Abstract

Gender equality in Indonesia is approximately at the level you would expect given the country’s level of development. Indonesia has more gender inequality than some neighbouring countries and less than others; and less than in the vast majority of Muslim-majority nations worldwide, regardless of income level. Women’s economic participation is, however, low relative to Indonesia’s level of development. Female labour force participation is low as many women leave the workforce when they get married and have children, particularly in the formal sector as formal sector employers do not generally offer flexible workplace conditions that would increase their ability to retain female employees. Social norms that position mothers as the main caregiver play an additional important role in women’s low economic participation. Public information campaigns that challenge people’s perceptions of gender norms are likely to be an important component of efforts to increase women’s economic participation. Greater female economic participation has payoffs in terms of increased household incomes. By contributing to household income and reducing economic stress within the household, greater female labour force participation is also likely to reduce family violence and so lead to happier home and family lives. A focus on increasing women’s economic empowerment would be farsighted as the country looks to recover from the pandemic and lay the groundwork for a dynamic future.

INTRODUCTION

Gender inequality—unequal treatment of individuals based on their gender— arises from differences in socially constructed gender roles within society. Its flipside, gender equality, is defined by the United Nations (UN) as the absence of discrimination in opportunities on the basis of a person’s sex, the allocation of resources and benefits or access to services.Footnote1

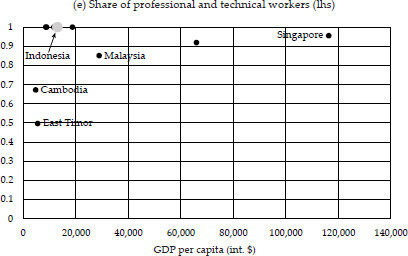

The recognition of gender inequality as a societal problem and a focus of research has come a long way since the UN General Assembly first adopted the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination against Women in 1979. Reflecting this, in the intervening 44 years, gender has become an established and productive area of economic research. In the 1970s, only six of the 65,890 research articles (< 0.01%) in the field of economics had gender in their title.Footnote2 See . This increased to 5,162 of the 651,346 articles published in the 2010s (0.8%)—an increase of 8,427% in the number of articles. The number of economic articles projected to be written on gender in the current decade (given those published to March 2023) is 10,018.

FIGURE 1 Number of Economic Publications with Gender (lhs) or Gender and Indonesia (rhs) in Their Titles

Note: The data for Indonesia exclude Indonesian-language publications.

A similar trend is observed for (English-language) economic research papers on gender in Indonesia (with gender and Indonesia in the title). There were no papers in the 1970s and 1980s, 8 in both the 1990s and 2000s and 21 in the decade 2010–20.

At the same time as gender inequality was generating research interest, various governments and international bodies commenced the routine collection of gender-disaggregated statistics. These data have allowed a quantification of the extent of gender inequality and a mapping of progress across time and comparisons across countries and world regions.

This paper draws heavily on the collection of such data and the work of a range of scholars in the field of gender research, particularly gender economics. In the next section, I compare Indonesia’s performance in terms of gender equality in several domains to that of other countries across the world, within the Muslim world and Southeast Asia. This demonstrates that Indonesia is doing better than some countries but worse than others and that Indonesia underperforms most demonstrably in terms of women’s labour force participation.

Below, I detail the trends in women’s labour force participation over the past several decades in Indonesia and discuss research shedding light on the causes of the persistent low levels of participation by Indonesian women. While various institutional factors seem to play a role, social norms around women’s role as the family’s primary caregiver are a critical driver of many women deciding not to work, or not being given the option of working. I then discuss research on how to influence social norms around women’s work and highlight potential policy options for Indonesia. Another gender issue—intimate partner violence (IPV)— is then discussed, as is what we know about attitudes to IPV and its prevalence in Indonesia. Finally, I briefly discuss the impact of Covid-19 on gender inequality in Indonesia and then conclude.

INDONESIA IN GLOBAL CONTEXT

This section draws on the World Economic Forum’s Global Gender Gap Index (G3I) to examine Indonesia’s performance in terms of gender equality. The index captures gender gaps across four dimensions: economic participation and opportunities, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment. shows the subcategories and components that are combined to generate the index.Footnote3

Table 1. Global Gender Gap Index Pillars and Indicators

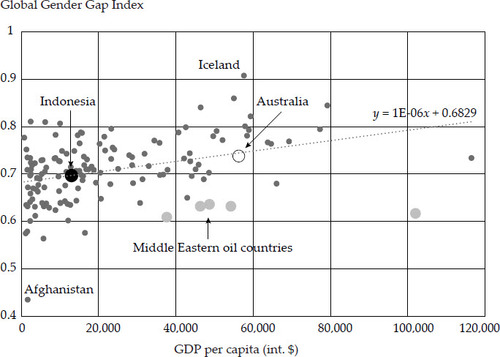

plots the G3 index against GDP per capita in international dollars (int. $).Footnote4 Indonesia’s position is shown in black. With a Global Gender Gap Index of 0.697, Indonesia is roughly in the middle of the distribution of scores across all countries and in the mid-range of scores given its level of development. Iceland scores the most highly (G3I = 0.908) and Afghanistan the most poorly (G3I = 0.435). Australia has a score of 0.738.

The figure allows an examination of whether gender equality generally improves as household incomes rise. A modest positive relationship is observed. A regression of the gender equality gap score against GDP per capita produces a coefficient that is strongly statistically significant (p < 0.01) and indicates that an increase in GDP per capita of int. $10,000 on average increases the Global Gender Gap Index by 0.011 (an improvement in gender equality) or 1.6% of the mean value of the index of 0.71. Thus, if we take this relationship as being causal, increasing Indonesia’s GDP per capita (int. $13,027) to that of Australia’s (int. $56,281) could be expected to increase Indonesia’s gender gap score by 0.048 (7%).Footnote5

An interesting observation arising from the figure is that once GDP per capita of about int. $35,000 per year is reached, almost all countries (Japan, South Korea, Brunei and Middle Eastern oil nations being notable exceptions) have a G3I score above 0.7. At per capita incomes less than that amount, there is a wide range of experience, with some countries doing exceptionally well in terms of gender equality, and others doing very poorly.Footnote6 This suggests that gender inequality varies with culture and/or policy settings and implies that governments, even in low-income countries, have the ability to improve gender equality through concerted efforts.

