?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

We use data from 131 countries in the period 2000–14 to analyze the determinants of urban primacy, calculated as the share of the city with the largest gross domestic product (GDP) in a country in the total GDP of that country. While prior research has largely neglected the role of financial factors, we demonstrate that urban primacy is related positively to the size of financial activity. In addition, currency depreciation in relation to the US dollar is related to lower urban primacy, while gross capital outflows are related to higher urban primacy. We find that trade openness—a key indicator of globalization—also coincides with higher urban primacy, but this relationship is statistically and economically less significant than that between finance and urban primacy. Among other factors, we show that urban primacy is smaller in countries with a large population, high population density, a large agricultural sector, and a federal political structure, and particularly high in countries where primate cities have seaport functions. Our main results hold in both developed and developing countries. We discuss a wide range of mechanisms through which finance can affect urban primacy, including agglomeration economies, proximity to power, access to capital, financialization, and financial instability. In short, finance has a crucial impact on the geographic distribution of economic activity.

Concentration of economic activity in large cities remains one of the most prominent features of the economic landscape. The number of megacities, with more than ten million inhabitants, has grown from seventeen in 2000 to thirty-three in 2018 (United Nations Citation2018). These and other large cities have become increasingly connected through flows of people, goods and services, capital, and ideas (Scott Citation2001). At the same time, the share of national population or income concentrated in the largest city, referred to as urban primacy, varies greatly from country to country. In Burundi, one of the smallest countries in Africa, the urban primacy in 2014, measured in terms of gross domestic product (GDP), was only 6.4 percent. In neighboring Rwanda, with similar total area and population, it was 37.2 percent (Source: Oxford Economics 2014).

High concentration and primacy have long been a concern of policy makers. Decisions to move capital cities away from the largest urban centers, numerous in history, serve as one obvious example. Many such decisions have been driven by military and political factors, but often they are also motivated by the objective of promoting a more spatially balanced economic development. Consider, for instance, the capital of Brazil moving from Rio de Janeiro to Brasilia in 1960 or that of Nigeria from Lagos to Abuja in 1991 (see Vesentini Citation1987; Abubakar Citation2014, respectively). Regional policies are other examples of redistributing tax revenues and other resources from central regions and large cities to peripheral areas, prevalent for instance in the EU. These are based on the assumption that not only trade but economic integration in general increase spatial inequality, which in turn need to be moderated by policy. As a World Bank report stated (World Bank Citation2008, 12), “The openness to trade and capital flows that makes markets more global also makes subnational disparities in income larger and persist for longer in today’s developing countries. Not all parts of a country are suited for accessing world markets, and coastal and economically dense places do better.” This quote reflects mainstream economic thinking that trade liberalization increases spatial inequality within countries, as it favors places with better access to international trade and finance.

Interest in spatial inequalities and urban concentration within countries has been amplified by recent political events. One of the most striking features of the US presidential election, and the UK–EU referendum of 2016, was that almost all large cities voted against Trump and against Brexit, respectively. A similar pattern can be found for votes against the National Rally (NR; formerly known as the National Front) in France, and the Law and Justice Party (L&J) in Poland. Proponents of Trump, Brexit, the NR, the L&J, and numerous equivalents around the world, often describe themselves or are described by others as antiglobalists. Rajan (Citation2019) suggests that the rise of these parties and movements represents a backlash against globalization, and is a result of changing interactions among markets, the state, and civil society. According to Rajan, the rise of the markets in recent decades has been accompanied by the rise of the state, with most benefits concentrated in flourishing central hubs of markets and governments (read large cities), leaving the periphery behind. Arguably growing international connections among these hubs add to the perceptions that the latter hoard the benefits of economic development in the conditions of globalization.

Finance is rarely considered in studies on urban concentration, and largely ignored in the literature on Zipf’s law trying to explain the relationship between the ranking of cities and their size (see, e.g., Gabaix Citation1999).Footnote1 This is striking for many reasons. Primate cities are almost always the leading financial centers of their countries, with finance being one of the reasons why they become primate cities in the first place. Second, finance is a major area and force of globalization. The recent rise in antiglobalist views, discussed by Rajan (Citation2019) among others, can be seen as a legacy of the global financial crisis, which emanated from leading financial centers (Wójcik Citation2013). Available evidence suggests that large cities hosting international financial centers, such as London and New York, recovered from the crisis more quickly and strongly than other areas (Martin Citation2011; Wójcik and MacDonald-Korth Citation2015). As such, both in a domestic and international context, finance is a major factor shaping the spatial distribution of economic activity, and consequently it is reasonable to expect that it also influences urban concentration.

To address this gap, the goal of this article is to extend the literature on factors affecting urban concentration by taking finance seriously in addition to trade, political, and other factors considered in prior research. Specifically, we analyze the determinants of urban primacy in 131 developed and developing economies in the period 2000–14. To capture the role of finance, we use a variety of measures of financial activity within countries, as well as data on cross-border financial interactions, in addition to an array of variables related to trade. Our key results show that after controlling for other factors, both trade openness and financial activity, measured with the ratio of credit or financial assets to GDP, are associated strongly with higher levels of urban primacy. These results hold in both developing and developed countries and are robust to a variety of model and variable specifications. Importantly, the relationship between financial activity and urban primacy is stronger than that found between trade openness and urban primacy, even though prior research has focused on trade and largely ignored finance. In addition, we find a positive relationship between gross capital outflows (i.e., the importance of a country as an international investor) and urban primacy, and a negative one between the latter and currency depreciation in relation to the US dollar (USD).

The following section elaborates on the particular ways in which finance may affect urban concentration. Next, we explain the data and methodology, while the section after presents and discusses our core results and accompanying robustness tests. The final section concludes, reflecting on the implications of our findings and directions for future research.

Urban Concentration and Finance

Theoretical literature on the drivers of urban concentration focuses on trade. Within research on urban systems, according to Henderson’s model (Citation1982), trade liberalization would increase concentration in capital-abundant and decrease it in labor-abundant countries. This literature also stresses that “the impact of trade is situation-specific, depending on the precise geography of the country” (Henderson Citation1996, 33). Most importantly, trade opening would favor cities with better access to foreign markets such as port or border cities (Rauch Citation1991).Footnote2 In New Economic Geography models, the effect of trade depends on the interplay between the forces of agglomeration and dispersion. As both are expected to fall with trade openness, the outcome is conditional on how quickly one falls in relation to the other. If the intensity of agglomeration falls faster than that of dispersion (e.g., due to high congestion costs), dispersion takes place (Krugman and Livas Elizondo Citation1996; Behrens et al. Citation2007). If the intensity of dispersion falls faster, trade liberalization induces agglomeration (Rauch Citation1991; Paluzie Citation2001). As Brülhart (Citation2011) concludes his review of relevant literature, “whether trade liberalization favors overall intra-national concentration or dispersion depends on possibly quite subtle, in general equally tenable, modelling choices.” The results of empirical research are mixed. The most influential cross-country study on the topic (Ades and Glaeser Citation1995) shows a negative relationship between trade openness and population primacy but argues that the relationship is not causal and can work in both directions. Within-country studies also yield mixed results, with articles showing either growing concentration or dispersion associated with trade liberalization (Brülhart Citation2011).

Literature on political factors affecting urban concentration seems to bring more conclusive results than those on trade. Ades and Glaeser (Citation1995, 198) claim that “politics affects urban concentration because spatial proximity to power increases political influence.” More specifically, they explain that

Urban giants ultimately stem from the concentration of power in the hands of a small cadre of agents living in the capital. This power allows the leaders to extract wealth out of the hinterland and distribute it in the capital. Migrants come to the city because of the demand created by the concentration of wealth, the desire to influence the leadership, the transfers given by the leadership to quell local unrest, and the safety of the capital. This pattern was true in Rome, 50 B.C.E., and it is still true in many countries today. (Ades and Glaeser Citation1995, 224)

Davis and Henderson (Citation2003), in a global study, extend this strand of research demonstrating that population primacy is negatively related to democracy, federalism, ethnolinguistic fractionalization, centrally planned economy, and the development of infrastructure connecting different parts of the country. They also show that primacy increases when the primate city is the capital. Anthony’s (Citation2014) cross-sectional study adds further evidence in this regard, showing that democratization as well as communist history moderate urban primacy, as they can improve regional representation in a country.

