise and test a holistic understanding of learning:

A system is a group of parts that interact so that the system as a whole can do things the parts can’t do on their own. This property of systems is called emergence – “the whole is more than the sum of its parts.” A system can include people, organisations, technology, information, processes, services, and nature. (Sillitto, Citation2015, p. 4) (Bold in original)

Whilst logically simple, the importance of purpose is often overlooked in education systems where choice about what, or even how to learn, is limited. Its importance as a contextual factor was also frequently overlooked in the various attempts to commercialise ELLI as a product in the market during this time. Outside of formal education or training, where the curriculum and pedagogy are too often politically determined, effective learning requires the identification of personal desire or purpose, in response to first identifying a need or a problem that requires a solution of some sort. Learning that begins from this point in lived, concrete experience is ‘bottom up’ and usually both interdisciplinary and inter-domain – in other words it transgresses traditional subject boundaries (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2007b; Jaros, Citation2009a, Citation2009b; Jaros and Deakin‐Crick, 2007). Articulating a purpose in learning requires that I or we know something about ourselves, our story and what is of value to us, and it is thus associated with identity as well as a particular time and place (Deakin Crick and Goldspink, Citation2014; Deakin Crick and Jelfs, Citation2011; Deakin Crick et al., Citation2011).

There are five social processes that enable an understanding of learning as a journey of enquiry from purpose to performance, discussed at length elsewhere (Deakin Crick, Citation2014). These are

forming a learning identity and purpose

developing learning power

generating knowledge and know-how

applying or performing learning in authentic contexts

sustaining learning relationships

As we have noted elsewhere, formal education generally focuses on the third of these, leaving the others essentially untreated. However, all five processes are pedagogically significant for the core tasks of (i) designing contexts for learning and (ii) facilitating learning for individuals and groups who support the development of learning power and resilient agency – learners who can persist in learning, responding effectively to open-ended and complex problem spaces, as demanded by 21 C learning outcomes.

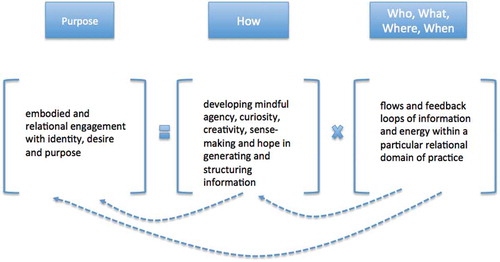

This understanding led us to problematise the relationship between the active learning power dimensions of ELLI and the dimensions of strategic awareness, fragility and dependence, and learning relationships. The ELLI spider diagram presented all of the dimensions as if they have similar status and a simple relationship to one another, encouraging a reductionist interpretation. We became more and more convinced that this was not the case as more data from a range of contexts were collated. It was most clearly problematic in a pilot study with young offenders in a secure unit (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2014; Deakin Crick and Salway, Citation2006). It was this shift from a reductionist to a complexity perspective on learning power that led us to focus on the concept of ‘agency and purpose’ as a key driver of learning, as a dynamic and relational process. A complex ‘systems architecture’ for this process, drawing on Blockley (Citation2010) and discussed elsewhere (Deakin Crick, Citation2014), is set out in . This figure sets out the relationships between core processes in learning as a complex system, in a way which encourages understanding and analysis of the parts as they relate to each other in the whole process. It uses the equation format as a metaphor to show relationships between the parts. In understanding a complex system, it is first important to find out what its purpose is – and from that purpose it is then possible to define boundaries, to generate a measurement model to evaluate success and to explore the ‘how’, or the processes that are important to achieving the purpose. In this model, the purpose of a learning journey can be identified through the individual’s intention, purpose or desire and the energy with which they pursue it. Their learning power enables them to interrogate their purpose and to identify ways in which to navigate a journey to a selected outcome – the ‘how’. The ‘what’, ‘where’, ‘when’ and ‘who’ represent the ‘domain of enquiry’: the territory through which the learner will co-generate new knowledge, through encountering the flow of data, energy and information which is uncovered in a particular territory.

Figure 1. A complex systems architecture with purpose as a key driver of learning (adapted from Blockley, Citation2010 by Deakin Crick)

An important caveat to the way this model is presented is that although logically it begins with purpose – and there is evidence to suggest that individuals with no purpose or desire are unlikely to learn much, especially in formal contexts – a complex system assumes there is a multiplicity of systems at work. In practice, the entry point for understanding or intervention in a learning process could be at any point in the process and could be influenced by a number of external systems. These are inherently difficult to predict – since the orders of emergence in human social systems are exponentially complex compared to orders of emergence in natural systems (Goldspink and Kay, Citation2009). This is why teaching and learning is not successful when stakeholders are simply ‘following a script’ and why successful teaching is more like a design process in which teachers respond and adapt in context to the needs of learners as they emerge (Furlong et al., Citation2000).

This model presents learning as a sequential process with iterative feedback loops that operate through the relationships between self, others and the environment. It begins with the person who is learning and his or her sense of purpose or desire. This provides the energy to engage in learning as a journey that takes place in a particular context, over time. A person is influenced by his or her perceptions of context as well as by his or her own processes of learning (Huang, Citation2014). Teachers or learning facilitators can have a direct influence on the context of learning; they can scaffold the processes of knowledge structuring and increasing awareness of learning power, whilst agency cannot be imposed or conferred by other people. Rather, it is an emergent property of the recursive interactions between self and context. This model has guided the development of hypotheses and their testing against the data set which we shall now describe (Furlong et al., Citation2000; Goldspink and Kay, Citation2009).

