Abstract

There is little room left for doubt or even debate at the severity of the ecological, indeed planetary crises that we find ourselves in during this period coined the Anthropocene. As educators working in the face of these crises, we have asked ourselves the question ‘how do we carry on?’ We reflect on a set of sensory, multimodal, meditative and arts-based pedagogical activities that bridge the geographical, biological, sociological and environmental dimensions of learning using the concepts from Hannah Arendt and John Dewey, in a higher-education context in Sweden. The first-cycle (undergraduate level) course in which these activities are conducted—Teaching sustainability from a global perspective - engages students in a range of pedagogical activities designed to encourage greater awareness of sustainability issues in diverse educational settings. In this paper we reflect on pedagogical practices as praxis in a sustainability focused course, and use the theory of practice architectures to question what people do in a particular time and place. We explore how educating for the future using multimodal and arts-based pedagogies could be a strategy to support new ways for reconfiguring environmental sustainability education in the Anthropocene.

Introduction

There is little room left for doubt or even debate at the severity of the ecological, indeed planetary crises that we find ourselves in (Pedersen et al., Citation2022). As educators working in the face of these crises, we have repeatedly asked ourselves the ‘how do we carry on?’ We reflect on a set of sensory, multimodal, meditative and arts-based pedagogical activities that bridge the geographical, biological, sociological and environmental dimensions of learning in a higher-education context in Sweden. We used parts of Hannah Arendt and John Dewey’s philosophies in devising the pedagogies we reflect on and start with the assumption that learning is a social practice. We concur with Marcia McKenzie who argues socio‐ecological learning does not (necessarily) occur via ‘cognitive critique or embodied place‐based experience, but rather as taking place in between the thought and the sensed via a range of inter- subjective experiences’ (McKenzie, Citation2008, p. 362). Thus, our reflections on both the pedagogies and the outcomes through participation in such pedagogical activities (i.e student submissions) are shaped by the theory of practice architectures (Kemmis et al., Citation2014; Kemmis & Grootenboer, Citation2008) to identify the ‘conditions of possibility for more sustainable educational practices for the future’ (Kaukko et al., Citation2021, p. 3).

The first-cycle (undergraduate level) course in which these activities are conducted—Teaching sustainability from a global perspective—aims to increase student’s ability to reflect on and centrally position, issues of sustainability across all forms of education and is built around three themes: ‘human activities and their impact on society and the environment; social participation and the politics of engagement; personal and curriculum values in relation to life on earth’ (GU, Citation2022, para. 7). The course explicitly focuses on teaching about aspects of sustainability in diverse settings, premised on the idea that the students involved have the capacity to encourage greater awareness of sustainability issues in a wide variety of people.

This article proceeds in four parts. In the next section we outline the immediate context in which these selected pedagogical activities were undertaken and the theoretical underpinnings that informed the planning of them. Following that we provide a brief description of three selected activities that formed part of the overall course and expand upon our methods. In the discussion section we provide a number of student (creative) works produced while participating in the pedagogical activities to illuminate and reflect upon the learning they articulated and we as teachers also experienced.

Context and theoretical background

We are two sustainability educators teaching, learning and thinking in a university setting who recognise ‘the messy terrain of the debates concerning the ‘Anthropocene’ and the ‘Capitalocene’ [and repeatedly ask] how does education emerge?’ (Pedersen et al., Citation2022, p. 224). Crutzen and Stoermer (Citation2000) posit that humanity itself has become an earth system that has had such vast ecological impact that a new geological epoch has commenced- the epoch known as the Anthropocene. We do not wish to enter the debate around the Anthropocene in this article, but as Haraway (Citation2015, p. 160) suggests we ‘think our job is to make the Anthropocene as short/thin as possible’. To help do that we recognise that education plays a role and ‘has the capacity to serve as a means to adapt to the impending environmental challenges of the current geological epoch’ (Lloro-Bidart, Citation2015, p. 128).

We also work in a university that has struggled to find footing on this ‘messy terrain’ of the Anthropocene, yet has been promoting the importance and centrality of sustainability and in particular Education for sustainable Development (ESD) across faculties (Omrcen et al., Citation2018). We work in an environment that recognises the importance of pluralistic traditions (Andersson, Citation2017) within universities that work from the ‘assumption that there are many different visions, approaches and pathways in approaching sustainability’ (Kopnina & Cherniak, Citation2016, p. 2). We agree with Helen Kopnina and Brett Cherniak (Citation2016) that one of our major concerns as educators is that we work in a space where:

the indoctrination into neoliberal values shaped by the dominant ideology of economic growth as a prerequisite of social development (Davies and Bansel Citation2007). Here is the point where supporters of pluralism in education branch out into those who promote openness of opinions as a panacea for neoliberal ideology, and those that are sceptical of all ideologies, including that of education for sustainability. (p. 3)

In fact as part of this push toward sustainability in 2020 the university’s International Office launched the inaugural ‘Summer School for Sustainability [which] is a chance to take action on sustainability and deepen…understanding of global challenges and the UN Sustainable Development Goals’ (GU, Citation2022, para. 1). The summer school offers ‘a programme of courses and activities to create synergy around sustainable solutions and encourage interdisciplinary collaboration’ from five different faculties from across the university, of which this course -Teaching sustainability from a global perspective - was offered by the Faculty of Education. In 2020, because it has been conceived as a cohort-based in-person summer experience, the first summer school was cancelled. However, because we had a) a number (n∼20) of enrolments of both international and local students, and b) we had successfully conducted the course online during the spring term previously, we were able to offer and conduct it as a freestanding course. As the pandemic related restrictions continued into 2021, the university moved the entire summer school online

