Abstract

Hillards was a retail supermarket firm based in Yorkshire in the North of England between 1885 and 1987, when it was subject to a hostile takeover from Tesco. Using archival and interview data this article explores how Hillards pursued a sensemaking process to engage in a strategy of counter-hostility to the takeover attempt. Ultimately the firm was acquired by Tesco. By examining Hillards’ defence strategy, this paper contributes to the understanding of the nature of strategy-making within a takeover. The article shows how in defeat Hillards was able to secure a partial victory in the form of a substantially increased cost of acquisition, so maximising shareholder value. This contributes to the history of the supermarket sector, and the history of family firms in the UK.

Introduction

Hillards was a retail supermarket firm based in Yorkshire in the North of England between 1885 and 1987. The company was founded by John Wesley Hillard who passed it on to his son-in-law, Percy Hartley, in 1935. Percy Hartley ran the business until 1951 when he passed control onto his son David Hartley who was then joined by Percy’s other son Peter Hartley in 1955. David Hartley retired from the company on health grounds in 1977, leaving Peter as the only member of the family in a senior management role. Peter Hartley remained as managing director until 1983 when he took up the role of executive Chairman, a position he held until the takeover of the company by Tesco in 1987.Footnote1 The business was predominantly owned by family members as a private firm until 1972, when a public offering was made. The firm expanded through the 1960s and 1970s becoming an established regional chain. Hillards mainly operated in the North of England, predominately in Yorkshire. In its own terms, Hillards was a reasonably successful regional firm. In 1986 the firm reported a turnover of £281 m, a rise of approximately £25 m from the previous year, and roughly double its 1980 turnover. Group profits before taxation were £8.5 m.Footnote2 The firm was also expanding its number of stores and store size at this time.Footnote3 However, the view of the Financial Times was that though ‘[i]n many ways Hillards is doing the right things … [the] problem is that they are doing them three years too late’.Footnote4 Hillards had thus been considered as a potential takeover target for some time, as was widely reported in the financial press.Footnote5

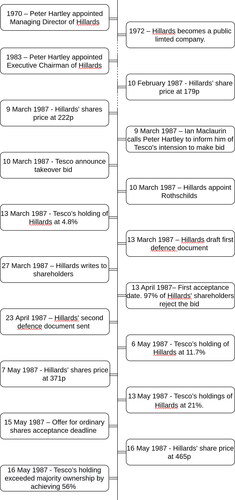

The 1980s were a period of consolidation in the UK supermarket retail sector, the end result of which was a largely oligopolistic structure with a few large nationally well-known chains (Ford, Citation2018). One of those chains was Tesco, whose expansive strategy in the 1980s, alongside internal growth, was to acquire regional supermarket chains to develop a national presence (Clark & Chan, Citation2014). The then Chairman of Tesco, Sir Ian MacLaurin (later Baron MacLaurin), observed that Tesco had concentrated its operations in the South and Midlands of England, and in Wales, and ‘had found it exceptionally difficult to obtain planning consents in Yorkshire and the North East’Footnote6 and that ‘[i]n location terms, Hillards was ideally positioned to extend Tesco’s trading area into Yorkshire and the East Midlands’.Footnote7 Consequently, in the summer of 1987 Hillards became a target for, and was eventually acquired by, Tesco after a hostile takeover battle. This was the first hostile takeover in the UK supermarket retail sector.Footnote8 Within months of being acquired the Hillards brand had disappeared, and all of the senior management of the firm had been released. The comparative geographical location of Tesco vs Hillards stores can be seen in .

Figure 1. Map showing the distribution of Hillards and Tesco stores in 1986. Produced by Tesco in Tesco Company Review page 5, 1986 (the colour of the dots representing Hillards stores was changed from light grey to purple for visual clarity).

In this article we use this episode to explore how an acquisition target firm—Hillards—reacted to a sudden and unforeseen external existential threat of being the subject of a hostile takeover by a large organisation such as Tesco which had a plausible chance of success. This allows us to explore how the firm formulated its strategy while under considerable pressure. We examine how that strategy was made and implemented, and why, ultimately, it failed to prevent the takeover, but succeeded in maximising shareholder value. We argue that this strategy was one of counter-hostility, shaped around various attempts at resisting the takeover. It was necessarily reactionary, a forced response to a conflict that the firm had neither sought nor anticipated. The ‘hostility’ in a takeover comes from the strategic choices of both buyer and target firms as they seek to maximise their respective gains within the process (Schwert, Citation2000). Hillards demonstrated strategic counter-hostility through shareholder, media and regulatory campaigns that were designed to establish the plausibility of Hillards remaining an independent operation. We argue increased the cost of acquisition and ultimately shareholder value.

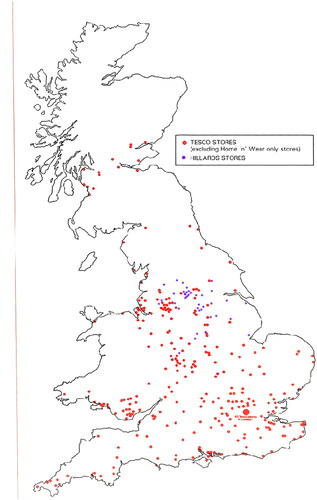

This article is structured as follows. Following a review of the relevant literature and discussion of methods, we first of all examine the strategy-making process during the takeover as a form of organisational sensemaking. The following sections then look at the different campaigns mounted by Hillards as part of their defensive strategy, focusing respectively on the media, regulatory authority, and the shareholders. We then conclude by exploring the three main areas of contribution. First, we argue that Hillards’ strategy of counter-hostility secured increased value for Hillards’ shareholders. Second, that Hillards developed their strategy in the takeover by engaging in a process of strategic and organisational sensemaking. And third, we comment on the nature of economic power held by the larger supermarket retailers that was emergent and this time, contrasting regional and national, as well as family run and monopolistic ambitions within the sector. A timeline of key events is presented in diagram form in .

Literature review

The historiographical context for this article is the history of UK supermarket retail in the mid to late twentieth century. This period–circa 1976–1994–was known as the ‘golden age’ of supermarket retailing (Morelli, Citation2007), so called because of the ‘extraordinary rise and transformation of corporate power’ that resulted in the creation of a small number of very large supermarket retailers (Wrigley, Citation1991, p. 1537). UK grocery retail had been transformed in the post-war period by the advent of self-service and economies of scale achieved by increasing number of retail outlets. There was a shift in organisational form from traditional grocery shops to large-scale self-service stores underpinned by increasingly sophisticated techno-managerial systems (Alexander et al., Citation2005; Shaw et al., Citation2004). This enabled supermarket chains to exhibit substantial oligopsonistic buyer-power from the 1970s onwards (Alexander, Citation2008; Bailey & Alexander, Citation2019; Shaw et al., Citation2004) Consequently, by the 1980s there was increasing centralised managerial control of supermarket chains, so increasing the importance of strategic decision-making in the sector (Alexander, Citation2015). This transformation was accompanied by a dramatic increase in economic power among large retailers who were increasingly able to sculpt the industry-sector to their own interests, in so doing overcoming concerns in relation to competition and regulation (Morelli, Citation2004, Citation2007).

