ABSTRACT

In societies where authoritarian and populist perspectives are on the rise, a focus on the concept of democracy within education can provide a meaningful space to reflect critically on, and disrupt, the status quo. In post-dictatorship Portugal, democracy has become a central symbolic concept within education policy and, in particular, Early Childhood Education (ECE) policy emphasises the importance of democratic citizenship within children’s personal and social development. Through a lens of critical pedagogy, we examine the diverse enactments of democracy at the classroom level within ECE settings in Portugal. By analysing interviews with twenty early years educators in three kindergartens, we identified ten concepts of democratic educational practice. Through observation of their classrooms, we explored divergent applications of these concepts in practice which embodied three distinct pedagogical approaches, which we termed instructive, responsive, and synergetic. These respectively enacted three styles of classroom democracy, which we described as procedural, interactive and critical democracy. We found that “critical democracy” was most evident where collaborative democratic spaces were created by educators who emphasised and enacted the values of listening, critical thinking, freedom, and respect.

Introduction

The importance of the practice of democracy within education is acute in current times, particularly in view of the erosion of democracy and the rise of populist nationalisms across the globe (Azevedo & Robertson, Citation2021; Rizvi, Citation2021). With education systems in turmoil in many countries, due to the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the time is ripe for re-examining the purpose and functions of schooling, and the ways in which we as educators can individually and collectively embrace democratic forms of pedagogy.

In a world where millions of people are marginalised because of their race, nationality, age, gender, sexuality and more, democracy is an important concept offering hope for a future where critical dialogue and cooperation are the norm and the oppressed are no longer voiceless. As Moss (Citation2007) describes:

Democracy creates the possibility for diversity to flourish. By so doing, it offers the best environment for the production of new thinking and new practice. (Moss, Citation2007, p. 7)

Early Childhood Education (ECE) is often a child’s first experience of what Arthur and Sawyer (Citation2009, p. 164) describe as “public community”, and potentially among their first experiences of democracy-related activities such as making conscious collective decisions. Kessler (Citation2018) convincingly argues that we have to experience democracy in order to imbibe and imbue democratic principles, and the early years classroom provides a potential space in which this process may (or may not) begin. ECE comprises both compulsory and non-compulsory education and can involve children from birth to age 8, depending on the national context. Rather than the formal transmission of knowledge and skills from teacher to student, prioritised in other sectors of education, ECE tends to take a more holistic approach in which parents and wider communities are more involved and children’s citizenship and participation are a key focus (Rinaldi in Hoyuelos, Citation2013, p. 23).

This article draws on empirical research conducted in three ECE settings in Portugal. Exploring the enactment of democracy in these spaces provides us with a powerful argument for a shift away from the somewhat empty rhetoric imposed as top-down “values”, and towards a form of “engaged pedagogy” (hooks, Citation1994, pp. 10–11) that recognises “each classroom as different, that strategies must constantly be changed, invented, reconceptualized to address each new teaching experience” (hooks, Citation1994). Drawing on ideas of critical pedagogy, we contribute to the growing body of research in early childhood education that brings this important arena to life by illuminating real-life practice, responding to Apple’s (Citation2018b) critique that critical pedagogy is often “overly rhetorical”. We focus on what Apple (Citation2018b, pp. 75–76) terms “the ‘stuff’ of schools, political and pedagogical actions”.

Portugal is an interesting location for this study because of the historic prevalence of democracy in its political rhetoric, as a deliberate and pervasive symbol of reparation from years of twentieth-century dictatorship. As Sousa and Oxley (Citation2021, p. 2) note, “Democratic education is strongly promoted in Portugal as an intended purpose and feature of ECE.” Recent gains by far-right political parties have reaffirmed fears regarding the vulnerability of democracy and highlighted the need for creating a renewed discourse and reconceptualising democratic practices that may have become stagnant through complacency. Paraphrasing Dewey (Citation1938), Hytten writes that democracy “requires ongoing attention and reconstruction” (Hytten, Citation2009, p. 404). ECE is a prime space in which this important process can grow and flourish.

We start by investigating the democratic discourses prevalent in ECE: first in broad terms and then in the context of Portuguese ECE. We then outline the research methods including interviews and observations within three kindergarten settings. We analyse educators’ perspectives on the conditions necessary for democratic practice in ECE. Finally, we explore how the key concepts were enacted in ECE classrooms and the ways in which different pedagogical styles manifested diverse understandings of democracy. By examining democratic practices in the classroom within a national socio-political context where the concept of democracy has a considerable rhetorical emphasis, we expose the diversity of narratives and activities at the grassroots level and bring them into sharp relief to inform and inspire others wishing to revitalise their own democratic pedagogy.