In this context, designing learning experiences and teaching sustainability focussed courses we have, on the one hand, had a certain amount of freedom employing and trialling various pedagogies for sustainability courses. Yet on the other hand, and at the same time, we have struggled with the notion that we are embedded in the globalising economy that is accelerating unsustainability (Huckle & Wals, Citation2015). We have often wondered if we, as teachers and researchers working in a system of new public management, are merely only helping young people enter and remain in a system that trains them to be more effective vandals of the earth (Orr, Citation1994). And we have repeatedly asked ourselves the question is it possible to ‘cultivate multi-species approaches to knowledge and justice in a time of mass environmental pillage’ (Pedersen et al., Citation2022, pp. 225-226)?

Asking ourselves this question is not just, as Ramsey Affifi suggests, a matter of ‘seeking to deanthropocentrise environmental education’ (Affifi, Citation2020, p. 1435), although we recognise the inherent problems with ‘traditional’ anthropocentric pedagogies being used in educational settings (Kopnina & Cherniak, Citation2015; Pedersen, Citation2021). As sustainability teachers we must, however, recognise that our role is one that engages with humans who are inescapably living in the Anthropocene (Crutzen & Stoermer, Citation2000) and ‘we must design educational responses’ (Kaukko et al., Citation2021, p. 7) with that in mind. These activities are sustainability-focused in the sense that they are all designed to assist ‘young people to better understand themselves and their relations to others with whom they share the planet, human and other-than-human’ (Greenwood, Citation2014, p. 283).

When designing pedagogical activities in the Anthropocene we see an opportunity to recognise ‘anthropocentrism’s fluid binary’ (Affifi, Citation2020) and engage with ‘several (non)anthropocentric positions that can be considered in EE practice: multicentrism and noncentrism, process-oriented materialisms, anthropocentrism vs anthropomorphism, and experiential (non)anthropocentrism achieved through meditation’ (Affifi, Citation2020, p. 1438).

The pedagogical activities we share in this article were each designed to encourage the students (and the teachers!) to engage with Hannah Arendt’s provocative question ‘What are we doing?’ (Arendt, Citation1998, p. 5) in a world, where ‘thoughtlessness’ (Arendt, Citation1971, p. 423) is normalised. Laura Ephraim (Citation2017, Citation2021) has attempted to reconfigure previous Arendtian commentaries to ‘rethink the politics of earth’s appearances and resources for inquiring into the political value of biological life’ (Ephraim, Citation2021, p. 1) and suggests, that Arendt was concerned about the risk of ‘natural displays of diversity disappearing from public view’ (Ephraim, Citation2017, p. 36). These displays, Ephraim terms ‘gifts of appearance’ (p. 36), and argues that Arendt committed human responsibility to spectatorship of earthly creatures as being ‘inscribed in our bodies’ (Ephraim, Citation2017, p. 40) through, as Arendt wrote ‘the astounding diverseness of sense organs’ (Arendt, Citation1978, p. 20). Consequently, ‘(t)he ‘sensation’ of reality, of sheer thereness, relates to the context in which single objects appear as well as to the context in which we ourselves as appearances exist among other appearing creatures’ (Arendt, Citation1978, p. 51). Ephraim (Citation2017) argues that the aesthetic spectacles of the natural world birds, flowers, and other life-forms, from an Arendtian perspective are ‘valuable because they call us to take up our role as spectators’ (p. 41). Arendt suggests ‘on this level of being alive, appearance and disappearance, as they follow upon each other, are the primordial events’ (Arendt, Citation1978, p. 20). Hence, Arendt’s views of human senses and notions of earthly spectacle and human spectator underpin our pedagogies.

In designing and reflecting upon these pedagogical activities we have been cognisant of John Dewey’s concept of experience (Dewey, Citation1938/1997) but in particular his warning that although there is a genuine and necessary link between processes of actual experience and education we should not accept ‘that all experiences are genuinely and equally educative’ (Dewey, Citation1938/1997, p. 25). Dewey explained that each and every experience is ‘a moving force. Its value can be judged only on the ground of what it moves toward and into’ (p. 38). Thus ‘the immediate and direct concern of an educator is then with the situations in which interaction takes place’ (p. 45).

The theory of practice architectures (Kemmis et al., Citation2014; Kemmis & Grootenboer, Citation2008), developed by Stephen Kemmis and colleagues, provides a theoretical perspective that has helped us reflect on the pedagogies we outline in this article. The theory of practice architectures posits that what an individual does, and is able to do, is shaped by a wide variety of discourses, social and political relationships, and the resources or materials available (Kemmis et al., Citation2014). Kemmis and colleagues argue that learning is never a solitary affair, in any context but rather is inherently social, and where shared, communal, and intersubjective processes are influenced and formed by local histories.

The theory questions ‘what people do in a particular place and time’ (Kemmis, Citation2009, p. 23). A practice, argues Kemmis, is comprised of actions that have social, political and, importantly, moral consequences and might be considered ‘good’ when it forms and transforms the individuals that participate in it, and the world in which the practices occur (Kemmis, Citation2009; Kemmis et al., Citation2014). Practices occur as ‘characteristic arrangements of actions and activities (doings), are comprehensible in terms…of relevant ideas in characteristic discourses (sayings), and when the people and objects involved are distributed in characteristic arrangements of relationships (relatings)’ (Kemmis et al., Citation2014, p. 31).

