Abstract

Using records left by the Ionian Bank and other British multinational banks, as well as building on the extensive insights provided by leading business historians, the article contributes to the debate about how historical analysis can illuminate the study of international business. We shall achieve this by firstly evaluating the reasons why Ionian moved to Egypt, applying Dunning’s ‘eclectic paradigm’ to the analysis of a highly complex economic and political environment. We shall then address the organisational challenges of managing a geographically dispersed operation, highlighting the principal-agent issues associated with geographically dispersed businesses. This will be followed by an analysis of Ionian’s performance, explaining how the changing environment affected management’s ability to generate a consistent level of profitability.

1. Introduction

One of the most significant financial developments of the nineteenth century was the emergence of multinational banks from the 1830s, not least because of their impact on international trade and the ways in which they stimulated the emergence of banking in many developing economies. Apart from Jones’ (Citation1993) exhaustive study of British multinational banks, however, and work by Saul (Citation1997), Beniamin (Citation2020) and Berbenni (Citation2023), we know relatively little about the day-to-day operations of foreign banks as they struggled to compete in a highly complex environment. This gap can be filled by tapping into records left by the Ionian Bank, providing an opportunity to extend our understanding of the issues associated with both multinational banking and the economic and political challenges faced by foreign banks in Egypt.

Although the archive is incomplete, and there is even less material on other banks that operated in Egypt, studying the Ionian Bank provides useful insights into how management coped with a combination of factors, ranging from intense competition and strengthening nationalism to internal organisational problems. Our first aim will be to analyse the strategic reasons why the Ionian Bank established a branch in Egypt, applying Dunning’s ‘eclectic paradigm’ as a theoretical base (Dunning, Citation1993). Secondly, with reference to principal-agent theory we can examine the organisational challenges associated with running a geographically dispersed business such as a multinational bank in what was a highly competitive environment. This work will contribute to the debate surrounding the extent to which international business scholars ought to adopt a ‘more critical approach to sources and attention to sequence’ (Buckley, Citation2021, p. 797), while recognising that the past ‘is not a simplified version of the present’ (da Silva Lopes et al., Citation2019, p. 1338). Above all, we intend to offer an explanation of how foreign banks coped with issues such as geographical dispersion, surging nationalism and intense competition by referring in detail to the primary records left by the Ionian Bank.

In conducting this multi-level analysis, we are faced with a range of issues. Firstly, it is difficult to generalise on the basis of a single case-study, especially as Egypt became the base for a large number of foreign banks between the 1860s and 1950s (see ). On the other hand, because the motivations behind their formation were similar, Ionian Bank’s experiences reflected the difficulties associated with this form of enterprise at a time of considerable economic and political volatility. Another complication relates to the Egyptian historiography, and especially the orientation within some secondary sources to be highly critical of the strategies pursued by foreign bankers prior to the Egyptian Revolution of 1952. This bias can be corrected by demonstrating that many foreign banks struggled to generate steady profitability, especially in the interwar years when a combination of intense competition, stagnant cotton prices and strengthening nationalism posed acute challenges. Although some secondary sources are also available to highlight the difficulties of operating in Egypt (Beniamin, Citation2020; Berbenni, Citation2023; Jones, Citation1993; Saul, Citation1997), a detailed case-study can provide a more nuanced assessment of both the context and its impact on strategies and structures.

Table 1. Major banks and mortgage companies operating in Egypt before 1952

The article will start by providing both a brief overview of why and when British multinational banking emerged and some of the appropriate theoretical frameworks that can be applied to this sector. This will be followed by an analysis of the Egyptian context in which they operated, revealing how until the 1920s foreign banks dominated the market. The Ionian Bank’s decision to open an Egyptian branch can then be analysed, alongside the organisational challenges it experienced in managing a branch that was competing against a large number of rivals. It will also be essential to explain how the establishment in 1920 of Egypt’s first indigenously owned bank, Banque Misr (Davis, Citation1983), added considerably to this competitive environment. We have started the study in 1907 when the Ionian Bank opened its Egyptian branch. The termination date of 1939 has been chosen because conditions changed markedly thereafter, firstly because of World War II, following which Egypt became subject to even more intense nationalism, resulting in the 1952 Revolution. Nevertheless, as we shall reiterate in the conclusions, by focusing on the period 1907–1939 we can contribute to providing a deeper understanding of British multinational banking and the study of international business, confirming the value of pursuing a multidisciplinary approach to these subjects.

2. Theory and practice in multinational banking

Defined as a financial corporation which acquires deposits and initiates loans from offices located in more than one country (Casson, Citation1990; Gray & Gray, Citation1981), multinational banking was one of the most significant financial developments of the nineteenth century. The phenomenon originated in the 1830s when an entrepreneurial group of British financiers seized the profitable opportunities created by expanding international trade and weak indigenous banking in mainly imperially connected countries (Jones, Citation1993, pp. 14–16). As sterling was used to finance two-thirds of this trade (Jones, Citation1993, p. 379), these first-mover advantages were also facilitated further by Britain’s comparative advantage as the leading industrial, trading and financial nation. Indeed, British overseas banks played a key role in boosting the volume of international trade by providing finance to exporters and importers (Baster, Citation1935).

Much of this trade was in the form of exporting raw materials and primary commodities from underdeveloped countries and importing manufactured goods from Britain or elsewhere. By 1913, there were twenty-eight British overseas banks, maintaining 1,286 branches (Jones, Citation1998, p. 344). Although multinational banks were formed by financiers in other countries such as France, Italy, Belgium and Germany, this only increased the total number of branches to 1,610 in 1913 (Battilossi, Citation2006, p. 361), demonstrating British dominance in this sector. It is also noticeable that longevity was a feature of British multinational banking, because such was their resource base and dexterity in coping with both local and international vicissitudes that the vast majority managed to withstand the financial crises of the early-1890s, 1907 and 1931, not to mention two world wars and a plethora of less contagious conflicts (Jones, Citation1993, p. 379).

Having outlined these basic features of British multinational banks, and Jones (Citation1993) especially provides extensive analysis of this phenomenon, it is also useful to consider how they can be accommodated into the theoretical perspectives associated with international business. Jones (Citation1993, p. 377–378) has concluded that the creation of British multinational banks ‘lends support to the existing models’, while Gray and Gray (Citation1981) specifically apply Dunning’s ‘eclectic (or, OLI) paradigm’ to multinational banks in order better to understand the motivations behind their creation and development. This paradigm is based on the relative advantages associated with ownership, location and internalisation, providing a model that can be directly related to empirical evidence. Of course, trade finance banks are faced with two alternative forms of foreign operations: either to transact through market arrangements such as correspondent relations, or through foreign direct investment. The former was not always feasible given the lack of reliable and trustworthy indigenous correspondents in many host countries, adding significantly to both transaction costs and risk. On the other hand, while the latter alternative entailed higher costs and required a large volume of trade to cover these investments, British multinational banks possessed such a significant comparative advantage to both indigenous and other banking systems that this would prove to be a more viable option.

To elaborate further on this theme, as far as ownership advantages were concerned British multinational banks could access the resources of what was the financial capital of the world, the City of London. In addition, reliable market knowledge was available through either the country’s extensive mercantile networks or governmental sources such as consular reports that offered deep insights into what was happening, especially in British dependencies. The location advantages were mainly associated with what Stopford (Citation1974, p. 327) termed the ‘haven of sanity and security’ associated with those countries which were either a formal component of the British Empire or were designated as dependencies. This provided the political and economic stability which is the bedrock of commercial success, especially as competition from indigenous banks was extremely limited until well into the twentieth century. Finally, as we have already noted, internalisation was preferable to the alternative of market-based transactions because the requisite levels of trust were not available, while British multinational banks were able to tap into the pool of talent and expertise arising from its long domestic traditions in this area of business.

