Abstract

The worst of the Covid-19-induced economic crisis appears to be behind Indonesia, with the economic contraction lessening in the second half of 2020. While the economic downturn in Indonesia has been modest compared with downturns in peer countries, Indonesia’s handling of the pandemic has been lacking. Almost a year into the pandemic, the country was still struggling with the first wave of infection as the number of new cases reported each day continued to rise. Facing criticism over the government’s handling of the pandemic, President Joko Widodo reshuffled his cabinet at the end of 2020. This Survey examines Indonesia’s plans to manage a longer-than-expected recovery from the effects of the pandemic. We see that much of the labour market is adjusting to widespread loss of employment by shifting into the agricultural sector. We also see an increase in informal employment, leading to a lower unemployment rate than expected. We argue that the pandemic has exacerbated Indonesia’s long-standing structural problems. In addition to responding to the immediate crisis issues, the government must start addressing medium-term challenges and seizing reform opportunities. We discuss the existing recovery policies, including the vaccination strategy and the omnibus law on job creation. We argue that the omnibus law alone is necessary but will not be enough to improve the investment climate and create jobs for economy recovery and long-term structural transformation.

Bagian terburuk dari krisis ekonomi akibat Covid-19 di Indonesia nampaknya telah berlalu, dengan kontraksi ekonomi yang berkurang di Semester II – 2020. Meskipun dampak ekonomi di Indonesia cukup ringan dibandingkan di beberapa negara lain, penanganan pandemi Indonesia masih tidak memadai. Satu tahun memasuki pandemi, Indonesia masih berjuang mengatasi gelombang pertama infeksi seiring dengan kenaikan jumlah kasus setiap harinya. Menghadapi kritik terhadap penanganan Covid-19, Presiden Joko Widodo (Jokowi) merombak kabinetnya di akhir 2020. Survei ini mengkaji strategi Indonesia untuk mengelola pemulihan dari pandemi yang memakan waktu lebih panjang daripada yang diperkirakan sebelumnya. Kami menemukan bahwa pasar tenaga kerja tengah beradaptasi atas hilangnya lapangan kerja secara besar-besaran dengan bergeser ke sektor pertanian, diikuti dengan pertambahan pekerja informal, sehingga angka pengangguran lebih rendah dari yang diperkirakan. Kami melihat bahwa pandemi semakin memperburuk tantangan-tantangan struktural Indonesia yang telah ada sejak lama. Selain tanggap merespon isu krisis, pemerintah harus mulai menyasar tantangan-tantangan jangka menengah dan menangkap peluang reformasi. Kami membahas kebijakan-kebijakan pemulihan yang ada, termasuk strategi vaksinasi dan Undang-Undang Cipta Kerja. Penulis melihat bahwa keberadaan omnibus law ini memang penting, namun belum cukup untuk meningkatkan iklim investasi dan menciptakan pekerjaan bagi pemulihan ekonomi dan transformasi struktural jangka panjang.

INTRODUCTION

On 22 December 2020, President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) announced a cabinet reshuffle. Involving six ministries, the reshuffle followed public outrage over alleged corruption and poor performance. Former social affairs minister Juliari Batubara had been accused of taking bribes relating to the government’s distribution of Covid-19 aid, while former fisheries minister Edhy Prabowo had been arrested for alleged corruption. Jokowi had first talked about a potential reshuffle in June, when he reprimanded ministers for failing to effectively handle the pandemic and its economic effects. He specifically chastised the health ministry, which had been allocated a budget of Rp 75 trillion but had used less than 2% of it. At the time, public frustration with the performance of controversial former health minister Terawan Agus Putranto was also high, although much of his authority had already been shifted to the Covid-19 Handling and National Economic Recovery Committee (KPCPEN).

The reshuffle appeared to give the public some hope that the government would improve its pandemic handling and economic recovery efforts, although some critics questioned new health minister Budi Sadikin’s lack of medical credentials, and the decision to recruit a former opponent, vice presidential candidate Sandiaga Uno, into Jokowi’s camp. Some also criticised the reshuffle as being too late, noting that it may prove to be ineffective without a fundamental change to the government’s policy and development strategy.

In this Survey, we focus on the current state of the pandemic, its economic impact and the government’s handling of the crisis. We evaluate the government’s attempts not only to address the medium-term challenges of the crisis but also to seize opportunities for structural reform, specifically through implementing the omnibus law on job creation.

In the next section, we discuss how Indonesia has continued to struggle to contain the health crisis. We then discuss the government’s primary strategy for national recovery: ‘herd immunity’ through vaccination. In the second section, we present an economic update discussing the economic impact of Covid-19. We argue that the economy may have already seen the worst of the pandemic’s effects, as the rate of economic contraction was slowing in the second half of 2020. However, we argue that the damage inflicted by the crisis on the labour market has been considerable. In the last section, we argue that the pandemic has scarred the economy and a longer recovery period is becoming more likely.

The pandemic has highlighted public capacity constraints and exacerbated long-standing structural issues in the Indonesian economy. During the economic recovery, maintaining purchasing power and creating jobs are the government’s priorities, but it is equally important to seize the opportunity for structural reform by addressing supply-side constraints, such as complex and cumbersome business licensing processes and regulations, inadequate infrastructure and a lack of skilled labour to improve the business climate. We argue that the omnibus law on job creation is a necessary but deficient policy tool for addressing those constraints. Effective implementation of the law’s provisions is essential to attract better investment and to create jobs. Other reforms are also imperative, including in the areas of trade policy, finance and revenue.

THE COVID-19 SCENE: A NEVER-ENDING FIRST WAVE?

The State of the Spread

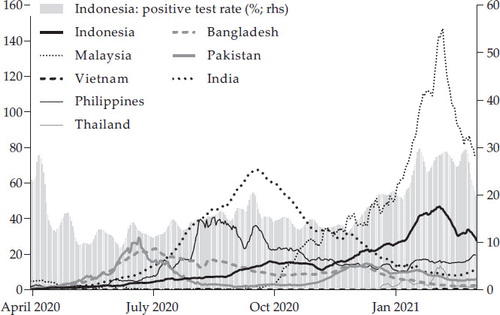

Almost a year after the first cases of Covid-19 were confirmed in Indonesia, the country’s case numbers continued to rise. From 1 December 2020 to 31 January 2021, the number of daily new cases per one million people more than doubled, from about 20 to 47 (). In the same period, the rate of positive tests for Covid-19 increased from 15 to 30.Footnote1 Such a high rate suggests an even higher rate of Covid-19 infection in the community, underscoring concerns about the ineffectiveness of health protocols and the overall handling of the pandemic (Sucahya Citation2020; Djalante et al. Citation2020). Deaths caused by Covid-19 dramatically increased from early December 2020. At the time of writing, about 39% of all Covid-19 fatalities in Indonesia had occurred between December 2020 and January 2021 (Couper and Curnow Citation2021). Burials in Jakarta were about 60% higher in 2020 than the average of the past five years, indicating that the mortality associated with Covid-19 is far higher than official data has suggested. It also suggests that community transmission may have begun at least two months before the first case was announced (Elyazar et al. Citation2020).

FIGURE 1 New Daily Cases per One Million People for Selected Asian Countries (lhs), and Positive Test Rates for Indonesia (rhs)

Source: Our World in Data.

Notes: The confirmed new daily cases were calculated based on the seven-day rolling average. The positive test rate is the percentage of tests that confirm Covid-19 cases. WHO recommends that a country achieve a positive test rate of at most 5% to enter a ‘new normal’. In addition to data on ASEAN countries, data on India, Bangladesh and Pakistan have been included, because each of their populations is similar in size to Indonesia’s population.

