There is evidence and informed expert opinion that we are entering a coming age of pandemics where humanity is exposed to lethal and highly infectious bacterial or viral diseases that have the potential to decimate human populations. Already the science media are warning of ‘the next pandemic’ with a focus on secure food systems, disease hotspots, human/wildlife intersections, and crops diseases.Footnote1 ‘A World at Risk’ report (GPMB, Citation2019), of the Global Preparedness Monitoring Board, made the following warning in September 2019:

…there is a very real threat of a rapidly moving, highly lethal pandemic of a respiratory pathogen killing 50 to 80 million people and wiping out nearly 5% of the world’s economy. A global pandemic on that scale would be catastrophic, creating widespread havoc, instability and insecurity. The world is not prepared. (Foreword, p. 6).

The document argues for seven urgent actions to prepare the world for global health emergencies including investment in health infrastructures and ‘strong systems’ and leadership by regional and multilateral institutions with appropriate financial risk planning and development assistance.

The nature of the prophetic announcement and analysis in retrospect demonstrates two related principles: first, how badly prepared the world has been and how it has failed in general to be able to institute a ‘whole of society approach’ at national and global levels; second, how interconnected the world now is and how preparedness and treatment critically depends upon recognizing the whole-of-earth approach which speaks to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals and in particular aims of universal education and elimination of poverty.

One aspect that escapes the report that stands out in the middle of the Covid-19 health emergency is the politicization of the virus not only in terms of blame and responsibility but also in terms of libertarian politics that attempts to minimise the risks involved but talking up individual rights and fear of the state. This politicization has become more pronounced as the costs and the mismanagement of the Covid-19 threat has grown, especially in world states where national populism and contemporary forms of neo-fascism are potent political movements. It is the case that these movements are also associated with blaming tactics and conspiracy theories to deflect responsibility of administrations that have not well coordinated social distancing, basic hygiene, mask-wearing and other social isolation strategies in the name of collective welfare. That the current US administration under Donald Trump as should shy away from its welfare responsibilities at home and abroad indicates the international dangers of diseases spreading rapidly and compromises any global coordination responses. The real question is how to design a world health system of preparedness when rogue nation administrations do not want to join multilateral or world organisations tasked with protecting all peoples. The problem is highlighted in the often difficult relationship between science and science advice on the one hand and politics and policy, on the other. It is a question that has become now central to most of the related pressing global issues: the growing world arms race; world ecological disasters; world health emergencies and world economic development.

Laurie Garret (Citation2019), author of The Coming Plague: Newly Emerging Diseases in a World Out of Balance (1994), reports

In May 1989, Nobel laureate Joshua Lederberg gathered fellow Nobelists and a roster of extraordinary virus-hunters for a three-day meeting in Washington to consider a then bold hypothesis that viruses, far from being vanquished by modern medicine, were actually surging worldwide in animals and people, often in forms never previously seen. And air travel increasingly meant that an outbreak in an obscure location could spread to large cities, even make its way around the world. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/20/the-world-knows-an-apocalyptic-pandemic-is-coming/

Peter Daszak (Citation2020) suggests that we are entering a new pandemic era where an innocent activity like eating wildlife in one locality can, with global travel and encroaching development, lead to a pandemic. He indicates that the world’s disease hotspots on the edges of tropical forests provide the habitat for the diversity of wildlife that harbour an estimated 1.7 million viruses that become easily spread to humans. The ‘great acceleration’ of the Anthropocene has ‘dramatically altered our planet’s landscapes, oceans and atmosphere, transforming as much as half of the world’s tropical forest into agriculture and human settlements’.