Considering the significance of urban concentration and finance, studies relating these two phenomena are scarce. On the theoretical side, within the urban systems strand of research, Henderson (Citation1982) treats finance as input to production alongside labor. As cities with larger a capital–labor ratio are larger than those with a lower ratio in this model, trade liberalization leads to a shift of economic activity from smaller to larger cities in countries with a high capital–labor ratio, and a shift from larger to smaller cities in those with a low ratio. To the best of our knowledge however, more recent theoretical models of urban systems have not considered finance explicitly, and the role of capital in Henderson’s model has not been tested empirically. The New Economic Geography models have not explicitly considered the role of finance either. As Lee and Luca (Citation2019) remark, this is surprising, given that already Williamson (Citation1965), in his work on the dynamics of spatial agglomeration, indicates the possibility of perverse capital flows from poor regions, with underdeveloped capital markets and high-risk premiums to rich regions with mature capital markets and low-risk premiums.

Empirical studies offer some evidence on the link between finance and urban concentration. In a case study of Mexico, Hanson (Citation1997) suggests that the relocation of Mexican industry from Mexico City to the northern regions was affected as much by liberalization of trade as by foreign capital inflows from the US. In the case of Indonesia, however, Henderson and Kuncoro (Citation1996) describe how the concentration of capital markets and the banking sector in the capital Jakarta contributed to the concentration of manufacturing. According to Sjöberg and Sjöholm (Citation2004) the position of Jakarta has been consolidated with the liberalization of trade, including rules on foreign investment and ownership. Investigating the entry of US firms into Ireland, Barry, Görg, and Strobl (Citation2003) show that inward foreign direct investment (FDI) is subject to strong agglomeration economies. In a cross-country analysis, Kandogan (Citation2014) finds that liberalization of investment, measured with a ratio of FDI inflows to GDP, is positively related to the concentration of GDP. Kandogan argues that foreign firms investing in a country tend to locate in existing economic centers, as this is where they can take advantage of market knowledge, economies of scale and scope, as well as economies of agglomeration. In another cross-country study, Gozgor and Kablamaci (Citation2015) show a positive relationship between economic globalization and population primacy. The former is defined as an aggregate measure that includes trade but also FDI, portfolio investment, income payments to foreign nationals, hidden import barriers, tariffs, and capital account restrictions. While the balance of evidence would appear to be on the side of a positive relationship between financial globalization and urban concentration, in a cross-country study focusing on political factors, Anthony (Citation2014) finds no significance of FDI inflows for urban primacy, and Poelhekke and van der Ploeg (Citation2009) suggest that high urban concentration actually reduces FDI inflows.

While these studies cover some aspects of finance, they do not consider the size of financial activity as a potential factor affecting urban concentration. The first feature of finance that we would focus on in this regard are strong localization and urbanization economies present in the financial sector. Financial firms, including banks, insurance firms, and asset managers, tend to locate close to each other in order to share information, financial infrastructure (for payments and trading, see, e.g. Agnes Citation2000), and labor market (Clark Citation2002; Urban Citation2019). As Krugman (Citation1996, 404) puts it “a banking center might do best if it contains practically all of a nation’s financial business.” Financial firms often collaborate with each other and other business (including professional) services on large transactions. Initial public offerings, through which firms raise capital, for example, typically involve groups (called syndicates) of investment banks, corporate law firms, audit and other consulting firms (Wójcik Citation2011). Together with other business services, financial firms tend to concentrate in large cities, where they can benefit from better access to nonfinancial firms as their customers, and share with the latter a large and deep labor market, infrastructure (e.g., communication), and big-city amenities (Cook et al. Citation2007). Financial firms also benefit from proximity to political power, including central governments and regulatory agencies and vice versa (Marshall et al. Citation2012).

As a result of strong localization and urbanization (considered jointly as agglomeration) economies in the financial sector, in an absolute majority of countries, the largest urban economy of the country is its largest financial center, and typically also the political capital. Henderson and Kriticos (Citation2018) show that employment shares of the financial sector (and other business services as well) fall consistently as one moves from primate, through secondary, tertiary, and smaller cities in Africa. Exceptions from the rule that the largest urban economy equals the largest financial center are indeed hard to find and can only be explained by extraordinary factors. In Germany, for example, Berlin, its largest urban economy, was its financial capital until the city was divided between two countries in the wake of WWII (Cassis Citation2010). When the largest urban economy in a country changes, the largest financial center tends to move as well. This is exemplified by twentieth-century shifts from Montreal to Toronto in Canada, Rio de Janeiro to São Paulo in Brazil, and Melbourne to Sydney in Australia (Porteous Citation1995).

Agglomeration economies, combined with the role of proximity to power, suggest a positive relationship between the size of financial activity in a country and urban primacy. This relationship, however, may depend on the level of economic development. Following New Economic Geography, Grote (Citation2008) theorizes an inverted-U shape relationship, whereby an increase in the geographic concentration of the financial sector accompanying declining transaction costs is followed by geographic dispersion as these costs continue to decline to very low levels. His research suggests that Germany exhibits this pattern, with concentration in Frankfurt increasing since the 1950s and decreasing slightly since the mid-1980s (see also Engelen and Grote Citation2009). For less developed countries, Aroca and Atienza (Citation2016) show that concentration of financial activity in primate cities in Latin American countries is not only very high but has actually grown between 1990 and 2010, while Contel and Wójcik (Citation2019) demonstrate growing concentration in São Paulo for Brazil. Considering the above theory and empirical evidence, we might expect the relationship between the size of financial activity and urban primacy to be weaker for developed economies. We have to ask ourselves, however, which types of financial activity disperse and which do not. Some labor-intensive financial services (typically back-office activities) can leave the largest financial centers, leading to dispersion of employment, but not necessarily that of GDP created in the financial sector. Wójcik (Citation2012), for example, indicates that, as financial activity and the sector grew in the US between 1978 and 2008; while some basic employment left New York City, the latter’s role as the hub of high finance, with the securities industry (investment banking and asset management) in the lead, has increased.

Primate cities acting as the largest financial centers typically act as the leading (and often the only truly) international financial centers of their countries in both developed and developing economies. As such, they function as hubs of cross-border financial activity, including payments, lending, equity raising, and advisory services, generating jobs and incomes (Wójcik and Burger Citation2011). For this reason, we would expect urban primacy to be related positively to financial openness of a country. In this regard, it is worth recalling the findings of Brülhart (Citation2006) showing that the EU accession, which involves both economic and financial integration, has favored central regions in terms of service employment, with jobs in banking and insurance in the lead.

The next factor to consider for analyzing the relationship between urban concentration and finance is access of households and nonfinancial firms to funding, whether in the form of equity or credit. Financial and economic geographers have demonstrated that access to finance is uneven across space (Klagge and Martin Citation2005). A study of almost a hundred countries shows that firms in large cities (over one million inhabitants) are less likely to perceive access to capital as a constraint (Lee and Luca Citation2019). The authors list a long number of reasons that can explain privileged access to capital in large cities, including lower transaction costs combined with lesser agency problems, enabled by tacit knowledge and face-to-face contact; higher level of competition among local capital providers; more abundant and valuable real estate that can serve as collateral; banks mimicking each other in lending to borrowers from large cities; lower risk of lending associated with large cities and therefore lower liquidity preference of banks in large cities, potentially combined with transfer of deposits from periphery to large cities (Dow Citation1987); and finally, connections of large cities with other parts of the world. This research suggests a two-way relationship between urban primacy and the size of financial activity. The bigger the part of a country’s economy that is contained within its primate city, the easier it is for an average potential borrower in this economy to access finance, and hence the bigger the size of the financial activity in the country (and the amount of credit in particular). The bigger the financial activity in the primate city, in turn, the more incentives for households (including potential entrepreneurs seeking capital) and nonfinancial firms to locate in the primate city. Financial openness could contribute to this mechanism, since it would allow primate cities, as leading international financial centers in an economy, to access capital abroad.