The surging number of cases and rising fatality rate have put great stress on the healthcare system. In late December 2020, the health ministry reported that intensive care units (ICUs) and isolation facilities in several major cities had reached capacity. For example, the ICU and isolation facilities in Bandung had reached about 98% and 89% of their capacities, respectively; in Jakarta, the facilities had reached 79% and 85%; and in Semarang, they had reached 76% and 89%. This highlights the urgent need to increase the capacity of healthcare facilities dedicated to treating Covid-19 patients. In January 2021, the health ministry advised hospital owners across the country to allocate up to 40% of their beds to Covid-19 patients. This move came in addition to the government’s plan to increase the number of active healthcare workers across the country and its push for more hospital involvement in convalescent plasma therapy for Covid-19 patients.Footnote2 In his first month in office, new health minister Sadikin significantly revised the regime for testing and tracing. This included massively increasing testing capacity by allowing the use of a simpler but effective swab for antigen tests; ramping up contact tracing to include all close contacts of Covid-19 cases; increasing the number of tracers to 30 for every 100,000 people; providing cash support to the public during mandatory isolation periods; and planning a more holistic surveillance program for 2021.Footnote3

Vaccination

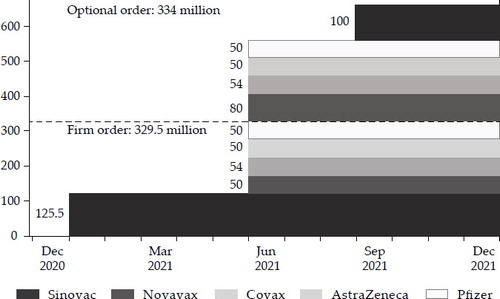

Amid the record-breaking number of positive cases and the intensifying global race to secure vaccines, Sadikin’s appointment as health minister sent a clear signal that mass vaccination would become the focus of Jokowi’s administration in 2021. Sadikin was instrumental in the early efforts to procure vaccines for the nation, when he served in KPCPEN. However, procurement is only one of several issues looming around vaccination: prioritisation (who should get the vaccine first), distribution, private sector and local government involvement, and public acceptance of the vaccine are also important for ensuring that the vaccine is rolled out smoothly and that herd immunity is achieved quickly ( shows details of the planned rollout as of 3 February 2021).

Table 1. Planned Vaccine Rollout

Prioritisation in particular has become contentious, since several countries, including Indonesia, have assigned some Covid-19 vaccines ‘emergency use authorisation’, a mechanism which allows the use of the vaccines in certain situations, though they may not yet be officially approved. The most logical prioritisation strategy is to first vaccinate high-risk groups and healthcare workers (WHO 2020). While health workers did receive the first jabs, the Indonesian government prioritised public sector workers aged 18–59 ahead of vulnerable elderly people for the early wave of the vaccination. However, in early February, the government’s food and drug agency (BPOM) approved the use of the CoronaVac (Sinovac) vaccine, manufactured under licence from China’s Sinovac Biotech, for the elderly, about a month after it began rolling out the vaccine for health workers and government officials. The delay occurred partly because of limitations in the third phase of the clinical trial in Bandung, West Java. Namely, the trial could test the vaccine’s safety and efficacy only for people aged 18–59, because the preliminary safety data from Sinovac were available only for this age group (Zhang et al. Citation2020).

The massive need for vaccine highlights the importance of securing and diversifying vaccine supply, which is a daunting task for the government, given that it believes it will need to vaccinate 70% of the Indonesian population to ensure herd immunity. As shown in , Indonesia confirmed in February that it would procure almost 330 million vaccine doses from four producers and the Covax facility. These include doses of the Novavax, Pfizer and AstraZeneca vaccines. About 54 million doses have been procured through Covax, a global cooperation facility aimed at ensuring that developing countries have access to Covid-19 vaccines. The Sinovac vaccine will be used exclusively in the early wave of vaccination, involving about 3 million injections. About 38 million doses had already been delivered to Indonesia at the time of writing, while doses from other producers were scheduled to arrive by the middle of the year. Another optional order of 334 million doses had been reserved to ensure adequate coverage. Nevertheless, details about the optional orders were lacking at the time of writing, and the risk of ‘vaccine nationalism’ around the world—which may delay the availability of vaccines for some countries and prolong the health crisis—cannot be ruled out.

FIGURE 2 Scheduled Supply of Vaccine Doses (millions)

Source: Ministry of Health presentation, 3 February 2021.

Distributing the vaccine throughout Indonesia’s vast archipelago is a logistical challenge that will push its cold chain—a temperature-controlled supply chain— to its limits. The government has realised this and has reached out to the private sector for help distributing the vaccines. Recently, it asked British consumer goods multinational Unilever for help distributing the vaccines through its extensive cold chain, which usually distributes ice cream across the nation (Wulandhari Citation2021). Constraints on the logistical capacity may limit the mix of vaccines that is deliverable. For example, the Pfizer vaccines use messenger ribonucleic acid (mRNA) technology and therefore need to be kept ultra-cold (about –70 Celsius). This means distributing the vaccines to rural areas in Java or to other islands, which may lack adequate storage facilities, will be difficult.

Another challenge is that the numbers of vaccination facilities and trained health workers are limited. Prior to the pandemic, many puskesmas (community health centres) were not fully staffed and lacked equipment (Booth, Purnagunawan and Satriawan Citation2019). Only about 78% of the 10,000 or so puskesmas across the country have refrigerators that can store vaccines. Moreover, not every subdistrict has access to puskesmas. The central government must work with local governments and other stakeholders to address these distribution and implementation challenges. It must also implement policies that support its efforts to address the challenges. These could include policies that allow local governments to use village funds to procure appropriate equipment and to help community members, especially the poor and those living in remote areas, to cover the out-of-pocket expenses of seeking vaccination.

While Jokowi has made clear that the Covid-19 vaccines will be free, financed entirely by the state budget, the private sector’s demand for a commercial vaccine has been growing. This would allow firms to expedite the inoculation of their workers and more quickly return to pre-Covid-19 levels of productivity (Fauzie Citation2021). At first, the call for a commercial vaccine seems innocent. However, given that the availability of vaccines is limited worldwide, the private sector risks crowding out allocations on the supply side of the Covid-19 vaccine market if the government allows it to purchase the vaccines en masse, potentially preventing vulnerable groups from receiving timely vaccination.

Another challenge is the reluctance of many Indonesians to accept vaccination. A recent survey on vaccine acceptance in Indonesia shows that about one in three respondents is not sure that they want to be vaccinated, with low-income respondents even more reluctant to accept vaccination (Ministry of Health et al. 2020). Widely circulating disinformation and false news on vaccines also contribute to growing scepticism of vaccination (Alhamidi Citation2021). The importance of effective public communication to ensure that the mass vaccination program runs smoothly cannot be stressed enough. This communication must also include the use of social media, as 54% of hesitant respondents seek more information from that channel than any other source.

To achieve its target of vaccinating 70% of the population in 15 months, the government will need health workers to give one million vaccine injections per day. Given that health workers gave only 64,000 injections per day in early February, this target seems very ambitious. The government has not made a detailed vaccination strategy public. However, the government has argued that Indonesia was able to successfully deliver 70 million measles and rubella vaccines to children across Indonesia within two months in 2008 (Asmara Citation2021).Footnote4

ECONOMIC UPDATE AND COVID-19 IMPACT

Economic Growth

While Indonesia has yet to see the end of the health crisis, it may have seen the worst of the economic crisis. Indonesia’s economy contracted by 2.2% year on year in the fourth quarter of 2020, a contraction significantly smaller in magnitude than in the previous two quarters (see ). Overall, after 3% growth in the first quarter, Indonesia’s economy contracted by about 2% in 2020 year on year. This is the first recession since the Asian financial crisis (AFC), given that Indonesia was relatively unharmed during the global financial crisis (GFC) (Basri and Hill Citation2011). Nonetheless, various high-frequency indicators of economic activity—such as the retail sales index, auto sales figures and consumer confidence—have suggested economic improvement in the second half of 2020, though the economy is still not as strong as it was before the crisis. Real-time indicators—such as the Google mobility index, Facebook mobility index, Bloomberg activity index and Prospera night light index—have suggested similar developments: economic activity has increased since the worst of the economic crisis, but this activity is still less than it was pre-crisis.

Table 2. Components of GDP Growth, 2019–2020 (2010 prices)

Income loss translated into weaker consumption. Consumer confidence did not improve significantly until the end of 2020. The present condition component of the consumer confidence index is still in pessimistic territory, suggesting that households now earn less, have access to fewer jobs and perceive that the current condition of the economy is less suitable for purchasing durable goods than the condition in mid-2020 (BI 2020). Nevertheless, the contraction has started to ease, with household consumption in the fourth quarter of 2020 down by 3.6% year on year, much less than the 5.5% year-on-year contraction seen in the second quarter. This improvement has been helped by various fiscal support programs, especially for households. Before the end of 2020, we saw the yearly core inflation rate at a record low of 1.6% year on year, suggesting weak demand.

The government’s stimulus program started to produce results in the second half of 2020. The government also ramped up spending in the third quarter by 9.8% year on year, after a contraction of 6.5% year on year in the second quarter. This government consumption, which mostly consisted of wage and operational spending, was able to quickly rebound as the government adapted through budget reallocation and support for civil servants, such as stipends for internet subscription and digital infrastructure spending. Nonetheless, the pandemic limited the usual end-of-year spending (such as on travel and meetings), by both the central government and local governments, as reflected by an increase in spending of only 1.8% in the fourth quarter, smaller than in the previous quarter.

