?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Do women exhibit a different pattern of entrepreneurial behavior as compared to men in post-Communist societies? This paper addresses this question using survey data from 25 Eastern Europe and Central Asian states. The sample consists of 11,617 private firms. As a result of 11,000 observations and multiple robustness checks, we find that female owners are more likely to introduce new marketing strategies than males. We demonstrate that firm innovation increases among top female managers with the increase in democratization. Democratization eliminates the gender disadvantages in firm innovation for most types of firm innovation.

HIGHLIGHTS

For most definitions, female leaders perform equally to males in firm innovation.

Female owners have a slightly higher tendency to introduce new marketing strategies than males.

Female top managers are less likely to invest in Research and Development as compared to male managers.

Firm innovation increases among top female managers with the increase in democratization.

Democratization eliminates the gender disadvantages in firm innovation for most types of innovation.

Introduction

This paper seeks to understand the relationship between female leadership and firm innovation using survey data from 25 transitional economies of Eastern Europe and Central Asia. The sample consists of 11,617 private firms, which participated in the Business Environment and Enterprise Performance Survey (BEEPS) conducted by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) in partnership with the World Bank in 2012, over twenty years after the beginning of Post-Communist regime transition and after the Great Recession of 2009. Furthermore, in 2012, the BEEPS extended the number of innovation questions in the questionnaire to five questions.

In today’s world of modern technology, innovation is at the center of a rapidly transforming, forward-paced way of life. Innovation is arguably the most important tool that a company can use in order to be competitive in the global race for progress (Tohidi and Jabbari Citation2011; Filippetti and Archibugi Citation2010). The double challenge of firm innovation and gender equality has become one of the most dominant issues for the post-Communist economies in Europe and Asia, transiting from state-owned centralized systems to market-based economies (Beer Citation2009; Brown Citation2004; Febbrajo and Sadurski Citation2010; Hellman Citation1998). This economic transition went hand-in-hand with major political restructuring of totalitarian system (with pronounced pseudo-equality agenda), witnessing transition to democracies in some cases (Eastern Europe) or consolidation of autocracies and hybrid regimes in other cases (Central Asia) (Hale Citation2015;; Yurchak Citation2013; Wilson Citation2005; Wedel Citation2003; Pop-Eleches and Tucker Citation2017 Gerber and Hout Citation1998). In the turbulent context of economic and political transition, gender rights, in general, and the place of women in entrepreneurship, in particular, came to the attention of scholars (Pollert Citation2003; Gheaus Citation2008; Nikolić-Ristanović Citation2004; Hurubean Citation2013; Hrycak Citation2002, Citation2006; Beissinger and Kotkin Citation2014). However, despite these growing studies on gender rights and social inequalities as historical legacies, there is still a need to consider the gender approach within entrepreneurship in post-Communist societies. Do women exhibit a different pattern of entrepreneurial behavior as compared to men in post-Communist societies? So far, studies have looked at the role of female directors on firm performance (Burke Citation1997; Chen, Leung, and Evans Citation2018; Konrad, Kramer, and Erkut Citation2008; Jurkus, Park, and Woodard Citation2011; Torchia, Calabrò, and Huse Citation2011), adopting CSR practices (Ibrahim and Angelidis Citation1994; Zou et al. Citation2018; Alonso‐Almeida, Perramon, and Bagur‐Femenias Citation2017; Kato and Kodama Citation2018) and positive business equity and valuation (Glass and Cook Citation2018; Adhikari, Agrawal, and Malm Citation2019; Martin, Nishikawa, and Williams Citation2009; Peni and Vähämaa Citation2010; Palvia, Vähämaa, and Vähämaa Citation2020). Fewer works have explored firm innovation in the context of female leadership (Reutzel, Collins, and Belsito Citation2018; Chatterjee and Ramu Citation2018). Our study aims to fill this gap in the literature.

Firm innovation can be defined as actions that create new ideas, processes, or products, which lead to positive effective changes in business performance (Betz Citation1987; Afuah Citation2003; Slater Citation1996). In other words, innovation collectively describes firm activities that lead to creating new value or capturing value in a new way that lends the company a competitive edge in the market (Schumpeter Citation1934; Chander, Keller, and Lyon Citation2000). It follows, therefore, that innovation is a crucial consideration for most organizations. It is thought to be the “key to success” for survival and flourishing in a market-based economy (Tohidi and Jabbari Citation2012). Firm innovation is also of great importance for the country overall, contributing to a nation’s long-run economic performance (Solow Citation1956; Romer Citation1986; Nazarov and Obydenkova Citation2020; Merikull Citation2010; Bradley et al. Citation2012; Scherer Citation1999; Song and Song Citation2017). The global market has forced nations, including post-Communist states, into competition for creating and assimilating knowledge and technology to propel their prosperity. Nowadays, whether a country is competitive in the global platform depends more on the capacity of its industry to innovate than its natural endowments (Porter Citation1990). Romer’s model (Citation1990) suggests that encouraging greater allocation of resources to innovative activity increases a country’s potential for economic growth. Thus, policymakers are interested in unveiling practices and policies that promote innovation in workplaces and, consequently, in the whole society.

In a perfectly competitive society with symmetric information flow, female workers should be self-selected uniformly to industries and occupations based on their competitive advantages and interests. However, many reports (Branson Citation2012; Geiler and Renneboog Citation2015; Reutzel, Collins, and Belsito Citation2018; Konrad, Kramer, and Erkut Citation2008; Torchia, Calabrò, and Huse Citation2011) continuously point toward the fact that females are stuck in low-reward positions. Discriminatory practices against female workers are institutionalized in many developing nondemocratic or semi-democratic societies. Our empirical strategy aims to reveal whether we can observe equal propensities to innovate for female and male managers if the political institutional and sector-level differences are properly controlled. Our goal is to demonstrate how a variety of political regimes can be accounted for different outcomes in gender issues and firm innovation. Using two indicators of female leadership, the firm ownership and being a top manager, out of twelve estimated models (two measures of female leadership and six definitions of firm innovation), only in four models, we find evidence of the negative disparity in firm innovation among female leaders. The additional analysis reveals that these disparities can be explained by the moderating impact of democratization on firm innovation. With the increase in civil liberties and political rights of citizens, disparities in firm innovation vanish entirely in all but one definition of firm innovation. Female managers may be persistently less likely to invest in research and development (R&D) even in more democratic societies. The propensity to spend on R&D is only 2% points less as compared to male managers, the group that has a considerably low propensity, only 9%. Thus, the low propensity to invest in R&D for both types of managers may suggest that low investment in R&D exists in general in transition economies.

The paper is structured in the following way. Section 2 consists of recent academic discussion on female leadership and its role in firm innovation, democratization, and historical legacies of Communism. This discussion helps to elaborate on the mechanism through which female leadership may influence firm innovation. Section 3 further develops our empirical model and discusses the primary data sources and the descriptive statistics for our firms’ sample. In Section 4, we report our main results. The final section concludes.

