Abstract

Previous research in business and management history has identified the Icarus paradox, which describes how organisations may fall due to overconfidence and hubris. We build upon previous research on paradoxes in business history and introduce the notion of an inverted Icarus paradox. Using rich archival sources coded in a relational database, we show how an entrant firm, Comvik, outmanoeuvred an established government monopoly in the non-market domain from 1980 to 1990, despite inferior resources and a weak market position. The government monopoly Televerket faced an inverted Icarus paradox; it could not leverage its strengths and political connections as they were stuck in a David versus Goliath narrative where public opinion was more sympathetic to the entrant firm Comvik.

Introduction

The history of business is full of paradoxes, but surprisingly, few business history papers have made use of or sought to further develop theory on paradoxes. The convergence of paradox theory and business history has been pointed out as a promising field of research (Putnam et al., Citation2016) and can be regarded as part of a trend of rapprochement between history and organisation studies, which is likely to grow in significance in the coming years (Cheung et al., Citation2020; Laurell et al., Citation2020; Maclean et al., Citation2021; Yates et al., Citation2013).

Literature on industrial dynamics has identified an Icarus paradox where large successful firms may be toppled by entrants. Conversely, literature in political economy and Corporate Political Activity (CPA) usually tells a story of how large, vested interests can capture regulation, shape it to its own favour and consequently strengthen their position vis-a-vis entrant firms. An inverted pattern, where established and powerful monopolists fail to dominate politically would constitute another paradox. The prevalence of such a paradox has been discussed and partially explained by Jarzabkowski et al. (Citation2013), who underscores that paradoxes of organising – in their case organising as a market actor and being a regulator of the same market – give rise to structural tensions internally, which in turn manifest as paradoxes of performing and belonging. These paradoxes can collectively create a vicious cycle of strategic passivity, a phenomenon we address and try to explain in this paper by exploring other factors, primarily the roles of temporality and institutional complexity in the surrounding environment.

This paper explores under what industrial and temporal circumstances an established monopolist with superior resources may fail to influence the regulatory set-up to its favour and why an entrant firm with inferior resources would be able to gain the upper hand in the non-market arena. Specifically, we set out to answer the following research question:

How can an established incumbent monopolist with superior political connections and resources fail to capture the regulatory process and lose political influence to a small entrant firm?

In doing so, we present a paradox that fits into the framework identified by Keyser et al.’s (Citation2019) of pinpointing antithetical or puzzling issues that produce contradictions in time and space. We show how an incumbent firm is bound and constrained by its superior resources to such an extent that it becomes passive and even defensive while the competing entrant firm successfully engages in proactive strategies aimed to capture the regulatory process. We argue that these observations can be referred to as an inverted Icarus paradox, defined as a pattern of strategic behaviour where a firm controls resources and possesses capabilities that make it superior vis-à-vis competitors but still loses as it is put in a position where it cannot leverage any of its assets. Our findings build upon Jarzabkowski et al. (Citation2013) who have previously emphasised paradoxical tensions between on the one hand market power and on the other hand the regulatory power held by a Telco utility firm. We draw on this contribution by looking at how temporal aspects in the surrounding environment enforce structural tensions between various divisions inside a firm.

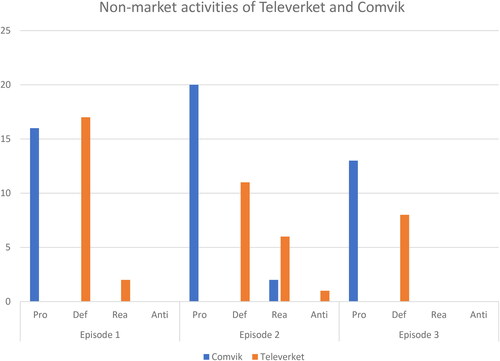

We explain the mechanisms of this inverted Icarus paradox by comparing and contrasting the non-market activities of Televerket and Comvik.

Using extensive archival sources that we have collected and digitised, we have coded all of Comvik’s micro-level activities towards the formal institutions of the sector over a 10-year period between 1981 and 1990 and compare this data with the related non-market activities of the telecommunication monopoly Televerket. By drawing inspiration from Oliver and Holzinger’s (Citation2008) typology of non-market strategies (proactive, reactive, defensive, and anticipatory), we code and classify the strategic activities of both organisations. Relatedly, we illustrate how digitised and database-coded archives open possibilities to study micro-level entrepreneurial strategies in shaping market regulation.

Theoretical review

We begin this review by covering paradox theory and business history. Next, we turn to related research streams in business administration, institutional theory and political economy. Throughout this paper, we rely on the definition of a paradox as a ‘persistent contradiction between interdependent elements’ (Schad et al., Citation2016, p. 10). A core element of paradox theory is therefore the assumption that organisations may be subject to contrasting and systemically interrelated forces.

A recent literature review identified 476 publications on paradoxes in management and organisation research (Keyser et al., Citation2019). This review highlights that the concept of a paradox has been used to advance literature in a wide range of research areas such as change management (Lüscher & Lewis, Citation2008), innovation management (Sheep et al., Citation2017) and organisational identity (Ashforth & Reingen, Citation2014).

Keyser et al. (Citation2019) map out three different and complementary ways that the notion of a paradox is used in research. One domain of research has been focused on theorising concerning paradoxes, where paradox research is regarded as a distinct theoretical construct. Second, a body of literature is identified that is explicitly concerned with either explaining certain empirical phenomena or the development of other bodies of literature. A third category of research is merely making use of the term paradox as a descriptive word aimed to point out a topic as surprising or complex.

While paradox literature has become increasingly popular in several domains of the social sciences, paradoxes are so far understudied and underexplored in the domain of business history. There is considerable potential in applying the notion of a paradox to business history, both when describing and explaining certain events and in the development of new theory concerning paradoxes. The business historians’ close attention to details and temporality, may also generate novel insights into the dynamics and evolution of paradoxes over time.

The Icarus paradox in business history

Several scholars in business history and business administration have described and explained the mechanisms giving rise to an Icarus paradox (eg Rooij, Citation2015; Sulphey, Citation2020). In essence, firms use their strengths to gain success, but the same strengths make them fly too close to the sun, their wings burn, and they fall (Miller, Citation1990, Citation1992). Overconfidence is, therefore, an integral part of the Icarus paradox. Similar arguments have been brought forward in literature on strategic management, where it has been emphasised that core capabilities may turn into core rigidities (Leonard-Barton, Citation1992). The original articles on the Icarus paradox were explicitly concerned with how successful firms’ overreach:

Their victories and their strengths so often seduce them into the excesses that cause their downfall. Success leads to specialization and exaggeration, to confidence and complacency, to dogma and ritual.Footnote1

The Icarus paradox and technological change

Without explicitly referring to it as an Icarus paradox, there is now a long and established body of research on how entrants may topple established firms under conditions of discontinuous technological change. This dilemma has sometimes been referred to as the incumbent’s curse. Examples include photography giant Eastman Kodak (Sandström, Citation2013), instant photography firm Polaroid (Tripsas & Gavetti, Citation2000), and cell phone manufacturer Nokia. There are, in fact, examples of entire industries where all previously dominant firms lost their hegemony when the underlying technology was changed: including the transition from mechanical to electronic calculators, the shift from vacuum tube-based radios to transistor radios, and the displacement of typewriters by word processors.

Several factors have been identified as jointly contributing to the downfall of established firms. New technology may render established competencies obsolete as new skill sets may be required to develop new technology (Tushman & Anderson, Citation1986). Likewise, non-technical assets such as sales organisations, brands, and specialised machinery may lose some of their value or inhibit a timely response from an organisation (Tripsas, Citation1997).

The Icarus paradox and institutional change

A large and growing literature in business administration has underscored the importance of addressing institutions and institutional change when studying firms and industries (Peng et al., Citation2009). Relatedly, institutional entrepreneurship and work refers to the deliberate attempts by specific actors to change institutions (Garud et al., Citation2002; Glynn & D’Aunno, Citation2023). Institutional complexity has also been proposed as a fruitful framework to theorise the competing demands at the core of paradox theory (Smith & Tracey, Citation2016).

