Abstract

Innovative finance is now considered essential to mobilize the trillions projected as required to meet the sustainable development goals. The International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), which issues vaccine bonds, is an emblematic example of innovative finance in global health and development. Since its launch in 2006, IFFIm has played a leading role in developing social bonds and funding global health, securing over $8 billion in donor commitments, and disbursing over $3 billion to date to Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance. Adopting a follow the money approach, we set out a significant, evidence-based challenge to some of the dominant development claims around innovative development finance more widely and IFFIm in particular. We find evidence of nontrivial private profit making, hiding in plain sight, at the expense of beneficiaries and donors. Through advanced critical financial analysis, we reveal precisely who benefits and by how much. Furthermore, our analysis shows in detail how financialization reduces political control over aid, and the uneven spatial distribution of material rewards and political power. While IFFIm delivers on its claim to front-load aid commitments and makes a significant contribution to global health, the article asks whether the economic and political costs of innovative financing mechanisms are worth it. We finish by showing that alternative models for vaccine finance are possible. A postscript provides a brief account of how IFFIm has responded to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Immunization constitutes a critical part of global health and development agendas. Gavi, the Vaccine Alliance, helps vaccinate almost half the world’s children against certain infectious diseases. Since it was set up in 2000, Gavi has immunized over 822 million children and prevented an estimated 14 million deaths (Gavi Citation2020a). It costs $28 to vaccinate a child against all eleven World Health Organization recommended childhood vaccines in Gavi-eligible countriesFootnote1 (Gavi Citation2020b). So, who pays for these programs? How is this effort financed? And how could it be financed? The answers to these questions are all the more pertinent in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, which adds a new and extraordinarily challenging disease to the schedule, even as it challenges efforts to stay on track with vaccination schedules for the other eleven diseases. This article is concerned with the International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm), which has provided about 20 percent of Gavi’s funding (IFFIm Citation2020a), thus making a significant contribution to global health and development. IFFIm is touted as an emblematic success story of innovative financing for development. It issues vaccine bonds in capital markets (mostly) in the Global North, backed by donor government pledges. The capital raised through these bonds from institutional and individual investors is used to finance Gavi immunization and health system strengthening programs. Donor government grants are subsequently used to pay the vaccine bonds’ interest and principal. Given its central role and significant scale in financing global health, and its leading role in developing social bonds and in innovative financing for development, IFFIm’s model warrants close examination.

This article makes a specific and novel contribution to the significant body of work on financialization. First, we set out the precise mechanisms of financialization in relation to vaccine bonds, and through an original methodology of following the money, we present a detailed, quantitative assessment of the key claims around IFFIm’s model. We uncover a complex model that does not, in practice, deliver fully on those claims, and in particular, show how this innovative financing mechanism for development offers significant opportunities for private profit. Remarkably, this is hiding in plain sight; a nontrivial amount of resources are peeled off by private finance actors in the context of explicit social goals. Beyond this primary contribution, the article adds to the growing literature on development finance and the financialization of development, in particular of global health. It goes beyond a financialization of account to focus on the (geo)economic and (geo)political consequences of financialization. Here, our research into vaccine bonds supports other critical work on financialization. We show how financialization reduces political control over aid (including its transparency and accountability) and the spatially uneven distribution of both material rewards and political power. Together, these findings represent a significant evidence-based challenge to some of the key development claims of innovative development finance, including mobilizing private resources or aid additionality. While IFFIm delivers on its front-loading mandate, making a significant contribution to global health, our findings also point to an ordinary development finance model that is costly for beneficiaries and donors, and that fundamentally relies on public finance. Finally, our financial analysis provides a potentially powerful evidence base for engaging with policy elites on the costs of this sort of innovative financing; and to this end, we finish with a brief outline of a more cost-effective way that vaccine financing could be achieved.

Before turning to the substance of the article, the next section briefly reprises the concept of financialization—its connection to the state, profit, and economic geography, and the financialization of development. The following sections then outline the article’s follow the money methodology, and present IFFIm and its financing model. The subsequent sections analyze the politics of IFFIm, its financial model, and the political and economic geography of IFFIm. In the final section, we conclude and outline alternatives.

Financialization: The State, Profit, Economic Geography, and Development

This article is concerned with the increased social and spatial reach of finance into global health and development, which has drawn new people and places into the financial system, reconfiguring roles and relationships often in unequal and uneven ways (Pike and Pollard Citation2010). Finance is connected to political systems and space (Harvey Citation2018; Pike and Pollard Citation2010), the real economy (Leyshon and Thrift Citation2007), and contributes to the production of “material, social and political unevenness” (Pike and Pollard Citation2010, 34; see also Froud et al. Citation2000; Leyshon and Thrift Citation2007; Hall Citation2012). This article draws primarily on the definition of financialization as the “growing influence of capital markets, their intermediaries, and processes in contemporary economic and political life” (Pike and Pollard Citation2010, 29). While in its essence, this definition is close to Epstein’s (Citation2005, 3) widely cited, broad definition of financialization as the “increasing role of financial motives, financial markets, financial actors and financial institutions in the operation of the domestic and international economies,” it explicitly centers on broadly conceived economic and political life relevant to the study of development cooperation, in contrast to alternatives that narrow the focus of study to firms or households that suit different empirical work (see, e.g., Krippner Citation2005; Blackburn Citation2006; Froud et al. Citation2006).

The article engages with the consequences of the financialization of development and global health, and heeds calls for care over conceptual stretching. It moves beyond a financialization of account to answer the so what? of financialization (see Engelen Citation2008; Christophers Citation2015; Mader, Mertens, and Van der Zwan Citation2020). Financialization as a concept has been variously treated as what is to be explained, the explanation, and as the mechanism linking cause to effect (Aalbers Citation2019). Here we use a mechanism-oriented concept of financialization. This recognizes Aalbers’s (Citation2019) argument that the concept of financialization can be imprecise because of the empirical complexities of the cases financialization aims to understand, and in those cases, causation should be recognized as nonlinear, multidimensional, and multiscalar. We examine in detail the why, how, and so what of financialization, revealing the link between the processes and mechanisms of financialization and their consequences.

We draw on and contribute to key themes in the financialization literature: the state’s role and politics, profit, and uneven economic geographies. The state plays a critical and active role in financialization processes. In the case of urban redevelopment policy through tax increment financing, for example, Weber (Citation2010) shows how local governments actively participated in constructing financial markets and instruments. More specifically, Weber (Citation2010) finds that the financialization of local urban policy requires political authority and state control, specifically over processes of asset creation, valuation, and securitization. Others have highlighted the state’s convening and enabling role through concepts of state-capital hybrids (McGoey Citation2014; Paudel, Rankin, and Le Billon Citation2020; Alami, Dixon, and Mawdsley Citation2021). The state is not just a key actor in financialization processes; its decision-making is increasingly oriented toward financial markets’ interests (Weber Citation2010; Dowling Citation2017). Social policy and local democratic control are constrained by various financial market imperatives, including bondholder-value disciplines, the logic of derivatives, and the demands of credit rating agencies, which govern access to debt finance (Bryan and Rafferty Citation2014; Peck and Whiteside Citation2016; Omstedt Citation2020). Indeed, Peck and Whiteside (Citation2016, 238) argue that the financialization of urban governance has been “accompanied by a drift toward postdemocratic modes of technocratic management,” echoing literature on scientific finance in which finance and its practices are depoliticized and rendered technical (see De Goede Citation2005; Pryke Citation2006). This shift toward technocratic management is further supported by complex and opaque operations that reduce democratic control and scrutiny (Peck and Whiteside Citation2016) in favor of privatized political decision-making (Bracking Citation2012). In the case of the financialization of Thames Water, for example, Allen and Pryke (Citation2013) argue the politics of the financial arrangements were ring-fenced and left untouched. Relatedly, Rosenman (Citation2019) shows how social finance dis-embeds social problems from the political system. Drawing on Scharpf’s (Citation1999) input legitimacy and output legitimacy framework of democracy, two general dynamics can summarize the way financialization limits democratic legitimacy: first, political options are constrained by financial interests and logics (on the output side); and second, financialization shifts decision-making power to nonelected actors (on the input side) (Nölke Citation2020). As we shall see, IFFIm’s vaccine bonds reflect many of these concerns, in this case in relation to the accountability and transparency of foreign aid budgets, more properly known as official development assistance (ODA).

