Abstract

This Survey discusses the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the livelihood of Indonesian women. The pandemic has disproportionately affected women around the world, including in Indonesia, owing to gender inequalities at work and at home. Women bear most of the burden of unpaid domestic work and care for families. The pandemic has also forced adjustments in labour utilisation, and the movement of workers from formal to informal sectors. However, it has created new opportunities, including for micro, small and medium enterprises that harness digitalisation, although the sustainability of these opportunities for women is still too early to assess, owing to the persistent gender divide in Indonesia’s digital economy. The possible long-term mental health effects of the pandemic are also something to watch.

Survei ini membahas dampak pandemi Covid-19 pada penghidupan perempuan Indonesia. Secara tidak proporsional, pandemi ini telah mempengaruhi perempuan di seluruh dunia, termasuk di Indonesia oleh karena adanya ketimpangan gender di tempat kerja dan di rumah. Umumnya perempuan bertugas menanggung beban pekerjaan rumah tangga tak berbayar serta menjaga anggota keluarga di rumah. Pandemi juga telah memaksa terjadinya penyesuaian pada utilisasi tenaga kerja dan perpindahan dari sektor formal ke sektor informal dalam pasar tenaga kerja. Namun demikian, ia juga telah menciptakan berbagai peluang baru, termasuk di sektor usaha mikro, kecil, dan menengah yang memanfaatkan digitalisasi. Masih terlalu dini untuk menelaah keberlanjutan peluang-peluang tersebut bagi perempuan, dikarenakan adanya pemisahan gender secara persisten pada perekonomian Indonesia yang berbasis digital. Selain itu, kemungkinan dampak jangka panjang pandemi pada kesehatan mental juga harus diwaspadai.

INTRODUCTION

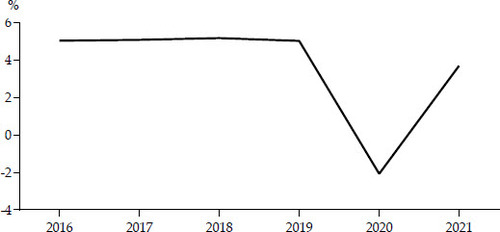

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a multifaceted impact. Initially causing a health shock, the effects of the pandemic quickly evolved to produce an economic shock. As in the global economy, economic growth in Indonesia plunged in 2020, by 2.1%—the worst decline since the 2007–08 global financial crisis. Indonesia started to recover from the downturn in the second quarter of 2021. However, as in other countries in the region, the recovery was then threatened by the Delta and Omicron variants of the virus. Still, in 2021 Indonesia’s economic growth rate rebounded to 3.7%, although real GDP growth per capita was lower, at 2.9%, than it had been before the pandemic (3.9%), in 2019 (ADB 2022a). Further, the economy is projected to grow by about 5% in 2022 and 2023, although this looks increasingly optimistic in light of recent international growth projections.

The pandemic has affected men and women differently. Unlike in previous downturns, women have been more affected on multiple fronts. Women are more vulnerable to the effects of the pandemic because of structural gender inequalities (Madgavkar et al. Citation2020). As in other parts of the world, every aspect of the pandemic has gender dimensions in Indonesia.

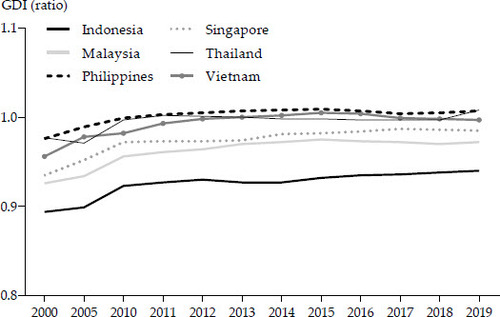

presents Indonesia’s performance in the Gender Development Index (GDI) of the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) during 2000–2019.Footnote1 The GDI is a measure of cross-country gender inequality, calculated as the ratio of female to male values in the Human Development Index (HDI), where a GDI ratio closer to 1 represents being closer to gender parity.

FIGURE 1 Gender Development Index: Indonesia and Selected Asian Countries, 2000–2019

Source: UNDP (2020).

shows that Indonesia’s GDI values improved during 2000–2019, although they were still well below those of Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. How the pandemic has affected gender inequality in Indonesia relative to inequality in other nations was unclear at the time of writing, as the post-pandemic GDI data had not been released. Still, it is essential to look at the pandemic through a gender lens, as the long-term impact of the pandemic on women is likely to exacerbate gender inequality, which will cost the economy (Madgavkar et al. Citation2020). Closing the gender gap can increase countries’ economic growth, competitiveness and readiness for the future (WEF 2020). Understanding women’s increasing role in the economy and how women juggle unpaid care is also crucial. Prior to the crisis, the International Labour Organization (ILO 2018), using data on 53 countries, estimated that unpaid care work is worth 9% of global GDP, representing a total of $11 trillion in purchasing power parity.

Understanding the roles women have played during the pandemic is important given women’s typically onerous roles in families and households. The mobility restrictions experienced during the pandemic disrupted both supply and demand in the economy, which also affected women. This lowered income, owing to a loss of jobs and business, and a reduction of working hours and wages. The United Nations Children’s Fund, in collaboration with other organisations (UNICEF et al. 2021), highlighted the unequal impact of the pandemic across households with different demographics and socio-economic backgrounds. The organisations showed that households are more vulnerable if they have large families, live in urban areas, have a female household head or have persons with disability. Further, as Timmer (Citation2022) highlighted, the current disruption in the global food supply chain puts future prosperity at risk, as the food expenditure of families and households increases. This increase has also been accompanied by greater spending on areas such as health services and medicines, and communication and information for remote school and work. The combination of a reduction in household income and the increases in expenditure has contributed to a rise in poverty.

This Survey discusses the impacts of the pandemic on Indonesian women. It investigates and analyses the immediate and medium-term impacts on women at home and at work, and the long-term implications for women. Not only does it discuss the challenges, but it also explores the opportunities created during the response to the pandemic. Understanding these two issues is crucial, as women matter for the recovery of the economy. The Survey starts by discussing macroeconomic development. It then focuses in on the triple-burden role of women during the pandemic, in the productive, reproductive and community spheres. The Survey goes on to look at women at home and at work. It then discusses some long-term implications of the pandemic for women, and concludes by drawing attention to several policy implications.

MACROECONOMIC DEVELOPMENTS

Indonesia’s Economic Growth

During 2016–19, Indonesia’s economy grew by about 5% annually (). In 2020, the economic growth rate slumped to –2.1%, following contractions in year-on-year economic growth in the last three quarters of the year. These contractions followed disruptions in both supply and demand triggered by public mobility restrictions.Footnote2 Nevertheless, by the second quarter of 2021, economic growth had returned to pre-pandemic growth levels (), although we define the recovery as beginning in the first quarter of 2022, following three consecutive quarters of positive economic growth.

FIGURE 2 Economic Growth, 2016–21

Source: CEIC (Citation2022).

Table 1. Economic Growth, by Expenditure and Sector, 2016–22 (%)

In 2021, Indonesia’s annual growth rate (3.7%) was above the average for Southeast Asia (2.9%) (World Bank Citation2022c; ADB 2022a).

In Indonesia in 2020, expenditure grew only in the government sector. shows that expenditure declined in 2020 for households by 2.6%, for investment by 5%, for exports by 8.1% and for imports by 16.7%. However, in the last four quarters shown in the table, Indonesia’s exports and imports saw impressive growth, following global economic recovery that led to increases in world demand and commodity prices. In 2021, the economic recovery was supported by expenditure growth in all sectors, while the expenditure of households increased by 2%, private sector investment by 3.8% and government by 4.2%.

Data show that the effects of the pandemic and the ability to recover from them have varied across sectors. Information and communication was the only sector that grew significantly during the first year of the pandemic (2020), by 10.6%, amid mobility restrictions that increased demand for remote-communication technology. This growth rate was greater than the levels seen before the pandemic (2016–19), but it fell to 6.8% in 2021. The agriculture, forestry and fishing sector also grew during the pandemic, but by less than it did in the pre-pandemic period. The two sectors hit hardest by the onset of the pandemic were transport and storage, and accommodation and restaurants, which contracted by more than 15% and 10%, respectively, in 2020. These sectors started to recover in 2021, but they grew by less than they did before the pandemic. Manufacturing and construction also contracted in 2020 and began to recover in 2021 but with lower growth than during the pre-pandemic period. The large wholesale and retail trade sector recovered and returned to a pre-pandemic growth level in 2021.

Overall economic recovery continued during the first quarter of 2022; this is predicted to continue throughout 2022, with a growth rate of close to 5%, according to Bank Indonesia, the Indonesian Ministry of Finance and the World Bank.