Importantly, the large city bias in access to capital seems to depend on the level of economic development. As Lee and Luca (Citation2019) demonstrate, the bias declines as countries develop. In related research, Wójcik (Citation2011) shows that financial center bias in stock markets is particularly strong in countries with underdeveloped stock markets. These findings constitute another reason why we may expect a weaker relationship between the size of financial activity and urban primacy in developed economies. Further evidence to make such a hypothesis plausible comes from research on the finance and growth nexus. The more traditional literature on the topic stresses a positive relationship between the level of financial activity (typically referred to as financial development) and economic growth (see Levine Citation2005 for a review), which to a large extent rests on the understanding that more finance implies better access of economic actors to capital as a resource. More recent literature, however, points to an inverted-U shape relationship, whereby very high levels of financial activity may have adverse impacts on growth (e.g., Cecchetti and Kharroubi Citation2012). While finance and growth research focuses almost exclusively on country-level analysis, Ioannou and Wójcik (Citation2021) corroborate the existence of an inverted-U shape relationship between growth and finance at both the country and city level. This indicates that as financial activity grows and its positive impacts on economic growth fades away, the impact of financial activity on urban primacy may be weaker in countries with larger (more developed) financial systems.

Another factor to consider, and one related to the notion that excessive financial activity harms economic development, is financialization, which can be defined as the “increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economy” (Epstein Citation2005, 3). As such, financialization results in larger dependence of nonfinancial firms, as well as the household and public sector, on finance, and hence on proximity to the providers of financial services with their concomitant labor markets and infrastructures (Engelen and Faulconbridge Citation2009). For example, in more financialized economies, nonfinancial firms and the public sector would employ more people with financial expertise. Consider the case of Boeing, which moved its headquarters from Seattle to Chicago in 2000, arguing that this relocation would help the company create shareholder value—a central component of financialization (Muellerleile Citation2009). The size of financial activity would be a reflection of financialization, which offers another reason to expect larger concentration of economic activity in primate cities as leading financial centers. Financial integration and openness could facilitate the spread of financialization internationally. One particular form this could take is through the proliferation of policies that promote the development of large cities as international financial centers in both developed and developing economies (Engelen and Glasmacher Citation2013; Hoyler, Parnreiter, and Watson Citation2018). The UK can serve here as an example of an economy, where financialization, accompanied by financial deregulation (including demutualization of the banking sector), has over a long period of time contributed to the primacy of London (Leyshon, French, and Signoretta Citation2008).

Finally, we should reflect on the role of financial instability. Literature suggests that real estate bubbles tend to concentrate in large cities, where nonlocal (domestic and foreign) demand for real estate (often treated purely as financial investment rather than for its use) is particularly high (Shiller Citation2008; Martin Citation2011). Real estate bubbles, typically fueled with debt, in turn generate jobs and income in the financial sector, construction industry, and across the broader urban economy. Hence, the size of financial activity, and the amount of credit in particular, may have a positive impact on urban primacy. Financial globalization, by facilitating real estate purchases by foreign investors could reinforce urban primacy as well. The logic of real estate bubbles, and their concentration in large cities, may apply to bubbles in other asset markets. Of course, bubbles in large cities ultimately burst. However, literature on the recent global financial crisis, for example, suggests that leading financial centers tend to avoid the worst effects of the crisis, an observation related to power concentrated in such cities (Martin Citation2011). For example, Wójcik and MacDonald-Korth (Citation2015) demonstrate that the global financial crisis has led to a major reduction in financial sector employment in secondary and particularly tertiary cities in the UK, while London recovered from the crisis very quickly.

Put together, factors to do with agglomeration and proximity to power, access to capital, financialization, and financial instability are reasons why we expect a positive relationship between the size of financial activity in a country and urban primacy but also between the latter and financial globalization. The following section elaborates on the particular econometric method and data we use in our analysis.

Data and Methodology

Our core data comes from the World Development Indicators (WDI), the Penn World Table (PWT), the World Bank Financial Structure Database (WBFSD), and the International Financial Statistics (IFS) database of the International Monetary Fund (IMF) (see, respectively, Čihák et al. Citation2012; Feenstra, Inklaar, and Timmer Citation2015; IMF Citation2018; World Bank Citation2018). To construct all primacy ratios, we use Oxford Economics (or OE), a proprietary database offering demographic, sectoral, and macroeconomic data at the level of cities. The database defines cities on the basis of urban agglomerations and metropolitan areas, incorporating the built-up areas outside the historic and administrative core of each city (Oxford Economics Citation2014).

Our panel consists of 131 developing and developed economies, and covers the period 2000–14. The basic criterion for selecting the countries and time span of our sample is the common availability of data from all of the aforementioned data sources. With respect to time, the main limitation is the lack of data in Oxford Economics for the years before 2000. Geographically, we had to exclude very small countries and city-states, defined here as countries for which Oxford Economics does not distinguish between the largest city and country data (e.g., Luxembourg and Singapore). The full list of countries covered is available in Appendix A.

A common approach in urban studies is to consider data in five-year averages (e.g., Davis and Henderson Citation2003; Frick and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018), since this helps focus on the medium- to long-term patterns and facilitates more accurate estimations, due to the removal of short-term noise. We follow a similar logic but utilize three-year instead of five-year averages for two reasons. First, the relatively short time span of our panel means that if we were to construct five-year averages we would be left with only three time observations per country. This would compromise our capacity to conduct a meaningful cross-time analysis as well as our ability to use time lags in regressions. An additional advantage of the three-year average formatting is that it allows a better balance between the removal of noise and the exploitation of available information. Having said this, for robustness, we also report our key findings for models using five-year averages.

The basic econometric model of our analysis is as follows:

where i and t are the subscripts for countries and time, respectively; denotes urban primacy;

is our proxy for the size of financial activity;

indicates the variable used for capturing globalization;

is a vector including all other time-varying variables; and

is a vector of time-invariant regressors. Additionally,

and

stand for the corresponding parameter values;

describes the country-specific effect; and

stands for the random error of our specification. To tackle simultaneous endogeneity, all time-varying regressors are lagged by one time period. In the section before the conclusion we present an additional exercise with instrumental variables so as to further protect our results against endogeneity bias.

A typical issue in panel data econometrics is the choice between fixed and random effects. While the random effects estimation is more efficient than fixed effects, the latter is consistent, even in the presence of correlation between the country effect and the regressors of the model, and hence often preferred (for discussion, see, e.g., Baum Citation2006). The use of fixed effects, however, prevents one from considering time-invariant characteristics. To solve the conundrum, while preserving the space for time-invariant regressors in our model, we opt for the modified-random effects method, put forward by Mundlak (Citation1978) and Hajivassiliou (Citation2011). The goal of this method is to give a precise expression to the country-specific effect . To achieve it, Mundlak and Hajivassiliou propose to use the full-time average values of all the time-varying variables of the model as additional regressors. With this modification, the random effects and fixed effects models yield identical results. As discussed in Mundlak (Citation1978), the estimator is essentially the same, so that the actual choice is not whether to assume randomness in the country-specific effect or not, but rather how to model it.