Finally, and importantly this theory gives us a way to understand pedagogical practice as praxis. According to Kemmis and Smith (Citation2008) ‘praxis is what people do when they take into account all the circumstances and exigencies that confront them at a particular moment and then, taking the broadest view they can of what it is best to do, they act’ (p. 4). In a sustainability-focused class at the university level we are, like others particularly interested in critical educational praxis, which Mahon et al. (Citation2019) define ‘as a kind of social-justice oriented, educational practice/praxis, with a focus on asking critical questions and creating conditions for positive change’ (p. 464).

Materials and methods

The methodology for this article could be described, albeit loosely, as a form of practitioner reflection. It does, of course, include the thoughtful and theorised reflections of two teachers but it may be more aptly described as multi-layered critical reflective pedagogy. Our teaching is based on our reflective positions in the world and the course is educating for the world. Our meta-reflections are on the pedagogies we have engaged with students in together, as both a place and a space for reflecting on how we can ‘think what we are doing’ (Arendt, Citation1998) at this point in time. Our reflections also attempt to recognise the enabling and constraining arrangements within which sustainability pedagogies and practices can, and do, occur. We seek to answer questions concerning the persistence of the classroom as the default pedagogical space, and possibilities to make border-crossings between space and time to engage with worlds beyond the anthropocentric school.

Data collection

This paper not only shares personal pedagogical reflections of two teachers but more importantly it includes selected assignments from a variety of students who undertook the course during five separate iterations. The first time these activities occurred the students were physically on campus for class, the later occasions took place on Zoom due to the Covid 19 pandemic, thus our reflections on the activities consider the pedagogical differences afforded by these different forms of interaction between students and teachers. Data is drawn from each of the five iterations of this course ().

Table 1. Iterations of the course teaching sustainability from a global perspective.

Student submissions or responses that are included in this article, use given names only of those who explicitly consented to sharing. Exit interview and student evaluation survey responses have been pseudonymised as they were anonymously given. All student responses are coded with the year and term iteration that they participated (for example ‘Mavis 2020b’ participated in the summer school version of the course in 2020—see ).

On each occasion students were asked to share their work with each other as well as the teacher on the online learning platform, and permission for the submissions included in this paper was sought and given. In addition, the teachers encouraged class discussions concerning the activities in both an online forum and in class (i.e. Zoom room). Data is also taken from student evaluation survey responses (n∼54), exit interviews/slips with summer school students (n∼12) and email correspondence between the teachers and various students throughout the five course iterations.

The data were collated over a 2.5 year period and discussed repeatedly by the two teachers, to primarily reflect on our teaching and develop later pedagogical activities. Subsequently the data were analysed using different theoretical lenses: the theory of practice architectures, and philosophical concepts from Hannah Arendt and John Dewey. Themes arising from all data collected from student responses, and teacher reflections are included in this paper and thematically organised in order to demonstrate the ways in which these activities provoked students to consider the world from the perspective of other species, such as birds. The three emergent themes are:

Reflections on the sensory experience itself and how more questions arise from such experiences.

The possibilities and challenges of doing similar types of these activities in different settings particularly in school

Broader questions concerning how to engage with other species, especially birds as a human

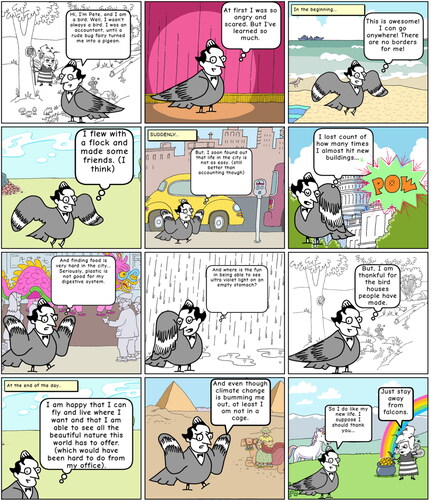

Sustainability pedagogies

To begin students were asked to ‘imagine life as bird’ and write a mini speculative biography, create a short film or page of graphic novel or to make an artwork (Sanders, Citation2022, Colucci-Gray & Burnard, Citation2020). Following that the students were asked to document a meditative sensory outdoor experience and finally tasked with creating ‘sound maps’ of their environment. The sensory meditation and the sound mapping activities were conducted following seminars that were similar in nature on all occasions (in-class and online). In these multimodal activities we see opportunities to facilitate pedagogical conversations concerning both knowledge and values in education for sustainability in the Anthropocene. While each of these activities were undertaken students were asked to consider the following reflective questions: How might this activity might work educationally in a particular/any setting? Are there challenges to working in this way? What were your thoughts, and feelings, while you did this activity?

Speculative biographies: Being birds

The first time this activity was offered (2019) we drew on an extensive taxidermic collection - a large variety of birds—owned by the faculty of Education and used by science teacher educators to assist student teachers’ recognition of Swedish bird species ().

Figure 1. Taxidermied albatross and white throated dipper (from the Dept. of pedagogical, curricular and professional studies collection).

