ABSTRACT

School leaders are expected to act with integrity, but values are always contested: one person’s ‘moral purpose’ is not the same as another’s. Researchers have explored these issues from different angles. One approach focusses on individual leaders, seeking to understand how their values inform their practice. Other work highlights that individual values are only part of the story: values are embedded within professional norms and organisational cultures, while policy and governance frameworks serve to structure and constrain individual agency, particularly in marketised and performative systems. This paper draws on examples from recent research in England to argue that leadership responses to structural constraints should be seen on a spectrum in terms of how far they reflect individual agency and values, proposing four possible categories – ‘toxic leadership’, ‘pragmatic compliance’, ‘principled infidelity’ and ‘authentic agency’. It also discusses the question of how values operate at locality and national levels as well as within individual schools and draws the analysis together into a conceptual frame.

1. Introduction

School leaders are expected to act ethically – to demonstrate ‘good’ values and behaviours. In the UK the Nolan principles (Citation1995) set out a series of ‘principles of public life’ which should underpin all public service, including in education: selflessness, integrity, objectivity, accountability, openness and honesty. The last of the Nolan principles is ‘leadership’, stating that ‘holders of public office should exhibit these principles in their own behaviour … (and) should actively promote and robustly support the principles and challenge poor behaviour wherever it occurs’. Headteacher Standards in each UK nation reinforce these expectations (e.g., DfE, Citation2020; GTC Scotland, Citation2021).

Educational researchers generally see leaders’ values as important, but there are differing perspectives on how far individual values influence organisational decision-making, practice and outcomes (Askeland et al., Citation2020). One approach has been to focus on individual leaders, seeking to understand how their values shape their practice in the context of externally driven change (Day and Gu, Citation2018). Other work highlights that individual values are only part of the story: values are embedded within professional norms and organisational cultures, while policy and governance frameworks commonly serve to structure and constrain individual agency (Ball, Citation2003).

What seems clear is that values are always contested: one leader’s ‘moral purpose’ is rarely the same as another’s. This becomes most apparent when espoused values are put into practice: when decisions have to be made about tricky issues, such as the enactment of national policies, how to promote the school at a time of falling demographics, or whether or not to accept a student whose needs or behaviours will present undoubted challenges. Recent developments in England have raised serious questions about leadership values and the implications if they are not collectively shared and enacted. For example, a minority of schools have been shown to push out (‘off-roll’) students who are challenging to teach (Ofsted, Citation2022) – a practice that clearly contravenes the Nolan principles. Partly in response, the Association of School and College Leaders has sought to develop a consensus by convening an independent commission, leading to the publication of a Framework for Ethical Leadership in Education (Ethical Leadership Commission, Citation2019), but it unclear how much has changed.

This article discusses these issues, drawing on examples from my own research in England. It does not follow a ‘traditional’ format – for example, it does not include a section on methodology and ethicsFootnote1 - as it is intended as a synoptic review and discussion rather than a report on findings. The two studies I draw on here were not focussed exclusively on leadership values and policy enactment, although both reports reflect on these issues (Greany and Higham, Citation2018; Greany et al., Citation2024). My positionality here is important, since my own experience and values will shape how I see the role of values in educational leadership. I have spent nearly 20 years working in policy and research roles related to school leadership in England, including at the National College for School Leadership (2006–13) and in academia. My theoretical and epistemological stance is broadly pragmatic – in a Deweyan sense – and constructivist, drawing on a mix of thinking tools from governance, complexity, socio-spatial and organisational traditions to explore educational leadership.

By focussing on espoused values and enacted virtues – or actions in context – this article adopts a Virtue Ethics approach (Higham, Citation2021). However, in doing so, it does not assume that leaders’ values are inherently desirable, unlike the largely normative focus of work on ethical, servant and authentic leadership (Ahmed, Citation2023; Chang et al., Citation2021; Demont‑Biaggi, Citation2020). The article is thus less focussed on ethical leadership per se and more interested in using a values lens to explore questions of structure, agency, and policy enactment.

The article argues that, at the level of the individual school, leaders’ values can ‘matter’, in the sense that they can help inform decision-making and influence wider colleagues and cultures. The problem is that not all leaders do act ethically. Such unethical behaviour might be attributed to individual characteristics and personality disorders, such as narcissism and psychopathy (Samier and Milley, Citation2018). However, many observers also recognise that systemic pressures have increased in recent decades, which can incentivise performative leadership and/or make ethical choices more complex (Newman and Clark, Citation2009). These commentators argue that school leaders have been collectively re-positioned over recent decades – via a range of New Public Management (NPM)-inspired reforms (Hood, Citation1991) – as principal drivers of school improvement and change, with one outcome being that leaders feel compelled to prioritise organisational performance ahead of other considerations. Importantly, these NPM-inspired policy and accountability incentives and requirements reflect their own policy values and are not always aligned or coherent, while governance failures remain common (Stewart, Citation2009; Thomson, Citation2020). While policy and governance frameworks can undoubtedly be improved, it seems likely that ethical dilemmas will remain a feature of public education systems that seek to serve increasingly diverse and complex communities and needs, with limited resources and even less agreement on what education is ‘for’ (Burns and Köster, Citation2016). For these reasons, the article explores not only whether leaders’ values ‘matter’ within individual schools, but also how values play out across local and national levels.