On the basis of our model, the modified-random effects approach implies the consideration of the following auxiliary expression:

where and

describe time-invariant parameters; the overarching bar stands for the full-time average of the variable(s) below it; and

describes an error that is now by definition uncorrelated with the regressors of the main model. Once the expression of Equationequation (2)

(2)

(2) is inserted in Equationequation (1)

(1)

(1) , a model is obtained, which can be estimated consistently using random effects. This is the model we use in our analysis.Footnote3

To demonstrate the merit of the modified-random effects method, and hence the robustness of our findings, we also report the fixed effects version of our main set of models at the end of the article (upper part of Appendix B).

For the main part of our analysis, urban primacy is defined as the GDP of the largest city in a country (in terms of GDP) divided by the GDP of that country. Stated formally,

where stands for GDP primacy;

and

describe the country and time indices as before; and

denotes the largest city of a country in GDP terms (based on average GDP for the whole 2000–14 period).Footnote4

Calculating primacy in this way is popular, but for us it is also a matter of necessity. The number of countries with data from five cities or more in Oxford Economics is merely thirty-two. For that reason, using alternative measures (see, e.g., Frick and Rodríguez-Pose Citation2018 for a list), such as the 1–4 primacy ratio, Herfindahl-Hirschman Index, or Zipf’s law-based measures, would not give us a country sample that allows a meaningful econometric analysis.Footnote5

To assess the strength of results, we repeat our main regressions for an alternative specification of the dependent variable, wherein the gross value added (GVA) of financial and advanced business services (FABS) is subtracted from GDP before the calculation of the primacy ratio. This way we test whether the impact of finance and globalization is not driven by the location of financial and business services firms themselves. Put differently, this allows us to test the influence of finance on sectors beyond those closely related to finance.Footnote6

Another test we conduct is to rerun our main model using a population primacy ratio as the dependent variable. This is calculated using Equationequation (3)(3)

(3) , with population replacing GDP. This test facilitates comparisons with literature focused on population primacy (e.g., Ades and Glaeser Citation1995; Moomaw and Alwosabi Citation2004; Behrens and Bala Citation2013; Anthony Citation2014). While GDP primacy and population primacy are different analytical categories, they are closely related, as denoted by the correlation of 91 percent (see ).

Table 1 Summary Statistics

Table 2 Correlation Matrix

For measuring the size of financial activity at the country level, we use the total stock of credit provided by domestic banks and other financial institutions. Although not without weaknesses (e.g., the omission of fee-based financial activities), this is a most commonly employed metric in macroeconomic research (see, e.g., Cecchetti and Kharroubi Citation2012). To safeguard our results, we also run our model with three alternative proxies (each as a ratio of GDP): credit granted by banks only; total stock of assets of banks and other financial institutions; and the sum of credit and market capitalization of domestic equity and bond markets. As such, we test a wide range of measures, from the narrowest to the broadest possible.

Following Jaumotte, Lall, and Papageorgiou (Citation2013), we draw an analytical distinction between trade globalization and financial globalization. Our baseline variable for trade globalization is trade openness, measured as the sum of exports and imports, divided by GDP. Two alternative variables tested are the trade balance of a country (exports minus imports), and the value of domestic currency against the USD. We suspect that the depreciation or appreciation of the domestic currency might be significant in shaping urban concentration due to its capacity to affect the sectoral composition of the economy. Consider for instance a scenario where a medium- to long-run currency depreciation comes to benefit export sectors, such as tourism, which may be concentrated outside the largest cities. Due to its direct impacts on the terms of trade, we classify currency appreciation as a variable of trade globalization, while it could also be considered within the realm of financial globalization. For capturing de jure trade globalization, we employ the mean tariff rate of a country.

We test six different measures of financial globalization, starting with net FDI inflows. Anthony (Citation2014) employs this variable, based on the hypothesis that inward FDI might be forcing the organization of production in a small number of urban areas, thereby fostering concentration. Second, we test the impact of non-FDI capital flows. These refer to more short-term cross-border flows, including secondary market trading of equity and debt securities, money market instruments, and financial derivatives. Third, we consider the net balance of the overall financial account of a country (with FDI and non-FDI flows combined). Finally, we test the significance of gross capital inflows and outflows as well as their sum. The latter can be seen as a proxy of financial openness, similar in its construction to the aforementioned variable of trade openness. By considering gross flows we expose a country’s financial interconnectedness with the rest of the world, which would be lost if we only used data from net flows (for a similar discussion, see Forbes and Warnock Citation2012). As with the rest of our analysis, all capital flow variables are considered in three-year averages.

Vector contains all other time-varying regressors in our model. The variables tested for significance include the share of value added outside agriculture, government expenditure, life expectancy, age dependency, total rents from natural resources, and income from tourism. Furthermore, we include a dummy for capturing episodes of banking crises, based on the data provided in of Laeven and Valencia (Citation2018).

Vector consists of variables used in a time-invariant form, including population density, total population, average GDP per capita (as a proxy for the level of economic development), access to electricity, number of automated teller machines (ATMs), road density, and the size of the rail network.Footnote7

Following Frick and Rodríguez-Pose (Citation2018) we consider a proxy for state history, taken from the State Antiquity Index database of Putterman and Bockstette.Footnote8

In line with Nitsch (Citation2006) we consider a seaport dummy. Finally, we also examine the impact of political variables, including a dummy for countries with a federal government, the Gastil indices on political rights and civil liberties, as well as an indicator for political stability (Ades and Glaeser Citation1995; Davis and Henderson Citation2003).

Results

and present the summary statistics and correlation pairs for all variables utilized in the main part of our econometric analysis. In terms of average values for the period 2000–14, countries with the highest urban primacy include Israel (54.1 percent), Iceland (65.7 percent), Mongolia (66.8 percent), and Djibouti (77.5 percent). On the other extreme, we find India (3.9 percent), China (4.2 percent), Burundi (5.6 percent), and Germany (6.7 percent). The UK is close to the mean value of concentration, 30.5 percent for the period examined, while the US has a primacy ratio of 9.2 percent.

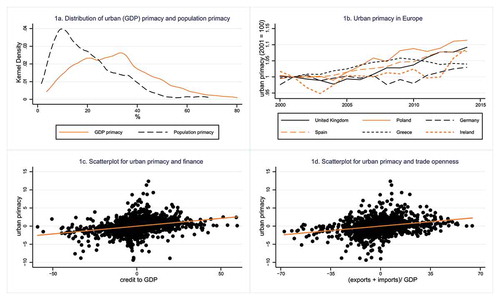

illustrates some key stylized facts. shows that urban primacy (as measured by GDP primacy) tends to be substantially higher than population primacy. displays the rise in urban primacy from 2000 to 2014 for a selection of European economies. and depict the positive association between urban primacy and two of our key variables: credit to GDP and trade openness.

Figure 1. Selected stylized facts

presents core results. Columns 1 and 2 introduce finance and trade openness separately from one another, while column 3 considers them jointly in what can be seen as our baseline specification. Our default proxy for the size of financial activity, credit to GDP, is significant at the 1 percent level, with a parameter value of 0.027. Ceteris paribus, were a country’s credit to GDP and urban primacy ratios similar to that of France (94.8 percent and 30.83 percent, respectively, in 2014), a 25 percent increase in the size of financial activity would be associated with a 2 percent increase in urban primacy. Trade openness is significant at the 5 percent level and also positively related to concentration, albeit with a lower parameter value than credit.

Table 3 Baseline Econometric Analysis

Furthermore, the share of value added outside agriculture is positively related to concentration. As economic activity moves away from agriculture, urban primacy rises, in line with the results of Ades and Glaeser (Citation1995). Episodes of banking crises also emerge with a negative coefficient, with statistical significance close to 10 percent.