How are institutions and institutional change related to the Icarus paradox? Will the emergence of new institutions and attempts to influence institutions result in the downfall of successful firms, or will they be able to influence the shaping of the institutions?

Literature on competition and regulation has highlighted how vested interest groups can influence the institutional environment (Acemoglu & Robinson, Citation2006) due to superior financial and relational resources. Economists have long regarded policy as captivated by industry which receives benefits from politicians in exchange for control over market entry, prices, and direct subsidies in exchange for votes and contributions (Shaffer, Citation1995). Public choice theory takes economics’ core assumptions regarding scarce resources and rational self-maximizing behaviour into the realm of politics (Buchanan, Citation1980). Empirical investigations usually tell a story of vested interest groups engaging in regulatory capture, shaping formal institutions to their benefit due to superior resources and at the expense of entrant firms (Lawrence, Citation1999).

At the same time, entrepreneurs are incentivised to participate in creating institutions and forming markets (Henrekson & Sanandaji, Citation2011) as they may also reap the rewards from the market that is to be constructed. Previous research has documented their participation in such activities regarding the evolution of informal institutions such as standards within an industry (Garud et al., Citation2002) and the education of stakeholders (Aldrich & Fiol, Citation1994).

The Icarus paradox and non-market activity

Firm efforts to influence policy are sometimes referred to as non-market strategy. An important issue in non-market strategy concerns to what extent firms are driven by compliance or actively try to influence the political environment (Buysse & Verbeke, Citation2003) actions in the literature referred to as corporate political activity.

Based on such distinctions, Oliver and Holzinger (Citation2008) developed a typology of political strategies that has been used in numerous articles, primarily in management studies, but only occasionally in business history (Kaplan, Citation2021). The framework includes proactive, reactive, defensive, and anticipatory strategies. Proactive refers to the attempts to influence the institutional set-up to create a more favourable position. Reactive strategies are more focused on compliance and passive adaptation of internal capabilities to cope with the political environment, eg developing pollution control systems. Defensive strategies concern attempts to protect an institutional status quo by, for instance, opposing or defending against the proactive attempts from other actors who try to change institutions. Finally, anticipatory strategies involve aligning one’s capabilities towards a potential shift in the surrounding environment.

Synthesis and research problem: paradox theory and regulatory capture

Summing up the above review, several strands of literature in business administration provide valuable input on whether an Icarus paradox is likely to prevail or not. Research on technological change and industrial dynamics has described several examples and factors related to the downfall of successful firms but also emphasised that established firms may possess critical non-technical assets that can shelter them from competence destruction and disruption (Tripsas, Citation1997).

Likewise, research on institutions and institutional change has identified factors that determine whether established firms are toppled by entrants or not. For example, incumbents may posit superior financial and relational resources, enabling them to capture the regulatory process. At the same time, entrants may be more incentivised to engage in institutional entrepreneurship and proactive non-market activities as they have little to lose.

Opening the black box of entrepreneurial action in the non-market domain may reveal key insights into the Icarus paradox and its underlying social mechanisms. In particular, the micro-level strategic behaviour of entrepreneurs and incumbents vis-à-vis regulation needs to be better understood.

Literature on paradox theory has underscored that incumbent firms may at times be hampered by their strong market position. Studying a telecommunications firm, Jarzabkowski et al. (Citation2013) observed that state-controlled monopolists who act both as market actors and regulators face paradoxical tensions which may inhibit them from regulatory capture. The structural tensions between the different organisational units of such a firm may result in paradoxical tensions, which may in turn manifest as a vicious cycle of defensive and passive behaviour. Paradoxes of organising into different units in turn gave rise to paradoxes of belonging and performing. The authors pointed out an interesting avenue for future research as they:

encourage future studies to investigate how different types of responses may or may not be embedded within organizing outcomes. In addition, future research could study what contexts and actions repeat our pathways, when actors may shortcut our defensive path by moving directly to active responses, or when they may become stuck in a vicious circle of defensive responses. (Jarzabkowski et al., Citation2013, p. 269)

How can an established incumbent monopolist with superior political connections and resources fail to capture the regulatory process and lose political influence to a small entrant firm?

We are explicitly concerned with the paradoxical tensions between market power and regulatory power and how these may create a paradox of passivity for an incumbent monopolist who should arguably have been able to mould the regulatory process. While earlier reasoning underscored how organisational tensions give rise to other paradoxes and a vicious cycle of passivity, we build on their research by addressing the extent to which context and temporality interplay with the different paradoxes. For example, attempts to reconcile institutional complexity and paradox theory point us in a direction where the institutional context is a key explanatory factor for how both organisational actors and actors within the organisations play out the paradoxes over time (Smith & Tracey, Citation2016). Here, rigorous historical methods offer opportunities to delve deeper into the changing nature and persistence of paradoxes over time.

Method

We have used a rich set of material from several different archives consisting of Televerket’s management minutes, mail correspondence between Televerket, Comvik, and other key actors, as well as minutes from meetings between key actors, government authority decisions, court rulings, and newspaper articles. The archival material is varied and can be classified into three different categories. The first category is the internal and external communication activity from Televerket and Comvik, which includes management minutes, letter correspondence, and meeting protocols. The second includes government decisions that describe the activities’ outcome in the first category. Finally, the third category contains media coverage concerning conflicts between Televerket and Comvik.

In contrast to Televerket, Comvik has no preserved archives. However, the regulatory structure of the telecommunications market in Sweden, where Televerket was also the regulator and the focus was on non-market activities, makes this less of a problem. The relevant correspondence from Comvik is thus preserved in the Televerket archives; there is even a special collection of documents related to Comvik (‘Comvikaffären’) in the Televerket archives. Together with archival sources from government archives, such as the Competition Ombudsman and the department of Communications.Footnote2 We have also supplemented the archival sources with media articles. While we are missing some internal planning and strategic deliberations by Comvik, the various non-market activities can nevertheless be tracked as traces of them, which are found both at Televerket and at the various regulatory bodies concerned.Footnote3

In the digitised archive material, all documents can be found as physically located in the archives they come from: the Swedish National Archives and Televerket’s archives at the Centre for Business History. In addition, we have used a collection of internal strategy memos, reports and correspondence donated by Bertil Thorngren to the Institute for Economic and Business History Research at Stockholm School of Economics. Subsequently, these have been photographed, converted into PDF format, and filed in digital form using the software tool Filemaker. All documents have also been OCR-processed, meaning one can search for words and sentences through a search engine in this digital archive. The software allowed us to put all documents in chronological order with the exact date of events for every document. Altogether 7,117 physical documents regarding the Swedish telecom market during the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s have been photographed, digitalised and OCR-processed.

All the collected material was structured in a relational database where meta-data was coded, such as the date of the document, which actors created the document and who was the intended reader of the document. From the documents created between 1981 and 1990, all the documents mentioning Comvik or actors involved in the three episodes between Comvik and Televerket were selected. Using these documents, the coded relationships between actors and organisations and our understanding of the case, additional documents were identified.

Case context and non-market activities

Based on the source material, a large number of ‘incidents’ have been coded. An incident is an event that is either external or internal (someone does something, eg Comvik questions Televerket’s decision not to allocate more frequencies to the government). In total, we have coded 615 incidents of which 135 are connected to the three episodes that the paper deals with. The ambition is, as with all historical research, to capture all events of importance; the difference between a traditional historical approach and our method is, in principle, that when coding incidents, you can go back and show which events were found to be interesting, even if they have not subsequently been included in the publication.Footnote4

The initial question of Comvik’s right to use automatic switches was settled (1981 to July 1982),Footnote5 the question of whether Comvik could obtain more frequencies was determined (November 1981–December 1989) and finally the question of whether Ericsson (who was a partner of Televerket) could refuse Comvik’s purchase of AXE switches was resolved (August 1989–February 1990).

Some of these incidents relate to non-market activities or CPA.[i] These mainly consist of direct influence (petitions, letters, the firms own lobby efforts, or through other representatives) or of activities in the media which aim to generate media and thus influence public opinion. We went through the documents collected in the database and identified key events pertaining to the three episodes.

