Background

Political devolution occurred in the UK in 1998–99, following many years in which some degree of policy administration had been devolved to the four nations. Since devolution, all four countries of the UK have pursued increasingly divergent education policies. This is true in England in particular, where diversity, choice and competition have become a key focus of education policy. This political divergence between the four nations gives us the opportunity to appraise differences and similarities in educational policies and outcomes in the four UK nations.

Purpose

This article is a comparative review of the education reforms of the constituent countries of the UK, with particular focus on value for money. The main aims of the article are to (1) outline the key differences in the educational systems in terms of school type, choice and competition, educational resources and pedagogy; (2) describe how the countries compare in terms of educational attainment during compulsory schooling years; (3) examine inequalities in educational attainment, such as by gender and socio-economic status, and how the different countries compare on these measures; and (4) examine existing evidence on the effectiveness and value for money of different education policies and programmes in the different countries.

Sources of evidence

We use a variety of sources of evidence to achieve these aims. We undertake a literature review of the existing evidence on the effectiveness and value for money of different programmes and policies that have taken place across the UK. We also collate and undertake an analysis of data on educational outcomes from published statistics sourced from the national statistics offices of each country. It is easier to be confident about comparisons based on international data sets because in this case all students will have taken exactly the same test, so we also compile and analyse survey data from international surveys of educational attainment such as PISA, PIRLS and TIMSS.

Main argument

We argue that while the systems of the four countries of the UK are becoming increasingly divergent, there are still many similarities. This is borne out in the evidence on educational outcomes, which show many similarities between the four countries. Because of these similarities, the positive impacts of many of the policies and programmes adopted in England may have relevance for Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Conclusions

We find evidence that increasing school resources improves results, and also that more targeted spending benefits able pupils from disadvantaged backgrounds. We also find positive results of several programmes. Evaluating the education policies of the four nations in terms of value for money – and therefore whether they have scope to be adopted – represents a bigger challenge. Whilst the value for money of certain policies – such as the literacy hour – can be reasonably well measured, for many other policies, value for money is hard to pin down accurately. However, this forms an important direction for future research.

1. Introduction

Recently, the four ‘home nations’ of the United Kingdom are becoming increasingly different with regard to education policy. Nevertheless, they remain very similar compared with education systems elsewhere. Over time, they have had a similar legislative framework (particularly in England, Wales and Northern Ireland) and, in a broader sense, there is a similar social context across the four countries. For example, there is a comparable level of inequality across many education indicators, with similar trends emerging in recent times. In-depth analysis by the National Equality Panel (Hills et al. Citation2010) attributed this to the fact that many of the policies that are important for influencing distributional outcomes (such as tax and benefits) are UK-wide.

In this paper, we take the opportunity to appraise differences and similarities in educational policies and outcomes in the four UK nations. The fact that England has pursued very different policies in the recent past than Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland provides a good testing ground to undertake such a comparative review of education policy and in terms of what can offer value for money in education. It should be acknowledged that, in a general context, it is easier to compare education reforms in terms of their effect on educational attainment rather than to compare them in terms of value for money. The latter requires an ability to translate improvements in educational attainment to ‘final outcomes’ (in the short-term and long-term), such as labour market earnings and non-market benefits (e.g. crime, health). It also requires some knowledge of costs. For some reforms, it is relatively easy to find information on costs but for other reforms (e.g. measures to improve school competition), it can be hard even to conceptualise what the relevant costs are. In this light, this paper is probably best thought of as mainly informing one important component of a ‘value for money’ comparison – namely, the direct effects of reforms on educational attainment. However, we refer to ‘value for money’ both in a broader sense and in terms of specifics about particular polices, where it makes sense and is feasible to do so.

The content of the paper is structured as follows. In Section 2, we discuss some key areas of education policy in England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. In Sections 3 and 4, we compare the countries in terms of educational performance and inequality. In Section 5, we then discuss evaluation evidence as it relates to key educational issues and the differences and similarities in educational outcomes across the different UK nations. Where possible, we make reference to costs as well as to benefits and ‘value for money’. Section 6 offers some concluding remarks.

2 The institutional context

Political devolution formally happened in the UK in 1998–99, following many years in which some degree of policy administration had been devolved to the four nations. Since devolution, even more political power has been delegated to national assemblies, in particular areas of policy (including education). This political divergence between the four nations has stimulated debate in the education literature over the direction and extent of divergence (as discussed by Raffe and Byrne Citation2005).

However, on balance, there are still more similarities between the countries than differences. This is particularly the case for England, Wales and Northern Ireland, which have a similar National Curriculum (although differences have increased since devolution), and where all students take the General Certificate of Secondary Education (GCSE) examinations at age 16, and A-levels at age 18 (for those who want to continue academic education up to age 18). Thus, attainment across these countries is comparable.

The Scottish education system, however, is distinct from the rest of the UK in many ways – and this precedes devolution. The exams taken at age 16 and 18 are different and it is only possible to make comparisons with the rest of the UK in a rather crude way (as will become clear below). There is no official National Curriculum in Scotland. Instead, there are non-statutory curriculum guidelines and the minister in charge of education is legally required to set national priorities for education and to review these at intervals (Ellis Citation2007). Traditionally, the secondary school system has more emphasis on breadth across a range of subjects rather than depth over a smaller range of subjects.Footnote 1

We discuss further comparisons between the four countries under the following themes: school type; choice and competition; educational resources; and pedagogy. Table briefly summarises some key dimensions of comparability and difference.

2.1 School type

England, Scotland and Wales all have a comprehensive model of education. This means that pupils are not selected by ability into secondary schools. This is different from the selective system of education that was introduced in 1945, where pupils were selected either into schools for the academically more able (grammar schools) or to education with a more vocational orientation (secondary moderns). This system was gradually abolished across local authorities in the 1960s and 1970s. It was retained in Northern Ireland (and in a small number of local authorities within England) due to parental pressure in some local authorities. Over the years, there have been periodic debates, both in the academic literature and in the policy environment, about the consequences and merit of this decision.

Table 1. Features of the education system across the UK nations.

In recent decades, and particularly since the 1990s, there have been attempts to use policy to increase diversity within the comprehensive system in England. For example, schools were encouraged to apply for specialist status through the 1990s (meaning that they would have particular expertise for a particular subject area and receive funding for this purpose). In the 2000s, a new school type, ‘academies’ were introduced. The academies scheme initially aimed to target entrenched issues of pupil underachievement within state secondary schools located in deprived areas. The basic idea was to replace a failing school in an inner city area with a brand new school – with a new building, new staff, private sector sponsor, and most importantly, autonomy over key areas of decision making; academies would be managed by their sponsors and any governors they appoint, and would have responsibility for employing all staff, agreeing pay and conditions, freedom over most of the curriculum (except for core subjects) and all aspects of school organisation. Details of how the system operates are well documented by Wilson (Citation2011). A total of 203 academies were established by the end of Labour’s time in power (April 2010).

