Abstract

Global production network (GPN) scholars increasingly focus on examining exclusionary processes in strategic coupling. However, attention has been given to structural coupling, where uneven outcomes often evolve through lead firms exploiting power asymmetries to foster their interests over regions. Functional and indigenous coupling, although acknowledged to have exclusions, are considered to be less likely for such outcomes due to assumed symmetrical power. This assumption has led to a lack of studies exploring not only how uneven outcomes evolve in indigenous coupling but also what territorial mechanisms are involved. This article addresses this gap by conceptualizing the notion of a statist transnational community (STC) as a crucial mechanism in indigenous coupling, and with potential to explain how asymmetrical relations can emerge and foster exclusionary processes. Based on qualitative methods, this article analyzes Brazil's integration into the aerospace GPN through indigenous coupling. First, it examines how the Brazilian developmental state, under a national developmental ideology, fostered coupling in São José dos Campos (SJC) by establishing institutions, regional assets, Embraer, and an aerospace industrial cluster. Second, it elucidates how the Brazilian state facilitated the formation of an STC crucial in establishing firms and creating and harnessing regional assets. Additionally, it reveals how and why the SJC STC is marked by relative symmetrical and cooperative relations, and encourages collaboration. Lastly, this article investigates a training partnership between Embraer and the Aeronautics Institute of Technology in SJC, disclosing how asymmetrical power relations can also be present in indigenous coupling, fostering social downgrading, especially in relation to labor.

A key contribution of mainstream research on global production networks (GPNs) is its explanation of regional development through strategic coupling. This process involves integrating regions and their assets into global value chains (Coe and Yeung Citation2015). Scholars have focused on the positive outcomes of strategic coupling, examining its effects on value creation, enhancement, capture, and social upgrading. However, there is growing interest in exploring its uneven outcomes (Phelps, Atienza, and Arias Citation2018; Scholvin Citation2022; Selwyn et al. Citation2023; Teixeira Citation2024). As some scholars have demonstrated, exclusions are not just unfortunate by-products, but rather constitutive elements of GPNs (Bair and Werner Citation2011).

One notable advance is how the literature has identified different modes of coupling and how some are more likely to result in uneven outcomes than others. Such studies suggest the outcomes of strategic coupling depend on the power balance between place-specific institutions and lead firms (Lim Citation2018). The dark side of strategic coupling is often linked to structural coupling, a scenario wherein uneven outcomes stem from bargaining processes where asymmetrical power relations prevail, rendering regions in a disadvantaged position in their negotiations with lead firms due to the existence of generic assets. This is compounded by the mobility of global lead firms, enabling them to play off different regions (Coe and Hess Citation2011; Mackinnon Citation2012; Yeung Citation2016). This rationale indicates the need to expand existing studies on how uneven outcomes evolve in indigenous coupling. Scholars characterize indigenous coupling as marked by relative symmetrical, reciprocal, cooperative, and collaborative relationships due to the presence of distinctive assets, since coupling often happens through state-led initiatives that foster the coevolution of institutions, assets, lead firms, and business conglomerates (Coe and Hess Citation2011; MacKinnon Citation2012; Coe and Yeung Citation2015; Yeung Citation2016). Given that, indigenous coupling is often associated with positive outcomes, where uneven outcomes are overlooked (Hassink Citation2021).

Against this backdrop, this research addresses two main questions: How do uneven outcomes evolve in indigenous coupling, and what are the main territorial mechanisms involved? To tackle these questions, this article examines the territorial mechanisms underlying the integration of São José dos Campos (SP, Brazil) into the aerospace GPN. Specifically, it focuses on the role of the state, Embraer, and a statist transnational community (STC) in the Brazilian aerospace indigenous coupling. Embraer, a Brazilian national champion, is the fourth-largest aircraft company in the world after Boeing, Airbus, and Bombardier. It designs, manufactures, and sells small and mid-size agricultural, military, executive, and commercial airplanes in São José dos Campos (SJC).

This research contributes to the GPN literature in two ways. First, it expands upon recent GPN studies that explore the territorial mechanisms underpinning strategic coupling (Dawley, Mackinnon, and Pollock Citation2019; Indraprahasta, Derudder, and Hudalah Citation2019; Fu and Lim Citation2022). It does so by proposing the notion of an STC as a crucial territorial mechanism in indigenous coupling. Second, it advances the studies on GPN’s uneven developmental processes. GPN scholars have increasingly explored the dark side of GPNs; however, there remains room to explore the topic further (Phelps, Atienza, and Arias Citation2018; Murphy Citation2019; Yeung Citation2021), especially when it comes to indigenous coupling. In this regard, this article challenges the assumption of inherent symmetry within indigenous coupling by demonstrating the potential for asymmetrical power relations to emerge and result in social downgrading.

The article is divided into five sections. The next section provides an overview of the GPN literature on strategic coupling and its relation to regional development. This is followed by a section introducing the territorial mechanisms that foster indigenous coupling. It also develops the concept of an STC to explain the contradictory nature of (a)symmetrical relations in indigenous coupling and how uneven outcomes can evolve. Methodology is the next section. The penultimate section examines Brazil's aerospace indigenous coupling and the formation of an STC in SJC. It also analyzes a training partnership between the Aeronautics Institute of Technology (a federal university) and Embraer to demonstrate how a process of social downgrading evolves in indigenous coupling. The last section is the conclusion.

Global Production Networks, Strategic Coupling, and Uneven Outcomes

The global organization of industries and its impact on regional development have been important research topics in economic geography. One key analytical framework is the GPN. The GPN framework, initially termed the GPN 1.0, was developed in the 2000s to examine the dynamics and nature of economic globalization and its impact on regional development (Hess Citation2018). Based on three main categories (value, power, and embeddedness), it focused on both interfirm networks and regions’ territorial and institutional dimensions (Henderson et al. Citation2002; Coe et al. Citation2004; for in-depth detail, see Neilson, Pritchard, and Yeung Citation2014).

Subsequent studies revealed issues with the GPN 1.0, stemming from its broad framework and a lack of causal explanations. This led Coe and Yeung (Citation2015) to reconceptualize the framework as GPN 2.0. The authors propose to examine the strategies of lead firms (intrafirm coordination, interfirm control, interfirm partnership, and extrafirm bargaining) in GPNs, the configuration of the chain, and regional development according to risk environment and competitive dynamics such as optimizing cost–capability ratio (optimizing process to achieve greater firm capability and value capture), sustaining market development (dynamic of creating and sustaining market reach and access to maximize value capture), and financial discipline (the role of finance in maximizing shareholder value) (Coe and Yeung Citation2015). Under the GPN 2.0, one concept that continued to gain relevance to explain regional development is strategic coupling (Coe and Yeung Citation2015).

Strategic coupling refers to the process “through which actors in cities and/or regions coordinate, mediate, and arbitrage strategic interests between local actors and their counterparts in the global economy” (Yeung Citation2009, 213). The GPN 2.0 has incorporated in its framework three modes of strategic coupling (Fuller and Phelps Citation2018; see also Coe and Yeung Citation2015). Structural coupling refers to how regions are often inserted into GPNs through export processing zones that attract mobile foreign direct investments (FDIs). In functional coupling, global integration often happens through strategic partners who establish links as suppliers with lead firms elsewhere or have made a direct presence via FDI (Yeung Citation2015; Coe and Yeung Citation2015). Indigenous coupling, the focus of this article, refers to how regions are inserted into GPNs through indigenous innovation, an inside-out process led by state policies where “regional actors reach outside their home region to construct GPNs” (Coe and Yeung Citation2015, 184). In this mode, regional assets and lead firms or business conglomerates coevolve in the same region (MacKinnon Citation2012). While in MacKinnon’s (Citation2012) typology, this mode is conceptualized as organic coupling, in the GPN 2.0, it has been termed indigenous, because the term organic dismisses how the state strategically fosters the endogeneity of this coevolution for the benefit of the regional economy (Coe and Yeung Citation2015).

One example of indigenous coupling can be seen in the Seoul Metropolitan Area (South Korea), where endogenous dynamics resulted in the birthplace of well-known firms such as Samsung (Yeung Citation2015). Some key elements that differentiate these three coupling modes are lead firms’ degree of autonomy, type of power relations between regions and firms (symmetric to asymmetric), characteristics of regional assets (specific to generic), level of regions’ dependency on lead firms, and decoupling risk (low to high) (McGregor and Yeung Citation2022).

