ABSTRACT

Background

Teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience are frequently used constructs when discussing and researching teachers’ work and lives. However, these terms are often used interchangeably and without clarification, highlighting a need to strengthen both conceptual clarity and understanding of the relationship between wellbeing and resilience in teacher research.

Purpose

To address this need, our discussion paper examines how teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience have been conceptualised and introduces an integrative model that aims to elucidate the relationship between the two.

Sources of evidence and main argument

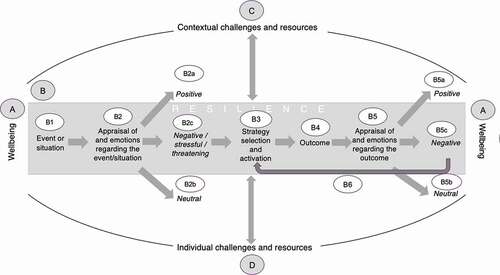

First, we reviewed papers that addressed teacher wellbeing as well as teacher resilience during the last 10 years. In terms of their relationship, we identified four different positions. The most prominent position was that teacher resilience supports the maintenance and development of teacher wellbeing. Second, based on these findings, we developed the Aligning Wellbeing and Resilience in Education (AWaRE) model to specify the relationship between the two constructs and the key aspects of a resilience process. We explain the framework, the individual components of the model and outline the crucial role of appraisals and emotions within the resilience process. We also discuss how this model contributes to the field and may be used as a framework for future research.

Conclusion

The AWaRE model describes a resilience process that is embedded in contextual as well as individual challenges and resources. Within the process, the individual teacher aims at maintaining, restoring and developing their wellbeing. Further research is needed, including empirical validation of the model across the teaching profession. However, the AWaRE model is proposed as a useful tool that can help to clarify the constructs of resilience and wellbeing in educational contexts, and can assist educational practitioners to better understand the resilience process.

Introduction

The ability to maintain wellbeing and respond resiliently to professional challenges is recognised as a valuable capacity for teachers. The literature has widely supported this claim, with a burgeoning amount of research in the fields of teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience over the past 10 years (see, for example, Collie et al. Citation2015; Day and Gu Citation2014; Mansfield Citation2021; Rahm and Heise Citation2019). Although the terms “resilience” and “wellbeing” are widely used, the conceptualisation of these constructs can, in general, appear quite limited, and there may be a lack of explanation of the relationship between the two. This is perhaps not surprising since both constructs are dynamic, complex in nature and conceptualised as multi-dimensional. Given that the fields of research concerning teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience are moving rapidly, we feel that it is timely to consider within this context how each construct has been defined and the relationship between the two, potentially bringing greater coherence to teacher research (Tweed, Mah, and Conway Citation2020).

Teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience are broad constructs used in various disciplines and research areas, and are often studied together. Thus, the benefits of a clearer delineation between them, while acknowledging their interrelatedness, would enable a deeper understanding of these two crucial sources of teacher professional and personal development. This could build greater knowledge about strategies to support teachers in dealing with professional demands and, more specifically, working in challenging situations.

Purpose

With these considerations in mind, the first aim of this paper is to provide a brief overview of the key conceptualisations of teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience and to review how these constructs are related in empirical research. The second aim is to propose a model for understanding the relationship between wellbeing and resilience in the context of the teaching profession that explains the role of teacher resilience in maintaining and restoring teacher wellbeing. The significance of our contribution lies in unpacking and creating a richer understanding of the two constructs and their relationship. This may serve as a basis for new projects and support research that examines the development of teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience. The model can also be used in teacher education and professional learning settings to promote awareness of teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience processes.

Reviewing the literature

Conceptualisations of wellbeing and resilience

Wellbeing and resilience are well-known psychological constructs that are discussed across various disciplines. Prominent definitions of wellbeing root back to Ed Diener’s (Citation1984) early definition of (general) psychological wellbeing, consisting of various cognitive and affective factors such as satisfaction as well as positive and negative emotions. Wellbeing is broadly understood to result from a subjective (positive) evaluation of the quality of life (Deci and Ryan Citation2008).

The understanding of resilience is inspired by Ungar (Citation2012) who defined (general) resilience as a process whereby individuals harness personal and contextual resources in order to successfully navigate challenging circumstances. Like wellbeing, resilience is a multidimensional construct involving activation of multiple personal and contextual resources.

Thus, wellbeing and resilience are distinct constructs, albeit with some similarities. With regard to teacher wellbeing and resilience, both constructs have been shown to have positive outcomes for teachers, including teaching and learning quality, teacher self-efficacy, commitment, and job satisfaction (e.g., Day and Gu Citation2014; Schleicher Citation2018). It can also be seen that teacher wellbeing is important in the resilience process, as a state of more positive wellbeing will influence how teachers interpret and respond to challenges, as well as being an important outcome of the resilience process (Mansfield et al. Citation2016). In the sections below, we consider conceptualisations of teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience separately, before turning attention to the relationship between the two.

Teacher wellbeing

In recent years, attention has been increasingly drawn to the issue of teacher wellbeing. Accordingly, there has been growing scientific interest in studying the wellbeing of teachers. This has led to a range of different conceptualisations, due to diverse disciplinary and methodological perspectives (for an overview, see McCallum et al. Citation2017). For example, whereas Cenkseven-Önder and Sari (Citation2009) refer to teacher wellbeing as general wellbeing that consists of satisfaction with life and positive versus negative affect, Capone and Petrillo (Citation2018) define wellbeing as mental health, and Aldrup et al. (Citation2018) refer to teacher wellbeing as the relationship between work-enthusiasm and emotional exhaustion.

Thus, the resultant heterogeneity of definitions risks a blurred conceptualisation of the construct of teacher wellbeing. Aiming at conceptual clarification, we first argue that an understanding of teacher wellbeing calls for an understanding of the term wellbeing itself. The early work of Diener on general well-posedness (e.g., Diener Citation1984), with the notion of a relationship between positive and negative dimensions to describe the complex construct of wellbeing, provides a major contribution in this regard. Here, wellbeing is defined as an individual’s multi-layered and subjective evaluation of their life that results in a positive judgment. Following this approach, we make the assumption that teacher wellbeing results from a teacher’s evaluation of their professional life as one that achieves what we describe as a positive imbalance. This means that positive and negative aspects may coexist but the positive dimensions are more pronounced than the negative ones (e.g., Bradley et al. Citation2018). For example, when teachers experience more positive than negative emotions in interactions with students and parents, they sense a deeper feeling of professional meaningfulness. Even though there may be simultaneous demands and conflicts, they feel positive even when some job-related issues might occur. This definition implies that the construct of teacher wellbeing could be adequately described by neither the sole absence of negative aspects, such as worries and concerns related to a teacher’s work, nor the sole presence of positive emotions or satisfaction. This definition also implies that teacher wellbeing is an integral part of a teacher’s professional life. As such, it serves as an indicator of a successful fulfilment of the professional role and meaningfulness, which highlights the eudemonic or meaning-oriented (instead of hedonic or pleasure-oriented) character of teacher wellbeing (Deci and Ryan Citation2008; Dolan and Metcalfe Citation2012). Thus, a teacher’s wellbeing goes beyond single aspects of cognitive and affective evaluation of a situation such as pleasure and can be viewed as “a complex construct that concerns optimal experience and functioning” (Deci and Ryan Citation2001, 141).

