Abstract

Invented market traditions are practices and memories of the past created by corporations and sustained through consumption. Invented market traditions show how organisations have the potential to reorganise collective memories of the past, creating new mnemonic narratives rather than drawing on existing ones. Materiality provides long-term stability to these narratives. This paper focuses on the institution of Italian breakfast, based on milk, coffee, and convenience bakery products such as biscuits, invented by the brand Mulino Bianco. Biscuits exemplify how commodities imbued with nostalgic meanings can mobilise these invented memories and fold them into social practices. The recurring consumption of biscuits at breakfast, which was marketed as a rediscovery of Italian heritage, created those very nostalgic memories that consumers wanted to remember. Invented market traditions show the social repercussions of organisations’ rhetorical work and expose how context plays a role in understanding their success.

Introduction

Tradition is a resource warehouse for the living

J. Soares

The notion of invented tradition was introduced by Hobsbawn and Ranger (Citation1992), focussing on social and political subjects. Invented market traditions, instead, are an interpretation of the past meant to suit organisations’ commercial interests. Invented market traditions are practices and memories of the past created by corporations through marketing strategies, which become part of the national identity through consumption. The focus on the market exposes how businesses and organisations contribute to invented traditions by reorganising shared meanings and memories of the past. Conceptualised through the ‘uses of the past’ approach, according to which organisations produce history for present purposes (Wadhwani et al., Citation2018), invented traditions are rhetorical histories drawing their symbolic resources from a revisited past. Research on ‘uses of the past’ has observed how rhetorical histories emerge through a co-constructive process that engages internal and external audiences of an organisation, leading to potential frictions (Lubinski, Citation2018). Constructed across different audiences, rhetorical histories are prone to instability (Cailluet et al., Citation2018). To avoid it, organisations use narratives and symbols to connect their own rhetorical history to collective memories circulating outside of the organisation (Rowlinson & Hassard, Citation1993). In doing so, invented traditions expose the issue of how organisational narratives can both connect with collective memories and add elements of novelty, as ‘invented’ suggests.

Invented market traditions are explored here through the example of Italian breakfast, a meal based on milk, coffee, and sweet bakery products such as biscuits or rusks. The Italian bakery brand Mulino Bianco promoted biscuits at breakfast as returning to a food heritage, imbuing their consumption with nostalgic meanings. The Italian biscuit business was divided in commercial categories, the most prominent of which were hard sweet biscuits with simpler formulations, and frollini, a rich short dough formulation with a crumbly texture. The invention of Italian breakfast as a tradition paired with the technological development of the frollini, marketed as rediscovered produce, the popularity of which overtook hard sweet biscuits. This product innovation was behind a nostalgic appeal, until it was gradually assimilated in the national consumer culture. This kind of breakfast has become a blueprint for Italian consumption (Vercelloni, Citation1998). Data on national consumption available from the Italian National Institute of Statistics reveals that a breakfast with biscuits, coffee and milk is still the most widely adopted in Italy (ISTAT, Citation2014). According to a study conducted by Osservatorio Doxa/Etnocom on the food habits of foreign people living in Italy, this kind of breakfast has become part of the Italian culinary identity, since adopting it is seen as a sign of integration (Unionfood, Citation2017).

The study of Italian breakfast provides two relevant contributions to the ‘uses of the past’ literature. Firstly, it shows how organisation can invent traditions, not only through the invention of corporate heritage (Brunninge & Hartmann, Citation2019) or through a fictional link with the past (Belfanti, Citation2015), but also through the reconstruction of memories connected to shared consumption practices. Secondly, it suggests that brand-related materiality can facilitate the permanence and reproduction of rhetorical histories by making them tangible, building mnemonic assets out of nostalgia-driven consumption rather than out of a shared past. Rather than looking at a single artefact (Hatch & Schultz, Citation2017), this study considers materiality in mass produced commodities. Commodities provide stability to invented traditions because they reify the rhetorical history circulating through marketing efforts, and because they are embedded in the very memories of shared practices they are meant to recall.

By using primary historical sources, this study offers an original contribution to the literature on historical organisational memory, which adopts archival methods to address the institutionalisation of collective memory (Decker et al., Citation2021). This approach differs from the one adopted in previous publications on the topic. A preliminary review of the role of tradition in the marketplace is available as conference proceedings (Pirani, Citation2020). Pirani et al. (Citation2018) draws on a portion of this dataset and a similar periodisation to exemplify brand practices through the articulation of breakfast in family life. In this paper, the historical analysis of Mulino Bianco covers a span of almost 20 years, from pieces of market research pre-dating the launch of the brand until 1996, and it draws on two integrated marketing campaigns. The first one (1973–1980) covered the launch of the brand, including the development of the frollini biscuit and by the ‘Happy Valley’ campaign. The second one (1992–1996) is the ‘Italian breakfast’ campaign that consolidated the consumption of frollini as a gastronomic tradition. Selected among other marketing activities, these two campaigns are the most significant in shaping the rhetorical history of Mulino Bianco, and both took place in a context of resurging nostalgia.Footnote1

This paper begins with an examination of how invented traditions have been theorised, exposing the link with marketing strategies. The methodology shows the contribution given to historical organisational memory, outlining the archive sources that ground the analysis. The three finding sections engage respectively with the launch of the brand, the development of the frollini as a tangible emanation of rhetorical history, and the validation of the Italian breakfast as a national practice. This paper concludes by remarking how context is key in the success of invented traditions.

Rhetorical history and invented traditions

Following the ‘uses of the past’ literature, the past is a malleable resource that can be interpreted with a purpose (Suddaby et al., Citation2010) and the rhetorical histories resulting from this interpretation are a source of competitive advantage for the organisations (Popp & Fellman, Citation2020). As a strategic asset, rhetorical histories contribute to the development of different forms of identification among internal and external stakeholders (Foster et al., Citation2017). If directed internally, rhetorical histories produce identity and commitment, whereas externally they contribute to reputation building and publicity (Zundel et al., Citation2016). The scholarly discussion over the intended audiences of rhetorical history questions who has the power to manipulate these narratives (Popp & Fellman, Citation2020). Hobsbawn’s definition of traditions has been criticised for considering them as a ‘manipulation of the past that serves dominant interests’ (Soares, Citation1997, p. 12), failing to observe other power dynamics emerging in the creation of customs. Foster et al. (Citation2017) highlighted how rhetorical histories are co-constructed between an organisation and its stakeholders, generating conflict over which version of history is agreed upon. A more situated understanding of rhetorical history takes as units of analysis not only the claims made by internal and external stakeholders, but also those emerging in the context, such as different audiences, existing narratives, and social practices, moving the focus away from managers as isolated creators of organisational narratives (Lubinski, Citation2018). Hence, rhetorical histories are an ongoing project of a plurality of voices (Cailluet et al., Citation2018).

