Abstract

Nature-based learning emphasizes experiential learning, as children actively engage with their surroundings, observe and investigate natural phenomena, and make connections between their experiences and academic concepts.

Nature-based learning has been in use, both formally and informally, for over a century. Although many neurodivergent students have benefited from nature-based learning, most research to date has focused on the experiences of neurotypical (or general population) students. Thus, the use of nature to support autistic students has been constrained by the lack of evidence-based guidelines.Footnote1 Consequently, some autistic students are not being adequately supported while learning outside.

Limited research is available that has considered why some autistic people flourish in nature (and, similarly, why some autistic people find nature to be uncomfortable and distressing). In the absence of robust research, anecdotal accounts provide valuable insights. Naoki Higashida, in his bestselling book The Reason I Jump, beautifully described how he and many other autistic people feel when in nature:

Just by looking at nature, I feel as if I’m being swallowed up into it, and in that moment I get the sensation that my body’s now a speck, a speck from long before I was born, a speck that is melting into nature herself. This sensation is so amazing that I forget that I’m a human being, and one with special needs to boot. Nature calms me down when I’m furious, and laughs with me when I’m happy.Footnote2

For many autistic people, nature is a salient interest. Dara McAnulty, a teenage environmental activist and author of Diary of a Young Naturalist, shared his passion for nature in newspaper articles and on television programs. Perhaps the most well-known example of an autistic person who has gained fame for nature-related interests is Greta Thunberg, who initiated Fridays for Future, a weekly climate strike aimed at encouraging school-age children to get involved in climate action.

Research could help elucidate why experiences in nature, and particularly nature-based learning, may be beneficial for autistic people, and help us harness the positive aspects of these experiences to support well-being. Insights from autistic people themselves would be particularly informative. Given the need for evidence-based practice, further research on this topic could help formalize nature-based learning as a means of support or an alternative provision offered to autistic children at school.

▪ Nature-Based Learning can take many different forms in a range of spaces, from woodlands to gardens and urban parks to school grounds.

▪ Forest School

Forest School is one type of nature-based learning that follows a child-centered, holistic ethos. According to the Forest School Association, Forest School programs should meet six criteria (adapted from www.forestschoolassociation.org):

Occurs regularly over a long period of time

Takes place in a woodland or forest environment

Uses learner-centered processes

Promotes holistic development

Embraces taking supported risks

Is led by a qualified practitioner.

Existing Research on Nature-Based Learning and Autism

While limited, the research that does exist provides useful evidence to support the need for increased access to nature-based learning. In one case study,Footnote3 autistic children at a mainstream school engaged in nature-based learning with their two special education teachers who had no previous experience taking children outside. The children seemed to have positive experiences learning outdoors, evidenced by their ongoing desire to go outside for their lessons and their progress toward achieving their individualized education plan goals. The teachers also expressed their enjoyment of nature-based learning, saying that they felt more relaxed during and after teaching outside.

In a studyFootnote4 that used a more strengths-based framing and incorporated child voices, four autistic children, their parents, and two of their teachers were interviewed about the children’s experiences at Forest School. The perceived benefits of the children’s experiences included friendship development, experiencing success, and risk-taking. In other research, a case study of 25 autistic studentsFootnote5 participating in Forest School at their specialist school (which served only autistic students) harnessed parent and child voices, alongside participant observation. The researchers determined that Forest School appeared to have benefits for the well-being of some children, although not all the time. These benefits seemed related to the freedom and novelty of the outdoor environment and the opportunity to develop a range of skills; however, they were contingent on how the child felt on any given day, how well routines and procedures were upheld, and the attitudes of the adults present.

Facilitating Nature-Based Learning With Autistic Students

Teachers who regularly engage in nature-based learning sessions may feel very comfortable designing and leading outdoor sessions, but may not have much knowledge about autism or how best to support autistic students. Similarly, teachers who often work with autistic students may be well-versed in creating accessible spaces that are supportive of autistic students’ interests and needs; however, these teachers may find the idea of taking their students outside to be daunting. The advice that follows ideally will be relevant to both types of teachers.

To build effective nature-based learning sessions for autistic students, four main domains should be considered: safety, structure and routine, trust, and responsiveness.