Public investment projects that had halted in the second quarter resumed in the third quarter, but the private sector was still cautious with regard to investment. Overall investment declined by 6.5% year on year in the third quarter. However, investment in cultivated biological resources rose. This contributed positively to GDP growth in the fourth quarter, although only slightly. The improvement was likely related to the increasing demand for crude palm oil, given that its prices rose to their highest levels in almost nine years, at least partly because the supply of other vegetable oils was disrupted by climate events, such as drought.

Indonesia’s net exports position appeared to improve, given that exports contracted less than imports. In real terms, imports fell by 13.5% year on year, while exports fell by 7.2% year on year in the fourth quarter. The economic recovery of trading partners, mainly China, has revitalised demand for Indonesian products, such as crude palm oil and industrial metals. Regardless, the decline in imports suggests that most Indonesians responded to income loss by reducing their purchases of imported consumer goods, materials and capital goods more than their purchases of domestically produced goods and services.

Labour Markets

As the economy plunged into crisis during the pandemic, many firms began to shed their workers. Before Covid-19 was an issue, data from the 2015 Statistics Indonesia (BPS) survey on micro and small manufacturing firms indicated that most micro and small firms were highly susceptible to operational shock. The survey found that the median cash buffer of micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs) in Indonesia was enough to cover about 11 days of operational costs. Furthermore, almost 80% of firms would be unable to survive for more than 30 days without income from operating. The effect of the country’s social distancing restrictions (PSBBs) on economic activity, along with declining demand for consumables, will continue to put pressure on these already vulnerable firms. Data from a recent wave of Prospera’s longitudinal business survey show that a reduction in revenue due to the crisis has very likely already had a significant effect on firms: about 80% of the firms surveyed reported reductions in their workforce size, with staff cuts at micro and small firms particularly prevalent.Footnote5

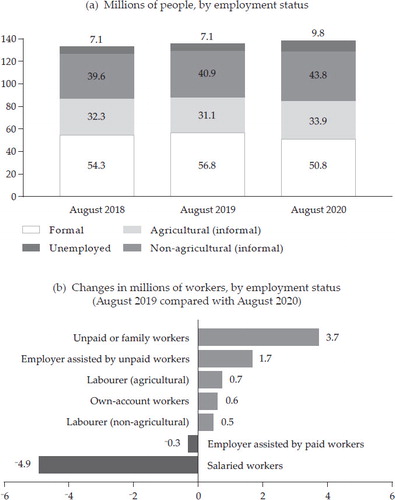

The associated job loss due to the downsizing of businesses is also captured in the headline labour market statistics. Based on data from the National Labour Force Survey (collected twice a year, in February and August), BPS reports that the unemployment rate increased to 7.1% in August 2020, from 4.0% in February 2020 and 5.2% in August 2019. This equates to about 2.8 million more unemployed people than in the same period a year prior, reversing nine years of progress in reducing unemployment. While the increase in unemployment is expected, given the contraction in the economy in the second and third quarters of 2020, the magnitude is modest compared with earlier government projections.

However, a different picture emerges from a closer look at the labour market. Data from the National Labour Force Survey show that the economic crisis has directly affected the employment of more than 29 million workers, or 21% of the Indonesian labour force ().Footnote6 The number is high compared with the figure for unemployment probably because about 24 million workers have been working fewer hours while nearly 2 million are temporarily not working. also shows that workers in urban areas make up most of the affected workers.

Table 3. Covid-19 Direct Impact on Labour Market (August 2020)

As was the case after the AFC more than 20 years ago, the labour market is adjusting to the effects of the crisis on employment by shifting towards the agriculture sector and informal employment. This is indicated by the addition of 2.8 million informal agricultural workers in August 2020, compared with August 2019. Meanwhile, the percentage of workers in non-agricultural sectors decreased significantly (). This development comes despite decreases in wage rates, both in real and nominal terms, even in the agricultural sector.

Table 4. Changes in Wages and Employment (August 2019 compared with August 2020)

Furthermore, the number of formal workers decreased by about six million in August 2020, compared with the same period last year (a). The increase was driven largely by a decrease in the number of salaried workers by 4.9 million (b). Many of the displaced salaried workers have been turning to unpaid family work, which is reflected in the increase in the number of unpaid family workers by 3.7 million.Footnote7

The recent changes in Indonesia’s labour market are not unique from a historical standpoint. The structure of the Indonesian labour market, which is characterised by sizeable agricultural sector employment and a high informality level, allows workers to adapt to the adverse effects of crises by switching sectors. This sectorswitching was observed during the AFC of 1997–98, where we saw a pattern of migration from urban to agricultural areas (Manning Citation2000; Hugo Citation2000; Fallon and Lucas Citation2002). For displaced workers, the agricultural sector acts as an informal social safety net when a formal one is not in place or is not adaptive enough to provide protection against poverty for workers who lose employment. Most worrying about this structural transformation is the long-term impact it may have on the absorption of labour into the formal employment market. In the aftermath of the AFC, the manufacturing sector lost its ability to create meaningful formal employment, even as output bounced back (Aswicahyono, Hill and Narjoko Citation2010). Since the AFC, formal sectors have been able to absorb less labour, partly because labour market regulation has become more rigid, and the formal jobs that have been lost are not returning as a result. This further highlights the need for a labour market environment that can guide recovery from the impacts of Covid-19.

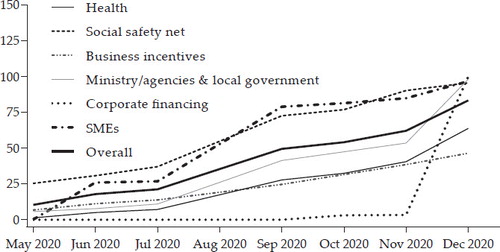

Government Support

In response to the Covid-19 shock, the government allocated about Rp 695 trillion to various initiatives under the National Economic Recovery (PEN) program (see Sparrow, Dartanto and Hartwig (Citation2020) for more detail). It was challenging to finance the program, and the disbursement was initially slow. However, the government managed to increase its spending on the initiatives to about 83% of the overall allocation for 2020 by late December, up from just 21% in July (). Looking at the budget realisation for specific initiatives, we see that the government had spent only 64% of the budget for health support and 47% of the budget for business incentives by late 2020. Conversely, it had spent 96% of its budget for household support, the recovery package’s largest component. This is partly because the government can largely provide the support through existing programs, such as the Hopeful Families Program (PKH), food assistance programs and the village fund program, which already have frameworks and databases, albeit flawed, for targeting eligible recipients of assistance. This has likely helped the government to scale up its provision of social protection during Covid-19, although this provision is still lacking compared with that of some peer countries (Gentilini et al. Citation2020).Footnote8 Compared with the poor of the 1998 recession, the poor of today are now much more likely to receive government support. However, the government still faces major challenges in ensuring its programs effectively target and cover the Indonesians most in need (Sparrow, Dartanto and Hartwig Citation2020; Tohari, Parsons and Rammohan Citation2019).

FIGURE 4 Realisation of 2020 National Economic Recovery (PEN) Program (%)

Source: Ministry of Finance. Owing to data limitations, the budget realisation for August was extrapolated using the average between July and September.

A significant challenge is to extend support to the newly poor, who were not eligible for it before the crisis. To meet this challenge, the government has extended the duration of its electricity subsidy program, expedited the implementation of its pre-employment card, and increased its wage subsidy program to include an additional 2.7 million workers, now covering 15.7 million in total.Footnote9 While the programs supporting households have been relatively successful, they are in urgent need of improvement. Aside from updating the database used to target the intended beneficiaries of support, the government could use other data sources, including on-demand applications for assistance, to improve targeting. It could also consider a community-based targeting approach, which allows communities to identify their own beneficiaries, and could link social protection programs to region-specific health measures, as this may significantly improve the program design (Karina Citation2020).