Memories are an important feature of rhetorical histories. The literature on the uses of past and studies of organisational memory share an interest in how organisations reconstruct and represent the past (Foroughi et al., Citation2020; Rowlinson et al., Citation2010). Collective memory is central to this process, as it ‘focuses on the malleability of what is remembered as the ‘past’ for the purposes of the present’ (Decker et al., Citation2021, p. 1129). Rowlinson et al. (Citation2010) first pointed out the collective nature of organisational memory, its role in shaping collective identity through language, narratives, and rituals. Literature on historical organisational memory understands collective memory as an asset to manage corporate culture (Decker et al., Citation2021), confirming it as a core competence of organisations (Coraiola et al., Citation2017), as well as a competitive resource with the potential to generate new collective identities (Lamertz et al., Citation2016). This implies managing the collective memory and rhetorical histories of an organisation in relation to internal and external mnemonic communities, groups bounded by a common past they all seem to recall (Zerubavel, Citation2003). Scholars have shown how organisational narratives can increase their relevance and authenticity if they associate with collective memories shared by mnemonic communities (Foster et al., Citation2011; Lubinski, Citation2018; Wadhwani et al., Citation2018). Mnemonic communities are important because their conscious and unconscious performances of a shared vision of the past validates that past as true (Wadhwani et al., Citation2018). Moreover, mnemonic communities can act as practitioners of shared memories, and of organisational narratives attached to those memories. However, mnemonic communities are not passive recipients, and discrepancies might arise over interpretations of the past held by different audiences (Lubinski, Citation2018).

Rhetorical history work is the management of such discrepancies, and it can use different techniques (Lubinski, Citation2018), including material artefacts which are able to provide authenticity to rhetorical histories (Hatch & Schultz, Citation2017). Since the associations of symbols with a certain version of the past makes history concrete (Suddaby et al., Citation2010), it is reasonable to think that materiality completes this process of embodiment of rhetorical history. The translation of symbolic resources to material ones is one of the emerging directions of research in rhetorical histories (Foster et al., Citation2011), and notorious examples like the Scottish kilt showed how artefacts can catalyse symbolic meanings while smoothing the tension between recalled and institutionalised past (Hobsbawn & Ranger, Citation1992). Rowlinson and Hassard (Citation1993) praise artefacts for their role in meaning management, as organisations ought to acknowledge the strategic importance of investing in ‘material practices that could be given a firm-specific meaning’ (p. 322). Artefacts are also important in eliciting emotions, as the encounter with material memory forms an emotional connection with an organisation’s history (Schultz & Hernes, Citation2013).

The most studied emotion in relation to rhetorical history is nostalgia, an idealisation of the past in the face of current turmoil, which reproduces the past as an alternative rather than a prelude to the present (Tosh, Citation2013). Within organisations, nostalgia is a trigger of emotional responses to historical representations (Wadhwani et al., Citation2018) but also an asset that connects an organisation to audiences’ collective memories (Foster et al., Citation2011). The business potential of nostalgia is also discussed in marketing and consumer literature. Nostalgia in advertising induces positive affective responses (Havlena & Holak, Citation1991), and it allows consumers to escape from the problems of the present through a sanitised version of the past (Goulding, Citation2001; Stern, Citation1992).

Novel social practices and a celebration of the past are both features of invented traditions. Scholars have already shown how marketing strategies can contribute to one or the other. For example, Wrigley’s advertising has been credited for being able to change public perception around the use of chewing gums, despite the social disapproval for chewing in public (Robinson, Citation2004). Weber (Citation2021) has similarly shown how the acceptance of convenience in the American food business resulted from the effort of corporate marketing to overcome consumers’ scepticism. Marketing tools, such as collectible promotional items, can further engage consumers by adding an element of playfulness to a new form of consumption (Pirani et al., Citation2018). In some cases, consumer research is the catalyser of new consumption practices, as exemplified by the adoption of technological appliances such as fridge (Nickles, Citation2002) or washing machine (Asquer, Citation2007).

While these examples illustrate how organisations can deploy marketing strategies to create new practices, some scholars have also investigated how such strategies have contributed to reinventing the past. An example is the deliberate invention of a non-existing founder figure as an asset for corporate heritage and corporate history work (Brunninge & Hartmann, Citation2019). A different marketing strategy is to invent a continuity with the past, as shown with the ‘Renaissance effect’, used to promote Italian fashion in the 50s (Belfanti, Citation2015). By suggesting that the rise of ‘Made in Italy’ was directly descending from an era of artistic genius, the myth of continuity with the Renaissance worked as a guarantee of provenance for the garments and as a PR strategy directed towards buyers and media (Belfanti, Citation2015). The case of both Mulino Bianco and Italian breakfast shows the less documented potential that organisations must reorganise collective memories of the past through marketing strategies. Moreover, it addresses how organisations can merge novelty and nostalgia by inventing new practices through nostalgic-driven consumption, unfolded through the rise of frollini in the Italian market.

Methodology

Based on primary archival sources, this work aligns with historical organisational memory, one of the modes of enquiry Decker et al. (Citation2021) list as meaningful engagement with historiographical reflexivity. Research on historical organisation memory builds on archival sources to trace the shaping and validation of organisational memory in the past (Decker et al., Citation2021). This approach contextualises historical sources and contrasts them with collective account. Following this approach, the study of Italian breakfasts juxtaposes historical records from the organisation with media records and sources from other organisations and contextualises them in the specific social momentum in which they took place (Kipping et al., Citation2014; Lubinski, Citation2018).

The sources are located in the Barilla Historical Archive (Archivio Storico), in Parma, Italy. Barilla is a family-owned multinational company founded in 1877, from which the brand Mulino Bianco branched out in 1975. This analysis starts with the preparatory work the organisation did for the launch of the brand. In 1971, Barilla was a prominent food business in the north of Italy, with 2000 employees and a turnover of 50 billion lire, equivalent to 442 million euro today, and the 15% of share in the pasta market. By 1996, the final year covered in this analysis, Barilla employed 7216 people, and had a turnover of 3239 billion of lire, currently around 2422 million euros (Ganapini & Gonizzi, Citation1994). Thanks to a previous research project on Barilla, the author was already in contact with the archivists, who granted complete access to Mulino Bianco documents, mostly unpublished. These sources are internal communications, correspondence, compiled research summaries, advertising briefs as well as commissioned market and consumer research, media prospects and consultants’ reports. When available, the citation includes the companies executing these reports. All the original documents are in Italian. Titles and quotes have been professionally translated to facilitate the understanding of the original purpose of the documents cited.

The analysis looked at different sources of data, a common triangulation among in historical research (Kipping et al., Citation2014). These archival records have been integrated with three other sets of sources: interviews with former company managers, media coverage on breakfast in magazines and sources from other biscuit producers. Three managers and one employee of Armando Testa, a media company, were selected for their involvement with the advertising of Mulino Bianco between 1971 and 2014. Two of the managers were directly involved in the marketing activity here detailed, while the third provided an overview of Mulino Bianco’s brand identity in relation to these marketing events. The interview with the employee of Armando Testa gave a broader understanding of how the company structured its relations with Mulino Bianco and with scientific bodies. The media coverage of breakfast was observed in the magazines Donna Moderna (1991–1996) and Starbene (1978–1995), available in the Mondadori publisher archive located in Segrate (Italy). The integration includes publications on the Italian bakery industry and sources from other biscuits brands, such as Pavesi and Lazzaroni, whose documents are available in Parma (Archivio Barilla) and in Saronno (Archivio Lazzaroni), Italy, respectively. A further contribution is offered by extending hermeneutical interpretation, mostly textual and visual, to material artefacts (see Cailluet et al. (Citation2018) for an application of visual analysis).