5. The Data Set

The data were taken from four online sources, each originally developed to serve various ELLI research and development programmes over a period of 10 years, between October 2003 and June 2013. The number of items being served to participants varied between sources and versions, but each source and version contained the core ELLI items relevant for adult and school-age learners, standardised in terms of administration and representation in each database. The respondents were drawn from 190 organisations in six countries, representing a variety of sectors including institutes of higher education; training organisations; private sector corporations; staff from primary, secondary and further education; and students in schools and colleges. Each adult participant undertook his or her own learning power profile as part of their accreditation training to enable them to incorporate learning power in their professional development practice, to brief others within that organisation and as part of their own personal development. Each school-aged participant undertook his or her learning power profile as part of a formal learning programme, supervised by a trained facilitator. This analysis used a sample of 50,314 that is described in .

TABLE 1: Description of the data sample

Indicative demographics of the sample are presented in and . It should be noted that the submission of participant biodata was not a mandatory requirement, and as a result these tables do not include data from the entire sample. The potential for bias in the reporting of such data is recognised.

TABLE 2: Distribution of respondents by gender

TABLE 3: Distribution of respondents by ethnicity

6. Ethical Considerations

All of the adults who provided survey data did so voluntarily and agreed to allow their anonymised data to be stored for research purposes through an explanation online and prior to the survey, which they then agreed to by ‘click box’. School-age children completed the survey in accordance with their school’s ethical policies, and no schools were able to use the ELLI survey without accredited training. Anonymised learning power assessment data were stored in a secure online repository, whilst user-identifying data, needed for the personalised feedback, were stored separately, under the control of the user organisation. Personalised feedback was provided immediately online and formed a focus for a coaching conversation with each individual, led by an accredited learning power coach in the case of adults and by an accredited teacher in the case of children, or in a coaching programme supervised by an accredited teacher.

7. The Original Measures

The ELLI was a self-report questionnaire in which respondents indicated their approach to various aspects of learning through completion of an online 4-point Likert-type questionnaire (Likert, Citation1932). The items in the questionnaire elicited information about what the individual thinks, feels and tends to do in relation to everyday learning situations. The respondents’ judgements in responding to the items were based on their own experiences, past and present, including the context in which they found themselves at the time they completed the questionnaire. The scales for the seven dimensions of learning power were calculated online and used to produce feedback for the individual characterising his or her perception of his or her own learning power on these dimensions in the form of a spider diagram shown in . The scores were produced as a percentage of the total possible score for that dimension.

The instrument was designed to find a balance between use for developmental intervention and for research as discussed in the introduction. With regard to the latter application, the alpha reliability coefficients for the scales in the existing instrument, based on two different data sets of >10,000 and <6000 are presented in .

TABLE 4: Alpha coefficient of the existing ELLI instrument

8. Approach to Analysis

The original design work for ELLI and the subsequent confirmatory factor analysis consistently demonstrated a three-part structure to the original scales: (i) active learning power dimensions determined by strategic awareness, including creativity, curiosity, meaning making and changing and learning; (ii) learning relationships and (iii) fragility and dependence. One of the aims of revisiting the measures, using the large data set discussed earlier, was better to understand the internal structure of each of this three-part structure as well as the relationship between the parts.

The data were split into two randomised sets. We used the first set to conduct exploratory factor analyses of each of the scales, to explore their internal structure and to identify whether there were any latent variables present. Where latent variables were identified, we confirmed the structure on the second half of the data set using structural equation modelling. Items that did not fit were abandoned. We then modelled each of the three parts separately before combining them into a single model. Only the structural equation modelling is discussed in detail here.

Structural Equation Modelling

Analysis was undertaken using AMOS 19. Maximum likelihood estimation was used. For the following analyses the position of (Hu and Bentler, Citation1999) is adopted with respect to determination of fit. It is generally not expected that the Chi-square minimum discrepancy statistic will prove insignificant (p < 0.05) thereby confirming fit where larger sample sizes are involved. In such cases, the less stringent comparative fit index (CFI) and root mean square of approximation (RMSEA) statistics are generally used. For the model to be accepted as in fit, the CFI needed to be >0.95 and/or the RMSEA <0.05. The data presented later represent standardised measures. Standardisation is achieved by setting one factor loading to 1. All analyses are performed on the covariance matrix.

9. The Active Learning Power Dimensions

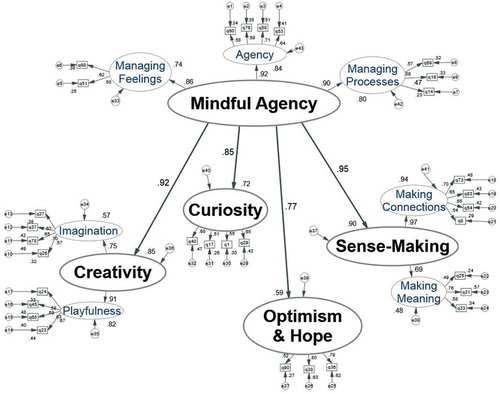

Our first analysis was on the internal structure of the ‘strategic awareness’ construct used in ELLI. This is renamed ‘mindful agency’ in the revised instrument as a result of the analysis and redesign of the scales as discussed later. The exploratory factor analysis of the items associated with the strategic awareness latent variable returned three factors which we have called: (i) managing the processes of learning, (ii) managing the feelings associated with challenge and (iii) agency in taking responsibility for learning purposes, processes and procedures. These items were used to construct the Structural Equation Model shown in .