Female Leadership and Firm Innovation: Historical Legacies and Democracy

As female participation and leadership in organizations increase, it is worth assessing the relationship between female-led firms and innovation. In the 1980s, Hisrich and Brush (Citation1984) suggested that firms founded by women are more likely to focus on modifying existing products or services than innovation of new ones. Extant research in psychology and behavior suggests that women are more risk averse compared to men (Byrnes, Miller, and Schafer Citation1999; Jianakoplos and Bernasek Citation1998). Since innovation represents a culmination of risky processes with no guarantee of positive results, female-led companies tend not to pursue innovation opportunities (Ding, Murray, and Stuart Citation2006; Marvel, In, and Wolfe Citation2015; Whittington and Smith-Doer Citation2005). There are many possible explanations for this. In most parts of the world, women in business face more challenges in obtaining resources and capital than men (Reutzel, Collins, and Belsito Citation2018). This can lower their inclination toward innovative pursuits. Women managers face additional challenges due to the dominant masculine nature of management culture (Watts Citation2009). Furthermore, women experience disadvantages in accumulating wealth and have expressed that they face lower distributive justice and unfavorable environment (Deere and Doss Citation2006; Warren, Rowlingson, and Whyley Citation2001; Reutzel, Collins, and Belsito Citation2018). This perception, whether true or not in a particular society, is likely to discourage their motivation for taking on additional financial risk through innovative ventures.

In contrast, an opposing body of research suggests that women are more likely to participate in innovation. Female directors enhance effectiveness of internal governance (Adams and Ferreira Citation2009). Higher levels of monitoring from female leaders in business push managers to improve process efficiency and innovate (Aghion, Reenen, and Zingales Citation2013). More women on board (critical mass of at least 3) have been evidenced to allow female directors to make substantial contribution to innovation and strategic tasks (Torchia, Calabrò, and Huse Citation2011). Female CEOs and board members demonstrate stronger business and equity practices (Glass and Cook Citation2018). Studies suggest that organizational innovation is encouraged by gender diversity, and there is evidence that when women do not feel outnumbered, their contribution to management and innovative strategy becomes more significant (Busaibe et al. Citation2017; Torchia, Calabrò, and Huse Citation2011). Filculescu (Citation2016) claims that while variation exists across countries and regions, female-led firms demonstrate more innovative behavior than male-led firms. VanderBrug (Citation2013) suggests that female entrepreneurs in developed nations are equally or more prone to introduce innovative products and services to the market than male entrepreneurs. However, the difference between developed democracies and developing world, nondemocratic and hybrid regime with undermined gender rights, should be considered. Higher democratization is argued to be associated with higher participation of women in business and politics (Donno and Russett Citation2004; Inglehart, Norris, and Welzel Citation2003). Richards and Gelleny (Citation2007) find democracy to be positively related to several indicators of women empowerment. Yet, studies have also found contradictory evidence. Paxton (Citation1997) found democracy to be insignificant or inversely related to female representation. Similarly, Seguino (Citation2000) found a correlation between greater inequality and economic growth, and Arora (Citation2012) found that states in India with higher gender inequality have higher income per capita. Based on this literature, it can be theorized that female leaders may have high potential for facilitating firm innovation but face barriers due to existing cultural perceptions and national policies.

From the historical perspective, female leadership in developing countries of Asia indicates that women are well-adapted to manage finances and organization departments due to long-standing religious and cultural traditions (Adler Citation1993). In the Americas and Europe, women played an active role in commerce during the 18th and 19th centuries. From owning land, operating businesses, holding shares to seeking and holding patents, women were involved in invention and manufacturing, motivated by market incentives (Swanson Citation2011). Since that era, much progress has taken place from the perspective of gender equality in many spheres of human life, yet significant gaps still exist in knowledge regarding the intersection of entrepreneurship, innovation, and gender (Filculescu and Cantaragiu Citation2012). How, if at all, is the closing gap of gender disparity mirrored in firm innovation across European and Central Asian Post-Communist regions?

There also exists a discrepancy between the increasing number of women graduating from university with STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics) degrees and persisting low number of women in senior leadership positions in all sectors, especially those associated closely with innovation. A study based in the UK showed that the few women who are able to climb the corporate ladder find their success tied to their ability to assimilate into masculine styles of management (Watts Citation2009). It is widely accepted that national policies affect the extent and prevalence of innovation in the country’s businesses. Subsequently, it becomes necessary to evaluate whether such policies are guided with gender-neutral awareness. A study comparing policies of Sweden and Canada found that the Swedish government employs deliberate actions to increase visibility of women in innovation leadership (Rowe Citation2018). This aligns with the high level of gender equality in Sweden. Studies have also found that moving toward more democratic societies increases the propensity of firm innovation (Nazarov and Obydenkova Citation2020). The impact of national institutional forces on women in leadership remains undertheorized. Research suggests that democracy reinforces gender equality (Welzel, Norris, and Inglehart Citation2002). Countries with higher levels of democracy and longer experience of women’s suffrage have higher female participation in labor and commerce (Beer Citation2009). Research suggests that democracy is necessary, albeit not sufficient, for true gender equality. Inglehart, Norris, and Welzel (Citation2003) argues that growing emphasis on gender equality is essential in the process of democratization, and Piccone (Citation2017) suggests that the relationship between democracy and gender equality is mutually reinforcing.

Building on these studies, we test the importance of the level of democracy for post-Communist states in Europe and Central Asia. Eastern European states are quite unique in terms of democratization path, as they were heavily influenced by not only the European Union (EU) and democracies-led Regional Development Banks (e.g., the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD), but also private banks in Europe associated with it “stick-and-carrot” mechanisms of democratization, sustainable development, with focus on corporate social responsibility, promotion of human rights, and gender representation at all levels (Anderson and Shawn Reichert Citation1996; Anderson and Singer Citation2008; Obydenkova Citation2012; Obydenkova and Rodrigues Vieira Citation2020; Obydenkova et al. Citation2021; Carrubba Citation1997; Lankina, Libman, and Obydenkova Citation2016a; Djalilov and Hartwell Citation2021). Studies addressed in detail the powerful role of the EU in democratization and promotion of human rights (including gender equality) among other issues in European neighborhood and beyond. However, the EU’s impact on democratization, sustainable development, and human rights was undermined by the Great Recession 2008, reducing institutional and social trust that negatively associated with risk to invest (e.g., Armingeon and Guthmann Citation2014; Arpino and Obydenkova Citation2020; Boomgaarden et al. Citation2011; Mišić and Obydenkova Citation2021; Obydenkova and Arpino Citation2018; Armingeon and Ceka Citation2013). In other words, in the aftermath of the Great Recession the priority is “to survive,” not to innovate. The Recession also increased radically the risks of investment in general and in firm innovation in particular.

In contrast to post-Communist European states, other former Communist countries (e.g., Central Asia) did not experience the democracy diffusion and promotion of the EU and other Western actors (such as regional development banks and the EBRD). On the contrary, it was involved in the deep network of autocracies-led regional international organizations such as the Commonwealth of Independent States, Eurasian Economic Union – both led by Russia and the Shanghai Cooperation Organizations led by China (Ambrosio, Hall, and Obydenkova Citation2021; Hall, Lenz, and Obydenkova Citation2021; Hartwell Citation2021). Both China and Russia are notoriously famous for undermining human rights and social discrimination in particular (e.g., Demchuk et al. Citation2021). As previous research demonstrated, membership in their respective regional international organizations (IOs) serves as a tool for diffusion of practices and principles of nonsustainable development and ideological behavior (see, for example, Cooley Citation2012; Izotov and Obydenkova Citation2021; Hall, Lenz, and Obydenkova Citation2021). Therefore, to understand the empirical dynamics of gender issues in firm innovation across two very different post-Communist regions, we look into the case of eastern European States (with high level of democracy) and Central Asian states (with low level of democracy). Focusing on exclusively post-Communist economies allows us to control for important historical legacy of Communism that casts a long shadow on modern day economic development and human rights in the region.