From the coded incidents (that also show actions taken), we have classified and coded the incidents that contain the non-market activities according to the framework of Oliver and Holzinger (Citation2008) and thus read and separated the activities into four categories: proactive, defensive, reactive, and anticipatory.Footnote6 The coding into categories were iterated three times, each by a different researcher to ensure stringency. By applying this typology, we can compare and contrast the non-market strategies of the entrant firm and the government monopoly. In , examples of non-market incidents can be seen.Footnote7

Table 1. Examples of proactive, defensive, reactive and anticipatory activities.

Table 2. A collection of quotes from Televerket’s internal document ‘Take the Leap’ from 1983.

For this study, most central is the first category, as it enables the codification of how these two firms acted. The second category is also important as it provides us with information about the institutional outcomes. The third category gives us an idea about how the actors were portrayed in the press and viewed by the public, but it can also give us information about direct non-market activity like in category one, since the actors might have used media to gain public support.Footnote8

Case description

The timeframe for this study is from 1981 to 1990. This was a technological and regulatory transformation period for the whole Western world. New technology and influential free markets and privatisation ideas led to significant institutional changes in Sweden and the Western world. Comvik came to symbolise the new era characterised by deregulation and competition as it battled the state-owned incumbent monopolist – Televerket – whose dominance largely symbolised the past.

The three episodes are selected based on what was decisive for Comvik. Had Comvik lost any of these battles, it is doubtful whether the company would have been able to survive on the Swedish market. The first was whether Comvik would have to use an obsolete switching method, the second was whether they could expand their market, and the third was whether the leading supplier of base stations could deny Comvik access to them. Which historical events are decisive is sometimes only possible to see in retrospect (Lakomaa, Citation2020, p. 12ff; Wadhwani & Decker, Citation2017, p. 114). This also means that if one of the earlier episodes had had a different outcome, the subsequent ones probably would not have occurred (they could be called critical junctures). That is, if Comvik had not been allowed to use modern switching technology, they probably would not have been able to grow so that the issue of more frequencies would have been irrelevant - perhaps they would even have withdrawn from the Swedish market.

The 1980s were characterised by a game between Comvik and Televerket where Comvik requests something (or starts to do something new). Televerket can then approve what Comvik wants (actively or by ignoring what Comvik is doing) or deny it. Only if Televerket refuses Comvik’s request can there be a conflict. Comvik can then choose to back off (and, e.g. wait and make another attempt later) or to take the fight, and they can then choose the means and the arena for the fight (market or non-market).

Against the above-described background, the Swedish telecommunications sector in the 1980s offers an interesting research area for an inquiry into the technological and institutional aspects of the Icarus paradox. This setting provides us with an incumbent monopolist, Televerket, and an entrant firm, Comvik, who competed in both the marketplace and in the non-market domain.Footnote9

Televerket, had, with few exceptions, a de facto but not a formal monopoly on the Swedish telecommunications and was at the same time a government agency. Since the 1950s, a small number of private companies had been allowed to operate mobile telephony networks.Footnote10 Demand was limited to certain professional applications. The market was however limited and profitability low. In 1981, only one of the private companies remained: ‘Företagstelefon’ (Business Telephony).Footnote11

During the 1970s, both Televerket and financier Jan Stenbecks Kinnevik Group, foresaw an increasing future demand for mobile telephony.Footnote12 Televerket co-developed and eventually launched the so-called NMT-system (Nordic Mobile Telephony system).Footnote13 In 1981 Kinnevik acquired Företagstelefon, reorganised it and changed the name to Comvik.Footnote14 Instead of using NMT Comvik instead bought a system based on a different standard, the American AMPS.Footnote15

During the time of the launch of these mobile systems on the market, several technological advancements occurred. Automatic switches were now available, and these were more effective than the old manual switches; the latter demanded a person to connect the calls, and the former did this automatically, a detail which had an initial role in the first non-market battle between Televerket and Comvik in the early 1980s.

It is clear that the events in Sweden did not occur in isolation. To the contrary, technological and regulatory turbulence in for example the United States and England affected how Comvik and Televerket were able to manoeuvre this era of upheaval and change.Footnote16 As described in previous research, Sweden followed the trajectory of especially EnglandFootnote17 On the one hand, it is clear that Televerket perceived a strong trend towards more competition and the opening of formerly monopolised markets. Conversely, Comvik and Jan Stenbeck benefitted from this trend.

With regards to technology, however, Comvik underperformed. Televerkets’s NMT was technologically more advanced than the AMPS standard used by Comvik. Comvik’s business strategy was instead to reach more price-sensitive customers (although it did not target any mass market, for which the phones were too expensive). For example, they initially only offered one telephone model. The open NMT standard on the contrary allowed users to choose among different models and marques as long they were approved by Televerket. In addition to choosing a lower price point,

Comvik also hoped to get to market first – which they did by a narrow margin – and therefore would be able to capture customers who wanted to switch from MTD to more modern technology before Televerket could respond. Here, in contrast to the classic Christensen (Citation1997) case, it was the incumbent that had developed the superior technology and the challenger that had to adapt. However, Televerket can be said to be responding to Comvik’s business strategy by later lowering prices and offering phones in a lower-price segment.

An overview of non-market strategies

presents examples of proactive, defensive, reactive and anticipatory activities gathered from documents such as letters, PM and minutes. In total, we found 135 incidents of non-market activity for Comvik and Televerket combined (for all three episodes). We later describe in further detail the strategies enacted by both Comvik and Televerket.

As can been clearly seen in , Comvik dominates the proactive activity. This is apparent in all the episodes. In the first episode, we have found 16 incidents of proactive non-market activities for Comvik and none for Telverket. In the second episode, 20 incidents for Comvik and again none for Televerket and in the third episode, 13 for Comvik and none again for Televerket. At the same time, Televerket had 17, 11 and 8 defensive non-market incidents compared with 0, 0 and 0 for Comvik. Televerket acted reactively in two incidents in episode 1 and six times in episode 2. Comvik was reactive twice in episode 2. Televerket’s defensive activity is basically following Comvik’s proactive strategy. Comvik engaged in some reactive activity in 1987 after the government had granted them the right to more frequencies. They simply reacted to this government decision and contacted Televerket for the implementation of these matters. Televerket’s reactive activity is mostly in the form of implementation of frequencies after the decision from the government.

Episode 1: battle for automatic switches

In the following sections, we describe the issues at stake during the various regulatory controversies involving Comvik and Televerket. The first battle between Comvik and Televerket concerned Comvik’s attempts to use automatic instead of manual switches.Footnote18

In the previous year, Kinnevik had already taken over Företagstelefon. The company had applied to Televerket – which was also the regulator – to be allowed to consolidate the network to the 460 MHz band and change to automatic switches.Footnote19 Televerket approved the transition but denied the connection of the switches, the latter decision being based on a policy introduced earlier that year which stipulates that ‘connection as an automatic mobile phone is not permitted’.Footnote20 It was also argued that the previous permission granted did not cover anything other than manual switches - the technology then used.Footnote21 At the time, even Televerket’s mobile telecommunications network MTD used manual switches.Footnote22

The question was of great importance. Manual switches were significantly slower in connecting calls than automatic ones and more expensive in the long run as they required staff. In the first petition to Televerket, Företagstelefon argued that a change to the new technology was essential to be able to stay in business (and compete with Televerket).Footnote23

When Comvik took over and the issue still was unresolved, they tried to circumvent this rule by introducing automatic switches with only one person at one part of the switch pushing a button, thereby minimising the efficiency loss that manual switches incurred.

