ABSTRACT

What are the motivations for internal migration, and how do social relations influence the migration process? In answering these questions, this paper focuses on internal migration to Accra, the capital of Ghana. Qualitative interviews were conducted with 20 migrants in different areas of the city and analysed using narrative analysis. We found that livelihood and lifestyle dimensions work in tandem as motivations for migration. While the main reasons for moving to Accra, according to the interviewees, are related to livelihood, they are reflected and performed in culturally bound lifestyles. Furthermore, while social relations are rarely the main motivator to migrate, the social networks of migrants constitute an important enabling (or disabling) factor in shaping both livelihood and lifestyle dimensions of the migration process. Finally, we found that different ties – including emotional and economic – have different meanings across the migrants’ social network throughout the migration process.

RÉSUMÉ

Quelles sont les motivations de la migration interne et comment les relations sociales influencent-elles le processus de migration ? Pour répondre à ces questions, le présent document se concentre sur les migrations internes à Accra, la capitale du Ghana. Des entretiens qualitatifs ont été conduits avec vingt migrants dans différents quartiers de la ville et examinés à l’aide de la méthode d’analyse narrative. Nous avons constaté que les dimensions liées aux moyens de subsistance et aux modes de vie vont de pair pour motiver la migration. Si, selon les personnes interrogées, les principales raisons de s’installer à Accra sont liées aux moyens de subsistance, elles se reflètent et se concrétisent dans des modes de vie liés à la culture. En outre, si les relations sociales sont rarement la motivation principale pour émigrer, les réseaux sociaux des migrants constituent un important facteur de facilitation (et d’invalidation) dans la détermination des dimensions du processus migratoire liées aux moyens de subsistance. Enfin, nous avons constaté que les différents liens – y compris émotionnels et économiques – ont des significations sociales différentes dans le réseau social des migrants tout au long du processus de migration.

Ekro do sua, yentena faako gye animguase.

There are many towns, do not stay long in a place and disgrace yourself.

(Akan proverb)

1. Introduction

A few weeks into the fieldwork, we are sitting in the car of an Uber driver from Ghana’s Volta region, who, despite holding a bachelor’s degree in marine engineering, has not been able to find a job in the field. When asked why he decided to stay in Accra, despite the difficulties, he exclaimed: “The cake is in Accra!” He explained that in Volta he would not have access to higher educationFootnote1 nor are there industries to employ him. Instead, he juggles short contracts at the harbour of Tema (the main port of Ghana, a few kilometres from Accra) with his job as an Uber driver. Despite working temporary, low-paying jobs and barely making ends meet, the allure of Accra being “where the cake is” makes it appealing and worthwhile to move and live in the capital city: besides the economic incentive of improving one’s education and livelihood, migrating is a response to a (dreamed and imagined) lifestyle that is only attainable in Accra. In this article, we refer to “the cake” – which is supposedly found in Accra – as a metaphor for the perceived improvement in post-migration life in the capital, in terms of both livelihood and lifestyle, as these two dimensions are what makes the destination appealing.

By interviewing 20 migrants in Accra, we learnt that the “cake” supposedly found in the capital is both an economic (livelihood) and a socio-cultural (lifestyle) objective for migrants. Furthermore, social relations are extremely important, as they determine the migrants’ ability to obtain a “slice” – for example, by facilitating accommodation upon arrival in Accra (e.g. by finding a room, initially paying for the rent or hosting the migrant), which was one of the main concerns of the interviewees in this study. In this paper, we explore the reasons for migrating to Accra, with a focus on the social relations that shape migrants’ journeys, livelihoods and lifestyles in the capital, in an attempt to answer the following research question: How do livelihood and lifestyle dimensions shape the process of migration to Accra, and how do social relations matter?

This research question positions us at the rather overlooked nexus between two bodies of literature: first, internal rather than international African mobility; second, a holistic focus on internal mobility in Ghana, as both a livelihood and a lifestyle strategy. The disproportionate focus in recent policy and academic debates on international mobility (Smith and Schapendonk Citation2018) seems to suggest that migration mostly happens from the Global South to the Global North (Schans et al. Citation2018). However, the great majority of African migrants move within their region (United Nations Citation2019) or country borders (Food and Agriculture Organization Citation2017). Urbanisation in Ghana has boomed in the past century, with the majority of the population now living in urban areas (Yankson and Owusu Citation2017). Yet rural-to-urban migration is only one of the factors contributing to urbanisation (other factors include population growth and a drop in the mortality rate). The majority of migration is actually not directed to urban centres but rather rural-to-rural (Beauchemin Citation2011; de Brauw, Mueller, and Lee Citation2014; Potts Citation2012).

This study contributes to the growing, yet limited, body of literature on internal mobility (Awumbila Citation2015; Egger and Litchfield Citation2019). Using qualitative research methods, we analyse the ways in which social relations matter in migrants’ journeys, as well as in their life at the destination (in this case, Accra). We focus on internal mobility in Ghana, a country that is both exceptional and typical of countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Ghana is one of Africa’s exceptional success stories in terms of economic growth. At the same time, it has undergone a process of structural adjustment, democratisation and decentralisation that is common to many countries on the continent (Diao et al. Citation2019). Ghana is typical for its “urbanization without industrialization,” which has resulted in insufficient employment despite its rapid economic growth – particularly in the cities (Diao et al. Citation2019, 144). Also, in terms of migration Ghana is a typical case study, as the majority of its migrants are internal (International Organization for Migration Citation2020; Skeldon Citation2018). According to the 2010 census (Awumbila Citation2015), 35% of the Ghanaian population were living away from their place of birth, and 90% of all migration was internal to its national borders. Furthermore, as the majority of migrants in Ghana are youth (defined as being between 15 and 35 years of ageFootnote2) (Ackah and Medvedev Citation2012; Langevang and Gough Citation2009), this research focused on this specific group of internal migrants.

