Abstract

The longevity of enterprises has long been an important area of research for business historians and management scholars. Nevertheless, little research has been directed towards what enables some firms to survive in a declining industry. In this article, following the new entrepreneurial history approach, we focus on Nihonsakari, a Japanese sake brewer founded in 1889, in order to analyse the concrete processes that enabled it to survive as the sake industry declined since the 1970s. We argue that the core feature propelling its longevity was the persistent co-creation processes among stakeholders that made diversification possible.

1. Introduction

This study is driven by one fundamental question: Why do some enterprises achieve longevity? According to economic theory, in the long term, the market reaches equilibrium so no enterprise can consistently earn above-average returns (Hogarth et al., Citation1991). Moreover, industries can also be out of equilibrium (Nelson & Winter, Citation1982). Business schools publish new books and theories constantly to teach managers how to achieve longevity, yet even the cases mentioned in these publications sometimes face bankruptcy soon after publication (Collins & Porras, Citation2005). In Japan, according to the Teikoku Data Bank, there are 33,259 companies dispersed in various industries that have survived for more than 100 years (TDB, Citation2019). Most of them are small family businesses that have been deeply rooted in the local community for generations (Motoya, Citation2004). These firms have not received much international scholarly attention. Among the major sectors is sake brewing (2.4% of all firms over 100 years old), the focus of the current study.

Sake is a traditional alcoholic drink made from rice that has been in production since the 8th century and dominated the alcohol market in Japan until the mid-20th century. It played a major role in the economy during the Meiji period when the tax from alcohol surpassed that from land, and alcohol was the highest source of tax income for the government (JNTA, Citation2019). Today, this important economic function has been replaced by modern high-tech industries, such as the automobile and appliance industries. The modernisation of Japan in the late 19th century brought not only modern production but also changes to Japanese people’s everyday consumption (Francks & Hunter, Citation2012). Traditional goods (such as sake) became branded goods that were mass-produced and marketed with modern techniques to meet growing demand from the urban middle classes. However, the availability of a broader range of goods and shifts to new patterns of work and social life impacted the consumption of indigenous goods (Francks, Citation2009). According to the latest data published by the Japanese National Tax Agency in 2019, the consumption of sake, which had reached a peak in the 1970s, dropped to less than one-third of its peak by 2019 (JNTA, Citation2019).

Moreover, the change was not limited to new products: the industry reorganised. The rise of large modern enterprises in the beer industry changed the structure of the alcohol industry. The alcohol market once dominated by sake was largely taken over by beer after World War II. The pre-war consumption of sake accounted for 71% of all alcoholic beverages combined, with beer accounting for 16% (Alexander, Citation2013). In 1959, the share of beer reached 44% while sake fell to 29% (Alexander, Citation2013, p. 181); 40 years later, in 1999, beer’s share was five times larger than that of sake (JNTA, Citation2010). These new firms established themselves as dominant actors in this sector (Craig, Citation1996). The four largest companies controlled 99.9% of the beer market in 2019 (NSN, Citation2020). By contrast, of the 1,378 firms in the sake industry, the largest 11 firms combined have only a 43.7% market share (JNTA, Citation2018). However, more than half of these sake brewers (801 firms) are companies over 100 years old (TDB, Citation2019), and most of these are family businesses with a strong sense of social responsibility towards conserving traditional Japanese sake. The survival of these companies in a declining industry is consequently a major challenge that has not been analysed thoroughly. Hence, the main research question addressed by this study is: How did small family firms in the sake brewing industry adapt to a declining industry?

2. Literature review

The issue of firms’ longevity has become a puzzle for researchers in a broad range of social science disciplines. shows the common explanations regarding firms’ ability to achieve longevity based on the bibliometric research by Riviezzo et al. (Citation2015) and our own literature review. International scholars emphasise a wide variety of factors related to the firm’s environment, organisation, specificities of their industry, personal characteristics of the entrepreneurs involved and succession planning. Thus, longevity is arguably a comprehensive phenomenon that results from the interactions of all the internal and external factors that have been highlighted, so focussing on a single element can distort understanding of the conditions that propel firm longevity. Napolitano et al. (Citation2015) propose Porter’s (Citation2004) ‘consolidated approach to a competitive environment’ to integrate both the external and internal factors to analyse firm longevity systematically. Therefore, this paper builds on the literature in business history to contribute to knowledge on the longevity of Japanese family firms.

Table 1. Main focus and key findings in social science research on firm longevity.

Japan has the largest number of long-lasting firms in the world; 98.3% of them are small businesses with a revenue of less than USD 500 million in 2019 (TDB, Citation2019). However, the international literature outlined in barely addresses Japanese firms, as most of the research is based on Western cases. One rare exception is the work of Sasaki and Sone (Citation2015), who argue that the continuity of both local and corporate cultures propel firms’ longevity. However, their research only emphasises the cultural factor, with little reference to organisation and management. Moreover, they do not offer any financial data, so the conditions of longevity are largely unknown. Although long-lasting Japanese firms are rarely discussed in the international literature, a broad range of books—much more than articles—published in the Japanese language deals with this topic. Researchers have approached the phenomenon of long-lasting Japanese family firms by asking different research questions.

First, some scholars concentrate their studies on explaining why Japan has so many long-standing family firms. They insist on the major role of unique sociocultural factors, such as tradition, family business ethics, family precepts, family business separation and succession practices (Adachi, Citation1974; Komatsu, Citation1975). They found that 80% of the long-lasting firms were born during the Meiji period (1868–1912), a time when Japan was reforming to defend itself from the threat of Western countries. The formation of new companies boomed as a result of the Meiji government’s industry promotion policies (Shokusan kōgyō). The concept of coexisting with one’s community and with nature is quite strong among these firms (Ōnishi, Citation2013). The family precept that functions as the main principle of operation mostly sets ancestor worship, family business permanency and clan unity as the firm’s strategic goals (Maekawa, Citation2015). In the case of the absence of a son or any talented heirs, the owner adopts a son without any family blood ties to keep the ancestor’s family name alive and continue the family business (Mehrotra et al., Citation2013). Similarly, management scholars demonstrate that these long-standing firms continuously concentrate on a particular local region since their foundation. These firms have a distinguished value preference for survival and longevity over short-term profit maximisation (Goto, Citation2013) and are very cautious about expanding beyond their main business (Iwasaki & Kanda, Citation1996; Motoya, Citation2004). Scholars attribute longevity to maintaining long-term relationships with the local community, passing on core techniques to successors, and preserving a good brand name generation after generation (Katō, Citation2008). These studies contribute to our understanding of the sociocultural contexts of long-lasting firms in Japan. However, they cannot explain why some family businesses last longer, while others fail in the same sociocultural contexts with the same practices.