Democratic discourses in early childhood education

The term “democracy” is accorded so many divergent meanings and values, it risks becoming an “empty” concept, used and abused by its proponents and opponents in equal measure (Sousa & Oxley, Citation2021). Moraes (Citation2014, pp. 30–31) helpfully distinguishes between circumstances in which democracy could be perceived an “empty” signifier “because authorities were using it in situations where democracy was the most distant system of all” (for example, in dictatorships) and situations where democracy is more akin to a “floating signifier” in which the meaning of the term “fluctuates between different forms of articulation in different projects” but is never completely lost. As a concept heavily informed by political, economic and socio-cultural norms, democracy resides in what Beech (Citation2009) describes as the “complex combination between stability and malleability” (p. 355) as it is interpreted and enacted in all parts of society, including the education sphere.

We embrace the concept of democracy as a floating signifier, because this allows us to explore spaces for different types of democratic education within the classroom. By analysing the ways in which the ambiguity of the term results in divergent reconceptualisations and enactments in practice, we illustrate perspectives that encompass democracy as both a “system of social and political organisation” and “a personal way of life” (Kessler, Citation2018, p. 31). We perceive democracy as a “form of government” (Held, Citation2006, p. 1), a type of “political association” (Villoro, Citation1998, p. 95) and a socio-cultural phenomenon, expressed through the lived experience of each citizen.

In 1916, Dewey, a pioneer in the development of the concept of “democratic education”, argued that democracy was “a mode of associated living of conjoint communicated experience” (p. 87) and that education was a social process where social relationships formed the core of educational institutions. As Gollob et al. (Citation2010, p. 27) note, “School as a micro-society can support its students to acquire and appreciate key elements of a democratic and human rights culture.” We investigate how such key concepts may be manifested in the classroom through different pedagogical approaches, and illustrate how these differences reflect the ways in which teachers interpret the “floating” democratic discourses in their curricular contexts. In essence, this enables us to investigate “Deweyan democracy … as a way of life” (Tan & Whalen-Bridge, Citation2008) as it manifests in educational contexts.

Dewey (Citation1916) saw education and democracy as inextricably intertwined and suggested that educational institutions had the responsibility “to shape the ends of the educative process” (Olssen et al., Citation2004, p. 269) within their social relationships. Democratic education has a rich history and democracy has been defined as one of five recurring themes that characterise progressive approaches to schooling (Darling & Norbenbo, Citation2003). Many educational movements have emerged with democracy as a central tenet. Two of these, the Reggio Emilia project in Italy and the Modern School Movement (known as Movimento da Escola Moderna: MEM) in Portugal, arose as responses to the anti-democratic periods of fascism and dictatorship in the mid-twentieth-century. Reggio Emilia views the school as a profoundly democratic environment of shared relationships, and children as active constructors of their learning experiences (Rinaldi, Citation2006). Both children and adults are perceived as researchers who “possess the habit of questioning their certainties” and “assume a critical style” (Malaguzzi, Citation1998, p. 69). Thus, spaces arise for critical democratic education through which children are seen not as “citizens-in-waiting” or “future citizens” but instead as political beings with the right to influence, alter and shape their environments (Nichols, Citation2007).

The word “critical” here is important because it unearths one of the significant theoretical influences on democratic education movements and on our research: that of critical pedagogy, as advanced by Freire (Citation1970) and subsequent proponents of this movement. Freire (Citation1996, p. 146) argued that “No reflection about education and democracy can exclude issues of power, economic, equality, justice and its application to ethics.” Critical pedagogy, with its roots in critical theory, provides a lens through which we can effectively explore the ways in which these issues manifest in educational settings, sometimes as a direct response to injustice and oppression. Freire believed that democracy is achieved through the process of conscientização (conscientization), i.e. through “the development of the awakening of critical awareness” (Freire, Citation1976, p. 19). The word critical is itself interpreted in multiple ways, but shared conceptions of critical citizenship education stemming from critical pedagogy tend to include aspects such as politics, a collective focus, subjectivity and praxis (engaged reflection coupled with action) (Johnson & Morris, Citation2010), and such aspects are also found in many descriptions of democratic citizenship and democratic education (Freire, Citation1998; Niza, Citation1999; Moss, Citation2007; Biesta, Citation2011; De Groot & Veugelers, Citation2015).

ECE in many nations is increasingly being subjected to standardisation, evaluation and testing (Sousa et al., Citation2019), which Freire (Citation1998, p. 111) would have characterised as “asphyxiating freedom itself and, by extension, creativity and a taste for the adventure of the spirit.” Moss et al.'s (Citation2000) work identifies ways to build professional discourse and relationships as alternatives to such cultures of accountability. The work of Robertson et al. (Citation2015) on child-initiated pedagogies in Finland, Estonia and England explores democratic discourses and child-initiated pedagogies at the grassroots level. Likewise, by analysing democratic practice in Portuguese ECE settings we illustrate some of the efforts taking place at the classroom level to keep democracy alive and culturally significant.