The scholarly literature is to a great extent divided into studies focusing on migration as a livelihood strategy (Ackah and Medvedev Citation2012; Alhassan Citation2017; Marfaing Citation2014) and those that look at the socio-cultural or lifestyle dimensions of mobility (i.e. dimensions of mobility that are related to social norms, status or personal preferences) (Boesen, Marfaing, and de Bruijn Citation2014; de Bruijn, van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001; Langevang and Gough Citation2009; van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018). For instance, moving to Accra is referred to as an American dream that contributes to gaining social status. In this study we firstly examine how these two dimensions of mobility are intertwined in Accra, thereby reconciling the divided academic debate. Secondly, we focus on the role of migrants’ relationships in the process of moving to Accra and in migrants’ post-migration life, thereby showing how relationships matter as an enabling (or disabling) factor in the journey, as an “aspiration window,” and as economic or emotional ties that span Ghana and even extend abroad. We do so by applying qualitative research methods, specifically semi-structured interviews and narrative analysis. In the narrative analysis (through coding), we examine the types and strength of relationships between migrants and people in their social networks, by examining the ways they talk about their relationships with people in Accra and at home.

We find that seeking employment and better education are, for our informants, the main reasons for migrating. However, their post-migration lifestyle is strongly influenced by culture-bound visions of Accra as a migration destination, suggesting that the lifestyle in the capital is an additional motivation for migrating there. Thus, lifestyle and livelihood motivations go hand in hand. While this study found that relationships are rarely the main motivator to migrate, our analysis shows that the social networks of migrants constitute an important enabling (or disabling) factor in the process of moving to Accra. Therefore, it is not necessarily those with the strongest “push” or “pull” motivations who are moving to the capital, but rather those who have a social network that they can rely on and peers inspiring them to move.

This paper is structured into four main sections. Section 2 examines the divided focus of the migration literature on either the livelihood or the lifestyle dimension of mobility, as well as its main insights regarding the importance of social relations in migration processes. This is followed by a description of the research context in section 3, including the field sites, characteristics of the sample of informants taking into consideration data from the latest round of the Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS), and the qualitative methods of analysis used. In section 4, we set out the findings of the research by way of a narrative analysis of the livelihood and lifestyle dimensions of migration/post-migration life in Accra and of how relationships matter throughout the migration process. Finally, we conclude by discussing our results in light of our theoretical framework and provide some recommendations for further research.

2. Why and how people move: livelihood, lifestyle and social relations

In migration studies, the terms “mobility” and “migration” are often used interchangeably, and the criteria for defining the various types of mobility are seldom clear (Bruijn, van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001, 3–13). In this article we understand migration to be a type of spatial mobility, and we also use the terms mobility and migration interchangeably. Spatial mobility refers to a change in residence, for either a short or a long period of time, that involves the crossing of administrative or political borders (Bruijn, van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001, 3). As regards the process of migration to Accra, we refer to this as “internal mobility,” which is either a livelihood or a lifestyle strategy; and we call the people engaging in such mobility “internal migrants,” as they cross regional administrative borders. For this reason, our way of sampling informants is based, among other things, on the simple criterion of “change in residence” from regions outside of Greater Accra to the city of Accra.

Livelihood and lifestyle approaches

The relationship between the livelihood and lifestyle dimensions of migration has received relatively little attention (Bruijn, van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001; Ungruhe Citation2010; van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018), and in relation to internal migration this relationship is even more overlooked (Jarawura and Smith Citation2015; Thorsen Citation2006). Research focusing on livelihood strategies commonly understands mobility as a response to systemic economic, political and/or environmental “push” and “pull” factors (Ackah and Medvedev Citation2012; Alhassan Citation2017; Awumbila Citation2017; Bezu and Holden Citation2014; de Brauw, Mueller, and Lee Citation2014; Marfaing Citation2014).

Studies on the connection between internal migration and livelihood improvements have yielded mixed results. Ackah and Medvedev (Citation2012) found increased economic empowerment among migrant-sending households. This may be due to the fact that there is an important connection between urban migrants and rural sending communities in the form of the remittances that migrants send home (de Brauw, Mueller, and Lee Citation2014). Indeed, in their exploration of “translocal” connections, Steinbrink and Niedenführ (Citation2020) show how migrants’ networks, which span place of origin and destination, multiply opportunities. In contrast, from their study on the impact of migration on poverty reduction, Adjei, Serbeh, and Adjei (Citation2017) show that migration to rural areas can have a stronger effect on economic empowerment than migration to urban areas.

Migration studies that take a lifestyle perspective on migration are generally qualitative and focus on the social and cultural aspects of mobility, for instance migrants’ values, norms, social relations and practices (Boesen, Marfaing, and de Bruijn Citation2014; Bruijn, van Dijk, and Foeken Citation2001; Gladkova and Mazzucato Citation2017; Langevang and Gough Citation2009; van Geel and Mazzucato Citation2018; Wissink, Düvell, and Mazzucato Citation2020). When considering the different types of mobility in West Africa (e.g. cattle herding, nomadism, traders, healers, etc.), Boesen, Marfaing, and de Bruijn (Citation2014) refer to mobility as a “culture of travel,” “culture of migration” or “mobile way of life.” Rather than rational calculators of livelihood opportunities, lifestyle-focused studies understand migrants as agents responding to factors such as critical events (Jarawura and Smith Citation2015; Wissink, Düvell, and Mazzucato Citation2020), chance (Gladkova and Mazzucato Citation2017) and their social network (Awumbila Citation2017).

In line with the literature, we refer to “mobility as a livelihood strategy” for the migrant – temporary or permanent – as a way to generally improve their economic situation; it therefore includes motivating factors such as fleeing poverty or seeking employment, education opportunities or the potential for career growth. We refer to “mobility as a lifestyle strategy,” as a way to improve social status by moving to places that are perceived to be more progressive or “modern”; this type of mobility also includes cultures of mobility that respond to gender or family norms (e.g. wives following husbands, children following parents, nomadic lifestyles, living independently from the family). “Livelihood” and “lifestyle” are two dimensions of mobility that are usually intertwined and feed into each other: for instance, improving one’s financial well-being (“livelihood”) results in improvements in social status and the ability to partake in the coveted urban life (“lifestyle”). However, the connection and relationship between these two types of mobility, particularly for internal migrants, remains under-researched.

Despite the fact that the majority of the migrants in Ghana fall into the category of youth, the internal mobility of youth is relatively understudied. However, there are two important exceptions that point to the importance of lifestyle as an incentive for migration: Langevang and Gough (Citation2009) as well as Ungruhe (Citation2010) show the importance of mobility for youth in order to obtain social status and become “somebody.” Both of these studies show how the identity and social status of youth are shaped and negotiated in relation to their social network and peers.