As we shall see later when examining the Ionian Bank, however, while all of these advantages were apparent to those who were responsible for its creation and expansion, it is vitally important to emphasise how, especially in terms of internalisation advantages, multinational banks could be adversely affected by their geographically dispersed nature. In the first place, one should remember that all British multinational banks were based in the City of London, yet conducted only limited business in their home country, mostly associated with discounting bills and staff recruitment (Jones Citation1998, pp. 349–350). In this sense, they can be classified as a variant of what Wilkins (Citation1988) has termed ‘free-standing companies’, with the board of directors and headquarters staff located in the City and the bulk of the banking done overseas. Apart from safeguarding the interests of shareholders, as Jones (Citation1993, pp. 41–44) outlines the board was the principal source of strategic decision-making, choosing where branches were established, banking and investment policy and the appointment of local managers. Most of these overseas banks would also employ the equivalent of a chief executive officer, often referred to as a general manager, some of whom would be based in the region where the bank operated, but most worked out of London. This person and the directors would be supported by a small administrative staff in London, with the bulk of the workforce operating in the overseas branch network. The branch managers would report regularly to either the board or chief executive officer, with the head office imposing an inspection system that ensured the accuracy of the information that flowed around these geographically dispersed organisations.

Although this was a relatively simple organisational structure, keeping overhead costs to a minimum, the challenge for directors and general managers was to maintain an appropriate level of control over the branches. This highlights the significant principal-agent problem associated with geographically dispersed operations, given the danger of branch managers and other employees (agents) pursuing policies that ran counter to those advocated by the board (principals). Crucially, as Casson (Citation1990) noted, agency problems can have negative consequences for firm expansion, because as a business expands in scale or scope, costs associated with agency will increase. In order to overcome this problem, not only were extensive reporting and auditing processes developed, Jones (Citation1993, pp. 50–51) has also argued that a ‘socialization’ process would appear to have been fashioned which determined the ways in which future managers were recruited.

Formal educational attainments were less important than the possession of social and sporting skills, which ensured that young recruits would conform to the corporate culture, be trusted, and perform a proper representational role for a British overseas bank…These men were imbued with Victorian public school values of service and loyalty, strengthened by years of service within an individual bank during which they were socialized with corporate traditions and standards.

As we shall see later, however, while this process could have been useful in binding together the senior management of an organisation, it did not entirely overcome the inevitable principal-agent tensions that emerged when dealing with other employees and agents. This highlights the benefits of pursuing a case-study approach, because it adds greater nuance to the more general studies of overseas banking.

We shall return later to address each of these features in the context of Ionian’s experiences, analysing whether senior management devised appropriate strategies and structures to cope with the challenges of operating in a country such as Egypt. Firstly, however, it is important to assess the nature of the Egyptian context from the 1860s as a means of understanding why foreign banks from several countries scrambled for a share of what was perceived to be a booming economy.

3. The Egyptian context and foreign banks

When as a result of the American Civil War (1861–1865) Egypt temporarily became the main supplier to European textile manufacturers of long staple cotton (Owen, Citation1981, p. 138), this provided a significant boost to what to date had been a subsistence economy. Another key development in that decade was the construction of the Suez Canal (1859–1869), providing a much faster route between Europe and the East, thereby linking Egypt inexorably to global economic and political activities (Farnie, Citation1969). At the same time, one must remember that because Islamic law forbade usury, the Egyptian financial sector barely existed (Crouchley, Citation1936, p. 28). Indeed, the religious context explains why up to the 1860s functions normally performed by banks were handled by foreign residents, notably Greeks, Jews and Levantines, who acted as merchants and moneylenders. John Bowring, a British politician and diplomat, noted during his visit to Egypt in 1839 that apart from a scarcity of money in circulation, moneylenders charged high interest rates of 2% per month, with diamonds commonly used as security (Bowring, Citation1840, p. 82). Private savings and surpluses made by the indigenous population found their way into land purchases, or were converted into gold and jewellery and hoarded, rather than deposited in a bank (Tignor, Citation1981, p. 108). As we shall see later, the Ionian Bank struggled continually with this problem, because it was never able to generate significant domestic deposits to supplement its liquidity.

It is consequently not surprising that until the 1950s European financial centres, mainly London and Paris, controlled Egyptian banking. Antonini (1927, cited in Baster, Citation1935, p. 72) described Egypt as the ‘Babel of banking’, while Abdel Wahab (Citation1933, p. 619), an Egyptian Minister of Finance, presented a distinctly critical view:

Egypt has been suffering from a defective banking system … most banks are branches of French, Italian, Belgian, Greek, or British banks, and receive their instructions from Paris, Rome, Brussels, Athens, or London. It is not so much the state of credit in the country which regulates the extent of their transactions as the prices of money in their own home markets.

It is clear that the cotton export boom which began in the 1860s had provided foreign banks with sufficient incentive to enter the Egyptian market. Of central importance here was the demand from a range of émigré communities that provided Egypt with much of its mercantile capacity. As Beniamin et al. (Citation2023, p. 6) have demonstrated, Jewish and Greek business groups had by the 1860s been operating through ‘powerful business groups that were bound by personal, family and ethnic ties, frequently strengthened by extensive intra-marital arrangements and intense corporate networks’. This allowed them to achieve dominance in areas such as trade and transport, cotton cultivation and export, and construction. Although they had accumulated considerable wealth by the 1860s, however, much more capital and credit was required if Egypt was going to exploit effectively the opportunities afforded by the expansion of cotton cultivation and trading.

Another growing source of demand for substantial amounts of capital was the state, given its growing commitment to infrastructure development (and especially irrigation), not to mention supporting the Khedive’s lifestyle (Crouchley, Citation1936, p. 29; National Bank of Egypt, Citation1948, p. 10). Although it had only been in 1862 that Egypt took out its first foreign loan, by the 1870s borrowing from abroad had increased significantly, prompting some concern in London and Paris especially about the cavalier way in which Egyptian rulers managed their debt.Footnote1 These discussions resulted in the formation in 1876 of the Public Debt Commission, a body that survived until 1940, restoring some confidence in Egypt’s public finances. Nevertheless, by the early-1880s Egypt’s public debt had reached £E100 million (Davis, Citation1983, p. 43), an important factor that contributed to the British government’s move in 1882 to occupy the country. At the same time, this partially precipitated the emergence of Egyptian nationalism (Davis, Citation1983, p. 26), because while it was able to provide the stability on which bankers traditionally rely, the Commission’s interference with the country’s public finance was deeply resented by many Egyptians (Baster, Citation1935, p. 59).

With specific regard to banking, however, these stimuli were consequently responsible for what is illustrated in , with banks from the major European economies establishing branches in Egypt, most of which were based in Alexandria, the commercial capital. Of those listed, only the Bank of Egypt failed, having been wound up by 1912 as a result of what Jones (Citation1993, p. 79) describes as ‘incautious mortgage-lending on property’. This venture had been the first foreign bank to be established in Egypt, emerging in 1855 from an initiative by a syndicate composed of some of the most influential London financiers, including directors of the East India Company, the London and Westminster Bank (Baster, Citation1934, p. 78) and the leading private bank Glyn, Mills (Jones, Citation1993, p. 17). From the mid-1860s, it was joined by a series of British, French, Belgian, Italian and Greek initiatives, variously aimed at servicing their citizens located in Egypt and supporting the rapid development of cotton cultivation and its shipment to Europe. The only Egyptian-owned bank listed in is Banque Misr, which as we shall see later grew out of the increasingly powerful nationalist movement that emerged from the 1910s, prompting a significant increase in competition in both the cotton trade and more generally across the Egyptian economy. It is also worth noting that having acquired the Anglo-Egyptian Bank in 1920, in 1925 Barclays Bank consolidated this operation with two other subsidiaries, the Colonial Bank and the National Bank of South Africa, to create Barclays Bank DCO, a formidable competitor that had access to substantial capital resources (Jones, Citation1993, pp. 149–155).