However, what mostly started as a targeted scheme has now become far more widespread. In 2010, the Conservatives and Liberal Democrats coalition government announced plans to expand the academy programme with the Academies Act 2010. This act made it possible for any state school in England to become an academy and hence opt out of local authority control. As of 1 October 2012, there were 2373 academies open in England.

Machin and Vernoit (Citation2010) present evidence that the schools that, under the coalition government, have recently expressed an interest in converting to an academy are characterised by a more advantaged student intake (e.g. a lower proportion of students eligible to receive free school meals) and higher educational attainment. The academies programme is now seen as a general school improvement strategy rather than being specifically targeted at disadvantaged areas; this is a very different model from that originally intended by the Labour Government in 2000, and it is somewhat early to evaluate the effectiveness of this new tranche of academies. Nevertheless, the ‘roll-out’ of the policy has important implications for the educational structure in England as a direct consequence of the academies programme is to reduce the power of local authorities in educational matters.

In Wales and Scotland, there has been no such policy either to create diversity within the comprehensive system or to grant schools greater autonomy. In both these countries, local authorities play a very powerful role in the management of schools. Moreover, it is important to note that this is within the context of locally managed schools and schools retain a strong element of management control over their own affairs, even though local authorities have a stronger strategic role than in England.

School type in Northern Ireland is very different (particular at secondary level) because of the selective system that, as previously mentioned, is still retained. Children take a test at age 11, which determines whether they are able to attend grammar schools (academically elite) or other secondary schools.Footnote 2 About 40% of the cohort now attends grammar school. Northern Ireland also differs from the rest of the UK in being largely segregated along religious lines. Most schools are strongly segregated by religion in that they have high proportions either of Protestants or of Catholics. There is also a much higher proportion of single sex schools (particularly among grammar schools) than in the rest of the UK.

2.2 Choice and competition

Over recent decades, parental choice and competition between schools has become particularly important within England. For example, parents may apply to any school of their choice and may only be refused if the school is over-subscribed. Of course, as we discuss in more detail later in the paper, residential proximity to schools then becomes the key criterion for admission (along with the associated distortion in housing market valuations that ensues). To facilitate parental choice (and competition between schools), ‘league tables’ of school performance are published. In the rest of the UK, schools do not face such public exposure (although information can be sought from local authorities).Footnote 3 In Scotland, children are expected to attend school within a catchment area that is dependent on where they live. If parents would like to apply elsewhere, they need to apply to a panel and will be considered only if there are vacant places in the other catchment area. It is not clear how important this difference is in practice compared with the more ‘free market’ approach in England. In the latter case, popular schools are often over-subscribed and then schools apply over-subscription criteria to reach their desired number of enrolled pupils – mainly based on distance from the home to the school.

2.3 Educational resources

Since teacher salaries account for the bulk of school expenditure, the pupil teacher ratio is a reasonable proxy for school resources. Table shows how the pupil–teacher ratio compares across countries at primary and secondary school. England and Wales are similar on this measure, although school funding generally is about 10% lower in Wales.Footnote 4 However, across nations there are important differences in the funding mechanism. In England, most funding goes directly to schools based on funding formulae. However, in Wales, much of the funding is held back by local councils for central services (about one quarter of funding in 2006/07, as discussed by Reynolds 2008).

The pupil–teacher ratio is lower in Scotland compared with the rest of the UK (by around 20–25% in primary schools). This is also reflected in other data on school expenditure, although there are doubts about its reliability (CPPR Citation2009). Finally, in Northern Ireland, the pupil–teacher ratio at primary school is similar to that in England and Wales, but the ratio for secondary schools is somewhat lower (though also higher than in Scotland).

2.4 Pedagogy

One important area of policy across all four countries concerns the development of improved methods to teach children how to read and write. There has been a common policy concern about the significant numbers of people who end up with low levels of literacy and numeracy.

In England, the policy response has been ‘top down’, with schools expected to implement national policies. In Wales and Scotland, this is considered a matter for local government. In Northern Ireland, there has been a literacy strategy introduced, although it is more ‘light touch’ than its English counterpart.

One of the big policy initiatives in England in this area was the introduction of a national literacy and numeracy strategy (in 1997/98 and 1999/2000, respectively). These initiatives aimed to improve the quality of teaching through more focused instruction and effective classroom management. Schools were expected to implement a daily ‘literacy hour’ and ‘numeracy hour’ in primary school. (This was supported by a framework for teaching, which sets out termly objectives for the 5–11 age range and provides a practical structure of time and class management.)

In Wales, all local authorities were expected to devise their own strategies for literacy and numeracy and by 1999, the literacy strategy in most Welsh LAs consisted of a ‘mixture of different initiatives’ – mostly at an ‘early stage of development’ (Estyn 2000). With regard to numeracy, Welsh inspection reports suggested an improvement over time but suggested that often teaching was not structured carefully enough (Estyn Citation2001).

Jones (Citation2002) has conducted a comparative study of numeracy initiatives in England and Wales. He explains that prior to the introduction of the National Numeracy Strategy in England in September 1999, there was nothing to suggest that numeracy practices or the standards achieved by pupils in Welsh primary schools or in the early years of secondary schools were significantly different from those in England. However, the Welsh Office decided that they would not introduce the prescriptive, top-down approach implemented in England and instead encouraged LAs, in partnership with their schools, to develop their own, locally based initiatives. Jones (Citation2002) argues that the decision not to adopt the National Numeracy Strategy in Wales was potentially one of the most significant educational policy decisions taken in Cardiff during recent years.

In Scotland, the approach to pedagogy is even more decentralised. As referred to above, there is no official National Curriculum in Scotland (unlike in the rest of the UK). Each local authority is expected to interpret and deliver curriculum guidelines and national priorities in a way that meets local needs. According to Ellis (Citation2007), this devolved decision making removes the literacy curriculum from national political debate and places it into the hands of practitioners. One of the most famous (within the UK) policy interventions with regard to literacy has been in a Scottish local authority, Clackmannanshire. This was based on teaching children how to read using synthetic phonics (a policy that is discussed further below). The reaction in England has been to roll out a method of teaching synthetic phonics to all schools.

3 Educational attainment across the home countries

Having given a brief outline of how key education policies differ within the four countries of the UK, we now describe how they compare in terms of educational attainment. As already noted, there are issues of comparability between the four nations at different stages of the education sequence that we need to acknowledge. In this section, we draw as best comparisons that we can from a range of different data sources.Footnote 5

In , we show how educational attainment varies across the four countries of the UK, using national and international data sets respectively. In each case, we start by presenting measures taken when children are fairly young (first rows) and build up to measures for older age groups. The numbers all relate to recent cohorts.

