ABSTRACT

Over the past two decades, there has been increasing international concern over the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst children and young people. In the English context, particular concerns have been raised about the “state” of girls’ and young women’s psychological health. Figuring highly in both academic and media debate is the impact of school pressures and the performance demands placed on girls in relation to academic achievement. In this systematic review, we map the reported achievement-related factors affecting girls’ mental health emerging from the peer-reviewed qualitative literature. Five databases were searched for literature published from 1990–2021. Additional search strategies included forwards and backwards citation chasing and hand searching. Eleven texts met our inclusion criteria. The themes of fears for the future, parent/family-related pressures, competitive school cultures, and gendered expectations of girls’ academic achievement emerged from the located texts. It was when pressures were “imbalanced” and felt in the extreme that mental ill-health/anxiety was more likely to be experienced. We go on to introduce the theoretical model of the “mental health/achievement see-saw” and argue for its use as a conceptual tool to engage with deep-rooted complexities around the relationship between gender, mental health and academic achievement. We contend that the “see-saw” model has potential utility to academics, educational practitioners, and policy-makers, and might be usefully translated into practice in the form of biopsychosocial interpositions in schools that move beyond more surface-level attempts at mental health promotion and that seek to empower, de-pathologise and challenge entrenched structural inequalities.

Introduction

Over the past two decades, there has been growing international interest in mental health and increasing concern over the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst children and young people (Strong & Sesma-Vazquez, Citation2015). In the English context, a number of reports and studies have been published that indicate a rapid upswing in the number of young people experiencing “emotional disorders” (NHS Digital, Citation2017; Patalay & Fitzsimons, Citation2017). This situation must be set against a wider backdrop of an emerging populist and media discourse relating to a mental health “crisis” or “epidemic” that is said to be sweeping through young people (e.g. Burns, Citation2016; Marsh & Boateng, Citation2018; Yorke, Citation2016). Successive governments appear to have accepted this as a priority and have made moves to address the situation through public health and educational policy initiatives (Department for Education, Citation2018; Department of Health, Citation2015; Department of Health & Department for Education, Citation2017).

One particular policy outcome is that schools in England are increasingly viewed as sites for mental health and wellbeing provision, with a broad range of “evidence-based” interventions concerned with mental health promotion, prevention and support for wellbeing seen as located within the school remit (e.g. see Department for Education, Citation2018). These often take the form of short-term initiatives (e.g. workshops) or programmes of support, although there is an increasing trend towards longer-term whole-school approaches that target curriculum design, behaviour policy, and that provide more embedded opportunities to “develop” students’ and staff’s social and emotional skills and resilience (Humphrey et al., Citation2010; O’Reilly et al., Citation2018). Within current policy, it is framed as the responsibility of schools (i.e. teachers, school healthcare professionals) to identify students experiencing more extreme mental health difficulties who might then be referred on for specialist and intensified levels of support in clinical, day or inpatient settings.Footnote1

Particular concerns have also been raised in England about the “state” of girls’ and young women’s psychological health. In 2017, the Department of Health and Social Care funded a nation-wide survey on the mental health of children and young people and data revealed that 17–19 year old women were almost three times more likely to experience an emotional disorder than young men of the same age (22.4%/7.9%) – which was almost double the rate in girls aged 11–16 (NHS Digital, Citation2017). Data from the UK Millennium Cohort Study showed differences by ethnicity and socio-economic status, with girls from poorer homes and from mixed and White ethnic backgrounds the most likely, and Black African girls the least likely to report high depressive symptoms (Patalay & Fitzsimons, Citation2017). This resonates with research from other countries that indicates that girls are likely to display greater prevalence of mental health difficulties such as anxiety and depression (e.g. Beattie et al., Citation2019; Keyes et al., Citation2019). In October 2020, a second wave of NHS Digital data was published that showed the “gender gap” was still evident, with 27.2% of young women aged 17–22 years in comparison with 13.3% of young men identified as having a probable mental disorder. The impact of the Covid-19 pandemic was found to have exacerbated mental health pressures for all young people (NHS Digital, Citation2020).

This focus on girls must be juxtaposed against wider evidence which demonstrates that boys and young men also suffer from mental health difficulties, face a similar decline through their teenage years, and as a group display particularly high suicide rates (Pitman et al., Citation2012; Sher, Citation2020). There is uncertainty within the literature as to why young men might be more likely to commit suicide whilst young women are more likely to experience non-fatal mental health-related difficulties. Some researchers have drawn on Connell's (Citation1987, Citation1995) concept of hegemonic masculinity and have suggested that boys and young men seek to construct gender identities in line with dominant masculine norms of toughness, strength and emotional detachment, which can result in a lack of willingness to seek help from friends, family and healthcare professionals when they are experiencing mental distress (e.g. Coleman, Citation2015; King et al., Citation2020). However, critical gender scholars have identified and deconstructed the emergence of a gendered discourse of suicide that appears to fuel arguments of a “crisis” of masculinity, and that homogenises boys’ and young men’s gender identities and life experiences in an overly simplistic way (e.g. Jaworski, Citation2014; Mac An Ghaill & Haywood, Citation2012). Jordan and Chandler (Citation2019) further highlight how this discursive construction of suicide as a male problem can render girls’ and young women’s experiences of mental distress less visible or important.

The Department for Education (DfE) commissioned State of the Nation (Department for Education, Citation2019) report found that girls’ experiences of being bullied (both in person and online) was the “risk factor” (p. 10) most strongly associated with mental ill-health in England. Other international evidence suggests that high levels of emotional distress might be linked with: the pressures generated by social media use (Raudsepp & Kais, Citation2019; Ringrose et al., Citation2013); body image issues and dissatisfaction with appearance (Tolman et al., Citation2006); girl-related micro-aggression (Conway, Citation2005; Currie et al., Citation2007); and quality of home life (World Health Organization, Citation2019). Yet also figuring highly in both academic and media debate is the impact of school pressures and the performance demands placed on students in relation to achievement.

A growing body of scholarly literature suggests that academic pressures and the desire to succeed in school in combination with an increasingly “risky” world characterised by a precarious labour market can have an especially damaging effect on girls’ emotional states. For example, critical feminist researchers have highlighted how socially constructed gender norms (i.e. heteronormative femininity) can lie in tension with the current performance regime and “culture of perfection” embedded within schools. This culture demands that girls, in particular, meet ever higher standards of academic achievement, often in highly stressed teaching environments – a symptom of which can be undue anxiety and pressure (Pomerantz & Raby, Citation2011; Renold & Allan, Citation2006; Ringrose, Citation2012). Concerns have recently been raised that the Covid-19 pandemic has the potential to heighten such achievement-related stresses, and that students might feel under increased pressure to do well at school to make up for possible loss of learning and disruption to education (Coward, Citation2021; Mahapatra & Sharma, Citation2021).

Girls, academic achievement and “overpressure” debates: an historical lens

It should be noted that interest in the stress and pressure related to academic achievement, and the impact which this might have on young people’s mental health, is not new (Dyhouse, Citation1981). Historical texts and sources that have reflected on the developments in elementary education in 19th century Britain are replete with references to a phenomenon which became known as the “overpressure” of young people in Victorian education (Shuttleworth, Citation2012). This was a widespread and enduring concern often featuring in public debates instigated by leading medical educators of the time, to do with the dangerous levels of stress which were considered to exist in schools and were thought to lead to the “slow decline” of young people’s physical and mental health – and, in some instances, their suicide or death (Duffy, Citation1968).