Strategic coupling fosters regional development because when regions and their assets are plugged into GPNs, they can stimulate value creation, enhancement, capture, and social upgrading (Henderson et al. Citation2002; Coe et al. Citation2004). However, the degree to which regions benefit from GPNs is dependent on different forms of power such as institutional power (institutions’ capacity to influence lead firms’ investments and decisionsFootnote1), corporate power (firms’ ability to influence resource allocations and decisions), and collective power (influence of labor and civil society organizations such as trade unions, not-for-profit organizations, activist groups, social movements, and community-based organizations) (Coe et al. Citation2004; Lim Citation2018; Ji et al. Citation2022; Wickramasingha and Coe Citation2022). Under the GPN 2.0 framework, Coe and Yeung (Citation2015) explore the notion of extrabargaining and discuss how firms, extrafirm actors, and territories interact and draw upon these forms of power, influencing strategic coupling outcomes. Here, the authors also acknowledge that the outcomes of strategic coupling are influenced by firms’ political economic contexts.

In the last years, there has been a growing interest in examining GPNs’ uneven effects on regions, where scholars have increasingly theorized how GPNs contribute to uneven development (Phelps, Atienza, and Arias Citation2018; Scholvin Citation2022; Selwyn et al. Citation2023; Teixeira Citation2024). A notable advancement in strategic coupling research is the differentiation of coupling modes, such as functional, structural, and indigenous coupling, where some are acknowledged to be more prone to uneven development than others (Yeung Citation2009; Mackinnon Citation2012; Coe and Yeung Citation2015).

In such studies, focus is given to structural coupling rather than functional and indigenous (Hassink Citation2021). In structural coupling, regions often have generic assets and are more likely to experience uneven outcomes. The lack of specific assets exacerbates power asymmetries, disadvantaging states during bargaining events and negotiations over coupling conditions as global mobile firms play off regions, weakening their bargaining power (Coe and Hess Citation2011; Mackinnon Citation2012; Coe and Yeung Citation2015; Yeung Citation2016). In indigenous coupling, regions are considered to have strong autonomy, and distinctive or highly distinctive assets that match the interests of lead firms (MacKinnon Citation2012; Yeung Citation2015). Therefore, power relations among actors in indigenous coupling are often and problematically described as symmetrical (but rarely fully symmetrical, since a level of hierarchy always exists), because relationships often carry some “measure of mutual interest and dependency” (Coe and Hess Citation2011, 133). In GPN research, relationships in indigenous coupling are also described as marked by cooperation, collaboration, reciprocity, or collective action (see MacKinnon Citation2012; Coe and Yeung Citation2015; Yeung Citation2015). Given that, GPN scholars often assume indigenous coupling (and functional) to be less likely to result in decoupling and exclusionary regional outcomes than structural coupling (Coe and Hess Citation2011; MacKinnon Citation2012; Coe and Yeung Citation2015; Yeung Citation2016).

This is not to say that GPN scholars do not recognize potential drawbacks in indigenous coupling. For example, Yeung (Citation2016) and Coe and Yeung (Citation2015), under the GPN 2.0, mention that indigenous coupling can result in firms receiving large state-sanctioned benefits, political exclusion, social and class conflicts, and exacerbating regional differences and socioeconomic inequalities. Yet, such issues are not further examined, leaving room for additional research.

Unlike structural coupling, indigenous coupling involves the coevolution of regional assets and lead firms or business conglomerates within a single region (MacKinnon Citation2012). Therefore, exclusions in indigenous coupling cannot be assumed to arise from the lack of specific assets that exacerbates power asymmetries in the context of highly mobile firms playing off different regions. This points out the need to further examine the territorial mechanisms underlying indigenous coupling, how exclusions evolve, and the nature of its (a)symmetrical relations. Therefore, the following section develops the notion of an STC as a crucial territorial mechanism in indigenous coupling and to explain how uneven outcomes evolve.

Indigenous Coupling: Territorial Mechanisms and Relative Symmetrical and Cooperative Relationships

Industrial Organization

According to GPN scholars, lead firms in GPNs often adopt technological and organizational innovations to address their competitive problems, resulting in new forms of industrial organization (Yeung Citation2009). Such new forms of organizational–technological capabilities present opportunities for regions to plug themselves into GPNs. For example, this can happen through the rise of lead firms, such as national champions or business conglomerates, in indigenous coupling, strategic partners in functional coupling, and export processing zones in structural coupling (Coe and Yeung Citation2015; Hassink Citation2021).

The State and Regional Institutions

Regional institutions play a crucial role in strategic coupling. This holds not only for state institutions but also civil society organizations, which shape the distribution of value capture across different GPN actors within a region (Coe and Yeung Citation2015; see Selwyn Citation2013). However, analytical attention will be given to the state (and its interaction with firms) and STCs. This article draws on the work of Smith (Citation2015), Horner (Citation2017), Rutherford et al. (Citation2018), and Dawley, Mackinnon, and Pollock (Citation2019) to examine the role of the state in indigenous coupling.

First, this article investigates the state's role in integrating domestic firms into GPNs through indigenous coupling based on state development models. According to the regulation theory, state development models consist of a mode of regulation and an accumulation regime or strategy (Jessop and Sum Citation2006). Jessop (Citation1990) suggests that an accumulation strategy delineates the overarching strategy of states in pursuit of growth and arises from the balance of forces within the state, where one fraction becomes hegemonic under an institutional compromise. State accumulation strategies rely on modes of regulation, which have as one key element a mode of insertion into the global economy that dictates how states pursue integration into GPNs (Smith Citation2015).

Second, it adopts Horner’s (Citation2017) work. According to Horner (Citation2017), the state can have different roles in strategic coupling such as producer, buyer, regulator, and facilitator. The article will explore the role of the Brazilian state as a producer, buyer, and regulator in its aerospace indigenous coupling.

Third, it scrutinizes the state and regional institutions through Jessop's (Citation2001) strategic relational approach, which explains how state's institutional context exhibits selectivity, favoring certain actors, strategies, and paths over others. It also shows how actors outside and within the state possess the agency to act strategically in alignment with their interests. Consequently, some actors wield more influence than others in shaping state’s role/action in strategic coupling (Dawley, Mackinnon, and Pollock Citation2019). Furthermore, Dawley, Mackinnon, and Pollock (Citation2019) underscore the necessity of a multiscalar approach (vertical governance structures at subnational, national, and global levels; and horizontal firm networks) when examining regional institutions, and to consider informal norms and conventions in the analysis of regional institutions (see also Coe and Yeung Citation2015).

This approach to the state and regional institutions is congruent with Gong and Hassink's (Citation2019) theorization of coevolution, which this article adopts to examine indigenous coupling as a process that involves reciprocal, causal relationships between two or more distinct populations (such as firms, industries, and formal and informal institutions, among others). According to the authors, the analyses of coevolutionary processes should take into consideration how these distinct populations are embedded at and influenced by multiple scales, locations, and higher-level systems (e.g., specific models of development) as well as specific historic contexts and institutional changes.

Transnational Communities

Drawing from Saxenian's work (Citation2002, Citation2006), Coe and Yeung (Citation2015, 219) describe transnational communities as “business and technology professionals who originate from one regional economy and shuttle constantly around the globe.” GPN scholars view transnational communities as crucial elements in strategic coupling. They serve as knowledge network nodes, intermediaries, and transactional links, promoting domestic company development and establishing new enterprises and connections with former employers. This, in turn, supports GPN integration (Yeung Citation2009; Coe and Yeung Citation2015; Hassink Citation2021).

In GPN studies, transnational communities are primarily motivated by self-interest, specifically in launching businesses and establishing ties with past global employers. Within this approach, the state's role is limited to encouraging or courting entrepreneurs’ return from the Global North (Saxenian Citation2002; Yeung Citation2009). However, broadening this approach to include the state's more active involvement with transnational communities in indigenous coupling is essential. This broader approach has the potential to refine the existing understandings of the territorial mechanisms underpinning indigenous coupling and of how it can also be marked by asymmetrical power relations that lead to uneven outcomes despite the presence of distinctive regional assets. To do so, the notion of an STC is developed in the next section.