How social relations matter

There is one missing dimension in the push-and-pull theory described above: the role of migrants’ social networks. On the one hand, social relations can also constitute a push or pull factor, e.g. when migrants are “pushed” by family members to move to the city in the hope of remittances flowing back to the place of origin, or when migrants are “pulled” to a different place to join another family member, e.g. their spouse. On the other hand, social relations may also facilitate migration processes. Social networks play an important role when it comes to access to material resources in the destination, such as information about jobs, accommodation, and access to credit and resources, as well as access to psychological and emotional resources (Mani and Riley Citation2019; Zaami Citation2020). Awumbila (Citation2017) stresses that social networks are an important form of social capital for those migrants who lack economic capital, confirming findings on the role of social capital in non-African migrants’ social networks (Sue, Riosmena, and LePree Citation2019).

The theory of “cumulative causation” states that “as migratory experience grows within a sending community, the likelihood that other community members will initiate a migratory trip increases” (Fussell Citation2010, 162). Mani and Riley (Citation2019) explain this cumulative causation by referring to an “aspiration window”: when one’s social network consists of (strong or weak) ties with migrants, particularly with people who are seen as role models, migration becomes a real option. Having migrant role models can lead to a desire to share their lifestyle by also migrating and, thus, living a capital lifestyle.

3. Studying internal migration to Accra: fieldwork and methods

The fieldwork for this study was conducted in Accra, the capital of Ghana. Ghana consists of 16 regions, with Ashanti and Greater Accra being the most populous. Greater Accra is by far the main migrant-receiving region: about 50% of its inhabitants were born somewhere else (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2019). The regions with the lowest proportions of incoming migrants are Upper East, Upper West, and the Northern region (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2019). The low migration rates into regions in the North of Ghana do not come as a surprise, as they reflect differences in “agroecological conditions, population density, rural infrastructure, and levels of urbanization” (Diao, Magalhaes, and Silver Citation2019, 144), making the North potentially less appealing for migrants. As Greater Accra attracts most individuals who move to an urban area, we focused on this region. Greater Accra is the most urbanised region of Ghana, with 90% of its population living in urban, as opposed to rural, areas (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2019). Within Greater Accra, the city of Accra is the main hub, with about 3.2 million inhabitants in 2019 (World Bank Citation2021).

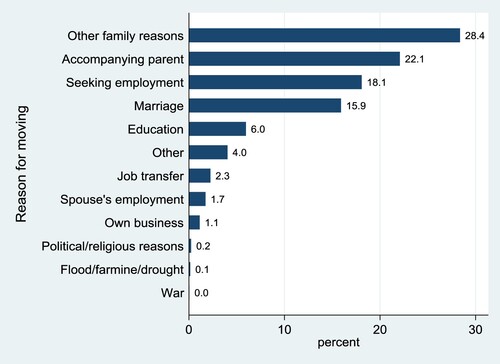

The majority (66%) of the migrant population in the capital are below 35 years of age, with the largest group being between 15 and 35 years of age – the age category defined in the Ghanaian constitution as “youth” (Ministry of Youth and Sports Citation2010). Among the migrants, there are nearly equal numbers of men and women. According to GLSS data (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2019), the first two motivations for migration are either “other family reasons” (28.4%), or “accompanying a parent” (22.1%). “Seeking employment” comes third, at 10 percentage points lower than the first motivation (see ). As the categories “other family reasons” and “accompanying a parent” are not very specific and could refer to a variety of motivations, it is difficult to make a general statement about the social versus economic motivations of migrants when considering the GLSS data. Furthermore, the GLSS does not include information on lifestyle as a potential motivation for moving to the capital region.

Figure 1. Main motivation for moving to the place of interview. Data from the Ghana Living Standards Survey (GLSS) (n = 2,129).

To better understand the process and motivations of internal migration to Accra, we carried out in-depth interviews with migrants in Accra. As shown in the following subsections, social, livelihood and lifestyle motivations appear to work in tandem. As the Greater Accra region attracts the most migrants, we conducted our field research there. We interviewed migrants who were born in Eastern, Volta and Central regions, as these are the regions where most migrants were living before coming to Greater Accra (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2019). Additionally, we interviewed migrants who were born in the Northern region, since the literature on internal migration in Ghana indicates this group of migrants is one of the most important (Alhassan Citation2017; Jarawura and Smith Citation2015; Zaami Citation2020).

Field sites

The fieldwork was carried out in six locations in Accra. Our aim was to capture diverse areas in Accra that are characterised by large influxes of internal migrants (Langevang and Gough Citation2009; Prempeh Citation2022). Thus, Adenta, Madina and Maamobi were selected as three major localities in Accra, where the majority of interviews (fourteen out of twenty) were conducted. Even though these three areas show large differences (one is a residential area, one is a trading hub, and the third is a slum), they are emblematic of the process of urbanisation in Accra. In addition, interviews were also conducted in Dome, Nungua and Tesano and on the campus of the University of Ghana. These localities were selected using snowball sampling to capture more perspectives in our sample. Here, we briefly describe the main localities.

Adenta is a municipality in the city of Accra, which is known as “the dormitory of Accra.” A largely residential area hosting almost 240,000 inhabitants, Adenta offers affordable housing for workers (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2021; Poku-Boansi and Adarkwa Citation2016). “The municipality has a very large economically active labour force” (Poku-Boansi and Adarkwa Citation2016, 783), mainly constituted by migrant settlers. We interviewed informants who were relatively highly educated (i.e. they had completed senior high school), and whose employment placed them in a low to middle socio-economic status.

Madina is a vibrant trading hub, with one of the biggest market areas in the Ghanaian capital. The majority of interviews were conducted around this market, a hectic and rich field site that reflects the heterogeneity of the population living and working in this area. Madina is home to almost 250,000 inhabitants (Ghana Statistical Service Citation2021), a heterogeneous population comprising a considerable (yet unquantified) number of migrants, particularly from the north of the country (Zaami Citation2020). Furthermore, its population has historically comprised a wide range of internal and international migrants: “Since its foundation in 1959, Madina has attracted migrants from all over Ghana and neighbouring countries” (Langevang and Gough Citation2009, 744). The informants we interviewed in this area were working (and some also living) in Madina and were all of low socio-economic status; most had a low level of education.

