ABSTRACT

This paper proposes a novel framework for systematic reviews, the conceptual systematic review (CSR), incorporating elements of content analysis that often implicitly precede synthesising research but are rarely made explicit. We argue that a CSR has the possibility to conceptually map a tangled term, to prepare systematic reviews, to advance interdisciplinary communication, and to offer guidance in tangled fields of scientific discourse. The proposed methodological framework involves a six-stage procedure aimed at systematically unravelling tangled terms through the deductive–inductive coding of a systematically retrieved literature corpus, thereby going beyond the quantitative synthesis of research findings. We call the elements of such a framework heuristics, classifications, and systematics; they provide insight into the quality of term disentanglement and can be viewed hierarchically: heuristics do not (necessarily) satisfy any quality criteria, classifications adhere to analytical quality criteria, and systematics also meet empirical quality criteria. The six quality criteria through which the quality of a CSR can be made explicit are introduced to allow for professional scrutiny and critique. It is argued that making conceptual elements of systematic reviews explicit is especially relevant in the field of educational research. Finally, we discuss the relation of the CSR to similar methods and address weaknesses in the proposed framework.

1. Introduction

Increased political interest and intervention in research, the growth of interdisciplinary research, and an increase in the sheer amount of research at our disposal has made it more important than ever to have a clear understanding of what is meant by a certain term used by whom in what field, based on what background. This has made a fundamental goal of science – to disentangle term use – crucial. Alongside other goals, systematic reviews follow this aim by disentangling research literature (Whitacre et al., Citation2020). They not only provide insights into critical questions and multidimensional problems (Murphy et al., Citation2017) but also provide an overview of scientific literature. However, attempts to implement a systematic review to meet this broad navigational aim can expose researchers to seemingly insurmountable difficulties. The question of the maturity of the field of inquiry becomes paramount: “Research on the topic or issue that undergirds the critical question must be sufficiently mature to support an in-depth interrogation” (Alexander, Citation2020, p. 10). This claim gives rise to several questions: Why must a field be mature to be reviewed? Can (or should) interdisciplinary fields of research ever be mature? Is it not for these supposedly immature fields that navigation is especially relevant? Could one not develop a systematic review in an immature field?

As an example, one such immature field in the context of educational research is teacher education. Looking into its (relatively short) tradition, one can find a plethora of methodological frameworks, theoretical backgrounds, disciplinary proximities, forms of organisation and political claims (Cochran-Smith, Citation2004). Following Lin et al. (Citation2010, p. 296) its current status “is reminiscent of what Thomas Kuhn (Citation1970) in the The Structure of Scientific Revolutions termed a pre-science stage”. The lines of research themselves are in constant reconstruction, “[r]esearchers cannot build towers on the foundations laid by others” (Labaree, Citation1998, p. 7). Such fields of research can be viewed as “tangled” (Whitacre et al., Citation2020) in the sense of synonymous or polysemous use of terms: research in these fields runs danger of “causing significant confusion” (Larsen et al., Citation2013, p. 1522). The danger of increasing confusion becomes even more virulent when the field of research is the object of study of teacher students, who themselves are confronted with research from several disciplines and educational sciences throughout their professionalisation (Cramer & Schreiber, Citation2018).

It is for precisely such creative endeavours (Lin et al., Citation2010) in “immature” fields that we propose a rigorous methodological framework that is not too mechanical and uncreative (Cooper, Citation2017) for the navigational task at hand. We do so by focusing on the steps between the discovery of a tangled term, the positing of initial theories about its different possible meanings (pre-existing heuristics), and the final process of coding these varied meanings. We call the elements of such a framework heuristics, classifications, and systematics; they provide insight into the quality of term disentanglement and can be regarded hierarchically: heuristics do not (necessarily) satisfy any quality criteria, classifications satisfy analytical quality criteria, and systematics satisfy analytical and empirical quality criteria and describe a valid systematic of term use. We propose that the methodological reflection of such a framework for systematic reviews that incorporates elements of content analysis can help researchers explain how they reach their conclusions, thus opening their research to professional and interdisciplinary reflection, scrutiny, and critique (Lin et al., Citation2010). Such conceptual systematic reviews are not only at the heart of looking “deeper into the edifice of educational research to the bricks and mortar with which that structure is built” (Murphy et al., Citation2017, p. 3), they also play an important role in teacher education by helping student teachers in proposing overviews of the field of educational research that otherwise runs danger of being perceived as contingent, random, or irrelevant. We call the method entrusted with developing such systematics of term use a conceptual systematic review (CSR).

