Abstract

This paper advances our understanding of how organisations engage in the process of Bourdieusian capital conversion during crises of socio-political legitimacy. We do so by analysing the arts sponsorship strategies of Barclays between 1972 and 1987. During this period, Barclays faced numerous challenges to its organisational legitimacy as a result of its continued dealings in apartheid South Africa and its ability to generate extraordinary profits despite general economic malaise in Britain. As a response, Barclays increased its sponsorship of the arts, exchanging its substantial economic capital for the symbolic capital associated with high-status arts institutions. We identify the forces that facilitated and inhibited these capital exchanges and how they affected Barclays’ sponsorship strategies. This paper will be of interest to Bourdieusian scholars interested in capital exchange, to business historians interested in banking in Britain during the 1970s and 1980s, and researchers interested in the evolution of corporate sponsorship and philanthropy.

1. Introduction

By the second half of the twentieth century, Barclays had become both a leading high-street bank serving British depositors and a multinational financial institution. The bank experienced a crisis of socio-political legitimacy that began in the early 1970s, when it was attacked in Britain for its decision to continue doing business in white-ruled South Africa. These attacks on the bank intensified after the Soweto Massacre in 1976 and persisted until the bank’s divesture from South Africa in 1987. Concurrently, Britain’s banking industry as a whole came under sustained attack from elements of the press and the Labour Party due to the high profits of the sector during a time of economic difficulty for much of the country (Ackrill & Hannah, Citation2001). One part of the firm’s response to these interlocking legitimacy crises was the conversion of economic capital into symbolic capital via its sponsorships of prestigious arts organisations. Prior to its crisis of legitimacy in the 1970s, Barclays did not sponsor arts organisations. By the 1980s, it had become a leading corporate sponsor of high art, channelling money into such prestigious arts organisations as the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal Opera House. We argue that managers’ decisions to trade the bank’s economic capital for symbolic capital through these exchanges were driven by the strategic imperative to preserve the bank’s legitimacy in the eyes of its core stakeholders. We also show that these Bourdieusian capital conversions were variously facilitated and inhibited by the following factors: habitus and the field; law and government policy; the financial position of the firm’s potential exchange partners; the example of other organisations; and disputes within the firm’s potential exchange partners. Our paper contributes to Bourdieusian management theory by introducing these key factors that were previously unknown to the existing literature in management on Bourdieusian capital conversion,

Bourdieusian theory (Bourdieu, [Citation1984] 2010, [Citation1990] 2011, Citation1986), which distinguishes between economic, symbolic, and other forms of capital, examines the processes by which wealthy legitimacy-seekers convert economic capital into symbolic capital via exchange (Harvey et al., Citation2020; Vershinina & Rodgers, Citation2020; Wong & McGovern, Citation2020). As a study in the Historical Organisation Studies (HOS) tradition (Maclean et al., Citation2021), this paper seeks to contribute to both organisation studies and to the field of business history in a fashion that is characterised by what Maclean et al. (Citation2016) call ‘dual integrity’. Dual integrity typifies studies that would be respected by researchers in both organisation studies and by business history.

The present study responds to Maclean et al.’s (Citation2017) call for the use of Bourdieusian social theory in business history research. Within the Bourdieusian framework, capital is embodied in different forms, including economic, social, cultural and symbolic capital. An individual or organisation can accumulate vast stores of one form of capital whilst having limited access to another (Adler & Kwon, Citation2002; Anderson & Jack, Citation2002; Anderson & Miller, Citation2003; Baron & Markman, Citation2003; Harvey et al., Citation2011). In organisation studies, Bourdieusian theory has been applied to demonstrate how actors exchange and convert different forms of capital. Our historical study explores one organisation that engaged in strategic capital conversions designed to preserve its socio-political legitimacy with numerous prestigious but cash-strapped organisations who required economic capital. We examine how Barclays’ efforts to engage in such transactions were sometimes frustrated by its habitus and the habitus of its potential exchange partners. This study will, therefore, shed fresh light on the key factors that facilitate and inhibit the process of Bourdieusian capital conversion.

For business historians (Wilson et al., Citation2022), how and why Barclays began developing strategies around funding for the arts is important because it illuminates important themes in British and international business history. Our research sheds light on the strategy and decision-making inside a multinational enterprise at a time when the relative merits of socialism and private enterprise were being energetically debated in the political sphere. Our research also speaks to discussions on the evolution of twentieth-century British banking by exploring cultural factors (Arch, Citation2021; Barnes & Newton, Citation2022; Billings et al., Citation2021; Decker, Citation2008; Wilson et al., Citation2018). Our study also contributes to international business history as we discuss how one corporation responded to the global anti-apartheid movement and because the beginning of arts sponsorship by Barclays coincided with a broader shift in corporate philanthropy that occurred throughout the English-speaking world in the 1970s (Phillips & Whannel, 2013; Schiller, Citation1991). As this study demonstrates, it was in this decade that public corporations on both sides of the Atlantic first began to fund arts and artists, an activity that firm directors had previously regarded as a function best left to other actors.

This paper is structured as follows: the literature review will analyse the literature on Bourdieusian capital theory, capital exchange and conversions and organisational legitimacy. Following this will be a section that discusses our approach to methodology including data sources and data analysis methods. We present our findings in the form of a comprehensive case study and a detailed analytical narrative. Following this will be the discussion section which examines the key inhibitors and facilitators that prevented, limited, and enhanced Barclays’ capital exchanges. Finally, we conclude by evidencing the dual integrity of our study and presenting the implications of our research for both organisation studies scholars and business historians.

2. Theoretical framework

2.1. Bourdieusian capital theory

Bourdieusian capital theory and the processes of capital accumulation, exchange and conversion have received increasing attention in management and organisation studies in recent decades (Harvey et al., Citation2011; Harvey & Maclean, Citation2008; Pret et al., Citation2016; Wong & McGovern, Citation2020). These processes are our central focus in this paper. Within the Bourdieusian framework, individuals compete for different types of capital in order to gain and maintain positions within a given institutional field. In this study, ‘Banking’ and ‘the Arts’ are examples of institutional fields. Each institutional field is characterised by its own distinctive pattern of capital combination and recombination. According to Bourdieu (Citation1986, p. 242), capital has four main forms: economic, social, cultural, and symbolic. Economic capital denotes any material assets that are immediately convertible into money. Economic capital thus denotes money, real property, and other assets that can be bought and sold. Social capital, in contrast, is highly intangible and consists of group members and social networks. Cultural capital is directly linked to the arts, culture, and education (Maclean et al., Citation2006).

Cultural capital has three sub-categories: the embodied state, which refers to knowledge, language, mannerisms, and behaviours which are acquired thorough socialisation; the objectified state which is related to possessions and consumption of books, paintings, musical instruments, and general goods connected to high culture; and the institutionalised state which refers to certification and formal qualifications. Symbolic capital denotes assets that increase one’s prestige and standing in the community. As Harvey et al. (Citation2011, pp. 431–432) observe, donations to charity frequently involve trading economic capital for symbolic capital and while ‘[t]he economic capital invested philanthropically by definition yields’ returns to the donor ‘in the form of cultural, social and symbolic capital, which in turn might yield an economic return’ in the future.

Bourdieu’s primary focus was on the capital held by individuals rather than organisations. However, Bourdieu and Haacke (Citation1995, pp. 17–18) do discuss capital conversions by organisations, in particular through their sponsorship of the arts. For Haacke, the primary reason for such exchanges is to ‘create a favourable political climate for their interests’ with the strategic goal to ‘neutralise critics’, while also having the added benefit of allowing an organisation to master the art world’s jargon and be able to ‘construct a cultural façade’ (Bourdieu & Haacke, Citation1995, p. 18, 36). Bourdieu conceptualises this process through the metaphor of a bank account. Through donations and sponsorships, an organisation can accrue symbolic capital that can be used to bolster its image, often measured monetarily through the category of ‘good will’, and can ‘bring indirect profits and permit it, for example, to conceal certain kinds of actions’ (Bourdieu & Haacke, Citation1995, p. 18).

