The Cold War dominated global geopolitics in the latter half of the twentieth century. The uneasy toleration of ideological differences between the United States and the Soviet Union during the Second World War gave way to a bipolar world that learned to live under the threat of nuclear annihilation. Our understanding of how the superpowers used cartography to shape and support their ideologies and strategic operations is still evolving, with the first glimpses of the true extent of Soviet cartographic output only emerging in the early 1990s. The gradual unveiling of the USSR’s immense, diverse – and in all ways surprising – mapping portfolio has since completely rewritten our understanding of Soviet geospatial activity (see, for example, Watt, Citation2005; Davies, Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Cruickshank, Citation2007; Travers, Citation2008; Kent and Davies, Citation2013; Davies and Kent, Citation2017; Kent et al., Citation2019; Kent and Davies, Citation2019; Davis, Citation2021; Kent, Citation2021). From school atlases and tourist schemes to military topographic maps () and highly detailed city plans of foreign territories (), state mapmaking in the USSR was synonymous with building a Soviet utopia through the comprehensive reimagining of local, national and global space. Nevertheless, all maps that were publicly available in the USSR were subject to state control and falsification (Anon, Citation1970; Postnikov, Citation2001).

Figure 1. Extract from Soviet military 1:500,000 topographic map J-10-2 ‘Sacramento’ (private collection). Soviet topographic mapping covered the globe at several scales, including most continents at 1:200,000 or larger (Watt, Citation2005).

Figure 2. Extract from the central intersection of the four-sheet Soviet military 1:25,000 city plan of London (private collection), which was printed in Sverdlovsk (Ekaterinburg) in 1985. The plan identifies 374 strategic objects across the city that are classified, numbered and colour-coded according to their function, i.e. military-industrial objects (in black), administrative and governmental buildings (in purple), and military or communications facilities (in green). Notable examples in this extract include the Ministry of Defence (green, 246), the Houses of Parliament (purple, 249), and Waterloo and Liverpool Street railway stations (black, 21 and 24).

After the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, billions of map users have grown accustomed to the benefits of instant access to detailed mapping. A technological revolution in how geographical data are captured, presented and shared (especially with the removal of Selective Availability in the US Global Positioning System, the acceleration in the digitization of mapping technologies and national geospatial datasets, and the rise of Web map servers) has widened access to detailed, multi-scale mapping of virtually anywhere on the globe. Indeed, the ubiquitous presence of location-based services via handheld smartphones has, for many societies, implied access to a ‘totality’ of geographical knowledge, that, arguably, has constructed a sense of geospatial omniscience far beyond the imagination of citizens who lived on either side of the Iron Curtain over 30 years ago.

Nevertheless, technological progress has also desensitized today’s map users to the accumulated effort of cartographic production, especially for maps created before the digital era. From our modern perspective, when multiple corporate technology giants offer a range of global mapping solutions, it is easy to downplay the challenges and achievements associated with mapping diverse environments. Yet the compilation of analogue global datasets for multi-scale topographic mapping and the evolution of their extensive symbology, which together perhaps constitute the major achievements of Soviet cartography, still carry relevance in developing solutions for current and future global mapping initiatives. In addition, Soviet military city maps and plans, in particular, have gained an ‘afterlife’ as objects of historical and aesthetic value (see Rondelli et al., Citation2013 and Kent, Citation2021). This transformation was made possible once the maps’ intended function had become obsolete and the Cold War tensions that characterized the circumstances of their creation had dissolved, thereby creating a historically privileged perspective from which to appreciate their versatility.

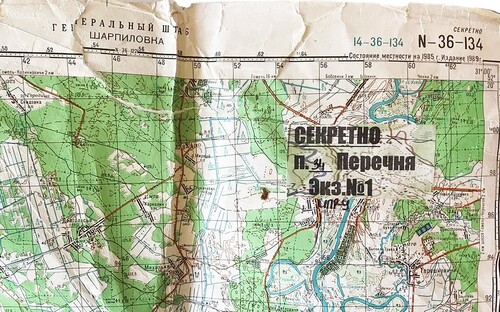

That privileged perspective was shattered on 24th February 2022. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which had a precursor in its annexation of Crimea in 2014, soon revealed Russia’s continued reliance on Soviet-era topographic mapping (); a mobilization that brought a terrifying reminder of the original purpose of these maps as instruments of conflict. Although Russia has supposedly undergone a geospatial transformation, characterized by its development of GLONASS, new satellite platforms for capturing reconnaissance imagery (e.g. Bars-M), and custom GIS software to provide a unified geospatial information space (Kent, Citation2022), the surprising deployment of Soviet topographic maps to the battlefield only serves to illustrate the gap that exists between the gathering of accurate and up-to-date geospatial intelligence and its supply and dissemination to commanders on the ground.