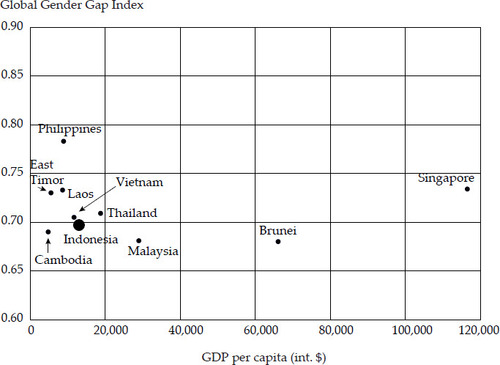

places Indonesia in the context of other countries in its region. Again, Indonesia is in the middle of the group, with less gender inequality than Malaysia and Brunei, a similar gender gap score to Cambodia, Vietnam and Thailand, and more gender inequality than East Timor, Laos and the country with by far the least gender inequality by the G3I measure, the Philippines. Singapore has a much higher GDP per capita than other countries in the region and a G3I score of 0.734, below the Philippines and just slightly above East Timor and Laos.

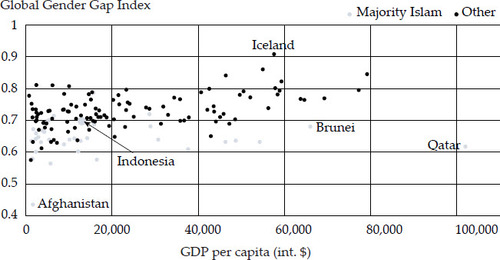

The two lowest-performing countries in Southeast Asia—Malaysia and Brunei— are Muslim-majority nations. Gender gaps in Muslim-majority nations across the world are depicted in grey in and are characterised by large gender gaps. Indonesia is the fifth-best-performing Muslim-majority nation in terms of gender equality. Only Albania (0.787), Kazakhstan (0.719), Bangladesh (0.714) and Kyrgyzstan (0.700) have a G3I score of 0.7 or above.

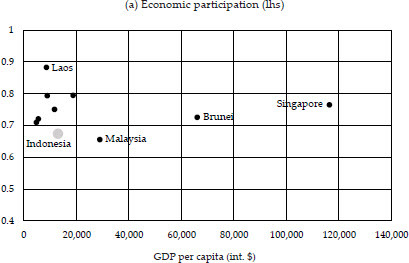

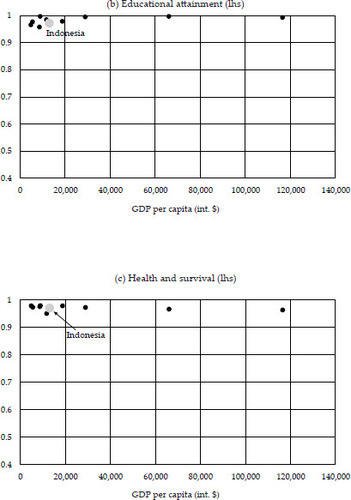

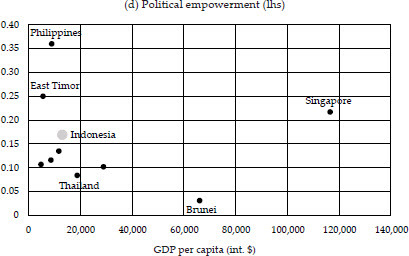

In , we disaggregate Indonesia’s gender equality performance to look at each of the sub-indices—economic participation, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment—relative to its Southeast Asian neighbours. All Southeast Asian nations perform well in terms of gender gaps in educational attainment and health and survival. There is a range of performance in terms of political empowerment, with Indonesia sitting in the middle of the range. Where Indonesia noticeably underperforms is in terms of economic participation. Only Malaysia performs worse than Indonesia in this dimension, and only marginally so.

FIGURE 5 Sub-indices of Gender Inequality, by GDP per Capita for Indonesia and other Southeast Asian Nations

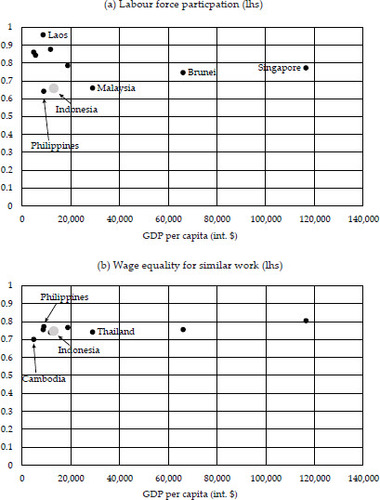

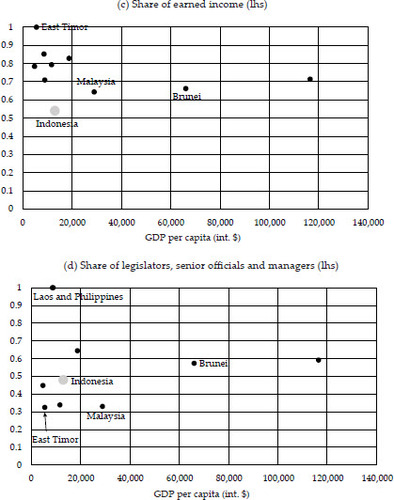

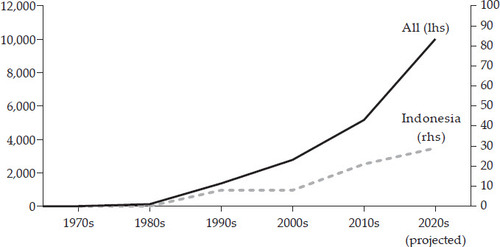

The five indicators that combine to form the economic participation sub-index are plotted in . Indonesia performs well in terms of having women in professional and technical roles and is in the middle of the range in terms of the number of female legislators, senior officials and managers. It is also in the middle of the range in terms of wage equality for similar work.Footnote7 However, in terms of women’s labour force participation and women’s share of earned income, Indonesia substantially underperforms. Compared with East Timor, where women are estimated to earn as much as men, Indonesian women are estimated to earn only 54% of men’s earnings (a gap of 46%). The low share of earnings is a direct result of the low female labour force participation. This is because the share of earnings is calculated from information on the female share of the economically active population, gender wage gaps, population shares and GDP.Footnote8

FIGURE 6 Economic Participation Indicators, by GDP per Capita for Indonesia and other Southeast Asian Nations

In the next section, we discuss research that examines why Indonesian women’s labour force participation has remained so stubbornly low for several decades.