In Portugal, democracy has been used symbolically as part of the post-dictatorship modernisation of the country and is treated as an elastic and malleable concept with different interpretations depending on the political regime in place (Sousa, Citation2017). The democratic discourses in the Portuguese education system have been explored in depth by Sousa and Oxley (Citation2021). They claim there is a certain duality to the rhetoric: from one perspective, it arose from revolutionary ideals centred on the “public good”; from another, the term is used so widely that it is in danger of becoming tokenistic and purely symbolic. Here the caution from Moraes (Citation2014) is prescient regarding the potential for terms to become “empty” signifiers rather than “floating” signifiers. The electoral gains of far-right politicians, who camouflage racist and oppressive rhetoric within a populist guise, illustrate the vulnerability of the Portuguese conceptualisation of democracy, despite the prevalence of the term democracy in political discourse.

Education was also portrayed as playing a functional role by aiming to “produce” citizens that could live in accordance with a democratic society. Portuguese ECE consequently experienced a process of democratisation over time, while responding to the different aims and demands of society. ECE provisions and practices also responded to the different views of children and different views of education which have emerged over time. As described in more depth by Sousa and Oxley (Citation2021), at the level of national ECE policy, democracy was enshrined in the “Framework Law for Pre-School Education” (Ministério da Educação, Citation1997a) and “Curricular Guidelines for Pre-School Education” (Ministério da Educação, Citation1997b), and this was maintained in the 2016 updates (Lopes da Silva et al., Citation2016).

The focus on constructing a democratic culture is common among “new and emerging democracies” (Biesta & Lawy, Citation2006, p. 63), and in post-revolution Portugal this was certainly prevalent in socio-political discourses. For example, one of the fundamental elements of MEM schooling in Portugal (Niza, Citation2012) is that children have the right to participate actively in the development of a democratic school culture. The movement arose from: “the effort of six teachers who had a democratic political-pedagogical intention that eventually found favourable conditions for its practical enactment” (Sousa, Citation2020, p. 165). Inside MEM professional circles,

democratic citizenship is learnt in the course of the cooperated management of the curriculum, passing by the cooperated construction of the knowledges and cognitive competencies, by the regulation of critical occurrences, by the reflection and deepening of responsibilities and the human rights in the democratic organisation of democracy inside and outside the school. (Niza, Citation2012, p. 385)

The settings

We conducted qualitative research within three educational settings in Portuguese ECE. These settings were:

A public (state) kindergarten for children aged 3–6 years.

An IPSS (independent non-profit institution) belonging to a religious order, for children aged 4 months to 6 years.

A private kindergarten, following the MEM approach, for children aged 4 months to 6 years.

The three settings researched were located in an urban area (geographically close to each other in a large city in Portugal). They were different in nature and size and catered for children from different socio-economic backgrounds. All the settings had different philosophies and approaches, as well as their own individual principles and missions. Nevertheless, they were guided by the same national policies and curriculum guidelines.

We analysed diverse sources of data including interviews with educators, classroom observations, kindergarten and classroom documents (such as Education Projects, Rules of Procedure, and Curricular Projects), and field diary reflections. We spent around six weeks observing the settings (2 weeks in each), focusing on the rooms with 1–6 year olds. Observations were written in field diaries and analysed in parallel with interview data.

Non-participant observations were conducted within two main areas of enquiry:

the different interactions between adults and children (interactions between adult–adult; children–adult; children–children in relation to the adult’s role/response) in the schools and classrooms visited; and

the organisation of institutional structures, organisation of spaces, routines and educational resources.

We conducted semi-structured interviews with twenty educators across the three kindergartens (working with all age groups), each interview lasting between 30 min and an hour. All educators interviewed were female and all were Portuguese; the majority had their own classrooms. They were all qualified early years teachers and had a range of classroom experience. Interviews were conducted in Portuguese and translated by the researchers. Linguistic differences have been explored in depth by the authors and some translations were adapted to reflect intended meanings in the context of Portuguese culture. During the interviews, participants were asked to reflect upon the first goal of pre-school education as outlined in the Framework Law for Pre-School Education (Ministério da Educação, Citation1997a), which stated that children should be exposed to democratic life experiences. Interviews also focused on educators’ understanding of ECE policies in their settings, curriculum and national legal frameworks; how these were reflected in their practices; and their perspectives on the manifestations of democracy in education. We employed critical analysis to identify themes and patterns in all the data collected. This analysis explored “the extent to which the interrelationships between dominant discourses […] and other social systems function in the constitution of subjectivities and the production of meaning” (Davies & Robinson, Citation2013, p. 42). All interviewee names in this article are pseudonyms.

The three different settings were investigated to provide a variety of loci through which to analyse democratic discourses. The research observations and interviews were conducted by a Portuguese ECE educator with extensive classroom experience, and we recognise that the data analysis is subject to biases and differences in power between the researcher and researched. Drawing upon analysis of qualitative data from all three settings, we explore pedagogical manifestations of democracy across all the classrooms investigated, but our intention is not to treat the schools as generalisable representative examples; rather we work towards analytic generalisation (Lincoln and Guba, Citation1990:57). Each perspective is interpreted in the context of its own ethos and identity, and these interpretations present broader implications for our understandings of ECE and democracy in classroom practice.