This suggests a tripartite structure for mindful agency, which is about the self as agent of his or her own learning, able to take responsibility for the process, as well as managing feelings in learning (such as feeling confused) and being able to judge how long something may take and how to go about it (meta-cognitive strategy). This serves to integrate three distinct strands in the research literature: meta-cognition, the role of affect in self-regulation (emotional intelligence) and self-efficacy or agency, as will be discussed further later in text.

The model is in good fit (RMSEA = 0.031; CFI = 0.984) and demonstrates that mindful agency accounts for 81% of the variance in agency, 72% of the variance in managing feelings and 85% of the variance in managing processes of learning.

The resulting scale returned an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.78 with nine items presented in .

TABLE 5: Mindful agency scale1

Each of the three components of mindful agency should be uncontroversial as they have long been associated with processes of learning and with improved learning outcomes. Although they are not always brought together in the literature, there are prior instances of where these elements have been directly associated. Bown (Citation2009, p. 578) states for example that self-regulative learners are those who are aware of themselves as active agents who are then able to exercise that agency through various strategies to actively shape and construct their learning experiences as well as their motivational and affective responses. Similarly Mercer, drawing on a detailed longitudinal study of a particular learner, observed that ‘…three components of Joana’s agentic system appear to play a more significant role… in directing the trajectory of her agency: motivation, affect and self-regulation (including goals, meta-cognitive knowledge, and strategic knowledge)’ (2011, pp. 432–433).

Of the three constructs, agency is likely to be the most problematic. This concept gets caught on the horns of the ‘free-will versus determinacy’ dilemma which, even in its more moderate form, leads to argumentation about how the independent will of individuals sits alongside the constraints resulting from the wider social context. Nevertheless it frequently appears within the educational literature (Etalapelto et al., Citation2013). It refers to the implicit or explicit (Moore et al., Citation2012) sense of initiating and controlling events – the will and capacity to act and to influence others or the environment. This is in contrast to the adoption of a sense of having no control over one’s own destiny and taking a passive or reactive stance to events and others. This presupposes a sense of self-efficacy and hence links to the extensive education-related literature on that subject (Bandura, Citation1982, Citation1986, Citation1994a; Schunk, Citation1987; Zimmerman et al., Citation1992).

The role that managing feelings plays in relation to learner effectiveness is also well addressed in the literature, most notably with regard to the concept of emotional intelligence. This literature addresses the different capacities individuals have to regulate their own emotions and/or to detect and influence those of others upon whom attainment of their goal depends. Emotional intelligence has been shown in some studies to predict academic achievement across a wide range of age groups (see, e.g., Billings et al., Citation2014; Mohzan et al., Citation2013; Sanchez-Ruiz et al., Citation2013). Emotion may however play a much broader role, as Morse and Lowe (Citationn.d.) argue, drawing on the developing theory of enactive cognition (Varela et al., Citation1991) as well as the neuroscience of Damasio (Citation2000, Citation2006), ‘emotion may be seen as a form of motivated disposition the adaptive benefit of which is to assist the holder to anticipate and respond appropriately to presenting challenges’. Perhaps most importantly, following Fredrickson et al. (Fredrickson, Citation2001; Fredrickson and Joiner, Citation2002; Fredrickson and Losada, Citation2005), emotions may have the implication of disposing someone to be open to new learning – to approach the unknown – or closed to it. Positive emotions have been shown to ‘broaden peoples’ momentary thought-action repertoires and build their enduring personal resources’ (Fredrickson, Citation2001, p. 222).

Finally, it is again uncontroversial to argue that individuals differ in their ability to exercise judgement about how effective they are being in their chosen approach to learning (meta-cognitive monitoring) and/or to exercise effective control over their choice of learning strategies (meta-cognitive control). Again there is a substantial literature (Andrade, Citation1999; Blakey and Spence, Citation1990; Coutinho and Neuman, Citation2008; Dunlosky and Metcalfe, Citation2009; Kitchener, Citation1983, Veenman et al., Citation2006, Vrugt and Oort, Citation2008) that deals with these from the perspective of heuristics linked to specific disciplines through to the underlying neuroscience. However, Efklides (Citation2006) argues that meta-cognitive experience – especially feelings – guide subsequent choices about strategy. As well as feelings of familiarity, difficulty, knowing, confidence and satisfaction, these experiences include judgements about how much effort will be required to learn something and how much time it may take (aligning directly with the items included in the ‘managing process’ construct). These meta-cognitive feelings and judgments ‘…are products of nonanalytic, nonconscious inferential processes particularly when there are conditions that do not allow full analysis of the situation such as… under conditions of uncertainty’ (Efklides, Citation2006, p. 5). The feelings respond to the gestalt of presenting circumstances, including the task difficulty, the context including whether it is perceived as positive or negative, one’s self-concept and affective factors such as mood. Efklides concludes that metacognitive experience monitors ‘…the progress being made towards ones goal and they convey this information in an affective or cognitive manner… guiding the self-regulatory process in both the short and long run’ (Efklides, Citation2006, p. 7). A great deal of the assessment of the contextual support for learning implied in the model in may therefore be by way of affective pre-appraisal and the attendant meta-cognitive judgements. Importantly these may influence (i) the learner’s willingness to enter into and engage with the context at all, (ii) the choices they make about how to engage and finally (iii) if and how they join with others in the process. Work by Iiskala and Lehtinen (Citation2004), for instance, suggests that people co-regulate their learning on the meta-cognitive experience cues of those with whom they are collaborating.