These concerns were often raised in relation to heavy curriculums and the competitive examination systems that existed at the time, but also to the immense strain caused by the constant memorisation involved in rote learning. And while these debates played out in relation to the education of both boys and girls, particular concerns were raised about the differential impact which this strain might have on girls. The sociologist Herbert Spencer, for example, is reported to have commented on the dangers of high-pressure education for girls, sharing his concern about how it would “enfeeble women” and “render them unattractive to men” (Dyhouse, Citation2013, p. 54). In 1875 in the US, Dr Edward Clarke is also reported to have spoken out in a similar manner, referring to “over-educated” girls as “pallid” and “hysterical women” who were frequently sterile and whose brains had become “rotted” (Dyhouse, Citation2013, p. 55). Further, Dyhouse (Citation1981) notes how debates of over-strain during the late 1800s focused mainly on the middle-class girl.

Looking back these notions might seem rather absurd to us now – quite far removed from contemporary understandings of gender, mental health and education. But these 19th century debates do seem to resonate with some of the current discussions which have been held around the assumed fragility of girls in education today. And yet we are surprised by the comparative lack of attention which has been shown for these concerns in contemporary academic research. At present there exists a lack of review work bringing together insights as to the possible relationship between mental health difficulties and achievement pressures as experienced by schoolgirls, which this paper seeks to address.

Rationale

Whilst we recognise that the underlying cause for the increasing prevalence of girls’ and young women’s mental health difficulties is incredibly complex and likely to be the product of multiple intersecting factors, in this paper we are interested in exploring insights from the qualitative literature pertaining to the significance of academic achievement pressures. As Seers (Citation2015) suggests, qualitative systematic reviews can help us to “uncover new understandings, often helping illuminate ‘why’ and can help build theory” (p. 36). Such reviews are less interested in matters of effectiveness or “what works” in terms of interventions, but can elucidate how individuals experience particular social phenomena and the possible factors underpinning such experiences. It is our aim in this review to synthesise findings from empirical qualitative studies on girls’ achievement-related mental ill-health to generate new insights and conceptual understandings. The specific research questions framing this review are:

Are there any patterns in the peer-reviewed qualitative literature relating to girls’ achievement-related mental ill-health by date, country, sample, method or theoretical underpinnings?

What are the reported factors affecting girls’ achievement-related mental ill-health emerging from the qualitative literature, and how might they be interrelated?

Conceptualising “mental health”

An issue of central concern in this paper is what is meant by the term “mental health”. Mental health is a complex construct and different definitions have been offered by stakeholder groups including public health bodies, charities, voluntary organisations, medical and health care professionals, and academics. Often a link is made between the terms “mental health” and “wellbeing” in popular discourse and this conceptualisation appears to underpin the World Health Organization (Citation2013) definition, where mental health is equated with wellbeing:

… mental health … is conceptualized as a state of well-being in which the individual realizes his or her own abilities, can cope with the normal stresses of life, can work productively and fruitfully, and is able to make a contribution to his or her community. (p. 6)

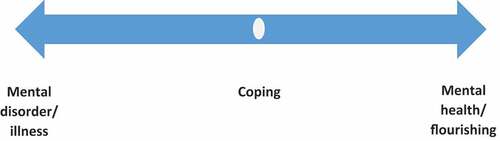

According to this definition, mental health is constructed positively in a way that moves beyond the assumption that mental health is simply the absence of illness or disease (Schönfeld et al., Citation2017). This definition also sees mental health as incorporating a number of dimensions such as one’s physical, emotional, psychological and social wellbeing. Often this has led to an understanding of mental health as lying on a continuum, with “mentally healthy” positioned at one end of the spectrum and “mentally unwell/ill” (as clinically diagnosed) at the other – see . Various states of coping and struggling might be seen as located at points along this spectrum (Keyes, Citation2007). High academic achievement might be seen as a possible outcome of positive health and wellbeing. Others, however, have conceptualised mental health as separate from wellbeing – the latter of which Antaramian et al. (Citation2010, p. 462) define as “the way in which and the reasons why individuals experience their lives positively”. According to this “dual factor” model, someone could be understood to have a mental health disorder but experience high wellbeing, or have good mental health but experience low wellbeing (Antaramian et al., Citation2010) – see . Here the two constructs are seen as distinct but related, facilitating a more nuanced understanding of mental health. Whilst both models might be understood as recognising that the absence of mental illness does not necessarily equate with good mental health, some have been sceptical about the growing government/institutional trend towards a positive discourse of mental health and have questioned whether the term might actually refer to “mental illness” in an attempt to disguise stigma (Kendall-Taylor & Mikulak, Citation2009; Strong & Sesma-Vazquez, Citation2015).

Within academic debate – and particularly within the field of educational research – there is contestation as to how mental health might be conceptualised and investigated in relation to young people and schooling. Those working from a clinical psychology, biological or public health perspective often draw upon a medical model framework and use terms such as “mental illness”, “psychological illness”, and “internalising symptoms”, as embedded in scientific discourse relating to diagnosis and treatment (Kendall-Taylor & Mikulak, Citation2009). Yet critical educational sociologists have often sought to shy away from using medicalised terms, perhaps in part due to disciplinary norms and conventions, but also due to concerns over constructing illness as inherent within the person rather than in some way socially conditioned or produced (Thomas, Citation2004; Youdell et al., Citation2018). Instead, more generic terms tend to be used that relate to individuals’ emotional or affective states such as “anxiety”, “stress”, “worry” and “pressure”. These terms are often deployed in a less diagnostic sense to how psychologists and medical researchers might use them, possibly in an attempt to avoid pathologising those experiencing difficulties. In this review, we adopt a holistic stance that acknowledges the complex interaction between the “individual” (biological/psychological) and the “social” (cultural/environmental) in producing mental ill-health – and the varied discourses which frame the production of mental health as a phenomenon.

Conceptualising gender

Some context is also needed in order to make clear the theoretical legacies pertaining to gender that scaffold this review, and which inform the analysis of the texts included in the review. It should be noted that the following discussion is rooted largely in Anglophone scholarship and those operating in the global North, which might be regarded as a limitation. We also place the caveat that it is not possible to do proper justice to the complex debates about gender that have shaped thinking in the fields of gender and education research over the past half century, but we attempt instead to document some influential perspectives and approaches.

Traditional understandings of “sex” are rooted in assumptions of sex difference, with “males” and “females” seen as biologically different and as engaging in behaviours that are ascribed to their sex (e.g. girls as gentle and caring, and boys as boisterous and competitive). However, during the 1960/70s, second wave feminist scholarship made a valuable contribution by questioning the notion that one’s biology wholly drives one’s behaviour. It was noted, for example, that not all individuals have bodies that are identifiable as male or female (e.g. Kessler & McKenna., Citation1978). Thus, the concept of “gender” was introduced as a theoretical construct to emphasise how gender differences are socially produced (e.g. Oakley, Citation1972; Unger, Citation1979) – and with gender inequalities in society understood as stemming from asymmetrical male/female power relations. Sex role and socialisation theories were subsequently established which emphasised the power of outside influences such as parents, family, peers and the media in perpetuating gender messages that create and sustain difference (e.g. Maccoby & Jacklin, Citation1974).

Whilst this understanding of gender as (at least in part) socially constructed retains widespread appeal in both academia and the wider public imaginary, more complex and sophisticated theorisations of gender identity and power relations have emerged in the intervening years (Francis & Paechter, Citation2015). Scholars have been particularly keen to understand how gender inequalities are perpetuated and maintained, but also possibilities for agency, disconformity and resistance. Work on intersectionality has been particularly influential and has drawn attention to how other identity facets such as ethnicity, social class, disability and sexuality might traverse gender lines and shape individuals’ unique lived experiences (Hill-Collins, Citation1991; Hooks, Citation1982). This body of scholarship highlights how women can exert power over other women (as well as over men), undermining notions of patriarchy.