The Active Role of the State and STCs in Indigenous Coupling

This article draws from the transnational capitalist class (TCC) concept to develop the notion of an STC. The TCC encompasses globalizing professionals; state managers such as bureaucrats and politicians; nonstate actors like merchants, media representatives, members of private or not-for-profit organizations, site consultants, engineers, and scientists; and those controlling and owning multinational corporations. These individuals work in different types of organizations (private, public, and not-for-profit), and perceive one another as allies and share similar beliefs and ideologies (Sklair Citation1998, Citation2002). However, the TCC can exhibit ideological differences (Harris Citation2012). Robinson and Harris (Citation2000) introduce the concept of the statist transnational capitalist class, which, unlike the TCC, maintains close ties with the state and shares the ideology that economic development occurs through global integration, primarily driven by the state under national strategic goals rather than global market liberalization (see also Harris Citation2009).

Therefore, based on TCC research, this article conceptualizes STCs not merely as a collection of international mobile entrepreneurs and technologists or company owners and nodes of transactional links within global networks but also as a faction of the TCC with all its variety of actors. By combining Saxenian’s notion of transnational communities and TCC, this article defines STCs as having three main characteristics. First, their sense of belonging to a specific community is not only related to having a similar international profile and networks but also encompasses a shared ideology, often centered on national developmentalism and related state projects, which bond them together.Footnote2 Second, the state's role in STCs extends beyond merely attracting returning professionals from the Global North, as seen in strategic coupling (see Yeung Citation2016). STCs can emerge from state-led coevolutionary processes of indigenous coupling. Furthermore, the state actively establishes and fosters close ties and cooperation with STCs that can result in collaboration, often around state projects such as creating national champions (Bresser-Pereira Citation2018). Such ideology and state projects can encourage cooperation, relative symmetrical relationships, and active collaboration among the actors of STCs, firms, and the state. Third, not only self-interest motivates STCs but also the state. Given that the emergence of STCs is connected to a state project, STCs are a crucial mechanism in fostering state goals such as establishing or supporting domestic business conglomerates and lead firms (like national champions), and creating and harnessing regional assets such as natural resources, specialized skills, knowledge, technology, competencies, infrastructure, and institutions (Dawley, Mackinnon, and Pollock Citation2019). STCs support these state goals through direct action or intermediating collaborations among firm and nonfirm actors at multiple scales.

Despite GPN mainstream literature suggesting that indigenous coupling is less likely to foster uneven outcomes due to the relative symmetrical nature of its relations (see Mackinnon Citation2012), this article posits that asymmetrical relations can emerge in indigenous coupling, fostering corporate capture. For example, Munir et al. (Citation2018) observe that GPNs are intersected by transnational elites and institutions sharing common economic imaginaries, which can align with firms’ interests, potentially leading to adverse outcomes for labor. Bresser-Pereira (Citation2018) further contends that while the state can establish collaboration with firms related to national projects based on the premise of defending the nation's interests against dependency and subordination to developed countries, it can also utilize this as a mechanism to cater to the interests of national lead firms, neglecting other interests such as those of workers. Therefore, such as dynamic can foster asymmetrical power relations between the state and lead firms, on the one hand, and workers, on the other hand.

Methodology

This research is based on qualitative methods, often employed in case studies and used to comprehend the underlying factors driving participants’ motivations, behavior, and actions (Yin Citation2009; Rosenthal Citation2016). A qualitative approach was selected, given the research’s intricate aspects related to power dynamics, interactions among various actors, and values and perceptions. Twenty-seven interviews were conducted with representatives from firms (5), development agencies (3), not-for-profit organizations (4), labor union (1), state institutions (7), and educational institutions (7). Semistructured interviews were adopted, a useful format for follow-up queries, an in-depth dialogue, and a rich collection of information (Adams Citation2015).

Participants were chosen intentionally based on their role and involvement in the phenomenon under study. Interviews were mostly conducted in person in SJC and São Paulo (two online using Zoom), averaged one hour, and were sometimes repeated. Most interviews were conducted between 2016 and 2019, with some additional in 2022. Interviewees received informed consent and were anonymized. Ethical considerations were based on the guidelines of the Institutional Review Board. Secondary data from internet reports, academic studies, newspaper articles, companies’ annual reports, governmental documents, and secondary census data were also collected. Using NVivo, the data was coded, categorized, analyzed, and summarized. When possible, using triangulation, findings were crossed based on the materials collected (see Yeung Citation1997).

The Brazilian Import-substitution Accumulation Strategy and the Aerospace Indigenous Coupling in SJC, São Paulo, Brazil

In the post–World War II era, Brazil adopted the import-substitution development model (1930s–1980s). This model aimed to reduce foreign dependence by promoting domestic firms in specific sectors, diversifying the economy, and boosting domestic industrial production (Oliveira Citation2004; Santos Citation2015). To foster accumulation, the Brazilian developmental stateFootnote3 constructed an institutional compromise, aligning the national developmental project with nascent Brazilian industrial capital interests. FDI also played a key role (Oliveira Citation2004; Souza Citation2016), resulting in domestic and international industrial capitalists acquiring a hegemonic position within the Brazilian state.

Two forms of strategic coupling prevailed. Structural coupling was achieved by attracting manufacturing FDI in consumer and durable goods (Santos Citation2015). Indigenous coupling was fostered by the establishment of state-owned firms and the support of domestic firms, mainly related to heavy industry and infrastructure. The Brazilian developmental state acted as a producer, regulator, and buyer. As a producer, Brazil established state-owned firms such as Vale S.A. (metals and mining), Companhia Siderúrgica Nacional (metals and mining), Petrobrás (oil and gas), Telebrás (telecommunication), and Embraer (Santos Citation2015). As a regulator, Brazil implemented measures benefiting domestic firms, including currency devaluation, increased import tariffs, and financial incentives like federal loans (Bruno Citation2005). As a buyer, Brazil often served as the primary client of state-owned firms to support initial production (Forjaz Citation2005).

Under the import-substitution model, the Brazilian state plugged SJC into the aerospace GPN via indigenous coupling. This involved the coevolution of aerospace skills, technology, Embraer, and an aerospace industrial cluster in SJC. The next subsection describes this process.

Aerospace Indigenous Coupling in SJC: The Coevolution of Institutions, Aerospace Skills, Technology, Embraer, and SJC Aerospace Industrial Cluster

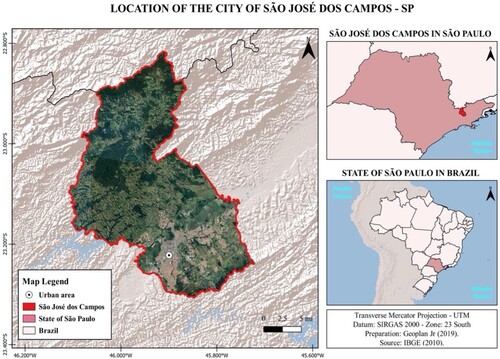

SJC, situated in São Paulo, Brazil (see ), boasts a population of 697,428 as of 2022 (IBGE Citationn.d.). In 2020, the city presented impressive economic and human development indicators, including a gross domestic product of US$7.9 billion (twentieth position out of 5,570 nationwide cities) and a Human Development Index of 0.807 (twenty-fourth position nationwide) (IBGE Citationn.d.). Today, SJC is known as the Brazilian “capital of airplanes” with over 15,000 employees in the aerospace sector due to the presence of an aerospace industrial cluster (with 95 percent of all the nation's aerospace firms), Embraer, as well as aerospace skills and technology (PIT Citationn.d.). In 2022, Embraer employed 16,067 workers worldwide, with 12,000 in SJC in 2019 (SMSJC Citation2019; Embraer Citation2022).

SJC’s insertion into the aerospace global production happened through indigenous coupling, a process in which institutions, aerospace skills, technology, Embraer, and a local aerospace industrial clusterFootnote4 coevolved locally, led by state initiatives. Under the Brazilian import-substitution accumulation regime, one state strategy was to develop aerospace technological autonomy and the defense sector through the creation of a state-owned aerospace company (Henrique and Ricci Citation2012). However, Brazil had a deficit in aerospace skills and technology.