Maamobi is a maze of narrow streets, mostly pedestrian, that challenges the sense of orientation of any wanderer. It is a town in the Accra Metropolitan district, comprising mostly informal settlements, making the count of the population uncertain. According to Markwei and Appiah (Citation2016, 2), approximately 49,000 people (now most likely substantially more) were living in Maamobi, and “their living environment is characterized by poor drainage, inadequate housing, and haphazard development. Buildings include poor-quality material such as mud walls, zinc roofing sheets, and untreated timber.” Maamobi is principally a residential area, and is home to a community of mostly Muslim inhabitants. It has a vibrant informal economy, with “many different types of businesses operating from homes, in alleys, around and in the traditional market area, as well as in shops and stalls along the main road linking it with the surrounding neighbourhoods and the rest of Accra” (Yankson and Owusu Citation2017, 97).

Fieldwork

The fieldwork for this study was carried out in March 2020. A total of 20 semi-structured interviews were conducted, following an interview guideline comprising three main themes: (1) socio-demographics (details, occupation and background); (2) migration process, motivations and aspirations; and (3) social network before, during and after migration. In this way, we were able to examine how the migrant’s social network influenced their (understanding of the) migration process, and how this process varied depending on their identity (i.e. gender, origin, economic background). Considering that the majority of internal migrants in Ghana are youth (below 35 years), we sampled the adult population in this social group (18–35 yearsFootnote3) – with the exception of one woman aged 36. We accessed our interviewees through snowball sampling. In order to somewhat counteract the community bias that can go along with non-probability sampling methods, we made sure that our sample was diverse in terms of the migrant’s residence, as well as other socio-demographic characteristics. The verbal consent of respondents was obtained and interviewees were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw their consent at any point before, during or after the interview. Respondents were further informed that we might use statements from the interviews in an anonymised way for research purposes.Footnote4 summarises the main characteristics of our sample.Footnote5

Table 1. Main characteristics of the sample group.

While the majority of our informants spoke fluent English, an interpreter assisted us in carrying out the interviews in Twi and Hausa languages when necessary, as well as to find suitable informants and interpret puzzling circumstances during participant observations. Each semi-structured interview took about an hour, or slightly longer when the interpreter was intermediating.

Qualitative analysis

We analysed the 20 semi-structured interviews collected during the fieldwork in Accra, using narrative analysis and deconstructing the meanings attached to migrants’ narratives of their migration journey, post-migration lives and relationships. We used the program Atlas.ti (Version 8) to segment the interviews and attribute codes (Boeije Citation2009). These codes were not mutually exclusive and each segment of the interview could be assigned multiple codes. Subsequently, segments of data with the same attributed codes were categorised into groups of codes (see and the Appendix) (Fischer Citation2003).

Table 2. Definition of codes.

Considering that the study and the interview guidelines are targeted at understanding social relations, the process of coding highlights the nodes (members of the social network, e.g. mother, father, friends, spouse, etc.), ties (types of relations) and mobility process of the interviewees. In our analysis, we use the types of ties described below and consider nodes to be part of a social network that is not bound to a specific place (i.e. origin, destination, elsewhere) or time (present, past). The strength of the ties is measured by the number of instances in which a given tie is mentioned in relation to a given node (co-occurrence).

4. Results

Livelihood reasons: work and education

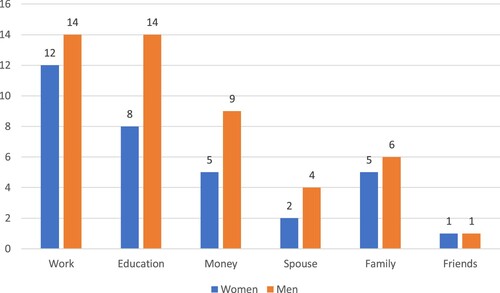

Seeking employment was the most important reason given for migrating by all groups of respondents, which is in line with the importance of “money” (namely, economic empowerment). Education was the second most important reason for all groups of interviewees. The general category “family” was considered relatively less important as a reason for migrating than “work” and “education,” and more specific relational categories like “spouse” and “friends” were rarely mentioned. These results (summarised in ), while not being representative of the wider migrant population in Accra, are in contrast to the results emerging from the GLSS, in which social relations seemed to constitute an important motivation for migrating. We can assume that the “family reasons” reported in the GLSS also included an economic dimension – for instance, to join a family business.

These findings show the importance of livelihood as a motivation for migrating, and can be best illustrated by referring to a specific example. An informant named Paul,Footnote6 an accountant from the Volta region, twice attempted to move to Accra before succeeding in his ambition: this example showcases migration motivated by education and work opportunities in Accra, which were first hindered then facilitated by his social relations. One of his brothers was already living in the capital, while another had moved to France. The brother in Accra discouraged him from coming, as he was not in a position to help him; however, Paul moved to Accra anyway and stayed with various high school friends, moving frequently and hustling to find a job that could earn him enough money to go to university. On his first attempt, Paul failed to find employment and returned to his parents’ house in his place of origin. The second time, his brother in Accra was able to host him and, together with the other brother in France, paid for his university fees. Paul’s account shows his motivation to move: obtaining a university degree in the capital. In contrast, his family (brother) was not a major motivation to migrate, but may have inspired Paul to move to the capital by opening up an “aspiration window.” This example illustrates how “cumulative causation” works: Paul’s brother was crucial in facilitating his settling in Accra (by offering hospitality in his home) in tandem with an aspiration window (the desire to complete his education), which provided the framework and motivation, but was only enabled, in the second attempt, by the support of both brothers. While Paul’s motivation to migrate was related to improving his education and livelihood, it was his relationships that first hindered and then enabled his migration plan.

When it comes to improving one’s livelihood, several of our female respondents mentioned that potential work opportunities differ by gender. One of our female interviewees explains that men are more likely to find jobs as motorcycle taxi drivers or cleaners, whereas women mostly sell goods, prepare meals or work as carriers. However, interviewees do not consider either gender more likely to find work – it is just the type of work activities that differs.

Lifestyle: big girls, big boys and social status

Beyond the reasons to migrate that we identified, which refer mostly to livelihood, in this subsection we show how the lifestyle associated with living in the capital matters.

Accra life

An Uber driver, Kofi,Footnote7 from the Eastern region of Ghana, insisted that he would not migrate elsewhere, nor return to his village, despite elaborating at length on the struggles that come with life in Accra:

When you’re broke and owe too many people, you know you’re in Accra.