This research then has re-identified empirical support for these well-established dispositions and capabilities associated with effective learning. All three sub-dimensions of mindful agency can be shown to connect the learners to their context, including their relational and social/emotional characteristics, and this serves to validate the interdependence found in the empirical evidence.

How then does this construct relate to the other active learning power dimensions? The factor analysis (both exploratory and confirmatory) suggested four additional learning power dimensions closely associated with mindful agency. This is consistent with the ELLI, but following the reanalysis and the re-specification of scales, these are renamed creativity; sense-making; hope and optimism; and curiosity.

Creativity

The exploratory factor analysis of the creativity items returned two factors: (i) imagination and intuition and (ii) risk-taking and playfulness. The final scale of creativity returned an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.80 with the eight items presented in .

TABLE 6: Creativity scale

These latent variables in the creativity scale are consistent with the literature on creativity. Hennessy and Amabile’s (2010) review concluded that in spite of the array of disciplinary approaches to understanding creativity, what is required now are all-encompassing systems theories of creativity designed to tie together and make sense of the diversity of perspectives, from the ‘innermost neurological level to the outermost cultural level’ (p. 590). Although creativity has some trait-like stable characteristics, it is also a state subject to influence by the social environment, and people are most creative when they are intrinsically motivated. Kim (Citation2006) suggests that reflective abstraction is the mechanism for creativity and also that creativity and imagination are interrelated. Vygotsky went further and argued that imagination serves as an imperative impetus of all human creative activity and that its operation is a ‘function essential to life’ (1930/2004, p. 13). He also suggested that, developmentally, imagination is a successor of children’s play (Vygotsky, Citation1930/2004, p. 77).

There is also substantial support in the literature for playfulness as a creative activity and process (Hennessey and Amabile, Citation1987; Saracho, Citation2002) which is a way of exploring ideas and testing alternative pathways for problem-solving (Tsai, Citation2012). It is also instrumental to seeing problems with a ‘different lens’, which is important in shifting paradigms and worldviews (Mumford, Citation1984). Tsai’s review argued that ‘educators should bring play and imagination into their classrooms in order to encourage creativity’ (2012, p. 15). What is also relevant is the importance of affect in creativity – Torrance (Citation1972) for example found that creativity is supported by both affective and cognitive factors, and Anderson identified that ‘play depends on two rudimentary ingredients: safety and stimulation’ (1994, p. 10). To be creative an individual has to engage with the unknown or the uncertain – this requires an environment that is ‘safe enough’ in which to do so.

Sense-Making

The exploratory factor analysis of the meaning making scale returned two factors: (i) making meaning and (ii) making connections. We renamed this scale sense-making. This scale returned an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.75 with the seven items presented in .

TABLE 7: Sense-making scale

Sense-making is a core part of learning, and these two latent variables are supported in the literature. Cross (Citation1999) argues that learning takes place through making connections in several ways: neurological, social, cognitive and experiential. People understand the world through schemata – ‘a cognitive structure that consists of facts, ideas and associations organised into a meaningful system of relationships’ (1999, p. 8). It is through constantly comparing existing schema with new information and understanding that we develop through our encounter with the world, that we adapt or stretch our existing understanding to accumulate richer and deeper knowledge. de Jaegher and di Paolo argue that our understanding of the world and relationships is not just through storing information as an ‘objective’ entity. We do not passively receive information from our environment – rather we translate information into internal representations whose value is significant. ‘They [human beings] actively participate in the generation of meaning in what matters to them: they enact a world’ (2007, p. 488). Sense-making is, for them, a relational and affect-laden process grounded in biological organisation. Interestingly this process of creating a perspective of value on the world has been more recently elaborated scientifically in terms of the theory of autopoiesis – the self-organising development of the individual in recursive relationship with its environment (Di Paolo, Citation2005; Thompson, Citation2007; Weber and Varela, Citation2002). The two latent variables in the sense-making scale reflect both the affective/narrative aspect of meaning making and the schematic, cognitive aspect of making connections.

Curiosity

The scales for curiosity and changing and learning did not reveal latent variables. The scales and these are presented here as optimism and hope in and curiosity in . The optimism and hope scale returned an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.73 with three items. The curiosity scale returned an alpha reliability coefficient of 0.69 with four items.

TABLE 8: Hope and optimism scale

TABLE 9: Curiosity scale

Curiosity is understood by Runco (Citation2007) as one of the qualities of a creative personality, and it has been consistently understood as a critical motivator of human behaviour at all stages of the life cycle. Loewenstein (Citation1994) positions curiosity as a cognitively induced deprivation which arises from the perception of a gap in information or understanding, or a motivation inherent in information processing (Hunt, Citation1963). This is significant for educators – curiosity is influenced by the state of one’s knowledge processing, but the motivation to understand may be a powerful means of generating those knowledge structures. This scale reflects both the motivation and the cognitive understanding aspects of curiosity.