This move to scale was part of a process that transformed regional family-run retailers such as Tesco and Sainsbury’s into national corporate behemoths at the expense of other family-run firms such as Hillards, many of which were acquired. The literature highlights a tension between the national-level brand development, marketing strategies, distribution and retailing on the one hand, and local or regional knowledge of customers and suppliers on the other (Alexander, Citation2015). In the case of Tesco’s acquisition of Hillards this is germane both to the strategic logic of the acquisition for Tesco (to increase the scale and scope of their network of stores), and the strategic logic and defensive narrative of Hillards on the other (that local knowledge and a ‘Yorkshire’ business culture were essential to the success of the company). The experience of Hillards will allow us to explore the creation of these oligopolistic structures from a different perspective (that of a target firm), and to contribute to the wider debate about the role of shareholder value maximisation and its relationship to different visions of who should control a corporation and for what purpose (Krippner, Citation2005; Lapavitsas, Citation2011; Lazonick & O’Sullivan, Citation2000; Williams, Citation2000). Specifically, the article contributes to the debate about whether unsuccessful defences help maximise shareholder value (Clarke & Brennan, Citation1990).

The second frame for this article is the nature of corporate takeovers and how they should be problematised, interpreted and narrated. There is an emerging literature on cases of organisational demise that examine the experiences of organisations and actors that in simple narrative terms are not ‘successful’ because they ceased as independent entities, but nevertheless were viable businesses (see for example Tennent & Mollan, Citation2020). This study contributes to this perspective by moving away from deterministic accounts of organisational success by dominant firms to one where the position, role and narrative of a firm on the brink of its own end is considered. Hillards was targeted for takeover not because it was in of itself failing as a business, but rather that it offered a good opportunity for expansion by another firm, which is consistent with one of the main drivers of merger and acquisition activity (Kolev et al., Citation2012). Though the defence of the firm was in this case ultimately unsuccessful, the process of formulating and implementing the defensive strategy is an interesting and rare example that enables reflection from the perspective of the ‘losers’ in the process, which is otherwise dominated by literature which reflects on the relative desirability and/or practicalities of undertaking M&A activity from the perspective of the acquiring firm (Cartwright & Cooper, Citation2012; Kolev et al., Citation2012). The literature of the role of the CEO in a hostile takeover suggests that they play pivotal role, but that this role can be conflicted by having to mediate between their own interests as CEO and those of the shareholders (Angwin et al., Citation2004). This is further complicated by the ‘family’ narrative of the firm in question in this study, and the CEO’s role as a custodian of the family heritage of the firm. The history of family firms is an important subfield within the field of business history to which this project will also contribute (Colli et al., Citation2013; Colli & Larsson, Citation2014; Holt & Popp, Citation2013). One novelty of the research here is that unlike the bulk of the historical research into family firms it covers a comparatively recent period, and can be used to challenge more deterministic accounts of the durability of family structures in ensuring long-run success for family businesses (Jones et al., Citation2013) by pointing to their vulnerability to takeover when ownership has become diffuse and is publicly traded. Following this, the article will also contribute to the literature on the corporate governance of family business (Pindado & Requejo, Citation2014) and issues related to agency and stewardship (Dodd & Dyck, Citation2015; Siebels et al., Citation2012).

Methods and sources

This article is a case-study of one firm (Eisenhardt, Citation1989; Eisenhardt & Graebner, Citation2007; Yin, Citation1994), and is informed by temporal approaches to researching change in business organisations (Bucheli & Daniel Wadhwani, Citation2013; Maclean et al., Citation2016; Rowlinson et al., Citation2014). Most of the data for this study was generated using archival sources according to the conventions of document-analysis and historical research (Bowen, Citation2009; Lee, Citation2012; Marwick, Citation1970). Such corporate records are a means of accessing data about the past and allow events to be traced over time (Decker, Citation2013).

Corporate archives are usually maintained only by large survivor firms, or are retained in public archives as a consequence of the perceived importance of the firm in question (Turton, Citation2017). Tesco’s corporate archive claim they have no records relating to Hillards at all. More surprisingly, perhaps, they also state they have no record that Hillards was ever acquired by Tesco.Footnote9 There are no records of Hillards in any public archive, although there is material published on the takeover in the Financial Times as well as a popular nostalgic memory of Hillards in the public imagination, as seen in the Hillards Appreciation Society Facebook group. However, the personal papers of Peter Hartley in relation to aspects of his role in Hillards have survived, and have been partly digitised as part of a heritage preservation project. Hartley had been managing director of Hillards from 1970. In 1983 he took up the role of executive Chairman, a position he held until the takeover of the company by Tesco in 1987.Footnote10 These documents were used as the primary data for this research. The bulk of the archival materials that were digitised cover the final years of the firm, largely generated by the (unsuccessful) defence that the firm made to the hostile takeover by Tesco. Similar use of defence documents has been previously undertaken in studies of takeovers (Brennan et al., Citation2010).Footnote11

This has been supplemented by qualitative interviews with two key protagonists, specifically Peter Hartley, and Ian MacLaurin, Baron MacLaurin of Knebworth, who was Chief Executive of Tesco at the time of the takeover. These interviews were carried out in accordance with the ethical standards and practice norms of the Oral History Society (Oral History Society, Citation2015) and use of memory studies in management research (Decker et al., Citation2020).

The events narrated in this article took place over 35 years ago. Consequently, there is a natural limit on the number of interviewees that were available for this research. One interview was conducted with Ian MacLaurin, which lasted approximately 45mins. In total eight interviews were conducted with Peter Hartley, two of which were focused on the takeover of Hillards by Tesco and were 1 hour in length each. No other members of the board of Hillards were available for interview. One surviving previous member was contacted but not interested in participating in the research, all others are either no longer alive or unavailable for other reasons. One other general manager of Hillards was interviewed as part of the larger project but was not employed by Hillards at the time of the takeover.

Strategy sensemaking and formulating a defence

In this section we explore the formulation of Hillards’ defence strategy, drawing on organisational sensemaking. Weick (Citation1995) identifies seven properties of sensemaking, of which three are particularly relevant to interpreting Hillards’ sensemaking activities. First, Hillards were attempting to retrospectively understand the competitive position and strategy of their own firm. Second, the sensemaking was driven by a desire to establish a plausible account of the firm that would support their claims to remain independent. And third, their sensemaking was grounded in identity construction, in particular drawing on the themes of regionality and uniqueness in being from, and reflecting the culture and society of, Yorkshire. Their ‘Yorkshire’ identity became focal point in the media campaign carried out by Hillards as part of their defence.

