?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

The no liability company – where investors are not liable for uncalled parts of their shares – is unique to Australasia. Deploying a large dataset, we provide the first empirical examination of the effects of this new corporate type on company formation and shareholding. Victorian gold mining was the earliest and most pervasive user of no liability. No liability companies largely replaced limited liability within a decade of the legislation in 1871, which was more rapid than the transition from unlimited to limited liability companies in several other nations. No liability firms attracted a broader range of investors, geographically beyond the mining districts, and amongst occupations most conscious of their benefits, especially gentlemen and financiers who believed they were less risky because of the removal of call liabilities and the mitigation of previous regulatory failures. No liability was a response to the high risks of gold mining in an itinerant early settler society.

One of the most radical experiments in company law in the English-speaking world (Blainey, Citation1963, 99).

1. Introduction

In 1871 the Parliament of Victoria passed the Mining Companies Act (35 Vic. No. 409), which introduced into the colony the principle of no liability. Within a few years, the no liability (NL) company had largely replaced the limited liability (LL) form in the Victorian mining industry. Within 20 years, similar legislation had spread across the Australasian colonies to New South Wales (1881), South Australia (1881), Queensland (1886), Western Australia (1888) and New Zealand (1904). This innovation in company law has never spread beyond Australasia and remains an option for mining companies today under the Commonwealth of Australia’s Corporations Act 2001.Footnote1

Under no liability, a shareholder is not liable for the uncalled part of their shares, in contrast to limited liability. Mining shares are often issued partly paid to finance exploration, with later calls made to mine if the claim becomes profitable. If a company fails, LL shareholders may face further calls to cover incurred debts, while NL shareholders only lose the called part of their shares, often a small fraction of its par value. Mining, especially of gold, was a risky activity with many companies failing at the exploration stage. This has led scholars to conclude that the effect of the legislation was to make investment more attractive in a high-risk industry, and thereby drew in a broader range of investors (Blainey, Citation1963; Hall, Citation1968; Lipton, Citation2018; McQueen, Citation1991; Morris, Citation1997; Salsbury & Sweeney, Citation1988; Waugh, Citation1987). These conclusions have never been tested.

Historical research on transitions from unlimited to LL companies in other nations throws light on possible consequences of a further reduction in investor liability. Recent research has generally concluded that the impact on investment and investors was modest. Acheson et al.’s (Citation2010, p. 69) examination of the impact of LL (versus unlimited liability) on the tradability and liquidity of British banking stocks and the population size of their shareholders, ‘raise[d] some doubt about the role LL has played in the rise and subsequent dominance of the corporate form.’ Acheson and Turner (Citation2008, p. 251) reveal that UK banks continued to use unlimited liability after LL was permitted because there were no inherent weaknesses in the former system and conclude, ‘the perceived costs of limiting liability were higher than the benefits enjoyed’. Kenny and Ogren (Citation2021, pp. 217–218) conclude that ‘liability form mattered little’ among Swedish banks after 1897 when other legal differences between limited and unlimited firms were removed. Oskar (Citation2023) examines the use of ‘assessable stock’ (a form of unlimited liability) by quartz mining companies in the Comstock silver lode in Nevada (US) between 1860 and 1877, concluding that it provided a reliable method of raising capital for mining companies requiring capital in periodic tranches.Footnote2

These conclusions reaffirm the revisionist historical literature that throws doubt on the law-finance hypothesis, by arguing that informal private ordering often worked well, that legislation merely codified existing practice, and that economic and political contingency factors mattered more to changes in investment behaviour (Acheson et al., Citation2019; Cheffins et al., Citation2013; Musacchio & Turner, Citation2013). Viewed from this perspective, we might not expect the shift from limited to no liability to have had much impact on company formation and share ownership in Australian mining.

This paper builds on the existing literature by examining the impact of the transition from limited to no liability in a key Australian industry, mining, an innovation unique to Australasia and that persists to the present day. We describe the reasons for its introduction and offer the first empirical analysis of the effects of NL legislation on the location and occupational background of investors financing new company formation. It extends the international literature by investigating a further reduction in investor liability and providing an analysis of its effects on specific groups of investors. We draw on shareholder information from new mining company registrations in Victoria between 1857 and 1886. Our dataset comprises 84,973 investors who made 229,093 investments in 8,440 companies during the growth of the Victorian gold mining industry under LL and NL legislation. We argue that the NL firm largely replaced LL within a decade and broadened the geographic and occupational shareholder base.

2. Gold mining and Australian economic development

The Australian colonies had one of the highest standards of living in the world in the second half of the nineteenth century, the causes of which have been much debated (Broadberry & Irwin, Citation2007; Madsen, Citation2015; McLean, Citation2013). Prosperity drew heavily upon engagement with the world economy. A high foreign trade ratio derived from exports of natural resources, particularly gold and wool, extended by the later nineteenth century to wheat, frozen meat and dairy products. Natural resources constituted 90 per cent of visible exports, a figure only matched by a few other resource-based economies including Norway, and which paid for imports of manufacturing and capital goods (Ville & Wicken, Citation2013, pp. 1350–1352). Prosperity and economic opportunities attracted high levels of immigration and foreign investment to Australia. Flows of trade, investment, and migration came primarily from Britain. External sources of growth were supported by domestic drivers particularly urbanisation, residential construction, and the development of network industries most notably the railways (Butlin, Citation1964, p. 16).

Economic expansion was funded, and enterprises operated, by various domestic and foreign interests. Infrastructure, particularly railways, roads and ports, were largely owned and operated by the colonial governments but financed by British debentures. Agricultural producers were mostly small settler families, which were supported by a supply chain of foreign-owned firms such as brokers, bankers, insurers, and shipowners. Manufacturing largely lay in the hands of sole traders and small private companies but with a growing population of multinationals arriving, particularly from the UK, USA and Germany, by the end of the century (Ville & Merrett, Citation2020, pp. 331–337). Mining was one of the few major industries that provided opportunities for the domestic private investor.

The discovery of gold in Victoria in 1851 initiated one of the principal stimuli to Australian economic development in the nineteenth century. While major gold discoveries were also made in New South Wales and Queensland, Victoria dominated production until the boom in Western Australia in the 1890s (Morris, Citation1997, pp. 97–99). It commenced the growth of a substantial, if highly cyclical, industry that would reverberate through the colonies in the following half century. More than 20 million ounces of gold were mined in Victoria between 1851 and 1860 compared with 2 million in New South Wales. Overall, the value of gold mined in Australia in the 1850s was 6/7 times that of gross domestic product (Maddock & McLean, Citation1984, p. 1051). Gold mining contributed positively to the balance of payments and an increased population with the arrival of many immigrant prospectors. It provided a brief though very large stimulus to exports. The overseas trade of Victoria expanded massively in the 1850s from less than $2 million to over $28 million (Maddock & McLean, Citation1984, p. 1048). The population of the gold fields settlements north of Melbourne – primarily Ballarat, Bendigo, Castlemaine, and Mount Alexander – grew from 19,000 to 144,000 in the 1850s as prospectors arrived from other Australian colonies and from overseas including those leaving the recent Californian gold rush. Colony-wide reverberations were reflected in a five-fold expansion of the Victorian population to over half a million (La Croix, Citation1992, p. 209).