Before moving on to analyse the challenges experienced by these ventures, it is important to note how in 1898 the National Bank of Egypt was founded as a commercial bank with some central banking responsibilities such as note issuing (Jones, Citation1993, pp. 109–110). This was especially significant because it reflected the extent to which British interests dominated Egyptian banking, in that the National Bank of Egypt was formed by Sir Ernest Cassel, a leading British financier who provided one-half of its £1 million capital. Thane (Citation1986) has also demonstrated that in the interests of stabilising the Egyptian economy, the British government was extremely supportive of Cassel’s activities. Although the National Bank was formed as an Egyptian company with a board based in Cairo, and it became the government’s principal banker, it was the London committee which controlled its operations. By 1914, almost twenty branches had been opened across Egypt, while Cassel also assisted in the formation of the Agricultural Bank of Egypt (1902) and developed banking in Sudan and Abyssinia (Jones, Citation1993, p. 110).

Having demonstrated that Egypt’s economy, and especially its banking system, was dominated by foreign interests up to the 1950s, one needs to emphasise that there was growing resentment about this level of control, creating an increasingly challenging political environment. Davis (Citation1983) has provided the most comprehensive analysis of this movement, using a Marxist framework to explain the key factors contributing to the rise of Egyptian nationalism and its most impressive financial outcome, the creation in 1920 of Banque Misr. Before elaborating further on this decisive move, however, it is vital to understand that while the British invasion of Egypt in 1882 was never meant to be permanent, it resulted in the country becoming a protectorate from 1914 that signalled a decisive change in the political scene. Apart from the increasingly onerous state debt mentioned earlier, Britain was especially anxious to ensure continuous access to the Suez Canal for its extensive interests in India and the Far East. World War One extended these links, because apart from an increased military presence in 1914 British and Egyptian currencies were linked together, an arrangement that lasted until 1947, when Egypt withdrew from the Sterling Area. While in response to mounting Egyptian nationalism in 1922 the British High Commissioner in Egypt, Lord Allenby, unilaterally proclaimed the independence of Egypt, the Monarch was never able to exert anything more than nominal control of the economy and British interests remained paramount over the next thirty years (Tignor, Citation1984, p. 44).

It is consequently clear that potentially British business interests could have been placed in a strong position, given the extent to which Egypt was subjugated to control from London. This raises another issue that Berbenni (Citation2023) examined regarding Italian multinational banks, namely, the ‘liability of foreignness’ which Zaheer (Citation1995) highlighted as one of the great challenges faced by all multinational firms. Zaheer (Citation1995) was especially concerned with the impact that the political, economic and cultural differences between home and host countries would have on performance. Above all, Zaheer (Citation1995, p. 341) felt that this is an issue linked to costs ‘arising from the unfamiliarity of the environment, from cultural, political, and economic differences, and from the need for coordination across geographic distance, amongst other factors’. Berbenni (Citation2023, p. 728) has agreed that this was certainly a problem which seriously undermined the profitability of Italian-owned banks operating in Egypt, especially given both the policies pursued by the indigenous government and the intensification of nationalist feeling that precipitated the creation of Banque Misr in 1920 (Davis, Citation1983). At the same time, while British banks might well have expected some degree of preferential treatment by a regime that up to the 1940s was closely controlled by London, it will become clear that little support was forthcoming. Indeed, British banks were just as vulnerable to a ‘liability of foreignness’ as any other foreign bank, further confirming the challenges facing management and investors at that time.

Running in parallel with these developments was the domestic government’s emphasis on diversifying away from its reliance on cotton and inducing more indigenous business enterprise. While the boom in raw cotton production had created enormous opportunities, in 1914 70% of the total capital and debentures of Egyptian joint-stock companies was owned abroad (Crouchley, Citation1936, p. 155). Moreover, the export of raw cotton and cotton seed represented around 90% of total exports up to World War I, and by 1920 industrial undertakings represented just 6% of total joint stock company capitalisation (Egyptian Ministry of Finance, Statistics Department, Citation1928). These structural imbalances were addressed by a commission set up by the Khedive and composed of Egypt’s most prominent businesspeople, resulting in a 1918 report that advocated rapid industrialisation owned and managed by Egyptians (Tignor, Citation1984, p. 17).

The most dramatic consequence of this report was the creation of the Misr group of companies, headed by Talaat Harb Pasha, one of that era’s most energetic Egyptian entrepreneurs who was an ardent nationalist (Davis, Citation1983, pp. 80–82). As we have already seen, one of these companies was Banque Misr, founded in 1920 as the first indigenously owned bank and what would become a formidable competitor to the foreign-owned banks that had to date dominated the Egyptian scene. Although we earlier noted that Islamic doctrine prevented its believers from directly participating in banking, as Davis (Citation1983, pp. 120–121) has noted, the surge in nationalist sentiment after World War One provided a justification for Banque Misr’s creation. It is also noticeable that investors were recruited from a wide spectrum of Egyptian society, while Banque Misr’s deposits and accounts surged in the early-1920s as nationalist ferment continued unabated (Davis, Citation1983, pp. 116–117).Footnote2

The timing of these initiatives was also crucial, in that by 1919 there was intense Egyptian distaste for colonial rule, precipitating extensive unrest in that year which forced the British to accede to a diluted form of independence in 1922 (Davis, Citation1983, p. 50). This provided the government with an opportunity to introduce in 1923 what has been described as its ‘Egyptianization’ measures. These stipulated that a minimum of two Egyptian nationals should sit on any locally registered company boards, while one-quarter of all issued shares should be offered for purchase in Egypt (Board of Trade, Citation1948). The quotas were also extended in 1927 and again in 1947, creating a very different environment that reflected the changing nature of the Egyptian business scene (Beniamin et al. Citation2023).

This brief survey has only provided general details on the economic and political environment in which foreign banks were created and operated. It is consequently necessary to focus down on a single case-study of the Ionian Bank, and in the process search for clear answers to our research questions relating to the reasons why it moved into Egypt and how it coped with the organisational and competitive challenges that management faced at different times in its relatively brief time in that country. This will extend our understanding of these processes, adding significantly to what Jones (Citation1993) and Berbenni (Citation2023) have written about foreign commercial banks in Egypt. Although Saul (Citation1997) and Cannon (Citation2001) have also contributed to this literature, it is important to add that as they focused on a French-owned mortgage bank, its experience would have differed from commercial banks such as Ionian.Footnote3

4. Ionian Bank’s move into Egypt

Founded in 1839 with a Charter from the United States of the Ionian Islands,Footnote4 the Ionian Bank was not only one of the oldest British multinational banks, it was also unusual for initially focusing on European markets. Its early history has been covered by several historians (Cottrell, Citation2005, Citation2007; Jones, Citation1993; Phylaktis, Citation1988), highlighting how the Ionian State’s resident agent in London had provided the initiative for its creation by offering the exclusive right of note issuing in the territory as an inducement to a syndicate of London bankers and merchants (Orbell & Turton, Citation2017). This syndicate had also been active in forming the first British multinational banks, the Bank of Australasia and the Union Bank of Australia, and five of the former’s directors also sat on the Ionian board (Jones, Citation1993, p. 15).Footnote5 Charters of incorporation were sought and granted in both the Ionian Islands (1839) and Great Britain (1844), while over the period 1839–1841 the initial £100,000 capital was provided by a combination of the founding directors (who together invested £14,775)Footnote6 and a large number of London-based investors. Ionian’s early growth was also facilitated by another founding director, Stephen Wildman Cattley, a merchant who traded in currants, earning it a reputation as the ‘currant bank’ (Jones, Citation1993, p. 32). As the original prospectus envisaged the Bank as ‘the nucleus of a great and important undertaking operating in the Mediterranean, the Adriatic, and the Levant’,Footnote7 this illustrates how the Bank built a vibrant business linked to both note issuing and financing the trade in agricultural produce. Apostolides and Gekas (Citation2012) discussed the relationship between the Ionian Bank and the British authorities until the 1920s, given that the focus of the Bank’s operations was in Greece and Cyprus where it maintained a monopolistic or at least dominant position.