In this seminar you will be asked to sit with a dead bird from the natural sciences teaching collection. In the presence of this bird’s ‘afterlife’ (Alberti, Citation2005) you will be asked to speculate on what life was like for this bird and consider how such teaching and learning experiences might contribute to student’s reflections on ‘being birds’ in The Anthropocene. We suggest that such activities can provoke reflections in the context of education for sustainability and, in so doing, might reframe natural sciences collections into a domain of ideas rather than solely a space colonised by dead objects [extract from 2019 course guide].

As mentioned above the later teaching moments that we reflect upon were during 2020 and 2021—where the Covid 19 pandemic, as was the case the world over, caused classes to be moved online and teaching to be adjusted accordingly. The most commanding (because of its sheer size) bird in the faculty collection was an Albatross, so, in the new online configuration, students were asked to watch the documentary film: ‘Albatross’ (https://www.albatrossthefilm.com/), in which a remote island, Midway, and its albatross population are shown to be entangled with human life by way of plastic waste circulating in the Pacific.

After watching and discussing the lives and afterlives of various birds, we would like you to make a creative work-this can be a drawing, a piece of speculative biography writing (where you imagine Life as Bird and write a mini biography), a short film or page of graphic novel. While you make this piece of creative work think about how this activity might function in an educational setting. Are there challenges to working in this way? [extract from 2020 to 2021 course guide].

Sensory meditation

The sensory meditation activity followed a seminar titled: Indigenous knowledges and outdoor teaching. The seminar begins with an offering of different definitions of Indigenous peoples -for example definitions given by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in ILO Convention 169 (ILO., Citation2003) and Burger (Burger, Citation1990) in the Gaia Atlas of First Peoples. Students then discuss the concept of Indigenous knowledges using Melissa Sweet’s quote as a starting point ‘Indigenous knowledge is inscribed over all things, the land, the waters, the sky, the sun, if only we have the insight to see, the wisdom to listen and the compassion to embrace these ancient patterns of life’ (Sweet, Citation2014). The second part of the seminar covered a brief history of outdoor teaching, focusing on utomhuspedagogik (outdoor pedagogy) as it has been practiced in education in Sweden over the past century. Links are made between the two parts of the seminar that highlight the importance of pedagogies that occur in and with the (outdoor) environment.

After the seminar we would like you to search for a place outdoors in nature (in a forest, park, by a lake, the sea, on a farm, in a botanical garden …) where you can sit for half an hour quite undisturbed. We want you to experience this place with all your senses, or at least as many senses as possible (taste may be difficult). Preferably sit on the ground. Experience what it feels to sit there. Is it hard, soft, lumpy, moist …? Close your eyes and listen for sounds. What do you hear? How many different sounds do you hear that are not human-made? Take a deep breath and let the air pass through your nose. What scents do you smell? Open your eyes and look around! Memorize what you see, focus on details. Take a thorough look at the ground you are sitting on. What do you find there (moss, lichen, grass, herbs, sticks, needles, animals …)? Look at what you find carefully and feel it. As you are leaving take pictures if you like [extract from course guide 2019–2021].

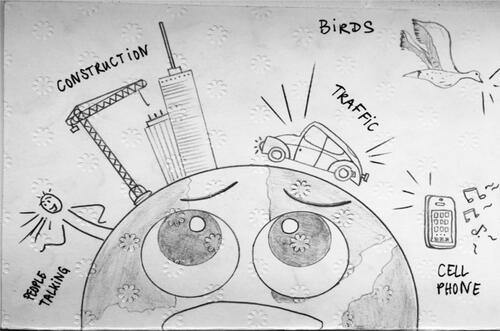

Sound mapping

For the sound mapping activity students were asked to prepare by reading a newspaper article and complete the task before the seminar. The reading is from a New York Times article written by Kim Tingley (Citation2012) in which the author focuses on the issue of human generated noise and its impact on soundscapes in diverse ecological settings, introducing us to the notion of ‘acoustic health’. The article stresses the importance of understanding: ‘what compositions nature would play without us’ and asks the question ‘is silence going extinct?’.

Please read the NYT article’ Whisper of the Wild’(Tingley, Citation2012) then reflect on its content Take a sheet of paper and a pencil (and something to rest the paper on) and find a place outside where you can sit and listen to the sounds around you. Begin to map the sounds as they seem to you in terms of distance from you and the type of sound. So if it is a distant sound map it close to the edges of the paper. If it is close to you map it nearer to the middle of the paper. Make a small description of the type of sound e.g. loud car, soft rustling sound, chirpy bird call, human footsteps, shouts, laughter [extract from course guide 2019–2021].

In the seminar that followed this creation of sound maps student were asked to, together, reflect on the relationship of the human generated sounds and the more-than-human ones. They were asked to imagine if the human sounds that they heard were not so audible and think about how humans have made an acoustic impact on planet Earth. As a final reflection they were asked to consider how they might use the article and the sound map activity in different educational contexts ().

Discussion

In the discussion that follows we reflect on the activities and, using selected submissions from students after completing the activities, ponder the themes in relation to the students’ learning that emerged. The themes most strongly shown in all the data collected relate to the sensory activities as experiences that allow the students to spectate the world in new ways. Like Eva Nyberg who was referring specifically to aesthetic experienced with plants, we found that ‘sensory experiences are key to interest, motivation, understanding and engagement’ (Nyberg, Citation2017, p. 137) with the natural world. And while we did not directly use The Burns Model of Sustainable Pedagogy (Burns et al., Citation2019) in designing these pedagogical activities we realise, as suggested in the model, that ‘ecological systems are our best teachers in designing sustainable and regenerative education systems’ (p. 4).