A second, important line of enquiry relates to the dynamics of profit and accumulation, which characterize financialization, specifically the distribution of surpluses to financial investors (Allen and Pryke Citation2013) and to financial intermediaries (Folkman et al. Citation2007), often supported by public funds. In the context of social finance schemes, for example, Dowling (Citation2017) finds that the financialization of the welfare state through social impact bonds results in the transfer of wealth from public to private investors as interest payments. In impact investing in housing in San Francisco, Rosenman (Citation2019) finds that public subsidies in the form of federal tax credits, and the subordination of public assets to private debt, support impact investors’ returns and protect them from risk. In water utilities, Allen and Pryke (Citation2013) find value is redistributed to investors at the expense of households through restructuring debt and dividend payments exceeding profits, while Paudel, Rankin, and Le Billon (Citation2020) find that disaster financialization in postearthquake reconstruction in Nepal created lucrative opportunities for capital accumulation for both banks and more informal financial agents such as moneylenders. In each case, investors and financial intermediaries do not just reap (sometimes substantial) profits but change the underlying landscape of accumulation, risk, and reward in doing so. However, while these findings are aligned in demonstrating that financial actors profit, few studies quantify how much is being accumulated and peeled off by different beneficiaries, something this article sets out below.

The third key theme is how finance or financialization shapes uneven economic geographies. Financialization connects different actors, spaces, and places to uneven development, and strengthens the fundamental role of finance in explaining their unfolding economic geographies (Pike and Pollard Citation2010). Hall (Citation2012) argues that the intersection between finance and economic geographies should be understood in relational terms, whereby topological flows of money and finance intersect with established geographic spaces (like households or cities), creating new economic geographies (see also Raco, Sun, and Brill Citation2020). For example, geography is shaped by the interplay between, on the one hand, the aggregation of assets in particular places and, on the other, the spoils of speculation concentrated in cities (Leyshon and Thrift Citation2007). In this way, finance is seen as a driver of restructuring across space that shapes economic geographies in a particularly uneven form (Harvey, Citation2004, Citation2018; Smith Citation2010; Corbridge, Martin, and Thrift Citation1994). In this context, financialization research can often be focused at the national or urban scale. However, the global, which is where finance capital circulates, is also a critical scale of enquiry (Christophers Citation2012).

This article examines the increasing social and spatial reach of capital markets and their financial intermediaries (see Pike and Pollard Citation2010) into the arena of global health and development. The wider context of this research is a changing development landscape in which private finance is being solicited and facilitated to play a growing role (Blowfield and Dolan Citation2014; Mawdsley Citation2015). In pursuit of the sustainable development goals, the United Nations (Citation2020) states that “urgent action is needed to mobilize, redirect and unlock the transformative power of trillions of dollars of private resources.” Beyond aid conceptualizes the transformation of development through a reduced role of aid relative to other contributions to development finance (Janus, Klingebiel, and Paulo Citation2015), captured by the mantra from billions to trillions (World Bank Citation2015). In this vision, the role of aid and public finance has become to unlock or catalyze private finance in a shift from ODA to development finance (Mawdsley Citation2018)—similar narratives of leveraging private capital exist in social and green finance (Rosenman Citation2019; Cohen and Rosenman Citation2020). In development, bilateral and multilateral donors are acting as handmaids to the expansion and deepening of financial markets and logics in the name of development, mitigating risks for private capital or escorting capital to emerging markets, and doing the work of transforming mundane objects into assets for speculative capital (Leyshon and Thrift Citation2007; Soederberg Citation2013; Carroll and Jarvis Citation2014; for examples, see Baker Citation2015; Brooks Citation2016; Hunter and Murray Citation2019).

Methodology: Follow the Money

The article adopts a follow the moneyFootnote2 methodology. This constitutes an original development of follow the thing, a methodology that has its origins in the work of Harvey (Citation1990) and Appadurai (Citation1986). The article follows the circulation and distribution of money, tracing its flows through IFFIm, to reveal the social and economic relations, and redistribution of material wealth (see Christophers Citation2011) connected to the financialization of vaccine funding. Kass (Citation2020, 112) argues that “financial information can provide powerful empirics that can expose inequity, be used to probe institutional norms and priorities, and provide insight into processes of neoliberalization and financialization.” Hughes-McLure’s skills in advanced critical financial analysis enabled her to follow the money, such that financial data is the field site through which the article explores IFFIm’s financing model, its claims, and its implications. Developing and adopting this follow the money approach provides rich empirical evidence to gain insights into both the mechanisms and consequences of financialization, including uncovering the precise redistribution of material rewards as well as insights about innovative development finance more broadly.

Comprehensive financial data was collected to build a detailed model of all of the flows of money between the different actors involved in IFFIm for each year from 2006 to 2019 (the time period for which there is complete data to follow the money; see “Postscript” for detail of more recent activity). This data is available from IFFIm’s Annual Reports, both the Report of the Trustees and the Financial Statements (made up of the Balance Sheet, Income Statement, Cash Flow Statement, and Notes to the Financial Statements) as well as the Bond Documentation, which includes the Offering Memorandum, Prospectus, and Pricing Supplements.Footnote3 These were supplemented with information from IFFIm’s website, press releases, investor presentations, and brochure, as well as public macroeconomic data. To give an indication of the depth and detail of this analysis, the whole process of following the money took about four months of focused work.

IFFIm: Success and Financial Model

IFFIm is emblematic of innovative financing for development, and the financialization of global health and development more broadly. IFFIm was praised as a catalytic success story in the 2012 G8 summit official report (G7 Research Group Citation2012; see also IFFIm Citation2012), which noted that it has been game changing for global immunization. IFFIm is cited as a leading example of an innovative finance mechanism for development in the UN’s Addis Ababa Action Agenda (UN Citation2015) as well as by the World Bank (Girishankar Citation2009), OECD (Sandor, Scott, and Benn Citation2009), World Economic Forum (Citation2019) and United Nations Development Programme (Citation2012) among many others. IFFIm’s model is touted as an innovative way of realizing future aid commitments that front-loads the availability of funds (see Ratha, Mohapatra, and Plaza Citation2008; for a more recent OECD exposition of front-loading, see Kapoor Citation2021). IFFIm has served as inspiration for other innovative financing mechanisms, including very directly in the case of a proposed International Finance Facility for Education. IFFIm was the first issuer of vaccine bonds, and is celebrated as a pioneer of social bonds and socially responsible investment, receiving many awards, including the Financial Times and International Finance Corporation’s (World Bank Group) Achievement in Transformational Finance Award (IFFIm Citation2015), and mtn-I’s SRI Innovation of the Decade (IFFIm Citation2013). IFFIm has been influential for the International Capital Market Association’s (ICMA) set of social bond principles, first released in 2017, which aim to support the social bond market (ICMA Citation2017).

IFFIm issues vaccine bonds in capital markets, backed by long-term legally binding commitments from donor governments. The capital raised from institutional and individual investors is used to finance Gavi immunization and health system strengthening programs. Donor government grants are subsequently used to pay the bonds’ interest and principal. Proponents argue the main benefits of IFFIm’s innovative financing model are (1) front-loading to make funds available to Gavi earlier than they would otherwise be, (2) low funding costs, and (3) its ability to leverage private- sector funds. Heralded as a success, IFFIm had secured $6.5 billion in donor commitments since its inaugural issuance in 2006 up to 2019. IFFIm is backed by grants from ten donor governments (ordered by commitment size up to 2019): the UK, France, Norway, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Australia, Sweden, South Africa, and Brazil. Of the $6.5 billion total pledged by 2019 for the 2006 to 2037 period, the UK accounts for $3.0 billion and France $1.9 billion. Backed by these pledges, IFFIm had issued thirty-five bonds by 2019, raising $6.6 billion from investors. Of that funding, IFFIm disbursed $2.9 billion to Gavi between 2006 and 2019, which represents over 20 percent of Gavi’s total funding, although in Gavi’s initial years, IFFIm provided over half of Gavi’s funding.