In addition, Weick (Citation1995) notes that sensemaking tends to be swift, and that researchers do not often see the process of sensemaking itself. In this case, however, this process can be seen unfolding in the development of the defence documents by the senior management of Hillards in collaboration with Rothschilds, as they worked from the initial drafts to the final published version.

The events that led to the attempted takeover of Hillards began by six months of secret preparation by Tesco, examining all aspects of the firm and its performance.Footnote12 But from the perspective of Hillards, the events of the takeover began when Ian MacLaurin telephoned Peter Hartley on 9 March 1987 to inform him that Tesco were going to make an offer for Hillards the following day. In an interview conducted as part of this project, Hartley reported his immediate response to MacLaurin as follows:

So, I said ‘well its very kind of you Ian to give me so such much notice, but if you do make a bid you’ll get a bloody nose, goodbye’.Footnote13

At this point Hillards’ strategic options were limited. The family no-longer owned or controlled a majority of shares, and had insufficient funds available for reacquisition. Poison pill defences were (and remain at the time of writing) prohibited by the City Code on Takeovers that had been introduced in 1968 and governed the rules under which takeovers were conducted (Johnston, Citation2007). Therefore, once the intention to acquire has been made by Tesco, to resist the takeover the Hillards’ management needed to persuade the shareholders to vote against the acquisition. Such bid defences are recognised as being of importance to the formulation of strategy in takeovers (Schoenberg & Thornton, Citation2006). To do this, Hillards planned to issue shareholders with defence documents, making the case for rejection of the Tesco bid. In merger and acquisition processes this is usually undertaken in combination with the firm’s investment/merchant banker. But for Hillards this posed an immediate problem, because they were informed that their regular merchant bank–Kleinwort Benson–had undertaken work for Tesco in the previous three months. This would be a direct conflict of interest because Kleinwort Benson had been given access to confidential information by Tesco. This forced Hillards to commission Rothschilds–who had not previously worked with Hillards–to undertake this work.Footnote17 Having no prior knowledge of Hillards, Rothschilds had to develop an understanding of the company in the process of drawing up the defence documents. As such, then, the defence documents were an iterative learning process for both Hillards and Rothschilds, and as such embedded sensemaking into the defence from the outset.

The defence documents produced were, in effect, direct and targeted marketing to the shareholders to reject the Tesco offer. The different iterations of the defence documents represent a textual record of the firm’s sensemaking of their position and, indeed, their strategy. What emerged from the language of this sensemaking process was the need for Hillards to understand its identity, strategic position, and possible actions in response to the ‘interruption’ of an unexpected bid. Hillards found itself asking what it was going to do next both in terms of an emergent defence and as an explicit long-term business strategy. In what follows, we analyse the defence documents as texts: what they say about the firm, and what they say about the internal discourse and dialogues within the firm at this time. The draft defence documents are interesting for what they say and don’t say, what the editorial marginalia reveal, and how the Hillards strategy was ‘talked into existence’ through the communication of the defence documents with the shareholders (Weick et al., Citation2005).

Initially, the firm seemed uncertain of their strategic strengths. The first draft defence document (13 March 1987) begins by highlighting the five year record of the firm in terms of sales, profits, margins, dividends, store openings, physical expansion, adoption of information systems, and so on, but without detail or evidence. In the margin, an unknown author writes ‘What have we done to improve the business?’ This is part declamation and part exhortation. This is then followed by an articulation of the perceived strategy of the firm, as follows:

‘Improvement of merchandise mix and product innovation (health foods, bakery)’

‘survey of consumer price competitiveness in region especially versus T[esco]’

‘current expansion plans; 3 new stores plus any other sites owned/identified’

‘reasons for H[illards] success in site identification versus problems experienced by T[esco]’

‘central distribution; physical and cost efficiency on the H[illards] programme’.Footnote18

Of these, (2), (4) and (5) are arguably not strategies at all, though they might be sources of competitive advantage for the firm as they are concerned with areas Hillards believed were organisational strengths. The other points – (1) and (3) - to a greater extent communicate a strategy for the firm (to innovate and to expand respectively). However, taken as a whole this document reveals that going into the takeover episode the firm had only a limited documented understanding of its own strategy. If anything, the understanding of Hillards’ strategy by managers was largely tacit and/or emergent (Mintzberg & Waters, Citation1985). This is highlighted by the reaction by Peter Hartley to the accusation by Rothschild that no corporate strategy existed.

The snag was of course Rothschild didn’t know anything about Hillards so they sent somebody up to get some details and it was one evening a few days later and it was probably half past ten or eleven at night…and there were a lot of us working in the office plus this young chap from Rothschilds and…we were having a tea break I think …and he was in the old boardroom and I happened to walk in, look at what he’d written and one of the things he’d written was Hillards had no strategy, which rather both amused me and incensed me. So, anyway I put this to him he got very upset said he should not be reading his private notes…I spoke to Rothschilds the following day and we never saw him again. And had he actually even bothered to look at our recent reports and accounts he would have seen there what our strategy was, anyway.Footnote19

An early second draft defence document (based on the original draft but with significant changes and additions) described the ‘long-term’ strategy of Hillards as being ‘how a regional operator can prosper’, ‘site availability, purchasing power, distinctive marketing formats’, ‘scope for expansion of national market share versus T[esco]’s mature market position’, ‘scope for improvement in margins and volume via expansion of own label; distribution economies’, and ‘means of financing expansion’. The same document also noted (under a heading of ‘Value’) that ‘whatever absolute p/e, significant benefit to T[esco] and T[esco] shareholders, T[esco] is getting too good a deal’. Under the heading ‘Cost to T[esco]’, the document notes that ‘significant benefit to T[esco] in terms of acquiring regional interest with no time lag’, concluding that the ‘effect is that T[esco] must offer significant increased terms to reflect premium for control’.Footnote20 Though the document also asserted that there was a ‘strong recommendation’ to reject the offer, the tonality of the document is one whereby Hillards were struggling to articulate their own strategy but could easily see the benefit for Tesco. An undated handwritten note offered a more advanced version of the justifications for the defence. It was framed in terms of the future and the past, and opened with two pointed questions: ‘where is future growth coming from?’ and ‘what is the commercial strategy?’ The note identified the opening of new stores, central distribution, the development of own label products, and the introduction of new products as a source of future growth. In terms of ‘the past’, it questions ‘A Tesco charge: they will run Hillards more profitably’ is answered with uncertainty–’suggest ways of answering this’– and ‘can we tackle the Tesco record in Yorkshire?’Footnote21 Although the precise timings of the undated note, with respect to the development and timing of the first draft and second drafts of the defence document, is not known. It is clear from the existence of all these documents that the formulation of the defence was part of a real-time sensemaking process.