We are also aware that we teach, and most of our students live, in urban cities so we want to avoid fostering the feelings amongst our students that only sensory experience of and in ‘real’ nature is ‘the only true source for environmental commitment’ (Garrison et al., Citation2015, p. 188). Moreover, recent research in ecology has noted the increasingly complex relationship between city residents and urban conservation spaces (Turo & Gardiner, Citation2020). As this course is not a compulsory unit in any larger program, and that it was twice offered during a sustainability focused summer program, we understood that all students came to be in our classroom with a certain degree of interest in sustainability. However, we also understood that understandings of and experiences in sustainability education would vary due to the diverse range of student backgrounds. We focused not on the student diversity, as such, but rather how we could provide the types of arrangements for learning that used the senses.

Students told us after each of the activities, how they felt their ‘ears were opened’. Evan (2021 b) explained that these activities had made him more accepting of all noises surrounding him- ‘you can close your eyes, but not your ears’ he pointed out. Another student responded that they often do just that though, by putting on headphones whenever they were outdoors alone. This stimulated an interesting class discussion about the presence, and the absence of noise which fostered many more questions about learning in Anthropocene. Why do so many of us feel uncomfortable with ‘silence’? Can we ever really experience silence? How often do we actually want silence? Do you really need silence? (anonymous questions in exit notes 2021 b)

During Being Birds in 2019, when we physically met students and students sat with birds, we veered from the traditional use of taxidermied species in tasks of recognition. We used the specimens to ask students to consider birds’ lives and ‘afterlives’ (Alberti, Citation2005) and to speculate on ethical questions about how these birds may have lived and how they might have died. This activity draws on previous work, concerned with the affordances of taxidermied specimens (Meehitiya et al., Citation2019). We sought to prioritise the ‘bird/human values interface’ (Sanders, Citation2022) over traditional biological knowledge usually associated with taxidermied objects such as identifying and naming the species, locating habitat and mapping migration, and understanding the bird’s position in the food chain. When the collection was brought into the classroom the students asked many questions excitedly such as: ‘Are they real?’, ‘How did it die?’ and ‘Is it right to kill them just to have them as specimens’? (Sanders, Citation2022). We found that some students were very uncomfortable when presented with the specimens, and were unable to approach them for a closer look.

When classes moved online, we needed to find another way that our students could ‘sit with birds’ and so the documentary ‘Albatross’ was shown. The documentary maker, Chris Jordan (2018) asks, in the film: ‘Do we have the courage to face the realities of our time and allow ourselves to feel deeply enough that it transforms us and our future?’ It is anticipated that through viewing the film and stills from the film, students witness both the habitat of these birds and their feeding actions, alongside human impacts.

The differences between in-class and online arrangements for this activity produced different assignment submissions. Because students in 2019 were given the opportunity to present their speculative bird biographies to the class, and also to work together with their peers, many created small plays, performed poems, and hand sketched birds and wrote diary entries. Online students were also given the opportunity to work together with peers, but this was never taken, and all submissions were individual. Students in the online classes were also given more time to complete the assignment so there were more paintings, drawings, poems, and even combinations of things. Kathleen 2020a submitted one such assignment where she built a diorama (), made an audio recording of ‘the sounds of the birds outside, in mornings, during lunchtime and evenings (that you are hopefully listening to right now)’, wrote a poem () that she explained was inspired by hearing the birds in the birdhouse and provided an extensive reflection on the processes of learning she undertook.

In reflecting on this task Kathleen explained how she and her family could see birds flying into and out of a bird house that was hanging on a birch tree, through the dining room window of their home. She described that ‘the birds seem to be in a hurry, always looking around, maybe they are afraid of the bigger birds that are in an oak tree just 20 metres away… How can I imagine how the birds might feel?’ She decided to go outside to watch, ‘listen and feel [when she went out].the morning sun is bright and warming my skin, the wind is cold, there are different sounds of birds, I should record them, I think’ (Kathleen, 2020a). Kathleen reflected that she felt more invested in the lives of the birds by opening her senses, taking time to spectate and appreciate what they do each day.

Hayley (2020 b) explained how ‘thinking beyond [her] human senses and ‘become bird’ through imagining’ was a meditative experience

I chose to firstly sketch my favourite animal, a flamingo which is a wading bird famous for its brightly coloured feathers and s-shaped neck. It was obvious to me, to choose to think beyond my human senses and ‘become bird’…I used colours such as pinks, reds, blues, and purples to try to depict the essence of their beauty and place within nature in the modern world. I especially found that by choosing different colours helped me to really imagine what life would be like, as such a uniquely rare and beautiful animal in a way beyond my own humanness. This process reminded me of the beauty of nature and the natural world and why it is so vital to protect it. Lastly, I found that the exercise was rather mindful at times and had certain meditative qualities.

The sensory meditation and sound mapping activities were similar in form and outcomes in each iteration of the course. This is because, in each if these cases they were asked to find somewhere close to where they were based at the time they were undertaking the course. Both of these activities were, in a sense, types of meditation that asked the students to open their awareness to the more-than-human world. Affifi points out that meditation is another way of decentring the human that ‘is increasingly experienced not as an ongoing source of causal power independent of the material universe but as instead wrapped into a multitude of interacting processes’ (Affifi, Citation2020, p. 1443).