Hope and Optimism

The hope and optimism scale is named more accurately to link with the extant literature. Snyder (Citation2000) defines hope as a motivational construct that initiates and sustains progress towards a goal. It is a control belief, the perception that one can strategise different routes required to progress towards a goal (Snyder et al., Citation1991, Citation2002). There is an agency component to hope – the perception that one has the ability and the energy successfully to navigate a chosen pathway to achieving a goal. Hope is predictive of student achievement at all educational levels (Curry et al., Citation1999) and adults with hope have higher coping mechanisms and problem-solving capabilities. It predicts better study skills (Onwuegbuzie and Snyder, Citation2000).

Hope is closely related to optimism – a control belief involving positive thinking and a positive attitude to life events (Scheier and Carver, Citation1985; Seligman, Citation1991) and also to self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1986) – a competence belief about one’s capability to execute a particular action and achieve a particular goal. Robinson and Snipes (Citation2009) propose that hope, optimism and self-efficacy are expectancy beliefs that form a set, with each focusing on different aspects of competence and control. Together their study demonstrated that these three variables form a motivational system of competence and control related to academic well-being. This scale is most closely described as hope, with optimism. It does relate however to self-efficacy and agency, and this will be discussed later (Zimmerman and Schunk, Citation2006).

10. Mindful Agency as an Explanatory Variable

We hypothesised that the mindful agency construct stood in a meta-relationship to the remaining five active learning power dimensions. Our second analysis was therefore an exploration of the relationship of mindful agency to hope and optimism, sense-making, curiosity and creativity. Our hypothesis was that this mindful agency is developed through language and relationship in the process of learning and that it is generated explicitly through becoming aware of one’s creativity, curiosity, sense-making and hopefulness – providing the executive functioning to know when to use these to solve problems through learning. The model in presents the details of each of the four active dimensions of learning power (curiosity, sense-making, creativity and hope and optimism) in relation to mindful agency. The model is in good fit according to RMSEA = 0.036 and shows that 90% of the variance in sense-making, 85% in creativity, 72% in curiosity and 59% in optimism and hope are accounted for by mindful agency. This confirms our hypothesis that mindful agency is strongly associated with the other four active learning power dimensions and reflects the development of the other four, hence is considered to be a second-order dimension. This model also supports the internal structure of creativity and sense-making that were identified from the exploratory factor analyses described earlier.

11. Learning Relationships

The exploratory factor analysis of the learning relationships scale in the ELLI returned three factors: (i) dependence on others, (ii) collaboration and (iii) belonging to a learning community. This suggested that the original ‘learning relationships’ scale was conceptually unclear. Learning, as we articulated in our theoretical starting point, is a relational process that requires interdependence (John-Steiner, Citation2000). This enabled us further to tease out the different nature of the three components identified through our analysis. Collaboration is a person’s inclination towards learning with, and from, other people; whilst the sense of belonging reflects a person’s perception of other people’s support and engagement in relation to his or her learning and is emergent from interpersonal interactions (Mcginn, Citation2012; Mcginn et al., Citation2005). The sense of belonging also reflects relational trust through which learners are confident that when they turn to significant others for help in learning they will be supported (Bryk and Schneider, Citation2002). Self-determination theory identifies ‘the need for relatedness which concerns the experience of love and care by significant others’ as a basic human need that requires conditions of nurturance based on psychological need satisfaction (Vansteenkiste and Ryan, Citation2013, p. 264).

Therefore these two scales, ‘collaborating with others’ and ‘belonging to a learning community’, are considered to be conceptually different, while both describe positive approaches to learning relationships and are likely to be developed in mutuality. In contrast to interdependence, being inclined to be dependent on others says more about the relational dynamics between self, other and the environment than about a straightforward, desirable learning disposition. It is more of visceral ‘state’ than an agentic disposition or tendency to behave in a certain way. We found it conceptually clearer to group these dependency items with fragility and dependence items, because they all address a relational state of dependency on others, or structures, in a particular learning environment. We will further elaborate on this in the next section. The scale of collaboration and the scale of belonging returned an alpha coefficient of 0.71 and 0.76, respectively, with three items each ( and ).