Connell’s (Citation1995) work on multiple “masculinities” and “femininities” has also played a significant role in refining thinking around gender and power relations, emphasising the plurality of gender identities and how certain masculinities can subjugate others (i.e. hegemonic masculinity). Connell’s ideas retain much purchase in the gender and education literature despite (self-acknowledged) criticisms that misapplication of the theory can result in simplistic typologies of masculinity and femininity that further reinforce gender dualisms (Connell & Messerschmidt, Citation2005). Other theorisations have also gained significant traction, including work informed by poststructuralism and the ideas of Judith Butler (Citation1990) and Michel Foucault (Citation1977, Citation1980). Often education researchers working within this tradition have focused on mapping students’ and teachers’ lived performances of gender subjectivity and deconstructing dominant gender discourses in the context of schooling (e.g. Francis, Citation2008).

Alongside this work has emerged a body of scholarship that has sought greater focus on the realm of the internal (i.e. thoughts, feelings, emotions, affect), and to theorise how the individual/psychic and the social/society might work together to constitute the gendered person. Psychosocial approaches as grounded in insights from psychoanalytic theory and sociology emerged around the 1980s (e.g. see Rosalind Coward’s (Citation1984) work on female desire and femininity), and entered more distinctly into education research in the late 1990s-early 2000s (Walkerdine, Citation2008). Often education researchers adopting a psychosocial approach have sought to examine how young people’s feelings such as anxiety, pressure, angst, pain, desire and loss are bound up with the production of gender identities, which are in turn fashioned within particular socio-historical moments (e.g. Bibby, Citation2011; Frosh et al., Citation2002; Walkerdine et al., Citation2001).

Yet, some scholars have seen limitations in poststructural and psychosocial approaches, which have been charged with placing an over-emphasis on language and discourse and neglecting the significance of the “fleshy” body in determining who one is, what one can become, and how one is viewed by others (e.g. Ringrose, Citation2011). What has been described as the “affective turn” (Clough & Halley, Citation2007) has more recently refocused attention on issues of embodiment and the material. An emergent strand of research has utilised theoretical tools from cultural theorists such as Deleuze and Guattari, and feminist science scholars such as Karan Barad to map the complex and multifaceted embodied, relational, spatial and affective assemblages that are thought to organise and constitute gender identity (e.g. Günther-Hanssen et al., Citation2020; Taylor, Citation2013). Here, educational inequalities and exclusions are broadly understood as produced through the multiplex intra-actions of the human and non-human. Youdell and Lindley's (Citation2019) recent work on biosocial education represents another important attempt to greater acknowledge the material and internal bodily milieu, through an interdisciplinary lens that incorporates insights from biology (e.g. epigenetics, metabolomics, neuroscience) and sociology.

In this paper, we understand gender as socially constructed yet recognise the significance of the psychological and material in constituting the gendered person.

Methods

Search strategy and search terms: We conducted an initial search of the topic area to gain insight into terms commonly used by researchers influenced by different theoretical and disciplinary traditions (e.g. psychology, psychiatry, sociology, medicine). We then reflected on possibly relevant search terms and checked synonyms in a thesaurus. From this we devised a comprehensive search strategy that involved cross-searching four different sets of search terms within title and abstract fields:

‘Girl’Footnote2 terms: girl*, femininit*, “young wom*n*”, female*

School terms: school*, education*

Mental health terms: “mental health”, “mental illness”, “mental distress”, “mental disorder*”, “psychological disorder*”, “psychological illness*”, “psychological health”, “psychological distress”, anxiety, anxious, stress*, depressed, depression, pressure*, worry, worried, panic*, wellbeing, “internali*ing behavio*r*”, “internali*ing symptom*”, “internali*ing disorder*”, “internali*ing problem*”

Achievement terms: achievement*, attainment*, attaining, achieving, “academic* perform*”, “academic* success*”, “school performance”

Database searching: In April 2020, five electronic databases were searched using the search terms: British Education Index, Education Research Complete, ERIC, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, and Australian Education Index. We selected these databases as we wanted to capture literature with a specific focus on education and schooling. The search was re-run in March 2021 in light of Covid-19, but no further texts were located. Results were limited to peer-reviewed texts.

Inclusion criteria: To be included in this review, texts had to meet the following criteria:

Be published in the English language.

Be published from 1990–2021.

Originate from any country.

Employ qualitative methods (either on their own or as part of a mixed methods study.)

The majority of students in the sample had to be aged between 5 − 18 years (i.e. primary, secondary and/or further education phases in England), or be educational professionals or parents/guardians discussing this age group.

There had to be a focus within the text and/or findings that related substantially to mental health, anxiety or a related construct (i.e. more than just a few sentences). This did not have to be at a clinically diagnosable level.

If anxiety was the focus, it had to relate to students’ general state of psychological health rather than a specific type of anxiety (e.g. test anxiety, maths anxiety).

There had to be a focus within the text and/or findings that related substantially to “girls”.

Retrospective studies were excluded i.e. adults reflecting on their school experience.

Selection process: The titles and abstracts of records retrieved through searching were screened for relevance by LS, who classified each paper as potentially include or exclude according to the above criteria. This was done following a pilot stage where GK and LS screened 10% of the records independently to agree on screening decisions. Full text copies of potentially relevant articles were then obtained. The retrieved articles were again assessed for inclusion by LS, following piloting of 20% of the records (LS and GK). The number of studies identified, included and excluded at each stage have been reported using a flow diagram together with reasons for exclusion at the full-text stage ().

Additional search strategies: The titles of included full texts were input into Google Scholar and the titles/abstracts of citing literature were scanned for relevance (i.e. forwards citation chasing). The reference lists of all included full texts were also checked (i.e. backwards citation chasing). In addition, hand searching of key journals was conducted e.g. Gender and Education, Disability & Society, British Journal of Special Education.

Data management: EndNote X8 software was used to manage references throughout the review. The results of searches were exported into EndNote and duplicates were removed.

Considering quality: In this review, we assessed the quality of the texts based primarily on those that appeared most relevant to our aim rather than on methodological standards, given the difficulties associated with judging the quality of qualitative studies and to avoid unnecessarily excluding useful texts (Toye et al., Citation2013). We used the five-prong criteria outlined by Dixon-Woods et al. (Citation2006) which includes questions such as whether the aims and objectives of the study are clearly stated, and whether the research design is clearly specified. Quality assessment was performed by LS and GK, and we jointly agreed that all texts met the criteria. However, we take a reflexive stance around quality in this paper and make clear throughout where our interpretations and claims might need to be mediated based on the data available.

Data charting: A data charting form was developed specifically for this review, guided by the full-text screening stage. The data charting form was pilot tested on several texts included in the review and refined by LS and GK. Data charted included: first author, date, country, sample, research design, methods, conceptualisation of mental health and gender, and findings.

Analysis: We used thematic synthesis (Thomas & Harden, Citation2008) to combine the findings from the included studies and identify key themes emerging from the texts. All texts were read multiple times to gain familiarity with the data. We then imported the texts into NVivo 12 software and LS coded each text line-by-line, via a combination of descriptive and in vivo coding (Saldaña, Citation2013). Initial analytical thoughts and memos were recorded regarding similarities and differences across the texts. LS and GK then worked together with the codes and collapsed them into a smaller number of categories, and emergent descriptive themes were identified. These descriptive themes were subsequently reviewed and refined through discussion between LS and GK, generating analytical themes that represented new interpretive constructs and explanations about the data.

Findings

We located ten peer-reviewed articles that met our inclusion criteria and one book – Walkerdine et al.’s Growing Up Girl (Walkerdine et al., Citation2001) – which was located through backwards citation chasing. This text was cited by four of the included studies and is often seen as a seminal work in the field of sociology of education and girlhood studies. We therefore felt it would be valuable to include this text. See for an overview of findings.

