Abstract

This article analyzes an unexplored register of Spanish banks’ marketing material to document the access of women to the retail banking sector. In 1949 the Franco dictatorship deployed a Censorship Bureau to supervise all retail bank marketing. Initially this office was part of the Finance Ministry but in 1962 it was relocated to the Central Bank. Examination of this printed material allowed us to map a shift in bank strategies towards large-scale consumer banking, which we labelled ‘bankarization’. We identified three stages in this shift: (1) women appeared as passive clients; (2) steps taken by the banks to attract women as active customers, (3) the banks actively engaged in the recruitment of female customers. This research contributes to the history of marketing and the business history of banking, and sheds light on the intricate connection of the feminisation of retail banking.

Introduction

Women entered Spanish banks during the twentieth century in increasing numbers, as customers and as employees.Footnote1 Significant attention has been placed on the understanding of women as staff of retail finance organisations (McKinlay, Citation2002, Citation2013; Wardley, Citation2011), the role of women employees in the process of bank automation (Crowley, Citation2012; Heller, Citation2008; Heller & Kamleitner, Citation2014) and more recently, the role of women in the creation of modern-style banks for women (Garrett-Scott, Citation2019; Wang, Citation2022). Little consideration, however, has been given to when and how retail banks recognised the significance of females as mass customers and the role of the marital licence (i.e. written approval by husbands or fathers) in that process. This article will argue, with supporting archival evidence, that the process of attracting women, and married women in particular, to retail finance was an essential part of consumer culture and modernity, as such this was the bedrock to the bankarization of everyday life which characterised the late twentieth century.Footnote2

In the decades after the Civil War, the Spanish banking system operated with diverse structures and corporate governance regimes (Bátiz-Lazo, Citation2004; Martín Aceña, Citation2012).Footnote3 One was a cartel of commercial banks which aligned its business objectives to those of Franco’s dictatorship (Sánchez, Citation2003). By 1960, commercial banks held 70.2% of all retail deposits in Spain (García Ruiz, Citation2017, p. 73). The same year, the top five commercial banks in the country (Banco Central, Banco Español de Crédito, Banco Hispano Americano, Banco de Vizcaya and Banco de Bilbao) had a 58.24% share of all deposits, while 22 banks at a national or regional level held more than 98% of the retail deposit market (De Inclán et al. Citation2019, p. 29). However, regulatory reforms introduced in 1962 led to the reorganisation of the industry and an intensified competition between commercial banks and savings banks for retail deposits (Fernández Sánchez, Citation2023; Maixé-Altés, Citation2022). Targeting the emergent middle-class and professional women as customers, some of which had been long-standing customers of savings banks, can thus not only be seen as a move to create a new market share but also as a competitive response by commercial banks to environmental turbulence.

This paper traces when and how women became targets of bank advertisements and the institutions which pioneered this development. The research taps into a previously unexplored source to offer graphic analysis from a gender perspective which maps the emergence of the female customer as revealed by the marketing campaigns undertaken by the commercial banks. The source material encompassed what we have termed the Bank Censorship Bureau (described in detail further below and in Appendix A), that is, surviving advert submissions, made by commercial banks, for regulatory approval between 1949 and 1970.

The analysis of bank advertisements suggested an evolution in the interaction between banks and their female customers. This evolution was nonlinear, and trends were not universal to all bank advertising and some, particularly those with male voices, remained long after the period of study. We grouped this evolution into three stages. Initially, bank advertising was characterised by an institutional image and often exhibited the bank’s headquarters or a photograph of one of the bank’s buildings (Barnes & Newton, Citation2017, Citation2018, Citation2022a; Schroeder, Citation2003). Within this stage our attention was drawn to the 1950s, when women began to appear as extras, filling space within the advert but, at the same time, reflect a reality of the increased visibility of women in Spanish society. The second stage coincided with a product diversification strategy by the commercial banks, when they sought to offer a wider range of services to their existing customers including women (Bonin, Citation2014; Vetter, Citation2022). At the end of the 1960s, a third stage marks a turning point when women appear for the first time as protagonists and main targets of bank advertising campaigns. These adverts introduced a new narrative which sought to connect with a younger, and more independent women and as a novel way to address the increasing visibility of women in the workplace, society at large, and women’s rights.

The article proceeds as follows. The following section frames the research, firstly, by placing the concept of ‘bankarization’ within the broader existing literature. The second section describes the role of women in the blossoming Spanish consumer society in the post-war period. The third section introduces the main source of analysis (discussed in detail in Appendix A), a corpus of previously unexplored records of petitions and authorizations of adverts which marketed the retail financial services offered by Spanish commercial banks. The analysis of this evidence is dispersed throughout the following three sections as we map three stages in which the banks exhibit their graphic representations of women through their advertising between 1949 and 1970. The final section offers tentative conclusions and considers how the research in this article helps to broaden the discussion of gender within retail finance during the late twentieth century.

Bankarization and the emergence of women in the Spanish consumer society

Bankarization

Francois, McLaughlin and Pecchenino and Samy are among those who have documented, from an historical perspective, how individuals interacted with financial and non-financial firms to access retail financial markets throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries while exploring issues of class and the availability of services and credit (Francois, Citation2006; McLaughlin & Pecchenino, Citation2021; Samy, Citation2012). There is also a strand of research from a political economy perspective, such as that of Bernards and Langley, which presents an alternative view of bankarization (i.e. the access and routine use of ordinary financial services) not unique to the twentieth century but as a continuation of a process of colonialism and the logic of neoliberalism (Bernards, Citation2022; Langley, Citation2008). Together these contributions portray access to retail financial services as integral to modern day capitalism.

In this regard, Ossandón argues that an analysis of people’s ‘daily’ finances or a category which considers the interaction of financial services and social ties, enables a better understanding of the links between financial inclusion and exclusion (Ossandón, Citation2014). According to Rouse, the term ‘financial exclusion’ is rooted in policies and regulation enacted by the administration of President Lyndon B. Johnson (1963–1969) which addressed equal rights access to retail banking (Rouse, Citation2020). Furthermore, this is popularised in the financial literature during the early 1990s mainly due to concerns about the limited financial services resulting from the closure of many bank branches (European Commission, Citation2008).Footnote4 The notion was centred initially on exclusion from financial services due to lack of access to formal bank accounts and the proximity of bank branches. Subsequently, the concept of financial exclusion was broadened to consider a number of factors (Kempson et al. Citation2000). The term ‘financial inclusion’ emerged in the early 2000s and has been used to denote ways of addressing financial exclusion or to the process of purposefully facilitating access to formal financial services (World Bank, Citation2019). These views were not universal, however.

Our aim in this article is not to settle a debate as to the origins and meaning of bankarization.Footnote5 Instead, this article considers the analysis of adverts by Spanish commercial banks in the printed media, to map how these institutions brought women into the realm of ordinary and daily finances (in the form of access to personal cheques, savings accounts, traveler’s cheques and direct debit payment of bills). The enquiry is relevant and timely because a combination of regulation, wealth, and social usages meant that until the 1960s, retail banking was strictly a business of men, for men, by men. Women, and particularly married women, were excluded as customers. Some northern European countries, such as Sweden, solved this limitation in the 1920s (Husz, Citation2023). But broadly speaking, these barriers slowly came down in Western societies between 1960 and 1975, as was the case in The Netherlands (1957), Germany (1958), France (1965), Luxemburg (1972) and the USA (finally resolved in 1974 with the Equal Credit Opportunity Act).

The impact on retail banking of regulatory innovations which put an end to the marital licence were first noted in the analysis of Société Générale’s advertising by Bonin (Bonin, Citation2014). He identified how the emergence of commodity financial services and massification of retail finance in the 1960s included the diversification of French banks aimed specifically at women customers (Effosse, Citation2017; Vetter, Citation2022). This was followed by the pioneering contributions that analyse changes in the French (Effosse, Citation2021) and Italian (De Rosa, Citation2021) legal frameworks. These studies explored the extensive journey towards abolishing the requirement for married women to obtain their husband’s consent to open a bank account. This historical shift ultimately piqued the interest of retail financial institutions, prompting them to target married women as a direct customer base in the 1960s. The evidence supported the idea that households in Sweden became more involved in banking, and this shift was attributed to regulatory changes, societal shifts, and the business strategies of local retail financial institutions during the 1960s (Husz, Citation2015). Furthermore, Husz suggested a close connection between the entry of scores of women into the retail banking markets, the growth of the welfare state, and the emergence of a modern, consumer society (Husz, Citation2015; Husz & Bouyssou, Citation2015). Related to the above, there is a solid literature that analyzes the relationship between gender and finance. Particularly fertile have been the studies on women investors in the stock market initiated by Ruttterford and Maltby (Rutterford & Maltby, Citation2006).