Such a large supply-side shock inevitably affected the size and competitiveness of other export industries, particularly wool, that lost labour to the goldfields (Butlin, Citation1964, p. 39). However, these effects were short-lived. Maddock and McLean (Citation1984, p. 1064) describe the role of population in-flows as an ‘equilibrating device’. After the initial rush subsided, many immigrants remained in Australia and worked in other industries such as pastoralism and market gardening. The influx of wealth into Melbourne was felt in the following decades as its population grew 3–4 fold (Hall, Citation1968, p. 530). The boom may have been temporary but it provided a ‘permanent increase in the scale of the Australian economy’ (Jackson, Citation1977, p. 11). The goldrush stimulated new local infrastructure, including road and rail transport between the mining centres and Melbourne, and the growth of banking services. Since most incorporated firms came from mining for the next few decades, it also drove the development of stock trading particularly on the colonial stock exchanges beginning with Melbourne in 1861 (Butlin, Citation1964, pp. 300–301; Hall, Citation1968, pp. 42–43). More broadly, it brought about the beginnings of an economy large enough to diversify across new industries, especially in manufacturing, and fostered specialisation within individual sectors including finance and natural resources (Ville, Citation1998, pp. 24–32). Finally, it motivated a unique development in company law, the no liability company, which is the focus of this paper.

The large short-term impact of Victorian gold mining in the 1850s reflected the inherently cyclicality of the industry, ‘rush’ epitomising its nature. Fluctuating gold prices and the serendipitous nature of prospecting created several large fortunes that attracted many hopeful entrants into mining, most of whom were unsuccessful. The earliest discoveries on the Victorian goldfields were made by individual prospectors, the so-called ‘diggers’, particularly in recovering surface alluvial deposits. By the late 1850s, when the easiest pickings had been extracted, a new phase in the industry began to take shape. Prospectors turned to more complex extraction often in deep lodes below the surface, some of which involved the removal of gold from rock, known as quartz mining. However, yields were falling: by 1871 Victorian gold output was barely above half its peak of the early 1850s (Kalix et al., Citation1966, p. 176). The reduced output required greater capital for machinery and other equipment. This attracted new firms into the industry to raise funds, initially as partnerships and syndicates, and then as companies. In this new phase of the industry, the risks and rewards shifted from individual prospectors to investors.

3. Mining investment, limited liability and no liability legislation

While the demand for mining funds was rising sharply, the lack of a public market for stocks or of legislation to govern enterprises were constraints on the supply of funds. A series of Acts were passed to regulate the formation of mining companies in 1855, 1858, 1860, and 1864. Each Act provided LL but was defective in other respects, particularly inconsistent reporting requirements and lengthy winding up procedures. Moreover, insufficient resources for adequate public administration of the Acts meant a failure to verify the veracity of investors and thereby prevent ‘dummyism’ (see below). The use of similar or identical names by different mining companies, another regulatory failure, also abetted investor deception (Ashley, Citation2005, pp. 208–210).

Therefore, while LL appeared to provide greater safeguards to investors in a highly cyclical industry, serious risks remained for the unwary shareholder in a Victorian gold mining company (Morris, Citation1997, pp. 103–107). LL set an upper bound on the exposure of investors but they remained responsible for the uncalled part of their shares, which was sometimes a large proportion of par value. Inadequate legislation allowed some investors to wilfully default through a practice known as ‘dummyism’, wherein they tendered false personal details to the company with a view to evading debts if the company was unsuccessful. The investor’s risks were also contextual to Australian mining. The lure of high profits and the information asymmetries associated with a transient mining population spread across broad areas also created breeding grounds for opportunistic promoters, who knowingly launched companies with few prospects with a view to pocketing investor funds. For the honest LL shareholder, Blainey (Citation1963, p. 98) notes, ‘no mining investor knew where his liability ceased’.

In August 1871 in the middle of a speculative company boom, the Select Committee on Mining Companies Law met to consider these challenges. It interviewed 18 witnesses including shareholders, mining investors, sharebrokers, journalists, and a mining registrar. Their evidence confirmed the defects of the LL legislation, particularly the process of collecting unpaid calls and of winding-up a company. One witness noted that the present system ‘enables men who understand the management of their business to escape all liability, and a few outside shareholders to be saddled with the whole liability of the company’ (F. Downes, para. 205). Local newspapers, however, were more sanguine (McQueen, Citation1991), believing that mining district investors were networked in the community, which generated trust and rich information flows about prospective areas for gold, reputable mining sponsors, and the feasibility of new mining technology. They argued that LL provided certainty with regards to liability, and the reputational damage of any local investor reneging on uncalled capital (if called) would be high. It has alternatively been suggested that mining investors, like many of the communities that supported them, were often transient in nature limiting the development of bonds of social capital, information flows, and even accurate shareholder identity (Lipton, Citation2018, p. 1313).

In November 1871, after considerable parliamentary debate of three bills, the Mining Companies Act was passed that brought into being the no liability company.

summarises the key differences between the LL and NL companies as enshrined in the Victorian legislation. Under both regimes, companies could issue partly paid shares that facilitated the phased introduction of new capital into a mine as it moved beyond the exploration stage. However, while investors in LL were required to meet future unpaid calls, those in NL had ‘no liability’ for uncalled portions. This difference might not be so important in the booming conditions of the 1860s, but it could matter in tighter monetary conditions or if the prospects of the firm were not good when investors might be reluctant to pour more funds into the firm. While this might imply LL was a preferable vehicle for sequential fund raising in the industry, this was often not the case in practice. If NL investors declined to meet unpaid calls they could not remain in the ‘club’ of owners with a dilution of value, nor at the other extreme were their shares written off by the company. Instead, their shares were publicly auctioned within 14 days for others to acquire who would meet the call, thus helping to maintain the flow of capital. The former investor would receive the net proceeds. The payment of unpaid calls on LL shares, however, often failed because of the practice of dummyism, mentioned above, and the complicated forfeiture procedures for unmet calls. Therefore, the 1871 Act formalised and simplified the forfeiture of partly paid shares, set stricter disclosure requirements on shareholders, and also introduced criminal offences for breach of duty and false statements by mining company representatives. These provisions and greater corporate disclosure requirements also differentiated NL and added to its investor appeal.

Table 1. No liability versus limited liability.