Table 2. Education performance across the UK nations: national data sets.

Table 3. Education performance across the UK nations: international data sets.

In the first two rows of Table , we can compare the age 7 maths and reading scores across countries. These tests are taken within the Millennium Cohort Survey (a sample of children born in 2000) and have been standardised here to have a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. The scores across all four countries are very similar (especially with regard to maths), and only a little lower for reading in Wales and Northern Ireland (a score of about 47, compared with about 50 in England and Scotland).

In the next two rows, tests taken at the end of Key Stage 2 are compared in terms of the percentage of students achieving the ‘expected level’ at age 11. This can only be shown for England and Wales. Comparisons are of restricted value here because of changes to the curriculum in Wales. Taken at face value, however, students perform very similarly across the two countries (if anything, a little better in Wales).

The next three rows show indicators from the GCSE examination (or equivalent). England, Wales and Northern Ireland are more comparable to each other on this measure than any of them is to Scotland. However, the overall indicator (five or more GCSEs at A∗–C – a longstanding government target for GCSE attainment) is at a similar level in England, Scotland and Northern Ireland. The most striking difference is with Wales, where the proportion of pupils achieving this target is about 10% lower than in the other countries. When we look at subjects typically studied by most pupils, the difference between Wales and the other countries is less stark. It appears that performance in maths is close in Wales and Scotland (50% and 48% of students achieving a grade A∗–C in 2006/07) and in England and Northern Ireland (about 54% in each case). With regard to performance in English, achievement in England and Wales is closest (60.2% and 58.9%, respectively) and similar to Northern Ireland (62.9%) but much better in Scotland (69.8%). However staying-on rates for 16-year-olds (2006/07 data) are considerably lower in Scotland than in the other countries of the UK. Also, the percentage of students achieving at least two A-levels or equivalent (i.e. a typical entry-level qualification for university) is relatively low in Wales and Scotland (27.1% and 33.2%, respectively – in 2010/11) compared with England or Northern Ireland, where the figure is about 50%.

It is easier to be confident about comparisons based on international data sets because in this case all students take exactly the same test. In Table , we show figures for the four UK nations for three international data sets, for recent years. The first two rows relate to an international reading test for 10-year-olds (the Progress in International Reading Literacy Study, PIRLS), in which England and Scotland both participated in 2001 and 2006. The next rows show maths test results for 10-year-olds from the Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS). Again, England and Scotland both participated in 2003 and 2007. We can also use TIMSS to make comparisons between the maths scores of 14-year-olds in these countries. Finally, test scores in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) can be compared across all four countries of the UK in both 2006 and 2009.

Comparability between the data sets (and even over time for the same data set) is problematic because a different set of countries is used for each international data set. The scores have been normalised for the countries taking part in each survey and are expressed relative to an average of 500 (with a standard deviation of 100).

With regard to PIRLS, both England and Scotland perform well relative to the average. Depending on the year and survey (2001 or 2006), they perform one-third to half a standard deviation higher than the average of other countries taking part. In 2001, England’s reading performance exceeded that of Scotland by about 20 points. However, by 2006, Scotland’s performance had increased a little (by 6 points) and England’s performance had deteriorated (by 21 points), placing them much closer together (530 and 536 points in England and Scotland, respectively). With regard to maths performance of 10-year-olds (as recorded in TIMSS), England also does relatively well internationally (similarly to PIRLS), with some improvement between 2003 and 2007. However, performance in Scotland is below the average for countries taking part in this survey (490 in 2003) and there has been little improvement over time.

We have both PISA and TIMSS with which to compare the performance of teenagers. England’s relative performance looks better in TIMSS, with some improvement over time (comparing 2003 with 2007). In PISA, England is performing just below the average of OECD countries taking part in the survey and there would appear to be hardly any change between 2006 and 2009. However, even within the TIMSS survey, the relative performance of England looks a lot better for primary-aged children (as is also the case with PIRLS).

When comparing countries of the UK for PISA and TIMSS, the similarities are more striking than the differences. On two occasions, a notable difference arose between England and Scotland: in PISA 2006, Scottish students outperformed their English counterparts in maths by 11 points but in TIMSS 2007, English students outperformed their Scottish counterparts by 26 points in maths. However, in the four other tests (TIMSS 2003 maths, PISA 2009 maths, PISA reading 2006 and 2009), the difference in performance between the two countries is six points or less. Similarly, the difference between England and Northern Ireland is very similar (in three out of four international tests). There is one consistent finding of difference in the PISA study: performance in Wales always lags behind the other UK nations. The difference between Wales and the closest other UK comparator is 11 and 9 points in maths and reading, respectively, in 2006. It is 22 and 22 points, respectively, in 2009. This relatively poor performance is consistent with the relatively poor performance on some national indicators described above – the general GCSE indicator (five or more GCSEs) and two or more A-levels.

Overall, this comparison suggests more similarities than differences in overall performance and only average performance across all countries (relative to others taking part) in international studies. The international studies for primary-aged children inspire more hope that performance (at least in England) is relatively good. However, this needs to be set against signs of deterioration over time in the PIRLS study for England and little change for Scotland. Perhaps the one most striking finding is that Wales shows relatively poor performance across many of these indicators.

However, it might be the case that the differences between countries are driven by differences in the students undertaking the surveys. In Table , we show the findings for PISA in a regression context and then adjust coefficients for differences in demographics, parental education and socio-economic status. Adjusting for only a few demographics (gender and immigration status) as well as parental education removes the difference between England (the omitted category) and other UK nations for the most part. However, there is no change in the rather large differential with Wales. When controls are included for socio-economic status and home resources (i.e. books in household), this differential only narrows to a small degree, whereas Scottish students perform consistently better (and similarly) compared with England across three out of four of the international tests. However, at most, this positive differential is 8 points – which is not a large difference in the context of some of the other differentials discussed above. The main insight of this exercise is that relatively poor performance in Wales is not primarily due to more disadvantaged students taking part in the PISA survey (at least, not as captured by these measures).

Table 4. Performance on the PISA test.

4 Educational inequality within countries

Despite similar averages (for the most part), the evidence we have presented so far could mask possible differences in variations around the average. In this section, we therefore consider two sources of inequality in educational outcomes within countries based on national and international data sets. We begin with differences by gender and then move on to differences by socio-economic status.

show differences in performance measures between boys and girls using indicators from national and international data, respectively. Using tests in the Millennium Cohort Study (Table ), there is almost no gender difference in maths scores in any of the countries at age 7. There are differences for reading, but they are small in magnitude. The gender differential (expressed as the gap between males and females) in Scotland is lower than elsewhere (−0.7 points, compared with −1.7 or −1.9 in the other countries). If we compare Scotland to England, boys perform exactly the same, whereas girls perform a little better in England.