In a recent paper ‘Emerging Pandemic Diseases: How We Got to COVID-19’ (August, 2020) published in the journal Cell, Anthony Fauci, working with his colleague, epidemiologist David Morens, both from National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID),Footnote2 also suggest that humanity has entered the pandemic age. They argue

In addition to … established infections, new infectious diseases periodically emerge. In extreme cases they may cause pandemics such as COVID-19; in other cases, dead-end infections or smaller epidemics result…Disease emergence reflects dynamic balances and imbalances, within complex globally distributed ecosystems comprising humans, animals, pathogens, and the environment. Understanding these variables is a necessary step in controlling future devastating disease emergences. https://www.cell.com/cell/fulltext/S0092-8674(20)31012-6?_returnURL=https%3A%2F%2Flinkinghub.elsevier.com%2Fretrieve%2Fpii%2FS0092867420310126%3Fshowall%3Dtrue

Fauci’s NIAID profile indicates he was appointed Director of NIAID in 1984 with the basic research goal ‘to prevent, diagnose, and treat established infectious diseases such as HIV/AIDS, respiratory infections, diarrheal diseases, tuberculosis and malaria as well as emerging diseases such as Ebola and Zika’. He advised six Presidents on HIV/AIDS. NIAID has an estimated $5.9 billion budget for 2020.Footnote3 His encounters as one of President Trump’s chief scientific advisors has provided a case study of the thin line between science and politics in the Covid-19 crisis that has regularly generated conflicts and conspiracies. Fauci has publicly disagreed with Trump on many issues. Trump has contradicted the best scientific advice and made claims not supported by the latest science. Now as the number of deaths in the US explodes above 215,000 with little sign of improvement, scientists globally have signalled the mismanagement of the viral crisis by the Trump government. Various scientific organisations have indicated that by January the US might be facing a death toll of over 410,000.Footnote4 One of the burning questions facing us during the Covid-19 pandemic is the science/politics interface. Many false conspiracy theories have been generated often deliberately to deflect responsibility, manipulate populations, and spread misinformation for political purposes. Science has a role to play not only through informing best policy advice, through modelling and evidence-based research but also in terms of scientific communication and public education. Now that Trump has contracted Covid-19 it seems little has changed in his behaviour as he has recently openly flouted social distancing and mask-wearing.

Significantly, Morens and Fauci (Citation2020) in their August paper look to the longer term and the future for global humanity, indicating: ‘Newly emerging (and re-emerging) infectious diseases have been threatening humans since the neolithic revolution, 12,000 years ago, when human hunter-gatherers settled into villages to domesticate animals and cultivate crops’. The historical long-run of 12,000 years is relatively short when compared to the evolution of viruses and the beginning of life on the planet. There is some theoretical disagreement about whether cells or viruses came first.Footnote5 The fact is that viruses have been around and co-evolved with cells over 3.5 billion years ago.Footnote6 Recently, with huge overcrowding and a projected world population of 10 billion people the environmental mix has radically changed with rapid and ongoing deforestation, the spread of urban slums and the growth of wet markets for wild game. Now environmental degradation has become one of the key determinants of disease emergence with outbreak hot spots where people, domestic animals, and wild animals are crowded together. Morens and Fauci (Citation2020) claim ‘Evidence suggests that SARS, MERS, and COVID-19 are only the latest examples of a deadly barrage of coming coronavirus and other emergences’. They continue

Since there are four endemic coronaviruses that circulate globally in humans, coronaviruses must have emerged and spread pandemically in the era prior to the recognition of viruses as human pathogens. The severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus (SARS-CoV) emerged from an animal host, likely a civet cat, in 2002–2003, to cause a near-pandemic before disappearing in response to public health control measures. The related Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (MERS-CoV) emerged into humans from dromedary camels in 2012, but has since been transmitted inefficiently among humans (Cui et al., Citation2019). COVID-19, recognized in late 2019, is but the latest example of an unexpected, novel, and devastating pandemic disease. One can conclude from this recent experience that we have entered a pandemic era (Morens, Breman, et al., Citation2020; Morens, Daszak, et al., Citation2020).

