Abstract

This paper describes the establishment of banking supervision in Italy and its operation between 1926 and 1936, using a narrative approach based on previously classified documents from the Bank of Italy’s Historical Archives. This case is particularly interesting from the international perspective, Italy having been the first European country to assign substantial supervision to its central bank, a few years before the 1929 crisis. Notwithstanding insufficient regulation and a light touch concerning the four major mixed banks, we document considerable enforcement of the law, which went beyond the initial provisions, thanks to the rather proactive supervisory approach adopted by the Bank of Italy.

1. Introduction

In recent years, the issue of banking regulation in a historical perspective has attracted the attention of economic and business historians (Billings et al., Citation2021; Brean et al., Citation2011; Hansen, Citation2001; Lu, Citation2010; Mourlon-Druol, Citation2015; Nath, Citation2021; Ögren, Citation2021; Singleton & Verhoef, Citation2010; van Driel, Citation2019). Until recently, however, research has mainly focussed on regulation per se, while the issue of supervision has received less attention, being somehow implicitly regarded as synonymous of the former. Nevertheless, the mechanics of the supervision regime enforcement might be no less relevant than the formal regulation.

A recent book by Hotori et al. (Citation2022) moves along this path. The authors shift the focus to banking supervision and study the experiences with banking regulation in eight countries.Footnote1 While previous research had advanced that banking regulations were normally the response to financial crises, they argue the picture is more complex: it is difficult to identify a single common pattern. The development of banking regulation is not a one-off event, but the product of a process of ‘formalisation’, i.e. slow and incremental change in institutions.

In this paper, we describe the establishment of supervision on commercial banks in Italy between 1926 and 1936, relying heavily on archival individual bank-files analysis. From an international perspective, the Italian case (not considered in Hotori et al., Citation2022) is particularly interesting, as the set-up of the supervisory activity happened earlier than most of the other Western countries, and a few years before the outburst of the Great Depression (Grossman, Citation2010). Before the latter, the prevailing international consensus regarded price stability (gold convertibility) as a sufficient condition for financial stability. From the 1930s onwards, the consensus radically turned around, both in Italy and in the Western world, steering towards a pervasive public control over the banking sector, ensuring several decades of banking stability, although at the cost of financial repression.

While the interwar and post-WWII years were characterised by a broad international tendency towards greater public intervention in the banking sector, Italy seems to have anticipated this trend before 1929. A general trend might account for it: Grossman (Citation2010) observes that Central Banks established relatively later usually started earlier to perform banking supervision. Countries such as the UK and France, homes of worldwide financial hubs, did not undertake significant supervision, still maintaining a relative laissez-faire attitude towards banking during the 1930s.Footnote2 Accordingly, old institutions such as the Bank of England would have had less flexibility to adapt to a changing economic environment compared to more recent ones, such as the Bank of Italy (BoI). Among the countries considered by Grossman, Italy appears as the third European central bank to take on banking supervisory powers, a few years after two other countries at the economic periphery, Spain and Portugal.Footnote3 However, Spain and Portugal’s central banks did not actively undertake any kind of substantial supervision, nor in or off-site (Capie et al., Citation1994; Martín-Aceña et al., Citation2010). That would mean that Italy was the first European central bank to enforce banking supervision law. According to Guarino (Citation1993), even Italy’s 1926 law may have remained on paper if it were not for the BoI’s proactive and meticulous approach, which allowed the effective building-up of supervisory mechanisms in the long run.

We exploit the rich archives of banking supervision held at the Bank of ItalyFootnote4 and at the Italian National ArchivesFootnote5 to shed light on the day-to-day business of banking supervision in the first ten years of its operation.Footnote6 Using a narrative approach, our research shows the challenges that supervision authorities faced in enforcing the new rules. When it comes to banking supervision, a completely novel process for Italian authorities, deficiencies in organisational structure and staff skills had to be quickly overcome in a continuous process of trials and errors. Where the letter of the law was silent, authorities had to adopt solutions through analogies of existing norms, so that the spirit of the law did not remain a dead letter. While this is true for any regulation, this research shows that enforcement matters. The new evidence presented on Italy reinforces the point made by Hotori et al. (Citation2022, p. 9), who stress that episodes of actual institutional changes do not necessarily coincide with the enactments of banking acts, but need a deliberate willingness and a capacity to enforce them.

Our first contribution is historical, as we fill a gap in Italian financial history, by providing a thorough description of the establishment of bank supervision in Italy after the 1926 banking law. Existing literature has focussed on the shortcomings of the 1926 law, lamenting lax regulation, which did not tackle dangerous bank-industry linkages and the lack of in-site supervision of major mixed banks (Gigliobianco & Giordano, Citation2012). This view stems from the fact that scholars have chiefly focussed on the 1936 all-embracing banking law, which filled the regulatory gaps of the 1926 law and opened the way to several decades of a strong public grip on the banking sector (Barbiellini-Amidei & Giordano, Citation2015). While we maintain the relative truth of these shortcomings, we provide a broader picture showing how enforcement of the law went beyond the initial provision, thanks to a skilful and constructive interpretation of the law undertaken by the Bank of Italy (BoI).Footnote7 A better understanding of the operations of Italian banking supervision in this period should be welcome. In fact, recent research found that even though the number of bank closures due to insolvency was not exceptionally high during the Great Depression, there is evidence that large part of the distress of small and medium commercial banks was resolved behind doors (Molteni, Citation2020, Citation2021).

As a second contribution, we wish to add to the contemporary policy debate in a broader perspective, in the spirit of a recent strand of historical research on the evolution of banking supervision (Calomiris & Carlson, Citation2017, Citation2018; Conti-Brown & Vanatta, Citation2021; Giddey, Citation2019; Gigliobianco & Toniolo, Citation2009; Hotori & Wendschlag, Citation2019; Mitchener & Jaremski, Citation2015; White, Citation2011). Over the course of this analysis, we encountered issues that are still a matter of academic debate: for example, whether or not the central bank should be the supervision authority (Ampudia et al., Citation2019), the trade-off between disclosure to the public and to the supervisor (Prescott, Citation2008), the reliance on market discipline rather than on pervasive public control, the extent to which the supervisor should be bounded by the textual rule content, or rather enjoy discretionary capacity (Mishkin, Citation2001; White, Citation2011), and the trade-off in supervisory resources allocation among different categories of banks (Eisenbach et al., Citation2020). In this respect, historical contributions could be particularly valuable, as current or recent past supervision files are still classified because of confidentiality, limiting their use for research purposes.

The paper is structured as follows. The second section describes the institutional context, the economic and political factors behind the new banking law, and how lobbying pressures brought to a watering down of its regulatory content. The third section describes the organisational structure and the functioning of the newborn supervision mechanisms. It is divided in three sub-sections. The first discusses the authorisation system, the second discusses on-site examinations, and the third discusses off-site examinations. A fourth section concludes.

2. The institutional context and the making of a watered-down law

‘Before 1926, an authorisation from the public authority was required to open a cheap tavern, but in order to open a bank, which may scam depositors, no authorisation was needed’.Footnote8 These suggestive words, taken from the Economic Commission report to the 1946 Italian Constituent Assembly, reveal how, until the 1920s, Italy lacked not only any supervisory mechanisms but even a specific regulation on not-issuing commercial banks, whose regulation was assimilated to common firms (Guarino & Toniolo, Citation1993). Saving banks and pawn banks were the exception, these being under the Ministry of Agriculture, Industry, and Commerce’s supervision, and had to invest in low-risk assets like government bonds.Footnote9 These banks usually collected deposits from poorer and less educated depositors, regarded as less apt to assess the soundness of financial institutions. Apart from that, the established consensus, both among the public opinion and economists, was to rely on market discipline for depositors’ protection. All in all, gold convertibility was regarded as the necessary and sufficient condition for financial stability (for a discussion on the evolution of economic thought in Italy on banking legislation, refer to Gigliobianco & Giordano, Citation2012).