A CSR builds upon the (highly flexible) research methodology of content analysis (Krippendorff, Citation2019; White & Marsh, Citation2006) that arose in the context of communications research in the early 1950s (Berelson, Citation1952) and has been defined as a “systematic, rigorous approach to analyzing documents obtained or generated in the course of research” (White & Marsh, Citation2006, p. 41). While most approaches to content analysis tend to follow either a quantitative or qualitative path, a CSR is a hybrid approach that attempts to mitigate the difficulties of purist approaches to content analysis (Kracauer, Citation1952) by focusing on transparency and rigor (Alexander, Citation2020; Torgerson et al., Citation2017). To facilitate achieving these goals, a CSR embeds a hybrid approach to content analysis in the larger framework of a systematic review. When striving for untangled and clearly defined terms in educational research, the combination of these two methods utilises their respective advantages and allows their shortcomings to be compensated by the other method (Khirfan et al., Citation2020). While a systematic literature review alone produces an abundance of material without a unified interpretation procedure or clearly defined method to handle tangled terms, content analysis methodology can give insight into how this material is interpreted but often does not focus on reproducibility or transparency as well as rigour criteria of corpus selection. A CSR is therefore a method that combines steps and quality criteria from systematic literature review (exhaustive, transparent, and rigorous selection and analysis of the literature) and content analysis (deductive and inductive coding frame development).

An interdisciplinary example of a tangled term for which a CSR is suitable is “digitalization.” This word evokes very different meanings, not only between everyday usage and scientific discourse, but also depending on the disciplinary field and paradigmatic background in which it is scientifically used. In the context of our own scholarly work in the field of education, more specifically in research on the teaching profession, what is meant by “digitalization” remains fuzzy. It can be a procedure to digitalise teaching materials, a didactic method for teaching in the classroom, an intrusive strategy to overhaul the education system, or even a term to describe the transformation of technology-human interaction. Consequently, carrying out a systematic review on this subject that could provide an overview of the very extensive research results risks entangling different denotations, let alone connotations, of the term. Therefore, we use the term “digitalization” in teacher education as an example that is currently undergoing a CSR in the German-speaking context of research on teachers and is now to be worked on in the international discourse (Binder & Cramer, Citation2020). We use this example and the findings stemming from our exploratory research to elaborate the goals and strengths of a CSR in a comprehensible way and to guide the reader through the methodological framework we propose.

The goals of a CSR can be summarised as follows:

Systematic: To conceptually map a tangled term without relying solely on stakeholder, narrative, or expert opinions or reviews by instead mapping it transparently and empirically from the bottom up. CSRs, in sharing this aim with scoping reviews, are standalone projects that can be devised in their own right (Mays et al., Citation2001). A CSR of “digitalization” in educational research can clarify the tangled term’s different semantic connotations.

Preliminary: To determine disentangled terms that can then be used to conduct a systematic review. A CSR can serve as a preliminary stage before a full systematic review, which focuses on research findings, ending the reciprocity of deductive and inductive elements of content analysis in favour of a deductive approach to the meta-synthesis of research findings (Schreier, Citation2012). For example, before the effects of different digitalisation concepts can be examined, what is meant by “digitalization” must be clarified so that the relevant selection criteria for a systematic review can be applied appropriately.

Interdisciplinary: To identify shared or distinctive dimensions of term use across different fields and backgrounds to allow a better understanding in interdisciplinary research. The example field of research on teachers is comprised of a plethora of methodological frameworks, theoretical backgrounds, and disciplinary proximities, as is true of many fields. This may not be a problem per se, but it can become an issue when these different backgrounds enter interdisciplinary communication and research. Research pertaining to digitalisation in teacher education is one such interdisciplinary research field that runs the risk of tangling.

Didactic: To make tangled fields of scientific discourse accessible. As opposed to a scoping review that focuses on research findings and is aimed at policymakers, practitioners, and consumers (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005), a CSR can offer insights into term use in a broad sense. This can also support the development of professionality in researchers in the sense of being able to differentiate term use in different fields and backgrounds and the pragmatics of these different term uses in a meta-reflexive manner (Alexander, Citation2017). Such an analytical approach to term use distinctions is a valuable competence when reading systematic reviews, as some have not employed a process of term disentanglement, leading to unclear term use in the resulting meta-analysis. Hattie’s (meta)synthesis Visible Learning (Hattie, Citation2009), where the categories of “teachers” and “teaching” are distinguished without explicit justification, is one example of this problem (Snook et al., Citation2009).