Charis 2020 b () contemplated the benefits of painting and drawing to reducing stress and anxiety. She reflected that using ‘art as a creative outlet…may enhance emotional intelligence, imagination and fine motor skills…[while highlighting] the role that birds play in evoking climate consciousness’. Charis highlights the link between human introspection and meditative experiences and the ‘multitude of interactive processes’ (Affifi, Citation2020) in the wider world, in this case the climate crisis.

In all of the activities the students reported being more attuned to the presence, and in some cases, the absence of sound. Jenny, 2020 b described the texture and colour of lichen and reported newly noticed sounds after her experience of sensory meditation on an island in Sweden’s largest lake:

The rock where I sit, is covered in different sorts of lichen, I know that in this part could be found more than 100 different sorts, but right now I just feel their smoothness and fragility, the different shades of colour, from yellow to green, gray and black. Some ants are running over my legs, looking for food and building material. Behind me, I hear the wagtail chirping, she/he, is always curious about what I do. At the water line, the common strand piper sings her/his ‘twi-di-di-di’ song, its Swedish name Drill-snäppa catching the iterative melody much better than the English name. A motorboat drives by….[in] the stronger wind, the leaves of the poplars begin to sing. Suddenly a ruckus of upset sea gulls and terns interrupts the…calm, almost not there sounds around me. From the volume of the ruckus I think the eagle must have flown over the skerry where the sea gulls and terns rear their children. I also have seen the wagtail flying attacks against the eagle. Bold if you think the difference in size! …As I stand up to leave, a flock of Eurasian whimbrels flies over me, singing their fast, bubbling ‘dyyee-dyyee-dydydydydydye’ It sounds a little bit sad. And it is because they are already flying to their winter quarters in West Africa. With their flyover, they mark that summer is turning towards fall—not yet fully perceptible, but unceasingly.

However, by the time the courses were offered in 2021, there had been a full year of the pandemic and there had been much reporting in both scholarly literature and the news media around the pandemic effects on sound in cities, in the oceans and upon non-human animals (see for example Dandy, Citation2020; Poon, Citation2020; Quan, Citation2020; Stollery, Citation2021; Watts, Citation2021). It was generally accepted that human made noise levels had decreased in all environments mainly because traffic and industry had been slowed under pandemic conditions. Many students related to being able to hear nature differently—and in particular birds because of the drop in traffic in their cities. Yet one student described her dislike of the ‘covid-silence’ of the city in which she lived. She explained that it made her ‘very uncomfortable’ and the ‘silence was not a peaceful experience’.

Before, during and after each activity the students were asked to think about the opportunities and challenges that might arise doing similar sensory activities in different settings. In each iteration students reflected upon how rare these kinds of activities were in their own experiences of education. Hayley reflected on the challenges of such activities on an individual level. She explained that the challenges in such creative activities ‘that I came across and also think would be evident in a conventional educational setting. This being the two main emotions, frustration and self-doubt which can be easily triggered throughout the exercise’ (Hayley 2020 b). She reflected upon her own feelings of frustration at the quality of the ‘artwork’ () she was producing ‘

which led to negative thoughts and self-doubt. I quickly reminded myself of the aim and purpose of this exercise and let this go in order to complete the exercise effectively. This resulted in a mindful experience which I continued throughout the task. However, a school environment is also a competitive one and I would worry that class members of a young age would get wrapped up in the perfection element of the process. I think that it would be important to steer individuals away from this negative thinking cycle and wanting to have the perfect drawing, by reinforcing the imaginative, inventiveness and expressive outcomes of the exercise in order to solve this challenge

Simona (2020a) from North Macedonia, who created a comic strip titled ‘The life of Pete the bird’ () using the web-based tool Make Beliefs Comix (https://makebeliefscomix.com/) felt that the challenges would be at a systems level. She reflected that teachers in her country would have difficulty ‘finding the proper recourses (computers for a graphic novel for instance) and motivation for the students (inspiring them to believe in themselves, to use art and new methods of expression)’.

She further explained that she came from a ‘country with quite the traditional and old-fashioned educational system, taking incentives to boost creative thinking is not so common’ (Simona 2020a).

Each of the activities described in this article was concerned with broader questions about how we as humans, engage with other species (especially as it turns out birds) while attempting to decentre the human in the interaction and experience. Jonas (2021 b) reflected on how he was able to ‘notice different birds and other animals and develop mindful presence-trying to embody something else’. Other students reflected on these activities as part of the course Teaching Sustainability from a global perspective, in terms of mindfulness or cognitive level as well. An email from Jenny (2020 b) explained ‘I often think about your course and the activities you gave us to learn and understand new ways to see ourselves and our relationship to nature. I think this course has changed me more than many other courses…’. Simona (2020a) explained that the Being bird ‘activity was interesting and mind boggling at the same time. I did find it unusual, yet thought provoking. It required creative and outside of the box thinking, which is great in my opinion’. Finally, Liam (2021 b) reflected upon the ‘mind-consuming’ nature of these kind of activities. He recounted how he became obsessed with thinking about scale when he was ‘being a bird; when my positions changed to migrate…I was going higher, seeing the world around me from a different scale-roof, street, city, country, continent’

Conclusion

The three pedagogical activities that we focus on in this article were originally designed to be undertaken during an on-campus university course, yet each one has been successfully translated into the course iteration undertaken online. The rapid transition to online learning triggered by the Covid-19 pandemic asked us to flatten our work into the digital space, where we could not curate the experiences of our students as actively as we had become accustomed. It was necessary to therefore use the digital space to open doorways into other particular spaces and to meet the students’ experiences in their own (familiar and natural) places. We then attempted to make our digital classroom an open space that required a depth of thought, was intensely ‘present’ and encouraged diversity.