THE LABOUR MARKET

Female Labour Force Participation

Female labour force participation in Indonesia has remained largely unchanged at just above 50% for over two decades.Footnote9 A number of papers have sought to understand why this is the case. Here I rely largely on the work of mine and coauthors that examines this question, but there is a larger body of research in this area (for example, see work by Utomo Citation2018; Schaner and Das Citation2016; and Setyonaluri Citation2013).

Cameron, Contreras Suarez and Rowell (2019) use data from the National Socio-economic Survey (Susenas) and the Village Potential Statistics (Podes) to separate life-cycle effects from changes over time in women’s labour force participation. The findings show that the raw labour market participation figures mask the offsetting impacts of various changes over this time. The industrial transition away from agriculture works to reduce women’s labour force participation, as many women who used to work on family farms are less likely to work when families move to cities or lose contact with the land for other reasons. This offsets a secular trend of increasing labour force participation, other things equal, which may reflect social norms evolving to be more accepting of women working.Footnote10

Marriage and childbearing are key drivers of the low participation rates on the supply side. However, more difficult-to-measure demand-side factors are also likely to play a role, such as employers being reluctant to hire young women who may become pregnant and a lack of workplace flexibility, which makes it difficult for mothers to work while accommodating their family responsibilities.

The Indonesian Family Life Survey allows one to observe approximately 9,000 women across a period of more than 20 years—as they first start working, get married and have children. Using these data, Cameron, Contreras Suarez and Tseng (2023) estimate that more than 46% of women are not working one year after the birth of their first child. Possibly the most surprising result is that very few women move from the formal to the informal work sector when they have a child. Anecdotally, once women have children, they are reported to forgo the formal sector in favour of the greater flexibility of the informal sector. However, the data show that while the share of working women in formal employment decreases with marriage and each child (for example, 88% of never-married 24-year-old women are in formal employment, while only 50% of women with one child are), rather than moving to the informal sector, these women largely leave the formal sector to not work at all. This is particularly the case in the manufacturing and personal services sectors.

It appears that Indonesia’s formal sector is not equipped for, and possibly not interested in, retaining women once they have a family. There are a number of policy options normally prescribed to make work in the formal sector more attractive to women. These include flexible work conditions (part-time work, working from home, compressed working weeks and flexible hours), work-based childcare and the provision of paternity leave. While these policies are likely to make working more attractive to women, the elephant in the room is the role of social norms, especially in regard to work outside the home and the local environment.Footnote11 These informal societal rules govern what is perceived as appropriate or acceptable behaviour. Gender norms that emphasise the role of women as mothers and carers are a key driver of many of the behaviours that drive gender gaps across the world (Alesina, Giuliano and Nunn Citation2013; Fernández Citation2013; Bertrand, Kamenica and Pan Citation2015; and Jayachandran Citation2021). Below, we discuss research that attempts to influence gender norms to be more accepting of working women and in that way increase women’s economic participation. We first, however, briefly discuss the gender wage gaps that also contribute to women’s low share of earned income.

Gender Wage Gaps

shows Indonesia to be in the middle of the range of Southeast Asian countries in terms of wage equality for similar work, but the gender wage gap in Indonesia is nevertheless quite substantial. Cameron and Contreras Suarez (2017) find a raw (unadjusted) gender wage gap in the formal sector of 34% and that 62% of this gap (20 percentage points) is unable to be explained by differences between men and women in terms of educational attainment, experience, marital status, status of employment, industry of employment and geographical factors. This remaining difference is likely due to the differential treatment of men and women (that is, gender discrimination).

Interestingly, the gender wage gap is much larger at the bottom end of the wage distribution than in more highly remunerated jobs. The raw wage gap in the formal sector is estimated to be 63% (women get paid only 37% of what men get paid for similar work) at the 10th percentile of the wage distribution and shrinks to 13% at the 90th percentile of the distribution. Hence, women seem to be discriminated against to a greater extent in less-skilled and lower-paying jobs than in more-skilled professions. This may reflect unskilled women’s greater difficulty bargaining for higher wages (as there is an abundance of low-skilled workers) and/or industrial segregation and social norms that allow female-dominated industries to be very poorly paid. Much of the gender wage gap remains unexplained at both the bottom and top of the wage distribution (61% of the wage gap is unexplained at the 10th percentile and 50% at the 90th percentile).

The raw gender wage gap was found to be smaller for younger cohorts, which is promising in that it suggests that the gap may diminish with time, although it could reflect that the gender wage gap is growing over time as women either accumulate experience or their human capital depreciates with time outside the labour force. The unexplained component of the gender wage gap is a larger proportion of this smaller gap at younger ages.

The gender wage gap contributes both directly to gender inequality and indirectly by making it less attractive for women to work.