When in 1864 Britain ceded control of the Ionian Isles to Greece, the Court of Directors moved swiftly to seize fresh market opportunities. Firstly, Ionian was granted exclusive note issuing rights in that country, while by 1873 the branch head office had been transferred from Corfu to Athens. Although in 1883 Ionian was converted into a British joint stock company, and the nexus of power remained with the Court of Directors based in London, progressively the organisation was taking on a distinctly Anglo-Greek character. Firstly, prominent Greek businesspeople were appointed to the Court from 1863,Footnote8 adding considerably to its knowledgebase and connectivity with a business community that boasted an extensive diaspora linked to international shipping and mercantile activities. These links were further enhanced by the formation in 1864 of an Athens Advisory Council composed of local businesspeople who could keep the Court fully appraised of Greek economic and political developments. Secondly, by 1879 the Shareholders’ Register reveals that Ionian was selling equity to investors in Greece, Corfu and Malta, further enhancing the Anglo-Greek character of a firm that was firmly embedded in that country.Footnote9 It was also significant that when in 1891 the Court of Directors decided to have a permanent chairman,Footnote10 they chose a leading Greek merchant, Parasqueva Sechiari, while from 1921 to 1948 this role was performed by Sir John Stavridi, another prominent member of the Greek diaspora based in London.Footnote11

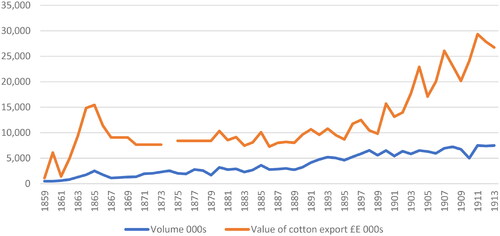

Given that Ionian would appear to have established a viable business in Greece, it is essential to ask why the Court decided early in the twentieth century to open a branch in Egypt. This move was first mooted in 1905, when the chairman, Falconer Larkworthy,Footnote12 was requested by the board to visit Egypt and spend two weeks meeting with fellow bankers, lawyers, the Consul-General of Egypt (Lord Cromer) and local businesspeople. Larkworthy was also assisted by the extensive range of data generated by the Egyptian government on land values and rates of indebtedness in the country, providing detailed and favourable comparisons with the Bank’s experiences in Greece. One of the key points he noted was that the strong British presence in Egypt provided a sound legal basis for bad debt recovery, while the booming cotton industry would also offer considerable opportunities to engage in trade finance with the Greek business network. As reveals, while the volume of Egyptian cotton exports was stable from the 1890s, in value terms there was a significant increase, providing an enormous incentive to move into that trade. Larkworthy consequently advised the board to move speedily, because ‘there is to me no room for surprise that at present so many banks are hankering after the flesh pots of Egypt’.Footnote13 The Athens Advisory Council was also supportive of this proposal,Footnote14 reinforcing the view that Larkworthy was keen to exploit the extensive connections that Ionian had established with the Greek business community.

In spite of Larkworthy’s optimism, however, and typifying the highly conservative approach of British bankers, his fellow directors decided against taking action at that stage.Footnote15 Larkworthy was clearly disappointed with this decision, because over the following two years he lobbied the Court to support a move to Egypt, finally winning them over in 1907 when the first branch was opened in Alexandria.Footnote16 While superficially this looked like a poorly timed decision, because it coincided with a severe global financial crisis brought on by the ‘Bankers’ Panic’ originating in the USA (Baster, Citation1935, p. 71).Footnote17 Ionian was clearly able to ride this storm. As the Court noted at the 1910 AGM, by that time the financial resources of existing foreign banks in the country had been exhausted, while Ionian’s capital and credits were intact, providing an initial boost to its status.Footnote18

This narrative, however, fails to provide a complete rationale behind Larkworthy’s advocacy of Egypt as a viable base. Specifically, to what extent does Dunning’s OLI paradigm explain this move? In terms of ownership advantages, it is clear that Ionian’s extensive links with the Greek diaspora were extremely significant. As Casson (Citation1990, p. 14) has explained, competitive advantage can be gained by developing the ability to synthesise information from personal contacts and information networks, a process which helped the Bank to spot profitable opportunities. It was also noticeable that not only did Egypt and Greece maintain strong trading ties, but also Greeks constituted the largest foreign community in Egypt at the start of the twentieth century. It was estimated in 1910 that Greeks represented one-quarter of the population in Alexandria, Egypt’s principal economic centre (Egyptian Ministry of Finance, Statistics Department, Citation1910, pp. 30–33). In 1902, this community had established its own chamber of commerce in Alexandria (Kitroeff, Citation1989, p. 134), further facilitating the transmission of market information. As a consequence, Greek investments in Egypt expanded considerably, ranking fourth behind the major European investors (Britain, France and Belgium) (Tignor, Citation1984, p. 42). The bulk of this money was focused on cotton, the Greek business community having achieved a dominant position in each stage of the process, from cultivation through to its export. In addition, Greek businesspeople dominated the lucrative tobacco trade and moneylending (Egyptian Ministry of Finance, Statistics Department, Citation1909), providing Ionian management with a strong incentive to establish a branch in that country.

These ownership advantages were also complemented by the perceived benefits of locating in Egypt directly, rather than operating indirectly through correspondents or agents. Crucially, by exploiting their existing contacts in the Greek business community, it would be possible to establish a sound business, given the significance of direct personal dealings in banking at that time. As Larkworthy had also noted,Footnote19 Egypt’s economy was benefiting considerably from the expansion of cotton cultivation, a sector that was dominated by the Greek diaspora. Having noted these positive incentives, however, it is also important to stress that in spite of its increasingly Anglo-Greek character, Ionian’s competitive position was never secure in Greece. Specifically, Ionian was still regarded as a foreign bank, especially by both the National Bank of Greece and the indigenous government, both of which aspired to much greater indigenous control of financial dealings (Jones, Citation1993, p. 106).

The first decisive move in this respect was the 1880 agreement with Ionian, which stipulated that as a condition of continuing to control note issue not only would it need to open new branches in agricultural regions, but also the Bank was obliged to employ 40% of its paid-up capital in agricultural loans and 25% in mortgage lending (Jones, Citation1993, p. 37). In addition, in 1885 the Bank was asked by the national government to provide a loan of 3.5 million francs (for 20 years at 2%),Footnote20 while in 1888 a further £40,000 was loaned to the same customer.Footnote21 Two years earlier the town of Corfu had borrowed 150,000 francs from Ionian.Footnote22 Nevertheless, it is clear that the relationship with national government continued to deteriorate, because in the 1890s Ionian was obliged to reduce interest rates on agricultural loans as a sign of its commitment to the welfare of the Greek economy.Footnote23 Finally, in 1900 the National Bank of Greece was granted a licence to issue notes in competition with Ionian, persuading the Court that its Greek charter would not be renewed.Footnote24

This situation clearly created some internal friction within the Bank, because while in 1905 the Court offered to sell its note issuing rights to the National Bank of Greece for a cash payment of £62,800, the Greek shareholders voted against it and the agreement was never signed.Footnote25 As a result, although Ionian remained a bank of issue for another 15 years,Footnote26 the privilege expired in 1921 and was transferred, without compensation, to the National Bank of Greece. It is consequently clear that the location advantages associated with the decision to expand into Egypt were at least partly driven by the anticipated changes to Ionian’s status in Greece as a note-issuer, complementing the ownership advantages linked with its connections to the Greek diaspora.

