ABSTRACT

Early childhood education and care programmes provide opportunities to enhance children’s learning and development, especially when high-quality learning experiences and educator-child interactions are embedded within them. However, the quality of early childhood education programmes varies greatly. Quality in early childhood education and care is conceptualised in three domains: structural, process and system. Understanding how to drive quality improvements in early childhood education and care relies on clear, consistent evidence concerning each of these domains, however, the current literature is not comprehensive. This scoping review maps the extent and consistency of the research literature in each domain of quality to identify knowledge gaps and inform future research. Through a search of the peer-reviewed literature, 85 meta-analyses and systematic reviews meeting our inclusion criteria were identified. We found a wide variation in the number of included studies in each domain and sub-domain of quality. We found the greatest number of meta-analyses and systematic reviews related to programmes, interventions, and curricula (process quality) and professional development and support (structural quality). The literature included in this scoping review is heterogeneous and of varying methodological quality, with inconsistent or contradictory findings. The research is most consistent in relation to pedagogy, professional development and support, and programmes, interventions, and curricula (process quality) and learning environments (structural quality). Interactions between the different domains of quality are complex and future research should focus on the associations between different features of quality in early childhood education programmes and practices that are critical to implementing successful continuous improvement initiatives.

Introduction

The body of international research on the early years of human development provides a compelling argument for the provision of high-quality early learning experiences in the years before school. Children’s earliest experiences provide the momentum for substantial development and growth and lay a foundation for life-long learning (Phillips & Shonkoff, Citation2000). These early experiences are vastly different depending on the environments in which children live, grow, and learn, and can be influenced by relatively small shifts in the actions and interactions of parents, carers and educators (Asbury & Plomin, Citation2013).

Children’s learning environments include those in early childhood education and care (ECEC) services. ECEC is defined, in this review, as any early childhood education and care service provided to groups of children outside of their home environment in the years before they start formal school (Sincovich et al., Citation2020). This includes kindergarten or preschool providing an education programme, and long-day care and family-day care for infants, toddlers and young children. The chosen definition is broad enough to ensure that international literature is captured in the review, regardless of the contextual factors in different countries. The evidence is clear that these high-quality early learning experiences benefit children’s cognitive, language and social development in the short- and long-term, particularly for children from disadvantaged backgrounds (Campbell et al., Citation2008; Fox & Geddes, Citation2016; Melhuish et al., Citation2015; Ramey & Ramey, Citation2005; Taggart et al., Citation2015).

However, quality in early childhood education contexts is a multidimensional concept and at the centre of much debate amongst academics, researchers, policy makers, and practitioners (Wysłowska & Slot, Citation2020). Sociocultural perspectives (Vygotsky, Citation1978) and bioecological theory (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, Citation2007) provide frameworks to identify the features of quality. Internationally, features of quality in ECEC have been characterised as falling within two domains: “structural quality” and “process quality” (Dowsett et al., Citation2008; Mashburn et al., Citation2008; Vandell & Wolfe, Citation2000). Other taxonomies of quality in ECEC have been proposed which include operational features, educational concepts and the classroom environment in the structural domain (OECD, Citation2006; Pianta et al., Citation2016), and interactions, parent engagement and experiences in the process domain (OECD, Citation2006; Pianta et al., Citation2016; Urban et al., Citation2012). More recently Torii et al. (Citation2017) identified “system quality” as a third domain. In this review we adopt this three-domain approach, in order to clearly articulate the difference between “system” level supports to quality such as funding and regulatory standards and the “structural” supports to quality such as staff qualifications, group size and ratio of staff to children. Arguably, despite differences in terminology, the broad domains of structural, process, and system quality can encapsulate the full range of quality features.

Structural quality is typically understood to include features such as the learning environment, educator qualifications, and educator-child ratios. Also included within structural quality are professional development activities, learning frameworks to guide educational programming and practice, and supports that build learning opportunities in the home environment (OECD, Citation2006; Pianta et al., Citation2016; Torii et al., Citation2017). Process quality encompasses children’s experiences within ECEC, with a focus on educator pedagogy and effective teaching strategies, educator-child interactions, programmes, curricula and learning interventions and social-emotional support. It relates to the participation of children in ECEC programmes, including the daily back-and-forth exchanges children have with educators and their peers (Burchinal et al., Citation2008; Pianta et al., Citation2016; Torii et al., Citation2017). The importance of curriculum in driving quality improvement and children’s learning and development has also been described as a feature of process quality (OECD, Citation2006). System quality consists of factors such as governance and regulatory standards and the degree of investment in services and programmes (Torii et al., Citation2017).

While the value of high-quality practice across each domain is clear, the provision of high-quality ECEC is still lacking in many jurisdictions and services (Torii et al., Citation2017). This is particularly the case when taken from the view of an individual child’s typical experience in ECEC, where the frequency and quality of interactions with educators has been found to be relatively low (Pianta et al., Citation2016; Tayler et al., Citation2013). As such, a better understanding of how to drive quality improvements is imperative for enhancing quality ECEC and learning and development outcomes for all children.

A wide range of approaches to continuous improvement in each quality domain have been applied worldwide (Navarro-Cruz & Luschei, Citation2018; OECD, Citation2006; Torii et al., Citation2017; Urban et al., Citation2012). These have included changes to system quality, for example through improvements to national policies, funding allocations and regulatory or evaluation frameworks. Changes to structural quality have included enhanced educator training, working conditions and career pathways. Improvements to process quality have developed enhanced curriculum programmes designed to improve educator-child interactions and improved pedagogical leadership. Prior research on the outcomes of these initiatives indicates variable effects of such interventions, while also identifying which specific features may be most effective at improving quality and supporting children’s learning and development (European Commission, Citation2020; Melhuish et al., Citation2015; Pianta et al., Citation2016).

Making the policy decisions and practice changes required to continue to drive quality improvement in ECEC is a complex undertaking. It relies on clear, consistent, and high-quality evidence within and across all domains of quality. It requires an understanding of the nuances in the research literature regarding which domains of quality are the key drivers of young children’s learning and development, what the key factors and thresholds for impact on educators and/or children are within each domain, and how the domains are interrelated.

While existing research provides indications of the most effective levers of change, for example pedagogy and interactions (Melhuish et al., Citation2015; Pianta et al., Citation2016), professional development (European Commission, Citation2020), and system level accreditation processes (European Commission, Citation2020), the current body of literature is not comprehensive. There is significant variation in the amount of research which has been undertaken in each domain of quality. The evidence that does exist is heterogeneous in nature and of varying methodological quality, with inconsistent and at times, contradictory findings. As a result, it is challenging for policy initiatives to target or achieve change in the key drivers of quality improvement.

In addition, the literature in the field has not been comprehensively synthesised. The presence of a number of meta-analyses or systematic reviews alone does not provide overarching insights into the extent of the evidence in a given field (van de Glind et al., Citation2013). It is not until these findings are drawn together that insights helpful to researchers, policy makers or practitioners become accessible. A scoping method is an appropriate approach to achieve this, as outlined below.

The current study

This scoping review will map the extent and consistency of the literature in ECEC on each domain and sub-domain of quality in order to identify gaps in knowledge and to inform a future research agenda. Scoping reviews are useful for clarifying working definitions, summarising key concepts, and identifying the breadth of and gaps in the evidence in a field (Arksey & O’Malley, Citation2005; Levac et al., Citation2010; Munn et al., Citation2018; Peters et al., Citation2015). While scoping reviews are more commonly used in health research than in educational research, they are particularly helpful for understanding topics such as this, in which the evidence is heterogeneous, unevenly distributed and not amenable to a traditional systematic review (Munn et al., Citation2018; Peters et al., Citation2015).