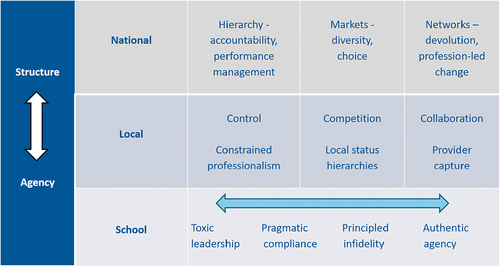

The article is structured as follows. The following section frames the issues and provides some key definitions. Following this I draw out some key themes from the literature in terms of how leadership values have been conceptualised. I then introduce and briefly discuss four vignettes, one of a single school which arguably represents authentic, values-based leadership, and three from schools in a single locality which reflect divergent approaches and values. The Discussion section which follows seeks to draw out some implications, arguing that leadership responses to structural constraints should be seen on a spectrum in terms of how far they reflect individual agency and values, proposing four possible categories – ‘toxic leadership’, ‘pragmatic compliance’, ‘principled infidelity’ and ‘authentic agency’. It also discusses the question of how values operate at locality and national levels as well as within individual schools and draws the analysis together into a conceptual frame. Finally, the Conclusion reflects on the article’s contribution and limitations.

2. Values, Decision-making and Leadership: Some Preliminary Thoughts

This article focuses on values, including whether and how espoused values are enacted (or not). Values are generally defined as ideals or goals which can be held individually and collectively. In modern parlance, values are commonly twinned with virtues, referring to lived values that have become habits of character through practice and experience, and to ethics, which Begley defines as ‘normative social ideals or codes of conduct usually grounded in the cultural experience of particular societies’ (Citation2012: 41). Many definitions position values as inherently desirable – or ‘good’: for example, ‘Values are individual and collective trans-situational conceptions of desirable behaviours, objectives and ideals that serve to guide or valuate practice’ (Askeland et al., Citation2020, p. 3). However, a growing number of studies highlight examples of toxic leadership, corruption and maladministration, often as a result of individual or organisational values that can be seen as problematic (Craig, Citation2021; Thomson, Citation2020; Samier and Milley, Citation2018). Whilst some might argue that such ‘moral failures’ are the opposite of ‘moral purpose’ and that values are always positive and desirable, I prefer to see all values as socially constructed and thus open to interpretation. Some might see this as dangerous relativism, but my position is to maintain criticality even whilst assuming that individual leaders are seeking to adhere to values that they believe are morally defensible. This view chimes with Espedal et al. (Citation2022, p. 1) who acknowledge that ‘although values are desirable, they can also be multiple, diverse, abstract, tacit, hidden, temporary and conflict’. The focus thus becomes whether and how leaders are able to embody their values as they work to enact policy requirements and respond to structural constraints.

One departure point for this article was a series of discussions I have had over several years with groups of serving leaders – mostly in England, but also from New Zealand, Singapore and Norway – in response to the question below:

How should school leaders make decisions about what is the ‘right’ thing to do in any given circumstance?

in response to policy, accountability and funding pressures/incentives?

in response to parent/pupil voice?

based on professional experience and knowledge of the school’s context?

in response to the evidence base?

based on an assessment of what the staff will support or cope with?

based on what’s best for all schools/children in the locality?

based on a set of underpinning values?

By putting ‘right’ in inverted commas, I signal that I am not assuming there is necessarily a single correct answer or response in these situations. The question is thus designed to encourage reflection on the many situations in which school leaders face some degree of ambiguity in their decision-making, where values become particularly salient.Footnote2 For example, to say ‘I can’t introduce that initiative right now because I don’t think the staff could cope with it’ reflects a values-based choice (to prioritise staff well-being or, perhaps, to avoid conflict with the unions) even if this is not explicitly acknowledged.

The various groups of leaders I have discussed this question with tend to give a broadly consistent response, along the lines of: all these drivers are important, with different weights for each depending on the situation and often in complex combinations, but at the end of the day we have to respond to policy, accountability and funding pressures and incentives, so we try to do this whilst staying true to our underpinning values.

This raises a question around whether the ‘policy, accountability and funding pressures and incentives’ in any given system can be aligned – with each other and/or with a coherent set of values? Stewart (Citation2009) explores policy values, showing how even a single policy might encompass multiple overlapping, or even competing, values. These different values can become layered over time, as different interest groups and priorities interact. For example, a policy on school autonomy (aka school-based management) might be justified in terms of: i) strengthening school accountability (i.e., managerialism); ii) increasing parental choice and efficiency (i.e., markets); and/or iii) enhancing community ownership and responsiveness through local school governance (i.e., devolution and social democratic aspirations). In a similar vein, Newman and Clarke (Citation2009) explore the ways in which public values are continually interpreted and translated within contemporary governance ‘assemblages (which) bring together people … policies, discourses, texts, technologies and techniques, sites or locations, forms of power or authority, as if they form an integrated and coherent whole that will deliver the imagined or desired outcomes’ (p.24). One result of this cobbling together, they argue (Citation2009, p. 127), is that front-line leaders are left to try to resolve complex, even intractable, issues:

responsibility for managing tensions and dilemmas becomes devolved to individual agents … [and] tend to be experienced as personal, professional or ethical dilemmas.