Historians have expressed various opinions on the effects of the Act. Morris (Citation1997, p. 109) and Birrell (Citation1998, pp. 98–100) concluded that investors turned quickly to the NL company, which they believe was the dominant form of mining organisation within a few years of the Act. Most writers conclude that the Act stimulated broad investor interest in mining. Hall (Citation1968, p. 77) suggested that the NL Company provided a vehicle for maintaining the supply of funds into mining, confirmed by its continued use today. Salsbury and Sweeney (Citation1988, p. 37) described the legislation as making ‘mining shares available with limited risk to almost every member of the Australian public’. Blainey (Citation1963, p. 99), a leading authority on Australian mining history, was quoted at the beginning of this article that it was ‘one of the most radical experiments in company law in the English-speaking world’, since the ‘trap for mining speculators was finally sealed’. Similarly, Lipton (Citation2007, p. 820) emphasises the ‘more stringent disclosure requirements’ and the creation of ‘various criminal offences…for breaches of duty and for making false statements’ as facilitating broader investor interest. Birrell (Citation1998), however, is less convinced by the legislation stating that it merely legitimised existing behaviour on the goldfields.

Several writers have suggested particular groups were attracted into mining in greater numbers due to no liability. For Blainey (Citation1963, p. 99), the mitigation of risk ‘spurred the wealthy men to invest in mining’, while the custom of instalments for issuing partly paid shares ‘encouraged poor men to buy mining shares’. It has also been suggested that increased investor interest was more noticeable in the cities than in rural communities (McQueen, Citation1991, p. 27). None of these perspectives has been subject to close empirical analysis.

We expect that risk-averse investors would be more attracted to NL than to LL companies, resulting in different shareholder bases for the two types. In an industry where shares were frequently issued partly paid to await the outcome of exploration, NL enabled investors to choose whether to participate in the continued expansion of the enterprise without the risk of defaulting. The richer information environment also reduced investment risk since NL companies had to meet stricter disclosure requirements with regards to shareholder names, addresses and occupations, along with the provision of standardised company financial reports. NL companies had a well-defined mechanism for solving the problem of reneging shareholders, thus decreasing the risk that the company would not be able to raise the required equity under a capital call. Finally, it is possible that NL companies were less likely to raise debt, with its associated risks, because creditors could not necessarily draw on the reserve liability that was a feature of LL with partly paid shares (Acheson et al., Citation2012; Jeffreys, Citation1946, p. 49).

The hypothesis that a NL company was more attractive than a LL company to a risk-averse investor is tested with regards to the residential location and occupation of the investor. First, we hypothesise that the risk mitigation features of NLs would be attractive to investors located further away from the mining districts where they would have suffered from information asymmetries, particularly in relation to the geological environment for mining, the progress of the firm’s exploration activities, and the character and reputation of the mine mangers and other investors. Hypothesis 1 is therefore stated in an alternative form:

H1: NL companies are more likely than LL companies to raise equity from city investors.

H2: There is no difference between NL and LL with regards to investment by occupational groups

4. Data

Our main source is the Mining Shareholders Index, which is a record of all shareholders for every mining company established in Victoria between 1857 and 1886 that was listed in the Victorian Government Gazette.Footnote3 The data consist of a list of companies with the par value of their shares, the date of establishment, and location of the company and its mine. The great majority of these companies were goldminers, which is indicated by our knowledge of the mining industry and by the many firms that contained words like gold, quartz or alluvial in their title. The shareholder information comprises their name, occupation, residential address (area/city), and number of shares held. The Mining Companies Act 1871 required that a register of shareholders be kept and contain ‘the names and addresses and, if known, the occupations of the shareholders in the company’.Footnote4 Previously, companies had only to maintain shareholder addresses.Footnote5 Therefore, we can compare the location (residential address) of shareholders in LL companies and NL companies from 1857 to 1886, most relevant for the first research question. However, the data to answer the second research question focuses on the differences in occupation of shareholders between LL and NL companies from November 1871 onwards.

Our analysis examines initial shareholders or ‘subscribers’, that is, the investor who subscribed at the initial equity raising. While this data has limitations (for example, investors could have sold their shares to another party immediately after subscribing), subscription lists provide the most accurate information on who was willing to invest in new mining ventures. In supporting their use of subscription lists, Campbell and Turner (Citation2012, 8–9) note that shareholders who made the largest profits during the British railway mania were subscribers rather than those who purchased shares later. The period between initially financing a mining venture and discovery of gold could be several months or more, meaning that the opportunity for a subscriber to sell their shares early at a profit would be limited. In addition, since most companies were unlisted a secondary sale may have been difficult or at a substantial discount.

Our data comprises 84,973 investors who made 229,093 investments in 8,440 companies in the decade and a half before and after the 1871 Act (, Panel A). The term ‘No Liability’ had to be included in the company name, which enables us to differentiate between LL and NL companies. We calculate the company’s par value as the total number of shares multiplied by their par value. We define an investment by a shareholder as a parcel of shares that they subscribed to in the company. Since we have the number of shareholders per company and each shareholder’s parcel of shares (number of shares and total par value), we can calculate the total number of shareholders in each company and a Herfindahl index measuring the concentration of shareholders. For the period where we have occupational information (November 1871–1886), we also calculated the percentage of shares held by insiders (defined as mine manager who were legally responsible for the mining company). provides definitions of our variables.

Table 2. Victorian mining company registrations, 1857–1886.

The number of new mining company registrations in Victoria, 1857–86, by LL and NL (from November 1871) is reported in . There were 8,440 companies established, with investors subscribing £96,206,597. Most companies were alluvial miners (72 per cent) and the remainder quartz. Between 1857 and October 1871, 4,806 mining companies were established under LL legislation, with an aggregate £52,336,392 in subscribed capital from 55,156 investors (and 41,079 investments). From November 1871 to 1886 there were 3,634 mining companies established as either LL or NL, for a total par value of £43,870,205. During this period an additional 29,817 investors made their first investment in a mining company. Of these latter companies, the majority were NL (2,247) in which 21,132 investors held shares, while 1,387 LL companies attracted 27,923 investors. LL companies were, on average and by median, larger than NL companies.

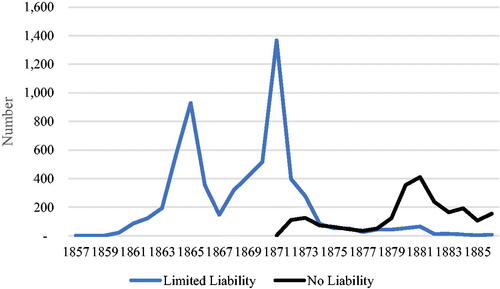

Trends in mining company formation are shown in . There are peaks under both liability forms, most notably LL between 1864 and 1865, and 1870 and 1872, and NL between 1880 and 1882. The periodic ‘booms’ in company formation were not associated with an aggregate increase in gold production although most witnessed an increase in share prices and the volume of trading.Footnote6 While new fields opened throughout the period (Blainey, Citation1970, pp. 298–313), the overall industry was in decline and gold production fell in Victoria from 1.289 million fine oz in 1871 to 0.626 million fine oz in 1886 (Kalix et al., Citation1966, p. 176). Peaks in company formation were driven by spillover effects; a few companies would find gold in an area, encouraging others nearby to call additional capital to explore their claims along with the establishment of hopeful new companies. As a speculative boom started to run out, prices for listed companies would fall and disillusionment set in. Thus, ‘periodic bursts of mining speculation’ were a feature of the period, resulting in most companies having ‘a very transient life’ although ‘some hundreds of companies’ would have figured in the financial pages of the local and Melbourne newspapers and be known to investors (Hall, Citation1968, pp. 62, 59).Footnote7

Figure 1. New mining company registrations – number of limited liability and no liability companies, 1857–1886.