Even though Televerket initially approved this system,Footnote24 they later reversed their decision and considered the system to be automatic and therefore illegitimate.Footnote25 For instance, Televerket demanded that the operator spoke with the subscriber and asked which number they wanted to be connected to instead of it being dialled by the subscriber and being displayed on a data screen at the operator and then, by pushing one button, to connect the call.Footnote26 Televerket argued that this would reduce the risk of misdialled calls and also that manual operation would be in line with Comvik’s business model.Footnote27

Televerket informed Comvik of this new decision at a meeting in September 1981, which in turn compelled Comvik to complain to the government and various government agencies and authorities, for instance the Competition Ombudsman, and demanded the right to compete on equal terms in the market and that Televerket’s position as both company and regulator of its own market made the market unfair. Comvik further claimed that these technical requirements were only marginal details, and that the real reason was that Televerket tried to hold Comvik outside the mobile telecommunication market which they had invested a large amount of money in with the development of the NMT system and thus did not want competitors.Footnote28 Comvik thus corresponded to Televerket and indicated this ‘hidden agenda’Footnote29

Televerket, on the other hand, claimed that these requirements were legitimate and that they had already given Comvik more freedom in the telecommunication market than they were obligated to. They still insisted on the demand that the operator at Comvik switches had to speak with the subscriber. In an interview Televerket’s head of external permissions Norman Gleiss stated:

There is less risk of error pairing if the operator repeats the number you requestFootnote30

We therefore ask you to return to and by 1981-10-09 use the manual capture method specified by us in the permit. If not, your telephone connection will expire, and we will disconnect your radio exchanges from the telephone network.Footnote31

Hagstöm rejected Comvik’s letter and agreed on the previous decision from the permit unit.Footnote35 However, on 1 October 1981, NO wrote a letter to Televerket where they demanded Televerket to postpone the disconnection since the case was now going to be tested.Footnote36

Comvik was finally allowed to use fully automatic switches in 1981 through a government decision. The government rationale for this decision was partly that Comvik had been in the business a long time and had a large number of subscribers who would have suffered. The decision also implied that Comvik only could use so many frequencies that it did not interfere with the quality of the system.Footnote37 The issue of frequencies became the subject of the second round.

Episode 2: battle for more frequencies

The second battle also concerned technical limitations that Televerket had imposed upon Comvik. Comvik wanted to have more frequencies for their mobile telephone system, particularly for their Skyport system for telecommunication to the US, but Televerket as the authority with the power over frequencies denied them this by referring to technical difficulties that would occur and make the whole telephone net insecure.

This time, Televerket allowed the government to decide on the issue since they considered themselves biased and that international telecommunication did require deals with foreign countries. This did not stop Televerket from making a recommendation to the government to deny Comvik’s request. The reason for this recommendation was, according to Televerket, that one operator/system used the limited number of frequencies (that they regarded as a ‘natural resource’) more effectively than two operators/systems. In a letter to the government from 23 January 1986, Televerket wrote:

The basis for the telecommunications policy on licensing is the necessity to cope with the limited natural resource radio frequency spectrum. […] A single radio system usually provides better frequency utilization than if its traffic volume were to be divided into a number of smaller systems.Footnote38

The parliament has pronounced […] that ‘telephone service is a basic utility which should be offered to everyone at a reasonable price across the country’. In addition, the parliament has stated that Televerket’s dominant position is a prerequisite for maintaining the equalization tax structure of the basic telecommunications services.Footnote39

[The] application should primarily be resolved in accordance with applicable Swedish regulations. What Televerket obviously wants to avoid is any kind of measure that can be perceived as direct or indirect support for the planned separate systems.Footnote40

This caused Comvik to initiate a process together with their attorney, in which they claimed to have reasons to believe that there was no risk for such technical difficulties and that Televerket used this argument to conceal the real reason why they did not want to give Comvik more frequencies, which according to Comvik was fear of competition.Footnote43 Comvik launched a large proactive process on several fronts. The government decided to delegate the decision back to Televerket on the 25 September 1986.Footnote44 Televerket again denied Comvik the extra frequencies.Footnote45 Comvik then contacted the completion authority to appeal against the decision.Footnote46 Comvik was finally granted 14 more frequencies, from 36 to 50, (they wanted 60), through a government decision in June of 1987.Footnote47

Episode 3: battle for AXE-switches

The last battle concerned Ericsson’s refusal to sell AXE-switches to Comvik. Comvik wanted to buy their switches for the next generation of mobile telephony called GSM. The AXE system was developed by Ericsson and Televerket. Comvik found it astonishing claimed that they wanted to focus solely on Televerket for the Swedish market.Footnote48 Comvik again suspected Televerket of interference, this time pressuring Ericsson not to sell to a competitor. Comvik was very open with this suspicion, in a letter from 18 September 1989, the CEO of Comvik wrote to the CEO of Televerket:

Ericsson is a publicly traded company for profit and can therefore hardly voluntarily refrain from an order of at least 1.5 billion kronor. It is therefore difficult to resist the idea that there is some form of direct or implied pressure from Televerket.Footnote49

In response to your letter, I would first like to emphasize two natural starting points. 1) Ericsson decides what business they want to do. 2) Televerket decides which supplier to use. From your letter, one can get the impression that competition would increase if Televerket and Comvik used the same system. But is it not true that free competition is best promoted by offering different solutions to customers? I would also like to emphasize that I find it strange that you contact Televerket when Comvik wants to do business with Ericsson.Footnote50

It is self-evident that we would not have invested hundreds of millions and much of our knowledge in a system and then sell it to our competitors.Footnote52

Comvik requested the competition authority and Televerket to bring the case to trial in September 1989.Footnote53 Since Ericsson claimed that their relationship with Televerket would be harmed if they delivered to Comvik, Comvik demanded to see what kind of deal they had in order to find out if there were any legal obstacles for Ericsson to deliver to Comvik. Ericsson claimed that there were systems available on the international market that were as good for Comvik as AXE for connection in Sweden.Footnote54 However, Comvik consulted the former Ericsson employee Nils Weidstam on this issue and he did not agree with Ericsson’s claim that there were similar systems on the market. Weidstam claimed that there could be technical difficulties with using a different system than Ericsson AXE on the Swedish net.Footnote55

Comvik’s attorney consulted the law professor Ulf Bernitz, to investigate provide a comment on the case. Bernitz’s conclusion was that Ericsson’s refusal to sell AXE to Comvik was legally harmful and should be rejected.Footnote56 The competition authority suggested that the market courtFootnote57 should approve Comvik’s demands.Footnote58 In February 1990, the minister of communication with reference to the decision in parliament on telecommunications policy - reminded Televerket that there should be a level playing field – that ‘equal opportunities are given in every area’.Footnote59 Even though Ericsson one year later had not been permitted to buy the switches, they did not pursue the case in the market court. The delays had caused Ericsson to seek an alternative supplier (Motorola) and develop new software.Footnote60

Here, Comvik again won in the non-market domain, but Televerket won in the market domain.

Analysis

In this section, we analyse the case described above. We first introduce the inverted Icarus paradox and subsequently discuss some factors enabling it to emerge.

Our results are interesting in several ways. First, they are largely incompatible with established lines of economic thought concerning regulatory capture and the role of firms in influencing policy. Scholarly work in economics and political science has long argued that large, established firms and vested interest groups tend to influence policy to their own favour as they control superior resources (eg Lawrence, Citation1999; Shaffer, Citation1995). However this body of research has paid little attention to firm contingencies. Most work has been done on the aggregated rather than on the micro-level.

Our findings counter the literature on regulatory capture as it is clear that the entrant firm Comvik won all political battles against Televerket in their attempts to build a market by influencing the institutional set-up. Televerket not only had a monopoly but also regulated its own market while also controlling superior financial and technological resources. During the 1980s, Televerket lost to Comvik time after time in the non-market domain. It can be seen how a small entrant firm could exert a more considerable influence on the regulatory change process than the incumbent monopolist.

The inverted Icarus paradox

As it is clear from our case description, the most resourceful actor (Televerket) did not gain the upper hand, thus the case fits broadly into the definition of an Icarus paradox. Nevertheless, this case is different in several regards. In previous literature, the Icarus paradox tells a story of firms pushing their superior position and resources too far, often due to overconfidence. The case of Televerket versus Comvik instead tells a story about an incumbent monopolist with superior resources that cannot make use of or leverage its position of superiority. They cannot soar freely because of their weight, whereas Comvik seems to have been able to fly near the sun without getting burned. An inverted Icarus paradox appeared. Hence the wrong actor attained heights while not getting burned and the actor who should have risen unchallenged was unable to do so and remained passive on the ground.