As a result, this historical analysis answers the call for a theoretically informed engagement with historiography (Clark & Rowlinson, Citation2004). Additionally, it offers an original contribution to the underpopulated field of historical organisational memory by looking into the invention of tradition across organisational interests, collective engagement, and repetitive consumption by audiences. Unlike seminal works on organisational traditions (Cailluet et al., Citation2018; Lubinski, Citation2018; Rowlinson & Hassard, Citation1993), this historical enquiry shows the social repercussions of organisations’ rhetorical work and emphasises the role of collective memory and engagement outside of the organisation, specifically through consumption.

The Italian bakery industry and the launch of Mulino Bianco

Until the mid-twentieth century, industrially produced biscuits were sold as fortifying food to support children’s growth or as a specialty product. While not all biscuit producers invested in this type of packaging, elaborate tins signalled a premium delicacy, contributing to the ritual of middle-class hospitality (Franklin, Citation1979). The Italian biscuit market expanded with the ‘great transformation’ which ensued from the economic growth following World War II (Scarpellini, Citation2016). Between 1958 and 1963, the overall industrial production boomed thanks to a rise in yearly investment in industrial technology by 14% (Ginsborg, Citation2006). In line with this, growing investment in the mass production of confectionery and bakery products aimed to satisfy the increasing domestic demand (Chiapparino, Citation2006). Despite the growth, Italian confectionary consumption was still limited in comparison with other countries of the European Economic Community (EEC). For example, in 1963 the consumption of sweet bakery products in Italy amounted to less than half of that consumed in Belgium (Sicca & Colucci, Citation1996). With very little export, Italian biscuits were mostly produced for and consumed in the domestic market and distributed in small family-run shops. By 1973, only 22% of biscuits were sold in supermarkets, with some regional variations; in North-Western regions, supermarkets and bakeries were equally relevant, while in the South groceries were the dominant form of distribution (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1973a). Almost a decade later, only 1.2% of the total production was exported (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1981). Most biscuit manufacturers were located in the north of Italy to serve more mature markets facilitated by more organised retail distribution (Sicca & Colucci, Citation1996).

Barilla had a long-standing history and reputation as a family-owned company specialised in pasta. In 1971, pressed by economic hardship and internal discrepancies, the company was sold to the American multinational W. R. Grace & Company, and it was then reacquired by Pietro Barilla in 1979 (Sutton, Citation1991). Mulino Bianco was born during this parenthesis, resulting from several exploratory studies commissioned by Grace, and aimed at diversifying Barilla’s business (Ganapini & Gonizzi, Citation1994). Lacking a market leader, biscuits profiled as the chosen venture for differentiating Barilla production (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1983). Barilla was a marginal investment within the portfolio of the American corporation, and the decision to diversify production was partially dictated by Grace’s organisational culture and evidence that the pasta industry had become less rewarding. This resulted from both internal and external factors, such as the decree law 427 of 24 July 1973 that capped the prices of dried pasta, generating an ‘abnormal and unstable situation’ in the dried pasta segment (Confindustria, Citation1974). Grace had granted a relative stability in terms of local management (Gallo et al., Citation1998), leaving autonomy over the diversification of production to Italian operation managers.

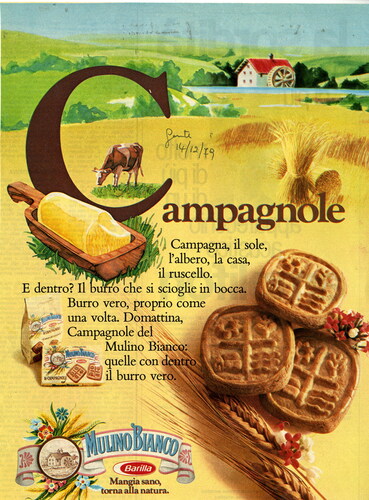

Mulino Bianco was one of the first Italian brands with a cohesive corporate identity informing both marketing communication and product design (Maestri & D’Angelo, Citation1995). This corporate identity mixed - for the first time- peasant knowledge with industrial production, a combination that conditioned more broadly the image of modern Italian food (Dickie, Citation2007). From its launch, Mulino Bianco’s marketing strategy positioned the brand in an imagined pre-industrial past (Arvidsson, Citation2003, p. 109). Every aspect of the brand intended to evoke this era, starting from the logo, a little mill stylised as a nineteenth-century lithograph, to the soft paper bag used for packaging the biscuits (Ganapini & Gonizzi, Citation1994). An example of printed advertising from 1976 shows the company’s strategy to position the audience in recalling this imagined past (), while positioning biscuit consumption in the morning: ‘Do you remember those wholesome biscuits that tasted of butter, milk and wheat? Tomorrow morning, look for them in the White Mill’. Surrounded by ears of wheat and flowers, biscuits resembled a peasant good rather than a modern commodity.

In the first Mulino Bianco TV advertisement aired in 1976, in which a mother sang an old rhyme to her child, invited the audience to remember lost flavours such as those from the ‘white mill’ (Troost, Citation1976). In doing so, it appealed both to personal and collective nostalgia, the first over lost childhood and the second one over lost ingredients and know-how. In the ‘Happy Valley’ campaign that followed, each TV advertisement introduced vignettes of farming life at the turn of the twentieth century with the sentence ‘Do you remember when mills were white’. These idyllic scenes portrayed family and community life of peasants involved in the production of flour, cream, or butter. However, these products were not part of any tradition within the Italian consumer culture, and they rather channelled a distrust of modernity and of industrial food production (Arvidsson, Citation2003, p. 110). Even if Italians did not have any memories connected with these biscuits and practices, they were nevertheless invited to recall them as part of a nostalgic and seemingly more genuine past. A crucial aspect of this strategy was the tactile quality of biscuits, whose irregular shapes and texture stood apart from those of competitors, materialising the rhetorical history of the brand.

Rethinking the frollini: nostalgia and materiality

To emphasise nostalgic feelings towards pre-industrial food and flavours, Mulino Bianco developed a new range of biscuits. Barilla identified the frollini, the richer variety of biscuit, as the one with the highest potential as it was more versatile and yet underdeveloped (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1973a), with a promising growth in annual sales of 6% (Sicca & Colucci, Citation1996). Hard sweet biscuits were the most consumed, but their appeal targeted mostly lower-income families because of the competitive price (Piccardo, Citation2010).

Once frollini was established as the key area of focus, foreign experts in the bakery industry were called to support and innovate the product while adopting a novel approach in its launch. George Maxwell was involved in the research and development of the frollini, testing the biscuit’s recipe; Jean Louis Nachury entered the marketing department as a biscuit project manager, Richard Martin from L.I.M London was involved in the development of the sales department (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1983). Albeit the recipes were adapted from British expertise, considered the country of reference for industrial biscuit production, these innovative biscuits had to blend with national taste. Hence, the foreign influence was never part of the brand’s narrative. Using a pilot plant owned by Barilla, over three years Maxwell developed 260 recipes of frollini and 180 recipes of biscuits (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1970). Of these, an internal panel selected 14 prototypes which were submitted to a performance test with 80 families, who were asked to blind taste them against two biscuits from competitors (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1970).