Second, since 2000, the number of bankruptcies of long-lasted firms in Japan has increased significantly, from 221 in 2000 to 579 in 2019 (TDB, Citation2020). Scholars subsequently showed more interest in researching why some long-lasting family firms last longer than others in the same sociocultural contexts. Specifically, they focussed on innovation and the role of entrepreneurs to explain the source of dynamism that propels firm longevity. For example, Kobayashi (Citation2011) demonstrates how the first generation of Kumayoshi business owners innovated and transformed the traditional industry of Yamanaka lacquerware into a modern company. He highlights the difficulties in the innovation and transformation process and asserts that the CEO’s ambition, novelty and leadership propel firm longevity. Gomi (Citation2020) examines a long-lasting family firm’s transformation from traditional craft-gold leaf manufacturing to global industrial product manufacturing. His analysis focuses on the CEO’s ‘wise choices’, strong beliefs, unyielding will, proactiveness, innovativeness and challenging spirit. Similarly, other scholars demonstrate the extraordinary product, market and organisation innovations from CEOs who drive their firms’ longevity in the face of various crises (Maruyama, Citation2017; Ono, Citation2018). In contrast to early studies that emphasised the social and cultural contexts, these recent works analyse the impact of external historical changes and the internal responses from entrepreneurs. However, while these CEOs play a role in transforming their firms, they are part of a more complex co-creation process that involves multiple roles in Japanese culture and society. Therefore, the focus on innovations by individual entrepreneurs distracts from understanding the core element that supports the longevity of long-lasting family firms in Japan. There is a need to go beyond the common narrative about the genius CEO. Further, studies on innovations of long-lasting Japanese firms do not provide any financial data. At present, the impact of innovation on firms’ evolution and the extent to which entrepreneurs have brought about change remains unclear.

3. Research design and data selection

The tremendous change of the external environment in declining industries is a major challenge to ensuring small family firms’ longevity. They need to find a balance between preserving and reinventing their business, which requires a great deal of unexpected creativity (Washida, Citation2014). Hence, we use the new entrepreneurial history approach advocated by Wadhwani and Lubinski (Citation2017) to study the interaction between entrepreneurial processes and historical change that enables the longevity of firms. Instead of putting genius CEO and their personal innovations at the centre of the study, this approach provides a framework to examine co-creation entrepreneurial processes among multiple actors over time to propel economic change. In particular, it focuses on three distinct entrepreneurial processes: envisioning and valuing opportunities, allocating and reconfiguring resources, and legitimising novelty. To date, this approach has not been applied to reconsider the survival of firms in traditional industries. Therefore, this paper is an exploratory study that aims to demonstrate the analytical potential the new entrepreneurial history approach offers.

We focus on one major firm in the Japanese sake industry and investigate the ‘creative response’ from the family business to understand how small family firms in the sake brewing industry could adapt to a declining environment and maintain their existence. We have selected Nihonsakari for the following reasons. First, this company was an early mover in diversifying from sake to cosmetics, a strategy that later became an industry benchmark. However, the processes that enabled this first diversification remain unclear. Second, although Nihonsakari was not among the oldest firms in the sake industry, it was founded in 1889 and experienced almost one century of fast development as a specialised sake brewer, establishing it as one of the leading firms in this business before facing the decline of consumption in the 1970s. Hence, it can be considered a traditional family enterprise that had to struggle to ensure its survival. Although there were hundreds of small sake brewers in Japan, the choice of one of the largest among them and a first mover in diversification is relevant to discuss the entrepreneurial processes that made possible its survival. One of the objectives of this work is to offer a new way to analyse long-standing family firms in Japan and attract further research using this perspective.

Specifically, we start by identifying the historical environmental change and main transformations that drove the firm’s business longevity using historical data over an extended period. Next, we examine the core processes of envisioning and valuing opportunities, allocating and reconfiguring resources, and legitimising novelty connected with the change. As Nihonsakari did not give access to primary sources and refused interviews with the CEO, the material used for this research consist of published sources. We used financial data disclosed in the annual directories of unlisted companies published by Nikkei (Citation1978–2005) and Tōyō Keizai (Citation2006–2020). The data allowed us to analyse the evolution of sales and profits in detail and measure the impact of entrepreneurial processes on the company’s development. Qualitative data on the company’s activities and attempts to innovate were mainly obtained from news magazines and business newspapers published by the Nikkei group since 1975 (https://t21.nikkei.co.jp). We also used the company’s website (https://www.nihonsakari.co.jp) and corporate history published in 1989 for this purpose. Finally, data on sake consumption and the number of sake brewers since 1945 are from the National Tax Agency.

4. A sake brewer in a declining industry

Nihonsakari was founded in 1889, with the name Nishinomiya Sake Brewer (NSB; brand name Nihonsakari), in the sake brewing industrial district of Nishinomiya, Kobe city. It was led by a group of young entrepreneurs who raised capital from a broad range of investors to build a modern corporation with high productivity (Nihonsakari, Citation1989, pp. 27–39). Hence, the firm was founded as a joint stock company, an organisational form that was uncommon in sake brewing initially but later became widespread (Nihonsakari, Citation1989, pp. 33, 83). Although the company usually states that it is not a family business and all shares were distributed to business partners and employees (Nihonsakari, Citation1989, p. 174), it was indeed controlled and managed by the Morimoto family since its foundation and followed the primogenitor inheritance custom (Nihonsakari, Citation1989, pp. 35, 295, 350, 498). The president of the board in 2020 is an adopted son from the Morimoto family and succeeded his father, who had been president for 31 years (Okamoto, Citation2020).

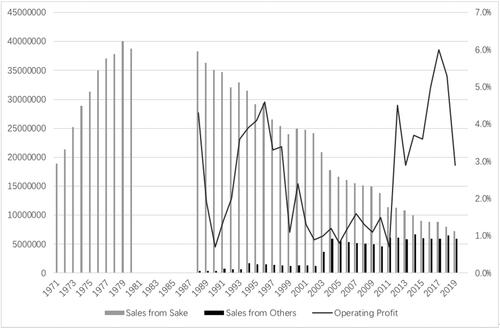

In 1910, NSB became the largest sake company in Japan in terms of production volume (4,454 kL) but had only a 0.64% share of the national market (Nihonsakari, Citation1989, p. 97). Production continued to grow until it peaked at 73,295 kL in 1978, at which time it had a market share of 4.7% (Nihonsakari, Citation1989, p. 482). However, like other sake companies, it was severely hit by changing consumption habits and a decline in the domestic market from the 1970s. In 2017, it was still the eighth largest producer of sake with a market share of 3%, but production volume had dropped to 15,637 kL (TDB, Citation2017; Ide, Citation2019). The company’s revenues and profits followed a similar trend to production (see ). Available data (1981–1985 revenue is unknown) makes it possible to estimate a revenue peak of around JPY 40 billion in 1979, dropping steadily to JPY 13 billion in 2019.

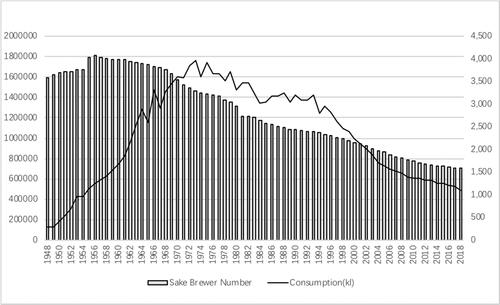

The decline experienced by NSB expresses the general evolution of the sake industry. In the 1970s, the Japanese alcohol market experienced a deep mutation that significantly impacted the competitiveness of sake brewers. The introduction and growth of other alcohols (beer, wine and whisky) attracted more consumers, especially the younger generation, while sake had the image of a drink for older men (Sumihara, Citation2004). Consequently, the consumption of sake, which had experienced rapid growth after World War II, reached a peak of 1.8 million kL in 1973 and started to decline dramatically. It dropped below 0.487 million kL and was only one-third of the level in the early 1970s in 2019 (see ). Since the 1990s, sake brewers and the Japanese government have tried to address this challenge by expanding foreign sales, but the export volume has increased extremely slowly (JNTA, Citation2017). In 2018, it amounted to 0.0257 million kL, which is only 5% of the total sake consumption (JNTA, Citation2019). In this context, many sake brewers were forced out of business each year. The number of companies started to fall in the mid-1950s, as the growing demand led companies to merge and invest massively in production technology. The decline accelerated after 1970, and the number of brewers went from more than 3,500 in 1970 to 2,152 in 2000 and 1,580 in 2018 (see ). Between 1970 and 2018, more than half of all sake brewers disappeared.