Other than Accra, would you like to stay here or would you like to move somewhere? Would you like to go to another city, or return to your village? How do you feel?

Ooh, you know for Ghana, Accra is the “ish.”

Accra is the what?

Accra is the thing. Like, Accra …

The “ish” [everyone laughs].

Yeah. That’s the street language.

Accra-is-the-ish.

[Respondent laughs]. So, eerrm … as you are in Accra, it’s like America controlling the world. […] That is what I believe. That America controls the world. In a way, okay. That is what I have learnt. But in Ghana here, Accra is where everything happens.

Increasing one’s social status

Moving to Accra is associated with the possibility of increasing one’s social status by improving one’s livelihood, but also by being exposed to a more varied reality, compared to village life. Social status is associated with both the livelihood and lifestyle dimensions of mobility: on the one hand, the economic empowerment that derives from increased income and, on the other, the “American dream”-like imaginary associated with the capital city. Furthermore, social status is associated with fighting for one’s future and a better life, and success is something migrants show during visits to their place of origin for recognition. Evidence of success is borne in one’s clothes, hairstyle and even body weight: to say “you became fat” is, in this context, a synonym for success.

Simon,Footnote8 a 19-year-old respondent we met in Madina, came from Cape Coast to Accra and makes a living baking bread. He reflects on the impression that he makes on his mother and friends back in Cape Coast when he goes to visit:

Respondent: When I came to Accra, I wasn’t big. But when I go back to Cape Coast maybe my mother will say I have gained weight. Maybe if I come to Accra and I don’t live a better life, they will say that “when he went to Accra, he didn’t go and live any better life.” And when I go and live a better life too, they will say that “when he went to Accra, he went to live a good life. He didn’t go there to live a bad life, but he went to fight for his future.”

In the next subsections we discuss the important gender differences embodied in the improvement of social status: with a higher social status males become “big boys” or “big men,” while females become “big girls.”

Big boy

Marc refers to “big boys” (as “US boys”) and to the way in which big boys go about spending money, which he has not yet achieved. He says that he is still “chisel” (stingy), despite having changed “papa” (a lot). Marc cites the example of drinking water. He explains that if you are a “big boy” you will drink bottled water (more expensive), while he still drinks “sachet water” (less expensive drinking water packaged in little plastic bags). This example shows how livelihood and lifestyle not only are intertwined, but enable each other.

Besides having purchasing power, a “big boy” is also considered an independent man. Fabian,Footnote9 a respondent we spoke to in Adenta, considers himself a big man, as he lives in Accra where he works as an elementary school teacher. He explained that:

Respondent: … okay, you can be an adult. But you may not be a big man. When you say somebody is a big man, it’s like you have your own car, you have your house, you have a family, you have children. That one [person] they will regard as a big man. But you can still be an adult with family, but maybe without a house or a car [and not be a big man].

Respondent: You can be a big man with a lot of money, but still be stupid, you’re not an adult.

Big girl

Similar to a “big boy,” for women, becoming a “big girl” is associated with improvements in income and lifestyle, and the two reflect each other. During our interview with Claudia and her sister Laura,Footnote10, two sisters in Adenta, they engaged in a gendered discussion about the social status that comes with becoming a “big girl.” Claudia explains that girls are not allowed to plait their hair while they are in school, so she had been looking forward to completing her senior year of high school and coming to Accra, staying with her sister and plaiting her hair – which would make her a big girl. Claudia’s sister, Laura, explained:

Respondent: Big girl, as in you are not going to be called to, errm, “please do this, do that.” Right now you have your own and you can order yourself … you have your own choice to do it, whether you like it or not. You can decide oh today you will go out and hang out with friends and have a little chilling and then come back. […] When you are in school, they can command you to go and sweep, but if you are there and you are a big girl you can say “oh let me sweep and have rest.” Or I won’t sweep then have rest and go back and sweep.

Independence was also important for another respondent, Abigail,Footnote11 who was originally posted to Accra for National Service. She describes being:

Respondent: […] happy to live alone again. Because I have always been somebody who is reserved. I have always wanted to live alone, have my own something.

How relationships matter during migration and in post-migration experiences

As suggested in the cases of Claudia, Laura and Paul, and confirmed by most of our interviewees, relationships matter during the migration process, as well as in post-migration life in Accra. But how exactly do social relations matter, and (how) does this differ among respondents? In this subsection we analyse the relationships of migrants across time (before, during and post migration) and space (in Accra, their place of origin and abroad), in an attempt to understand the specificities for each group of interviewees.

Family members in the place of origin might have an interest in sending someone to the city, in the hope of economic advantages such as remittances. However, most of our respondents described feeling more emotionally connected to their social network in their place of origin than obliged to send remittances or give economic support. Family (as a whole) emerges as an important connection, both before and after migration to Accra, confirming the strong influence of family on cumulative causation and aspiration windows. Family connections are related to a feeling of belonging, which is both translocal and deeply embedded in the place of origin. Indeed, these connections can stretch across distant administrative boundaries and are usually still strong after more than five years of migration. This was the case for Claudia,Footnote12 a teacher from Kumasi whom we interviewed in Adenta in the backyard of her home, where she lives with her younger sister. When asked whether she feels close to her family members, she answered:

Respondent: We get very close when family meets. Because, recently, the very brother in France came; he came down and then got married. Yeah, and then my aunties came all the way from Kumasi and my parents came, we all met at his place, and then you could see the connection, like family coming together. Automatically we saw Kumasi in Accra. Yes, we felt that thing, yeah we felt that we’ve brought Kumasi here in Accra. We were still in Accra here. After all that, those who had to go to Kumasi went to Kumasi and those who were supposed to stay here, stayed. And the one who was supposed to go back to France, went back to France.

Respondent: […] the type of problem determines the type of person you go to.

From the narrative analysis of the interviews, we observed that the way in which men and women discuss the issue of accommodation upon arrival (often facilitated by family members) reveals an important gender dimension: while men see the lack of a housing tie as a potential threat, for women a lack of accommodation in Accra is considered a danger but also an inconvenience with regards to privacy:

Respondent: […] When I came, that [privacy] was a very big challenge for me. So what I use to do was, hang my panties on the dry line, then hang my dresses on the panties […]. I will hang the dresses on the panties and then I will feel ok. For the dress, if your eyes see it, I don’t care. But for my panties and my brassieres, no, no, no.