The research questions for this scoping review are broad to allow for a wide-ranging summary of the breadth of literature in the field. To maintain clarity and focus, however, they are accompanied by an articulated scope of enquiry clearly linked to the purpose of the study (Levac et al., Citation2010).

The research questions for this study are aligned to the purpose of mapping the literature and informing a future research agenda. They are:

What is the extent of the research literature in the domains of quality in ECEC?

How consistent are the key findings of the research literature reviewed in each sub-domain of quality in ECEC?

Method

The scope of this study is concerned with ECEC settings and services, the educators who work in these services, and the children who access them. Throughout the paper we use “educator” as the broad term to include all adults, qualified teachers and educators, working with children in ECEC settings. The core concept of interest is the quality of ECEC programmes and practice, which is defined according to the structure, process, and system domains, as outlined above. The key outcomes of interest are closely tied to these domains of quality: changes to educators’ practice and changes to children’s outcomes. To ensure that the findings are meaningful and address our research questions, only rigorous peer reviewed meta-analyses and systematic reviews were included.

The methods used in this review were informed by the guidance for scoping reviews provided by Peters et al. (Citation2015) and scoping study methods outlined by Levac et al. (Citation2010). In line with these approaches, the following steps were taken in this scoping review: (1) identification of the review purpose, research question and scope of the enquiry; (2) definition of eligibility criteria; (3) search of the literature; (4) selection of included studies; (5) extraction of results; (6) analysis; and (7) presentation of results. The presentation of results in this article was informed by the revised PRISMA guidelines for scoping reviews (Tricco et al., Citation2018). The purpose of the research and the research questions are outlined above (step 1). The definition of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for the study, the search and screening strategy and the planned approach to data extraction and analysis are outlined below (steps 2–6), followed by a presentation of results (step 7). The protocol for the broader study was registered with the OSF Registries (URL: https://osf.io/rdc5j/).

Search strategy

A multi-disciplinary team contributed to the development of the following search strategy for this study, aligned closely with the research questions. A method akin to a rapid evidence assessment (Barends et al., Citation2017), the search strategy for a scoping study is comprehensive yet practical and feasible. However, the limits set for the search strategy must not compromise the ability of the search to answer the research questions (Levac et al., Citation2010).

In education as well as in medicine, policy makers and practitioners look to secondary sources such as meta-analyses and systematic reviews to summarise and critically appraise available evidence (van de Glind et al., Citation2013). Due to their use of explicit and reproducible methods to systematically search, critically appraise, and synthesise literature on a specific issue, systematic reviews and meta-analyses provide reliable estimates of effects and reduce biases and random errors that may be present in individual studies (Gopalakrishnan & Ganeshkumar, Citation2013). Consequently, they provide a comprehensive and reliable summary of multiple studies. In acknowledgement of the value of such syntheses (Joanna Briggs Institute, Citation2013; Murad et al., Citation2016), our search strategy commenced with a search of academic databases for systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses relating to quality in ECEC published between 2015 and 2020. Limiting our search to this 5-year period ensured that the included syntheses were current and the overall number manageable, whilst also highlighting that the studies included within each of the syntheses resulted in a much wider time-span of literature that was reviewed.

In 2020 searches were completed in the following academic databases: ERIC (EBSCO), Education Databases (ProQuest), PsycINFO, Education Research Complete, A+ Education, Educational Administration Abstracts, Socindex with full text, Web of Science, Google Scholar.

Searches of academic databases used the following terms: Early childhood education (including kindergarten, pre-kindergarten, child care, day care, family day care, nursery, early learning, preschool or playgroup); and review or meta-analysis; and/or quality. Synonyms, alternative spellings, and thesaurus terms were used for each term. Specific search terms, filters and strategies were defined to align with the conventions for each database and Boolean operators “OR” and “AND” were used to combine the terms. Hand searches of reference lists and grey literature were used to augment database searches. Refer to Appendix A for the search strategy.

Eligibility criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied to the initial screening of titles and abstracts in line with the purpose and scope of the study: (i) the population of interest for this review was children aged birth to six years old attending kindergarten, preschool or ECEC services, and/or educators of those children; (ii) articles were included if they pertained to an ECEC service or programme, as defined above and there was no restriction on the geographical area; (iii) studies were included if they reported an outcome relating to any domain of quality, including outcomes such as improved service environments (structural quality), teaching practices (process quality), system improvements or children’s learning and development outcomes; (iv) meta-analyses and systematic literature reviews were included; (v) peer-reviewed articles published in English between 2015 and 2020.

During the full-text screening of records an assessment of methodological quality was completed according to the relevant National Institutes of Health (NIH) Study Quality and Assessment tool pertaining to the study methodology (National Institute of Health Research, Citation2019). Articles were excluded if they were rated as “poor” quality using these criteria. A quality review is not required for scoping reviews (Peters et al., Citation2015); however, to interpret the findings in relation to the research questions for this study, it was deemed appropriate to exclude poor-quality studies or articles (Levac et al., Citation2010).

Selection of included studies

The title and abstract of each record sourced through the search strategy was screened for inclusion by members of the research team independently and identified for full-text screening if they met the inclusion criteria above. Subsequently, the full text of each identified article was screened for inclusion by two members of the research team independently with reference to the complete set of inclusion and exclusion criteria described above. Inter-rater agreement at this stage was classified as substantial to near-perfect with Cohen’s Kappa ranging from 0.61 to 0.85 between reviewers (McHugh, Citation2012). Discrepancies were resolved by a third member of the research team, if necessary, at each stage. Referencing software was used to compile search results and Covidence systematic review software was used to record and track selection decisions.

Data extraction

The research team collectively determined which variables to extract or “chart” (Levac et al., Citation2010) for each included study. These included: (i) study details (including: authors, year, country/s, study type); (ii) research question/s and/or objective/s; (iii) domains of quality considered/included (see ); (iv) study specific inclusion criteria and key characteristics of studies; (v) number of included studies; and (vi) key findings in relation to domains of quality.

Table 1. Definitions of domains and subdomains of quality used.

Data were extracted using Covidence systematic review software. Ten per cent of records were screened by at least two authors independently prior to commencing data extraction from remaining records. This allowed the research team to discuss discrepancies and refine the process for the variables to be extracted by individual researchers.

Included studies were independently rated as either of “good” or “fair” methodological quality by two authors using the NIH Study Quality and Assessment Tool for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (National Institute of Health Research, Citation2019). Studies rated as “poor” had already been excluded. Discrepancies in the rating were resolved by a third author where necessary.

Data analysis

Following data extraction, descriptive statistics were used to illustrate the extent of the literature pertaining to each domain and sub-domain of quality. The domains and sub-domains of quality used as analytic categories are detailed in and are based on the work of Torii et al. (Citation2017), the OECD (Citation2006), Pianta et al. (Citation2016) and Urban et al. (Citation2012). This allowed the identification of gaps in the research pertaining to each domain and sub-domain.

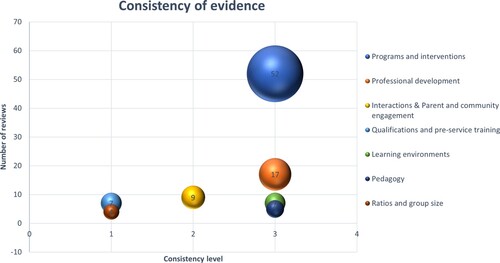

A consistency ranking was then determined to apply to studies in each sub-domain of quality. Using an approach similar to that described by the Education Endowment Foundation (Citation2018) a consistency ranking of high (3), moderate (2), or low (1) pertaining to each sub-domain of quality was generated following a qualitative review of the key findings in included studies conducted independently by two authors. Discrepancies were resolved via discussion.