By 25 March Rothschilds were beginning to distil a clearer sense of Hillards’ strategic position, with a second defence document draft that better identified Hillards strategic capabilities. One revealing passage stated that ‘it is not our philosophy that market share needs to be pursued at the expense of profits and we have placed most emphasis in recent years on improving margins’.Footnote22 In this sense, then, Hillards were positioning themselves as a regional firm, with little ambition to become a bigger national player. This was counter to the oligopolistic strategies of the big national firms exploiting economies of scale and scope.

Rothschilds sought to frame a narrative for Hillards’ defence, that would ‘emphasise the historical achievements of Hillards’ management and set these out in the context of the cycle of food retailing [in order to] emphasise the need to look at the ten year picture to see how the investment/planning pays off in the future’.Footnote23 This would ‘stress that the benefits should go to the Hillards’ shareholder not Tesco’.Footnote24 They also suggested by the time of the second defence document (to be sent on 1 May 1987) that ‘by this stage the argument is likely to turn on the long-term value of the Hillards’ business’.Footnote25 Rothschilds thought that Hillards’ regionality and its mid-sized stores were a potential strength, ‘perhaps especially with regard to Yorkshire–any characteristics of this market which make the Hillards’ ‘approach’ more suitable than the Tesco one’.Footnote26 ‘These factors will build up a picture of a business with a profitable long-term future as a distinct regional operation able to deploy the strategic strength of the majors but within its own niche market. The price for acquiring such a business will have to be substantial’, they concluded.Footnote27 On 27 March 1987 Hillards wrote to its shareholders, making the case to reject the Tesco bid:

Hillards has been a successful, independent regional retailer for one hundred and one years. We have the strategy, we have the management team and we have made the investments to continue this success. An independent Hillards would, we believe, be in the interests of our shareholders, our employees and our customers.Footnote28

The belief that the Yorkshire nature of Hillards was of essential value to the firm was at the core of the internal discourse relating to the independence of the firm, and targeted this specialism at institutional shareholders:

We regard it as a strength being a regional food retailer, particularly in an area which is economically and geographically very different from, say, SE England. Our regional emphasis enables us to make efficiencies in advertising and distribution and means of course that all management knows the market very well. … Yorkshire has limited need for new hypermarkets. Our key focus is on medium-sized-towns where competition will never be as severe as a conurbation. In these towns, we can advertise cheaply and develop our distinctive brand image.Footnote30

What are the key points between Hillards and Tesco? We’re tightly focused geographically (and will get better). Shorter chains of command and less unnecessary complexity. High levels of management and staff motivation. We focus on food and a restricted range of non-food lines. … Tesco’s development targets for out of town stores are for much larger stores. We’ve made some mistakes in non-food and want to stick to the things that we manage best. Tesco new store shelf space mix wouldn’t really be appropriate for any of our stores. We’ve a wider range of food on sale in Yorkshire than Tesco. Our large stores are generally newer, particularly in Yorkshire. We have a higher proportion of in-store bakeries (44% vs 33%), delicatessens (97% vs 76%) and self service wines and spirits departments (95% vs 62%) than did Tesco at the end of the last financial year.Footnote31

13 April 1987 was the first acceptance date, with Tesco expected to announce the level of acceptance and extend the offer on 14 April.Footnote34 The result was that the initial offer was rejected by 97% of the Hillards’ shareholders other than the existing Tesco shareholding of Hillards’ shares.Footnote35 So at that stage, Hillards still stood a chance of remaining independent. As expected, Tesco extended its offer and issued a new document to shareholders. In response, Peter Hartley wrote to shareholders stating that the ‘Tesco case is based on unfounded innuendo regarding the long-term future of Hillards, which the Board continues to believe is very secure’, going on to urge shareholders to reject the second offer.Footnote36

Hillards initially planned to release the second defence document on 1 May 1987, but it seems likely that it was actually sent on 23 April 1987.Footnote37 The final version of the second defence document was a much more advanced and robust defence of Hillards position:

Hillards strategy is designed to ensure continuing growth into the 1990s. Tesco has not questioned our strategy. In fact, it has endorsed it. The Tesco bid is no more than an opportunist attempt to buy, on the cheap, a significant sales presence in parts of the country where it has remained weak. And with little to contribute on strategy, Tesco is now trying to construct a case on the erroneous assumption that significant growth in food retailing is only achievable by large ‘national organizations’.Footnote38

Shareholder registers for this period indicate that the majority of shares were held by institutional investors.Footnote40 Yet the tonality of the defence documents suggests that their main audience were personal investors. In turn this influenced the campaign tactics that were used.

The media campaign

Hillards sought to mount a systematic campaign against Tesco in the press, and to a lesser extent the broadcast media. Gordon Young at Rothschilds wrote to Peter Hartley to say that he intended to talk to journalists at The Independent, Sunday Telegraph and Sunday Times and that Hartley might deal with the Northern Press, including the Yorkshire Post, Liverpool Daily Post, and the Manchester Evening News.Footnote41 The intention was to brief the press on support from local MPs who had, in turn, lobbied Paul Channon the then Trade and Industry Secretary ‘to express their concern over the bid’. Their main objection was connected to likely job losses.Footnote42

The bid and subsequent campaign also invited a lot of media attention external to the strategy of Hillards. Channel 4 followed Hartley and associates around London, documenting parts of their campaign as well as coming up to Yorkshire to film in store and outside of a pithead in South Yorkshire, to demonstrate Hillards part within the mining community. Peter Hartley and the bid were also subject to a profile in the Observer. However, this media attention was not necessarily part of Hillards strategy but did play into its overall public coverage and ultimately media campaign. Hillards made their feelings about the bid publicly known, often citing controversy furthering to the strategy of counter-hostility, as Peter Hartey states:

And the whole bid was very closely followed by the press because it was contested so strongly, there was a tremendous amount of publicity about it in the papers continually. I think I also got wrapped in the knuckles by saying something to…on the radio that I shouldn’t have said. And in a way one felt one was having sort of one’s hand sort of partially tied behind ones back by the by what one could and could not say. But those were the rules and regulations and I think probably we stuck to them…generally.Footnote43

I feel I ought to point out … that Hillards were the first to quote AGB statistics in this confrontation, albeit having first obtained AGB’s permission. The numbers quoted were not the most recent available. They were used in conjunction with other data without our knowledge or approval, and used in a way which, had we been consulted, would have given us cause to doubt the conclusion being drawn and consequent refusal of our permission for their use.Footnote45

The regulatory campaign

Hillards also attempted to have the takeover stopped by regulators. Hillards’ solicitors–Travers Smith Braithwaite–wrote to the Office of Fair Trading attempting to get the takeover referred to the Monopolies and Mergers Commission:

There are a number of areas of concern of which the first is the concentration in the grocery retailing sector. The Office is aware that as a result of a number of mergers over recent years there are nationally only 5 significant companies involved in this sector holding between them approximately 50% of the retail grocery market. The next largest companies … are significantly smaller (3% and less in national market share terms) and there are only a limited number of such companies of which Hillards is one. As these smaller companies disappear then not only will present competition be reduced but potential competition will be lessened. The chance that any one of these companies might grow to a size where it could effectively challenge the major companies also ceases to exist.Footnote50

The management of Hillards consider it almost certain that as a result of overlap between individual stores a number of Hillards or Tesco stores will close and that Tesco will also close further Hillards stores because these do not match the normal requirements of Tesco for its stores. Hillards itself does not intend to close these stores falling in the latter category.Footnote51

I have spoken to Mr Peter Hartley, Chairman of Hillards, and he informed me that the first time he knew of any intention by Tesco to make an offer was when he was telephoned by Mr Ian MacLaurin, Chairman of Tesco, at 8.55pm on Monday 9th March. Rothschilds was appointed on the afternoon of Tuesday 10th March following the announcement of that offer and the decision by Kleinwort Benson that it had a conflict of interest in acting for Hillards. I can therefore confirm that neither the company nor ourselves knew of the proposed offer during the period of the price movement of the shares. I hope this is sufficient for your purpose.Footnote53

The shareholders campaign

A much more successful aspect of the Hillards defence was an attempt to run a grassroots campaign to hinder (or potentially halt) the progress of the Tesco bid. This took the form of building public awareness of the bid, and therefore support for the independence of Hillards.

The breakdown of shareholdings prior to the bid can be seen in and . These data are recorded in the archive in the form of hand drawn tables of shareholdings and reports a summary of overall shareholdings, and reports a breakdown of the institutional shareholders with over 800,000 shares calculated on 3 May 1986.Footnote55 The data show that be far the largest shareholders are institutions and pension funds, with a combined 60.08% holding.

Table 1. Summary of shareholders, 3 May 1986.Footnote56

Table 2. Institutional shareholders with over 800,000 shares calculated on 3 May 1986.Footnote57

A number of tactics were employed by Hillards to engage the public, build shareholder support, rouse hostility, and raise the profile of the defence in the media. Some examples include the answering of phones with, ‘Good Morning, Hillards not for Sale’, and the same ‘Hillards not for Sale’ slogan was adorned on the side of the delivery lorries, and was the defence slogan on other printed material such as badges (worn by employees and customers), letterheads, newsletters and carrier bags. The Chairman of Hillards also wrote to a large proportion of the small shareholders individually, encouraging them not to sell their shares. A significant number of these shareholders took the time to write back, expressing their views. Many of whom, but not all, were against the Tesco bid, and a few letters included tails of dinners rudely interrupted by Tesco cold calling:

My wife and I were last night disturbed at dinner by some hireling ringing up possibly on behalf of Tesco concerning my wife’s shares.

Needless to say he got short shrift and told the error of his ways.Footnote58

In view of your letter of apology 6th of April I was surprised to be pestered again by one of your underlings. Obviously they are quite out of control and this time it was a woman who again rang at a time when any civilised person would be enjoying a drink. If you were running a tight ship such behaviour would not be tolerated.

I note that Mr Hartley, the Chairman of Hillards at least has the sense and good manners to write letters to his shareholders.Footnote59

Thank you for your letter regarding the sale of my shares in Hillards.

I feel so guilty about selling these. For a year or so I wanted to sell but couldn’t bring myself to do so. However my sister and I have no immediate family and we thought we would like to have some extra money to spend…

…Please forgive me, I feel so guilty about it all…Footnote60

I am writing to confirm to you that I will not accept the present terms of the Tesco bid for Hillards as reported in the papers on March 11th in respect of the … ordinary shares of Hillards PLC registed in my name.

Peter Hartley also wrote to most Conservative MPs and a high proportion of Labour MPs as well, with a focus on the regions where there was a Hillards store in the constituency. These letters rarely elicited any responses.Footnote62 The effectiveness of these interventions was however limited. As although the independence of Hillards was plausible, it is unlikely that building support in the local community and within the family would have any effect on the larger institutional shareholders whose decisions would ultimately determine the outcome of the bid.

Tesco also mounted a shareholder campaign and first wrote to Hillards’ shareholders on the 16 March, six days after publicly announcing the bid. These documents detailed the background, reasoning and proposed benefits of the offer, with Tesco citing consistencies of store size and profile as well as moves into own label branding and central distribution between the two companies. However, Tesco also drew attention to the Yorkshire element of the takeover, stating;

At Tesco, we attach considerable importance to achieving an appropriate market share in Yorkshire where Tesco is currently under-represented…This fit highlights the strategic reasons for acquiring Hillards as a means of expanding our trade presence in Yorkshire and the surrounding area.Footnote63

Tesco would write to shareholders again on the 15 April, and finally on the 1st May with the increased and final offer. This document further set out the benefits of the offer, citing a ‘substantial capital uplift of 64 per cent’ and a ‘significant increase in divided income of 34.5 per cent’.

At this stage Tesco also appeared to have support from the financial media, including in the final document to shareholders a range of quotations supporting the generosity of the offer:

Analysts believes that the new Tesco offer is a knockout. The London Standard, 27 April 1987.Footnote64

Hillards shareholders thinking of the Tesco paper offer should have no suspicions about the strength of the Tesco price. Financial Times, 30 April 1987.Footnote65

He[Hartley] said: ‘I have spoken to six people at the weekend….and they say it does not matter what offer Tesco comes up with – they will not accept’. The Times, 27 April 1987.Footnote66

….there must be a level at which family loyalty must be conceded in the interests of other shareholder!. Yorkshire Post, 12 March 1987.Footnote67

The share price of Hillards went from 178p in early February to an eventual take-over price of 465p. This is a marked difference, and a significant premium for the shareholders. From the point of view of the shareholders this would reflect a good price for what would appear to be a highly regarded regional chain. The public campaign must have contributed to this increase in share price, in effect extracting a maximal (or near maximal) price from Tesco to acquire the firm. Though Hillards disappeared, the shareholders did well.

Conclusions

First, Hillards was an example of a family-run firm that had surrendered ownership to institutional shareholders in the 1970s. This was an unseen weakness of the corporate governance arrangements as viewed from the Hillards family perspective, as it exposed a hitherto successful company to a hostile takeover. Family companies such as Hillards are often seen from the inside as an integral part of the wider family structure. A takeover may be unwanted, and personally or familially invasive. Family stewardship of the firm gave Peter Hartley reason and a narrative to defend the company. This reflects the cultural-social context of the firm, and its identity. However, the campaign they mounted did not persuade the institutional shareholders, but it did contribute to the price being substantially increased. As such, the family-ness of Hillards and its strong regional identity amounted to a form of under-marked value to the firm, something that was only established in the defence.