Figure 1. Sake Consumption (kL) and number of sake brewers, 1948–2018.

Source: JNTA (Citation2019)

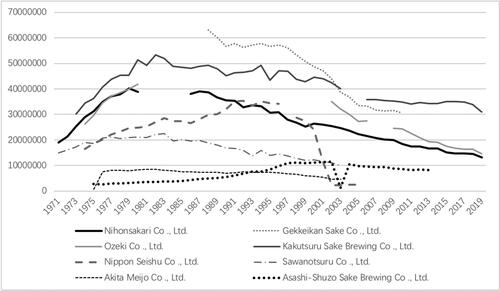

Therefore, the decline of sales experienced by NSB since the 1980s is far from unique. Indeed, all the major sake brewers in Japan faced a similar trend, as shown in . Under these conditions, the actions taken by the sake brewers need to be examined, as most were long-lasting small companies. Scholars have mainly investigated the strategies of utilising traditional craftsmanship and history to create high-quality sake or expand to foreign markets. For example, Sumihara (Citation2004) studied the various strategies adopted by sake business owners, which included reviving traditional brewing methods and conquering the overseas market; the study highlighted tradition as an element in branding to differentiate sake quality as a solution to the crisis of the Japanese sake industry. Lee and Shin (Citation2015) examined the marketing strategy used by a sake brewery located in the Nara Prefecture to produce high-quality sake based on the storytelling of Kida Brewery’s 300 years of history and tradition. These studies described various strategies to expand sake sales but provided no financial data or analysis to demonstrate the connections between the strategies and any economic change; therefore, a proper evaluation of these actions is difficult (Wadhwani et al., Citation2020). Thus, the next section discusses co-creation processes in relation to economic change in the case of NSB.

Figure 2. Gross sales of major sake companies, in 1,000 yen, 1971-2019.

Source: Kaisha sōkan (unlisted) (Nikkei, Citation1978–2005) and Kaisha shikibō (Tōyō Keizai, 2005–2020)

Based on the Nikkei database (https://t21.nikkei.co.jp), we identified 167 articles related to NBS/Nihonsakari published between 1975 and 2020 in the major business newspapers Nihon Keizai Shimbun (NKS), Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun (NSS) and Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun (NRS). The variety of innovations, as expressed by these sources, shows that most actions can be described as sake product innovations relating to production, packaging, image and price (103), sake distribution channels (14), sake market innovations (7), industrial collaboration on sake (9) and sake-related business model innovations (2). Outside of sake itself, the most important innovations occurred in sake by-products such as cosmetics and food (32). The breakdown of these innovations over time shows three distinct periods.

First, in 1975–1988, NSB focussed on innovation purely related to sake. This included developing new sake consumers, especially from younger generations (NSS, Citation1979b), entering the second-level sake market (the market was regulated only for smaller sake makers before 1983) (NSS, Citation1979a, Citation1986c), and expanding distribution networks to sushi restaurants and sake bars in the main cities (NRS, Citation1987). To boost sake sales among the younger generation, NSB invented new public relations channels (young people’s journals) (NSS, Citation1979b), new tastes (low-alcohol sake, carbonated sake, wine-like sake) (NSS, Citation1985a, Citation1985b; NRS, Citation1986) and fashionable packaging (Western bar-style black bottles, PET containers, paper containers) (NSS, Citation1987a; NSS, Citation1986a, Citation1986b). The sales from non-sake business grew from zero in the early 1970s to JPY 0.3 billion in 1988, while sake sales were in decline (JPY 39 billion in 1988). However, the diversification was very limited. Non-sake sales represented only 1% of the total sales in 1988 (see ).

Figure 3. Nihonsakari, gross sales, in 1,000 yen, 1971–2019.

Source: Kaisha sōkan (unlisted) (Nikkei, Citation1978–2005) and Kaisha shikibō (Tōyō Keizai, 2005–2020)

Note: no data available between 1981 and 1987

Second, the years 1988–2000 were a trial period during which the company ventured to diversify its business into cosmetics to a limited extent to gauge the market response. NSB launched a few new products related to the main business, such as rice bran cleanser, shampoo, cream, body treatment and makeup remover (NRS, Citation1988; NSS, Citation1990, Citation1992b; NRS, Citation1995b). However, the focus of innovation was still clearly sake. The company made efforts to change the unhealthy image of sake and targeted new types of customers such as women (NSS, Citation1992a). It developed ‘healthy sake’ (vitamin-rich sake, sake ‘good for the liver’, sweet sake and low-sugar sake) (NSS, Citation1992c; NHS, Citation1995; NRS, Citation1995a; NRS, Citation1996a; NSS, Citation1998a), new packages with different sizes (can, ultraviolet cut bottle and cup) (NRS, Citation1996b; NKS, Citation1996; NSS, Citation1997a, Citation1997b, 1998), and expanded its distribution channels to convenience stores (NSS, Citation1995; NKS, Citation1995) to explore the mass market. During this period, the sake business still accounted for around 95% of total revenue. The non-sake sales rose slowly from JPY 0.3 billion in 1988 to JPY 1.4 billion in 2000, while sake sales fell to JPY 25 billion in 2000.

Third, since 2000, the company has strengthened its diversification into natural cosmetics and health food. The company president announced a change of the company name to its brand name Nihonsakari in 2000 (NSS, Citation2000). By 2020, the company had 61 cosmetic products (seven series of natural cosmetics), 11 beauty supplement products and 34 types of food products sold on its official website (Nihonsakari, Citation2020). Strong diversification has been realised. The sales from the non-sake business grew to JPY 6 billion in 2019, mainly from its diversified products, such as cosmetics and food, representing nearly half of the total sales that year. However, Nihonsakari did not relent on innovation related to sake. Examples of actions include the exploration of foreign markets (NKS, Citation2013c), expansion of distribution routes to the most crowded subway stations, buildings and convenience stores (NKS, Citation2013b; NKS, Citation2015), development of sake products and convenient packages for modern lifestyles such as ‘paper cup sake’ (NKS, Citation2011c) and ‘bottle can sake’ (NMRS, Citation2015). In addition, it collaborated with other sake companies to build unified sake brands to reduce industry competition and enhance competitiveness (NKS, Citation2011a, Citation2011b, Citation2013a). Nevertheless, the sake sales fell from JPY 25 billion in 2000 to only JPY 7.2 billion in 2019. Despite this continuous decline of the original business, diversification positively impacted the firm’s finances. While the operating profit had been in decline since 1996, averaging 1.1% in the period 2000–2011, the trend started to change. In the period 2012–2019, the average profit was 4.2%.