Given the strong presence of historical legacies across post-Communist regions (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln Citation2007; Hale Citation2015; Hellman Citation1998; Lankina, Libman, and Obydenkova Citation2016b), it is important to understand how it affects social inequalities and gender rights. The ideology of Communism was based on the idea of “quality” that was often interpreted as “similarities,” not as equality of rights (Western tradition; Wedel Citation2003; Gerber and Hout Citation1998; Millar Citation1994; Barany and Volgyes Citation1995). The understanding of “human rights” and “gender rights,” therefore, was interpreted as similarities – that is similar (equal) salaries, access to goods, access to traditionally male-dominant sector of work (e.g., construction of railroads relying on physical force – mail dominant sector). It is not surprising that gender rights interpreted from this perspective of similarities had nothing to do with Western interpretation of women rights, that is, based on recognition of the differences among men and women (e.g., accounting for pregnancy, childbearing, and maternity rights) (Bandelj and Mahutga Citation2010; Gerber and Hout Citation1998; Millar Citation1994). The Communist interpretation of gender rights, thus, tends to result in the opposite outcomes for women and their role in society, politics, and professional careers. Claiming no gender differences, the Communist system was built to ignore the differences of female participation at all levels and professions. The best example would be the gender balance within the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CSPU) from 1917 to 1991 (Libman and Obydenkova Citation2021). The predominant literature on the survival of these historical legacies in post-Communist states indicates strong heritage of social and economic inequalities, including but not limited gender inequalities (Libman and Obydenkova Citation2019, Citation2020). Within these debates, we select a sample of post-Communist states that is expected to reflect the historical legacies, yet, to a different extent. Eastern European states were part of Communist camp, however, not part of the Soviet hegemon, the USSR. They experienced faster and relatively more successful democratization and marketization, as compared to former Soviet Republics, including post-Soviet Central Asian states. Looking at two geographically different regions allows us to trace the impact of democratization in Eastern Europe and the persistence of historical legacies in Central Asia. Both regions present an interesting contrast in terms of social inequalities and gender rights that we test with the empirical model described below.

Data and Empirical Model

The BEEPS survey offers a large data set of private and public enterprises. The survey is conducted mainly in Eastern European, post-Communist countries transitioning to capitalist democracy. The survey was primarily developed to study the impact of transition on small- and medium-sized firms (Mannasoo and Merikull Citation2014; Nazarov and Akhmedjanov Citation2012; Rraci Citation2010). In this analysis, we use the 2012 wave of the BEEPS. The main independent variables (X) are the indicators whether among the major owners of the firm are there any females or whether the top manager is a female. shows that among 11,617 firms (i) in the sample, 32% owned by females and 20% employ female top managers.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of key dependent variables

In the 2012 wave, the BEEPS sample has information on 15,883 firms. We drop from the sample the firms representing Turkey (1,344 firms), Mongolia (360 firms), Kosovo (202 firms), and Montenegro (150 firms). We drop Turkish firms because Turkey was not part of the Socialistic block. Second, we omit Kosovan and Montenegrin firms because these two countries with Serbia comprised one country in the initial transition stage until gaining independence in the later years. Third, we drop Mongolia due to its geographic remoteness from other post-Communist republics. With this sample selection strategy, our sample consists of 13,827 firms. Of these firms, 11,617 are private firms, which comprise our final sample. Finally, we drop 2,200 public firms and ten firms with the unknown ownership structure.

Dependent Variables (Y)

One of the advantages of BEEPS is that the 2012 data contains five variables identifying firm involvement in innovative activity. In the BEEPS, three variables identifying firm innovation are the same across different waves: whether the firm introduced new products/services or new production and supply methods and whether the firm spent on R&D in the last three years. demonstrates that the firms with female ownership have higher propensities to innovate in all three measures. Firm innovation is 25.6%, 20.1%, and 9.4% in firms with female owners versus 24%, 18.7%, and 9% in firms without females in ownership or top management, respectively. Another important trend in is that the firms with female top management lag in firm innovation in all three categories of innovation.

In the 2012 wave of BEEPS, the two additional definitions of firm innovation were included in the questionnaire: whether the firm has involved in new organizational management practices and whether the firm has introduced new marketing plans in the last three years. Similar to the previous three definitions of firm innovation, the firms with female ownership are more likely to be involved in these types of firm innovation than firms with women only in top management or firms without women in either ownership or top management. Finally, we create a firm innovation index that sums up the number of innovative activities across all categorizations of firm innovation. A typical firm owned by female is involved in at least one innovative activity, while firms of the other two categories lag slightly in firm innovation.

Independent Variables (I, F, and G)

In the analysis, we introduce three types of variables to quantify the relationship between female leadership and firm innovation: industry indicators and firm-level and country-level characteristics.

Industry Indicators (I)

Women may self-select themselves into specific industries, and firm innovation can vary widely across these industries. To capture the selection mechanism into high-reward industries, we use four categories of firm industry, namely, sales, services, construction, and manufacturing. shows that females are more likely to own firms or to be assigned to top management positions in the sales industry. They are less likely to be owners or top managers in construction and manufacturing industries, which are more rewarding industries in the transition economies.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics on key variables

Firm-level Characteristics (F)

Female leadership may have varying impacts on various firm characteristics. shows that females are more likely to be owners or top managers of small enterprises rather than large enterprises. Comparing firms by other characteristics, firms with female owners have a less educated workforce and are less likely to be sole proprietors than the second types of firms. Firms with female top management are less likely to have foreign certifications but are more likely to be sole proprietors.

Country-level Characteristics (G)

The macroeconomic and institutional differences may explain the differences in female leadership across different countries. The main country-level characteristic that we test for moderating impact on firm innovation is the democracy index. We use the index from Freedom House representing a composite score of political rights and civil liberties in a society, with value “1” representing the least free democratic society and “7” representing the freest democratic society. shows that the female ownership or top management decreases with democracy. Some other country-level characteristics impacting the role of women in the management structure are fertility rate, female labor supply, and GDP per capita.

Empirical Model

The empirical model that tests our main hypothesis of the study is as follows:

where subscripts denote a firm located in the

country.

The primary interest is coefficient , which measures the difference in firm innovation,

, for female-owned or female-managed firm after controlling for industry-level fixed effects, firm-level characteristics, and country-level characteristics. Since the selected country-level factors may not capture all institutional and macroeconomic differences across transition economies, in a more flexible specification, we estimate the model with country-level fixed effects,

, without controlling for country-level characteristics, which are invariant across the firms from the same country. If

is not different from zero, then we can conclude that the difference in firm innovation is explained by observed firm and industry- and country-level differences across the countries and gender plays no role in the propensity to innovate. Clustered over country, robust standard errors are used in the statistical inferences.

Results

In this section, we report the coefficients associated with female leadership variables from three variants of EquationEquation (1)(1)

(1) . In Model 1, we control for industry and firm characteristics discussed in the previous section. In Model 2, we add to the model the country-level characteristics presented in . In Model 3, instead of the country-level characteristics, we control for country-level fixed effects. We report the full results including all coefficients of Model 2 in Appendices A and B.