When it comes to the consideration of internalisation advantages, while as we shall see later these were complicated by some principal-agent issues, Ionian was sufficiently confident of its organisational capabilities that the Court was willing to invest in its own Egyptian operations, rather than rely on correspondents or agents. The internal organisation had been evolving since the 1880s especially, because in April 1888 a Balances and Investments Committee had been formed, composed of George Scaramanga, Michele Schilizzi and Ernest Cooper, with responsibilities for advising the Court on future investment strategies.Footnote27 In 1891, Scaramanga also joined Parasqueva Sechiari (the first permanent chairman) and Thomas Usborne on a committee designed ‘to consider the means of improving the bank’s business’.Footnote28 Although the chairman died suddenly in July 1900, this did not interrupt the process of continued internal change because Sechiari was replaced by the highly experienced Falconer Larkworthy,Footnote29 while in October 1901 John Stavridi was brought onto the Court.Footnote30 These two directors would play a key role in Ionian over the course of the next five decades, not least in persuading the Court to open branches in countries with substantial Greek communities.

Having noted these important appointments to the Court, it is necessary to describe how this body would appear to have conducted the Bank’s business. By 1902, the Court was composed of thirteen directors with skillsets that ranged from merchanting to stockbroking and merchant banking. The minute books reveal that business was conducted at a brisk rate, with meetings starting at 12 noon and rarely lasting more than an hour. Indeed, it is clear from those minutes that only routine business associated mostly with inspecting the financial state of the Bank was their principal concern. When it came to important strategic issues such as the move into Egypt (and later, Corfu), much of the discussion would appear to have happened outside the Court meetings, involving the chairman, general manager and members of the Advisory Council. It is also clear that World War One had a devastating impact on the Court, in that it resulted in the exclusion of all directors not residing in Britain. By June 1917, there were only five directors and after peace was restored in 1918 the Court did not move to restore its size to pre-war levels. By the 1930s, there were only four directors on the Court, again indicating the recognition that most of the Bank’s business was done by the general manager interacting with the chairman and their contacts in either Greece or Egypt. Nevertheless, Ionian was able to expand its activities and compete effectively in several markets, extending its reputation as the ‘currant bank’ to include cotton, tobacco and general banking businesses.

While as we shall see in the next section Ionian experienced some organisational challenges arising from its geographical dispersion, there seems little doubt that in terms of ownership, location and internalisation the Bank’s decision to open a branch in Egypt had a sound rationale. It is now necessary to evaluate this branch’s performance, focusing especially on its organisational evolution and the challenges associated with competing for business in a country that was susceptible to both global economic trends and surging nationalism.

5. Operations and organisational structure

Although Larkworthy’s business case in his 1905 report was partially based on providing mortgages for high-class urban properties and landed estates,Footnote31 it was the cotton trade which mostly occupied Ionian Bank from 1907, and specifically loans to the Greek business community involved in growing and trading in this commodity.Footnote32 This would require senior management to develop a new skillset, in that while Ionian had successfully traded in Greek agricultural produce since the 1830s, none of the directors had any experience of the cotton industry. It was a steep learning curve, with success largely contingent on the appointment of appropriately experienced staff to run the branch and what by 1909 were seven agencies. As the key to success was regarded as ensuring that the Bank would work intimately with the Greek business community in Egypt, it is interesting to note that the first branch manager was P. Athenassu, who had been transferred from the Greek operation in May 1907.Footnote33 By 1922, most of the forty-nine staff employed by Ionian in Egypt were Greek, including the heads of both the cotton department located in Alexandria and the seven agencies that it had established in the cotton-growing regions.Footnote34

In order fully to understand how this structure worked, it is necessary to discuss the basic features of cotton cultivation and trading (Beniamin, Citation2020, pp. 59–64). The key period was the growing season between September and February, when cultivators required finance to see them through to the harvest (February to May) in the form of payments in advance for the entire crop. While small growers mainly relied on merchants and other middlemen for this liquidity, the medium-sized and large cultivators depended on banks for financial support (Owen, Citation1969, p. 208), placing a premium on the relationship agents developed with that sector. The 1912 ‘Five Faddän’ Law also prohibited banks and moneylenders from foreclosing on smaller growers, increasing the risks associated with this sector of the industry (Davis, Citation1983, p. 75).Footnote35

Another vital part of the process was the need to gin the raw cotton, and as the Greek business community had since the 1860s pioneered mechanised ginning, they had built a powerful position in that sector (Karanasou, Citation1999). After ginning, the cotton was transported to warehouses in Alexandria which were owned by the banks and leading merchants, and then traded in the market based in the Minet-el-Bassal district. This was where exporters would place orders for the qualities and quantities required, with speed and knowledge being of prime importance in ensuring that the stock was placed with a buyer.Footnote36 The market was regulated by the Alexandria General Produce Association, which had been founded in 1883 by the largest trading firms. Of its twenty-four founding members, fifteen were Greek, including the president and vice-president (Kitroeff, Citation1989, p. 79), placing that community at the heart of an industry which was fundamental to Egypt’s economy.

In coming to terms with these features of the Egyptian cotton industry, Ionian was well placed to secure a viable position, given its extensive links with the Greek diaspora. Apart from establishing seven agencies in cotton growing regions by 1909, the Bank also purchased both a warehouse and a cotton selling office at the heart of the cotton marketplace in Alexandria, providing the facilities to ensure that clients’ accounts could be liquidated speedily at the best possible price. As Ionian management swiftly learned, when cotton was carried over from one season to another, it was difficult to sell, forcing the Bank to accept lower prices.Footnote37 Above all, though, it was imperative that the agents should develop a close working relationship with both the growers and ginning establishments, providing a steady flow of business at the key points in the cycle.

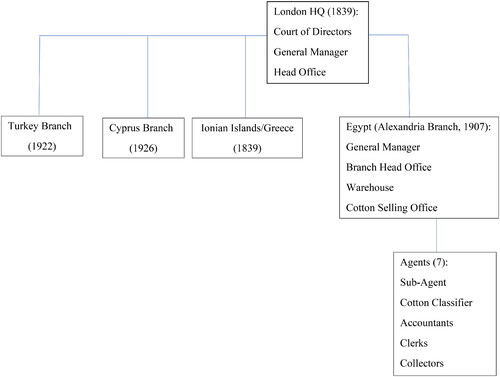

This agency structure was different to that prevailing in the British banking system,Footnote38 where an agent was not typically an employee of the bank and maintained a degree of freedom to enter into loan agreements with borrowers on a bank’s behalf (Barnes & Newton, Citation2018, p. 449). In the Egyptian case, the agency was a branch that was controlled by the head office in Alexandria, with the agent operating as a sub-branch manager, alongside a sub-agent, a cotton classifier, accountants, clerks, and collectors. This structure is illustrated in , which outlines how the Court had adopted a regional management structure, replicating what other overseas banks were doing at that time (Jones, Citation1993, p. 168). As the Bank had by 1918 23 branches and agencies, of which 15 were in Greece, this would have significantly increased the challenges associated with managing this geographically dispersed organisation. Moreover, by 1929 Ionian was represented by 44 branches and agencies in four different countries (Greece, Egypt, Cyprus and Turkey), reflecting the general success with which the London Court had expanded its operations at a time when global economic conditions were not entirely conducive.

Having made this claim, however, as it is clear from that by the 1920s Ionian was operating an organisation with various levels of delegation, it is questionable whether the Court was always able to impose its own ideas on various parts of the business. While clearly the general manager of the Egyptian branch was a key figure in the structure outlined in , of pivotal importance to the success of the venture would be the agents and sub-agents who worked directly with clients in the seven regional branches. Most of these agents were Greeks who could speak Arabic, along with some indigenous Egyptians.Footnote39 Their functions ranged from managing loans and ensuring the creditworthiness of both the borrower and guarantor, as well as contracting with growers when cotton was sown and estimating the prospective yield at a specified quality. The agents were also responsible for hiring competent and reliable classifiers, who were the second highest paid in the agency after the agent because they had to establish the grade of the cotton and supervise the ginning process.Footnote40 It was consequently vital to the efficiency of Ionian’s operations to recruit agents with appropriate ‘competency and reliability’.Footnote41

Above all, reliability and speed were the two characteristics of the operation, because the best prices were always secured when the ginned cotton arrived fresh in Alexandria’s cotton marketplace. This required effective co-ordination between the head office, the agents operating out in the provinces, and the sales office in Alexandria.Footnote42 The sales office would also need to monitor cotton prices, because having committed its capital at the time when the cotton was planted, Ionian was naturally keen to cover all expenses and secure a return on its investments. If cotton prices ever fell, or the cotton crop was not as bounteous as predicted, this could result in intense competition between the foreign banks for this business, exacerbating the difficulties of competing in this sector. At the same time, it was essential for the agents to check the creditworthiness of borrowers,Footnote43 given that foreclosure procedures could result in capital being tied up in expensive legal cases.