5. Examining nihonsakari’s creative response from a new entrepreneurial history approach

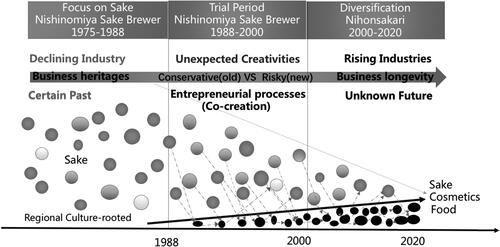

How can we explain the successful diversification of Nihonsakari since 2000? Conventionally, business historians and management scholars have sought to explain such success with reference to the CEO’s vision, strategy and innovative action. This is mainly how the literature explains entrepreneurship supporting the longevity of Japanese firms (see Section 3). To avoid simplistic explanations, this section uses the model of new entrepreneurial history proposed by Wadhwani and Lubinski (Citation2017) to discuss how Nihonsakari could adapt to a declining industry and develop new businesses. shows the evolution of Nihonsakari since 1975 in the context of a declining industry (sake) and the creative responses to this change. The accumulated resources of Nihonsakari were solely related to sake and had become inadequate to provide sufficient revenues in the 1980s. However, innovation is not a linear process. The whole response process somehow involves mainly conflicts, struggles, failures in wandering between the safe zone of its sake business and exploration of an unknown future. Wadhwani and Lubinski (Citation2017) argue that the transformation of old resources (in this case, from the declining sake brewery) into new resources (the diversification to cosmetics and food) is the core process connecting innovation with economic change. We focus below on the example of the development of natural cosmetics, which is a significant business developed by Nihonsakari. Major innovations are outlined in . Importantly, this innovation occurred in a favourable context, as the fast development of the global cosmetic market ($25 billion in 1982 and $382 billion in 2010) led to growing scepticism about the safety of the chemical ingredients used in their production. Hence, manufacturers started to develop natural cosmetics in the 1950s and 1970s (Jones, Citation2010, pp. 280–282, 301). The low entry barrier attracted many players from other industries to diversify into it (Jones, Citation2010, p. 242, 354); Nihonsakari was one of them.

Figure 4. New Entrepreneurial history in Nihonsakari from 1975 to 2020.

Source: drafted by authors.

Note: The grey dots represent the different types of activating resources in a declining sake industry, and the dark dots represent the activating resources in rising industries. The arrows between the dots show the entrepreneurial processes of transforming one type of resource into another.

Table 2. Major innovations in cosmetics 1987–2020.

5.1. Envisioning and valuing opportunities: Crisis and unexpected creativity from employees

The main business of Nihonsakari started declining from the 1980s, and the future of its business was threatened. In 1988, Noboru Koide, an employee in the Planning & Development Division, explained the background of the developing cosmetic business: ‘The demand for sake has levelled off in recent years, and there is a sense of crisis in the business if [we] only depended on selling sake’ (NRS, Citation1988). Although there was an urgent need to begin something new, the process of starting the cosmetic business was not planned or expected. The idea to develop cosmetics based on rice bran was first proposed by a salesman who had observed his grandmother using it as soap in 1985. However, his proposal did not gain attention from the company’s Planning & Development Committee (NMRS, Citation2006; Asano, Citation2009). Coincidentally, a young female staff member working in the Planning & Development Division heard about the idea and was personally keen on it. She contacted Picasso Aesthetics Laboratory, a small independent company specialising in cosmetic original equipment manufacturing based nearby, to develop a trial product of rice bran face cleanser to resolve her own skin problem (Asano, Citation2009). The trial product was a success. The employee then proposed a business plan for a cosmetic based on rice bran to the Planning & Development Committee in 1986 but was rejected outright because cosmetics was an entirely different industry from the main sake business. It was perceived as too risky. The employee was not discouraged; she was passionate about the cosmetic idea and submitted the plan to the Planning & Development Committee again the next year (Asano, Citation2009). The Committee decided to launch a rice bran face cleanser to test the market within its old distribution channels. It estimated JPY 5 million (approximately USD 50,000) in sales for a year; however, the result was JPY 100 million (USD 1,000,000) for the facial cleanser alone (NRS, Citation1988). Thus, the new cosmetic business plan was officially adopted in 1988 (Asano, Citation2009).

This innovation process, exposed in various articles from business newspapers, may look like storytelling the company developed to link its new product to ‘tradition’. Yet, unlike most European luxury companies, Nihonsakari does not use such a story to advertise its cosmetics. Moreover, beyond the episode about the employee’s grandmother, this narrative shows that the evaluation of the opportunity was not an easy process and not a top-down decision. From 1988 to 2000, the company still carried the name Nishinomiya Sake Brewer, and the cosmetics business was not yet seen as an opportunity; it was treated as a side business only. Although the president published some principles for new product development, the company was still trying to continue as a sake brewer with its prestigious history and heritage. The sales from non-sake products were relatively small (see ). In the 2000s, the deteriorating sake business environment and rapidly declining sales of sake were then regarded as an opportunity for the cosmetic business when the president decided to change the company name to Nihonsakari (NSS, Citation2000).

5.2. Allocating and reconfiguring resources: Co-creation and utilisation of old resources

In 1988, Noboru Koide expressed a major challenge to diversification, stating that ‘since we have accumulated know-how and put all resources in sake, to develop products that are completely different from sake would be too burdensome’ (NRS, Citation1988). However, all resources, including raw materials, sake products, machines, sales channels, salespeople, development teams, old customers and old business partners, were largely utilised in developing the cosmetics business (NRS, Citation1988, Citation1995c; NSS, Citation1990, Citation1992b). Nevertheless, these resources alone were not sufficient to make Nihonsakari a cosmetics manufacturer because the cosmetics industry had its own specificities. Since Nihonsakari did not have any know-how in cosmetics research, the company built a new business partnership with Picasso Aesthetics Laboratory, which had the research capability to develop cosmetic products jointly (NSS, Citation1988). To remain competitive, Nihonsakari decided to focus only on the niche market of natural cosmetics—thus, the relation with rice.

The reconfiguring of old resources took three major forms. First, the primary raw material for cosmetics is the by-product of rice bran. Normally, to achieve a higher quality of sake, rice is polished to 40%, with 30%–60% of the raw material wasted in the polishing process. These waste materials were utilised in building the cosmetics business (NRS, Citation1988). In the process of joint development, which was not only limited to rice bran and the sake itself, sake yeast also became a raw material for cosmetics (NRS, Citation1995c). Second, the cosmetics products were first distributed in the same sales routes as sake to explore sales from old sake customers and the families of sake customers. Initially, the distribution channels were mainly liquor stores. Gradually, old business partners who had previously traded with Nihonsakari, such as co-ops and large department stores, joined in trading the new business products (NMRS, Citation2006; Asano, Citation2009). The sales routes expanded outside of the old sake routes in the process of interacting with old customers and exploring new customers; new distribution channels, such as the internet sales route, were developed in 2000 in response to customers’ need to purchase online (NMRS, Citation2006). Drugstores and variety stores were developed to cater to the younger generation’s purchasing habits (Asano, Citation2009). Third, ever since Nihonsakari started the cosmetics business, they have continuously developed, upgraded and reinvented it by interacting with consumers and business partners over a long-term period (see ).