From 1908 onwards, several laws were proposed by members of the Italian parliament or Government in order to regulate commercial banking.Footnote10 Among the many projects, the separation between commercial and investment banking (Francesco Cocco-OrtuFootnote11 project, 1908) and prudential supervision on capital and risk concentration requirements (Eugenio Chiesa project, 1920)Footnote12 were proposed. Yet, none of these projects ever managed to be approved, although they signal a growing demand in political circles for regulating the banking sector. That was linked to the gradual emergence of the role of lender of last resort by the BoI, which justified a more specific regulation for banking. In this matter, Italy was not an exception with respect to the rest of Europe, as all main European countries lacked substantial regulation on banking, as the financial stability mandate was usually limited to price stability.Footnote13 Indeed, the same critics of public intervention in banking argued how it was deemed as sheer nonsense in advanced economies (Prato, Citation1920).

Then, a sweeping expansion of banking activity characterised the 1920s. The need to finance war expenses had led to money circulation growth, which ignited the demand for deposits. The number of bank branches grew from 4,227 to 6,012 between 1913 and 1920, and by 1926 it had skyrocketed to 11,444 (Biscaini Cotula & Ciocca, Citation1979). From 1913 to 1925, joint-stock banks’ nominal assets grew twelvefold, doubling in real terms. On the other side, cooperative and savings banks’ assets growth was in line with overall inflation. Leverage also increased as a consequence of war inflation (Conti, Citation2004).

De Cecco (Citation1986) interprets this sweeping growth of banking activity as a ‘democratisation’ of deposit-taking, i.e. its progressive extension towards the middle class. Notwithstanding, these dynamics had clear shadows, with the emergence of the so-called ‘wildcat banking’, engaged in risky and opaque activities (Conti, Citation2004). In the words of the Governor of the BoI, Bonaldo Stringher:

the complete lack of any banking regulation allowed the establishment of a multitude of banks with little or trifling capitals and their mushrooming in small and large cities through improvised networks of branches, with the specific aim of collecting deposits that often ended up in dreadful speculations.Footnote14

Interestingly, over the years, Stringher’s view on the need for banking regulation had significantly changed: still, in 1911, he maintained that self-regulation, driven by attentive depositors and public opinion supervision, was the most effective way to ensure depositor protection (Calabresi, Citation1996).

Not surprisingly, the main financial reforms in Italian history have been triggered as policy responses to financial crises (Gigliobianco & Giordano, Citation2012). The 1926 law can be associated with the distress of Banca Italiana di Sconto (BIS), one of Italy’s main banks in the early 1920s. BIS was dangerously linked to Ansaldo industrial group, and its growth and distress were driven by military procurements during WWI and their end after the peace treaty (Sraffa, Citation1922). The distress had strong effects on public opinion, provoking up-raged protests by the banks’ creditors. The BoI eventually intervened to liquidate BIS’ assets. At any rate, the crisis seems a turning point in the common perception of the need for banking supervision. BIS was an exemplary case of the morbid linkages between universal banks and industrial firms. There was also the well-known case of the major mixed banks (Credito Italiano, Banca Commerciale and Banco di Roma), but this governance issue also deeply affected medium and small-sized banking (Battilossi, Citation2009; Rinaldi & Spadavecchia, Citation2021; Robiony, Citation2018). At the same time as the BIS’s distress management in 1923, a new banking bill was drafted, most likely internally, by the BoI (Guarino & Toniolo, Citation1993; doc. 66). The bill encompassed a comprehensive regulatory and supervisory mechanism but, like other projects before, it was aborted.

A few years later, the political scenario was more prone to public intervention. Benito Mussolini, who had become prime minister in 1922 amid severe political and economic instability, consolidated his power into an outright dictatorship by 1925. To understand this shift it is worth considering the economic and political scenario of 1925–26, which was called by Toniolo (Citation2013, cit. p.19) ‘the most sudden and complete 180-degree turnaround of economic policy in Italian history’. Post-war economic troubles, such as unchecked inflation and public deficit, were being resolved. A major objective of the new regime was, similarly to other European countries, to proceed towards the return of gold convertibility (which took place in 1927). As a result, 1926 was a crucial year in the development of what we currently view as the modern functions of a Central Bank in Italy. In June 1926, money issuing was centralised by the BoI.Footnote15 Over the same period, the BoI started to work on a law proposal to regulate all deposit-taking institutions. As made clear by the correspondence between Mussolini and the Minister of Finance, Giuseppe Volpi, the former considered the consolidation of depositors’ confidence in the banking system as a precondition for monetary stabilisation.Footnote16 The banking troubles of the early 1920s, the disordered growth of Italy’s branch network, and several local bank failures echoed in the coeval press likely influenced the public opinion towards a more robust demand for public intervention in the banking sector.Footnote17

An initial draft of the new law was sent to the Minister of Finance at the end of January 1926.Footnote18 In the following months, a second more detailed project was prepared,Footnote19 evolving finally into the final royal decree in September (Regio Decreto Legge 7 settembre 1926, n° 1511)Footnote20 and its implementing decree in November (Regio Decreto 6 novembre 1926, n° 1830).Footnote21 A public register of all deposit-taking institutions (Albo delle aziende di credito, henceforth Albo) was instituted at the Ministry of Finance. New banks, branch openings, mergers and acquisitions should be authorised by the Ministry, after the BoI advising. Minimum levels of capital were set according to the bank’s geographical area of operation.Footnote22 Banks had to regularly send accounting reportsFootnote23 and balance sheets to the BoI, which was entrusted with supervisory powers. This power entailed inspecting supervised banks. Banks had to add to reserves at least a tenth of annual profits, up to 40 per cent of overall capital. The first decree left the definition of specific capital and risk requirements to a second implementing decree, which defined minimum levels of capital, a capital to deposits ratio and maximum exposure on a single lender for commercial banks.Footnote24 It left the supervision of saving and pawn banks under existing legislation.Footnote25 Rather small pecuniary sanctions were set for the infringement of these requirements, while in extreme cases the authorisation to collect deposits could be withdrawn. In , we show how the regulatory provisions evolved from the first law proposal in January to the definitive law in September-November 1926.Footnote26 It is evident how the requirements were attenuated from the second to the final draft. The liquidity requirement to cover at least half of short-term liabilities with short-term assets was cancelled. The maximum exposure towards a single lender was increased from 15 to 20 per cent.Footnote27 The minimum capital to deposits ratio was reduced from 10 to 5 per cent. Furthermore, banks had respectively 3 and 4 years to comply with the last two provisions, giving the discretion to the BoI to allow further extension in specific cases.

Table 1. the watering down of the 1926 banking law.

This overall ‘watering-down’ of the legislative provisions can be easily attributed to lobbying pressures. We have explicit evidence of these pressures in the correspondence of the head of the Italian Banking Association (ABI), Giuseppe Bianchini, with Alberto BeneduceFootnote28 and with the Minister of Finance.Footnote29 Notwithstanding the recent banking crisis, Bianchini still supported market discipline as the sole effective protection for deposits holders. For Bianchini, no additional regulation would be needed, as the enforcement of existing ones would suffice. According to him, Government intervention in the banking sector would be not only ineffective, but also counterproductive: it would raise moral hazard issues in banking activity, and put bank management under the will of politicians or ministerial officers. Then, in case of distress, the responsibility would have fallen onto the Government. Regarding bank-industry linkages, Bianchini argued that Italian economic development still depended on universal banks financing. Also, Federico Flora, a notable scholar involved as a consultant for the new law project, shared Bianchini’s scepticism about introducing new rules in the banking sector.Footnote30 Later on, as the enactment of the law became certain, Bianchini moved towards a ‘lesser evil’ strategy. This consisted of arguing for softening the new rules, introducing flexibility according to the type of bank, and assigning supervisory powers to the BoI.

Thus, the choice to appoint the BoI, rather than the Ministry of Finance, as the supervision authority stemmed from a direct request of the banking sector. This is remarkable, considering that the BoI was still a competitor of other banks.Footnote31 Nevertheless, the BoI’s involvement would avoid the much distrusted political intrusion in the banking sector. Furthermore, it was expected to act more prudently in restricting banks’ deposit-taking, as it would have endured its consequences in terms of additional demand for liquidity. The Finance Minister himself, Giuseppe Volpi, called the appointing of the BoI as ‘cutting the Gordian knot’.Footnote32

One of the few strengthening elements of the law, compared to the previous drafts, was a more explicit definition of the supervisory powers: banks had the ‘obligation to produce all documents to the officials required for the exercise of their powers’. A subtle interpretation of this provision significantly enhanced the enforcement of the law, as explained in the next sections. A first evidence of that can be traced in some correspondence between Bianchini and Stringher at the beginning of the supervision activity.Footnote33 The former complained that banks were being requested a fine disaggregation about financial statements, consisting in almost a duplicate of internal accounts, apparently going beyond law requirements, which were de jure limited to capital ratios and risk concentration. Stringher replies that ‘financial statements […] are formed with the most different criteria, and in most cases they are so synthetic and incomplete to prevent those who read them from obtaining clear knowledge’.Footnote34 Thus, the BoI needed to ask for such detailed information in order to correctly assess regulatory compliance.