There is a rather straight and consistent pattern of the type of activities practiced by Comvik and Televerket during the three battles playing out between 1981 and 1990. Comvik was mostly proactive and did not engage in any defensive activity at all. Conversely, Televerket was mostly defensive and hardly engaged in any proactive activity.

While Televerket remained passive and only responded to the requests from the government, Comvik continued to contact other government bodies, proactively trying to circumvent Televerket and build legitimacy. Televerket noticed this. In a memo sent to the staff of the Director General in 1982, the proactivity of Comvik’s strategy is discussed, and stated that Comvik had tried to portray Televerket as a ‘monopolist’ ‘charging exorbitant prices’.Footnote61

We argue that an inverted Icarus paradox better captures the behaviours described above. In this case, the Icarus actor who controlled superior resources, had unique technological capabilities, and was better connected politically but enacted a reactive and defensive strategy. Instead of making use of these capabilities, Televerket remained passive and let Comvik act as the institutional entrepreneur. The outcome was similar in the sense that the dominant incumbent lost. However, the primary reason was not flying to close to the sun, but that Televerket was put in a position where it had to remain passive and reactive, hence not flying at all. While Miller’s (Citation1990, Citation1992) original works on the Icarus paradox concerned how successful firms overreach, we observe how Televerket instead underreached.

Based on the above, we define the inverted Icarus as a pattern of strategic behaviour where a firm controls resources and possesses capabilities that makes it superior vis-à-vis competitors but still loses as it is put in a position where it cannot leverage any of its assets.

Explaining the inverted Icarus paradox

The inverted Icarus paradox can be understood by looking at different contextual and temporal situations.

To start with, we see how the paradoxical tensions between regulation and market functions internally put Televerket in an awkward position as explained by Jarzabkowski et al. (Citation2013). Televerket was both regulator of the telecommunications industry and a market actor. As the latter – including which services to offer – Televerket had significant latitude, as least long as the business generated a surplus. The regulatory tasks were managed within Televerket by a separate department; the activities were to be conducted objectively, ie the regulatory function was not allowed to particularly benefit Televerket’s commercial interests. The regulatory functions were taken over in connection with the deregulation of the telecommunications market (which took place after the period we are studying) by Post och Telecommunications Board. It is possible to imagine a counterfactual case where the regulatory function from early on was independent of Televerket. If the Swedish Post and Telecommunications Board had already existed in 1982, during the relevant period, Televerket would have been able to act significantly more offensively as a company - without the risk of being accused of using their regulatory power to benefit its commercial interests. It would also have been able to refer decisions to the independent regulatory authority. Based on this reasoning, it can be said that Televerket’s corporate form helped Comvik in the non-market domain.

This combination of tasks was crucial for how Televerket could practically act. It was virtually impossible for outsiders, the public, the media, or politicians to distinguish when Televerket was acting as a telecommunications operator or regulator. In this sense, the pattern observed by Jarzabkowski et al. (Citation2013) also applies to Televerket as paradoxical tensions between regulatory and market-related functions inhibited the organisation from taking action.

Comvik could exploit this by acting in the non-market arena and force Televerket to either act as a regulator and then appear to be acting in its interest or to refrain from acting against Comvik.

Zooming in and zooming out to explain the inverted Icarus paradox

Using the zooming in and out approach of Jarzabkowski et al. (Citation2019) we can see that the inverted Icarus paradox is still puzzling on the micro and meso-level (hence on company and sector level) but becomes more logical when one takes into account the specific situation on the macro level (hence societal level) where Televerket might have wanted to hamper the narrative in media were they were portrayed as a big arrogant monopolist. In the specific historical context, it also makes more sense since the incentives for an incumbent to be proactive are lower in a technological shift than in the environment in which they have been dominant. The inverted Icarus paradox helps us explain why an entrepreneurial firm with inferior resources may play an important role in shaping the emergence of new formal institutions under conditions of technological change. Below, we highlight interrelated factors that jointly contribute to the emergence of an inverted Icarus paradox.

As Comvik acted more swiftly and used the mass media to its advantage in ways Televerket could not cope with, a core part of Televerket’s institutional capabilities was devalued. Under conditions of rapid technological and related institutional change, incumbents engaged in regulatory capture seem to be put in a less advantageous position. Established relations, market positions, or assets are eroded rapidly since new technology alters the competitive landscape. Therefore, holding on to established assets or an institutional set-up is a strategy that may be problematic in the long run. This observation is particularly striking with the first battle round between Televerket and Comvik. Televerket kept referring to the fact that Comvik was only allowed to operate manual switches. At the same time, Comvik argued that this was unfair and unreasonable as technology had improved considerably and rendered Televerket’s argument irrelevant.

Comvik’s non-market strategies can thus be regarded as a form of effectuation (Sarasvathy, Citation2001) directed towards the regulatory framework, whereas Televerket behaved more according to a cautiousness-logic. Instead of analysing matters and drawing up extensive plans, Comvik seems to have constantly been striking, moving swiftly, while Televerket approached its adversary only after extensive internal analysis and deliberations. Televerket was hence more cautious than Comvik. Under conditions of rapid techno-institutional change, the confident effectual approach may offset an incumbent monopolist’s superior financial and relational resources, giving rise to an inverted Icarus paradox.

Our results illustrate how Televerket’s strong position as a monopolist in the market domain and as a regulator of entry into its own market paradoxically resulted in a weak non-market position.

Summary: the factors behind the inverted Icarus paradox

We observe how the different factors together contribute to the emergence of an inverted Icarus paradox. Our findings underscore that structural tensions between regulatory and more commercial functions inside a telecommunications monopoly like Televerket made the organisation passive. Beyond this explanation, we also see how temporality and institutional complexity paved the way for an inverted Icarus paradox. The 1980s was an era when government monopolies were generally questioned by public opinion. In the telecommunications sector, deregulation and privatisations had already taken place in many countries, meaning that Televerket considered itself to be in an inferior position from a global point of view. The emergence of digital technology that quickly improved also implied that established positions, rule, regulations and market positions became much more fluid. Under these circumstances, Televerket ended up in an inverted Icarus paradox where it controlled superior resources and entry into its own market, but could had to remain passive and lose out to a small and nimble entrant firm. Comvik capitalised upon general discontent with government monopolies in the 1980s.

Conclusion

This paper has aimed to explore how the Icarus paradox may unfold under conditions of interrelated technological and regulatory change.

Based on extensive digitised and database coded archival sources we have analysed the non-market activities of the challenger firm Comvik and the incumbent Televerket: Comvik faced the dual challenge of competing against a government monopoly that regulated entry into its own market while having inferior resources and limited access to technological equipment. Despite these circumstances, Comvik managed to outmanoeuvre Televerket in the non-market domain for nearly a decade.

We observe that these results present a new form of the Icarus paradox. The incumbent monopolist, Televerket, could not engage in regulatory capture but instead lost out to the entrant firm Comvik politically. The reasons for this were not primarily overconfidence and hubris. To the contrary, we argue that Televerket faced an inverted Icarus paradox, where the firm controlled superior resources but could not leverage them to sustain its political dominance. Instead, bound by its strong legacy, Televerket had to defend and react to Comvik’s nimbler political behaviour.

We explain the existence of an inverted Icarus paradox by highlighting a set of interrelated and enabling conditions. We underline the argument by Jarzabkowski et al. (2013) related to paradoxical tensions between market and regulatory functions inside a telco monopoly. Our contribution lies in pointing out the temporal circumstances that also paved the way for this inverted Icarus paradox. Using the Zooming in and Zooming out approach, we observe that the macro environment also put Televerket in a position of passivity. A general sentiment against government monopolies along with deregulation taking place in other countries put Televerket in a position where it could not leverage its assets. An entrepreneurial venture like Comvik, on the other hand, could make use of new technology to challenge the monopolist.