Second, we argue for the need for a more domain-specific approach to teacher wellbeing. Teacher wellbeing is most frequently described as a complex, multidimensional construct, simultaneously comprising various elements, such as the experience of satisfaction and positive emotions and the absence or relatively fewer experiences of negative emotions and complaints. However, a criticism that may be levelled here is that these elements are not necessarily related to the teaching profession per se, but rather address a general construct relevant to all individuals (e.g., life-satisfaction). A weakness of the research field may therefore be that many approaches to teacher wellbeing suffer from the lack of a domain-specific perspective (Hascher and Waber (submitted)). Thus, we argue for a more domain-specific approach that investigates the factors that can support or impede teacher wellbeing. Among these would be contextual factors, such as class composition, school climate, collegial support or educational resources, and individual factors, such as tenure, professional competence, self-regulation skills and resilience (for an overview, see, for example, McCallum et al. Citation2017).

Teacher resilience

Research examining teacher resilience has also burgeoned over the past 15 years (Mansfield Citation2021). The construct of resilience has been examined from multiple perspectives using a variety of methodologies (Beltman and Mansfield Citation2018). As with the conceptualisation of teacher wellbeing and wellbeing in general, we argue that an understanding of teacher resilience calls for an understanding of resilience in general. In addition to focusing on the resilience capacities and processes for individuals, definitions of resilience have broadened to systemic ones. For example, Masten (Citation2014, 10) defined resilience as “the capacity of a dynamic system to adapt successfully to disturbances that threaten system function, viability, or development”. A system may refer to an individual, but could be ”a family, a school, a community, an organization, and economy, or an ecosystem” (Masten Citation2014, 10). Within such a system, resilience is the process of harnessing resources in order to adapt successfully (Ungar Citation2012).

Similarly, conceptualisations of teacher resilience have expanded from an individual, psychological focus to an understanding of resilience as not only a capacity but also a process and an outcome too. Gu and Li (Citation2013, 300) argue that resilience in educational contexts is not simply an innate characteristic but is “influenced by individual qualities in interaction with contextual influences in which teachers’ work and lives are embedded”. Current views of teacher resilience thus focus on an individual teacher, but crucially with recognition that the teacher is living and working within multiple, dynamic and changing contexts (Day and Gu Citation2010).

The multidimensional nature of resilience is evident in that to operationalise resilience, researchers have measured a variety of constructs such as self-efficacy, emotional intelligence, teacher–pupil relationships, workload, school culture and support, and student behaviour (e.g., Ainsworth and Oldfield Citation2019) – in order to better understand the importance of personal and contextual factors. Outcomes of resilience such as professional commitment, job satisfaction, engagement and wellbeing have also been identified (e.g., Cook et al. Citation2017; Gu Citation2014). Recent research in teacher resilience has drawn on Ungar’s (Citation2012) comprehensive definition of resilience to highlight the socio-ecological influences on resilience:

Where there is potential for exposure to significant adversity, resilience is both the capacity of individuals to navigate their way to the psychological, social, cultural, and physical resources that sustain their wellbeing, and their capacity individually and collectively to negotiate for these resources to be provided in culturally meaningful ways.

Understanding the relationship between teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience

In order to identify and understand how teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience have been aligned in the field of educational research, we reviewed recent publications that addressed both teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience. A literature search covering the time frame of January 2010 to June 2020 yielded 81 peer-reviewed research articles with ERIC and SCOPUS that included the keywords “teacher wellbeing” (“teacher well-being”, “well-being of teacher(s)”) and “teacher resilience” (“resilience of teacher(s)”) in titles, abstracts and/or keywords. From these, two papers were excluded because they addressed student, rather than teacher, wellbeing and resilience. Furthermore, in nine papers, only teacher wellbeing (e.g., Lauermann and König Citation2016; Logan, Cumming, and Wong Citation2020; Moè Citation2016; Song, Gu, and Zhang Citation2020; Spilt, Koomen, and Thijs Citation2011) was addressed; in four papers, only teacher resilience (Buchanan et al. Citation2013; Gu and Day Citation2013; McGeown, St Clair-Thompson, and Clough Citation2015) was addressed. Among the remaining 66 papers, 21 papers provided no explicit clarification of how teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience might be related (e.g., Carroll et al. Citation2020; Leroux and Théorêt Citation2014; Price and McCallum Citation2014; Taylor Citation2013; Wabule Citation2020; Wood, Ntaote, and Theron Citation2012). The final 46 papers (see ) included theoretical as well as empirical papers applying qualitative, quantitative or mixed research methods. One review article was also included. Due to our central focus on the theoretical conceptualisations of the relationship between teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience, evaluation of the empirical quality of the research papers (e.g., regarding the representativeness of the sample) was not in scope. Instead, our aim in analysing this body of research was to identify and systematise explicit or inferred statements of how teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience were interlinked, according to our interpretation of the conceptualisations in the papers. In order to construct an overview, we extracted all relevant statements from the texts and clustered the papers based on similar approaches. This method revealed four main ways that teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience were related in the literature that we analysed.

First, it is evident from our analysis that various studies appeared to treat teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience as similar constructs. For example, teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience were used interchangeably when they were mentioned as important issues for teachers (e.g., Gibbs and Miller Citation2014) or when they were attributed to the same outcomes (Larson et al. Citation2018). In some studies, factors such as positive emotions were described as equally impacting teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience without differentiation (Critchley and Gibbs Citation2012; Roffey Citation2012). Likewise, some studies discussed strategies for supporting both teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience, such as mindfulness (Wells and Klocko Citation2018). Elsewhere, teacher resilience and teacher wellbeing have been identified as related (Ballantyne and Zhukov Citation2017); their indicators defined as correlated (Fernandes et al. Citation2019) or teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience are expected to relate similarly to a third construct (Papatraianou and Le Cornu Citation2014). In the above approaches, the unique aspects of the constructs “teacher wellbeing” and “teacher resilience” were not highlighted.

In a second group of studies, teacher resilience and wellbeing were regarded as components of each other. For some, teacher resilience was a part, an indicator or a component of teacher wellbeing (Acton and Glasgow Citation2015; Noble and McGrath Citation2015). Other studies, however, argued that teacher wellbeing was a part or indicator of teacher resilience (Soini, Pyhältö, and Pietarinen Citation2010). Both approaches have in common that they define one construct as including the other. However, the theoretical rationale for the different hierarchical relations (e.g., wellbeing as superior or subordinate) remains unclear.

According to our analysis, a third group of studies viewed teacher wellbeing as a predictor being relevant for the development and/or improvement of teacher resilience. In these studies, teacher wellbeing was regarded as a general precondition or supporting factor that enables teacher resilience to mature (Gray, Wilcox, and Nordstokke Citation2017). Others argued that the application of wellbeing strategies and skills leads to teacher resilience (Lester et al. Citation2020). Thus, teacher wellbeing was understood as a resource that nourishes teacher resilience.