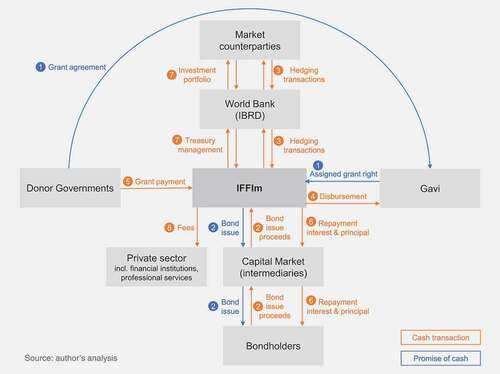

Mapping the flow of money, as part of following money, captures the essence of IFFIm’s financing model (see ) and reveals a network of actors connected through a complex set of financial flows:

Donor governments sign irrevocable grant agreements (often spanning fifteen to twenty years) with Gavi, which assigns the grant rights to IFFIm;

IFFIm issues bonds in capital markets, backed by donor governments’ pledges, and receives the bond proceeds;

IFFIm enters into hedging agreements with the World Bank for its currency and interest rate risk exposure for donor government grants, and bond interest and principal payments; the World Bank enters into hedging agreements with market counterparties;

Following a funding request from Gavi, IFFIm makes disbursements to immunization programs;

Donor governments make grant payments to IFFIm, fulfilling their pledges;

IFFIm makes interest and principal payments to bondholders;

Throughout, IFFIm is transacting with the World Bank as its treasury manager, including in respect to IFFIm’s significant investment portfolio, which holds investments with market counterparties; and

IFFIm incurs a variety of fees due to financial institutions, professional services and other companies.

It is worth noting, at this stage, that IFFIm operates with a board of trustees and no employees. Gavi performs IFFIm’s administrative functions, and treasury management operations are done by the World Bank.

IFFIm is a clear case of the financialization of development, and specifically, finance extending and deepening its reach into global health. Through IFFIm, vaccine delivery in lower-income, Gavi-eligible countries becomes connected to global financial flows. IFFIm securitizes aid (ODA) provided by donors—through vaccine bonds, IFFIm bundles and sells the rights to income from future donor government grants. In this way, government grant agreements—a stable income stream—are converted into financial instruments and exchanged in capital markets. This process gives rise to a range of financial flows, in addition to the payment of aid by donors and disbursement of grants to Gavi: capital market transactions related to bonds (bond issuance proceeds, the payment of interest and principal on bonds, and the trading of bonds), treasury management transactions with the World Bank, investment portfolio transactions, and hedging transactions. Furthermore, a plethora of financial actors are enrolled in different roles in this process: financial institutions (in connection to the bond program) act as arranger of the overall bond program, managers, dealers, placers, the trustee (or the delegate), paying and transfer agents, the registrar, the exchange agent, the listing agent, the share trustee, and the commodity agent; financial institutions (in connection to IFFIm’s other financial transactions) take the roles of investment portfolio managers and counterparties to hedging transactions; credit rating agencies rate IFFIm; and pension funds, insurance companies, asset managers, and other financial institutions together with central banks and other official institutions enter as bondholders. The map, therefore, points to the extensive work needed to transform Gavi funding into vaccine bonds that represent assets available for speculative capital.

The Politics of IFFIm

We turn now to the story of IFFIm’s origins and present an analysis of its (geo)-political consequences, notably how its model limits political control.

In November 2001, in a speech to the Federal Reserve Bank in New York on reform of the international financial system, Gordon Brown, the then UK Chancellor of the Exchequer, called for a substantial increase in development assistance to address poverty. This call came in the wake of the adoption of the UN Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) in 2000, which promoted poverty eradication and represented a significant shift in international development agendas, although not a rejection of market-based approaches (Fukuda-Parr and Hulme Citation2009). In his speech, Brown argued the world’s richest countries must make substantial additional resource contributions to bridge the investment gap that the poorest countries face, suggesting governments could “pre-commit development resources” and “capital markets could be used to leverage up these contributions” (Brown in Willetts Citation2001). Enter Goldman Sachs (which would serve as IFFIm’s financial adviser on a pro bono basis) (IFFIm Citation2006a; Goldman Sachs Citation2020). In his behind-the-scenes account of the formation of IFFIm, Christopher Egerton-Warburton, then Goldman Sachs’s head of Sovereign Supranational and Agency Funding, and who later served on IFFIm’s board of directors between 2013 and 2018, recalls,

That speech was the founding concept of IFFIm. […] We were asked to meet Gordon Brown’s right-hand executive […] She hands us Brown’s speech and basically said, “can you solve this?”—meaning, figure out frontloading. That meant finding or creating a mechanism to bring forward the value of long-term government pledges, with cash flow only hitting the budget the year pledge payments are made. We created a financial mechanism for this Innovative Finance concept. (IFFIm Citation2019a)

In the words of Alan Gillespie, the former Chairman of IFFIm, “Goldman Sachs picked up the ball and ran with it and their involvement led to a more detailed proposal, which was put to the UK Treasury” (McCormick Citation2007, 79).Footnote4

On January 22, 2003, speaking at Chatham House, Gordon Brown announced the proposal for an International Finance Facility (IFF) to “bridge the development financing gap between the resources that have already been pledged and the additional funds that are now recognized as urgently necessary to meet the Millennium Development Goals” (Brown Citation2016). The facility sought to leverage in money from international capital markets to double development aid in the years to 2015, from $50 billion to $100 billion a year (Brown Citation2016). It was not until later that the IFF idea found a purpose for the funds: immunization, which was “amenable to immediate and rapid build up” (Gillespie in McCormick Citation2007, 80). Egerton-Warburton tells the story:

We presented the IFF idea to Alan Greenspan. He was in London at the time to be knighted. He heard us out and basically said, “If Goldman says this works, then I am sure it would work, but what would you spend the money on? You have to find something this can be attached to that’s completely bulletproof.” Soon after, Bill Gates came to Gordon Brown’s office and said he wanted long-term money for Gavi—and a lightbulb goes off. Then I get a phone call from Alice Albright, former CFO of Gavi, saying, “I understand that you have a scheme that we need to work on.” This crazy series of events is how IFFIm came to be (IFFIm Citation2019a).

In 2004, Linklaters were appointed to “do the same kind of thing as Goldman was doing on the financial side,” in the words of Jim Rice, one of the principal legal architects of the transaction structure (McCormick Citation2007, 80). Thus, the concept became reality as the design of IFFIm’s structure was thrashed out by Goldman Sachs, the UK government (the treasury and DfID [the Department for International Development]), Gavi, the World Bank, and Linklaters. As Kenneth Lay, chair of IFFIm’s board since 2020 and former World Bank treasurer, highlighted in a recent interview, “credit for IFFIm goes 100 percent to Gordon Brown, Christopher Egerton-Warburton, Alice Albright and Susan McAdams [of the World Bank] who worked with Egerton-Warburton to develop the IFFIm framework” (IFFIm Citation2021). Later in 2004, the UK and France committed to launch a pilot to apply the IFF principles to immunization. By September 2005, the founding European donors—the UK, France, Italy, Spain, Sweden, and Norway—had committed nearly $4 billion to IFFIm, announcing they would immunize an additional 500 million children and prevent 10 million deaths. In early October 2006, IFFIm, the World Bank (as treasury manager), Goldman Sachs (now in the commercial role of joint lead manager and arranger of the bond program), and Deutsche Bank (as joint lead manager) set off on a road show to meet potential investors in five European cities (IFFIm Citation2006b). One month later, on November 14, 2006, IFFIm issued its inaugural $1 billion vaccine bond.