Table 5. Gender inequalities in education: national data.

Table 6. Gender inequalities in education: international data.

The third and fourth rows of Table show performance by gender (and differentials within each country) at the end of primary school (at age 11) for England and Wales. The differential is sizeable for English (about 9% in favour of girls in both countries) and smaller for maths (1% higher for boys in England; and 3.5% lower for boys in Wales). It is interesting to compare these differences to those shown at age 10 in the international data sets (PIRLS and TIMSS) – which records this for England and Scotland (Table ). In this case, girls outperform boys in reading (by 19 points and 22 points, respectively) and perform either similarly in maths (no difference in England) or better (by 9 points in Scotland). The qualitative similarity of these gaps across data sets probably suggest that gender differences are not primarily a consequence of the specific tests taken in these countries.

When we consider performance at GCSE (Table ), the gender difference in favour of girls is evident in all countries of the UK with regard to the overall indicator. It is lowest in Scotland (5.4%) and highest in Northern Ireland (12.9%). In England and Wales, it is 7% and 9.4%, respectively. Differences are greater in English (across all countries) and considerably smaller in maths, although this still favours girls. The differences are also evident when it comes to the A-level indicator. This varies from 7.4% in Wales to 15% in Northern Ireland, again in favour of girls.

With regard to international data sets (Table ) on the performance of teenagers, similarly big gender differences are found in reading across all countries of the UK. They also show differences for Northern Ireland that are a little bigger than for the other countries. However, the gender differences for maths are radically different if we compare TIMSS and PISA. The former shows a small difference favouring boys (6 points in England; 3 points in Scotland). However, the differences favouring boys are much larger in PISA (21 points in England and Wales; 16 points in Northern Ireland and 14 points in Scotland). This may well reflect a difference in what is tested in TIMSS compared with PISA.

The consistent findings from this analysis are that gender differences are larger for reading than they are for maths; they always favour girls with regard to reading; the difference is not primarily an artefact of the specific tests for reading; the better performance of girls is evident at all stages of education in national examinations; and gender differences (favouring girls) are often higher in Northern Ireland compared with other parts of the UK.

In , we show differences according to socio-economic status in each country. In the national data sets (Table ), we use eligibility for free school meals as the relevant indicator. We consider differences across country as shown in the Millennium Cohort Study (age 7 reading and maths) and for the main GCSE indicator (five or more GCSEs at A∗–C). In the international data sets (Table ), we compare the PISA maths and reading score within each quartile of disadvantage.

Table 7. Socio-economic inequalities in education: national data.

Table 8. Socio-economic inequalities in education: international data.

All indicators show very large differences according to socio-economic status, as measured by pupils’ eligibility for free school meals, within each country of the UK. Even if we look at the earliest indicator (age 7 scores in reading and maths in the Millennium Cohort Study), a difference is far more evident than when we either looked across countries (Table ) or by gender (Table ). The difference is higher in reading than in maths – varying (in favour of pupils from better-off backgrounds) between 4.4% in Scotland to 7.4% in Wales; but is also evident in maths – varying between 2.6% in Scotland to 5.1% in England. The difference is even starker if we consider differences in the proportion of pupils attaining the GCSE measure, and is especially high in Wales and Northern Ireland (32.6% and 29.4%, respectively). When we look at international PISA data (for which the data are both available and comparable across all four countries), we also see stark differences in performance between students across the distribution of socio-economic status within each country. The difference between the highest (most advantaged) quartile and the lowest is nearly one standard deviation according to tests in both reading and writing (although not as big in Wales). This is a huge difference and puts differences by either country or gender into a new perspective. The OECD difference (shown in the last column) suggests that the UK is not unusual in facing such a high degree of inequality according to socio-economic status. However, when we consider the attention that is given to the performance differential between England and Finland (the top European performer in PISA) – and realise that this difference is only half as large (half a standard deviation) – this suggests that we should be even more concerned about large socio-economic differences within countries. This is a problem that all UK counties have in common. Wales only looks better according to this indicator because the difference at the top of the distribution is more accentuated (relative to other UK countries) than at the bottom. However, performance in Wales is lower within each quartile.

Although the above analysis has highlighted some interesting differences between countries, it has shown that similarities are more striking than differences. Furthermore differences within countries are more important (at least when we consider socio-economic status) that between them.

5 Evaluation evidence

In the light of the discussion of similarities and differences between countries of the UK, both in terms of their institutions and measured performance (as well as educational inequality), we now move on to discuss some evidence on policy, in terms of what works and where possible in terms of value for money (earlier reviews of some of the policies we consider are given in Machin and Vignoles Citation2005, and Machin and McNally Citation2012). We organise this discussion using the same themes as have been used in Section 2 to describe the institutional setting: school type; choice and competition; educational resources; and pedagogy.

5.1 School type

We described two important differences across the UK in Section 2: Northern Ireland has a ‘selective system’ (segregating pupils by ability into different school types at age 11) whereas the other countries UK have a comprehensive model. Secondly, we drew attention to the efforts to create diversity within the comprehensive system in England.

The examination of national and international data sets described above does not reveal very much difference in terms of outcomes between Northern Ireland and England (its closest comparison country in terms of curriculum, tests and legislation). The worry with a selective system is that it may separate by ability at too early an age. The type of school environment experienced by those who do not get accepted to grammar school might be inferior – particularly as the UK context of vocational education is less favourable than many other European countries with developed apprenticeship systems. Guyon, Maurin and McNally (2012) evaluate a reform in Northern Ireland that involved an increase in the quota set by grammar schools. The ‘open enrolment’ reform in 1989 led to an increase in the number of pupils enabled to attend grammar schools by about 15% between one year and the next. For exactly the same cohort of pupils, they observe a strong increase in the overall number of students achieving good qualifications in the GCSE examination at age 16 (five or more GCSEs at A∗–C) and at a later stage (i.e. A-levels, at age 18). When comparing local areas within Northern Ireland, they also find that cohorts in areas that were more affected by the reform became much more successful in national examinations than cohorts in areas that were less affected. This result can be interpreted as the combination of three basic effects: the effect of attending grammar school on pupils who would otherwise have attended another secondary school; the effect of losing more able peers on students still attending non-grammar schools after the reform; and the effect of having less able peers on students who would have entered a grammar school even in the absence of the reform. Although it is not possible to identify the specific contribution of each of these effects, the authors provide plausible lower bounds by examining the impact of the reform separately for grammar and non-grammar schools. Thus, the authors are able to rule out negative effects for students who would have gone to grammar school in the absence of the reform. Thus, contrary to fears expressed at the time of this reform, expanding the number of people able to attend grammar schools did not dilute their quality. This evidence is important for Northern Ireland because it suggests that artificially restricting the number of students who can receive the type of education received at grammar school may be limiting the potential of young people.