Source: Mining Shareholders Index; Victorian Government Gazettes.

Most new companies (LL or NL) were private and closely held, with few having shares traded regularly on the Melbourne Stock Exchange or on the local exchanges in Bendigo and Ballarat (the two main regional exchanges). Hall states that there were 133 mining companies on the Melbourne Stock Exchange in 1865 and we located an additional 67 that had shares traded on the local exchanges.Footnote8 This compares with 929 mining companies established in that year. By 1870, 118 mining companies traded on the Melbourne Stock Exchange although there had been 1,749 mining companies established between 1865 and 1870. While survival rates for companies are difficult to calculate, we estimate that no more than ten per cent were regularly traded on the Victorian exchanges.

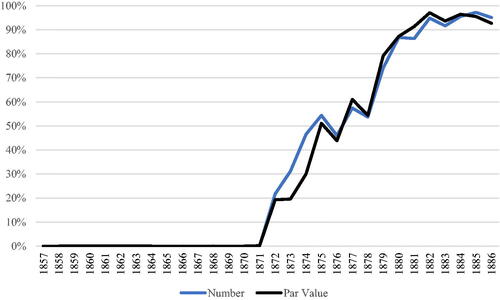

The NL form was adopted slowly at first with similar numbers of new companies still opting for LL in the first few years (). It was not until a new wave of investor interest in mining and a speculative mining boom gathered pace towards the end of the 1870s that most new firms were of the NL type, which virtually superseded LL by the early 1880s.

Figure 2. Percentage of no liability by number of companies and capital (par value), 1857–1886.

Source: Mining Shareholders Index; Victorian Government Gazettes.

Adoption of the NL legislation, therefore, was somewhat more gradual than implied by the prior literature (Blainey, Citation1963; Morris, Citation1997, p. 109). However, this response to the NL legislation in Australia was still quicker than the investor reaction to the legal transition from unlimited to limited liability in several other countries, as we discussed earlier (Acheson & Turner, Citation2008; Kenny & Ogren, Citation2021).

The reasons for the rate of uptake are not entirely clear. A general sense of inertia or caution may have initially prevailed as promoters and investors sought to understand their potential benefits or drawbacks. Some safeguards for unpaid calls may already have been available informally. Birrell (Citation1998) has suggested that by 1870 ‘the stock exchanges on the goldfields had developed a system where, by mutual agreement, shareholders with unpaid calls were not immediately forced to pay the call’ (1998, pp. 99, 117). However, informal understandings, especially in the context of transient mining populations, may have been less compelling in the minds of potential investors than legal protection under NL. Creditors may have been circumspect about the impact of the further limits on the financial liabilities of investors and whether this would affect the quality of shareholders as has been observed for UK banks with the rise of LL (Turner, Citation2009). However, the Australian position seems somewhat different. The financial commitments of NL shareholders did not extend beyond the initial call and therefore there may have been less concern about shareholder quality. The prompt auction of shares with unpaid calls, the greater transparency of company and investor information, and the streamlining of winding up procedures all improved the tradability (listed or via private placement) of NL shares.

5. No liability, limited liability, and the location of investors

It has been argued that the reduced risks of the NL legislation attracted more investors from a broader geographical area, given the likelihood that information asymmetries increase with distance. Our focus is on Melbourne as a growing centre of population and wealth in mid nineteenth-century Victoria and a major beneficiary of the gold rush as we saw earlier. Knowledge of the booming mining industry 100 to 150 kilometres to Melbourne’s north and the improved infrastructure and communications to and from the goldfields as gold exports passed through the city’s financial institutions and ports would have awakened city investors to new opportunities.

In order to examine Hypotheses 1 – that the introduction of no liability resulted in more investment into mining companies from investors residing in the city – we use data from 1857 to 1886. Residential addresses were reported in various ways, used different names for the same town/area, or used abbreviations. We standardised town and area names, resulting in a distinct location for 94.2% of investors (107,836 investors). The uncategorised locations were due to incomplete or ambiguous information. We define city investors as residing in Melbourne or Geelong (Victoria’s second largest city) ().

Table 3. Total par value, number of investments and investors by location, 1857–1886.

Investors residing in ten mining towns provided 60.8% of total par value, with investors from other mining towns 20.4%. Sandhurst (Bendigo) and Ballarat were the two dominant locations in terms of capital (47.2%), number of investments (40.1%) and number of investors (30.3%).

The capital and investors from non-mining locations were largely located in the city of Melbourne, comprising 17.8% of capital and 20.8% of investors. City investors provided less capital in aggregate than either Sandhurst or Ballarat, who were closer to the mining activity, but were the largest group by number of investors and second largest by number of investments (Ballarat being the largest). The 1881 Victorian Census reported that Sandhurst had 45,590 residents and Ballarat 76,092, implying that approximately 25% to 30% of residents in these mining towns held shares in mining companies. By contrast, Melbourne and Geelong combined had 297,513 residents in 1881, with approximately 7.5% of residents holding mining shares.Footnote9

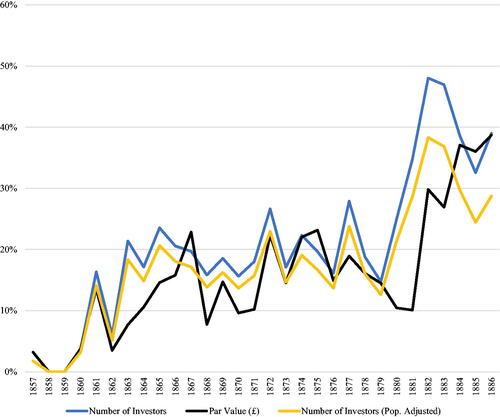

The proportion of capital and of investors from the city increased from under 10 per cent in the late 1850s to around 40 per cent by the mid-1880s (). This finding holds when we adjust the number of city-based investors for the rapid growth in population experienced by Melbourne (and Australia). Melbourne’s population grew from an estimated 140,000 in 1860 to 491,000 in 1890, while the population of Australia in total grew from 1.145 million in 1860 to 3.15 million in 1890 (Butlin et al., Citation2015, pp. 555–594; Hall, Citation1968, p. 53). The population-adjusted proportion of city-based investors companies increased from an average of 14% between 1860 and 1870 to an average of 30% between 1880 and 1886.

Figure 3. Proportion of capital (par value) and investors from the city.

Source: Mining Shareholders Index; Victorian Government Gazettes.