Regarding the state of the art in Spain, only a handful of contributions analyse how aspects of the consumer society intertwined with women’s lives within retail banking (Martínez-Rodríguez, Citation2021, Citation2023; Martínez-Rodríguez & Lopez-Gomez, Citation2023). The aforementioned studies suggested gendered differences in the incorporation of men and women in retail bank markets as part of the diversification strategies of commercial banks. However, the same sources do not analyse this topic in sufficient depth. Furthermore, these sources are mute on how the inclusion of women is part of broader trends such as modernity or correlated with the economic development model of the 1960s, because until then the level of income in Spain had been insufficient to maintain, say, a durable consumer goods market.

Role of women in the Spanish consumer society

The dictatorial, Catholic, Fascist regime established at the end of the civil war in 1939, resulted in Spanish women losing several freedoms and rights. For instance, a fundamental piece of legislation for the regime, the ‘Fuero del Trabajo’ (Labour Code), prohibited the employment of married women in working class jobs within workshops and factories (BOE, Citation1938). Repression affected all strata of society. Several provisions in the following years restricted women’s access to certain positions in the administration and their career advancement. For example, in 1944, women were forbidden to act as notaries, or become part of the corps of registrars and the secretariat of public administrations (BOE, Citation1944).

However, growth of the employment of women within the service sector and public administration led to a legislative milestone in 1961, when labour rights were extended to all women in the labour market.Footnote6 Although the law in 1961 and other provisions allowed women to regain some of the public spaces they enjoyed before 1936, these regulatory innovations were driven by the growing numbers of women in the labour force rather than a desire for egalitarianism. Indeed, the political and ideological regime, while increasingly more open to women working or training, did not question the principle of male authority within the home (Valiente, Citation2003).

The creation of employment during the 1960s meant women exceeded one million participants in the workforce, with 10 out of every 12 new jobs being filled by women. In 1964 (the first year for which the labour force survey was available) women accrued 8.47% of the total labour force (INE, Citation1965, pp. 127–128). In 1968 they represented 23.7% (INE, Citation1969b, p. 71). This growth also associated with an increase in real wages and longer working hours. Together they paved the way for a process of economic development which favoured private consumption (De Dios Fernández, Citation2022). As the twentieth century progressed so did the importance of women, and particularly married women, at the centre of purchasing decisions on both sides of the Atlantic (Fox, Citation1984; Rodríguez Martín, Citation2021). This resulted in a new model of the ‘modern’ housewife that emerged in the printed press, depicted a series of new behaviours to reflect reality and at the same time aimed to influence the behaviour of female readers (Rivière, Citation1977).

The growth of the consumer society in Spain coincided with an expansion of retail banking as the number of retail branches tripled from 2,505 in 1960 to 7,539 in 1975 (De Inclán et al. Citation2019). This expansion was part of a banking reform introduced in 1962 (see below) but which called for greater number of customers as end-users of the retail bank branch. This meant that it was no longer enough for a woman to be a bank customer through her husband. She needed to be an active client.

Archives of the bank censorship bureau

Following the enactment of the ‘Ley de Prensa’ (Press Law, 22 April 1938) and until the mid-1960s, the repressive and official censorship apparatus tightly controlled all media and advertising. With the passing of the ‘Estatuto de publicidad’ (Advertising Statute) in 1964 and these restrictions somewhat relaxed with the enactment of a new regulation of the press and printed media enacted in 1966 (BOE, Citation1966). Although this was delayed in respect to what the society and industry demanded. By 1966, a dozen American advertising agencies had been established in Spain (Montero, Citation2012), and mass financial and non-financial advertising was mainly distributed through newspapers and magazines (Rodríguez Martín, Citation2021).

Advertisements by commercial banks, however, were subject to ad hoc regulation with the passing of the Ministerial Order of 4 May 1949. This Order was introduced by the Ministry of Finance to fill what was perceived to be a gap left by previous legislation, namely the Insurance Laws (1908, 1912) and Article 38 of the Banking Law (1946). The latter permitted the use of the terms ‘bank’ or ‘banker’ only by those organisations officially recognised in the Registry of Banks and Bankers.Footnote7 Hence the censorship of commercial banking advertising was born.

Documentation relating to the censorship of bank advertising survived within the ‘Archivo Histórico del Banco de España’ (The Bank of Spain Historical Archive Service, henceforth AHBE). This was a previously unexplored archival source. Its contents consist of records generated by different ministerial offices with a mandate to scrutinise advertising by banks which operated in Spain. Thus, different administrative units were responsible for authorising publicity emanating from the commercial banks and keeping track of the previous authorizations.

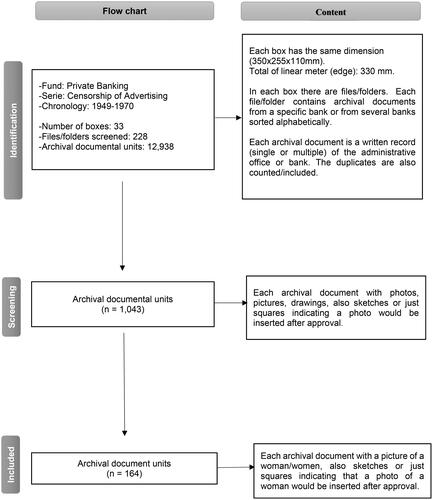

We termed this amalgam the Bank Censorship Bureau and it became the corpus of the research. The contents include the requests for new advertisements by commercial banks predominantly produced for the written press, dated from the creation of the Bank Censorship Bureau in 1949. This enabled the exploration of the treatment of women, in graphics, as bank customers and how it evolved. By focusing on advertisements by commercial banks and particularly those related to marketing and publicity containing a woman or any female graphic motif the exploration mapped: ads in which women appear as mere extras, to those in which women were the central focus in advertising campaigns. The period of analysis ends in 1970 because, as we detail below, we observed a point of inflection which deserves an analysis of its own. summarises the process to tally of all the surviving documents in the Bank Censorship Bureau. All contents were counted, none were excluded, although there were repetitions and duplications (the reasons for which were unclear). The documentation was spread across 33 archive boxes, containing a total of 228 files. A total of 12,938 document units were identified. The documental units with a picture or an indication that a picture would later be included were 1,043. A total of 164 documents fulfilled the inclusion criteria of being a document with a picture of a woman. Appendix A provides more detail on the contents and the selection process.

Figure 1. Flow chart for the selection of archival material. Source: Own elaboration based on the Fund Private Banking of AHBE (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023a). Note: The selection process was performed manually following the taxonomy of Consejo Internacional de Archivos – ISAD(G) (BOE, Citation2011; Consejo Internacional de Archivos-ISAD (G), 2000).

First stage: women as part of the picture

As mentioned above, conceptualising the evolution of bank advertising aimed at women in three stages was a construction of the research, because the reality was quite diffuse, woolly, and imprecise. This first stage represents the beginning of the process of constructing a narrative created around women as clientele of commercial banking.

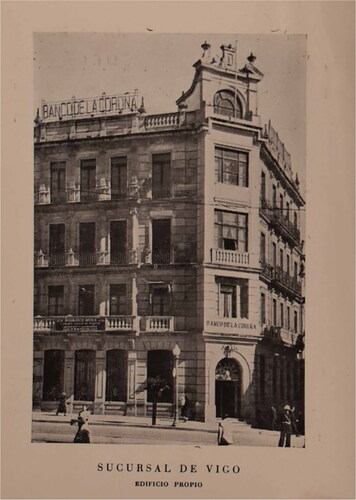

Most of the adverts with images within the holdings of the Bank Censorship Bureau in the 1950s and early 1960s offer an illustration of the bank’s main headquarters or use the images to inform of a new branch in a major city.Footnote8 Human figures in these adverts appeared as part of the decor. One could easily assume that their purpose was to give a sense of movement and activity to the city streets where the advert located.

illustrates how the women found in these advertisements appeared as an accidental, random occurrence more like a margin annotation or a passer-by rather than central targets of publicity. In this case, the three women pedestrians appeared in the left-hand side of the image. Some were even about to enter the bank, but they were all relegated to parts of the scenery of the urban landscape as ‘extras’, clearly reflecting an urban environment which began to characterise the everyday life of a growing number of Spaniards.Footnote9

Figure 2. Women walking in the street in the northern city of vigo in front of Banco de La Coruña. Source: AHBE-BP. 182 Banco de La Coruña: application to the BE dated 29 April 1951 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023b).

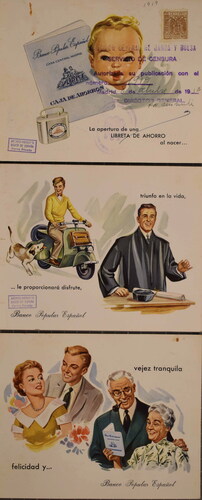

depicts another common type of advertisement in which women appear during this first stage. The advert appeals to homelife while depicting women in traditional roles.Footnote10 In a similar vein, we also found adverts in which the bank wanted to associate its name with a regional festival or specific celebration where women were shown in regional dress. For instance, a silhouette of a flamenco dancer appears for the Seville fair or as a ‘chulapa’ for the festivities in Madrid.Footnote11 Women were not addressed explicitly in the text in neither occurrence.