With regard to diversity of education provision in England, there have been evaluations of the specialist schools programme and the academies programme. Bradley and Taylor (Citation2010) find the impact of the specialist school initiative to have been modest overall (improving GCSE exam performance by less than 1%) but that it had a larger impact in schools with more disadvantaged pupils. Machin and Vernoit (Citation2011) have evaluated the early academies programme in the Labour years of government described above (designed to replace failing schools in disadvantaged areas). They compare average educational outcomes in schools that became academies and similar schools, before and after academy conversion took place. There are three main findings. Firstly, schools that became academies started to attract higher ability students. Secondly, there was an improvement in performance at GCSE exams – even after accounting for the change in student composition. Thirdly, to an extent, neighbouring schools started to perform better as well. This might be either because they were exposed to more competition (and thus forced to improve their performance) or it might reflect the sharing of academy school facilities (and expertise) with the wider community. However, as discussed in Section 2, the academies programme has been significantly widened, with any state school in England now able to apply for academy status. It is, as yet, too early to evaluate the impacts of this new model.

The case of faith schools provides a further example of diversity, and also autonomy. Many faith schools are voluntary aided and have greater autonomy than other state schools (e.g. there is less representation from the local authority on the board of governors; they control their own admissions, although they must adhere to the Code of Practice). However, Gibbons and Silva (Citation2011) find that most of the positive performance differential in primary faith schools diminishes once other factors have been taken into account. There is a small, residual differential that occurs for autonomous schools only (e.g. Voluntary Aided schools). They attribute this to the admissions and governance arrangements in those schools.

In view of the need to raise attainment of pupils in the lower quartile, the experience of creating diversity within the English school system seems to have been positive. Whether or not this will continue under the new Academies programme (where disadvantaged schools are no longer a specific target) is an open question.

5.2 Choice and competition

As discussed in Section 2, giving parents more choice and creating incentives for schools to compete via the publication of ‘league tables’ has been particularly emphasised within England. While the measures published in these league tables can be helpful to parents, they may also be misleading. This can arise for statistical reasons – for example, value added measures can be quite unstable over time and the fluctuation is often not informative about actual changes in school quality (Leckie and Goldstein Citation2011). Another potentially negative consequence of measuring school quality is that it might encourage behaviour designed to look good on the actual measures while not really improving school quality (or actually neglecting aspects of school quality that are not measured). For example, teachers might concentrate attention on students who are close to the performance threshold and ignore students further away from it. They might teach only what is on the test and ignore broader aspects of education. They might encourage students to take ‘easy courses’ rather than courses that would stretch them. These sorts of behaviours have been documented both in the US and England (Muriel and Smith Citation2011). To the extent that ‘teaching to the test’ and encouragement to take ‘easy courses’ happens more in England than in other countries of the UK, we need to be cautious about interpreting differences in GCSE performance across countries. This is one reason why looking at international test measures is more informative.

Even when the information provided is useful, parents might have limited ability to act on it. While parents can apply to any state school (since the 1980s), schools are permitted to discriminate if there is over-subscription and according to an enforced Code of Practice. The most important over-subscription criterion is usually proximity to the school. As discussed above, there is evidence from England and other countries that parents act on available information when they are purchasing a home (for England, see Burgess et al. Citation2009; Gibbons and Machin Citation2003; Gibbons, Machin and Silva Citation2012; Machin Citation2011; Rosenthal Citation2003). Of course, the link between choice and parental income means that many parents are unable to exercise meaningful choice because of their lower income (i.e. they cannot afford to live very close to a popular school). Furthermore, West and Pennell (Citation1999) show that higher socio-economic groups have better information and understanding of school performance. Thus, ‘school choice’ (although good in itself) is a blunt instrument for addressing attainment gaps by family background.

Parental choice and incentives for schools to perform well should give rise to competition between schools. In the international literature, there have been many attempts to investigate whether increased competition gives rise to improved educational attainment. However, the international evidence is ‘voluminous and mixed’ (Gibbons, Machin, and Silva Citation2008) and there are few papers in England. Bradley, Johnes, and Millington (Citation2001) look at this at school-level (for secondary schools) and find that schools with the best examination performance have grown more quickly. They argue that increased competition between schools led to improved exam performance. It may be the case, however, that as popular schools increase in size, their performance may begin to fall – for example, larger schools may suffer from higher truancy rates as monitoring individual pupils becomes more difficult. However, Bradley and Taylor (Citation2010) find that school size is positively related to exam performance, while Bradley, Johnes, and Millington (2001) find a positive relationship between school size and efficiency.

The first pupil-level analysis on this subject relates to primary schools in the South East of England (Gibbons, Machin, and Silva Citation2008). The authors find no relationship between the extent of school choice in an area and pupil performance. The study also suggests that there is no causal relationship between measures of school competition and pupils’ educational attainment.

5.3 School resources

As discussed above, there are differences across the UK in how much is spent on schools (as measured by the pupil teacher ratio) – with relatively more being allocated in Scotland and relatively less in Wales. How important is this for raising educational attainment generally, and in particular for low socio-economic groups?

Within the UK, the best evidence on this is for England, as there is greater data availability for researchers (although recent data for Wales is also good). The difficult empirical issue in this area of research is that additional school resources are often disproportionately allocated to disadvantaged students. Unless this is fully dealt with in the methodological design, the relationship between resources and attainment is easily obscured.

Two studies that evaluate the relationship between expenditure and attainment in secondary school are by Levăcić et al. (2005) and Jenkins, Levăcić, and Vignoles (Citation2006). They look at outcomes at age 14 (end of Key Stage 3) and age 16 (end of Key Stage 4, GCSE), respectively. Both studies find a small positive effect of resources on pupil attainment. In addition, Machin, McNally, and Meghir (Citation2004, Citation2010) evaluate a flagship policy of the Labour government in the early 2000s – the Excellence in Cities (EiC) programme for English secondary schools. In this programme, schools in disadvantaged, mainly urban, areas of England were given extra resources to try to improve standards. Initially most of the funding was directed at core strands (Learning Support Units; Learning Mentors; a Gifted and Talented Programme). Over time, schools were allowed greater flexibility in how to use the funding. Similarly to the study by Levăcić et al. (2005), they find evidence for small average effects of additional resources for maths but not for English. The authors attempt a cost-benefit analysis of the programme and find it to break-even on the assumption that improvement in Key Stage 3 results corresponds to years of schooling in the way suggested by the National Curriculum.