Consistency was defined as the “consistency of the estimated impacts across the studies that have been synthesised” (EEF, Citation2018, p. 30). In this scoping review, a “high” degree of consistency referred to studies in which findings almost universally indicated the positive impact of a given sub-domain on ECEC quality or children’s learning and development outcomes, or, conversely, evidence which almost universally indicated negative or no impact on quality or children’s outcomes. A rating of “moderate” consistency indicates a general trend in findings in relation to impact, but with a reasonable proportion of studies indicating the opposite result or inconclusive findings. A rating of a “low” degree of consistency indicates that there is inconclusive evidence about the impact of a sub-domain of quality, or mixed evidence as to whether the impact was positive, negative, or null. Descriptive statistics were used to summarise the consistency of the findings in each of the sub-domains of quality.

The results were synthesised to achieve the objectives of the study. That is, the results were discussed in relation to the scope and gaps in the evidence base pertaining to each domain of quality and the consistency of findings.

Results

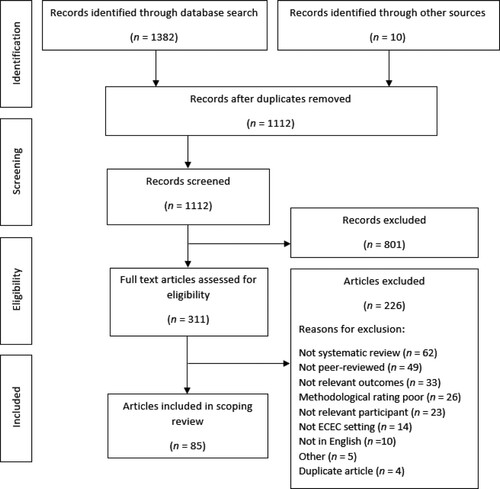

Eighty-five meta-analyses and systematic reviews were included in the review. presents the results of the search and screening process.

Characteristics of included studies

The characteristics of included meta-analyses and systematic reviews are outlined in . Of the included studies, 28 were systematic reviews, 33 meta-analyses, and 14 were both meta-analyses and systematic reviews. Meta-analyses and systematic reviews were published between 2015 and mid-2020 – the full range of our inclusion criteria. This included seven in 2015, 17 in 2016, 16 in 2017, 13 in 2018, 19 in 2019 and 13 in 2020. Studies included in the meta-analyses and systematic reviews were published between 1971 and 2019. Of the 55 meta-analyses or systematic reviews that stated the countries of their included studies, most (48) were in the USA alongside a wide range of other, mostly English-speaking, countries. Eighty-one meta-analyses and systematic reviews focussed on children, 28 on professionals and 9 on parents (noting that several studies targeted more than one of these groups, as can be seen in ). Meta-analyses and systematic reviews included a median of 27 papers in their analyses (range: 6–272). Of the included studies 40 were rated as “fair” and 45 rated as “good” quality.

Table 2. Characteristics of included studies.

Synthesis of results

Research question 1: What is the extent of the literature in the domains of quality in ECEC?

Sixty-four percent of the literature related to the process quality domain, with the structural quality domain representing another 31%. Six studies (5%) focussed on the system quality domain (see ). The most common sub-domain focus in the literature was on programmes, interventions, and curricula within the process quality domain (52 included studies), followed by professional development and support within the structural quality domain (16 included studies). The remaining sub-domains were the focus of between 1 and 9 meta-analyses or systematic reviews.

Table 3. Quality domains and subdomains addressed in included studies.

Research question 2: How consistent are the key findings of the review literature in the domains on quality in ECEC?

Following the ranking of consistency in included studies, we found that four sub-domains were highly consistent: Learning environments (structural), professional development and support (structural), programmes, interventions, and curricula (process) and pedagogy (process). The findings in relation to interactions (process), and parent and community engagement (process) were moderately consistent. These two sub-domains, each had the same number of reviews included (nine) and were given the same consistency rating, and therefore, are represented by the same colour (yellow) in . The findings in relation to ratios and group size (structural), and qualifications and pre-service training (structural) were inconsistent. We were unable to assign a consistency rating to system quality as the studies were too heterogeneous in their topics of study.

Structural quality

There was limited and inconsistent evidence about the impact of educator-child ratios or group size on quality, with only four meta-analyses or systematic reviews on this topic identified. The findings from these studies indicate that while group size may not be critical, lower ratios may have some bearing on improved process quality (Vermeer et al., Citation2016), particularly when the ratios are very low, such as 7:1 and lower (Bowne et al., Citation2017). In contrast, Perlman et al. (Citation2017) found that there was no evidence of a relationship between educator-child ratios and child outcomes.

Evidence from seven included meta-analyses and systematic reviews indicated that the learning environment – including both the physical environment and social context – of ECEC both affect quality. Findings from the included studies indicated that the physical environment can affect children’s behaviour, cognition, and emotion (Tonge et al., Citation2016). Influencing factors include the size of the play space and the opportunity to play outside (Tonge et al., Citation2016). There is overlap with the findings in this domain and findings in relation to system quality, including that the social contexts in which children from disadvantaged backgrounds and children with disabilities are included are important (Oh-Young & Filler, Citation2015; van Huizen & Plantenga, Citation2018). There were indications that the greatest gains for children were to be found within disadvantaged community contexts (van Huizen & Plantenga, Citation2018). There was limited evidence about whether home-based or centre-based care was associated with quality (Ang et al., Citation2017).

Seven included studies investigated whether educator qualifications were related to ECEC quality, but the findings were inconsistent. For example, Manning and colleagues found that educator qualification was associated with higher ECEC quality (Manning et al., Citation2017; Manning et al., Citation2019), yet Falenchuk et al. (Citation2017) and Nocita et al. (Citation2020) found that educators’ qualifications or specialist early childhood training was not related or only weakly associated with positive child outcomes. In addition, the effectiveness of professional development interventions was found to be unrelated to educators’ previous qualifications (Egert et al., Citation2018, Citation2020). In related findings, McMullen et al. (Citation2020) found that educators’ years of experience was not associated with quality.

Of the 16 meta-analyses and systematic reviews which investigated professional development and support, 12 indicated positive associations between professional development and either teaching practices (Albritton et al., Citation2019; Brock & Carter, Citation2017; Egert et al., Citation2018, Citation2020; Peleman et al., Citation2018) or children’s learning and development outcomes (e.g. Joo et al., Citation2020). One study found that the inclusion of professional development alongside an intervention made no difference (Joo et al., Citation2020) and one found mixed results (Ciesielski & Creaghead, Citation2020). The included studies indicated that professional development was most effective when it included features such as modelling and performance feedback (Brock & Carter, Citation2017). There were mixed results on issues of duration or frequency (dose) of professional development required to detect a change in practice (e.g. Brock & Carter, Citation2017; Rogers et al., Citation2020) but clear indications that forms of ongoing professional development which were integrated into practice such as coaching were likely to be effective (e.g. Kraft et al., Citation2018; Peleman et al., Citation2018; Rogers et al., Citation2020).

Process quality

Among the five included meta-analyses or systematic reviews, four found that pedagogical approaches such as sustained shared thinking (García-Carrión & Villardón-Gallego, Citation2016; Pesco & Gagné, Citation2017; Ulferts et al., Citation2019) and naturalistic instruction for children with disabilities (Snyder et al., Citation2015) have generally had lasting benefits on quality of educator practices and children’s learning and development. The fifth study found limited research on their pedagogical approach of interest (Pokorski et al., Citation2017). We identified a clear overlap between the findings related to pedagogy and other sub-domains within process quality, such as interactions.