In the fourth group, the role of teacher resilience in the maintenance and development of teacher wellbeing was highlighted in the majority of studies. Teacher resilience was viewed as a capacity to maintain, to lead to or to restore teacher wellbeing (e.g., Clarà Citation2017; Johnson and Down Citation2013). Teacher resilience was regarded as a protective factor of teacher wellbeing (e.g., Burić, Slišković, and Penezić Citation2019) and some studies contended that successful teacher resilience intervention programmes led to improvements in teacher wellbeing (Beshai et al. Citation2015; Cook et al. Citation2017; Griffiths Citation2014; Johnson et al. Citation2014; Mahfouz Citation2018). However, some specifications have to be made, as Pretsch, Flunger, and Schmitt (Citation2012) found that the role of teacher resilience for teacher wellbeing may not hold for all aspects of teacher wellbeing: i.e., teacher resilience can serve as a predictor of only some dimensions of teacher wellbeing. Additionally, they suggested that the role of resilience for wellbeing was more pronounced for the teaching profession in comparison to other professions (e.g., engineering, media design and sales). Other papers discuss how positive adaptivity (Ainsworth and Oldfield Citation2019; McCallum et al. Citation2017), balance of demands and resources (Simmons et al. Citation2019), the strengthening of various resources or overcoming of challenges (Owen Citation2016) mediated the possible effect of teacher resilience on teacher wellbeing. The current paper aligns with this view, and while all studies in this group stress the influential role of teacher resilience for teacher wellbeing, the process by which this influence occurs needs further elaboration.

Our review of the current literature reflects the valuable scholarship in this area. It highlights, too, the challenges of conceptualisation and our contention that the relationship between teacher resilience and teacher wellbeing is highly complex. Although a relationship between these constructs may be demonstrated, there is little consistency of conceptualisation or operationalisation across the board. The majority of the reviewed papers argue that resilience is important for the maintenance and development of teacher wellbeing; however, how this may occur is not clear. Thus, in the section of the paper following, we propose a model that aims to contribute to the understanding of the relationship between teacher resilience and teacher wellbeing.

A proposed model

Aligning wellbeing and resilience in education (AWaRE): an overview

We have drawn on the above literature to develop the AWaRE (Aligning Wellbeing and Resilience in Education) model, which is presented in . Through this model, we sought to offer a contribution to the understanding of the crucial role of teacher resilience in the maintenance and development of teacher wellbeing (i.e., the fourth group identified in the section above). Our model is built on the idea that teacher resilience is an individual process that is situated and mediates between experiences of teacher wellbeing, namely at the beginning and at the end of the resilience process (see A in ). The AWaRE model shows a resilience process that is framed by challenges and resources at the contextual (see C in ) and individual level (see D in ) and nested within a teacher’s experiences of wellbeing (see B in ). The function of this resilience process is to maintain or re-establish wellbeing in the face of challenges, and the function of the AWaRE model is to describe the steps of this resilience process.

Figure 1. The AWaRE (Aligning Wellbeing and Resilience in Education) model

One key assumption guiding the design of the model is that teacher resilience is understood as a “bi-directional person-ecology transaction” (Wood, Ntaote, and Theron Citation2012, 438). As a better understanding of the interplay of the individual with the context is needed when referring to teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience (Johnson and Down Citation2013), the model focuses on the role of the individual during the resilience process but takes transactional processes and the context into account.

Examining the components of the AWaRE model

The following section explains the AWaRE model, and unpacks each of the components of the model, outlining wellbeing (A), challenges and resources (C and D), and the resilience process (B).

Teacher wellbeing as starting point and outcome (A): In the AWaRE model, teacher wellbeing is positioned at either end (see A in ) to show that it is both a starting point and outcome of the resilience process. According to the theory of wellbeing as a multidimensional construct with higher levels of wellbeing indicating a predominance of positive over negative elements (“positive imbalance”), a predominance of negative elements serves as a starting point. If a teacher experiences a “negative imbalance” (i.e., a dominance of negative emotions, feelings and cognition) that corresponds with a negative evaluation of their current situation, the process commences. As an outcome, a teacher’s wellbeing is experienced as a positive imbalance (i.e., a dominance of positive emotions, feelings and cognition) that results from a positive, or at least improved, evaluation of the situation. As argued in the literature, the motivation to maintain and restore wellbeing can be seen as a protective factor against long-term harm and the development of severe complaints such as depression, stress or burnout (e.g., Ainsworth and Oldfield Citation2019; Capone and Petrillo Citation2018; Richards, Hemphill, and Templin Citation2018).

Individual and contextual challenges and resources (C and D): The wellbeing and resilience process in the AWaRE model is framed by personal and contextual challenges and resources (see C and D in ). Although our focus in the model is on an individual teacher with multiple personal characteristics, it recognises that a teacher is situated within multiple, dynamic and changing contexts and that the teacher lives and works within these contexts. Both individual and contextual factors have been analysed in terms of the extent to which they present risks or have a protective function (Beltman, Mansfield, and Price Citation2011). Moreover, contextual aspects are important as they might frame the teacher resilience process within a culture that can differ, for example, with regard to aspects of school qualities such as leadership, cooperation and social relationships. This school culture directly influences the resilience process. Specifically, for early-career teachers, it can make a difference in terms of how schools respond to their challenges and needs (Gray, Wilcox, and Nordstokke Citation2017).

From a social-ecological view of resilience, teachers may face individual challenges (see D in ) and contextual challenges (see C in ) that may lead to a threat to their wellbeing or become an “event” that triggers the resilience process. Well-established examples of personal or intra-individual challenges are low self-efficacy (Kitching, Morgan, and Leary Citation2009) or issues such as poor health (Day and Gu Citation2010). Contextual challenges may include interpersonal ones, such as difficulties in relationships with students, parents or colleagues (Beltman et al. Citation2019). At a broader contextual level, policy changes (Gu and Day Citation2013), assessment and reporting requirements (Johnson et al. Citation2014), or societal expectations (Schelvis et al. Citation2014) may be events that threaten teacher wellbeing.

Similarly, resources may be framed within a social-ecological framework. For teachers, intra-individual characteristics such as a high intrinsic motivation and a sense of competence are related to resilience (Beltman, Mansfield, and Price Citation2011). Contextual, interpersonal aspects of a teacher’s work including supportive colleagues, mentors and school administrators (Day and Gu Citation2014) as well as positive feedback from students and parents (Gu Citation2014) also support resilience. Resources at a broader level of context include school funding, induction programmes, teacher networks and ongoing professional learning opportunities (Day and Gu Citation2014).

We recognise the important roles of the environment and context by incorporating contextual resources and challenges as well as individual resources and challenges equally in the model. Within this interplay, the same setting, or level of context, can offer both challenges and support. For teachers, children in a classroom may present challenges regarding their behaviour or individual needs, but equally they provide enjoyment and a sense of fulfilment when they interact positively or develop skills and understandings. The presence, availability and nature of both challenges and resources can be unique for each individual, as well as for specific locations and for different nations (Gu and Li Citation2013).

Resilience process (B): As experiencing wellbeing is a general need for individuals and the basis for individual functioning and growth (Deci and Ryan Citation2008), individuals strive to maintain or improve their wellbeing and to reduce the factors that impede wellbeing. In the case of impairment of wellbeing, the resilience process (see B in ) will be operating. The following is an overview of the resilience process, and each component is then further elucidated.

Activation of the resilience process (B) is prompted by a single event or situation (a set of factors) that potentially negatively affects a teacher’s wellbeing (see B1 in ). The model is underpinned by the general understanding that, as individuals in general, a teacher aims at maintaining their wellbeing and appraises daily events and situations with regard to their wellbeing (see B2 in ). These wellbeing experiences might be subconscious or partly or fully conscious and are framed by contextual and individual resources and challenges. Should the event or situation seem to be positive (see B2a in ) or neutral (see B2b in ), the process is deactivated because there is no threat to a teacher’s wellbeing. In case of a negative appraisal of the event or situation (see B2c in ), the resilience process is activated or prompted, with the aim being to re-establish wellbeing. This first appraisal is followed by the selection and use of strategies (see B3 in ) that result in an outcome (see B4 in ). This outcome is evaluated through secondary appraisal (see B5 in ) in terms of its effects on wellbeing. A positive (see B5a in ) or neutral appraisal (see B5b in ) will lead to a deactivation of the resilience process. In the case of a negative appraisal (see B5c in ), the resilience process tends to continue by reversing to strategy selection and activation (B3 in ). This reverse loop (see reverse arrow B6 in ) will continue as long as the outcome of the strategy selection and activation is evaluated as negative. As with the experience of wellbeing, the resilience process can operate with different levels of consciousness and, thus, might be beyond an individual’s awareness.