As it might be expected, the first few months were characterised by hostility towards the fledging supervision. Political police archival documentations report several complaints, mostly from anonymous informants (Polsi, Citation2002): inspections would have been conducted with ‘incompetence’, and had been creating panic among deposits holders. Niccolò Introna, the head of the supervision department, was described as narrow-minded, lacking any kind of ‘flexibility’. A violent press campaign against Introna arose as a reaction to inspections involving the banks controlled by Alvaro Marinelli. Marinelli was an unscrupulous businessman heading an industrial-banking group with connections with prominent figures of the fascist Party, a case in point of the so-called ‘wildcat banking’ (Conti, Citation2004).Footnote35 Later on, he was arrested for fraudulent bankruptcy.Footnote36 Nevertheless, from late 1928, even evidence from political police signals a more favourable general attitude towards supervision (Polsi, Citation2002).

While banks initially displayed a sceptical and hostile attitude towards the BoI’s pervasive supervisory power, such mistrust between the supervisors and the supervised waned rather quickly and developed into an increasingly cooperative environment. By the 1930s, it seems that commercial banks had started to appreciate and willingly accept BoI’s action as supervisor. According to an internal memorandum summarising the activity of the BoI’s supervision in 1933:

It is worth highlighting the fact that today the very credit firms that are subject to supervision nearly always explicitly acknowledge the effectiveness of the supervising institution, that, ultimately, restored the necessary prestige to banking institutions.Footnote37

This does not seem to be just the opinion of a complacent supervisor.Footnote38 After WWII, even the Italian Bank Association suggested that the BoI’s supervisory powers could be extended, and the BoI was allowed to obtain even more pervasive information. One of the issues discussed in the Economic Commission report to the 1946 Italian Constituent Assembly was whether the BoI should be allowed again to discount to the market like a commercial bank, as this granted high-quality information on the market conditions. The position expressed by the Italian Bank Association on this matter reveals how its perception of BoI’s pervasive supervision had changed (in positive):

Direct discount to privates, although it offers the possibility of a better point of view on the market and its understanding that can be useful for its credit policy, does not seem to be the only way to achieve this: even now the Bank of Italy has a perfect understanding of the economic situation, through its peripherical branches and supervision framework: this function can be further developed by acquiring precious elements of judgement.Footnote39

The fact that the Italian Bank Association was explicitly in favour of a broader development of the BoI’s supervision functions is evidence of the cooperative environment that had been established between the BoI and its supervisees. A generally positive view on the operation of the supervision functions by the BoI is also noticed in most of the interviews with bank managers and representatives of the banking industry.Footnote40 It shows that banks did not consider the BoI’s supervision as a threat and did not try to lobby to ease it. Quite the contrary, the Italian Bank Association even suggested its supervisory powers should be enhanced so that the BoI’s understanding of the market through supervisory disclosure was improved.

Before discussing supervision operability, it is worth tackling the issue of independence of supervision authorities from political pressures, given the dictatorial nature of the fascist regime. Albeit formally independent, it is accepted in the literature that the Bank of Italy’s independence with regards to monetary policy was poor, as exemplified by this quote of Montagu Norman, in a letter he wrote to Hjalmar Schacht on 5 November 1926:

Stringher is about 70 years old, and I guess has no more independence than the tail of a kite. If he is a wise man, he is probably happier without it, for the powers exercised by the Fascisti leave no room for independence.Footnote41

However, the impression that emerges from this study is that the Bank of Italy retained a fair degree of independence concerning banking supervision.

The gatekeeper of banking supervision independence was Niccolò Introna, vice-Director General of the Bank of Italy and head of supervision. Introna had spent his whole career at the Bank of Italy: exceptionally talented and prepared, he was seen as a natural successor to Stringher for the governorship. Nevertheless, his career was always crippled due to his political and religious beliefs, being regarded as an anti-fascist and being a Protestant (Gigliobianco, Citation2004). At the same time, the regime left him at this place till its end, probably to avoid repercussions in terms of banking trust. An explicit political intrusion such as the removal of Introna might have sent the wrong message to the public, with potential adverse effects on financial stability.

Regarding supervision, the Bank of Italy adopted a stance of ‘passive resistance’ : avoiding a direct confrontation with the fascist regime, while using technical arguments to rein in attacks from politics. For example, in 1928, many prefects asked the branches of the BoI to disclose information on local banks’ financial stability.Footnote42 But the BoI was adamant on this point and refused to do so.Footnote43 The matter of supervision was indeed utterly technical, and only a few people who had been acquainted with it because they had worked for it could handle it without the risk of inconvenient spill-overs. In other words, it was difficult for the regime to interfere in something that not only politicians did not understand properly, but whose function and practices were obscure even to some insiders.Footnote44

Two important studies by Conti et al. (Citation2003) and Conti and Polsi (Citation2004) on cooperative joint-stock banks and saving banks confirm the attitude of the fascist regime of avoiding encroaching excessively on banking business. While their starting hypothesis was that Fascism tried to take control of these essential nodes of local power, as one would expect from an authoritarian regime, they conclude with an opposite interpretation.

3. The organisational setting

The set-up of the supervisory framework was marked by a detailed letter of instructions written in March 1927 by Stringher to the BoI’s local branch directors.Footnote45 A key aspect of the new system was a substantial degree of decentralisation towards local branches. This was motivated by operational efficiency purposes and by the aim of taking advantage of locally available information. In fact, the Bank of Italy already had to have at least one office in each province.

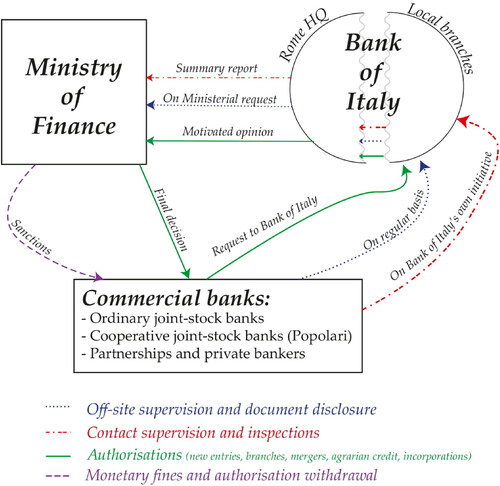

The operation of Italian supervision on commercial banks involved three sets of actors, as we display in : supervised commercial banks, the BoI, and the Ministry of Finance.Footnote46 In case of monetary sanctions or withdrawal of authorisations, the BoI’s role was receptive, as it only notified infringements to the Ministry of Finance, which would then take its decisions. However, the (lack of) documentation on sanctions in the archives suggests that fines were applied very rarely: if banks did not abide by the law, moral suasion – even through political authorities – seemed to be the preferred way to enforce it. In the following subsections, we describe the authorisation process for new banks and branches, inspections, and off-site supervision.

3.1. Authorisations

Commercial banks had to apply to the BoI for authorisation to start operations, to open new branches, and to merge. Demands had to be motivated and sent to BoI’s local branches, which in turn would send them to Rome with a preliminary evaluation, taking into account local banking market saturation. Indeed, the Rome headquarters asked branch directors to express a structured opinion, which was attached to the application file sent to the Ministry of Finance. The Ministry of Finance took the final decision, which in the vast majority of cases, but not always, followed the BoI’s advice.Footnote47 In their preliminary evaluation, BoI branches usually accounted for the number of already operating bank branches, the population and the level of economic activity in the surrounding area. Interestingly, the latter was usually assessed with soft rather than hard information (for example, data from the 1927 industrial census were hardly mentioned). BoI branches also considered the credit market segment in which the new branch would operate. For example, a local bank focussing on credit to small and medium enterprises would be welcome where only saving banks and national banks were present.