In order to ensure that the organisation worked as efficiently as possible, the London-based general manager constantly monitored the Egyptian operation through the imposition of monthly reporting on all aspects of the business.Footnote44 The Ionian general manager for the period 1921 to 1935, P.N. Caridia, also made frequent visits to Egypt from his base in London,Footnote45 at times conducting an assessment of each member of staff in the Alexandria head office.Footnote46 It is nevertheless clear that there was some friction between the management in Egypt and the general manager in London, largely because the general manager for Egypt by the 1920s, Herbert Atkinson, often made fresh advances against the Court’s instructions. Indeed, Atkinson was often blamed for continually following his own lines of policy, which occasionally ran contrary to the policies laid down by the Court.Footnote47 For example, while the Court instructed Atkinson several times to reduce his staffing complement, he continually resisted this cost-cutting measure because of the impact it would have on staff morale.Footnote48

Having revealed these principal-agent tensions, it is also clear that the management in Alexandria had similar problems with the agents in the provinces, and especially the latter’s continual demands for more delegated authority. In order to understand this situation, one must bear in mind that the Bank extended advances against two types of security: credit against a mortgage, which was normally for double the amount of credit and would not exceed one-third of a property’s value;Footnote49 and credit against personal guarantees from a guarantor (who had to be wealthier than the borrower). Reflecting the illiquid nature of mortgage-based credits, by 1922 60% of the Bank’s total credits were against signature only and 40% against mortgage.Footnote50 Specific margins also had to be maintained against the cotton loans, in most cases not less than 25%, calculated on the cotton selling price in Alexandria. At the same time, as the Bank’s financial resources were fully employed in financing cotton cultivation within a year of the Egyptian start-up,Footnote51 the bank tried to retain the goodwill with its clients,Footnote52 emphasising the crucial importance of the agency network established at the outset.

Bearing in mind the need to monitor the activities of agents who operated at a distance from the Alexandria branch, it is clear that the general manager was often hard pressed to ensure that there were minimal levels of opportunistic behaviour. As Larkworthy noted at the 1912 annual meeting:

In regard to management, and to the question of up-country agents each bank has to find its own way out of the difficulty. Success or failure turns on its methods and on its choice of men of local experience, and on their prudence and faithfulness in adhering to instructions; and on the effectiveness of the bank’s system of inspection. As in other parts of the East, personality is everything in Egypt and the personal equation, or the liability of human agents, who are not altogether machines, to aberration, or to get out of gear, has always to be borne in mind.Footnote53

6. Financial performance

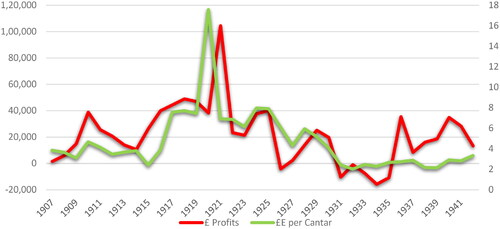

While it is clear that Ionian experienced some severe principal-agent challenges, these were not the only problems faced in Egypt, given both the intense competition between banks and the stagnation experienced in the interwar era by one of its major customers, the Lancashire cotton industry (Singleton, Citation1991). illustrates how Ionian’s profits in Egypt were almost directly linked with prevailing cotton prices. The key problem with cotton prices was the impact this inevitably had on the margins Ionian could make on its loans to cotton growers. The problems were especially acute in the early-1920s, when prices fell drastically after the wartime inflationary boom, resulting in many customers’ accounts moving into deficit. It was also in this period that the Egyptian government started to interfere with the ways in which land was used, reducing in 1920 the cotton plantation area by one-third in order to produce more food for an expanding population.Footnote56 While one might have expected the price of cotton to have risen in these circumstances, reveals that a global recession ensured that for the remainder of the interwar years the sector experienced difficult market conditions.

Figure 3. Ionian Bank’s profits in Egypt* and average cotton prices**.

Sources: Bank’s profits: IB, 2/6 & IB, 2/7 and IB, 3/24; cotton prices: National Bank of Egypt (Citation1948). *Profits are in Sterling Pound and before interest paid on head office loans. 1907–1917: mid‐January financial year‐end (1917 ends in mid‐January 1918); 1918–1921: December year‐end; 1922–1935: August year-end; 1936 – Onwards: December year-end. **Cotton price is for one cantar, which is equivalent to 100 ib (pounds).

Such were the challenges that the London Court even contemplated closing the Egyptian branch in 1931, given the bleak prospects in cotton. In view of the potential impact that this move could have had on Ionian’s Greek branch, however, it was finally decided to offer the general manager a three-year trial, on condition that ‘every effort would have to be made by the Egyptian organisation to effect further economies as and when become possible say 10% cut in salaries’.Footnote57 Although as we noted earlier the Egyptian branch general manager refused to cut his staff, the trial was clearly successful, because Ionian remained fully operational in Egypt after the trial ended.

Apart from reducing the margins Ionian could make on its loans to cotton growers, another acute cause of concern after World War One was the intense competition from other foreign banks and the aggressive Banque Misr. Before going into an analysis of this issue, however, it is worth noting that as Panza and Karakoç (Citation2021) claim, one of the major factors stimulating the growth in cotton cultivation during the interwar period was the relatively easy access to credit that arose as a direct result of the competitive banking environment. As we shall see later, given the ways in which Banque Misr especially and some of the Italian banks operated, this ensured that large landowners especially were able to secure cheap credit.

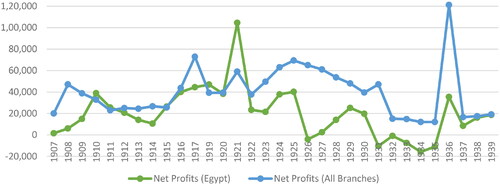

While the Court had been aware in 1907 that it was entering a market which already had several well-established competitors, by 1914 Ionian had succeeded in establishing a prominent position in the cotton sector by mobilising its links with the Greek business community. At the same time, it is difficult to be precise about Ionian’s performance in Egypt, given that like other foreign banks it did not produce financial performance data for each of their branches. This creates a challenge when interpreting the financial data provided by Jones (Citation1993, p. 450), because this is for the Bank as a whole. Another issue relates to the difference between ‘Published net profits’ and ‘Real profits’ in Jones’ tables, with the latter proving to be distinctly greater than the former. Again, however, as both columns relate to the Bank as a whole, and in spite of extensive investigations in the Ionian archive, it is difficult to detect the contributions made by the Egyptian branch for the whole period.

Looking more generally at this issue, one must remember that British multinational bank profitability sometimes disguised their profits by maintaining high reserves or transferring money to a secret reserves account before reporting their published profits (Jones, Citation1993, p. 75). In this way, real profits might have been understated. Jones (Citation1993) found for the sample banks he surveyed that the real profits were often higher than the published ones, especially up to the outbreak of the First World War. In calculating inner reserves, Jones tried to exclude the figures within the inner reserves made for contingencies, bad debts and other specific needs. His figures for inner reserves represented the free reserves that were held off-balance sheet and were not linked to any known contingency. As Jones (Citation1993) calculated inner reserves based on the accounting ledger for the Bank as a whole, however, the archive does not provide figures for the Egyptian business on a standalone basis.