Analyzing the (Geo)politics

Analyzing the story of IFFIm’s origins reveals the interplay of key individuals and institutions, already networked in webs of politics and finance. This can be analyzed through the idea of policy windows (for an excellent, related, example of this, see Fukuda-Parr and Hulme (Citation2009), on the MDGs in the late 1990s to early 2000s period). Gordon Brown, like Tony Blair, had a personal stated commitment to international development issues (Honeyman Citation2009), set within a strong New Labour commitment to development, most notable in the creation and relative autonomy of DfID. The MDGs were a moment of global optimism, in the context of a rising (if turbulent) period of economic growth. Both as chancellor and prime minister, Brown supported policies to expand spending while keeping it off-budget (an accounting advantage also featured in social impact bonds; see Dowling Citation2017). While this article cannot present a full analysis of the wider contexts and contestations around New Labour’s economic strategy and the factors shaping Gordon Brown’s turn to private finance initiatives (see Kitson and Wilkinson Citation2007; Sawyer Citation2007), we note that IFFIm did not emerge in a vacuum; it is a product of a very particular interplay of contexts, actors, circumstances, and choices. Notwithstanding some very significant global events, including the global financial crisis and the COVID-19 pandemic, IFFIm continues to operate as it was initially designed. We return to the question of IFFIm’s design in the conclusions. Here, we turn to the ways in which such innovative financial schemes rely on technocratic financial management and demand considerable technical complexity. As we will show, they also close down and limit future policy options.

Technocratic financial management, which weakens political control and limits accountability, is made possible through rendering technical and by shifting important decision-making to private financial actors. For IFFIm, in the policy context of the MDGs, the challenge of addressing poverty is rendered technical and de-politicized (Ferguson Citation1990; De Goede Citation2005; Li Citation2007). The UK’s proposal diagnosed the problem of global poverty as a temporal finance or investment gap, which had to be bridged. In turn, the necessary solution to this particular problem was presented as an innovative financing mechanism, specifically bonds as a mechanism for front-loading government pledges. Identifying a problem in a particular way is intimately linked to the availability of a solution (Li Citation2007), and solutions can already be in the bag (Ferguson Citation1990; Li Citation2007). There are myriad other ways a problem of insufficient resources to address either poverty or global immunization could have been framed, and bonds are not the only viable solution to increasing funding. Indeed, over the course of the creation of the IFF proposal and then IFFIm, the technical solution offered was refined. Starting from a range of potential ways for governments to (pre-)commit funding, such as a trust fund, guarantees, or callable capital, which could be levered up, the proposal narrowed down to bonds, whereby legally binding long-term government aid commitments would be leveraged through capital markets. Notably, bonds have been a part of the development landscape for many decades and, from the perspective of capital markets “the way the bonds were issued was very market standard and deliberately so. IFFIm issues are […] plain vanilla benchmark type transactions” (Rice in McCormick Citation2007, 82). This seriously challenges IFFIm’s claim to be innovative, both in terms of its use of original or novel financial instruments and in terms of its front-loading financial model, which is fundamentally rooted in the more ordinary concept of borrowing.

While the state, largely in the guise of an individual politician, Brown, appears as the seed for the idea of IFFIm, decision-making on neutral technical design details was delegated to private financial actors, selected based on their financial and legal expertise, which are oriented toward bondholders. In particular, decisions were made by an investment bank, Goldman Sachs, which now acts as the arranger for IFFIm’s Global Debt Issuance Programme and finance lawyers, specifically Linklaters, during the design phase. Credit rating agencies also strongly influenced the technical design of IFFIm. So, while the complexity of the scheme demands considerable technical expertise, as Allen and Pryke (Citation2013) observe, the effect is to politically ring-fence public money. However, designing IFFIm is not neutral but deeply political—choices are made about who is benefiting, in what way, by how much, who is paying, and who might be losing out.

The example of credit rating agencies’ influence on IFFIm illustrates some of the technocratic financial management practices at work in the design and operations of global health and development initiatives. As gatekeepers, credit rating agencies are important financial actors and play a significant role in financialization (Omstedt Citation2020). To begin, the decision over how to set up IFFIm—as a UK registered charity rather than an offshore special purpose vehicle (SPV) borrower—was heavily influenced by credit rating agencies. In the words of Gillespie again, “the rating agencies also wished to see it as an entity of some substance rather than just an SPV” (McCormick Citation2007, 81), and a UK charity “demonstrate[s] there is an element of regulation, for want of a better word” (Rice in McCormick Citation2007, 81). Another important decision in the structuring of IFFIm was to secure its classification as a supranational, which means that central banks and other official institutions can invest and that credit rating agencies adopt distinct criteria in their rating approach. For IFFIm, this means the rating approach is similar to multilateral development banks but tailored to its unique structure, such that ratings are primarily driven by support from donor governments. To support that argument, the legal and financial architects of IFFIm did not want it to have to give security to bondholders over its rights to receive the income stream from the donor government pledges. Rice, of Linklaters, illustrates the power of the credit rating agencies, as he said, “we went into bat very heavily with the rating agencies, insisting that security was not needed,” adding “we spent a long time on this” (McCormick Citation2007, 82). Turning to the credit rating assessments, one of the most important legal issues the credit rating agencies focused on was the validity and effectiveness of the government pledges, resulting in a time-consuming process to ensure the pledges were legal, binding, and enforceable (McCormick Citation2007). On the financial side, the credit rating agencies focused on “the importance of swapping all pledges into floating dollars up front to take any currency volatility out of the credit structure” (Gillespie in McCormick Citation2007, 83) as well as the World Bank being party to the structure to bring their financial management experience to IFFIm. These technical design decisions, in part influenced by credit rating agencies, are evident in the final financing model of IFFIm, which uses swaps to hedge all its currency and interest rate exposure for both donor government grants (assets) and bond interest and principal payments (liabilities), and has the World Bank as its treasury manager.

The weakening of democratic control over innovative development finance (compared to ODA) is further exacerbated by the financial mechanism’s technical complexity, which limits detailed scrutiny. Technical complexity surrounds the complex network of actors and flows of money (see ); the volume of financial intermediation through capital markets with respect to the bonds, and through the World Bank with respect to hedging transactions and the investment portfolio; and the use of several financial instruments, including bonds, swaps, and long-term legally binding government pledges. Furthermore, IFFIm’s design could be said to weaken democratic decision-making by foreclosing policy options available to future governments. Once grant agreements, which are long term (often lasting fifteen to twenty years) and large in scale (usually hundreds of millions of dollars and sometimes over $1 billion) have been signed, they are irrevocable legally binding commitments on future governments. In fact, this requirement for long-term pledges is not constitutionally possible in some countries, including the US, one of the key reasons its government is not a donor to IFFIm.

IFFIm’s Financing Model under Scrutiny: Profit Hiding in Plain Sight

This section analyzes the (geo)economic consequences and implications of IFFIm’s financial model. Most importantly, we reveal the very significant opportunities for private profit hiding in plain sight.

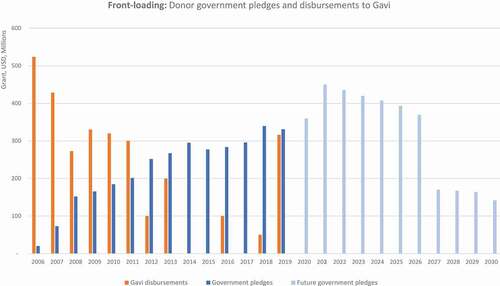

IFFIm’s financing model delivers on its key claim to front-load long-term donor commitments, making funding available to Gavi sooner than might otherwise happen under more traditional rounds of donor pledging. This has a health benefit because, in IFFIm’s words, “There is zero value vaccinating a child in 10 years if he or she dies from a vaccine-preventable disease this year” (IFFIm Citation2019b). Our research confirms this significant front-loading effect, especially in IFFIm’s early years where Gavi receipts from IFFIm far exceed government grants (see ). Funded largely through a $1 billion inaugural bond issue in 2006, followed by ten notes issued in 2009 with proceeds of $1.1 billion and six notes issued in 2010 that raised $0.9 billion, IFFIm disbursed significant sums, totaling $2.2 billion to Gavi over the 2006 to 2011 period. However, beyond these early years, IFFIm’s disbursements to Gavi have been both significantly smaller and less frequent, totaling less than $0.5 billion between 2012 and 2018. A disbursement of $0.3 billion in 2019 could have been a sign of this trend reversing (more recent developments are addressed in the “Postscript”).