Nine included studies (7.75%) investigated the relationship between educator-child interactions and quality of programmes and practice with four reviews indicating a positive relationship (García-Carrión & Villardón-Gallego, Citation2016; Roorda et al., Citation2017; Werner et al., Citation2016). One systematic review (Perlman et al., Citation2016) indicated that high-quality interactions were not associated with positive child outcomes but noted that the findings were inconclusive. Another found that interactions were related to quality, but this differed depending on the measure of quality used (Vandenbroucke et al., Citation2018). Six of the included studies found either a limited number of studies or poor methodology in the studies they included in their analyses.

Fifty-two meta-analyses or systematic reviews were identified that evaluated the effect of programmes, interventions, or curricula. Many of these findings were also included in summaries of other domains, as the interventions related to other quality areas, such as professional development and support (Egert et al., Citation2018; Jensen & Rasmussen, Citation2019; Kraft et al., Citation2018; Markussen-Brown et al., Citation2017) and educator-child interactions (García-Carrión & Villardón-Gallego, Citation2016). In the studies included in this domain most focussed on gains for children rather than quality as an up-stream measure (Blewitt et al., Citation2020). Of these, 37 reviews identified that the programmes, intervention, or curricula studied can positively influence children’s learning and development outcomes (Blewitt et al., Citation2018; Graham, Liu, Aitken, et al., Citation2018; Gunning et al., Citation2019; Joo et al., Citation2020; Murano et al., Citation2020; Sim et al., Citation2018; Wang et al., Citation2016) or behaviour (Bowman-Perrott et al., Citation2016). However, several of these reviews or meta-analyses found studies of low quality (Baron et al., Citation2017; Davenport et al., Citation2019; Sim et al., Citation2018; Tupou et al., Citation2019) or found few studies to include in their analyses (Alhassan et al., Citation2018; Kossyvaki & Papoudi, Citation2016; Luckner & Movahedazarhouligh, Citation2019). Other included meta-analyses and systematic reviews found mixed effects (Soto et al., Citation2019) or no evidence of a relationship between the intervention and positive outcomes (Fukkink et al., Citation2017; Ross & Joseph, Citation2019; Shepley et al., Citation2020).

Nine meta-analyses or reviews (7.75%) focussed on the topic of parent or community engagement, with inconsistent results. For example, Grindal et al. (Citation2016) found no differences in impact between programmes that included parent education and those that did not, while others found that the inclusion of parent programmes (Joo et al., Citation2020) or parental engagement (Ma et al., Citation2016) can lead to better outcomes for children. See and Gorard (Citation2015) found mixed results among their included studies.

System quality

We found only six meta-analyses or systematic reviews which investigated the relationship of system features to quality. The application of a consistency rating was not applicable to these studies as the elements of the system in focus varied widely between studies, from investment in ECEC (Dalziel et al., Citation2015; Razak et al., Citation2019) to the integration of services for children with additional needs (Jasmin et al., Citation2018; Oh-Young & Filler, Citation2015) and programme structure (Ang et al., Citation2017; van Huizen & Plantenga, Citation2018). A meta-analysis by van Huizen and Plantenga (Citation2018) found that full-time rather than part-time enrolment in preschool programmes may produce significant gains, but that age of enrolment does not appear to be important. There is also evidence that integrated services can support the learning and development of children with disabilities (Oh-Young & Filler, Citation2015). Having adequate funds to enable services to purchase equipment and resources may be important (Razak et al., Citation2019), however, the evidence on return on investment to wider society was found to be equivocal (Dalziel et al., Citation2015).

Discussion

The purpose of this scoping review was to determine the extent of the research literature in the domains of quality (structural, process and system) in ECEC and identify the consistency of key findings of the literature included in the review in each sub-domain of quality. The sub-domain of programmes, interventions and curricula within the process quality domain included the greatest number of studies by far, followed by professional development and support in the structural quality domain. Most sub-domains included a small number of studies (i.e. ≤9).

Based on our scoping review, there was high consistency in findings for several sub-domains (i.e. programmes, interventions and curricula; professional development and support; pedagogy and learning environments) and moderate consistency for interactions and parent and community engagement. However, many meta-analyses and systematic reviews presented contradictory evidence related to outcomes for either educators or children. It is difficult to reach an overarching conclusion regarding the considerable amount of literature for programmes, interventions and curricula, given the significant diversity that exists between studies. While the evidence consistently suggests that programmes and interventions are effective tools to drive children’s learning outcomes, further research is needed to identify if there are global characteristics or active ingredients of successful programmes, interventions, or curricula. Conclusions drawn from other sub-domains of quality may assist in identifying these characteristics, as some studies have identified particular foci embedded in programmes or interventions that demonstrate moderately consistent and positive outcomes, such as educator-child interactions.

Our findings suggest that the sub-domains of structural quality: professional development and learning environments consistently influence early childhood education programmes and practice. However, we also noted that most of the evidence has been gathered from centre-based programmes and that there is a need for further research exploring the impact of quality in home-based (family day) care compared to centre-based care. Other structural features, such as staff qualifications, pre-service training and ratios and group size were studied less frequently and contributed inconsistent and contradictory evidence regarding high-quality early childhood education. While there is consensus regarding minimum standards for qualifications, educator-child ratios and group size necessary for provision of high-quality preschool programmes (ACECQA, Citation2018) the evidence in these sub-domains of quality remains under-researched and equivocal. Furthermore, process quality must be supported by structural and system quality. Features of system and structural quality are understood as having more indirect impacts on children’s outcomes via supporting efforts to improve process quality (Burchinal, Citation2018; Urban et al., Citation2012).

Consequently, structural features provide the levers by which process quality can be the focus of quality improvement initiatives within early childhood education programmes. Several studies attest to the fact that sub-domains in structural quality have an impact on educator practice, if efforts to improve process quality are also embedded, for example targeting pedagogy and interactions within structural quality professional development initiatives. Equally, improving facilities and reducing ratios and group sizes have been found to allow for increases in high-quality educator-child interactions (European Commission, Citation2020; Melhuish et al., Citation2015).

The consistency of the evidence for the structural quality sub-domain: Professional Development was high in this review. Common features of professional development programmes emerging from the evidence were (i) include multiple learning components, (ii) practice-based, (iii) include coaching, (iv) adopt a collaborative approach, and (v) allow time for critical reflection on the implementation of new strategies. Professional development has been found to be effective in a range of service systems and settings, based on the range of international contexts included in the reviews for our analyses. Urban et al. (Citation2012) emphasise the development of competent early childhood professionals as a key lever to drive quality. However, they see this competence not as something resting solely with professional learning of individuals and their knowledge, skills, and attitudes, but as a characteristic of the ECEC system. In this way, individual competence is interdependent with and supported by system and structural features of quality in early childhood education; a “competent system”.

There are important caveats to be noted regarding the conclusions in this review. First, clear delineation between the domains of quality is not always possible and, in many studies, there is considerable overlap between the sub-domains. For our purposes, we used the primary focus when coding meta-analyses and systematic reviews to a domain and sub-domain. For example, a number of studies included the sub-domains of learning programmes or interventions, and pedagogy. Equally, evidence related to professional development often incorporates working with educators to improve the quality of their interactions with children. The “stacking” of several different quality features within evaluation studies can make it difficult to interpret outcomes within different (sub)-domains of quality. Potentially, professional learning programmes may have an impact on educator practice irrespective of the content knowledge focus (e.g. interactions) within them, however, understanding the independent impact of more than one subdomain of quality included in a study is often not feasible given the methodological approach adopted.

Importantly, this review highlighted that different study methodologies and the measurement of quality within studies contribute significantly to the contradictory evidence in several of the sub-domains of quality. Synthesising the evidence was further complicated by contested approaches to measuring quality (Burchinal et al., Citation2016; Caronongan et al., Citation2016) across many studies. How quality is defined and understood in the literature is reflected in the tools used to measure and assess quality; where some tools and regulatory practices focus more on structural features of quality and other tools prioritise process features. System and structural quality parameters are often addressed through accreditation or regulatory documents and standards of practice developed for national contexts, while measures of process quality have emerged through observational studies of educator-child interactions and children’s experiences within programmes (Pianta et al., Citation2008).