Mulino Bianco’s new formulations and new packaging represented a technological challenge for the brand, despite the marketing narrative promoting them as a return to artisanal ingredients (Rossi, Citation1994). Each biscuit had a rural-sounding name, and recipe containing wholesome ingredients like cream, eggs, or honey. A print advertising from 1979 for the ‘Campagnole’ showcases all these elements, with a name that recalls campagna (countryside), a shape embossed with flowers and a little mill, and real butter as a distinctive ingredient ().

While these elements provided a rich flavour to the biscuits, their texture made them ideal to be dunked in milk, a practice associated with bread rather than a stand-alone delicacy. The biscuits were manufactured with irregular, round-edged shapes that mimicked the tactile feeling of homemade ones. These were sold in soft yellow bags, which recalled the brown bag used in bakeries while differentiating the brand from the square paper boxes used by competitors (Ancheschi & Bucchetti, Citation1998). Hence, these biscuits materialised the brand narrative outlined, embedding it in the everyday food consumption of Italians.

Mulino Bianco used frollini as a canvas to convey emotional and functional meanings. This is outlined in market research reviewing the development of Mulino Bianco products:

Frollini is connoted as the WHOLESOME biscuit, as it is both nutritious and gratifying. It is experienced as tasty, wholesome, nutritious, and sweet (but not too much). It can be consumed in different moments and in different ways: that is why it can be defined as a ‘multipurpose’. […] Thus, as a biscuit it is a ‘protagonist’, wholesome yet good for display, so it can be offered to guests or as a present (allowing the donor to make a good impression [la bella figura]) (emphasis in the original, Research International-CER, Citation1979).Footnote2

Mulino Bianco’s marketing strategy not only made it the brand market leader, but it also shifted the pattern of biscuit consumption, making frollini the most consumed variety of biscuits. According to an estimation by the Italian Bakery Association, the sale of frollini increased nationally by 12% per year between 1975 and 1980, moving from 61,000 tonnes (t) in 1975 to 98,600t in 1980 (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1983). Over these five years, the overall production of hard sweet biscuits downsized to 50,000t (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1983). This shift in consumption patterns has a twofold explanation. Firstly, as frollini had become a breakfast staple, this invited consumers to look for biscuits in the morning and the marketing of Mulino Bianco contributed to change consumers’ perception of when it was appropriate to consume biscuits. By 1981, morning meals accounted for 77% of frollini consumption, a noticeable difference to the 48% of 8 years prior (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1981). Secondly, the progressive consumption of biscuits by adult consumers. In the first five years after the launch of Mulino Bianco, consumers bought its biscuits to please children rather than all family members (RM-Ricerche di Mercato, Citation1976). In a piece of market research commissioned in 1979, female consumers mentioned biscuits as a staple in their family pantry, but ‘experienced [it] as a food linked to childhood, and even to old age’ (Research International-CER, Citation1979), reflecting the understanding of biscuit as fortifying food as mentioned earlier. However, an elaboration on Nielsen data shows how over the following five years frollini substituted hard sweet biscuits in everyday consumption, particularly in morning meals, with adults becoming regular consumers of frollini. Although children remained main consumers, sources showed a higher concentration of biscuits in households with no children (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1981).

As mentioned earlier, the design of the frollini biscuit was integral to the rhetorical history of Mulino Bianco as it made nostalgic feelings tangible. By embedding frollini within the breakfast practice, consumers could enact this nostalgic performance daily. A market research overview of biscuit categories highlighted how the perceived reassurance of frollini had to be located in a specific social tension:

We are facing an IDEALISATION OF THE PAST: the product, with its young yet ancient appeal promises, and especially ALLOWS, to appropriate a PROJECT (of life and nutrition) based on the denial of one’s past and, at times, of one’s present, lived as meaningless, disappointing, unsustainable and annoying (emphasis in the original, Research International-CER, Citation1982).Footnote3

Frollini catalysed both personal and collective nostalgia, combining meanings associated with the past as well as with childhood. By increasing their consumption of biscuits, adults behaved almost ‘like children’ who had previously been the main consumers of biscuits in Italian households. The growing acceptance of biscuits among adult consumers was significant because it took place amidst a growing concern towards sugar consumption – however, when consuming like children, adults were more likely to pay less attention to the nutritional concerns. Managers recall how books such as ‘Pure White and Deadly’ by John Yudkin (Citation1972) animated the debate over the consumption of sweet bakery products, mobilising both public opinion and scientific interest. In his book targeted at a generalist audience, Yudkin had condensed his experience as a nutritionist, pointing at the dangers of the growing sugar intake in contemporary British diet. These claims had an impact on Italian media as well, warning consumers against processed food. However, consuming biscuits bypassed these nutritional anxieties, perceived as a soothing return to tradition rather than development of a modern food habit.

Creating a mnemonic community: the ‘Italian breakfast’ campaign

While Mulino Bianco invited consumers to rediscover breakfast, there were no shared practices nor memories attached to this meal. The status of tradition was achieved with the ‘Italian breakfast’ campaign that ran between 1992 and 1996: a multi-media operation that rearticulated breakfast as a practice to be rediscovered, supported with novel nutritional knowledge and national symbolic meanings.

Despite Mulino Bianco’s marketing and communication efforts, throughout the 1970s breakfast was still largely overlooked and considered as a meal present during childhood that disappeared ‘proportionally to individual’s participation in modern life’ (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1971). In 1978, the health magazine Starbene revealed how breakfast was only actively imposed upon children under 12 years old (Pasini, Citation1978). As part of a preliminary study on the bakery segment, Mulino Bianco had commissioned a piece of attitudinal research about breakfast in 1973. This data was collected using in-depth interviews with Italian housewives, a widespread and often patronising method within the growing field of qualitative marketing research (Arvidsson, Citation2000). According to the resulting report, consumers believed that breakfast did not have the characteristics of a real meal (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1971) and hence it was not considered in the daily nutritional intake. Interviewed women resisted considering breakfast as a meal because of the domestic burden they already had to carry by preparing lunch and dinner. This task would be accepted only to feed children who were not self-sufficient, and the most suitable products were those closer to bread soaked in milk, such as hard sweet biscuits (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1971). Families would set the breakfast table in the evening, leaving individual family members the responsibility to prepare their own breakfast. As a result, adults would frequently only drink a cup of coffee before leaving the house (Archivio Storico Barilla, Citation1971).