Our research sits within a constructivist paradigm and draws upon phenomenographic and phenomenological investigative and analytical methods. Rather than assuming that the conceptions discussed are “timeless, natural, unquestionable” (Rose, Citation1999, p. 20), we challenge taken-for-granted assumptions and aim to “interrupt the fluency of the narratives that encode” everyday life experiences (Rose, Citation1999). The research was conducted in accordance with institutional ethics procedures (using BERA, Citation2011) with institutional ethics approval; agreement was obtained for the classroom observations through discussion with school leaders, teachers, children and their parents.

Conceptualisations of democracy

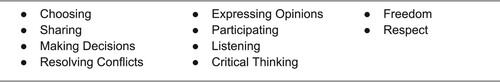

We analysed interviews with twenty Portuguese early years educators which explored the ethos, values and philosophies behind their practices. All educators identified democracy as an important pedagogical value and principle and referred to it at length, which allowed the researchers to identify common themes arising throughout the interviews. Ten key concepts emerged in educators’ interviews that were perceived as essential to democratic practice, which are listed in .

These concepts were embedded within educators’ discourses, reflecting some of the democratic principles and values articulated within Portuguese ECE policy documents. Educators variously used the key concepts in to describe their perspectives. One educator, for example, stated:

[Democracy is manifested] firstly through respect, through the opinion of each one, then for the chance that the children have to choose what they want to do, to choose or not to choose. The voice that we give to children, in other words, the chance that they have to speak their mind and to give their opinion even if it’s contrary to the other children’s, or even [contrary] to ours [adults]. Of respecting others, of listening to others, of giving the turn, of being listened to. This is a mini society: it is here that we train them for life out there. (Educator interview with Iris, IPSS Kindergarten)

In our actual global society it’s very important for [the child] to know that “my idea wasn’t chosen but I had a chance to present it and others respected it.” […] This leads to critical thinking. […] We can’t create children that are dependent on [adults], we can’t create egocentric children that are always the ones in charge. […] And this is very important for our whole society. (Educator interview with Magnólia, IPSS Kindergarten)

Educators had similar interpretations of the conditions necessary for democratic spaces to exist in ECE classrooms (i.e. the ten key concepts from ), but the ways in which democracy was manifested in practice were complex and diverse. While the discourse reflected many of the ideals and intentions defined by Portuguese ECE policies, the practices in the kindergarten classrooms were not uniform; this divergence is explored in more depth in the next section. The enactment of democracy was essentially part of a “Local Interpretation of a Larger Idea” (LILI) (Fleet, Citation2015) with its own semiotic complexity.

Enactments of democracy

By analysing educators’ discourses and observing their classrooms, we were able to differentiate between three pedagogical approaches to democratic practice. By “pedagogical approaches” we mean a value-laden “social process that involves educators and children in relationships” (Edwards, Citation2009, p. 61) in their day-to-day activities (see also Moss & Petrie, Citation2002). The three pedagogical approaches we identified were:

The Instructive pedagogical approach: the educator acted as a “master”, intentionally transmitting democratic discourses. This was a mainly “procedural” style of democracy, where the classroom norms tended to be formulated and directed by the adult, but were presented symbolically as democratic processes. In this pedagogical approach, all ten elements perceived by educators as necessary for the enactment of democracy (Choosing, Sharing, Making Decisions, Resolving Conflicts, Expressing Opinions, Participating, Listening, Critical Thinking, Freedom and Respect) tended to be regarded as equally important.

The Responsive pedagogical approach: the educator acted as a “mediator”, intentionally creating responses to situations based on the values they attached to democracy. We characterised this as a style of “interactive” democracy, in which democracy acted as a supportive mechanism within educational practice. In other words, educators placed value on certain concepts of democracy (Choosing, Sharing, Making Decisions, Resolving Conflicts, Expressing Opinions, and Participating) and used these intentionally in the classroom to mediate and respond to the children’s needs, desires and social interactions.

The Synergetic pedagogical approach: the educator acted as a supporter to the education process whilst intentionally creating “democratic spaces” within which the children could formulate collective norms and procedures through a process of collaborative agency, with the educator facilitating (rather than leading) this process. Educators using this approach tended to place most value upon the concepts of Listening, Critical Thinking, Freedom and Respect in the enactment of democratic classroom practice. The synergy between these discourses and their enactments made this a more “critical” democratic style, reflecting Freire’s (Citation1996) argument that: “If a teacher truly believes in democracy, he or she has no option […] than to shorten the gap between what he or she says and does” (p. 162).