In , we start the discussion of the findings for female ownership’s coefficients. In Model 1, for five out of the six definitions of firm innovation, female ownership is associated with higher firm innovation. Firms with female owners introduced new products or new production methods by 2% point more frequently than their counterpart firms. The female owners are also more likely to introduce new organizational management practices by 2.4% points or new marketing methods by 3.5% points. They also have higher innovation scores by 0.1 points. After adding country-level controls, the coefficient decreases in magnitude, and the statistical significance at the 5% level is preserved for only two of the definitions. Finally, in the model with the country-level fixed effects only for the new marketing methods, female ownership is associated with higher firm innovation. However, the coefficient's magnitude is only a 1.5%-point advantage and is marginally insignificant at the 5% level.

Table 3. Firm innovation and female ownership relationship for various measures of innovation

In , we report results for the similar analysis but for the indicator of female top management as the main independent variable. In the model with only industry indicators and firm-level characteristics, a substantial disadvantage in firm innovation is present for two definitions of innovation: introduction of new products and services and the presence of spending on R&D. For all other definitions, the difference in firm innovation is close to 0. There are no substantial changes in the model with added country-level characteristics. However, in the model with the country-level fixed effects, for four out of six definitions, we observe disadvantages in firm innovation for the firms with female top management. The level of disadvantage is 2.9% points for introduction of new products and services, 2% points for introduction of new production and supply methods or any spending on R&D, and 0.07 points for the innovation index.

Table 4. Firm innovation and top manager relationship for various measures of innovation

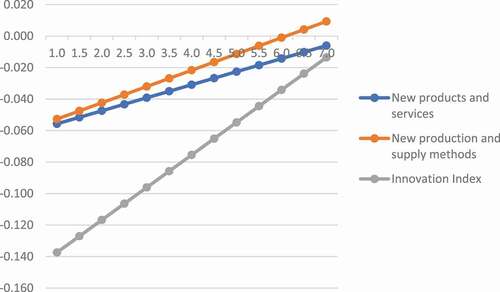

In , we test the hypothesis whether the level of society’s democratization may explain the disadvantage in firm innovation for female top managers. For three out of four definitions of firm innovation with documented disadvantages in the previous analysis, we find that the democracy may explain the lag in firm innovation for female top managers. The coefficient corresponding to the interaction term between the indicator of female top management and democracy is positive in the regressions with dependent variables new products and services, new production and supply methods, and innovation index. In , we simulated the disadvantage’s magnitude for different levels of democracy and in all three instances, we observe that in consolidated democracies, the female top management disadvantage in innovation completely disappears.

Table 5. Firm innovation and top manager relationship for various measures of innovation

Conclusion

We find that, when controlling for industry- and firm-level characteristics, female-owned firms have a 2–3.5% higher propensity to innovate than male-owned firms through introduction of new products and services, production and marketing methods, and management practices. Additionally, female-led firms were found to have an 0.11 points higher innovation score than male-led firms in our analysis. In other words, female ownership has a positive association with firm innovation. However, the association becomes weaker when controlling for the country-level characteristics, and completely disappears when controlling for country-level fixed effects. Thus, we conclude that for most definitions of firm innovation, there is no significant difference in pursuing in innovative activities between female-owned firms and male-owned firms.

Interestingly, results show that female-owned firms are probably more likely to introduce new marketing methods. Some researchers allege that women are better marketing strategists than men. Ritson (Citation2008) suggests that women’s genetic disposition for empathy, ability to connect with people (and therefore, consumers), strong perceptual skills, and intuitive thinking are some of the reasons why they are frequently seen to outperform men in marketing. The psychological dimension of this analysis should, however, remain on the agenda for further studies. The implication of our results indicates that female CEOs may better understand the importance of robust marketing strategies in growing their firm’s bottom line and, therefore, prioritize continual improvement in that area. A set of experiments conducted by Cronson and Gneezy (Citation2009) provide empirical evidence that women are more situationally specific, a skill required to identify the best marketing strategies for the specific context or product. Although the same study demonstrated that women are neither more nor less socially oriented, however, their social preferences are more adjustable supporting the given thesis. This notion is echoed in existing research that evidences females having a better understanding of consumer behavior and marketing opportunities for companies (Byrnes, Miller, and Schafer Citation1999).

Furthermore, our initial analysis indicates that firms with females in top management have lower propensity to innovate than male-managed firms. After controlling for the moderating impact of democratization, female managers are less likely to invest only in R&D. This supports extensive research that suggests that women are more risk-averse than men (Byrnes, Miller, and Schafer Citation1999; Arch Citation1993) and are less likely to pursue high-risk/high-reward ventures (Kepler and Shane Citation2007). R&D is a direct path to innovation, and investment in R&D is a widely used measure of firm innovation. However, it also represents a considerable risk of low to no or delayed returns (McAdam et al. Citation2010; Pettigrew, Woodman, and Cameron Citation2001). This may explain why female managers experience higher apprehension associated with R&D expenditure and therefore be less inclined to pursue innovative opportunities (Alvarez and Busenitz Citation2001; Withers, Drnevich, and Marino Citation2011).

This study reveals a disadvantage in firm innovation for firms with women in top management. Research shows that women experience difficulty in gaining access to capital and human resources for pursuing innovation (Cliff Citation1998; Wu and Chua Citation2012). Furthermore, women have been reported to perceive innovation opportunities as unfavorable because they experience a lack of environmental munificence and low distributive justice in allocation of economic rewards in business compared to their male counterparts (Roper and Scott Citation2009; Zhao, Seibert, and Hills Citation2005; Reutzel, Collins, and Belsito Citation2018). However, our analysis demonstrates that these same firms with female top management would experience no lesser levels of innovation in a more democratic society. In other words, our results suggest that democracy promotes the firm innovation for firms with female top management.

This finding underscores the significance of societal and country-level factors in influencing innovation in firms with female leadership, supporting Lindberg’s (Citation2012) claim that national policies play an important role in shaping women’s participation in innovation. The results of this study may prompt policymakers to evaluate their approach to innovation policy and improve gender equality. Andersson et al. (Citation2012) suggests that the gender-neutral approach to innovation policy may be responsible for the gender gap in innovation leadership. In fact, innovation policies have especially eluded gendering and identity (Nählinder, Tillmar, and Wigren Citation2015). Our findings, thus, are in line with the literature arguing that democratization facilitates and augments women’s participation in business and government (Donno and Russett Citation2004; Inglehart, Norris, and Welzel Citation2003; Richards and Gelleny Citation2007). Our research supports this argument by illustrating that the disadvantages faced by firms with female top management in pursuing innovative ventures disappear when consolidated for a higher democracy index.

We also find additional confirmation on the tendency of women to avoid taking on investment risks due to experiencing lower financial security and distributive justice. Since firm innovation represents substantial financial risks, our results indicate that higher levels of democracy in society may ameliorate the environmental difficulties faced by women in leadership positions. Firm innovation is designed to create value for the firm’s performance and output, leading to improved returns. In a society where female-led and female-managed firms are able to participate in firm innovation, at least to the same extent as their counterparts, women in business would achieve greater success and be better positioned to contribute to economic growth.