Figure 3. A 1989 edition of 1:100,000 Soviet military topographic map sheet N-36-134 ‘Sharpilovka’, which covers an area to the southeast of Belarus near the border with Ukraine. According to a BBC News journalist (Abdurasulov, Citation2022), this map marked ‘Secret’ was seized from a Russian commander and shows the plan of attack towards Kyiv.

Our original premise for compiling this Special Issue was to build on a growing body of scholarship to offer new insights into Soviet mapping, in its broadest sense, and to appraise the significance of its contribution to the development of cartography. One hundred years after the Soviet Union was established, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has unexpectedly reignited the relevance of Soviet mapping and has supplied a more urgent rationale for its study. It is therefore our aim here to provide a compilation of research that advances understanding of Soviet maps at this critical juncture and to stimulate the discovery of further insights into their origins, design and use.

New source materials have come to light since the end of the Cold War that have allowed a clearer picture of the organization, production and processes behind the Soviet military mapping project. John Cruickshank draws on the specification documents to chart the evolution of the topographic mapping initiative and its successive attempts to map the vast domestic territories of the USSR and beyond. Examinations of nationally specific circumstances reveal further insights into the production of these maps. Stig Roar Svenningsen and Mads Perner analyse the Soviet topographic mapping of Denmark, which they conclude as beginning from the early 1950s and was routinely updated until the end of the 1980s. Although there was greater reliance on satellite imagery, outdated local maps were still used with the result that some features and place names had been superseded by the time the maps were produced. Similar anachronisms are noted in Charles Aylmer’s observations on the Soviet mapping of China, which, include, for example, the depiction of tramlines on the 1987 Soviet military city plan of Beijing, even though the network had been abandoned by 1966.

Over 2,000 cities located in more than 130 countries outside the USSR are known to have been mapped in street-level detail by the Military Topographic Directorate of the Soviet General Staff. First revealed to the West at the International Cartographic Conference in Cologne in 1993, Soviet military city plans perhaps constitute the most startling cartographic discovery from the Cold War and are the focus of three papers in this Special Issue. Taking an analytical perspective of the plans’ symbology, Martin Davis and Alexander Kent examine original Soviet specification documents to evaluate their implementation and discover insights into how the challenges of mapping a global diversity of urban and natural environments were addressed. Focusing on the city plans of Copenhagen and Tel Aviv, Gad Schaffer and Stig Roar Svenningsen compare the quality and completeness of thematic information and evaluate its accuracy. This aspect is taken up by John Davies and David Watt in their critical examination of the non-cartographic content of city plans, namely the lists and classifications of ‘Important Objects’ on Soviet military plans of British cities.

Current Russian military mapping draws on a comprehensive cartographic symbology that was inherited from the Soviet era. In addition to the extensive range of topographic map symbols, this includes the depiction of military tactical operations and annotations in Russian that cover aspects such as unit and equipment type and strength as well as their manoeuvres and relationship to the surrounding environment, and other activities or conditions. Chuck Bartles provides an overview of these little-known practical elements of Soviet and Russian military mapping that carry especial relevance today.

Although the range of topics incorporated here includes a leaning towards military mapping, this Special Issue also brings important new insights into educational and tourist cartography. Sofia Gavrilova’s investigation into the role of maps and atlases in the first decades of the Soviet state indicates how a renewed focus on geography placed maps at the centre of the school curriculum and in adult education schemes. As Sofia explains, this acknowledgment of the power of spatial knowledge and its relevance at local, national and global scales engineered the imagination and perception of Soviet space. Similarly, Ian Byrne’s analysis of Soviet tourist cartography highlights the role of maps in nurturing a love of homeland that combined activities of hunting and fishing with access to monuments commemorating the Great Patriotic War (1941–1945). These two papers offer valuable discussions of how these different genres of mapping served the interests of the state through their penetration into the lives and activities of Soviet citizens.

Wars start and end with maps. The changing relevance of the immense cartographic output of the Soviet Union demonstrates how maps can serve different purposes at different times; their value can be derived from the usefulness of their knowledge as much as from their life-affirming aesthetic. Although we have exchanged the relative geopolitical stability of the Cold War for a more volatile multi-polar world, we cannot appear to escape the legacy of its mapping. The use of Soviet maps to serve the geostrategic interests of the Russian state has shown how some cartographies – and therefore ideologies – of the past can still have agency in shaping the future.

The production of Volume 59 has continued to be affected by the impact of COVID-19 and the Journal’s editorial staff have been dedicated to ensuring that we return to schedule as quickly as possible. Despite these challenging circumstances, the quantity and scope of submissions remain high and the quality of research continues to reflect the best international scholarship in the field. I am keen to thank all those who have contributed to maintaining these standards in 2022; our many reviewers who contribute their time and expertise so generously; our Associate Editors, James Cheshire and Peter Vujakovic; our Editorial Assistant Martin Davis; and Liz and Meg Bourne, for their help with proofreading. The team at Taylor & Francis, particularly Sandy Dalgleish, Clare Midgley and Tricia Pantos, also deserve our thanks for their commitment to ensuring the return to schedule as soon as possible.