As shown, by the mid-1980s the rapid increase of frollini consumption had changed breakfast practices along with the meanings associated with them. Frollini had provided a more gratifying alternative to hard sweet biscuits or stale bread, whose consumption was now associated with poverty (Imago, Citation1986). However, this change in meanings was not supported by collective memories, leaving the brand unable to validate the origin of this practice in the past. The past that Italians were likely to remember was different from the idealised narrative provided by Mulino Bianco. Despite the nostalgic promise of the brand, consumers did not have a shared understanding of breakfast rooted in memories or passed on by previous generations. In 1990, Mulino Bianco commissioned market research to understand if it was possible to develop a new range of products dedicated to breakfast. The research reported a lack of ‘breakfast culture’ among Italian consumers, despite the evidence that Italians regularly consumed breakfast at home (Leader, Citation1990). What this study referred to was the absence of a dominant model against multiple and often competing narratives of a ‘proper breakfast’, often driven by companies’ interests. One of these was Kellogg’s, promoting cereals as a light and filling breakfast food. In a press release from 1991 monitoring breakfast in the Italian press, 23 articles mentioned cereals and Kellogg’s, whereas 15 talked about biscuits, rusks, or bread (Vimercati, Citation1991b). The analysis of magazines also shows how consumption of yoghurt qualified as an emerging ‘breakfast narrative’ through editorials reassuring consumers of its nutritional properties (see for example Rochefort, Citation1985). Advertising cemented this narrative, claiming that breakfast based on coffee and biscuits would ‘get you until lunchtime’ only if complemented with yoghurt (YOMO, Citation1993).

To amend this lack of a shared cultural understanding of breakfast, the brand designed the ‘Italian breakfast campaign’, a multi-media advertisement feature which ran between 1992 and 1996. A preparatory market research from 1986 made it clear how the historical strategic resources could fill this cultural gap while building a new tradition:

There is a space to be filled in the area of breakfast, a new tradition to be invented. Rather than a new food, there is a need for a new model of organisation, of a reference point from which to begin to structure time and space, to be able to access a pleasure and a necessity without having to say that there is no time or that it is too dirty, too complicated (Imago, Citation1986).Footnote4

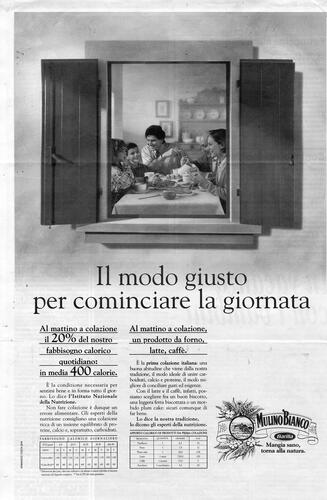

In invented traditions, the celebration of the past is functional as it structures social relationships and provides a sense of identity (Hobsbawm & Ranger, Citation1992). Similarly, in the Italian breakfast campaign, the consumption of bakery products was charged with national meanings, while simultaneously capitalising the nostalgic values embedded in Mulino Bianco brand identity. The planning started in 1991, aiming to provide breakfast with its own cultural profile, while redirecting the public opinion, now amenable to a breakfast based on yoghurt, cereals, and fruits, towards a breakfast model based on milk, coffee, and sweet convenience bakery products (Vimercati, Citation1991a). This model was branded ‘Italian breakfast’ to convey the idea of an everyday meal embedded in national gastronomic principles against other breakfast models coming from abroad.

To promote this campaign, Mulino Bianco collaborated with Media Italia, a PR firm created by specialists from two advertising agencies, Armando Testa and Canard. Media Italia specialised in bridging scientific experts in nutrition and physiology with media and opinion leaders. To do so, Media Italia created a scientific committee called SISA (Italian society for Nutritional Science), which in 1986 created the basis for Fo.S.A.N. (Foundation for the Study of Food and Nutrition), a pool of experts in the field of physiology, nutrition, and paediatrics (Vimercati, Citation1991a). Following a pattern already documented in the food industry (Stoilova, Citation2015), the cooperation of nutritional experts allowed the marketing strategy to occasionally adopt a scientific language. For the three years that the Italian breakfast campaign ran, the company allocated 1.5 billion of lire per year (Vimercati, Citation1991c), a sum that would today be of around 1,041,000 euro. The planned activities included billboard, radio, TV, and print advertising; editorial articles in magazines of the Mondadori group; press conferences; handouts distributed in schools and recreational groups; and scientific conferences and publications in the Fo.S.A.N. quarterly bulletin (Vimercati, Citation1991c). The script of the TV advertisement provides an example of the core narrative:

Every morning, get up with a good habit: breakfast. Milk, coffee, and a bakery product, which are carbohydrates and proteins, are everything we need to face the day ahead. Our tradition and nutritionists say it. Italian breakfast, the right way to start the day (Agenzia Armando Testa, Citation1993).Footnote5

Magazine adverts further detail this narrative of a rediscovered practice. For example, ‘New trends, looking for the lost morning’ (Mulino Bianco, Citation1993a) suggested that modern knowledge could restore morning routines ruined by hectic schedules. Other advertorials, such as ‘Help, my child got bigger: An alert from America’ (Mulino Bianco, Citation1993b) positioned Italian breakfast as part of a national identity by comparing it with foreign models. Here, the combination of bakery products with milk and coffee became more ‘Italian’ against the cooked English breakfast, the French breakfast based on pastries or the German one of muesli and yoghurt. By positioning Italian breakfast as nutritionally sound and embedded in national values, Mulino Bianco provided consumers with a shared understanding of the practice. Additionally, it addressed the ‘rhetorical frictions’ (Lubinski, Citation2018) arising in the context of breakfast, concerning the different models as well as the disjunction between perceived and performed practices.

Like it had been for the launch of the brand, the ‘Italian breakfast ‘campaign took place during a resurgence of collective nostalgia, a change in social sensibility that market research described as a widespread fear of novelty, a comeback of values from the past, and a valorisation of origins (GPF & Associati, Citation1994–5). This shift can be explained with public discontent for the endemic political corruption paired with a moment of economic instability. This peaked with Tangentopoli (from tangente, kickback), an investigation started in 1992 that unravelled a network of criminality which condemned a whole political class (Nelken, Citation1996).

Channelling this cultural zeitgeist, the Italian breakfast campaign once more valorised a return to the past and to stabilising routines. The Italian breakfast exaggerated its historical priority among local consumers who became the mnemonic community of this newly invented practice (Zerubavel, Citation2003). This validation was possible because consumers were already acquainted with the frollini biscuits and their daily use. As part of the campaign, the marketing consultancy GPF & Associati ran a survey in 1993 through selected magazines of the Mondadori Group, collecting answers on 8,000 readers’ breakfast habits. According to the sample, 95% of Italians were having breakfast at home before leaving for work or school (Cavaglieri, Citation1993). Over the following two years, consumers identified a specific combination of coffee, milk, and bakery products as ‘Italian breakfast’, accepting it as part of the national identity (GPF & Associati, Citation1994–5). Meanings had changed too: more than half of the Italians associated ‘Italian breakfast’ with a meal consumed at home, based on coffee, milk and bakery products; moreover, most respondents believed that this was the ideal breakfast. These sources show some competing meanings around Italian breakfast which had not been harnessed by the campaign. For example, a significant minority associated Italian breakfast also with a cup of coffee (22.7%), while some with ‘caffé e cornetto’ (coffee and a pastry) consumed away from home (21.9%). This understanding of breakfast circulating among Italian consumers show a more nuanced articulation of breakfast and national meanings. However, the campaign did not account for this complexity, and instead presented the domestic consumption of bakery products as the dominant narrative of Italian breakfast

Institutional recognition of these new meanings and practices around breakfast followed soon after. In ‘The Guidelines for a Healthy Italian Nutrition’ the National Institute for Nutrition suggested to ‘choose sweets with a low-fat content and with complex carbohydrates (bakery products of the Italian tradition, such as biscuits, dry cakes…)’ remarking the continuity of convenience bakery products with the past (Istituto Nazionale della Nutrizione, Citation1997). Like the 1997 edition of these guidelines, the 2003 edition grounded these indications in the legitimacy of the Italian food heritage: ‘these guidelines intend to guarantee wellbeing and health without mortifying taste and the pleasure of eating. This is easier for those who preserve the traditional habits of our country (…)’ (INRAN, Citation2003).