Goodwill is an intangible asset of a company, which considers the value of things such as a company’s brand, its customer relations, and its relations with its employees. The perceived value of a company’s brand and branding activities increased dramatically during the twentieth century, with the 1970s and 1980s seeing the rise of corporate identity consultancies as the value of a brand both internally and externally was recognised and even factored into the value of a company during an acquisition. In part, the attempts to monetarily measure the value of a brand were due to it being increasingly perceived as a ‘wealth generator’, an intangible asset whose value did not decrease, and could even increase, with use (Moor, Citation2007, pp. 32–34). Branding was no longer about projecting an image of an organisation that existed within a given national community, but instead was about ‘constituting the corporation as a specific community, endowed with its own particular values’. Through these efforts, the organisation could encourage the ‘employees [to] produce the identity of the organisation, and at the same time produce themselves as members of the organisation’ (Arvidsson, Citation2006, p. 85). By building a brand with significant symbolic capital, organisations are able to use the brand to create new products that inherit some of the symbolic capital from the brand that it is associated with, allowing organisations to transform accrued symbolic capital into economic capital (Khelfaoui & Gingras, Citation2020).

An organisation’s brand can be seen as the embodiment of ‘ongoing relationship between customers and businesses’ (Batchelor, Citation1998, p. 97) and includes a degree of humanisation (Upshaw, Citation1995, p. 13) and actions that construct an organisation’s brand (Gobe, Citation2009). There are various approaches an organisation can use to humanise the brand and present a personality or image that promotes the organisation without focussing on its products. One approach is to use employees as representatives of the brand (Harris & de Chernatony, Citation2001) with Barnes and Newton (Citation2022) showing how banks used uniformed female staff to reshape the bank’s brand into something more approachable and popular with customers. Historical figures and events can also be used to create an emotional connection with customers (Miranda & Ruiz-Moreno, Citation2022). Another approach can be seen in the branding practices of Shell, whose sponsorship of modern art depicting the British countryside allowed it to associate itself with important public figures such as T. S. Eliot as well as giving the company a distinct identity which ‘fostered strong associations of the corporate brand in the popular mind with taste, nature, authenticity, and Britain’ (Heller, Citation2010, p. 208). Through engaging in the image of cultural production, sponsoring cultural events, and ensuring they are seen to have been instrumental in the production of the event through the use of the corporation’s name, VIP seating, exclusive events, and special access to performers (Rectanus, Citation2002, p. 142), organisations can embue a brand with cultural capital. Organisations are able to embody cultural capital in the embodied state through the constructed personality of the brand while also exploiting the embodied and institutional cultural capital of its employees that both build and represent the brand.

Bourdieu argued that the conversion of one form of capital to another involves costs that vary according to the degree of difference in the habitus or modes of thought that are dominant in the relevant field. When these differences are too great, the costs of exchange may reach the point at which the exchange becomes unviable. Numerous studies that have applied Bourdieusian theory have found that whether or not capital conversion will be inhibited depends largely on the local context but also on the habitus, status, and position within the field of play of the organisations involved in the capital exchange. For instance, researchers have found that there are substantial inhibitors of capital conversion in the Indian handloom industry (Bhagavatula et al., Citation2010), while a study of craft entrepreneurs in the UK (Pret et al., Citation2016, p. 1005) found that ‘almost no evidence of the inhibitors of capital conversions proposed in the extant literature’ prevented capital conversion by the participants in their study. Drakopoulou-Dodd et al. (Citation2014) found that in some contexts it is easier to transform cultural capital into social capital than vice versa. In a study of European migrants in Britain, Vershinina and Rogers (Citation2020, p. 593) explored how capital conversions can be impeded by context, education and transferable value, ‘the ability to convert forms of capital is limited by the field, an individual’s education and background, their social position and connections’. In a recent HOS paper informed by Bourdieusian theory, Wong and McGovern (Citation2020) demonstrated that possession of social capital makes is easier for cultural entrepreneurs ‘to convert cultural capital in the form of music, concerts, education and instruments into symbolic and economic capital’ (Wong & McGovern, Citation2020, p. 5). To date, however, no studies have investigated how capital conversion is inhibited and facilitated during crises of socio-political legitimacy. Our empirical study takes place against the backdrop of such a crisis.

2.2. Organisational legitimacy

Suchman (Citation1995, p. 574) defines legitimacy as ‘a generalised perception or assumption that the actions of an entity are desirable, proper, or appropriate within some socially constructed system of norms, values, beliefs, and definitions’. Organisational legitimacy denotes congruence between the actions of an organisation and ‘social values’ and ‘norms of acceptable behaviour in the larger social system’ (Dowling & Pfeffer, Citation1975, p. 122). An organisation’s socio-political legitimacy, in contrast, relates to the degree to which an organisation is viewed by evaluators as morally right and operating in accordance with the prevailing social norms and laws (Suchman, Citation1995). Organisational legitimacy is, therefore, fundamentally about stakeholders’ views of what is ‘appropriate and right, given existing norms and laws’ (Aldrich & Fiol, Citation1994, p. 648). Suchman (Citation1995, p. 597) indicates that crises of organisational legitimacy usually begin suddenly and ‘befall managers who have become enmeshed in their own legitimating myths and have failed to notice a decline in cultural support, until some cognitively salient trip wire (such as a resource interruption) sets off alarms’. He notes that ‘legitimation crises tend to become self-reinforcing feedback loops, as social networks recoil to avoid guilt by association’ with the organisation.

Recently, Finch et al. (Citation2015), examined socio political legitimacy by exploring how Canadian stakeholders made moral evaluations about a controversial oil sands project. Similarly, Haack and Sieweke (Citation2018) examined how German individuals evaluate the moral legitimacy of economic inequality. Baumann-Pauly et al. (Citation2016) applied the ideas of the philosopher Jürgen Habermas (Citation1975) in understanding how Puma, an international clothing company, maintained its socio-political legitimacy in the face of rising concerns about the environment and the rights of garment workers in developing countries. While these studies have improved our understanding of how managers respond to a crisis of legitimacy, they give us a limited understanding of how strategies of capital conversion can be used by managers as a tool in such crises.

2.3. Bourdieusian theory and legitimacy

In our view, Bourdieusian capital theory is ideally suited to understanding how exchanges are made with a view to increasing organisational legitimacy during crises of socio-politcal legtimacy, as the theory was originally developed by Bourdieu with the express goal of explaining how different individuals and organisations within a given nation’s elite (in his case, France after the disorder of 1968) make the mutually beneficial exchanges that have the net effect of upholding the existing social order. Harvey et al. (Citation2020) use Bourdieusian theory to examine how elites form coalitions with the aim of enhancing legitimacy via the exchange of economic and symbolic capital. In their study of the evolution of elite philanthropy in an English region, Harvey et al. (Citation2020, p. 3) conclude that successful exchange of capital is contingent on the ‘mastery of the processes of capital conversion and accumulation’ (Harvey et al., Citation2020, p. 3). Mastering these processes, they reveal, is an art acquired through trial and error. This paper builds on the study by Harvey et al. (Citation2020), by developing our understanding of how and why Bourdieusian capital conversions occur during such crises of organisational legitimacy as opposed to during normal periods.

3. Methodology and data

3.1. Data collection

We used an abductive approach that involves making inferences about causation that are informed by both the researchers’ knowledge of existing theory and the observations that emerge from reviewing original data (Hansen, Citation2008; Kay & King, Citation2020; Saetre & Van de Ven, Citation2021). To abductively develop our understanding of the processes by which managers in organisations experiencing a crisis of socio-political legitimacy convert economic capital into symbolic capital, we examined manager-created documents stored at the Barclays Group Archive (BGA). Utilising our pre-existing contacts, we negotiated access to this corporate archive, explaining to the staff of the archive the nature of our research question. We visited BGA in October 2019 for four days, identifying archival materials relevant to our research question prior to visiting. These materials included internal, inbound, and outbound correspondence, board of directors’ minutes, and the records of the Sponsorship Committee, the group of Barclays managers who made decisions about which arts organisations to sponsor. During our visit in 2019, we photographed 643 pages of archived documents which included 411 different documents; all the photographs were uploaded to a shared online folder so that all co-authors could participate in the data analysis. In addition, we examined numerous company-produced publications, handbooks, catalogues, and newsletters. We supplemented this dataset of Barclays archival data with information from other contemporaneous sources including historical newspaper articles and UK government publications.