Limitations

In the context of this study, it is important to recognise that the literature notes multiple features related to the child, their family and community, as well as early education settings that interact to promote young children’s learning during the years prior to school. The focus of this review is on the features of high-quality early childhood education that can maximise the learning opportunities for all children participating in ECEC. Hence, this review and the included studies do not account for influences outside of ECEC, or for children not attending early childhood programmes.

It is important to acknowledge that any scoping review is limited by the inclusion and exclusion criteria applied to the published literature (Levac et al., Citation2010). By focusing on published meta-analyses and systematic reviews we may have missed the most recent examples of research in the field and relevant grey literature. Qualitative research is underrepresented in meta-analyses and systematic reviews, and consequently in this scoping review. Finally, we acknowledge that publication bias can influence the research literature that represents certain fields of study, and this could be the case in early childhood as it is in other fields that include intervention studies.

Conclusion

In this scoping review, we included meta-analyses and systematic reviews to determine the extent and consistency of the evidence of quality in early childhood education and care programmes. Results indicated that most studies pertained to programmes, interventions, and curricula (within process quality) and professional development and support (within structural quality). The evidence was most consistent in the following sub-domains of quality: pedagogy; professional development and support; programmes, interventions, and curricula (process quality); and learning environments (structural quality).

High-quality early childhood education and care has the potential to optimise all children’s learning and development prior to formal school (Melhuish et al., Citation2015). Implementing high-quality programmes that integrate intentional teaching within play-based, developmentally appropriate learning experiences is complex and requires investment in ongoing and differentiated professional support. This scoping review identified that there is limited research evidence for the impact of several domains of quality on both educator practice and children’s learning outcomes. Future research needs to build a more nuanced understanding of the relationships between the domains of quality, such as comparisons of different features of structural (e.g. home-based or centre-based care) and process quality (e.g. the active ingredients in early childhood play-based programmes and interventions) which lead to improved learning outcomes for children.

The extent and consistency of evidence pertaining to what constitutes high-quality early childhood education programmes varies across the domains of structure, process and system. When synthesised, the research literature suggests that first and foremost “quality” is not a singular concept. Quality features (or domains) are highly interdependent and interact together in complex and context-dependent ways. This scoping review goes some way towards understanding this complexity and future research should focus on the associations that are critical to implementing successful continuous quality improvement initiatives.

Acknowledgement

The authors wish to thank Ms Eileen Cini and Dr Amy Watts for their input during the screening of papers and with the final manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Albritton, K., Mathews, R. E., & Anhalt, K. (2019). Systematic review of early childhood mental health consultation: Implications for improving preschool discipline disproportionality. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 29(4), 444–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/10474412.2018.1541413

- Alhassan, S., St. Laurent, C. W., & Burkart, S. (2018). Preschool-based physical activity interventions in African American and Latino preschoolers: A literature review. Kinesiology Review, 7(2), 142–150. https://doi.org/10.1123/kr.2018-0006

- Ang, L., Brooker, E., & Stephen, C. (2017). A review of the research on childminding: Understanding children’s experiences in home-based childcare settings. Early Childhood Education Journal, 45(2), 261–270. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-016-0773-2

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Asbury, K., & Plomin, R. (2013). G is for genes: The impact of genetics on education and achievement. Wiley-Blackwell.

- Australian Children’s Education & Care Quality Authority (ACECQA). (2018). Guide to the national quality framework. http://www.acecqa.gov.au/national-quality-framework/the-national-quality-standard.

- Averett, P., Hegde, A., & Smith, J. (2017). Lesbian and gay parents in early childhood settings: A systematic review of the research literature. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 15(1), 34–46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1476718X15570959

- Barends, E., Rousseau, D. M., & Briner, R. B. (2017). CEBMa guideline for rapid evidence assessments in management and organizations, version 1.0. Center for Evidence Based Management.

- Barnes, T. N., Wang, F., & O’Brien, K. M. (2018). A meta-analytic review of social problem-solving interventions in preschool settings. Infant and Child Development, 27(5), e2095. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2095

- Baron, A., Evangelou, M., Malmberg, L., & Melendez-Torres, G. J. (2017). The tools of the mind curriculum for improving self-regulation in early childhood: A sytematic review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–77. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.10

- Barton, E. E., Murray, R., O’Flaherty, C., Sweeney, E. M., & Gossett, S. (2020). Teaching object play to young children with disabilities: A systematic review of methods and rigor. American Journal on Intellectual and Developmental Disabilities, 125(1), 14–36. https://doi.org/10.1352/1944-7558-125.1.14

- Berti, S., Cigala, A., & Sharmahd, N. (2019). Early childhood education and care physical environment and Child Development: State of the art and reflections on future orientations and methodologies. Educational Psychology Review, 31, 991–1021. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-019-09486-0

- Blewitt, C., Fuller-Tyszkiewicz, M., Nolan, A., Bergmeier, H., Vicary, D., Huang, T., McCabe, P., McKay, T., & Skouteris, H. (2018). Social and emotional learning associated With universal curriculum-based interventions in early childhood education and care centers. JAMA Network Open, 1(8), e185727–e185727. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.5727

- Blewitt, C., O’Connor, A., Morris, H., May, T., Mousa, A., Bergmeier, H., Nolan, A., Jackson, K., Barrett, H., & Skouteris, H. (2021). A systematic review of targeted social and emotional learning interventions in early childhood education and care settings. Early Child Development and Care, 191(14), 2159–2187. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2019.1702037

- Blewitt, C., O’Connor, A., Morris, H., Mousa, A., Bergmeier, H., Nolan, A., Jackson, K., Barrett, H., & Skouteris, H. (2020). Do curriculum-based social and emotional learning programs in early childhood education and care strengthen teacher outcomes? A systematic literature review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(3), 1049. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17031049

- Bowman-Perrott, L., Burke, M. D., Zaini, S., Zhang, N., & Vannest, K. (2016). Promoting positive behavior using the good behavior game: A meta-analysis of single-case research. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions, 18(3), 180–190. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098300715592355

- Bowne, J. B., Magnuson, K. A., Schindler, H. S., Duncan, G. J., & Yoshikawa, H. (2017). A meta-analysis of class sizes and ratios in early childhood education programs: Are thresholds of quality associated with greater impacts on cognitive, achievement, and socioemotional outcomes? Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 39(3), 407–428. https://doi.org/10.3102/0162373716689489

- Brock, M. E., & Carter, E. W. (2017). A meta-analysis of educator training to improve implementation of interventions for students with disabilities. Remedial and Special Education, 38(3), 131–144. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932516653477

- Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2007). The bioecological model of human development. In R.M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology ( Chapter 14, pp. 793–828). John Wiley & Sons.