These four goals are compatible with one another; they do not describe different approaches or imply different methodological steps but focus on different ways of looking at and presenting the results of a given CSR.

2. Proposing a methodological framework: the six stages of a CSR

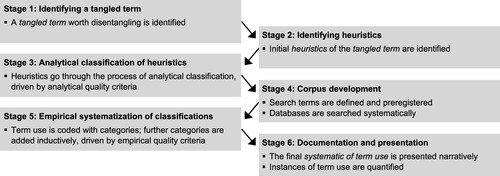

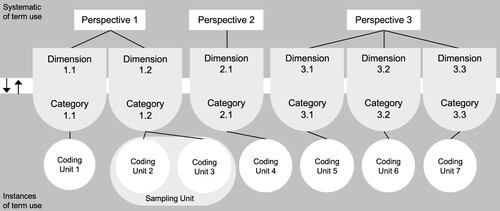

In the following, we propose a six-stage methodological framework of a CSR (see ) and corresponding quality criteria to be considered at various points in the research process. We offer procedural recommendations, identify difficulties, outline best practice procedures, and provide each stage with an appropriate example that is adapted to fit and illustrate the methodological framework introduced.

2.1. Stage 1: identifying a tangled term

As with any review, the starting point of a CSR is a relevant research question worth answering – in this case, a term worth disentangling. Referring to the goals of a CSR, a term is tangled if no (or hardly any) empirically founded systematic interest has been taken in it, if the costs of conducting a systematic review cannot be estimated due to unforeseeable difficulties in search term acquisition or the breadth of the relevant literature, if background and field-specific term uses cannot be identified, and if the term leads to increased confusion because it is used contingently. If these attributes apply to the term in question, it can safely be classified as tangled. How, then, to unravel the term? How can the different types of term use be mapped and quantized? A CSR offers a systematic approach to help answer these questions, which arise from tangled term use.

Regarding our example, the tangling of the term “digitalization” is identified by contrasting the high expectations of digitalisation with a simultaneous lack of research and empirical base. An indication of tangling appears in the very few systematic reviews pertaining to the strengths of digitalisation in education. For instance, a systematic review regarding “digital reading” as one facet of digitalisation points out that most research lacks a clear definition of the term “digital reading,” leading to this conclusion: “we were unpleasantly surprised by the paucity of either explicit or implicit definitions we could document for … digital reading” (Singer & Alexander, Citation2017, p. 1016). Such findings point to the necessity of a clear definition when engaging in research regarding digitalisation. The interdisciplinary findings referring to “digitalization” may barely be related to one another, as “digitalization” is a tangled term in the literature and is thus a legitimate candidate for a CSR.

2.2. Stage 2: identifying heuristics

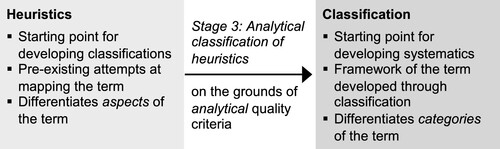

Now that a tangled term has been identified, we need to answer the question of how to go about unravelling it, which requires a way of coding the different instances of term use, or coding frame. While we agree that inductive strategies of developing a coding frame can ease the coding process and increase reliability (Schreier, Citation2012), we hold that “conceptualizations that have proven successful elsewhere have a better chance of contributing to existing knowledge” (Krippendorff, Citation2019, p. 394). These conceptualizations are nothing more than theories about and experiences with the context of the tangled term (Krippendorff, Citation2019). We call these (often empirically and analytically unsubstantiated) pre-existing frameworks heuristics; in other contexts, they are also called classifications or taxonomies (Krippendorff, Citation2019). These heuristics can come from a number of sources: “from a theory, from previous research, from everyday experience, or from logic” (Schreier, Citation2012, p. 85). They serve as an (implicit or explicit) attempt to map a tangled term and as a theoretical point of reference for the deductive development of our coding frame (Krippendorff, Citation2019; Schreier, Citation2012).