The three approaches emphasised the key concepts listed in in divergent ways. Within the classroom, we found that enactments of democracy differed based on how educators interpreted their professional roles, both during different classroom activities and more broadly. Sometimes educators’ democratic practice involved the transmission of a symbolic discourse; sometimes it involved responding to a set of defined values; and sometimes it involved facilitating critical thought and action through a collaborative community approach.

Each educator shifted between pedagogical approaches based on the circumstances and the constraints of the classroom, but it was clear that the approaches represented a sort of continuum between a symbolic, surface-level interpretation of democracy and a deep, critical interpretation. For example, with regard to the concept of “choosing”, one educator might take an approach where they called childrens’ names and instructed them to choose from a range of pre-determined activities (the “Instructive” approach). Another might enable children to choose activities through negotiation with other children and the adults in the classroom about which resources they could use (the “Responsive” approach). Another might intentionally forge spaces for children to work together as a community to create their own projects (the “Synergetic” approach). Some educators might switch between the different approaches, for example earlier in the day there might be more time for a Responsive approach whereas under time pressure a more Instructive approach might be taken.

From our observations, we noted that the educators’ intentions were key to unlocking their democratic practices. Educators did not “accidentally” implement democratic practices: rather, democracy manifested in the classroom when the educators intentionally generated democratic discourses (which we call procedural democracy), constructed value-laden democratic responses to mediate between children (which we call interactive democracy) and created democratic spaces within which the children could co-construct their agency (which we call critical democracy). Educators’ intentions were influenced by their beliefs, their values, philosophies of the settings, external pressures and their understandings of their own roles as educators. As one educator explained:

We are free to choose what we believe in. And generally we, the educators in this kindergarten, follow a flexible pedagogy, of a constructivist orientation, basically flexible pedagogies, that aren’t rigid and that follow the interests, needs and characteristics of the group [of children]. (Educator interview with Begonia, Public Kindergarten)

outlines the three pedagogical approaches alongside the style of classroom democracy observed, the roles and key features of the educators, and the concepts emphasised as key to the enactment of democracy within each approach.

Table 1. Pedagogical approaches in democratic practice.

The three pedagogical approaches were observed in a range of classroom circumstances; the majority of educators did not practice a single approach at all times, but rather performed various roles (Master, Mediator or Supporter) at different points. As Malaguzzi notes, in democratic spaces the educator has the power to be someone:

who is sometimes the director, sometimes the set designer, sometimes the curtain and the backdrop, and sometimes the prompter … who is even the audience – the audience who watches, who sometimes claps, sometimes remains silent, full of emotion, who sometimes judges with scepticism, and other times applauds with enthusiasm. (Malaguzzi quoted in Rinaldi, Citation2001, p. 89)

Instructive pedagogical approach (educator as a master): procedural democracy

The educator observed the conflict and let children try to resolve it. Where the conflict was not resolved, the educator intervened by first listening and then talking to the children involved in the conflict. The educator reminded the children of the rules of the classroom, the rules of respectful coexistence and suggested a solution, which the children promptly accepted. The educator identified this as a form of democracy and in our analysis, we catalogued this as “procedural democracy”. Conflicts were resolved from an adult’s perspective rather than from a child’s perspective, and the educator was in complete control of the situation (a “Master”), imposing and reinforcing rules within a hierarchy. They were the regulators of the children’s conflict resolution processes: therefore the idea of children as political beings with the right to influence, alter and shape their environments (Nichols, Citation2007) was not present in a significant way.

Responsive pedagogical approach (educator as a mediator): interactive democracy

The educator observed the conflict and sat with the children while they listened to each other and talked through it. The educator encouraged children to express how they felt and asked them to think how they would feel if they were the other person. Together, through conversation, they discussed options and decided on a solution they were all happy with. The educator was perceived as a “Mediator” as they were working collaboratively with the children in order to help resolve the conflict. They shared and listened interactively, participated in resolving the conflict and supported children to make their own decisions about the conflict. There was an awareness of the role of children as citizens but also the role of an adult supporting children in the conflict resolution process and increasing awareness of the children’s agency. This was perceived by the researchers as a sort of step in-between procedural and critical democracy, as children could participate in a collaborative process of conflict resolution that might in some cases enable them to take steps towards resolving their own conflicts without adult intervention.

Synergetic pedagogical approach (educator as a supporter): critical democracy

Children were encouraged to resolve their own conflicts in collaboration with other children in the everyday life of the classroom. If a conflict was not easily resolved and the children felt they would like to discuss it further with others, they registered the conflict on a wall planner that had a column entitled “I didn’t like”. They did this by writing the nature of the conflict on this wall planner: for example, “I didn’t like that X used up all the play-doh and didn’t ask me first if I needed some to finish my construction”. They either wrote by themselves or with the help of an adult who would write what the children dictated to them. The children discussed these conflicts every Friday at a group meeting, where the disagreements were collectively explored. All sides were heard, and the group collaborated by engaging in discussion to find a solution. The educator asked the children to decide on resolutions/commitments to avoid similar conflicts in the future. Some of those resolutions were transformed by the group (children and adults) into classroom rules throughout the year. The researchers felt that this approach supported children to be autonomous and free in the spaces that the adults had intentionally created as part of their pedagogic practice. The classroom was essentially a mini-democratic society, creating and constantly revising rules while enabling children to express themselves, reflect and collaborate as critical citizens (Johnson & Morris, Citation2010).