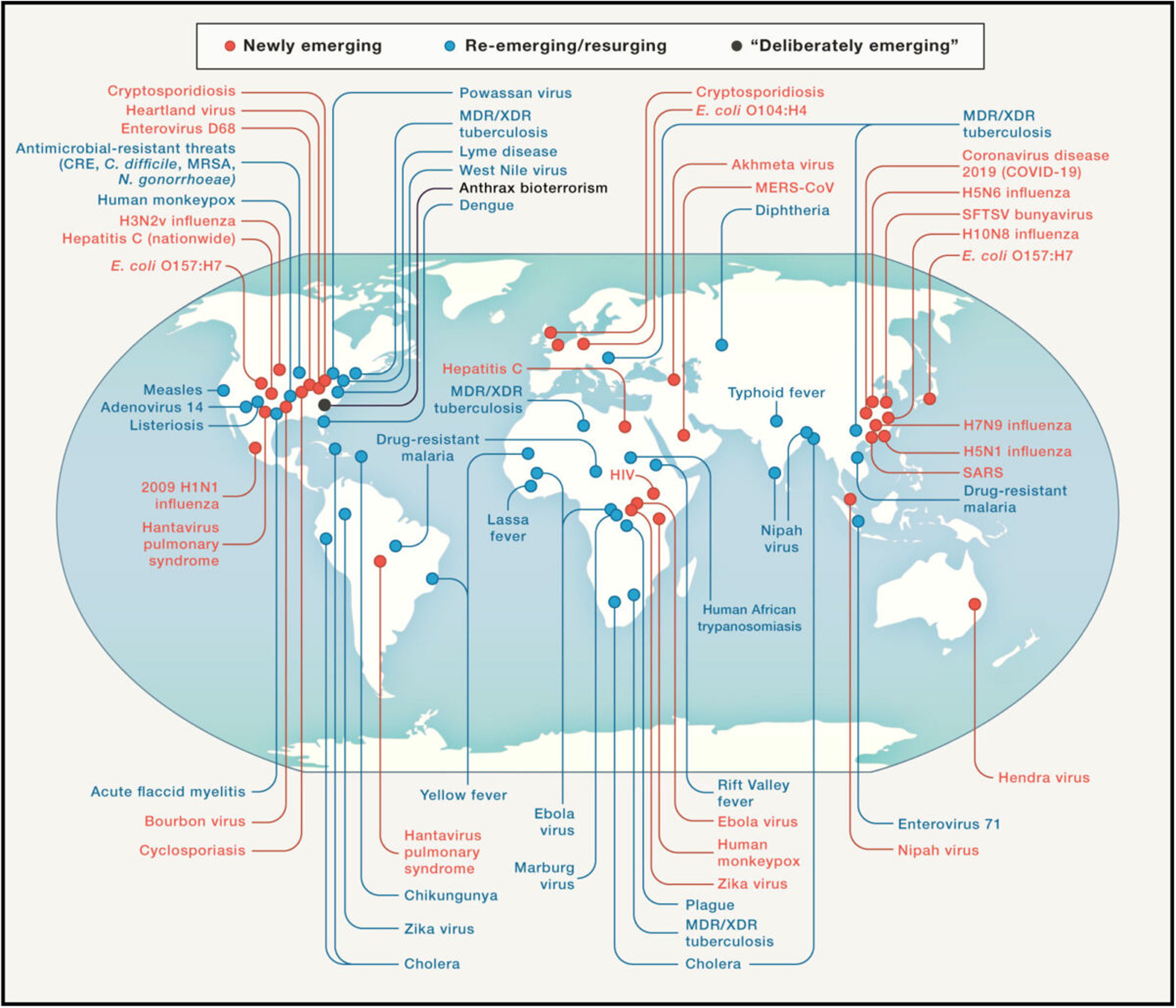

They provide a global map of newly emerging coronaviruses that can upset and disrupt ‘complex globally distributed ecosystems comprising humans, animals, pathogens, and the environment’. They argue that we must better appreciate the dynamic balances and imbalances in the global ecosystem understanding it as an evolving planetary system increasingly based on humanity’s ‘widespread manipulation of nature’.

Citing Richard Dawkins (Citation1976) they comment: ‘evolution occurs at the level of gene competition and we, phenotypic humans, are merely genetic “survival machines” in the competition between microbes and humans’. The implication is that we need to better understand the complex relationships between humans, animals and pathogens that determine the path of evolution, and the emergence of pandemic diseases brought on by rapid and irreversible destruction of delicate ecosystems comprising the environment.

The narrative is structured around a ‘doomsday clock argument’ suggesting that soon the Earth will reach a totally unsustainable global population that at the present rates of growth will consume, make extinct and exhaust, first, all other animal and insect life, while also increasing the risk from eating wild animals, and, second, the plant world, with the possibility of leading to the total extinction of life on Earth. This is a process fundamentally caused by human beings and, at this stage if we act quickly, the argument goes, it is still possible to prevent catastrophic pandemics by inventing and cultivating new eco-practices that are in ‘creative harmony’ with nature.