Although the paper is not one about the deregulation of the Swedish telecommunications market or telecommunications markets as such, both areas where there is extensive research in business history (Berg, Citation1999; Carleheden, Citation2000; Davids, Citation2005; Eliassen et al., Citation2013; Jeding, Citation2001; Karlsson, Citation1998; Mölleryd, Citation1999; Nayak, Citation2018; Nayak & MacLean, Citation2013; Nevalainen, Citation2017, Citation2018; Spiller & Cardilli, Citation1997) and on Televerket or other telecom providers (Álvaro-Moya, Citation2015; Anchordoguy, Citation2001; Clifton et al., Citation2011; Hochfelder, Citation2002; Hultén & Mölleryd, Citation2003; Huurdeman, Citation2003; Ioannidis, Citation1998; John, Citation2010; Lernevall & Åkesson, Citation1997), we also contribute to this historical literature. However, our focus is on three key episodes where the actions in the non-market domain are crucial to the market outcomes. On the micro level, we add to the previous literature also on the business history of telecommunications.

Archival sources

Mölleryd (Citation1999), Spiller and Cardilli (Citation1997), Hochfelder (Citation2002), Lernevall and Åkesson (Citation1997), Cunha Filho et al. (Citation2019), de Jong et al. (Citation2015), Decker (Citation2011), Eichenberger et al. (Citation2023), Epstein (Citation1980), Ernkvist (Citation2015), Garud and Karnøe (2003), Henderson and Clark (1990), Maclean et al. (Citation2016), Orsato et al. (Citation2002), Yates et al. (Citation2013).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (18.8 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Klas Eriksson

Klas A. M. Eriksson has a PhD in Economic History and is working as a researcher at Stockholm School of Economics. He has been guest researcher at Stanford University and Columbia University and is recipient of the Fulbright Scholarship.

Erik Lakomaa

Erik Lakomaa is associate professor in Economic History and director of the Institute for Economic and Business History Research at Stockholm School of Economics. His research primarily concerns how organisations handle external change in the form of new technologies or new regulation.

Rasmus Nykvist

Nykvist is an assistant professor in strategy at Linköping University and an affiliate researcher at the Institute for Economic and Business History Research at Stockholm School of Economics. His research focuses on areas such as corporate political strategies, state-owned enterprises and the interaction between regulation and technology.

Christian Sandström

Christian Sandström is Senior Associate Professor at Jönköping International Business School and the Ratio Institute in Sweden. His research interests concern innovation policy and the interplay between technology and industrial transformation. Sandström has co-edited the books Questioning the Entrepreneurial State (2022) and Moonshots and the New Industrial Policy (2024).

Notes

1 Miller (Citation1992, p. 24).

2 This means that we both have access to enough archival sources to answer the research questions and also probably have access to more archival documents Comvik than any previous study.

3 We acknowledge the risk that this shortcoming might have resulted in an inability to detect more reactive and anticipatory activities from Comvik since this activity is more internal than external and thus might not necessarily have been provided to Televerket.

4 All the incidents coded can be found in Appendix A.

5 The process began prior to Kinnevik’s acquisition of Företagstelefon but we have decided to only include the events after Företagstelefon was reorganized as Comvik.

6 Oliver and Holzinger (Citation2008, , p. 507).

7 All the non-market incidents and the coded categories can be found in Appendix B.

8 The coding involves a normative judgment. In those cases when non-market activities were ambiguous with regard to coding, researchers discussed the source until a consensus could be reached.

9 For a valuable description of the deregulatory process and also the market competition between Televerket and Comvik, see Karlsson (Citation1998). The market competition aspect is, in the context of this paper, less interesting since Televerket never was threatened in the commercial domain.

10 Mölleryd (Citation1999, p. 97). In 1971, there were 13 such networks. In 1980, the year before Comvik launched 1G mobile telephony in Sweden Televerkets MTD had 19,687 subscribers and Comvik (1900). See Karlsson (Citation1998, p. 225).

11 In 1979 Svensk Kommunikationskonsult acquired the telecom operator Telelarm and renamed the company Företagstelefon, in 1980 they merged with the other remaining private mobile telephone company Nordiska Biltelefonväxeln AB. Företagstelefon had obtained this permission from Televerket in 1968.

12 Mölleryd (Citation1999, p. 100).

13 Mölleryd (Citation1999, pp. 89–90 and 94).

14 Mölleryd (Citation1999, p. 100).

15 Mölleryd (Citation1999, p. 100).

16 See Helgesson (Citation1999), Lernevall and Åkesson (Citation1997), Eriksson et al. (Citation2019).

17 Friedl and Lakomaa (Citation2022). See also Nevalainen (Citation2018).

18 Letter: Hagström till Comvik ang Automatisk anslutning av radionät till det allmänna telefonnätet, dnr 381/81, aktbil 5a, 10-01-1981, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17,

(Source ID 9141).

19 Letter: Företagstelefon AB till Televerket tekniska avdelningen ang investering i automatiska radioväxlar, Rydax, No dnr 381/81, aktbil 5d, Televerket Frekvensförvaltningen, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID 9390).

20 Memo Telefonanslutning av landmobila radionät som ej tillhör televerket. Villkor A 055-2000, (05-52000-1), 1980-09-05, Näringsfihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source 9483).

21 Minutes, Frekvensförvaltningen ang Företagstelefon AB:s telefonanslutningstillstånd, 16 September 1981, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID 9393).

22 Automatic switches existed and had been in use since the 1950s. Televeket had operated an automatically switched system but only with a very small number of users. See Mölleryd (Citation1999, p. 76). See also PM: Utvecklingsfaser hos förmedlingsföretag fram till Comvik AB, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:4 (source ID 10380) which likely is one of Mölleryds sources, and Yttrande: Televerket ang besvär från Comvik över televerkets beslut ang mobiltelefonsystem, dnr II 1898/81, 1981-10-14, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9161) where it is mentioned that Televerkets automatically switched system had 600 subscribers (compared to 20,000 in the manual system).

23 Letter: Företagstelefon AB till Televerket ang Besvär över beslut 80-10-13, beteckning Rm 35/80, NO dnr 381/81 aktbil 5, 1980-12-12, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen tillstånd, mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID 9373).

24 They had approved the switch in a semi-automatic form, but later claimed that the functionality that Comvik used required a renewed approval process. Yttrande: Televerket ang besvär från Comvik över televerkets beslut ang mobiltelefonsystem, dnr II 1898/81, 1981-10-14, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9161).

25 Letter: Företagstelefon AB/Comvik till Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen ang konkurrensbegränsande beslut från televerket, dnr 381/81, aktbil 1, 1981-09-23, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, Televerket Radio, (Source ID: 9143), Letter: Comvik till Malmgren ang tillstånd nya växlar, 1981-09-22, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID: 9392), Mötesanteckningar, Frekvensförvaltningen ang Företagstelefon AB:s telefonanslutningstillstånd, 16 September 1981, 1981-09-16, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID: 9393).

26 Mötesanteckningar, Frekvensförvaltningen ang Företagstelefon AB:s telefonanslutningstillstånd, 16 September 1981, 1981-09-16, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID: 9393). Letter: Larsson till Comvik ang Tillstånd för anslutning av radioväxel typ Rydax RCT-3/S, dnr 381/81, aktbil 2c, 1981-09-25, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID: 9147). Press clipping: Bilradiostriden blir fall för NO (Arbetsmaterial NO dnr 381/81), 1981-09-24, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID: 9502).

27 Yttrande: Televerket ang besvär från Comvik över televerkets beslut ang mobiltelefonsystem, dnr II 1898/81, 1981-10-14, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9161), Televerket must have realized the weakness in this argument since they themselves used an automatic switching system. In a previous notification, Televerket also had stated that the motives for limiting access were “to protect the network from interference. To restrict private radio [mobile telephony] networks so that customer demand could be consolidated in rational systems which then could be built also in less profitable localities. To promote rational use of equipment and frequencies. Communication radio [PTT, half duplex like walkie talkies and CB radios] on average only uses the radio frequency for a very short time, while connections to the telephone network would increase use significantly. To create a good environment by limiting the number of radio facilities and antennas”. Memo: Telefonanslutning av landmobila radionät som ej tillhör televerket. Villkor A 055-2000, (05-52000-1), 1980-09-05, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID 9483). None of those were applicable to the issue of automatic vs manual switches.