To be authorised to start trade, the law requested that new banks have a minimum level of paid-up capital, differentiated by geographic scope of activity.Footnote48 According to the law, these requirements were binding only for new banks, by which existing banks were not required to abide. However, at least in a few cases, these levels were also made binding for old banks. For example, Banco Abruzzese was a bank operating at the regional level in the Abruzzo region but with only 5 mln lire capital. In March 1927, the bank asked for authorisation to open a new branch in Pescara. The supervisors agreed to ask the bank to raise its capital to 10 mln in order to authorise it.

In the eyes of contemporary observers, the barriers to entry introduced by the law were conceived to enhance financial stability and avoid overbanking. According to the BoI:

the easiness to collect deposits during paper inflation years [post-WWI] favoured the mushroom of several banks lacking adequate capitals, and perhaps competent directors. This pushed old and new banks to extend their action abnormally, setting up costly branches to absorb banknotes, even at high-interest rates.Footnote49

Even after WWII, the Economic Commission Report to the 1946 Italian Constituent Assembly acknowledged:

In fact, it wasn’t a theoretical concept that pushed for the introduction of the supervision on opening new branches, but rather the experience of the dreadful consequences of the free expansion of banking facilities that took place between 1919 and 1926.Footnote50

Despite the new authorisation system, between November 1926 and February 1928, the BoI received 895 requests to open new branches. According to the BoI:

this expansionary trend gained momentum right after the publication of the [1926] decrees, driven by small and medium banks that had lagged behind and wanted to ‘buy out’ the largest number possible of market places before other competitor banks asked for them.Footnote51

To shore off this phenomenon, the Ministry of Finance decided to introduce a temporary banFootnote52 on new branches in September 1928,Footnote53 and it lasted throughout the period relevant for this research,Footnote54 even though the Ministry of National Economy pressurised to lift it in December 1929.Footnote55 Some exceptions were indeed accorded,Footnote56 especially concerning cases of banking distress management, where the authorisation to open branches was given as quid pro quo to healthy banks intervening in rescuing distressed ones.Footnote57

According to Polsi (Citation2002), the sheer obligation for banks to be publicly registered contributed to purge the weaker (if not fraudulent) elements out of the system. In the city of Naples, he estimated that in late 1926 around 80 banks existed, but only 57 registered in the Albo, the remaining being too small or disordered to operate properly. By the end of 1929, only 47 banks were still operative and were all registered in Albo (9 of them being already in liquidation). In this perspective, the BoI actively encouraged the consolidation of the banking system through mergers and amalgamations.Footnote58 In 1928, the BoI reported:

It is useful to remind that the concentration should be cautiously favoured, with the goal of clearing the field where it appears plethoric, and when amalgamation results in stronger bodies that can better serve credit needs.Footnote59

And again in 1930:

The Bank of Italy, in the face of the truly plethoric number of banks existing, has considered favourable to support, broadly speaking, bank amalgamations […] and this not only to favour a general reduction of the expenses, but also to limit competition on the ‘snatching up’ of deposits, which detrimentally affects interest rates.Footnote60

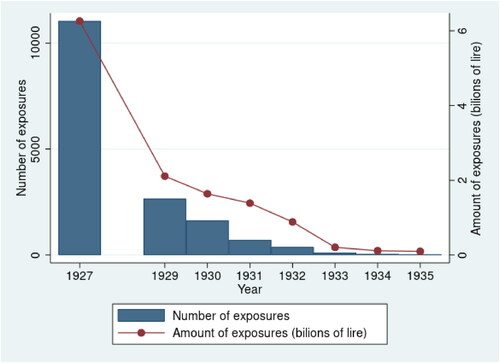

While for most matters the Bank of Italy was an advisory body on authorisation, there was one aspect in which its advice was binding and did not require the Ministry of Finance’s endorsement: the risk concentration provision which forbade outstanding uncollateralised credit on a single lender exceeding 20 per cent of capital. The law explicitly stated that temporary forbearance could be formally accorded, but this rather technical authorisation had to be given by the Bank of Italy, not the Ministry of Finance. As we mentioned in the second section, tight industry-bank linkages were at the core of the Italian banking system’s fragility. This norm dealt partially with this issue, by cutting the lending linkages, albeit not the ‘equity’ linkages, namely the extensive stock holdings in bank balance sheets. As of the beginning of 1927, the amount of these credit exposure exceeding this provision was around 11 billion of lire (), which amounted to around a fourth of overall bank lending.Footnote61 The apparent rationale of the norm was to diversify banks’ risk rather than to increase capitalisation. Nevertheless, archival evidence suggests that the most common way to comply with this rule was to increase its equity so that the share of the main credit would fall below 20 per cent of it. A few times, banks increased equity in order to enjoy more flexibility in future credit allocation. At any rate, archival evidence suggests that quite frequently this constraint was binding.Footnote62 The amount of excess credit exposure fell quickly from 11 billion in 1927 to less than 2 billion after three years, being negligible afterwards.Footnote63

3.2. Inspections

According to the above-mentioned instructions sent by Stringher to the BoI’s branches, on-site inspections should be gradually planned for all banks. In case of troubling situations, their timing should be anticipated, unless these troubles were of public knowledge: indeed, inspections should carefully avoid stirring fears among the public. Inspections were triggered by the BoI’s headquarters, which would ask the branch directors to organise them and would occasionally send ad hoc officers from Rome or other branches in support. Even though suggestions were made by both the Ministry of Finance (often prompted by information from other Ministries such as that of the Interior), and local directors, inspections were at the BoI’s headquarters sole discretion. The local director was responsible for the inspections carried out within their area, even if these were carried out by inspectors sent from elsewhere or delegated to senior officers of their own branches. Final supervision reports were written by the officers who personally carried out the inspection but had to be approved and sent by the directors. A copy of the inspection report was sent to the BoI in Rome. A much shorter summary of the inspection findings was sent to the Ministry of Finance by the head of supervision (Niccolò Introna) or the Governor of the BoI himself (Bonaldo Stringher and later Vincenzo Azzolini).Footnote64 The communication on banking supervision was dealt with at a very high level. Initial drafts, written by secretaries and less senior officers, were often amended. Azzolini, Stringher, and Introna were personally and scrupulously following the matter of banking supervision at each stage, as it appears from the hand-writing of the revision. This procedure applied to all banks, regardless of their size or importance.

As we mentioned, bank inspections started in early 1927. Between 1927 and 1935, the BoI carried out 3,230 on-site inspections, but not all categories of banks received the same attention. Polsi (Citation2002) says that smaller banks received the most attention, while large universal banks were not inspected until the late 1930s. This is certainly true, but provides a more comprehensive picture. Considering the area of operations of supervised banks, an interesting trend emerges: interregional, regional, and provincial banks, i.e. banks with a branch network, received comparatively more attention than local unit branched banks. By the end of 1930, the percentages of inspected banks in these categories were 68 per cent, 72 per cent, and 81 per cent, respectively. This signals BoI’s doubts about the stability of branched banks and confirms that the overexpansion of bank networks was indeed one of the main concerns that motivated the establishment of the supervision system.Footnote65 The lack of inspections to major banks is well-known in the literature and widely criticised (Gigliobianco & Giordano, Citation2012; Guarino & Toniolo, Citation1993). However, as Polsi (Citation2002) maintains, it would have been very difficult to start inspecting the largest banks from the very beginning for logistical and organisational problems. The archival research carried out for this work largely confirms this claim. For example, the on-site inspection of Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura, the smallest of the large national banks, lasted more than a month (from 26th June to 6th August 1931), while, by contrast, the inspections of small banks did not take more than few days.

Table 2. Bank inspections by area of operations 1927–1934.