3.2. Data analysis

Our analysis of the primary sources was informed by the methodology papers by Kipping et al. (Citation2014) and Lipartito (Citation2014). We analysed each document using a technique called source criticism. This process requires the researcher to ask questions about each document that relates to the document’s authorship, age, and the motives of the individual who created each document (Howell & Prevenier, Citation2001). The majority of the primary sources we examined were created by Barclays managers, specifically by those who were part of the Sponsorship Committee or Group Public Relations Department (GPRD). While the authors of these documents were remarkably frank about the reasons they choose to sponsor, or not sponsor, a given activity, person, or organisation, they rarely included any statements that represent an attempt to understand the thinking of the decision-makers in the partner organisations on the other side of these exchange transactions. However, we were able to learn about the decision-making processes of these partner organisations by looking at other documents, such as letters from external organisations preserved in the bank’s archive, documents in other archives such as that of the Anti-Apartheid Movement, and contemporary newspapers. Reading these documents allowed us to better understand the motivations of Barclays’ sponsorship partners.

Our analysis of each primary source was informed by our belief that it is often useful to conceptualise organisations as coalitions of individuals. While this approach to archival document analysis might strike some readers as excessively similar to the methodological individualism associated with the rational-actor model, we believe that this way of conceptualising organisations is eminently compatible with Bourdieusian theory. As Bouvier (Citation2011) notes, Bourdieu was attempting to stake a middle ground position between the strong version of methodological individualism position articulated by many economists and methodological holism. The problem with methodological holism is that it can cause researchers to overlook the diversity of individual motives within organisations. What that means in practice is that a researcher who is using primary sources in an archive to investigate how an organisation is responding to changes in its environment must remember that the individual document creators whose words they are reading had their own agendas, ambitions, or goals that may or may not have been congruent with that of the organisation as a whole. In analysing a given document, for example, a piece of internal correspondence between two Barclays executives, we reminded ourselves that the individual who wrote that document likely had goals that were distinct from that of his or her employing organisation. Our analysis of the documents in the corporate archive allowed us to engage in pattern recognition and analyse the sponsorship activities of Barclays through a Bourdieusian framework. In reporting what we have learnt from our research in Sec. 4, we have used the analytic narrative approach, a method of sharing findings that helps both researchers and readers to think about sequence and causation (Bates et al., Citation1998; Bucheli et al., Citation2010; Gill et al., Citation2018).

4. Analytic narrative

4.1. Barclays, South Africa, and the Anti-Apartheid Movement

In the early twentieth century, Barclays expanded from the UK and established banking subsidiaries throughout the British Empire, including South Africa in 1925 as part of Barclays’ Chairman F. C. Goodenough’s strategy to turn Barclays into an international bank (Channon, Citation1988, p. 1; Jones, Citation1993, pp. 148–151). The Anti-Apartheid Movement (AAM), a London-based pressure group, was established in 1959 to coordinate consumer boycotts and other measures designed to harm the South African regime. In 1970 the AAM turned its attention to Barclays due to its involvement in funding the building of the Carbora Basa Dam, a high-profile project in the Portuguese colony of Mozambique (Haslemere Group & AAM, Citation1970). Although Barclays ended its involvement in this controversial project in 1971, the AAM increased its pressure on Barclays to divest from white-ruled southern Africa completely. It called on the Labour government, in office in Britain from 1974 to 1979, to force all British banks to withdraw from the Republic of South Africa if they would not do it voluntarily (AAM and Haslemere Group, Citation1975; AAM End Loans to Southern Africa & Haslemere Group, Citation1978). In 1977, the chairman of the Midland Bank, a key competitor of Barclays, announced that they would be restricting future loans to South Africa to identifiable trade only (John, Citation2000).

The question of whether Barclays the banks took the threat of nationalisation seriously should divest from apartheid South Africa was first raised at an annual general meeting (AGM) of the company in 1972, when Chairman Sir Anthony Favill Tuke declared that the bank’s involvement in South Africa was beneficial to the country’s Black majority (Barclays Bank International, Citation1972). The issue of apartheid resulted in newsworthy protests at Barclays AGMs in 1973, 1975, 1976, 1977, and 1979 (By a Staff Reporter, Citation1976; Geddes, Citation1975; Gleeson, Citation1977; The Guardian, Citation1979). At these AGMs, activists who had acquired share certificates for the purposes of attending the AGM vigorously dissented from the policy of the board. In 1973, protesting shareholders had to be physically removed from the AGM by ‘heavier members of the bank’s staff’ (The Guardian, Citation1973). Further pressure on Barclays to divest from South Africa came in March 1978 when the Nigerian Government withdrew its funds from Barclays, citing the bank’s purchase of $14 million of South African defence bonds (Ottaway, Citation1978; Pullen, Citation1978). The board of Barclays Bank International (BBI) first debated whether to exit South Africa in 1977, the year that saw South African troops invade Angola and Mozambique and the murder of Steven Biko, a famous anti-apartheid activist, by South African state security officers (Ackrill & Hannah, Citation2001, p. 295). Following the review, Barclays announced that while it would continue to do business in South Africa, it would begin to publicly criticise apartheid and aimed to set an example of how engagement in South Africa could produce reform from within (Morris, Citation1982).

Protests against Barclays’ decision to operate in South Africa escalated in the 1980s. A team that included the actress Julie Christie and the MP Neil Kinnock established a ‘Barclays Shadow Board’ (BSB) in 1981 (End Loans to Southern Africa, Citation1981). The BSB published a report each year until 1986 that coincided with the publication of Barclays annual reports by the firm’s board of directors. Instead of reporting profits and losses, the shadow board’s annual report to the shareholders focussed on Barclays’ activities in South Africa. Boycotts of Barclays led to the loss of yet more accounts (Mughal, Citation1982), with Lambeth Council’s decision to withdraw its account depriving the bank of an account with an annual turnover of £1.2bn, its tenth largest British account (End Loans to Southern Africa, Citation1981). Younger people were particularly hostile to the bank and the proportion of students who banked with Barclays fell from 30 per cent in the 1960s, to as low as 17 per cent in 1985. Indeed, at some universities, not having a Barclays account was essential to fitting in (Burkett, Citation2018). On a single day in 1985, 125 of the bank’s branches were attacked, resulting in broken windows, spray-painted premises and even assaults on staff (Ackrill & Hannah, Citation2001, p. 297).

In 1985, Barclays reduced its stake in South Africa by declining a rights issue, surprising media commentators as just two weeks previously the firm’s Chairman had declared that ‘we certainly don’t propose at the moment to reduce our stake’, in the South African subsidiary (Fleet, Citation1985; Kennedy & Wilson-Smith, Citation1985). In 1986, Barclays at long last announced it was pulling out of South Africa. The board justified this decision on commercial grounds, citing poor economic conditions in South Africa and greater regulatory burdens in both the UK and South Africa (Ackrill and Hannah, Citation2001, pp. 298–300). However, The Times speculated that the decision was ‘motivated almost entirely by political reasons’ (Hornsby, Citation1986). Barclay’s sale of the South African subsidiary produced £80 million and thus represented a major loss, as the value of their stake in the subsidiary had been credibly estimated at £330 million in 1983 by Barclays, while a journalist at The Times estimated that the sale represented a book loss of £42 million (Thomson, Citation1986; Webster & Thomson, Citation1986). Additionally, the announcement also led to a backlash from Conservative MPs, with Teddy Taylor describing it as an ‘appalling act of moral and commercial cowardice’, while his colleague Anthony Beaumont-Dark opined that Barclays had ‘allowed itself to be blackmailed by bullies’ (Webster & Thomson, Citation1986). Another observer, the leader of the centrist Social Democratic Party, attributed Barclays’ decision to a set of factors that included the student boycott (Webster & Thomson, Citation1986; Woods, Citation1986).