SOCIAL NORMS

As discussed above, traditional gender norms are a key driver of gender inequality and, more specifically, low female labour force participation. Indonesia is a culturally diverse nation and the impact of differing social norms can be seen in the variation in female labour force participation rates across provinces. Female labour force participation is very low, for example, in West Java (44%) and Aceh (47%), where more conservative forms of Islam are practised. It is higher in North Sumatra (60%), where the mostly Christian Batak and matrilineal Minangkabau reside.Footnote12

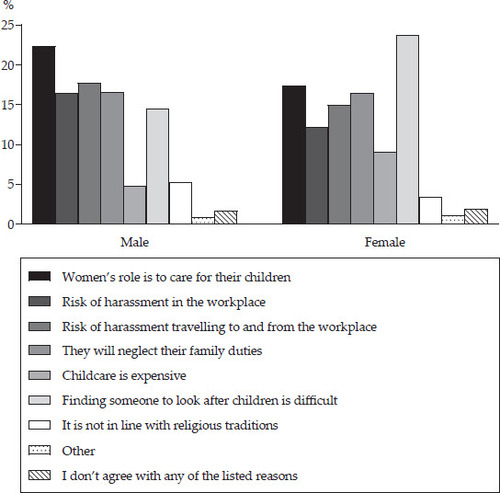

shows some reasons men and women across Indonesia give for not being supportive of women working. Using data from an online survey of Indonesian metropolitan areas in 2022, the figure shows that 22.3% of male respondents and 17.4% of female respondents report that a reason for not supporting women working is that women’s role is to care for their children.Footnote13 Further, approximately 16% of men and women report that a working woman will neglect her family duties. The risk of harassment at work and while travelling to work is also a significant concern for many. Interestingly, contravening religious traditions is not often reported as a justification for not supporting women working (5.2% and 3.4% of men and women, respectively, choose this option). The most common reason women give (23.7%) is that finding someone to look after their child is difficult, with 9.1% also reporting that childcare is expensive. This underscores that changing gender norms alone is unlikely to be sufficient to dramatically increase women’s labour force participation. As the country urbanises and wage employment becomes more widespread, complementary, concrete policy measures such as building and staffing childcare centres will also be necessary (Halim, Johnson and Perova Citation2017).

FIGURE 7 Main Reasons Not to Support Women Working, According to Male and Female Respondents

Source: Author’s survey conducted in 2022.

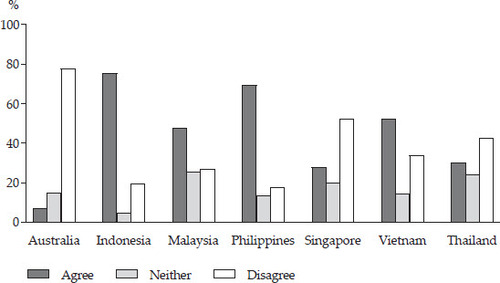

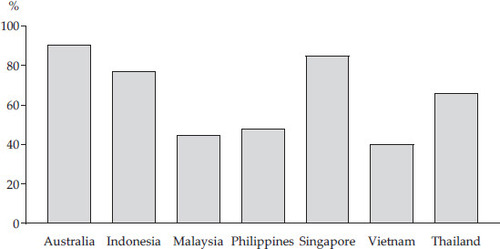

The World Values Survey is another source of information on gender norms. shows the extent to which a random sample of people from countries in the region agreed with the statement that ‘men should have more right to a job than women’. Indonesia has the highest proportion of respondents agreeing with this statement (75.5% versus 30% in Thailand, 27.9% in Singapore and 6.7% in Australia).

FIGURE 8 Respondents’ Beliefs on Whether Men Should Have More Right Than Women to a Job, by Country

Source: World Values Survey.

Governments can use public messaging to try to change social norms, but there is relatively little known about how effective such campaigns are and how best to influence such norms.

Correcting misperceptions about gender norms, however, seems a potentially promising avenue. In a randomised trial in Saudi Arabia, Bursztyn, González and Yanagizawa-Drott (Citation2020) corrected Saudi men’s misperceptions about the level of support among their male peers for women working. In the authors’ representative sample, 87% of men reported agreeing with the statement that ‘In my opinion, women should be allowed to work outside the home’. But when asked to estimate the response of other survey respondents, about 75% of men underestimated the true share. Correcting these perceptions affected an incentivised choice between receiving an online gift card and signing their wives up for a job-matching mobile application—more men chose to sign their wives up for the job-matching app. Further, three to five months later, wives of treated participants were significantly more likely to have applied for a job outside the home (up by 10 percentage points from a baseline level of 6%) and to have interviewed for a job outside the home (up by 5 percentage points from a baseline level of 1%).Footnote14

Cameron, Contreras Suarez and Setyonaluri (2023) conducted a similar intervention in Indonesia, presenting evidence of misperceptions in relation to:

women’s support for married women who have children and work outside the home for pay

men’s support for husbands and wives sharing daily childcare activities

older women’s support (mothers and mothers-in-law) for women working.

The first two types of misperceptions were evident from our online survey of more than 1,000 respondents residing in metropolitan areas across Indonesia.Footnote15 The online survey also demonstrated that respondents were concerned that their mothers and mothers-in-law were not supportive of mothers who had young children and worked for pay outside the home. Data from the 2018 World Values Survey, however, showed that there was quite high support among women in their mothers’ cohort (aged 40–60 years) for women who work and have children.Footnote16

Providing information on the extent of actual support in all or some of the above three categories increased the likelihood that respondents chose an online career-mentoring voucher for themselves (if female) or their wives (if male) over a shopping voucher by 23%–26%. Men seemed particularly responsive to the information on other men being supportive of husbands sharing childcare and there was suggestive evidence that women were more responsive than men to information about the extent of support among older women (even though both men and women reported that they were most concerned about their mother’s opinion when deciding whether the woman in the household works—15% and 16%, respectively).

Being able to change men’s attitudes is clearly important, as 20% of female respondents reported that they were not working at the time of the survey because their husbands did not wish them to, whereas the number of women who reported that they were not working because they did not wish to was only 1%. Back-of-the-envelope calculations suggest that an intervention of this sort if employed at scale could increase Indonesian female labour supply by as much as 6 percentage points (12%).

Wives who reported that their husbands were not supportive of women working reported that if they were to work, their husbands would be concerned that they would be viewed as not being able to financially provide for their family (34%). This suggests that an intervention that targets this concern could also be effective in changing norms. This is an area for future research.

VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN

The UN gives particular attention to the issue of violence against women as a contributor to gender inequality as contained in the 1993 General Assembly Declaration on the Elimination of Violence against Women. Worldwide, it is estimated that 35% of women have experienced either physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence (IPV) or non-partner sexual violence.Footnote17

In April 2022, Indonesia finally passed the Draft Law on the Elimination of Sexual Violence, following the bill first being proposed by the National Commission on the Elimination of Violence against Women (Komnas Perempuan) in 2012 and the bill first being deliberated on in the House of Representatives in 2016. The bill provides a legal framework for victims to secure justice and to implement processes for the protection and recovery of victims. It also seeks to involve the community, state, family and business in eliminating sexual violence. Komnas Perempuan is tasked with monitoring the bill’s implementation.Footnote18

There is limited evidence with which to compare Indonesia with other countries in terms of its tolerance of violence against women. The 2018 World Values Survey asks respondents whether they agree that it is ‘never justifiable for a husband to beat his wife’. By this measure, Indonesians are more condemning of family violence than their neighbours, with the exception of Singapore. Approximately 77% of Indonesians agree with this statement, compared with 85% of people in Singapore and 45% and 40% in Malaysia and Vietnam, respectively ().

FIGURE 9 Respondents Who Believe That It Is Never Justifiable for a Husband to Beat His Wife, by Country

Source: World Values Survey.

The World Health Organization (WHO) has attempted to generate a globally comparable measure of the prevalence of violence against women (WHO 2021). It has done this by taking existing data at the national level for about 160 countries and using statistical modelling to adjust for differences in the way the data were collected. Its estimates for Indonesia suggest that 22% of Indonesian women have experienced IPV in their lifetimes, with 9% having experienced it in the past 12 months.

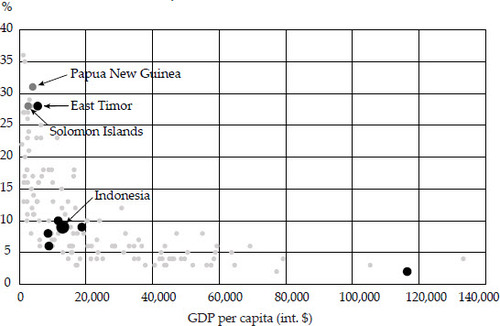

graphs the prevalence of IPV in the previous 12 months against GDP per capita (int. $) for all countries, with countries in the region highlighted. It shows a strikingly strong negative relationship between the level of GDP per capita and IPV. The regression results reported in confirm that there is a statistically significant relationship and that it is non-linear in form, with increases in income decreasing IPV at a diminishing rate. Column 1 shows that IPV is lower in countries with smaller gender gaps. Going from Indonesia’s gender gap (G3I) score of 0.697 to that of the Philippines at 0.783 is associated with a decrease in the prevalence of IPV by 4.3 percentage points (48%). This is consistent with better outcomes for women relative to men and with women being empowered outside the home, leading to them being treated with more respect in the home (and possibly having greater intra-household bargaining power). Of course, both variables are correlated with GDP per capita (and likely a host of other variables, including cultural context), so it is not possible to determine whether this is a causal relationship. Column 2 shows the negative non-linear relationship estimated between IPV prevalence and GDP per capita. Column 3 includes GDP per capita, its square and the G3I score as regressors. The inclusion of the GDP per capita variables causes the gender gap score to become insignificant. Hence, it appears that economic growth reduces gender gaps in the domains of economic participation and opportunities, educational attainment, health and survival, and political empowerment, and as it does so, IPV decreases.

FIGURE 10 Prevalence of Intimate Partner Violence in the Previous 12 Months

Note: The black dots are Southeast Asian nations.

Table 2. Intimate Partner Violence, GDP per capita and Gender Equality

That household income reduces IPV is consistent with the findings of research on the effect of cash transfers on IPV. Baranov et al. (Citation2020) conducted a meta-analysis of the effects of cash transfers on IPV in developing countries. The analysis found significant decreases in physical and emotional violence and controlling behaviours associated with the receipt of cash transfers. By examining the differential impacts of cash transfers to women versus cash transfers to men, the study concluded that the evidence is consistent with household resource and stress theory, in which violence arises as a result of stress within the household. Under this theory, increased household income reduces household stress and so lowers IPV.Footnote19 The empirical evidence suggests that household stress theory may operate alongside (but dominate) status inconsistency/backlash theory (in which male partners react violently when their status is threatened by increases in their wives’ income) and/or instrumental theory (in which violence is used to extract monetary transfers from the wife and whereby increases in the wife’s income increase the number of resources the husband may try to extract).

In summary, higher per capita income is definitively associated with reduced violence against women, but the range of experience of nations, particularly at lower income levels, suggests that culture and/or policy settings play an important additional role in the prevalence or otherwise of IPV in any individual country.

IMPACTS OF COVID-19

It is well established that Covid-19 has affected men and women differently across the world, with women often being more adversely affected (Fisseha et al. Citation2021). In Indonesia, the gendered impacts of the pandemic, however, remain somewhat unclear. Many articles have been written claiming that women were more adversely affected, for example, by losing employment, but many of the claims are based on predictions using pre-pandemic data, as they were all that was available at the time (Samudra and Setyonaluri Citation2020; ADB and UN 2022).

A recent World Bank study has taken a careful look at changes in employment over the pandemic period, relative to the trend observed prior to the pandemic (Halim, Hambali and Purnamasari Citation2023). It too is hampered by the lack of recent data—using data up to August 2020 from the National Labour Force Survey (Sakernas)—but found that at that date men were less likely to be employed than before the pandemic (on average by 3%) and that women (other than those aged 19–29 years) were more likely to be employed (by 2.4%). This ‘added-worker effect’ closed the gender gap in employment by 14 %. The data show that women with lower levels of education entered poor-quality jobs and this happened pre-dominantly in rural areas. Tertiary-educated women and men both experienced decreases in employment, by 3.3 and 3.9 percentage points, respectively. Both men and women shifted towards informal employment. Among those working, women’s weekly hours decreased by 2.3 hours and men’s by 2.6 hours. Female workers in the formal sector were more negatively affected than men, with their hours dropping by 4.7 hours compared with 3.2 hours for men. Employed women and men experienced similar declines in their earnings: 16% and 15%, respectively. Miranti, Sulistyaningrum and Mulyaningsih (Citation2022) examine the Sakernas data and find that the gender wage gap narrowed slightly during 2020 and 2021.