Respondent: The difference is you the woman, you can’t just get up and say you don’t know anyone but you will come here. But as for the man he can even sleep here or even someone’s … but as for the woman if you don’t take care someone can come and rape you. You see, someone can come and rape you. But as for the man it will take long for someone to even hurt him, or anyone who will try will struggle before he can hurt him. A woman’s strength is not like a man.

To summarise, the analysis of migrants’ relationships, as described in the interviews, has yielded three main insights regarding the importance of social relations in the migration process. The first is the importance of emotional ties to family and friends. Even if economic ties and ties involving remittances exist, the social network is particularly important when it comes to emotional support. Second, we found that generations matter in different ways along the migration process. While parents constitute an important relationship for migrants before migration, siblings and friends seem to be more strongly involved in post-migration life, compared to parents, grandparents, uncles and aunts. This is surely related to the proximity of peers in Accra, and indicates how relationships matter differently over time. As peers and role models for potential migrants, migrants not only inspire when it comes to the decision to migrate, but also help by facilitating the process, providing information and accommodation.

5. Discussion and conclusion

In this paper, we examined the lifestyle and livelihood dimensions of youth mobility to Accra using qualitative methods. Our results are particularly relevant as, despite the fact that internal migration is the most common and accessible form of migration in Ghana, knowledge about the motivation of migrants in Ghana is limited. Moreover, by accounting for livelihood and lifestyle reasons, we aim to go beyond simplistic explanations of migration as the mere result of push and pull factors.

This study found that livelihood and lifestyle dimensions are closely intertwined – in the migration process as well as in post-migration life. There is a shared imaginary of Accra as being an expensive destination, even potentially dangerous: “Accra is where the cake is.” “Accra life” is associated with an increase in social status that makes migrant males into “big boys” and migrant females into “big girls.” Such changes in social status are part of the common imaginary associated with life in the capital city, as well as being a status earned by attaining improved economic conditions. We show that while the main reasons for moving to Accra are related to livelihood strategies (work, education, money), they are reflected and performed in culturally bound lifestyles, which are showcased during visits to the place of origin. Our findings suggest that the push and pull factors described in academic debate on migration as a livelihood strategy are actually experienced and enabled in the frame of the urban lifestyle of migrants. It is their social networks that allow migrants to fulfil both their economic and socio-cultural aspirations. In other words, the “cake” is layered with both livelihood and lifestyle dimensions, which can be accessed through social networks.

Our analysis of livelihood and lifestyle is in line with the literature on aspiration windows (Mani and Riley Citation2019) and cumulative causation (Chen, Jin, and Yue Citation2010; Foltz, Guo, and Yao Citation2020; Fussell Citation2010) and shows how the social relations of migrants enable their migration process and shape their post-migration lives: relationships inspire the migration journey with promises of an improved livelihood and lifestyle, and facilitate the process with practical and emotional assistance. However, not all hopes and wishes come true: life in Accra is expensive, especially if the migrant wants to enjoy the city lifestyle, while secure and well-paid employment opportunities are rare. Moreover, being far from family and friends can lead to feelings of loneliness. When it comes to gender differences, we find that connections are described as even more crucial for women than for men – mainly because of security concerns, differences in physical strength and views on privacy. While we find that the type of work men and women engage in differs, the likelihood of finding a job seems to be similar across genders.

Our findings confirm that migrants experience and express both economic and socio-cultural ties through their relationships (Fussell Citation2010; Mani and Riley Citation2019; Zaami Citation2020). Our findings also show that emotional ties to family are strong and stretch beyond economic relations or the expectation of remittances. While emotional relations are strong for both family and friends, it is particularly peers (i.e. siblings and friends) who are important in the process of migration. Migrants express their agency through relationships (de Bruijn and van Dijk Citation2012; Williams Citation2006), while at the same time their ability to “access the cake” is shaped by their networks (Foltz, Guo, and Yao Citation2020; Mani and Riley Citation2019). Migrants’ social networks help in organising the migration process and allow migrants to integrate into post-migration life; through their relationships, migrants also serve as role models, representing the “Accra lifestyle” and (the promise of) an improved livelihood.

We have four main suggestions for further research. First, a larger sample of informants would allow an understanding of how socio-economic differences compare with gender differences, as we conducted only 20 interviews and followed a snowball sampling procedure. A larger sample would enable a more fine-grained analysis of how concerns about security, strength and privacy affect the life of female migrants in Accra. Second, it would be interesting to have a control group of non-migrants in the place of origin to understand whether their relational behaviour is different from the behaviour of those who move to Accra. It would also help us to better understand obstacles to migration. Third, further research could go beyond interviewing migrants alone and include people in the migrants’ social network to learn more about their motivations for facilitating the migration process, as well as analysing their influence on migration decisions in more depth. Finally, a longitudinal analysis of social networks would allow a deeper understanding of how the use of social networks by migrants evolves, whether ties to the place of origin become weaker over time, and whether migrants themselves “pull” other people from their origin to their current destination by serving as role models. It would also help us to understand whether migrants’ perceptions of lifestyle and livelihood change over time.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to all the respondents who devoted their time to this research by sharing their experiences and information during the interviews we conducted in Accra, Ghana. We also thank the research assistant Harriet Bosei-Oakye, who facilitated the translation of the interviews during fieldwork and who transcribed all the interviews. We are thankful to the reviewers and journal editors, who significantly contributed to improving this article with their thoughtful feedback. We also thank Susan Sellars for her help with editing and polishing the article in the last phase of review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maya Turolla

Maya Turolla is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Political Science, Centre for International Conflict Analysis and Management (CICAM), at Radboud University. She holds a double doctoral degree in political science from the Radboud University and the University of Bologna. She has a background in anthropology and development studies, and her research focus is on rural development, mobility and youth employment, in both Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. She has conducted research in Italy, France, Greece, Uganda, Rwanda and Ghana; her current postdoctoral research is on the Sahel region.

Lisa Hoffmann

Lisa Hoffmann is a research fellow at the GIGA Institute for African Affairs. In 2020, she was convenor of the Interdisciplinary Fellow Group “Sustainable Rural Transformation” at the Merian Institute for Advanced Studies in Africa (MIASA) in Accra, Ghana. Her research interests include peace and conflict studies, social cohesion and experimental economics. She has conducted research in Ghana, Kenya, Liberia, Sierra Leone, Tanzania and Togo.