Figure 3. Women are depicted in traditional roles but ignored in the advert’s text. Source: AHBE-BP.187 Banco Popular Español: authorisation to publish a new add from the BE, date of the reply 8 October 1956 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023b).

Other banks depicted more conventional realities. In 1960, Banco Castellano presented advertising with pictures of a real retail bank branch office (as opposed to a picture of an idealised environment in a studio-designed set-up), where all the staff were men.Footnote12 Along the same lines, Banco Popular Español characterised its clientele in detail in 1966 and did not include a single woman.Footnote13 The dates of this form of traditional, masculine advertising suggested it persisted long after that when women began to take space in the adds. Indeed, the shift to include women as customers was thus far from universal, even disruptive.

Second stage: a new type of customer emerged

Women appear on the banking scene

A second stage in the graphical analysis of bank advertising took place from 1960s and marked the banks’ interest in including women as new customers. Several commercial banks presented advertising campaigns that, for the first time, featured women as customers. These adverts appeared promoting a set of well-established products and services namely, personal loans, credits, family savings accounts, and personal cheques. They all adopted the image of women as users, thus suggesting purposeful efforts to bankarize large scores of female customers, but (implicitly or even explicitly) portray women as still dependent on male figures. No significant milestone could be identified to mark the beginning of this trend.

Although the massive expansion of personal sector credit and large advertising expenditure took place until the mid-1970s and 1980s (Maixé-Altés, Citation2022), early advertising of commercial Spanish banks benefitted from pioneering efforts in the health, food, personal hygiene, leisure and automotive sectors (Rodríguez Martín, Citation2021; Rodríguez Martín & Miras, Citation2021). Marketing in the early to mid-twentieth century tailored products and services to women’s ‘needs’ (Maclaran, Citation2012), so banks’ advertisements drew on marketing strategies already being implemented elsewhere. Products targeted at women had traits typified as feminine such as simplicity and convenience. Financial advertising aimed at women was often tinged with a jovial tone, more childish than the same advertisement aimed at a general and implicitly masculine audience. In addition, the content was also usually lighter and less technical (Santa Cruz & Erazo, Citation1980).

As the 1960s progressed, advertising which targeted women began to appear as part of the overall scene, but none as sole protagonists. This trend in advertising Spanish banks was similar to that identified by Bonin (Citation2014) in France and in Germany and Luxemburg by Vetter (Citation2022). The adverts aimed to increase the adoption of well-established banking products and services, in which there was no innovation.

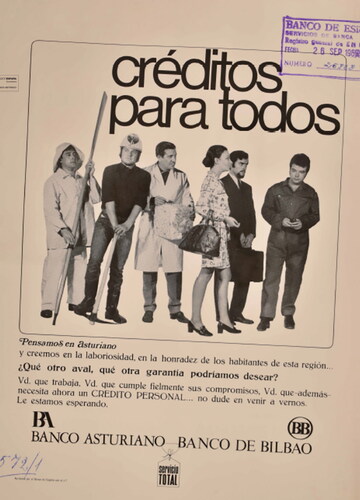

Spanish commercial banks initially introduced female images in the adverts to create more varied customer profiles and included a non-descript female figure alongside a group of clearly identifiable male customers (see ). Men were typified by their profession: a farmer, a blue-collar worker, an office worker, and businessman.Footnote14 The characterisation of male professionals sometimes evocates the economic traits linked to the area where the bank is located, for instance, a customer such as a fisherman or sailor in the ads of Banco de La CoruñaFootnote15, or a miner in the case of the Banco Asturiano.Footnote16

Figure 4. ‘Loans for everyone’. Source: AHBE-BP. 1012 Banco Asturiano-Banco Bilbao reply from BE 22 September 1969 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023b).

In these advertisements, women were characterised in casual rather than professional attire. No feature of their clothing betrayed their activity. In there is a single woman among a group of men, which further emphasises her presence. As in this case, the woman in most adverts tended to be young, slim and fashionably dressed, which also pointed to an urban life. Advertisements seemed to transmit the idea that women went to the bank to carry out an everyday task (such as paying a bill or withdrawing cash).Footnote17 The target profile was not a high-income customer, nor a professional who needed financial advice, but the middle and lower socio-economic groups who required new services to make her life simpler or more pleasant. Women in adverts were depicted in leisure, family or study locations.Footnote18 Some banks, in characterising their clientele, introduced female archetypes: elderly lady and pensioner, a mother with a child, or as one of a couple visiting the branch.Footnote19 Meanwhile, other banks continued to target solely a male audience, albeit diverse, but with no reference to women.Footnote20

Most of the women were shown as part of the family unit supporting their husbands’ decision. The Population Census of 1960 classified as housewives 67.67% of the total number of women (13,253,498). The Census defined them as a non-active and dependent population. The exact category was “women - their work,” and no male equivalent existed (that is, there were no male homemaker) (INE, Citation1969a).

Before the amendment of the Civil Code in 1975 (BOE, Citation1975), housewives had no legal capability to make their own decisions concerning their finances without their husbands’ express and written authorisation. But at the same time, they were the main decision makers of home consumption (including large expenditure such as white goods or refurbishments).

There is no reference with the adverts regarding the risk of default, affordability, or over-indebtedness, nor access to large organised financial markets through the purchase of stocks or investment funds. The concepts highlighted in the adverts thus emphasised the economic well-being and the bankarization of a growing and affluent middle class.

Another relevant phenomenon in the 1960s is associated with changes in the employment structure of banks where women were increasingly active as clerical workers. The entry of women into the non-housework service sector is a multi-faceted phenomenon, related to the automation of tasks, for which women were brought into the workforce by banks seeking to lower wage costs (Wardley, Citation2000, Citation2011).

The employment of women as tellers behind the counter of a retail bank branch was a transformation of female roles as they were moved from the back office to face the customer directly, a role they played with more friendliness than that of men in the same position. Advertising played its part in the new framework: bank marketing departments and external advertising agencies translated the dictates of a bank that wanted to incorporate women as customers while increasingly hiring women as bank agents, visible at the main point of contact with customers. An example of this transformation was found in an advertisement dated 1969 by Banco del Norte. They launched a campaign aimed at professional business profiles and male managers with the slogan ‘Our management has 117,000 trustworthy men’.Footnote21 The language uses the universal masculine voice, although, as the picture illustrating the advertisement shows, there were female customers and women working at the branch.

The family savings account

A fair number of adverts relate to family-life products such as the home savings account or children’s savings accounts. The imagery appeals to the nuclear family as the keystone of society but with a twist. For instance, a recurrent image around the home savings account was that of a pair of newlyweds whose gestures betrayed their excitement at the start of a life together.Footnote22 This was consistent with a significant increase in new homes built during the 1960s. This increase was promoted by a combination of economic growth, increased population and government policy (BOE, Citation1961b). Acquiring a personal dwelling became an image of modernity, evoking urban aspirations, with similar financing facilities non-existent in rural areas. It also appealed to a new formula which saw the introduction of down payments – accumulated through a savings account – as a first step to formalising a mortgage with the same bank. The ads often implied that the wife, regardless of her employment situation, would be responsible for the management of repayments. But no reference was made to the risk of losing the dwelling as a result of defaulting on the loan.

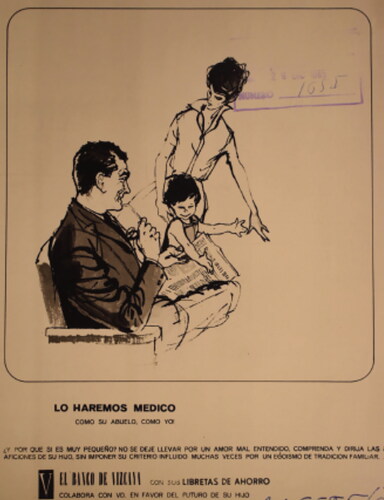

The imagery and text seem to suggest that once married the bank would accompany newlyweds for life. We highlight two variants of the discourse. The first one evoked the children’s future well-being. Here, and even though the wife appeared on the scene, the narrator solely addressed the father: as the figurehead, main source of authority, and role model. One advert read:

He wants to be like you. You are an example for your son; your son looks up to you and wants to be like you. Gain his confidence again and again, favor his vocation, give him the hopeful and bright future that he deserves as your son. He will not disappoint you. The Banco de Vizcaya with its savings accounts collaborates with you in favor of your son’s future.Footnote23

Figure 5. ‘He wants to be like you’. Source: AHBE-BP. 994 Banco Vizcaya: request addressed to the Banco de Vizcaya dated 29 December 1965 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023b).