Macroeconomic Conditions

Trade and the Current Account in Indonesia

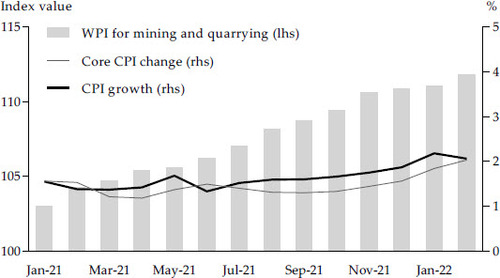

As highlighted in several earlier BIES Surveys, international trade was disrupted particularly in the first year of the crisis. The free-on-board values of exports and imports declined by 3% and 18% (). The disruption of supply and demand during the pandemic was likely the main factor behind the reduction in import values in 2020. However, the increase in commodity prices had a positive effect on trade in 2021. The value of the wholesale price index for mining and quarrying commodities has gradually increased, particularly since the beginning of 2021, as global economic recovery began. The value was 103 at the beginning of 2021 and increased to 107 in July 2021 and 111 in December 2021 (). The strong export performance relied heavily on the export of mining commodities such as coal and gas, which contributed 80% of the value of mining exports, and the export of commodities such as palm oil, which contributed 15% of the value of manufacturing-goods exports.

FIGURE 3 Consumer Price Index and Wholesale Price Index for Mining and Quarrying Commodities, 2021–22

Source: CEIC (Citation2022).

Note: The core consumer price index (CPI) change excludes transitory or temporary price volatility and represents the long-run trend in the price level. WPI stands for wholesale price index (base: 2018 = 100).

Table 2. Indonesia’s Balance of Payments, 2018–21 ($ million)

Indonesia had current account deficits in 2018 and 2019 of more than $30 million (). In 2021, surpluses were driven by both booming commodity export prices and contractions in imports of services. In 2020, the current account deficit, $4.5 million, was less than in 2018–19, partly owing to a reduction in imports. In the third quarter of 2021, more than a year after the pandemic began, Indonesia produced a current account surplus. The country continued to produce surpluses through early 2022 (see appendix ).

Commodity Price Rises, Inflationary Pressures and Implications for the Budget

Along with economic recovery, Indonesia and countries around the globe have been facing greater uncertainty and supply disruption. This is largely because of the war between Russia and Ukraine, financial tightening policy in the United States, and the economic troubles of China, which are related to the Chinese construction sector’s high levels of debt and the country’s zero Covid-19 policy. These factors contributed to increases in the prices of mining and quarrying commodities, as shown in . Increases in the prices of energy commodities in particular have already begun to put considerable pressure on the state budget, given the state’s fuel subsidy. In February 2022, the realised budget allocation for the fuel subsidy reached Rp 22 trillion, or about 10% of the total annual budget of Rp 207 trillion. The realised budget represented a 75% increase, compared with the level in February 2021 (Ministry of Finance Citation2022). Meanwhile, the state budget for 2022 assumed an Indonesian crude (oil) price (ICP) of $63 per barrel. In March 2022, however, the ICP reached $96 per barrel (Negara Citation2022).

In 2022, the ICP is predicted to rise further to $100 per barrel, increasing the budgetary burden of the fuel subsidy by $12 billion, or to more than 83% of the government’s 2022 subsidy target. The rises are expected to increase the fuel subsidy to 2% of GDP this year, although the government allocation for the subsidy is just 0.4% of GDP (Thomas Citation2022). Nonetheless, increases in the ICP also benefit the state budget through rising income-tax revenue from the oil and gas sector. For February 2022, this revenue had increased by 163% year on year. Taxes from the oil and gas sector contributed about Rp 14 trillion, or nearly one-third, of the 2022 revenue target (Ministry of Finance Citation2022).

shows that the consumer price index (CPI) gradually increased from the middle of 2021, following mild inflation and deflation in 2020 owing to a lack of demand at the start of the pandemic. The recent rises in the CPI indicate increases in the cost of living. The cost pressures were evident at the beginning of 2022, although they eased slightly in February. The increases in commodity prices created shortages in palm oil products in the domestic market, which led to increases in product prices. From November 2021, the government introduced a series of policies on palm oil and its products, including subsidies, export permits, a levy, domestic market obligations, retail price caps and export bans. The bans in particular disrupted shipment and endangered income from exports. They may have also disrupted investment, owing to an increase in uncertainty surrounding regulation in Indonesia (Christina 2022; Jadhav Citation2022; Reuters 2022).

Nevertheless, as noted, Indonesia’s economy is predicted to grow in 2022, given the country’s resilient macroeconomic performance in recent years (). Indonesia’s inflation rate is also expected to be lower than the rates of Malaysia, the Philippines and Thailand in 2022. In 2021, the fiscal deficit in Indonesia was 4.6% of GDP, which was higher than the deficits of Malaysia and Vietnam but much lower than those of the Philippines and Thailand. The optimism for Indonesia’s economic recovery is maintained partly because the country has a large domestic market; a relatively low proportion of goods and services exports, valued at about 19% of GDP in 2015–19; and external financing needs of 9% of GDP. Indonesia is also perceived to still have room for macroeconomic policy adjustment. General government debt increased to 41% of GDP in 2021—a 12 percentage-point increase compared with the average rate of 2015–19—but it was still manageable. In addition, interest rates were still comparatively low and the reserve buffer for foreign exchange appears to be under control (World Bank 2020c).Footnote3

Table 3. Macroeconomic Performance in Southeast Asian Countries and China

Implications of Macroeconomic Conditions for Women in Indonesia

Understanding the growth experience of different sectors during the pandemic is important for understanding the pandemic’s impact on women. As shown in , the three sectors affected the most in 2020 by the pandemic were transport and storage, contracting by 15.1%; accommodation and restaurants, by 10.3%; and wholesale and retail trade, by 3.8%. The latter two industries were major areas of employment for women, while the transport sector employs mainly men. Women make up just 39% of the global workforce. Yet they have been over-represented in three of the four industries most affected during the pandemic: accommodation and food services (54%); wholesale and retail trade (43%); and services such as arts, recreation and public administration (46%) (Wood 2020). In Indonesia, according to survey data from the past three years, women have been employed mostly in agriculture, forestry and fishing; wholesale and retail trade; manufacturing; and accommodation and restaurants. Previous studies show that unfavourable macroeconomic conditions during the pandemic have affected female labour-force participation and employment (Dang and Nguyen Citation2021; Alon et al. Citation2020). However, as shown in , all the sectors that had contracted the most started to recover in 2021. These include wholesale and retail trade and accommodation and restaurants, where Indonesian female employment is concentrated.

THE CHANGING ROLE OF WOMEN

Social Norms and the Triple Burden for Women in Indonesia

Social and gender norms still influence the division of gender roles in the household and in the employment of women (Jayachandran Citation2020). Social norms at home may progress so that men share the housework, but this progression may not change societal behaviour towards women’s employment decisions. Social norms affecting the patterns of female labour-force participation include gender-role attitudes towards occupational choices, the types of employment that women can undertake and the balance between work and family considerations (Somech and Drach-Zahavy Citation2016).Footnote4

Social and gender norms are also reflected in laws and regulations, as women in Indonesia still do not have full legal equality. shows selected values of the 2022 Women, Business and the Law index, which measures the global progress made towards gender equality during 2020–21 for 190 economies, including Indonesia. The World Bank index does this by identifying laws and regulations that restrict women’s economic participation, using eight indicators: mobility, workplace, pay, marriage, parenthood, entrepreneurship, assets and pension (World Bank 2022b).Footnote5 In the index, Indonesia scored 64.4, which is lower than the global average of 76.5. It is also lower than the scores of other Southeast Asian countries, except Malaysia. Indonesia’s score reflects, for example, that sons and daughters still do not have equal rights to inherit assets from their parents, that male and female surviving spouses do not have equal rights to inherit assets from their spouses and that periods of absence due to childcare are not accounted for in pension benefits. Further, women in Indonesia are entitled to only 13 weeks of paid maternity leave; this is still lower than the International Labour Organization’s recommendation of at least 18 weeks.

Table 4. Women, Business and the Law Index: Indonesia and Selected Countries, 2020–21

Nevertheless, in the more cosmopolitan parts of Indonesia, such as Jakarta, attitudes towards gender roles are becoming more egalitarian, particularly among non-Muslims and young people with educated parents (Utomo Citation2016). This is in line with the findings of Cameron, Contreras Suarez and Rowell (2019) that female labour-force participation in Indonesia is increasing, particularly in urban areas, as social norms change.

As noted, the literature identifies the triple burden of women (particularly married women) to perform productive work, reproductive work and community-managing work (Moser Citation1993). Social norms influence the practice of women in these three roles in Indonesia. The productive work includes labour that is economically, politically and socially visible and able to be monetised. Meanwhile, the reproductive work is wide-ranging and includes childbearing, caring for family and the elderly and doing domestic chores such as cleaning, washing and cooking. Further, married women are usually responsible for community contributions, such as neighbourhood activities to improve community resources. Unlike productive work, reproductive work is often ‘invisible’ and mostly unable to be monetised (Delaney and Macdonald Citation2018). The literature also acknowledges unequal burden sharing between men and women in the reproductive and community spheres (Lee, Yoo and Hong Citation2019; Nawaz and McLaren Citation2019). Previous studies have discussed mainly the impacts of the pandemic in the reproductive and productive spheres for women, but there is limited research on the impacts in the community sphere.