4.2. British banking profits in the 1970s

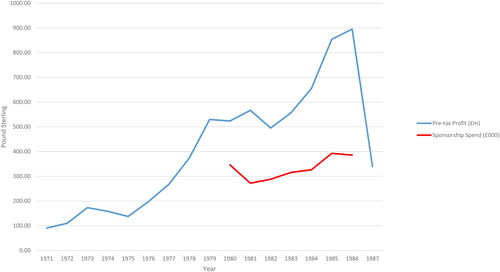

Barclays’ presence in South Africa was not the only public relations challenge the firm faced in the 1970s and the 1980s. Members on the left of the Labour Party demanded the nationalisation of the clearing banks (Reveley & Singleton, Citation2014) and there were frequent references in the press and in parliament to the unfair high profits these banks earned at a time when the UK economy as a whole was experiencing stagflation, an energy crisis, and a humiliating conditional bailout from the IMF (Eisenstein, Citation1980; Tuke, Citation1980a). The profits of Barclays increased markedly after 1973, even as the country was suffering (see ). Indeed, reports of ‘embarrassing[ly high] bank profits’ (Mansell, Citation1973, p. 13) caused outrage in sections of the press, particularly as they were seen as undeserved and seen as ‘simply a windfall, a wholly uncovenanted bonanza’ as ‘they could hardly help making enormous profits last year’ (Opie, Citation1974, p. 12). The high profits enjoyed by Barclays and other clearing banks led to the National Union of Bank Employees to call for profit sharing with employees; Stoddart, Citation1976). In 1976, the Labour Party National Executive Committee set out plans to nationalise the banks (The Guardian, Citation1976). Although the parliamentary Labour party was not committed to the nationalisation of the banks (Lever, Citation1976, col. 1470), the banks took the threat of nationalisation seriously (‘The Guardian’, Citation1977; Gordon Tether, Citation1977).

Table 2. Barclays’ profits before tax, 1972–1987 (£millions) (Barclays, 1974–Citation1987).

Table 1. Barclays’ sponsorship spending 1980–1986 (£000 s) (Barclays, Citation1981b; Citation1984a, Barclays, Citation1987; Moon, Citation1981).

4.3. Corporate sponsorship of the Arts

It was in this fraught political context that Barclays embarked on a novel strategy of sponsoring cultural and artistic organisations. For banks, tobacco companies, and other stigmatised firms, arts sponsorship offered the opportunity to gain (and regain) legitimacy. Another contextual factor that explains why Barclays began sponsoring the arts in the mid-1970s was that other large corporations in common-law jurisdictions were simultaneously moving into arts sponsorship. In supporting the arts and other charities, companies were violating the previously widespread norms that frowned upon corporate donations to charity. This norm, which has informed case law in both England and the United States, appears to have inhibited company directors in the 1970s and 1980s who were deciding whether or not to donate shareholders’ money to charities. As we shall see, Barclays’ managers were uncertain whether giving shareholders’ money to arts or other charities was truly consistent with the spirit of the law.

To understand why these managers were reluctant to give money to charities, it should be remembered that Victorian judges with a strong commitment to the doctrine of shareholder primacy had allowed shareholders to sue directors who were philanthropic with the shareholders’ money, as in the celebrated case of Hutton v West Cork Railway Co. of 1883. The law was interpreted as meaning that managers could donate shareholders’ money to charities when doing so could be demonstrated to be highly likely to produce a tangible improvement of the bottom line of the firm (Moore, Citation2018). If executives of a company departed from this principle and were excessively charitable, they risked being the subject of a lawsuit by shareholders similar to the 1921 case in which a shareholder sued a chemical company that had donated £100,000 to support chemistry education in British universities (Baxter, Citation1970). Starting in the 1940s, some American states had amended their company laws to permit corporate philanthropy, but the legality and ethicality of such donations remained contested for several decades longer in many common-law jurisdictions (Balotti & Hanks, Citation1998).

A 1962 report into UK company law observed that the attitude to the courts towards corporate philanthropy had softened since 1883. The report observed that financial transfers from companies to charities would likely ‘be acceptable to the Courts today’ provided the donation in question was ‘necessary to create or preserve goodwill’ for the firm and would benefit shareholders in the long-term (Report of the Company Law Committee, Citation1962, para. 52). As late as 1987, however, a British management academic, declared that ‘the absence of recent cases concerning the validity of company charitable donations means that the law is still unclear’ (Cowton, Citation1987, p. 554). We can thus conclude that in the period when Barclays executive began to consider whether to donate shareholders’ money to arts charities, they were operating in an environment in which it had only recently become clear whether they were allowed to donate to any charity, artistic or otherwise.

In the United States, another country in which corporate philanthropy had long been a legal and ethical grey area, the idea that business corporations should sponsor the arts was promoted by the Business Committee of the Arts (BCA) in New York. This organisation was established in 1967 by David Rockefeller, then chairman of Chase Manhattan Bank, in an effort to change the thinking of decision-makers in firms. While wealthy individuals who were also shareholders of firms had long given to the arts from their personal funds, the BCA promoted a new model of arts philanthropy in which companies would give to arts charities on behalf of their shareholders (Rockefeller, Citation1972). This novel practice, which emerged in New York in the 1960s, transferred to corporate managers the power to decide which types of arts would be supported. The practice of business corporations sponsoring the arts rather than leaving this activity to the government or to wealthy individuals spread from the United States to other English-speaking countries in the 1970s. In 1974, the Council for Business and the Arts in Canada (CBAC) was established to encourage firms in that country to begin sponsoring the arts (Canada Council, Citation1974), thereby emulating the model pioneered by Chase Manhattan Bank. In 1975, the UK’s Minister of the Arts, Hugh Jenkins told a parliamentary committee that British companies should do more arts funding so as to relieve the pressure on ‘the Exchequer’ (Gosling, Citation1975; Philips & Whannel, Citation2013).

In 1976, the Association for Business Sponsorship of the Arts (ABSA), an organisation with a mandate similar to the BCA in the US and the CBAC in Canada, was established in London. In 1981, ABSA published the findings of a study by McKinsey Consulting that had revealed that ‘sponsorship of arts by business has attracted a great deal of interest in recent years’ (ABSA, Citation1981, p. 3). In 1978, The Sunday Times reported that British companies had recently started giving money to support the arts (Harland & Henderson, Citation1978). Two years later, The Sunday Telegraph reported that ‘Big Business is starting to put money into the arts through sponsorship’ (Dalvey, Citation1980, p. 27). We note here that the practice of corporate arts sponsorship appears to have diffused to mainland Europe in the 1980s: other researchers have reported that Swedish companies began sponsoring the arts in the 1980s (Gianneschi & Broberg, Citation2020; Lund & Greyser, Citation2020).

In 1975/76 corporate spending on sponsorship of the arts by member companies of ABSA was £600,000 (Higgins, Citation1980). The equivalent figure for 1985 was estimated as £25 million (Douglas, Citation1985). Likewise, the number of ABSA patrons and members increased from 16 and 84 respectively in 1980 to 28 and 98 in 1983/84 (Myerscough, Citation1986, p. 59). Corporate sponsorship of the arts saw similar growth in Scotland, with spending nearly trebling from £313,000 to £907,000 between 1979/80 and 1982/83 before falling slightly to £837,000 in 1983/84 (Myerscough, Citation1986, p. 60). The majority of the spending in Scotland in 1983/94, £674,000 was given to ‘National Companies’ which included the Scottish Opera and Scottish Ballet among others, and festivals. Over half of the remaining amount, £127,000, was split between drama companies and ‘other music and dance companies’. The industries responsible for the majority of spending on corporate sponsorship also appear to have diversified in Scotland over this period. While banking, oil companies, and insurance firms featured as the three biggest spenders between 1979 and 1983, by 1983/84 the yearly increase in spending by ‘miscellaneous’ companies had reached £271,000, the single largest spend being only £47,000 behind the combined spending of the banking industry (£168,000) and oil companies (£150,000).