The nature of an event or situation (B1): A key component of the AWaRE model is a representation of an event or situation, which has the potential to disrupt wellbeing (see B1 in ). As noted by Ungar (Citation2012), resilience in general occurs “where there is potential for exposure to significant adversity…” so that the resilience process is connected to exposure to perceived significant adversity. Severe or intense adverse events are regarded by some to be a precondition for resilience. For example, Doney (Citation2012) maintains, “individuals are considered resilient only if there has been a significant threat to their development”. Ebersöhn (Citation2014) states that “resilience only ever becomes pertinent in the presence of significant adversity: succeeding despite considerable risk”. Fletcher and Sarkar (Citation2013, 14), however, suggested that the adversities encountered by adults in daily life may be more modest and may comprise “ongoing daily stressors and highly taxing, yet still common, events”.

In relation to teacher resilience, the AWaRE model is applicable to singular and moderate forms of stressful, negative, aversive or threatening events affecting teachers, such as a difficult discussion with parents or a challenging class, as well as more far-reaching stressors such as a pandemic and its impacts (Wood, Ntaote, and Theron Citation2012). Rather than intensity, the frequency of events is raised most often in the teacher resilience literature because in teaching, “people are confronted with continuing emotional demands” (Pretsch, Flunger, and Schmitt Citation2012, 322). In teachers, then, the resilience process may be activated in the face of “everyday challenges” (Gu Citation2014, 520), as well as in response to “initial, brief spikes” (Gu and Day Citation2013, 40). The section relating to contextual challenges indicates some other situations that may trigger the resilience process.

Whether or not an adverse event is viewed as being significant is criterion-based and determined by the insider (Ebersöhn Citation2014, 571). Returning to Ungar’s (Citation2012) definition of resilience, it should be noted that it begins with the phrase “potential” for significant adversity. Fletcher and Sarkar (Citation2013, 12) highlight that the use of this term in definitions of resilience “is important because it draws attention to the differences in how people react to life events and whether trauma occurs as a result”. The next component of our model, the appraisal process, focuses on this reaction.

An appraisal of the event or situation (B2): The AWaRE model shows that following an event or situation, individuals make appraisals (see B2 in ): a well-documented concept. In this context, appraisals are subjective evaluations of the significance and valence of a situation or an event with regard to individual wellbeing (Lazarus Citation1991). Given the subjective nature of an appraisal process, there are inter- and intra-individual differences. Appraisals are not stable or fixed: they can change and are continuously modified by the individual (e.g., Gross Citation2002). It is widely accepted that there are two forms of appraisal – namely, primary appraisals that are related to the evaluation of the situation as threatening or challenging and secondary appraisals that address an individual’s perceptions of their own capabilities to cope with the situation (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984; Velichkovsky Citation2009). To activate the resilience process, the appraisal of the situation or event needs to be negative or aversive and related to personal threat or stress, to some degree at least (see B2c in ). As in the case of resilience, negative emotions such as anger, anxiety, discontent, shame or guilt can be considered as relevant. Evaluative judgements (e.g., the evaluation of a situation as failure that leads to shame or guilt) as well as anticipated consequences (e.g., evaluation of a situation as potentially harmful for the self-concept or as leading to disapproval) can lead to the experience of negative emotions (see also Clarà Citation2017). In the teaching profession, it has been suggested that self-efficacy beliefs play a role, as they shape teachers’ perspectives and interpretations of an event or a situation (Gibbs and Miller Citation2014). Social embeddedness, represented by relationships that teachers can rely on (Greenfield Citation2015), as well as feelings of control, seems to be important (Grenville-Cleave and Boniwell Citation2012).

Strategy selection and activation (B3): Once an event or series of events has been appraised as negative, stressful or a threat to teacher wellbeing in the AWaRE model, an individual then selects a strategy or strategies designed to restore wellbeing to a level that is appraised as positive by that individual (see B3 in ). In Ungar’s (Citation2012) definition, this is seen as harnessing resources. Thus, strategies are the mechanism by which a teacher taps into personal or contextual resources.

Teachers use a range of strategies in the resilience process and these can be grouped in various ways. For example, a framework for building resilience in pre-service teachers included quite broad strategies such as persistence, emotion regulation, problem-solving and maintaining a work–life balance (Mansfield et al. Citation2016). Other strategies were more specific, such as time management, mindfulness, reflection and help-seeking. When teachers felt their emotions heightened and reported the strategies they implemented to regulate these, it was apparent that strategies could also be grouped into specific categories (Beltman and Poulton Citation2019). The category of waiting incorporated more specific actions, such as taking a deep breath, or stepping away from the situation for a few seconds. Assessing included strategies such as looking at the bigger picture or imagining the other person’s perspective. In the third grouping of problem-solving, actions were those such as talking with collegial networks or selecting a different strategy from the ones already tried to solve the issue. Finally, participants in this study were being proactive in order to be better prepared for future difficult situations. They endorsed strategies such as engaging in a hobby or exercise. Participants reported using multiple strategies, sometimes sequentially, as a way of managing their emotions while addressing the issue that was causing stress.

As well as personal strategies, some research has shown that relational strategies can be important for teachers. Sumsion (Citation2004, Citation2007) found that some individuals are able to achieve changes by engaging in debates and supporting collective action, thus influencing their community. Similarly, in the context of poverty in South Africa, research reports that teachers and whole communities were able to “flock” together ”to change the ability of an at-risk environment to enable resilience” (Ebersöhn Citation2012, 30). Elsewhere, Brouskeli, Kaltsi, and Loumakou (Citation2018) found Greek teachers’ wellbeing and resilience to be above average, despite them facing many societal problems. The notion of collective resilience, where individuals gather together to harness resources (Ungar Citation2012), may also be seen as a proactive, transformational response to adversity (Mintrop and Charles Citation2016). Hence, the bi-directional arrows in the AWaRE model (located between B and C, as well as between B and D, in ) indicate that individual persons and their contexts are mutually shaping each other.

An outcome and an appraisal of strategy use (B4 and B5): In the AWaRE model, the strategy selection and application result in an outcome (see B4 in ). This outcome reflects the effectiveness of the selection and application of strategies as a response to the aversive event or situation. Generally, it can be characterised by a change in the situation, an individual’s modified or new capacities, as well as a modified or new interplay between the situation/event and the individual. This outcome is evaluated by a second cognitive and emotional appraisal process where the individual reflects on the success of strategy use in ameliorating and/or mitigating the stressful, aversive, threatening event or situation (see B5 in ). If the appraisal leads to a perception of a reduced averseness of the event/situation resulting in a neutral (see B5b in ) or even positive evaluation (see B5a in ), the process of wellbeing restoration continues and might finally lead to restoration of perceived wellbeing. If the appraisal of the outcome is still negative (see B5c in ), the process loops back (see B6 in ) to new strategy selection and activation (see B3 in ). Thus, this evaluation process includes, according to the Lazarus model of primary and secondary appraisal (Lazarus and Folkman Citation1984), not only the event/situation itself but the individual’s evaluation of their personal skills and development as well. Individual perception of their new capacity to respond successfully to similar challenges and to solve problems might act as a personal resource in the future.