WOMEN AT HOME

The Pandemic and the Reproductive Sphere: The Burden of Unpaid Care

Several studies conducted during the pandemic identify a global increase in the time women must allocate to reproductive tasks (Collins et al. Citation2021; ILO and OECD Citation2020; UN Women Citation2020c). UN Women (Citation2020b) data show that, in the Asia Pacific region during the pandemic, the traditional views of gender roles held that women should be responsible for unpaid domestic work and unpaid caregiving. As shown in , women do shoulder the greater burden of domestic work in the region, cleaning daily almost four times as much as men do, for example. The overall gender disparity in domestic work is higher in the Asia Pacific region than in other world regions (UN Women (Citation2020b). However, UN Women (Citation2020c) also found that, globally, girls and women do about three times more unpaid care work on average than men do, a burden likely to increase during prolonged lockdowns and school closures.

Table 5. Unpaid Care by Gender in the Asia Pacific Region, 2020

From August 2020, after school children had been learning remotely for nearly six months, schools were permitted to start opening for conventional face-to-face classes if they had complied with government requirements and gained local government permission. Although schools were permitted to reopen for conventional learning, particularly those in green zones (those with the lowest levels of Covid-19), about 59% of schools continued to offer remote learning rather than conventional learning (Ministry of Education and Culture Citation2020). Owing to the steep increase in cases of the Omicron variant in 2022, schools in areas with high levels of cases returned to remote learning.

In most Asian countries, imposing strict lockdowns, school closures and restrictions on mobility increases the significant burden on married women to complete both their daily productive and reproductive tasks. The burden is particularly heavy for single parents. Furthermore, mainly mothers support their children’s remote learning in almost 72% of households, whereas mainly fathers do so in less than 24% of households (UNICEF et al. 2021). A World Bank survey covering late May to early June 2020 found that, in about 18% of households, an adult member had to sacrifice productive work to support their children because schools were closed; in 66% of these households, the member was the mother (World Bank 2022a). Moreover, almost 76% of married women in male-headed households said they do more chores than their spouse (UNICEF et al. 2021).

WOMEN AT WORK

The Pandemic and Production: The Labour Market Adjustment for Women

The triple burden experienced by women, particularly the burden of reproductive work, creates significant barriers to women’s participation in the labour market. Moreover, women were more likely than men to exit the labour market during the pandemic. The ILO (2021) estimated that, globally, women lost 64 million jobs in 2020, a 5% employment loss, compared with a 3.9% loss for men. The burden of caring for households during the pandemic also affects the likelihood that women will remain in the labour market.

Thus, the following section discusses changes to the participation of women in the labour market during the pandemic, while acknowledging that some issues existed well before the pandemic. Female employment in Indonesia has long endured structural labour market problems, such as the gender-wage gap, structural unemployment and the concentration of female employment in the informal sector. Nevertheless, we show that the pandemic has worsened several areas of inequality for women.

Labour Utilisation: Participation Rates, Unemployment and Employment

Participation Rates and Unemployment

‘Regular’ recessions such as the global financial crisis of 2008–09 typically affect the employment of men more than the employment of women, as men more commonly work in sectors such as manufacturing and construction, which are vulnerable to the effects of such downturns. However, the Covid-19 pandemic appears to have had a greater effect on the employment opportunities of women than men. One explanation for this is that the employment of women is concentrated in the sectors that were negatively affected the most during the pandemic, such as retail, accommodation and food services, tourism, arts and entertainment, and other personal services (Alon et al. Citation2020).

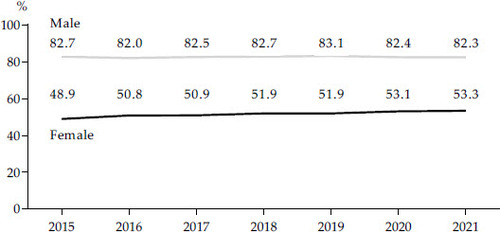

The negative effect of the pandemic on women is not immediately obvious in the changes to the labour-force participation rate (LFPR), which is the percentage of people in the labour force, whether employed or actively seeking employment. The LFPR for women has, in fact, continued to gradually improve, as data from the National Labour Force Survey (Sakernas) show (). The rate in August was 53.1% in 2020 and 53.3% in 2021. Both rates are higher than the rate recorded before the pandemic, in 2019 (51.9%). Meanwhile, for males the LFPR was lower during the pandemic than before it. Data from the February 2022 round of Sakernas show that the LFPR slightly increased to 54.3% for women and to 83.7% for men. It is important to note, though, that the rise in the LFPR for women likely shows that many women have been trying to assist their families by creating or participating in informal employment. As the economic shock primarily affected the formal sector, causing income loss and uncertainty for households, many women took up work in the informal sector. Therefore, despite the overall increase in the LFPR for women, the quality and conditions of employment did not necessarily improve.

FIGURE 4 Labour-Force Participation Rate, Indonesia, 2015–21

Source: BPS (2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021).

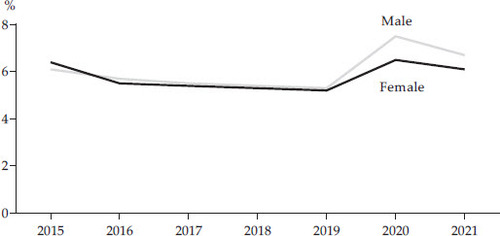

On the other hand, the August unemployment rate for women increased, from 5.2% in 2019 to 6.5% in 2020 (). This suggests that many women in the formal sector lost their jobs at the start of the pandemic (Ngadi, Meliana and Purba Citation2020). However, in 2021 the unemployment rate for women slightly decreased to 6.1%. The rate for men followed a similar trend, although unemployment was higher in 2020 and 2021 for men than for women. This supports the idea that, while more men became unemployed, many women entered the informal sector. Withdrawal from the labour force was also likely exacerbated by government policies that limited mobility outside the house.

FIGURE 5 Unemployment Rate by Gender, Indonesia, 2015–21

Source: BPS (2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021).

The decisions of women to exit or remain in the labour force are captured by the added-worker effect and the discouraged-worker effect (Lee and Parasnis Citation2014). The added-worker effect describes a temporary increase in the labour supply of married women whose husbands have become unemployed. Stephens (Citation2002) examined the added-worker effect as a response to a permanent loss of earnings caused by job loss, rather than as an adjustment to a temporary loss of earnings. He found that consumption smoothing occurs if wives slightly increase their labour supply prior to their husbands’ job loss and then increase it much more after the loss. He showed that these conditions can help smooth a household’s consumption, although the loss of family income remains substantial.

In contrast, the discouraged-worker effect is where some unemployed workers become so discouraged at the prospect of finding a job during an economic contraction that they withdraw from the labour force. The discouraged-worker effect tends to prevail in member countries of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), whereas the added-worker effect tends to prevail in developing countries (Lee and Parasnis Citation2014).

For Indonesia, the data suggest that female workers increasingly became discouraged at the start of pandemic, in 2020. The year was full of uncertainty, and many women who had been laid off were left to wait for changes in the pandemic situation or in the government policies related mobility restrictions. A year after the pandemic, female employment appeared to increase, especially in the informal sector, as women strove to help their families earn income. This increase in employment was possibly due to the added-worker effect, as well as the economic recovery of the sectors where women’s jobs are concentrated.Footnote6

In relation to sectoral composition, employment declined in almost all sectors during 2019–21. However, in this period, men and especially women increased their shares of employment in agriculture, forestry and fishing, and wholesale and retail trade and motor-vehicle repair. Males suffered the largest decline in jobs in construction and manufacturing, whereas females lost the most jobs in the otherservices sector (BPS 2019, 2021).

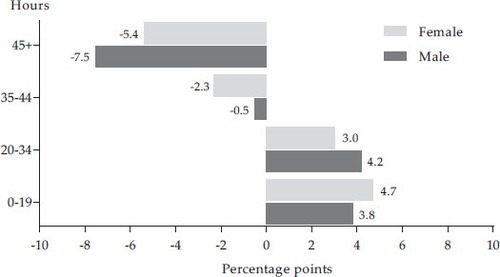

Reductions in Hours of Work

The pandemic caused massive reductions in the working hours per week of both men and women. However, women faced a larger reduction in their hours during the pandemic than men did. Women also work in sectors and occupations that have less opportunity for remote work, so they may have experienced a more significant drop in employment and earnings than men.

During 2019–20, the share of people who worked 35 hours or more per week declined (). However, the share of people who worked fewer than 35 hours per week increased. This indicates that many workers shifted from full-time to part-time work. The overall trends for men and women were similar. However, the share of women who worked full-time, more than 35 hours per week, declined drastically while the share of women who worked 19 hours or fewer per week increased drastically, more so than the share of men did. This brings us to the developments in the informal sector, especially those related to the pandemic.