Corporate support became more important to arts organisations following the 1979 election and the subsequent cuts in state funding for the arts. Under Margaret Thatcher’s leadership, arts organisations became even more eager to obtain corporate sponsorship than they had been under Labour, particularly as they as they had grounds for believing they might soon lose all taxpayer support. Following Thatcher’s selection as Conservative leader in 1975, a faction within the party came to support the total abolition of state funding of arts. This course of action was advocated in reports published by centre-right think-tanks (Alexander, Citation1978; Brough, Citation1977). The arts policy of the more radical wing of the Conservative Party was simple: cut taxes and allow individuals to support the arts if they so choose. While this policy was never actually implemented, state support for arts organisations fell in real terms in the 1980s, making those organisations much more eager for corporate sponsorship than would otherwise have been the case (Phillips & Whannel, 2013). Immediately after the 1979 election, the Conservatives signalled what their approach to the arts would be by cutting the arts grant by £1¼ million. As an opposition member observed, the nominal increase in arts funding provided for the 1980 budget actually represented a further cut in light of the 20 per cent inflation rate affecting the arts sector (Short, Citation1980).

The modest subsequent annual increases in government funding for the arts provoked indignation from the advocates of more generous arts funding in the Labour Party and complaints from the more right-wing Conservative MPs that government funding of any sort was continuing. Over the course of the 1980s, state support for the arts increased, but slower than inflation (Dempsey, Citation2016). In a 1985 debate about arts funding, Conservative MP Francis Maude implied that the government’s funding of artists was far too generous when he observed that taxpayer support for the arts between 1985 and 1986 would be £272 million, an ‘increase of 18 per cent since the Government came to office’ in 1979. Maude explained that while he was ‘in favour of the arts’ he was ‘opposed to direct Government subsidy of the arts’, also remarking that ‘during the past 10 years there has been a rebirth of [private-sector] sponsorship of the arts’, praising British Petroleum’s support of ‘the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, which is not a particularly cautious or unadventurous project’ and the good work of ‘the Association for Business Sponsorship of the Arts’ (Maude, Citation1985, col. 298–300). Maude hoped that this salutary trend towards private support for the arts would continue as it is ‘only when we move away from’ from government funding of the arts that we will ‘witness a real regeneration in the arts in this country’.

Increased corporate sponsorship of the arts was not welcomed by all. Critics, such as Labour MP Tony Banks, were concerned that a shift in the source of funding would change the nature of the art produced, stating ‘I do not want our artistic tastes to be determined by the sums that Barclays Bank, Trusthouse Forte, Unilever or the wealthy put into the arts. I do not wish to see the corporate state emerging with big private companies becoming the arbiters of artistic taste’ (Banks, Citation1985, col 313). However, others in Labour were more concerned that the worst type of companies could use sponsoring the arts to increase their legitimacy. Alluding to the extensive arts sponsorship of Benson and Hedges, Labour’s shadow Minister for the Arts, Phillip Whitehead argued ‘I do believe tobacco kills people. I don’t think they ought to be able to buy respectability for things which ought not to be respectable’, and that ‘tobacco has made it to the top of the arts establishment, British music is now addicted to support from the cigarette men’ (Taylor, Citation1984). While sponsorship of the arts by the wealthy in Britain had not been uncommon (Harvey et al., Citation2011), sponsorship by wealthy corporations appears to have been viewed differently by these MPs.

4.4. Barclays sponsorship of the Arts

The surviving internal correspondence in the Barclays archive shows that the bank managers were aware that companies in the United States, particularly the leading national banks, had recently moved into arts sponsorship. For instance, in a discussion of how to sponsor the arts, Barclays Deputy Chairman Henry Lambert noted that he had shared ‘a rather good booklet which Citicorp produced about their charitable giving’ with the firm’s Chairman (Lambert, Citation1980). Records at BGA indicate that the bank first began sponsoring arts organisations in 1977. The unit of the bank responsible for deciding which arts organisations to sponsor was the Barclays GPRD which had been established in 1972. The GPRD was headed by a former journalist who joined Barclays from the information office of the Department of Trade and Industry (The Times, Citation1972; Goodenough & Treble, Citation1983). The core functions of the GPRD included offering the board advice on ‘broader issues arising from outside the United Kingdom’. It was also tasked with offering ‘substantial help’ at ‘Chairman level for the Annual General Meeting and at Local/Director [sic] level for dealing with universities’ upset about Barclays’ activities in Apartheid South Africa (Goodenough & Treble, Citation1983, p. 4).

Under the terms of the sponsorship agreements that Barclays instituted, the arts organisation would receive cash from the bank in return for acknowledgment of the financial support in their printed material and via prominent signage in their buildings. In many cases, the agreements also specified that Barclays would receive a number of free tickets for distribution to their employees and associates. For instance, the sponsorship agreement with the Royal Ballet’s overseas tour in 1985 permitted Barclays executives to attend a reception at the Royal Opera House (Quinton, Citation1985). The sponsorship deal also included Barclays branded travel gear for the crew and cast, which was important to the bank as the company was to tour Spain and Portugal, two markets into which the bank wished to expand (Cobben, Citation1985). The arts sponsorship arrangements negotiated between Barclays and the Royal Opera house bore all the hallmarks of classic Bourdieusian capital exchange, whereby the bank was able to exchange its economic capital for cultural and symbolic capital accumulated by virtue of the bank’s association and partnership with an elite cultural institution.

The evident focus of the bank’s arts sponsorship strategy after 1977 was on national arts institutions and cultural activities that fall into the category of ‘high art’. Prestigious art forms such as opera and elite theatre productions were selected for support. Starting in 1978, Barclays sponsored the D’Oly Carte Opera Company at the cost of £120,000 over three years (Barclays, Citation1981b). Likewise, Barclays agreed to sponsor a Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) production of Othello in 1979 (Connection, Citation2008, p. 36), the Royal Smithfield Show, and the Royal National Eisteddfod (McGregor, Citation1979). The early sponsorship strategies of Barclays demonstrated a clear focus on supporting cultural institutions and events of elite status with potential to accumulate vast stores of cultural and symbolic capital.

In 1980, the Minister of State for the Arts, Norman St John-Stevas, visited the bank’s headquarters to pressure it to increase its level of support for the arts (Eisenstein, Citation1980). In 1978, when the Conservatives were still in opposition, St John-Stevas had published a pamphlet in which he promised that a future Conservative government would work closely with private industry to increase funding to the arts, claiming that the ‘Tory Party continues to take a keen, active and committed interest in the future of the arts in Britain and that we make some claim to be the arts’ best friend’ (St John Stevas, Citation1978). Soon after becoming Minister, St John-Stevas approached the Committee of London Clearing Banks as well as the executives of the Big Four banks to encourage them to set up and reportedly contribute up to £500m to a foundation that would sponsor the arts (St John-Stevas, Citation1980).

Stevas’s visit to the bank to request that it dramatically increase its level of support for the arts sparked an internal debate about whether the firm’s directors were legally able to spend the shareholders’ money on donations to arts organisations and other charities. The internal correspondence we examined revealed that executives were uncertain whether extensive philanthropic activity on the scale envisioned by Stevas would fall outside the authority given to them as ‘the setting up of such a Foundation may be outside the authority of our Memorandum and Articles of Association’ (Johnson & J.G.F., Citation1980).Footnote1 Although the Barclays executives did not mention any of the historic lawsuits in which shareholders had successfully sued managers for being philanthropic with company funds, they appear to have felt that corporate philanthropy, or at least excessive corporate philanthropy, was a legal grey area, with it being ‘generally understood that a commercial company can only give away Stockholders’ money if the gifts are in a general sense in the interests of the company’ (Johnson & J. G. F., Citation1980, p. 3). The idea that being too charitable with the stockholders’ money would be illegal recurred in the discussions of how much the bank might properly give to arts organisation as executives debated how much more the bank should give. At one point, a £10 million trust for sponsoring the arts was discussed in the internal correspondence (Johnson & M.S., Citation1980, p. 3), a figure vastly larger than the amounts Barclays donated in subsequent years, which were typically between £300,000 and £400,000 (see ). There appear to have been significant disagreements within the bank about how far the company should go in responding Stevas’s call to arms.