The model as a whole: In sum, the AWaRE model reveals, in detail, the relationship between teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience, where the aim of the resilience process is to restore wellbeing. The process is framed by contextual and personal challenges and resources, which also influence the process. The model shows a process that is likely to occur if a teacher appraises an event or situation as a threat to wellbeing and draws on personal and contextual resources to select and activate strategies to restore wellbeing – or to continue the process, if a negative secondary appraisal occurs.

Discussion

Our aim in this paper has been to contribute to a clarification of two constructs: teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience. We have provided an overview of key conceptualisations of teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience in the current literature and presented a model illustrating the relations between the constructs. Whilst recognising that teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience each have large, independent bodies of valuable scholarship, we have suggested how these concepts might be interrelated and understood within the teaching profession. From our perspective, both teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience could be described as “slippery” constructs, as they are connected in multiple ways in the literature, operationalised in different ways in empirical work, and examined in a variety of contexts and settings. We have endeavoured to contribute to what is understood about the relation between these constructs in teaching settings.

We have developed the AWaRE model that reflects existing theory and research, as well as our previous work that illustrated the relation between individual and contextual aspects of the resilience process, incorporated resilience-related strategies, and included the role of multiple levels of context (Beltman, Mansfield, and Harris Citation2016; Mansfield, Beltman, and Price Citation2014). We based our thinking on current discussions about the nature and role of teacher wellbeing as a complex subjective process that is embedded into contextual frames (Hascher Citation2010; Hascher and Waber (submitted)). We also draw on models related to coping (Lazarus Citation1991, Citation1999). In the AWaRE model, the resilience process is presented as critical for maintaining, restoring or developing wellbeing in teaching contexts. Despite the different conceptualisations and different settings from which the literature to develop the model was drawn, it provides an overview of the resilience process with wellbeing as its core. It aims to reflect a process and represents the dynamic character of these constructs – and of their interrelation – that need to be empirically investigated in the future.

Limitations

The AWaRE model can be viewed as an initial proposal to clarify the relationship between teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience. We consider the model as a starting point to encourage future research in investigating this relationship in more detail. Further theoretical work and empirical studies aimed at testing the model are needed. However, we recognise, too, that there are limitations in the paper and the model. While we have explicitly focussed on teacher resilience and teacher wellbeing and incorporated work related to appraisals and coping, we have not explicitly compared or related teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience with other constructs, such as, for example, self-efficacy, motivation, persistence, buoyancy or grit (e.g., Duckworth, Quinn, and Seligman Citation2009). A further important step would be to investigate explicitly the connection of teacher wellbeing and resilience with instructional quality and student outcomes – factors that are not present in our model, although the literature indicates that both teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience are associated with quality teaching (e.g., Day Citation2019; Klusmann et al. Citation2008).

There are inherent challenges with a static, two-dimensional representation of multidimensional, multi-level and dynamic constructs such as wellbeing and resilience. Rogoff (Citation2003, 49), for example, discussed the difficulties of the traditional models “using entities connected by arrows or contained in concentric circles”. Such diagrams, perhaps unintentionally, may support the assumption that personal and contextual processes are separate, whereas Rogoff’s view is that these processes mutually create each other, as we maintain in the AWaRE model. It remains a challenge to reflect the complexity and dynamic nature of personal and contextual aspects of teacher wellbeing and resilience in a two-dimensional model.

Implications and future perspectives

Despite its limitations, our work has implications for research and practice. There is a need for research to link other constructs related to personal–social aspects of work and learning, and our model could serve as a template for relating constructs such as wellbeing and burnout, wellbeing and health, resilience and coping, and resilience and buoyancy. As previously indicated, there is still work to do to disentangle further the various components of teacher wellbeing and teacher resilience, and their relation to other constructs, in order to reach consistency of conceptual understanding. Such a clarification has significance for positive psychology as well as other disciplines interested in these topics, such as philosophy (Prinzing et al. Citation2020). This type of endeavour has the potential to stimulate dialogue between different research fields, as well as within and between disciplines. In addition, it can contribute to explaining the mechanisms underlying the effectiveness of intervention programmes such as ACHIEVER or CARE that aim to improve teacher wellbeing through resilience training (Cook et al. Citation2017; Jennings et al. Citation2013). Whether the model would transfer to other professions, such as nursing, or contexts, such as higher education, remains to be explored.

The AWaRE model could have useful applications in teacher education and professional development situations. In particular, it may assist educators to articulate specific challenges and resources and identify strategies that support wellbeing, as well as raising the level of consciousness of the appraisal process. Such reflection is important; “the processes of reflection may have a crucial role in teacher resilience processes” (Clarà Citation2017, 89). While specific challenges and resources may differ for different individuals and at different career stages (Gray, Wilcox, and Nordstokke Citation2017), the process of maintaining wellbeing would be the same for teachers at any level, including those at early career and more experienced stages. The AWaRE model can be used to help teachers to understand the resilience process, which, in turn, can support their own and their students’ wellbeing when they are able ”… to model and to promote the resilience they wish to see in their students” (Cook et al. Citation2017, 14). The AWaRE model may play a helpful role in clarifying the constructs of resilience and wellbeing for the profession: colloquially, they are often used interchangeably.

In addition to individual reflection, the model incorporates context as a crucial element of the resilience process. This points to the significant roles of policymakers, professional learning developers, teaching colleagues, and principals. For example, colleagues may provide social support, or set up mentoring programmes that serve as resources. The model explains the connection with such resources in supporting teacher wellbeing as an outcome of the resilience process.

Conclusion

The search for a deeper understanding of the important role of wellbeing and resilience in the teaching profession, and of the mechanisms by which they are interrelated, lies at the heart of this paper. Wellbeing is regarded as of utmost importance for individuals because a long-term absence of wellbeing can be harmful (e.g., Wood and Josephs Citation2010). Given current concerns about teacher attrition, and the role of health and burnout in teacher retention (e.g., Ryan et al. Citation2017), we need to better understand how to enhance teacher wellbeing as a driving source for personal and professional flourishing. Ultimately, this will contribute to the profession as a whole because it can lead to an empowering of teachers to care for their students, create positive learning environments, commit to the role of education, and support a learning society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest to report.

References

- Acton, R., and P. Glasgow. 2015. “Teacher Wellbeing in Neoliberal Contexts: A Review of the Literature.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 40 (8): 99–114. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2015v40n8.6.

- Ainsworth, S., and J. Oldfield. 2019. “Quantifying Teacher Resilience: Context Matters.” Teaching and Teacher Education 82: 117–128. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.03.012.

- Aldrup, K., U. Klusmann, O. Lüdtke, R. Göllner, and U. Trautwein. 2018. “Student Misbehavior and Teacher Well-being: Testing the Mediating Role of the Teacher-student Relationship.” Learning and Instruction 58: 126–136. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2018.05.006.

- Ballantyne, J., and K. Zhukov. 2017. “A Good News Story: Early-career Music Teachers’ Accounts of Their “Flourishing” Professional Identities.” Teaching and Teacher Education 68: 241–251. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.08.009.