To partially address this problem, two measures can be used. Firstly, profitability ratios (see ) are derived from net profits before reserves, as it could be the case that published reserves overestimated bad debts and losses. Secondly, figures can be estimated for the Egyptian branch of the Ionian Bank by analogy. The ratio of inner reserves for the entire Bank, as a percentage of real profits, can provide an estimate of the Ionian Bank management’s appetite in this respect in comparing these reserves against real profits. Making some calculations from Jones’s data, the average difference between published profits and real profits as a percentage of published profits for the years 1907–1956 was 96%; that is, the real profits were higher than the published figures by this percentage. If this same ratio of underestimated profits was the case in Egypt, rather than substantial returns, the Bank generated decent levels of profits in that branch.

Table 2. Profitability of the Ionian Bank in Egypt on capital supplied by the Head Office (before interest and reserves)

Taking this point further, by extracting information gleaned from Bank correspondence and shareholders’ meetings, has been generated to demonstrate that while the Egyptian business experienced some barren years (1926 and the early-1930s), in general it was a profitable operation. At the same time, it is worth stressing that the first phase of operations up to 1919 proved to be distinctly more profitable than the 1920s and 1930s. In the period 1912–1917, the Egyptian branch returned 16% on capital borrowed from London, representing a net profit of 11% after paying interest of 5% on the funds loaned by the Court.Footnote58 Over the entire period 1907–1929, however, the average percentage earned on funds supplied from the headquarters, before deducting interest, was just 8%. This demonstrates that after a reasonably good start, the economic environment deteriorated after 1919, with competition from other foreign banks and Banque Misr exacerbating the collapse in cotton prices.Footnote59 Although Ionian was able to maintain its proportion of the Egyptian cotton trade at an average of 11% throughout the interwar era,Footnote60 results from the Egyptian branch fluctuated considerably.Footnote61 Overall, Egypt remained a viable business area, even if after 1920 especially profitability was declining (see ). Specifically, the Egyptian branch continued to operate as a means of supporting the Greek business community to which the London Court was closely affiliated.Footnote62

Figure 4. Ionian Bank’s net profits in £: Egyptian branch & entire bank.

Source: for the entire bank: Report of Proceedings of the Annual General Meeting, IB, 2/2, IB, 2/4; for Egypt: author’s calculations based on the following files: IB, 5/86; IB, 6/3; IB, 6/90; IB, 24/1/25; IB, 24/7/1.

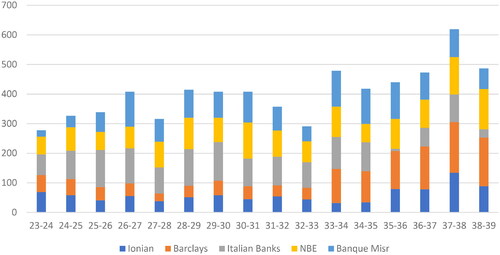

It is important to highlight that the Bank’s operations in Egypt had expanded swiftly over a brief span of time, achieving a prominent role among the foremost financiers of Egyptian cotton within a few years of its establishment. Footnote63 Yet, the situation changed in the 1920s, when operations such as Banque Misr and Barclays DCO started to take a much more dominant position in the cotton market. This can be illustrated by comparing the amount of cotton it traded on the Alexandria cotton exchange with its main competitors, an exercise presented in . It is clear from that with the exception of 1937–1938 Ionian was a relatively minor player, especially compared to the National Bank of Egypt, Barclays DCO, Banque Misr and the two Italian banks. It is especially impressive how from a standing start in 1920 Banque Misr was able to secure so much business, achieving the largest share of the cotton trade in 1926–1927 and matching, even exceeding in the early-1930s, its rivals’ shares thereafter. Ionian’s increased share in the late-1930s can be wholly attributed to the geo-political fallout from Italy’s invasion of Ethiopia in October 1935 (Berbenni, Citation2023, p. 731), because such was the weakness in the Italian financial system thereafter that its multinational banks lacked the resources to compete in countries such as Egypt.

Figure 5. Cotton arrivals at the Alexandria cotton exchange by bank, 1923–1939 (thousands of bales).

Source: Berbenni (Citation2023, p. 726).

Note: ‘Italian banks’ equates to Cassa di Sconto e di Risparmio and Itelegi combined.

When analysing this competitive environment in greater detail and its impact on Ionian’s performance, one is faced with the challenge of interpreting the veracity of the Egyptian management’s claims. While the Court was constantly exhorting Alexandria to improve its profitability, the local management would respond by noting the rate-cutting activities of both the Italian-owned banks and the first Egyptian-owned bank, Banque Misr.Footnote64 As Atkinson claimed, these banks secured large turnover by offering credits with little or no margins which were governed by loose credit terms and at low interest rates.Footnote65 While one could argue that reports of this kind were purely defensive in nature, it is important to stress that other British sources noted similar trends. For example, a report provided by an employee of the Bank of England described how some banks even sent their employees into the villages touting for business and allegedly forcing money on potential borrowers.Footnote66 A British Consular Agent also commented on the propensity of some of the smaller foreign banks to have been bent on pushing business at any cost.Footnote67 Banque Misr was especially aggressive, purchasing a large cotton warehouse in the cotton marketplace at the time of its formation in 1920 and filling it with a significant portfolio of cotton advances (see ). Another worrying feature of the mid-1920s that we noted earlier was the emergence of Barclays DCO, a wholly-owned subsidiary of Barclays Bank, one of the largest banks in the world (Ackrill & Hannah, Citation2001; Jones, Citation1993, p. 405). Although Crossley and Blandford (Citation1975) note that this operation was one of the weakest subsidiaries in the Barclays group, largely because of the intense competition in Egyptian banking, illustrates how it was able to increase its share of the Alexandria cotton trade, backed up by the resources of its parent company.

Of course, while it is clear that Barclays DCO would never have indulged in the rate-cutting activities of other foreign banks and the Misr operation, there is no doubt that widespread concern was being expressed about the financial environment that prevailed over the interwar era. Sir Edward Cook, the Governor of the National Bank of Egypt during the 1930s, was so concerned with what he regarded as the unsound banking principles followed by many banks that he wrote an extensive report for the Bank of England.Footnote68 He warned that credit facilities were so abundant that borrowers had adopted an extremely lax attitude towards repaying debts, contrasting this unfavourably to behaviour in Britain. Lloyds Bank officials had also noticed this in the 1920s,Footnote69 a factor which could well explain why having acquired the Egyptian business of Cox and Company in 1923, this bank had sold out to the National Bank of Egypt in 1926.Footnote70 In the same year, Banque Belge et Internationale en Égypte also dissolved its cotton business because of the acute competition.Footnote71

The intense competition and lack of cooperation across banking and the cotton sector were clearly major reasons why the Ionian Court needed to monitor performance very closely after 1919. Moreover, it is clear that Ionian’s Egyptian management did not exaggerate the challenges of operating in such a competitive environment. The lack of a clearing house for these industries was especially noticeable, because this limited the exchange of credit information and accentuated the tendency of banks to operate in a highly secretive way. Only a handful of banks published annual reports that separated the results for their financial activities in Egypt (Tignor, Citation1981, p. 115), highlighting both the weak regulatory environment that existed throughout this period and the difficulties associated with controlling foreign-controlled banks.

Although in the 1920s there were various attempts to regulate banking competition in Egypt, including meetings convened by the National Bank of Egypt,Footnote72 the level of distrust across the banking sector frustrated these initiatives. It was 1937 before an association of banks became a reality, when as a result of an initiative from Crédit Lyonnais, the Conference des Banques was formed. Ionian agreed to sign up to this body, along with fifteen other banks. As its chief objectives were maintaining relations between members, exchanging information and determining acceptable tariffs for banking services (National Bank of Egypt, Citation1948, pp. 102–103), this provided a much more conducive environment in which foreign banks could operate. After the Second World War, this trade body was even able to meet government ministers to discuss how the cotton crop should be managed, determining an agreed interest rate that all banks would charge.Footnote73

As these developments were only evident from the late-1930s, however, Ionian Bank and its rivals were obliged to endure extremely challenging conditions for most of the interwar era. In those circumstances, the Court in London maintained an extremely conservative stance based on ‘safety first’, even if this resulted in a temporary reduction in turnover.Footnote74 This also explains why in 1931 the Court was considering the closure of its Egypt branch, while a year earlier the Court debated Caridia’s proposal to focus only on banking, rather than compete in the cotton sector.Footnote75 Although the Court decided to continue financing the cotton trade,Footnote76 Caridia renewed his campaign to reduce costs across the Egyptian operation.Footnote77 As we noted earlier, however, the management in Egypt viewed the situation differently, believing that the objective should be to maximise profits by lending more money to the cotton trade.