28 Letter: Företagstelefon AB/Comvik till Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen ang konkurrensbegränsande beslut från televerket, dnr 381/81, aktbil 1, 1981-09-23, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9143), Brev: Comvik till Malmgren ang tillstånd nya växlar. 1981-09-22, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID 9392).

29 Letter: Comvik till Malmgren ang tillstånd nya växlar. 1981-09-22, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID 9392).

30 Press clipping, Dagens Nyheter: Bilradiostriden blir fall för NO (Arbetsmaterial NO dnr 381/81), 1981-09-24, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID 9502).

31 Letter: Larsson till Comvik ang Tillstånd för anslutning av radioväxel typ Rydax RCT-3/S, dnr 381/81, aktbil 2c, 1981-09-25, Televerket, Televerket Radio NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9147).

32 Letter: Tengroth till NO ang anmälan från Comvik AB ./. Televerket, dnr 381/81, aktbil 4a (b), 1981-10-02, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID: 9477). Besvär från Comvik AB över beslut från Televerket ang mobiltelefonsystem, dnr II 1898/81, (NO dnr 381/81, aktbil 5b), 1981-10-06, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID. 9196). Nyhetsartikel: Regeringen kopplas in i telestriden (Arbetsmaterial NO dnr 381/81), 1981-10-08, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID: 9494).

33 Letter: Hagström till Comvik ang Automatisk anslutning av radionät till det allmänna telefonnätet, dnr 381/81, aktbil 5a, 1981-10-01, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, Televerket Radio (Source ID 9141). Yttrande: Televerket till Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen ang nät, Televerkets tillståndsgivning, dnr 381/81, aktbil 7, 1981-10-12, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, (Source ID 9138), Yttrande: Televerket ang besvär från Comvik över televerkets beslut ang mobiltelefonsystem, dnr II 1898/81, 1981-10-14, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9161), Letter: Hagström till Comvik ang Förhandling mellan televerket och FTAB, 1981-10-20, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9193), Press clippings Veckans affärer, Ny teknik trasslar till det för televerket/Vi har ju själva föreslagit en avgränsning av monopolet 1981-11-12, Televerket, Tony Hagströms arkiv, F1: Pressklipp, 1977–1993 (Source ID 9286), Interview Baromtern,: Hagström: Delikat balansgång att vara myndighet och driva affärer, 1981-12-21, Televerket, Tony Hagströms arkiv, F1: Pressklipp, 1977–1993 (Source ID 9285). 5.

34 Letter Comvik till Hagström ang besvär av beslut, dnr 381/81, aktbil 2e, 1981-09-30, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID 9476).

35 Letter: Hagström till Comvik ang Automatisk anslutning av radionät till det allmänna telefonnätet, dnr 381/81, aktbil 5a, 1981-10-01, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, Televerket Radio (Source ID 9141).

36 Letter: NO Begäran om yttrande ang monopol - mobiltelefon, dnr 381/81, aktbil 3, 1981-10.01, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, Televerket Radio.

(Source ID 9142).

37 Newsarticle: Comvik segrade i biltelefonstriden (Arbetsmaterial NO dnr 381/81), 1981-12-23, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID 9493), Regeringsbes lut: Komm.dep. till Comvik ang Besvär i fråga om tillstånd att ansluta radioanläggning till telefonnätet, dnr II 1898/81 (NO dnr 381/81, aktbil 12), 1981-12-22, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17 (Source ID 9166).

38 Letter: Televerket till regeringen: Bil 1 Protokoll, LG-möte 27 januari 1986: Till Statsrådet ang Ansökan om tillstånd enligt radiolagen från Comvik Skyport AB, (NO-dnr: 482/86, aktbil: 1d). 1986-01-23, Televerket, Marknadsavdelningen, Marknadsavdelningen ledningsgrupprotokoll, Televerket, A1a:1, 1985-86 (source ID 5347). This is more in line with the previous claims on the rational for restricting entry. Memo: Telefonanslutning av landmobila radionät som ej tillhör televerket. Villkor A 055-2000, (05-52000-1), 1980-09-05, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, NO-ärenden, F1:832 (Source ID 9483).

39 PM Kommunikationsdepartementet: Förslag till handläggning av Comvik Skyport-ärendet, Arbetsmaterial NO dnr 482/86, 1985-02-21, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1:1191.

(Source ID 9560).

40 Supplement to letter: Vinge till Komm.Dep: Inlaga från Comvik Skyport AB till regeringen i ärende dnr II 145/86 (NO dnr 482/86, Aktbil: 1e) section 5.4, 1986-03-26, Televerket, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, (Source ID 9173)., Section 5.2.

41 Supplement to letter: Vinge till Komm.Dep: Inlaga från Comvik Skyport AB till regeringen i ärende dnr II 145/86 (NO dnr 482/86, Aktbil: 1e), 1986-03-26, Televerket, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, (Source ID 9173). section 5.4.

42 Letter: Televerket till Comvik ang Er ansökan om tillstånd enligt radiolagen, dnr II 145/86 (NO-dnr 482/86), 1986-10-23, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1:1191.

(Source ID 9519).

43 Letter: Adv.firman Vinge till Kommunikationsdepartementet ang Ansökan från Comvik Skyport om tillstånd enl radiolagen, NO-dnr: 482/86, aktbil 1b, 1986-12-22, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1:1191 (Source ID 9515).

44 Regeringsbeslut: Skrivelse ang ansökan från Comvik Skyport AB om tillstånd enl radiolagen, dnr II 145/86 (NO-dnr 482/86, aktbil 1e), 1986-09-25, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1:1191 (Source ID 9518) 8.

45 Letter: Televerket till Comvik ang Er ansökan om tillstånd enligt radiolagen, dnr II 145/86 (NO-dnr 482/86),1986-10-23, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1:1191 (Source ID 9519).

46 Letter: Advokatfirman Vinge till Näringsfrihetsombudmannen ang Anmälan om otillbörlig konkurrensbegränsning, dnr 482/86, aktbil 1a (h), 1986-12-23, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1:1191 (Source ID 9514).

47 Regeringsbeslut: Kommunikationsdepartementet till Televerket ang Ansökan om frekvenser för mobiltelefonverksamhet, dnr II 678/86, 1987-06-18, Televerket, Frekvensförvaltningen, tillstånd Mobiltelefonsystem, F4EE:7 (Source ID 9364).

48 Letter: Ericsson till Comvik ang Offertförfrågan GSM-system, NO-dnr 308/89, aktbil 1.5 1989-08-30, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1A:104 (Source ID 9759). 9.

49 Letter: Johannesson till Hagström ang Ericssons offertvägran, NO-dnr 308/89, aktbil: 2.2, 1989-09-18, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1A:104 (Source ID 9757).

50 Letter: Hagström till Johannesson Re: ang Ericssons offertvägran, NO-dnr 308/89, aktbil: 2.3. 1989-09-28, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1A:104 (Source ID 9760).

51 Press clip: Svenska Dagbladet, 1989-09-19 Nils-Olof Ollevik” Ericsson avvisar Comvik. Televerket blir enda svenska kunden”. Näringsfrihetsombudsmännen NO, NO-ärenden, F1A:104 (Source ID 9775).

52 Supplement to letter: Vinge till Komm.Dep: Inlaga från Comvik Skyport AB till regeringen i ärende dnr II 145/86 (NO dnr 482/86, Aktbil: 1e), 1986-03-26, Televerket, Televerket Radio, NMT - Mobiltelefoninätet, Comvikaffären, F4C:17, (Source ID 9173). section 5.4.

53 Letter: Advokatfirman Vinge till NO ang Leverans av mobiltelefonsystem för GSM, dnr 308/89, aktbil: 1.1(5), 1989-09-26, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1A:104 (Source ID 9753).