- Beltman, S., and C. F. Mansfield. 2018. “Resilience in Education: An Introduction”. In Resilience in Education: Concepts, Contexts and Connections, edited by M. Wosnitza, F. Peixoto, S. Beltman, and C. F. Mansfield, 3–9. Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://www.springer.com/gp/book/9783319766898. Accessed, September 14, 2021.

- Beltman, S., C. F. Mansfield, and A. Harris. 2016. “Quietly Sharing the Load? the Role of School Psychologists in Enabling Teacher Resilience.” School Psychology International 37 (2): 172–188. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0143034315615939.

- Beltman, S., C. F. Mansfield, and A. Price. 2011. “Thriving Not Just Surviving: A Review of Research on Teacher Resilience.” Educational Research Review 6 (3): 185–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2011.09.001.

- Beltman, S., and E. Poulton. 2019. “’Take a Step Back’: Teacher Strategies for Managing Heightened Emotions.” The Australian Educational Researcher 46 (4): 661–679. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00339-x.

- Beltman, S., M. R. Dobson, C. F. Mansfield, and J. Jay. 2019. “‘The Thing that Keeps Me Going’: Educator Resilience in Early Learning Settings.” International Journal of Early Years Education 1–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2019.1605885.

- Beshai, S., L. McAlpine, K. Weare, and W. Kuyken. 2015. “A Non-randomised Feasibility Trial Assessing the Efficacy of A Mindfulness-based Intervention for Teachers to Reduce Stress and Improve Well-being.” Mindfulness 7 (1): 198–208. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0436-1.

- Birchinall, L., D. Spendlove, and R. Buck. 2019. “In the Moment: Does Mindfulness Hold the Key to Improving the Resilience and Wellbeing of Pre-Service Teachers?.” Teaching and Teacher Education 86: Article 102919. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.102919

- Bradley, C., D. T. Cordaro, F. Zhu, M. Vildostegui, R. J. Han, M. Brackett, and J. Jones. 2018. “Supporting Improvements in Classroom Climate for Students and Teachers with the Four Pillars of Wellbeing Curriculum.” Translational Issues in Psychological Science 4 (3): 245–264. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000162.

- Brouskeli, V., V. Kaltsi, and M. Loumakou. 2018. “Resilience and Occupational Well-being of Secondary Education Teachers in Greece.” Issues in Educational Research 28 (1): 43–60.

- Buchanan, J., A. Prescott, S. Schuck, P. Aubusson, P. Burke, and J. Louviere. 2013. “Teacher Retention and Attrition: Views of Early Career Teachers.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 38 (3): 112–129. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2013v38n3.9.

- Burić, I., A. Slišković, and Z. Penezić. 2019. “Understanding Teacher Well-being: A Cross-lagged Analysis of Burnout, Negative Student-related Emotions, Psychopathological Symptoms, and Resilience.” Educational Psychology 39 (9): 1136–1155. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2019.1577952.

- Capone, V., and G. Petrillo. 2018. “Mental Health in Teachers: Relationships with Job Satisfaction, Efficacy Beliefs, Burnout and Depression.” Current Psychology 39: 1–10. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9878-7.

- Carroll, A., L. Flynn, E. S. O’Connor, K. Forrest, J. Bower, S. Fynes-Clinton, A. York, and M. Ziaei. 2020. “In Their Words: Listening to Teachers’ Perceptions about Stress in the Workplace and How to Address It.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education: 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2020.1789914.

- Cenkseven-Önder, F., and M. Sari. 2009. “The Quality of School Life and Burnout as Predictors of Subjective Well-being among Teachers.” Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice 9 (3): 1223–1235.

- Clarà, M. 2017. “Teacher Resilience and Meaning Transformation: How Teachers Reappraise Situations of Adversity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 63: 82–91. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.12.010.

- Collie, R. J., J. D. Shapka, N. E. Perry, and A. J. Martin. 2015. “Teacher Well-being: Exploring Its Components and a Practice-oriented Scale.” Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment 33 (8): 744–756. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282915587990.

- Cook, C. R., F. G. Miller, A. Fiat, T. L. Renshaw, M. Frye, G. Joseph, and P. Decano. 2017. “Promoting Secondary Teacher’s Well-being and Intentions to Implement Evidence-based Practices: Randomized Evaluation of the Achiever Resilience Curriculum.” Psychology in the Schools 54 (1): 13–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21980.

- Critchley, H., and S. Gibbs. 2012. “The Effects of Positive Psychology on the Efficacy Beliefs of School Staff.” Educational and Child Psychology 29 (4): 64–76.

- Czerwinski, N., H. Egan, A. Cook, and M. Mantzios. 2020. “Teachers and Mindful Colouring to Tackle Burnout and Increase Mindfulness, Resiliency and Wellbeing.” Contemporary School Psychology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s40688-020-00279-9

- Day, C. 2019. “Quality Retention and Resilience in the Middle and Later Years of Teaching.” In Attracting and Keeping the Best Teachers: Issues and Opportunities, edited by A. Sullivan, B. Johnson, and M. Simons, 193–210. Singapore: Springer.

- Day, C., and Q. Gu. 2010. The New Lives of Teachers. London: Routledge.

- Day, C., and Q. Gu. 2014. Resilient Teachers, Resilient Schools: Building and Sustaining Quality in Testing Times. London: Routledge.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2001. “On Happiness and Human Potentials: A Review of Research on Hedonic and Eudaimonic Well-being.” Annual Review of Psychology 52 (1): 141–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2008. “Hedonia, Eudaimonia, and Well-being: An Introduction.” Journal of Happiness Studies 9 (1): 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9018-1.

- Diener, E. 1984. “Subjective Well-being.” Psychological Bulletin 95 (3): 542–575. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542.

- Dolan, P., and R. Metcalfe. 2012. “Measuring Subjective Wellbeing: Recommendations on Measures for Use by National Governments.” Journal of Social Policy 41 (2): 409–427. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0047279411000833.

- Doney, P. A. 2012. “Fostering Resilience: A Necessary Skill for Teacher Retention.” Journal of Science Teacher Education 24 (1): 645–664. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10972-012-9324-x.

- Duckworth, A. L., P. D. Quinn, and M. E. P. Seligman. 2009. “Positive Predictors of Teacher Effectiveness.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 4 (6): 540–547. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760903157232.

- Ebersöhn, L. 2012. “Adding ‘Flock’ to ‘Fight and Flight’: A Honeycomb of Resilience Where Supply of Relationships Meets Demand for Support.” Journal of Psychology in Africa 27 (1): 29–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2012.10874518.

- Ebersöhn, L. 2014. “Teacher Resilience: Theorizing Resilience and Poverty.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 20 (5): 568–594. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937960.

- Eldeleklioglu, J., and M. Yildiz. 2020. “Expressing Emotions, Resilience and Subjective Well-Being: An Investigation with Structural Equation Modeling.” International Education Studies 13 (6): 48–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v13n6p48

- Fernandes, L., F. Peixoto, M. J. Gouveia, J. C. Silva, and M. Wosnitza. 2019. “Fostering Teachers’ Resilience and Well-being through Professional Learning: Effects from a Training Programme.” The Australian Educational Researcher 46 (4): 681–698. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-019-00344-0.

- Fletcher, D., and M. Sarkar. 2013. “Psychological Resilience: A Review and Critique of Definitions, Concepts, and Theory.” European Psychologist 18 (1): 12–23. doi:https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000124.

- Gibbs, S., and A. Miller. 2014. “Teachers’ Resilience and Well-being: A Role for Educational Psychology.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 20 (5): 609–621. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2013.844408.