Women and the Informal Sector in Indonesia

It is first important to ask who the women in the informal sector are. In developing countries, most women work in vulnerable situations—as domestic workers, homebased workers or contributors to family work—that are not covered by labour legislation (ILO 2018; ILO and OECD Citation2019; Borjas Citation2016). This type of informal work offers lower wages than formal employment and no security or social protections such as contracts, pensions, health insurance or paid sick leave (Ramani et al. Citation2013). There is a significant overlap between people who are informally employed and those who are poor. These people also tend to have lower levels of education and skills (ILO 2018; Bonnet, Vanek and Chen Citation2019).

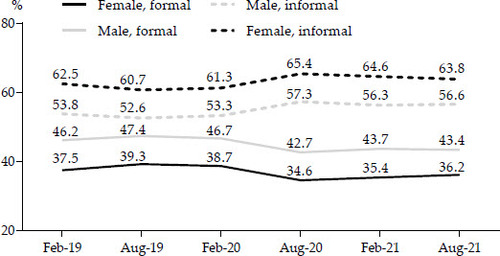

As shown in , from February 2020, larger percentages of people worked in Indonesia’s informal sector, leaving much smaller percentages in the formal sector. This was especially the case for women. In August 2019, the percentage of women in the informal sector was almost 61%, with about 39% in the formal sector. By August 2020, after Covid-19 had hit Indonesia, the percentage of informally employed women had increased to more than 65%, with about 35% formally employed. While the gap shown in between formal and informal employment levels is much larger for women than for men, it has been relatively consistent for both genders since August 2020.

FIGURE 7 Formal and Informal Employment Rates for Women and Men, 2019–21

Source: BPS (2019, 2020, 2021).

The Role of Entrepreneurship and Digitalisation for Women in Indonesia

Despite its negative impacts, the Covid-19 pandemic has accelerated the adoption of digital technology, especially online business models and platforms (Strusani and Houngbonon Citation2021). The proliferation of this technology has provided interesting work options, particularly for married women, as they can work and manage their businesses from home while taking care of their families (Sulistyaningrum et al. Citation2022). Digitalisation has encouraged women to participate in the labour market, especially in the informal sector. Wihardja and Wibisana (Citation2021) showed that women owned 56% of Indonesia’s digital businesses in 2020, almost all of which were micro, small and medium enterprises (MSMEs). They also noted that the prevalence of female entrepreneurs who used e-commerce increased from 2.7% in 2017 to 7.5% in 2020. Digital merchants are most likely to be women aged 25–34, and about 24% of all digital merchants are female ‘homemakers’. More than half of female merchants used e-commerce as a source of supplementary income in their households, probably to compensate for a possible loss of income during the pandemic.Footnote7

Wage Differentials and Labour Incomes in Indonesia

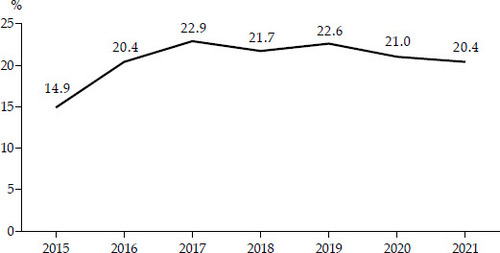

A major structural obstacle for Indonesia’s labour market is the gender-wage gap. Despite a decrease in the gender gap in labour participation, the gender-wage gap remains large in Indonesia, as it does in many developing and developed countries. On average, without controlling for other factors, we see that women earned 20% less than men did in 2021 (). The gender-wage gap was almost 23% in 2019, but the gap narrowed slightly in 2020 and 2021.Footnote8

FIGURE 8 How Much Less Women Are Paid than Men in Indonesia, 2015–21

Source: BPS (2015, 2016, 2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021).

The gender-wage gap is believed to reflect gender-based discrimination in the labour market more than differences in productivity across groups. The gap exists regardless of age or even educational attainment. Education alone seems unable to narrow the gap in pay (ILO and OECD Citation2020). Nonetheless, the gap tended to decrease during the pandemic, especially because of pressures on wages in areas where male jobs were most threatened, such as construction.

LONG-TERM IMPLICATIONS OF THE PANDEMIC FOR GENDER ROLES

Impacts of School Closures on Learning and Earning

The Covid-19 pandemic has affected not only adult women but also girls. The Asian Development Bank (ADB 2022b) estimated a reduction in learning-adjusted years of schooling, a measure of learning that accounts for both the quantity and quality of education. The analysis considered two ways that school closures affect boys and girls differently: (1) access to remote education, which can be represented by the difference in internet access during the pandemic; and (2) a higher propensity of females to drop out of school. The modelling shows that the gender gaps in learning losses were around 5% or less in Indonesia and neighbouring countries such as Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. These gaps in learning losses were in favour of boys, except in Singapore.

Losses in learning can reduce future productivity and hamper earning potential. shows the expected losses in per capita earnings associated with the foregone learning in Indonesia and selected Southeast Asian countries. Since labour markets place a higher premium on the education of girls than of boys, as the returns from schooling are higher for girls (Psacharopoulos and Patrinos Citation2018), the learning gaps are projected to result in substantial earning gaps between women and men. This shows the importance of investment in education for girls. Thus, foregone learning translates into expected earning losses that are, on average, more than 20% higher for girls than boys in Indonesia. In this context, Indonesia is comparable to Singapore and better off than other Southeast Asian countries.

Table 6. Impact of School Closures on Earning for Women and Men in Indonesia and Selected Countries

Indirect Health Impacts of the Pandemic

Disruption of Health Services for Women and Children in Indonesia

The direct health impacts of the pandemic, such as deaths attributed to Covid-19 infection, have been well documented. Less well known are the indirect impacts on health, including through the disruption of health services for women and children. For example, access to health services related to child immunisation, prenatal care and family planning was affected during the pandemic as health services were devoted to Covid-19 patients. The World Bank (2022a) found that at least 22% of households that needed access to immunisation could not access it between late July and early August 2020. Moreover, between 13% and 16% of households that needed family-planning services from early November in 2020 to late March in 2021 could not access them. The disruption in access to health services is likely to have long-term health implications for women and children.

Further, a study on the long-term impacts of Covid-19 by Gibson and Olivia (Citation2020) found that the pandemic will likely affect both quality and quantity of life through a loss of potential income. They estimated a 13% loss in real income over the long run in Indonesia due to the restriction of economic activities and other economic shocks. This loss, according to the authors, translates into a reduction in life expectancy of 2.6%, or 1.7 years. Life expectancy in Indonesia is very sensitive to income changes: for every 10% increase in income, life expectancy rises by just over 2%, equal to 1.4 years for males and 1.5 years for females.Footnote9

Mental Health and Domestic Violence in Indonesia

Mental health disorders will be another long-term impact of the pandemic. While this issue is still more commonly discussed in the context of developed countries, Indonesia and other developing countries should consider the possible long-term implications of the pandemic on the mental health of their populations.

An Ipsos (2020) survey covering almost 13,000 working men and women across 28 countries, including some developing countries (although not Indonesia), found that 56% of workers experienced at least some increase in anxiety about job security as a result of the pandemic. It also found that 55% experienced stress owing to changes in work routines and organisation and 45% owing to family pressures such as childcare. About 50% had difficulty finding a work–life balance, because of the pandemic. Women were among those especially prone to reporting adverse effects on their well-being from pandemic-related changes in their work life. From an economic viewpoint, this information is important since, even well before the pandemic (in 2010), poor mental health was estimated to cost the global economy about $2.5 trillion per year owing to reduced productivity and health, with this cost projected to increase to $6 trillion by 2030 (Lancet Global Health 2020).

Assessing women’s vulnerability, particularly concerning mental health and well-being, is challenging, as nationwide data are scarce and previous research tends to be limited in scope. However, drawing lessons from the research is possible. For example, data from the Global Burden of Disease research (IHME 2020) show that, prior to the pandemic (1990–2019), women in Indonesia, Vietnam, Malaysia and the Philippines had a high incidence of being more likely to experience mental disorders than men. Many studies have also found a growing number of women in Indonesia suffer from psychological distress or mental disorders owing to the pandemic. UN Women (Citation2020a) found that 57% of women have suffered increased stress and anxiety since the start of the pandemic, whereas only 48% of men have. UNICEF et al. (2021) also found that challenges during the pandemic have left 19.7% female household heads feeling unhappier, more stressed or more depressed, compared with 16.8% of male household heads (the higher rate for women may relate to the triple burden they experience).

Research has also found that several demographic variables might have increased the risks of women experiencing these disorders. Megatsari et al. (Citation2021) found that younger women and women with less education were at higher risk of developing mental health disorders (however, other studies have found that people with more education are at greater risk). Poor coping skills and inadequate social or family support can also worsen mental health.