In the internal exchange of correspondence related to the issue of the degree to which they were legally allowed to be charitable with the shareholders’ money, one Barclays manager wrote that while he felt certain that stockholders would accept them donating money providing ‘they gain goodwill or avoid illwill’ as a result, they had faced criticism in the past ‘where we have made gifts with political undertones’ (Johnson & J.G.F., Citation1980, p. 3). Other managers worried that engaging in more extensive corporate philanthropy than they had hitherto done would require changing Barclays’ governing document, something major shareholders would need to agree to at a General Meeting. These managers feared that the firm’s largest shareholders such as ‘pension funds might feel obligated to vote against such proposal’ even though they may support it on ‘moral grounds’ (Johnson & J.G.F., Citation1980, p. 4). Additionally, the firm’s Deputy Chairman pointed out that such a discussion of the firm’s philanthropic strategy at a General Meeting would be public, and that ‘the press could well make it controversial and with some reason’ (Weyer, Citation1980, p. 1). The same individual also expressed surprise that a government that espoused pro-business rhetoric was attempting to pressure firms into redistributing the shareholders’ money to artists, declaring that ‘it does not behove a Conservative Minister to complain if the private sector behaves properly to private-sector owners’ (Weyer, Citation1980, p. 1).

Despite the lack of clarity about whether extensive donations to charity would be consistent with the spirit of Barclays’ governing document, Barclays executives seem to have generally favoured at least some increased level of support for the arts, particularly when such support took the form of sponsorship agreements rather than no-string-attached donations. Readers will observe in that there was a shift after 1980 away from supporting the arts via donations to support via agreements that stipulated how the recipient organisation would acknowledge the firm’s support. The chairman of the board declared that ‘I am becoming more and more certain that we cannot just sit back and do nothing’ and that ‘shareholders must surely realise that some of the bank’s profits are coming from the community as a direct result of high interest rates, and there is a case for giving part of this back to the community’ (Tuke, Citation1980b). Indeed, many executives were in favour of increasing the company’s charitable donations, but noted that ‘we do spend quite a lot of money but do not get much benefit in public relations terms’ and that ‘one could only give money, which belonged to the stockholders, for social or cultural purposes if we were acting in their ultimate interest […] [i]f that is so, then we should make sure that people know what we are doing’ (Weyer, Citation1980, p. 1). On the 5 June 1980, the Barclays Board agreed to raise their current level of giving, particularly to the arts, providing that control remained with the board, hoping to ‘ensure that the Bank [sic] received appropriate recognition and goodwill for its donations’ (Barclays, Citation1980) ().

The bank quickly took steps to formalise its decision process and produce a clear sponsorship strategy. Decisions about which arts organisations Barclays would sponsor were, at first, made in ad-hoc fashion by the head of PR, his immediate colleagues, and Barclays’ Chairman. However, in 1981 Barclays established a Sponsorship Committee to oversee the group’s sponsorship policy and bring a more co-ordinated approach to its sponsorship. The systematisation of arts sponsorship strategy was needed to manage the increasing number of requests for sponsorship it was receiving from arts organisations. This committee initially comprised of three board members (the bank’s Deputy Chairman, Vice Chairman, and another Director), a Regional General Manager, the Head of Marketing, and the Head of Public Relations (Connection, Citation2008). The Sponsorship Committee oversaw the sponsorship budget and authorised all sponsorship agreements valued at over £10,000; the Committee Chairman and Head of GPRD could authorise, under their own authority, sponsorship agreements of up to £10,000 (Moon, Citation1985) while Local Head Offices could authorise sponsorships of up to £2,000 with Regional General Managers able to contribute a further £2,000 (Barclays, 1984). In 1983, the Sponsorship Committee formalised a targeted sponsorship policy that aimed to ‘support the Arts and activities involving young people’ (Goodenough & Treble, Citation1983, p. 6). Organisations sponsored by Barclays in that year included the Glyndebourne Touring Opera for £50,000, Opera North’s production of Madame Butterfly for £40,000, the Welsh Sculpture Trust for £75,000 as well as donations of £10,000 and £5,000 for the Royal College of Music (Barclays, 1984).

Barclays executives were clear that the bank’s sponsorship policy ‘is not the same as marketing activity’ as the ‘real benefits’ were ‘both tangible and intangible’. Indeed, ‘arts sponsorship in particular contributed to the public perception of the bank as an enlightened, reasonable, and community-minded organisations’. Furthermore, Barclays were clear as to who they were targeting, stating that ‘those who are conscious of arts activities expect support from an organisation the size of Barclays and include many of those likely to influence public opinion and Government policy’ (Barclays, Citation1985, p. 3). Indeed ‘the old principle of doing good by stealth is no longer appropriate, we need to be positive and definite in our giving, whilst properly seeking to identify benefits accruing to the bank’ (Barclays, Citation1984b p. 7). These excerpts demonstrate that Barclays were advancing formalised strategies of accumulating symbolic capital with the intention of accruing the tangible and intangible benefits to the bank’s identity.

4.5. The rejection of Barclays’ sponsorship

The bank’s efforts to acquire symbolic capital via payments to arts organisations suffered a series of blows in 1986, when the Commonwealth Institute rejected Barclays’ sponsorship of their Caribbean regional exhibit as part of its Caribbean Focus due to the bank’s activities in South Africa (Barclays, Citation1986b; Cobben, Citation1986a; Porter, Citation1985). However, arguably the most damaging blow in 1986 was when the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC), which has previously concluded a sponsorship agreement with Barclays, returned the bank’s money on the grounds that it could no longer accept funds from a firm with such extensive ties to apartheid South Africa. As mentioned above, Barclays had sponsored RSC projects before, such as Othello in 1979 and Richard III in 1980, and in February 1986 they agreed to sponsor a production of Macbeth staring Jonathan Pryce and Sinead Cusack at the cost of £50,000. The bank’s sponsorship agreement with the RSC specified that its name would appear on all publicity material, they would receive 50 seats on opening nights at Stratford and the Barbican, discounted tickets for staff, with some of the money also being used to provide educational workshops for schools that would also be credited to Barclays (Barclays, Citation1986b).

On 15 September 1986, Barclays’ managers learned the Pryce had declared that he would not take part in the play if it was sponsored by the bank. Initially, Barclays asked the RSC ‘to consider withdrawing the production—or changing their Macbeth [Pryce]’ but they declined; additionally, the RSC’s Artistic Director Sir Trevor Nunn spoke to Pryce in an ‘endeavour to dissuade him’ (Moon, Citation1986a). Two days later, the RSC confirmed that they would no longer accept sponsorship from Barclays due to objections from Pryce at Barclays’ involvement in the production (Brierley, Citation1986; Moon, Citation1986b). The decision of the RSC to return the money to Barclays was reported in The Times and The Guardian (The Guardian, Citation1986a; The Times, Citation1986). In an effort to place a positive spin on the debacle, Barclays issued a press release that observed that ‘1000 schoolchildren in the West Midlands … may now be deprived of the opportunity’ to see the play and asserted that ‘Barclays remains total opposed to apartheid’ (Barclays, Citation1986a; The Times, Citation1986), a statement that The Guardian dismissed as a ‘sob-story’ (The Guardian, Citation1986b). Indeed, this episode demonstrates that Barclays were facing a challenge to their legitimacy and identity as a result of their continued dealings in South Africa.

Following this experience, the bank rejected the offer to sponsor The National Theatre in December 1986 who planned to host a South African led production of Bopha!, a play that focussed on the role of black South African policewoman (National Theatre, Citation1986). Barclays turned down the proposal, stating that ‘our feeling was that more ill-will would be created with those companies who already see us as having caused them a problem by leaving South Africa than goodwill with the anti-apartheid people, who will simply think we are trying to buy favour’ (Quinton, Citation1986) and that it ‘would be seen as window-dressing by the anti-apartheid lobby’ (Cobben, Citation1986b).