Second, the case of Hillards contributes an understanding of counter-hostility as a strategy in the context of a takeover event. We have argued that strategic counter-hostility and the ‘fisticuffs in the City’ (as Ian MacLaurin described the scramble to recruit institutional shareholdings) were a necessary part of Hillards achieving a higher price for the end of its organisational life.Footnote71 In this case the cultural and social value of a firm can be calculated. In 90 days in the summer of 1987 Hillards’ demonstrated that they were worth £136 million more than the pre-takeover market capitalisation. And so, even in its organisational demise, Hillards drew a victory of sorts by exploiting Tesco’s need and desire to acquire the firm. Suggesting that a vigorous, yet ultimately unsuccessful, defence can help maximise shareholder value even if that is at the point at which the organisation ceases to exit (Clarke & Brennan, Citation1990). Tesco’s Ian MacLaurin acknowledged as much, stating that Hillards was Tesco’s only option in the North of England.Footnote72 Not least because the other regional players of significant size, Morrisons, Jacksons, and Booths, remained majority family owned. Acquiring Hillards contributed to Tesco becoming one of the dominant forces in the supermarket sector in the UK, and the returns for Tesco of acquiring the company were substantial. MacLaurin himself thought that the acquisition accounted for a 19 per cent increase in Tesco’s half-year figures in 1989.Footnote73

This gradual consolidation of economic and/or organisational power in a small number of large supermarket retailers via the processes of merger and acquisition, of which the acquisition of Hillards is part, forms the context for the narrative claims and counter-claims of the takeover itself. Recent attempts to conceive of organisational and strategic sensemaking as a power-oriented organisational activity help provide insight into this historical episode (Schildt et al., Citation2020). Hillards sensemaking was primarily concerned with establishing what their strategy actually was. However, it was also an attempt at sensegiving– that is, to communicate the sensemaking to an audience (Sonenshein, Citation2010) – in this case both the shareholder and the media, and perhaps also for employees. As such it was also an attempt at sensebreaking (‘deliberate efforts to invalidate and reject established understandings held by individuals or groups’ (Schildt et al., Citation2020, p. 243), to counter the narrative of Tesco that they would be more efficient managers, and that only through larger economic scale would supermarkets flourish.

Coming to understand their strategic position was an important part of framing their public and institutional message to try to resist the takeover. It is important to distinguish between the extant strategy of the Hillards that was unpacked through the sensemaking process discussed above, and the defence strategy that developed in response to the takeover. Within the defence strategy this was narratively deployed as an argument against the takeover. The counter-hostility of Hillards position rested on the plausibility of the claim to remain a viable independent entity on the basis of their strategy. It is notable therefore that a strategy of counter-hostility does not necessarily have to overcome the takeover event, but success may include–as we argue here–the achievement of maximal price to the benefit of shareholders.

In an interview conducted for this research, Ian MacLaurin argued that Hillards’ would have been taken over eventually anyway:

If it wasn’t Tesco, then somebody else would have come in and done it. There was no way… in the way that the trade was going, and the way people had money to spend, and out of town stores getting permission. All that sort of thing.Footnote74

Lastly, the experience of Hillards reveals something of the nature of the economic power increasingly vested in the larger national supermarket chains at this time. Hillards used its strong sense as a family and regional firm to craft its opposition to Tesco, which they positioned as the London-centred image of a prominent, impersonal national corporation. The defence was therefore a portrait of symbolic principle in the face of broader industry-wide trends towards oligopoly. And in this there is there is a tension between the anti-competitive nature of working towards oligopoly, and the shareholder maximising ‘efficient market’ outcome of Hillards’ counter-hostility strategy. By positioning themselves as a smaller regional firm, Hillards’ made Tesco pay a heavier price for their desire to expand–a price that was extracted from the more powerful economic actor in part because it was more powerful and sought to maintain and expand its power in the industry.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Philip Garnett

Philip Garnett is a Professor of Systems and Organisation at the University of York, where he is the Society and Ethics Pillar Lead at the Institute for Safe Autonomy.

Simon Mollan is Reader in Management at the School for Business and Society, University of York where he is Co-Director of the Centre for Contemporary Business History and Society.

Benjamin Richards is a lecturer in Organisation Studies at the University of Stirling. His research primarily focuses on the polarising and alienating forces of contemporary organisation. His work has explored postfascism and the relation between the ideational and material that discerns a particular style of organizing. His other interests and activities include the intersection of archaeology and alternative organisation, critical histories of management thought and the role of business in conspiracy theory, cultural conflict and violence.

Notes

1 Interview 1 with Peter Hartley 4 March 2016.

2 Hillards annual report and accounts 1986.

3 New stores had recently opened in Scunthorpe, Lincoln, Scarborough, and Brownhills. Retai space in firms had increased 107,000 square feet between 1985 to 1986. Bringing the total number of stores to 39, with 11 stores over 25,000 square feet in total.

4 Rawsthorn, Alice. “New Stores Help Hillards’ Growth.” Financial Times, 27 Jan. 1987, p. 23. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2304972121/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = 7e5694bc. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.

5 Churchill, David. “New Steps in Takeover Tango.” Financial Times, 5 July 1986, p. 6. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2305294071/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = d045a9da. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.; “Store Opening Costs Hold Back Hillards.” Financial Times, 29 July 1986, p. 22. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2305296449/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = 68e059ad. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.

6 Ian MacLaurin, Tiger by the Tail, p. 79.

7 Ian MacLaurin, Tiger by the Tail, p. 80.

8 Interview with Baron MacLaurin of Knebworth 27 March 2017.

9 Personal Communication with Tesco 26 June 2014.

10 Interview 1 with Peter Hartley 4 March 2016.

11 In addition to the project digitising materials related to takeover of Hillards by Tesco, Peter Hartley generously donated all of his personal papers to REDACTED ARCHIVE, where they will ultimately be made available for further research.

12 Ian MacLaurin, Tiger by the Tail, p. 80.

13 Interview 1 with Peter Hartley 4 March 2016.

14 Ian MacLaurin, Tiger by the Tail, p. 80.

15 Peter Hartely, personal communication.

16 “Store Opening Costs Hold Back Hillards.” Financial Times, 29 July 1986, p. 22. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2305296449/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = 68e059ad. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.