The imbalances in the global ecosystem result from climate warming will help cause large temperature change and massive fire destruction of native forest and bush environments, the loss and extinction of wild animal and insect populations, and also consequent flooding and sea erosion and low-lying coastal environments. In the short term it is necessary to prevent further deforestation and to outlaw wildlife trade in order to protect against future zoonosis outbreaks.

Andrew Dobson and his colleagues argue

For a century, two new viruses per year have spilled from their natural hosts into humans (1). The MERS, SARS, and 2009 H1N1 epidemics, and the HIV and coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemics, testify to their damage. Zoonotic viruses infect people directly most often when they handle live primates, bats, and other wildlife (or their meat) or indirectly from farm animals such as chickens and pigs. The risks are higher than ever … as increasingly intimate associations between humans and wildlife disease reservoirs accelerate the potential for viruses to spread globally (Dobson et al., Citation2020, p. 378).

They suggest that the rate of emergence of novel viruses and the costs of its economic impacts are increasing exponentially.

New research has highlighted the role domesticated animals – both pets and livestock – play in the spread of viruses among humans and wildlife. Konstans Wells et al. (Citation2019), who leads the Biodiversity and Health Ecology research group at Swansea University, is reported as saying:

Bats are commonly recognised as host of viruses that may eventually spillover into humans with devastating health effects, but the role of other mammalian groups and especially domestic species for the spread of virus are much less clear. Many of the current and future viral threads are linked to viruses that circulate in different animal species, connecting humans and mammal species into a huge network of who shares viruses with whom. https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/12/191219122521.htm

Wells et al. (Citation2019) and colleagues have traced the associations between 1,785 virus species and 725 mammalian host species to find that there is ‘strong evidence that beside humans, domestic animals comprise the central links in networks of mammalian host-virus interactions, because they share viruses with many other species and provide the pathways for future virus spread.’Footnote7

It has long be known that bats are a reservoir for viruses that through ‘viral host switching’ become the basis for the spread of new viruses. The evidence is quite unequivocal; some examples follow. Calisher and his colleagues, for instance, write

The remarkable mammals known as ‘bats’ and ‘flying foxes’ … may be the most abundant, diverse, and geographically dispersed vertebrates… Although a great deal is known about them, detailed information is needed to explain the astonishing variations of their anatomy, their lifestyles, their roles in ecosystems ecology, and their importance as reservoir hosts of viruses of proven or potential significance for human and veterinary health (Calisher et al., Citation2006, p. 531).

So-called ‘viral host switching’ and the increased rate of emergence of epizootic diseases is a major cause for alarm. Parrish et al. (Citation2008, p. 466) conclude

While it is still not possible to identify which among the thousands of viruses in wild or domestic animals will emerge in humans or exactly where and when the next emerging zoonotic viruses will originate, studies point to common pathways and suggest preventive strategies. With better information about the origins of new viruses, it may be possible to identify and control potentially emergent viruses in their natural reservoirs.

Narveen Jandu (Citation2020) argues ‘Human activity is responsible for animal viruses crossing over and causing pandemics’:

Viruses that circulate in other animals can enter a human population when a variety of human activities allow for consistent and regular interaction with naturally occurring reservoirs. These events involve repeated and routine interaction of humans with these animal hosts. Some of these interactions take place through the following human activities: hunting, butchering and farming (husbandry), as well as the global trade of animals and domestication of exotic animals as pets. Population growth, global travel and climate change that cause the disruption of habitats further provide opportunities for cross-species transfer. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-05-human-responsible-animal-viruses-pandemics.html

The Ebola outbreaks in West Africa are a result of human interaction with fruit bats either delivered directly or through animals hosts such as horses and pigs. It is clear that exploitation of wildlife and its huge multi-billion dollar market worldwide is leading to the loss of tropical forests and other natural habitats, exposing wildlife directly to humans with greater risks of viral spillovers. The risk of virus spillover from animals to humans has increased through wildlife exploitation and domestication.Footnote8 Wild animals and plants are rapidly disappearing especially through climate warming and consequent rampant and uncontrollable wild fires (Peters, Citation2020).