Lacking an ad hoc body of inspectors, inspections distracted highly qualified personnel from the ordinary business of the BoI, and there were often complaints from the branches regarding the lack of personnel.Footnote66 This created an extra burden on the busiest branches of the BoI, which were often those where more banks were headquartered (for an account of this evidence, see Appendix B.1). Overall, at an earlier stage, inspections were usually conducted by ordinary officers that were appointed temporarily as inspectors. From the 1930s onwards, task specialisation increased, inspections being more frequently assigned to a selected group of people, who often had to travel around to perform their tasks. At the same time, there is a convergence in the standards of inspection reports. Whereas in the late 1920s, the structure, lengths, and information given in reports were very heterogeneous, we see an increasing convergence towards standardisation in the early 1930s – with more detailed information. At the current stage of research, narrative evidence suggests the hypothesis of a gradual standardisation and professionalisation of on-site supervision practices. In fact, the format of inspection reports in the early 1930s resembles the structure and style of post-1935 (and even post-WWII) reports.Footnote67 This would suggest that the output of the process of trial and error in the late 1920s/early 1930s had a long-lasting effect in shaping BoI’s supervision practices. This interpretation is confirmed by the judgement of Paolo Ambrogio, Chair of the Supervision Service of the BoI.Footnote68

Inspections were indeed a powerful tool in the hands of the BoI, and allowed to better enforce existing rules, which previously remained dead letters. The 1882 Code of Commerce (art.146), which applied to all joint-stock companies, stated the obligation for banks to cover incurred capital losses.Footnote69 But this provision could be ignored if the board of directors and auditors hid the losses in the hope of covering them with future profits. The new supervisory mechanism, and the related obligation for banks to disclose all requested documents, allowed for its enforcement in such a way that was not possible before: BoI’s supervisors were able to compute unrealised losses in bank balance sheets and to ask banks to cope with it.Footnote70

3.3. Off-site supervision

With regards to off-site supervision and document disclosure, commercial banks had to send their documentation (i.e. balance sheets and call reports) to the BoI, which promptly reminded them in case they were late in abiding by the rules. Occasionally, the BoI would request additional documentation through its local directors to supervised banks, like details on the composition of the single balance sheets’ items, such as the nominatives and exposures of the ‘portfolio bills’ and ‘other debtors’, or the lists of ‘securities’ and the nominal vs market value they were priced in the balance sheets. This documentation was not forwarded to the Ministry of Finance, although it could be made available on demand. BoI’s officers would use the received information to compile a number of standardised supervision forms (Modelli di vigilanza) that provided a quick summary of banks’ conditions. These were drafted every time accounting reports were handed in (once every two months for joint-stock banks, and once a year for private bankers). The purpose of these forms was to provide a quick overview of the condition of the bank. The content and structure of these forms evolved over time, increasing in details and standardisation.Footnote71 These forms were useful in signifying banks experiencing haemorrhaging deposits or abrupt swings in suspicious balance sheet items – these being events that should be already highlighted by local directors, but this allowed a double-check by the BoI’s headquarters.

While the law gave the BoI explicit powers to request documents useful for the ‘performance of its duty’ during inspections, it was less clear about the documents to be disclosed during off-site supervision, i.e. by mail. Analysis of off-site supervision reveals a trend of increasing disclosure to the supervisor, even beyond the text content of the law, and an increasing information standardisation both to the public and to the supervisor. Having observed the operational limits and burdens of on-site supervision, it is easy to acknowledge the importance of enforcing information disclosure through the relatively more efficient off-site supervision.

According to the law, banks only had to submit balance sheets and accounting reports (respectively yearly and bi-monthly) to supervision.Footnote72 These documents were sent to the local director of the BoI’s branch, who would send them to Rome with a comment.Footnote73 In the beginning, received accounting reports were de facto a duplicate of the publicly available monthly reports that joint-stock banks already had to submit every month to local tribunals (according to art. 177 of Code of Commerce).Footnote74 Furthermore, the BoI soon realised that the accounting standards used by banks were very heterogeneous. After a discussion in late 1928 between the BoI and the Ministry of Finance,Footnote75 the solution was to adopt two sets of accounting reports: one for the public and one for supervision purposes. With the Regio Decreto 20 December 1928 n° 3183, a new standardised form for the public accounting reports was introduced for all joint-stock banks. Asked by the Ministry of Finance to give their opinion on the new public form, the Ministry of National Economy replied:

This [new form] aims to give the accounting reports the best possible clarity so that the public can make a useful read-out of them and take into consideration the current state of banking accounting practices, and the need of not creating extra expenses for banks with the request of additional documents, and finally the need of not disclosing information that it is inconvenient to disclose. It seems to be an equitable solution to conflicting issues.Footnote76

The new public form was more synthetic than the previous one, apparently disclosing less information. However, lacking standardised accounting standards, banks often misclassified balance sheet items in order to hide their wrongdoings. Very few banks filled the ‘bad loans’ item (sofferenze) correctly, while most banks left this item blank and disguised bad loans under other items. The Ministry of National Economy reported that the Fascist Banking Association, sitting in the commission that studied the solution to adopt, ‘committed to making sure that banks will fill in all the items of the new form, whereas it is well-known that in the current form […] most of these items were left blank’.Footnote77 On public reports, the trade-off between more but less accurate information or less but more certain and homogenous information was resolved in favour of the latter. The solution was adopted in full agreement with banks. At the same time, however, a more detailed form was introduced for supervision purposes only. Indeed, this supervision form reported the full information (including for example items such as ‘unrealised losses’, and ‘bad loans’). In particular, under the previous public form, a bank could assign bad loans to different balance sheet items, while in the new form they would be included in the ‘other credit’ item. In the supervision form, the ‘other credit’ item would be displayed in a disaggregated form, so that the exact amount of bad loans would be known to supervisory authorities. This solution highlights the pragmatic approach of supervision authorities: rather than trying to impose from scratch a full disclosure, which would have created strong incentives for banks not to collaborate, they adopted a compromised solution that guaranteed banks’ cooperation, a full disclosure of information to supervisors, and made more homogeneous and consistent, although less detailed, the publicly available information.

Besides ‘Bad loans’, deposits were another problematic issue that was treated differently in official and supervision reports. For tax purposes, banks often hid household deposits among business deposits (correspondent accounts). To ensure the cooperation of banks with supervision authorities, the BoI allowed banks to continue doing so in official reports but accounted for the disguised deposits in calculating the capital-to-deposits ratio. This practice recalls an important matter in the economics of banking supervision, namely the trade-off between market disclosure and the disclosure to the supervisor (Prescot 2008). In these years, it is evident that the BoI sacrificed the former to enhance the latter. This was applied at the expense of fiscal compliance. An explicit guarantee that supervision inspections would not disclose compromising information to tax authorities was given by the Governor of the BoI, Stringher, to the Head of the Italian Bank Association in a letter sent on 23rd July 1927.Footnote78

As we mentioned in section 2, the obligation for banks to provide whatever internal document or information requested and forward by mail to the BoI officials was probably the most relevant innovation in the enforcement practice, compared to the 1926 law. Initially, supervised banks tried to resist the BoI’s requests for additional documentation, such as their clients’ nominative lists and their portfolios’ details. After initial resistance, the BoI managed to impose that the generous information requirement for on-site supervision was also extended to off-site supervision. This was achieved when a bank in Turin refused to disclose information on its clients through off-site supervision, lamenting that the law authorised the BoI to ask for this kind of information only during inspections. The BoI resisted the lobbying of the Associazione Bancaria Italiana and argued through analogies that this was in fact in the banks’ interests. Too frequent inspections could damage their reputation.

This paradigmatic episode (described in Appendix B.3) exemplifies some interesting aspects of the operation of banking supervision and the way its function evolved and consolidated. First and foremost, it shows that the actual implementation of supervision took advantage of subtle arguments of the BoI to expand the actual provision well beyond that stated in the law. The type of documentation the BoI could require not only during on-site supervision, but also through off-site supervision, was the broadest possible. At the same time, however, the BoI did not do it arbitrarily, but ingeniously used analytical reasoning to expand through analogies what the law already stated. Secondly, it is important to stress that the BoI guaranteed in exchange not only the highest level of secrecy,Footnote79 but also made it crystal clear that under no circumstances would the information obtained through supervision be used for tax purposes.Footnote80 This was reiterated in the correspondence with both the Italian Bank Association and the Turinese bank. Thirdly, this episode highlights the intransigent stance of the BoI, or at least by Stringher, with respect to lobbying to water down the law after its enactment. As banks acknowledged the legitimacy of full disclosure during inspections but refused full disclosure via mail, the banks were put up against the wall: if they did not want to submit information via mail, then the BoI would have taken advantage of its on-site inspection powers to obtain the same results, but with a potential loss in term of credibility for the stubborn banks. Fourthly, intransigency was coupled with tactfulness: when inspections might have threatened to spread panic in Turin, Stringher chose to prioritise financial stability rather than proving his point. Eventually, the BoI obtained what it wanted and secured supervisory powers that went well beyond the letter of the law. The mandated disclosure of any document required in off-site supervision settled as a consolidated practice and finally became law in 1936.