The ‘Italian breakfast’ campaign connected national and heritage values to a commodity that was already thriving, confirming that organisations can gain legitimacy by enhancing historical narratives (Foster et al., Citation2017). By linking biscuits to national identity, Mulino Bianco engaged Italians not only as practitioners, but also as a mnemonic community of breakfast traditions.

Conclusion

Invented market traditions are intentional manipulations of the past serving business purposes. They extend existing scholarship by showing how corporate traditions participate in the construction of national identity. Scholars have already documented how corporations can invent traditions around their own history, using them as competitive resources (Rowlinson & Hassard, Citation1993; Suddaby et al., Citation2010). Invented market traditions show how rhetorical histories created by corporations have broader implications, as they end up participating in national identities. Unlike those observed by Hobsbawm and Ranger (1992), market traditions are not set up addressing social or political intents, but they take on national meanings because of collective consumption, which builds and consolidates nostalgic practices and memories of them. Hence, invented market traditions are corporate creation of practices and memories alluding to the past, which become part of national identity through nostalgic consumption. The case of Mulino Bianco and of the Italian breakfast, considered here as an invented tradition, provides two contributions to the literature on the uses of the past and to historical organisational memory: first, organisations can contribute to invented traditions by creating a fictitious past and memories attached to it through marketing efforts. The second contribution is that materiality stabilises rhetorical histories, rendering them permanent and prominent over time.

The first contribution shows how organisations concur to invent traditions by inventing mnemonic assets. In doing so, corporate marketing and branding can be listed among the ‘arsenal of techniques’ used in rhetorical history work (Lubinski, Citation2018, p. 1802). The two multi-media campaigns analysed herein serve as examples of how marketing was involved in the maintenance work addressing rhetorical frictions, such as the sustenance of a nostalgic arcadia, or the validation of the Italian model against different breakfast formulas. This finding adds to the existing research on the organisational use of mnemonic assets. Scholars have documented how organisations recall their own past through mnemonic practices (Rowlinson et al., Citation2010), connect with external memory assets, such as social ones (Foster et al., Citation2011), or create a fictional continuity with the past (Belfanti, Citation2015). This study shows instead that Mulino Bianco invented its own mnemonic assets through a version of the past that consumers adopted via consumption practices driven by nostalgia.

The second contribution shows that invented traditions can be anchored in brand-related materiality. This is the case of Mulino Bianco’s frollini, whose texture and flavour made the nostalgic narrative of the brand tangible. Confirming that rhetorical histories are co-constructed with the audience through social practices (Lubinski, Citation2018), materiality emerges as an organisational asset that allows external stakeholders to perform the invented tradition. By consuming a particular kind of biscuit associated with the brand, Italians became a mnemonic community of Italian breakfast. Through the nostalgic materiality of frollini, consumers were not re-enacting a tradition as much as setting its foundations. The ‘Italian breakfast’ campaign shows that organisations not only gain cohesion through the appropriation of collective memories (Foster et al., Citation2011), but also by creating new ones. The continuous exposure to brand-related materiality creates the very mnemonic assets it should remind stakeholders about. Thus, materiality catalyses the symbolic meanings of the rhetorical histories circulating through marketing campaigns and engages practitioners in consolidating shared memories. The analysis of the marketing of Mulino Bianco confirms how memories are recalled and constituted through language and practices (Rowlinson et al., Citation2010), but also through material artefacts.

While materiality is an important asset in stabilising rhetorical histories over time, context also contributes to the success of invented traditions. According to Hobsbawn, the manipulation of invented tradition is the exploitation of practices that meet a need among people, showing that ‘the conscious invention succeeded mainly in proportion to its success in broadcasting on a wavelength to which the public was already tuned in’ (1992, p. 263). Unlike social and political traditions, market ones are a purposeful manipulation aimed at organising and harnessing consumer cultures. This sense-making through rhetorical histories allows organisations to position their products or services within the broader remits of social narratives, such as the restoration of arcadia we have observed here. The narrative of Mulino Bianco succeeded in manipulating memories because consumers themselves became the mnemonic community of this novel breakfast practice. The success of Mulino Bianco’s rhetorical history must be contextualised with a resurgence of collective nostalgia among consumers, here marked by two episodes, one in the mid-1970s and one at the beginning of the 1990s. Across these two decades, the rhetorical work around the invention of Italian breakfast hinged with moments of social and political discontent. Consumption driven by nostalgia here emerges not only as copying mechanism towards the distress of the present (Goulding, Citation2001), but also as a constructive mechanism, able to build new memories and new practices. Above all, invented traditions succeed when they engage practitioners. In the case of the Italian breakfast, consumers themselves accepted the manipulation of the past offered by Mulino Bianco because of the nostalgic meanings it offered, stabilising this practice as an invented market tradition.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniela Pirani

Daniela Pirani is a Lecturer in Marketing at the University of Liverpool. Her research interests include food consumption, and the cultural roles of branding. She is currently looking into how PR and marketing practices contributed to create national identities.

Notes

1 The datasets used in this manuscript and Pirani et al. (Citation2018) largely overlap but are different in some sources and in the interpretation. Since Pirani et al. (Citation2018) focused on family practices, it focused on the visual analysis of the marketing campaigns, and on marketing communication tools not discussed here, such as gadgets and a branded magazine. This study, instead, draws on a corpus of business reports and research and development sources that had not been previously consulted.

2 ‘Il frollino é il biscotto COMPLETO, in quanto assume in se’ sia l’immagine di alimento che di gratificazione. E’ vissuto come un biscotto gustoso, sostanzioso, nutriente e dolce (ma non troppo). Le sue occasioni di consumo sono molteplici, cosí come le sue modalitá d’impiego: per questo é definito un biscotto ‘polivalente’.[…]. E’ un prodotto perció ‘protagonista’, ostentativo, ritenuto completo, quindi adatto da offrire a ospiti o come regalo (consente di fare la cosiddetta bella figura)’ (Research International-CER, Citation1979).

3 ‘Si é di fronte ad una IDEALIZZAZIONE DEL PASSATO: il prodotto, con il suo carattere giovane e contemporaneamente antico, promette, e soprattutto PERMETTE, di far proprio un progetto (di alimentazione e di vita), che é fondato sulla negazione del proprio passato e anche, a volte, del proprio presente, vissuto come avalorizzato, deludente, intollerabile, fastidioso’ (Research International-CER, Citation1982).

4 ‘Esiste quindi uno spazio da colmare nel campo della colazione, una nuova tradizione da inventare. Prima che di un alimento vero e proprio la richiesta e’ di un modello di organizzazione, di un punto di riferimento da cui cominciare a strutturare il tempo e lo spazio, per poter accedere ad un piacere e ad una necessitá senza dover dire che non c’é tempo o che si sporca troppo, é troppo complicato’ (Imago, Citation1986).