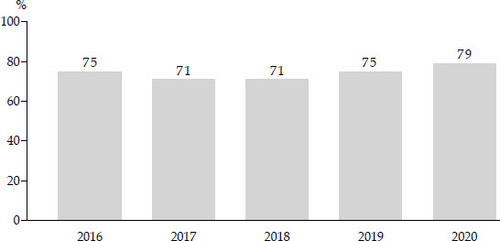

Job or income loss and the incidence of gender-based violence may also contribute to a disproportionate deterioration of mental health among women in Indonesia (UN Women Citation2020b). The lockdowns during the pandemic are believed to have resulted in domestic problems and violence by men against women. shows the high proportion of domestic violence committed against women during the pandemic. In Indonesia, the National Commission on Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan 2021) noted that stress due to economic hardship experienced by the household (such as job loss) and the food insecurity this caused may have made women more vulnerable to gender-based violence during the pandemic. Expenditure tended to increase for food and other things, such as access to the internet and other online study and work needs.

FIGURE 9 Percentage of Domestic Violence Committed against Women, 2016–20

Source: Komnas Perempuan (2017, 2018, 2019, 2020, 2021).

Note: The percentages are calculated from the total of reported cases of violence against women. Caution is needed in interpreting these data owing to the challenges in collecting data on cases of violence against women.

From a policy perspective, a positive development is Law 12/2022 on Sexual Violence Crimes, which is intended to prevent sexual violence and strengthen the rights of victims. Another important piece of legislation is Regulation 30/2021 on the Prevention and Handling of Sexual Violence in Higher Education, issued by the Ministry of Education, Culture, Research and Technology to prevent sexual violence in universities. This regulation covers not only physical sexual violence but also verbal and non-physical attacks, as well as online attacks. However, its implementation will matter the most, and allocating enough funds to make a difference will be a serious challenge.

The Future Role of Technology and Digitalisation

UN Women (Citation2020d) found that the sustainability of business opportunities for women who own micro and small businesses will depend on several factors. These include whether the business is a ‘necessity business’ (one started to help manage a household’s economic situation) or a growth-oriented business (started by owners who see an opportunity to grow a profitable business); what business complements are involved (for example, complementary skills for service improvement, marketing strategies, financial resources or support); and external factors, particularly the issue of the digital divide.

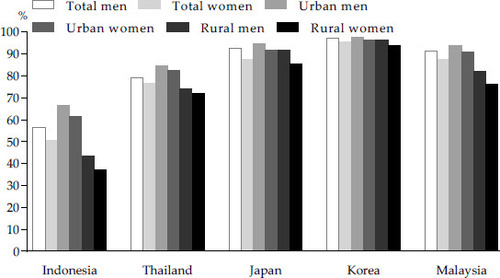

The level of internet use in Indonesia lags behind the levels in several other Asian countries (). Moreover, women tend to be more disadvantaged in terms of digital access in Asia. A digital divide between genders persists particularly in Indonesia. Even though more than half of women use the internet in the country, the gender gap in internet use is about 6 percentage points, which is wider than the gaps in Thailand (2.2 percentage points) and Japan (5 percentage points), where the data cover comparable populations. also shows that the percentage of women who use the internet in Indonesia is smaller than the percentages in these two countries. A SMERU (Citation2022) study shows that this digital divide between genders has persisted in Indonesia for at least a decade, with the trend suggesting it may not close in the near future.

FIGURE 10 Internet Use by Urban and Rural Women and Men in Indonesia and Selected Countries, 2020

Source: ITU (International Telecommunication Union) (Citation2021).

Note: The data for Indonesia cover people aged 5 or older; for Thailand and Japan, aged 6 or older; for Korea aged 15–74; and for Malaysia aged 15 or older. Data disaggregated by urban or rural status for other countries such as the Philippines and Vietnam are not available.

This is despite the trend also showing that internet use for both women and men increased over time, as less than a quarter of women in 2011 used the internet (SMERU Citation2022). shows that the urban–rural difference in internet use is stark. The gender gap is worse in rural areas than in urban areas; less than 38% of rural women in Indonesia use the internet. The SMERU study also shows a large gap between rural and urban internet use. It argues that the patriarchal cultures highly entrenched in rural areas and in many low-income families might result in the control of smartphones and internet connections by husbands or sons.

The future of working remotely from home will depend on how new working arrangements affect the well-being of women. While women working from home will have more choice in how they juggle work and care, this might have blurred the boundaries between work and family roles, and influenced work–family conflict levels (Neo, Tan and Chew Citation2022). Empirical research from Indonesia has produced mixed findings: working from home can be stressful and challenging for women, since they need to balance their work commitments and home duties, and also need to manage boredom during isolation (Irawanto, Novianti and Roz Citation2021). Further, many jobs still cannot be performed remotely from home, particularly for low-income women. For women who can work at home, how workers and employers respond to a hybrid working model is yet to be seen. For example, if men are more likely to return to the office and women more likely to continue working from home, gender inequalities in the workplace may worsen. Men may end up getting more face-to-face contact with their employers or managers, boosting their chances of promotion (Wood, Griffiths and Crowley Citation2021).

CONCLUSIONS AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS

Evidence and narratives on the pandemic indicate that it has disproportionately disadvantaged women. This comes following a long history of female disadvantage and structural problems such as social norms that favour males in many societies, including Indonesia. Our article has advanced several key messages. First, many women bear the triple burden of productive, reproductive and community roles, with the weight of the reproductive and productive burdens increasing in recent times owing to the impacts of the pandemic. These burdens will further widen gender gaps in the labour force if women’s productivity in the labour market declines, or if women choose to leave the labour force. Second, many of the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic are those where women are more likely to work, and so many women had their hours of work reduced or were fired. Unlike previous crises that tended to produce the added-worker effect (a short-term increase in the labour supply of women whose husbands have become unemployed), the Covid-19 pandemic may have produced both the discouraged-worker effect and the added-worker effect. The data also show the pandemic has had heterogeneous effects on women, especially between highly skilled and less-skilled women, particularly in the labour market. Many women on low incomes work in low-skilled or informal sectors and are likely to lose income during crises such as the pandemic. Many households, particularly female-headed households, are at high risk of falling into poverty during such crises. The long-term impacts of the pandemic will also put women’s lifetime earnings and mental health at risk. If the impacts of the pandemic are not addressed properly, gender inequality will worsen in the long run as existing structural social and economic inequalities deepen. While digitalisation brings new opportunities for female entrepreneurship, the digital divide between genders in both urban and rural areas still needs to be bridged.

This Survey has also discussed the opportunities that positive economic recovery has created for women. In particular, it has considered the sectors where working women have been concentrated and the opportunities for women who work in MSMEs. We have argued that the role of Indonesian women will become more important to the economy in the future. Through a gender lens, we have looked at the policy response to the pandemic and downturn. The recovery should be designed for women and cover both immediate and long-term actions. Having a more gender-informed policy approach would improve the health, education, and economic and social welfare of families, households and communities. The immediate responses to Covid-19 impacts should include efforts to boost women’s participation in the labour market. The Indonesian government has introduced a pre-employment card, Kartu Prakerja, that is intended to facilitate youth employment. In light of the pandemic, the scope of the pre-employment card has expanded to support recent graduates and workers affected by lay-offs. The scope should also now support digital-technology training for female entrepreneurs specifically, to support their small or medium enterprises.

In addition, a priority should be to improve access to formal childcare for women, including by increasing the number of public preschools in Indonesia, as this has been found to boost the likelihood that women with young children will participate in the labour market (Halim, Johnson and Perova Citation2018). Other policies could increase flexibility in employment contracts in order to address some of the problems women face. For example, these policies could ensure the provision of nursing rooms in workplaces, the option of part-time work in continuing (not only casual) positions, and access to maternity leave that meets the ILO’s standard.

Immediate action should also cover the role of government interventions in sustaining social-assistance programs such as the Family Hope Program (PKH). This conditional cash-transfer program has offered social protection to women with low socio-economic backgrounds (Wasim et al. Citation2019; World Bank 2011). PKH, as well as the Non-Cash Food Assistance program (BPNT), the Cash Social Assistance program (BST) and the Village Fund Cash Assistance program (BLT DD), has substantially mitigated the impact of the pandemic on household welfare (Suryahadi, Al Izzati and Yumna Citation2021).

To respond to the long-term impacts of the pandemic on mental health among women, the government should continue to invest in human capital, which includes not only education but also physical and mental health. However, the lack of funding for social investment is a major constraint. Central funding for Indonesian mental health is only 1% of the national health budget, whereas health expenditure is about 3% of GDP. Further, at the local level, primary health centres still focus on physical health. It may be time to start thinking about how to encourage the private sector to help close the gaps in mental-health services, by providing the services required by employees.

Policymakers might consider minimum quotas for the employment of women in specific regions or sectors to help balance skills across genders in the workplace— for example, quotas in desirable roles such as leadership positions in politics, government and business. Previous literature has explored the use of quotas for women who work in key sectors, but they have returned mixed findings (Aguilera, Kuppuswamy and Anand Citation2021; Duppati et al. Citation2020). The possible advantages of using quotas include that female managers may be more transformational than their male counterparts (Pande and Ford Citation2011). Therefore, they can improve organisational performance, productivity and female labour-force participation in key sectors, as in the case of India, where regulations require its executive boards to include at least one woman. Gender quotas are designed to be filled based on merit.