4. Conclusions

This paper has investigated the establishment of Italian banking supervision following the 1926 law. While incomplete in size and scope by modern standards, at that time, this supervision mechanism was not common in European comparison. We highlighted how a narrow focus on regulation that does not take into account the day-by-bay operations and the actual enforcement of the rules risks to fall short of grasping the full extent of the regulatory and supervision framework.

We document gradually increasing on-site and off-site supervision undertaken by the BoI, although its action was limited by personnel scarcity in terms of size and skills. In this sense, the Italian case, as an incremental process characterised by learning by doing and constrained by political feasibility, is consistent with existing literature (Hotori et al., Citation2022; Mitchener & Jaremski, Citation2015). We also confirmed and emphasised the relevance of supervisory trade-offs, ranging from public disclosure to resource allocation according to bank size, whose delicate balance is a crucial task for supervision choices. Rules enforcement does not come out of the blue, but instead, it is the result of the complex and troublesome task of building a supervision mechanism from scratch.

Concerning the well-known rules-based versus discretion dilemma (White, Citation2011), we deem that our paper posits a rather specific interpretation. A substantial degree of discretion allowed to better enforce the law content (the ‘spirit’ of the law) and to fill some of the gaps and ambiguities (the ‘letter’) of that law. By discretion, we do not mean arbitrariness but rather a proactive approach that went beyond a mechanical check of mandated capital and risk concentration ratio. This is particularly meaningful as, generally speaking, some extent of incompleteness and ambiguity is probably to be expected in any regulatory framework.

Such a nuanced version of the discretionary capacity appears as a defining aspect of the relationship between regulation and enforcement. In our case, it encompassed mandating information requirements that allowed detailed analysis of balance sheet items and even individual credit exposures, as well as the inclusion in capital to deposit ratios of household deposits disguised for tax purposes. Even the enforcement of pre-existing provisions (like loss coverage mandated by the Code of Commerce) helped to foster the purpose of the law of capital adequacy.

Notwithstanding the lack of a strong sanctioning mechanism, substantial enforcement seems to have occurred through moral suasion. After an initial period and reassurances on information confidentiality, supervised banks seemed mainly cooperative. This is confirmed by the overall positive judgement on supervision expressed by banking industry members in the surveys reported by the post-WWII Constituent Assembly works. However, this cooperation was assured with substantial concessions on bank secrecy.

In building the new supervisory mechanisms, the ability to properly collect information emerges as key. Minimising asymmetric information between the supervisor and the supervisees recalls one of the most important justifications for the assignment to the central bank of supervisory powers, i.e. information synergies with lending of last resort. This function chiefly relies on distinguishing between illiquid and insolvent banks during financial panic events to assist the former but not the latter (Bignon et al., Citation2012; Jobst & Rieder, Citation2016). In our study, we encountered many instances where the BoI used information acquired through its supervision activity to determine whether or not a bank deserved emergency liquidity assistance.Footnote81 However, this preliminary evidence deserves more systematic research to be confirmed.

Indeed, the period covered in this research coincided with the unravelling of one of the worst banking crises in European history. In this article we have intentionally avoided to discuss whether the establishment of banking supervision before the Great Depression had an effect in mitigating the banking crisis in Italy. Our goal was to document the establishment of the banking supervision and its operation, not assess its impact. Recent research, however, has shown that Italy experienced a hidden banking crisis that was resolved secretly by Italian banking authorities (Molteni, Citation2021). All hard and soft information employed in the crisis management of small and medium bank distress was produced by the Bank of Italy’s supervision officers. Elsewhere, we advanced the educated guess that had banking supervision not been introduced in 1926, the banking crisis would have been more severe (Molteni & Pellegrino, Citation2021). Confirming or confuting this hypothesis seems a promising research path.

Disclaimer

The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Bank of Italy. Part of this article previously appeared as preprint working paper in: Molteni M., Pellegrino D. (2021) ‘Lessons from the early Establishment of Banking Supervision in Italy (1926–1936)’ Bank of Italy’s Economic History Working Papers, n°48.

Acknowledgements

We thank Brian A’Hearn, Federico Barbiellini Amidei, Paolo Croce, Paolo di Martino, Eric Monnet, Lanfranco Suardo, Kilian Rieder, Mauro Rota, Gianni Toniolo, Maurizio Trapanese, participants to Associazione per la Storia Economica (ASE) Annual Meeting, Rome September 2021, Humboldt University Online Research Colloquium, June 2021, and two anonymous referees for useful suggestions. We thank the editor Adoración Álvaro Moya for assisting during the submission process. We also thank Alberto Baffigi, Elisabetta Loche, and Renata Martano for guidance and assistance in archival research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Marco Molteni

Marco Molteni is a Post-Doctoral Researcher on the ERC funded project Global Correspondent Banking 1870–2000 (P.I. Prof. Catherine Schenk) at the Faculty of History, University of Oxford. He completed his DPhil in Economic and Social History at Pembroke College (Oxford) and wrote his thesis on banking distress, development, and supervision in Fascist Italy (1926–1936). Previous to this, he studied at the University of Milan (BA in History) and at Warwick University (PG Diploma in Economics). He is currently one of the editors of the Oxford Working Papers in Economic and Social History.

Dario Pellegrino

Dario Pellegrino is an Economist at the Economic History Division of the Bank of Italy. From 2013 to 2017 he worked as Economist at the Regional Economic Analysis Division at the Milan Branch of the Bank of Italy. He studied economics at Bocconi University, Milan (BA and MSc). Before joining the Bank of Italy, he worked as consultant for the OECD in Paris.

Notes

1 The USA, the UK, Japan, Sweden, Belgium, France Switzerland, and Germany.

2 In France, banking supervision was introduced in the 1941 bank act under German occupation, which was confirmed and strengthened in 1945 (Quennouëlle-Corre & Straus, Citation2010). UK introduced its first formal supervision in 1979, although Bank of England already exercised an informal supervision on the banking system throughout its role of liquidity provision: Grossman (Citation2010).

3 It would be the fourth if we take into account USA, with whom a comparison would be complicated by multiple layers of regulation and supervision at federal and state level. Refer to (White, Citation2011, Citation2013).

4 Archivio Storico Banca d’Italia, Banca d’Italia, Vigilanza sulle Aziende di Credito. From now on, ASBI, Vig.

5 Archivio Centrale dello Stato, Ministero delle Finanze, Direzione Generale Tesoro, Ispettorato generale per i servizi monetari di vigilanza e controllo, Ufficio tutela del credito e del Risparmio.

6 For a detailed description of the documental material available in Italian banking supervision archives we refer to Molteni (Citation2020).

7 Following Mishkin (Citation2000), ‘supervisory approach’ here is used to distinguish it from a ‘regulatory approach’.

8 Cit. ‘Interrogatorio del prof. Giovanni Nicotra’ in Ministero per la Costituente (Citation1946), vol. 2, p. 111.

9 Under Legge 15 luglio 1888, n° 5546, subsequently reformed in 1927–1931: Regio Decreto Legge 10 febbraio 1927, n° 269; Testo Unico 25 aprile 1929, n° 967; Regio Decreto 5 febbraio 1931, n° 225. Some limitation on saving banks branching was imposed in 1923 to prevent saving banks to open branches in municipalities where another saving bank was already operating (Regio Decreto Legge 21 ottobre 1923, n° 2413).

10 For a detailed account of these projects, refer to Cajani (Citation1938) or Gigliobianco and Giordano (Citation2012). Here we just discuss the most prominent projects.

11 Member of the Lower House.

12 Eugenio Chiesa was a member of the Lower House.

13 One notable exception was Sweden, where banking supervision was not performed by the central bank, but the Ministry of Finance.

14 Banca d’Italia (1928), p. 56.

15 Until 1926, the BoI, although being in charge of most of the Italian money circulation, shared issuing rights with Banco di Napoli and Banco di Sicilia.