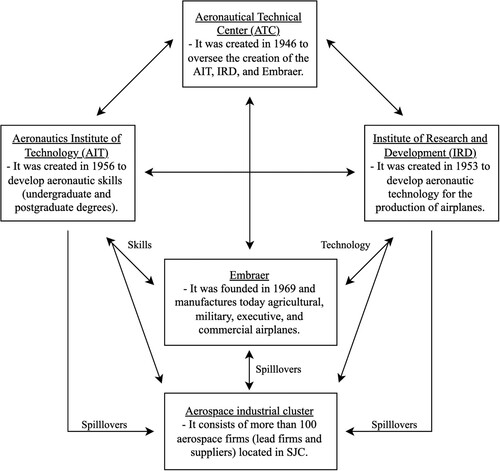

To address this deficit, the Brazilian national state established, in 1946, the Aeronautical Technical Center (ATC) in SJC, the role of which was to oversee the formation of the Aeronautics Institute of Technology (AIT) and the Institute of Research and Development (IRD) (Coimbra and Hopfer Citation2017). The AIT, a federal university, was created in 1950 with a clear mission: to develop aerospace skills by offering under- and postgraduate degrees in engineering (ITA Citationn.d.). In parallel, the IRD was set up in 1953 to develop civil and military aircraft and related technologies. In 1964, Brazil underwent a military regime (1964–85). During this period, its strategy to reduce national security vulnerabilities, particularly in the aerospace sector, gained stronger support (Schneider Citation2013). As a result, in 1964, the national state increased its support to the IRD, enabling it to employ three hundred individuals, mostly AIT alums, to develop a small airplane prototype in 1968 named EMB-110 Bandeirantes (Coimbra and Hopfer Citation2017). Therefore, the state established the AIT and IRD to develop aerospace skills and technology, needed to create Embraer. One participant stated,

SJC is a city that somehow was enormously benefitted by the federal government in the 40s […]. The creation of the ATC generated DNA in the region of innovation and technology. […] It has important ingredients such as a highly skilled workforce, and the presence of the government with its strategic orientation. (Interview #26, SJC Technology Park, 2016)

In 1969, with the necessary assets established, the Brazilian state, behaving as a producer, founded Embraer, a state-owned company. Embraer initiated the production of the Bandeirantes (21 passengers) with a team of 150 engineers (from the previous 300) supervised by 3 alums from the AIT who also worked at the ATC and had international experience: Ozires Silva, Ozílio Carlos da Silva, and Guido Fotegalante Pessotti (Bernardes Citation2000; Araujo Citation2013). The state also acted as a buyer to support Embraer, purchasing through public procurement 80 Bandeirantes, 112 Xavantes (military aircraft), and 50 Ipanemas (agricultural aircraft) in 1970 (US$1.2 billion in investment adjusted to 2024 value) (Silva Citation1999; Bernardes Citation2000). Additionally, in 1969, as a regulator, the state increased import taxation on airplanes and approved Embraer’s capitalization scheme, allowing companies to offset 1 percent of their annual tax debt by investing an equivalent amount in Embraer's shares (Forjaz Citation2005). In 1975, Embraer expanded sales internationally; by 1990, it had exported over five hundred airplanes to several countries (Fonseca Citation2012; Henrique Citation2012). The role of the Brazilian state in the creation of Embraer was described as follows:

[T]he AIT came first. The government could have created Embraer first, then the IRD, the AIT, and the National Institute of Space Research, but the government did not. The skilled workforce from Embraer induced everything. […] The AIT received investments; it was created at a time and in a country with nothing in the aerospace sector, let alone in other sectors. […] Brazil did not have a mechanic or aeronautic industry, so training had to come first. (Interview #10, AIT, 2017)

The establishment of the IRD, the AIT, and Embraer had other positive outcomes. After Embraer’s establishment, numerous former employees, researchers from the IRD, and alums from the AIT launched their firms as Embraer’s suppliers or, to a lesser extent, as start-ups (lead firms) based on innovations developed by the IRD. This resulted in an aerospace industrial cluster in SJC with over one hundred companies (suppliers and lead firms). As one participant highlighted, “Throughout the history of the ATC, it has been created more than 150 aerospace companies in SJC, some small, but others very large like Embraer” (Interview #10, AIT, 2017). Another participant stated, “The ATC attracted firms . . . originated many firms” (Interview #26, SJC Technology Park, 2016).

Therefore, the Brazilian state fostered its aerospace indigenous coupling by leading initiatives that resulted in the coevolution of institutions, assets (skills and technology), Embraer, and an aerospace cluster. The aerospace indigenous coupling process in SJC can be summarized as follows:

Indigenous Coupling and the Formation of an STC

This subsection explores how the coevolution of previously described institutions, assets, and firms formed an STC in SJC and established symmetric and cooperative relations among firm and nonfirm actors.

In GPN studies, the state plays a crucial role in courting the return of transnational community members, facilitating firm establishment, and fostering linkages with international firms (see Yeung Citation2016, Citation2009). However, in SJC, the Brazilian state had a more direct role. The state was responsible for organically forming SJC STC, with professionals within different segments of social spheres (working within state, private, and not-for-profit organizations), and with a strong sense of belonging and unity. Additionally, the state steers its actions to set the conditions for developing regional assets and firms.

The formation of SJC STC can be attributed to the Brazilian state's strategic initiative in fostering the creation of Embraer under a national developmentalism ideology. The formation of SJC STC started with the AIT initially training a group of engineers aimed at not only establishing aerospace skills but also a group of professionals capable of carrying on and implementing Brazil’s strategic goals for the aerospace sector (technology, skills, and creation of Embraer). One participant stated, “The first groups of engineers being trained at the AIT were not only trained for the sake of skills. The government had plans to produce airplanes, and to employ these engineers in this enterprise, who could be part of it on different levels, be it working as researchers to develop technology or for what was to become Embraer or for the government itself” (Interview #13, AIT, 2017).

While many of these engineers joined the IRD as researchers to develop aerospace technological autonomy, many others joined Embraer or opened start-ups, such as Avibrás and Mectron, based on the research developed at the IRD. Additionally, some engineers left Embraer and started their businesses as Embraer’s suppliers. State’s efforts establishing the ATC, AIT, and the IRD, therefore, set the stage for the formation of SJC STC. One participant claimed, “Everybody with an aerospace company here was from the IRD, the AIT, Embraer, or the NISR [National Institute for Space Research]. The majority comes from these institutions and Embraer” (Interview #20, NISR, 2017). Another participant added, “The Technology Park has around 100 firms, many related to the AIT because they were founded by the AIT’s alumni. Many aerospace companies in SJC were founded by the AIT’s former students, such as Avibrás and Mectron” (Interview #12, 2017).

Beyond the confines of the private sector, AIT alums and former Embraer employees also expanded their presence in SJC by occupying positions within state institutions and not-for-profit organizations. As the aerospace sector gained relevance in SJC, the local state came to see this as an opportunity for economic development, establishing institutions intended to attract or support aerospace firms to the region such as the Technology Park and the SJC Secretary of Economic Development. Other institutions also emerged, such as the Brazilian Association of Aerospace Industry, and CECOMPI, a not-for-profit organization designed initially to support aerospace SMEs (small and medium enterprises) and start-ups. The foundation and main managing positions within these institutions are mostly held by the AIT’s alums. One participant from SJC government stated, “In SJC, it is common to employ AIT alumni and find them working in many institutions. I think this is because we have the technical skills and understand the aerospace sector, and there is also the AIT element . . . We support each other” (Interview #5, 2022). Another added, “Many institutions here were founded by AIT graduates such as CECOMPI. We (SJC) had to come up with institutions to support aerospace SMEs, especially because we were too dependent on Embraer” (Interview #11, CECOMPI, 2017).

Henceforth, the Brazilian state’s efforts in the creation of institutions, regional assets, and Embraer resulted in a community of professionals employed in different segments of SJC who share an educational or professional background. This is due to significant spin-offs across multiple institutions and firms. One representative from the AIT asserted,

Look at the director of CECOMPI, Marcelo; he is the dean of the AIT and a former student in our master’s degree program. Look at SJC Secretary of Development, Cavalli; he was the dean of the AIT and a former student. Look at the SJC Technology Park director, Horácio Forjaz; he is an AIT’s former student and a former director at Embraer. Look at Tozi, the dean of FATEC; he coordinates the expansion team at the AIT. Embraer and Avibrás founded by AIT’s former students. (Interview #9, AIT, 2016)

One important feature of SJC STC regards how it is marked by a sense of belonging and a common set of beliefs that encourage relative symmetrical and cooperative relationships. According to some participants, this sense of belonging relates to Brazil’s aerospace project in SJC and how it resulted in the common educational and professional background previously described. One participant stated, “We see each other as if we were part of a club, and this is because we came from the AIT or worked for Embraer. We trust each other because we were born from the same state initiative and share a history, a bond” (Interview #8, São Paulo Secretary of Development, 2017).