There have been two recent papers about the effects of school expenditure in primary schools (Holmlund, McNally, and Viarengo Citation2010; Gibbons, McNally, and Viarengo Citation2011). Holmlund, McNally, and Viarengo (Citation2010) use the National Pupil Database between 2002 and 2007 – a period in which there was a large increase in school expenditure in England. They find evidence of a consistently positive effect of expenditure across subjects. The magnitude is a little bigger than that found for secondary schools but still modest. Gibbons, McNally, and Viarengo (Citation2011) look at schools in urban areas that are close to local authority boundaries (where there are more disadvantaged children than the national average). The analysis makes use of the fact that closely neighbouring schools with similar characteristics can receive very different levels of core funding if they are in different education authorities. This is because of an anomaly in the funding formula that provides for an ‘area cost adjustment’ to compensate for differences in labour costs between areas whereas in reality teachers are drawn from the same labour market and are paid according to national pay scales. The study shows that the expenditure difference between schools on either side of local authority boundaries leads to a sizeable differential in pupil achievement at the end of primary school. For example, for an extra £1000 of spending, the effect is equivalent to moving 19% of students currently achieving the target grade in maths (level 4) to the top grade (level 5) and 31% of students currently achieving level 3 to level 4 (the target grade). If National Curriculum levels can be translated into years of schools (i.e. a one-level improvement has been interpreted as equivalent to two years of schooling), and that each extra year of schooling has an estimated benefit over the lifetime of £20,000 (from labour market earnings), the cost of additional school resources can be easily justified in a cost-benefit framework.

The studies looking at resource effects for primary schools (Gibbons, McNally, and Viarengo Citation2011; Holmlund, McNally, and Viarengo Citation2010) find that effects are substantially higher for economically disadvantaged students. For secondary schools, both Machin, McNally, and Meghir (Citation2010) and Levăcić et al. (2005) find that resource effects are higher for disadvantaged students (although this is not found by Jenkins, Levăcić, and Vignoles Citation2006). These findings are encouraging for policy because they suggest that mechanisms have been in place to ensure that disadvantaged students benefit disproportionately from increasing school resources. This helps to reduce the attainment gap between socio-economic groups from what it might otherwise be. On the other hand, it is interesting that both Machin, McNally, and Meghir (Citation2010) and Levăcić et al. (2005) find that high ability students from disadvantaged backgrounds are most likely to benefit from these policies. Machin, McNally, and Meghir (Citation2010) highlight a particular group of concern – low ability students from disadvantaged backgrounds. These are ‘hard to reach’ students who may require more resource-intensive programmes.

Taken together, this research suggests that increasing school expenditure improves attainment and that it is more beneficial for disadvantaged groups (at least on average). It suggests that targeting resources on disadvantaged groups might be beneficial for helping to reduce inequality in educational outcomes.

5.4 Pedagogy

Finally, with regard to evidence on pedagogy (in relation to the literacy and numeracy strategies in England), we can draw on evidence from the de-facto pilot of the national literacy strategy (‘the National Literacy Project’ – evaluated by Machin and McNally Citation2008) and comparisons between England and Wales with regard to the national strategies. For Scotland, we can discuss evidence on the Clackmannanshire project, which implemented synthetics phonics.

Machin and McNally (Citation2008) evaluate the ‘literacy hour’ using schools that implemented the ‘pilot’ vis-à-vis a suitably defined comparison group. The results point to a significant impact of the literacy hour with there being a 2–3% improvement in the reading and English skills of primary school children affected by the introduction of the policy (estimated at only £25 per pupil, representing excellent value for money).

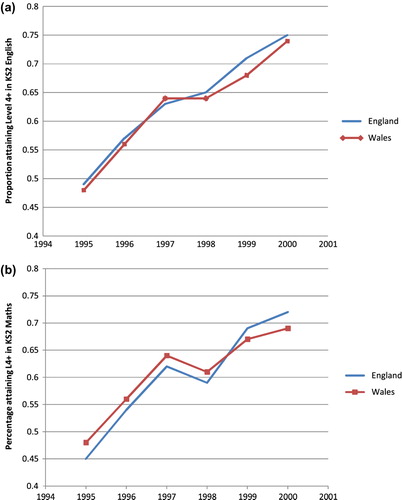

A simple way to compare the potential effect of the strategies in England compared with Wales (which did not implement them nationally) is to compare trends in Key Stage 2 attainment in maths and English.Footnote 6 This is shown in Figure . Figure shows almost no distinction in either the level or the trend of attainment in English between 1995 and 1998. However, there was a significant relative improvement for England at exactly the time that the National Literacy Strategy was introduced (i.e. observable from 1999 onwards). A similar story can be told for attainment in maths (Figure ) except that Wales was better performing prior to 1999. Also, the relative improvement in England happened one year before the official implementation of the Numeracy Strategy. However, there are good reasons to believe that most schools adopted the ‘numeracy hour’ the year before the official start date. The teachers knew that they would have to implement the numeracy hour one year earlier and the framework for teaching was also available at this time. The first part of teaching training was also completed between 1998 and 1999. According to Brown, Bibby, and Johnson (Citation2000), around 70% of primary schools were thought to have introduced the ‘numeracy hour’ a year before the official start. When the results were published in September 1999, the then Education Secretary, David Blunkett, congratulated ‘all those teachers and pupils …, who brought the Daily Numeracy Lesson in early’. While this comparison does not prove definitively that the national literacy and numeracy strategies were responsible for the divergence in achievement around this time, these graphs are strongly indicative.

Figure 1 Comparison between England and Wales (1995–2000): (a) proportion achieving level 4 or above in English (Literacy Hour introduced nationally for exam year 1998); (b) proportion achieving level 4 or above in maths (Numeracy Hour introduced nationally for exam year 1999; but implemented in many schools one year earlier).

Finally, research about synthetic phonics in Scotland (Johnston and Watson Citation2005) has been incredibly influential in England. Following the Rose Review, a method of teaching synthetic phonics has been gradually rolled out to all schools in England. The first phase was a 16-week programme implemented within 13 classes in eight schools in Clackmannshire. The classes were divided into treatment and control groups and the study was conducted by a randomised control trial. In the second phase, the classes in the control group were given the synthetic phonics programme, completing it by the end of their first year in school. This cohort was followed through to the end of their primary school career. Their findings were that children were significantly (and sizeably) above their chronological ages in various aspects of reading. In an interesting critical review of this study, Ellis (Citation2007) points out various other factors that need to be taken into account. This includes the fact that the relevant cohort benefited from several other initiatives as well over their time in school. Hence, there are some difficulties in attributing the results to the sole effect of the early phonics programme (and hence generating robust estimates of the value for money of this programme). Furthermore, the experimental design is really only valid for the first 16 weeks, while the control group does not get treatment. Nonetheless, this is an interesting study, particularly in how it has gone on to influence policy within England.