This example illustrates the concrete ways in which the same democratic “key concept” from (Resolving Conflicts) was enacted differently in diverse classroom times and spaces. The pedagogical approach taken depended on the intentional efforts put in by the educators to permeate their practice with the democratic concepts and values they emphasised as most important.

All educators presented democracy as central within their discourse, and all the practices described in the example above could be described as democratic. However, it was clear from our observations that: the more educators brought a critical awareness of key concepts such as freedom and respect to their interpretation of democracy, the more likely they would be to move from instructive and responsive pedagogic approaches towards synergetic pedagogic approaches.

We argue that the approaches in portray a range, or spectrum, in which each approach builds upon the one to its left. The instructive approach represents a minimal commitment to democratic practice, in which the educator nods to democracy but it mainly remains symbolic. The responsive approach adds to this by emphasising democratic values in response to classroom situations in which circumstances allow. The synergetic approach builds upon the other two, co-creating spaces where the tools of symbolism and responsiveness are brought under the umbrella of more intentional manifestations of critical pedagogy based on freedom and respect.

Spaces for critical democratic practice

Democracy is a key part of the discourse within Portuguese education policy, and this was acknowledged and embraced by the majority of the educators interviewed, but their styles of classroom democracy (procedural, interactive, critical) varied depending on several factors:

The time they had with the children and other variables “in the moment”;

The extent to which they worked collaboratively with other educators and were able to openly share their values and perspectives;

Their critical awareness of the power they hold over children in the classroom that inevitably restricts their freedom;

Their confidence and security in their roles; and

The support of the educational institution and community involvement.

Educators who had the “space” to critically and collaboratively reflect on their practice tended to implement a more critical democratic style. The means of creating such spaces might be facilitated by the institutional norms within which they were working, by the community, and/or by educators themselves wishing to think “outside the box”. As one educator stated:

The kindergarten in itself does not limit us [educators], we have the freedom in each classroom to follow the pedagogy that we think best for our group. (Educator interview with Zinia, Public Kindergarten)

The enactment of critical democracy was influenced by educators’ attitudes towards the principles of participation and collaborative practice, and in particular stepping back and thinking critically about the decisions made by the adult for the child. By moving from superficial rhetoric to active reflection, educators started giving space for children to be co-constructors of their experience. Malaguzzi eloquently illustrated this process of transformation:

Stand aside for a while and leave room for learning, observe carefully what children do, and then, if you have understood well, perhaps teaching will be different from before. (Malaguzzi in Edwards et al., Citation1993, p. 77)

In practice […] it’s not because we say that children do a project each year in which they participate and give their opinion, that the school is a democratic school. It has nothing to do with that, democracy has to happen daily. It only makes sense to me to call it a democratic school if everyone has an opinion, everyone exists, and if in reality there are spaces and times to democratise democracy. (Educator interview with Sálvia, Private Kindergarten)

Often the adult gets frustrated when the child does not want to participate. It feels like the adult failed to respond to the interests of the child. However, it is important for the adult to be conscious that the child has the right to not participate. (Educator interview with Margarida, Private Kindergarten)

We talk a lot with each other and share what we do, and many times we give suggestions to each other. […] Deeply I think it is a sharing experience. (Educator Interview with Hortência, IPSS Kindergarten)

Conclusion

The three different pedagogical approaches described in (instructive, responsive, synergetic) are illustrative of the different ways in which democracy can be enacted in the classroom. Democracy manifested in each classroom as a multimodal package with “contextual configuration” (Jewitt, Citation2009), and such configurations were flexible, context-specific and heterogeneous. Our analysis and conclusions are based on our perspective that a critical democratic style is more meaningful than a procedural democratic and instructive democratic style. It is feasible that some readers may feel that this is an over-idealistic or even unrealistic portrayal of the potential for democratic enactment in education, but having observed the enactment of critical democracy in practice we are certain that this is a compelling and worthwhile endeavour through which children can explore and embed their sense of agency and citizenship from a young age.

Borman et al. (Citation2012) suggest that:

Educators themselves need to become boundary crossers in order to understand and nurture the strengths that a new generation brings into their experiences in school, at home and as global citizens. (Borman et al., Citation2012, p. viii)

We began this article by illustrating reasons why exploring democratic enactments within education is crucial at this time, when far-right movements and populist propaganda have the potential to take greater hold on society and to increase, rather than reduce, the oppression of marginalised populations. In its symbolic form, the concept of democracy can be taken for granted and easily converts into an “empty signifier” (Moraes, Citation2014) in which the educator purports to be following a democratic process but in fact holds on to all the power and control within the classroom.