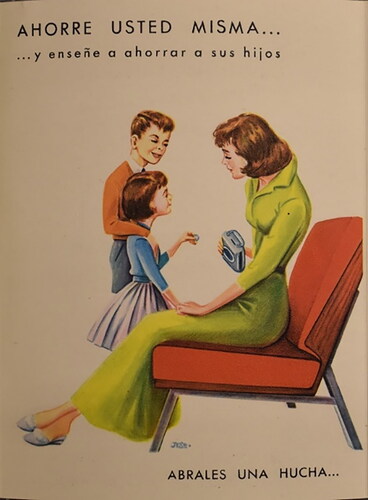

The second variant of this narrative emphasised the mother as a role model, teaching her children how to save.Footnote25 She is entrusted with the obligation to inculcate the value of saving and foresight (): ‘Save for yourself… and teach your children to save. Open a piggy bank for them… visit us, you will see the efficiency of our savings bank services’.Footnote26

Figure 6. ‘Teach your children to save’. Source: AHBE-BP. 1130 Banco Popular Español: request to the BE, date of reply 28 March 1960 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Bátiz-Lazo, Citation2023b).

Stereotypes and gender biases were also found in the cultural interpretation of the role of boys and girls. For instance, when opening a savings account children received a gift – reading books – from the Banco de Vizcaya, the boy’s gesture was to extend his arms with the symbol of victory, while the girl gathered her hands as a sign of gratitude.Footnote27 The bank’s expectations were not to drive change within society through its advertising, rather, to articulate and graphically represent its values.

Personal loans, current accounts and travellers cheques

In the case of personal credit, the advert which we considered to be the most innovative followed the slogan that credit was a product open to all, and this ‘all’ included women.Footnote28 The bank appeals to the personal reputation of the individual in order to obtain a loan: ‘Loans for everyone […] You who work, you who faithfully fulfil your commitments, you who… also… need a personal loan… don’t hesitate to come and see us. We are waiting for you now’.Footnote29

The text called for the target audience to become a customer of the bank and made no reference to the consequences of lack of payment. Perhaps implicit was the idea that, in the absence of formal credit scoring techniques, one would not risk defaulting and losing one’s hard-won reputation. Within the text, there was a suggestion that the reader might infer that women had access to personal credit, and that the bank offered them information on these services. But what of the consequences of advancing these funds? Granting the loan was subject, as the advertisement said, to a personal guarantee, and this was embodied in the authorisation of the husband for married women. Here it is worth noting that, although we have tried, data protection and archive closure prevented statistical examination of the volume and value of personal loans to women during this period. Along the same lines we found an advertising campaign by Banco Español de Crédito dated 1961, which offered ‘credits to students with a technical education’.Footnote30 The inside of the leaflet specified the target audience of this product, although in the graphic design the presence of female students was evident.

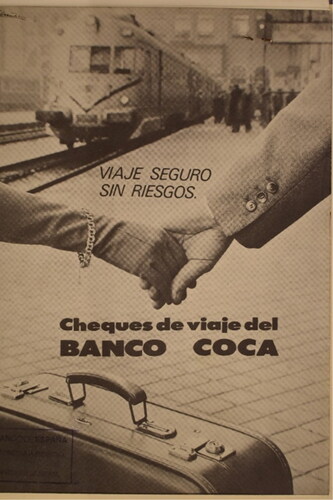

Women also increasingly appear in adverts promoting the use of personal cheques. Adverts which associate the idea of convenience with both travellers cheques and current accounts. Although already popular in the USA, Canada and France (Bonin, Citation2014), in the 1960s, bank marketing efforts promoted greater use of a new payment method for Spain: the personal cheque (Maixé-Altés, Citation2022). Personal cheques and cheque guarantee cards never really took off in Spain (Batiz-Lazo & Del Angel, Citation2018). Nonetheless, during their introduction they were advertised while pivoting their convenience, multiple purpose applications, security, versatility (relevant for leisure or work situations) and, through Eurocheque or currency denominated travellers cheques, able to withdraw funds abroad (Vetter, Citation2022).

Although adverts clearly differentiated between personal cheques and travellers cheques as two distinct products, emphasising convenience within leisure activities was a friendly way of conveying that the products were easy to use. In the case of travellers cheques, the most usual advertising scene depicted a couple, with or without children, in a leisure setting. This sort of advertising evoked a holiday travel situation, aimed at an affluent familyFootnote31 or a newly married couple as in below.Footnote32

Figure 7. ‘Safe and secure travel’. Source: AHBE-BP. 992 Banco Coca: request sent to BE, 5 July 1966 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023b)

Security was a second feature often highlighted around travellers cheques. For instance, Banco Santander advertised travellers cheques while choosing the unusual figure of a well-to-do woman travelling alone as the main character in 1961. The ad read: ‘Avoid the risk of theft when travelling by using our travellers cheques’.Footnote33 There were similar ads depicting scenarios where a male actor consumed the same product while emphasising signs of class identity and comfort in daily transactions; and security in leisure or business trips.Footnote34

To illustrate the promotion of current accounts and personal cheques, we highlight a campaign launched in 1965 by Banco de Bilbao which specifically addressed women with the slogan: ‘we all pay with cheques from the Banco de Bilbao, it is so convenient!’.Footnote35 A woman filling in or signing a personal cheque dominated the scene, evoking an everyday act: going to the retail bank branch and signing a cheque to complete a transaction. Convenience was again the central message.

Third stage: women as main protagonists in advertising campaigns

Loans for her (and her husband)

Towards the end of the 1960s there was a significant break with the past as some commercial banks launched campaigns aimed exclusively at female customers. This change anticipated the reform of 1975, which abolished the marital licence, by virtue of reform of the Civil Code, enabling married women to open a current account, take out a personal loan or credit card without a husband’s consent (BOE, Citation1975). An international development that may have influenced Spanish banking was the elimination of a similar principle to marital licence elsewhere in Europe during the early 1960s and particularly in France in 1965.

Between 1967 and 1969, several banks introduced advertisements featuring women. They were no longer companions but the main – and even only – protagonists. These campaigns went a step further to address customers with different profiles. However, surviving evidence leaves no doubt that it was the then medium-sized, regional banks, second to the largest commercial banks (in terms of total assets and retail branches) which launched nationwide campaigns to attract female customers. In fact, it was the banks whose origins and head offices were in the North-East of Spain: Santander, Bilbao, and Vizcaya.

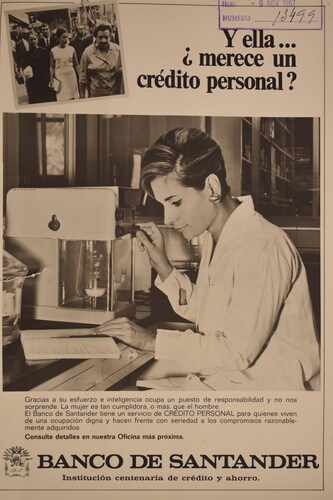

Banco Santander launched a campaign to advertise personal loans in 1967. The marketing campaign had the slogan: ‘Do you deserve a personal loan?’. The campaign in printed media included three advertisements starring a mechanic, a housewife, and a woman laboratory technician. A fourth image consisted of a photograph taken at a pedestrian crossing in a big city, where the presence of ‘fashionista’ women was central to the scene.

The middle-aged housewife was a stereotype often situated her in the kitchen cooking. In the Santander advert, she dominated the graphic scene but plays a secondary role in the text. The latter informs that the loan would be for her and her husband: ‘Does her and her husband deserve a personal loan? She has everything clean tidy. Her selflessness and her tidiness watch over her husband, who has gone to work. Today they can both think of prudent home improvements. For those who live from a dignified occupation and seriously confront their reasonably acquired commitments, […] there is our personal credit service’.Footnote36

The image of the female laboratory technician was the most striking advert as it clearly appealed to the young female professional. The text highlighted the values of a new generation of independent and educated women: ‘Thanks to her effort and intelligence, she is in a position of responsibility, and we are not surprised. Women are just as, if not more, dutiful than men. Banco de Santander has a personal credit service for those who make a decent living and are serious about meeting their reasonable commitments’.Footnote37

Thus far, this was the first advertisement unambiguously aimed at a professional woman: a young, qualified female in the biomedical field ().Footnote38 It is also one of the few adverts which warned of the requirement to meet financial obligations, but not of the consequences of default or over indebtedness.

Figure 8. ‘And she… does she deserve a personal credit?’. Source: AHBE-BP. 1008 Banco de Santander sent to the BE reply from the BE 30 October 1967 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023b).