Safety

Safety is fundamental to every outdoor experience. If students and teachers do not feel safe, learning or enjoyment is less likely to occur. The first step in creating a safe space is to consider the physical environment. Before commencing nature-based learning sessions, teachers should conduct a risk assessment and also get to know the space well so they feel comfortable there. Teachers should check the site prior to each session so they can inform students of what might have changed. For instance, recent rainfall might make certain areas of the site much muddier or turn a large puddle into a small pond. These are safety considerations and also can help students make choices about what they would like to do during their nature-based learning session.

▪ Risk versus hazard?

Risks and hazards are frequently referenced in nature-based learning, but what exactly are they? Put simply, a hazard is something that has the potential to cause harm while a risk is the likelihood that harm will occur. Engaging in properly assessed risk-taking is a key part of nature-based learning, especially Forest School.

When conducting a site and/or risk assessment of an outdoor space, consider the following:

What features of the physical space could be hazardous? For instance, are there any ponds or especially muddy portions of the site? Could tree branches fall after heavy winds? Carefully consider the various parts of the environment that need to be monitored — and consider the benefits of these various features, too. For instance, while having many trees on the site may mean you need to consider wind damage more often, it also means that students have more choice for tree climbing or den building.

What living things (plants and animals) are hazardous? Learning about the creatures that live on the site can be an excellent way to develop a deeper connection to the space.

What tools do you plan to bring to the site? How will you train students to use these tools safely?

What protocols are in place if something goes wrong? Do you have a way of getting in contact with the school or other adults for help?

In addition to conducting the initial site assessment and ongoing risk assessments, teachers should consider how they can help other adults feel comfortable in the outdoor space. Neurotypical adults often feel out of their comfort zones when facilitating or attending nature-based learning sessions and so may be likely to push back or complain. It is important to help them feel comfortable and safe in the outdoor space.

Finally, ensuring children are fed, warm, and comfortable before starting the session will make for a more enjoyable experience for all. Consider whether children have access to appropriate outdoor gear at home, and arrange for such resources if necessary. Similarly, students, especially autistic students who sometimes have sensory difficulties that make eating enough more challenging, may not come to school having eaten already. Asking a student to try new activities and engage in nature-based learning (and, indeed, any learning) when they are hungry or cold can be futile.

▪ Resources to make the outdoors more accessible

By providing the necessary resources and materials to enable students to safely engage with the outdoors, teachers can make nature-based learning even more accessible. Consider having the following materials ready for use (or, in some cases, encouraging students to bring them):

Waterproof jackets and trousers

Rain boots

Gloves, hats, and scarves

Sunglasses

Extra socks

Spare clothing if returning to class afterwards

Cushions for sitting on hard surfaces/the ground.

Structure and Routine

One of the most compelling reasons that teachers choose to engage their students with nature-based learning is the opportunity it offers to embrace students’ interests and balance out the power dynamics that are common in a classroom setting. While this autonomy is certainly beneficial, especially for autistic students who are often given less autonomy, it must be balanced with the need for structure and routine.

Many experienced teachers follow the same routine for every session they facilitate. An example routine could be the following:

The students change into their outdoor gear, meet the teachers by the door, walk together to the outdoor site, and wait outside the site’s gate until the teachers give them permission to enter. Then, the children gather around one of the meeting spaces. They are encouraged to sit on a log of choice around the fire circle for that day, but are allowed to stand or be elsewhere in the circle as long as they are listening to others. During this time, the teacher might ask if anyone notices any changes to the site that have occurred because of weather, share options for activities they might engage in that day, or ask the children what they are most looking forward to that session. After the opening circle time, the teacher tells the students that they are free to choose what they would like to do during the session. Depending on the site and the context, students might engage in den building, imaginative play using natural materials, tree climbing, tool use, or nature-based art.Footnote6 The session ends with the teacher making a bird call, which the students know is their signal to come back to the fire circle. The group again gathers around and talks about their favorite part of that day’s session. Once everyone has shared, they go back to school.

By adhering to the same structure for each session, students know what to expect – even if the bulk of the session involves free choice. For many students, consistent routines, boundaries, and expectations make the experience more accessible; this is particularly helpful for autistic students, many of whom prefer predictability.

It is important to ensure that children are told the reasoning behind the boundaries and expectations. For instance, if an expectation is that students avoid running while near tools or fire, explain to them that this is for safety reasons. A student who is running might trip over uneven ground or a stick that they don’t see. If they are too close to the fire or to someone using tools, they and others could get hurt. Providing explanations and reasoning helps children make more autonomous decisions and contributes to trusting relationships between teachers and children.