These discussions also raise another issue, namely, Ionian’s status as a medium-sized bank with limited resources. As most wealthy Egyptians did not deposit their money with banks, preferring instead either to buy gold and diamonds or invest in stock exchange securities, it was extremely challenging to generate funds in that country.Footnote78 By 1935, Ionian’s Egyptian deposits amounted to £395,683, compared to over £2.1 million in Greece and £223,200 in the much smaller Cyprus operation.Footnote79 It is also worth noting again that as Jones (Citation1993, p. 450) presents data for the Bank as a whole, it is difficult to use this as a base for judging the Egyptian branch’s performance. It is nevertheless clear that the branch relied heavily on funds supplied by the London headquarters in order to compete in the cotton trade. Indeed, the Alexandria office frequently complained that covering expenses and making profits was difficult with the level of funds supplied to them by the headquarters,Footnote80 especially when competing against larger banks with greater resources.

Having revealed how Ionian failed to sustain its level of profitability (), it is important to add that because the Egyptian branch was largely reliant on funds provided from London, it could hardly have been accused of extracting substantial profits from Egypt. We noted earlier that some Egyptian scholars and most politicians had accused these institutions of exploiting the economy and repatriating abundant profits to their home base. With specific regard to Egypt, though, because foreign banks were unable to generate substantial deposits from local customers, the bulk of the funds to maintain operations came from their own capital and accumulated reserves, along with other sources such as borrowings (Tignor, Citation1981). Moreover, as we have just seen, Ionian’s performance deteriorated after the solid start of the pre-1920 years, prompting the Court to agitate continually for improved profitability.

In order to overcome this constraint on its expansion, at times in the interwar era Ionian sought support from other banks. John Luard, the acting general manager in Egypt, made the case for an approach to one of the big banks in Britain,Footnote81 resulting in Caridia talking to both Barclays Bank and the Anglo-Egyptian Bank.Footnote82 Neither set of discussions produced any results. A year earlier, the management had initiated negotiations with the Governor of the National Bank of Egypt.Footnote83 These discussions were extremely protracted, because by 1925 nothing had been agreed. Luard had even suggested that the National Bank of Egypt could appoint one director onto the Ionian Bank’s London Court, with another member on the Alexandria Advisory Committee, as a condition of providing additional borrowing.Footnote84 Although the London Court objected to this deal and it was never implemented,Footnote85 the National Bank of Egypt agreed to provide an overdraft facility of £200,000 without any special arrangements.Footnote86 This additional liquidity proved to be extremely helpful over the following decades, at times increasing to £300,000. Nevertheless, it was clear that Ionian’s financial resources proved to be a major constraint on its growth, especially with significant rivals such as Barclays entering the Egyptian market in 1925.

Another way of increasing the financial resources at their disposal was to open new lines of business, specifically to attract more local deposits and support the cotton business. For example, attempts were made to engage in financing petroleum shipments between Egypt and Greece,Footnote87 while the Bank solicited part of the business of Ford Motor Company in Egypt.Footnote88 Although this resulted in some growth in the banking department, the requirements of the cotton department continued to exceed these deposits.Footnote89 As a consequence, in the difficult year of 1930 Caridia warned the Court that:

It is disappointing that the deposits of the bank do not show signs of expansion … The proper function for the capital of a bank doing a deposit business such as ours, is for it to be available in a readily realisable form, to meet an emergency anywhere. It is feared that in the absence of a substantial increase in your deposits, a drastic curtailment of lending activity in Egypt is inevitable.Footnote90

7. Conclusions

By examining foreign banking in Egypt through the prism of the Ionian Bank between 1907 and 1939, we have been able to provide deep insights into our principal research questions associated with the reasons why it moved into Egypt and how foreign banks maintained their operations and managed risks. We have curtailed the study at the outbreak of World War II because the environment changed so drastically in the 1940s and 1950s, culminating in the 1952 Revolution and the sequestration of all foreign-owned businesses in 1956. To have included this period in our study would have distorted the lens considerably, because the post-1939 years were so different to the preceding decades.

Returning to our research questions, it is clear that the OLI paradigm provides a clear explanation for the decision to expand operations from Greece into Egypt, especially given Ionian’s Anglo-Greek character and the links this provided with what was an extensive diaspora. Moreover, Egypt offered considerable opportunities to expand, while its Court of Directors was sufficiently confident of its connections with the Greek diaspora on which a reasonably viable business could be developed. At the same time, apart from struggling to match the financial resources of its rivals, Ionian clearly suffered from some severe principal-agent problems, in that both the branch management and agents frequently operated according to their own rules, rather than those laid down by the Court in London. These organisational challenges were further accentuated after 1920, when both the price of cotton fell drastically from its wartime highs (see ) and new competitors emerged in the form of Banque Misr and Barclays DCO. This was why Stavridi as chairman of the Court was obliged to work closely with the general manager in London and his equivalent in Alexandria to ensure that adequate profits were generated from the capital provided by his shareholders.

Building on the comprehensive analysis provided by Jones (Citation1993) especially, this case-study of Ionian Bank highlights the intrinsic value of conducting detailed case-studies that offer insights into the way multinational banks coped with a highly challenging market environment. The Bank’s experiences also reflect accurately how management coped with the principal-agent issues associated with operating a geographically dispersed organisation. This has extended our understanding of how banking evolved in a developing economy that was both increasingly integrated into the global economy and struggling to cope with a complex political environment. Moreover, one can also conclude that without the funds supplied by the plethora of foreign banks that by 1920s operated in Egypt, this would have been a much slower process, given the subsistence economy that had existed prior to the 1860s and deeply held religious constraints that restricted the emergence of indigenous banking. The intense competition that prevailed in Egypt for banking services and the reluctance of locals to deposit funds in these institutions also explains why, contrary to the claims of some academics (Ahmed, Citation1982; Haridi, Citation2002; Morsy, Citation1971; Rashad, Citation1927, pp. 199–200; Roshdy, Citation1972) and many local politicians, foreign banks were unable to extract substantial profits from Egypt. Although the lack of detailed archival material limits our ability to generalise further about this issue, it is clear from the Ionian case that banking in Egypt up 1940 was highly challenging, yet crucial to the local economy’s emergence from its subsistence roots.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Associate Editor, Professor Lucy Newton, for the diligent management of submission and three anonymous reviewers for their valuable suggestions. We would like to thank the participants at the Association of Business Historians conference (2023), the European Business History Association conference (2023), and the Economic History Society conference (2024) for their helpful comments. We would like to extend our gratitude to Anna Towlson and the staff of the LSE Library Archives and Special Collections, where the Ionian Bank’s archive is hosted; Dr Mike Anson and the staff of the Bank of England Archive; Karen Sampson of Lloyds Banking Group Archive; and the archivists at the British National Archives.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Akram Beniamin

Akram Beniamin is a Postdoctoral Researcher in Economic History at the Faculty of History, University of Oxford and Research Associate at the Centre for Economic Institutions and Business History at the University of Reading. He is interested in international business history in developing countries and financial history.

John F. Wilson

John F. Wilson is a Professor of Business History at Northumbria University. He has published extensively in the field of business history, including a dozen monographs, twenty edited books and over seventy articles and chapters covering topics such as strategy, international business, clusters and management education and training. He has also been co-editor of Business History (2004–2014), as well as President of the Association of Business Historians.

Neveen Abdelrehim