TABLE 10: Collaboration scale

TABLE 11: Belonging scale

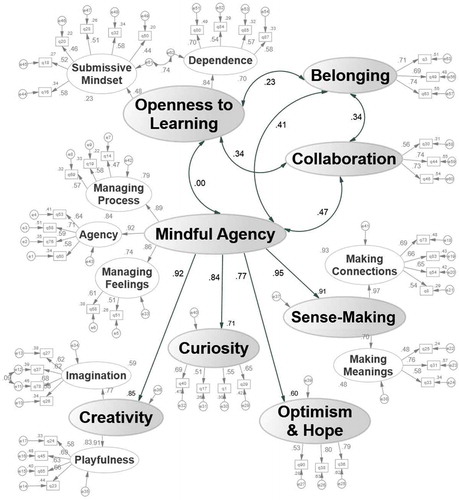

12. Fragility and Dependence

This scale was the subject of extensive analysis and reporting in a separate paper (Deakin Crick et al., Citation2015, in preparation). In summary, the study demonstrated that the ‘fragility and dependence’ scale operates independently from the remaining six scales, and there is no clear pattern, except with those individuals who score lowest on all learning power scales. These cases are associated with low levels of dependence and fragility. Our conclusions were that low scores on dependence and fragility cannot be construed as resilience (as was assumed in practice in applications of the ELLI). Rather, a low score on dependence and fragility is better understood as an emotional and cognitive ‘closedness’ to the inter- and intra-personal dynamics of learning power as a defence against external ‘threats’, and this indicates a barrier to deep learning. A high score, indicating dependence and fragility, is also not desirable in terms of learning power, since it leads to loss of subjectivity (Morin, Citation2008) and therefore agency, due to the failure of a healthy and productive operational closure (Goldspink and Kay, Citation2009). The study suggested that this quality of being either ‘closed’ or ‘dependent’ in learning is context-dependent and can only be appropriately interpreted in the light of the relational context of the learner (i.e. it may be adaptive or maladaptive from the perspective of the learner, depending on the context). For the current study we conducted an exploratory factor analysis on all of the items measuring dependence and fragility identified two latent variables: (i) a ‘submissive mindset’ and (ii) ‘dependence on others’. Both of these are indicators of the degree of learners’ openness or closedness to the learning environment, so the scale was renamed openness to learning, and it returned an alpha coefficient of 0.78 with 10 items ().

TABLE 12: Openness to learning scale

This model suggests that this scale should be treated differently from the other scales since either extreme is undesirable for learning. To be (i) closed or to be (ii) dependent on the other suggests that (i) the other is not available for relationship in learning or (ii) the self is not available for relationship in learning. Both reactions in effect close the flow between the learner-self and the others, though in very different ways.

What this scale measures is an emergent state of the self-ego relational processes. A desirable measure would be a midpoint, for optimal learning, although in some contexts of risk a measure nearer to either extreme may be found more appropriate. There are few research papers that address this issue in educational psychology (Bossche et al., Citation2006). It has, however, been well investigated within the team learning and administrative science literature under the terms ‘trust’ and ‘psychological safety’. Levin and Cross define trust as the quality of ‘the trusted party that makes the trustor willing to be vulnerable’ (2004, p. 1478). They point out that ‘trusting relationships lead to greater knowledge exchange: When trust exists, people are more willing to give useful knowledge’ as well as ‘more willing to listen to and absorb others’ knowledge’ (ibid.). This knowledge exchange is essential to learning both because the learner needs to absorb knowledge from other people and because he or she is more likely to receive effective help when he or she shares useful knowledge from or about him or herself. Similarly, psychological safety, defined as ‘a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking’, facilitates ‘learning behavior in work teams because it alleviates excessive concern about others’ reactions to actions that have the potential for embarrassment or threat, which learning behaviors often have’ (Edmondson, Citation1999, p. 354). Edmondson (Citation1999) also points out that ‘engaging in learning behavior in a team is highly dependent on team psychological safety by suggesting that team members’ confidence that they will not be punished for a well-intentioned interpersonal risk enables learning behavior in a way that team efficacy, or confidence that the team is capable of doing its work, does not’ (p. 376). This is in line with our hypothesis that openness to learning is distinct in nature from the capability of learning powered by mindful agency and other active learning dispositions.

13. The Internal Structure of Learning Power

Through the exploration we describe earlier, we renewed our view of the internal structure of learning power. Meaningful learning involves deep changes in learners’ behaviour, beliefs and attitudes. While these changes are energised by a personally chosen and meaningful purpose, it is the active learning power dimensions of sense-making, creativity, curiosity and hope that regulate the flow of energy in the learning process, enabling it to empower the journey from purpose to achieve a particular performance outcome. This regulatory process is achieved through mindful agency, constituted by agency, managing processes and managing feelings. We hypothesise that this regulatory process is only engaged when there is a context that is judged as presenting a level of risk consistent with supporting openness to learning. This assessment of risk is most likely unconscious, involving processes of emotional pre-appraisal. Collaboration and belonging have been shown to improve the effectiveness of learning where the problem to be solved imposes a high cognitive demand (Kirschner et al., Citation2011). At the same time, participation in peer learning has been shown to influence individuals’ choice of learning strategies (Iiskala and Lehtinen, Citation2004). Collaboration is therefore a process choice (metacognitive strategy), but once that choice has been taken, mindful agency becomes somewhat shared.

In order to test this hypothesis, we built a model of the internal structure of learning power, using those items belonging to the latent variables we have described. At first, although the model was in good fit (RMSEA = 0.35), the solution of the parameter estimates indicated a negative covariance estimate between mindful agency and openness to learning. As a result this covariance parameter was constrained to be 0, according to the suggestion of Bentler and Chou (Citation1987). This resulted in the same fit statistic as the first solution. The estimates are presented in . The model confirms that (i) openness to learning is orthogonal to the active learning power dimensions, of which mindful agency is the key and (ii) collaboration and belonging, the two scale previously treated as a single dimension of learning relationships, can be measured as separate scales. The relationships between collaboration, mindful agency, belonging and openness to learning are modelled by allowing each to co-vary. This is reflecting the fact that we do not as yet have a clear view about the nature of the relationships between these variables beyond that they are loosely related. It is an area for further exploration during the 3-year research phase.