SJC STC also shares a set of beliefs, which can be linked to the Brazilian national developmentalism ideology. The state's efforts to develop domestic aerospace technology in SJC were led by a national plan termed Strategic Plan of Development, which promoted state-led economic growth through investments in infrastructure, education, and domestic industry (Bresser-Pereira Citation2018). This belief, that is, the importance of the state in supporting economic development, is a common feature found in SJC STC. For example, one participant stated, “The private sector was not interested or had the power. […] So, we needed a strong government to kickstart our industry, and still needs it supporting our economy (Interview #9, AIT, 2016). Another interviewee claimed, “Our common understanding is the state is still required. State with investments, universities with training and research, and the private sector with jobs” (Interview #11, CECOMPI, 2017).

Additionally, the Brazilian developmental state focused on discourses around nationalism, which emphasized the necessity of cooperation around common national goals (Bresser-Pereira Citation2018). In the case of SJC indigenous coupling, local actors embraced Embraer’s establishment as part of this collective national project in which cooperation toward a common good was required (Araujo Citation2013). This sense of belonging and a shared set of beliefs (importance of state intervention and cooperation for the purpose of economic development) have encouraged SJC STC to have relative symmetrical and cooperative relationships, where public–private initiatives are often articulated and fostered through collaboration. One participant said, “Here in SJC, we have a strong sense of unity that goes back to the 60s when the state had this big vision. The ATC, AIT, IRD, and Embraer were all integrated with the government’s goals and purpose. We didn't really have much aerospace knowledge, so it required collective work, and we kept that spirit alive ever since” (Interview #10, AIT, 2017). Another participant from Embraer added,

These things (partnerships) happen naturally because one (Embraer) is the son of the other (the AIT). You have professors from the AIT as academic advisors and co-advisors from Embraer coming with the company’s problems, and this comes from our DNA. So, our (Embraer’s) interaction with the AIT is very easy because we have the same way to teach classes; we were a state-owned firm and part of the Brazilian Airforce. The guy from the AIT, who helps me to coordinate the program, was my professor at the AIT. I know him for 40 years. It is a student-professor relationship. (Interview #7, Embraer, 2017)

Therefore, due to the Brazilian developmental state aerospace project, SJC STC interacts and articulates initiatives through relative symmetrical and cooperative relationships with aerospace firms, state managers, educational institutions, and not-for-profit organizations. Interview #8 (2017), a São Paulo state representative, mentioned how SJC STC works collectively: “Companies, educational institutions, the municipal government, they interact, they are all involved […] We don’t have problems with conflicting initiatives.”

Indigenous Coupling, Asymmetrical Relations, and Social Downgrading

As stated, there is a need to expand GPN studies regarding how indigenous coupling is often described as marked by relative symmetrical and cooperative relations, and therefore, unlikely to result in exclusions. This subsection explores how a process of social downgradingFootnote5 evolved in SJC, and how asymmetrical power relations emerged in the context of Embraer’s adopting a new managerial logic and the Brazilian state’s changing its model of development.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Brazil underwent significant changes, including the restoration of democracy and the rise of neoliberalism (Braga Citation2017). In the 1990s, Brazil adopted a post-Fordist, peripheral, and financialized model of development that led to the adoption of neoliberal policies such as dismantling regulatory rigidity, privatization of state-owned companies, and decreased protectionism (Braga Citation2017). This accumulation strategy led to Embraer’s privatizationFootnote6 during Fernando Henrique Cardoso’s presidency in 1994, as the company had accumulated significant debt due to decreased sales and failed to improve its financial performance (Henrique Citation2012). Privatization led Embraer to transition from a management model where technical directives held centrality to a more profit-driven approach (Araujo Citation2013). Embraer reduced salaries, laid off thousands of employees, decreasing its workforce by 11 percent (17 percent of the total engineers), increased investment in production and outsourcing services, and changed its private governance with suppliers (Bernardes Citation2000).

Another important change was regarding Embraer’s internal training practices and relationship with educational institutions. Preprivatization, Embraer had a comprehensive internal training policy (Bernardes Citation2000). However, after privatization, the company shifted to external training, significantly reducing employees in the training department for technical courses from 107 workers in 1990 to only 3 in 1996 (Bernardes Citation2000). Therefore, following its privatization, Embraer changed its focus toward external training, with internal training gradually decreasing (Bernardes Citation2000). Given the cyclical nature of the aerospace industry, Embraer has “an annual turnover rate of 3 percent with over 150 engineers being hired every year” in SJC (Interview #7, Embraer, 2017); therefore, training remained a critical aspect of the company's operations. Consequently, Embraer increased its collaboration with local educational institutions to meet its skills needs.

As the Brazilian state’s support on some strategic sectors continued, Embraer, after its privatization, was able to access public funding investments and incentives from the National Bank for Economic and Social Development to manufacture airplanes for international buyers, resulting in numerous global sales of the ERJ 145 airplane at the end of the 1990s. Moreover, the Brazilian government created a special tariff regime allowing the company to import tax-free aerospace parts, further strengthening its global competitiveness (Catermol Citation2010). Given that, Embraer went from having financial losses to becoming one of the world's leading aerospace companies within two years after its privatization.

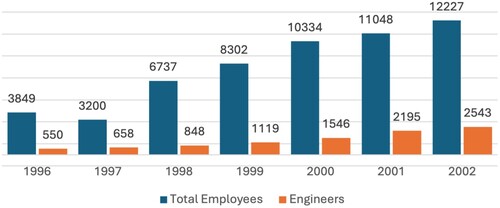

This required Embraer to hire more workers (), including aeronautic engineers (in addition to the turnover rate previously mentioned) (Zulietti Citation2006). However, as some participants stated, from 1996 to 2000, Embraer faced a shortage of aeronautic engineers, leading to hiring engineers from various fields, who required months of on-the-job training to acquire aerospace-related skills and the “Embraer way to work.” One participant described the changes Embraer underwent in the 1990s as follows:

In the 1990s, we fired many employees, decreasing to 4,000 employees, but before (privatization) we had almost 20,000 employees. So, after privatization, Embraer started to sell airplanes and obtained great success in the short term. So, the company could not find enough skilled people to hire. (Interview #7, Embraer, 2017)

To address this skill gap, a former Embraer’s CEO proposed to the AIT the creation of a short-term highly customized course for nonaeronautic engineers to acquire aerospace skills, thereby reducing on-the-job training. As stated, relative symmetrical relationships are based on some measure of mutual dependency and interest (Coe and Hess Citation2011): the AIT had its own strategic goals with this partnership, that is, to work with Embraer to maintain its courses’ curriculums updated, to attract students to its program, keeping it relevant, and develop research (Interview #10, AIT, 2017). One AIT participant explained the creation of the partnership:

At the time, a former CEO of Embraer said, “Besides not being able to recruit aeronautic engineers in the market, I lose too much time training on-the-job getting workers unfamiliar with aeronautics.” So, the goal was to have workers trained before hiring them. […] So, he said, “we need a program that helps all engineers to have a minimum common base (in aeronautics) […] to learn the ways of Embraer. (Interview #13, AIT, 2017)

In 2000, the Program of Specialization in Engineering (PSE) was established, emerging organically from the relative symmetrical and cooperative relationships rooted in SJC aerospace indigenous coupling. AIT alums founded Embraer, and a significant proportion of Embraer’s engineers today also obtained their degrees from this institution. As a result, a strong synergy exists between both, marked by a shared predisposition for interaction, cooperation, and collaborative projects. One participant claimed, “The program evolved instinctively. Embraer and the AIT have similar ways of thinking, and, of course, mutual interests. This makes partnerships flow easily” (Interview #10, AIT, 2017). For instance, when an AIT representative was asked about the nature of the respondent’s interactions with Embraer, the respondent stated,

With Embraer, it is easier to cooperate because many of Embraer’s employees are the AIT alumni. When these employees have needs, they know whom to look for at the AIT. There is no need to bring Embraer and the AIT together. This is natural. (Interview #12, AIT, 2017)

In this context, despite Embraer's transition from a state-owned enterprise to a private, profit-driven international corporation, the AIT continues to support the company as if Embraer were still a part of the former national developmental project. One AIT representative stated, “In reality, Embraer is just collaborating with the AIT in an activity that the AIT is doing because it is in the interest of the state, Embraer is cooperating, but who financially sustains the program is the government” (Interview #10, AIT, 2017). When queried about similar training partnerships with other corporations, AIT representatives asserted the institution's purpose was to benefit the aeronautic sector and, by extension, Embraer. One participant claimed,

Companies come to us to establish training partnerships, but the AIT is uninterested. With Embraer, we do because our mission is to work in this sector; after all, we are the AIT. Although we have other specializations, they are all focused on aeronautics. (Interview #13, AIT, 2017)

While the establishment of this partnership between Embraer and the AIT was based on relative symmetrical relations, it also illustrates how asymmetrical relations in indigenous coupling can emerge and foster social downgrading, particularly regarding labor conditions and workforce dynamics. Two examples can illustrate this dynamic.