Among the time-invariant characteristics, population density is significant and negative, in line with Anthony (Citation2014). Total population is also highly significant and, as expected, inversely related to urban primacy. GDP per capita, our proxy for economic development, appears with a negative relationship to urban primacy. This is similar to the result obtained by Moomaw and Shatter (Citation1996). The seaport dummy comes out with a positive and significant coefficient, confirming that being a seaport offers major growth opportunities for cities. Finally, the federal dummy comes with a negative coefficient, suggesting that countries with federal governments tend to exhibit a lower degree of economic centralization, as expected based on literature (Davis and Henderson Citation2003). All other time-invariant variables discussed at the end of the previous section but not included in were found to be insignificant (their summary statistics are available in Appendix A).

Models 4 to 6 of introduce alternative proxies for the size of financial activity: first the narrower version of credit, wherein only credit provided by banking institutions is considered; second, the total stock of assets held by all financial institutions in a country; and third a broader variable, considering the sum of credit, equity, and bond markets. In the first two cases results remain highly consistent with model 3, with minor differences in the value of the coefficients obtained. In the third model, results remain significant for the broader financial sector variable but weaken for trade openness and most of our controls. This could be explained partly by the smaller sample size, due to considerable gaps in the data from stock and bond markets.

Among alternative measures of trade and financial globalization, the value of the domestic currency of a country against the USD, and the volume of gross capital outflows, turn out to be statistically significant in our regressions (columns 8 and 9).Footnote9 The significance and negative sign of the value of domestic currency tells us that, ceteris paribus, the persistent depreciation of a country’s domestic currency is related to reduced urban primacy. This may be due to the positive effects of currency depreciation on export sectors, such as tourism and agriculture, boosting economic growth outside of the primate city. Furthermore, the significance and positive sign of gross capital outflows indicate that the greater the role of a country as an international investor (in relation to its GDP), the more concentrated its economic activity—regardless of the positioning of the country as a destination for investment.

The insignificance of de jure trade globalization, captured here by the mean tariff rate of a country (column 7), is in line with Nitsch (Citation2006). Additionally, the insignificance of trade balance suggests that while the overall openness, that is, exports plus imports, is significant in its relationship to urban primacy, the precise positioning of an economy as either in a trade surplus or deficit does not carry a separate explanatory force. Net capital flow positions are also insignificant, both for direct and portfolio investment (FDI and non-FDI). Perhaps surprisingly, gross capital inflows and aggregate financial openness (absolute sum of gross capital inflows and outflows) also turn out to be insignificant, indicating an asymmetry in the ways international investment may affect urban primacy. While exports of capital to the rest of the world seem to foster urban concentration, imports do not.

Columns 10 to 12 of the table report our most important specifications so far (models 3, 8, and 9), using time effects (each corresponding to a three-year period, in line with the format of the panel). As shown, all key variables remain statistically and economically significant, except for some decline in the statistical significance of trade openness. In their vast majority, control variables also remain highly similar to what was reported in previous models.

In the last part of we rerun our baseline model 3 separately for developed and developing economies (using OECD membership as a proxy for distinguishing between the two), to test whether our findings are driven by a particular group of countries. Financial activity and trade openness remain significant and positive for both groups, with slightly higher parameter values for developing economies. As for the rest of the results, economic activity outside agriculture remains significant only for developing economies, while GDP per capita is only significant for developed economies. Total population has a strongly negative coefficient in both groups, whereas the crisis dummy remains significant at a 10 percent level only for developed countries. The port dummy, on the other hand, seems to be more important in the developing world. It appears that the economic boost that being a port city provides is particularly relevant at relatively low levels of economic development. Overall, this part of our analysis indicates that while the relationship between finance and urban primacy applies to both developed and developing countries, it may indeed be stronger in the latter group, as hypothesized tentatively in our literature review.

To complete the analysis of our core results, the upper part of Appendix B replicates , with all the aforementioned models run with fixed effects. As shown, parameter values are highly similar for all pairs of models. In the fixed effects version of model 3, for example, both finance and trade openness maintain identical parameters (0.027 and 0.015, respectively). Moreover, the Hausman test results allow us not to reject the null hypothesis of no systematic difference between the two estimators.Footnote10 Overall, these findings confirm the consistency of the modified-random effects approach, as originally demonstrated by Mundlak (Citation1978).

In we repeat the main models (3, 8, and 9) with a number of alterations. First, we see how our results behave when we use five-year instead of three-year averages (here we also report the equivalents of models 1 and 2). Second, we repeat our three-year average regressions but with an alternative specification of the left-hand side variable—one that captures GDP concentration after excluding the GVA of FABS (labeled as “non-FABS urban primacy ratio”). Third, we run the same models with population primacy as the dependent variable.

Table 4 Tests of Robustness

To start with five-year averages, shows that our results are very much in line with those in , despite some loss of statistical significance on some occasions (mainly due to the smaller size of our sample). Coefficients for credit to GDP and trade openness remain positive and significant when considered separately, and both are close to the 10 percent level of significance when considered jointly. Coefficients for economic activity outside agriculture and the port dummy remain significant and positive, while those for total population, population density, and the federal dummy are negative. Furthermore, coefficients for the currency and gross capital outflow variables remain negative and positive respectively, both highly significant.

Columns 6 to 8 confirm the validity of our baseline results for urban primacy net of the GVA of FABS, notwithstanding the partial loss of significance for the currency variable. Most importantly, models 6 and 8 confirm that the implications of finance and financial globalization for urban primacy cannot be attributed to the location of FABS themselves. Finance, as captured here with credit and gross financial outflows to GDP, is strongly related to economic concentration in primate cities, above and beyond its direct impact on the size of the financial sector and other related services. Finally, columns 9 to 11 show that, at least in part, the variables examined here, with credit to GDP and trade openness in the lead, remain relevant in explaining the concentration of population.

Identification and Causality

In our analysis so far, we have dealt with endogeneity by incorporating all time-varying regressors with a lag. While this is a helpful step for dealing with simultaneous endogeneity, it is insufficient if the regressors are not strictly exogenous. Our aim in this section is, therefore, to add a further layer of support to our key estimates to guard them against endogeneity bias. To this end we conduct an instrumental-variables exercise in which we use legal and institutional data as instruments for the size of financial activity, and data on ethno-linguistic and religious fractionalization as instruments for trade openness.

For instrumenting financial activity, we utilize the composite index of shareholders’ rights from La Porta et al. (Citation1998) and the World Bank’s index of political stability (Kaufmann, Kraay, and Mastruzzi Citation2010).Footnote11 We expect both variables to be reasonably exogenous to urban concentration, while also relevant in approximating financial activity. All else the same, for example, one would expect a politically stable environment to help build trust and thereby encourage the expansion of finance in a country. The use of legal and institutional variables as instruments for financial activity is well established in macroeconomic studies, particularly those investigating the impact of finance on economic growth (see Levine Citation1999, Citation2005; Levine, Loayza, and Beck Citation2000), though their use in economic growth regressions has also been criticized on the basis of being repeatedly employed for instrumenting a plethora of different variables (Bazzi and Clemens Citation2013).

For instrumenting trade openness, we use the rich data set on ethno-linguistic and religious heterogeneity from Kolo (Citation2012), covering over two hundred countries. Specifically, we utilize the levels terms of three indices on ethno-racial, linguistic, and religious dissimilarity, which together form the distance adjusted ethno-linguistic fractionalization index (DELF; see appendix C of Kolo Citation2012). Although we are unaware of any studies using these variables as instruments for trade openness before, their connection with socioeconomic outcomes is not new, since prior research has explored the impact of ethnic fragmentation on economic growth (Easterly and Levine Citation1997; Alesina et al. Citation2003), its association with the provision of public goods (Alesina, Baqir, and Easterly Citation1999), and links with the quality of governance (La Porta et al. Citation1999). Other studies have offered evidence that domestic heterogeneity—either de jure or de facto—might positively impact international trade. Daumal (Citation2008), for example, argues that countries with federal governments tend to record higher levels of international trade due to domestic market fragmentation (and thus high interregional trade costs) and/or due to political incentives associated with separatism, in addition to evidence of a positive connection between linguistic heterogeneity and trade openness. Bratti, De Benedictis, and Santoni (Citation2014), and Zhang (Citation2020) show that immigration to a country tends to increase trade with the country people migrate from. This can be due either to immigrants exhibiting a home bias in their consumption behavior or their potential to act as a cultural bridge between the two countries, thereby reducing mutual trading costs (Bratti, De Benedictis, and Santoni Citation2014).

