The model of world order has changed dramatically in the postwar era from the bipolarity between the US and Soviet Russia that characterized the Cold War, to a period of unipolarity after the fall of Soviet Russia in 1989 when the US became the world’s sole superpower, to complex multipolarity following the Global Financial Crisis in 2008. This is how Josef Borell (2021), Vice President of the European Commission, describes the transition:

Over the last three decades, we have seen a rapid transformation in the distribution of power around the world. We went from a bipolar configuration between 1945 and 1989 to a unipolar configuration between 1989 and 2008, before entering in what we today could call ‘complex multipolarity’.

There are some missing pieces in Borrell’s analysis that seem to ignore the dynamism of emerging blocs that cohere and help to amplify the existing poles as well as the development of strategic partnerships both military and political. The first point is more a perspective about the historical process of the construction of ‘poles’ and the way that they are no longer determined by western dominant influences. Here I mention two obvious examples: the Asian inflection of world capitalism and the consequences of the final overcoming of the legacy of the colonial world system, especially evident in the growing solidarity and expansion of BRICs and the G77. No one doubts that there has been a shift in the centre of economic gravity from the rich trans-Atlantic democracies to Asia that helps to define the rise of China within a dense network of bilateral trading relationships, with ASEAN as its largest trading partner. The capitalist world system has the power to create new poles and power blocs. Nor do most commentators discount the history of the decline of the world colonial system that profited Europe and the US but now defines the dynamic nature of the process of economic development of ex-colonies, particularly demographically large Asian countries like China, India and Indonesia that support very large and growing mass domestic markets.

One might argue that there are not two systems but only one system of world capitalism in its different historical phases or moments: a colonial and postcolonial phase. The latter also adds a moral perspective to the argument that has a historical effectivity in terms of UN bloc voting as well as the solidarity of the Global South. As Morgan Stanley research group expresses it in ‘Five Reasons for the Trend towards Multipolarity’: ‘In a multipolar economic world, you have groups of nations with enough influence and incentive to pursue economic strategies that, if achieved, do not substantially follow the same direction of other global power centres’. Among the continued geopolitical tensions between the US and China the rest of the world is forced to strike a balancing act and while multilateralism is in retreat new development models are being offered: ‘Improved Sino-Russian relations, the emergence of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the Asia Infrastructure Investment Bank, and the New Development Bank (previously the BRICS Bank) are clear signs of a shift to a multipolar world, providing alternatives to the Bretton Woods institutions and setting up a competition for influence between the US and China’.Footnote1 This account pays attention to both political alliances and also the underlying institutional infrastructure. Wallerstein’s world systems theory as an approach to explain the development and dynamics of the capitalist world economy analysing it in term of international trade and changing relationships between the periphery and the core economies is a better conceptualisation because it incorporates Braudel’s notion of world history (the longue durée, the medium time of economies, societies, and cultures, and histoire événementielle) such that it can theoretically entertain a reversal or modification of the core/periphery relation through BRICs solidarity as the latest incipient phase. In the not too distant future it is possible that we will see China and India as poles in the international system with European countries increasingly consigned to the periphery.

The EU as a regional bloc, not a country, is also an important world player although it is tethered to the US in terms of NATO and committed to NATO expansion with prospective new memberships of Sweden and Finland, and the Ukraine pending. Under the circumstances, even with the promotion of integration in Europe, it is not clear that the EU can fulfill its ambition to become a global power, able to function as one of the poles in the new multipolar global order when its security strategy is determined and largely financed by Washington.

The United Kingdom has now permanently separated and left the EU in a weakened state significantly damaging its own economy in the process. The disastrous failure of the neoliberal Truss government which took office for a mere 45 days, offering unfunded tax cuts for the rich during a cost-of-living crisis, plunged the UK’s financial markets into disarray and reputedly losing some 50 billion pounds. The Conservatives have settled down with Sunak but still face declining polls that will intensify after Jeremy Hart’s substantial cuts to welfare services. Its plans to become a ‘science superpower’ again through its universities have fallen behind, deprived of EU public good science funding. The post-Elizabethan UK faces further relative decline with India pipping it as the fifth world’s leading economy.