While the PSE began in 2000 as a short three-month training initiative offering a certificate degree, where students would receive salaries as engineers while in training, in 2001, the AIT proposed transitioning to an eighteen-month vocational program with a master's degree. This longer training would entail higher salary costs for Embraer, prompting the AIT to suggest stopping hiring students as engineers during training and having them as apprentices (see ). To make long-term training viable, the AIT committed to providing Embraer's students with a federal monthly scholarship, which, when combined with their apprentice salary (third phase), would reduce Embraer's costs related to salaries and labor contract taxes and benefits. One AIT representative articulated,

The first group of students, Embraer hired as engineers, but someone from Embraer suggested having students as trainees. Then I said “You are behaving like a fool. If these students are engineers, why don’t you typify them as students, and so, you pay them as students and not as engineers? You (Embraer) pay what the government pays as a scholarship to master’s degree students. This way, you won’t have to spend on payroll taxes and labor contract benefits.” […] Then I added “We can turn this training initiative into a vocational master’s degree program. These engineers will then be typified as students from the AIT, studying full time, but also as an apprentice of Embraer. In this way, you (Embraer) can have very low-cost training. (Interview #13, AIT, 2017)

Table 1 Program of Specialization in Engineering

Therefore, in 2001, the PSE was relaunched as a vocational master’s degree program. These changes were financially beneficial for Embraer but detrimental to workers, revealing asymmetrical power relations. Embraer, utilizing the PSE, managed to decrease labor expenses, including salaries and payroll taxes by reclassifying engineers as apprentices, leading to lower remuneration, reduced benefits, and diminished social standing. Moreover, Embraer reduced training costs with the PSE, as one representative from the AIT claimed, “Embraer invests in the PSE, but many times, what Embraer is investing does not pay even 5 percent of what the company should pay” (Interview #10, AIT, 2017). shows the lowest wage paid by companies in SJC for aeronautic engineers each year and how much lower the PSE scholarship is, an average of 40 percent less. Additionally, the PSE undermines the value of engineers’ qualifications by increasing their workload, since in the third phase, students work full time and also have to develop a master’s thesis that aims at addressing an issue within Embraer.

Table 2 Lowest Wages (BRL R$) for Aeronautic Engineers in SJC versus the PSE Scholarship

Another social downgrading example regards how the PSE was, and still is, used as a form of precarization of work through which Embraer replaces senior and highly paid engineers with new young and highly qualified hires who are often single and without connections with unions,Footnote7 thereby undermining collective labor power within the company. This approach allows Embraer to lower wages and reduce labor costs, resulting in increased profitability at the expense of workers’ employment conditions. With the privatization of Embraer in 1994, the company changed its remuneration system. As a state-owned company, Embraer had a remuneration system based on the length of service and employees’ experience, where senior engineers’ salaries were higher than those of the newly hired. As a private enterprise, the company adopted a competency-based remuneration system based on two criteria: individual qualification attainment and employees’ collective accomplishment of predetermined financial aims set in Embraer's Action Plan and Sectoral Goals Plan (Moraes Citation2017). This change resulted in declining wages and wage progression for new hires (Zulietti Citation2006). As Bernardes (Citation2000) demonstrates, following the privatization, Embraer deliberately fostered a decline in the real wages of its employees Additionally, the author revealed that the wages paid by Embraer were much lower than its international competitors (for in-depth detail, see Bernardes Citation2000). One participant stated,

[T]he new CEO of Embraer (in 2000) targeted to reduce 200 million dollars in costs until things get better. Embraer has a problem, right? In other words, retirement costs related to its former remuneration plan. There are multiple ways to address this, but slowly, most of senior engineers are being replaced by engineers from our Program. (Interview #13, AIT, 2017)

In this regard, the PSE has been deployed to replace senior employees with high wages, who were under the previous remuneration system, with newly hired personnel who receive lower salaries. One participant mentioned, “The program brought some problems because long-term employees felt threatened. They were like, ‘There are all these new young employees, well-prepared, receiving lower wages than us’” (Interview #13, AIT, 2017). Another participant explained how the program was used to displace senior engineers:

[T]his is a matter of costs as well. The workforce is the main asset of Embraer . . . The company brings young skilled workers, creating internal pressure and replacing many workers. The company has senior engineers at the top of its career plan, and Embraer cannot maintain that. So, Embraer hires a skilled young engineer and replaces senior engineers. (Interview #10, AIT, 2017)

The PSE has become so entrenched that most of Embraer’s engineers attended it (see ). One AIT participant stated, “We trained through this program 1,500 students for Embraer. Soon we believe that at least 80 percent of all engineers at Embraer will be from the AIT” (Interview #10, AIT, 2017). The PSE aligns with Zulietti’s (Citation2006) research, which states that Embraer’s postprivatization hires brought a shift in the profile of engineers: They are younger, single, less adherent to unions, and more qualified, which matches the profile of PSE students/apprentices. To recruit students, Embraer uses the AIT institutional support to attract applicants countrywide rather than in the local labor market. Given that the AIT is portrayed as the best engineering school in Brazil, Embraer boosts its capacity to attract applicants and recruit the most qualified workers nationally. One Embraer participant asserted,

So, first, the AIT elaborates an admission exam and selects the best applicants. We decrease from 1,200 applicants to 200; after interviews, we recruit 30. At present, I have 3,680 applicants for 40 vacancies. The magic of the PSE is that we have a great power to attract young people who like engineering. (Interview #7, Embraer, 2017)

Table 3 Number of PSE Students per Year

To conclude, the PSE illustrates the contradictory nature of relationships in indigenous coupling, which can be marked by not only relative symmetrical relations but also asymmetrical, fostering social downgrading. First, the PSE contributes to the precarization of work by replacing senior, highly paid engineers with younger, highly qualified hires who receive lower wages. Second, the program's focus on recruiting younger, single, less union-adherent (to decrease collective power bargaining), and more qualified engineers exacerbates the internal pressure within the company, since long-term employees feel threatened by the influx of new hires who receive lower wages. Third, the PSE reclassifies engineers as students and apprentices to reduce labor and training costs. Therefore, Embraer increases its profitability at the expense of workers’ employment conditions.

Conclusion

Existing GPN literature primarily attributes the outcomes of strategic coupling to the power balance between place-based institutions and lead firms (Lim Citation2018). On the one hand, the dark side of strategic coupling is often associated with structural coupling, where asymmetrical relations prevail, and regions are in an inferior position when bargaining with lead firms due to the presence of generic assets, and how mobile firms play off different regions (Mackinnon Citation2012; Coe and Yeung Citation2015). On the other hand, mainstream literature often describes indigenous coupling as less likely to result in uneven outcomes due to the assumed presence of relative symmetrical, reciprocal, cooperative, and collaborative relationships. This assumption raised two questions: How do uneven outcomes evolve in indigenous coupling, and what territorial mechanisms are involved? In addressing these questions, three potential theoretical contributions can be highlighted.

The first contribution concerns the proposed notion of an STC as one key territorial mechanism in indigenous coupling. As demonstrated in SJC, different from the regular transnational community depicted in the GPN studies (see Yeung Citation2009), the state has a more direct role in STCs than just courting the return of global professionals. The state initiated the formation of an STC by creating institutions, such as the AIT, IRD, and Embraer, which coevolved and later resulted in substantial private and institutional spin-offs. In this process, SJC STC members ended up occupying important positions within state institutions, not-for-profit organizations, and firms as well as with a strong sense of belonging based on their educational and professional backgrounds as AIT alums and former Embraer employees. Additionally, an STC differs from a typical transnational community as its actions are also driven by the state rather than solely self-interest in establishing their own companies and links with global firms. As discussed, SJC STC played a crucial role in indigenous coupling in SJC, advancing the interests and goals of the state in processes related to establishing firms, such as Embraer, institutions, and regional assets, remaining still relevant today when it comes to harnessing assets. These initiatives can happen through direct action or intermediating collaboration among SJC STC members.

