The idea that a society or nation can be judged in terms of what it does for its weakest members is a truism that has been attributed to a variety of sources including Mahatma Ghandi, Dietrich Bonhoeffer and Pope John Paul II, who turns the moral maxim toward the unborn. The late Hubert H. Humphrey provides the fullest statement: ‘It is often said that the moral test of government is how that government treats those who are in the dawn of life, the children; those who are in the twilight of life, the elderly; those who are in the shadows of life; the sick, the needy and the handicapped.’

If a country’s net moral worth is to judged in terms of the health of its children, then for a first world country New Zealand’s standing is appalling: it has slipped dramatically since the early twentieth century when its infant mortality was among the lowest in the world. This was the era of the welfare state when there was free public health care. New Zealand’s family income was relatively high, bolstered by secure markets and record post-war prosperity. Its record began slipping in the second half of the century, yet by the 1970s it was still in the top third of all countries. Beginning in the late 1980s and especially since the 2000s, as a result of neoliberal welfare policies and low government spending on children New Zealand has slipped into the bottom third of all countries alongside India and Mexico.

The Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) report Doing better for children (2009) indicates that New Zealand ranked 29th out of 30 OECD countries. Dominic Richardson, co-author of the report, notes:

New Zealand needs to take a stronger policy focus on child poverty and child health especially during the early years when it is easier to make a long-term difference. Despite relatively good average educational performance, gaps in education between top and bottom performers are higher than they need be.

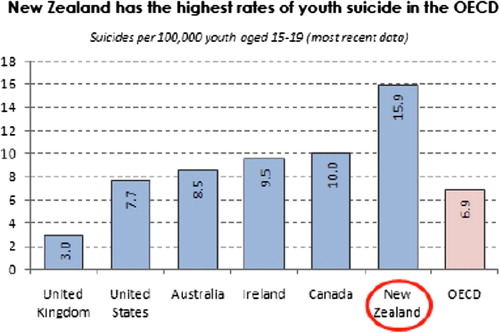

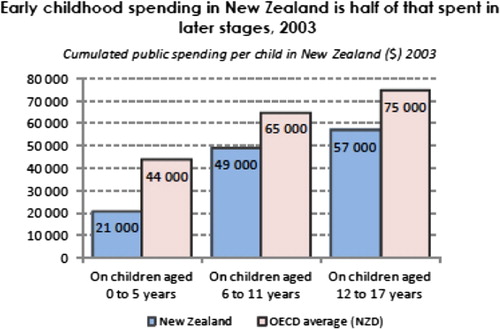

New Zealand has the highest youth suicide rate in the OECD, spends considerably less than the OECD average on young children and has among the poorest immunization rates.Footnote 1 The two graphs shown in are worth noting. It is the case that there has been some movement on government investment in children since 2009, although New Zealand’s ranking is still comparatively low.

As many publications have since noted, New Zealand’s child health patterns reflect those of a developing country rather than an advanced one for a whole range of criteria: infant mortality (5.1/1000 live births), children living in poor households (15 per cent of all children), overcrowded houses (31 per cent of all children), injury deaths (1–4-year-olds) and child diseases (rheumatic fever, whooping cough and pneumonia). Maori and Pacific Island children have roughly over 20 and 50 times, respectively, the risk of being hospitalized for various diseases such as rheumatic fever and tuberculosis than the NZ average.

In 2010 the Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG), a non-governmental organization formed in 1994, issued the paper Child poverty and child health. Failing our commitments to children in New Zealand in 2010 (Dale, St John, Asher, & Adam, Citation2010). This paper was published as a supporting paper for the Action for Children and Youth Aotearoa (ACYA) report to the United Nations Committee on the Rights of the Child, which noted that Aotearoa New Zealand failed to meet its commitments under the convention in a number of areas. The report noted:

The underlying issue is increasing income inequality and a consequent high number of children living in poverty and severe hardship, in poor housing conditions, with limited access to primary health care. Our research found that children from low income households in New Zealand are multiple times more likely to suffer from large variety of diseases than their more affluent peers. These inequalities are most evident in hospital admissions for relatively common diseases such as Rheumatic fever (28 times), Bronchiectasis (15 times), serious skin infection (5 times) and Tuberculosis (5 times). (p. 2)

The CPAG produced Left behind in 2008, describing the position of children in New Zealand (St John & Wynd, Citation2008). In 2011 the CPAG produced the monograph Left further behind: How policies fail the poorest children in New Zealand (Dale, O’Brien, & St John, Citation2011). The executive summary begins:

Three years later, the lack of substantial progress on so many issues facing children in this country leads us to rewrite and update that publication. In this report we reflect what is required to ensure all children have the resources and opportunities to grow and to develop their potential. Recent years and recent policy approaches have focused heavily on supporting, and sometimes forcing, parents (especially lone parents) into paid work. The needs and interests of children require a much broader approach. And in the interests of both children and parents, the work of caring for children needs to be given adequate recognition and support. Children’s wellbeing must be central, whether parents are in paid work or not. The core message of this publication is simple: ALL children, irrespective of the status and position of their parent/carer, are entitled to the best possible support from their parent/s and all New Zealand society. Together, we share responsibility for ensuring that children are given that support. While charity can make a useful contribution to assist and support children and families experiencing particular stresses, it cannot solve the problem of poverty, and poverty is the major problem facing around 200,000 New Zealand children. That solution requires collective action from families and communities; and it requires a commitment from the Government to make investing in our children the highest priority. (p. 1)