16 letter of Mussolini to Giuseppe Volpi of the 8 August 1926, doc. 88 in Cotula and Spaventa (Citation2003).

17 A research on the Corriere della Sera (one of the most prominent Italian newspaper) reveals that in the years immediately preceding the enactment of the 1926 law, mentions of scandals related to bank failures were very frequent. Inter alia: Cassa Rurale di Bagnolo (Bankruptcy 31 st May 1923); Banca Nazionale del Reduce (Bankruptcy 29th July 1923); Banca del Lavoro e della Cooperazione (Bankruptcy 24th August 1923); Banca di Credito e Valori di Roma (Bankruptcy 16th January 1924); Credito provinciale Modenese (Bankruptcy 21st January 1924); Banco San Lorenzo di Genova (Bankruptcy 27th February 1924); Banca dell’Associazione Agraria Parmense (Bankruptcy 10th March 1924); Banca Agricola Industriale del Sannio (Bankruptcy 21st May 1924); Banca Commerciale di Terra di Lavoro (Bankruptcy 17th June 1924) Banca Adriatica (Stopped payments 13th October 1924); Banca Centrale di Cambio di Milano (Bankruptcy 14th April 1925).

18 Letter of Bonaldo Stringher to Giuseppe Volpi 10 February 1926, doc. 71 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993). The draft is reported in doc. 69 in the same reference. In this letter, Stringher states that the draft was a joint work of the same Stringher, Gustavo Bonelli (a BoI’s lawyer), and Alberto Beneduce. From Bonelli notes, commenting on the first draft and suggesting revisions (doc. 68, ibidem), it seems that the same group of people wrote the second draft.

19 Doc. 72 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993). The timing is uncertain, being around spring or summer of 1926.

20 Doc. 76 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993).

21 Doc. 81 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993).

22 A new bank which wanted to operate at the national level must have a capital of at least 50 mln lire. A regional bank 10 mln lire, a provincial bank 5 mln lire. Cooperative joint stock banks that operated at provincial level must have a capital of 300,000 lire.

23 Here, we refer to these accounting reports as ‘call reports’, as these were the equivalent of the ‘call reports’ in the US banking system.

24 The definition of ‘commercial banks’ encompasses all profit-oriented institutions that accepted deposits, in particular ordinary-joint stock banks (banche ordinarie), cooperative joint-stock banks (banche popolari), and private bankers (ditte bancarie).

25 Saving banks and pawn banks collecting deposits were under the supervision of the Ministry of National Economy since 188: Legge 15 luglio 1888, n° 5546; Regolamento 21 gennaio 1897, n° 43. New provisions for saving banks were adopted with Regio Decreto Legge 10 febbraio 1927, n° 269 and Regio Decreto Legge 26 aprile 1929, n° 967. However, disclosure of balance sheet and call reports to the Bank of Italy and maximum lending exposure applied also to saving banks and pawn banks collecting deposits.

26 Table A1 in the Appendix summarizes all final provisions of 1926 banking law.

27 Note that this requirement was set for the first time in the 1923 draft, but with a lower threshold, at 10 per cent.

28 Alberto Beneduce was a prominent public executive, and the main architect of the 1936 banking law. He participated in the 1926 banking law as a member of the committee in charge of it.

29 A letter to Beneduce dates to the 2nd February. Two letters to Giuseppe Volpi dates to the 26th of August and the 2nd September. Minutes by Giuseppe Volpi Head of Cabinet, reporting Bianchini remarks, dates 26 September 1926. They are reported, respectively, as doc. 70, 74, 75 and 78 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993).

30 Federico Flora’s letter to Pasquale D’Aroma, 22 August 1926, doc. 73 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993).

31 BoI’s commercial banking activity was discontinued only in 1936.

32 Doc. 77 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993).

33 Bianchini’s letter to Stringher, dating 19 July 1927, Stringher’s letter to Bianchini, dating 23 July 1927, respectively doc. 178 and 138 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993). Bianchini sends this letter on behalf of Banca L. Marsaglia in Turin. See also ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1948, f. 1.

34 Cit. letter from Stringher to Bianchini, 23rd July 1927, published also in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993), doc. 138.

35 Marinelli was close to the fascist leader Giuseppe Bottai.

36 Note that, unlike in the Anglo-Saxton institutional context, in Italian legislation there was no distinction between bankruptcy and insolvency. Here, the term bankruptcy is used for any procedura concorsuale which applies to both companies’ insolvency and personal bankruptcy.

37 Cit. Promemoria dated July 1933, p. 9 in ASBI, Carte Baffi, Servizio Studi, prat. 52, fasc. 2.

38 In order to clarify the independence from the banking system, note that banks became owners of Bank of Italy shares in 1936, after being nationalized. Even there, substantial independence in terms of governance and operations, and in particular concerning supervisory activity, was de-facto guaranteed. Before 1936, the ownership shares were spread among the public: as of 1936, natural persons represented over 92 percent of overall ownership, while commercial and cooperative banks accounted for around 0.7. percent (Scatamacchia, Citation2008).

39 Cit. ‘Risposta al questionario n° 5; Associazione Bancaria Italiana’, in Ministero per la Costituente (Citation1946), vol. 2, p.332.

40 E.g. ‘Interrogatorio del dott. Raffaele Forcesi’, ‘Interrogatorio del dott. Ugo Foscolo’, ‘Interrogatorio del dott. Ambrogio Molteni’, ‘Interrogatorio del rag. Giovanni Goisis’, ‘Interrogatorio del dott. Nicola Carbone’, ‘Interrogatorio del dott. Antonio Rossi’, in Ministero per la Costituente (Citation1946), vol. 2.

41 Quoted in De Cecco (Citation1993), p. 259.

42 The Prefetto (Prefect in English) is an administrative figure not existing in the UK or the USA. Existing already in liberal Italy, the figure of Prefetto was reinforced by the fascist regime with Legge 3 aprile 1926, n. 660. Each province had its own Prefetto. They were the representatives of the executive power in the provinces and chaired the meeting of the provincial representatives of other ministries. They were the agency of the government in the periphery: what Mussolini was in Rome, the Prefetto was in the province. They depended on the Ministry of Home Affairs, whose charge was kept by Mussolini throughout the whole Ventennio

43 See for instance a letter from Stringher to the Ministry of Finance Mosconi on 26th September 1928. ASBI, Banca d’Italia, Vigilanza, Prat. 536, f.1

44 It is useful to remember the struggle of the Bank of Italy’s local directors to find good candidates to support them in inspections even among their senior staff.

45 Doc. 129 in Guarino and Toniolo (Citation1993).

46 Plus, all decrees authorizing new entries, branches, and mergers also needed to be signed by the Ministry of Agriculture and Forests, which was responsible for the supervision of saving and pawn banks.

47 Information on both BoI’s advice and the Ministry of Finance’s final decisions are available only for branches. Between 1926 and 1935, the BoI received 2244 applications for opening new branches, and expressed 1115 positive and 973 negative opinions (we do not know the outcome of 156 applications). Ministry of Finance authorized 886 new branches (∼80 per cent). However, while in 1926–1929 Ministry of Finance followed the BoI’s opinion 91.5 per cent of the times, in 1930–1935 the percentage dropped to 53.4 per cent. For an annual breakdown of these figures see Table A2 in the Appendix. Narrative evidence on mergers and new banks suggests the percentage was considerably higher for these kinds of authorizations.

48 See footnote n° 21.

49 Cit. Banca d’Italia (1929), p. 53.

50 Cit. Ministero per la Costituente (Citation1946), vol. 1 pp. 178–179.

51 Banca d’Italia (1928), p. 58.

52 A first, informal, suspension had already been declared by the Ministry of Finance, Volpi, for four months in March-June 1927. A file dedicated to the issue of new branch suspension is in ACS, Ministero delle Finanze, Direzione Generale Tesoro, Ispettorato generale per i servizi monetari di vigilanza e controllo, Ufficio tutela del credito e del Risparmio, Affari Generali, bb. 1, f. 17, sf. 3.

53 The ban was proposed in July 1928, ibidem.

54 This research could not define if and when the ban was removed, but it was still operative in 1935, as proved by a letter sent by the Ministry of Finance to the BoI on 5th August 1935 in ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 538, f. 1.