5.3. Legitimising novelty: Branding and changing enterprise name and image

Nihonsakari has a history of more than 100 years of producing sake. As it carries many honours and heritage in its past, it is difficult to draw a dividing line from the present. It took a long time for the company to finally legitimise the new business as a source for growth. The consumption of sake started to decline from the 1970s, and the company focussed only on that product with the sole purpose of revitalising sake sales. After a decade of continuous decline, the president finally announced a change in 1989, which was the company’s centennial anniversary. He published a new management philosophy for the company: the aim to be a beloved company with dreams, to bring happiness to society. At the same time, he released ‘Nature’, ‘Fresh’ and ‘Healthy’ as the guidance for new product development (NRS, Citation1995b). Two years later, in 1991, the president announced the creation of a new business forum, with four project teams ready to proceed with diversification to increase revenue from other types of business (NSS, Citation1991). However, the company kept its old name as Nishinomiya Sake Brewer, and the innovations were mostly focussed on sake. Only a few by-products that were highly relevant to its sake products were developed and branded, such as ‘Ginjo Jelly’, a jelly made of ginjo sake and fruit. New cosmetics business has been marketed highly relevant with sake; for example, cosmetic brand names are linked with sake, such as ‘Rice bran beauty’ (NRS, Citation1988) and ‘Sake beauty’ (NRS, Citation1995b, Citation1995c). In advertising, Nihonsakari used its long history as a sake brewer to strengthen its legitimacy for developing high-quality cosmetics (Nihonsakari, Citation2020). When the decline continued and accelerated for another decade, the president finally changed the name of the company from Nishinomiya Sake Brewer to its brand name Nihonsakari in 2000. New headquarters were also built, which suggested a willingness to change the company’s image. They contain four sections that embody the firm’s various businesses: a restaurant, a beauty salon, a sake dissemination centre, and a retail shop to legitimise its cosmetics business (NSS, Citation2000; NKS, Citation2000). From then on, employees’ novelty was legitimised officially by the company. They became more creative with the cosmetics business development by interacting with customers. For example, they organised workshops on basic knowledge and selection of skincare, courses for experiential skincare with the company’s own cosmetics in its building and online, concerts and speeches to interact with customers regularly (NMRS, Citation2001) and online cosmetics lectures for customers (Nihonsakari, Citation2020).

5.4. Conclusion

The move into cosmetics is a clear expression of diversification by a sake brewer in a new activity as a response to a decline in the sake industry. It can be considered as an outcome of entrepreneurship. It shows that unlike the mainstream understanding of entrepreneurship, where a genius CEO invents a new business or discovers a new market, it is a co-creation process that involves the innovativeness of employees and external local stakeholders. In the end, the CEO gave some justification for this process (see ). Although this study only discussed the case of cosmetics, other innovative actions follow a similar pattern. For example, the second main field of diversification was food, although data on this activity are limited, and a detailed discussion would require further research. However, the development of this division followed a very similar pattern to the cosmetics business; that is, an innovative response as a co-creation process with external partners. This novelty was also legitimised in the same manner as the cosmetics business, with justification by the CEO.

6. Discussion and conclusion

This study’s objective was to understand how small family firms could adapt to a declining industry and maintain their existence through the example of the sake brewer Nihonsakari. This company succeeded in implementing a diversification to cosmetics. Today, almost half of its revenues are from sales other than sake. Diversification into another industry was necessary for maintaining its longevity. While many researchers have pointed to diversification as a major factor for achieving longevity in a declining industry, few, if any, have dealt with the concrete processes on the firm level that make diversification possible. Our study focussed on these processes. It demonstrated that diversification was not as simple as argued in the literature. It does not result from a mere top-down decision but rather from long-term persistent co-creation processes among multiple stakeholders. This co-creation process entails creativity from employees, collaborations with old partners, co-development with new partners, legitimisation by the CEO and customers’ interactions as the core entrepreneurial processes driving firm longevity. Based on this demonstration, the implications of our research are as follows.

First, this study contributes to academic research on the survival of family firms in declining industries. Each industry has its own life cycle, and decline is a universal phenomenon that can be cured (Hirschman, Citation1970). Therefore, research on the process of responding to a decline is useful to understand what helps organisations avoid dissolution. The case of Nihonsakari shows that persistent, collaborative processes among stakeholders enable the use of its old resources to diversify into other growing industries. Diversification facilitates the long-term survival of large organisations, as demonstrated by Watanabe (Citation2011) in the case of Japanese textile companies that refocused on chemicals, materials and other fields from the 1950s and still exist today. Conversely, in Western countries, companies tend to exit when their industry is in decline, and investors create new companies in newly growing industries (Watanabe, Citation2011, p. 23; Nobeoka, Citation2006). A difference between the general model offered by Watanabe (Citation2011) and Nihonsakari’s is that the latter remained in the declining industry, although growth came from a new business. It did not give up sake brewing as a major activity. This could be explained by the institutional factor of the Japanese ie (family business), which is the basic institution that has shaped Japanese society for several centuries and has a social responsibility towards local communities (Donzé & Smith, Citation2018; Hirschman, Citation1970). Therefore, the long-lasting continuity of traditional family businesses is highly valued by the local community. With their traditional businesses, long-standing firms are seen as symbolic of the local tradition (Sasaki et al., Citation2019). These values are embedded in firms, which do not disperse as freely as their Western counterparts. Yet, these values have also impeded the possible growth of the firms by prohibiting them from adjusting to changing markets and competition in a timely manner. Nihonsakari faced a decline in sales beginning the 1980s, but its diversification did not happen until 2000.

Second, longevity does not necessarily mean growth. Nihonsakari has improved its operating profit rate and diversified into other industries to gain new stable revenue in response to the decline in the sake industry. Nevertheless, the number of employees has decreased from 554 in 1978 to 184 in 2020, as have sales (JPY 39 billion in 1979 and JPY 13 billion in 2019). As the firm was trying to keep sake as the main business, which is a strongly culture-rooted industry, growth on a new basis is particularly challenging. For example, expansion into the global market is also restricted by its essence of national culture. Sake will always be seen as something Japanese, unlike high-tech industries. To overcome the challenges companies in traditional industries face, Washida (Citation2014) proposes three strategies: use of traditional know-how to develop products designed for the modern lifestyle, promotion of exports, and transformation of traditional know-how into modern manufacturing. These can be achieved through the entrepreneurial process analysed in this study. However, Nihonsakari represents only one type of pattern in culture-rooted industries. Long-standing Japanese firms are distributed widely in different traditional industries; therefore, comparative research should be conducted to understand the dynamic patterns of entrepreneurial processes in various traditional industries.

Third, the new entrepreneurial history approach advocated by Wadhwani and Lubinski (Citation2017) is an important analytical tool to make sense of past research on the longevity of Japanese family firms. Several scholars have emphasised the importance of the involvement of companies in local communities that can provide assistance and resources (e.g., Motoya, Citation2004; Sone, Citation2010), while others have insisted on the symbiotic relationship created between a company and the local community (Sasaki et al., Citation2019). However, these studies are rather vague about how local communities can concretely contribute to the longevity of firms. Hence, this study demonstrated that adopting an appropriate theory, such as proposed by Wadhwani and Lubinski (Citation2017), can integrate relations with local stakeholders within a general explanation of a firm’s ability to reposition towards a new business. It helps illustrate how opportunities to build relationships are envisioned and valued over the long term, how resources are reconfigured, and how relationships are legitimised. This systematic unpacking of the interdependent relationship between business and community reveals how these relationships are changed and reshaped in the long term to drive business longevity and further contributes to the broader understanding of sustainability.