Policies put in place to support households in economically difficult times can inadvertently exacerbate gender gaps (Cameron Citation2019). The ADB and the UN (2022), however, report that more Indonesian women reported receiving government support than men since the onset of Covid-19, possibly reflecting Indonesia’s Family Hope Program (PKH), a conditional cash transfer program that targets women.

While women did not seem to experience greater declines in employment during the pandemic, increased work along with school closures and/or parents choosing not to send their children to school for fear of the virus resulted in Indonesian women spending more time on childcare—more than 20% of Indonesian women reported this was the case versus about 12% of men (Samudra and Setyonaluri Citation2020). Further, a World Bank survey in mid-2020 found that about 12% of Indonesian households reported that mothers had to sacrifice productive work to support their children because schools were closed (World Bank Citation2022). Hence, women were increasingly shouldering the double burden of work and family responsibilities, which may worsen both their physical and mental health and reduce their wellbeing. UNICEF et al. (2021) found that this was true early in the pandemic with 19.7% of female household heads reporting feeling unhappier, more stressed or more depressed, compared with 16.8% of male household heads.

As discussed, higher stress levels within households are associated with a higher prevalence of family violence. The number of domestic cases reported and documented by Komnas Perempuan increased.Footnote20 Further, a World Bank phone survey of women in migrant communities in Indonesia found that the pandemic increased the perceived risks of violence, with food insecurity being one of the strongest contributors to this increased risk (Perova and Halim Citation2020).

There also appears to have been gender gaps in learning losses in Indonesia, which favoured boys (ADB 2022). That girls’ learning suffered relative to boys during the pandemic is projected to result in future earnings losses that are more than 20% higher for girls than boys. Hence, while the gender wage gap appears to have narrowed during the pandemic, it may feed into larger future gender wage gaps.

Finally, there is evidence to suggest that the pandemic affected health outcomes differentially by gender. Unlike in many countries, in Indonesia women were slightly more likely to get two shots of a Covid vaccine than men (UN 2022). However, World Bank (Citation2022) found that between 13% and 16% of households that sought family planning services from November 2020 to March 2021 could not access them (Miranti, Sulistyaningrum and Mulyaningsih Citation2022).

CONCLUSIONS

Indonesia is a middling performer in terms of global gender inequality. It is doing better than many other countries, with considerable potential for improvement in the opportunities Indonesian women have to fully participate in society. Indonesia performs well in terms of gender gaps in educational attainment, and health and survival. Its performance in terms of women’s political empowerment is middle of the range. Where it underperforms substantially, and where there is considerable room for policies to improve the situation, is in women’s economic participation. The labour force participation of Indonesian women has been stuck at just over 50% for several decades. This is reflected in the very low share of earned income accruing to women. Increasing women’s labour force participation is likely not only to improve women’s economic position but to empower women more broadly. Working is empowering for women both outside the home, and inside the home, where a greater share of household income being earned by the woman is associated with lower rates of family violence. Increasing women’s labour force participation also pays economic dividends and so spurs further economic gains for all.Footnote21

As discussed, policies such as the provision of childcare and flexible work arrangements are likely to increase women’s labour force participation by making it easier for women to work while accommodating family responsibilities. Social norms that cement mothers as the main caregiver in the family also need to be tackled in order to see significant increases in the number of women working. Campaigns that seek to challenge the social norm of women as the main caregiver are likely to be a powerful and necessary element of any successful government push to tackle this issue. This need not mean that mothers relinquish their central role in the family, but that greater sharing of household responsibilities with husbands is an acceptable option. The effectiveness of public information campaigns is likely to be enhanced by the acknowledgement of the cultural diversity of Indonesia and by campaigns being designed to reflect the dominant cultural norms of the specific areas targeted.

In Indonesia, as elsewhere, Covid-19 has presented specific challenges for women. Women have taken on more low-quality employment. At the same time, their domestic responsibilities increased to a greater extent than men’s. A concerted effort by government and civil society, most notably employers and business leaders, is needed to ensure that Indonesian women can access the economic opportunities that are their due.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I would like to thank the Indonesia Project at the Australian National University and the Institute for Economic and Social Research (LPEM) at the University of Indonesia for the invitation to present the Sadli lecture. Thanks also go to Firman Witoelar for his advice and input and to my coauthors on my research papers on gender in Indonesia, on which I have drawn for the lecture; most particularly Diana Contreras Suarez of the University of Melbourne and Diahhadi Setyonaluri of the University of Indonesia. I also thank Chris Manning, Putu Natih, Asep Suryahadi, Ross McLeod and an anonymous referee for their comments on the paper. I thank Sean Muir for his copy-editing, and Alex Gotts for assisting with an associated op-ed piece. I further thank Teguh Dartanto and Mayling Oey-Gardiner for their support and remarks at the lecture. Finally, I would like to pay my respects to Professor Dr. Saparinah Sadli, whose work on gender in Indonesia is the inspiration for this paper.

Notes

2 As catalogued by EconLit.

3 For technical details on how the index is constructed, see World Economic Forum (Citation2022).

4 Sourced from the World Bank at https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.PP.CD.

5 If Middle Eastern countries (which are culturally distinct and have relatively high incomes and low gender equality scores) are excluded, the coefficient increases such that an int. $10,000 increase is associated with a 2.3% increase in the G3I.

6 Rwanda, Nicaragua, Namibia, the Philippines and Burundi all have per capita incomes below int. $10,000 and G3I scores above 0.77.

7 The indicator of wage equality for similar work is based on responses to the following question in the World Economic Forum’s Executive Opinion Survey: ‘In your country, for similar work, to what extent are wages for women equal to those for men?’. Responses can range from 1 = not at all, significantly below those of men; to 7 = fully, equal to those of men. The measure is thus not comparable to the more commonly cited gender gap measures that are calculated as the ratio of women’s hourly wages or monthly earnings to men’s.