To test Hypothesis 1 we regress whether the company was NL (NL = 1) against the per cent of shareholders (shares) held by city investors, company characteristics and ownership and share characteristics (discussed below). All regressions are estimated using year fixed effects. The regression model is:

We estimate the model using two city location variables: the percent of shareholders (by number) located in the city and the per cent of shares held by shareholders in the city. We also report results for a model using an alternate location variable for investors located in the mining districts (the per cent of shareholders (by number) located in mining districts and the per cent of shares held by shareholders in mining districts). The company characteristics are size as measured by the natural logarithm of the par value of the company, and the type of mining (alluvial or quartz). Share ownership variables are (1) the number of shareholders and (2) a Herfindahl index measuring the concentration of shareholders for each company. We include the denomination of each share, as several studies have shown that the denomination of a company’s shares influences the shareholder base (Acheson et al., Citation2012, Citation2017; Jeffreys, Citation1946). provides summary statistics for the regression variables.Footnote10

Table 4. Summary statistics for location regressions.

A correlation analysis of the regression variables used in the regressions did not identify any variables that were highly correlated with each other and variance inflation factors for the four estimations were around 2.0, indicating that multicollinearity is not a major concern. The regression results are reported in .

Table 5. Regressions on location and no liability companies.

A mining company with a higher proportion of city investors (by number or by share ownership) was more likely to be a NL company. It was also likely to be smaller, have a larger shareholder base by number, have more concentrated ownership (as measured by the Herfindahl index), and offer higher denomination shares. A mining company with a higher proportion of shareholders (by number or by share ownership) from the mining districts was less likely to be a NL company. Mining companies with more mining districts shareholders were smaller, had a small shareholder base, and were established with higher share denomination. Overall, the results lend support to Hypothesis 1. The introduction of NL companies was associated with a change in the distribution of shareholders by location, with NL companies attracting proportionally more city-based shareholders than LL companies.

6. No liability, limited liability and the occupational status of investors

Hypothesis 2 states that there is no difference between a LL and a NL company with regards to the occupational composition of their shareholders. The Gazette contains a myriad of occupations, self-identified by shareholders as there was no definition of occupation (or occupational group) stipulated in the Act. We found 160 occupations with 30 or more individuals and 80 occupations, which had 100 or more individuals.Footnote11 We were able to allocate 50,919 investors (91.2%) to an occupational group.

Studies of British shareholders in the nineteenth century consolidate the range of occupations into shareholder groups that reflect socio-occupational constituencies (Acheson et al., Citation2017; Campbell & Turner, Citation2012). However, there are some differences in defining occupations in nineteenth-century Victoria as industrialisation, specialisation and urbanisation introduced new types of jobs, increased the number of people working in existing occupations, and changed the distribution of income and wealth in the economy (Francis, Citation1993; Rickard, Citation2017, chapter 4; Van den Broek, Citation2011). Added to this is the geographic and occupational mobility of individuals and the measurement issues associated with self-reported occupations and/or census information on occupations (Griffen, Citation1972; Van Leeuwen et al., Citation2004). Therefore, we adopt broad occupational definitions when testing Hypothesis 2 (e.g. middle class, working class), which mitigates to some extent the difficulties associated with changes in occupational identity and mobility. We are also cautious in comparing our results with the more tightly defined occupational categories and class definitions of UK studies.

Mining industry shareholders were those involved in all aspects of mining who, a priori, would have a knowledge advantage over other occupations regarding the location of the mine, proposed business operations and long-term viability. Occupations included mine managers, miners, mine agents, mining engineers, quartz miners and quartz crushers. Businessmen are categorised as retailers, manufacturers and merchants. Financiers are bankers, stockbrokers and other finance professionals (actuaries, accountants, bookkeepers).Footnote12 Financiers also include those who described themselves as investors and speculators. Middle class comprises legal occupations, professionals such as surgeons, doctors, architects, dentists, chemists, engineers, surveyors, senior managers, and white-collar workers. Working-class shareholders are both skilled (requiring some level of education and training including apprenticeships) and unskilled. Agriculture is occupations involved in working the land or that produce directly from it.

We categorise gentleman and female separately as occupational groups. Gentlemen are assumed to be men who do not depend on regular employment for income. There is less need for distinction in Victorian Australia between nobility, gentlemen and esquires, as discussed in Acheson et al. (Citation2017, pp. 613–614). We do, however, record politicians as a separate occupation since they were regarded as important members of society and may have had access to privileged information. We retain female as a distinct group not requiring an occupation for income as well as shareholders who stated they were female and had an occupation (such as Female-Hotelkeeper). A more comprehensive description of the occupational groups is provided in Appendix A2.

As shows, beyond the mining industry itself, the most important investors were businessmen (14.6% by capital; 19.3% by number of investments and 17.3% by number of investors) and gentlemen (12.1% by capital, 11.9% by investment, and 12.9% by investors). Capital was also provided by middle classes (10.3% by capital), financiers (9.9% by capital), working class (5.8% by capital), agriculture (3.3% by capital) and females (1.4% by capital).

Table 6. Total par value, number of investments and investors by occupation 1871–1886.

We also note that the par value per investor was lower for occupational groups such as working class, agriculture and female investors.Footnote13 Each group comprised a larger proportionate share by number of investments and by investor than they did by par value, possibly due to a preference by these occupational groups for lower share denomination equity raisings. We will explore this feature of share ownership in more detail in our regression analysis. In sum, our data provides the first quantitative evidence of widespread engagement by the public in the capital markets of colonial Australia and that working class and females (in particular) were not excluded from investment opportunities in the height of gold mining activity in the 1870s and 1880s. Panza and Williamson (Citation2019) note that there was an egalitarian levelling of Australian wealth between the 1820s and 1870s. The fact that a cross-section of society had financial means to invest in mining companies between 1871 and 1886 is consistent with their findings.

Research on the British stock market during the nineteenth century indicates the existence of clientele effects whereby specific groups of shareholders had investment strategies that favoured firms with particular characteristics (Acheson et al., Citation2017). In order to test Hypothesis 2, we regress the legal type of the company (NL = 1) on the seven main occupation groups (mining is the default investor group in all regressions).Footnote14 The regression model is shown in the equation below, where the dependent variable Legal type is an indicator variable that returns one if the company is a NL company:

There are seven occupation variables defined as the percentage of shares held by that occupation. We also include a variable for insiders, defined as the percentage of shares held by mine managers (the mine manager is legally responsible for the operation of the company who would be expected to have the most accurate information on the company and its prospects). In addition, we include the location of the investor, company characteristics and share ownership and par value.Footnote15 For location, we differentiate between investors located in the city and the mining districts. As with our previous analysis, we use two definitions for location: the percentage of shares held by an investor by location and the percentage of shareholders by number by location. Company characteristics are size and the type of mining (alluvial or quartz), share ownership variables are the number of shareholders and a Herfindahl index measuring the concentration of shareholders for each company, and we include the denomination of each share (Par Value of Shares in Australian pounds). A correlation analysis of the regression variables used in the regressions indicated that the percentage of shares held by gentlemen and by middle class were positively correlated with per cent of shares (and number of shareholders) held by city investors (0.27 and 0.23 respectively, significant at the 1% level). Similarly, there was a significant negative correlation between the percentage of shares held by gentlemen and by middle class and percentage of shares (and number of shareholders) held by mining districts investors (−0.25 and −0.22 respectively, significant at the 1% level). All other variables were not highly correlated with each other. Variance inflation factors for the two estimations were around 2.9, indicating that multicollinearity is not a major concern. We estimate the regression with and without year fixed effects. provides the summary statistics for the occupational regressions.