17 Interview 1 with Peter Hartley 4 March 2016.

18 First Defence Document. Draft, 13 March 1987.

19 Interview 1 with Peter Hartley 4 March 2016.

20 Second Defence Document. Draft. 13 March 1987.

21 Handwritten Note: “Hillards/Tesco: Strategic areas to cover for defence document”.

22 Questions and Answers for Institutional Presentations, March 25, 1987.

23 N.M Rothschild and Sons Ltd, Information Required for the Defence, 17 March 1987, p. 1.

24 N.M Rothschild and Sons Ltd, Information Required for the Defence, 17 March 1987, p. 1.

25 N.M Rothschild and Sons Ltd, Information Required for the Defence, 17 March 1987, p. 3.

26 N.M Rothschild and Sons Ltd, Information Required for the Defence, 17 March 1987, p. 4.

27 N.M Rothschild and Sons Ltd, Information Required for the Defence, 17 March 1987, p. 4.

28 Letter from Hillards to Shareholders, 27 March, 1987.

29 Letter from Hillards to Shareholders, 27 March, 1987.

30 Questions and Answers for Institutional Presentations, 26 March 1987.

31 Questions and Answers for Institutional Presentations, 26 March 1987.

32 Questions and Answers for Institutional Presentations, 26 March 1987.

33 Memo titled “Survival (Continued Development) of Regionals” 3 April 1987.

34 Draft Outline Timetable, 11 March 1987.

35 Draft Letter from Peter Hartley, Hillards, to Shareholders, 23 April 1987.

36 Draft Letter from Peter Hartley, Hillards, to Shareholders, 23 April 1987.

37 Draft Outline Timetable, 11 March 1987.

38 Draft of Second Defence Document, 21 April 1987.

39 Draft of Second Defence Document, 21 April 1987. Clippings from The Times, 14 March 1987 and the Yorkshire Post, 6 April 1987.

40 Hillards plc Shareholdings, 30 April 1983.

41 Letter from Gordon Young, Rothschilds, to Peter Hartley, Hillards, 10 April 1987.

42 Memo: “Speaking Notes for the Press”, 10 April 1987.

43 Interview 1 with Peter Hartley 4th March 2016.

44 Letter from Robert Dowds, Managing Director, Hillards, to SC Hurst, Audits of Great Britain, 10 April 1987.

45 Letter to Robert Dowrds, Hillards, from Audits of Great Britain, 15 April 1987.

46 Analysis of shareholders 25 March 1987.

47 “Yorkshire Stoicism Versus National Muscle.” Financial Times, 11 May 1987, p. 26. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2304984159/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = 767ea5b2. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.

48 “Battle Facing Yorkshire Die-hards.” Financial Times, 11 Mar. 1987, p. 26. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2304978810/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = 8a02825f. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.; Yorkshire Stoicism Versus National Muscle.” Financial Times, 11 May 1987, p. 26. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2304984159/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = 767ea5b2. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.

49 “Battle Facing Yorkshire Die-hards.” Financial Times, 11 Mar. 1987, p. 26. Financial Times Historical Archive, link-gale-com.libproxy.york.ac.uk/apps/doc/HS2304978810/FTHA?u = uniyork&sid = bookmark-FTHA&xid = 8a02825f. Accessed 3 Apr. 2022.

50 Copy of letter from David Strang, Travers Smith Braithwaite, to the Office of Fair Trading, to Bob Dowds, Managing Director, Hillards, 20 March 1987.

51 Copy of letter from David Strang, Travers Smith Braithwaite, to the Office of Fair Trading, to Bob Dowds, Managing Director, Hillards, 20 March 1987.

52 Letter from B.A Muston, Panel on Takeovers and Mergers, to Rothschilds, 18 March 1987.

53 Letter from JAG Young, Rothschilds, to BA Muston, Panel on Takeovers and Mergers, 25 March 1987.

54 Letter from JAG Young, Rothschilds to Peter Hartley, Hillards, 6 April 1987.

55 Data is recorded in the archive in the form of hand drawn tables of shareholdings, 3rd of May 1986.

56 Data is recorded in the archive in the form of hand drawn tables of shareholdings, 3rd of May 1986.

57 Data is recorded in the archive in the form of hand drawn tables of shareholdings, 3rd of May 1986.

58 Letter from the Hon. R.H.C Neville to Ian MacLaurin 3 April 1987.

59 Letter from the Hon. R.H.C Neville to Ian MacLaurin 8 May 1987.

60 Letter from Q. Smith to Peter Hartley 4 May 1987.

61 Adam Hartley (12/3/87), Susan Hartley (12/3/87), Gay Hartley (12/3/87), Simon Hartley (12/3/87), Ana Hartley (12/3/87), Peter Hartley (12/3/87), Ada Hillard (11/3/87).

62 Letter from Gary Waller MP to Peter Hartley 30 April 1987; Letter from Allan McKay MP to Peter Harley 9 April 198.

63 Tesco document to Hillards shareholders 16th March 1987.

64 Tesco final offer document to Hillards shareholders 1st May 1987.

65 Tesco final offer document to Hillards shareholders 1st May 1987.

66 Tesco final offer document to Hillards shareholders 1st May 1987.

67 Tesco final offer document to Hillards shareholders 1st May 1987.

68 Interview 5 with Peter Hartley 5 Jan 2017.

69 Draft Outline Timetable, 11 March 1987; Draft Letter from Peter Hartley, Hillards, to Shareholders, 23 April 1987.

70 Interview 1 with Peter Hartley 4 March 2016.

71 Interview with Baron MacLaurin of Knebworth 27 of March 2017.

72 Interview with Baron MacLaurin of Knebworth 27 of March 2017.

73 Ian MacLaurin, Tiger by the Tail, page 81.

74 Interview with Baron MacLaurin of Knebworth 27 of March 2017.

References

- Alexander, A. (2008). Format development and retail change: Supermarket retailing and the London Co-operative Society. Business History, 50(4), 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790802106679

- Alexander, A. (2015). Decision-making authority in British supermarket chains. Business History, 57(4), 614–637. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2015.1007864

- Alexander, A., Shaw, G., & Curth, L. (2005). Promoting retail innovation: Knowledge flows during the emergence of self-service and supermarket retailing in Britain. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 37(5), 805–821. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3741

- Angwin, D., Stern, P., & Bradley, S. (2004). Agent or steward: The target CEO in a hostile takeover. Can a condemned agent be redeemed? Long Range Planning, 37(3), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lrp.2004.03.006

- Bailey, A. R., & Alexander, A. (2019). Cadbury and the rise of the supermarket: Innovation in marketing 1953–1975. Business History, 61(4), 659–680. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2017.1400012

- Bowen, G. A. (2009). Document analysis as a qualitative research method. Qualitative Research Journal, 9(2), 27–40. https://doi.org/10.3316/QRJ0902027

- Brennan, N. M., Daly, C. A., & Harrington, C. S. (2010). Rhetoric, argument and impression management in hostile takeover defence documents. The British Accounting Review, 42(4), 253–268. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2010.07.008

- Bucheli, M., & Daniel Wadhwani, R. (2013). Organizations in time: History, theory, methods. Oxford University Press.