55 Letter from the Ministry of Agriculture and Forest to the BoI on 4 December 1929 in ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 537, f.1.

56 A note for the Ministry on 20th October 1931 allows to classify for which categories of banks the exceptions were made between 1929 and 1931: 31 new branches were allowed to national banks (Credito Italiano, 6; Banca Nazionale del Lavoro, 19; Banco di Roma, 6); 32 were allowed to saving banks, and 29 to commercial banks. ACS, Ministero delle Finanze, Direzione Generale Tesoro, Ispettorato generale per i servizi monetari di vigilanza e controllo, Ufficio tutela del credito e del Risparmio, Affari Generali, bb. 1, f. 17, sf. 3.

57 This mechanism deserves further attention in future research. One hypothesis is that in this way healthy banks were given monopoly rents that would compensate for the incurred losses of absorbing failed banks. Of course, this mechanism would only work if the branch market remained frozen, and no other bank could enter and compete.

58 Out of 269 applications for mergers, 223 were recommended by the BoI, and only 40 were advised against – for 6 applications we do not have information. By contrast, out of 59 applications for new banks, only 16 received a positive assessment by the BoI, and 36 a negative one (for 7 applications we have no information). See ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 11, f. 1,3,4,6–10; prat. 13, f. 2.

59 Cit. Banca d’Italia (1928), p. 57.

60 Cit. Banca d’Italia (1930), p. 46–47.

61 The amount of bank lending amounted to around 45 billion as of December 1926 (Cotula & Spaventa Citation2003). This number encompasses also collateralized lending.

62 On March 1927, Banca Lombarda di Depositi e Conti Correnti asked the BoI’s authorization to raise capital from 12 to 24 mln to tackle credits exceeding the 20 per cent (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1302, f. 1). On January 1927, Banca di Credito Canicattese set a capital increase from 200 to 500 thousands lire in order to have ‘more elasticity in granting loans’ (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1588, f. 1). In December 1928 an inspection to ‘Credito Industriale di Venezia’ reported several lines of credit exceeding the 20 per cent limit on capital. As it was asked to undertake actions, the bank replied announcing a capital raise from 15 to 30 mln lire (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1684, f. 1). On March 1927 Banca del Fucino asked to raise capital from 5 to 10 mln. While there is no explicit mention to the risk concentration requirement in this choice, that same bank struggled several times with it, asking for temporary exemptions (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1262 f. 1).

63 Figure 2 shows only uncollateralized credits that were outstanding before the enactment of the law. Details on new uncollateralized credit authorized by the BoI in 1927–1935 are available in Table A3 in the Appendix. The total sum of all uncollateralized credits authorized by the BoI in 1927–1935 was less than 2 billion lire, thus not a very large amount judged by pre 1926 law standards.

64 At the same time, the Bank of Italy in Rome wrote a list of transgressions and issues to fix and sent it to the relevant local branch to forward it to the supervised bank. The supervised bank was required to provide a written answer to all the points raised, specifying the measures that would take to fix them. Full reports were not disclosed to supervised banks. Local directors subsequently verified that the measures had actually been taken.

65 See for example Stringher’s concerns expressed in Banca d’Italia (1929), where he deplored the initiatives of many banks that tried to expand their branch network excessively ‘there is an evident necessity of avoiding ill-judged expansions that can be detrimental for the economic interests of the country’ (cit, p. 45).

66 At least until 1936, we do not find evidence of a fully developed centralised system of inspectors, which instead characterised the operations of Bank of Italy’s supervision in the post WWII era. Unfortunately, research on the personnel archives of the Bank of Italy has not helped to shed light on this interesting and important organisational issue.

67 Compare for example the inspection reports of Banca Nazionale dell’Agricoltura in 1931 (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1268, f. 1) and 1941 (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1301, f. 1), or the inspection reports of Banca della Lucania in 1931 (ASBI; Vig., prat. 1268, f. 1), in 1945 (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1271, f. 1), and in 1956 (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1272, f. 1).

68 Interviewed by the Economic Commission for the 1945 Constituent Assembly, Ambrogio stated that: ‘The supervision office of the Bank of Italy has continued its activities and functions as it was foreseen by the 1926 norms’; ‘Interrogatorio del Dott. Paolo Ambrogio’, in Ministero per la Costituente (Citation1946), vol. 2, p. 43.

69 Art. 146 stated that if the board of directors realized that losses were higher than 1/3 of the capital, the shareholder meeting had to be summoned in order to replenish the capital, acknowledge the loss and limit the capital to the new amount, or dissolve the company. If the losses were 2/3 of the capital, the dissolution was de jure if the shareholder meeting did not deliberate otherwise. Art. 146 also stated that if a company was in stato di fallimento the directors had to file for bankruptcy (fallimento) at the local tribunal.

70 For example, Banca Agricola Commerciale di Licata was inspected in December 1929, and was found with hidden losses (mostly due to the local tax collectorship service that the bank operated) high enough to trigger art. 146. The board of directors was asked to follow the provisions of art. 146 (January 1930). Initially, the directors responded that in their opinion the conditions of art. 146 were not met yet (February 1930), but agreed to guarantee the losses with their own funds. In addition, the income for the year 1929 was used to amortise the losses. Requests by the BoI to amortize hidden losses and clear the balance sheets were frequent. See for example: Banca Agraria di Riesi (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 1803, f. 1); Piccolo Credito S. Alberto di Lodi (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 6497, f. 1); Banca Latina di Ronciglione (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 7260, f. 1). In other cases, even when the rebalancing of the balance sheets was not triggered by the BoI, supervision authorities monitored closely the process, e.g. Banca Agricola Commerciale di Chieri (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 7907, f. 1).

71 The first version was very succinct, with very little information on the condition of the bank, focusing almost exclusively on whether the bank abided by the law provisions or not. This first version was replaced in less than a year with a more detailed one. For some banks the first forms were actually never employed, and the details from the very first call report are already transcribed on the second and more detailed form. This signals the flexibility of the BoI, which quickly amended the form after realizing that the first version was unsatisfactory. The third form, introduced in 1931, was a decisive upgrade in terms of information provided: as it also included few words on the outcome and the date of the last inspection, and it provided much more details on the balance sheet items. The format of the third form was marginally improved in the fourth version, but the content and information provided did not actually change significantly.

72 Private banks had only to disclose their annual balance sheet, whereas ordinary and cooperative joint-stock banks had to disclose their call reports every other month.

73 With the Numero Unico 24411, on 29th March 1927, Stringher complained with all BoI’s branches that sometimes Directors did not spend enough effort in commenting the documentation sent to Rome, and urged them to do so.

74 The call-reports sent to tribunals are those on which the ASCI dataset is constructed.

75 ACS, Ministero delle Finanze, Direzione Generale Tesoro, Ispettorato generale per i servizi monetari di vigilanza e controllo, Ufficio tutela del credito e del Risparmio Affari Generali, bb. 3, f. 42.

76 13th December 1928, ACS, Ministero delle Finanze, Direzione Generale Tesoro, Ispettorato generale per i servizi monetari di vigilanza e controllo, Ufficio tutela del credito e del Risparmio Affari Generali, bb. 3, f. 42.

77 Cit. Ibidem.

78 ASBI, Direttorio-Stringher, prat. 17, doc. 3.

79 In explaining its reasons, the BoI highlighted that in performing their functions the inspectors were public officers, with all the criminal law consequences that breaching the secret in their position would imply.

80 The BoI was very cautious in making it clear that inspections did not have any tax purposes, requiring nominal lists for credit exposure, but avoiding to ask lists of depositors. E.g. instructions for inspections in Genova, ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 556, f. 1 22–27th February 1933.

81 See for example the case of Unione Bancaria Nazionale (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 6707, f. 1; ASBI, Sconti, prat. 197, f. 1.); Credito Meridionale di Napoli (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 8144, f. 1.); Banca Agricola Commerciale di Moncalvo (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 7261, f. 1.); Banca di Pordenone (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 8139, f. 1.); Banca Mutua Popolare di Rovereto (ASBI, Vigilanza, prat. 7093, f. 1.). For a further discussion on the BoI’s synergies between lender of last resort and supervision function see Molteni and Pellegrino (Citation2021).