The government has so far provided three kinds of business support: programs for MSMEs, corporate financing programs that mostly focus on state-owned enterprises (SOEs), and business incentives. However, the implementation of these programs has often been constrained by unclear and complex bureaucratic processes across the implementing agencies, and by administrative barriers to identifying intended program beneficiaries, such as unconsolidated databases, a lack of socialisation for programs and unclear mechanisms for transferring assistance. A new credit guarantee program—announced in mid-2020 to secure working capital loans for MSMEs—fell apart in the execution phase because of such problems. Aside from the slow disbursement of funds, some of the business support initiatives have been widely criticised for being ineffective and having limited reach.Footnote10 For example, the business incentive programs are pointless if most businesses are not generating revenue and the labour market is highly informal. The only pre-existing program providing business support is the credit guarantee scheme (KUR) introduced in 2007 for MSMEs, but its coverage is limited. By the end of 2019, the scheme had about 4.7 million debtors among more than 64 million MSMEs in Indonesia.Footnote11 The government should better communicate what support is available to firms, considering that many are not aware that any assistance is available. The government should also improve the process of assessing the eligibility of potential aid recipients, since few firms receive assistance. For example, in a recent survey of Indonesian firms, only 49% of firms had received government assistance by October 2020 (World Bank Citation2020). Improving the access that smaller firms have to wage subsidisation is an option for broadening the coverage, as the survey found that only large firms, not MSMEs, had accessed wage subsidies.

For 2021, the government allocated about Rp 699 trillion to the PEN program (). From January to February 2021, it revised the PEN budget allocations four times (Thomas Citation2021). We argue that, given the budget constraints, the 2021 PEN program should prioritise Covid-19 handling programs and support households through improved coverage and targeting. A labour-intensive public works program at the community level could also be implemented to generate employment during the crisis, as was done during the AFC.

Table 5. Budget for National Economic Recovery (PEN) Initiatives (Rp trillion)

Although Indonesia’s Covid-19-related fiscal stimulus seems large from a historical perspective, it is small compared with the packages of many other countries. At the time of writing, the value of the country’s fiscal stimulus package was only about 4% of GDP, while the values of India’s, Brazil’s and Thailand’s packages were about 7%, 15% and almost 13% of their GDPs, respectively (IMF 2020). Beyond fiscal stimulus, the public sector’s capacity to manage the crisis—such as its capacity to adapt, learn and align public services as needed—affects national health and economic outcomes (Mazzucato and Kattel Citation2020). Vietnam has managed to quickly recognise the complexity of the Covid-19 problem by implementing a targeted testing regime and community-based surveillance program worth just under 2% of GDP. This has resulted in less need for stimulus, and the country still managed to achieve almost 3% GDP growth in 2020 (Mirchandani Citation2020; Nguyen Citation2020).

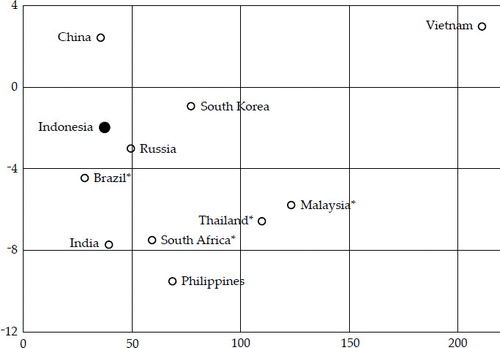

Indonesia’s economic performance is strong compared with that of its peers, except for China and Vietnam. We see this as a combination of good policy choice and luck. First, Indonesia’s virus containment measures have been relatively lenient (Setiati and Azwar Citation2020). The government’s justifications for this leniency include the high informality in the labour market, a constrained budget and weak institutional capacity for enforcing containment measures. In addition, the pandemic’s shock to the global supply chain has had a relatively modest effect on Indonesia, since the country is less integrated with the global trade network (Ing and Kimura Citation2017). shows that countries that are less open to global trade tend to be less economically affected by pandemics. Of course, other factors are at play, such as how effectively a country handles a pandemic. Vietnam is the outlier, most likely because of its robust foreign direct investment—a continuation of a production hub relocation from China partly due to the US–China trade dispute— and a relatively contained health crisis. Third, high commodity prices at the end of 2020 and the fast recovery of Indonesia’s primary market for commodities, China, have also eased the contraction in Indonesian exports. The disruption of the global production and supply of edible oils other than crude palm oil has increased the price and demand for Indonesian crude palm oil (Das Citation2020). Lastly, Indonesia has benefited from recent diplomatic tensions that have led China to all but cease coal imports from Australia, which had been China’s major supplier, and import much more coal from Indonesia (Russel Citation2021).

FIGURE 5 GDP Growth Rate (%; y axis) by Index of Trade Openness (x axis) for Selected ASEAN and BRICS Countries in 2020

Source: IMF.

Notes: Openness is the sum of exports and imports as a percentage of GDP in 2019. * Projections from the January 2021 IMF World Economic Outlook were used to estimate economic growth in 2020, because the official figures for 2020 had not been released at the time of writing. BRICS stands for Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa.

SEIZING REFORM OPPORTUNITIES: FROM RECOVERY TO STRUCTURAL REFORM

The pandemic has been disrupting productivity and thus output. This reduction in output, which is reflected in business bankruptcy and disruption to resource reallocation, is not unique to Indonesia (IMF 2020). Past epidemics in other countries were associated with reductions of about 6% in labour productivity (Vorisek Citation2020).Footnote12 Although the decline in Indonesia’s GDP in 2020 was relatively small, the pandemic’s effect on the economy is likely more profound than it seems. The extent of the disruption is not only hidden by the seemingly modest increase in unemployment figures, but also buried in data from the banking sector. Nonperforming loans had risen to 3.2% by November 2020, from 2.5% at the end of 2019. This figure could be much higher had the Indonesian Financial Services Authority not relax the criteria for restructuring credit.

Moreover, the vast and abrupt rise of online learning and the stretch of health service capacity may affect future human capital quality. Indonesian students are estimated to have lost 11 score points in the OECD’s Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), and $249 in future annual individual earnings, because of the four-month school closure from 24 March to the end of July 2020 (Yarrow, Masood and Afkar Citation2020).Footnote13 Furthermore, the Indonesian Medical Association has argued that the health of 25 million Indonesian toddlers is at risk because the pandemic has disrupted the services provided by integrated health service posts (posyandu). As revealed by the health ministry, posyandu have been unable to optimally provide almost 90% of essential services for infants and pregnant women during the pandemic (Jakarta Post 2020).

Meanwhile, the pandemic has led to less fiscal flexibility for Indonesia, as revenue has decreased and the obligations of servicing the country’s debt have increased. While Indonesia has less public debt as a percentage of GDP than many other G20 countries, it is known to generate less tax revenue as a percentage of GDP than other emerging markets (de Mooij, Nazara and Toro Citation2018). The pandemic has affected the profitability of many Indonesian businesses, which will likely lead to the collection of less income tax than usual in the short term. In the longer term, tax collection will also be affected by a principle of the Indonesian taxation system in which business losses may be carried forward by five years, and by continued reductions of the corporate tax rate.Footnote14 If the government cannot increase its capacity to raise revenue, it will have to reduce its spending to reinstate the deficit cap of 3% of GDP in the near future.

The health and economic crises have highlighted public sector constraints that policy urgently needs to address. While the government’s vaccination strategy has been a way of addressing the health crisis, its main strategy for managing the economic crisis has been the development of an omnibus law for the labour market (Law 11/2020 on Job Creation). Although it conceived the law before the pandemic, the government insists that the law will bring the investment needed to create jobs and mend the economy. If the law is effective, critics will have less cause to judge Indonesian policymakers harshly in the light of Sadli’s Law—the well-known hypothesis that times of prosperity lead to poor economic policies while times of crisis lead to good policies.

Omnibus Law on Job Creation: A Foundation for Structural Reform?

The development of the omnibus law on job creation is a significant attempt to improve the investment climate, stimulate economic activity and create more jobs as Indonesia emerges from the crisis. The government’s efforts started in 2016–18 with the implementation of changes that were hindered by the complexity and overlap in regulations across the central and local levels of government. The earlier draft of the law focused on improving the ease of doing business in Indonesia through a streamlined online single submission system for business licensing, and other reforms to the business environment. However, momentum for reform led policymakers to cover more areas in the later draft, such as labour, investment and central–local government authority. The government sent the draft to the Parliament in January 2020, before inviting limited public discussion on it from February to April. The Parliament first discussed the law formally on 14 April 2020 and, after about 64 parliamentary meetings, approved it on 5 October 2020. The core purpose of the reform is to strengthen the economy by increasing competitiveness, creating jobs and making it easier to do business in Indonesia. The law is intended to allow millions of people to gain access to better jobs, to move from informal to formal employment and to improve their welfare.Footnote15 However, the law’s importance has been largely overshadowed by heated debate over its hasty development, lack of exposure to public consultation and the conflicting interests of businesses and labour unions. Nevertheless, the law will allow significant changes in the areas of business licensing, investment regulation and labour regulation.