Reducing the interrelated structural barriers, including by providing more flexibility in the labour market, is crucial for enabling greater participation of women in the economy. For less-educated women, human-capital development is still vital. Giving women mobility and technical support, especially women in MSMEs, and improving their digital capability will be essential.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors wish to thank several colleagues for their valuable comments and feedback on earlier drafts, including Titik Anas, Anne Booth, Howard Dick, Sarah Dong, Natasha Hamilton-Hart, Hal Hill, Blane Lewis, Peter McCawley, Dionisius Narjoko, Susan Olivia, Arianto Patunru, Budy Resosudarmo, Asep Suryahadi, Firman Witoelar and other distinguished Indonesia Project colleagues. Special thanks are due to Chris Manning, who has provided guidance and advice in preparing this Survey. The authors also thank the participants of the Indonesia Study Group seminar on 18 May 2022 for their useful feedback, and Zuhairan Yunmi Yunan and Putri Aulia Silkana for their research assistance.

Notes

1 The GDI measures gender gaps in human development achievements (HDI) in three basic dimensions: health, knowledge and living standards. The GDI is only one of several indices measuring gender disparities. Indices are also compiled by organisations such as the World Economic Forum, which produces the Global Gender Gap Index. Caution should be taken when analysing countries’ positions in terms of gender disparity.

2 The mobility restrictions designed to contain transmission of Covid-19 have been discussed in previous studies by, for example, Eichenbaum, Rebelo and Trabandt (Citation2021), and Suryahadi, Al Izzati and Suryadarma (Citation2020).

3 The Bank of Indonesia 7-Day Reserve Repo Rate was 3.5% in February 2022 and has remained unchanged since March 2021. This was 2% lower than the 2015–19 rate. In 2021, the reserve buffer was eight months of imports (World Bank Citation2022c).

4 Studies by Bulbeck (Citation2005), Utomo (Citation1997) and Utomo (Citation2016) present evidence that traditional views regarding gender roles are still prevalent in Indonesia. These views include that raising children, along with doing domestic chores, is part of a wife’s responsibility, whereas the husband is viewed as being responsible for earning a living.

5 For more information, see https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/36945.

6 The likely coexistence of discouraged and added workers during the pandemic differs from the situation observed during past economic shocks such as the Asian financial crisis of 1997–98, when increases in LFP for women came mainly from increases in family labour (Manning Citation2000; Thomas, Beegle and Frankenberg Citation2000).

7 The sales of female merchants were inferior to those of male merchants. This may be because of several factors, such as a lower value of products sold by women, higher competition in the markets women sell into, and the tendency of women to reduce their consumption of feminine products during the pandemic (Wihardja and Wibisana Citation2021).

8 From 2015 to 2017, the gender-wage differential increased dramatically. This is likely in part because of an increase in the demand for labour in the construction sector due to an increase in infrastructure development.

9 Gibson and Olivia (Citation2020) compared two scenarios of GDP growth per capita: one under normal conditions and a second under the conditions of the Covid-19 shock. Caution is needed in interpreting this result as modelling depends on the assumptions used.

REFERENCES

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2022a. ‘Asian Development Outlook 2022: Statistical Appendix Tables’. ADB Data Library. https://data.adb.org/dataset/asian-development-outlook-ado-2022-statistical-appendix-tables

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2022b. Falling Further Behind: The Cost of Covid-19 School Closures by Gender and Wealth. Manila: ADB. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/784041/ado2022-learning-losses.pdf

- Aguilera, Ruth V., Venkat Kuppuswamy and Rahul Anand. 2021. ‘What Happened When India Mandated Gender Diversity on Boards’. Harvard Business Review, 5 February 2021. https://hbr.org/2021/02/what-happened-when-india-mandated-gender-diversity-on-boards

- Alon, Titan, Matthias Doepke, Jane Olmstead-Rumsey and Michèle Tertilt. 2020. ‘The Impact of Covid-19 on Gender Equality’. NBER Working Paper Series 26947, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, April 2020. http://www.nber.org/papers/w26947

- Bank Indonesia. 2022. ‘Balance of Payments 2018-2022’. https://www.bi.go.id/en/statistik/ekonomi-keuangan/seki/Default.aspx#headingFour

- Bonnet, Florence, Joann Vanek and Martha Chen. 2019. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Brief. Manchester, UK: WIEGO. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---ed_protect/---protrav/---travail/documents/publication/wcms_711798.pdf

- Borjas, George J. 2016. Labor Economics. Sixth ed. New York: McGraw-Hill.

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2015. Labor Force Situation in Indonesia: August 2015 [Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2015]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2015/11/30/311dc33e7624d47529ec4800/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indonesia-agustus-2015.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2016. Labor Force Situation in Indonesia: August 2016 [Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2016]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2016/11/30/d12d7d2096f263801ae18634/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indo-nesia-agustus-2016.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2017. Labor Force Situation in Indonesia: August 2017 [Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2017]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2017/11/30/0daa04d8d9e8e30e43a55d1a/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indonesia-agustus-2017.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2018. Labor Force Situation in Indonesia: August 2018 [Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2018]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2018/11/30/6d8a8eb26ac657f7bd170fca/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indonesia-agustus-2018.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2019. Labor Force Situation in Indonesia: August 2019 [Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2019]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2019/11/29/96138ece33ccc220007acbdd/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indonesia-agustus-2019.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2020. Labor Force Situation in Indonesia: August 2020 [Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2020]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2020/11/30/307a288d678f91b9be362021/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indonesia-agustus-2020.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2021. Labor Force Situation in Indonesia: August 2021 [Keadaan Angkatan Kerja di Indonesia Agustus 2021]. Jakarta: BPS. https://www.bps.go.id/publication/2021/12/07/ee355feea591c3b6841d361b/keadaan-angkatan-kerja-di-indo-nesia-agustus-2021.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2022a. ‘Laju Pertumbuhan PDB Menurut Pengeluaran (persen)’ [GDP Growth Rate by Expenditure (percentage)]. 2010 Series. Data series subject: Gross Domestic Product (expenditure). Updated 9 May 2022. https://bps.go.id/indicator/169/108/1/-seri-2010-4-laju-pertumbuhan-pdb-menurut-pengeluaran.html

- BPS (Statistics Indonesia). 2022b. ‘Laju Pertumbuhan PDB (persen)’ [GDP Growth Rate (percentage)]. 2010 Series. Data series subject: Gross Domestic Product (business). Updated 9 May 2022. https://bps.go.id/indicator/11/104/1/-seri-2010-laju-pertumbuhan-pdb-seri-2010.html

- Bulbeck, Chilla. 2005. ‘The Mighty Pillar of the Family’: Young People’s Vocabularies on Household Gender Arrangements in the Asia-Pacific Region’. Gender, Work and Organization 12 (1): 14–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0432.2005.00260.x

- Cameron, Lisa, Diana Contreras Suarez and William Rowell. 2019. ‘Female Labour Force Participation in Indonesia: Why Has It Stalled?’ Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 55 (2): 157–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2018.1530727

- CEIC. 2022. ‘CDMNext’. Online database platform. https://www.ceicdata.com/en Christina, Bernadette. 2022. ‘How Indonesia’s Policy Stumbles over Palm Oil Have Unfolded’. Jakarta Post, 29 April 2022. https://www.thejakartapost.com/business/2022/04/29/how-indonesias-policy-stumbles-over-palm-oil-have-unfolded.html

- Collins, Caitlyn, Liana Christin Landivar, Leah Ruppanner and William J. Scarborough. 2021. ‘Covid-19 and the Gender Gap in Work Hours’. Gender, Work and Organization 28 (S1): 101–12. https://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12506

- Dang, Hai-Anh H. and Cuong Viet Nguyen. 2021. ‘Gender Inequality during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Income, Expenditure, Savings, and Job Loss’. World Development 140 (April): 105296. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.105296

- Delaney, Annie and Fiona Macdonald. 2018. ‘Thinking about Informality: Gender (in) Equality (in) Decent Work across Geographic and Economic Boundaries’. Labour and Industry: A Journal of the Social and Economic Relations of Work 28 (2): 99–114. https://doi.org/10.1080/10301763.2018.1475024

- Duppati, Geeta, Narendar V. Rao, Neha Matlani, Frank Scrimgeour and Debasis Patnaik. 2020. ‘Gender Diversity and Firm Performance: Evidence from India and Singapore’. Applied Economics 52 (14): 1553–65. doi: 10.1080/00036846.2019.1676872

- Eichenbaum, Martin S., Sergio Rebelo and Mathias Trabandt. 2021. ‘The Macroeconomics of Epidemics’. NBER Working Paper Series 26882, National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA, revised April 2021. https://doi.org/10.3386/w26882