- Gray, C., G. Wilcox, and D. Nordstokke. 2017. “Teacher Mental Health, School Climate, Inclusive Education and Student Learning: A Review.” Canadian Psychology/Psychologie Canadienne 58 (3): 203–210. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/cap00001117.

- Greenfield, B. 2015. “How Can Teacher Resilience Be Protected and Promoted.” Educational and Child Psychology 32 (4): 52–68.

- Grenville-Cleave, B., and I. Boniwell. 2012. “Surviving or Thriving? Do Teachers Have Lower Perceived Control and Well-being than Other Professions?” Management in Education 26 (1): 3–5. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0892020611429252.

- Griffiths, A. 2014. “Promoting Resilience in Schools: A View from Occupational Health Psychology.” Teachers and Teaching: 1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937954.

- Gross, J. J. 2002. “Emotion-regulation: Affective, Cognitive, and Social Consequences.” Psychophysiology 39 (3): 281–291. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/S0048577201393198.

- Gu, Q. 2014. “The Role of Relational Resilience in Teachers’ Career-long Commitment and Effectiveness.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 20 (5): 502–529. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937961.

- Gu, Q., and C. Day. 2013. “Challenges to Teacher Resilience: Conditions Count.” British Educational Research Journal 39 (1): 22–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2011.623152.

- Gu, Q., and Q. Li. 2013. “Sustaining Resilience in Times of Change: Stories from Chinese Teachers.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 41 (3): 288–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2013.809056.

- Hagenauer, G., T. Hascher, and S. E. Volet. 2015. “Teacher Emotions in the Classroom: Associations with Students’Eengagement, Classroom Discipline and the Interpersonal Teacher-Student Relationship.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 30: 385–403. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-015-0250-0

- Harris, A. R., P. A. Jennings, D. A. Katz, R. M. Abenavoli, and M. T. Greenberg. 2015. “Promoting Stress Management and Wellbeing in Educators: Feasibility and Efficacy of a School-Based Yoga and Mindfulness Intervention.” Mindfulness 7: 143–154. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12671-015-0451-2

- Hwang, Y.-S., B.Bartlett, M. Greben, and K. Hand. 2017. “A Systematic Review of Mindfulness Interventions for In-Service Teachers: A Tool to Enhance Teacher Wellbeing and Performance.” Teaching and Teacher Education 64: 26–42, doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.01.015.

- Hascher, T. 2010. “Wellbeing.” In International Encyclopaedia of Education, edited by P. Peterson, E. Baker, and B. McGaw, 732–738. Oxford: Elsevier.

- Hascher, T., and J. Waber. “Teacher Well-being: A Systematic Review of the Research Literature from the Year 2000 to 2019.” Manuscript Submitted for Publication.

- Idris, I., A. Z. Khairani, and H. Shamsuddin. 2019. “The Influence of Resilience on Psychological Well-Being of Malaysian University Undergraduates.” International Journal of Higher Education 8 (4): 153–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v8n4p153.

- Jennings, P. A., J. L. Frank, K. E. Snowberg, M. A. Coccia, and M. T. Greenberg. 2013. “Improving Classroom Learning Environments by Cultivating Awareness and Resilience in Education (CARE): Results of a Randomized Controlled Trial.” School Psychology Quarterly 28 (4): 374–390. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/spq0000035.

- Johnson, B., and B. Down. 2013. “Critically Re-conceptualising Early Career Teacher Resilience.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 34 (5): 703–715. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2013.728365.

- Johnson, B., B. Down, R. Le Cornu, J. Peters, A. Sullivan, J. Pearce, and J. Hunter. 2014. “Promoting Early Career Teacher Resilience: A Framework for Understanding and Acting.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 20 (5): 530–546. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937957.

- Kitching, K., M. Morgan, and M. Leary. 2009. “It’s the Little Things: Exploring the Importance of Commonplace Events for Early-career Teachers’ Motivation.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 15 (1): 43–58. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600802661311.

- Klusmann, U., M. Kunter, U. Trautwein, O. Lüdtke, and J. Baumert. 2008. “Teachers’ Occupational Well-being and Quality of Instruction: The Important Role of Self-regulatory Patterns.” Journal of Educational Psychology 100 (3): 702–715. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.100.3.702.

- Kangas-Dick,K., andE.O.Shaughnessy. 2020. “Interventions that Promote Resilience among Teachers: A Systematic Review of the Literature”. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology 8 (2): 131–146. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2020.1734125.

- Larson, M., C. R. Cook, A. Fiat, and A. R. Lyon. 2018. “Stressed Teachers Don’t Make Good Implementers: Examining the Interplay between Stress Reduction and Intervention Fidelity.” School Mental Health 10 (1): 61–76. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s12310-018-9250-y.

- Lauermann, F., and J. König. 2016. “Teachers’ Professional Competence and Wellbeing: Understanding the Links between General Pedagogical Knowledge, Self-efficacy and Burnout.” Learning and Instruction 45: 9–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.06.006.

- Li, Q., Q. Gu, and W. He. 2019. “Resilience of Chinese Teachers: Why Perceived Work Conditions and Relational Trust Matter.” Measurement: Interdisciplinary Research and Perspectives 17 (3): 143–159. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15366367.2019.1588593.

- Lazarus, R. S. 1991. “Progress on a Cognitive-motivational-relational Theory of Emotion.” American Psychologist 46 (8): 819–834. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.46.8.819.

- Lazarus, R. S. 1999. Stress and Emotion: A New Synthesis. New York: Springer.

- Lazarus, R. S., and S. Folkman. 1984. Stress, Appraisal, and Coping. Heidelberg: Springer.

- Leroux, M., and M. Théorêt. 2014. “Intriguing Empirical Relations between Teachers’ Resilience and Reflection on Practice.” Reflective Practice: International and Multidisciplinary Perspectives 15 (3): 289–303. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/14623943.2014.900009.

- Lomas, T., J. C. Medina, I. Ivtzan, S. Rupprecht, and F. J. iroa-Orosa. 2017. “The Impact of Mindfulness on the Wellbeing and Performance of Educators: A Systematic Review of the Empirical Literature.” Teaching and Teacher Education 61: 132–141. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.10.008.

- Lester, L., C. Cefai, V. Cavioni, A. Barnes, and D. Cross. 2020. “A Whole-school Approach to Promoting Staff Wellbeing.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 45 (2): 1–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2020v45n2.1.

- Logan, H., T. Cumming, and S. Wong. 2020. “Sustaining the Work-Related Wellbeing of Early Childhood Educators: Perspectives from Key Stakeholders in Early Childhood Organisations.” International Journal of Early Childhood 52 (1): 95–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-020-00264-6.

- Mahfouz, J. 2018. “Mindfulness Training for School Administrators: Effects on Well-being and Leadership.” Journal of Educational Administration 56 (6): 602–619.

- Mansfield, C. F. 2021. Cultivating Teacher Resilience: International Approaches, Applications and Impact. Singapore: Springer.

- Mansfield, C. F., S. Beltman, and A. Price. 2014. “‘I’m Coming Back Again!’: The Resilience Process of Early Career Teachers.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 20 (5): 547–567. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937958.

- Mansfield, C. F., S. Beltman, T. Broadley, and N. Weatherby-Fell. 2016. “Building Resilience in Teacher Education: An Evidenced Informed Framework.” Teaching and Teacher Education 54: 77–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2015.11.016.

- Margolis, J., A. Hodge and A. Alexandrou. 2014. “The Teacher Educator’s Role in Promoting Institutional versus Individual Teacher Well-Being.” Journal of Education for Teaching 40 (4): 391–408. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/02607476.2014.929382.