5 ‘Ogni mattina svegliati con una buona abitudine, la prima colazione. Latte, caffe’, e un prodotto da forno, cioe’ carboidrati e proteine, proprio quello di cui abbiamo bisogno per affrontare la giornata. Lo dice la nostra tradizione e lo dicono gli esperti della nutrizione. La prima colazione Italiana, il modo giusto per cominciare la giornata’ (Agenzia Armando Testa, Citation1993).

References

- Agenzia Armando Testa. (1993). Archivio Storico Barilla, MB I Re 1993 00013: Prima Colazione. https://www.archiviostoricobarilla.com/en/scheda-archivio/prima-colazione-tarallucci-1-2/.

- Ancheschi, G., & Bucchetti, V. (1998). Il packaging Italiano. Giallo Come il Cioccolato: Piccola Storia di Grandi Scelte. In A. I. Ganapini & G. Gonizzi (Eds.), Barilla: Cento Anni di Pubblicità e Comunicazione (pp. 847–879). Einuadi.

- Archivio Storico Barilla. (1970). Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 1 004: Untitled.

- Archivio Storico Barilla. (1971). Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 1 002: ‘Breakfast U.C.R’, February 25.

- Archivio Storico Barilla. (1973a). Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 5 0004: ‘Research on experiences around biscuits’, National Survey.

- Archivio Storico Barilla. (1973b). Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 4 0001: ‘Biscuits, Positioning Study’, July 5th.

- Archivio Storico Barilla. (1981). Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 5 007: ‘II generation of biscuits’ September 7th.

- Archivio Storico Barilla. (1983). Archive “O”, Legal Affairs. BAR I AFLE 2 0009: ‘Main Lines of Mulino Bianco Case History’, September.

- Arvidsson, A. (2000). The therapy of consumption, motivation research and the new Italian house wife, 1958-62. Journal of Material Culture. 5(3), 251–274.

- Arvidsson, A. (2003). Marketing modernity: Italian advertising from fascism to postmodernity. Routledge.

- Asquer, E. (2007). La Rivoluzione Candida: Storia Sociale della Lavatrice. Carrocci.

- Belfanti, C. M. (2015). History as an intangible asset for the Italian fashion business (1950-1954). Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 7(1), 74–90. https://doi.org/10.1108/JHRM-10-2013-0058

- Brunninge, O., & Hartmann, B. J. (2019). Inventing a past: Corporate heritage as dialectical relationships of past and present. Marketing Theory, 19(2), 229–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470593118790625

- Cailluet, L., Gorge, H., & Özçağlar-Toulouse, N. (2018). ‘Do not expect me to stay quiet’: Challenges in managing a historical strategic resource. Organization Studies, 39(12), 1811–1835. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618800111

- Cavaglieri, R. (1993). Archivio Mondadori, Prima colazione: Ottomila lettori raccontano. Starbene, September 12(16).

- Chiapparino, F. (2006). L’Industria Italiana nell’evoluzione dell’economia Italiana dall’Ottocento ad oggi. In M. Schiaffino (Ed.), Dolce Italia: Storia Immagini e Protagonisti dell’Industria Dolciaria Italiana (pp. 57–76). Alinari.

- Clark, P., & Rowlinson, M. (2004). The treatment of history in organization studies: Towards an ‘historic turn’. Business History, 46(3), 331–352. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007679042000219175

- Confindustria. (1974). Economia industriale. Confederazione Generale dell’Industria Italiana. Confindustria.

- Coraiola, D., Suddaby, R., & Foster, W. (2017). Mnemonic capabilities: Collective memory as a dynamic capability. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 57(3), 258–263. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-759020170306

- Decker, S., Hassard, J., & Rowlinson, M. (2021). Rethinking history and memory in organization studies: The case for historiographical reflexivity. Human Relations, 74(8), 1123–1155. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726720927443

- Dickie, J. (2007). Delizia! The epic story of Italians and their food. Hodder & Stoughton.

- Foroughi, H., Coraiola, D. M., Rintamäki, J., Mena, S., & Foster, W. M. (2020). Organizational memory studies. Organization Studies, 41(12), 1725–1748. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840620974338

- Foster, W. M., Coraiola, D. M., Suddaby, R., Kroezen, J., & Chandler, D. (2017). The strategic use of historical narratives: A theoretical framework. Business History, 59(8), 1176–1200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2016.1224234

- Foster, W. M., Suddaby, R., Minkus, A., & Wiebe, E. (2011). History as social memory assets: The example of Tim Hortons. Management & Organizational History, 6(1), 101–120. https://doi.org/10.1177/1744935910387027

- Franklin, M. J. (1979). British biscuit tins, 1868-1939: An aspect of decorative packaging. New Cavendish Books.

- Gallo, G., Covino, R., & Monicchia, R. (1998). Crescita Crisi, Riorganizzazione. L’industria alimentare dal dopoguerra ad oggi. In A. Capatti, A. de Bernardi, & A. Varni (Eds.), Annali di Storia d’Italia, 13 L’ Alimentazione (pp. 271–285). Einuadi.

- Ganapini, A. I., & Gonizzi, G. (1994). Barilla: Cento Anni di Pubblicità e Comunicazione. Silvana.

- Ginsborg, P. (1990). History of contemporary Italy. Penguin.

- Ginsborg, P. (2006). Storia d’Italia dal Dopoguerra a Oggi. Einaudi.

- Goulding, C. (2001). Romancing the past: Heritage visiting and the nostalgic consumer. Psychology and Marketing, 18(6), 565–592. https://doi.org/10.1002/mar.1021

- GPF & Associati. (1994–5). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, BAR I O COST 3 0039: 3SC Food Monitor Strategic Coordination, p. 60.

- Hatch, M. J., & Schultz, M. (2017). Toward a theory of using history authentically: Historicizing in the Carlsberg Group. Administrative Science Quarterly, 62(4), 657–697. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839217692535

- Havlena, W. J., & Holak, S. L. (1991). "The good old days": Observations on nostalgia and its role in consumer behavior. In R. H. Holman & M.R. Solomon (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research Vol. 18 (pp. 323–29), Association for Consumer Research.

- Hobsbawn, E. J., & Ranger, T. (1992). The invention of tradition (Canto ed.) Cambridge University Press.

- Hobsbawm, E. J. ((1992). Mass-Producing Traditions: Europe, 1870-1914. In E. Hobsbawm & T. Ranger (Eds.), (pp. 263–308) The Invention of Tradition, Cambridge University Press.

- Imago. (1986). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 7 005: ‘Breakfast as it is and as it could be’, May 22, Milan.

- INRAN. (2003). Linee Guida per una sana alimentazione Italiana. http://www.salute.gov.it/imgs/C_17_pubblicazioni_652_allegato.pdf

- ISTAT. (2014). Sanità e Salute. Retrieved August 3, 2021, from http://www.istat.it/it/files/2014/11/C04.pdf

- Istituto Nazionale della Nutrizione. (1997). Linee guida per una sana alimentazione Italiana. Edicomp.

- Kipping, M., Wadhwani, R. D., & Bucheli, M. (2014). Analyzing and interpreting historical sources: A basic methodology. In R. D. Wadhwani & M. Bucheli (Eds.), Organizations in time: History, theory, methods (pp. 305–329). Oxford University Press.