These points all serve to indicate the core preoccupations and assumptions underlying this article. It recognises that leaders might not always act ethically or, at least, in line with their espoused values, but it also acknowledges that in many cases these problematic practices will reflect the tensions and dilemmas inherent in contemporary policy and the sheer complexity of educational leadership as much as any shortfall in individual ethics.

3. Values, Structure and Agency: Themes from the Literature

Values appear throughout the educational leadership literature. A Google search on ‘school leadership + values’ reveals almost 550 m hits and the clever AI even summarises 19 main themes that can be drawn from this vast repository, including ‘Vision’, ‘Integrity’, ‘Courage’, Passion’, ‘Respect’, ‘Empowers others’ and so on. Given the scale of this evidence base, I do not pretend to provide a comprehensive review of how values inform leadership here. Rather, I highlight some of the main ways in which values and ethics have been investigated as a backdrop for the discussion that follows.

In their widely cited review of school leadership models, Bush and Glover (Citation2014) show how values are inextricably linked with any discussion of leadership, in particular if we accept a definition of leadership as a process of influence. Transformational leadership – ‘the process by which leaders influence staff and stakeholders to become committed to school goals’ (Bush, Citation2017, p. 563) – clearly positions values as a central component of shared vision, but Bush and Glover (Citation2014, p. 558) highlight the debate that flows from this:

The transformational model stresses the importance of values but … the debate about its validity relates to the central question of ‘whose values?’ Critics of this approach argue that the decisive values are often those of government or of the school principal, who may be acting on behalf of government. Educational values, as held and practised by teachers, are likely to be subjugated to externally imposed values.

Bush and Glover (Citation2014) go on to discuss moral and authentic leadership, positioning these as attempts to address the risk that transformational leaders might be charismatic but immoral. Moral and authentic leadership models thus ‘assume that leaders act with integrity, drawing on firmly held personal and professional values … (which) underpin decision-making’ (Bush and Glover, Citation2014, p. 559). Working beyond education, Chang et al. (Citation2021) assess authentic, servant and ethical leadership showing that despite each concept having multiple definitions, there is nonetheless a significant degree of overlap in how they are conceptualised. Ahmed’s (Citation2023) systematic review of research on ethical leadership in education indicates that the volume of research in this area is increasing, while ‘a positive relationship was found between ethical leadership and a wide variety of work-related outcomes including follower motivation, prosocial behaviour, teacher obligation, teacher empowerment, decision-making, and work engagement’ (Ahmed, Citation2023, p. 15). Demont‑Biaggi (Citation2020) discusses authentic leadership from a philosophical perspective: while she does conclude that a moral conscience founded on empathy and perspective-taking can be seen as ‘crucial for survival’ (p18) in evolutionary terms, and that this conclusion can provide a bridge to show ‘how authenticity and ethical leadership are related’ (p. 27), she acknowledges that her analysis remains too individualistic, with insufficient attention to how ethics affect followers and organisations. Chang et al. (Citation2021) go some way towards addressing this gap, by exploring whether and how senior leaders’ ethical behaviours might be seen to ‘trickle down’ through organisational structures and roles, thereby impacting on front-line employees.

While research into moral, authentic, servant and ethical leadership provides a core repository of work on values, it is important to recognise how often values appear in wider research on leadership and schools. These studies highlight how leadership values influence wider areas, such as decision-making (Leithwood and Steinbach, Citation1992), school cultures (Coates, Citation2021), and levels of trust (Tschannen-Moran, Citation2004). Susan Cousin’s (Citation2019) longitudinal study of school system leaders in England shows how values-based discourses can shift over time: in the years before 2010 her interviewees commonly use the language of ‘moral purpose’, but this largely disappears in the later years of her research. Finally, practitioner literature (i.e., books and articles written by serving and former school leaders) commonly stresses the importance of clearly articulated values within a school as a means of generating shared commitment and action. For example, Snape (Citation2021, p. 76), a primary headteacher, argues that leaders should not ‘feel obliged to have to justify [their values] to anyone’ and that ‘everyone’ in the school must share the same values ‘because they show people how to behave’.

Stepping back, it is possible to see two broad lines of research around leadership values in education – one of which places greater emphasis on individual agency, the other which sees structures (i.e., policies, regulations, accountability requirements, hierarchies/bureaucracies, institutional norms etc.) as largely subsuming agency.Footnote3

Starting with proponents of individual agency, Day and Gu (Citation2018, p. 343) found that individual leader’s values were important in how they interpreted and enacted new policies, although the performance level of the school was an important mediator of this agency, and that leaders’ values were often shaped by their personal backgrounds and biographies:

In successful schools, school principals are not only driven by a strong and enduring set of moral purposes, but … these can be directly located in their personal and professional biographies, and … remain constant … principals whose values are not aligned with policy are likely to face greater challenges in achieving success as defined by government than those whose values correspond more closely, and, in the longer term, their school may be judged to be less than outstanding.