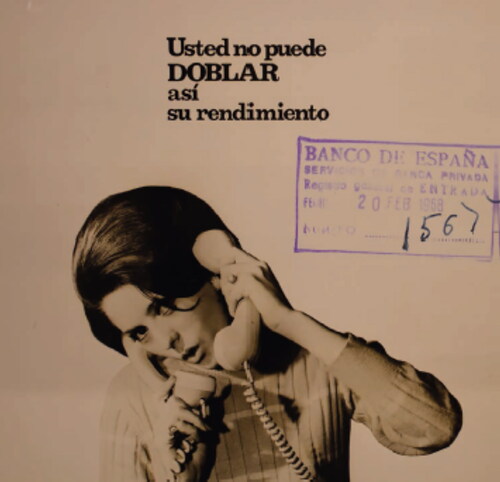

In a similar vein, Banco de Vizcaya launched an advertisement promoting savings and life insurance in 1968. Individual adverts depicted a gentleman, a female secretary, a housewife, a female typist, and a picture of generic hands depositing money on a table.Footnote39 Three out of these five profiles were females and two of them were characterised as young women with professional careers. The bank’s slogan underlining the pictures was: ‘The bank that serves everyone’. All women are depicted within a labour market setting. In the adverts the housewife appeared as a young slim woman, performing housework (ironing and cooking).Footnote40 The secretary was on the telephone (). The typist was using a typewriter and a calculating machine. It is worth highlighting that in the case of the adverts depicting the secretary and the typist, the narrative explicitly appealed to the benefits of saving part of their salaries. The significant presence of women in the service sector had a noteworthy impact on clerical work (such as offices, banking, and commerce) (Cabrera Pérez, Citation2005, p. 193).

Figure 9. ‘You cannot double your performance’. Source: AHBE-BP. 1009 Banco de Vizcaya reply from the Banco de Vizcaya, 27 February 1968 (Martínez-Rodríguez & Batiz-Lazo, Citation2023b).

In 1969, Banco de Vizcaya launched a new campaign targeting four customer profiles: a male student of higher education, a white collar, male employee, a mother with a small child (presumably a housewife), and an elderly female pensioner. The housewife was described as ‘motherly, feminine, kind’, and depicted filling out a personal cheque. The bank seemed to have broader aims than simply selling current accounts as is evident when taken into consideration that she was depicted using other services namely, the payment of bills and utilities. The advert emphasised the convenience of these services for her.

In another version of that advert, the media featured an old woman collecting a pension. Her attributes noted in the script were ‘old, worn out, [and] graceful’. Other banks had used the character of the old lady pensioner before, but as an example of the broader population. This was to change in 1967. The advert coincided with the introduction of a universal pension system in 1967. Banco de Vizcaya was clearly responding by targeting female pensioners as a new customer group.Footnote41

Both depictions of women, the pensioner, and the middle-aged housewife, were attractive to the bank because of their potential to redirect household spending and increase transaction volume at retail bank branches. Although as individuals they could be ‘modest’ users, their profile matched that of millions of potential customers throughout Spain. The bank highlighted these attributes when the woman said: ‘I have been told that small accounts like mine are very important’.Footnote42

In 1969, Banco de Santander launched a campaign promoting personal loans entitled: ‘You need a boost’. The campaign portrayed the figure of two female housewives from distinct socio-economic backgrounds. One is characterised as a member of the working class; the other seems to belong to a higher economic stratum and she was portrayed doing errands at the bank. The narration appeals to both women as the mainstay of the family economy, revaluating the contribution of housework ‘because, with her work and seriousness, she helps to meet reasonably acquired commitments’.Footnote43 The socioeconomic sector delineated distinct realities for each homemaker. Although only 11% of households hired full-time live-in domestic service, approximately one million homes engaged in domestic services hourly (Fundación FOESSA, Citation1970, p. 1064). Within the lower socioeconomic strata, 12% of the women identified themselves as housewives were employed outside their homes, and 14% undertook market-related chores within their households (Fundación FOESSA, Citation1970, p. 1062).

A bank that cares for women’s rights

In 1968, Banco Peninsular launched a campaign to promote personal loans for home renovation. This campaign enabled an analysis of the motivation behind the advertisement because surviving records regarding this specific campaign were more detailed and in depth than others which were limited to administrative correspondence.

The campaign was focused on a specific geographical area: Madrid. The short graphic novel used as illustration depicted a woman looking to renovate her house. She was the sole protagonist of the story, responsible for assessing the budget, applying for a loan at the bank, and overseeing the management of the loan independently. A single woman or a widow could apply for the loan by herself. However, a married woman was required to acquire her husband’s signature and present his salary as a guarantee for the credit. One version of the advertisement read: ‘María Cristina does her calculations to find out how much the reform would cost her and realises that it would come to about 70,000 pesetas [approximately 13,000 euros in 2020],Footnote44 which she cannot ask her husband for’.Footnote45 The narrative of the bank empowers her by conveying the idea that she had full control to secure and manage the loan, as well as steer the family away from default or over indebtedness.

As part the campaign by Banco Peninsular, the bank sent a personal letter to potential customers. The letter informed that the beneficiary would receive ‘a cheque book for the value of the loan’.Footnote46 This letter also enabled a double layered meaning. On the one hand, the campaign reinforced a woman’s decision to renovate the house (which was a female remit), while placing her as chief protagonist when it came to making financial arrangements, managing the chequebook, and making instalments. All these tasks associated with the adjectives easy and simple (‘See how easy it is?’) (Martínez-Rodríguez, Citation2023). On the other hand, compliant with legislation at the time, the bank’s application form was addressed to the husband. The law required the married woman to have her husband’s authorisation until 1975 (BOE, Citation1975).

In 1969, Banco Bilbao launched an ambitious initiative called the ‘Women’s Campaign’, which included a 10-page long brochure devoted to explaining what the bank could do for women. The campaign was developed by the bank’s own marketing staff, and an up-and-coming young manager, José María Tobar, oversaw the operation (Martínez-Rodríguez, Citation2021). Several images and documents around this campaign survived within the Bank Censorship Bureau. One of them portrays a group of women characterised by outfits associated to professional activities. These women included, first, an urban housewife. Second, a nurse and a secretary, which were both were typically female, socially accepted, and qualified professions. Third, a young woman dressed in overalls and carrying packages, representing a female worker in a warehouse or a factory. And fourth, a woman dressed in a toga representing women’s access to the judicial career, following a legal modification in 1966 (Martínez-Rodríguez, Citation2023). The group of five women broke with all previous aesthetics where advertising represented women alone in a scene or a single woman among a group of men.

The brochure encompassed a compilation of all the products and services that Banco Bilbao offered to women, because ‘almost half of our customers are women’.Footnote47 The didactic spirit of the campaign, teaching women how to use these services and products, was evident in the detailed description of all services. A relevant example related to services linked to a current account. The bank insisted on the advantages of the current account itself: ‘Women in other countries have long since considered this problem [of how to make the payment of all the household expenses] and have happily solved it by opening a current account in a bank’.Footnote48

The way in which the information was presented is relevant. As noted, at the time Spanish married women could not open a current account without a marital licence. Yet, overcoming this hurdle was one of the main objectives of the ‘Women’s Campaign’ (Martínez-Rodríguez, Citation2021). Contents of the brochure reminded readers of other services associated with the account such as personal cheques, while the leaflet explained how to fill-in a cheque. The brochure also informed that payment of bills and utilities through direct debit was another benefit associated with the current account. The leaflet informed this service was free and the only condition to access it was to have a current account.

Another interesting product within the leaflet was called the ‘women’s credit’, a line of credit dedicated exclusively to service female customers. It was advertised as simpler and smaller than a regular loan to help ‘set up a small business, prepare a trousseau, prepare a flat, plan a trip’. The ad spoke to young single women with their own aspirations: to help them settle into their profession, to travel, or to start a new married life.

Other services offered in the brochure included a 5% p.a. interest-bearing home savings account; investment advice and custody of securities; money remittance; and travellers cheques. These services were not novel for the broad (male) population. Their novelty was the dimension of the campaign and the fact that they were presented as products and services aimed specifically at women.

Campaigns aimed exclusively at women by the big banks were quickly replicated by other regional banks within their own geographic scope. For instance, in 1969, Banco Mercantil de Manresa (a local bank in Catalonia) launched a very similar campaign to that of Banco de Bilbao’s ‘Women’s Campaign’ in terms of both aesthetics and nature of the message.Footnote49 In 1970, Banco Atlántico, established in Barcelona, declared its interest in serving female customers: ‘Banco Atlántico is a young bank which works hard to achieve all [our] goals; the easy ones and the difficult ones. It is up to you, woman, to decide whether we are achieving the [goal] of giving you, our service’.Footnote50 These campaigns, explicitly targeting female customers, marked a significant milestone. They symbolised the culmination of a lengthy process in which the banking sector, through its advertising efforts, acknowledged the crucial role of gender in bankarization. The campaigns, aimed at attracting female customers, highlighted the correlation between the growth - or widespread adoption - of banking services and gender.