5. Discussion: Facilitators and inhibitors of capital conversion

We now turn to a discussion of the various factors illustrated in our case study that facilitated and inhibited the conversion of economic capital into symbolic capital via the Barclays arts sponsorship programme. After examining our data, we were able to identify the main types of factors that either inhibited or facilitated capital conversion and which were, previously, undiscussed by Bourdieusian management theory.

5.1. Inhibitors

5.1.1. Law

In our analytic narrative above, we have seen that the shareholder primacy norm, closely associated with UK company law, inhibited capital conversion by limiting the amount of money the firm transferred to arts organisations. The Barclays managers who were tasked with deciding whether to transfer funds to arts organisations (and, if so, how much), referred frequently to their legal duties to the firm’s shareholders. The doctrine of shareholder primacy, which had earlier been promoted in a series of company law cases, appears to have been internalised by the managers. Their habitus made some decision-makers in the firm reluctant to exchange as much economic capital for symbolic capital as others within the bank had proposed. As noted above, managers within the bank favoured giving radically different amounts to arts organisation. Supporters of the view that the firm’s budget for arts philanthropy should remain modest ultimately prevailed, as the figures shown in indicate, and the grandiose plans to give £10 million per annum to arts charities never materialised. The existing literature in management on Bourdieusian capital conversion (e.g. Bhagavatula et al., Citation2010; Pret et al., Citation2016) ignores the issue of law and the role of legal norms in shaping habitus. Our research demonstrates how law can inhibit capital conversion in ways previously unidentified by Bourdieusian management theory.

5.1.2. Disputes within the receiving organisation

Our case study shows that disputes within potential partner organisations can be important inhibitors of capital conversion. Capital conversion always involved exchanges, either between individuals, which are relatively straightforward, or between organisations, which can be conceptualised as coalitions of individuals (Podnar et al., Citation2011; Whetten & Mackey, Citation2002). The episode in which internal opposition forced the management of the RSC to return money to Barclays illustrates how the process of Bourdieusian capital conversion between organisations is complex and can be subject to internal politics. While the senior management team of the RSC clearly wanted to accept sponsorship income from Barclays, and thus to exchange symbolic capital for much-needed economic capital, prominent individuals within this theatrical organisation were against that exchange due to their political views on external events. The high status within the RSC of one of these internal opponents of the proposed exchange—the lead actor—allowed them to pressure the management of the RSC into returning the money to the bank. This episode reminds us that the organisations that engage in capital conversion are not monolithic agents but have complex internal political disputes that are affected by internal and external events which can inhibit and impede the process of capital conversion.

5.2. Facilitators

5.2.1. Habitus and the field

This case study shows the importance of the habitus for facilitating the successful exchange of capital. The executives of Barclays, and leaders of the elite arts institutions that received sponsorship from Barclays, operated in different social fields, namely banking and the arts. However, both groups occupied comparable elite habitus within their respected fields, engaging in similar elite networks which promote the social norms, shared behaviours that provided the backdrop and foundations for successful exchanges of capital. While Barclays did also sponsor smaller arts organisations which were led by those outside of the elite, this funding was normally provided by local branches rather than at the organisational level. Hence, if organisational leaders occupy comparable habitus it can help to overcome differences in institutional fields and facilitate capital exchanges between organisations.

5.2.2. Government policy

Our case study demonstrates how government policy acted as a facilitator of capital exchange. From 1975 onwards, UK government ministers actively encouraged businesses to donate money to the arts. This encouragement explains why so many British firms suddenly started to donate to arts organisations in the 1970s, thereby abandoning the last vestiges of the old common-law doctrine that public corporations have no business donating money to charities. Existing research in management on Bourdieusian capital conversion is strangely silent on the whole question of the role of government as either a supporter or an impediment of capital conversion. This oversight is especially curious when one considers that the seminal works of Pierre Bourdieu on capital contained extensive references to the role of the state (Bourdieu, Citation1977, Citation1986). To borrow a phrase from the comparative political scientist Charles Tilly (Citation1985), Bourdieusian management scholars need to ‘bring the state back in’ to their analysis.

5.2.3. Examples of peer organisations

The sponsorship activities of other organisations, including rival banks, acted as a facilitator for Barclays when formulating their own arts sponsorship strategy. Internal correspondence in which Barclays executives discussed whether or not to donate to arts organisations, and how this should be implemented, made frequent reference to how other firms in the institutional field of banking, including the prestigious New York banks and their direct UK competitors, were now starting to fund arts organisations. Organisational theorists have long paid attention to institutional isomorphism (DiMaggio & Powell, Citation1983), particularly mimetic isomorphism, which is the tendency of organisations to imitate the behaviour of other organisations in the same field. As Wang (Citation2016) notes, Bourdieusian theory and the new institutionalist literature on institutional isomorphism are potentially complementary. Our research suggests that Bourdieusian management scholars who are interested in capital conversion should draw upon and contribute to, the literature on mimetic isomorphism more extensively than they have hitherto done.

5.2.4. Financial position of the firm’s potential exchange partners

The reduction in government support for the arts after 1979 made arts organisations increasingly receptive to the idea of accepting money from companies such as Barclays. As a result of the economic policies of the Thatcher government, which involved cutting public spending and creating a more pro-business environment, the disparity in the financial positions of Barclays and their potential exchange partner art organisations increased. The arts organisations that possessed the symbolic capital were even more desperate for economic capital than they had previously been. It is likely that had Britain been governed in the 1980s by a social-democratic government that had lavishly funded arts organisations, those arts organisations would have been far less willing to take money from Barclays. Financial desperation on the part of exchange partners that is induced by government policy can, therefore, be added to the list of known facilitators of capital conversion. A sudden change in the financial circumstances of one of the potential exchange partners would appear to influence and increase the probability of capital conversion taking place.

6. Conclusion: Implications of our findings for business history and Bourdieusian management theory

This study was focussed on examining the factors that facilitated and inhibited the exchange of economic for symbolic capital by Barclay. In the 1970s and 1980s, Barclays, which continued to enjoy record profits, faced a crisis of socio-political legitimacy. Funding for the arts was part of its response to this crisis and involved that bank embarking in a Bourdieusian capital exchange process by making strategic efforts to convert their economic capital for symbolic capital. In effect, Barclays and prominent, but cash-strapped, cultural institutions negotiated sponsorship agreements whereby economic capital was exchanged for symbolic capital. In some cases, the exchange transaction failed to materialise, such as in the episode when RSC returned the apartheid-tainted money to the bank. In other instances, the capital conversion process produced mutually beneficial outcomes for both the bank and partner institutions.

Our study builds on the extant Bourdieusian literature by identifying several inhibitors and facilitators of capital conversion including: law; government policy; intra-organisational politics; inter-field habitus; mimetic isomorphism; and the relative financial position of potential exchange partners. These had been largely ignored and were previously unknown to the literature in management on Bourdieusian capital conversion. We suggest that future research on capital conversion should use the experience of organisations in other legal systems and in different contexts to develop our knowledge of how law and government policy may constrain or enable capital conversion. As our findings demonstrate, in their internal debates about whether to give extensive funding to arts organisations, Barclay’s executives worried about whether they were legally allowed to give shareholders’ money away to artistic institutions in this fashion. This inhibitor was counteracted by government policy, namely the pressure from the government on Barclays and other banks to donate money to arts organisations. Somewhat paradoxically, government, the enforcer of the laws, was encouraging this organisation to behave in a fashion incompatible with a long-established a corporate law principle, shareholder primacy. We suggest that future research might be conducted in other organisational contexts whose capital conversion activities were simultaneously inhibited by the law and encouraged by government officials. Similarly, we think there is scope for more research on instances in which capital conversion is inhibited by disagreements within (and between) the organisations that would be involved in capital conversion transactions.