Students need to own their routines, and there can be multiple individualized routines and structures during any session. Structures and routines serve a function, but teachers easily can become overly rigid with the routine. Teachers also should be careful to give students advance notice when a routine will be changing. Changes are often unavoidable in natural settings, and letting autistic students know ahead of time if a certain activity or space will be unavailable can contribute greatly to the session’s success.

Trust

Trust can be built through interactions with students, through allowing students’ interest-led play and activity, and through consistency in each session. The previous advice about balancing autonomy with structure and routine comes into play here. Clear expectations and boundaries mean that the students know what to expect from the adults and from the session every time, which builds trust and helps children to feel safer in the outdoor area. Sara KnightFootnote7 described a “triangle of trust” — between the students, the teachers, and the physical space. The relationships between these three must be carefully fostered, with particular attention given to them in the first few sessions. For some autistic students, the development of these relationships might go at a slower pace, and teachers should follow the students’ lead.

The triangle of trust also necessitates that the teacher has a strong relationship with the physical space. This directly connects to our previous suggestions about safety; teachers who are aware of any changes that may present a hazard will be able to prevent injury or difficulty. This will build trust. Being well-informed about various features of the physical space will also support a trusting relationship.

Another way to build trust is to use first names when outdoors. This helps reduce the feeling of being in a hierarchy, which is often reinforced by norms in traditional educational settings. It signals to students that everyone is equal outside. Choosing a “nature name” can be a fun way of getting children used to calling their teachers by their first names while outside. For instance, Sonia’s “nature name” might be Sonia Sunshine and Jessica’s might be Jessica Rain. Using creative names illustrates that the outdoor space has different norms than the indoor classroom. The flatter power dynamic that is inherent in a child-centered approach like Forest School is often easier for autistic students to accept compared to typical hierarchies, which may seem arbitrary.

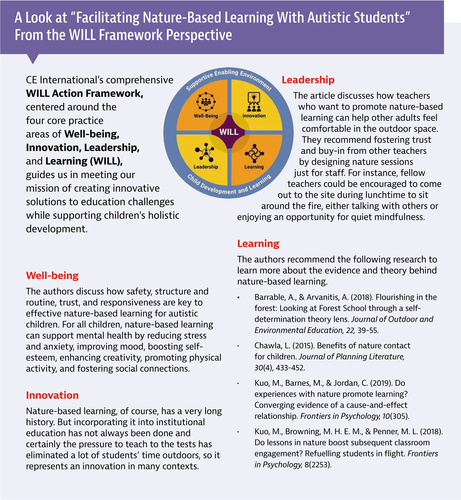

There is also a need to foster trust and buy-in from other teachers who may be attending nature-based learning sessions along with their students. It may be more difficult to gain the enthusiasm of teachers who do not enjoy the outdoors. Designing nature sessions just for staff could help. For instance, teachers could be encouraged to come out to the site during lunchtime to sit around the fire, either talking with others or enjoying an opportunity for quiet mindfulness. This allows the teachers to develop their own connection to the physical space and their own reasoning for spending time outside. Others may enjoy being outdoors, but they might not understand the educational or developmental benefits of these sessions. These teachers may appreciate learning the theoretical underpinnings of nature-based learning.

▪ Research to support taking students outside

To learn more about the evidence and theory behind nature-based learning, consider reading these articles:

Barrable, A., & Arvanitis, A. (2018). Flourishing in the forest: Looking at Forest School through a self-determination theory lens. Journal of Outdoor and Environmental Education, 22, 39-55.

Chawla, L. (2015). Benefits of nature contact for children. Journal of Planning Literature, 30(4), 433-452.

Kuo, M., Barnes, M., & Jordan, C. (2019). Do experiences with nature promote learning? Converging evidence of a cause-and-effect relationship. Frontiers in Psychology, 10(305).

Kuo, M., Browning, M. H. E. M., & Penner, M. L. (2018). Do lessons in nature boost subsequent classroom engagement? Refuelling students in flight. Frontiers in Psychology, 8(2253).

Responsiveness

A responsive teacher seeks to understand and work with each individual student. Nature-based learning will not work for everyone, so it is important not to romanticize nature and assume it will be an effective support for all autistic students. Some people will not find the outdoors to be a comfortable or enjoyable place to visit, regardless of how effective or encouraging a teacher might be.