Columns 12 to 14 of present the second-stage regression results of our instrumental variable models (first-stage results are also reported in the lower part of Appendix B). Like in our basic models (columns 1 to 3 in ), we instrument financial activity and trade openness separately and then jointly. As shown in , finance appears positive and significant at the 5 percent level. Our results also indicate that the null hypotheses of underindentification and weak identification can be rejected, while the p-value of the Hansen J test (0.0797) allows us not to reject the null hypothesis of instruments’ exogeneity with 95 percent confidence.Footnote12 As we would expect, shareholders’ rights and political stability are positive and statistically significant in the first-stage regression (bottom-left part of Appendix B).

In the case of trade openness, the instrumented version of the variable enters the second-stage regression with a positive sign and a statistical significance on the 10 percent borderline (t-statistic equals 1.615). The results for underidentification and weak identification support our instruments, while the Hansen J test returns a p-value of 0.8963.Footnote13 In the first-stage regression reported in Appendix B, the dissimilarity indices appear statistically significant but with mixed signs. Specifically, linguistic dissimilarity shows up positive, whereas ethnic and religious dissimilarity both exhibit negative signs. Finally, in the joint instrumentation model reported in column 14 of , the second-stage results for finance and trade openness remain broadly aligned with the previous two models.

Concluding Remarks

We used data from 131 countries in the period 2000–14 to examine the role of finance among other factors of urban primacy. To start with, our results offer an important confirmation of a number of findings from prior research. Economic concentration in primate cities is smaller in countries with a large population, high population density, a large agricultural sector, and a federal political structure. It is particularly high in countries where primate cities have port functions. In a key original contribution, we show that after controlling for a comprehensive range of factors, urban primacy is related positively to the size of financial activity. When analyzing various aspects of globalization, we find that trade openness coincides with higher urban concentration. This relationship, however, is economically and statistically less significant than that between finance and urban primacy. We also show that currency depreciation in relation to the USD is related to lower urban concentration, while gross capital outflows are related to higher urban concentration. Our findings are robust to different ways of averaging data over time and to the exclusion of the broadly defined financial sector from the calculation of the urban primacy ratio. Our core results hold when, in the calculation of urban primacy, GDP is replaced with population, and apply to both developed and developing countries, though particularly strongly in the latter group. Furthermore, finance and trade openness maintain their explanatory power even when proxied by instrumental variables.

Our findings are related most closely to those of Kandogan (Citation2014) and Gozgor and Kablamaci (Citation2015) who also show a positive relationship between urban concentration and various aspects of globalization. In contrast to Kandogan (Citation2014), however, we use a much wider range of variables and much more specific measures of globalization than the broad aggregate indices of globalization used by Gozgor and Kablamaci (Citation2015). To the best of our knowledge, ours is the first study to consider the size of financial activity as a factor affecting urban concentration. The statistical strength of our results demonstrates that this factor must not be ignored in research on the spatial concentration of economic activity.

The impact of financial sector size on urban concentration can be influenced by many factors. Agglomeration economies are particularly strong in the financial sector, with primate cities being typically the largest financial centers of their countries. In addition, as primate cities tend to be capital cities, they can also offer benefits of proximity between the financial and political power, further enhancing urban primacy. Second, access to capital in primate cities is likely to be better, attracting more financial firms and potential borrowers to the city. Third, financialization, as reflected by the size of financial activity, would make nonfinancial business and other economic sectors more dependent on finance, also contributing to urban primacy. Finally, primate cities represent concentrations of financial bubbles, typically fueled by credit, constituting yet another reason for a positive relationship between the magnitude of financial activity and primacy.

While this is the first article to analyze the relationship between the size of financial activity, globalization, and the spatial concentration of economic activity, we leave it to future research to test the contribution of the various channels that link finance with urban concentration. Our results on a slightly stronger relationship between finance and urban primacy in developing economies than in developed economies indicate that future endeavors in the area should take into account the literature on inverted-U shape patterns for geographic concentration of economic activity as well as for the finance and growth nexus. On the methodological front, considering the nature of financial center development, we believe that using a simple urban primacy ratio is appropriate, but if data allows, future studies should also test the relationship between finance and other measures of urban concentration. In any case, we hope that our results provide strong evidence that finance must be given a much more central place in research studying the distribution of economic activity.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the editor and three anonymous reviewers for useful remarks in earlier drafts of the article. We also want to thank the participants of the 1st Financial Geography (FinGeo) Global Conference (Beijing, 2019) for their feedback. The article has benefited from funding from the European Research Council (European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme; grant agreement No. 681337). The article reflects only the authors’ views, and the European Research Council is not responsible for any use that may be made of the information it contains.

Notes

1 Formally stated, Zipf’s law suggests that the second biggest city in a country is half the size of the biggest one, the third biggest city about a third of the size of the biggest one, and so on.

2 It is worth noting that the association of access to the sea with trade openness and the size of economic activity traces all the way back to chapter 3 of Adam Smith’s Wealth of Nations (Smith Citation[1776] 2008).

3 In themselves the full-time averages of the time-varying regressors are often insignificant, despite their usefulness in ensuring consistency. For this reason, and to save space, we utilize them but do not report them in the econometric tables below (a full set of results is available on request).

4 The number of the cities for which Oxford Economics has available date varies by country. For those countries for which data is available for only one city (e.g., Ireland), that city’s GDP comes to form the numerator in (3).

5 The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index measures concentration by considering the sum of the squared shares of the variable under consideration that is held by each city in a country.

6 FABS is the closest sectoral classification to finance that is available in Oxford Economics.

7 We also considered the first five variables in a time-varying form, which nevertheless turned out to be statistically insignificant (results available upon request).

8 Version 3.1. https://www.brown.edu/Departments/Economics/Faculty/Louis_Putterman/antiquity%20index.htm.

9 To save space we do not report the results of regressions in which globalization variables are insignificant, except for one with the tariff rate, which is included to serve as an indication. All other results are available upon request.

10 The Hausman test is typically used for testing whether the random effects estimator is consistent, in which case the estimated parameters should not be systemically different to the parameters estimated under fixed effects (Baum Citation2006).

11 We also experimented with a similar composite index for creditors’ rights, without, however, obtaining any significant results. A limitation of the La Porta et al. (Citation1998) data set is that it only covers forty-five countries. In the case of political stability, we consider its value for each country at the start of the period under consideration.

12 The Hansen J test’s null hypothesis is that the instruments are valid, that is, uncorrelated with the error term and correctly excluded from the estimated equation (Baum Citation2006).

13 In the test for weak identification, the F statistic obtained is equal to 19.454. Baum and Schaffer (Citation2007) suggest that as a rule of thumb F should be greater than ten for weak identification not to be considered a problem.

References

- Abubakar, I. R. 2014. Abuja city profile. Cities 41 (Pt. A): 81–91. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2014.05.008.

- Ades, A., and Glaeser, E. 1995. Trade and circuses: Explaining urban giants. Quarterly Journal of Economics 110 (1): 195–227. doi:10.2307/2118515.

- Agnes, P. 2000. The “end of geography” in financial services? Local embeddedness and territorialization in the interest rate swaps industry. Economic Geography 76 (4): 347–66. doi:10.2307/144391.

- Alesina, A., Baqir, R., and Easterly, W. 1999. Public goods and ethnic divisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (4): 1243–84. doi:10.1162/003355399556269.