- Brunsek, A., Perlman, M., McMullen, E., Falenchuk, O., Fletcher, B., Nocita, G., Kamkar, N., & Shah, P. S. (2020). A meta-analysis and systematic review of the associations between professional development of early childhood educators and children’s outcomes. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 217–248. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.03.003

- Burchinal, M. (2018). Measuring early care and education quality. Child Development Perspectives, 12(1), 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12260

- Burchinal, M., Howes, C., Pianta, R., Bryant, D., Early, D., Clifford, R., & Barbarin, O. (2008). Predicting child outcomes at the end of kindergarten from the quality of pre-kindergarten teacher-child interactions and instruction. Applied Developmental Science, 12(3), 140–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888690802199418

- Burchinal, M., Xue, Y., Auger, A., Tien, H.-C., Mashburn, A., Cavadel, E. W., & Peisner-Feinberg, E. (2016). Quality thresholds, features, and dosage in early care and education: Secondary data analyses of child outcomes: II. Quality thresholds, features, and dosage in early care and education: Methods. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 81(2), 27–45. https://doi.org/10.1111/mono.12237

- Camargo, S. P. H., Rispoli, M., Ganz, J., Hong, E. R., Davis, H., & Mason, R. (2016). Behaviorally based interventions for teaching social interaction skills to children with ASD in inclusive settings: A meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Education, 25(2), 223–248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-015-9240-1

- Campbell, F., Wasik, B. H., Pungello, E., Burchinal, M., Barbarin, O., Kainz, K., Sparling, J. J., & Ramey, C. T. (2008). Young adult outcomes of the Abecedarian and CARE early childhood educational interventions. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(4), 452–466. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2008.03.003

- Caronongan, P., Kirby, G., Boller, K., Modlin, E., Lyskawa, J., & Administration for, C., Families, O. of P. R., Evaluation, & Mathematica Policy Research, I. (2016). Assessing the Implementation and Cost of High-Quality Early Care and Education: A Review of the Literature. OPRE Report 2016-31. Administration for Children & Families.

- Castro, M., Expósito-Casas, E., López-Martín, E., Lizasoain, L., Navarro-Asencio, E., & Gaviria, J. L. (2015). Parental involvement on student academic achievement: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 14, 33–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2015.01.002

- Chambers, B., Cheung, A. C. K., & Slavin, R. E. (2016). Literacy and language outcomes of comprehensive and developmental-constructivist approaches to early childhood education: A systematic review. Educational Research Review, 18, 88–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2016.03.003

- Ciesielski, E. J. M., & Creaghead, N. A. (2020). The effectiveness of professional development on the phonological awareness outcomes of preschool children: A systematic review. Literacy Research and Instruction, 59(2), 121–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2019.1710785

- Dalziel, K. M., Halliday, D., & Segal, L. (2015). Assessment of the cost–benefit literature on early childhood education for vulnerable children. SAGE Open, 5(1), 215824401557163. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015571637

- Davenport, C. A., Watson, M., & Cannon, J. E. (2019). Single-case design research on early literacy skills of learners who are d/Deaf and hard of hearing. American Annals of the Deaf, 164(3), 363–380. https://doi.org/10.1353/aad.2019.0018

- Dowsett, C. J., Huston, A. C., Imes, A. E., & Gennetian, L. (2008). Structural and process features in three types of child care for children from high and low income families. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 23(1), 69–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2007.06.003

- Dunst, C., Hamby, D., Howse, R., Wilkie, H., & Annas, K. (2019). Metasynthesis of preservice professional preparation and teacher education research studies. Education Sciences, 9(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9010050

- Eddy, L. H., Wood, M. L., Shire, K. A., Bingham, D. D., Bonnick, E., Creaser, A., Mon-Williams, M., & Hill, L. J. B. (2019). A systematic review of randomized and case-controlled trials investigating the effectiveness of school-based motor skill interventions in 3- to 12-year-old children. Child: Care, Health and Development, 45(6), 773–790. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12712

- Education Endowment Foundation. (2018, July). Sutton Trust-EEF teaching and learning toolkit & EEF early years toolkit: Technical appendix and process manual. https://educationendowmentfoundation.org.uk/public/files/Toolkit/Toolkit_Manual_2018.pdf.

- Egert, F., Dederer, V., & Fukkink, R. G. (2020). The impact of in-service professional development on the quality of teacher-child interactions in early education and care: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 29, 100309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2019.100309

- Egert, F., Fukkink, R. G., & Eckhardt, A. G. (2018). Impact of In-service professional development programs for early childhood teachers on quality ratings and child outcomes: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 88(3), 401–433. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317751918

- European Commission. (2020). ET2020 Working group Early Childhood Education and Care: Final Report (Issue December). https://doi.org/10.2766/857178

- Falenchuk, O., Perlman, M., McMullen, E., Fletcher, B., & Shah, P. S. (2017). Education of staff in preschool aged classrooms in child care centers and child outcomes: A meta-analysis and systematic review. PloS One, 12(8), e0183673. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183673

- Fancher, L. A., Priestley-Hopkins, D. A., & Jeffries, L. M. (2018). Handwriting acquisition and intervention: A systematic review. Journal of Occupational Therapy, Schools, & Early Intervention, 11(4), 454–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/19411243.2018.1534634

- Fox, S., & Geddes, M. (2016). Preschool – two years are better than one: Developing a preschool program for Australian 3 year olds – evidence, policy and implementation. Mitchell Institute Policy Paper 3/2016 (Issue 03). www.mitchellinstitute.org.au.

- Fukkink, R., Jilink, L., & Oostdam, R. (2017). A meta-analysis of the impact of early childhood interventions on the development of children in the Netherlands: An inconvenient truth? European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 25(5), 656–666. https://doi.org/10.1080/1350293X.2017.1356579

- García-Carrión, R., & Villardón-Gallego, L. (2016). Dialogue and interaction in early childhood education: A systematic review. Multidisciplinary Journal of Educational Research, 6(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.17583/remie.2016.1919

- Gopalakrishnan, S., & Ganeshkumar, P. (2013). Systematic reviews and meta-analysis: Understanding the best evidence in primary healthcare. Journal of Family Medicine and Primary Care, 2(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.4103/2249-4863.109934

- Graham, S., Liu, X., Aitken, A., Ng, C., Bartlett, B., Harris, K. R., & Holzapfel, J. (2018). Effectiveness of literacy Programs balancing reading and writing instruction: A meta-analysis. Reading Research Quarterly, 53(3), 279–304. https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.194

- Graham, S., Liu, X., Bartlett, B., Ng, C., Harris, K. R., Aitken, A., Barkel, A., Kavanaugh, C., & Talukdar, J. (2018). Reading for writing: A meta-analysis of the impact of reading interventions on writing. Review of Educational Research, 88(2), 243–284. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317746927

- Grindal, T., Bowne, J. B., Yoshikawa, H., Schindler, H. S., Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2016). The added impact of parenting education in early childhood education programs: A meta-analysis. Children and Youth Services Review, 70, 238–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.09.018

- Gunning, C., Breathnach, Ó, Holloway, J., McTiernan, A., & Malone, B. (2019). A systematic review of peer-mediated interventions for preschool children with autism spectrum disorder in inclusive settings. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(1), 40–62. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-018-0153-5

- Jasmin, E., Gauthier, A., Julien, M., & Hui, C. (2018). Occupational therapy in preschools: A synthesis of current knowledge. Early Childhood Education Journal, 46(1), 73–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10643-017-0840-3

- Jensen, P., & Rasmussen, A. W. (2019). Professional development and Its impact on Children in early childhood education and care: A meta-analysis based on European studies. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(6), 935–950. https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2018.1466359

- Joanna Briggs Institute. (2013). JBI levels of evidence FAME. JBI Approach, October 2–6. http://www.joannabriggs.edu.au.