Table 1. Overview of studies with student participants

Table 2. Overview of studies with staff participants only

Publication date and country

The eleven studies located in this review were published from 1999–2020, and were conducted in five different countries: USA (n = 3), Sweden (n = 3), UK (n = 3), Finland (n = 1) and Norway (n = 1). Only one study was published in the 1990s, and seven were published in the last decade (i.e. 2010–2020).

Methods

All eleven studies employed some form of interview/discussion method, but other qualitative methods included a photograph method (Lenz & Palmer, Citation2013) and weekly focus groups (Ekert & Drago-Severson, Citation1999).

Samples

Participants in the studies ranged in age from 10–21 years, and the number of girls in the samples ranged from 2 to 115. However, as can be seen in , sample sizes were generally small, with six out of the nine studies (with a student sample) having fewer than 30 participants. One author left the gender composition of their total sample (n = 53) unstated (Eriksen, Citation2021). Five studies stated explicitly that students were drawn from a mix of ethnicities. A further five studies identified the broad social class composition of their sample – two of which were conducted with a predominantly middle-class sample, and three with a mixture of social classes. A number of studies left these details unspecified. Six studies collected data from girls in combination with other groups; namely boys, teachers and parents (e.g. Eriksen, Citation2021; Spencer et al., Citation2018). Two studies were conducted with school staff only, e.g. teachers, student welfare team members (Odenbring, Citation2019; Perander et al., Citation2020) – see .

School contexts

Authors stated that the studies were set in a variety of educational contexts which included: single-sex and mixed gender schools; high performing and average performing schools; and independent and comprehensive schools. The context of the studies should be kept in mind as the findings below are presented, with the studies seen as illuminating their particular contexts rather than describing generalisable patterns.

How mental health and gender are conceptualised

also show how the authors appeared to theorise mental health and gender, based on our interpretation of the texts. Most authors (n = 8) discussed mental health and/or a related construct (e.g. anxiety, stress, fear) in a way that signalled that they understood mental ill/health to be the product of both individual and social factors. Lenz and Palmer (Citation2013) were the only authors to take a wholly social approach and omit consideration of the biological and/or psychological. This was due to the authors’ increasing unease about the prevalence of media reports and medical studies in Sweden that locate mental illness within girls themselves – which formed the key thesis of the paper, as grounded in a feminist agential realist diffractive analysis. Authors were less likely to provide explicit details of how they conceptualised gender (in five papers this was unstated), but the remaining authors appeared to see gender as in some way socially constructed (n = 6). This is perhaps unsurprising given the long-running contention and feminist debate around the relationship between sex and gender and the desire to avoid gender essentialism. Some did, however, combine social understandings of gender with a recognition of the potential influence of psychological (Walkerdine et al., Citation2001) or biological factors (Roeser et al., Citation2008).

Reported achievement-related factors affecting girls’ mental health

We will now go on to discuss key themes that emerged from the data and their interrelationships, grounded in supporting evidence from the studies.

Fears for the future

Emerging most strongly from the eleven studies was a sense that much anxiety around achievement was grounded in fears for the future – and more specifically, the need to have a “good” future and be “happy” (n = 10 texts). We identified two specific future-oriented triggers for anxiety: 1) the need to gain entry into a good college/university and; 2) to obtain a good job. Girls’ desire to attain these two goals emerged particularly clearly in Spencer et al.’s (Citation2018) study, which was conducted with 115 girls in two high-performing independent single-sex schools in America. Spencer et al. found that the girls saw a direct link between these goals; they wanted to gain “straight As” so that they might gain entry into “the most elite universities”, which in turn was seen to lead to a “good career” that is “high status” and “pays well” (p. 16).

In accordance with the above, it was found that success was often constructed in a very narrow way by the girls in the studies, based on material success, accumulation of wealth, social prestige and status (e.g. Ekert & Drago-Severson, Citation1999; Eriksen, Citation2021). There was general consensus amongst the girls that if they did not achieve these goals, they would have “failed” and would be unhappy and unfulfilled. Only occasionally did researchers discuss girls who were driven by alternative definitions of future success such as “helping others” or “giving back to the community” (e.g. Spencer et al., Citation2018, p. 22) – and it was made clear by the authors that these girls were outliers.

Parent/family-related pressures

Another theme to emerge was parent/family-related pressures, which was identified by several authors as in part fuelling girls’ fears about their future success (n = 7). Yet this is not to say that there was a simple unidirectional relationship where parents/families placed unrealistically high pressures onto their child to perform well at school. Whilst some authors did identify evidence of this at points in both parents’ and girls’ narratives (e.g. Eriksen, Citation2021; Låftman et al., Citation2013; Spencer et al., Citation2018), authors generally acknowledged that parents/families were reflexively aware and that, whilst they wanted the “best” for their child, it would ultimately be unhelpful to place excessive pressures onto them. For example, the parents of the middle-class girls in Lucey and Reay’s (Citation2002) UK-based study often expressed guilt at encouraging their children to take entry examinations for selective secondary schools given the high levels of stress involved and risk of their child not passing, which they knew could cause psychological distress. Lucey and Reay discuss how these feelings of parental anxiety are produced in and through neo-liberal discourses of “performativity”, “choice” and “competition” that came to dominate educational policy in 1990s Britain, which can mobilise fears of downward social mobility amongst the middle-classes.

Social class emerged as a key intersectional influence, strongly contouring how and why fears were experienced by girls to differing degrees. There was evidence in the studies that girls from middle/upper-class backgrounds often felt pressures to “live up to” their parents’ standards and to emulate their successful careers and lifestyles (e.g. Eriksen, Citation2021; Spencer et al., Citation2018). In contrast, Jackson (Citation2010) found that the lower/middle-class students in her UK study felt that their parents wanted them to do better than themselves so that they might have brighter futures; “[My parents] want me to do well. They want me to get where I’m going ‘cause they said that they wish they’d done well at school and done better … ” Jane, working-class student (pp. 45–6). Some studies further detailed how lower/middle-class girls felt under pressure to do better than unsuccessful siblings or match a sibling’s high performance (e.g. Jackson, Citation2010; Låftman et al., Citation2013).

There was also evidence of social class intersecting with ethnicity. For example, Ekert and Drago-Severson (Citation1999) conducted an ethnographic study with sixteen 14–18 year old girls attending a high-performing Catholic high-school in America. These students were from different ethnic minority backgrounds and were from families who were “struggling financially” (p. 187). The girls in this study appeared to feel a heavy sense of responsibility to do well at school to reward their parents for the sacrifices they had made – such as moving country to access a “good” education system. For instance, a Haitian-American student, Rochelle, in ninth grade stated

My family’s counting on me to do well. They want me to do the best that I can in school, keep up those grades. They want to see me go to college and become a paediatrician … (p. 187)

Competitive school cultures

The concept of competition and, more specifically, competitive school cultures also emerged strongly in the texts as contributing to girls’ anxiety and mental ill-health. Six studies documented how competition between students was embedded in school cultures, both created and reinforced through: 1) teacher expectations of student success and institutionalised “performance” regimes (e.g. Låftman et al., Citation2013) and; 2) girls’ often fierce desire to outdo their peers (e.g. Spencer et al., Citation2018).