In the following sections, we discuss those key areas. We also briefly discuss the establishment of an Indonesian sovereign wealth fund to stimulate national development, changes affecting MSMEs, and changes to environmental licensing.Footnote16 Table A1 in the online appendix presents a more detailed list of the amendments made under the law and its implementing regulations.

Business Licensing

Navigating Indonesia’s bureaucracy to obtain a business licence can be challenging. Businesses must jump through multiple hoops to meet the sometimes overlapping licensing requirements of line ministries at both the central and local government levels. In some instances, contradictions exist even within each government level, whether central or local. Unsurprisingly, inefficient bureaucracy has been ranked the second-most problematic factor for doing business in Indonesia, just behind corruption (WEF 2017).

The licensing provisions of the omnibus law are intended to simplify complicated licensing processes. They also mark a significant shift in the licensing paradigm by introducing a risk-based approach to issuing sectoral licences. Under this approach, only high-risk businesses will need to meet the rigorous requirements of obtaining a business licence. Medium-risk business will need only to register for a business identification number and to comply with certain business standards in order to obtain ‘standard certification’. Low-risk businesses will need only to register for an identification number. The risk assessment will be based on four main criteria: health, safety, environment and use of natural resources. The law also centralises various requirements for business operation, such as location permits, environmental licences and construction permits. In total, the law articulates amendments to 49 laws in order to move towards a risk-based approach to licensing.

Issues still surround the changes. One is the potential pushback from sectoral ministries and even local governments. Another is the potential difficulty in transitioning to a risk-based approach, as it will require incorporating the existing stock of licences into a tiered system, with reduced compliance costs for businesses applying to undertake mediumor low-risk activities. For example, 67 business activities are currently regulated in tourism, and all require licensing. In contrast, only eight activities will be considered high-risk according to the implementing regulation. Overall, from 2,280 evaluated licences, the government identified that 51% of licences cover activities with low–medium or medium risk. The remaining 49% cover activities with medium–high or high risk. This percentage is higher than expected. Jokowi aimed to have at least 25% of the existing business licences classified as being for activities of low or low–medium risk. This raises the question of whether the move to a risk-based approach will bring any meaningful changes in the long term.

Investment Regulation

The omnibus law marks significant deregulation of investment. Previously, investment was regulated based on a ‘negative investment list’, which specified the business fields that were either entirely closed or open with conditions for investment. The new law amends Law 25/2007 on Capital Investment, opening all but six sectors for local and foreign investment, while also preventing investment in specific activities related to national defence and security, which only the central government can undertake.Footnote17

For specific sectors, the law simplifies the investment restrictions previously covered by several laws. This includes the removal of a limit on foreign equity participation in horticulture; opening special economic zones to education and health services; allowing infrastructure and network sharing among telecommunication providers; and removing government authority to regulate prices of geothermal energy for direct use. However, the law still retains protections for MSMEs by specifying 89 areas of business that require partnership with MSMEs, reduced from 145 in the previous regulation. In addition, under a presidential regulation that supersedes the omnibus law, the number of sectors that are open with conditions—including caps on foreign ownership—has been reduced to 46 from 350 (Tani Citation2021).Footnote18 The presidential regulation also lists 245 ‘priority’ industries that can receive fiscal and non-fiscal incentives such as tax allowance and tax holidays, although the effectiveness of the policy remains unclear (see Siregar and Patunru Citation2021).

The omnibus law has the potential to boost investment by removing quantitative restrictions and other barriers to investment, including many prescriptive provisions regarding local content, sanctions and other sector-specific requirements. However, the new government regulation indicates that companies should prioritise domestically produced raw and supporting materials. It also specifies that the government can introduce export restrictions and help ease the import of raw materials to ensure availability.

Labour Market Regulation

The omnibus law has received much attention for amending and revoking provisions of the 2003 Manpower Law. The government argues that the changes address the declining competitiveness of the Indonesian labour force while maintaining some labour protection. The labour unions did not share its view; they have fiercely resisted changes that threaten their labour rights, even though the existing labour law may be counterproductive to creating post-crisis employment in the formal sector.

There are at least five notable changes to provisions under the labour law. The first is the change to the minimum wage formula, which will now be based on regional economic growth or regional inflation (whichever is higher) and will put a lower and upper cap on the minimum wage adjustment that is tied to the average per capita consumption in each region. This contrasts with the use of national economic growth and national inflation to formulate minimum wages, as previously required under Government Regulation 78/2015. The minimum wage will now be set at the provincial level while allowing for a district/municipality level adjustment for high-growth districts/municipalities.Footnote19 The sectoral minimum wage, however, has been abolished. Micro and small firms are exempted from paying the minimum wage; instead, they are required to pay their workers at least 50% of the provincial average of per capita consumption, with a lower cap of 25% above the provincial poverty line per month.

The second major change is that salaries can now be based on either the output of employees or the durations they work, with more flexible provisions on working periods. The implication is that part-time workers can be paid an hourly wage; previously, they had been paid either daily or monthly. The allowance of the hourly wage is one of the unions’ main concerns. They view this as a potential loophole for employers to avoid hiring workers under permanent contracts.

The third notable change is that outsourcing restrictions have been relaxed to allow businesses to outsource jobs directly related to their core activities. Before this change, firms could outsource only non-essential activities—such as security, catering and cleaning—that were not related to core business activities.

The fourth major change is the removal of a limit on the duration of fixed-term contracts. Previously, a fixed-term contract was limited to a maximum duration of three years. Employers were required to make the contract open-ended after that duration. Under the new law, a fixed-term worker whose contract is not continued is entitled to compensation equal to a month of salary for each year of their contract.

The fifth notable change regards severance pay for permanent employees. The basic formula for calculating severance pay remains unchanged. However, the law eliminates the additional payments required in redundancy dismissals and other specific types of dismissal, effectively reducing the maximum level of required severance pay from the equivalent of 32 months of salary to 19 months. This is still higher than what is offered by peer countries such as Malaysia (13 months), Thailand (13 months) and Vietnam (10 months) (ILO 2020). It will be difficult for the Indonesian labour force, particularly in the manufacturing sectors, to compete with Vietnam, whose maximum level of severance pay is about half Indonesia’s maximum. The law also introduces a basic unemployment benefit to complement severance payments. The benefit is essentially a contributory insurance delivered through Indonesia’s Social Security Agency for Health (BPJSTK) as a partial monthly salary for a maximum of six months for each unemployed employee.Footnote20 Even though this benefit seems to be an atonement for the changes to severance pay, it is welcome. Previously there was no formal unemployment benefit in Indonesia. The common practice for workers was to exploit a loophole that allowed them to access their old age fund from BPJSTK after being dismissed from employment. This undermined the sustainability of the agency’s pool of funds.

Some of the changes, such as the changes to the minimum wage formula and flexible output–duration wage scheme, may marginally improve efficiency. However, they introduce complexity that is likely disproportionate to the improvements. For example, the increasingly complex minimum wage formula could result in increased non-compliance with regulations. It may also create confusion at the local government level, since it must now make calculations that only BPS has made in the past (for example, the local government will need to compare price levels between the district/municipality and provincial levels). Other changes are long overdue, such as the reduction of severance pay entitlements, given the high cost of dismissing workers in Indonesia compared with peer countries (Manning Citation2010; World Bank Citation2010).

The relaxation of outsourcing restrictions and removal of the limitation period for fixed-term contracts will potentially have a profound impact, with clear winners and losers. Businesses will welcome these changes, which will allow firms more flexibility in managing and allocating resources. On the other hand, the pushback from labour unions is arguably understandable, since the changes remove some certainty provided by rigid employment contracts and restrictions on outsourcing. Other beneficiaries of these changes may actually be informal workers. Reductions in the costs of hiring and firing may create new jobs that will allow informal workers to move into the formal economy and gain more employment protection, even if this protection is weaker than was provided to formal sector employees under the previous labour law.

Sovereign Wealth Fund

Through the omnibus law, the government has established a sovereign wealth fund to boost investment. However, the design of the fund is far from traditional. The fund is not exclusively sovereign and allows private contributions. In addition, it has been established in a period of budgetary deficit, unlike other sovereign wealth funds, which are typically set up during periods of temporary revenue gain—for instance, during a resource boom. The purpose of these funds is usually to generate investment return from accumulated funds not needed for national expenses such as pensions. However, the new Indonesian fund acts more as a vehicle for tapping into non-resident funds to enable investment in longterm development projects, including the government’s strategic projects.Footnote21 This will enable the government to take better advantage of commercial investment opportunities. Such flexibility has been missing from the government’s investment vehicles. Notably, the mandate of PT Sarana Multi Infrastruktur (PT SMI), an SOE under the finance ministry, has been limited to financing and preparing infrastructure projects. Meanwhile, the mandate of Indonesia Investment Agency (PIP), a public service agency under the finance ministry, has shifted to focus on financing small–medium enterprises (SMEs), and the agency requires the minister’s approval to take action.