- Joo, Y. S., Magnuson, K., Duncan, G. J., Schindler, H. S., Yoshikawa, H., & Ziol-Guest, K. M. (2020). What works in early childhood education programs?: A meta–analysis of preschool enhancement programs. Early Education and Development, 31(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2019.1624146

- Kossyvaki, L., & Papoudi, D. (2016). A review of play interventions for children with Autism at school. International Journal of Disability, Development and Education, 63(1), 45–63. https://doi.org/10.1080/1034912X.2015.1111303

- Kraft, M. A., Blazar, D., & Hogan, D. (2018). The effect of teacher coaching on instruction and achievement: A meta-analysis of the causal evidence. Review of Educational Research, 88(4), 547–588. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654318759268

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lippard, C. N., Lamm, M. H., & Riley, K. L. (2017). Engineering thinking in prekindergarten children: A systematic literature review. Journal of Engineering Education, 106(3), 454–474. https://doi.org/10.1002/jee.20174

- Luckner, J. L., & Movahedazarhouligh, S. (2019). Social–emotional interventions with children and youth who are deaf or hard of hearing: A research synthesis. The Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education, 24(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1093/deafed/eny030

- Ma, X., Shen, J., Krenn, H. Y., Hu, S., & Yuan, J. (2016). A meta-analysis of the relationship between learning outcomes and parental involvement during early childhood education and early elementary education. Educational Psychology Review, 28(4), 771–801. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-015-9351-1

- Magnuson, K. A., Kelchen, R., Duncan, G. J., Schindler, H. S., Shager, H., & Yoshikawa, H. (2016). Do the effects of early childhood education programs differ by gender? A meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 36, 521–536. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2015.12.021

- Manning, M., Garvis, S., Fleming, C., & Wong, T. W. G. (2017). The relationship between teacher qualification and the quality of the early childhood care and learning environment: Campbell Systematic Reviews (Issue 1). https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2017.1

- Manning, M., Wong, G. T. W., Fleming, C. M., & Garvis, S. (2019). Is teacher qualification associated with the quality of the early childhood education and care environment? A meta-analytic review. Review of Educational Research, 89(3), 370–415. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319837540

- Markussen-Brown, J., Juhl, C. B., Piasta, S. B., Bleses, D., Højen, A., & Justice, L. M. (2017). The effects of language- and literacy-focused professional development on early educators and children: A best-evidence meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 38, 97–115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.07.002

- Mashburn, A. J., Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., Downer, J. T., Barbarin, O. A., Bryant, D., Burchinal, M., Early, D. M., & Howes, C. (2008). Measures of classroom quality in prekindergarten and children’s development of academic, language, and social skills. Child Development, 79(3), 732–749. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2008.01154.x

- McHugh, M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: The kappa statistic. Biochemia Medica, 22(3), 276–282. https://doi.org/10.11613/BM.2012.031

- McMullen, E., Perlman, M., Falenchuk, O., Kamkar, N., Fletcher, B., Brunsek, A., Nocita, G., & Shah, P. S. (2020). Is educators’ years of experience in early childhood education and care settings associated with child outcomes? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 171–184. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.03.004

- Melhuish, E., Ereky-Stevens, K., Petrogiannis, K., Ariescu, A., Penderi, E., Rentzou, K., Tawell, A., Slot, P., Broekhuizen, M., & Leseman, P. (2015). Review of research on impact of ECEC CARE: A review of research on the effects of Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) upon child development. http://ecec-care.org/.

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Evaluating screening approaches for hepatocellular carcinoma in a cohort of HCV related cirrhosis patients from the veteran’s affairs Health care system. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-017-0458-6

- Murad, M. H., Asi, N., Alsawas, M., & Alahdab, F. (2016). New evidence pyramid. Evidence Based Medicine, 21(4), 125–127. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebmed-2016-110401

- Murano, D., Sawyer, J. E., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2020). A meta-analytic review of preschool social and emotional learning interventions. Review of Educational Research, 90(2), 227–263. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320914743

- National Institute of Health Research. (2019). National Institutes of Health Quality assessment tools. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools.

- Navarro-Cruz, G. E., & Luschei, T. F. (2018). International evidence on effective early childhood care and education programs: A review of best practices. Global Education Review, 5(2), 8–27.

- Nelson, G., & McMaster, K. L. (2019). The effects of early numeracy interventions for students in preschool and early elementary: A meta-analysis. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(6), 1001–1022. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000334

- Nocita, G., Perlman, M., McMullen, E., Falenchuk, O., Brunsek, A., Fletcher, B., Kamkar, N., & Shah, P. S. (2020). Early childhood specialization among ECEC educators and preschool children’s outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 53, 185–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.10.006

- O’Connor, A., Nolan, A., Bergmeier, H., Hooley, M., Olsson, C., Cann, W., Williams-Smith, J., & Skouteris, H. (2017). Early childhood education and care educators supporting parent-child relationships: A systematic literature review. Early Years, 37(4), 400–422. https://doi.org/10.1080/09575146.2016.1233169

- OECD. (2006). Starting strong II: Early childhood education and care (Issue 1). OECD Publishing.

- Oh-Young, C., & Filler, J. (2015). A meta-analysis of the effects of placement on academic and social skill outcome measures of students with disabilities. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 47, 80–92. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2015.08.014

- Peden, M. E., Okely, A. D., Eady, M. J., & Jones, R. A. (2018). What is the impact of professional learning on physical activity interventions among preschool children? A systematic review. Clinical Obesity, 8(4), 285–299. https://doi.org/10.1111/cob.12253

- Peleman, B., Lazzari, A., Budginaitė, I., Siarova, H., Hauari, H., Peeters, J., & Cameron, C. (2018). Continuous professional development and ECEC quality: Findings from a European systematic literature review. European Journal of Education, 53(1), 9–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12257

- Perlman, M., Fletcher, B., Falenchuk, O., Brunsek, A., McMullen, E., & Shah, P. S. (2017). Child-Staff ratios in early childhood education and care settings and child outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE, 11(12), e0167660. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0170256.

- Perlman, M. M., Falenchuk, O., Fletcher, B., McMullen, E., Beyene, J., & Shah, P. S. (2016). A systematic review and meta-analysis of a measure of staff/child interaction quality (the classroom assessment scoring system) in early childhood education and care settings and child outcomes. PLOS ONE, 11(12), e0167660. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0167660

- Pesco, D., & Gagné, A. (2017). Scaffolding narrative skills: A meta-analysis of instruction in early childhood settings. Early Education and Development, 28(7), 773–793. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2015.1060800

- Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., Khalil, H., McInerney, P., Parker, D., & Soares, C. B. (2015). Guidance for conducting systematic scoping reviews. International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare, 13(3), 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050

- Phelps, R. P. (2019). Test frequency, stakes, and feedback in student achievement: A meta-analysis. Evaluation Review, 43(3–4), 111–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193841X19865628

- Phillips, D., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2000). From neurons to neighborhoods: The science of early childhood development. https://doi.org/10.17226/9824

- Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). Classroom assessment scoring system: Manual Pre-K. Paul. H. Brookes.

- Pianta, R. C., Downer, J., & Hamre, B. K. (2016). Quality in early education classrooms: Definitions, gaps, and systems. The Future of Children, 26(2), 119–137. https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2016.0015

- Pokorski, E. A., Barton, E. E., & Ledford, J. R. (2017). A review of the use of group contingencies in preschool settings. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 36(4), 230–241. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121416649935

- Ramey, C. T., & Ramey, S. L. (2005). Early learning and school readiness: Can early intervention make a difference? Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50(4), 471–491. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.2004.0034

- Razak, L. A., Clinton-McHarg, T., Jones, J., Yoong, S. L., Grady, A., Finch, M., Seward, K., D’Espaignet, E. T., Ronto, R., & Elton, B. (2019). Barriers to and facilitators of the implementation of environmental recommendations to encourage physical activity in center-based childcare services: A systematic review. Journal of Physical Activity and Health, 16(12), 1175–1186. https://doi.org/10.1123/jpah.2019-0050

- Rogers, S., Brown, C., & Poblete, X. (2020). A systematic review of the evidence base for professional learning in early years education (The PLEYE Review). Review of Education, 8(1), 156–188. https://doi.org/10.1002/rev3.3178

- Roorda, D. L., Jak, S., Zee, M., Oort, F. J., & Koomen, H. M. Y. (2017). Affective teacher-student relationships and students’ engagement and achievement: A meta-analytic update and test of the mediating role of engagement. School Psychology Review, 46(3), 239–261. https://doi.org/10.17105/SPR-2017-0035.V46-3