Some researchers acknowledged the key role of schools as meso-level institutions; spaces where mediation between macro-scale influences (i.e. socio-political and economic forces, educational policy directives) and micro-scale interactions (i.e. girls’ everyday experiences) took place. For example, Walkerdine et al. (Citation2001) present the case of Naomi, a middle-class student who attended an elite UK primary and secondary school, and document her mental health struggles from age 10–21 years which manifested in symptoms such as extreme anxiety, long episodes of crying, chronic insomnia, obsessive behaviours and eating disorders. The authors discuss how the culture of the elite schools – in themselves driven by government-induced performance regimes and a culture of league tables and testing – created a highly pressurised academic environment that in effect “produced” Naomi’s mental ill-health. Naomi herself seemed to recognise this retrospectively:

I just think I always took [academics] a bit too seriously but I think that’s the sort of school it was really, that it was very pushy and academic and it was never enough, you never did enough, or it was never good enough. (p. 122)

As hinted in the above extract, social class factors as a strong intersectional influence with evidence from the studies suggesting that girls from middle or upper-class backgrounds and/or who attend elite schools are more likely to experience achievement-related anxiety due to the demanding cultures of such institutions.

Peer competition and the constant need to outdo fellow students also emerged as a related sub-theme. There was evidence across the studies of girls feeling high levels of pressure to match or exceed their peers’ level of achievement – although this was often identified by the girls as a hidden or unacknowledged sense of competitiveness (e.g. Låftman et al., Citation2013). This sense of competition could be particularly intense where participants attended an all-girls’ school (e.g. Spencer et al., Citation2018).

Gendered expectations of girls’ academic achievement

There was also evidence in the texts of how girls on the micro-level might be subject to particular expectations regarding study behaviours and levels of achievement that are different to those of boys (n = 5). Odenbring (Citation2019), for example, conducted interviews with professionals working in student welfare teams in three secondary schools in Sweden. These individuals felt that girls were subject to particularly high expectations around both academic achievement and “successful” girlhood, e.g. “ … you have to perform well at school, you have to be a good friend, you have to be good at home, you have to be good looking, wear the right clothes, you have to have a cool boyfriend, well yes, and good grades … ” School Counsellor (p. 266). Odenbring utilises Skeggs’ (Citation2002) and Walkerdine et al.’s (Citation2001) concepts of the “respectable girl” and “supergirl” in order to theorise how these pressures are produced through late-modern, post-feminist discourses of girls’ freedom and empowerment that create girlhood ideals that can be impossibly hard to live up to.

In two studies, there was evidence of the impact of ethnicity and disability shaping the extent to which girls felt they could be recognised by others as a high achiever, and thus gain access to social status and prestige. For example, a 14-year-old eighth grader of mixed ethnic heritage in Roeser et al.’s (Citation2008) American study discussed her experience of racial discrimination:

So I mean it’s like no matter what I do to prove that I’m a good student, they won’t never accept it because of where I’ve come from and what they think I am because of my skin color. (p. 143)

And Walkerdine et al. (Citation2001) document the co-ed comprehensive secondary school experience of Kerry, a white British working-class girl, who found schoolwork very difficult and was described by her teachers as a “nice girl” who was “slow and of low ability” (p. 121). This led to Kerry experiencing chronically low self-worth and a suicide attempt at the age of 15 that resulted in psychiatric hospitalisation. It was only after Kerry left school at the age of 16 and was diagnosed as severely dyslexic that both she and her family understood why she had struggled at school – a diagnosis that Kerry’s school were unwilling to provide. Walkerdine et al. argue that Kerry’s normative “good girl” identity lay in tension with school staff’s expectations of a “typical” student with learning difficulties (presumably male), fuelling the school’s reluctance to provide Kerry with a diagnosis that might have facilitated the provision of appropriate support.

An “imbalance” in pressures experienced

A final theme emanating from the studies was that it was when pressures to achieve academically were felt in the extreme that anxiety and mental health difficulties could be experienced – ranging from relatively mild and self-manageable symptoms, to clinically diagnosable conditions (n = 6). Across the studies we noted the recurring concept of imbalance, which we felt was understood and discussed by the authors in three different ways: 1) an imbalance in terms of healthy lifestyle, i.e. time spent studying, eating well, getting enough sleep, socialising, participation in extra-curricular activities (e.g. Ekert & Drago-Severson, Citation1999; Låftman et al., Citation2013); 2) an imbalance in gender identity constitution i.e. the ideal successful “well-rounded” girl as achieving high grades, being popular, being beautiful, having extra-curricular interests, etc. (e.g. Odenbring, Citation2019; Walkerdine et al., Citation2001), and; 3) an imbalance in personal perspective about the importance of academic achievement (e.g. Roeser et al., Citation2008; Spencer et al., Citation2018). The first two points relate strongly to one’s social, cultural and physical environment (i.e. the external). The third point relates more closely to one’s individual biology, psychology, physiology and the realm of emotions (i.e. the internal) – although all three points are arguably closely interwoven. This idea of im/balance will be further taken up and discussed below.

Discussion

This review has sought to explore the possible achievement-related factors affecting girls’ mental health as documented in the published qualitative literature and consider their interrelationships. Seven of the eleven studies included in this review were published in the last decade, indicating increased interest in the topic more recently. This growth in interest must be set against a wider backdrop of heightened international awareness of the prevalence of mental health difficulties amongst young people, and an increasing emphasis placed in educational policy on schools as sites for mental health and wellbeing provision by governments globally (UNICEF, Citation2013; World Health Organization, Citation2017). The Covid-19 pandemic will no doubt focus greater research attention on the mental health of young people in the coming years (Newlove-Delgado et al., Citation2021).

Given that all eleven texts originated from OECD countries in North America and Northern Europe, it is questionable whether mental health issues – particularly amongst girls – are more prevalent in these societies, or whether more developed education systems and the nature of social, political and economic relations in these countries mean that greater attention can be paid to issues of child mental health. It might also be the case that in less economically developed countries, other educational issues might come to the foreground such as a gender gap in school enrolment rates and gender-based violence, which create different types of academic pressures. However, it should be highlighted that only texts written in English were included in this review, which might have “skewed” the findings towards English-speaking countries.

Generally the studies were of small scale with low sample sizes (n = <30). This is perhaps less surprising given that this is a qualitative review and that sample sizes in qualitative studies are usually smaller due to philosophical and practical considerations. Indeed, one point to note is that our database searches returned a high number of quantitative studies that involved researchers measuring girls’ and boys’ mental health “state” on a validated diagnostic tool (e.g. Me and My Feelings scale, Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory), and linking this with educational data on attainment (i.e. grade point average, self-reported grades, test score data), either at one time point or longitudinally (e.g. see Deighton et al., Citation2018; Moksnes et al., Citation2010). This might be expected given the dominant discourse of mental health/illness that is grounded in the realms of medicine and psychiatry (Strong & Sesma-Vazquez, Citation2015) – traditions historically favouring quantitative research approaches.

Evidence from these quantitative studies tended to indicate that girls were at greater risk of developing mental health difficulties than boys, and that mental health issues were likely in some way related to the pressures to obtain high grades at school (e.g. Fröjd et al., Citation2008; Giota & Gustafsson, Citation2017). However, when statistically significant findings were obtained, there was often uncertainty as to the direction of the relationship, i.e. whether mental health difficulties might result in lower grades, or whether lower grades might cause mental health difficulties (e.g. Luthar & Becker, Citation2002; Modin et al., Citation2015). There was also uncertainty as to how other variables might intersect with this, e.g. peer and family relations, body image issues, social media (e.g. Moksnes et al., Citation2010). This is where qualitative studies play an important role; they can facilitate a much deeper exploration of students’ lived experiences and understandings of mental health and academic achievement, and uncover possible connections between the two.