Germany and France increasingly act independently to protect their national interests. Federal Chancellor Olaf Scholtz on his one-day trip to China, the first European leader to visit since the Covid pandemic, risking criticism from the US and his own party, stated the new pragmatism: ‘New centers of power are emerging in a multipolar world, and we aim to establish and expand partnerships with all of them’. Some smaller European powers including Hungary and Serbia have begun to operate outside the EU immigration mandates, displaying strong sympathies with Russia, and have become part of the broad far-right reassertion of power across Europe represented in Italy recently electing a party under Giorgia Meloni with strong roots in Italian Fascism. This political shift will make it more difficult to pursue coordinated and joint action by member states and raise questions whether the EU can cultivate a shared vision of foreign policy in confronting the major challenges of the 21st century including the consequences of climate change, the energy and food crisis, and rising geopolitical tensions. The Russian war against the Ukraine unexpectedly provided a source of inspiration for European integration, a clarification of western values, and promoted the greatest sense of unity with the US than any time in recent years.

The Russian Federation militarily a world ‘land’ power has become more problematic as an economic pole as the effects of sanctions and the war against Ukraine has begun to bite and deplete its economy and military resources. Much will be determined by responses to Europe’s energy crisis, the US continued funding of Ukraine and the willingness of both sides to accept efforts at peacebuilding. The objections to NATO’s eastward expansion against explicit statements of intention meant that the US has achieved its strategic goals more easily than it dreamed possible only a couple of years ago. At the same time the Ukraine war and Russia’s annexation of the Crimea and eastern states of the Donbas have diminished Russia’s chances of occupying a powerful pole in a multipolar 21st century as a single power operating by itself. Even with its newly strengthened relationship with China –Xi says ‘China-Russia cooperation has no limits’—its economic union in the form of the Eurasian Economic Union (EEU) and a revitalised and enlarged Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), Russia is in a much weaker state as a consequence of Putin’s actions, at least at this point in early November 2022. It is likely that the Ukraine war will end with a negotiated peace before the European winter.

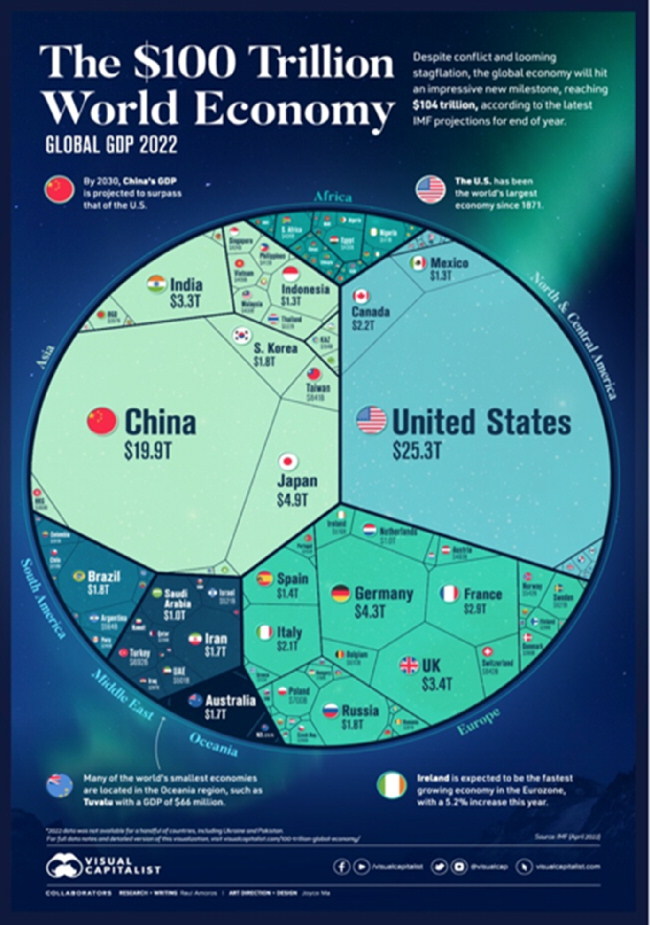

The tripartite multipolarity of Borrell’s analysis is well illustrated in the following graphic of the $100 trillion world economy, that makes clearly evident the size of Russia’s and UK’s economies relative to that of the EU. In terms of geopolitics the graphic includes within China’s Asian geography both Japan and South Korea, allies of the US, and also India which is non-aligned, while the US includes Canada and Mexico both autonomous states allied with the US. What appears as the third ‘European’ space includes Russia, Switzerland, the Nordic states of Sweden and Norway, and the UK which is no longer part of the EU. When these states are taken away the EU space its relative small size is obvious compared to either the US or China which are clearly the dominant poles, with EU a distant third. In terms of geopolitical dynamics Asia includes India and Indonesia both of which have strong economic growth rates, and ASEAN countries which is emerging as the Asian EU with growth prospect that may well put it in the same league before the end of the decade.