- Alesina, A., Devleeschauwer, A., Easterly, W., Kurlat, S., and Wacziarg, R. 2003. Fractionalization. Journal of Economic Growth 8 (2): 155–94. doi:10.1023/A:1024471506938.

- Anthony, R. 2014. Bringing up the past: Political experience and the distribution of urban populations. Cities 37:33–46. doi:10.1016/j.cities.2013.11.005.

- Aroca, P., and Atienza, M. 2016. Spatial concentration in Latin America and the role of institutions. Journal of Regional Research 36:233–53.

- Barry, F., Görg, H., and Strobl, E. 2003. Foreign direct investment, agglomerations, and demonstration effects: An empirical investigation. Review of World Economics 139 (4): 583–600. doi:10.1007/BF02653105.

- Baum, C. 2006. An introduction to modern econometrics using stata. College Station, TX: Stata Press.

- Baum, C., and Schaffer, M. 2007. Enhanced routines for instrumental variables/generalized method of moments estimation and testing. Stata Journal 7 (4): 465–506. doi:10.1177/1536867X0800700402.

- Bazzi, S., and Clemens, M. 2013. Blunt instruments: Avoiding common pitfalls in identifying the causes of economic growth. American Economic Journal: Macroeconomics 5 (2): 152–86.

- Behrens, K., and Bala, A. P. 2013. Do rent-seeking and interregional transfers contribute to urban primacy in Sub-Saharan Africa? Papers in Regional Studies 92 (1): 163–95.

- Behrens, K., Gaigne, C., Ottaviano, G. I. P., and Thisse, J. F. 2007. Countries, regions and trade: On the welfare impacts of economic integration. European Economic Review 51 (5): 1277–301. doi:10.1016/j.euroecorev.2006.08.005.

- Bratti, M., De Benedictis, L., and Santoni, G. 2014. On the pro-trade effects of immigrants. Review of World Economics 150 (3): 557–94. doi:10.1007/s10290-014-0191-8.

- Brülhart, M. 2006. The fading attraction of central regions: An empirical note on core-periphery gradients in Western Europe. Spatial Economic Analysis 1 (2): 227–35. doi:10.1080/17421770601009866.

- Brülhart, M. 2011. The spatial effects of trade openness: A survey. Review of World Economics 147 (1): 59–83. doi:10.1007/s10290-010-0083-5.

- Cassis, Y. 2010. Capitals of capital: The rise and fall of international financial centres 1780–2009. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Cecchetti, S. G., and Kharroubi, E. 2012. Reassessing the impact of finance on growth. Working Paper 381. Basel, Switzerland: Bank for International Settlements. https://www.bis.org/publ/work381.pdf.

- Čihák, M., Demirgüç-Kunt, A., Feyen, E., and Levine, R. 2012. Benchmarking financial development around the world, World Bank Policy Research, Working Paper 6175. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/868131468326381955/Benchmarking-financial-systems-around-the-world.

- Clark, G. L. 2002. London in the European financial services industry: Locational advantage and product complementarities. Journal of Economic Geography 2 (4): 433–53. doi:10.1093/jeg/2.4.433.

- Contel, F., and Wójcik, D. 2019. Brazil’s financial centres in the twenty-first century: Hierarchy, specialization and concentration. Professional Geographer 71 (4): 681–91. doi:10.1080/00330124.2019.1578980.

- Cook, G. A., Pandit, N. R., Beaverstock, J. V., Taylor, P. J., and Pain, K. 2007. The role of location in knowledge creation and diffusion: Evidence of centripetal and centrifugal forces in the city of London financial services agglomeration. Environment and Planning A 39 (6): 1325–45. doi:10.1068/a37380.

- Daumal, M. 2008. Federalism, separatism and international trade. European Journal of Political Economy 24 (3): 675–87. doi:10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2008.06.007.

- Davis, J., and Henderson, V. 2003. Evidence on the political economy of the urbanization process. Journal of Urban Economics 53 (1): 98–125. doi:10.1016/S0094-1190(02)00504-1.

- Dow, S. C. 1987. The treatment of money in regional economics. Journal of Regional Science 27 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9787.1987.tb01141.x.

- Easterly, W., and Levine, R. 1997. Africa’s growth tragedy: Policies and ethnic divisions. Quarterly Journal of Economics 112 (4): 1203–50. doi:10.1162/003355300555466.

- Engelen, E., and Faulconbridge, J. 2009. Introduction: Financial geographies—The credit crisis as an opportunity to catch economic geography’s next boat? Journal of Economic Geography 9 (5): 587–95. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp037.

- Engelen, E., and Glasmacher, A. 2013. Multiple financial modernities. International financial centers, urban boosters and the internet as the site of negotiations. Regional Studies 47 (6): 850–67. doi:10.1080/00343404.2011.624510.

- Engelen, E., and Grote, M. H. 2009. Stock exchange virtualisation and the decline of second-tier financial centres—The cases of Amsterdam and Frankfurt. Journal of Economic Geography 9 (5): 679–96. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp027.

- Epstein, G. 2005. Introduction: Financialization and the world economy. Financialization and the world economy, ed. G. Epstein, 3–16. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Feenstra, R., Inklaar, R., and Timmer, M. 2015. The next generation of the Penn World Table. American Economic Review 105 (10): 3150–82. doi:10.1257/aer.20130954.

- Forbes, K., and Warnock, F. 2012. Capital flow waves: Surges, stops, flight and retrenchment. Journal of International Economics 88 (2): 235–51. doi:10.1016/j.jinteco.2012.03.006.

- Frick, S., and Rodríguez-Pose, A. 2018. Change in urban concentration and economic growth. World Development 105 (May): 156–70. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.12.034.

- Gabaix, X. 1999. Zipf’s law for cities: An explanation. Quarterly Journal of Economics 114 (3): 739–67. doi:10.1162/003355399556133.

- Gozgor, G., and Kablamaci, B. 2015. What happened to urbanization in the globalization era? An empirical examination for poor emerging countries. Annals of Regional Science 55:533–53.

- Grote, M. H. 2008. Foreign banks’ attraction to the financial centre Frankfurt—An inverted “U”-shaped relationship. Journal of Economic Geography 8 (2): 239–58. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbm042.

- Hajivassiliou, V. 2011. Estimation and specification testing of panel data models with non-ignorable persistent heterogeneity, contemporaneous and intertemporal simultaneity, and regime classification errors. Working Paper. London: London School of Economics. https://econ.lse.ac.uk/staff/vassilis/pub/papers/pdf/modifre-ldvendog-apr11.pdf.

- Hanson, G. H. 1997. Increasing returns, trade and the regional structure of wages. Economic Journal 107 (440): 113–33. doi:10.1111/1468-0297.00145.

- Henderson, J. V. 1982. Systems of cities in closed and open economies. Regional Science and Urban Economics 12 (3): 325–50. doi:10.1016/0166-0462(82)90022-9.

- Henderson, J. V. 1996. Ways to think about urban concentration: Neoclassical urban systems versus the new economic geography. International Regional Science Review 19 (1–2): 31–36. doi:10.1177/016001769601900203.

- Henderson, J. V. 2003. The urbanization process and economic growth: The so-what question. Journal of Economic Growth 8 (1): 47–71. doi:10.1023/A:1022860800744.

- Henderson, J. V., and Kriticos, S. 2018. The development of the African system of cities. Annual Review of Economics 10 (1): 287–314. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-080217-053207.

- Henderson, J. V., and Kuncoro, A. 1996. Industrial centralization in Indonesia. World Bank Economic Review 10 (3): 513–40. doi:10.1093/wber/10.3.513.

- Hoyler, M., Parnreiter, C., and Watson, A., eds 2018. Global city makers: Economic actors and practices in the world city network. London: Edward Elgar.