The findings of the review suggest that of central importance in producing girls’ achievement-related mental ill-health is fears for the future; namely, the need to gain entry into a good university (i.e. that ranks high in league tables) and obtain a good job (i.e. high status, high pay). This pressure can be reinforced – either directly or indirectly – by parents and families. The role that fear plays in education has been described by Jackson (Citation2013) as a powerful force that can operate in largely detrimental ways. Fear is widely acknowledged to be a notoriously slippery concept; some scholars see fear as pertaining to a sense of general unease that has an identifiable focus (e.g. Rachman, Citation1998), whilst others see fear as intensified when the focus is uncertain (e.g. Bauman, Citation2006). Tudor (Citation2003) further asserts that fear grows in intensity when negative outcomes are anticipated over a considerable length of time. What we might infer from the findings of this review is that, over the course of some girls’ schooling, fears for the future and of academic failure are likely to build in strength and intensity as exam “crunch points” loom larger. This resonates with the NHS Digital reports (NHS Digital, Citation2017, Citation2020) that demonstrate it is older teenage girls who are more likely to experience an emotional disorder.

We also found that intersectional dimensions “cut through” girls’ experiences (Crenshaw, Citation1989; Hill-Collins & Bilge, Citation2020) and differently shaped the reasons why a girl might encounter a particular set of pressures. For example, it was noted that working-class girls from ethnic minority backgrounds might feel under pressure to do well academically out of a sense of responsibility and duty to their families to reward them for their care and sacrifices made. In contrast, white middle-class girls might feel under intense pressure to succeed in highly pressurised and competitive elite school environments. Underpinning these intersectional forces, however, are powerful gendered discourses of girls as “good students” and “high achievers” emerging within a late 20th/early 21st century neoliberal performative educational context, in which student achievement and regimes of testing are of central importance (Ringrose, Citation2012). This appeared to contour how the girls – and the parents/families and school staff – in the studies understood achievement, “wanted it” for themselves, and the pressures they subsequently placed themselves under to succeed academically.

It is particularly noteworthy that six out of the eleven studies focused either wholly or partly on high performing, middle-class and/or single-sex school contexts. As previously discussed, there has been an historical focus placed on the pressures experienced by students in academic settings populated by the middle-classes – much 19th century concern was expressed in relation to the fragility of the middle-class girl, with little attention paid to her working-class equivalent who would likely have been in heavy duty domestic service at the time (Dyhouse, Citation1981). It might be that this link between upper/middle-classness and overpressure has grown up as a legacy and is something of an enduring discourse. Years later, Walkerdine et al. (Citation2001) note the ways in which class was playing out in the debates around girls in education in the latter years of the 20th century; they highlight continued concerns relating to middle-class girls’ academic achievements and their physical and mental health. They comment on this as a specific preoccupation of the middle-classes – a type of “class protection strategy” where girls must succeed against all odds in order to avoid “falling off the edge of rationality” and being cast in the same light as those deemed “the great unwashed” (Walkerdine et al., Citation2001, p. 186). This would seem to suggest that further research is needed to explore academic overpressure in relation to intersectionality and the differences which exist amongst those who self-identify as girls.

Overall, the findings of this review indicate that there are no groups of girls who are the immediate “winners” and are less likely to experience emotional distress because of their background characteristics. However, given the lack of specificity around ethnic groups and social classes in the samples (n = 6) and lack of studies discussing girls with additional identified disabilities (n = 1), we remain cautious in our interpretation and argue that more studies are required to investigate this topic that allow for analyses within and across key demographics. We also suggest that more nuanced theorisations of the relationship between gender, mental health and academic achievement are required if we are to fully appreciate how the three might be connected. We now turn attention to this.

Moving forwards: introducing a theoretical model of the “mental health/achievement see-saw”

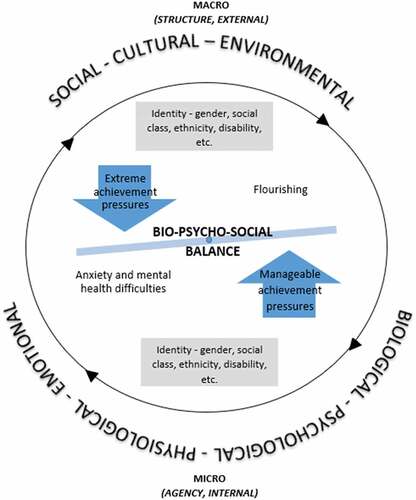

As noted in the findings, the notion of balance emerged from the texts as a seeming prerequisite for girls’ good mental health. We take up the concept of balance and use it to establish a conceptual framework for understanding how multiple factors might converge and influence the production of girls’ achievement-related mental ill-health – see .

As is evident in , we draw on the metaphor of the see-saw with a fulcrum at its centre. This creates both the possibility of balance but also a “tipping point”, where either side of the see-saw can move up or down. Drawing on insights from the located literature, we theorise that it is when complex interactions amongst internal factors (i.e. pertaining to the biological, psychological, physiological and emotional) take place in combination with the impact of external factors (i.e. social, cultural, physical, environmental) that girls’ mental health is produced and shaped. As indicated in the diagram through the circle that encases the see-saw, it is important that these internal and external factors are read together in order to avoid reductionism and the privileging of either the individual (biological/psychological) or social (cultural/environmental) over one another – we see both as mutually constitutive.

It should be noted that the concept of balance – and particularly in relation to mental health and wellbeing – is not new. Its origins can be traced as far back as ancient Greek medicine and the ideas of Hippocrates (c.460 BC–c.375 BC) and Galen (c.129 AD–c.210 AD), who practiced humoral medicine (Haggett, Citation2016). According to these early physicians, critical to good health was the notion of balance or “equilibrium” between the four humours, which consisted of black bile, yellow bile, blood and phlegm. Ill health was thought to be the result of an imbalance between the humours which could be cured by restoring balance (e.g. through purging, inducing vomiting). In fact, Galen saw the cause of melancholia, or what we today might understand as depression, as caused by an excess of black bile (Radden, Citation2002). Of importance for Galen and Hippocrates was the concept of “regimen” in helping to prevent disease (i.e. a balance of diet, exercise, rest, indulging in passions of the soul) – which might today resonate with the populist emphasis on a healthy and balanced lifestyle, thus stressing both individual and social factors.

The metaphor of girls’ achievement-related mental health as balanced on a see-saw enables us to illustrate visually how multiple pressures might converge and “press down” on the left arm of the see-saw – upsetting the delicate balance. In relation to the continuum model of mental health (Keyes, Citation2007), the fulcrum might be understood as representing the state of “coping”, and a downwards tip to the right arm of the see-saw would represent “flourishing”. For example, if a British-Chinese girl attending a highly competitive fee-paying all-girls’ English private school is failing to match the high grades of her contemporaries and is struggling to make friends due to racial prejudice, these pressures are likely to press down on the left arm of the see-saw and create an imbalance, potentially resulting in anxiety and emotional distress. The girl might be able to cope with these pressures – or eventually they might become “too much” – depending on the individual. The conceptual strength of the “mental health/achievement see-saw” model is that it allows for the possibility that mental health might be understood as having some sort of biological and/or psychological basis (i.e. brain structure and processing, genetics), but, it nevertheless emphasises that biological and psychological understandings must be read together with an appreciation of the social, facilitating a more holistic and “humanized” account of mental ill-health. Further research would, of course, be required to better understand the complex “folding together” or entanglement of the social, psychological and biological (e.g. see Youdell & Lindley, Citation2019).

The “see-saw” model also emphasises the precarious and non-static nature of academic achievement pressures – that might be understood as continually in flux and building up and receding over time, as students progress though schooling and enter new learning environments and contexts. According to this model, apparently dichotomous poles such as “achievement pressure/lack of pressure” and “mental distress/flourishing” are not to be interpreted as binary positions on a linear continuum – or four points on a dual-factor “compass” model – but are at once/simultaneously the same because of the inherent ontological tensions between the two; the dichotomous poles cannot exist without each other as they rely on their counter-poles in order to bring themselves into existence and facilitate representation (Archer, Citation2004; Hall, Citation1994). The positions are thus in constant suspension, processual and active – and with academic pressures experienced as “real”, “lived” and inscribed (sometimes painfully) on girls’ minds and bodies.