The second contribution revolves around how the notion of an STC can serve as a valuable resource to elucidate the (a)symmetrical and cooperative characteristics inherent in relationships characterized by indigenous coupling, a topic not much explored in the GPN literature. As argued in this article, SJC STC often acts according to the state's interests due to how its formation was related to a state aerospace project under a national developmentalism ideology that has imprinted a collective belief to SJC STC members regarding the state's pivotal role in development. Moreover, it encouraged and still encourage close-knit relationships, relative symmetrical interactions, and collaboration among SJC STC members. This speaks directly to the third contribution of this article.

The third contribution of this article pertains to how the notion of an STC can advance the comprehension of how uneven outcomes evolve in indigenous coupling. The article reveals that asymmetrical power relations can also be present in indigenous coupling. Key to understanding such asymmetrical relations, and how uneven outcomes evolve in indigenous coupling, regards how STCs may adopt ideologies or participate in collective state projects that are aligned with the interests of firms, excluding other actors such as labor. This was illustrated through how the PSE partnership fostered social downgrading in SJC.

This investigation opens the door to various avenues for future research. One promising direction is to conduct comparative studies across different regions to explore the concept of indigenous coupling and STCs in diverse settings. Moreover, these findings suggest a need to reevaluate and advance existing studies within mainstream literature regarding the territorial mechanisms involved in indigenous coupling at varying national and subnational contexts as well as concerning how uneven outcomes evolve.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank Tod Rutherford, Erika Faigen, Roseline Wanjiru, Oliver Hunt, and Gavin Bridge for their constructive feedback and suggestions. I am also grateful to the editors and anonymous peer reviewers.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

1 This also encompasses regions’ modes of economic development and states’ macropolitical structures (Coe and Yeung Citation2015).

2 This shared set of beliefs is among the individuals who are part of the STC and should not be generalized to the institutional level.

3 The Brazilian state is based on federalism with federal, state, and municipal governments. When pertinent and for the sake of clarity, the federal government will be approached as the national state, São Paulo state level as subnational, and São José dos Campos as the local state.

4 Industrial cluster has been under critique as a problematic concept (Martin and Sunley Citation2003). This article uses this term just as a practical way to describe the existence of an agglomeration of aerospace-related firms and institutions in SJC.

5 It is approached as a process where working conditions, labor rights, and social standards for workers in GPNs deteriorate (Bernhardt and Pollak Citation2016).

6 The federal government kept a golden share with a right to veto decisions in ownership control. Brazil kept a 20 percent stake; Bozano Bank Simonsen acquired 16.2 percent; Previ pension funds and Sistel had a 9.8 percent each; and other private pension funds had a total of 9.9 percent (Teles and Dias Citation2022).

7 While the article explores Embraer’s action to weaken the role of labor unions within the firm by hiring nonunionized workers as a process of social downgrading, it should be noted that such an action was part of a broader neoliberal shift in Brazil in the 1990s, which weakened labor union power (Scoleso Citation2009).

References

- Adams, W. C. 2015. Conducting semi-structured interviews. In Handbook of practical program evaluation, ed. K. E. Newcomer, H. P. Hatry, and J. S. Wholey, 492–505. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Araujo, V. L. T. 2013. Social death of an elite professional group: Embraer's engineers in the company restructuring process. Cadernos CERU 24 (2): 215–24.

- Bair, J., and Werner, M. 2011. Commodity chains and the uneven geographies of global capitalism: A disarticulations perspective. Environment and Planning A 43 (5): 988–97. doi:10.1068/a43505.

- Bernardes, R. 2000. O Caso da Embraer – privatização e transformação da gestão empresarial: Dos imperativos tecnológicos à focalização no mercado [The case of Embraer –privatization and transformation of its business management: From its technological imperatives to its focus on the market]. Cadernos de Gestão Tecnológica 46. http://www.fundacaofia.com.br/pgtusp/publicacoes/arquivos_cyted/cad46.pdf.

- Bernhardt, T., and Pollak, R. 2016. Economic and social upgrading dynamics in global manufacturing value chains: A comparative analysis. Environment and Planning A 48 (7): 1220–43. doi:10.1177/0308518X15614683.

- Braga, R. 2017. A rebeldia do precariado: trabalho e neoliberalismo no Sul global [The rebellion of the precariat: Labor and neoliberalism in the Global South]. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial.

- Bresser-Pereira, L. C. 2018. Economic nationalism and developmentism. Fiscaoeconomia 2 (1): 1-27. https://doi.org/10.25295/fsecon.2018.s1.001.

- Bruno, M. 2005. Crescimento econômico, mudanças estruturais e distribuição: As transformações do regime de acumulação no Brasil [Economic growth, structural changes and distribution: The transformations in the regime of accumulation of Brazil]. PhD diss., Federal University of Rio de Janeiro. https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/1551.

- CAGED - Cadastro Geral de Empregados e Desempregados [General Registration of Employed and Unemployed]. 2004–19. http://pdet.mte.gov.br/novo-caged.

- CAPES - Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior [Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Education Personnel]. 2023. https://www.gov.br/acessoainformacao/pt-br.

- Catermol, F. 2010. O BNDES e o Apoio às Exportações [BNDES and export support]. In O BNDES em um Brasil em Transição [BNDES in a Brazil in transition], ed. A. C. Além and F. Giambiagi. Rio de Janeiro: BNDES.

- Coe, N. M., and Hess, M. 2011. Local and regional development: A global production network approach. In Handbook of local and regional development, ed. A. Pike, A. Rodriguez-Pose, and J. Tomaney, 128–38. London: Routledge.

- Coe, N. M., and Yeung, H. W-c. 2015. Global production networks: Theorizing economic development in an interconnected world. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Coe, N. M., Hess, M., Yeung, H. W-c., Dicken, P., and Henderson, J. 2004. ‘Globalizing’ regional development: A global production networks perspective. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 29 (4): 468–84. doi:10.1111/j.0020-2754.2004.00142.x.

- Coimbra, A. C. M., and Hopfer, K. R. 2017. The technological pole of São José dos Campos: A critical analysis of its public municipal policy. Revista Brasileira de Planejamento e Desenvolvimento 6 (2): 313–38. doi:10.3895/rbpd.v6n2.5645.

- Dawley, S., Mackinnon, D., and Pollock, R. 2019. Creating strategic couplings in global production networks: Regional institutions and lead firm investment in the Humber region, UK. Journal of Economic Geography 19 (4): 853–72. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbz004.

- Embraer. 2022. Embraer annual report. https://daflwcl3bnxyt.cloudfront.net/m/43b8af71c07ce685/original/OS_16747_Embraer_RelatorioAnual2021_Horizontal_Indicadores_EN_6.pdf.

- Fernandes, D. P. 2018. Quanto custa um funcionário e todos os encargos trabalhistas envolvidos? [How much an employee costs and what are all the payroll taxes involved?]. Treasy, February 28, 2018. https://www.treasy.com.br/blog/encargos-trabalhistas/.

- Fonseca, P. V. D. R. 2012. Embraer: um caso de sucesso com o apoio do BNDES [Embraer: A success story with the support of BNDES]. Revista do BNDES 37 (June): 39–66.

- Forjaz, M. C. S. 2005. The origins of Embraer. Tempo Social 17 (1): 281–98. doi:10.1590/S0103-20702005000100012.

- Fu, W., and Lim, K. F. 2022. The constitutive role of state structures in strategic coupling: On the formation and evolution of Sino-German production networks in Jieyang, China. Economic Geography 98 (1): 25-48. doi:10.1080/00130095.2021.1985995.

- Fuller, C., and Phelps, N. A. 2018. Revisiting the multinational enterprise in global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography 18 (1): 139–61. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbx024.

- Gong, H., and Hassink, R. 2019. Co-evolution in contemporary economic geography: Towards a theoretical framework. Regional Studies 53 (9): 1344–55. doi:10.1080/00343404.2018.1494824.

- Harris, J. 2009. Statist globalization in China, Russia and the Gulf States. Science & Society 73 (1): 6–33. doi:10.1521/siso.2009.73.1.6.

- Harris, J. 2012. Outward bound: Transnational capitalism in China. In Financial elites and transnational business: Who rules the world?, ed. G. Murray and J. Scott, 200–41. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Hassink, R. 2021. Strategic cluster coupling. In The globalization of regional clusters: Between localization and internationalization, ed. D. Fornahl and N. Grashof, 15–32. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Henderson, J., Dicken, P., Hess, M., Coe, N., and Yeung, H. W-c. 2002. Global production networks and the analysis of economic development. Review of International Political Economy 9 (3): 436–64. doi:10.1080/09692290210150842.