- Masten, A. S. 2014. Ordinary Magic: Resilience in Development. New York: Guilford Press.

- McCallum, F., D. Price, A. Graham, and A. Morrison. 2017. Teacher Wellbeing: A Review of the Literature. Sydney: Association of Independent Schools of NSW.

- McGeown, S. P., H. St Clair-Thompson, and P. Clough. 2015. “The Study of Non-cognitive Attributes in Education: Proposing the Mental Toughness Framework.” Educational Review 1–18. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1008408.

- Mintrop, R., and J. Charles. 2016. “The Formation of Teacher Work Teams under Adverse Conditions: Towards a More Realistic Scenario for Schools in Distress.” Journal of Educational Change 18 (1): 49–75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-016-9293-5.

- Moè, A. 2016. “Harmonious Passion and Its Relationship with Teacher Well-being.” Teaching and Teacher Education 59: 431–437. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2016.07.017.

- McKay, L., and G. Barton. 2018. “Exploring how Arts-Based Reflection Can Support Teachers’ Resilience and Well-Being.” Teaching and Teacher Education 75: 356–365. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2018.07.012.

- Noble, T., and H. McGrath. 2015. “PROSPER: A New Framework for Positive Education.” Psychology of Well-Being 5 (1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13612-015-0030-2.

- Owen, S. 2016. “Professional Learning Communities: Building Skills, Reinvigorating the Passion, and Nurturing Teacher Wellbeing and “Flourishing” within Significantly Innovative Schooling Contexts.” Educational Review 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1119101.

- Papatraianou, L. H., and R. Le Cornu. 2014. “Problematising the Role of Personal and Professional Relationships in Early Career Teacher Resilience.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 39 (1): 100–116. doi:https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n1.7.

- Pretsch, J., B. Flunger, and M. Schmitt. 2012. “Resilience Predicts Well-being in Teachers, but Not in Non-teaching Employees.” Social Psychology of Education 15 (3): 321–336. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11218-012-9180-8.

- Price, D., and F. McCallum. 2014. “Ecological Influences on Teachers’ Well-being and “Fitness”.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2014.932329.

- Prinzing, M. N., J. Zhou, T. N. West, K. D. Le Nguyen, J. L. Wells, and B. L. Fredrickson. 2020. “Positive Psychology Is Value-laden – It’s Time to Embrace It.” The Journal of Positive Psychology 1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1716049.

- Rahm, T., and E. Heise. 2019. “Teaching Happiness to Teachers – Development and Evaluation of a Training in Subjective Well-being.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 2703. doi:https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02703.

- Richards, K. A., M. A. Hemphill, and T. J. Templin. 2018. “Personal and Contextual Factors Related to Teachers’ Experience with Stress and Burnout.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 24 (7): 768–787. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2018.1476337.

- Roffey, S. 2012. “Pupil Wellbeing – Teacher Wellbeing: Two Sides of the Same Coin?” Educational and Child Psychology 29 (4): 8–17.

- Rogoff, B. 2003. The Cultural Nature of Human Development. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Ryan, S. V., N. P. von der Embse, L. L. Pendergast, E. Saeki, N. Segool, and S. Schwing. 2017. “Leaving the Teaching Profession: The Role of Teacher Stress and Educational Accountability Policies on Turnover Intent.” Teaching and Teacher Education 66: 1–11. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2017.03.016.

- Sullivan, A., and B. Johnson. 2012. “Questionable Practices? Relying on Individual Teacher Resilience in Remote Schools”. Australian and International Journal of Rural Education 22: (3)101–116.

- Schelvis, R. M. C., G. I. J. M. Zwetsloot, E. H. Bos, and N. M. Wiezer. 2014. “Exploring Teacher and School Resilience as a New Perspective to Solve Persistent Problems in the Educational Sector.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 20 (5): 622–637. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2014.937962.

- Schleicher, A. 2018. “Valuing Our Teachers and Raising Their Status: How Communities Can Help. Paris: OECD Publishing.” doi:https://doi.org/10.1787/9789264292697-en. Accessed, September 14, 2021.

- Simmons, M., M. McDermott, J. Lock, R. Crowder, E. Hickey, N. DeSilva, R. Leong, and K. Wilson. 2019. “When Educators Come Together to Speak about Well-being: An Invitation to Talk.” Canadian Journal of Education/Revue Canadienne De L’éducation 42 (3): 850–872.

- Soini, T., K. Pyhältö, and J. Pietarinen. 2010. “Pedagogical Well-being: Reflecting Learning and Well-being in Teachers’ Work.” Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice 16 (6): 735–751. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2010.517690.

- Song, H., Q. Gu, and Z. Zhang. 2020. “An Exploratory Study of Teachers’ Subjective Wellbeing: Understanding the Links between Teachers’ Income Satisfaction, Altruism, Self-efficacy and Work Satisfaction.” Teachers and Teaching 26 (1): 3–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13540602.2020.1719059.

- Spilt, J. L., H. M. Y. Koomen, and J. T. Thijs. 2011. “Teacher Wellbeing: The Importance of Teacher-student Relationships.” Educational Psychology Review 23 (4): 457–477. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-011-9170-y.

- Sumsion, J. 2004. “Early Childhood Teachers’ Constructions of Their Resilience and Thriving: A Continuing Investigation.” International Journal of Early Years Education 12 (3): 275–290. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0966976042000268735.

- Sumsion, J. 2007. “Sustaining the Employment of Early Childhood Teachers in Long Day Care: A Case for Robust Hope, Critical Imagination and Critical Action.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 35 (3): 311–327. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13598660701447247.

- Taylor, J. L. 2013. “The Power of Resilience: A Theoretical Model to Empower, Encourage and Retain Teachers.” The Qualitative Report 18: 1–25.

- Tweed, R. G., E. Y. Mah, and L. G. Conway III. 2020. “Bringing Coherence to Positive Psychology: Faith in Humanity.” The Journal of Positive Psychology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1725605.

- Ungar, M. 2012. “Social Ecologies and Their Contribution to Resilience.” In The Social Ecology of Resilience: A Handbook of Theory and Practice, edited by M. Ungar, 13–31. Luxemburg: Springer Science+Business Media.

- Velichkovsky, B. B. 2009. “Primary and Secondary Appraisals in Measuring Resilience to Stress.” Psychology in Russia: State of the Art 5 (1): 539–563. doi:https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2009.0027.

- Wabule, A. 2020. “Resilience and Care: How Teachers Deal with Situations of Adversity in the Teaching and Learning Environment.” The Independent Journal of Teaching and Learning 15 (1): 76–90.

- Wells, C. M., and B. A. Klocko. 2018. “Principal Well-being and Resilience: Mindfulness as a Means to that End.” NASSP Bulletin 102 (2): 161–173. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0192636518777813.

- Wood, A. M., and S. Josephs. 2010. “The Absence of Positive Psychological (Eudemonic) Well-being as A Risk Factor for Depression: A Ten Year Cohort Study.” Journal of Affective Disorders 122 (3): 213–217. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.032.

- Wood, L., G. M. Ntaote, and L. Theron. 2012. “Supporting Lesotho Teachers to Develop Resilience in the Face of the HIV and AIDS Pandemic.” Teaching and Teacher Education 28 (3): 428–439. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2011.11.009.

Appendix

Table A1. Overview of illustrative examples and categorisation of the reviewed papers (N = 46)