- Cartwright, S., & Cooper, C. L. (2012). Managing mergers acquisitions and strategic alliances. Routledge.

- Clark, T., & Chan, S. P. (2014). A history of Tesco: The rise of Britain’s biggest supermarket. The Daily Telegraph, October 4, 2014. https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/0/history-tesco-rise-britains-biggest-supermarket/.

- Clarke, C. J., & Brennan, K. (1990). Defensive Strategies against Takeovers: Creating Shareholder Value. Long Range Planning, 23(1), 95–101. https://doi.org/10.1016/0024-6301(90)90011-R

- Colli, A., Howorth, C., & Rose, M. (2013). Long-term perspectives on family business. Business History, 55(6), 841–854. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.744589

- Colli, A., & Larsson, M. (2014). Family business and business history: An example of comparative research. Business History, 56(1), 37–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2013.818417

- Decker, S. (2013). The silence of the archives: Business history, post-colonialism and archival ethnography. Management and Organizational History, 8(2), 155–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2012.761491

- Decker, S., Hassard, J., & Rowlinson, M. (2020). Rethinking history and memory in organization studies: The case for historiographical reflexivity. Human Relations; Studies towards the Integration of the Social Sciences, 74(8), 1123–1155.

- Dodd, S. D., & Dyck, B. (2015). Agency, stewardship, and the universal-family firm: A qualitative historical analysis. Family Business Review, 28(4), 312–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894486515600860

- Eisenhardt, K. M. (1989). Building theories from case study research. The Academy of Management Review, 14(4), 532–550. https://doi.org/10.2307/258557

- Eisenhardt, K. M., & Graebner, M. E. (2007). Theory building from cases: Opportunities and challenges. Academy of Management Journal, 50(1), 25–32. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- Ford, J. (2018). Watchdog needs to check out merits of supermarket merger. Financial Times, April 29, 2018. https://www.ft.com/content/d643b1ca-4b8e-11e8-97e4-13afc22d86d4

- Holt, R., & Popp, A. (2013). Emotion, succession, and the family firm: Josiah Wedgwood & Sons. Business History, 55(6), 892–909. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.744588

- Johnston, A. (2007). Takeover regulation: Historical and theoretical perspectives on the city code. The Cambridge Law Journal, 66(2), 422–460. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0008197307000591

- Jones, O., Ghobadian, A., O’Regan, N., & Antcliff, V. (2013). Dynamic capabilities in a sixth-generation family firm: Entrepreneurship and the bibby line. Business History, 55(6), 910–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/00076791.2012.744590

- Kolev, K., Haleblian, J., & McNamara, J. (2012). A review of the merger and acquisition wave literature: History, antecedants, consequences and future directions. In D. Faulkner, S. Teerikangas, & R. J. Joseph (Eds.), The handbook of mergers and acquisitions (pp. 19–39). Oxford University Press.

- Krippner, G. (2005). The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review, 3(2), 173–208. https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/mwi008

- Lapavitsas, C. (2011). Theorizing financialization. Work, Employment & Society: A Journal of the British Sociological Association, 25(4), 611–626. https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017011419708

- Lazonick, W., & O’Sullivan, M. (2000). Maximizing shareholder value: A new ideology for corporate governance. Economy and Society, 29(1), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/030851400360541

- Lee, B. (2012). Using documents in organizational research. In G. Symon & C. Cassell (Eds.), Qualitative organizational research (pp. 389–407). Sage.

- Maclean, M., Harvey, C., & Clegg, S. R. (2016). Conceptualizing historical organization studies. Academy of Management Review, 41(4), 609–632. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0133

- Marwick, A. (1970). The nature of history. Macmillan.

- Mintzberg, H., & Waters, J. A. (1985). Of strategies, deliberate and emergent. Strategic Management Journal, 6(3), 257–272. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.4250060306

- Morelli, C. (2004). Explaining the growth of British multiple retailing during the Golden Age: 1976–94. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 36(4), 667–684. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3689

- Morelli, C. (2007). Further reflections on the golden age in British multiple retailing 1976–94: Capital investment, market share, and retail margins. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39(12), 2993–3007. https://doi.org/10.1068/a38412

- Oral History Society. (2015). Is your oral history legal and ethical?: Practical steps. http://www.ohs.org.uk/ethics.php

- Pindado, J., & Requejo, I. (2014). Family business performance from a governance perspective: A review of empirical research. International Journal of Management Reviews, 17(3), 279–311. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12040

- Rowlinson, M., Hassard, J., & Decker, S. (2014). Research strategies for organizational history: A dialogue between historical theory and organization theory. Academy of Management Review, 39(3), 250–274. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0203

- Schildt, H., Mantere, S., & Cornelissen, J. (2020). Power in sensemaking processes. Organization Studies, 41(2), 241–265. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840619847718

- Schoenberg, R., & Thornton, D. (2006). The impact of bid defences in hostile acquisitions. European Management Journal, 24(2-3), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2006.03.004

- Schwert, G. W. (2000). Hostility in takeovers: In the eyes of the beholder? The Journal of Finance, 55(6), 2599–2640. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-1082.00301

- Shaw, G., Curth, L., & Alexander, A. (2004). Selling self-service and the supermarket: The Americanisation of food retailing in Britain, 1945–60. Business History, 46(4), 568–582. https://doi.org/10.1080/0007679042000231847

- Siebels, J.-F., Knyphausen, A., & Ufseß, D. (2012). A review of theory in family business research: The implications for corporate governance. International Journal of Management Reviews, 14(3), 280–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2370.2011.00317.x

- Sonenshein, S. (2010). We’re changing—Or are we? untangling the role of progressive, regressive, and stability narratives during strategic change implementation. Academy of Management Journal, 53(3), 477–512. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2010.51467638

- Tennent, K., & Mollan, S. (2020). The limits of the narratives of strategy: Three stories from the history of music retail. Management & Organizational History, 15(3), 273–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449359.2021.1878042

- Turton, A. (2017). The international business archives handbook: Understanding and managing the historical records of business. Routledge.

- Weick, K. E. (1995). Sensemaking in organizations. Sage.

- Weick, K. E., Sutcliffe, K. M., & Obstfeld, D. (2005). Organizing and the process of sensemaking. Organization Science, 16(4), 409–421. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1050.0133

- Williams, K. (2000). From shareholder value to present-day capitalism. Economy and Society, 29(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/030851400360532

- Wrigley, N. (1991). Is the ‘golden age’ of British grocery retailing at a watershed? Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 23(11), 1537–1544. https://doi.org/10.1068/a231537

- Yin, R. (1994). Case study research: Design and methods. Sage.