Conclusions

This article documented the beginning of a new phase in the financial history of Spain as commercial banks began to employ strategies designed to attract large groups of customers. This stage of development involved a process that saw the commoditization of retail finance and the massification of banking (Bonin, Citation2014; Maixé-Altés, Citation2022). We showed how bankarization appeared as banks not only promoted the use of payment media and attracted core deposits but also allocated credit amongst diverse retail customers. We noted that allocating credit was secondary to capturing new customers and retail deposits, while the expansion of credit facilities seems to have appeared in the absence of formal credit scoring or warning on the risk of default or over-indebtedness.

We argue that a gender perspective is central to the analysis of bankarization. Our approach identifies, first, the scant attention that the financial sector paid to female customers (Lawson et al. Citation2007; Lee, Citation2014; Lee & Raesch, Citation2014). Secondly, we focus on marketing material because banking archives reveal the gendered character of bureaucratic documents which reflect the male voice. Thirdly, we analysed a previously unexplored archival source. The advertisements that targeted women were selected through a strict selection process and sourced within the surviving records of the Bank Censorship Bureau.

The complex process experienced in Spain, that intertwined gender, banking and consumer society, was similar to that observed earlier in other Western societies. In this regard, our research followed other relevant systematic studies documenting kindred experiences in France (Effosse, Citation2021), Italy (De Rosa, Citation2021), the United Kingdom (Barnes & Newton, Citation2022b), and Sweden (Husz, Citation2023).

Our research underlines the process of bank inclusion as Spanish commercial banks broadened the scope of their business portfolio by actively recruiting large numbers of female customers. We noted that most of the products and services targeted to these customers were not novel as they were already in the market. The novelty lied in the transformation of marketing campaigns. Initial efforts to create mass customer segments are fundamentally intertwined with women as customers, and particularly married women. These efforts appeared inevitably linked to the growth of a consumer society, to the advent of modernisation, and at the same time, they also enabled individuals to acquire a greater capacity to consume autonomously.

The results of the analysis of 20 years of bank advertising suggest, first, that there was an evolution in the projected image of women as customers: from the use of female figures as props – for example, supporting actors in the street or in pamphlets advertising fairs and adding a woman decked out in regional costume – to campaigns aimed exclusively at women. The evolution was not linear, nor did it occur in all banks, but there was a progression, and the large commercial banks played a key role.

We defined three phases of this evolution. A first phase encompasses a time where bank advertising characterised by the institutional image and embodied by the headquarters or photograph of the bank’s buildings, retail branches but mostly its head office. Our findings add to previous discussions by highlighting how women – and often men – appeared as mere supporting actors who add dynamism to the scene.

A second stage, coincided with the product diversification of commercial banks, where they sought to offer a greater number of services to their established customers and attract new (mainly female) customers. The long-term effect of the expansion of standardised products and services to middle class and less well-off customers, signified the end of personally negotiated offerings between retail bank branch managers and well-off clients (Ackrill & Hannah, Citation2001; Deng et al. Citation1991; Vik, Citation2017). Meanwhile, this diversification of commercial banks, that pivots on marketing campaigns aimed at men, followed strict profiles marked by their profession. For women there was a single profile defined by their gender and age.

At the end of the 1960s, some banks launched specific campaigns aimed at the female public for the first time in their history with a language that emphasised communication in the first person. Banks adopted a discourse which included references to women’s rights, a new narrative that sought to connect with a younger, emancipated, sometimes highly educated and independent public. These campaigns aimed exclusively at women by Spanish banks left iconic advertising images for posterity, but while they also included their domestic profile their novelty resided in targeting professional women. As noted above, similar campaigns had already been carried out in other European countries, where banks also made efforts to attract women’s savings and encourage daily finances.

Research in this paper placed the Spanish case inside a novel international debate. One which looked at the creation of an advertising narrative in which women’s rights were the communicative banner of a traditional and conservative sector such as banking. As opposed to advertising which appealed to the corporate image embodied by the bank’s headquarters, or in the image of the founders, advertising appeared to start to develop while portraying a modern and cheerful mannequin representing young housewives who see banking services as the perfect ally to alleviate their domestic duties.

This research also leaves several questions unresolved. One relates to the scale and impact of these publicity campaigns. This calls for new archival research to locate sources in the archives of individual commercial banks which document the impact of such campaigns, by product, and, ideally, to quantify the number of women customers’ accounts. As such, future research will continue to allow us to broaden our understanding of the process of bankarization and the role of women in its implementation as part of everyday life.

Archival sources

AHBE: Archivo Histórico del Banco de España. Fondo Banca Privada – Censura de Publicidad (1949-1970) (Reference Code: ES.28079.AHBE/01.11).

Acknowledgements

Authors appreciate comments by participants to the World Economic History Conference (Paris, 2022), Business History Conference (Mexico City, 2022), staff presentation at the Sociology and Media Studies Department (University of La Coruña, 2022), II Iberian Colloquium on Business History (University of Sevilla, 2022), Seminar Women and Marketing (Complutense University of Madrid, 2023) and particularly those from Gustavo del Angel, Victoria Barnes, Mark Crawley, Sabine Effosse, Victor Flores, José Luis García Ruiz, Johanna Gautier-Morin, Orzi Husz, Gordon Mayze, Alan McKinlay, Manuel Ruiz-Adame, Valerie Shaffer, Scott Taylor, Florian Vetter, and Peter Wardley. Extensive thanks to the staff at the Archivo Histórico del Banco de España, the editors of the journal, and anonymous referees.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Susana Martínez-Rodríguez

Susana Martínez-Rodríguez is an Associate Professor of the Economic History at the University of Murcia (Spain). She has published in referred journals such as Business History, Business History Review, European Review of Economic History, Journal of Law, Economics and Organisation, Feminist Media Studies, Feminist Economics. Her current research explores how financial institutions orientated their services to women.

Bernardo Bátiz-Lazo

Bernardo Bátiz-Lazo is a Professor of FinTech History and Global Trade at Northumbria University in Newcastle upon Tyne (UK) and research professor at Universidad Anahuac (Mexico). He is a fellow of the Royal Historical Society and the Academy of Social Sciences. He is a member of the editorial board of ‘Business History’ and since 1999, edits NEP-HIS, a weekly report on new additions to economic and business history (http://nep.repec.org).

Notes

1 Throughout the paper we use retail and commercial banks indistinctively, to denominate public (i.e. stock-traded), limited liability, diversified, financial institutions specialized in capturing large volume of retail deposits from the general public through their retail branches.

2 Daily finance—also known as the finances of everyday life—has an essential antecedent in the sociology of personal finance and the exchanges that economic actors carry out in commercial circuits (Martin, Citation2002). Although, most other research uses the concept of ‘everyday life’ (Hall, Citation2013; Lai, Citation2017; Langley, Citation2008).

3 The diversity of organizational forms within Spanish banking included specific forms of corporate governance (such as savings banks, government-owned banks and co-operative banks) and specialization (such as the industrial banks in financing specific sectors) (Martín-Aceña, 2012).

4 See also Google NGram Viewer for financial exclusion [https://shorturl.at/qtCH0] and financial inclusion [https://shorturl.at/erwCI] (Accessed May 3, 2023).

5 See further (Husz, Citation2023) for an historical assessment of the birth of the European financial consumer.

6 Law 56/1961 of 22 July 1961 on women’s political, professional and labor rights (BOE, Citation1961a).

7 This measure did not prohibit a recognized bank from making standard business announcements such as details of annual general meetings, stock offerings or other capital issues, or details of projected new retail branches.

8 In 1975 the provinces of Madrid, Barcelona and Valencia housed 2,467 (86%) out of 2,839 retail branches of commercial banks and captured 47% of total deposits (Fernández Sánchez, Citation2023).

9 AHBE-BP. 188 Banco de Vizcaya collection: request to the Banco de Vizcaya, date of reply 9 November 1950; AHBE-BP. 189 Banco de Vizcaya collection: request addressed to the Banco de Vizcaya, date of reply 2 February 1956; AHBE-BP. 991 Banco de Bilbao-Londres: request addressed to the BE date of reply 15 September 1965.

10 AHBE-BP.187 Banco Popular Español: authorization to publish a new add from the BE, date of the reply 8 October 1956.

11 AHBE-BP. 1007 Banco Español de Crédito: application to the BE dated 20 March 1968; AHBE-BP. 1007/ Banco Español de Crédito: no date, no application. AHBE-BP. 189 Bank of London & South America Limited: application to the BE, date of reply 3 February 1953.