From this perspective we propose that moving from a symbolic form of democracy, as manifested by the instructive pedagogical approach, to a more critical form such as the synergetic approach, potentially enables educators to counteract such harms as standardisation and testing in early years, and challenge anti-democratic authoritarianism in education. By critically engaging with the responsive and synergetic approaches to democratic pedagogy and working together in close collaboration, we educators can turn the “floating signifier” (Moraes, Citation2014) into a concrete and practical movement of meaningful encounters, border crossings and lived democratic experience.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Professor Paul Morris, Professor Peter Moss and Morag Walling for their support and guidance during the writing of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Apple, M. W. (2018a). The struggle for democracy in education: Lessons from social realities. Routledge.

- Apple, M. W. (2018b). Rightist gains and critical scholarship. Educational Review, 70(1), 75–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1388609

- Arthur, L., & Sawyer, W. (2009). Robust hope, democracy and early childhood education. Early Years, 29(2), 163–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575140802628776

- Azevedo, M. L., & Robertson, L. (2021). Authoritarian populism in Brazil: Bolsonaro’s Caesarism, ‘counter-trasformismo’ and reactionary education politics. Globalisation Societies and Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1955663

- Beech, J. (2009). Policy spaces, mobile discourses, and the definition of educated identities. Comparative Education, 45(3), 347–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060903184932

- BERA, British Educational Research Association. (2011). Ethical Guidelines for Educational Research.

- Biesta, G. J. J. (2011). Learning democracy in school and society. Education, lifelong learning, and the politics of citizenship. Sense Publishers.

- Biesta, G., & Lawy, R. (2006). From teaching citizenship to learning democracy: Overcoming individualism in research, policy and practice. Cambridge Journal of Education, 36(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640500490981

- Bloch, M. (1991). Critical science and the history of child development's influence on early education research. Early Education and Development, 2(2), 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15566935eed0202_2

- Borman, K. M., Danzig, A. B., & Garcia, D. R. (2012). Education, democracy, and the public good. Review of Research in Education, 36(1), 7–21. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X11424100

- da Educação, M. (1997a). Law n°5/97 (10 February) - framework law for pre-school education. Edition M.E.

- da Educação, M. (1997b). Curricular guidelines for pre-school education (vol. 1). Edition M.E.

- Darling, J., & Norbenbo, S. E. (2003). Progressivism. In N. Blake, P. Smeyers, R. Smith, & P. Standish (Eds.), The Blackwell guide to philosophy of education (pp. 288–308). Blackwell.

- Davies, C., & Robinson, K. H. (2013). Reconceptualising family: Negotiating sexuality in a governmental climate of neoliberalism. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 14(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.2304/ciec.2014.14.1.39

- De Groot, I., & Veugelers, W. (2015). Educating for a thicker type of democratic citizenship: A conceptual exploration. Education and Society, 33(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.7459/es/33.1.02

- Dewey, J. (1916). Democracy and education: An introduction to the philosophy of education. Macmillan.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Democracy and education in the world of today. In J. A. Boydston (Ed.), John Dewey: The later works, 1925–1953, vol. 13 (p. 298). Southern Illinois University Press, 1988.

- Edwards, C., Gandini, L., & Forman, G. (1993). The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach to early childhood education. Ablex.

- Edwards, S. (2009). Early childhood education and care. A sociocultural approach. Pademelon Press.

- Fleet, A. (2015 September 7–10). Making professional decision-making visible through Pedagogical Documentation [Paper presentation]. 25th European Early Childhood Education Research Association (EECERA) Annual Conference: ‘Innovation, Experimentation and Adventure in Early Childhood’, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, Spain.

- Formosinho, J., & Formosinho, J. O. (2012). Pedagogy in participation. Porto Editora.

- Freire, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Penguin Books.

- Freire, P. (1976). Education, The practice of freedom. Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative.

- Freire, P. (1996). Letters to Cristina: Reflections on my life and work. Routledge.

- Freire, P. (1998). Pedagogy of freedom. Ethics, democracy, and civic courage. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Gollob, R., Krapf, P., & Weidinger, W. (2010). Educating for democracy. Background materials on democratic citizenship and human rights education for teachers. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Held, D. (2006). Models of democracy (3rd ed.). Polity Press.

- hooks, b. (1994). Teaching to transgress. Education as the practice of freedom. Routledge.

- Hoyuelos, A. (2013). The ethics in loris Malaguzzi’s philosophy. Isalda.

- Hytten, K. (2009). Deweyan democracy in a globalized world. Educational Theory, 59(4), 395–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2009.00327.x

- Jackson, A., & Mazzei, L. (2012). Thinking with theory in qualitative research. Viewing data across multiple perspectives. Routledge.