Finally, this article emphasised the need to discuss the longevity of firms based on company financial data and analysis of the specific dynamics of the industry (Bouwens et al., Citation2017). An overwhelming majority of previous studies on firms’ longevity provide no financial data; the contexts of the firms studied and industry are largely unknown. Therefore, it is difficult to clearly identify substantial changes connected with firm longevity. Firms do not exist by themselves. They operate in a dynamic historical and social context within a specific industry. They develop based on lucrative opportunity with a specific product, technology, economic function and market. Yet, when this business model disappears (like growing domestic demand for sake in the case discussed in this paper), the company must find ways to explore new opportunities, and only an analysis based on financial data allows an appropriate evaluation of the significance of a change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Qing Xia

Qing Xia is a PhD student at the Graduate School of Economics, Osaka University. She is currently completing a doctoral thesis on the transformation of traditional industries in Japan. Contact information: Osaka University, Graduate School of Economics, Machikaneyama 1-7, Toyonaka Osaka 560-0043, Japan. Email: [email protected].

Pierre-Yves Donzé

Pierre-Yves Donzé is a professor of business history at the Graduate School of Economics, Osaka University, and a visiting professor at the University of Fribourg, Switzerland. Contact information: Osaka University, Graduate School of Economics, Machikaneyama 1-7, Toyonaka Osaka 560-0043, Japan. Email: [email protected].

References

- Adachi, M. (1974). Shinise no kakun to kagyō keiei. Hiroike Gakuen Jigyōbu.

- Agarwal, R., Sarkar, M. B., & Echambadi, R. (2002). The conditioning effect of time on firm survival: An industry life cycle approach. Academy of Management Journal, 45(5), 971–994.

- Alexander, J. W. (2013). Brewed in Japan: The evolution of the Japanese beer industry. UBC press.

- Asano, H. (2009). Wafū no shizen-ha keshōhin" de ninki o yobu nihonsakari no ‘komenuka bijin. Kokusai Shōgyō, 42(6), 48–51.

- Bagley, M. J. (2019). Networks, geography and the survival of the firm. Journal of Evolutionary Economics, 29(4), 1173–1209. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00191-019-00616-z

- Bouwens, B., Donzé, P. Y., & Kurosawa, T. (Eds.). (2017). Industries and global competition: A history of business beyond borders. Routledge.

- Box, M. (2008). The death of firms: Exploring the effects of environment and birth cohort on firm survival in Sweden. Small Business Economics, 31(4), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-007-9061-2

- Capasso, A., Gallucci, C., & Rossi, M. (2015). Standing the test of time. Does firm performance improve with age? An analysis of the wine industry. Business History, 57(7), 1037–1053. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2014.993614

- Carr, C., & Lorenz, A. (2014). Robust strategies: Lessons from GKN 1759–2013. Business History, 56(7), 1169–1195. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2013.876531

- Chirico, F., & Nordqvist, M. (2010). Dynamic capabilities and trans-generational value creation in family firms: The role of organizational culture. International Small Business Journal: Researching Entrepreneurship, 28(5), 487–504. https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242610370402

- Collins, J. C., & Porras, J. I. (2005). Built to last: Successful habits of visionary companies. Random House.

- Craig, T. (1996). The Japanese beer wars: Initiating and responding to hypercompetition in new product development. Organization Science, 7(3), 302–321. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.7.3.302

- Dias, M. D. O., & Davila Jr, E. (2018). Overcoming succession conflicts in a limestone family business in Brazil. International Journal of Business and Management Review, 6(7), 58–73.

- Donzé, P. Y., & Smith, A. (2018). Varieties of capitalism and the corporate use of history: The Japanese experience. Management & Organizational History, 13(3), 236–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2018.1547648

- Ebert, T., Brenner, T., & Brixy, U. (2019). New firm survival: The interdependence between regional externalities and innovativeness. Small Business Economics, 53(1), 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-018-0026-4

- Francks, P. (2009). The Japanese consumer: An alternative economic history of modern Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- Francks, P., & Hunter, J. (Eds.). (2012). The historical consumer: Consumption and everyday life in Japan, 1850–2000. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Giner, B., & Ruiz, A. (2020). Family entrepreneurial orientation as a driver of longevity in family firms: A historic analysis of the ennobled Trenor family and Trenor y Cía. Business History, 1–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2020.1801645

- Gomi, I. (2020). Dentōkugei sangyō ni okeru famirībijinesu no inobēshon keiei - kinpaku sangyō kara kōgyō seihin seizō kigyō e. Hokurikudaigaku Kiyō, (49), 15–36.

- Goto, T. (2013). Secrets of family business longevity in Japan from the social capital perspective. In K. X. Smyrnios, P. Z. Poutziouris, & S. Goel (Eds.), Handbook of research on family business (2nd ed., pp. 554–587). Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states (Vol. 25). Harvard University Press.

- Hogarth, R. M., Michaud, C., Doz, Y., & Van der Heyden, L. (1991). Longevity of business firms: A four-stage framework for analysis. INSEAD.

- Ide, F. (2019). Nihonshu kuramoto no shūseki to hanro kakudai, kaigai tenkai. Ritsumeikan Kokusai Chiiki Kenkyū, (49), 69.

- Iwasaki, N., & Kanda, M. (1996). Sustainability of the Japanese old established companies. Seijo Daigaku Keizai Kenkyū, (132), 130–160.

- Jones, G. (2010). Beauty imagined: A history of the global beauty industry. Oxford University Press on Demand.

- Katō, K. (2008). Shinise kigyō kenkyū no aratana tenkai ni mukete – keiei senryaku-ron ni okeru kaishaku-teki apurōchi kara. Kigyō-ka Kenkyū, (5), 33–44.

- Kobayashi, k. (2011). Dentōkugei kara kindai kigyō e no jigyō kakushin - Arayakōgyō Daidōkōgyō sōgyō-sha: Shodai Nīnomi Kumakichi no kēsu. JAIST Puresu.

- Komatsu, H. (1975). ‘Noren ni tsuite no keiei-gaku-teki kōsatsu. Shakai Kagaku Ronshū” (Saitamadaigaku Keizai Kenkyūshitsu) Dai 35-gō, 43–71.

- Lee, Y. S., & Shin, W. J. (2015). Marketing tradition-bound products through storytelling: A case study of a Japanese sake brewery. Service Business, 9(2), 281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11628-013-0227-5

- Maekawa, Y. (2015). Naze ano kaisha wa 100-nen mo hanjō shite iru no ka: Shinise ni manabu eizoku keiei no gokui 20. PHP Kenkyūjo.

- Maruyama, K. (2017). Dentō sangyō ni okeru inobēshon o okosu kigyō-ka seishin. Kansai Benchā Gakkaishi, 9, 26–34.

- Mehrotra, V., Morck, R., Shim, J., & Wiwattanakantang, Y. (2013). Adoptive expectations: Rising sons in Japanese family firms. Journal of Financial Economics, 108(3), 840–854. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.01.011

- Motoya, R. (2004). A statistical analysis about the regional closeness of ‘long-lived companies. Oita University. Journal on Kansai University of International Studies, 1, 37–54.