Now is the time to return to return to the story of the emergence of society to question the domestication narrative and its environmental practices that have been often devastating for the global ecosystem with the importation of micro-organisms and pathogens that accompanied colonialism and the expansion of modern agriculture under neoliberal capitalism, decimating native wildlife and indigenous peoples with introduced species and imported pathogens that destroyed delicate ecosystems in the ‘new world’. In historical terms it is timely to revisit the politics of the domestication narrative and its deleterious environmental effects from plantation agriculture to the modern use of chemicals. The emergence of new diseases brings into central question the mass extinction of species through factory-farming and the destruction of native ecosystems that become threats to global biodiversity and govern emerging industrial human-animal-plant interactions of the last hundred and fifty years, crowding out wild nature and redrawing the lines between human settlement and the global ecosystem.Footnote9 To understanding models of novel disease emergence, philosophically, we need return to the domestication narrative and it’s place in human history 10,000 years ago in Mesopotamia and to understand how human settlement, colonial expansion and modern agro-capitalist systems progressively have permanently disturbed the globally distributed ecosystems and accumulated genetic resources comprising humans, animals, plants, pathogens, and the environment. This complex cultural history needs to be re-examined in the light of viral evolution and the emergence of new diseases that signal that we are entering an era of pandemics.

Beijing Normal University, Beijing, PR China

[email protected] http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1482-2975

Notes

3 See his biography at https://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/anthony-s-fauci-md-bio

References

- Daszak, P. (2020). We are entering an era of pandemics – it will end only when we protect the rainforest. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/jul/28/pandemic-era-rainforest-deforestation-exploitation-wildlife-disease

- Calisher, C., Childs, J., Field, H., Holmes, K., & Schountz, T.. (2006). Bats: Important reservoir hosts of emerging viruses. Clinical Microbiology Reviews, 19(3), 531–545. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1128/CMR.00017-06

- Cui, J., Li, F., & Shi, Z. L.. (2019). Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 17, 181–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9

- Dawkins, R. (1976). The selfish gene. Oxford University Press.

- Dobson, A., Pimm, S., Hannah, L., Les Kaufman, L., Ahumada, J., Ando, A., Aaron Bernstein, A., Busch, J., Daszak, P., Engelmann, J., Kinnaird, M., Li, B., & Loch-Temzelides, T. (2020). Epidemic diseases. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews, 72(3), 457–470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1128/MMBR.00004-08

- Garret, L. (2019). The world knows an apocalyptic pandemic is coming. Foreign Policy. https://foreignpolicy.com/2019/09/20/the-world-knows-an-apocalyptic-pandemic-is-coming/

- GPMB. (2019). A world at risk. WHO.

- Jandu, N. (2020). Human activity is responsible for animal viruses crossing over and causing pandemics. https://medicalxpress.com/news/2020-05-human-responsible-animal-viruses-pandemics.html

- Morens, D. M., Breman, J. G., Calisher, C. H., Doherty, P. C., Hahn, B.H., Keusch, G.T., Kramer, L. D., LeDuc, J. W., Monath, T. P., and Taubenberger, J. K.. (2020). Origin and evolution of pathogenic coronaviruses. Nature Reviews Microbiology, 17, 181–192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1038/s41579-018-0118-9

- Morens, D. M., Daszak, P., and Taubenberger, J. K.. (2020). Escaping Pandora's Box – Another Novel Coronavirus. The New England Journal of Medicine, 382, 1293–1295. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp2002106

- Morens, D., & Fauci, A. (2020). Emerging pandemic diseases: How we got to COVID-19. Cell, 1077–1092 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.021.

- Parrish, C., Holmes, E., Morens, D., Park, E.-C., Burke, D., Calisher, C., Laughlin, C., Saif, L., & Daszak, P. (2008). Cross-species virus transmission and the emergence of new.

- Peters, M. (2020). Ecologies of fire. Educational Philosophy and Theory. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2020.1723464

- Wells, K., Morand, S., Wardeh, M., & Baylis, M. (2019). Distinct spread of DNA and RNA viruses among mammals amid prominent role of domestic species. Global Ecology and Biogeography, 2019, 470–481 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/geb.13045