We felt it important that we continue to provide arrangements for learning through the ‘astounding sense organs’ (Arendt, Citation1978) that encouraged ‘committed human responsibility to spectatorship of earthly creatures’ (Ephraim, Citation2017, p. 40) even at a time when students were being asked to engage in university course work in digital spaces almost exclusively. Thus, while the tasks are/were framed in a certain way, the experiences of the students and their responses to the activities have been rather open and varied. Our purpose, both in-person and online, was to intentionally cultivate experiences where students felt ‘a change of heart and a new set of eyes, a new way of viewing the world in which we are embedded and on which we depend’ (Benyus, Citation2005, paragraph 44). By participating in these activities students were empowered to engage in a form of ‘feeling-thinking praxis’ (Santos & Soler, Citation2021). Ultimately, the pedagogical practices as praxis described in this paper succeeded in helping the student participants have their ears of their ears awakened, the eyes of their eyes opened as E.E. Cummings suggests.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the many students who have engaged with this course over the past four years. In particular we would like to acknowledge the following students for sharing their creative works with us, and with permission here for this article: Jenny, Kathleen, Hayley, Charis, Simona and Natalie. Other student responses have been pseudonymised in this paper. We would also like to thank our colleague Marie Ståhl for seeding the pedagogies that focused on Swedish traditions of utomhuspedogogik.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Sally Windsor

Sally Windsor teaches in the international Masters of Education for Sustainable Development and teacher education programmes at Gothenburg University. Her research interests include Indigenous knowledges and cultures for sustainability, school level sustainability education, geography teaching, arts-based pedagogies, professional conversations and practicum pedagogies. Windsor is PI a Swedish Research Council (VR) funded project titled ‘Growing through mentoring: An activity-based inquiry into mentor teachers’ knowledge and practices’ and part of a collaborative European project ‘Climateracy—developing European teachers’ climate literacy’.

Dawn Sanders

Dawn Sanders is an associate professor who has worked at Gothenburg University, Sweden since arriving as a visiting researcher, in 2011. Her research work focuses on interdisciplinary approaches to Life on Earth and she has studied both fine art and ecology. Her doctoral research (Geography Department, Sussex University, 2004) examined botanic gardens as environments for learning. She has recently led a Swedish Research Council funded project ‘Beyond Plant Blindness: Seeing the importance of plants for a Sustainable World’ which was a collaboration between artists, botanists, and education scholars.

References

- Affifi, R. (2020). Anthropocentrism’s fluid binary. Environmental Education Research, 26(9–10), 1435–1452. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1707484

- Alberti, S. J. M. M. (2005). Objects and the museum. Isis, 96(4), 559–571. https://doi.org/10.1086/498593

- Andersson, K. (2017). Starting the pluralistic tradition of teaching? Effects of education for sustainable development (ESD) on pre-service teachers’ views on teaching about sustainable development. Environmental Education Research, 23(3), 436–449. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1174982

- Arendt, H. (1971). Thinking and moral considerations: A lecture. Social Research, 38(3), 417–446.

- Arendt, H. (1978). The life of the mind: The groundbreaking investigation on how we think. Harcourt.

- Arendt, H. (1998). The human condition (2nd ed.).

- Benyus, J. (2005). Genius of nature. Resurgence, 230. http://www.resurgence.org/magazine/article622-genius-of-nature.html

- Burger, J. (1990). The Gaia atlas of first peoples: A future for the indigenous world. Penguin Books.

- Burns, H., Kelley, S., & Spalding, H. (2019). Teaching sustainability: Recommendations for best pedagogical practices. Journal of Sustainability Education, 19

- Colucci-Gray, L., & Burnard, P. (2020). Why Science and Art Creativities Matter: (Re-)Configuring STEAM for Future-making Education.Brill | Sense. https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004421585

- Crutzen, P., & Stoermer, E. (2000). The Anthropocene. IGBP Newsletter, 41, 17–18.

- Cummings, E. E. (2008). i thank You God for most this amazing day. In G. Firmage (Ed.), Complete Poems 1904-1962. Liveright.

- Dandy, N. (2020). Behaviour, lockdown and the natural world. Environmental Values, 29(3), 253–259. https://doi.org/10.3197/096327120X15868540131215

- Davies, B., & Bansel, P. (2007). Neoliberalism and education. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 20(3), 247–259.

- Dewey, J. (1938/1997). Experience and education (new ed.). Simon & Schuster.

- Ephraim, L. (2017). Who speaks for nature? University of Pennsylvania Press.

- Ephraim, L. (2021). Save the appearances! Toward an arendtian environmental politics. American Political Science Review, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055421001180

- Garrison, J., Östman, L., & Håkansson, M. (2015). The creative use of companion values in environmental education and education for sustainable development: Exploring the educative moment. Environmental Education Research, 21(2), 183–204. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2014.936157

- Greenwood, D. A. (2014). Culture, environment, and education in the Anthropocene. In M. P. Mueller, D. J. Tippins, & A. J. Stewart (Eds.), Assessing schools for generation R (responsibility): A guide for legislation and school policy in science education (pp. 279–292) Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-2748-9_20

- GU. (2022). Summer School for Sustainability- Course description PDG459 Teaching Sustainable Development from a Global Perspective. Gothenburg University International Centre. https://www.gu.se/en/study-in-gothenburg/exchange-student/summer-school-for-sustainability-on-campus-2022

- Haraway, D. (2015). Anthropocene, capitalocene, plantationocene, chthulucene: Making kin. Environmental Humanities, 6(1), 159–165. https://doi.org/10.1215/22011919-3615934

- Huckle, J., & Wals, A. E. J. (2015). The UN decade of education for sustainable development: Business as usual in the end. Environmental Education Research, 21(3), 491–505. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2015.1011084

- ILO. (2003). ILO convention on indigenous and tribal peoples, 1989 (No. 169): A manual. International Labour Organization.