- Moya, M. F., Fernandez-Perez, P., & Lubinski, C. (2020). Standing the test of time: External factors influencing family firm longevity in Germany and Spain during the twentieth century. Journal of Evolutionary Studies in Business-JESB, 5(1), 221–264. https://doi.org/10.1344/jesb2020.1.j073

- Napolitano, M. R., Marino, V., & Ojala, J. (2015). In search of an integrated framework of business longevity. Business History, 57(7), 955–969. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2014.993613

- Nelson, R. R., & Winter, S. G. (1982). An evolutionary theory of economic change. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Nobeoka, K. (2006). MOT ‘gijutsu keiei’ nyūmon. Nihonkeizaishinbun Shuppan-kyoku.

- Ōnishi, K. (2013). Shinise kigyō ni miru 100-nen no chie. Kōyō Shobō.

- Ono, Y. (2018). Shuzō-gyō keiei-sha no kigyōya kōdō Shiga ken no nihonshu mēkā ni okeru jigyō henkaku ni kansuru kenkyū. Shigadaigaku Keizaigakubu Kenkyū Nenpō, 25, 50.

- Ortiz-Villajos, J. M., & Sotoca, S. (2018). Innovation and business survival: A long-term approach. Research Policy, 47(8), 1418–1436. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2018.04.019

- Panza, L., Ville, S., & Merrett, D. (2018). The drivers of firm longevity: Age, size, profitability and survivorship of Australian corporations, 1901–1930. Business History, 60(2), 157–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2017.1293041

- Parker, S., Peters, G. F., & Turetsky, H. F. (2002). Corporate governance and corporate failure: A survival analysis. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 2(2), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1108/14720700210430298

- Porter, M. E. (2004). Competitive advantage: Creating and sustaining superior performance. Free Press.

- Riviezzo, A., Skippari, M., & Garofano, A. (2015). Who wants to live forever: Exploring 30 years of research on business longevity. Business History, 57(7), 970–987. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2014.993617

- Sasaki, I., & Sone, H. (2015). Cultural approach to understanding the long-term survival of firms–Japanese Shinise firms in the sake brewing industry. Business History, 57(7), 1020–1036. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2014.993618

- Sasaki, I., Ravasi, D., & Micelotta, E. (2019). Family firms as institutions: Cultural reproduction and status maintenance among multi-centenary shinise in Kyoto. Organization Studies, 40(6), 793–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618818596

- Sherman, L. (2017). If you’re in a dogfight, become a cat! Strategies for long-term growth. Columbia University Press.

- Sone, H. (2010). Shinise kigyō to jimoto kigyō to no sōgoizon kankei ni tsuite —— shinise miyadaiku kigyō o chūshin ni ——. Studies in Regional Science, 40(3), 695–707. https://doi.org/10.2457/srs.40.695

- Stadler, C. (2011). Enduring success: What we can learn from the history of outstanding corporations. Stanford University Press.

- Sumihara, N. (2004). Tradition’ as a solution to the crisis of Japanese sake industry. Αγορα, (2), 27–37.

- Tàpies, J., & Moya, M. F. (2012). Values and longevity in family business: Evidence from a cross–cultural analysis. Journal of Family Business Management, 2(2), 130–146. https://doi.org/10.1108/20436231211261871

- Thornhill, S., & Amit, R. (2003). Learning from failure: Organizational mortality and the resource-based view. Statistics Canada.

- Van Praag, C. M. (2003). Business survival and success of young small business owners. Small Business Economics, 21(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1024453200297

- Wadhwani, R. D., & Lubinski, C. (2017). Reinventing Entrepreneurial History. Business History Review, 91(4), 767–799. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680517001374

- Wadhwani, R. D., Kirsch, D., Welter, F., Gartner, W. B., & Jones, G. G. (2020). Context, time, and change: Historical approaches to entrepreneurship research. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 14(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1346

- Washida, Y. (2014). Dezain ga inobēshon o tsutaeru – dezain no chikara o ikasu atarashī keiei senryaku no mosaku. Yūhikaku.

- Watanabe, J. (2011). Sangyō hatten suitai no keizai-shi: judai bō no keisei to sangyō chōsei. Yūhikaku.

- Wild, A., & Lockett, A. (2016). Turnaround and failure: Resource weaknesses and the rise and fall of Jarvis. Business History, 58(6), 829–857. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1024229

Published sources

- Nikkei. (1978–2005). Kaisha sōkan (unlisted), Nihon Keizai Shinbun.

- Nihonsakari. (1989). Nishinomiyashuzō hyakunenshi. Nishinomiyashuzō Kabushiki Kaisha.

- Tōyō Keizai. (2006–2020). Kaisha shikibō (unlisted), Tōyō Keizai Shinbun.

Online sources

- JNTA. (2010). Shurui hanbai (shōhi) sūryō no suii. Japan National Tax Agency. https://www.nta.go.jp/taxes/sake/shiori-gaikyo/shiori/2010/pdf/06.pdf#page=1

- JNTA. (2017). Kaigai yushutsu ni kansuru hiaringu no gaiyō. Japan National Tax Agency. https://www.nta.go.jp/taxes/sake/yushutsu/pdf/hearing_gaiyo.pdf

- JNTA. (2018). Seishu seizō-gyō no gaikyō (Heisei 30-nendo chōsa-bun). Japan National Tax Agency. https://www.nta.go.jp/taxes/sake/shiori-gaikyo/seishu/2018/index.htm

- JNTA. (2019). Sake no shiori (Heisei 31-nen 3 tsuki). Japan National Tax Agency. https://www.nta.go.jp/taxes/sake/shiori-gaikyo/shiori/2019/index.htm

- NHS. (1995, September 6). Bitamin ōku kanzō ni yasashī “kinō-sei” nihonshu ―― Nishinomiyashuzō. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 14.

- Nihonsakari. (2020). Official website of Nihonsakari. https://www.nihonsakari.co.jp/index.shtml

- NKS. (1995, September 13). Kappu nihonshu, jisshitsu nesage hirogaru ―― konbini ni kōsei. Nihon Keizai Shimbun.

- NKS. (1996, October 25). Kan-gata no kami yōki saiyō, nihonshu ―― Nishinomiyashuzō (nyūfēsu) . Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 15.

- NKS. (2000, August 26). Renga no sakagura e dōzo, Nishinomiyashuzō, taiken kōbō ya baiten. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 46.

- NKS. (2003, June 20). Shizen-ha keshōhin,-shoku no eiyō, o hada ni mo ―― komenuka, sake no kawa, tōnyū. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 35.

- NKS. (2011a, August 17). ‘Nada’ de tōitsu burando, ōzeki nado shuzō 8-sha, kyōsō-ryoku no kaifuku nerau. Keizai Shimbun, p. 3.

- NKS. (2011b, December 7). Hyōgo keizai tokushū ―― gijutsu saizensen, Hyōgo ni, sake dokoro nada, makikaeshi. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 11.

- NKS. (2011c, July 14). Kami koppu de mochihakobi benri ―― nihonsakari. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 33.

- NKS. (2013a, August 8). ‘Nada no kiippon’, raigetsu 21-nichi hatsubai, shuzō 9-sha. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 46.

- NKS. (2013b, May 15). Nankainanbaeki de kizake hakariuri, nihonsakari, kikan gentei. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 10.

- NKS. (2013c, August 26). Nihon Sakari Ueno Tarō-san ―― nihonshu no kaigai shinshutsu o shiki (senpai no shōzō 10-nen-go no kimitachi e) . Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 29.