- International Monetary Fund. 2018. International financial statistics. https://data.imf.org/?sk=4C514D48-B6BA-49ED-8AB9-52B0C1A0179B.

- Ioannou, S., and Wójcik, D. 2021. Finance and growth nexus: An international analysis across cities. Urban Studies. 58 (1): 223–42. doi:10.1177/0042098019889244.

- Jaumotte, F., Lall, S., and Papageorgiou, C. 2013. Rising income inequality: Technology, or trade and financial globalization? IMF Economic Review 61 (2): 271–309. doi:10.1057/imfer.2013.7.

- Kandogan, Y. 2014. The effect of foreign trade and investment liberalization on spatial concentration of economic activity. International Business Review 23 (3): 648–59. doi:10.1016/j.ibusrev.2013.11.005.

- Kaufmann, D., Kraay, A., and Mastruzzi, M. 2010. The worldwide governance indicators: Methodology and analytical issues. Working Paper 5430. Washington, DC: World Bank. http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/630421468336563314/pdf/WPS5430.pdf.

- Klagge, B., and Martin, R. 2005. Decentralized versus centralized financial systems: Is there a case for local capital markets? Journal of Economic Geography 5 (4): 387–421. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbh071.

- Kolo, P. 2012. Measuring a new aspect of ethnicity—The appropriate diversity index. Discussion Paper 221. Goettingen, Germany: Ibero America Institute for Economic Research.

- Krugman, P. 1996. Confronting the mystery of urban hierarchy. Journal of the Japanese and International Economies 10 (4): 399–418. doi:10.1006/jjie.1996.0023.

- Krugman, P., and Livas Elizondo, R. 1996. Trade policy and the third world metropolis. Journal of Development Economics 49 (1): 137–50. doi:10.1016/0304-3878(95)00055-0.

- La Porta, R., Lopez‐de‐Silanes, F., Shleifer, A., and Vishny, R. W. 1998. Law and finance. Journal of Political Economy 106 (6): 1113–55. doi:10.1086/250042.

- Vishny, R. W. 1999. The quality of government. Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 15 (1): 222–79. doi:10.1093/jleo/15.1.222.

- Laeven, L., and Valencia, F. 2018. Systemic banking crises revisited. Working Paper WP/18/206. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund. https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/WP/Issues/2018/09/14/Systemic-Banking-Crises-Revisited-46232.

- Lee, N., and Luca, D. 2019. The big-city bias in access to finance: Evidence from firm perceptions in almost 100 countries. Journal of Economic Geography 19 (1): 199–224.

- Levine, R. 1999. Law, finance, and economic growth. Journal of Financial Intermediation 8 (1–2): 8–35. doi:10.1006/jfin.1998.0255.

- Levine, R. 2005. Finance and growth: Theory and evidence. In Handbook of economic growth, Vol. ume 1A, ed. P. Aghion and S. Durlauf, 865–923. London: Elsevier.

- Levine, R., Loayza, N., and Beck, T. 2000. Financial intermediation and growth: Causality and causes. Journal of Monetary Economics 46 (1): 31–77. doi:10.1016/S0304-3932(00)00017-9.

- Leyshon, A., French, S., and Signoretta, P. 2008. Financial exclusion and the geography of bank and building society branch closure in Britain. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 33 (4): 447–65. doi:10.1111/j.1475-5661.2008.00323.x.

- Marshall, J. N., Pike, A., Pollard, J. S., Tomaney, J., Dawley, S., and Gray, J. 2012. Placing the run on northern rock. Journal of Economic Geography 12 (1): 157–81. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbq055.

- Martin, R. 2011. The local geographies of the financial crisis. Journal of Economic Geography 11 (4): 587–618. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbq024.

- Moomaw, R., and Alwosabi, M. 2004. An empirical analysis of competing explanations of urban primacy evidence from Asia and the Americas. Annals of Regional Science 38 (1): 149–71. doi:10.1007/s00168-003-0137-x.

- Moomaw, R. L., and Shatter, A. M. 1996. Urbanization and economic development: A bias toward large cities? Journal of Urban Economics 40 (1): 13–37. doi:10.1006/juec.1996.0021.

- Muellerleile, C. 2009. Financialization takes off at Boeing. Journal of Economic Geography 9 (5): 663–77. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbp025.

- Mundlak, Y. 1978. On the pooling of time series and cross section data. Econometrica 46 (1): 69–85. doi:10.2307/1913646.

- Nitsch, V. 2006. Trade openness and urban concentration: New evidence. Journal of Economic Integration 21 (2): 340–62. doi:10.11130/jei.2006.21.2.340.

- Oxford Economics. 2014. Global cities 2030: Methodology note, November 2014. Oxford Economics. https://wwwoxford economicscomuponsubscription.

- Paluzie, E. 2001. Trade policies and regional inequalities. Papers in Regional Science 80 (1): 67–85. doi:10.1007/PL00011492.

- Poelhekke, S., and van der Ploeg, F. 2009. Foreign direct investment and urban concentrations: Unbundling spatial lags. Journal of Regional Science 49 (4): 749–75. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9787.2009.00632.x.

- Porteous, D. J. 1995. The geography of finance: Spatial dimensions of intermediary behaviour. Aldershot, UK: Avebury.

- Rajan, R. 2019. The third pillar: How markets and the state leave the community behind. New York: Penguin Random House.

- Rauch, J. E. 1991. Comparative advantage, geographic advantage and the volume of trade. Economic Journal 101 (408): 1240–44. doi:10.2307/2234438.

- Scott, A. 2001. Global city-regions: Trends, theory, policy. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Shiller, R. J. 2008. The subprime solution. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Sjöberg, Ö., and Sjöholm, F. 2004. Trade liberalization and the geography of production: Agglomeration, concentration, and dispersal in Indonesia’s manufacturing industry. Economic Geography 80 (3): 287–310. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2004.tb00236.x.

- Smith, A. [1776] 2008. An inquiry into the nature and causes of the wealth of nations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- United Nations. 2018. The world’s cities in 2018. https://www.un.org/en/events/citiesday/assets/pdf/the_worlds_cities_in_2018_data_booklet.pdf.

- Urban, M. 2019. Placing the production of investment returns: An economic geography of asset management in public pension plans. Economic Geography 95 (5): 494–518. doi:10.1080/00130095.2019.1649090.

- Vesentini, J. W. 1987. A capital da geopolítica. São Paulo, Brazil: Ática.

- Williamson, J. G. 1965. Regional inequality and the process of national development: A description of the patterns. Economic Development and Cultural Change 13 (4): 1–84.

- Wójcik, D. 2011. The global stock market: Issuers, investors, and intermediaries in an uneven world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wójcik, D. 2012. The end of investment bank capitalism? An economic geography of financial jobs and power. Economic Geography 88 (4): 345–68. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2012.01162.x.

- Wójcik, D. 2013. The dark side of NY-LON: Financial centres and the global financial crisis. Urban Studies 50 (13): 2736–52. doi:10.1177/0042098012474513.

- Wójcik, D., and Burger, C. 2010. Listing BRICs: Stock issuers from Brazil, Russia, India, and China in New York, London, and Luxembourg. Economic Geography 86 (3): 275–96. doi:10.1111/j.1944-8287.2010.01079.x.

- Wójcik, D., and MacDonald-Korth, D. 2015. The British and the German financial sectors in the wake of the crisis: Size, structure and spatial concentration. Journal of Economic Geography 15 (5): 1033–54. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbu056.

- World Bank. 2008. World development report 2009: Reshaping economic geography. Washington, DC: World Bank.

- ____. 2018. World development indicators. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://datacatalog.worldbank.org/dataset/world-development-indicators.

- Zhang, P. 2020. Home-biased gravity: The role of migrant tastes in international trade. World Development 129 (May): 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104863.

Appendix B

Models of with Fixed Effects and First-Stage Results for the Instrumental Variable Models of