The Middle East is divided but holds the prospect of becoming a Muslim pole through the leadership of Turkey and Iran, with relationships to other Muslim states in the Asia-Pacific, demonstrating that it is not always a matter of geographical contiguity but may also embrace elements of religion, language and ideology. Australia and Brazil are significant as regional powers in South America and Oceania respectively, although unlikely ever to comprise poles in themselves, although may become influential components of larger blocs. Africa while economically becoming more significant demonstrates little unity or power to act as a sovereign power, although Nigeria is emerging as a powerful leading economy within Africa and the continent is the source of strong demographic growth. The graphic does not indicate growth rates, spheres of influence, alliances, or trading partnerships but it does suggest three poles and a lesser group of regional powers, structured through the superpower status of China and the US. What it does not show are the relationships among nation states, often multiple and based on shared histories, politics and trade. In these terms we can note a clear opposition: the US pole with the EU and NATO countries, together with neoliberal states, UK, Australia, Canada and NZ on the one hand; and the China pole based on closer Sino-Russian relations, the Belt and Road Initiative with over seventy countries, the six founding Eurasian states of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation also including India and Pakistan, and a series of memoranda of understanding and bilateral trade agreements with ASEAN, Asia and the rest of the world.

The Ukraine war has had the effect of unifying the US and the EU through the expansion of NATO, creating one pole while promoting closer Sino-Russian relations as the other pole, that between them structure the international system. The war against Ukraine seems to have accelerated a process of bipolarity within multipolarity, with only five countries opposing the UN censure of Russia with fifty-one abstentions. The Ukrainian defence and retaking of Kherson has had positive effects for the west, emboldening the US which taunted China recently over Taiwan with a provocative visit by Nancy Pelosi. It temporarily strengthens the US position and highlights Joe Biden’s point of inflection between democracies and autocracies. It also provides a two superpowers and a regional conflict of Ukraine-NATO, driven between Russia and Europe, with emerging strong regional powers in Asia. The G20 meeting in Indonesia with a face-to-face meeting between Xi Jinping and Joe Biden displaying a willingness to engage in dialogue with agreement not to start a new Cold War in Asia and ‘to chart the right course’, as Xi put it, to elevate the relationship and seek the right direction for bilateral ties.

The concept of multipolarity has a history in China and has been part of debate for several decades going back to the Cold War era. Leonid Savin (Citation2018) traces the Chinese concept of multipolarity to Huan Xiang, Deng’s advisor, in the mid 1980s who perceived that the old order was disintegrating and that the military power of US and Russia was declining. Against internal criticism quintipolar multipolarity (US, Russia, China, Japan and Germany) was seen as inevitable. In the 1990s three approaches had been developed: 1. One superpower and four strong powers (Yang Dazhou); 2. One super, many strong powers to be completed (Yan Xuetong); 3. ‘multipolarity is formed’ (Song Baoxian and Yu Xiaoqiu).Footnote2 Five principles of peaceful coexistence which formed the basis of the 1954 treaty with India have become the basis for China’s multipolar strategy: 1. Mutual respect for territorial integrity and sovereignty; 2. Non-aggression; 3. Non-interference in internal affairs; 4. Equality and mutual benefit; 5. Peaceful coexistence. The criticism held in the later 1990s by Yang Dazhou that China did not possess sufficient qualification at that point to be a pole and that the US will maintain its superpower status for at least three decades, seems misconceived in retrospect. It was a view that underestimated the spectacular growth of China during the first decades of the 2000s and the relative decline of the US. Predictions at the end of the 1990s did not mature although there was also some experimentation with the concept of poles and units (yuan) based on the Cold War standard of two poles of the United States and Soviet Union (Savin, Citation2018). In the G20 meeting in Indonesia both leaders Xi and Biden, and their host Joko Widodo reflecting the concern of other leaders, strongly indicated that they did not want to return to the old Cold War bipolar structure and mentality that could put global governance at risk at a time when increased international cooperation was called in order to manage economic recovery and sustainability in the post-pandemic era. Local sentiment indicated support for recovery and development and a step back from increasing trade protectionism and the US’ aggressive monetary tightening.