Our study also contributes to the HOS field, demonstrating dual integrity by contributing both to organisation studies and history. Our research findings have important implications for scholars in the field of business history, particularly those who do research on the history of corporate philanthropy and changing ideas about corporate purpose. As we noted above, British companies did not begin to donate extensively to arts organisations until the 1970s. Until this decade, charitable giving by British public corporations was strongly inhibited by the view that the sole purpose of a company is to maximise profits for shareholders. As we have observed above, the view that managers were legally and morally obliged to focus on maximising shareholders’ dividends had been upheld by the English and Americans courts in a series of high-profile decisions from 1883 onwards. In the 1970s, however, there was a shift in thinking about corporate purpose and large companies, starting first in the United States and then soon afterwards in the UK, began to make significant donations to charities, including arts charities. Given that academics and practitioners are now vigorously debating the relative merits of the shareholder primacy doctrine and the competing view that it is legitimate for the managers of companies to spend shareholders’ money on philanthropic, social, and environmental objectives (Stout, Citation2012), we would suggest that is important for business historians to do more research on both the rise of corporate philanthropy from the 1970s onwards and the earlier and subsequent historical processes by which the purposes of the business corporation had come to be narrowly defined as the maximisation of shareholders’ profits. Such research might, therefore, investigate why Victorian judges and businesspeople came to believe that the primary fiduciary duty of a director was to the shareholders, the emergence in the twentieth century of the corporatist view associated with Berle and Means, and the renaissance of the shareholder primacy doctrine that affected the decision-making of many Anglo-American managers in the 1980s and 1990s (Lazonick & O’Sullivan, Citation2000).

This study may inspire research on the advent of arts sponsorship by other firms in other countries and historical periods. Comparative research on the history of corporate arts sponsorship could contribute to the wider project of understanding the history of all types of corporate philanthropy. As we noted above, British companies did not begin to donate extensively to arts organisations until the 1970s. Until this decade, charitable giving by British public corporations was strongly inhibited by the view that the primary social obligation of company directors is to maximise profits for shareholders. We also note in the paper that the advent of corporate arts sponsorship in the UK followed similar changes in the United States: the 1960s, businesses headquartered in New York dramatically increased their arts sponsorship, doing so with the encouragement of the organisation founded by David Rockefeller. The primary sources we reviewed suggests that there was a transnational movement in business towards arts sponsorship in this period from the USA in the 1960s, to Britain in the 1970s, and then into Sweden in the 1980s. We believe that there is scope for additional research by business historians in different countries on the history of corporate art sponsorship. Comparative and transnational historical research on this subject would, in our view, allow us to better understand the consequences for business, and for artists, of corporate arts sponsorship. Business-historical research on other types of corporate philanthropy, such as donations to hospitals and air ambulance services, should also be conducted with a view to understanding why some firms preferred to donate to the arts, while others supported non-arts charities. Bourdieu’s insights on how legitimacy is gained through the acquisition of symbolic capital may help business historians to understand why firms in controversial sectors such as tobacco (Rumball, Citation2015) and opioids (Keefe, Citation2021) have been among the most enthusiastic sponsors of avant-garde arts.

Our paper also suggests that we need more business-historical research on evolving ideas about corporate purpose. Today, it is common to contrast two competing ways of thinking about the social purpose of the business corporation. One normative view, which is associated with the economist Milton Friedman and with common-law jurisdictions, argues that the primary social duty of the corporate executive is simply to maximise profits for shareholders so far as local laws and social norms allow. The other view, stakeholderism, which is associated with social democracy and with German corporate governance (Heath, Citation2011; Rahman, Citation2009), argues that while managers have obligations to the shareholders who have invested money in their company, they ought to take the interests of non-shareholder stakeholders such as workers, communities, and the planet into account in allocating the firm’s resources (Harrison et al., Citation2020). There is an extensive literature in management journals and in the business press about the contest between these two ideologies of corporate governance (Davis, Citation2021). In recent years, business leaders in the UK and the US have publicly repudiated the doctrine of shareholder primacy sparking debates over whether these public statements are mere rhetoric unconnected from actual spending decisions (Bae et al., Citation2021).

In reviewing the primary sources in the bank’s archive, we found evidence that both ways of thinking about the world influenced the thinking of the mid-ranking Barclays managers involved in the firm’s arts sponsorship activities. We need more archive-based research on similar tensions within other companies. Historians have begun to contribute to the debates about corporate purpose by exploring how managers in various historical contexts have variously challenged and supported the principle of shareholder primacy in published statements (Guenther, Citation2019; Smith et al., Citation2022). There should be additional business-historical research using the internal correspondence preserved in corporate archives to investigate how middle managers have thought about these issues. Such research could help us to determine whether there is a strong relationship between what senior corporate leaders say about corporate purpose and how firms actually allocate resources.

Disclosure statement

One of the authors has previously received funding from Barclays to conduct research on Barclays as part of their PhD research. However, that research was not used in the creation of this paper and no funding was received from Barclays for the research in this paper.

Notes

1. While the Johnson in this source refers to the Company Secretary Douglas Hamilton Johnson, we have been unable to confirm who J. G. F. was. The authors have been in contact with the archivists at BGA who believe him to have been an undersecretary for Johnson, but also could not confirm the full name. Regardless, these statements were seen internally as the opinions of Johnson rather than J. G. F., with Tuke mentioning that ‘I do not really quarrel with Johnson’s note’ in reference to the quoted document (Tuke, Citation1980b).

References

Archival material

- Alexander, D. (1978). A policy for the arts: Just cut taxes. Selsdon Group.

- Anti-Apartheid Movement, & Haslemere Group. (1975). Barclays and South Africa. AAM Archive, Bodleian Library. https://www.aamarchives.org/archive/campaigns/barclays-and-shell/bar07-barclays-and-south-africa.html

- Anti-Apartheid Movement, End Loans to Southern Africa, & Haslemere Group. (1978). Barclays and South Africa. AAM Archive, Bodleian Library. https://www.aamarchives.org/archive/campaigns/barclays-and-shell/bar08-barclays-and-south-africa.html

- Barclays. (1974–1987). Annual Reports.

- Barclays. (1980). Barclays Board Meeting. Barclays Group Archives.

- Barclays. (1981a). Barclays Bank PLC Report & Accounts 1981. Barclays. https://home.barclays/content/dam/barclays-jp/pdfs/group-overview/annual-report/2013/2013-barclays-annual-report-final.pdf

- Barclays. (1981b). Barclays Bank Group Board - Sponsorship. Barclays Group Archives.

- Barclays. (1984a). Barclays Bank UK Board. Barclays Group Archives.

- Barclays. (1984b). The Formulation of Community Relations and Sponsorship Budgets: Appendix B. Barclays Group Archives.

- Barclays. (1985). Sponsorship. Barclays Group Archives.

- Barclays. (1986a). Holding Statement. Barclays Group Archives.

- Barclays. (1986b). Sponsorship Committee Agenda. Barclays Group Archives.

- Barclays. (1987). Sponsorship Committee. Barclays Group Archives.

- Brierley, D. (1986). Letter to Mr Quinton. Barclays Group Archives.

- Brough, C. (1977). As you like it Private Support for the Arts. The Bow Group.

- Cobben, N. J. (1985). Note for Mr Quinton - Royal Ballet Overseas Tour. Barclays Group Archives.

- Cobben, N. J. (1986a). Note for Mr Quinton - Commonwealth Institute. Barclays Group Archives.

- Cobben, N. J. (1986b). Note to Mr J G Quinton. Barclays Group Archives.

- Dempsey. (2016). Arts Funding: Statistics (CBP 7655). House of Commons Library.

- End Loans to Southern Africa. (1981). Barclays and Shell. AAM Archive, Bodleian Library. https://www.aamarchives.org/archive/goods/badges/bar09-barclays-shadow-report-1981.html

- Goodenough, F. R., & Treble, R. J. (1983). Directors’ inspection - Group Public Relations Department (GPRD). Barclays Group Archives.