Table 7. Summary statistics for occupation regressions.

The first set of regressions (columns 1 and 2) in are estimated without year fixed effects. These results indicate that NL firms attracted proportionally more interest from all occupational groups (except females) than did LL firms. Once we control for year effects (columns 3 and 4), however, we find that NL companies had proportionately more gentlemen, financier and agriculture investors. The gentleman investor is best understood as part of a wealthy rentier class looking for a return on their assets.Footnote16 Their increased commitment to mining after the passage of the no-liability Act appears to lend support to Blainey’s belief that the legislation, by mitigating various sources of risk, would attract more wealthy individuals who had no direct working relationship with mining. By all measures, the financier played a more important role in NL companies. They were primarily investors employed in the financial industry such as bankers, company promoters and stockbrokers. British studies suggest this group were heavy traders who knew the market and sought to benefit from buying and selling (Acheson et al., Citation2017). If NL shares were highly tradeable, as discussed above, this may help to explain the increased prominence of this class of investor.

Table 8. Regression on no liability companies and occupational group.

The city location variables are positively associated with NL companies with either definition of location – by shareholding or the percentage of shareholders by number – in the year fixed effects regressions. NL companies had a higher proportion of investors from outside the mining districts, lending credence to existing historiography that NL legislation widened the shareholder pool.

Finally, NL companies were likely to be smaller companies, have a larger number of shareholders, and higher shareholder concentration as measured by the percentage of shares held by insiders and by the Herfindahl index. This suggests that investors were more comfortable investing in companies with insiders, even if smaller, as NL better protected shareholders from reneging and enforcement problems of LL companies in Victoria at the time. We also note that NL companies had higher par value than LL companies, contrary to what one might expect if tradability of shares was a concern for investors.

In summary, NL mining companies had different shareholder bases than LL companies, with the number of shareholders and amount of capital varying by occupational group. We reject Hypothesis 2. It is possible that NL companies reduced the perceived risk of reneging in LL companies for some investors, resulting in more investment (in aggregate and on average) as compared with LL companies. Mining shareholders were less enamoured with NL companies, perhaps mitigating any deficiencies in the LL legislation and its enforcement via private contracting and local information advantages. By contrast, gentlemen, (and other shareholders over time) could not mitigate deficiencies in LL companies and therefore gravitated towards NL companies.

7. Conclusion

The NL firm has been a legal form of corporation unique to the Australian mining industry, which continues in widespread use today. Deploying a large dataset of shareholders, we examined the effects of its earliest and most pervasive adoption in the Victorian gold-mining industry from 1871. Its distinguishing feature, that shareholders were not required to meet unpaid calls, aimed to reduce investor risks in a highly cyclical and speculative industry. The legislation also provided greater regulatory and disclosure safeguards for investors in these companies. The mining industry had attracted a broad range of investors by occupation and location. The introduction of NL legislation, though, created several important changes to the pattern of investors. We suspect that the legislation mitigated several types of risks, particularly in relation to information asymmetries and regulatory failures. As a result, more investors were attracted from beyond the mining districts and amongst those investors conscious of the reduced risks they offered, particularly financiers and gentlemen.

The choice of the legal form of enterprise in different nations and whether it mattered for economic development remains a source of on-going debate (Gelderblom et al., Citation2013; Guinnane et al., Citation2007). The corporate form was popular in the UK and the US in the nineteenth century to serve the needs of large-scale enterprise in common law nations, particularly for capital raising and its protection through public trading, separate legal personality, and LL. Partnerships remained more important in European countries with a substantial population of SMEs that valued flexibility of organisational structure. Guinnane (Citation2021) has analysed the private (non-public trading) LL company that was introduced in Germany in 1892, the GmbH, that appeared to provide a compromise between corporate and partnership forms. He notes its late adoption in the US whose economic success occurred, he argues, in spite of rather than because of the large-scale enterprise that was the focus of writers like Chandler (Citation2009).

Australia was also an early adopter of the private company – in 1896 – for once leading rather than following UK practice. It had earlier also deviated from UK company law to introduce LL partnerships for mining in the 1853 before turning to the corporate form. Mining needed substantial and sequential phases of capital, which partly paid shares in LL companies appeared to serve. However, as we saw, the LL Mining Acts encountered enforcement problems in the face of opportunistic behaviour by some investors. The cost book system used in Britain by Devon and Cornwall tin miners might have offered an alternative solution. Its need for regular funding decisions was akin to the experience of Victorian mining. However, it involved all members signing the memorandum of association and meeting regularly to agree on additional expenditures and new calls as they became necessary. It suited close-knit societies such as the mining communities of Devon and Cornwall but disadvantaged more distant shareholders unable to attend regular meetings. Thus, despite the use of the cost book by several British owned mining companies in Australia, it did not suit the character of shareholding in Victoria in which investors were often unknown to each other. Neither the cost book partnership nor the LL company form, therefore, was a good fit for high-risk mining companies in a location like colonial Victoria where the population was transient and mobility high (Birrell, Citation1998, p. 67; Morris, Citation1997, pp. 92–97). NL, on the other hand, preserved the benefits of a regime of partly paid shares while addressing the information asymmetries associated with investment in an early-stage settler society.

Whether this unique legal form was important for economic development in Australia’s case is more difficult to assess. NL replaced LL companies in Australia much more quickly than LL superseded unlimited liability in several British industries, as we saw in the introduction, and NL appears to have impacted more on investor choices. However, NL changed the character of the investing class rather than increased the amount of capital invested in the industry. More long-term, though, it may have been an early trigger for a broader domestic investing population in the Australian colonies that began to replace reliance on the London capital market by the end of the nineteenth century (Merrett, Citation1997; Merrett & Ville, Citation2009).

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank participants at the Asia Pacific Economic and Business History Conference (January 2022) and the 4th West Coast Finance Colloquium (February 2022) for helpful comments on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Grant Fleming

Grant Fleming is a partner at Continuity Capital Partners, an investment management firm. Prior to co-founding the firm, he held investment positions at Wilshire Associates Inc. and academic positions at the Australian National University and the University of Auckland. His research interests include financial and business history, funds management, private equity, and private credit.