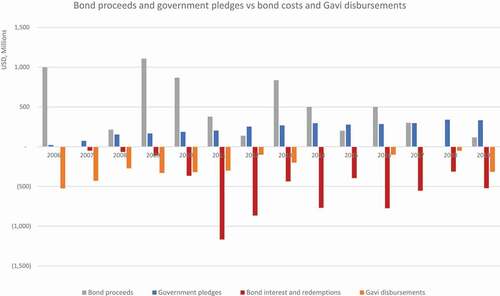

This winding down of disbursements to Gavi over the decade following its launch might be expected if IFFIm’s operations were wrapping up having delivered its front-loading mandate, but that is not the case. Between 2012 and 2019, IFFIm signed five new grant agreements with donors. IFFIm has also been active in capital markets, issuing thirteen bonds between 2012 and 2019. This points to the more complex financial logic, and the debt-fueled nature of IFFIm’s financing model: IFFIm must issue new bonds in order to make interest payments on and redeem old bonds. There is not a simple front-loading model operating as the narrative suggests with a one-to-one relationship between the government pledges backing bonds and the payments IFFIm makes to bondholders—IFFIm is dependent on borrowing from capital markets through bonds with much shorter maturities than the long-term government pledges backing those bonds (similar to Peck and Whiteside’s (Citation2016) debt machine). begins to illustrate this complex financial logic and credit-dependent model by comparing IFFIm’s income from bond proceeds and donor governments (as positive values) to expenses on interest and bond redemptions and grants to Gavi (as negative values). This strikingly captures the fact that capital market transactions (in grey and red) dwarf the size of the government grants that have been front-loaded, and the continuing necessity of issuing new bonds after disbursements to Gavi have tailed off. Behind the scenes, on top of the flows of money outlined above, IFFIm maintains a substantial volume of liquid assets managed as funds in trust by the World Bank, which averaged $775 million in end of year values between 2006 and 2019. Through this investment portfolio, IFFIm engages with financial markets through transactions in money market instruments, government and agency obligations, and corporate and asset-backed securities. IFFIm derives a reasonable income on its portfolio of on average $9.5 million per annum between 2006 and 2019. In summary, what we have shown here is the debt-driven financial logic of IFFIm’s financial model, its dependence on short-term global finance, and the significant size of capital market transactions it involves. All of these speak to both deepening financial markets in the name of development, and financialization seen in the increased influence of capital markets and increased social reach of financial intermediaries into the world of vaccines in poor countries.

IFFIm’s second key claim is low funding costs, because it is AAA rated by credit rating agencies and so can achieve low spreads on its bonds. Following the money reveals a different story of an expensive model with a plethora of mechanisms through which money is transferred to private financial actors. First, investors received good yields on IFFIm’s thirty-five bonds issued by 2019—many of IFFIm’s bond issuances are oversubscribed—with fixed rate bonds (twenty-nine of the thirty-five) priced to deliver an average 5 percent return and floating rate bonds (six of the thirty-five) priced with a decent average margin of 0.15 percent above LIBOR (the London Inter-Bank Offered Rate).Footnote5 These rates of return take into account not only interest rates but also that IFFIm has issued close to half of the thirty-five bonds at an issue price below 100 percent (including three deep discount bonds with prices close to 50 percent, although most exceed 99 percent) and redemption at par, meaning IFFIm receives a lower amount in bond proceeds than it must repay in principal to noteholders. Second, our analysis reveals that IFFIm has incurred $33 million in bond issuance costs to financial institutions, $24 million in professional services fees, and $29 million in treasury manager’s fees to the World Bank over 2006 to 2019. Third, IFFIm enters into costly hedging agreements to swap currency risks on all its grant agreements from donors on the asset side, and to swap interest rate and currency risk on the bonds it issues on the liabilities side, leaving IFFIm with $0.5 billion in liabilities for swap contracts on its balance sheet in 2019. This is a substantial sum, as evidenced by the additional risk management buffers the World Bank applied (see below). Fourth, IFFIm’s credit rating was downgraded to AA- over the 2012 to 2016 period, driven primarily by sovereign credit rating downgrades of the British and French governments that back IFFIm. While these all represent costs to IFFIm, donors, and ultimately Gavi and its beneficiaries, they are a bonanza for other actors. Critically, many of these figures are unavailable without the sort of forensic analysis we have conducted, and they are at odds with many of the claims around IFFIm.

IFFIm’s final benefit is hiding in plain sight. Payments on bonds and fees represent a significant profit opportunity with low risk for bondholders, financial institutions, and professional services firms. IFFIm has paid $879 million in interest, with more already committed in the future through existing outstanding bonds, and paid $135 million in redemption above issue price to bondholders between 2006 and 2019. Over the same period, as noted above, financial institutions have charged fees of $33 million for bond issuance costs, and professional services firms have earned $24 million, divided into $10 million for lawyers, $5 million for auditors, $4 million for insurance (trustee indemnity), and $3 million for consultants, with another $2 million spent on trustee meetings and travel. Of the $29 million in treasury manager fees the World Bank charged IFFIm, it is likely some of this was subsequently paid to private financial institutions in fees for hedging contracts and transactions related to IFFIm’s large investment portfolio. Taken together, over the 2006 to 2019 period, interest payments to bondholders, and payments to financial institutions and professional services firms total $936 million. As points of comparison, this represents 30 percent of the $3.137 billion in donor payments received, 14 percent of the $6.546 billion in donor pledges made, 15 percent of the $6.152 billion in bond proceeds raised, and 32 percent of the $2.942 billion in disbursements to Gavi over the same time period. When redemption payments above issue price or the World Bank’s treasury manager fees are included, these figures increase further. Looking from 2020 onward, through bonds that have already been issued (including three bonds issued since 2019), IFFIm has already committed approximately a further $440 million to bondholders (an estimated $315 million in interest and $125 million in redemption above issue price; figures are $84 million and $122 million excluding the three latest bonds), and will incur more fees for future bond issuances and annual reporting processes. In contrast, $357 million more has been committed to Gavi.

The rewards of IFFIm to investors and financial institutions are not only significant in size but also low risk because public finance protects investors. IFFIm has set several strict financial limits on its operations to manage risk, all aimed at mitigating risk for investors, and it often operates well within those limits. For example, the gearing ratio limit means IFFIm only issues bonds against part of overall donor commitments—70.3 percent as of December 2019, closer to two-thirds previously—with the remainder kept as a reserve to protect bondholders. At this level, investors can still be paid if donor governments default on up to 29.7 percent of their pledges. On top of this, in the face of IFFIm’s significant swap exposure level, from 2013 the World Bank applied a risk management buffer of 12 percent of pledges (more specifically the present value of expected future cash flow from pledges). Taking this buffer into account, IFFIm can service its debt to investors if governments default on 41.7 percent of their pledges.Footnote6 A third example is IFFIm’s liquidity policy, which means it maintains a minimum liquidity balance of twelve months’ projected debt service to bondholders—a level Fitch considers a “comfortable liquidity cushion” (Fitch Ratings Citation2016). This means IFFIm can still pay investors, even if it loses market access and cannot roll over debt for a year. A final example is the treasury manager’s requirement to prioritize debt service payments to bondholders over disbursements to Gavi. Taken together, IFFIm’s risk management and policies are described as conservative, prudent, and robust by the main credit rating agencies (see Fitch Ratings Citation2016; Moody’s Citation2018; S&P Global Citation2020). As a point of comparison, these levels represent more restrictive risk management to which commercial financial intermediaries are typically subject. The distribution of the implications is noteworthy: all four policies limit the amount of front-loading of funds to Gavi while providing a high level of protection for investors. These examples show some of the mechanisms at work distributing risk and the ways aid from governments is used to mitigate risk for private capital.

IFFIm’s third claim is to leverage or mobilize private-sector funds. While it is clear that IFFIm raises funds from private sources through capital markets and temporarily these borrowed funds go to Gavi, there is no aid additionality in IFFIm’s financing model. Fundamentally, publicly financed donor government grants are the ultimate source of payments to Gavi, and the other part of these grants is channeled to the private sector in the form of interest costs of borrowing from capital markets and fees—the opposite of the catalyzing narrative. As noted above, up to 2019, the equivalent of 30 percent of the $3.1 billion in donor government payments to IFFIm—that is, taxpayer money that is claimed to act in support of humanitarian and development outcomes—has been channeled to these financial actors: $879 million in interest to investors and $55 million in fees to financial institutions and professional services. In practice, the reality looks more like money being peeled off by private financial actors, since it flows through IFFIm’s model. All of this limits benefits to Gavi and, ultimately, to those children in low-income countries who do not receive the full vaccine schedule in a timely and safe manner.