While perhaps too focused on nation states at the exclusion of the changing nature of the capitalist digital system and the emergence of non-state global multinational actors, Borrell’s description stands in stark contrast to President Joe Biden’s analysis that the world faces a clear choice between the politics of democracy or autocracy which appears as tired American rhetoric.

In the National Security Strategy (October, 2022) Biden prefaces the document by claiming ‘our world is at an inflection point’ and ‘this decisive decade’ ‘is a strategic competition to shape the future of the international order’. As he pitches the official narrative:

The People’s Republic of China harbors the intention and, increasingly, the capacity to reshape the international order in favor of one that tilts the global playing field to its benefit, even as the United States remains committed to managing the competition between our countries responsibly.

The National Security Strategy (NSS, Citation2022) comprises five parts: I. The Competition For What Comes Next, including ‘the nature of the competition between democracies and autocracies’; II. Investing In Our Strength; III. Our Global Priorities, ‘out-competing China and constraining Russia’ while ‘cooperating on shared challenges’ around climate and energy, pandemic and biosecurity, food insecurity, arms control, non-proliferation, and terrorism; IV. Our Strategy By Region; V. Conclusion. Large sections of the NSS, are tantamount to a point/counterpoint response to China’s initiatives such as the BRI based increasingly on state-led federal support for infrastructural renewal, subsidies for strategic technologies such as the semiconductor industry, and continued systems of tariffs on Chinese goods, especially those in the high-tech area plus an increasing array of economic sanctions aimed at individuals, institutions and countries. Jeffrey D. Sachs (2016) indicated some time ago that American foreign policy was at a crossroads: ‘facing China’s rise, India’s dynamism, Africa’s soaring populations and economic stirrings, Russia’s refusal to bend to its will, its own inability to control events in the Middle East, and Latin America’s determination to be free of its de facto hegemony, US power has reached its limits’. He argued:

The only sane way forward for the US is vigorous global cooperation to realize the potential of twenty-first-century science and technology to slash poverty, disease, and environmental threats. The rise of regional powers is not a threat to the US, but an opportunity for a new era of prosperity and constructive problem solving.Footnote3

In their watershed landmark communique, China and Russia announced a strengthened political and military alliance, on February 4th 2022, before Russia invaded Ukraine, giving strong credibility the idea of a new world order, a term used half a dozen times in the document. The ‘Joint Statement of the Russian Federation and the People’s Republic of China on the International Relations Entering a New Era and the Global Sustainable Development’ begins:

Today, the world is going through momentous changes, and humanity is entering a new era of rapid development and profound transformation. It sees the development of such processes and phenomena as multipolarity, economic globalization, the advent of information society, cultural diversity, transformation of the global governance architecture and world order; there is increasing interrelation and interdependence between the States; a trend has emerged towards redistribution of power in the world; and the international community is showing a growing demand for the leadership aiming at peaceful and gradual development. At the same time, as the pandemic of the new coronavirus infection continues, the international and regional security situation is complicating and the number of global challenges and threats is growing from day to day. Some actors representing but the minority on the international scale continue to advocate unilateral approaches to addressing international issues and resort to force; they interfere in the internal affairs of other states, infringing their legitimate rights and interests, and incite contradictions, differences and confrontation, thus hampering the development and progress of mankind, against the opposition from the international community.Footnote5

One source reminds us that strictly speaking there is only one capitalist system that embraces the world and that since China admitted capitalism into the system really it is only a matter of style in the way it is constructed to meet national interests:

Currently there is no concrete ideological or intellectual competition between Russia, China and the US. All three are stuck within the paradigm of capitalism’s political-economic framework and secular-liberalism intellectual foundations. They merely define these differently and aim to frame both in a manner best suited to their geopolitical interests.Footnote6