- Gibson, John and Susan Olivia. 2020. ‘Direct and Indirect Effects of Covid-19 on Life Expectancy and Poverty in Indonesia’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 56 (3): 325–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2020.1847244

- Halim, Daniel, Hillary Johnson and Elizaveta Perova. 2018. ‘Does Access to Preschool Increase Women’s Employment?’. East Asia and Pacific Gender Policy Brief Issue 3. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/31486

- IHME (Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation). 2020. ‘GBD Results’. IHME. https://vizhub.healthdata.org/gbd-results/

- ILO (International Labour Organization). 2018. Women and Men in the Informal Economy: A Statistical Picture. Third ed. Geneva: ILO. https://www.ilo.org/global/publications/books/WCMS_626831/lang--en/index.htm

- ILO (International Labour Organization). 2021. ILO Monitor: Covid-19 and the World of Work. Seventh ed. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@dgreports/@dcomm/documents/briefingnote/wcms_767028.pdf

- ILO (International Labour Organization) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2020. ‘The Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Jobs and Incomes in G20 Economies’. Paper prepared for the G20 summit in Riyadh, Saudia Arabia, 21–22 November 2020. https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/---dgreports/---cab-inet/documents/publication/wcms_756331.pdf

- ILO (International Labour Organization) and the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). 2019. Tackling Vulnerability in the Informal Economy. Development Centre Studies. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/939b7bcd-en

- Ipsos. 2020. The Covid-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Workers’ Lives: 28-Country Ipsos Survey for the World Economic Forum. Paris: Ipsos. https://www.ipsos.com/sites/default/files/ct/news/documents/2020-12/impact-of-the-covid-19-pandemic-on-workers-lives-report.pdf

- Irawanto, Dodi, Khusnul Novianti and Kenny Roz. 2021. ‘Work from Home: Measuring Satisfaction between Work–Life Balance and Work Stress during the Covid-19 Pandemic in Indonesia’. Economies 9 (3): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/economies9030096

- ITU (International Telecommunication Union). 2021. ‘Individuals Using Internet’. Statistics. Accessed 4 June 2022. https://www.itu.int/en/ITU-D/Statistics/Pages/stat/default.aspx

- Jadhav, Rajendra. 2022. ‘Indonesia Export Ban Traps 290,000 T of Palm Oil Shipments for India’. Reuters, 28 April 2022. https://www.reuters.com/world/india/indonesia-export-ban-traps-290000-t-palm-oil-shipments-india-trade-2022-04-28/#:~:text=MUMBAI%2C%20April%2028%20(Reuters),officials%20told%20Reuters%20on%20Thursday

- Jayachandran, Seema. 2020. ‘Social Norms as a Barrier to Women’s Employment in Developing Countries’. NBER Working Paper Series 27449, Cambridge, MA. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27449

- Komnas Perempuan (National Commission on Violence against Women). 2017. Labirin Kekerasan terhadap Perempuan: Dari Gang Rape hingga Femicide, Alarm bagi Negara untuk Bertindak Tepat [The Labyrinth of Violence against Women: From Gang Rape to Femicide, an Alarm for the State to Act Rightly]. Jakarta: Komnas Perempuan. https://komnasperempuan.go.id/catatan-tahunan-detail/catahu-2017-labirin-kekerasan-terha-dap-perempuan-dari-gang-rape-hingga-femicide-alarm-bagi-negara-untuk-bertindak-tepat-catatan-kekerasan-terhadap-perempuan-tahun-2016

- Komnas Perempuan (National Commission on Violence against Women). 2018. Tergerusnya Ruang Aman Perempuan dalam Pusaran Politik Populisme [The Erosion of Women’s Safe Spaces in the Political Vortex of Populism]. Jakarta: Komnas Perempuan. https://komnasperempuan.go.id/catatan-tahunan-detail/catahu-2018-tergerusnya-ruang-aman-perempuan-dalam-pusaran-politik-populisme-catatan-kekerasan-terhadap-perempuan-tahun-2017

- Komnas Perempuan (National Commission on Violence against Women). 2019. Korban Bersuara, Data Berbicara, Sahkan RUU Penghapusan Kekerasan Seksual sebagai Wujud Komitmen Negara [Victims Speak, Data Speaks; Pass Bill on the Elimination of Sexual Violence as a Form of State Commitment]. Jakarta: Komnas Perempuan. https://komnasperempuan.go.id/catatan-tahunan-detail/catahu-2019-korban-bersuara-data-berbicara-sahkan-ruu-penghapusan-kekerasan-seksual-sebagai-wujud-komitmen-negara-catatan-kekerasan-terhadap-perempuan-tahun-2018

- Komnas Perempuan (National Commission on Violence against Women). 2020. CATAHU 2020: Kekerasan Meningkat: Kebijakan Penghapusan Kekerasan Seksual untuk Membangun Ruang Aman bagi Perempuan dan Anak Perempuan [CATAHU 2020: Violence against Women is on the Rise: Policies for the Elimination of Sexual Violence to Create Safe Spaces for Women and Girls]. Jakarta: Komnas Perempuan. https://komnasperempuan.go.id/catatan-tahunan-detail/catahu-2020-kekerasan-terhadap-perempuan-meningkat-kebijakan-penghapusan-kekerasan-seksual-menciptakan-ruang-aman-bagi-perempuan-dan-anak-perempuan-catatan-kekerasan-terhadap-perempuan-tahun-2019

- Komnas Perempuan (National Commission on Violence against Women). 2021. CATAHU 2021: Perempuan dalam Himpitan Pandemi: Lonjakan Kekerasan Seksual, Kekerasan Siber, Perkawinan Anak dan Keterbatasan Penanganan di Tengah Covid-19 [CATAHU 2021: Women in the Embrace of a Pandemic: Rise in Sexual Violence, Cyber Violence, Child Marriage and Limited Handling Amid Covid-19]. Jakarta: Komnas Perempuan. https://komnasperempuan.go.id/catatan-tahunan-detail/catahu-2021-perempuan-dalam-himpitan-pandemi-lonjakan-kekerasan-seksual-kekerasan-siber-perkawinan-anak-dan-keterbatasan-penanganan-di-tengah-covid-19

- Lancet Global Health. 2020. ‘Mental Health Matters’. Lancet Global Health 8 (11): e1352. doi: 10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30432-0

- Lee, Grace H.Y., and Jaai Parasnis. 2014. ‘Discouraged Workers in Developed Countries and Added Workers in Developing Countries? Unemployment Rate and Labour Force Participation’. Economic Modelling 41 (August): 90–98. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econmod.2014.04.005

- Lee, Ji Min, Sung-Sang Yoo and Moon Suk Hong. 2019. ‘WID, GAD or Somewhere Else? A Critical Analysis of Gender in Korea’s International Education and Development’. Journal of Contemporary Eastern Asia 18 (1): 94–123. https://doi.org/10.17477/jcea.2019.18.1.094

- Madgavkar, Anu, Olivia White, Mekala Krishnan, Deepa Mahajan and Xavier Azcue. 2020. Covid-19 and Gender Equality: Countering the Regressive Effects. McKinsey & Company. https://www.mckinsey.com/~/media/McKinsey/Industries/Public%20and%20Social%20Sector/Our%20Insights/Future%20of%20Organizations/COVID%2019%20and%20 gender%20equality%20Countering%20the%20regressive%20effects/COVID-19-and-gender-equality-Countering-the-regressive-effects-vF.pdf

- Manning, Chris. 2000. ‘Labour Market Adjustment to Indonesia’s Economic Crisis: Context, Trends and Implications’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 36 (1): 105–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074910012331337803

- Megatsari, Hario, Agung Dwi Laksono, Yeni Tri Herwanto, Kinanty Putri Sarweni, Rachmad Ardiansyah Pua Geno, Estiningtyas Nugraheni and Mursyidul Ibad. 2021. ‘Does Husband/Partner Matter in Reduce Women’s Risk of Worries?: Study of Psychosocial Burden of Covid-19 in Indonesia’. Indian Journal of Forensic Medicine and Toxicology 15 (1): 1101–06. https://doi.org/10.37506/ijfmt.v15i1.13564

- Ministry of Education and Culture. 2020. Panduan Penyelenggaraan Pembelajaran Di Masa Pandemi Coronavirus Disease 2019 (Covid-19) [Guidelines for Organising Learning During the 2019 Coronavirus Disease (Covid-19) Pandemic]. Jakarta: Ministry of Education and Culture.

- Ministry of Finance. 2022. APBN KITA: Kinerja dan Fakta [Our APBN: Performance and Facts]. March edition. Jakarta: Ministry of Finance. https://www.kemenkeu.go.id/media/19496/apbn-kita-maret-2022.pdf

- Moser, Caroline O. N. 1993. Gender and Development Planning: Theory, Practice and Training. London: Routledge.

- Nawaz, Faraha and Helen Jaqueline McLaren. 2019. ‘Silencing the Hardship: Bangladeshi Women, Microfinance and Reproductive Work’. Social Alternatives 35 (1): 19–25.