Notes

1 At the time of fieldwork and up until March 2023, there was no faculty for marine engineering in the Volta region.

2 According to the Ghanaian Constitution, the social category of youth is defined as the age bracket between 15 and 35 (Ministry of Youth and Sports Citation2010).

3 Although the official definition of the social category of youth is 15–35, we did not include informants under the age of 18, for ethical reasons.

4 We conducted the interviews prior to the lockdown in Ghana due to COVID-19 (which began on 30 March) and stopped the data collection afterwards, as we did not want to put respondents, our research assistants or ourselves at risk.

5 More information is provided in Table A2 in the Appendix.

6 This interview was carried out in Tesano, Accra, on 10 March 2020 (note all references to names of interviewees are fictitious in order to protect the respondent’s identity).

7 This interview took place on the campus of the University of Ghana, Accra, on 5 March 2020.

8 This interview was carried out in Dome (at the house of the translator), Accra, on 20 March 2020.

9 This interview was carried out in Adenta, Accra, on 6 March 2020.

10 This interview was carried out on 6 March 2020 in Adenta, Accra.

11 This interview was carried out on 4 March 2020 in Nungua, Accra.

12 This interview was carried out on 6 March 2020 in Adenta, Accra.

13 This interview was carried out in Madina, Accra, on 11 March 2020.

14 The parents of this respondent are Ghanaian (father) and Nigerian (mother). The respondent was born in Nigeria and came to the Greater Accra region to stay with his father. Since he has Ghanaian nationality and moved within the Greater Accra region to live in Madina, he is an internal migrant.

References

- Ackah, C., and D. Medvedev. 2012. “Internal Migration in Ghana: Determinants and Welfare Impacts.” International Journal of Social Economics 39 (10): 764–784. doi:10.1108/03068291211253386.

- Adjei, P. O.-W., R. Serbeh, and J. O. Adjei. 2017. “Internal Migration, Poverty Reduction and Livelihood Sustainability: Differential Impact of Rural and Urban Destinations.” Global Social Welfare 4 (4): 167–177. doi:10.1007/s40609-017-0099-z.

- Alhassan, Y. 2017. Rural-Urban Migrants and Urban Employment in Ghana: A Case Study of Rural Migrants from Northern Region to Kumasi. Kristiansand: University of Adger. http://www.secheresse.info/spip.php?article73101.

- Awumbila, M. 2015. “Women Moving Within Borders: Gender and Internal Migration Dynamics in Ghana.” Ghana Journal of Geography 7 (2): 132–145. doi:10.4314/gjg.v7i2.

- Awumbila, M. 2017. Drivers of Migration and Urbanization in Africa: Key Trends and Issues. Background Paper. United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Sustainable Cities, Human Mobility and International Migration. https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/Drivers-of-Migration-and-Urbanization-in-Africa%3A-Awumbila/36d322465721e1ae7ae4c596e287fe4a2ad414a1.

- Beauchemin, C. 2011. “‘Rural–Urban Migration in West Africa: Towards a Reversal? Migration Trends and Economic Situation in Burkina Faso and Côte d’Ivoire’.” Population, Space and Place 17 (1): 47–72. doi:10.1002/psp.573.

- Bezu, S., and S. Holden. 2014. “Are Rural Youth in Ethiopia Abandoning Agriculture?” World Development 64 (December): 259–272. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2014.06.013.

- Boeije, H. 2009. Analysis in Qualitative Research. London: Sage.

- Boesen, E., L. Marfaing, and M. de Bruijn. 2014. “Nomadism and Mobility in the Sahara-Sahel: Introduction.” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue Canadienne Des Études Africaines 48 (1): 1–12.

- Bowan, L. 2013. “Polygamy and Patriarchy: An Intimate Look at Marriage in Ghana Through a Human Rights Lens.” Contemporary Journal of African Studies 1 (2): 45–64. doi:10.4314/contjas.v1i2.

- Brauw, A. d., V. Mueller, and H. L. Lee. 2014. “The Role of Rural–Urban Migration in the Structural Transformation of Sub-Saharan Africa.” World Development, Economic Transformation in Africa 63 (November): 33–42. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2013.10.013.

- Chen, Y., G. Z. Jin, and Y. Yue. 2010. “Peer Migration in China.” Cambridge, MA: National Bureau of Economic Research. doi:10.3386/w15671.

- de Bruijn, M., and R. van Dijk. 2012. “Introduction Connectivity and the Postglobal Moment: (Dis)Connections and Social Change in Africa.” In The Social Life of Connectivity in Africa, edited by M. d. Bruijn, and R. v. Dijk, 1–20. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US. doi:10.1057/9781137278029_1.

- de Bruijn, M., R. van Dijk, and D. Foeken. 2001. Mobile Africa: Changing Patterns of Movement in Africa and Beyond. African Dynamics 1. Leiden; Boston: Brill.

- Diao, X., P. Hazell, S. Kolavalli, and D. Resnick. 2019. Ghana’s Economic and Agricultural Transformation: Past Performance and Future Prospects. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/oso/9780198845348.001.0001.

- Diao, X., E. Magalhaes, and J. Silver. 2019. “Cities and Rural Transformation: A Spatial Analysis of Rural Livelihoods in Ghana.” World Development 121 (September): 141–157. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.05.001.

- Egger, E.-M., and J. Litchfield. 2019. “Following in Their Footsteps: An Analysis of the Impact of Successive Migration on Rural Household Welfare in Ghana.” IZA Journal of Development and Migration 9 (1): 1. doi:10.1186/s40176-018-0136-4.

- Fischer, F. 2003. Reframing Public Policy: Discursive Politics and Deliberative Practices. Oxford: Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/019924264X.001.0001.

- Foltz, J., Y. Guo, and Y. Yao. 2020. “Lineage Networks, Urban Migration and Income Inequality: Evidence from Rural China.” Journal of Comparative Economics 48 (2): 465–482. doi:10.1016/j.jce.2020.03.003.

- Food and Agriculture Organization. 2017. Evidence on Internal and International Migration Patterns in Selected African Countries. Knowledge Materials. https://www.fao.org/reduce-rural-poverty/resources/resources-detail/en/c/1062085/.