The coincidence between the introduction of neoliberal changes to welfare policies, the growth of income inequalities and low government spending on children has been noted also in the recent report for the Children’s Commissioner Child poverty in New Zealand (2012), which argues:

Child poverty rates rose sharply in the late 1980s and the early 1990s. During this period, inequality rose more in New Zealand than in any of the 20 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries for which comparable data is available. The key drivers were low wage growth for many working families, high unemployment and reductions in welfare payments. (p.1)

The Report argues that children have the right to a decent standard of living, which is a condition of their reaching their full potential and participating fully in society. The Report notes:

Poverty limits children’s daily lives and their opportunities and exposes them to the risks of illness, social and emotional damage, and poor educational attainment. Poverty experienced in the early years or for long periods casts a shadow over the future and can lead to long-term health problems, decreased potential for gainful employment and lower adult earnings. Children who grow up poor also have a higher chance that their own children will grow up poor. (Children’s Commissioner, Citation2012, Executive Summary)

The Report describes the consequences of child poverty in New Zealand and sets out the key data, including the number of children in New Zealand living in poverty based on accepted international relative poverty benchmarks. The results for 2006–2007 indicate:

Before taking account of housing costs:

| • | 210,000 children, or 20 per cent of all children, were below the 60 per cent threshold before housing costs are taken into account | ||||

| • | 140,000 (13 per cent) were below the stricter 50 per cent threshold before housing costs. | ||||

After taking housing costs into account:

| • | 230,000 children, or 22 per cent of all children, were below the 60 per cent of contemporary median income after housing costs threshold | ||||

| • | 170,000 (16 per cent) were below the stricter 50 per cent of contemporary median income after housing costs threshold. | ||||

One of the strengths of the report is that it is oriented towards positive solutions: ensuring adequate financial support for all families with children; making the child support system work better for children and parents; outlining ways of ensuring opportunities and adequate living standards for children; and the importance of setting goals and targets and monitoring progress towards ending child poverty.Footnote 2

Child poverty often goes hand in hand with other social problems including child homicides, physical neglect and abuse, and sexual and emotional abuse. The recent White Paper for vulnerable children (Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand Government, Citation2012) reveals ‘the sad reality’:

| • | Between seven and 10 children, on average, are killed each year by someone who is supposed to be caring for them. And in 2010, 209 children under 15 required hospital treatment for assault-related injuries. | ||||

| • | In the 12 months to 30 June 2012, 152,800 care and protection notifications were made to Child, Youth and Family. | ||||

After investigation, Child, Youth and Family found:

| • | 4766 cases of neglect | ||||

| • | 3249 cases of physical abuse | ||||

| • | 1396 cases of sexual abuse | ||||

| • | 12,114 cases of what social workers term ‘emotional abuse’, often children who have witnessed family violence. | ||||

| • | As at 30 June 2012, there were 3884 New Zealand children in out-of-home state care. | ||||

Social Development Minister Paula Bennett released the White Paper for vulnerable children on 11 October 2012 with the aim of targeting support and services to New Zealand’s 30,000 most at-risk children.

There have been some strong reactions against what is perceived to be a ‘punishment and monitoring’ approach rather than recognizing the important connections between child poverty and student achievement. While various groups have welcomed stronger data collection and moves to train teachers to recognize signs of abuse, many see the White Paper as ignoring the wider ecologies that exist between health and education and in particular the importance of eliminating poverty for all children as a measure that has ongoing life effects for the poorest children in both education and health.

Notes

1. For country highlights and specific information on New Zealand see ‘Country highlights’ at http://www.oecd.org/social/familiesandchildren/doingbetterforchildren.htm (OECD, Citation2009).

2. See also ‘This is how I see it: Children, young people and young adults’ views and experiences of poverty’ and ‘A Fair Go for all children: Actions to address child poverty in New Zealand’, downloadable from http://www.occ.org.nz/home/childpoverty/the_report (Children’s Commissioner, Citation2012).

References

- Children’s Commissioner (2012). Child poverty in New Zealand. Retrieved from http://www.occ.org.nz/home/childpoverty/the_report.

- Dale, C., O’Brien, M., & St John, S. (Eds.) (2011). Left further behind: How policies fail the poorest children in New Zealand. Auckland: Child Poverty Action Group. Retrieved from www.cpag.org.nz/assets/.../WEB%20VERSION%20OF%20LFB.pdf.

- Dale, C., St John, S., Asher, I., & Adam, O. (2010). Child poverty and child health. Failing our commitments to children in New Zealand in 2010. Auckland: Action for Children and Youth Aotearoa.

- Ministry of Social Development, New Zealand Government (2012). White Paper for vulnerable children. Retrieved from http://www.childrensactionplan.govt.nz/whitepaper.

- OECD (2009). Doing better for children. Retrieved from http://www.oecd.org/social/familiesandchildren/doingbetterforchildren.htm.

- St John, S., & Wynd, D. (Eds.) (2008). Left behind: How social & income inequalities damage New Zealand children. Auckland: Child Poverty Action Group. Retrieved from www.cpag.org.nz/assets/Publications/LB.pdf.