8 The methodology used by the World Economic Forum is an adaptation of that used by the United Nations Development Programme to calculate its Gender Development Index. It uses information on the female share of the economically active population, from the International Labour Organization (ILO), which for Indonesia is based on data from the National Labour Force Survey (Sakernas); information on the ratio of female-to-male wages, from the ILO, which for Indonesia is based on monthly earnings data from Sakernas; GDP data, from the International Monetary Fund; and information on female and male shares of the population, from the World Bank. As a result, this measure is not directly comparable to commonly cited gender pay gaps for Indonesia calculated from the ratio of women’s hourly wages or monthly income to men’s—for example, a gender pay gap of around 18% estimated by the ILO (2018)—and a gap of 30% estimated in an ADB working paper (Taniguchi and Tuwo Citation2014). For more details on the methodology for calculating the measure of the share of earned income, see the gender gap report by the World Economic Forum (Citation2022).

9 Female labour force participation in Indonesia increased slightly from 52% to 54% between 2017 and 2019 but returned to 52% in 2021. See the modelled ILO estimates: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SL.TLF.CACT.FE.ZS?locations=ID

10 Any such trend is likely to differ across differing cultural groups, particularly given the increasing influence of more conservative forms of Islam in some settings.

11 The effect of such provisions on demand for female labour is unclear. To the extent that employers bear the costs of such arrangements, the demand for female labour may be negatively affected. However, if such policies lead to employers being more confident that women will continue in employment after they have children, the policies would have a positive effect on demand for female labour (Olivetti and Petrongolo Citation2017).

12 Author’s calculations using the 2016 Sakernas. More generally, women’s labour force participation across different regions of Indonesia does not vary uniformly with the pre-dominant religion in the regions and likely reflects a variety of economic and cultural factors. This is an area worthy of future research.

13 These data are from an online survey of 1,050 respondents (50% male, 50% female) collected for research by Cameron, Contreras Suarez and Setyonaluri (2023). Respondents resided in metropolitan areas across Indonesia, were 18–40 years old, had at least a junior secondary school education, were married with at least one child aged under 18 years and lived with their spouse. All respondents, whether they reported being supportive or not of women working for pay outside the home were asked to ‘indicate up to three main reasons you do not support married women with children under 12 working for pay outside the home’. They then selected from the range of options provided, as shown in , including ‘other’ and ‘I don’t agree with any of the reasons given’.

14 Appendix B provides a brief overview of related randomised trials.

15 See footnote 13 for more details on the sample.

16 Less than 10% of women aged 40–60 years disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement ‘When a mother works for pay, the children suffer’.

17 See https://www.publichealth.com.ng/united-nations-definition-of-gender-inequality/. Violence against women is any act of gender-based violence that results in physical, sexual or mental harm or suffering to women. IPV refers to any violence between partners in an intimate relationship. Domestic violence and family violence are often used synonymously with IPV but can also encompass child or elder abuse by any member of a household.

19 However, the stress experienced by women could increase if married women are expected to spend more hours in paid employment without adequate childcare support and/or without husbands and other household members sharing household responsibilities. Increased stress experienced by women may, however, not result in increases in domestic violence as women are rarely the main perpetrators.

21 Australia Indonesia Partnership for Economic Governance (AIPEG), as cited at http://www.bbc.com/indonesia/indonesia-42428508.

REFERENCES

- ADB (Asian Development Bank). 2022. Falling Further Behind: The Cost of Covid-19 School Closures by Gender and Wealth. ADB: Manila. https://www.adb.org/sites/default/files/publication/784041/ado2022-learning-losses.pdf

- ADB (Asian Development Bank) and UN (United Nations). 2022. Two Years on: The Lingering Gendered Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Asia and the Pacific. ADB: Manila.

- Alesina, Alberto, Paola Giuliano and Nathan Nunn. 2013. ‘On the Origins of Gender Roles: Women and the Plough’. Quarterly Journal of Economics 128 (2): 469–530. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjt005

- Aloud, Monira E., Sara Al-Rashood, Ina Ganguli and Basit Zafar. 2020. ‘Information and Social Norms: Experimental Evidence on the Labor Market Aspirations of Saudi Women’. Working Paper 26693, National Bureau of Economic Research, December.

- Baranov, Victoria, Lisa Cameron, Diana Contreras Suarez and Claire Thibout. 2020. ‘Theoretical Underpinnings and Meta-analysis of the Effects of Cash Transfers on Intimate Partner Violence in Low- and Middle-Income Countries’. Journal of Development Studies 57 (1): 1–25.

- Bertrand, Marianne, Emir Kamenica and Jessica Pan. 2015. ‘Gender Identity and Relative Income within Households’. Quarterly Journal of Economics 130 (2): 571–614. doi: 10.1093/qje/qjv001

- Bursztyn, Leonardo, Alessandra González and David Yanagizawa-Drott. 2020. ‘Misperceived Social Norms: Women Working Outside the Home in Saudi Arabia’. American Economic Review 110 (10): 2997–3029. doi: 10.1257/aer.20180975

- Cameron, Lisa. 2019. ‘Social Protection for Women in Developing Countries’. IZA World of Labour. https://wol.iza.org/articles/social-protection-programs-for-women-in-developing-countries/long

- Cameron, Lisa and Diana Contreras Suarez. 2017. Women’s Economic Participation in Indonesia: A Study of Gender Inequality in Employment, Entrepreneurship and Key Enablers for Change. Australian Indonesian Partnership for Economic Governance (AIPEG).

- Cameron, Lisa, Diana Contreras Suarez and Yi-Ping Tseng. 2023. ‘Women’s Transitions in the Labour Market as a Result of Childbearing: The Challenges of Formal Sector Employment in Indonesia’. Working Paper 06/23, Melbourne Institute, University of Melbourne.

- Cameron, Lisa, Diana Contreras Suarez and William Rowell. 2019. ‘Female Labour Force Participation in Indonesia: Why Has It Stalled?’. Bulletin of Indonesia Economic Studies 55 (2):157–92. doi: 10.1080/00074918.2018.1530727

- Cameron, Lisa, Diana Contreras Suarez and Diahhadi Setyonaluri. 2023. Changing Gender Norms around Women’s Work in Indonesia: Evidence from an Online Intervention. Mimeo, University of Melbourne.