The “see-saw” model is designed to be a conceptual tool to bring together complex debates around mental health (i.e. individual v. social), gender (i.e. constructed v. biological) and achievement pressures, hold onto tensions, but also enable us to make some “provisional conceptual closures” (Archer, Citation2004, p. 462) that might enable us to move forwards and productively theorise and research social inequalities (i.e. commonalities and differences) across student experiences and locations. It is the researcher’s job to engage with these debates and make clearer the conditions under which students’ unique identity facets intersect with other micro and macro-level structural forces in order to produce schoolgirls’ achievement-related mental ill-health.

Whilst contributing theoretically, the “see-saw” model also has potential utility when translated into educational practice as it sharpens a focus on the significance of the social, and facilitates a focus on the origins of mental/emotional distress rather than treatment – the latter of which has tended to be foregrounded in biomedical approaches to addressing mental illness that have been influential in the fields of psychiatry and public health (Casstevens, Citation2010; Haggett, Citation2016); and that often form the basis of current school-based interventions or provision of support/referral systems (Fazel et al., Citation2014). It opens up possibilities for biopsychosocial interpositions in schools that seek to empower, de-pathologise and challenge deeply entrenched structural inequalities that might underpin and shape girls’ mental ill-health; such as stressors caused by family poverty, unhealthy pressurised school climates, and unhelpful discourses around “high achievement” that are gendered, classed, racialised and disablist. This moves beyond more surface-level attempts at mental health promotion apparent in some interventions that place responsibility for change on the shoulders of the individual, e.g. students being taught coping strategies and how to be resilient (O’Reilly et al., Citation2018; Weare & Nind, Citation2011). This could take the form of whole-school approaches that target not only individual students and their requirements, but also the school ethos and that challenge discriminating discourses and a culture of achievement, performativity and competition so evident in the educational system (for example, Ball, Citation2016).

Initial steps might be that the “see-saw” model can be used as a heuristic device and placed at the heart of discussion to encourage stakeholder groups (e.g. headteachers, senior school leadership teams, mental health/youth charity workers, health care professionals, policymakers) to think more deeply about how multiple factors might converge to produce girls’ achievement-related mental ill-health, and to structure open and honest discussion around gender and mental health. This is particularly important following the Covid-19 pandemic and potential learning loss, but also in light of emergent issues such as fears around sexual violence and “rape culture” in schools (Siddique, Citation2021). There is current debate as to what the future of education might look like following the pandemic (e.g. UNESCO, Citation2020), and the see-saw model might open up new opportunities and spaces within schools for school leaders, teachers and students to engage together in reflexive and critical thinking around the dominant identities, cultures and practices currently embedded in their institution. As a concrete example, sessions could be introduced where students can talk openly with staff about the achievement pressures they might be experiencing, how school might be contributing to this, and what practices could potentially be changed within their institution to alleviate this.

Conclusion

As this literature review covers a period of 30 years, some of the texts identified might be considered slightly dated (i.e. late 1990s/early 2000s), and so it is important to keep the dates of the studies in mind when interpreting the findings. It is also important to consider the extent to which the achievement-related factors affecting students’ mental health identified in this review might pertain exclusively to girls. It is arguable, for example, that fears for the future will be experienced by all young people regardless of gender given the highly uncertain and risky world in which we live (Beck, U, Citation1992) – that has become ever more precarious following the outbreak of Covid-19. It should be noted that identifying differences by gender was not the purpose of this review which focused exclusively on girls, but could be considered in future reviews.

What this review has done is to bring together qualitative insights pertaining to the significance of academic achievement pressures in shaping schoolgirls’ mental ill-health. Whilst the themes of fears for the future, parent/family-related pressures, competitive school cultures, and gendered expectations of girls’ academic achievement emerged strongly in the located texts, we found that it was when pressures were “imbalanced” and felt in the extreme that mental ill-health was more likely to be experienced by girls. In response, we have introduced the theoretical model of the “mental health/achievement see-saw” and have argued for its use as a conceptual tool to engage with deep-rooted complexities around the relationship between gender, mental health and academic achievement. We have also argued that the “see-saw” model has potential utility to a wide range of audiences including academics, educational practitioners, and policy makers, and might be usefully translated into educational practice in the form of biopsychosocial interpositions in schools that seek to empower, de-pathologise and challenge structural inequalities.

In terms of future empirical research, we see many opportunities. This review identified a relatively small number of texts that matched our inclusion criteria (n = 11), and limitations in terms of sample size and key demographics have already been highlighted. We see scope for qualitative studies that can engage more fully with the complexities that this review has highlighted; one possible example could be in-depth or multiple case-studies of schools in different catchment areas and/or geographical or national contexts, and with different structural organisations (e.g. comprehensive and private, mixed and single sex, rural and urban, large and small). There is a particular need for studies in non-OECD countries and in the global South, as insights are currently lacking from these regions. Such studies should take an intersectional approach and consider the experiences of girls – and boys, and those expressing different gender identities – from different backgrounds, and could incorporate a longitudinal or life history element so that possible changes in academic pressures can be mapped over time.

Although the findings suggest that elite schools can be particularly pressurised environments, this review has also highlighted the need for studies in non-elite settings, where the majority of young people study, and where quite specific achievement-related pressures might be experienced (e.g. to reward parents/families for sacrifices made). Illuminating the impacts of Covid-19 and how the pandemic might potentially exacerbate – or alleviate – the pressures that students experience in relation to the desire to succeed at school will also be important moving forwards.

We hope that, overall, this review has drawn further attention to the growing issue of girls’ mental ill-health, how schools/education might be implicated in its production, and might spark further conversation around this important and pressing topic.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the reviewers for their very helpful and insightful comments.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Child mental health provision in England is currently the responsibility of the NHS Child and Adolescent Mental Health Service (CAMHS), who adopt a four tier model of provision (see Pugh, Citation2015).

2. We recognise that “girl” is a potentially problematic term as it suggests a simplistic and essentialist binary between sexes/genders and lacks recognition of other gender identities e.g. transgender, gender neutral, gender fluid. However, we utilise the term “girl” in this review as it is commonly used as a classificatory term in contemporary society. We place a caveat that this review does not make claims as to how mental health and achievement pressures might be experienced by those expressing different gender identities.

References

- Antaramian, S. P., Huebner, E. S., Hills, K. J., & Valois, R. F. (2010). A dual-factor model of mental health: Toward a more comprehensive understanding of youth functioning. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 80(4), 462–472. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1939-0025.2010.01049.x

- Archer, L. (2004). Re/theorizing “difference” in feminist research. Women’s Studies International Forum, 27(5–6), 459–473. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2004.09.003

- Ball, S. J. (2016). Neoliberal education? Confronting the slouching beast. Policy Futures in Education, 14(8), 1046–1059. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210316664259

- Bauman, Z. (2006). Liquid fear. Polity Press.

- Beattie, T. S., Prakash, R., Mazzuca, A., Kelly, L., Javalkar, P., Raghavendra, T., Ramanaik, S., Collumbien, M., Moses, S., Heise, L., Isac, S., & Watts, C. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of psychological distress among 13–14 year old adolescent girls in North Karnataka, South India: A cross-sectional study. A Cross-sectional Study, BMC Public Health, 19(48), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-018-6355-z

- Beck, U. (1992). Risk society: Towards a new modernity. Sage.

- Bibby, T. (2011). Education – An ‘impossible profession’? Psychoanalytic explorations of learning and classrooms. Routledge.

- Burns, J. (2016, March 5). Improve children’s mental health care, head teachers urge. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/education-35730625

- Butler, J. (1990). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. Routledge.