The government will inject about Rp 75 trillion (about $5.3 billion) of initial capital into the sovereign wealth fund. The implementing regulation (Government Regulation 74/2020) also enables the government to provide funding through SOEs, by issuing debt or capitalising its equity. The funding through those channels will close the gap of Rp 45 trillion, as the government has set aside Rp 15 trillion from both the 2020 and the 2021 budgets. The regulation covers the establishment of the managing body, Indonesia Investment Authority (INA). INA has a mandate to manage the investment directly or to appoint an investment manager. INA will also decide the master fund’s investment use by setting up new thematic funds or joining existing third-party funds—something that was not possible previously. The only condition is that investment in strategic sectors—such as the sectors providing drinking water or mining oil and gas—must have majority stakeholder control that is likely to comply with the existing law that strategic assets must come under the state’s management.

The sovereign wealth fund has been eagerly awaited by investors who hope it will create greater opportunity to invest in Indonesia. There is interest in the fund already from Singapore-based global investor GIC, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, Japan Bank for International Cooperation, the Canada Pension Fund, and the United States International Development Finance Corporation. The next challenge is to ensure strong and credible governance of the fund, with a clear investment target, and then to ensure the fund remains attractive to investors by ensuring good projects, with visible cash flow, are available to them for investment. If the fund is successful, it could alleviate some of the constraints on public sector capacity mentioned earlier.

Other Controversial Areas

Two controversial areas of the omnibus law involve MSMEs and the environment. With regard to MSMEs, the changes that the law introduces are marginal and lack strategic focus in providing an enabling environment for MSMEs to grow. More concerning, the law does not address the overlap and ineffectiveness among the programs that support MSMEs. Instead, the government is doubling down on its pre-existing direct support of MSMEs, with even more modalities, such as compulsory MSME partnerships for large businesses in certain sectors, coaching and development for MSMEs, and access to finance. The government will also bear the cost of halal certification for MSMEs, and the omnibus law makes it easier to establish cooperatives and provides a legal basis for following sharia business principles in cooperatives. It also introduces new criteria for defining MSMEs, such as capital, turnover, net worth, annual sales revenue and investment value, and it outlines various incentives for MSMEs.

While direct intervention might work on a case-by-case basis (Sandee, Isdijoso and Sulandjari Citation2002), a broad spectrum of firms fall into the MSMEs category. At one extreme, there are productive, growth-oriented firms that might benefit from direct support, even though they will grow eventually without government support. At the other end, there are less-productive, survivalist firms, mostly owned by sole proprietors. The latter group is sizable, reflecting the failure of the labour market to create employment for low-skilled workers, not thriving entrepreneurship (Tambunan Citation2008). The less-productive survivalist firms will benefit only marginally from the changes laid out in the law; a more efficient labour market that can create more jobs is more important to this group.

Another highlight is that the law states that both central and local governments shall prioritise MSME suppliers for at least 40% of government procurement. Compulsory partnership and procurement prioritisation have long been at best marginally useful policy tools for supporting genuine MSME growth. They also potentially hinder the procurement of large-scale infrastructure and other projects, which is counterproductive to the law’s goal of creating employment.

Another contested part of the law concerns the environment. There are several areas of contention, but the two most apparent regard environmental licensing and the weakening of a strict liability concept for environmental litigation. The law replaces the environmental licence with an environmental permit granted by a new institution and integrated within the business licence process. Several nongovernmental organisations fear that the new system could curb environmental protection and public access to environmental justice (Sembiring, Fatimah and Widyaningsih Citation2020a). Moreover, the weakening of strict liability is expected to make pursuing any environmental lawsuit harder (Syahrani and Tavares 2020).

Comments on the Omnibus Law

Contention has followed the omnibus law since its inception. The top-down approach to formulating the law, its complexity, and its hasty and non-transparent formulation have all raised questions about the quality and workability of the law (Sembiring, Fatimah and Widyaningsih Citation2020b). Poor public communication has also undermined public confidence in the law and what it is intended to achieve. Despite these challenges, we argue that the law provides necessary conditions for tackling various business environment problems. However, the law is not sufficient to achieve its main objective of improving investment quality and creating jobs. We argue that three main issues need consideration: the implementing regulations, effectiveness of implementation, and other reforms that can achieve the objective.

First, pushback from sectoral ministries and other stakeholders may create further compromise in the implementing regulations. As a follow-up to the law, sectoral ministries must formulate about 47 government regulations and 5 presidential regulations under the Coordinating Ministry of Economic Affairs. The government allows the public to access the drafts and provide input through a consultative team that consists of experts from universities and the private sector, and former officials. On 21 February 2021, 47 government regulations and 4 presidential regulations had been enacted by government. Owing to conflicting views and interests, discussions of the government regulations and presidential regulations have often been heated. Therefore, the deadline of delivering the implementing regulations within three months has been extended.

Second, the outcome, as ever, depends on implementation. Questions have been raised as to whether the law will be able to deliver on its promises. The Jokowi administration has initiated various reform efforts since the president’s first term in office. It launched 16 economic policy packages during 2016–18 that promised to overcome many of the issues the omnibus law attempts to address. However, they failed, largely because they covered only what they could without the government revising any laws. The omnibus law has avoided a similar failure by securing support from the Parliament and revising 78 laws. However, its effectiveness will depend on the government’s success in implementing the reforms within an inefficient bureaucracy. Hurdles may arise when developing the system to support the implementation of new business processes, such as in managing the transition process and disseminating information to the public. A key milestone in assessing the effectiveness of the law will be the implementation of the risk-based business licensing system at the Investment Coordinating Board (BKPM), as part of the one-stop service for licensing. This is scheduled to take place in July 2021.

Third, the omnibus law alone is not enough to sufficiently improve the investment climate. Several outstanding issues still need to be addressed to attract better investment and create jobs. Better labour skills and productivity, infrastructure and overall public service delivery are needed (see Aswicahyono and Hill Citation2016; Hidayat, Saputro and Maula Citation2019). The government also needs to address issues in the trade and financial sectors. The nexus between trade and investment policies is well known. Indonesia has been inward-looking for decades, and the pandemic seems to be justifying this stance, as protectionism increases around the world. Government reform to reverse this trend is needed and should be supported by sectoral policy reform (see Patunru and Rahardja Citation2015; WTO 2021). Financial sector reform is needed to enable better intermediation. Indonesia’s financial market is small and shallow, and the financial system is skewed towards banks with small pools of long-term institutional investors, such as pension funds and insurance. A deeper financial market with more long-term institutional investors could provide the finance needed for economic development and reduce reliance on foreign finance (see IMF 2018; Triggs, Kacaribu and Wang Citation2019). In addition, the government needs to improve the effectiveness of its fiscal spending and revenue collection. Its spending is less effective than that of other countries (Tang, Liu and Cheung Citation2010). The government also collects less revenue (its tax-to-GDP ratio is less than 10%) than the governments of most G20 countries, and it trails those of other emerging market economies. Reforms to address these problems are crucial to ensuring fiscal sustainability and market credibility.

Regardless, successful structural reform is possible in Indonesia. A successful structural transformation led to significant economic growth in Indonesia before the AFC (Hill Citation2000). The country has continued to deliver banking, fiscal and monetary reforms since the AFC (Basri Citation2018). The latter helped Indonesia to navigate the 2008 GFC with little difficulty (Basri and Hill Citation2011). However, this time a transformation will likely be more challenging, given the various public governance issues that were not apparent before the AFC, such as weak coordination, policy inconsistencies between central and local governments, and overlapping institutional responsibility (Hidayat, Saputro and Maula Citation2019). Whether Indonesia can grow stronger after the current crisis depends on the policy choices made now to manage the recovery and set a foundation for structural reform.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (199.4 KB)ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Adry Gracio for his excellent research assistance. We are grateful to Hal Hill, Blane Lewis, Ross McLeod and other reviewers associated with the journal for their valuable feedback. We also thank Chris Manning for his feedback and support throughout the development of this Survey.

Notes

1 As of early March, we started to see a decline in the number of daily new cases. The average number of daily new cases per one million people in February 2021 was 36.

2 Covid-19 handling committee (KPCPEN) presentation, 22 January 2021.

3 Ministry of Health presentation, 3 February 2021.

4 A simulation by the Faculty of Public Health at Universitas Indonesia indicates that the vaccination target is achievable if 930,000 injections are given per day by 31,000 vaccinators, between March 2021 and September 2022, subject to availability of the vaccine.