14. Summary of Findings

The initial testing of our practical and experiential theory about learning power through structural equation modelling confirmed our hypothesis that there were three orthogonal dimensions or dimension sets within the overall construct of learning power: (i) learning relationships, (ii) fragility and dependence and (iii) the set of ‘active’ learning power dimensions: strategic awareness, creativity, critical curiosity, meaning making and changing and learning. Learning relationships was the most complex, whilst fragility and dependence, although mildly negatively correlated with all of the active learning power dimensions, were not their direct opposite, and this was discussed in detail in our previous paper (Deakin Crick et al., under review). Our hypothesis was that the fragility and dependence scale was picking up a visceral, emotionally based disposition about a person’s state of openness or closedness to the unknown, to risk taking, ambiguity and uncertainty, in contrast to the more volitional and cognitive constitution of the remaining five active dimensions, of which strategic awareness was the most significant.

We then explored the internal structure of each of these three orthogonal dimensions, beginning with the set of active learning power scales. We did this by using an exploratory factor analysis on each scale with a randomised half of the data set and followed it with a confirmatory factor analysis, through building a structural equation model with the other half. This demonstrated that the scale of strategic awareness comprised of three latent variables, one of which was to do with the management of feelings, the second was to do with managing of the processes of learning and the third was about a sense of agency in learning. We demonstrated two latent variables in creativity (‘imagination and intuition’ and ‘risk taking and playfulness’) and two in meaning making (‘making connections’ and learning ‘mattering emotionally to the learner’). We theorised that strategic awareness was a ‘second-order’ type of dimension developed through language, dialogue and relationship, and so we chose to develop a structural equation model to explore the relationship between strategic awareness and the remaining ‘active’ learning power dimensions. Learning relationships were constituted by three latent variables (‘dependency’, ‘collaboration’ and ‘belonging’) which were evidently contextually sensitive. Of these three, the ‘dependency’ variable correlated with fragility and dependence. The fragility and dependence scale contained two latent variables (i) ‘submissive mindset’ and (ii) ‘dependence’.

Finally, we reconstructed a structural equation model of the whole set of scales to test our emerging hypothesis about the internal structure of learning power and to present a completely new instrument which is more parsimonious (72 items in the original version reduced to 49 in the revised) but balances the competing requirements of practical utility with statistical rigour. Despite being more parsimonious, the new model is more fully articulated and nuanced and provides much greater clarity about the nature of the relationships between the dimensions of learning power.

15. Discussion of Findings

This reexamination of data collected since 2002 has enabled a more nuanced and rigorous conceptualisation of the concept of learning power and its role in the process of enquiry than was originally developed. In this section we will first discuss the findings from a statistical perspective, together with the benefits, limitations and affordances of the model. We then explore the conceptual and theoretical implications of the findings, leading to a refined working redefinition of the concept of learning power as it fuels a learning journey towards resilient agency.

First, the overall model produced demonstrates a good fit with strong effect sizes, which provides a solid foundation for conceptual and theoretical development. Each of the scales has been improved by a reduction in the number of items whilst maintaining internal consistency. The whole questionnaire is now 49 items, considerably less than the previous 72. Of these 49 items only 32 were drawn from the original instrument – the others were devised during the ongoing effort of research and development between 2003 and 2013. The experience of the team in working with the scales in both theory and practice facilitated the iteration between the theorisation and testing necessary for exploration using structural equation modelling. The reliability of the model was tested systematically through the randomised splitting of the data set.

In practical terms this has enabled much greater discrimination about the nature and dynamics of the different elements of the model, and this should facilitate more effective practical scaffolding of resilient agency in learning, by teachers and facilitators. Because the instrument was conceived as an assessment tool to stimulate self-directed change, it is important that it reflects the complexity of human learning rather than aiming, through a reductionist, psychometric imperative, to measure one single variable, which would inevitably reduce its utility in practice. This has led to criticism on the one hand, because of the covariance between the scales which is undesirable from a purely psychometric perspective, but has afforded some face validity and pedagogical value on the other.

It is the interrelationships between the components of learning power which have become clearer through this study. First, the scale of mindful agency has proven to be a crucial dimension in the development of learning power. This is because mindful agency is constituted in the self-awareness and confidence to engage and progress in learning to achieve a chosen purpose, the confidence to recognise and recover from negative feelings associated with learning and to plan and manage the self in the processes associated with learning tasks. Mindful agency predicts sense-making, creativity, curiosity and hope, suggesting that mindful agency is the ‘motor’ of learning power, which is developed through meta-reflection on learning in practice. Awareness and reflection develop through language – even though we often know more than we can say. Mindful agency also reflects a person’s relationship with themselves.

Sense-making is about making connections between otherwise separate information or data and about learning that is meaningful to the learner. Curiosity is the orientation to want to understand, to get beneath the surface and to ‘dig deeper’, and creativity is constituted by imagination on the one hand and risk taking and playfulness on the other, such that new value is created. Hope and optimism is about the self-knowledge a person has about being able to grow and change over time – a growth-orientation towards life and learning.

This model suggests that to develop mindful agency the learner should expose themselves to varying situations which demand different levels of creativity, curiosity and a sense-making, while being supported to reflect on progress towards what has been achieved. Through this they will have the opportunity to develop the cognitive and emotional awareness necessary to guide their agentic choices about how to learn and in so doing develop the optimism and hope to continue. They will develop resilient agency – the capacity to respond profitably to risk, uncertainty and challenge over time.