- Fussell, E. 2010. “The Cumulative Causation of International Migration in Latin America.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 630 (1): 162–177. doi:10.1177/0002716210368108.

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2019. Ghana Living Standards Survey Round 7 Main Report. https://www.statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/GLSS7%20MAIN%20REPORT_FINAL.pdf.

- Ghana Statistical Service. 2021. Ghana 2021 Population and Housing Census - General Report Volume 3A. Population of Regions and Districts. https://statsghana.gov.gh/gssmain/fileUpload/pressrelease/2021%20PHC%20General%20Report%20Vol%203A_Population%20of%20Regions%20and%20Districts_181121.pdf.

- Gladkova, N., and V. Mazzucato. 2017. “Theorising Chance: Capturing the Role of Ad Hoc Social Interactions in Migrants’ Trajectories.” Population, Space and Place 23 (2): e1988. doi:10.1002/psp.1988.

- International Organization for Migration. 2020. Migration in Ghana: A Country Profile 2019, December. https://publications.iom.int/books/migration-ghana-country-profile-2019.

- Jarawura, F. X., and L. Smith. 2015. “Finding the Right Path: Climate Change and Migration in Northern Ghana.” In Environmental Change, Adaptation and Migration: Bringing in the Region, edited by F. Hillmann, M. Pahl, B. Rafflenbeul, and H. Sterly, 245–266. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137538918_13.

- Langevang, T., and K. V. Gough. 2009. “Surviving Through Movement: The Mobility of Urban Youth in Ghana.” Social & Cultural Geography 10 (7): 741–756. doi:10.1080/14649360903205116.

- Mani, A., and E. Riley. 2019. Social Networks, Role Models, Peer Effects, and Aspirations. UNU-WIDER Working Paper 120. https://doi.org/10.35188/UNU-WIDER/2019/756-9.

- Marfaing, L. 2014. “Quelles Mobilités Pour Quelles Ressources?” Canadian Journal of African Studies / Revue canadienne des études africaines 48 (1): 41–57.

- Markwei, E., and D. Appiah. 2016. “The Impact of Social Media on Ghanaian Youth: A Case Study of the Nima and Maamobi Communities in Accra, Ghana.” The Journal of Research on Libraries and Young Adults 7 (2): 1–26.

- Ministry of Youth and Sports. 2010. National Youth Policy of Ghana. https://www.youthpolicy.org/national/Ghana_2010_National_Youth_Policy.pdf.

- Poku-Boansi, M., and K. K. Adarkwa. 2016. “Determinants of Residential Location in the Adenta Municipality, Ghana.” GeoJournal 81 (5): 779–791. doi:10.1007/s10708-015-9665-z.

- Potts, D. 2012. “Challenging the Myths of Urban Dynamics in Sub-Saharan Africa: The Evidence from Nigeria.” World Development 40 (7): 1382–1393. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2011.12.004.

- Prempeh, C. 2022. Nima-Maamobi in Ghana’s Postcolonial Development: Migration, Islam and Social Transformation. Bemenda: Langaa RPCIG. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2sp3d02.

- Schans, D., V. Mazzucato, B. Schoumaker, and M. L. Flahaux. 2018. “Changing Patterns of Ghanaian Migration.” In Migration Between Africa and Europe, edited by C. Beauchemin, 265–289. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-69569-3_10.

- Skeldon, R. 2018. International Migration, Internal Migration, Mobility and Urbanization: Towards More Integrated Approaches. No. 53, Migration Research Series. International Organization for Migration. https://publications.iom.int/books/mrs-no-53-international-migration-internal-migration-mobility-and-urbanization-towards-more.

- Smith, L., and J. Schapendonk. 2018. “Whose Agenda? Bottom up Positionalities of West African Migrants in the Framework of European Union Migration Management.” African Human Mobility Review 4: 1175–1204.

- Steinbrink, M., and H. Niedenführ. 2020. Africa on the Move: Migration, Translocal Livelihoods and Rural Development in Sub-Saharan Africa. Springer Geography. Cham: Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-22841-5.

- Sue, C. A., F. Riosmena, and J. LePree. 2019. “The Influence of Social Networks, Social Capital, and the Ethnic Community on the U.S. Destination Choices of Mexican Migrant Men.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45 (13): 2468–2488. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2018.1447364.

- Thorsen, D. 2006. “Child Migrants in Transit: Strategies to Assert New Identities in Rural Burkina Faso.” In Navigating Youth, Generating Adulthood: Social Becoming in an African Context, edited by C. Christensen, M. Utas, and H. Vigh, 88–116. Uppsala: Nordiska Afrikainstitutet.

- Ungruhe, C. 2010. “Symbols of Success: Youth, Peer Pressure and the Role of Adulthood among Juvenile Male Return Migrants in Ghana.” Childhood 17 (2): 259–271. doi:10.1177/0907568210365753.

- United Nations. 2019. International Migration 2019: Report.

- van Geel, J., and V. Mazzucato. 2018. “Conceptualising Youth Mobility Trajectories: Thinking Beyond Conventional Categories.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 44 (13): 2144–2162. doi:10.1080/1369183X.2017.1409107.

- Williams, L. 2006. “Social Networks of Refugees in the United Kingdom: Tradition, Tactics and New Community Spaces.” Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 32 (5): 865–879. doi:10.1080/13691830600704446.

- Wissink, M., F. Düvell, and V. Mazzucato. 2020. “The Evolution of Migration Trajectories of Sub-Saharan African Migrants in Turkey and Greece: The Role of Changing Social Networks and Critical Events.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 116 (November): 282–291. doi:10.1016/j.geoforum.2017.12.004.

- World Bank. 2021. “Population in Largest City - Ghana.” 2021. https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/EN.URB.LCTY?locations = GH.

- Yankson, P. W. K., and G. Owusu. 2017. “Chapter 7: Prospects and Challenges of Youth Entrepreneurship in Nima-Maamobi, a Low-Income Neighborhood of Accra.” In Young Entrepreneurs in Sub-Saharan Africa, edited by Gough, K. and Langevang, T., 32–47. New York: Routledge.

- Zaami, M. 2020. “Gendered Strategies among Northern Migrants in Ghana: The Role of Social Networks.” Ghana Journal of Geography 12 (2): 1–24. doi:10.4314/gjg.v12i2.1.

Appendix

Table A1. Code groups.

Table A2. Sample description.