In contrast, other researchers argue that structure subsumes agency. For example, some argue that neo-liberal reforms have created panoptic accountability structures which require teachers and leaders to not only behave in line with externally imposed norms and requirements, but to internalise these, so that they reorient individuals’ own values (Perryman, Citation2009). Ball (Citation2003) introduces the concept of performativity, which he describes as a regime of rituals such as inspection, audits, interviews, and routines, arguing that where leaders and schools engage uncritically in these rituals it can lead to perverse outcomes, such as teaching to the test or ‘performing’ for inspectors. Critically, he argues (Citation2003, pp. 217–226) that in such circumstances, structure subsumes agency and individual values become redundant:

Value replaces values … The policy technologies of market, management and performativity leave no space for an autonomous or collective ethical self.

So we see two contrasting perspectives on educational leadership values in contemporary school systems. The first argues that individual values and agency remain significant mediators of decision-making and action. The second sees individual agency and values becoming irrelevant in marketised and performative systems. The following section draws on vignettes to explore these issues in detail.

4. Vignettes: Authentic Agency within One School, Competing Values Across a Locality

The first vignette (‘Values-alignment within a single school’) is drawn from a detailed case study undertaken in a secondary school – here given the pseudonym Shilton Valley.Footnote4 The school was sampled, based on nationally available data, for a study of relatively inclusive mainstream secondary schools (Greany et al., Citation2024).

As the vignette indicates, the school is particularly strong at developing relationships with every child (including through its small group pastoral coaching model) and to maintaining these relationships even when behaviour breaks down (including through its commitment to restorative practice and to making no permanent exclusions). The vignette also highlights how the long-standing Executive Principal and his team have embedded a core set of values into policies and practices across the school, with the quotes illustrating that this approach is recognised and seen as meaningful by the range of staff and students we interviewed. What the vignette does not show – but is detailed in the project report – is how the school’s staff work flexibly to achieve belonging and inclusion in practice, reflecting high levels of professional trust and collaborative problem solving within a clearly articulated values-based framework.

Vignettes 2–4 (‘Competing values across three “outstanding” schools in one locality’) are drawn from another study (Greany and Higham, Citation2018),Footnote5 which focussed on how schools in England responded to the government’s ‘self-improving, school-led system agenda’ in the years after 2010. The mixed methods study included four place-based case studies: in each locality we visited a sample of around 12 primary and secondary schools, interviewing a range of school staff. The three primary schools highlighted here (all given pseudonyms) were in the same local authority area.

The brief vignettes highlight the different approaches to collaboration and knowledge sharing adopted by each school – the first (Hill) sells its knowledge to generate income, the second (Valley) protects its knowledge, while the third (Field) seeks to share and grow knowledge on behalf of its own staff and the wider system. Our interviews did not ask specifically about leadership values, but these are arguably clear to discern from the language the interviewees used and the approaches they adopted. Without doubt, these headteachers would want to find positive ways to describe their values and work, even if others might see some of these practices as problematic. For example, the Head of Hill (Selling) might describe its support for the struggling primary school in its Multi-Academy Trust (MAT) in terms of moral purpose, while its income generating CPD programmes could be seen as a way of sharing knowledge with the wider system. However, our interviews with other local schools revealed less positive views, with one head commenting: ‘There’s a lot of Heads that don’t want to work with him (i.e., the Head of Hill School) … he isn’t always nice to play with.’ Similarly, while the Head of Valley (Protecting) might describe his focus on protecting knowledge in terms of efficiency and, perhaps, wanting to minimise staff workloads, he also told us that he was trying to form a MAT but could not find other schools that wanted to work with him.

5. Discussion

The ‘self-improving, school-led system’ research that vignettes 2–4 are from (Greany and Higham, Citation2018, Citation2021) drew on governance theory, arguing that the government’s reforms reflected an attempt to mix and re-balance three overlapping approaches to co-ordinating the school system – through hierarchy, markets and networks (Exworthy et al., Citation1999; Jessop, Citation2011). The government claimed that its reforms were ‘moving control to the frontline’, reducing hierarchical oversight and increasing school autonomy (mainly by removing the role of local authorities, through academisation) and encouraging schools to ‘self-improve’ through partnerships and networks. However, the research found that these and other reforms actually served to intensify hierarchical and market pressures.

The impact of these changes was that leaders felt increased pressure to compete to attract higher attaining students who would do well in exams and thereby ensure that the school was deemed successful. This played out in local status hierarchies, with popular schools over-subscribed while lower performing schools struggled to fill places. Our analysis of Ofsted outcomes for all schools nationally over a 10-year period showed how schools became increasingly stratified, with children on Free School Meals likely to attend lower graded schools.