12 AHBE-BP. 1128 Banco Castellano: application to the BE, date of reply 11 July 1960.

13 AHBE-BP. 1128 Banco Popular Español: request addressed to the Banco Popular Español, date of reply 2 March 1965.

14 AHBE-BP. 1128 Banco Popular Español: request to the BE, date of reply 10 December 1966.

15 AHBE-BP. 1012 Banco de La Coruña-Banco Bilbao reply of BE 10 July 1969.

16 AHBE-BP. 1012 Banco Asturiano-Banco Bilbao reply from BE 22 September 1969.

17 AHBE-BP. 1009 Unión Industrial Bancaria reply from the BE 22 October 1968.

18 AHBE-BP. 1006 Banco de Bilbao: request to the BE dated 26 November 1968.

19 AHBE-BP. 182 Banco Español de Crédito: application to the Banco Español de Crédito, date of reply 8 June 1953.

20 AHBE-BP. 992 Banco de Granada: request to the BE, date of reply 28 September 1966.

21 AHBE-BP. 1013 Banco del Norte reply from BE 29 July 1969.

22 AHBE-BP. 1006 Banco de Andalucía: application to the BE dated 25 April 1967.

23 AHBE-BP. 994 Banco Vizcaya Fund: application to the BE 27 December 1965.

24 AHBE-BP. 994 Banco Vizcaya: request to the BE 27 December 1965.

25 AHBE-BP. 1130 Banco Popular Español: request to the BE, date of reply 12 February 1962.

26 AHBE-BP. 1130 Banco Popular Español: request to the BE, date of reply 28 March 1960.

27 AHBE-BP. 994 Banco Vizcaya: reply from the Banco Vizcaya, 19 April 1966.

28 AHBE-BP. 1012 Banco de La Coruña-Banco Bilbao reply from the BE 10 July 1969.

29 AHBE-BP. 1012 Banco de La Coruña-Banco Bilbao reply from the BE 10 July 1969.

30 AHBE-BP. 1129 Fondo Banco Español de Crédito: request addressed to the Banco Español de Crédito, date of reply 14 September 1961.

31 AHBE-BP. 1132 Banco Bilbao: application to the BE, date of reply 13 December 1960.

32 AHBE-BP. 992 Banco Coca: request addressed to the EIB, date of reply 5 July 1966; AHBE-BP. 991 Holdings Banco Castellano/Valladolid: request addressed to the BE date of reply 6 April 1965.

33 AHBE-BP. 1130 Banco Santander Fund: request addressed to the BE, date of reply 12 December 1961.

34 AHBE-BP. 1130 Banco Santander Fund: request addressed to the BE, date of reply 12 December 1961.

35 AHBE-BP. 991 Banco de Bilbao-Paris: request addressed to the BE, date of reply 2 August 1965.

36 AHBE-BP. 1008 Banco de Santander sent to the BE reply from BE 30 October 1967.

37 AHBE-BP. 1008 Banco de Santander sent to the BE reply from the BE 30 October 1967.

38 By the mid-1960s, women constituted 53% of students enrolled in Pharmacy degrees within universities (INE, Citation1966, pp. 8–9). In secondary schools and occupational programs for nurses and laboratory technicians, 72.1% of the students were women, and the same trend was observed among students pursuing careers related to childcare (100%) (INE, Citation1973). However, STEM fields such as Engineering continued to observe a low percentage of female students, with less than 5% representation (Fundacion FOESSA, Citation1975, p. 276).

39 AHBE-BP. 1009 Banco de Vizcaya reply from the BE 27 February 1968.

40 AHBE-BP. 1009 Banco de Vizcaya reply from the BE, 27 February 1968.

41 Boletín Oficial del Estado (BOE) n. 22, 26 January 1967, p. 1119 - 1123.

42 AHBE-BP. 1014 Banco de Vizcaya sent to the BE 25 April 1969.

43 AHBE-BP. 1014 Banco de Santander sent to the BE 29 March 1969

44 Average value as reported by ‘Measuring Worth’.

https://www.measuringworth.com/calculators/spaincompare/relativevalue.php (accessed 25 August 2023).

45 AHBE-BP. 1014 Banco Peninsular: request sent to the BE 18 April 1969.

46 AHBE-BP. 1014 Banco Peninsular: request sent to the BE 18 April 1969.

47 AHBE-BP. 1012 Banco de Bilbao: request sent to the BE 14 April 1969.

48 AHBE-BP. 1012 Banco de Bilbao: request sent to the BE 14 April 1969.

49 AHBE-BP. 1013 Banco de Londres y América del Sur reply from BE 19 November 1969.

50 AHBE-BP. 1243 Banco Atlántico reply from BE 24 June 1970.

51 The measure allowed a recognized bank from making standard business announcements such as details of annual general meetings, stock offerings or other capital issues, or details of projected new retail branches.

52 See further Tortella (2010) on major regulatory innovations relating to Spanish retail banking in 1921, 1942 and 1962. See Sánchez Fernández (2023) on the competitive effects of the latter.

53 The classification ISAD(G) includes the following categories: (1) Collection: a set of documents produced by an institution or entity; (2) Series: a set of documentary units generated by an institution that are generated periodically referring to the same activity following a standardized procedure; (3) Records: an organized unit of documents with a common subject or origin: they are the result of the same recipient or issuer, or refer to the same subject; (4) Single records or documents: a simple documentary unit or document. It is the most elementary archival unit (Consejo Internacional de Archivos- ISAD(G), Citation2000).

54 ‘A copy in any type of support, testimony of the activities and functions of natural and legal, public or private persons’ (BOE, Citation2011).

References

- Ackrill, M., & Hannah, L. (2001). Barclays: The business of banking, 1690-1996. Cambridge University Press.

- Barnes, V., & Newton, L. (2017). Constructing corporate identity before the corporation: Fashioning the face of the first English joint stock banking companies through portraiture. Enterprise & Society, 18(3), 678–720. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2016.90

- Barnes, V., & Newton, L. (2018). Visualizing organizational identity: The history of a capitalist enterprise. Management & Organizational History, 13(1), 24–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2018.1431552

- Barnes, V., & Newton, L. (2022a). Corporate identity, company law and currency: A survey of community images on English bank notes. Management & Organizational History, 17(1–2), 43–75. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2022.2078371

- Barnes, V., & Newton, L. (2022b). Women, uniforms and brand identity in Barclays Bank. Business History, 64(4), 801–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2020.1791823

- Bátiz-Lazo, B. (2004). Strategic alliances and competitive edge: Insights from Spanish and UK banking histories. Business History, 46(1), 23–56. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790412331270109

- Batiz-Lazo, B., & Del Angel, G. A. (2018). The ascent of plastic money: International adoption of the bank credit card, 1950–1975. Business History Review, 92(3), 509–533. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007680518000752

- Bernards, N. (2022). A critical history of poverty finance. Pluto Press. https://www.plutobooks.com/9780745344829/a-critical-history-of-poverty-finance/

- BOE. (1938). Fuero del trabajo, 8 de marzo de 1938, 10 de marzo. Boe (Boletín Oficial Del Estado), 505, 6178–6181.

- BOE. (1944). Decreto de 2 de junio de 1944 por el que se aprueba con carácter definitivo el Reglamento de la organización y régimen del Notariado, 7 de julio de 1944. Boe (Boletín Oficial Del Estado), 89, 1–121.

- BOE. (1961a). Ley 56/1961, de 22 de julio, sobre derechos políticos, profesionales y de trabajo de la mujer, de 24 de julio de 1961. Boe (Boletín Oficial Del Estado), 175, 11004–11005.

- BOE. (1961b). Ley 84/1961, de 23 de diciembre, sobre el Plan Nacional de la Vivienda para el periodo 1961-1976, de 28 de diciembre de 1961. Boe (Boletín Oficial Del Estado), 310, 18215–18216.

- BOE. (1966). Ley 14/1966, de 18 de marzo, de Prensa e Imprenta, de 19 de marzo de 1966. Boe (Boletín Oficial Del Estado), 67, 3310–3315.

- BOE. (1975). Ley 14/1975, de 2 de mayo, sobre reforma de determinados artículos del Código Civil y del Código de Comercio sobre la situación jurídica de la mujer casada y los derechos y deberes de los cónyuges, de 5 de mayo de 1975. Boe (Boletín Oficial Del Estado), 107, 9413–9419.

- BOE. (2011). Real Decreto 1708/2011, de 18 de noviembre, por el que se establece el Sistema Español de Archivos y se regula el Sistema de Archivos de la Administración General del Estado y de sus Organismos Públicos y su régimen de acceso. Boe (Boletín Oficial Del Estado), 284, 1–22.

- Bonin, H. (2014). Banque et identité commerciale: La Société générale, 1864–2014. Presses Universitaires du Septentrion.

- Cabrera Pérez, L. A. (2005). Mujer, trabajo y sociedad (1839-1983). Fundación Largo Caballero-Fundación BBVA.

- Consejo Internacional de Archivos- ISAD(G). (2000). Norma internacional general de descripción archivística. Adoptada por el Comité de Normas de Descripción. Estocolmo, Suecia, 19-22 septiembre 1999 (traducción del texto original inglés). Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte.