There is a slow revolution of the global economy that has been taking place since WWII that presages development noted by a range of social and economic theorists who were the first to mention the postindustrial economy. There is a fundamental shift away from principles of classical industrial economy that held sway since the industrial revolution based on industrial production, capital/labor oppositional politics, mining of raw materials and use of fossil fuels within the confines of the nation-state. The international order was largely a reflection of such a collection of industrial nation-states that build on the international colonial trade favoring western great powers. Slowly this arrangement has given way to a new international economic order centered on the rise of global corporations focused on the new digital technologies and renewable energy sources with the rise of a new global ruling elite who became the leaders of a transnational capitalist class (TCC). This process is not complete. It is fragmentary, largely led by the US, China and the EU, and by no means assured as it faces strong anti-globalist, strengthening nationalist and anti-market forces both domestically and internationally. The older nation states-based elites who controlled the liberal world order established at the end of WWII have been increasingly replaced by a new global elite on the one hand and an older-styled liberal international world agency-based bureaucratic elite on the other. The latter, an elite based on a new social contract, seek to mediate in the conflicts among nation-states, especially between Global North and Global South, through a world architecture that reflects older-style liberal internationalist leanings supported by institutions set up at Bretton-Woods.

At the center of this revolutionary transformation of the global economy are a set of new digital technologies including the internet, 5 G, supercomputing, and soon quantum computing that have since the 1970s encouraged a greater world interconnectivity in trade and finance. The corporations that developed new digital technologies as scalable businesses that exploit global markets led to first-wave financialization of capitalism and the extensive development of the structure of world capital markets strongly encouraged by monetarism and neoliberalism that promoted deregulation and financial liberalization. It made possible foreign direct investment flows, economic interpenetration, inter-bank lending as well as the phenomenal growth of transnational investment in the new stock markets opening up in Hong Kong, Shenzhen and Shanghai. This world expansion was aided by after China joined the WTO in 2001 and Chinese banks gained greater autonomy. The Bank of China, the China Construction Bank, the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China, and the Agricultural Bank of Bank ranked among the largest in the world as among the seven top largest in assets terms. In 2020 Chinese stocks constituted about one-third of global gains as transnational investors poured over a $1 trillion into Chinese capital markets.

Financialization as a systematic high-tech transformation of capitalism based on (i) the massive expansion of the financial sector where finance companies have taken over from banks as major financial institutions and banks have moved away from old lending practices to operate directly in capital markets; (ii) large previously non-financial multinational corporations have acquired new financial capacities to operate and gain leverage in financial markets; (iii) domestic households and students have become players in financial markets (the ascendancy of shareholder capitalism) taking on debt and managing assets; and (iv) in general, represents the dominance of financial markets over a declining production of the traditional industrial economy.

The rise of neoliberalism is explained by the growing role and power of finance in the political economy of capitalism and the growth of a new global finance class but financialization is result of neoliberal restructuring but has deeper roots in a change in the nature of corporations that jettisoned its traditional loan-making functions to pursue the creation and sale of its own financial instruments. Neoliberalism, beginning 1980 in the US under Reagan, encouraged the shift to a deregulated neoliberal global capitalism symbolized by the repeal of the Glass-Steagall Act in 1999.

The US as the world’s largest economy is still also the world’s most powerful military with an annual budget of $780B (est.) and some 800 military bases worldwide. After the war in Afghanistan it now faces strict limits to its power and in the face of multiple strategic partnerships and relationships that stand against it the US no longer holds a position as sole hegemonic power. The US also faces huge domestic problems at home including the savage split between political parties, the erosion of its democratic institutions and the prospect of more political violence after the Trump-inspired insurrection and attack on the Capitol. The 2024 presidential election, possibly between Biden and Trump, will prove to be an historic moment for the stability and survival of American-style neoliberalism and will likely determine its continued world status and its rate of decline. Biden’s efforts at rebuilding liberal internationalism after Trump’s ‘America First’ withdrawal from various world bodies, commitments and protocols, including the Paris Accord and RCEP, seem frantically too little too late. The hurried convening of the Quad (US, Japan, India, South Korea) as a bulwark to China and the AUKUS, based on providing Australia with nuclear-powered submarines, seem of limited value in the White House effort to ‘out-compete’ and contest China’s spreading influence in the Asia-Pacific. The much-vaunted ‘pivot to Asia’ by the US dressed up in terms of ‘Indo-Asia’ considered as a measure of Indian sub-continental democracy alongside the Quad, is deliberately ambiguous and contests its ‘one China policy’, edging the world closer to conflict than diplomacy. It is an action that seems likely to increase geopolitical tensions in the Asian region and tests the ‘loyalty’ of US traditional allies, splitting allegiances with smaller countries balancing and playing off US against China for strategic gains, especially in ASEAN countries and the Pacific Islands.