School leaders felt a need to put the needs of their school and its performance ahead of the needs of some students, although – to be clear – many of the schools we visited were resisting these pressures. Nevertheless, we did see some who felt they could not resist, sometimes recognising that their practices did not align with their espoused values, as the following quote indicates:

We work very hard with the portrayal of the school, the image of the school, marketing, pulling parents in … it is a very, very competitive group [of schools] and it doesn’t sit easily with my values as a teacher, but everybody wants those bright, sharp, well-motivated, middle class children who are going to get the top grades, and they do. … It’s who has which children. Well it is isn’t it? [pause] I’m sorry to say that. It shouldn’t really be like that.

Headteacher, secondary academy converter, Ofsted Outstanding

Others acknowledged the moral dilemmas they faced, but chose to put children’s needs first, even while trying to minimise this impact on their school:

When Ofsted comes and I’ve just taken in five asylum seekers so that my results plummet. It’s a horrible way to be talking about children. They’re children! It’s the situation that we’re in. If I take five new children in the last week of year 4, they count on my data. If I take those children on the first week of year 5, they don’t.

Headteacher, maintained primary school, Ofsted Good

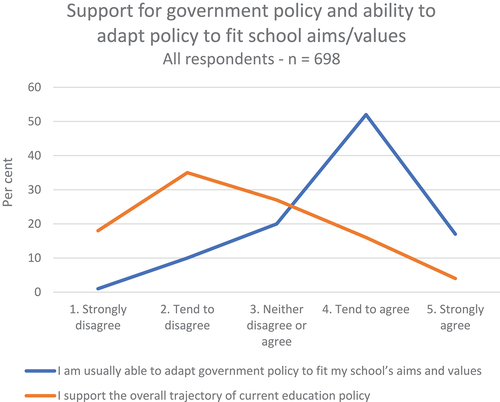

Interestingly, in the national survey of school leaders (n = 698) conducted as part of the research, we found that while just over half (53%) of all leaders said they do not support the overall trajectory of current education policy, most leaders (69%) agreed that they were usually able to adapt government policy to fit their school’s aims and values ().

Figure 1. School leaders views on policy and whether they can fit this to their school’s aims and values (source, Greany and Higham, Citation2018)

In the project report we concluded that the reforms tended to create both ‘winners and losers’, but argued that how this played out depended on complex factors that included: the history of local relationships between schools; the context of individual schools; and the differential agency of local actors, including their personal and professional values. Considering questions of policy enactment, we suggested that most school leaders were engaged in ‘pragmatic compliance’, which we defined as leaders seeking to hold true to their professional values and beliefs about education while mediating external change (Greany and Higham, Citation2018, pp. 98–99). We found that while some passive resistance to policy could be observed, this was only really possible if the school was performing well above minimum performance benchmarks and that it relied to some degree on solidarity between schools within a locality.

My conclusions here largely chime with our earlier assessment that – in England’s high accountability system – leaders must engage in some level of ‘pragmatic compliance’ with policy requirements. The common response to my question, outlined above, about how leaders decide what is the ‘right’ thing to do – i.e., they must respond to policy, accountability and funding pressures but try to do this while remaining true to their values – arguably fits this conclusion. However, I want to develop that core analysis in several ways. First, I argue that at the level of individual schools some school leaders go beyond ‘pragmatic compliance’ to demonstrate more values-based approaches, so I suggest we need to see leadership values and agency on a spectrum. Second, I begin to explore how values operate at the level of localities and nationally, arguing that these scales are hugely important but under-researched. Third, I offer a conceptual frame for how these ideas might interact.

Starting with individual schools, the Shilton Valley vignette illustrates how values that are consistently articulated and modelled by leaders can come to permeate culture and guide practice across a school, suggesting that school leaders’ values can ‘matter’.Footnote6 In Shilton Valley’s case the values have helped the school to resist isomorphic pressures and to forge its own inclusive approaches: for example, by deciding to stop all permanent exclusions and to close its isolation room, despite the fact that these are common practices nationally and are consistently promoted by the government’s ‘behaviour tsar’ (Bennett, Citation2018). How have values played this role at Shilton Valley? Begley (Citation2006, p. 575) outlines three ways in which leadership values can impact within a school: first, where values act as an influence on the cognitive processes of individuals and groups of individuals; second, values as a guide to action, particularly when facing ethical dilemmas; and third, as a strategic tool for building consensus among members of a group towards the achievement of shared organisational objectives. All three processes can be identified at Shilton Valley: for example in how values permeate the shared language adopted by staff, how values have helped guide decision-making in relation to dilemmas (such as whether or not to permanently exclude students), and how they have built consensus to achieve shared objectives (for example, by considering how the values inform the CPD strategy).