- Jewitt, C. (2009). The Routledge handbook of multimodal analysis. Routledge.

- Johnson, L., & Morris, P. (2010). Towards a framework for critical citizenship education. Curriculum Journal, 21(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170903560444

- Kessler, S. (2018). Equality and democratic education evaluation: a way forward for RECE. In A. Ahrenkiel, K. I. Dannesboe, K. Prins, M. Broch Clemmensen, N. Kryger, & T. Ellegaard (Eds.), Inequality in Early Childhood Education and Care, 26th International RECE Conference (pp. 82–123). Copenhagen: DPU.

- Lee, W. (1994). John Dewey and Celestin Freinet: A closer look. In J. Sivell (Ed.), Freinet pedagogy: Theory and practice (pp. 11–26). The Edwen Mellen Press.

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1990). Judging the quality of case study reports. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 3(1), 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839900030105

- Lopes Da Silva, I., Marques, L., Mata, L., & & Rosa, M. (2016). Orientações curriculares para a educação pré-escolar [Curricular guidelines for pre-school education]. Ministério da Educação/Direção-Geral da Educação (DGE).

- Malaguzzi, L. (1998). History, ideas and basic philosophy: An interview with Lella Gandini. In C. Edwards, L. Gandini, & G. Forman (Eds.), The hundred languages of children: The Reggio Emilia approach (pp. 49–98). Ablex Publishing Corporation.

- Moraes, S. E. (2014). Global citizenship as a floating signifier lessons from UK universities. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning, 6(2), 27–42. https://doi.org/10.18546/IJDEGL.06.2.03

- Moss, P. (2007). Bringing politics into the nursery: Early childhood education as a democratic practice. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 15(1), 5–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930601046620

- Moss, P., Dahlberg, G., & Pence, A. (2000). Getting beyond the problem with quality. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 8(2), 103–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930085208601

- Moss, P., & Petrie, P. (2002). From children’s services to children’s spaces. Public policy, children and childhood. Routledge Falmer.

- Mouffe, C. (2000). The democratic paradox. Verso.

- Nichols, S. (2007). Children as citizens: Literacies for social participation. Early Years: An International Research Journal, 27(2), 119–130. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575140701425217

- Niza, S. (1999). Para quando uma educação para a cidadania democratica na escolas? In A. Nóvoa, F. Marcelino, & J. Ramos Do Ó (Eds.), Sérgio Niza. Escritos sobre educação (pp. 384). Tinta da China.

- Niza, S. (2012). No 50.o aniversario da declaração universal dos direitos humanos. [In the 50th anniversary of the universal human rights declaration]. In A. Nóvoa, F. Marcelino, & J. Ramos Do Ó (Eds.), Sérgio Niza escritos sobre educação (pp. 382). Tinta da China.

- Olssen, M., Codd, J., & O'Neill, A. (2004). Education policy: Globalization, citizenship and democracy. Sage.

- Rinaldi, C. (2001). The pedagogy of listening: The listening perspective from Reggio Emilia. Innovations in Early Education: The International Reggio Exchange, 8(4), 1–4.

- Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia. Listening, researching and learning. Routledge.

- Rizvi, F. (2021). Populism, the state and education in Asia. Globalisation. Societies and Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2021.1910015

- Robertson, L. H., Kinos, J., Barbour, N., Pukk, M., & Rosqvist, L. (2015). Child-initiated pedagogies in Finland, Estonia and England: Exploring young children's views on decisions. Early Child Development and Care, 185(11–12), 1815–1827. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2015.1028392

- Rose, N. (1999). Powers of freedom: Reframing political thought. Cambridge University Press.

- Sousa, D. (2017). ‘Revolution’, democracy and education: An investigation of early childhood education in Portugal [unpublished doctoral dissertion]. UCL (University College London).

- Sousa, D. (2020). Towards a democratic ECEC system. In C. Cameron, & P. Moss (Eds.), Transforming early childhood in England: Towards a democratic education (pp. 151–169). UCL Press.

- Sousa, D., Grey, S., & Oxley, L. (2019). Comparative international testing of early childhood education: The democratic deficit and the case of Portugal. Policy Futures in Education, 17(1), 41–58. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318818002

- Sousa, D., & Oxley, L. (2021). Democracy and early childhood: Diverse representations of democratic education in post-dictatorship Portugal. Educational Review, 73(1), 17–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1556609

- Tan, S., & Whalen-Bridge, J. (2008). Democracy as culture: Deweyan pragmatism in a globalizing world. State University of New York Press.

- Villoro, L. (1998). Which democracy? In C. Bassiouni, D. Beetham, M. Justice, F. Beevi, A. Boye, A. El Mor, H. Kubiak, V. Massuh, C. Ramaphosa, J. Sudarsono, A. Touraine, & L. Villoro (Eds.), Democracy: Its principles and achievement (pp. 95–103). Inter-Parliamentary Union.