Economic and Political Geography of IFFIm

In this penultimate section, in line with other critical analysts, we show how the distribution of material rewards and political power has a particular spatial pattern concentrated in financial centers in the Global North, which enhances existing inequalities.

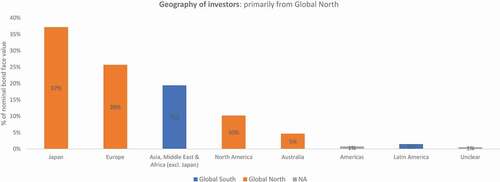

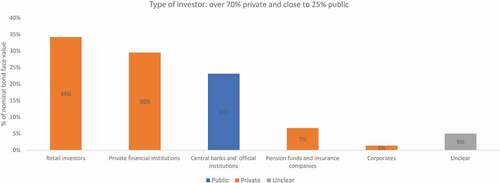

As a financial mechanism, bonds distribute financial rewards through interest and principal payments from IFFIm—drawing on income from donor government grants and other bond issue proceeds—to investors concentrated in financial centers in the Global North. Unsurprisingly, the investors buying IFFIm’s bonds and receiving a financial return (as outlined in the previous section, a crude indicative average yield of around 5 percent) are primarily from the Global North, representing over 75 percent of the face value (). Looking not only at place but also the types of actors () reveals the concentration of bondholders in financial centers: over 70 percent of the face value was placed with private investors, and just under 25 percent with central banks and other official institutions. The majority of these private investors are financial institutions (including banks, asset managers, and fund managers), pension funds, insurance companies, and other corporates that, together with central banks and other official public institutions, tend to be concentrated in financial centers. It is noteworthy that almost 25 percent of the face value of the bonds has been purchased by publicly financed institutions, further undermining claims to catalyze private resources and aid additionality. Perhaps more surprisingly, a significant number of investors are in Japan, and these are overwhelmingly retail investors. This is because IFFIm issued twenty-three Uridashi bonds with a total face value of $2.4 billion between 2008 and 2013. Uridashi bonds are typically denominated in a foreign currency and short term, and are sold to retail investors who want exposure to higher-yielding currencies than the Japanese yen to achieve a higher return than the historically low domestic interest rate (IFFIm’s Uridashi bonds were issued in South African rand, Australian dollars, New Zealand dollars, US dollars, Brazilian real, and Turkish lira). In the wake of the global financial crisis, the Uridashi market offered low spreads, meaning IFFIm could use this spatialized niche to shield itself from widening spreads and achieve lower borrowing costs—entangling retail investors in Japan with citizens around the world, including in the Global South.

Turning to the distribution of material rewards through fees as a financial mechanism shows a similar, perhaps more pronounced, spatial pattern centered on financial centers, especially London. The various financial institutions involved (arranger, managers, trustee, paying and transfer agents, registrar, exchange agent, and listing agent) are, for the most part, based in either London or Luxembourg —the latter is where the vaccine bonds are listed. Professional services firms (auditors and legal advisers to the various parties) are generally based in London, where IFFIm has its registered office. The only exceptions to this are for four of IFFIm’s thirty-five bonds, which were issued outside its Global Debt Issuance Programme. These were IFFIm’s Australian and New Zealand Note Programme where firms earning fees were also registered in Sydney and Auckland; and IFFIm’s three Sukuk,Footnote7 where companies were also registered in Grand Cayman, Frankfurt, Doha, Kuala Lumpur, Abu Dhabi, Riyadh, Dubai, and Bandar Seri Begawan.

The financial management and rewards provided by IFFIm are aligned with—reflective of and produced by—a similar distribution of political decision-making. IFFIm emerged in the policy context of the MDGs, which have been critiqued as an agenda set by rich countries reflecting priorities of the Global North without meaningful consultation of countries in the Global South (Hulme and Scott Citation2010). Within this particular policy window (see Kingdon Citation2003), the UK state, and specifically Gordon Brown as chancellor, emerges as the source of the seed for the idea of IFFIm as well as its key promoter. This seed was nurtured, requiring a significant amount of work, by both public- and private-sector actors, and eventually bloomed as the IFFIm state-market hybrid, with the full legally binding financial commitments of government development agencies and finance ministries, initially all in Europe. Throughout the story of IFFIm, the state has agency and plays a central role in the assemblage that creates IFFIm and builds a market for vaccine bonds. This process, which is necessarily connected to place, reveals a particular spatial political structure centered on the UK, or London more specifically. It is the UK government that emerges as the central (political) state figure, represented by the chancellor, the teasury and DfID. Looking beyond state actors reveals a similar concentrated, uneven spatial pattern of power. Decision-making on important financial and legal matters were delegated to or advised on by specialist financial and legal private-sector actors based in London (the financial institutions, professional services firms, and credit rating agencies identified earlier). Similarly, operational matters relating to bond issuances are conducted by financial institutions predominantly based in London. This pattern is further reinforced by the spatially uneven, although slightly less concentrated, distribution of bondholders and their agents in financial centers in the Global North (). This is important geopolitically; state actors or technical advisers from intended beneficiary (Gavi-eligible) countries are not present. Instead, the political decision-making, power, and control over financial flows is connected to particular places, which, as we saw, are also the ones that materially benefit from IFFIm’s financing model.

The financialization of global health and development is shaping economic geographies in which material rewards are distributed unevenly, concentrating in (a small number of) financial centers in the Global North. Vaccine recipients in the Global South, immunization delivery programs, and aid become connected to global financial flows, which, through the financial mechanisms that constitute IFFIm’s bond financing model, distribute returns in a particular, uneven pattern. Similarly, the decision-making power and influence over financial flows, which rests with the actors that make up IFFIm’s financing model, namely, bondholders, financial institutions, professional services firms, and certain state actors, are also connected to space and place in this uneven concentrated pattern. The result is material, social, and political inequality.Footnote8

Conclusion

The financialization of global health and development—in this case, through vaccine bonds—has important (geo)economic and (geo)political consequences. IFFIm is cited by supporters of the innovative development finance agenda as an emblematic success story, securing $6.5 billion in government pledges by 2019 (over $8 billion by mid-2021) and disbursing $2.9 billion to Gavi ($3.1 billion by mid-2021) by front-loading aid through bonds for immunization. However, a detailed examination of its financing model reveals a more complex picture. First, technocratic financial management, shifting decision-making to private financial actors, and the financial model’s technical complexity weaken political control over global health and aid. Second, the financing model creates significant opportunities for private profit hiding in plain sight, as nontrivial resources are peeled off by private finance actors. Third, the distribution of material rewards and political power has an uneven spatial pattern centered on financial centers, shaping particular economic geographies of global health and development. Together, these findings challenge some important claims of innovative development finance. They point to a development finance model that is expensive for donors and beneficiaries, fundamentally relies on public finance without creating aid additionality, and employs ordinary and common financial instruments and logics.