Shilton Valley thus goes beyond ‘pragmatic compliance’ with policy, representing a more active form of values-based agency in the face of structural constraints. The school has forged its own path, not only in relation to inclusion, but also in wider areas that run counter to current policy. For example, it launched a community garden and farm on a local site which has now become a community hub used by a range of organisations, including refugee groups, the police and the local authority. The school has also helped to forge a unique charitable trust which works with around 35 local organisations to address inequality and support progress for all learners across the city where it is based. All this is despite the fact that Shilton Valley is not a ‘high performing’ school (for example, it has never been judged ‘Outstanding’ by Ofsted), so does not fit neatly into the profile of schools that Day and Gu (Citation2018) suggest are more likely to be able to exercise agency. Neither is Shilton Valley in an area where there is clear solidarity between local schools – one of the conditions that Greany and Higham (Citation2018) identified as necessary for collective resistance to policy expectations. For example, senior leaders at Shilton Valley explained that some other local schools were not inclusive, preferring to encourage parents of children with special needs to attend Shilton Valley.

All this suggests that values-based authentic agency is possible – that ‘pragmatic compliance’ is not the only option. Clearly, Shilton Valley was selected for research precisely because it is an outlier, an unusually inclusive school, so I am not suggesting that all schools could articulate an equally compelling values-based journey and approach. Nevertheless, I suggest we should see leadership values on a spectrum, from ‘toxic’ at one end (i.e., directive, values-free leadership which focuses to an unhealthy degree on hitting performance targets, Craig, Citation2021), to ‘authentic agency’ at the other. In the middle I suggest two categories, first ‘pragmatic compliance’ (as defined above) and second ‘principled infidelity’, which Hoyle and Wallace define as ‘keeping up the appearance of meeting the demands of managerialism, whilst sustaining [one’s] professional educational values’ (Hoyle and Wallace, Citation2005, p. 158). My argument for adding in ‘principled infidelity’ comes partly from the survey, outlined above (), which suggests a less passive mentality than ‘pragmatic compliance’. Hoyle and Wallace argue that ‘principled infidelity’ relies on an ‘ironic orientation’, a disposition that allows school leaders ‘to flourish in circumstances of value conflict and irreconcilable demands’ (Hoyle and Wallace, Citation2005, p. 14). Thus, where ‘pragmatic compliance’ largely accepts the status quo and finds ways to work ethically within it, ‘principled infidelity’ is more mischievous and ironic – acknowledging the game that must be played but subverting it where possible.

Turning to the issue of localities, the three schools in vignettes 2–4 are in the same locality but there are clear differences in how each headteacher operates, indicating diverse underpinning values in relation to competition, collaboration, entrepreneurialism, knowledge-sharing and so on. Of course, these examples focus on approaches to knowledge sharing, where differences between schools might not be seen as particularly problematic, especially given that all three schools are performing well. The problems become more acute where schools adopt different approaches to admissions and behaviour/exclusions, since this can increase stratification and make it more likely that vulnerable children will fall between the cracks. Vignettes 2–4 thus offer an insight into broader debates about how far schools should be left to determine their own approach, in line with individual leaders’ values, and how far they should adhere to external policies and requirements. Michael Barber (Citation1994, p. 359) characterised this debate as ‘between Conservatives advocating diversity (and therefore … inequality) and socialists advocating equality (and therefore uniformity)’. His solution was to advocate a third way which offered equality and diversity – giving schools autonomy but holding them accountable for defined outcomes. Thirty years later, we see that both Labour and Conservative governments have encouraged school autonomy and diversity (Courtney, Citation2015), with parental choice as a key driver, while national standards and accountability help to ensure quality and performance. As we have seen, under the current framework the result is all too often ‘pragmatic compliance’ and growing inequality.

This brings us back to questions of structure, agency and values. One response is to critique and refine the policy framework, but the question here is whether and how leaders’ individual and collective values and agency can be strengthened in the face of these structural constraints. Encouragingly, one project I am currently evaluating is exploring how four local ‘school-led’ partnerships – in Ealing, Sheffield, Surrey and Milton Keynes – can work to strengthen professional/peer accountability between local schools in ways which help to mitigate the impact of national scrutiny and performativity (Greany and Cousin, Citation2023). Their efforts are by no means straight-forward, in particular in areas where many schools have joined different MATs that have their own locus and ways of working, but there is clear value in schools continuing to engage with such local partnerships and the networks and routines that they support. In the strongest of these partnerships there is evidence that the work is generating shared values and norms – or what Hargreaves (Citation2012) termed ‘collective moral purpose’ – across member schools.

This suggests that professional values must always be conceptualised, negotiated and enacted at both individual and collective levels in tandem. It is individual leaders who must live and breathe values to make them meaningful, but these values will only have legitimacy if they are negotiated and practiced by groups of leaders across localities and the wider school system. Once established, collectively-held-and-practised values have the potential to shape wider norms, cultures and policies. ASCL’s Framework for Ethical Leadership in Education (ASCL, Citation2019) offers a serious attempt to negotiate collective values at system level, but these debates must be sustained over time and encouraged at local levels in parallel to achieve consensus and shared action.

Drawing this argument together, offers a frame for assessing how individual and collective leadership values and agency interact with differing types of structural constraint to influence policy enactment. As I have tried to reflect in the article, I see leadership values as important but always intangible and often obscured, as plural and frequently in tension with each other, as shaped by policy structures and real-world constraints but also sometimes shaping these at local and national levels. Given all this, the frame is intended to provoke thinking and discussion rather than an evidence-based model.