6 Conclusions

In this paper, we discuss differences and similarities in education structures, policies and outcomes in the four nations of the United Kingdom. Perhaps not surprisingly, given the history of education in the UK, there are clear similarities, and the international position of the four countries in terms of overall educational performance is quite similar in a number of dimensions.

However, in the recent past the education policies and reforms adopted by England have been different from the other countries, in particular with an increased reliance on market mechanisms and on educational innovations at different stages of schooling. It is therefore interesting to ask whether the evaluation evidence of these English reforms is useful in terms of what can be learned for the other nations. The policies that seem to have worked best in England are those where a need for intervention can be identified (e.g. because things were not working well beforehand). Thus, one needs to be careful to recognise that the scope of such policies and reforms to generate educational improvements is place and context specific. But the fact that the four nations do have strong similarities in some aspects of their education structures does mean that, where this context is similar, the positive evidence from economic evaluations of some of the English education policies may well have relevance for education in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland.

Evaluating the education policies of the four nations in terms of value for money – and therefore whether they have scope to be adopted – represents a bigger challenge. Whilst the value for money of certain policies – such as the literacy hour – can be reasonably well measured, for many other policies, value for money is hard to pin down accurately. For example, the increased focus on marketisation, choice and competition in England is very difficult to cost. Moreover, measuring the monetary and wider returns to such policies in an accurate way is difficult and takes some time to observe.

However, this forms an important direction for future research. So too is the need for evaluation researchers to collect good quality cost data when policy interventions are designed and implemented as a key part of the evaluation process.

Notes

1. Scotland is more similar to the Republic of Ireland in this respect.

2. The transfer test at age 11 (‘the Eleven Plus’) has been abolished very recently. However, the majority of grammar schools now set their own entrance exams. This means that rather than only sit one transfer test, students need to take multiple entrance exams.

3. School ‘league tables’ were abolished in Wales in 2003. Since then such information is only published by individual local authorities about their own schools.

4. BBC News online, ‘Wales–England school funding gap is £604 per pupil’, BBC, 26 January 2011.

5. The various data sources we use in the paper are described in detail in the Data Appendix.

6. It is more reliable to compare Key Stage 2 attainment between 1996 and 2000 than after 2000 because in the following year, a distinct mathematics curriculum was introduced for the first time in Wales (Jones Citation2002).

References

- Bradley , S. , Johnes , G. and Millington , J. 2001 . The Effect of Competition on the Efficiency of Secondary Schools in England . European Journal of Operational Research , 135 : 545 – 568 .

- Bradley , S. and Taylor , J. 2010 . Diversity, Choice and the Quasi-Market: an Empirical Analysis of Secondary Education Policy in England . Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics , 72 : 1 – 26 .

- Brown , M. , Bibby , T. and Johnson , D. C. 2000 . Turning Our Attention from the What to the How: the National Numeracy Strategy . British Educational Research Journal , 26 ( 4 ) : 457 – 471 .

- Burgess , S. , Greaves , E. , Vignoles , A. and Wilson , D. 2009 . Parental choice of primary school in England: What type of school do parents choose? Bristol: The Centre for Market and Public Organisation 09/224 , Department of Economics, University of Bristol .

- Centre for Public Policy for Regions (CPPR). 2009. Spending on School Education, Scottish Government Budget Options, Briefing Series No. 1.

- Ellis , S. 2007 . Policy and Research: Lessons from the Clackmannanshire Synthetic Phonics Initiative . Journal of Early Childhood Literacy , 7 : 281 – 293 .

- Estyn . 2000 . Annual Report of Her Majesty’s Chief Inspector for Education in Wales, 1999–2000 , Cardiff : HMSO .

- Estyn. 2001. The Role of LEAs in Raising Standards of Numeracy. A Summary Report Based on LEA Inspections Conducted during 1999 and 2000. HMI for Education and Training in Wales.

- Gibbons , S. and Silva , O. 2011 . Faith Schools: Better Schools or Better Pupils . Journal of Labor Economics , 29 ( 3 ) : 589 – 635 .

- Gibbons , S. and Machin , S. 2003 . Valuing English Primary Schools . Journal of Urban Economics , 53 : 197 – 219 .

- Gibbons , S. , Machin , S. and Silva , O. 2008 . Competition, Choice and Pupil Achievement . Journal of the European Economic Association , 6 : 912 – 947 .

- Gibbons, S., S. Machin, and O. Silva. 2012. Valuing School Quality using Boundary Discontinuity Regressions. Journal of Urban Economics, forthcoming.

- Gibbons, S., S. McNally, and M. Viarengo. 2011. Does Additional Spending help Urban Schools? An Evaluation using Boundary Discontinuities? CEE Discussion Paper. No. 128. London: London School of Economics.

- Guyon , N. , Maurin , E. and McNally , S. 2012 . The Effect of Tracking Students by Ability into Different Schools: a Natural Experiment . Journal of Human Resources , 47 : 684 – 721 .

- Hills , J. , Brewer , M. , Jenkins , S. , Lister , R. , Lupton , R. , Machin , S. , Mills , C. , Modood , T. , Rees , T. and Riddell , S. 2010 . An Anatomy of Economic Inequality in the UK: Report of the National Equality Panel , London : Government Equalities Office .

- Holmlund , H. , McNally , S. and Viarengo , M. 2010 . Does Money Matter for Schools? . Economics of Education Review , 29 : 1154 – 64 .

- Johnstone, R., and J. Watson. 2005. The Effects of Synthetic Phonics Teaching on Reading and Spelling Attainment. Insight 17, The Scottish Executive.

- Jones , D. V. 2002 . National Numeracy Initiatives in England and Wales: a Comparative Study of Policy . Curriculum Journal , 13 : 5 – 23 .

- Jenkins, A., R. Levačić, and A. Vignoles. 2006. Estimating the Relationship between school Resources and Pupil Attainment at GCSE. Research Report RR727, Department for Education and Skills.

- Leckie , G. B. and Goldstein , H. 2011 . A Note on “the Limitations of Using School League Tables to Inform School choice’ . Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series a , 174 : 833 – 836 .

- Levačić, R., A. Jenkins, A. Vignoles, F. Steele, and R. Allen. 2005. Estimating the Relationship between School Resources and Pupil Attainment at Key Stage 3. Research Report RR679, Department for Education and Skills.

- Machin , S. 2011 . Houses and Schools: Valuation of School Quality through the Housing Market . Labour Economics , 18 : 723 – 729 .