IFFIm’s front-loading effect has been substantial, with immediate benefits to any children that Gavi would not otherwise have been able to vaccinate. Donor decisions to fund IFFIm have contributed to saving an estimated 2.9 million of the 14 million lives saved by Gavi (IFFIm Citation2020a). Without losing sight of IFFIm’s significant contribution to global health, it remains important to examine its financial model’s opportunity costs. So, are there alternatives, given a world in which development finance is constrained? To put the costs of IFFIm’s front-loading model into perspective, it is worth comparing the costs to an alternative financing model, whereby donor governments could borrow through long-term bonds themselves to fund Gavi directly. The UK ($3.0 billion) and France ($1.9 billion) are the largest donors representing 75 percent of the $6.5 billion in pledged commitments by 2019. At the time of IFFIm’s inaugural bond issuance in November 2006, the UK government ten-year bond yield stood at 4.55 percent and the French yield at 3.74 percent. Both of these countries’ ten-year bond yields fell over the period to reach lows of 0.58 percent for the UK and −0.34 percent for France in late 2019. These borrowing costs are lower than IFFIm’s: the average yield of IFFIm’s fixed rate bonds (issued between 2006 and 2013) is 5.12 percent, and the interest on IFFIm’s floating rate bonds (issued between 2013 and 2019) is a margin of 0.15 percent on average plus the three-month US dollar LIBOR, which averaged 1.08 percent over the period (with a range from 0.22 percent to 2.82 percent). So, the alternative, whereby governments would borrow through bonds, could deliver the same front-loading effect, allowing the bond issue proceeds to be disbursed to Gavi immediately, and interest and principal repayments to be made over a long time period. The government bonds could be structured to replicate the grant schedule in IFFIm where governments make roughly equal payments annually, for example, through an installment note or even a zero-coupon installment note with an issue price a little below 100 percent. Not only would this financing model deliver front-loading, but it would also do so at a lower cost of funding, without necessarily resulting in debt-fueled dynamics (where new bonds are issued to repay previous ones). Such an approach would also be more open to democratic scrutiny, although it would not solve the problem of concentration around existing financial centers and capital markets or their intermediation of the economic geographies of global health and development.

Coming at this from a very different perspective, a different identification of the problem as investment gap would have different solutions that do not draw on funds intermediated through capital markets. The problem of access to immunization for children in low-income countries could have been (and can still be) identified as one of (artificially) high pharmaceutical prices (see, e.g., Christophers Citation2020 or the Médecins Sans Frontières Access Campaign), a lack of health care system infrastructure, or a limited ability for low-income countries to raise sufficient taxes (see, e.g., the Tax Justice Network’s work). Solutions to these problems might involve reform to intellectual property right law, grant funding or direct payments for health centers and training medical staff, or reform to international tax systems and tackling capital flight from low-income countries.

The choice and design of how to finance immunization programs, and broader global health and development agendas, has important material, political, social, and spatial consequences. The criticality of these financing models has been brought sharply into light by the COVID-19 pandemic, debates about how to finance the research and delivery of vaccines, and how to ensure global and equitable access. But these questions are not new, and a discussion of them should not be restricted to COVID-19 or vaccines or even global health. We must ask whether the costs of innovative financing mechanisms are worth it. The financialization of many aspects of social and economic life need close examination to reveal the material, political, social, and spatial consequences, often hiding in plain sight, in particular precisely how, how much, by who, and where resources are peeled off.

Postscript

IFFIm has been active after 2019, the last year with complete data to follow the money, particularly in securing donor pledges and in capital markets. The year 2020 was a Gavi replenishment year and, amidst the global COVID-19 pandemic, IFFIm has positioned itself as a mechanism to solve the funding gap for COVID-19 vaccines (IFFIm Citation2020b) and correspondingly increased its activity. An additional $1.1 billion in government pledges were announced in June 2020 around Gavi’s replenishment summit and, in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, a further $0.8 billion was pledged in December 2020 largely for COVAX and the Coalition for Epidemic Preparedness Innovations (CEPI), with more pledges already announced in early 2021 (although not all of these have yet been finalized at the time of writing). In 2020 and 2021, IFFIm issued three bonds raising almost $1.5 billion from investors. The first was a NOK2 billion (approximately $210 million) zero-coupon installment note backed by the Norwegian government to fund CEPI, and the other two were US dollar benchmark notes with face values of $500 million and $750 million. So far, this substantial fund-raising has not yet translated into announcements of any significant disbursements to Gavi. By December 2020, IFFIm disbursements to Gavi reached $3.1 billion, a relatively modest increase from $2.9 billion the previous year. In 2020 and the first half of 2021, the pattern identified in the article of raising considerable sums of government aid (almost $2 billion), matched by substantial bond issuances ($1.5 billion) to front-load public funding and refinance debt, and a significantly smaller sum reaching Gavi, continues. Despite the financial and political costs of IFFIm’s financialized innovative model, donors continue to consider it an effective and valuable model for funding vaccines at a global level, while investors, financial intermediaries, and other professional services firms continue to benefit from a good low-risk source of financial rewards.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank editor Jane Pollard and three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments, as well as Sally Brooks for her thoughtful response to our article as part of the “For-profit development” sessions at the RGS 2021 Annual Conference. Additionally, we would like to thank Carolina Alves, Charlotte Lemanski, and Frances Brill for their comments on earlier drafts. This research has been supported by the Economic and Social Research Council, through Hughes-McLure’s PhD award [ES/P000738/1].

Notes

1 Gavi eligibility is based on national income. In 2020, fifty-seven countries were eligible for Gavi support. A country is eligible if average gross national income (GNI) per capita has been less than or equal to $1,630 over the past three years. Initially, in 2000, the eligibility threshold was set at $1,000 GNI per capita, making seventy-four countries eligible.

2 This follow the money approach is the subject of a different article by Hughes-McLure (under review at press time). Following money, a very particular thing, raises challenging conceptual questions and requires specialized financial research skills. For here, though, the essential research details are provided without further elaboration.

3 Annual Reports and Bond Documentation are available on IFFIm’s website at https://iffim.org/news-resources/documents.

4 Interview with Gillespie and Rice reported in Law and Financial Markets Review journal.

5 We have two notes on IFFIm’s borrowing costs. First, an alternative calculation taking averages weighted by the bond’s nominal amount gives a higher weighted average return of 5.5 percent for fixed rate bonds and a higher weighted average margin of 0.18 percent over LIBOR for floating rate bonds. Second, in our analysis we do not net off interest expenses on bonds against income from the investment portfolio, since we consider that these flows of money do not constitute a fundamental pillar of IFFIm’s front-loading financial model, but rather a cash flow management decision.

6 In May 2020, IFFIm and the World Bank executed a swap recouponing, ending the additional risk management buffer and leaving IFFIm with an updated gearing ratio limit of 71.8 percent from June 2020.

7 A sukuk is a financial certificate used in Islamic finance that complies with Sharia law. Sukuk were developed as an alternative to conventional bonds, which are not considered compliant. It is similar to a bond in that investors receive a stream of payments until maturity; however, these payments are considered profit not interest. Additionally, a sukuk is structured so that investors have direct ownership interests in an asset, whereas bonds are interest-bearing debt obligations.

8 There is a parallel here with McGoey’s (Citation2016) analysis of the Gates Foundation. She observes that the foundation systematically enhances medical research capacities in the Global North and does not choose to invest in meaningful, longer-term research capacity in the Global South.

References

- Aalbers, M. 2019. Financialization. In The international encyclopedia of geography: People, the earth, environment, and technology, ed. D. Richardson, N. Castree, M. F. Goodchild, A. L. Kobayashi, and R. Marston. Oxford: Wiley Blackwell. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118786352.wbieg0598.pub2.

- Alami, I., Dixon, A., and Mawdsley, E. 2021. State capitalism and the new global D/development regime. Antipode 53 (5): 1294–318. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12725.

- Allen, J., and Pryke, M. 2013. Financialising household water: Thames Water, MEIF, and “ring-fenced” politics. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society 6 (3): 419–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rst010.

- Appadurai, A. 1986. The social life of things: Commodities in cultural perspective. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Baker, L. 2015. The evolving role of finance in South Africa’s renewable energy sector. Geoforum 64 (August): 146–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2015.06.017.

- Blackburn, R. 2006. Finance and the fourth dimension. New Left Review 39 (May/June): 9–72.

- Blowfield, M., and Dolan, C. S. 2014. Business as a development agent: Evidence of possibility and improbability. Third World Quarterly 35 (1): 22–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2013.868982.

- Bracking, S. 2012. How do investors value environmental harm/care? Private equity funds, development finance institutions and the partial financialization of nature-based industries. Development and Change 43 (1): 271–93. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-7660.2011.01756.x.

- Brooks, S. 2016. Inducing food insecurity: Financialisation and development in the post-2015 era. Third World Quarterly 37 (5): 768–80. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2015.1110014.