6. Conclusion

This article has sought to unpick some of the ways in which leadership values influence practice at school, locality and system levels and the extent to which leaders are able to exert agency in the face of structural constraints.

In terms of its contribution, although much has been written about values in leadership, I am not aware of equivalent attempts to assess whether and how leaders’ values ‘matter’ in the context of contemporary policy and structural constraints. By seeking to illuminate issues of structure and agency in relation to leadership values and practices, the article arguable provides a bridge between existing work on transformational, ethical and authentic leadership and critical policy studies of policy enactment. In addition, by differentiating between how values operate within a single school and how they play out across localities and in the context of different governance mechanisms, the article brings together work across separate spheres (Begley, Citation2006). Finally, the article’s argument that leadership values and policy enactment should be seen on a spectrum, together with its frame for assessing interactions between individual and collective leadership values and policy enactment, are arguably significant and original.

Clearly, the approach has important limitations. Key here is scope; by trying to examine individual and collective values and school, locality and national processes all in one article, it risks skating over the surface of issues that arguably require depth and detail. Second, while the article does draw on empirical material, it is drawn from different studies, neither of which focussed specifically on values. Third, the argument is drawn solely from work in England, so the conclusions would benefit from being tested across a wider set of national contexts.

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to my co-researchers on the two research projects drawn on here for their collaboration and expertise – Dr Rob Higham, Dr Jodie Pennacchia, Jenny Graham and Eleanor Bernardes. They were integral to the thinking and analysis in the original studies and thus helped shape the ideas presented here.

8. Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Detailed methodologies – including processes for ethical approval – for the two studies drawn on here can be found in the respective project reports – Greany et al., Citation2024 and Greany and Higham, Citation2018.

2. This is not to deny that many decisions in schools are made based on established ways of working and regular rhythms and routines (Thomson and Greany, Citation2024).

3. These debates relate to the ‘paradox of embedded agency’ – i.e., if humans have ‘free will’ how can their agency be constrained by structure if not by voluntary choice? Vice versa, if structure determines human behaviour, how can there be place for agency? See Chaterjee et al. (Citation2021).

4. For details see: Greany et al. (Citation2024) Belonging Schools: how do relatively more inclusive secondary schools approach and practice inclusion? Teach 1st: London.

5. For details see: Greany and Higham (Citation2018) Hierarchy, Markets and Networks: analysing the ‘self-improving school-led system’ agenda in England and the implications for schools. London: IOE Press.

6. This raises an interesting question about whether and how values can permeate larger organisational groups, such as a Multi-Academy Trust or school district, but this goes beyond the scope of this article.

References

- Ahmed, E. (2023) A systematic review of ethical leadership studies in educational research from 1990 to 2022, Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 1–20. doi: 10.1177/17411432231193251.

- Askeland, H., Espedal, G., Løvaas, B. and Sirris, S. (2020) Understanding Values Work: Institutional Perspectives in Organizations and Leadership (London, Springer).

- Ball, S. J. (2003) The teacher’s soul and the terrors of performativity, Journal of Education Policy, 18 (2), 215–228. doi: 10.1080/0268093022000043065.

- Barber, M. (1994) Power and control in education 1944–2004, British Journal of Education Studies, 42 (4), 348–362. doi: 10.1080/00071005.1994.9974008.

- Begley, P. (2012) Leading with Moral Purpose: The Place of Ethics. In M. Preedy, N. Bennett, and C. Wise (Eds) Educational Leadership: Context, Strategy and Collaboration (London, SAGE Publications), 38–51.

- Begley, P. T. (2006) Self-knowledge, capacity and sensitivity: prerequisites to authentic leadership by school principals, Journal of Educational Administration, 44 (6), 570–589. doi: 10.1108/09578230610704792.

- Bennett, T. (2018) Yes, school exclusions are up. But zero-tolerance policies are not to blame, The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2018/jul/26/school-exclusions-zero-tolerance-policies-disruptive-pupils.

- Burns, T. and Köster, F. (Eds) (2016) Governing Education in a Complex World, Educational Research and Innovation (Paris, OECD Publishing).

- Bush, T. (2017) The enduring power of transformational leadership, Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 45 (4), 563–565. doi: 10.1177/1741143217701827.

- Bush, T. and Glover, D. (2014) School leadership models: what do we know?, School Leadership & Management, 34 (5), 553–571. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2014.928680.

- Chang, S. M., Budhwar, P. and Crawshaw, J. (2021) The emergence of value-based leadership behavior at the frontline of management: A role theory perspective and future research agenda, Frontiers in Psychology, 12. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.635106.

- Chatterjee, I. and Cornelissen, J. (2021) Social entrepreneurship and values work: the role of practices in shaping values and negotiating change, Journal of Business Venturing, 36 (1). doi: 10.1016/j.jbusvent.2020.106064.

- Coates, M. (2021) Setting directions: vision, values and culture. In T. Greany and P. Earley (Eds) School Leadership and Education System Reform (2nd edn) (London, Bloomsbury), 71–81.