- Ross, K. M., & Joseph, L. M. (2019). Effects of word boxes on improving students’ basic literacy skills: A literature review. Preventing School Failure: Alternative Education for Children and Youth, 63(1), 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/1045988X.2018.1480006

- Schindler, H. S., Kholoptseva, J., Oh, S. S., Yoshikawa, H., Duncan, G. J., Magnuson, K. A., & Shonkoff, J. P. (2015). Maximizing the potential of early childhood education to prevent externalizing behavior problems: A meta-analysis. Journal of School Psychology, 53(3), 243–263. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2015.04.001

- See, B. H., & Gorard, S. (2015). Does intervening to enhance parental involvement in education lead to better academic results for children? An extended review. Journal of Children's Services, 10(3), 252–264. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-02-2015-0008

- Shepley, C., & Grisham-Brown, J. (2019). Multi-tiered systems of support for preschool-aged children: A review and meta-analysis. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 47, 296–308. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.01.004

- Shepley, C., Grisham-Brown, J., & Lane, J. D. (2020). Multitiered systems of support in preschool settings: A review and meta-analysis of single-case research. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 41(3), 307–320. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121419899720

- Sills, J., Rowse, G., & Emerson, L-M. (2016). The role of collaboration in the cognitive development of young children: A systematic review. Child: Care, Health and Development, 42(3), 313–324. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12330

- Sim, M., Bélanger, J., Hocking, L., Dimova, S., Iakovidou, E., Janta, B., Europe, R., & Eif, W. T. (2018). Teaching, pedagogy and practice in Early Years Childcare: An evidence review. https://www.eif.org.uk/files/pdf/teaching-pedagogy-and-practice-in-early-years-childcare-annexes.pdf.

- Sincovich, A., Harman-Smith, Y., Gregory, T., & Brinkman, S. (2020). The relationship between early childhood education and care and children’s development (AEDC Research Snapshot). Australian Government. Available at www.aedc.gov.au.

- Snell, E. K., Hindman, A. H., & Wasik, B. A. (2019). A review of research on technology-mediated language and literacy professional development models. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education, 40(3), 205–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2018.1539794

- Snyder, P. A., Rakap, S., Hemmeter, M. L., McLaughlin, T. W., Sandall, S., & McLean, M. E. (2015). Naturalistic instructional approaches in early learning. Journal of Early Intervention, 37(1), 69–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815115595461

- Soto, X., Olszewski, A., & Goldstein, H. (2019). A systematic review of phonological awareness interventions for Latino Children in early and primary grades. Journal of Early Intervention, 41(4), 340–365. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053815119856067

- Suggate, S. P. (2016). A meta-analysis of the long-term effects of phonemic awareness, phonics, fluency, and reading comprehension interventions. Journal of Learning Disabilities, 49(1), 77–96. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219414528540

- Taggart, B., Sylva, K., Melhuish, E., Sammons, P., & Siraj, I. (2015). How pre-school influences children and young people’s attainment and developmental outcomes over time: Research brief (Issue June).

- Tayler, C., Ishimine, K., Cloney, D., Cleveland, G., & Thorpe, K. (2013). The quality of early childhood education and care services in Australia. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 38(2), 13–21. https://doi.org/10.1177/183693911303800203

- Therrien, M. C. S., Light, J., & Pope, L. (2016). Systematic review of the effects of interventions to promote peer interactions for children who use aided AAC. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 32(2), 81–93. https://doi.org/10.3109/07434618.2016.1146331

- Tonge, K. L., Jones, R. A., & Okely, A. D. (2016). Correlates of children’s objectively measured physical activity and sedentary behavior in early childhood education and care services: A systematic review. Preventive Medicine, 89, 129–139. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2016.05.019

- Torii, K., Fox, S., & Cloney, D. (2017). Quality is key in early childhood education in Australia. Mitchell Institute Policy Paper No. 01/2017 (Issue 01). www.mitchellinstittue.org.au.

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

- Tupou, J., van der Meer, L., Waddington, H., & Sigafoos, J. (2019). Preschool interventions for children with autism spectrum disorder: A review of effectiveness studies. Review Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders, 6(4), 381–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40489-019-00170-1

- Ulferts, H., Wolf, K. M., & Anders, Y. (2019). Impact of process quality in early childhood education and care on academic outcomes: Longitudinal meta-analysis. Child Development, 90(5), 1474–1489. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.13296

- Urban, M., Vandenbroeck, M., van Laere, K., Lazzari, A., & Peeters, J. (2012). Towards competent systems in early childhood education and care. Implications for policy and practice. European Journal of Education, 47(4), 508–526. https://doi.org/10.2307/23357031

- Vandell, D., & Wolfe, B. (2000). Child care quality: Does it matter, and does it need to be improved? Vol. 78. University of Wisconsin–Madison, Institute for Research on Poverty.

- van de Glind, E. M. M., van Enst, W. A., van Munster, B. C., Olde Rikkert, M. G. M., Scheltens, P., Scholten, R. J. P. M., & Hooft, L. (2013). Pharmacological treatment of dementia: A scoping review of systematic reviews. Dementia and Geriatric Cognitive Disorders, 36(3–4), 211–228. https://doi.org/10.1159/000353892

- Vandenbroucke, L., Spilt, J., Verschueren, K., Piccinin, C., & Baeyens, D. (2018). The classroom as a developmental context for cognitive development: A meta-analysis on the importance of teacher-student interactions for children’s executive functions. Review of Educational Research, 88(1), 125–164. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317743200

- van Huizen, T., & Plantenga, J. (2018). Do children benefit from universal early childhood education and care? A meta-analysis of evidence from natural experiments. Economics of Education Review, 66, 206–222. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.08.001

- Verhoeven, L., Voeten, M., van Setten, E., & Segers, E. (2020). Computer-supported early literacy intervention effects in preschool and kindergarten: A meta-analysis. Educational Research Review, 30, 100325. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100325

- Vermeer, H. J., van IJzendoorn, M. H., Cárcamo, R. A., & Harrison, L. J. (2016). Quality of child care using the environment rating scales: A meta-analysis of international studies. International Journal of Early Childhood, 48(1), 33–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-015-0154-9

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

- Wang, A. H., Firmender, J. M., Power, J. R., & Byrnes, J. P. (2016). Understanding the program effectiveness of early mathematics interventions for prekindergarten and kindergarten environments: A meta-analytic review. Early Education and Development, 27(5), 692–713. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2016.1116343

- Ward, S., Bélanger, M., Donovan, D., & Carrier, N. (2015). Childcare educators’ influence on physical activity and eating behaviours of preschool children: A systematic review. Canadian Journal of Diabetes, 39, S73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcjd.2015.01.272

- Wasik, B. A., Hindman, A. H., & Snell, E. K. (2016). Book reading and vocabulary development: A systematic review. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 37, 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ecresq.2016.04.003

- Werner, C. D., Linting, M., Vermeer, H. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2016). Do intervention programs in child care promote the quality of caregiver-child interactions? A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Prevention Science, 17(2), 259–273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-015-0602-7

- Wick, K., Leeger-Aschmann, C. S., Monn, N. D., Radtke, T., Ott, L. v., Rebholz, C. E., Cruz, S., Gerber, N., Schmutz, E. A., & Puder, J. J. (2017). Interventions to promote fundamental movement skills in childcare and kindergarten: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sports Medicine, 47(10), 2045–2068. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40279-017-0723-1

- Wysłowska, O., & Slot, P. L. (2020). Structural and process quality in early childhood education and care provisions in Poland and the Netherlands: A cross-national study using cluster analysis. Early Education and Development, 31(4), 524–540. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2020.1734908