- NKS. (2015, January 7). Nihonsakari, Ginza-eki de nama genshu hanbai, kishōna sake, toshin de PR. Nihon Keizai Shimbun, p. 15.

- NMRS. (2001, November 15). Hyōgo Nishimiyaichi no shuzō kakusha, sakagura o kaisō, josei yowa su ―― ryōri-ten ya esute ni. Nikkei MJ Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 13.

- NMRS. (2004, September 30). Nyūyoku-go mo shittori-kan, nihonsakari (shinseihin). Nikkei MJ Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 10.

- NMRS. (2006, July 21). Nihonsakari ―― komenuka de kiso keshōhin, seibun chūshutsu ni dokuji shuhō (zūmuin wazaari kigyō). Nikkei MJ Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 6.

- NMRS. (2015, January 7). Nihonshu, botoru kan de gubi ∼ tsu, famima, nihonsakari to jakunen-sō kaitaku. Nikkei MJ Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 15.

- NMRS. (2017, November 22). Aminosan de hada shittori,’nihonshu keshōhin’ zokuzoku, shizen sozai ninki, hōnichi kyaku ni mo. Nikkei MJ Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 5.

- NPR. (2017, March 30). Nihonsakari,’komenuka bijin bihatsu shirīzu’ o zenpin rinyūaru. Nikkei Press Release.

- NRS. (1986, June 26). Kizake ―― jōon ryūtsū ni fan zōka, shiro wain no kankaku de noma reru (uresuji). Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 12.

- NRS. (1987, August 4). Shutoken ni 50 mise mokuhyō, sushi iwa, izakaya o shutten ―― Ōmiya shinai ni 1 gōten. Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 18.

- NRS. (1988, September 27). Nishinomiyashuzō no ‘komenuka bijin’―― shizen-ha imēji zenmen ni (kaihatsu topikkusu) . Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 21.

- NRS. (1995a, October 28). Nishinomiyashuzō ‘Nihon Mori Kenjo ‘―― Kanzōnohataraki tasuke bitamin kyūshū (kurōzuappu senryaku shōhin) . Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 3.

- NRS. (1995b, October 7). Ten’nen bitamin fukumu nihonshu, Nishinomiyashuzō (shinseihin) . Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 6.

- NRS. (1995c, July 25). Nishinomiyashuzō, hatsubai ―― junmaiginjōshu haigō no keshōhin. Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 3.

- NRS. (1996a, October 31). Nishinomiyashuzō no ue sen nihonsakari ‘Kenjo’―― Ten’nen bitamin, hōfu ni fukumu (konshū no itsutsu boshi) . Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 3.

- NRS. (1996b, February 15). Kami pakku-iri tōki gentei seishu, Nishinomiyashuzō (shinseihin) . Nikkei Ryutsu Shimbun, p. 19.

- NSN. (2020, January 16). Bīru ichiba, 15-nen renzoku de zen’nen ware ‘dai san’-hatsu no 4-wari. Nikkei Sokuho News Archive.

- NSS. (1979a, September, 26). Nishinomiyashuzō, 2. 7 L-iri ‘nihonsakari’ no 2-kyū ‘dekabotoru’ o hatsubai. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 11.

- NSS. (1979b, October 15). Nishinomiyashuzō, wakamono-muke no zasshi de seishu no nomikata PR ――’sebon kūru’ ya ‘sōbana’ nado. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 8.

- NSS. (1985a, April 23). Nishinomiyashuzō ga hatsubai, arukōru-bun 8-pāsento no seishu. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 23.

- NSS. (1985b, June 14). Nishinomiyashuzō, tansan-iri seishu hatsubai ―― wakamono-muke dainidan. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 14.

- NSS. (1986a, April 9). Nishinomiyashuzō, 900-miririttoru petto yōki-iri nama chozō-shu hanbai. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 17.

- NSS. (1986b, August 29). Nishimiyaichi (Hyōgo ken) Nada no seishu ni gendai kankaku, yōki ya kōkyū-hin de yowa seru (waga chōnin to sangyō). Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 4.

- NSS. (1986c, September 26). Ni-kyu junmaishu = Nishinomiyashuzō (shinseihin). Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 19.

- NSS. (1987a, November 4). Nishinomiyashuzō ga shin shirīzu,-shi yōki-iri seishu. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 23.

- NSS. (1987b, Apirl 24). Nishinomiyashuzō to pikaso yoshi-ka gakken kaihatsu, komenuka kara sengan-ryō. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 19.

- NSS. (1988, July 1). Nishinomiyashuzō to pikaso yoshi kagaku, komenuka zenshin shanpū ―― sengan-ryō no shimai-hin. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 24.

- NSS. (1990, October 12). Nishinomiyashuzō no shizen keshōhin ‘komenuka bijin’―― pakkēji ni mo soboku-sa (gifuto kara hitto). Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 12.

- NSS. (1991, May 22). Nishinomiyashuzō, ikkyū nihonsakari o hatsubai. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 21.

- NSS. (1992a, May 30). Nishinomiyashuzō to mikaku-tō,’taberu kinjōshu’ kyōdō kaihatsu ―― josei ni shōjun, chūgen shōsen no medama ni. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 4.

- NSS. (1992b, February 20). Nishinomiyashuzō, komenuka-nushi seisei no sengan-zai ―― mukashi no chie, ima ni ikasu (ataru shōhin kaihatsu). Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 30.

- NSS. (1992c, November 7). Kanzō ni yasashī nihonshu, Nishinomiyashuzō ga kenkyū kaishi. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 4.

- NSS. (1995, September 13). Kappu nihonshu, jisshitsu nesage hirogaru ―― konbini ni kōsei. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 18.

- NSS. (1997a, February 17). Nihonsakari, 200-miririttoru ni, kakaku wa sueoki ―― kappu sake zōryō, Nishinomiyashuzō mo. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 16.

- NSS. (1997b, April 4). Nishinomiyashuzō, shigaisen katto no bin tsukatta nihonshu hatsubai. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 17.

- NSS. (1998a, September 2). Nishinomiyashuzō, tōbun 7-wari katto no seishu ―― kenkō shikō ni taiō. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 13.

- NSS. (1998b, November 6). Nishinomiyashuzō, dezain zanshin’na bin saiyō no junmaiginjōshu. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 15.

- NSS. (2000, August 1). Nishinomiyashuzō ga nihonsakari ni shamei henkō (tanshin). Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 17.

- NSS. (2011, August 13). Kikumasamune ga keshōhin san’nyū, Kansai no shuzō kaisha, jigyō kyōka aitsugu. Nikkei Sangyo Shimbun, p. 9.

- Okamoto, Y. (2020). Nihonsakari shachō morimoto tarō-san (39) gorin yotto daihyō kara tenshin ‘ima dakarakoso’. The Sankei News, August 14. https://www.sankei.com/economy/news/200814/ecn2008140032-n1.html

- TDB. (2017). Tokubetsu kikaku: Seishu mēkā no keiei jittai chōsa. Teikoku Data Bank. https://www.tdb.co.jp/report/watching/press/pdf/p171204.pdf

- TDB. (2019). ‘Shinise kigyō’ no jittai chōsa (2019-nen). Teikoku Data Bank. https://www.tdb.co.jp/report/watching/press/p190101.html

- TDB. (2020). ‘Shinise kigyō’ tōsan kyūhaigyō kaisan dōkō chōsa (2019-nendo). Teikoku Data Bank. https://www.tdb.co.jp/report/watching/press/p200512.html