Zhangxin (Frank) Liu

Dr Zhangxin (Frank) Liu is currently a Senior Lecturer of Finance in the Department of Accounting and Finance at the University of Western Australia. He works in the areas of asset pricing, corporate governance, and economic history.

David Merrett

David Merrett is Emeritus Professor in the Department of Management and Marketing at the University of Melbourne. He has published widely on Australian economic and business history, including International Business in Australia before World War One: Shaping a Multinational Economy (2022), co-authored with Simon Ville.

Simon Ville

Simon Ville is Senior Professor of Economic and Business History at the University of Wollongong. He has written extensively on big business, foreign investment, the rural and resource industries, natural history trading, social capital, transportation history, and the Vietnam War, which has been published with many highly ranked journals and publishers.

Notes

1 In Citation2022 there were 178 NL companies in Australia (ASIC database).

2 Assessable stock allowed the company board of directors to call on shareholders to supply additional funds over and above their current paid-up shares.

3 All Gazettes are available at: http://gazette.slv.vic.gov.au/. The data was collected by Marion McAdie and provided to the authors.

4 Section 33 (I), Mining Companies Act, 23rd November 1871, Supplement to the Victorian Government Gazette 24.11.1871, p. 86.

5 Section 4, Mining Companies Limited Liability Act 1864, 02.06 1864; Supplement to the Victorian Government Gazette, 07.06.1864, p. 506.

6 An empirical examination of the Victorian mining share market in the nineteenth century has yet to be completed. As a result, we cannot determine whether the three mining ‘booms’ during this period would satisfy the Quinn and Turner (Citation2020) definition of a speculative bubble; viz. ‘a rise in asset prices of at least 100 per cent over less than 3 years, followed by at least a 50 per cent collapse in prices over a 3-year period or less’.

7 Hall (Citation1968, pp. 18–22) identifies the first speculative boom as 1859, which for the first time introduced mining investment opportunities to Melbourne investors through listed shares. When the speculative boom burst later that year, it was ‘some years before Melbourne investors again invested freely in mines’ (p. 20).

8 Hall (Citation1968, , p. 58) reports the number of mining companies on the Melbourne Stock Exchange for 1865, 1870, and 1884. We selected five benchmark years 1865, 1870, 1875, 1880 and 1885 to cross-check Hall’s data using share price lists published in local newspapers during December for the Melbourne Stock Exchange, the Ballarat exchange, the Bendigo exchange, and smaller exchanges such as Stawell. In most cases we identified additional companies which were listed on price lists and reported as having a traded price. We calculate that the number of listed mining companies in Victoria was 200 in 1870, 118 in 1870, 96 in 1875, 146 in 1880 and 120 in 1885.

9 If we use the 1871 Census as our benchmark year, Sandhurst had 49,369 residents and 13,591 investors (28%) and Ballarat had 94,618 residents and 19,044 investors (20%). Melbourne and Geelong had 225,826 residents and 22,414 investors (10%).

10 Data was not available to calculate firm size for eight (8) companies, resulting in 8,432 observations in our regressions.

11 While self-reported occupations may be subject to inaccuracy (Acheson et al., Citation2017, p. 613; Campbell & Turner, Citation2012, p. 11), the 1871 Mining Act required the company’s legal manager to attest in the company application (and Gazetted) that all information was to the best of their belief ‘true in every particular’, and ‘rendering persons making a false declaration punishable for wilful and corrupt perjury’.

12 Bank managers and bank officials are included as financiers as they most likely had the most experience in investment matters and the means to invest. Lower rank employees (e.g. bank clerk, bank messenger) are categorised as middle class (see Appendix A2). On bank internal labour markets see Merrett and Seltzer (Citation2000) and van den Broek (Citation2011).

13 There is a caveat on interpreting data on female investors due to a sex imbalance. In 1870 there were 121 males for every 100 females. Using 1871–75 as an example, there were 13,734 investors, of which 1,006 were female investors or 7.3% of all investors, which can be scaled up by the sex ratio to an adjusted 8.9. This compares with 1,396 gentlemen comprising 10.2% of all investors.

14 We exclude politicians, where there were 71 investors.

15 There were 3,634 companies established between November 1871 and 1886. Data was not available to calculate firm size for two (2) companies, resulting in 3,632 observations. There were 3,062 companies where the mine manager was identified. Therefore, we estimate all regressions on the 3,062 companies where all variables are available.

16 In the UK the term ‘gentleman’ had connotations of social class as members of the landed gentry but by the second half of the nineteenth century it was used more broadly as someone of sufficient means not to require work or who was retired (Acheson et al., Citation2017, pp. 613–614).

ReferencesGovernment Publications

- Report from the Selection Committee on the Mining Companies Law Amendment Bill (2) together with The Proceedings of the Committee, Minutes of Evidence, and Appendices, 12 October 1871, Victorian Legislative Assembly.

- An Act to limit the Liability of Mining Companies, 2nd June 1864, published as a Supplement to the Victorian Government Gazette, of Tuesday, 7th June 1871.

- An Act for the Incorporation and Wind-up of Mining Companies, 23rd November 1871, published as a Supplement to the Victorian Government Gazette, of Friday, 24th November 1871.

- Victorian Government Gazette, various issues.

Newspapers

- The Age.

- The Argus.

- The Australasian.

- The Ballarat Star.

- The Bendigo Advertiser.

- The Empire.

- The Herald.

Secondary sources

- Acheson, G. G., Campbell, G., & Turner, J. D. (2017). Who financed the expansion of the equity market? Shareholder clienteles in Victorian Britain. Business History, 59(4), 607–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2016.1250744

- Acheson, G. G., Campbell, G., & Turner, J. D. (2019). Private contracting, law and finance. The Review of Financial Studies, 32(11), 4156–4195. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhz020

- Acheson, G. G., Hickson, C. R., & Turner, J. D. (2010). Does limited liability matter: Evidence from nineteenth-century British banking. Review of Law & Economics, 6(2), 247–274. https://doi.org/10.2202/1555-5879.1444

- Acheson, G. G., & Turner, J. (2008). The death blow to unlimited liability in Victorian Britain: The City of Glasgow failure. Explorations in Economic History, 45(3), 235–253. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eeh.2007.10.001

- Acheson, G. G., Turner, J. D., & Ye, Q. (2012). The character and denomination of shares in the Victorian equity market. The Economic History Review, 65(3), 862–886. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2011.00618.x

- Ashley, R. (2005). Mining the Victorian Government Gazette. A treatise upon the Ashley mining index: Mining companies applying for registration in Victoria 1860-1864. Journal of Australasian Mining History, 3, 205–211.

- ASIC (2022) – Company Database. https://data.gov.au/data/dataset/7b8656f9-606d-4337-af29-66b89b2eeefb

- Birrell, R. W. (1998). Staking a claim: Gold and the development of Victorian mining law. Melbourne University Press.

- Blainey, G. (1963). The rush that never ended. A history of Australian mining. Melbourne University Press.