The problem is that the world’s democracies are not performing very well. The Blacklivesmatter# movement protesting police brutal racism and the political insurrection that resulted in an attack on the Capitol justifies the US slipping well down the Freedom Democracy Index ranking. According the Economist Group’s Democracy Index 2021 less than half the world’s population live in a democracy either in a full democracy (6.4%) or a flawed democracy (39.3%) that includes the US, with 17.2% living in hybrid and 37.1% living in authoritarian regimes.Footnote8

Neoliberalism as an economic doctrine seems to have reached its limits such that free market fundamentalism has been ditched for heavy levels of Federal support costing the US taxpayers trillions of dollars since Biden became president, which together with an elaborate and comprehensive system of subsidies and economic sanctions against individuals, institutions and countries, tips the scale in the US’s favor. In this transition we should not forget the way in which the world’s financial system is propped up by the US dollar reserve system although there are efforts to bypass it through reciprocal currency trading and the norming of a basket of alternative currencies.

By contrast, committed to a form of openness and trade based economic globalization China has become the world’s largest trading nation building up a succession of bilateral trade agreements with over 120 countries over the last twenty years, enhanced further since the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) was established in 2013 as Xi’s ‘project of the century’ that links the Eurasian landmass. China’s globalization does not neglect poverty elimination at home and works to assist economic development in the Global South, with an increasingly strong focus on Africa. President Xi has been reelected as leader of the CCP at the 20th Congress for an exceptional third term and the country is assured of political stability at a time of world crisis. It’s continued high growth rate, while now surpassed by India, Indonesia and Vietnam, will assure it of being the world’s leading economic power by the end of the decade. With the relative decline of the US, and the increasing ascendency of China as the world’s second largest economy and world’s largest trading nation. China has emerged as the major pole along with the US in structuring the new multipolar world order comprised of emerging world powers including India, Egypt, Iran, Brazil, Indonesia and Nigeria, and the existing world players, Russia, the EU and Japan.

At the BRIC’s conference in June Putin talked of creating an international reserve currency. Leaders of Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa with a combined population of 2.88 billion estimated to overtake the G7 contribution to the global economy in under 15 years demanded a fairer international system.Footnote9 The New Development Bank (NDB) was proposed in the 4th BRICS Summit (2012) with the objective of financing the BRICS association for sustainable development of projects and infrastructure, specifically designed to help developing economies. The G77 established in 1964 with increased membership of 134 countries also has positioned itself as a counterbalance to the G7.Footnote10 It is the largest intergovernmental organization of developing countries in the UN with the aim ‘to articulate and promote their collective economic interests and enhance their joint negotiating capacity on all major international economic issues within the United Nations system, and promote South-South cooperation for development’. The G77 is not only the largest bloc within the UN system but also sponsors projects on South-South cooperation through the Perez-Guerrero Trust Fund (PGTF) established by the UN in 1983 and ‘a South-South network linking scientific organizations, research institutions and centres of excellence to further expand South-South cooperation in the field of science, technology, and innovation’.Footnote11

Rather than using the nation state as the only unit for making judgements concerning the international system, in addition, it is also necessary to understand the emerging system in relational terms defining a new complexity of multipolarity. There are many different levels of analysis of an emerging dynamic complexity including the interaction of demographic, economic, political factors and geo-environmental factors best conceived of as overlapping ecologies defined by their organizational memberships, economic alliances and trading relationships rather than individual nation state units that structure the main lines of multipolarity:

Western relative decline (the decolonization thesis): The ongoing relative decline of countries (nation states), mostly previous European ‘great powers’ through decolonization in the 19th and 20th centuries with the US since reaching its zenith and peaking in the early twentieth century, while others countries including ex-colonies are ‘rising’ or ‘emerging’ in relative terms (‘declining’, ‘rising’ and ‘emerging’).

The strategic regrouping of the West, US and EU through NATO security; the US ‘pivot to Asia’ and development of the Quad and AUKUS; Brexit the UK and the Commonwealth.