- Lamertz, K., Foster, W. M., Coraiola, D. M., & Kroezen, J. (2016). New identities from remnants of the past: An examination of the history of beer brewing in Ontario and the recent emergence of craft breweries. Business History, 58(5), 796–828. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1065819

- Leader. (1990). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 7 005: ‘Process to define the conceptual lines of the “breakfast” product’, May.

- Lubinski, C. (2018). From ‘history as told’ to ‘history as experienced’: Contextualizing the uses of the past. Organization Studies, 39(12), 1785–1809. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618800116

- Maestri, G., & D’Angelo, D. (1995). Mulino Bianco. In A. Ghini (Ed.). Comunicare l’Eccellenza: Ferrari, Bulgari, Camel Trophy, Mulino Bianco (pp. 111–163). Etas.

- Mulino Bianco. (1993a, June 25) Archivio Mondadori: Nuove tendenze: Alla ricerca del Mattino Perduto. Donna Moderna, 5(25).

- Mulino Bianco. (1993b, July 2) Archivio Mondadori: Aiuto, mi si é allargato il ragazzino: un allarme dall’America. Donna Moderna.

- Nelken, D. (1996). A legal revolution? The judges and Tangentopoli. In S. Gundle & S. Parker (Eds.), (191-205) The New Italian Republic :From the Fall of the Berlin Wall Berlusconi, Routledge.

- Nickles, S. (2002). “Preserving women”: Refrigerator design as social process in the 1930s. Technology and Culture, 43(4), 693–727. https://doi.org/10.1353/tech.2002.0175

- Pasini, F. (1978). La Colazione del Bambino? Starbene, 1 (1).

- Piccardo, L. (2010). Saiwa. Storia. Storiaindustria.it. Centro on line di Storia e Cultura dell’ Industria. Available at: http://www.storiaindustria.it/repository/fonti_documenti/biblioteca/testi/Testo_Saiwa_Storia.pdf

- Pirani, D, (2020). Inventing Marketplace Traditions: Italian Breakfast 1975-1995.In G. Patsiaouras, J. Fitchett & AJ Earley (Eds.), Research in Consumer Culture Theory. Vol 3.

- Pirani, D., Cappellini, B., & Harman, V. (2018). The Italian breakfast: Mulino Bianco and the advent of a family practice (1971-1995). European Journal of Marketing, 52(12), 2478–2498. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJM-06-2018-0374

- Popp, A., & Fellman, S. (2020). Power, archives and the making of rhetorical organizational histories: A stakeholder perspective. Organization Studies, 41(11)1 531–1549. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619879206

- Research International-CER. (1979). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I DIBA 5 000: ‘Potential expansion of the Mulino Bianco biscuit range’, February, Milan.

- Research International-CER. (1982). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery BAR I DIBA 5 0003: ‘Specialised study on the brand image of Mulino Bianco and main competitors in the segments: Biscuits, Snacks, Zwieback’, January, Milan.

- RM-Ricerche di Mercato. (1976). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery BAR I O DIBA 5/009: ‘The female consumers of Mulino Bianco biscuits’ March.

- Robinson, D. (2004). Marketing gum, making meanings: Wrigley in North America, 1890-1930. Enterprise and Society, 5(1), 4–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/es/khh002

- Rochefort, J. (1985). Archivio Mondadori. Yogurt. Starbene, 8(4).

- Rossi, G. (1994). Giallo Come il Cioccolato: Piccola Storia di Grandi Scelte. In A. I. Ganapini & G. Gonizzi (Eds.), Barilla: Cento Anni di Pubblicità e Comunicazione (pp. 292–294). Silvana.

- Rowlinson, M., Booth, C., Clark, P., Delahaye, A., & Procter, S. (2010). Social remembering and organizational memory. Organization Studies, 31(1), 69–87. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609347056

- Rowlinson, M., & Hassard, J. (1993). The invention of corporate culture: A history of the histories of cadbury. Human Relations, 46(3), 299–326. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872679304600301

- Scarpellini, E. (2016). Food and foodways in Italy from 1861 to the present. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Schultz, M., & Hernes, T. (2013). A temporal perspective on organizational identity. Organization Science, 24(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1110.0731

- Sicca, L., & Colucci, M. V. (1996). L’industria dolciaria in Italia: Origini ed Evoluzione. In Associazione industrie dolciarie italiane (Ed.), Dolce Business, Storia e miti dell’industria dolciaria italiana (pp. 9–50). Il Sole 24 Ore Libri.

- Soares, J. (1997). A reformulation of the concept of tradition. International Journal of Sociology and Social Policy, 17(6), 6–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/eb013310

- Stern, B. B. (1992). Historical and personal nostalgia in advertising text: The Fin de siècle effect. Journal of Advertising, 21(4), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/00913367.1992.10673382

- Stoilova, E. (2015). The bulgarianization of yoghurt: Connecting home, taste, and authenticity. Food and Foodways, 23(1-2), 14–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/07409710.2015.1011985

- Suddaby, R., Foster, W. M., & Trank, C. Q. (2010). Rhetorical history as a source of competitive advantage. Advances in Strategic Management, 27, 147–173.

- Sutton, J. (1991). Sunk costs and market structure: Price competition, advertising and the evolution of concentration. The MIT Press.

- Tosh, J. (2013). The pursuit of history. Routledge.

- Troost. (1976). MB I Re 1976 00005, Archivio Storico Barilla: ‘Biscotti Filastrocca Campagnole’. https://www.archiviostoricobarilla.com/en/scheda-archivio/biscotti-filastrocca-gallinella-bianca-campagnole-2/

- Unionfood. (2017, November 21). I nuovi residenti in Italia conquistati dalla colazione “all’Italiana”. https://unionfood.iocominciobene.inc-press.com/nuovi-italiani-conquistati-dalla-colazione-allitaliana

- Vercelloni, L. (1998). La modernitá alimentare. In A. Capatti, A. de Bernardi, & A. Varni (Eds.), (pp. 951–1005) Annali di Storia d’Italia, 13 L’ Alimentazione. Einaudi.

- Vimercati, L. (1991a). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 7 010: untitled, February 12.

- Vimercati, L. (1991b). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 7 010: untitled, February 14.

- Vimercati, L. (1991c). Archivio Storico Barilla, Archive “O”, Bakery, BAR I O DIBA 7 010: untitled, December 19.

- Wadhwani, R. D., Suddaby, R., Mordhorst, M., & Popp, A. (2018). History as organizing: Uses of the past in organization studies. Organization Studies, 39(12), 1663–1683. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840618814867

- Weber, M. (2021). The cult of convenience: Marketing and food in postwar America. Enterprise & Society, 22(3), 605–634. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2020.7.

- YOMO. (1993, 15th of June). Untitled. Donna Moderna, 5(25).

- Yudkin, J. (1972). Pure white and deadly. Viking.

- Zerubavel, E. (2003). Time maps: Collective memory and the social shape of the past. University of Chicago Press.

- Zundel, M., Holt, R., & Popp, A. (2016). Using history in the creation of organizational identity. Management & Organizational History, 11(2), 211–235. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2015.1124042