- Brown, G. 2016. 2003 speech at Chatham House. http://www.ukpol.co.uk/gordon-brown-2003-speech-at-chatham-house/.

- Bryan, D., and Rafferty, M. 2014. Financial derivatives as social policy beyond crisis. Sociology 48 (5): 887–903. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514539061.

- Carroll, T., and Jarvis, D. S. L. 2014. Introduction: Financialisation and development in Asia under late capitalism. Asian Studies Review 38 (4): 533–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/10357823.2014.956284/.

- Christophers, B. 2011. Follow the thing: Money. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space 29 (6): 1068–84. doi:https://doi.org/10.1068/d8410.

- Christophers, B. 2012. Anaemic geographies of financialisation. New Political Economy 17 (3): 271–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2011.574211.

- Christophers, B. 2015. The limits to financialization. Dialogues in Human Geography 5 (2): 183–200. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820615588153.

- Christophers, B. 2020. Rentier capitalism: Who owns the economy, and who pays for it? London: Verso Books.

- Cohen, D., and Rosenman, E. 2020. From the school yard to the conservation area: Impact investment across the nature/social divide. Antipode 52 (5): 1259–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/anti.12628.

- Corbridge, S., Martin, R., and Thrift, N. 1994. Money, power and space. Oxford: Blackwell.

- De Goede, M. 2005. Virtue, fortune, and faith: A genealogy of finance. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctttt651.

- Dowling, E. 2017. In the wake of austerity: Social impact bonds and the financialisation of the welfare state in Britain. New Political Economy 22 (3): 294–310. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563467.2017.1232709.

- Engelen, E. 2008. The case for financialization. Competition & Change 12 (2): 111–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1179/102452908X289776.

- Epstein, G., ed. 2005. Financialization and the world economy. Cheltenham,UK: Edward Elgar.

- Ferguson, J. 1990. The anti-politics machine: Development, depoliticization, and bureaucratic power in Lesotho. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Fitch Ratings. 2016. International Finance Facility for Immunisation (IFFIm)—Full rating report. https://www.fitchratings.com/research/sovereigns/international-finance-facility-for-immunisation-iffim-16-12-2016.

- Folkman, P., Froud, J., Johal, S., and Williams, K. 2007. Working for themselves? Capital market intermediaries and present day capitalism. Business History 49 (4): 552–72. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00076790701296373.

- Froud, J., Haslam, C., Johal, S., and Williams, K. 2000. Shareholder value and financialization: Consultancy promises, management moves. Economy and Society 29 (1): 80–110. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/030851400360578.

- Froud, J., Johal, S., Leaver, A., and Williams, K. 2006. Financialization and strategy: Narrative and numbers. London: Routledge.

- Fukuda-Parr, S., and Hulme, D. 2009. International norm dynamics and “the end of poverty”: Understanding the millenium development goals (MDGs). BWPI Working Paper 96. Brooks World Poverty Institute.

- G7 Research Group. 2012. Camp David G8 accountability report. Summary of the Camp David G8 Summit. http://www.g7.utoronto.ca/summit/2012campdavid/CampDavidG8AccountabilityReport.pdf.

- Gavi. 2020a. Facts and figures. https://www.gavi.org/programmes-impact/our-impact/facts-and-figures.

- Gavi. 2020b. About our alliance. https://www.gavi.org/our-alliance/about.

- Girishankar, N. 2009. Innovating development finance—From financing sources to financial solutions. World Bank Policy Research Working Paper 5111. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1503805.

- Goldman Sachs. 2020. IFFIm bonds: Financial innovation funds immunization in more than 60 countries. https://www.goldmansachs.com/our-firm/history/moments/2006-iffim-bonds.html.

- Hall, S. 2012. Geographies of money and finance II: Financialization and financial subjects. Progress in Human Geography 36 (3): 403–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132511403889.

- Harvey, D. 1990. Between space and time: Reflections on the geographical imagination. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 80 (3): 418–34. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8306.1990.tb00305.x.

- Harvey, D. 2004. Retrospect on the limits to capital. Antipode 36 (3): 544–49. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2004.00431.x.

- Harvey, D. [1982] 2018. The limits to capital. London: Verso Books.

- Honeyman, V. 2009. Gordon Brown and international policy. Policy Studies 30 (1): 85–100. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870802576256.

- Hulme, D., and Scott, J. 2010. The political economy of the MDGs: Retrospect and prospect for the world’s biggest promise. New Political Economy 15 (2): 293–306. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13563461003599301.

- Hunter, B., and Murray, S. 2019. Deconstructing the financialization of healthcare. Development and Change 50 (5): 1263–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/dech.12517.

- International Capital Market Association. 2017. IFFIm’s impact on SRI reflected in new social bond principles. https://iffim.org/sites/default/files/library/publications/other-publishers/rene-karsenti–iffim-s-impact-on-sri-reflected-in-new-social-bond-principles/Karsenti-ICMA%20article%20IFFIm%20impact%20on%20SRI%202017.pdf.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2006a. Spectacular response to IFFIm’s inaugural financing. https://iffim.org/press-releases/spectacular-response-iffims-inaugural-financing.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2006b. Paris presentation introduces a new supranational bond issuer: The International Finance Facility for Immunisation. https://iffim.org/press-releases/paris-presentation-introduces-new-supranational-bond-issuer-international-finance.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2012. World leaders describe IFFIm as a “catalytic success.” https://iffim.org/press-releases/world-leaders-describe-iffim-catalytic-success.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2013. IFFIm honoured by editors as capital market’s ‘SRI innovation of the decade.’ https://iffim.org/press-releases/iffim-honoured-editors-capital-markets-sri-innovation-decade.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2015. Financial Times presents ‘Achievement in transformational finance award’ to IFFIm. https://iffim.org/news/financial-times-presents-achievement-transformational-finance-award-iffim.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2019a. The edge of innovative finance. https://iffim.org/news/edge-innovative-finance.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2019b. IFFIm resource guide. https://iffim.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/IFFIm%20resource%20guide%202019_0_0.pdf.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2020a. Impact. https://iffim.org/impact.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2020b. IFFIm stands ready to support COVID-19 vaccines. https://iffim.org/news/iffim-stands-ready-support-covid-19-vaccines.

- International Finance Facility for Immunisation. 2021. The lay of land. https://iffim.org/news/lay-land.

- Janus, H., Klingebiel, S., and Paulo, S. 2015. Beyond aid: A conceptual perspective on the transformation of development cooperation. Journal of International Development 27 (2): 155–69. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/jid.3045.

- Kapoor, S. 2021. OECD development matters, frontloading finance can save lives, tackle climate change and generate real impact. https://oecd-development-matters.org/2021/04/28/frontloading-finance-can-save-lives-tackle-climate-change-and-generate-real-impact/.

- Kass, A. 2020. Working with financial data as a critical geographer. Geographical Review 110 (1–2): 104–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00167428.2019.1684193.

- Kingdon, J. W. [1984] 2003. Agendas, alternatives, and public policies. 2nd ed. New York: Longman.

- Kitson, M., and Wilkinson, F. 2007. The economics of new labour: Policy and performance. Cambridge Journal of Economics 31 (6): 805–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/cje/bem045.

- Krippner, G. R. 2005. The financialization of the American economy. Socio-Economic Review 3 (2): 173–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/SER/mwi008.

- Leyshon, A., and Thrift, N. 2007. The capitalization of almost everything: The future of finance and capitalism. Theory, Culture & Society 24 (7–8): 97–115. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276407084699.

- Li, T. 2007. The will to improve: Governmentality, development, and the practice of politics. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Mader, P., Mertens, D., and Van der Zwan, N. 2020. The Routledge handbook of financialization. Oxford: Routledge.

- Mawdsley, E. 2015. DFID, the private sector and the re-centring of an economic growth agenda in international development. Global Society 29 (3): 339–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13600826.2015.1031092.

- Mawdsley, E. 2018. Development geography II: Financialization. Progress in Human Geography 42 (2): 264–74. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516678747.

- McCormick, R. 2007. Using the capital markets for good works: An interview with Alan Gillespie, the chairman of international finance facility for immunisation, and Jim Rice of Linklaters. Law and Financial Markets Review 1 (2): 79–84.