- Dean, Joshua T. and Seema Jayachandran. 2019. ‘Changing Family Attitudes to Promote Female Employment’. AEA Papers and Proceedings 109 (May): 138–42. doi: 10.1257/pandp.20191074

- Fernández, Raquel. 2013. ‘Cultural Change as Learning: The Evolution of Female Labor Force Participation over a Century’. American Economic Review 103 (1): 472–500. doi: 10.1257/aer.103.1.472

- Fisseha, Senait, Gita Sen, Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Winnie Byanyima, Debora Diniz, Henrietta H. Fore, Natalia Kanem et al. 2021. ‘Covid-19: The Turning Point for Gender Inequality’. The Lancet 398 (10299): 471–74. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01651-2

- Halim, Daniel, Sean Hambali and Ririn Purnamasari. 2023. ‘Not All That It Seems: Narrowing of Gender Gaps in Employment during the Onset of Covid-19 in Indonesia’. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 10337.

- Halim, Daniel, Hillary Johnson and Elizaveta Perova. 2017. ‘Could Childcare Services Improve Women’s Labor Market Outcomes in Indonesia?’. Policy Brief Issue 1, East Asia and Pacific Gender series, World Bank, Washington, DC, March.

- ILO (International Labour Organisation). 2018. Global Wage Report 2018/19. What Lies behind Gender Pay Gaps. Geneva: ILO.

- Jayachandran, Seema. 2021. ‘Social Norms as a Barrier to Women’s Employment in Developing Countries’. IMF Economic Review 69 (3): 576–95. doi: 10.1057/s41308-021-00140-w

- McKelway, Madeline. 2021. ‘The Empowerment Effects of Women’s Employment: Experimental Evidence’. Working paper, 13 March.

- Miranti, Riyana, Eny Sulistyaningrum and Tri Mulyaningsih. 2022. ‘Women’s Roles in the Indonesian Economy during the Covid-19 Pandemic: Understanding the Challenges and Opportunities’. Bulletin of Indonesian Economic Studies 58 (2): 109–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/00074918.2022.2105681

- Olivetti, Claudia and Barbara Petrongolo. 2017. ‘The Economic Consequences of Family Policies: Lessons from a Century of Legislation in High-Income Countries’. Journal of Economic Perspectives 31(1): 205–30. doi: 10.1257/jep.31.1.205

- Perova, Elizaveta and Daniel Halim. 2020. What Factors Exacerbate and Mitigate the Risk of Gender-Based Violence during Covid-19? Insights from a Phone Survey in Indonesia. East Asia and Pacific Gender series, World Bank, Washington, DC, December.

- Samudra, Rachmat Reksa and Diahhadi Setyonaluri. 2020. Inequitable Impact of Covid-19 in Indonesia: Evidence and Policy Response. Jakarta: United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO).

- Schaner, Simone and Smita Das. 2016. ‘Female Labour Force Participation in Asia: Indonesia Country Study’. ADB Economics Working Paper 474, February.

- Setyonaluri, Diahhadi. 2013. ‘Women Interrupted: Determinants of Women’s Employment Exit and Return in Indonesia’. PhD thesis, Australian National University, Canberra, February.

- Utomo, Ariane. 2018. ‘Revisiting the Trends of Female Labour Force Participation in Indonesia’. Jurnal Perempuan 23 (4): 193–202. doi: 10.34309/jp.v23i4.274

- Taniguchi, Kiyoshi and Alika Tuwo. 2014. ‘New Evidence on the Gender Wage Gap in Indonesia’. ADB Economics Working Paper 404, September.

- UN (United Nations). 2022. Two Years On: The Lingering Gendered Effects of the Covid-19 Pandemic in Asia and the Pacific. Manila: ADB and UN Women.

- World Bank. 2022. ‘Indonesia High-Frequency Monitoring of Covid-19 Impacts’. Round 2, 26 May–5 June 2020. Presentation, World Bank, Jakarta. https://thedocs.worldbank.org/en/doc/763981610628173104-0070022021/original/IndonesiaCOVIDHiFyR2.pdf

- World Economic Forum. 2022. Global Gender Gap Report 2022: Insight Report. July 2022. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2021. Violence against Women Prevalence Estimates, 2018: Global, Regional and National Prevalence Estimates for Intimate Partner Violence against Women and Global and Regional Prevalence Estimates for Non-partner Sexual Violence against Women. Geneva: WHO.

APPENDIX A

TABLE A1 Data Used in the Analysis

APPENDIX B

Related Literature on Influencing Social Norms

Aloud et al. (Citation2020) took a similar approach to Bursztyn, González and Yanagizawa-Drott (2020). They provided a subset of female university students in Saudi Arabia with information on the labour market aspirations of their female peers. Information on the high labour market aspirations of their female peers increased participants’ expectations about their own labour force participation.

Two other randomised trials found no effects on gender norms of interventions that sought to change people’s attitudes towards women working by providing information on the monetary and non-monetary benefits that accrue from women working. McKelway (Citation2021) conducted a randomised trial in India, in which in treatment households, women’s husbands and in-laws were shown a video promoting a female employment opportunity with testimonials from program supervisors, female employees and the husband of an employee. The promotional video was designed to raise household’s awareness about women’s earning potential. It seemed to do this and also had a positive impact on women’s empowerment, but there were no effects on women’s or family members’ views about the appropriateness of women working outside the home.

In another randomised trial in India, Dean and Jayachandran (Citation2019) evaluated low-cost interventions to examine impacts on retention of female kindergarten teachers in India. One consisted of showing teachers’ family members videos that highlighted the non-monetary benefits of employment (for example, personal growth) and addressed common concerns around women working (mostly to do with safety). The idea was that family members would be more supportive of the female family member working if they heard about the personal growth it confers and understood more about what the jobs (in this case kindergarten teaching) involve. The other intervention consisted of mediated conversations between teachers and the family members of the woman about the pros and cons of her working. No significant treatment effects were detected and there was no increase in the support for women’s employment.