54 Notes: Sammanträde med Comvik AB och Ericsson Radio Systems AB ang Offertvägran betr mobiltelefonsystem, dnr 308/89, aktbil: 3 1989-10-06, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1A:104 (Source ID 9761).

55 Mötesanteckningar NO med Comvik, Ericsson och televerket, dnr 308/89, aktbil 18, 1989-12-22, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen NO, NO-ärenden, F1A:104 (Source ID 9789).

56 Utlåtande: Ang Ericssonkoncernens vägran att lämna offert till Comvik, NO-dnr 308/89, aktbil 12.2, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1A:104, (Source ID 9781).

57 The market court (“Marknadsdomstolen”) was a Swedish special court for competition and marketing cases in service 1972–2016. Only businesses, organizations and public authorites could file cases to the market court.

58 Prövningsansökan: Näringsfrihetsmannen mot Ericsson och Televerket ang Diskriminering - mobiltelefonmarknaden, dnr 308/89, aktbil 36, Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1A:104, 385 (Source id 9809).

59 Regeringsbeslut 1990-02-08: Framställning om åtgärder betr leverans av viss utrustning mm, dnr II 2272/89 [NO-dnr 308/89, aktbil 23], Näringsfrihetsombudsmannen, NO-ärenden, F1A:104, 385 (Source id 9795).

60 Tidningarnas telegrabyrå 1991-01-16 ” Comvik ger upp striden mot Televerket”. In the telegram it is also mentioned that the reason for not delaying further was the prospective entry by another mobile operator in Sweden, Nordic Tel. Howvever, Ericsson/Televerket also refused to sell equipment to them. Tidningarnas Telegrambyrå 1991-05-28 “Nordic Tel får inte köpa AXE-växlar”.

61 Memo from Bertil Thorngren titeld “Comvik” 1982-08-05. Televerket, Televerket Radio, NMT-Mobiltelefoninaätet, Comvikaffären, 362 (Source ID 9180).

References

- Acemoglu, D., & Robinson, J. A. (2006). Economic backwardness in political perspective. American Political Science Review, 100(1), 115–131. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055406062046

- Aldrich, H., & Fiol, C. M. (1994). Fools rush in? The institutional context of industry creation. The Academy of Management Review, 19(4), 645–670. https://doi.org/10.2307/258740

- Álvaro-Moya, A. (2015). Networking capability building in the multinational enterprise: ITT and the Spanish adventure (1924–1945). Business History, 57(7), 1082–1111. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1014901

- Amason, A. C., & Mooney, A. C. (2008). The Icarus paradox revisited: How strong performance sows the seeds of dysfunction in future strategic decision-making. Strategic Organization, 6(4), 407–434. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476127008096364

- Anchordoguy, M. (2001). Nippon telegraph and telephone company (NTT) and the building of a telecommunications industry in Japan. Business History Review, 75(3), 507–541. https://doi.org/10.2307/3116385

- Ashforth, B. E., & Reingen, P. H. (2014). Functions of dysfunction: Managing the dynamics of an organizational duality in a natural food cooperative. Administrative Science Quarterly, 59(3), 474–516. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839214537811

- Berg, A. (1999). [Staten som kapitalist: marknadsanpassningen av de affärsdrivande verken 1976–1994] [Doctoral dissertation]. The State as a Capitalist: commercialization of state enterprises 1976–1994. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Buchanan, J. M. (1980). Rent seeking and profit seeking. In J. M. Buchanan & G. Tollison (Eds.), Toward a theory of the rent-seeking society (pp. 3–15). Texas A&M University Press.

- Buysse, K., & Verbeke, A. (2003). Proactive environmental strategies: A stakeholder management perspective. Strategic Management Journal, 24(5), 453–470. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.299

- Carleheden, S. B. (2000). Telemonopolens strategier: En studie av telekommunikationsmonopolens strategiska beteende vid liberalisering av teleoperatorsbranschen. The strategies employed by Telecommunications monopolies: a study of the strategic behavior of telecommunications monopolies’ under conditions of liberalization.

- Cheung, Z., Aalto, E., & Nevalainen, P. (2020). Institutional logics and the internationalization of a state-owned enterprise: Evaluation of international venture opportunities by telecom Finland 1987–1998. Journal of World Business, 55(6), 101140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2020.101140

- Christensen, C. M. (1997). The innovator’s dilemma. Harvard Business School Press.

- Clifton, J., Comín, F., & Díaz-Fuentes, D. (2011). From national monopoly to multinational corporation: How regulation shaped the road towards telecommunications internationalisation. Business History, 53(5), 761–781. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2011.599588

- Cunha Filho, M., Herrero, E., Mello, C., & Vidal, D. (2019). Ascensão e Declínio De Empresas De Sucesso: Estudo bibliométrico sobre o paradoxo de Ícaro. Revista Ibero-Americana de Estratégia, The Rise and Fall of Successful Firms: A Bibliometric Study of the Icarus Paradox. 18(1), 139–154. https://doi.org/10.5585/ijsm.v18i1.2741

- de Jong, A., Higgins, D. M., & van Driel, H. (2015). Towards a new business history? Business History, 57(1), 5–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2014.977869

- Davids, M. (2005). The privatisation and liberalisation of Dutch telecommunications in the 1980s. Business History, 47(2), 219–243. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007679042000313666

- Decker, S. (2011). Corporate political activity in less developed countries: The Volta river project in Ghana, 1958–66. Business History, 53(7), 993–1017. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2011.618223

- Eichenberger, P., Rollings, N., & Schaufelbuehl, J. M. (2023). The brokers of globalization: Towards a history of business associations in the international arena. Business History, 65(2), 217–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2022.2112671

- Eliassen, K. A., Nfa, M. S., & Sjovaag, M. (2013). European telecommunications policies—deregulation, re-regulation or real liberalisation?. In K. A. Eliassen, M. S. Nfa, & M. Sjovaag (Eds.), European telecommunications liberalisation (pp. 34–44). Routledge.

- Epstein, E. M. (1980). Business political activity: Research approaches and analytical issues. Research in Corporate Social Performance and Policy, 2, 1–55.

- Ernkvist, M. (2015). The double knot of technology and business-model innovation in the era of ferment of digital exchanges: The case of OM, a pioneer in electronic options exchanges. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 99, 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2015.02.001

- Eriksson, K., Ernkvist, M., Laurell, C., Moodysson, J., Nykvist, R., & Sandström, C. (2019). A revised perspective on innovation policy for renewal of mature economies–Historical evidence from finance and telecommunications in Sweden 1980–1990. Technological Forecasting and Social Change, 147, 152–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techfore.2019.07.001

- Friedl, C., & Lakomaa, E. (2022). Monopolist logic? Managing technology in the telecom sector during technological and regulatory change. Business History, 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2022.2064851

- Garud, R., Jain, S., & Kumaraswamy, A. (2002). Institutional entrepreneurship in the sponsorship of common technological standards: The case of Sun Microsystems and Java. Academy of Management Journal, 45(1), 196–214. https://doi.org/10.2307/3069292

- Glynn, M. A., & D’Aunno, T. (2023). An intellectual history of institutional theory: Looking back to move forward. Academy of Management Annals, 17(1), 301–330. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2020.0341

- Helgesson, C. F. (1999). [Making a natural monopoly: The configuration of a techno-economic order in Swedish telecommunications] [PhD dissertation]. Stockholm School of Economics.

- Henrekson, M., & Sanandaji, T. (2011). The interaction of entrepreneurship and institutions. Journal of Institutional Economics, 7(1), 47–75. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137410000342

- Hochfelder, D. (2002). Constructing an industrial divide: Western Union, AT&T, and the federal government, 1876–1971. Business History Review, 76(4), 705–732. https://doi.org/10.2307/4127707

- Hultén, S., & Mölleryd, B. (2003). Entrepreneurs, innovations and market processes in the evolution of the Swedish mobile telecommunications industry. In J. S. Metcalfe & U. Cantner (Eds.), Change, transformation and development (pp. 319–342). Physica-Verlag HD.

- Huurdeman, A. A. (2003). The worldwide history of telecommunications. John Wiley & Sons.