5 The survey wave was conducted from the last week of October to the second week of November, and involved 665 firms.

6 The August 2020 National Labour Force Survey included questions about the direct impact of Covid-19 on the employment status of workers.

7 Based on the traditional BPS definition of informal workers, ‘salaried workers’ constitute most of the formal labour market, while unpaid family workers are considered as informal.

8 Gentilini et al. (Citation2020) reports that by December 2020, Indonesia had expanded its cash transfer programs to cover 37 million beneficiaries in total. By contrast, Pakistan’s emergency cash program was reported to cover 95 million, the Philippines’ cash subsidy program to cover 83 million, and Brazil’s emergency financial aid program to cover 68 million.

9 Details are available in figure A1 in the online appendix.

10 For example, see https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/12/01/indonesia-to-spend-less-than-expected-of-covid-19-budget-by-year-end.html.

11 Data were accessed on 23 January 2021 from https://kur.ekon.go.id/ and http://www.depkop.go.id/data-umkm.

12 The estimate is from the impacts of SARS (2002–03), MERS (2012), Ebola (2014–15) and Zika (2015–16) episodes, the magnitudes of which were nowhere near that of the current pandemic.

13 PISA assesses the cumulative outcomes of education in reading, mathematics and science of children aged 15 (the age most children are still enrolled in formal education). For more information, see http://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisafaq/.

14 Under Law 2/2020, enacted in response to the pandemic, the 25% corporate tax rate was cut to 22% and will become 20% in 2022. Furthermore, corporate firms with at least 40% equity listed in the Indonesia stock exchange will benefit from an additional reduction of three percentage points.

15 Coordinating Minister of Economic Affairs presentation.

16 Many important issues in the omnibus law are not discussed here. We encourage others to discuss the law in detail in another article.

17 The six restricted sectors are narcotics cultivation and manufacturing; gambling; fisheries for certain species; coral exploitation; manufacturing of chemical weapons; and manufacturing of industrial chemicals and ozone-depleting substances.

18 The elimination of the negative list could create problems, since the list has been providing transparency for foreign investors since its introduction in 2007 (OECD 2020).

19 The implementing regulation draft stipulates that only districts/municipalities with higher economic growth than the provincial average for three consecutive years are allowed to set a local minimum wage. The local minimum wage adjustments compared with the provincial minimum wage are determined by the difference in the price level, existing employment rate and median wage relative to the provincial level.

20 The benefit is set at 45% of salary for the first three months and 25% of salary for the remaining three months. The maximum salary cap for the benefits is set at Rp 5 million.

21 The government introduced a list of national strategic projects in 2016. They included the Jakarta Mass Rapid Transit system, Trans–Sumatra Toll Road and Palapa Ring broadband project. In the latest amendment of the list (in Presidential Regulation 109/2020), there are 201 projects and 10 programs, with a total investment of more than Rp 4,800 trillion, to be completed by 2024. From 2016 to 2020, the government completed 103 projects, worth about Rp 600 trillion.

REFERENCES

- Alhamidi, Rifat. 2021. ‘Soal Hoaks Vaksin Covid-19, Begini Tanggapan Komisi IX DPR’ [Regarding the Covid-19 vaccine hoax, here is the DPR’s ninth commission response]. Detik, 22 January. https://news.detik.com/berita-jawa-barat/d-5344471/soal-hoaks-vaksin-covid-19-begini-tanggapan-komisi-ix-dpr

- Asmara, Chandra Gian. 2021. ‘Jokowi Mau Vaksinasi 1 Juta Orang per Hari, Mungkin Nggak Ya?’ [Jokowi wants to vaccinate one million people per day; maybe not, yeah?]. CNBC Indonesia, 7 February. https://www.cnbcindonesia.com/tech/20210207103759-37-221592/jokowi-mau-vaksinasi-1-juta-orang-per-hari-mungkin-nggak-ya

- Aswicahyono, Haryo and Hal Hill. 2016. ‘Is Indonesia Trapped in the Middle?’. In Asia and the Middle-Income Trap, edited by Francis E. Hutchinson and Sanchita Basu Das, 101–25. London: Routledge.

- Aswicahyono, Haryo, Hal Hill and Dionisius Narjoko. 2010. ‘Industrialisation after a Deep Economic Crisis: Indonesia’. Journal of Development Studies 46 (6): 1084–108. doi: 10.1080/00220380903318087

- Basri, M. Chatib. 2018. ‘Twenty Years after the Asian Financial Crisis’. In Realizing Indonesia’s Economic Potential, edited by Luis E. Breuer, Jaime Guajardo and Tidiane Kinda, 21–45. Washington, DC: IMF.

- Basri, M. Chatib and Hal Hill. 2011. ‘Indonesian Growth Dynamics’. Asian Economic Policy Review 6 (1): 90–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-3131.2011.01184.x

- BI (Bank Indonesia). 2020. Survei Konsumen: Desember 2020 [Consumer survey: December 2020]. Jakarta: BI.

- Booth, Anne, Raden Muhammad Purnagunawan and Elan Satriawan. 2019. ‘Towards a Healthy Indonesia?’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 55 (2): 133–55. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2019.1639509

- BPS. 2021. Indikator Ekonomi Desember 2020 [Economic indicators December 2020]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2021/02/26/b2c604c7e97325b19f882778/indika-tor-ekonomi-desember-2020.html

- Couper, Elena and Sienna Curnow. 2021. ‘Indonesia Adopts New Strategies to Curb Covid-19 Death Toll’. Jakarta Globe, 23 January. https://jakartaglobe.id/news/indonesia-adopts-new-strategies-to-curb-covid19-death-toll

- Das, Anu. 2020. ‘Commodities 2021: Tight Production, Demand Expectations to Support Asian Palm Oil Prices’. S&P Global Platts, 31 December. https://www.spglobal.com/platts/en/market-insights/latest-news/agriculture/123120-commodities-2021-tight-pro-duction-demand-expectations-to-support-asian-palm-oil-prices

- de Mooij, Ruud, Suahasil Nazara and Juan Toro. 2018. ‘Implementing a Medium-Term Revenue Strategy’. In Realizing Indonesia’s Economic Potential, edited by Luis E. Breuer, Jaime Guajardo and Tidiane Kinda, 109–40. Washington, DC: IMF.

- Djalante, Riyanti, Jonatan Lassa, Davin Setiamarga, Aruminingsih Sudjatma, Mochamad Indrawan, Budi Haryanto, Choirul Mahfud, et al. 2020. ‘Review and Analysis of Current Responses to Covid-19 in Indonesia: Period of January to March 2020’. Progress in Disaster Science 6: 100091. doi: 10.1016/j.pdisas.2020.100091

- Elyazar, Iqbal, Henry Surendra, Lenny Ekawati, Bimandra Djaafara, Ahmad Nurhasim, Ahmad Arif, Irma Hidayana, et al. 2020. ‘Excess Mortality during the First Ten Months of Covid-19 Epidemic at Jakarta, Indonesia’. Preprint, submitted to medRxiv, 14 December.

- Fallon, Peter R. and Robert E. B. Lucas. 2002. ‘The Impact of Financial Crises on Labor Markets, Household Incomes, and Poverty: A Review of Evidence’. World Bank Research Observer 17 (1): 21–45. doi: 10.1093/wbro/17.1.21

- Fauzie, Yuli Yanna. 2021. ‘Siap-Siap Sayonara Vaksin Gratis Buat Orang Berduit’ [Say goodbye to free vaccine for rich people]. CNN Indonesia, 21 January. https://www.cnnindonesia.com/ekonomi/20210121134811-92-596665/siap-siap-sayonara-vaksin-gratis-buat-orang-berduit

- Gentilini, Ugo, Mohamed Almenfi, Ian Orton and Pamela Dale. 2020. ‘Social Protection and Jobs Responses to Covid-19: A Real-Time Review of Country Measures’. Living paper, version 14, 11 December, Washington, DC, World Bank.

- Hidayat, M. Firman, Adhi Saputro and Bertha Maula. 2019. Indonesia Growth Diagnostics: Strategic Priority to Boost Economic Growth. Jakarta: National Development Planning Agency (Bappenas).