The participation of women in firms has witnessed rapid growth since the turn of the century. This is especially evident in advanced democratic economies (King et al. Citation2017; Brown Citation2004; Tinkler et al. Citation2015). Tyrowicz, van der Velde, and Goraus (Citation2018) also looked into the overall gender employment gaps across advanced democracies versus transitional societies, while the study points to the “gender employment gaps on nearly 1500 micro databases from over 40 countries” using employment in general. In contrast, our study contributes to very specific niche of the entrepreneurial job market via looking at top leadership positions and, thus, leadership per se and gender behavior at top-ranked positions. Other studies nuanced different types of markets that condition gender status and behavior (e.g., in the scientific and academic market, gender status was investigated in Whittington and Smith-Doer Citation2005 showing trends different from other markets). To the best of our knowledge, this issue has not yet been addressed within transitional economies, with implications for firm innovations and variation in democracy stock. Previous studies addressed implications of democracy stock for public health and even for environmental performance but has not yet considered gender and social inequality (Nazarov and Obydenkova Citation2021a, Citation2021b). Other studies suggested that gender equality is not simply a consequence of democratization but also a contributing factor to the process of transition (Inglehart, Norris, and Welzel Citation2003). Our findings, thus, contribute to this literature on the nexus of gender equality and democracy in general, approaching it from a very different behavioral and entrepreneurial perspective unleashing psychological dimension in gender studies as conditioned by political context and historical legacies (Alesina and Fuchs-Schündeln Citation2007; Pop-Eleches and Tucker Citation2017; Beissinger and Kotkin Citation2014; Libman and Obydenkova Citation2021a; Barany and Volgyes Citation1995). For example, within nondemocratic context, the study demonstrated that while female workers pay more attention to leadership than male ones, they still assume traditional “gender roles” instead of leadership roles (Erzikova and Berger Citation2016). Even more so, within a nondemocracy (in this case Russia), the study argues that “female top leaders in organizations did not desire leadership” (p. 28). Given the growing engagement of women in the workplace, the emerging implications of gender equality on democracy and vice versa are worth deeper exploration. Within the limits of this study, the findings suggest a positive relation between democracy and female firm innovation even within post-Communist societies.

A few broader issues are to be mentioned within the spirit of possible limitations of this study and future research agenda. First, it is highly important to recognize that a number of factors, such as large, geopolitics, culture, religion, historical legacies, and the level of (de-)centralization may all have altered the results. For example, within a geographically large states such post-Communist and Communist states as Russia, China, or Kazakhstan, the findings can differ across subnational regions (Wedel Citation2003; Cooley Citation2012). Second, the membership within the regional international organizations (such as not only the EU and the EBRD, on the one hand, but also the Eurasian Economic Union, on the other hand) was proven to be crucial for sociopolitical changes and economic development (Armingeon and Ceka Citation2013; Hartwell Citation2021; Libman and Obydenkova Citation2013, Citation2018a, Citation2018b; Agostinis and Urdinez Citation2021; Ambrosio, Hall, and Obydenkova Citation2021). According to these studies, the membership in these so-called “regional clubs” has implications for a wide array of issues. Hence, it is plausible that membership may also have consequences for social inequality in general and gender approach in particular, thus affecting the position of female employees on the market at all levels. However, intriguing these issues are as follows: they have to stay on the agenda for future research on gender behavior, social inequality, and female leadership.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (25.1 KB)Acknowledgments

Anastassia Obydenkova thanks the Basic Research Program of the National Research University Higher School of Economics (HSE University) and the Center for the Institutional Studies of the HSE University for supporting her research. We are grateful to two anonymous reviewers of this paper for their comments and feedback. The authors of this project are listed alphabetically; they contributed equally to this paper and they share the lead authorship of this project.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Adrita Iman

Adrita Iman is an IT Systems Analyst for Vera Bradley. She completed her MBA with a concentration in Business Analytics from Purdue University Fort Wayne (2020) where she worked on research in economics, marketing and information systems.

Zafar Nazarov

Zafar Nazarov (Ph.D. in Labor Economics, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2009) is an Associated Professor of Economics at Purdue Fort Wayne. He was a post-doctoral fellow at Rand Corporation sponsored by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development.

Anastassia Obydenkova

Anastassia Obydenkova is an Associate Professor, the Institute for Russian and Eurasian Studies, Uppsala University (Sweden). She holds PhD in Political Science from the European University Institute (Florence). She was awarded a Fung Fellowship at Princeton University, Fox Fellowship at Yale University, and Davis Senior Scholarship at Harvard University.

References

- Barany, Z., and I. Volgyes, eds. 1995. The Legacies of Communism in Eastern Europe. John Hopkins University, Baltimore, Maryland: JHU Press.

- Andersson, S., K. Berglund, E. Gunnarsson, and E. Sundin, eds. 2012. Promoting Innovation: Policies, Practices and Procedures. Stockholm: Vinnova.

- Beissinger, M., and S. Kotkin, eds. 2014. Historical Legacies of Communism in Russia and Eastern Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Adams, R. B., and D. Ferreira. 2009. “Women in the Boardroom and Their Impact on Governance and Performance.” Journal of Financial Economics 94 (2): 291–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2008.10.007

- Adhikari, B. K, A. Agrawal, and J. Malm. 2019. “Do Women Managers Keep Firms Out of Trouble? Evidence from Corporate Litigation and Policies.” Journal of Accounting & Economics 67 (1): 202–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2018.09.004

- Adler, N. 1993. “Asian Women in Management.” International Studies of Management & Organization 23 (4): 3–17.

- Afuah, A. 2003. Innovation Management: Strategies, Implementation and Profits. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Aghion, P., J. V. Reenen, and L. Zingales. 2013. “Innovation and Institutional Ownership.” American Economic Review 103 (1): 277–304. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.103.1.277

- Agostinis, Giovanni, and Francisco Urdinez. 2021. “The Nexus between Authoritarian and Environmental Regionalism: An Analysis of China’s Driving Role in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization.” Problems of Post-Communism. 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2021.1974887.

- Alesina, A., and N. Fuchs-Schündeln. 2007. “Goodbye Lenin (Or Not?): The Effect of Communism on People’s Preferences.” American Economic Review 97 (4): 1507–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.97.4.1507

- Alonso‐Almeida, M. M., J. Perramon, and L. Bagur‐Femenias. 2017. “Leadership Styles and Corporate Social Responsibility Management: Analysis from a Gender Perspective.” Business Ethics 26 (2): 147–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12139

- Alvarez, S. A., and L. W. Busenitz. 2001. “The Entrepreneurship of Resource-based Theory.” Journal of Management 27 (6): 755–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/014920630102700609

- Ambrosio, T., A. Hall, and A. Obydenkova. 2021. “Sustainable Development Agendas of Regional International Organizations: The European Bank of Reconstruction and Development and the Eurasian Development Bank.” Problems of Post-Communism. 1–13. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2021.1979412;.

- Anderson, Christopher J., and Matthew M. Singer. 2008. “The Sensitive Left and the Impervious Right: Multilevel Models and the Politics of Inequality, Ideology, and Legitimacy in Europe.” Comparative Political Studies 41 (4–5): 564–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414007313113

- Anderson, Christopher, and M. Shawn Reichert. 1996. “Economic Benefits and Support for Membership in the EU: A Cross-National Analysis.” Journal of Public Policy 15 (3): 231–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0143814X00010035

- Arch, E. 1993. “Risk-taking: A Motivational Basis for Sex Differences.” Psychological Reports 73 (1): 6–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1993.73.1.3

- Archibugi, D., and Filippetti, A., (2010). The Globalization of Intellectual Property Rights: Four Learned Lessons and Four Thesis, Global Policy Four Learned Lessons and Four Thesis, Vol. 1 (2), pp.137–149.