- Henrique, M. A. 2012. A industrialização do município de São José dos Campos-SP: uma abordagem a partir da história econômica local [The industrialization of São José dos Campos-SP: An approach from local economic history]. Final Course Work (Specialization)–Federal Technological University of Paraná, Curitiba. https://repositorio.utfpr.edu.br/jspui/handle/1/21481.

- Henrique, M. A., and Ricci, F. 2012. Industrialização e capital estatal: Um estudo de desenvolvimento regional em São José dos Campos-SP [Industrialization and state capital: A study of regional development in São José Dos Campos-SP]. Caminhos de Geografia 13 (43): 255–63. doi:10.14393/RCG134316607. https://seer.ufu.br/index.php/caminhosdegeografia/article/view/16607.

- Hess, M. 2018. Global production networks. In The international encyclopedia of geography: People, the earth, environment, and technology, ed. D. Richardson, art. 0675. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

- Horner, R. 2017. Beyond facilitator? State roles in global value chains and global production networks. Geography Compass 11 (2): art. e12307. doi:10.1111/gec3.12307.

- IBGE. n.d. São José dos Campos. https://cidades.ibge.gov.br/brasil/sp/sao-jose-dos-campos/panorama.

- ITA. n.d. The Instituto Tecnológico de Aeronáutica [Technological Institute of Aeronautics]. https://www.pgfis.ita.br/.

- Indraprahasta, G. S., Derudder, B., and Hudalah, D. 2019. Local institutional actors and globally linked territorial development in Bekasi district: A strategic coupling? Singapore Journal of Tropical Geography 40 (2): 219–38. doi:10.1111/sjtg.12269.

- Jessop, B. 1990. State theory: Putting the state in its place. Cambridge: Polity.

- Jessop, B. 2001. Institutional re(turns) and the strategic–relational approach. Environment and Planning A 33 (7): 1213–35. doi:10.1068/a32183.

- Jessop, B., and Sum, N. L. 2006. Beyond the regulation approach: Putting capitalist economies in their place. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar.

- Ji, Q., Liu, W., Song, T., and Gao, B. 2022. The social barrier of strategic coupling: A case study of the Letpadaung copper mine in Myanmar. Land 11 (6): 1–19.

- Lim, K. F. 2018. Strategic coupling, state capitalism, and the shifting dynamics of global production networks. Geography Compass 12 (11): art. e12406.

- McGregor, N., and Yeung, G. 2022. Strategic coupling, path creation and diversification: Oil-related development in the ‘Straits Region’ since 1959. The Extractive Industries and Society 11 (September): art. 101085.

- MacKinnon, D. 2012. Beyond strategic coupling: Reassessing the firm-region nexus in global production networks. Journal of Economic Geography 12 (1): 227–45. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbr009.

- Martin, R. and Sunley, P. 2003. Deconstructing clusters: Chaotic concept or policy panacea? Journal of Economic Geography 3 (1): 5–35. doi:10.1093/jeg/3.1.5.

- Moraes, L. C. G. 2017. On the wings of capital: Embraer, financialization, and implications for workers. Caderno CRH 30 (79): 13–31. doi:10.9771/ccrh.v30i79.19925.

- Munir, K., Ayaz, M., Levy, D. L., and Willmott, H. 2018. The role of intermediaries in governance of global production networks: Restructuring work relations in Pakistan’s apparel industry. Human Relations 71 (4): 560–83. doi:10.1177/0018726717722395.

- Murphy, J. T. 2019. Global production network dis/articulations in Zanzibar: Practices and conjunctures of exclusionary development in the tourism industry. Journal of Economic Geography 19 (4): 943–71. doi:10.1093/jeg/lbz009.

- Neilson, J., Pritchard, B., and Yeung, H. W-c. 2014. Global value chains and global production networks in the changing international political economy: An introduction. Review of International Political Economy 21 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/09692290.2013.873369.

- Oliveira, F. 2004. Critique to the dualistic reasoning: The platypus. São Paulo: Boitempo Editorial.

- PIT. n.d. Parque de Inovação Tecnológica São José dos Campos [São José dos Campos Park of Technological Innovation]. https://pitsjc.org.br/.

- Phelps, N. A., Atienza, M., and Arias, M. 2018. An invitation to the dark side of economic geography. Environment and Planning A 50 (1): 236–44. doi:10.1177/0308518X17739007.

- Robinson, W. I., and Harris, J. 2000. Towards a global ruling class? Globalization and the transnational capitalist class. Science & Society 64 (1): 11–54.

- Rosenthal, M. 2016. Qualitative research methods: Why, when, and how to conduct interviews and focus groups in pharmacy research. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning 8 (4): 509–16. doi:10.1016/j.cptl.2016.03.021.

- Rutherford, T., Murray, G., Almond, P., and Pelard, M. 2018) State accumulation projects and inward investment regimes strategies. Regional Studies 52 (4): 572–84. doi:10.1080/00343404.2017.1346368.

- Santos, E. C. 2015. Productive restructuring—From Fordism to flexible production in the state of São Paulo. In The new map of industrialization in the beginning of XXI century: Different paradigms for reading the territorial dynamics of the state of São Paulo, ed. E. Sposito, 201–45. São Paulo: Editora UNESP.

- Saxenian, A. 2002. Transnational communities and the evolution of global production networks: The cases of Taiwan, China and India. Industry and Innovation 9 (3): 183–202. doi:10.1080/1366271022000034453.

- Saxenian, A. 2006. International mobility of engineers and the rise of entrepreneurship in the periphery. WIDER Research Paper No. 2006/142. Helsinki: United Nations University World Institute for Development Economics Research (UNU-WIDER). https://hdl.handle.net/10419/63430.

- Schneider, B. R. 2013. O Estado desenvolvimentista no Brasil: perspectivas históricas e comparadas [The developmental state in Brazil: Historical and compared perspectives]. https://repositorio.ipea.gov.br/handle/11058/2034.

- Scholvin, S. 2022. Failed development in global networks, exemplified by extractive industries in Bolivia and Ghana. Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography 104 (2): 146–62. doi:10.1080/04353684.2021.1991237.

- Scoleso, F. 2009. Reestruturação produtiva e sindicalismo metalúrgico do ABC Paulista: as misérias da era neoliberal na década de 1990 [Productive restructuring and metallurgical unionism in the ABC Paulista region: The miseries of the neoliberal era in the 1990s]. PhD diss., Pontifical Catholic University of São Paulo.

- Selwyn, B. 2013. Social upgrading and labour in global production networks: A critique and an alternative conception. Competition & Change 17 (1): 75–90. doi:10.1179/1024529412Z.00000000026.

- Selwyn, B., Campling, L., Mezzadri, A., Baglioni, E., Miyamura, S., and Pattenden, J. 2023. Exploitation and global value chains., In Handbook of research on the global political economy of work, ed. M. Atzeni, D. Azzellini, A. Mezzadri, P. V. Moore, and U. Apitzsch, 126–36. Northampton, MA: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Silva, O. 1999. The takeoff of a dream (The story of the creation of Embraer). 2nd ed. São Paulo: Lemos Editorial.

- Sklair, L. 1998. The transnational capitalist class and global capitalism: The case of the tobacco industry. International Political Science Review 23 (2): 159–74. doi:10.1177/0192512102023002003.

- Sklair, L. 2002. The transnational capitalist class and global politics: Deconstructing the corporate-state connection. International Political Science Review 23 (2): 159–74. doi:10.1177/0192512102023002003.

- Smith, A. 2015. The state, institutional frameworks and the dynamics of capital in global production networks. Progress in Human Geography 39 (3): 290–315. doi:10.1177/0309132513518292.

- SMSJC Sindicato dos Metalúrgicos de São José dos Campos [Union of Metaworkers of São José dos Campos]. 2019. Com centenas de demissões na Embraer e crise da Boeing, sindicatos pedem que Bolsonaro vete venda [With hundreds of layoffs at Embraer and the Boeing Crisis, unions are calling Bolsonaro to veto the sale]. https://www.pstu.org.br/com-centenas-de-demissoes-na-embraer-e-crise-da-boeing-sindicatos-pedem-que-bolsonaro-vete-venda/.

- Souza, M. B. D. 2016. The spatial rescaling of the developmental state in Brazil. Mercator (Fortaleza) 15 (4): 27–46. doi:10.4215/RM2016.1504.0003.

- Teixeira, T. 2024. Variegated forms of corporate capture: The state, MNCs, and the dark side of strategic coupling. Global Networks 24: art. e12433. https://doi.org/10.1111/glob.12433.