As readers will be aware, this final instalment of the year usually includes the British Cartographic Society’s Annual Report. However, with the alignment of Society’s financial year to its membership year (January to December), the BCS Annual Report will now move to Issue 2 (May) going forward. For Volume 60, it will therefore accompany the UK’s National Report to the General Assembly of the International Cartographic Association (ICA), which will be presented at the International Cartographic Conference in Cape Town in August 2023.

Notes on the cover

The cover of this Special Issue includes an extract from the Soviet military 1:25,000 city plan of London, which was printed in Sverdlovsk (Ekaterinberg) in 1985. More details are provided in the caption of in this editorial.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Alexander J. Kent

Alexander J. Kent is Honorary Reader in Cartography and Geographic Information Science at Canterbury Christ Church University in the UK. His research explores the relationship between maps and society, particularly the intercultural aspects of topographic map design and the aesthetics of cartography. He is also Chair of the International Cartographic Association (ICA) Commission on Topographic Mapping and formerly President of the British Cartographic Society.

John Davies

John Davies is a British map collector and enthusiast. He first encountered Soviet mapping whilst working in Latvia in the early 2000s, and since retiring from a career in Information Systems, has been writing and lecturing on the subject. Formerly editor of Sheetlines, the journal of The Charles Close Society for the Study of Ordnance Survey Maps, he lives in London and runs the website http://redatlasbook.com/.

Martin Davis

Martin Davis is Digital Map Curator at the Bodleian Library, University of Oxford. Martin completed his PhD in Geography at Canterbury Christ Church University in 2018. He has been Editorial Assistant and Book Reviews Editor of The Cartographic Journal since 2014 and was appointed Executive Secretary of the International Cartographic Association (ICA) Commission on Topographic Mapping in 2019.

References

- Abdurasulov, A. (2022) “Ukraine War: How Russia Took the South — and Then Got Stuck” BBC News (27th February) Available at: https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-europe-64718740 (Accessed: 20th June 2022).

- Anon. (1970) “Soviet Cartographic Falsification” The Military Engineer 62 (410) pp.389–391.

- Cruickshank, J.L. (2007) “German-Soviet Friendship and the Warsaw Pact Mapping of Britain and Western Europe” Sheetlines 79 pp.23–43.

- Davies, J. (2005a) “Uncle Joe Knew Where You Lived: The Story of Soviet Mapping of Britain (Part I)” Sheetlines 72 pp.26–38.

- Davies, J. (2005b) “Uncle Joe Knew Where You Lived: The Story of Soviet Mapping of Britain (Part II)” Sheetlines 73 pp.1–15.

- Davies, J. and Kent, A.J. (2017) The Red Atlas: How the Soviet Union Secretly Mapped the World Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Davis, M. (2021) A Cartographic Analysis of Soviet Military City Plans (Springer Theses Series) Cham, Switzerland: Springer.

- Kent, A.J. (2021) “The Soviet Military 1:10,000 City Plan of Dover, UK (1974)” International Journal of Cartography 7 (2) pp.245–251 DOI: 10.1080/23729333.2021.1910185.

- Kent, A.J. (2022) “Mapping the Globe, and the Revolution in Russia’s Geospatial Capability” In Monaghan, A. (Ed.) Russian Grand Strategy in the Era of Global Power Competition Manchester: University of Manchester Press, pp.26–48.

- Kent, A.J. and Davies, J. (2013) “Hot Geospatial Intelligence from a Cold War: The Soviet Military Mapping of Towns and Cities” Cartography and Geographic Information Science 40 (3) pp.248–253 DOI: 10.1080/15230406.2013.799734.

- Kent, A.J., Davis, M. and Davies, J. (2019) “The Soviet Mapping of Poland – A Brief Overview” Miscellanea Geographica 23 (1) pp.5–15 DOI: 10.2478/mgrsd-2018-0034.

- Postnikov, A.V. (2001) “Maps for Ordinary Consumers versus Maps for the Military: Double Standards of Map Accuracy in Soviet Cartography, 1917–1991” Cartography and Geographic Information Science 29 (3) pp.243–260.

- Rondelli, B., Stride, S. and García-Granero, J.J. (2013) “Soviet Military Maps and Archaeological Survey in the Samarkand Region” Journal of Cultural Heritage 14 (3) pp.270–276.

- Travers, D. (2008) “Soviet Military Mapping of Ireland During the Cold War: Galway and the Western Littoral” Journal of the Galway Archaeological and Historical Society 60 pp.178–193.

- Watt, D. (2005) “Soviet Military Mapping” Sheetlines 74 pp.1–4.