- Kaukko, M., Kemmis, S., Heikkinen, H. L. T., Kiilakoski, T., & Haswell, N. (2021). Learning to survive amidst nested crises: Can the coronavirus pandemic help US change educational practices to prepare for the impending eco-crisis? Environmental Education Research, 27(11), 1559–1573. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2021.1962809

- Kemmis, S. (2009). Action research as a practice‐based practice. Educational Action Research, 17(3), 463–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790903093284

- Kemmis, S., & Grootenboer, P. (2008). Situating praxis in practice: Practice architectures and the cultural, social and material conditions for practice. In Enabling praxis (pp. 37–62). Brill Sense.

- Kemmis, S., & Smith, T. J. (2008). Enabling praxis: Challenges for education. BRILL.

- Kemmis, S., Wilkinson, J., Edwards-Groves, C., Hardy, I., Grootenboer, P., & Bristol, L. (2014). Changing practices, changing education. Springer Science & Business Media.

- Kopnina, H., & Cherniak, B. (2015). Cultivating a value for non-human interests through the convergence of animal welfare, animal rights, and deep ecology in environmental education. Education Sciences, 5(4), 363–379. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci5040363

- Kopnina, H., & Cherniak, B. (2016). Neoliberalism and justice in education for sustainable development: A call for inclusive pluralism. Environmental Education Research, 22(6), 827–841. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1149550

- Lloro-Bidart, T. (2015). A political ecology of education in/for the Anthropocene. Environment and Society, 6(1), 128–148. https://doi.org/10.3167/ares.2015.060108

- Mahon, K., Heikkinen, H. L., & Huttunen, R. (2019). Critical educational praxis in university ecosystems: Enablers and constraints. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 27(3), 463–480. https://doi.org/10.1080/14681366.2018.1522663

- McKenzie, M. (2008). The places of pedagogy: Or, what we can do with culture through intersubjective experiences. Environmental Education Research, 14(3), 361–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504620802194208

- Meehitiya, L., Sanders, D., & Hohenstein, J. (2019). Life, living and lifelessness in. In A. Scheersoi & S.D. Tunnicliffe (Eds.), Natural history dioramas—Traditional exhibits for current educational themes. Vol. II: Socio-cultural aspects. Springer.

- Nyberg, E. (2017). Aesthetic experiences related to living plants: A starting point in framing humans’ relationship with nature? In Ethical literacies and education for sustainable development (pp. 137–157). Springer.

- Omrcen, E., Lundgren, U., & Dalbro, M. (2018). Universities as role models for sustainability: A case study on implementation of University of Gothenburg climate strategy, results and experiences from 2011 to 2015. International Journal of Innovation and Sustainable Development, 12(1/2), 156–182. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJISD.2018.089254

- Orr, D. (1994). Earth in mind: On education, environment, and the human prospect. Island Press.

- Pedersen, H. (2021). Education, anthropocentrism, and interspecies sustainability: Confronting institutional anxieties in omnicidal times. Ethics and Education, 16(2), 164–177. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449642.2021.1896639

- Pedersen, H., Windsor, S., Knutsson, B., Sanders, D., Wals, A., & Franck, O. (2022). Education for sustainable development in the ‘Capitalocene. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(3), 224–227. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.1987880

- Poon, L. (2020). How the pandemic changed the urban soundscape. Bloomberg CityLab. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-10-22/the-changing-sounds-of-cities-during-covid-mapped

- Quan, D. (2020). Listen up: In these disquieting COVID-19 times, hushed cities are making a loud impression on our ears. Toronta Star. https://www.thestar.com/news/canada/2020/04/18/in-these-disquieting-covid-19-time-hushed-cities-are-making-a-loud-impression-on-our-ears.html

- Sanders, D. (2022). Reflecting on boundary crossings between knowledge and values: A place for multimodal objects in biology didactics? NorDiNa.

- Santos, D., & Soler, S. (2021). Pedagogical practice as ‘feeling-thinking’ praxis in higher education: A case study in Colombia. Teaching in Higher Education, 1–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1885021

- Stollery, P. (2021). This is what lockdown sounds like. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/this-is-what-lockdown-sounds-like-153590

- Sweet, M. (2014). Indigenous knowledges The Australian Indigenous Doctors Association (AIDA) Conference, Melbourne, Australia.

- Tingley, K. (2012). Whisper of the wild. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/03/18/magazine/is-silence-going-extinct.html

- Turo, K. J., & Gardiner, M. M. (2020). The balancing act of urban conservation. Nature Communications, 11(1) https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-17539-0

- Watts, J. (2021). Sat 17 Apr). Pandemic made 2020 ‘the year of the quiet ocean’, say scientists. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/apr/17/covid-pandemic-made-2020-the-year-of-the-quiet-ocean-say-scientists