Another way that teachers can be responsive to student needs and interests is by allowing the students to provide input regarding routines and boundaries. For instance, the first time that a group of students is taken to an outdoor site, the teacher and children can walk around the site to identify potential hazards and risks. Then, the teacher and students can discuss reasonable boundaries based on what they observed. By including children in these decisions and discussing the reasoning behind them, they are more likely to feel empowered and autonomous in adhering to the boundaries.

Similarly, students can be involved in risk assessments around outdoor sites. For instance, rather than discouraging a student who seeks out trees to climb when they are upset, a teacher could work with the child to determine which trees are strong enough to hold the child’s body weight. By including the child in this decision making, teachers build trust while helping identify a safe space to retreat when the child needs it. Conducting these risk assessments can provide the teacher valuable insight into a student’s strengths, fears, and interests.

Nature-based learning also provides ample opportunity for teachers to learn about and from their students. When teachers allow for autonomy and freedom within outdoor settings, staff may observe students behaving differently and attuning to their own needs in new ways. For instance, if a student opts to sit alone to calm down from an overstimulating or upsetting situation, the teacher learns that this is an effective coping mechanism for the student. These student-led strategies then can be encouraged in the indoor setting as well. A different setting also allows for unprecedented opportunities for the teachers to get to know each child individually. It is an excellent opportunity to learn what the child looks like when they’re uncomfortable, happy, self-soothing, or any number of other emotions and states.

Conclusion

These four pieces of advice are interconnected. For instance, establishing routines helps to build trust as students learn that they can expect to follow the same procedures during each session. Routines also help to enforce safety-promoting procedures. When students feel safe, it will be easier for them to trust those around them and their physical environment. Routines also leave space for teachers to be responsive to a student’s needs; as teachers and students learn more about each other, they can adjust the routines in response to interests, needs, and strengths. This will help to develop trust, too. Responsive teachers can include children in developing safety-promoting routines. By following these four suggestions — remembering safety, establishing structure and routine, building trust, and being responsive — teachers can facilitate supportive and welcoming nature-based learning for their autistic students.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Samantha Friedman

Dr. Samantha Friedman is a Lecturer in Education at Northumbria University in the United Kingdom. Samantha is a qualified Forest School leader and is interested in the intersection of nature, autism and neurodiversity, and well-being, particularly at school.

Michael James

Michael James is the author of Forest School and Autism. He is an expert Forest School practitioner in the United Kingdom, delivering sessions for autistic people of all ages.

Jessica Brocklebank

Jessica Brocklebank is the owner and lead practitioner of an independent Forest School in the United Kingdom, which offers sessions to children of all ages and is a specialist provision for local schools. Jessica has worked extensively with autistic students in specialist school settings.

Sonia Cox

Sonia Cox is a qualified Forest School assistant and a former teacher of autistic students in both mainstream and specialist settings in the United Kingdom. Sonia works in both school-based and independent Forest School settings and is undergoing her Level 3 Forest School Leader training.

Scott Morrison

Dr. Scott Morrison is an Associate Professor of Education at Elon University in the United States. His research focuses on ecologically minded teaching, everyday environmental education, and the uses of Twitter and Instagram in teacher education.

Notes

1 Throughout this article, we use identity-first language. While language preferences vary, recent empirical research has suggested that many members of the autism community prefer identity-first language: Bottema-Beutel, K., Kapp, S. K., Lester, J. N., Sasson, N. J., & Hand, B. N. (2021). Avoiding ableist language: Suggestions for autism researchers. Autism in Adulthood, 3(1), 18-29.

2 Higashida, N. (2013). The reason I jump (D. Mitchell & K. A. Yoshida, Trans.). Knopf Canada. p. 124.

3 Friedman, S., & Morrison, S. A. (2021). “I just want to stay out there all day”: A case study of two special educators and five autistic children learning outside at school. Frontiers in Education, 6.

4 Bradley, K., & Male, D. (2017). “Forest School is muddy and I like it”: Perspectives of young children with autism spectrum disorders, their parents and educational professionals. Educational and Child Psychology, 34, 80-96.

5 Friedman, S., Gibson, J., Jones, C., & Hughes, C. (2022). “A new adventure”: A case study of autistic children at Forest School. Journal of Adventure Education and Outdoor Learning.

6 See Friedman & Morrison (2021) for examples of nature-based learning with autistic students led by teachers with no Forest School training or experience teaching outside.

7 Knight, S. (2011). Forest School for all. SAGE Publications.