- Armingeon, Klaus, and Besir Ceka. 2013. “The Loss of Trust in the European Union during the Great Recession since 2007: The Role of Heuristics from the National Political System.” European Union Politics 15 (1): 82–107. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116513495595

- Armingeon, Klaus, and Kai Guthmann. 2014. “Democracy in Crisis? The Declining Support for National Democracy in European Countries, 2007 – 2011.” European Journal of Political Research 53 (3): 423–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6765.12046

- Arora, R. U. 2012. “Gender Inequality, Economic Development, and Globalization: A State Level Analysis of India.” The Journal of Developing Areas 46 (1): 147. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jda.2012.0019

- Arpino, Bruno, and A. Obydenkova. 2020. “Democracy and Political Trust before and after the Great Recession 2008: The European Union and the United Nations.” Social Indicators Research 148 (2): 395–415. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02204-x.

- Bandelj, N., and M. C. Mahutga. 2010. “How Socio-economic Change Shapes Income Inequality in Post-Socialist Europe.” Social Forces 88 (5): 2133–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/sof.2010.0042

- Beer, C. 2009. “Democracy and Gender Equality.” Studies in Comparative International Development 44 (3): 212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12116-009-9043-2

- Betz, F. 1987. Managing Technology: competing through new ventures, innovation, and corporate research. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall.

- Boomgaarden, Hajo G., Andreas R. T. Schuck, Matthijs Elenbaas, and Claes H. de Vreese. 2011. “Mapping EU Attitudes: Conceptual and Empirical Dimensions of Euroscepticism and EU Support.” European Union Politics 12 (2): 241–66. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1465116510395411

- Bradley, S. W., J. S McMullen, K. Artz, and E. M. Simiyu. 2012. “Capital Is Not Enough: Innovation in Developing Economies.” Journal of Management Studies 49 (4): 684–717. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6486.2012.01043.x

- Branson, D. M. 2012. “Initiatives to Place Women on Corporate Boards of Directors-A Global Snapshot.” The Journal of Corporation Law 37 (4): 793.

- Brown, D. S. 2004. “Democracy and Gender Inequality in Education: A Cross-national Examination.” British Journal of Political Science 34 (1): 137–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0007123403210395

- Burke, R. 1997. “Women in Corporate Management.” Journal of Business Ethics 16 (9): 873–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017910317782

- Busaibe, L., S. Singh, S. Ahmad, and S. Gaur. 2017. “Determinants of Organizational Innovation: A Framework.” Gender in Management: An International Journal 32 (8): 578–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-01-2017-0007

- Byrnes, J., D. Miller, and W. Schafer. 1999. “Gender Differences in Risk Taking: A Meta-analysis.” Psychological Bulletin 125 (3): 367–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.125.3.367

- Carrubba, Clifford. 1997. “Net Financial Transfers in the European Union: Who Gets What and Why?” The Journal of Politics 59 (2): 469–96. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022381600053536

- Chander, G. N., C. Keller, and D. W. Lyon. 2000. “Unraveling the Determinants and Consequences of an Innovation-supportive Organizational Culture.” Entrepreneurship: Theory & Practice 25 (1): 59.

- Chatterjee, C., and S. Ramu. 2018. “Gender and Its Rising Role in Modern Indian Innovation and Entrepreneurship.” IIMB Management Review 30 (1): 62–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iimb.2017.11.006

- Chen, J., W. S. Leung, and K. P. Evans. 2018. “Female Board Representation, Corporate Innovation and Firm Performance.” Journal of Empirical Finance 48:236–54. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jempfin.2018.07.003.

- Cliff, J. E. 1998. “Does One Size Fit All? Exploring the Relationship between Attitudes Towards Growth, Gender, and Business Size.” Journal of Business Venturing 13 (6): 523–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0883-9026(97)00071-2

- Cooley, Alexander. 2012. Great Games, Local Rules: The New Great Power Contest in Central Asia. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cronson, R., and U. Gneezy. 2009. “Gender Differences in Preferences.” Journal of Economic Literature 47 (2): 448–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.47.2.448

- Deere, C. D., and C. R. Doss. 2006. “The Gender Asset Gap: What Do We Know and Why Does It Matter.” Feminist Economics 72 (1–2): 1. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13545700500508056

- Demchuk, A. L., M. Mišić, A. Obydenkova, and J. Tosun. 2021. “Environmental Conflict Management: A Comparative Cross-cultural Perspective of China and Russia.” Post-Communist Economies. 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2021.1943915.

- Ding, W. W., F. Murray, and T. E. Stuart. 2006. “Gender Differences in Patenting in the Academic Life Sciences.” Science 313 (5787): 665–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1124832

- Djalilov, Khurshid, and Christopher Hartwell. 2021. “Do Social and Environmental Capabilities Improve Bank Stability? Evidence from Transition Countries.” Post-Communist Economies. 1–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2021.1965359.

- Donno, D., and B. Russett. 2004. “Islam Authoritarianism, and Female Empowerment: What are the Linkages?” World Politics 56 (4): 582–607. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/wp.2005.0003

- Erzikova, Elina, and Bruce K. Berger. 2016. “Gender Effect in Russian Public Relations: A Perfect Storm of Obstacles for Women.” Women’s Studies International Forum 56:28–36. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2016.02.011

- Febbrajo, Alberto, and Wojciech Sadurski. 2010. Central and Eastern Europe after Transition: Towards a New Socio-legal Semantics (Studies in Modern Law and Policy). Surrey and Burlington: Ashgate.

- Filculescu, A., and R. Cantaragiu. 2012. “Innovation in the Creative Industries: Case Study of an Event Planning Company.” Annals of the Faculty of Economics 1 (1): 640–49.

- Filculescu, A. 2016. “The Heterogeneous Landscape of Innovation in Female-led Businesses – Cross-country Comparisons, Management & Marketing.” Challenges for the Knowledge Society 11 (4): 610–23.

- Geiler, P., and L. Renneboog. 2015. “Are Female Top Managers Really Paid Less?” Journal of Corporate Finance (Amsterdam, Netherlands) 35 (35): 345–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2015.08.010

- Gerber, T. P., and M. Hout. 1998. “More Shock than Therapy: Market Transition, Employment, and Income in Russia, 1991–1995.” American Journal of Sociology 104 (1): 1–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/210001

- Gheaus, A. 2008. “Gender Justice and the Welfare State in Post-Communism.” Feminist Theory 9 (2): 185–206. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1464700108090410.

- Glass, Christy, and Alison Cook. 2018. “Do Women Leaders Promote Positive Change? Analyzing the Effect of Gender on Business Practices and Diversity Initiatives.” Human Resource Management 57 (4): 823–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.21838

- Hale, H. E. 2015. Patronal Politics: Eurasian Regime Dynamics in Comparative Perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, Stephen G. F., Tobias Lenz, and Anastassia Obydenkova. 2021. “Environmental Commitments and Rhetoric over the Pandemic Crisis: Social Media and Legitimation of the AIIB, the EAEU, and the EU.” Post-Communist Economies. 1–26. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2021.1954824.

- Hartwell, Christopher A. 2021. Part of the Problem? The Eurasian Economic Union and Environmental Challenges in the Former Soviet Union. Problems of Post-Communism. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2021.1960173.

- Hellman, J. S. 1998. “Winners Take All: The Politics of Partial Reform in Postcommunist Transitions.” World Politics 50 (2): 203–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887100008091

- Hisrich, R. D., and C. Brush. 1984. “The Woman Entrepreneur: Management Skills and Business Problems.” Journal of Small Business Management 22 (1): 30–37.