The rise of China within a network of trading and security relationships in the Asia-Pacific; ASEAN is China’s largest trading in 2020 for the first time and China is ASEAN is also China ‘s largest with two-way investment exceeding $340 billion at the end of July, 2020; China’s BRI and bilateral trade with Africa.

The China-Russia axis, Eurasian Economic Union, Shanghai Cooperation Organization, & the BRI. At the SCO Summit 2022 Xi emphasized time to reshape the international system and ‘abandon zero-sum games and bloc politics’ to ‘work together to promote the development of the international order in a more just and rational direction’.Footnote12

The pivotal position of India as a member of both SCO and the Quad, and as a country with the strongest growth rate of 6.8 in 2022; a middle power status and a rising power that under Modi has followed the path of liberalisation and repositioned itself as a global actor (Kukreja, Citation2020).

The construction of the global interconnected digital economy with the flow of digital goods and services and an acceleration of digitization during the Covid years creating greater level of digital interconnectivity and digital trade (‘digitalization’).

The development of global ‘transnational’ corporations often larger than all but the largest countries with a new ruling elite with more power than most smaller nation-states (‘transnationalization’).

The narrative reconstruction of the Global South and rising levels of South-South cooperation with the development of G77 countries no longer seen as ‘passive receivers’ of Global North international aid, structural adjustment policies and increasing levels of structural indebtedness (‘new Global South activism’).

G77 and BRICs as increasingly influential blocs within the UN and international system.

The growth, expansion and institutionalization of world agencies and NGOs based on traditional liberal international order, including the UN and the UN Family of Organizations,Footnote13 some 16 autonomous organizations linked to the UN (eg. FAO, IAEA, ILO, IMF, UNESCO, WHO, WTO, WB) (‘liberal international architecture’).

The regionalization of territories for reasons of trade and security including EU, NATO, SCO, RCEP, APEC, ASEAN, Quad, AUKUS etc. (‘regionalization’).

The appalling fact that ‘the 26 richest people in the world hold as much wealth as half the global population’ in a world where ‘multiple inequalities intersect and reinforce each other across the generations’ and where ‘the world’s richest 1 per cent captured 27 per cent of the total cumulative growth in income’ in the period 1980–2016 demonstrates the world structural inequalities that need urgent attention at a time when both the planet and humanity are striving for survival in the face of multiple challenges (Guterres, Citation2020).

Beijing Normal University, Beijing, P.R. China

[email protected]

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

References

- Borell, J. (2021). How to revive multilateralism in a multipolar world? https://www.eeas.europa.eu/eeas/how-revive-multilateralism-multipolar-world_en

- Guterres, A. (2020). Tackling the inequality pandemic: A new social contract for a new era. United Nations. https://www.un.org/africarenewal/web-features/%E2%80%9Ctackling-inequality-pandemic-new-social-contract-new-era%E2%80%9D

- Kukreja, V. (2020). India in the emergent multipolar world order: Dynamics and strategic challenges. India Quarterly. 76(1), 8–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0974928419901187

- National Security Strategy (NSS). (2022). USA. https://www.whitehouse.gov/wp-content/uploads/2022/10/Biden-Harris-Administrations-National-Security-Strategy-10.2022.pdf

- Sachs, J. D. (2016). Learning to love a multipolar world. https://www.project-syndicate.org/commentary/multipolar-world-faces-american-resistance-by-jeffrey-d-sachs-2016-12?utm_term=&utm_campaign=&utm_source=adwords&utm_medium=ppc&hsa_acc=1220154768&hsa_cam=12374283753&hsa_grp=117511853986&hsa_ad=499567080225&hsa_src=g&hsa_tgt=aud-1249316001557%3Adsa-19959388920&hsa_kw=&hsa_mt=&hsa_net=adwords&hsa_ver=3&gclid=Cj0KCQjw1vSZBhDuARIsAKZlijSk73gYc79kC6QA4nTveUJJi6WjIVKozyeZ5_G5x2KffjUUI-4EKigaAoZLEALw_wcB

- Savin, L. (2018). China and multipolarity. https://www.geopolitika.ru/en/article/china-and-multipolarity

- Vaswani, K. (2022). G20 in Bali: Trouble in paradise as leaders gather. BBC News.