- Negara, Siwage Dharma. 2022. ‘Rising Oil Prices Throw Indonesia’s Energy Subsidies into Question’. East Asia Forum, 12 April 2022. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/04/12/rising-oil-prices-throw-indonesias-energy-subsidies-into-question/

- Neo, Loo Seng, Jean Yi Colette Tan and Tierra Wan Yi Chew. 2022. ‘The Influence of Covid-19 on Women’s Perceptions of Work-Family Conflict in Singapore’. Social Sciences 11 (2): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci11020073

- Ngadi, Ngadi, Ruth Meliana and Yanti Astrelina Purba. 2020. ‘Dampak Pandemi Covid-19 Terhadap PHK Dan Pendapatan Pekerja Di Indonesia’ [Impact of the Covid-19 Pandemic on Lay-offs and Workers’ Income in Indonesia]. Jurnal Kependudukan Indonesia July: 43–48. https://doi.org/10.14203/jki.v0i0.576

- Pande, Rohini and Deanna Ford. 2011. ‘Gender Quotas and Female Leadership’. World Development Report 2012: Gender Equality and Development Background Paper, World Bank, 7 April 2011.

- Psacharopoulos, George and Harry Anthony Patrinos. 2018. ‘Returns to Investment in Education: A Decennial Review of the Global Literature’. Education Economics 26 (5): 445–58. https://doi.org/10.1080/09645292.2018.1484426

- Ramani, Shyama V., Ajay Thutupalli, Tamás Medovarszki, Sutapa Chattopadhyay and Veena Ravichandran. 2013. ‘Women in the Informal Economy: Experiments in Governance from Emerging Countries’. United Nations University Policy Brief 5.

- Reuters. 2022. ‘Indonesia to Swap Subsidy for Price Caps on Raw Materials to Ensure Cooking Oil Supply’. Reuters, 24 May 2022. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/indo-nesia-swap-subsidy-price-caps-raw-materials-ensure-cooking-oil-supply-2022-05-24/#:~:text=JAKARTA%2C%20May%2024%20(Reuters),senior%20official%20said%20 on%20Tuesday.

- SMERU. 2022. Digital Skills Landscape in Indonesia. Diagnostic Report. Jakarta: SMERU Research Institute. https://smeru.or.id/en/publication/diagnostic-report-digital-skills-landscape-indonesia

- Somech, Anit and Anat Drach-Zahavy. 2016. ‘Gender Role Ideology’. In The Wiley Blackwell Encyclopedia of Gender and Sexuality Studies, 1–3. Singapore: Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118663219.wbegss205

- Stephens, Melvin, Jr. 2002. ‘Worker Displacement and the Added Worker Effect’. Journal of Labor Economics 20 (3): 504–37. https://doi.org/10.1086/339615

- Strusani, Davide and Georges V. Houngbonon. 2021. The Impact of Covid-19 on Disruptive Technology Adoption in Emerging Markets. Washington, DC: International Finance Corporation. https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/publications_ext_content/ifc_external_publication_site/publications_listing_page/ disruptive-tech-adoption-covid-19

- Sulistyaningrum, Eny, Budy P. Resosudarmo, Anna T. Falentina and Danang A. Darmawan. 2022. ‘Can the Internet Increase the Working Hours of Married Women in Micro and Small Enterprises? Evidence from Yogyakarta, Indonesia’. In Harnessing Digitalization for Sustainable Economic Development: Insights for Asia, edited by John Beirne and David G. Fernandez, 257–80. Tokyo: Asian Development Bank. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/761526/adbi-harnessing-digitalization-122421-web.pdf

- Suryahadi, Asep, Ridho Al Izzati and Daniel Suryadarma. 2020. ‘Estimating the Impact of Covid-19 on Poverty in Indonesia’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 56 (2): 175–92. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2020.1779390

- Suryahadi, Asep, Ridho Al Izzati and Athia Yumna. 2021. ‘The Impact of Covid-19 and Social Protection Programs on Poverty in Indonesia’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 57 (3): 267–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2021.2005519

- Thomas, Duncan, Kathleen Beegle and Elizabeth Frankenberg. 2000. ‘Labor Market Transitions of Men and Women during an Economic Crisis: Evidence from Indonesia’. Labor and Population Program. RAND Working Paper Series 00–11, August 2000. https://apps.dtic.mil/sti/citations/ADA383421

- Thomas, Vincent Fabian. 2022. ‘High Oil Prices Put New Strains on State Budget’. Jakarta Post, 13 March 2022, Jakarta. https://www.thejakartapost.com/business/2022/03/11/high-oil-prices-put-new-strains-on-state-budget.html

- Timmer, Peter. 2022. ‘Food Security Now Top Priority for G20 Cooperation’. East Asia Forum, 5 June 2022. https://www.eastasiaforum.org/2022/06/05/food-security-now-top-priority-for-g20-cooperation/

- UN Women. 2020a. Counting the Costs of Covid-19: Assessing the Impact on Gender and the Achievement of the SDGs in Indonesia. Bangkok: UN Women. https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Report_Counting%20the%20Costs%20of%20COVID-19_ English.pdf

- UN Women. 2020b. ‘Unlocking the Lockdown: The Gendered Effects of Covid-19 on Achieving the SDGs in Asia and the Pacific. Bangkok: UN Women https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/documents/COVID19/Unlocking_the_lockdown_UNWomen_2020.pdf

- UN Women. 2020c. Whose Time to Care? Unpaid Care and Domestic Work during Covid-19. New York: UN Women. https://data.unwomen.org/sites/default/files/inline-files/Whose-time-to-care-brief_0.pdf

- UN Women. 2020d. Leveraging Digitalization to Cope with Covid-19: An Indonesia Case Study on Women-Owned Micro and Small Businesses. Jakarta: UN Women. https://data.unwomen.org/publications/leveraging-digitalization-indonesia-case-study

- UNDP (United Nations Development Programme). 2020. ‘Gender Development Index’. Human Development Reports. https://hdr.undp.org/content/gender-development-index-gdi

- UNICEF (United Nations Children’s Fund), UNDP (United Nations Development Programme), Prospera (Australia Indonesia Partnership for Economic Development) and SMERU. 2021. Analysis of the Social and Economic Impacts of Covid-19 on Households and Strategic Policy Recommendations for Indonesia. Jakarta: UNICEF, UNDP, Prospera and SMERU.

- Utomo, Iwu Dwisetyani. 1997. ‘Sexual Attitudes and Behaviour of Middle-Class Young People in Jakarta’. PhD thesis, Australian National University.

- Utomo, Ariane J. 2016. ‘Gender in the Midst of Reforms: Attitudes to Work and Family Roles among University Students in Urban Indonesia’. Marriage and Family Review 52 (5): 421–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2015.1113224

- Wasim, Bubur, M. P. Karthick, Astri Tri Sulastri and T. V. S. Ravi Kumar. 2019. Report on Find-ings of Impact Evaluation of Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH). Jakarta: MicroSave Consulting. https://www.microsave.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Report-on-Findings-of-Impact-Evaluation-of-Program-Keluarga-Harapan-PKH.pdf

- WEF (World Economic Forum). 2020. Global Gender Gap Report 2020. Geneva: WEF. https://www3.weforum.org/docs/WEF_GGGR_2020.pdf

- Wihardja, Maria Monica and Putu Sanjiwacika Wibisana. 2021. ‘Gender Insights from the Covid-19 Digital Merchant Survey’ . Presentation, World Bank, Jakarta. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/eea1f0e8ba5f015c5d7cf16ce54c1ba0-0070012021/world-bank-covid-19-digital-merchant-survey-on-gender-in-indonesia

- Wood, Danielle, Kate Griffiths and Tom Crowley. 2021. Women’s Work: The Impact of the Covid Crisis on Australian Women. Grattan Institute Report 2021–01, March.Wood, Johnny. 2020. ‘Covid-19 Has Worsened Gender Inequality. These Charts Show What We Can Do about It’. Sustainable Development Impact Summit. World Economic Forum, 4 September 2020. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/09/covid-19-gender-inequality-jobs-economy/

- World Bank. 2011. Program Keluarga Harapan: Main Findings from the Impact Evaluation of Indonesia’s Pilot Household Conditional Cash Transfer Program. Jakarta: World Bank. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/589171468266179965/program-keluarga-harapan-impact-evaluation-of-indonesias-pilot-household-conditional-cash-transfer-program

- World Bank. 2022a. ‘Indonesia High-Frequency Monitoring of Covid-19 Impacts. Round 2, 26 May–5 June 2020’. Presentation, World Bank, Jakarta. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/763981610628173104-0070022021/original/IndonesiaCOVIDHiFyR2.pdf

- World Bank. 2022b. ‘Women, Business and the Law 2022‘. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://wbl.worldbank.org/en/wbl

- World Bank. 2022c. Braving the Storms. World Bank East Asia and Pacific Economic Update, Spring 2022. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://doi.org/10.1596/978-1-4648-1858-5

APPENDIX

Table 7. Balance of Payments, 2018–22 ($ billion)