The model provides a language with which to engage and reflect – and in turn this provides a framework for coaching conversations which focus on empowering learners to ‘do it for themselves’. So mindful agency is grounded and given specific meaning through the remaining four active learning dimensions. Mindful agency can also be used to leverage change: as one consciously develops, say, one’s ability to ask questions and one’s curiosity, through the process of ‘consciousness raising’, one is also developing mindful agency.

The scales that measure learning relationships have now gained greater clarity through this exploration. Collaborating and belonging to a community or group supportive of one’s learning are two distinct but related social aspects of learning. The scale ‘openness to learning’ is a new and improved interpretation of the former ‘fragility and dependence’ scale which has been dealt with extensively in a separate paper, which we theorise is an emotional and cognitive state of ‘openness’ to the inter- and intra-personal dynamics of learning power, which precedes the engagement and utilisation of mindful agency. These three scales are highly context responsive. In other words, they depend to a large extent on the relational context and levels of relational trust of the learner in that context, based on their discernment of the intentions of others in relation to them (Bryk and Schneider, Citation2002). This also demonstrates how the scales are neither of a similar status nor having simple relationships with each other.

Learning as a Complex Process

What has emerged from this model is a greater understanding of the complex nature of learning power – in terms of several relationships: that of the learning agent with the self; the interrelationships between the dimensions of learning power (‘intra-personal’); the relationships between learners (‘inter-personal’); and the relationship between learners and their contexts (‘inter-contextual’). It has enabled the development of an agency-based concept of learning in a complex social ecology, where learning resilience is developed and achieved through mindful agency. In other words, understanding learning as a complex process in which the ‘mindful agent’ is the driver of a journey of change provides a way of conceptualising both the ‘lateral’ and ‘temporal’ connectivities of learning and the development of an integral model of learning power.

Research in the field of interpersonal neurobiology explores the connections between the brain, the mind and interpersonal relationships, and it does this with the explicit purpose of developing new approaches to understanding and promoting human well-being. Siegel argues that ‘a core aspect of the human mind is an embodied and relational process that regulates the flow of energy and information within the brain and between brains’ and that ‘the mind is an emergent property of the body and relationships… created within internal neurophysiological processes and relational experiences’ (2012, p. 3).

Energy and information flow is what is shared between people within cultures, and this is also the ‘subject matter’ of learning. How a person-in-relation regulates that flow – how they select what matters, make sense out of it and apply it to their purpose – is a process of learning in any domain. This improved model of the internal structure of learning power provides a language for – and hence way of conceptualising – how we can mindfully regulate that flow of energy and information.

Theories of agency share the view that organismic aspirations drive human behaviours and that humans are the authors and active agents of their own development (Little et al., Citation2006). The concept of human agency provides an organising framework for different constructs – such as self-efficacy, grit, growth orientation, etc. – and it is a key concept for understanding learning as a complex process – a multilayered model of the self that moves from a particular (volitional) purpose to the realisation of that purpose as performance.

Perhaps the most pertinent discussion of these findings is drawn from the field of self-determination theory. In a review of the field, Vansteenkiste and Ryan (Citation2013) identify its fundamental organismic-dialectical meta-theory, which offers an understanding of the human being as an active integrator of meaning, developing an ever more elaborated and unified sense of self, which is in dialectical tension with the social contexts which either nurture or inhibit this active, integrating process. From this perspective ‘human development and well being must be viewed as a dynamic potential that requires proximal and distal conditions of nurturance’ (Ryan and Deci, Citation2002, p. 3). These conditions of nurturance are based on psychological need satisfaction – the need for competence or a sense of effectiveness in interacting with ones environment, the need for relatedness which concerns the experience of love and care by significant others and the need for autonomy or the experience of volition and self-endorsement of one’s activity (Vansteenkiste and Ryan, Citation2013, p. 264).

They review the evidence for ways in which need frustration and need thwarting lead to passivity, fragmentation and ‘ill being’, whereas the experience of these needs being met appropriately is a harbinger of proactivity, integration and well-being satisfied (Ryan et al., Citation2008). What is relevant to this discussion is what these researchers describe as resilience factors which can protect against negative consequences and encourage the emergence of positive ones. Two key resilience factors are (i) the capacity autonomously to regulate behaviour, even under threat or pressure and (ii) awareness or mindfulness that supports the autonomous regulation of behaviour. Part of that regulation is ‘knowing’ even when to engage.

This modelling of the internal structure of learning power supports the core tenets of self-determination theory with its basic assumption that people are proactive organisms, inclined to shape and optimise their own life conditions towards increasing levels of self-organisation. This energy, or life force, is a ‘given’ of human nature: under optimal conditions human beings will learn, grow and change towards a coherent sense of self-in-relation to others and to the environment. Whereas under suboptimal or pathological conditions of need frustration or thwarting, people develop ‘ill-being’, need substitutions and compensatory behaviours, which include releasing self-control and ‘rigid’ behavioural patterns, which function as a defensive script, which works against integration, coherence and autonomy. The concept of mindful agency modelled here extends the tenets of self-determination theory by giving focus to the ways in which the individual can articulate and reflect on their sense of identity and move forwards in the realisation of their chosen purpose. Together with the ‘relationship’ dimensions and the ‘openness to learning’ dimension, this also provides a language for scaffolding learning, particularly in the context of open ended enquiry.