- Hryak, Alexandra “Foundation Feminism and the Articulation of Hybrid Feminisms in Post-Socialist Ukraine.” . East European Politics and Societies 20 (1): 69–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0888325405284249. 2006

- Hrycak, Alexandra. 2002. “From Mothers’ Rights to Equal Rights: Post-Soviet Grassroots Women’s Associations.” In Women’s Activism and Globalization. Linking Local Struggles and Transnational Politics, edited by Nancy A. Naples and Manisha Desai, 64–82. Londres, New York: Routledge.

- Hurubean, Alina. 2013. “Gender Equality Policies, Social Citizenship and Democratic Deficit in the Post-Communist Romanian Society.” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 92:403–08. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.08.692

- Ibrahim, N. A., and J. P. Angelidis. 1994. “Effect of Board Members Gender on Corporate Social Responsiveness Orientation.” Journal of Applied Business Research 10 (1): 35–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.19030/jabr.v10i1.5961.

- Inglehart, Ronald, Pippa Norris, and Christian Welzel. 2003. “Gender Equality and Democracy.” Comparative Sociology 1 (3–4): 321–46.

- Izotov, V. S., and A. V. Obydenkova. 2021. “Geopolitical Games in Eurasian Regionalism: Ideational Interactions and Regional International Organisations.” Post-Communist Economies 33 (2–3): 150–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2020.1793584.

- Jianakoplos, N. A., and A. Bernasek. 1998. “Are Women More Risk Averse?” Economic Inquiry 36 (4): 620–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1998.tb01740.x

- Jurkus, A. F., J. C. Park, and L. S. Woodard. 2011. “Women in Top Management and Agency Costs.” Journal of Business Research 64 (2): 180–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.12.010

- Kato, T., and N. Kodama. 2018. “The Effect of Corporate Social Responsibility on Gender Diversity in the Workplace: Econometric Evidence from Japan.” British Journal of Industrial Relations 56 (1): 99–127. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bjir.12238

- Kepler, E., and S. Shane (2007), Are Male and Female Entrepreneurs Really that Different? The Office of Advocacy Small Business Working Papers, U.S. Small Business Administration, Office of Advocacy.

- King, Joe, Andrew M. Penner, Nina Bandelj, and Aleksandra Kanjuo-Mrčela. 2017. “Market Transformation and the Opportunity Structure for Gender Inequality: A Cohort Analysis Using Linked Employer-employee Data from Slovenia.” Social Science Research 67:14–33. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2017.07.002

- Konrad, A. M., V. Kramer, and S. Erkut. 2008. “Critical Mass: The Impact of Three or More Women on Corporate Boards.” Organizational Dynamics 37 (2): 145. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.orgdyn.2008.02.005

- Lankina, T. V., A. Libman, and A. Obydenkova. 2016b. “Appropriation and Subversion.” World Politics 68 (2): 229–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887115000428.

- Lankina, T., A. Libman, and A. Obydenkova. 2016a. “Authoritarian and Democratic Diffusion in Post-Communist Regions.” Comparative Political Studies 49 (12): 1599–629. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0010414016628270.

- Libman, A., and A. Obydenkova. 2013. “Informal Governance and Participation in Non-democratic International Organizations.” The Review of International Organizations 8 (2): 221–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11558-012-9160-y

- Libman, A., and A. Obydenkova. 2019. “Inequality and Historical Legacies: Evidence from Post-Communist Regions.” Post-Communist Economies 31 (6): 699–724. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2019.1607440.

- Libman, A., and A. V. Obydenkova. 2018a. “Understanding Authoritarian Regionalism.” Journal of Democracy 29 (4): 151–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jod.2018.0070

- Libman, A., and A. V. Obydenkova. 2018b. “Regional International Organizations as a Strategy of Autocracy: The Eurasian Economic Union and Russian Foreign Policy.” International Affairs 94 (5): 1037–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ia/iiy147

- Libman, A., and A. V. Obydenkova. 2020. “Proletarian Internationalism in Action? Communist Legacies and Attitudes Towards Migrants in Russia.” Problems of Post-Communism 67 (4–5): 4–5, 402–416. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2019.1640068.

- Libman, A., and Anastassia Obydenkova. 2021. Historical Legacies of Communism: Modern Politics, Society, and Economic Development. Cambridge (UK): Cambridge University Press.

- Lindberg, M. 2012. “A Striking Pattern – Co-construction of Innovation, Men, and Masculinity in Sweden’s Innovation Policy.”

- Mannasoo, K., and J. Merikull. 2014. “R&D, Credit Constraints, and Demand Fluctuations: Comparative Micro Evidence from Ten New EU Members.” Eastern European Economics 52 (2): 49–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/EEE0012-8775520203

- Martin, A. D., T. Nishikawa, and M. A. Williams. 2009. “CEO Gender: Effects on Valuation and Risk.” Quarterly Journal of Finance and Accounting 48 (3): 23–40.

- Marvel, M. R., H. L. In, and M. T. Wolfe. 2015. “Entrepreneur Gender and Firm Innovation Activity: A Multilevel Perspective.” IEEE Transactions on Engineering Management 62 (4): 558–67. doi:https://doi.org/10.1109/TEM.2015.2454993

- McAdam, R., S. Moffett, S. A. Hazlett, and M. Shevlin. 2010. “Developing a Model of Innovation Implementation for UK SMEs: A Path Analysis and Explanatory Case Analysis.” International Small Business Journal 28 (3): 195–214. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242609360610

- Merikull, J. 2010. “The Impact of Innovation on Employment: Firm-and Industry-level Evidence from a Catching-up Economy.” Eastern European Economics 48 (2): 25–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/EEE0012-8775480202

- Millar, W. 1994. The Social Legacy of Communism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Mišić, Mile, and Anastassia Obydenkova. 2021. “Environmental Conflict, Renewable Energy, or Both? Public Opinion on Small Hydropower Plants in Serbia.” Post-Communist Economies. 1–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2021.1943928.

- Nählinder, J., M. Tillmar, and C. Wigren. 2015. “Towards a Gender-aware Understanding of Innovation: A Three-dimensional Route.” International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 7 (1): 66–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-09-2012-0051

- Nazarov, Z., and A. Akhmedjanov. 2012. “Education, Training and Innovation in Transition Economies.” Eastern European Economics 50 (6): 25–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/EEE0012-8775500602

- Nazarov, Z., and A. Obydenkova. 2020. “Democratization and Firm Innovation: Evidence from European and Central Asian Post-Communist States.” Post-Communist Economies 32 (7): 833–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2020.1745565

- Nazarov, Z., and A. Obydenkova. 2021b. “Public Health, Democracy, and Transition: Global Evidence and Post-Communism.” Social Indicators Research. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-021-02770-z.

- Nazarov, Zafar, and Anastassia Obydenkova. 2021a. “Environmental Challenges and Political Regime Transition: The Role of Historical Legacies and the European Union in Eurasia.” Problems of Post-Communism. 1–14. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10758216.2021.1995437.

- Nikolić-Ristanović, V. 2004. “Post-Communism: Women’s Lives in Transition.” Feminist Review 76 (1): 2–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fr.9400151.

- Obydenkova, A. V., and V. G. Rodrigues Vieira. 2020. “The Limits of Collective Financial Statecraft: Regional Development Banks and Voting Alignment with the United States at the United Nations General Assembly.” International Studies Quarterly 64 (1): 13–25. Article sqz080. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/isq/sqz080.

- Obydenkova, A., and Bruno Arpino. 2018. “Corruption and Trust in the European Union and National Institutions: Changes over the Great Recession across European States.” Journal of Common Market Studies 56 (3): 594–611. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jcms.12646

- Obydenkova, A. 2012. “Democratization at the Grassroots: The European Union’s External Impact.” Democratization 19 (2): 2, 230–257. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13510347.2011.576851.