- Crowley, M. J. (2012). The indispensable position of women Post Office workers in Britain, 1935-1950. Essays in Economic & Business History, 30, 77–92. https://www.ebhsoc.org/journal/index.php/ebhs/article/view/218

- De Dios Fernández, E. (2022). Las chicas yeyé, las amas de casa de sopa de sobre y otras mujeres modernas (España 1955-1975). Arenal. Revista de Historia de Las Mujeres, 29(1), 285–317. https://doi.org/10.30827/arenal.v29i1.22823

- De Inclán, M., Serrano García, E., & Calleja Fernández, A. (2019). Guía de archivos históricos de la banca en España (Serie: Pub). Banco de España Eurosistema

- De Rosa, M. R. (2021). «Ample collateral». Women’s money, the Italian laws and the access to bank credit in the twentieth century. Quaderni Storici, 61(1), 86–116. https://doi.org/10.1408/101557

- Deng, S., Moutinho, L., & Meidan, A. (1991). Bank branch managers in a marketing era: Their roles and functions in a marketing era. International Journal of Bank Marketing, 9(3), 32–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/02652329110143704

- Effosse, S. (2017). El cheque en Francia: El lento ascenso de un medio de pago de masas, 1918-1975. Revista de La Historia de La Economía y de La Empresa, 11, 77–94.

- Effosse, S. (2021). Financial empowerment for married women in France. The matrimonial regime reform of 13th July 1965. Quaderni Storici, 61(1), 117–141. https://doi.org/10.1408/101558

- European Commission. (2008). Financial services provision and prevention of financial exclusion group. European Commision. chrome-extension://efaidnbmnnnibpcajpcglclefindmkaj/https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/geography/migrated/documents/pfrc0806.pdf

- Fernández Sánchez, P. (2023). Regulación y concentración bancaria en España: Un análisis regional, 1962-1975. Investigaciones de Historia Económica, 20 pp. https://doi.org/10.33231/j.ihe.2023.05.003

- Fox, S. R. (1984). The mirror makers: A history of American advertising and its creators. University of Illinois Press.

- Francois, M. E. (2006). A culture of everyday credit: Housekeeping, pawnbroking, and governance in Mexico City, 1750-1920. University of Nebraska Press. https://www.nebraskapress.unl.edu/nebraska-paperback/9780803269231/

- Fundacion FOESSA. (1975). Estudios sociológicos sobre la situación social de España. Fundación FOESSA.

- Fundación FOESSA. (1970). Informe sociológico ssobre la situación social de España. Fundación FOESSA.

- García Ruiz, J. L. (2017). La innovación financiera y la caída de los grandes bancos de Madrid (1960-2000). Transportes, Servicios y Telecomunicaciones, 35, 67–95.

- Garrett-Scott, S. (2019). Banking on freedom. Black women in U.S. finance before the new deal. Columbia University Press. https://doi.org/10.7312/garr18390

- Hall, S. (2013). Geographies of money and finance III. Progress in Human Geography, 37(2), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132512443488

- Heller, M. (2008). Work, income and stability: The late Victorian and Edwardian London male clerk revisited. Business History, 50(3), 253–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790801967436

- Heller, M., & Kamleitner, B. (2014). Salaries and promotion opportunities in the English banking industry, 1890–1936: A rejoinder. Business History, 56(2), 270–286. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2013.771340

- Husz, O. (2015). Golden everyday. Housewifely consumerism and the domestication of banks in 1960s Sweden. Le Mouvement Social, 250(1), 41–63. https://doi.org/10.3917/lms.250.0041

- Husz, O. (2023). The birth of the finance consumer: Feminists, bankers and the re-gendering of finance in mid-twentieth-century Sweden. Contemporary European History, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0960777323000383

- Husz, O., & Bouyssou, R. (2015). Comment les salariés suédois sont devenus des consommateurs de produits financiers : l’expérience des « comptes chèques salariaux » dans les années 1950 et 1960. Critique Internationale, N° 69(4), 99. https://doi.org/10.3917/crii.069.0099

- INE. (1965). Población activa, encuesta, 1964. INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística).

- INE. (1966). Estadística de la enseñanza superior en España, curso 1963-1964. INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística).

- INE. (1969a). Censo de la Población 1960. Tomo III, volúmenes provinciales. INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística).

- INE. (1969b). Población activa en 1968. INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística).

- INE. (1973). Estadística de la enseñanza en España, 1972. INE (Instituto Nacional de Estadística).

- Kempson, E., Whyley, C., Collard, S., & Caskey, J. (2000). In or out? Financial exclusion: A literature and research review. Financial Services Authority.

- Lai, K. P. (2017). Unpacking financial subjectivities: Intimacies, governance and socioeconomic practices in financialisation. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 35(5), 913–932. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775817696500

- Langley, P. (2008). The everyday life of global finance. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:Oso/9780199236596.001.0001

- Lawson, D., Borgman, R., & Brotherton, T. (2007). A content analysis of financial services magazine print ads: Are they reaching women? Journal of Financial Services Marketing, 12(1), 17–29. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fsm.4760059

- Lee, M. (2014). A review of communication scholarship on the financial markets and the financial media. International Journal of Communication, 8, 715–736.

- Lee, M., & Raesch, M. (2014). How to study women, gender, and the financial markets: A modest proposal for communication scholars. Feminist Media Studies, 14(2), 339–343. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2014.887817

- Maclaran, P. (2012). Marketing and feminism in historic perspective. Journal of Historical Research in Marketing, 4(3), 462–469. https://doi.org/10.1108/17557501211252998

- Maixé-Altés, J. C. (2022). The dynamics of inclusive finance in Spain, 1835-2008. XIII Congreso Internacional AEHE. Panel 21.

- Martín Aceña, P. (2012). The Spanish banking system from 1900 to 1975. In J. L. Malo de Molina & P. Martín Aceña (Eds.), The Spanish Financial System Growth and Development Since 1900. (pp. 99–143). Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Martin, R. (2002). Financialization of daily life. Temple University Press.

- Martínez-Rodríguez, S. (2021). La revista DIANA y sus señas de identidad: Formación, trabajo, independencia y finanzas. In J. C. Benítez Figuereo & R. Chávez Mancinas (Eds.), Las redes de la comunicación: Estudios multidisciplinares actuales (pp. 162–182). Dykinson. https://hdl.handle.net/11441/127641

- Martínez-Rodríguez, S. (2023). DIANA (1969-1978): The first women’s finance magazine in Spain. Feminist Media Studies, 23(5), 1889–1904. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2022.2055606

- Martínez-Rodríguez, S., & Batiz-Lazo, B. (2023a). Figure 1. Flow chart for the selection of archival material - Fund Commercial Banking of AHBE. AHBE: Archivo Histórico del Banco de España. Fondo Banca Privada – Censura de Publicidad (1949-1970) (Reference Code: ES.28079.AHBE/01.11). Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24082455

- Martínez-Rodríguez, S., & Batiz-Lazo, B. (2023b). Images of the paper "Gender and Bankarization in Spain,1949-1970". Figshare. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.24079200

- Martínez-Rodríguez, S., & Lopez-Gomez, L. (2023). Gender differential and financial inclusion: Women shareholders of Banco Hispano Americano in Spain (1922–35). Feminist Economics, 29(3), 225–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545701.2023.2213709

- McKinlay, A. (2002). ‘Dead selves’: The birth of the modern career. Organization, 9(4), 595–614. https://doi.org/10.1177/135050840294005

- McKinlay, A. (2013). Banking, bureaucracy and the career: The curious case of Mr Notman. Business History, 55(3), 431–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2013.773683

- McLaughlin, E., & Pecchenino, R. (2021). Financial inclusion with hybrid organizational forms: Microfinance, philanthropy, and the poor law in Ireland, c. 1836–1845. Enterprise & Society, 23(2), 548–581. https://doi.org/10.1017/eso.2020.67

- Montero, M. (2012). La publicidad española durante el franquismo (1939-1975). De la autarquía al consumo. Hispania, 72(240), 205–232. https://doi.org/10.3989/hispania.2012.v72.i240.369

- Ossandón, J. (2014). Sowing consumers in the garden of mass retailing in Chile. Consumption Markets & Culture, 17(5), 429–447. https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2013.849591

- Rivière, M. (1977). La moda ¿comunicación o incomunicación? Gustavo Gili.

- Rodríguez Martín, N. (2021). La publicidad y el nacimiento de la sociedad de consumo: España, 1900-1936. Catarata.

- Rodríguez Martín, N., & Miras, J. (2021). ‘La más útil joya del hogar’: La promoción de los primeros electrodomésticos en España, 1900-1936. Aportes. Revista de Historia Contemporánea, 36(107), 183–213.

- Rouse, M. (2020). Essays on financial inclusion and mobile banking. Prifysgol Bangor University.

- Rutterford, J., & Maltby, J. (2006). “The widow, the clergyman and the reckless”: 1 Women investors in England, 1830-1914. Feminist Economics, 12(1–2), 111–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700500508288

- Samy, L. (2012). Extending home ownership before the First World War: The case of the Co-operative Permanent Building Society, 1884-19131. The Economic History Review, 65(1), 168–193. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0289.2010.00596.x