- Hill, Hal. 2000. ‘Indonesia: The Strange and Sudden Death of a Tiger Economy’. Oxford Development Studies 28 (2): 117–39. doi: 10.1080/713688310

- Hugo, Graeme. 2000. ‘The Impact of the Crisis on Internal Population Movement in Indonesia’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (2): 115–38. doi: 10.1080/00074910012331338913

- ILO (International Labour Organization). 2020. ‘Redundancy and Severance Pay’. EPLex database. Accessed 11 February. https://eplex.ilo.org/redundancy-and-severance-pay/

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2018. Republic of Indonesia Financial Sector Assessment Program. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- IMF (International Monetary Fund). 2020. World Economic Outlook: A Long and Difficult Ascent: 2020 Oct. Washington, DC: IMF.

- Ing, Lili Yan and Fukunari Kimura. 2017. Production Networks in Southeast Asia. London: Routledge.

- Jakarta Post. 2020. ‘Covid-19: Health of 25 Million Toddlers at Risk as Posyandu Disrupted by Pandemic’. Jakarta Post, 2 October. https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2020/10/01/covid-19-health-of-25-million-toddlers-at-risk-as-posyandu-disrupted-by-pandemic.html

- Karina, Nadia. 2020. ‘Strengthening Indonesia’s Social Protection in the Covid-19 Era: Strategy and Lessons from Evidence’. J-PAL, 20 November. https://www.povertyactionlab.org/blog/11-20-20/strengthening-indonesias-social-protection-covid-19-era-strategy-and-lessons-evidence

- Manning, Chris. 2000. ‘Labour Market Adjustment to Indonesia’s Economic Crisis: Context, Trends and Implications’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (1): 105–36. doi: 10.1080/00074910012331337803

- Manning, Chris. 2010. ‘Employment Policy and Labour Market in Indonesia’. International Labour Organization (ILO) presentation on trade, Jakarta.

- Mazzucato, Mariana and Rainer Kattel. 2020. ‘Covid-19 and Public-Sector Capacity’. Oxford Review of Economic Policy 36 (S1): S256–69. doi: 10.1093/oxrep/graa031

- Ministry of Health, NITAG (National Immunization Technical Advisory Group), UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund) and WHO (World Health Organization). 2020. ‘Covid-19 Vaccine Acceptance Survey in Indonesia’. https://covid19.go.id/storage/app/media/Hasil%20Kajian/2020/November/vaccine-acceptance-survey-en-12-11-2020final.pdf

- Mirchandani, Manisha. 2020. ‘How Did Vietnam and Cambodia Contain COVID-19 With Few Resources?’. Brink, 27 December. https://www.brinknews.com/how-did-vietnam-and-cambodia-contain-covid-19-with-few-resources/

- Nguyen, Phuong. 2020. ‘Vietnam’s 2020 Economic Growth Slips to 30-Year Low Due to Covid-19’. Reuters, 27 December. https://www.reuters.com/article/us-vietnam-economy-gdp-idUSKBN29107M

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2020. OECD Investment Policy Reviews: Indonesia 2020. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Patunru, Arianto and Sjamsu Rahardja. 2015. ‘Trade Protectionism in Indonesia: Bad Times and Bad Policy’. Lowy Institute, 30 July.

- Russel, Clyde. 2021. ‘Column: China’s Ban on Australian Coal Forces Trade Flows to Realign: Russell’. Reuters, 12 January. https://www.reuters.com/article/column-russell-coal-asia/column-chinas-ban-on-australian-coal-forces-trade-flows-to-realign-russell-idINL-1N2JN0B4

- Sandee, Henry, Brahmantio Isdijoso and Sri Sulandjari. 2002. SME Clusters in Indonesia: An Analysis of Growth Dynamics and Employment Conditions. Jakarta: International Labour Organization (ILO).

- Sembiring, Raynaldo, Isna Fatimah and Grita Anindarini Widyaningsih. 2020a. ‘Degradation of Environmental Protection and Management Instruments under Draft Bill on Job Creation’. Policy paper, Indonesia Center for Environmental Law (ICEL), Jakarta.

- Sembiring, Raynaldo, Isna Fatimah and Grita Anindarini Widyaningsih. 2020b. ‘Indonesia’s Omnibus Bill on Job Creation: A Setback for Environmental Law?’. Chinese Journal of Environmental Law 4 (1): 97–109. doi: 10.1163/24686042-12340051

- Setiati, Siti and Muhammad K. Azwar. 2020. ‘Dilemma of Prioritising Health and the Economy during Covid-19 Pandemic in Indonesia’. Acta Medica Indonesiana 52 (3): 196–8.

- Siregar, Rotua and Arianto Patunru. 2021. ‘The Impact of Tax Incentives on Foreign Direct Investment in Indonesia’. Journal of Accounting Auditing and Business 4 (1): 66–80. doi: 10.24198/jaab.v4i1.30629

- Sparrow, Robert, Teguh Dartanto and Renate Hartwig. 2020. ‘Indonesia under the New Normal: Challenges and the Way Ahead’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 56 (3): 269–99. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2020.1854079

- Sucahya, Purwa Kurnia. 2020. ‘Barriers to Covid-19 RT-PCR Testing in Indonesia: A Health Policy Perspective’. Journal of Indonesian Health Policy and Administration 5 (2): 36–42. doi: 10.7454/ihpa.v5i2.3888

- Syahrani and Muhammad Alfitras Tavares. 2020. ‘Nasib Target Emisi Indonesia: Pelemahan Instrumen Lingkungan Hidup di Era Pemulihan Ekonomi Nasional’ [The fate of Indonesia’s emission target: Impairment of environmental instruments in the national economic recovery era]. Jurnal Hukum Lingkungan Indonesia 7 (1): 1–27. doi: 10.38011/jhli.v7i1.212

- Tambunan, Tulus. 2008. ‘SMEs Development in Indonesia: Do Economic Growth and Government Support Matter?’. International Journal of Asia-Pacific Studies 4 (2): 111–33.

- Tang, Hsiao Chink, Philip Liu and Eddie C. Cheung. 2010. ‘Changing Impact of Fiscal Policy on Selected ASEAN Countries’. Working paper, Asian Development Bank.

- Tani, Shotaro. 2021. ‘Indonesia to Offer Investment Incentives for “Priority” Sectors’. Nikkei Asia, 25 February. https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Indonesia-to-offer-investment-incentives-for-priority-sectors

- Thomas, Vincent Fabian. 2021. ‘Saat Pemerintah Bongkar Pasang PEN 2021 karena Terlampau Optimistis’ [When the government keeps modifying the 2021 PEN because it is too optimistic]. Tirto ID, 7 February. https://tirto.id/saat-pemerintah-bongkar-pasang-pen-2021-karena-terlampau-optimistis-f92a

- Tohari, Achmad, Christopher Parsons and Anu Rammohan. 2019. ‘Targeting Poverty under Complementarities: Evidence from Indonesia’s Unified Targeting System’. Journal of Development Economics 140: 127–44. doi: 10.1016/j.jdeveco.2019.06.002

- Triggs, Adam, Febrio Kacaribu and Jiao Wang. 2019. ‘Risks, Resilience, and Reforms: Indonesia’s Financial System in 2019’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 55 (1): 1–27. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2019.1592644

- Vorisek, Dana. 2020. ‘Covid-19 Will Leave Lasting Economic Scars around the World’. World Bank Blogs, 8 June. https://blogs.worldbank.org/voices/covid-19-will-leave-lasting-economic-scars-around-world

- WEF (World Economic Forum). 2017. The Global Competitiveness Report: 2017–2018. Geneva: WEF.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2020. WHO SAGE Values Framework for the Allocation and Prioritization of Covid-19 Vaccination: 14 September 2020. Geneva: WHO.

- World Bank. 2010. Indonesia Jobs Report: Towards Better Jobs and Security for All. Jakarta: World Bank.

- World Bank. 2020. Covid-19 Impact on Firms in Indonesia. Jakarta: World Bank. http://pubdocs.worldbank.org/en/579271610012405014/COVID19-Impacts-on-Indonesia-Firms.pdf

- WTO (World Trade Organization). 2021. Trade Policy Review of Indonesia: Secretariat Report.

- WTO. https://www.wto.org/english/tratop_e/tpr_e/tp501_e.htm

- Wulandhari, Retno. 2021. ‘Unilever Indonesia Siap Distribusikan Vaksin Covid-19’ [Unilever Indonesia is ready to distribute Covid-19 vaccine]. Republika, 19 January. https://republika.co.id/berita/qn5wjn383/unilever-indonesia-siap-distribusikan-vaksin-covid19

- Yarrow, Noah, Eema Masood and Rythia Afkar. 2020. Estimates of Covid-19 Impacts on Learning and Earning in Indonesia: How to Turn the Tide. Jakarta: World Bank.