- Machin , S. and McNally , S. 2008 . The Literacy Hour . Journal of Public Economics , 92 : 1141 – 1462 .

- Machin , S. and McNally , S. 2012 . The Evaluation of English Education Policies . National Institute Economic Review , 219 : R15 – 25 .

- Machin , S. , McNally , S. and Meghir , C. 2010 . Resources and Standards in Urban Schools . Journal of Human Capital , 4 : 365 – 393 .

- Machin , S. , McNally , S. and Meghir , C. 2004 . Improving Pupil Performance in English Secondary Schools: Excellence in Cities . Journal of the European Economics Association , 2 : 396 – 405 .

- Machin, S., and J. Vernoit. 2010. A Note on Academy School Policy. http://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/pa011.pdf.

- Machin, S., and J. Vernoit. 2011. Changing School Autonomy: Academy Schools and their Introduction to England’s Education. CEE Discussion Paper. No. 123. London: London School of Economics.

- Machin , S. and Vignoles , A. 2005 . What’s the Good of Education? the Economics of Education in the United Kingdom , Princeton , NJ : Princeton University Press .

- Muriel , A. and Smith , J. 2011 . On Educational Performance Measures . Fiscal Studies , 32 : 187 – 206 .

- Raffe, D., and D. Byrne. 2005. Policy Learning From ‘Home International’ Comparisons. CES Briefing No. 34. Edinburgh: Centre for Educational Sociology, University of Edinburgh.

- Reynolds , D. 2008 . New Labour, Education and Wales: The Devolution Decade . Oxford Review of Education , 34 ( 6 ) : 753 – 765 .

- Rosenthal , L. 2003 . The Value of Secondary School Quality . Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics , 65 : 329 – 355 .

- West , A. and Pennell , H. 1999 . School Admissions: Increasing Equity, Accountability and Transparency . British Journal of Education Studies , 46 : 188 – 200 .

- Wilson, J. 2011. Are England’s Academies more Inclusive or more ‘Exclusive’? The Impact of Institutional Change on the Pupil Profile of Schools. CEE Discussion Paper. No. 125. London: London School of Economics.

Data appendix

Appendix 1. Data sources

The data that appear in this paper were collected by the authors from a number of sources

Official government sources

| • | Department for Education is responsible for education and children’s services in England. | ||||

| • | Scottish Executive is responsible for health, education, justice, rural affairs and transport in Scotland. | ||||

| • | The Welsh Assembly Government is responsible for the Welsh Government is responsible for areas such as health, education, language and culture and public services in Wales. | ||||

| • | Department of Education, Northern Ireland (DENI) is responsible for pre-school, primary, post-primary and special education in Northern Ireland. | ||||

National data sets

| • | The Millennium Cohort Study (MCS) follows the lives of a sample of nearly 19,000 babies born between 1 September 2000 and 31 August 2001 in England and Wales, and between 22 November 2000 and 11 January 2002 in Scotland and Northern Ireland. | ||||

International data sets

| • | Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (TIMSS) is used to measure over time the mathematics and science knowledge and skills of fourth- and eighth-graders. TIMSS is designed to align broadly with mathematics and science curricula in the participating countries. The data in this paper come from TIMSS studies in 2003 (49 participating countries) and 2007 (59 participating countries). See http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/ for more details. | ||||

| • | Progress in International Reading Literacy Survey (PIRLS) provides internationally comparative data about students’ reading achievement in primary school (the fourth grade in most participating countries). The data in this paper come from PIRLS studies in 2001 (35 participating countries) and 2006 (40 participating countries). See http://timssandpirls.bc.edu/ for more details. | ||||

| • | The OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys 15-year-olds in the principal industrialised countries. Every three years, it assesses students’ skills and knowledge as they approach the end of compulsory education. See http://pisa2009.acer.edu.au/ for more details. | ||||

Appendix 2. Definitions

Key Stage 1

Data for all countries are taken from the MCS. The data come from the most recent wave of the study (wave 4) conducted over the period January – December 2008 when the study participants were aged 7. Scores are standardised to have mean 50 and standard deviation 10.

Key Stage 2

Data are taken from official government sources but are only available for England and Wales (definitions of Key Stage 2 are different in Northern Ireland and Scotland). Pupils are tested at aged 11 – in Year 6. Data for Key Stage 2 are expressed as the proportion of candidates in all schools achieving level 4 or above in all schools.

GCSE or equivalent

Data are taken from official government sources. Definitions vary by country as follows:

| • | England (DfE): pre-2004/05 data are expressed as the percentage of 15-year-olds achieving five GCSEs or equivalent at A∗–C; 2004/05 onwards – data are expressed as the percentage of pupils at the end of KS4 achieving five or more GCSES/equivalent at A∗–C. Data are from maintained schools only | ||||

| • | Wales (Welsh statistics office): data are expressed as the percentage of pupils aged 15 who achieved the Level 2 threshold. Figures include attainment at independent schools. | ||||

| • | Scotland (Scottish Executive): data are expressed as the percentage of S4 roll achieving five or more Awards at Scottish Qualifications framework (SCQF) level 4 or better. Pupils are aged 14–15. Data are from publicly funded secondary schools. | ||||

| • | Northern Ireland (DENI): pre-2004/05, data are expressed as the percentage of school-leavers achieving five GCSEs/equivalent at A∗–C; 2004/05 onwards, data are expressed as the percentage of year 12s (pupils aged 15–16) achieving five or more GCSES/equivalent at A∗–C. Data are from all grant-aided post-primary schools in Northern Ireland. | ||||

Staying on rates

Data are taken from official government sources as above. All data are expressed as the percentage 16-year-olds still in full or part-time education (all school types, sixth form colleges, FE and HE).

A levels

Data are taken from official government sources as above. Definitions vary by country as follows:

| • | England: pre-2005, data are expressed as the percentage 18-year-olds with two or more GCE/VCE A level or equivalent; 2005/06 onwards data are expressed as the percentage 18-year-olds achieving two or more passes of A level equivalent size (all schools and FE colleges) | ||||

| • | Scotland: data are expressed as the percentage of the S4 year group achieving five or more Awards (Higher or better) at SCQF level 6 (publicly funded secondary schools) | ||||

| • | Wales: data are expressed as the percentage of 18-year-olds achieving Level 3 or more (equivalent to two or more A-levels) (maintained secondary schools, special schools and Pupil Referral Units) | ||||

| • | Northern Ireland: data are expressed as the percentage of 18-year-olds achieving two or more A-levels (including equivalents) | ||||

Reading and maths scores of 10 and 15-year-olds

Data are taken from PISA, PIRLS and TIMSS. Participating countries vary by year and by study. Scores are standardised so that the mean across all participating countries within each dataset is 500, and the standard deviation is 100.