- Obydenkova, Anastassia, Rodrigues Vieira, G. Vinícius, and Jale Tosun. 2021. “The Impact of New Actors in Global Environmental Politics: The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development Meets China.” Post-Communist Economies. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14631377.2021.1954825.

- Palvia, A., E. Vähämaa, and S. Vähämaa. 2020. “Female Leadership and Bank Risk-taking: Evidence from the Effects of Real Estate Shocks on Bank Lending Performance and Default Risk.” Journal of Business Research 117:897–909. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.04.057.

- Paxton, P. 1997. “Women in National Legislatures: A Cross-national Analysis.” Social Science Research 26 (4): 442–64. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/ssre.1997.0603

- Peni, E., and S. Vähämaa. 2010. “Female Executives and Earnings Management.” Managerial Finance 36 (7): 629–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/03074351011050343

- Pettigrew, A. M., R. W. Woodman, and K. S. Cameron. 2001. “Studying Organizational Change and Development: Challenges for Future Research.” Academy of Management Journal 44 (4): 697–713.

- Piccone, T. (2017). Democracy, Gender Equality, and Security. Brookings. Retrieved from https://www.brookings.edu/research/democracy-gender-equality-and-security/.

- Pollert, A. 2003. “Women, Work and Equal Opportunities in Post-Communist Transition.” Work, Employment and Society 17 (2): 331–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017003017002006.

- Pop-Eleches, G., and J. A. Tucker. 2017. Communism’s Shadow: Historical Legacies and Contemporary Political Attitudes. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Porter, M. E. 1990. “The Competitive Advantage of Nations.” Harvard Business Review 68 (2): 73–93.

- Reutzel, C., J. Collins, and C. Belsito. 2018. “Leader Gender and Firm Investment in Innovation.” Gender in Management: An International Journal 33 (6): 430–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/GM-05-2017-0066

- Richards, D. L., and R. Gelleny. 2007. “Women’s Status and Economic Globalization.” International Studies Quarterly 51 (4): 855–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2478.2007.00480.x

- Ritson, M. 2008. “Why Women are the Superior Marketing Sex.” Marketing (253650): 26–29 https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/fair-trade-why-women-are-the-superior-marketing-sex/articleshow/3920849.cms.

- Romer, P. (1990). Endogenous Technological Change. Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 98(5), Part 2, pp. S71–S102.

- Romer, P. 1986. “Increasing Returns and Long-Run Growth.” Journal of Political Economy 94 (5): 1002–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/261420

- Roper, S., and J. M. Scott. 2009. “Perceived Financial Barriers and the Start-up Decision.” International Small Business Journal 27 (2): 149–71. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0266242608100488

- Rowe, A. M. 2018. “Gender and Innovation Policy in Canada and Sweden.” International Journal of Gender and Entrepreneurship 10 (4): 344–60. doi:https://doi.org/10.1108/IJGE-04-2018-0039

- Rraci, O. 2010. “The Effect of Foreign Banks in Financing Firms, Especially Small Firms, in Transition Economies.” Eastern European Economics 48 (4): 5–35. doi:https://doi.org/10.2753/EEE0012-8775480401

- Scherer, F. 1999. New Perspectives on Economic Growth and Technological Innovation. Washington, DC: British-North American Committee; Brookings Institution Press.

- Schumpeter, J. A. 1934. The Theory of Economic Development: An Inquiry into Profits, Capital, Credit, Interest, and the Business Cycle. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Seguino, S. 2000. “Gender Inequality and Economic Growth: A Cross-country Analysis.” World Development 28 (7): 1211. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(00)00018-8

- Slater, S. F. 1996. “The Challenge of Sustaining Competitive Advantage.” Industrial Marketing Management 25 (1): 79–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0019-8501(95)00072-0.

- Solow, R. M. 1956. “A Contribution to the Theory of Economic Growth.” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 70 (1): 65–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1884513

- Song, and Ligang Song. 2017. China’s New Sources of Economic Growth, vol. 2. Human capital, innovation and technological change (China Update Series).

- Swanson, K. W. 2011. “Getting a Grip on the Corset: Gender, Sexuality, and Patent Law.” Yale Journal of Law and Feminism 23:57.

- Tinkler, Justine E., Kjersten Bunker Whittington, Manwai C. Ku, and Andrea Rees Davies. 2015. “Gender and Venture Capital Decision-making: The Effects of Technical Background and Social Capital on Entrepreneurial Evaluations.” Social Science Research 51:1–16. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.12.008

- Tohidi, H., and Jabbari, M., (2011). The main requirements to implement an electronic city, Procedia Computer Science, Vol. 3, pp. 1106–1110

- Tohidi, H., and M. M. Jabbari. 2012. “The Important of Innovation and Its Crucial Role in Growth, Survival and Success of Organizations.” Procedia Technology 1:535–38. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.protcy.2012.02.116.

- Torchia, M., A. Calabrò, and M. Huse. 2011. “Women Directors on Corporate Boards: From Tokenism to Critical Mass.” Journal of Business Ethics 102 (2): 299–317. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0815-z

- Tyrowicz, Joanna, Lucas van der Velde, and Karolina Goraus. 2018. “How (Not) to Make Women Work?” Social Science Research 75:154–67. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2018.06.009

- VanderBrug, J. 2013. “The Global Rise of Female Entrepreneurs.” Harvard Business Review.

- Warren, T., K. Rowlingson, and C. Whyley. 2001. “Female Finances: Gender Wage Gaps and Gender Asset Gaps.” Work, Employment and Society 15 (3): 465–4. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170122119110

- Watts, J. H. 2009. “Leaders of Men: Women ‘Managing’ in Construction.” Work, Employment and Society 23 (3): 512–30. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0950017009337074

- Wedel, J. R. 2003. “Clans, Cliques and Captured States: Rethinking ‘Transition’ in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union.” Journal of International Development 15 (4): 427–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.994

- Welzel, C., P. Norris, and R. Inglehart. 2002. “Gender Equality and Democracy.” Comparative Sociology 1 (3–4): 321–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1163/156913302100418628

- Whittington, K. B., and L. Smith-Doer. 2005. “Women and Commercial Science: Women’s Patenting in the Life Sciences.” The Journal of Technology Transfer 30 (4): 355–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10961-005-2581-5

- Wilson, A. 2005. Virtual Politics: Faking Democracy in the Post-Soviet World. New Haven: Yale University Press.

- Withers, M. C., P. L. Drnevich, and L. Marino. 2011. “Doing More with Less: The Disordinal Implications of Firm Age for Leveraging Capabilities for Innovation Activity.” Journal of Small Business Management 49 (4): 515–36. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-627X.2011.00334.x

- Wu, Z., and J. H. Chua. 2012. “Second-order Gender Effects: The Case of US Small Business Borrowing Cost.” Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice 36 (3): 443–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6520.2012.00503.x

- Yurchak, A. 2013. Everything Was Forever, until It Was No More: The Last Soviet Generation. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Zhao, H., S. E. Seibert, and G. E. Hills. 2005. “The Mediating Role of Self-efficacy in the Development of Entrepreneurial Intentions.” Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (6): 1265–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1265

- Zou, Z., Y. Wu, Q. Zhu, and S. Yang. 2018. “Do Female Executives Prioritize Corporate Social Responsibility?” Emerging Markets Finance and Trade 54 (13): 2965–81. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1540496X.2018.1453355