- Blainey, G. (1970). A theory of mineral discovery: Australia in the nineteenth century. The Economic History Review, 23(2), 298–313.

- Broadberry, S., & Irwin, D. A. (2007). Lost exceptionalism? Comparative income and productivity in Australia and the UK, 1861–1948. Economic Record, 83(262), 262–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4932.2007.00413.x

- Butlin, M., Dixon, R., & Lloyd, P. J. (2015). Statistical appendix: Selected data series, 1800–2010. In S. Ville & G. Withers (Eds.), The Cambridge economic history of Australia (pp. 555–594). Cambridge University Press.

- Butlin, N. G. (1964). Investment in Australian economic development, 1861–1900. Cambridge University Press.

- Campbell, G., & Turner, J. (2012). Dispelling the myth of the naive investor during the British Railway Mania, 1845-1846. Business History Review, 86(1), 3–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680512000025

- Chandler, A. D. (2009). Scale and scope: The dynamics of industrial capitalism. Harvard University Press.

- Cheffins, B. R., Bank, S. A., & Wells, H. (2013). Questioning ‘law and finance’: US stock market development, 1930–70. Business History, 55(4), 601–619. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.741974

- De Lissa, A. (1894). Companies’ work and mining law in New South Wales and Victoria. George Robertson and Company.

- Francis, R. (1993). The politics of work: Gender and labour in Victoria, 1880-1939. Cambridge University Press.

- Gelderblom, O., De Jong, A., & Jonker, J. (2013). The formative years of the modern corporation: The Dutch East India Company VOC, 1602–1623. The Journal of Economic History, 73(4), 1050–1076. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050713000879

- Griffen, C. (1972). Occupational mobility in nineteenth-century America: Problems and possibilities. Journal of Social History, 5(3), 310–330. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh/5.3.310

- Guinnane, T. W. (2021). Creating a new legal form: The GmbH. Business History Review, 95(1), 3–32. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680520000707

- Guinnane, T., Harris, R., Lamoreaux, N. R., & Rosenthal, J. L. (2007). Putting the corporation in its place. Enterprise and Society, 8(3), 687–729. https://doi.org/10.1093/es/khm067

- Hall, A. R. (1968). The stock exchange of Melbourne and the Victorian economy, 1852-1900. ANU Press.

- Jackson, R. V. (1977). Australian economic development in the nineteenth century. ANU.

- Jeffreys, J. B. (1946). The denomination and character of shares, 1855-1885. The Economic History Review, 16(1), 45–55.

- Kalix, Z., Fraser, L. M., & Rawson, R. I. (1966). Australian mineral history: Production and trade, 1842-1964. Department of National Development.

- Kenny, S., & Ogren, A. (2021). Unlimiting unlimited liability: Legal equality for Swedish banks with alternative shareholder liability regimes, 1897–1903. Business History Review, 95(2), 193–218. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680521000192

- La Croix, S. J. (1992). Property rights and institutional change during Australia’s gold rush. Explorations in Economic History, 29(2), 204–227. https://doi.org/10.1016/0014-4983(92)90011-K

- Lipton, P. (2007). A history of company law in colonial Australia: Economic development and legal evolution. Melbourne University Law Review, 31, 805–836.

- Lipton, P. (2018). The introduction of limited liability into the English and Australian Colonial Companies Acts: Inevitable progression or chaotic history?. Melbourne University Law Review, 41(3), 1278–1323.

- Maddock, R., & McLean, I. (1984). Supply-side shocks: The case of Australian gold. The Journal of Economic History, 44(4), 1047–1067. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022050700033088

- Madsen, J. (2015). Australian economic growth and its drivers since European settlement. In S. Ville & G. Withers (Eds.), The Cambridge economic history of Australia. Cambridge University Press.

- McLean, I. W. (2013). Why Australia prospered: The shifting sources of economic growth. Princeton University Press.

- McQueen, R. (1991). Limited liability company legislation – The Australian experience. Australian Journal of Corporate Law, 22, 22–54.

- Merrett, D. T. (1997). Capital markets and capital formation in Australia, 1890–1945. Australian Economic History Review, 37(3), 181–201.

- Merrett, D. T., & Seltzer, A. (2000). Work in the financial services industry and worker monitoring: A study of the Union Bank of Australia in the 1920s. Business History, 42(3), 133–152. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790000000270

- Merrett, D. T., & Ville, S. (2009). Financing growth: New issues by Australian firms, 1920–1939. Business History Review, 83(3), 563–589. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680500003007

- Morris, R. D. (1997). The origins of the no-liability mining company and its accounting regulations. In T. E. Cooke & C. W. Nobes (Eds.), The development of accounting in an international context. A Festschrift in honour of R. H. Parker (pp. 90–121). Routledge.

- Musacchio, A., & Turner, J. D. (2013). Does the law and finance hypothesis pass the test of history? Business History, 55(4), 524–542. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.741976

- Oskar, G. (2023). Assessable stock and the Comstock mining companies. Business History, 65(1), 157–185. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2020.1807951

- Panza, L., & Williamson, J. G. (2019). Australian squatters, convicts and capitalists: Dividing up a fast-growing fronter pie 1821-1871. The Economic History Review, 72(2), 568–594. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.12739

- Quinn, W., & Turner, J. D. (2020). Boom and bust: A global history of financial bubbles. Cambridge University Press.

- Rickard, J. (2017). Australia: A cultural history (3rd ed.). Monash University Publishing.

- Salsbury, S., & Sweeney, K. (1988). The bull, the bear and the kangaroo: The history of the Sydney Stock Exchange. Allen & Unwin.

- Turner, J. D. (2009). Wider share ownership? Investors in English and Welsh bank shares in the nineteenth century. The Economic History Review, 62(s1), 167–192. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2009.00477.x

- Van den Broek, D. (2011). Strapping as well as numerate: Occupational identity, masculinity and the aesthetic of nineteenth-century banking. Business History, 53(3), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2011.565509

- Van Leeuwen, M. H. D., Maas, I., & Miles, A. (2004). Creating a historical international standard classification of occupations: An exercise in multinational interdisciplinary cooperation. Historical Methods, 37(4), 186–197. https://doi.org/10.3200/HMTS.37.4.186-197

- Ville, S. (1998). Business development in colonial Australia. Australian Economic History Review, 38(1), 16–41. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8446.00023

- Ville, S., & Merrett, D. (2020). Investing in a successful resource-based colonial economy: International business in Australia before World War One. Business History Review, 94(2), 321–346. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680520000264

- Ville, S., & Wicken, O. (2013). The dynamics of resource-based economic development: Evidence from Australia and Norway. Industrial and Corporate Change, 22(5), 1341–1371. https://doi.org/10.1093/icc/dts040

- Waugh, J. C. (1987). No liability companies in Victoria. Australian Mining and Petroleum Law Association Yearbook, 6, 30–53.

Appendix

Table A1. Definitions of variables.

Table A2. Definitions of occupational groups.