- Casstevens, W. J. (2010). Social work education on mental health: Postmodern discourse and the medical model. Journal of Teaching in Social Work, 30(4), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/08841233.2010.515920

- Clough, P. T., & Halley, J. (2007). The affective turn: Theorizing the social. Duke University Press.

- Coleman, D. (2015). Traditional masculinity as a risk factor for suicidal ideation: Cross-sectional and prospective evidence from a study of young adults. Archives of Suicide Research, 19(3), 366–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2014.957453

- Connell, R. W., & Messerschmidt, J. W. (2005). Hegemonic masculinity: Rethinking the concept. Gender and Society, 19(6), 829–859. https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243205278639

- Connell, R. W. (1995). Masculinities. Polity Press.

- Connell, R. W. (1987). Gender and power: Society, the person and sexual politics. Polity.

- Conway, A. M. (2005). Girls, aggression, and emotion regulation. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 75(2), 334–339. https://doi.org/10.1037/0002-9432.75.2.334

- Coward, R. (2021). Covid has brought schoolchildren terrible stress – But they’ve also seen society at its best. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2021/jan/07/covid-schoolchildren-society

- Coward, R. (1984). Female desire: Women’s sexuality today. Paladin.

- Crenshaw, K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. University of Chicago Legal Forum, 1(8), 139–167. https://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8/

- Currie, D. H., Kelly, D. M., & Pomerantz, S. (2007). ‘The power to squash people’: Understanding girls’ relational aggression. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 28(1), 23–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425690600995974

- Deighton, J., Humphrey, N., Belsky, J., Boehnke, J., Vostanis, P., & Patalay, P. (2018). Longitudinal pathways between mental health difficulties and academic performance during middle childhood and early adolescence. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 36(1), 110–126. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjdp.12218

- Department for Education. (2018). Mental health and behaviour in schools: Departmental advice for school staff. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/755135/Mental_health_and_behaviour_in_schools__.pdf

- Department for Education. (2019). State of the nation 2019: Children and young people’s wellbeing. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/838022/State_of_the_Nation_2019_young_people_children_wellbeing.pdf

- Department of Health. (2015). Future in mind: Promoting, protecting and improving our children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/414024/Childrens_Mental_Health.pdf

- Department of Health & Department for Education. (2017). Transforming children and young people’s mental health provision: A green paper. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/664855/Transforming_children_and_young_people_s_mental_health_provision.pdf

- Dixon-Woods, M., Bonas, S., Booth, A., Jones, D., Miller, T., Sutton, A., Shaw, R., Smith, J., & Young, B. (2006). How can systematic reviews incorporate qualitative research? A critical perspective. Qualitative Research, 6(1), 27–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794106058867

- Duffy, J. (1968). Mental strain and “overpressure” in the schools: A nineteenth-century viewpoint. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences, 23(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/XXIII.1.63

- Dyhouse, C. (1981). Girls growing up in late Victorian and Edwardian England. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Dyhouse, C. (2013). Girl trouble: Panic and progress in the history of young women. Zed Books.

- Ekert, J., & Drago-Severson, E. (1999). Doing well and being well: Conceptions of well-being among academically successful adolescent girls of color in a Catholic school. Catholic Education: A Journal of Inquiry and Practice, 3(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.15365/joce.0302052013

- Eriksen, I. M. (2021). Class, parenting and academic stress in Norway: Middle-class youth on parental pressure and mental health. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 42(4), 602–614. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2020.1716690

- Fazel, M., Hoagwood, K., Stephan, S., & Ford, T. (2014). Mental health interventions in schools 1: Mental health interventions in schools in high-income countries. The Lancet Psychiatry, 1(5), 377–387. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)70312-8

- Foucault, M. (1977). Discipline and punish (A. Sheridan, Trans.). Penguin.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings 1972–1977. Harvester Press.

- Francis, B., & Paechter, C. (2015). The problem of gender categorisation: Addressing dilemmas past and present in gender and education research. Gender and Education, 27(7), 776–790. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2015.1092503

- Francis, B. (2008). Teaching manfully? Exploring gendered subjectivities and power via analysis of men teachers’ gender performance. Gender and Education, 20(2), 109–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250701797226

- Fröjd, S. A., Nissinen, E. S., Pelkonen, M. U. I., Marttunen, M. J., Koivisto, A.-M., & Kaltiala-Heino, R. (2008). Depression and school performance in middle adolescent boys and girls. Journal of Adolescence, 31(4), 485–498. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2007.08.006

- Frosh, S., Phoenix, A., & Pattman, R. (2002). Young masculinities: Understanding boys in contemporary society. Palgrave.

- Giota, J., & Gustafsson, J. E. (2017). Perceived demands of schooling, stress and mental health: Changes from grade 6 to grade 9 as a function of gender and cognitive ability. Stress and Health, 33(3), 253–266. https://doi.org/10.1002/smi.2693

- Günther-Hanssen, A., Danielsson, A. T., & Andersson, K. (2020). How does gendering matter in preschool science. Gender and Education, 32(5), 608–625. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2019.1632809

- Haggett, A. (2016). On balance: Lifestyle, mental health and wellbeing. Palgrave Communications, 2(1), 16075. https://doi.org/10.1057/palcomms.2016.75

- Hall, S. (1994). Cultural identity and diaspora. In P. Williams & L. Chrisman (Eds.), Colonial discourse and post-colonial theory: A reader (pp. 227–237). Harvester Wheatsheaf.

- Hill-Collins, P., & Bilge, S. (2020). Intersectionality (key concepts) (2nd ed.). Polity Press.

- Hill-Collins, P. (1991). Black feminist thought. Routledge.

- Hooks, B. (1982). Ain’t I a woman: Black women and feminism. Pluto Press.

- Humphrey, N., Lendrum, A., & Wigelsworth, M. (2010). Social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL) programme in secondary schools: National evaluation. DFE-RB049. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/197925/DFE-RB049.pdf#:~:text=Social%20and%20emotional%20aspects%20of%20learning%20%28SEAL%29%20programme,to%20promoting%20the%20social%20and%20emotional%20skills%20that

- Jackson, C. (2010). Fear in education. Educational Review, 62(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910903469544

- Jackson, C. (2013). Fear in and about education. In R. Brooks, M. McCormack, & K. Bhopal (Eds.), Contemporary Debates in the Sociology of Education (pp. 185–201). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Jaworski, K. (2014). The gender of suicide. Ashgate.

- Jordan, A., & Chandler, A. (2019). Crisis, what crisis? A feminist analysis of discourse on masculinities and suicide. Journal of Gender Studies, 28(4), 462–474. https://doi.org/10.1080/09589236.2018.1510306

- Kendall-Taylor, N., & Mikulak, A. (2009). Child mental health: A review of the scientific discourse. A FrameWorks research report. https://www.frameworksinstitute.org/assets/files/PDF_childmentalhealth/childmentalhealthreview.pdf

- Kessler, S., & McKenna., W. (1978). Gender: An ethnomethodological approach. John Wiley and Sons.

- Keyes, C. L. (2007). Promoting and protecting mental health as flourishing: A complementary strategy for improving national mental health. American Psychologist, 62(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.62.2.95

- Keyes, K. M., Gary, D., O’Malley, P. M., Hamilton, A., & Schulenberg, J. (2019). Recent increases in depressive symptoms among US adolescents: Trends from 1991 to 2018. Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology, 54(8), 987–996. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-019-01697-8

- King, T. L., Shields, M., Sojo, V., & Milner, A. (2020). Expressions of masculinity and associations with suicidal ideation among young males. BMC Psychiatry, 20(1), 228. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-020-2475-y

- Låftman, S. B., Almquist, Y. B., & Östberg, V. (2013). Students’ accounts of school-performance stress: A qualitative analysis of a high-achieving setting in Stockholm, Sweden. Journal of Youth Studies, 16(7), 932–949. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2013.780126