- Courtney, S. (2015) Mapping school types in England, Oxford Review of Education, 41 (6), 799–818. doi: 10.1080/03054985.2015.1121141.

- Cousin, S. (2019) System Leadership: Policy and Practice in the English Schools System (London, Bloomsbury).

- Craig, I. (2021) Toxic leadership. In T. Greany and P. Earley (Eds) School Leadership and Education System Reform (2nd edn) (London, Bloomsbury), 243–252.

- Day, C. and Gu, Q. (2018) How successful secondary school principals in England respond to policy reforms: the influence of biography, Leadership and Policy in Schools, 17 (3), 332–344. doi: 10.1080/15700763.2018.1496339.

- Demont‑Biaggi, F. (2020) How ethical leadership is related to authenticity, Leadership, Education, Personality: An Interdisciplinary Journal, 1 (1–2), 15–28. doi: 10.1365/s42681-020-00006-1.

- Department for Education (ENGLAND). (2020) Headteachers’ Standards 2020 (London, DfE).

- Espedal, G., Løvaas, B. J., Sirris, S. and Wæraas, A. (2022) Researching values in organisations and leadership. In G. Espedal, B. Jelstad Løvaas, S. Sirris, and A. Wæraas (Eds) Researching Values (Cham, Palgrave Macmillan), 1–12.

- Ethical Leadership Commission. (2019) Framework for Ethical Leadership in Education (London, Chartered College for Teaching).

- Exworthy, M., Powell, M. and Mohan, J. (1999) The NHS: Quasi-market, quasi-hierarchy and quasi-network? Public Money and Management, 19 (4), 15–22. doi: 10.1111/1467-9302.00184.

- Greany, T. and Cousin, S. (2023) Educating for the future: developing new locality models for English schools - Year 1 (2022-2023) evaluation report. (London, Association of Education Committees).

- Greany, T. and Higham, R. (2018) Hierarchy, Markets and Networks: Analysing the ‘Self-Improving School-Led System’ Agenda in England and the Implications for Schools (London, IOE Press).

- Greany, T. and Higham, R. (2021) School system governance and the implications for schools. In T. Greany and P. Earley (Eds) School Leadership and Education System Reform (2nd edn) (London, Bloomsbury), 37–46.

- Greany, T., Pennacchia, J., Graham, J. and Bernardes, E. (2024) Belonging Schools: How Do Relatively More Inclusive Secondary Schools Approach and Practice Inclusion? (London, Teach 1st). https://www.teachfirst.org.uk/belonging-schools.

- GTC Scotland. (2021) The Standard for Headship (Edinburgh, General Teaching Council for Scotland).

- Hargreaves, D. (2012) A Self-Improving School System: Towards Maturity (Nottingham, National College for School Leadership).

- Higham, R. (2021) Ethical leadership. In T. Greany and P. Earley (Eds) School Leadership and Education System Reform (2nd ed) (London, Bloomsbury), 253–262.

- Hood, C. (1991) A public management for all seasons, Public Administration, 69 (1), 3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x.

- Hoyle, E. and Wallace, M. (2005) Educational Leadership: Ambiguity, Professionals and Managerialism (London, Sage).

- Jessop, B. (2011) Metagovernance. In M. Bevir (Ed.) The SAGE Handbook of Governance (London, SAGE Publications), 106–123.

- Leithwood, K. and Steinbach, R. (1992) Improving the problem-solving expertise of school administrators: theory and practice, Education and Urban Society, 24 (3), 317–345. doi: 10.1177/0013124592024003003.

- Newman, J. and Clarke, J. (2009) Publics, Politics and Power: Remaking the Public in Public Services (London, SAGE).

- Nolan principles – aka the seven principles of public life (1995) UK Government. Accessed: https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/the-7-principles-of-public-life/the-7-principles-of-public-life–2.

- Ofsted annual report and accounts 2021–22 (2022) (London, Ofsted).

- Perryman, J. (2009) Inspection and the fabrication of professional and performative processes, Journal of Education Policy, 24 (5), 611–631. doi: 10.1080/02680930903125129.

- Samier, E. and Milley, P. (2018) Introduction: the landscape of maladministration in education. In Samier and Milley (Eds) International Perspectives on Maladministration in Education: Theories, Research and Critiques (New York, Routledge), 1–16.

- Snape, R. (2021) The Headteacher’s Handbook: The Essential Guide to Leading a Primary School (London, Bloomsbury).

- Stewart, J. (2009) Public Policy Values (London, Palgrave Macmillan).

- Thomson, P. (2020) School Scandals: Blowing the Whistle on Corruption in Our Public Services (Bristol, Policy Press).

- Thomson, P. and Greany, T. (2024) The best of times, the worst of times: continuity and uncertainty in school leaders’ work, Educational Management Administration & Leadership. doi: 10.1177/174114322312185.

- Tschannen-Moran, M. (2004) Trust Matters: Leadership for Successful Schools (San Francisco, CA, Jossey-Bass).