These pre-existing heuristics of the tangled term are identified in the relevant field of research, where they present themselves as explicit and/or implicit attempts at mapping the term in question. What distinguishes heuristics from term use systematics (the final product of a CSR) is that heuristics do not necessarily adhere to all the quality criteria of a CSR; indeed, they do not necessarily adhere to any of the quality criteria associated with systematic reviews. They are seldom methodical and transparent and, of even greater concern, they are usually not (systematically) empirically grounded. In cases where no explicit heuristics can be identified, the researcher has two options: either follow a purely inductive path of coding frame development, which risks missing the opportunities that pre-existing frameworks offer, or develop a heuristic through a narrative review of the implicit heuristics found in the relevant disciplinary field.

To our knowledge, no such explicit heuristic of “digitalization” in the field of teacher education can be found. In this case, the researcher extracts implicit heuristics from the chosen disciplinary field and makes these explicit. Using the example of the term “digitalization” (Decuypere, Citation2018; Floridi, Citation2014; Hoogerheide et al., Citation2019), heuristics were developed and adapted to be used in the field of teacher education, where term use was subsequently found to differentiate between certain goals and processes of digitalisation (Binder & Cramer, Citation2020).

2.3. Stage 3: analytical classification of heuristics

Now that explicit heuristics have been identified or developed from implicit theories, they need to be worked into a coding frame so they can be used to reliably code instances of term use found in the literature (see ). To assist in this deductive integration of heuristics, or, in cases where no heuristics were found, to support the development of a first coding frame, we propose analytical quality criteria that are central to the reliability of the coding (White & Marsh, Citation2006). While reliable coding does not ensure validity, its absence renders data invalid (Lombard et al., Citation2005).

Quality criterion 1: Definiteness requires a clear definition of both perspectives and categories (see ). It is a requirement for reliable and objective coding (Kolbe & Burnett, Citation1991), is broadly endorsed in content-analysis research, and ensures that aspects of a term can be made explicit and are not simply arbitrarily lumped together. To define the perspective of a heuristic, one must ask, “Which perspective(s) of the tangled term does this heuristic focus on?” This can be anything from the institutional location assigned to the term or the methods used when research is conducted regarding the term to certain paradigms selected when describing or defining the term. To define the categories of a heuristic, one must ask, “What categories does this perspective focus on?” To achieve definiteness in the example of digitalisation would mean developing clear definitions of perspectives and categories of term use as the starting point for a CSR. The use of the term “digitalization” in teacher education can allude to the goals or processes of digitalisation; these mark different perspectives on the term (see ).

Table 1. Achieving definiteness of categories in digitalisation (Binder & Cramer, Citation2020).

Quality criterion 2: Selectivity means that perspectives have no intersections: a coding unit (an empirical instance of term use) must be assignable to exactly one perspective. Say a heuristic focuses on the methods associated with a tangled term and on the authors cited when defining that term. These two perspectives are analytically distinct and can be combined in any way. The criterion of selectivity requires that these two foci be split into distinct perspectives, with one focusing only on methods and the other solely on authors. To test the selectivity of the perspectives means to ask the question, “Are the categories of my classifications specific to their perspectives?” If they are not, the classification must be reworked. If they are, a coding unit will always be assignable to exactly one perspective. According to the example, we must ask ourselves if the categories provision, results, and interaction are specific to the perspective of the goals of digitalisation, or if they might also fit the perspective of the process of digitalisiation. To attain selectivity, we suggest entering a comparative reflection (Walker & Avant, Citation2019), ideally with co-researchers, to see whether one’s intuition regarding perspectives holds up. Later difficulties in coding instances of term use and low inter-coder agreement (see stage 5) can indicate that selectivity was not sufficiently attained.

Quality criterion 3: Independence means that categories have no intersections: categories cannot be in a hierarchical subset relationship. This means that no coding unit can belong to two categories. To test the independence of the categories means asking the question, “Can a coding unit belong to more than one category?” If this is possible, the classification must be reworked. If not, a coding unit will always be assignable to exactly one category. Returning to the example, the perspective of the process of digitalisation cannot contain both the independent category “control” and the further independent category “change,” because a coding unit belonging to the first category would always also belong to the second, as every instance of “controlled change through digitalization” would also be coded as an instance of “change through digitalization.” Categories can be in a subset relationship with a further category (e.g. the category control could be further split into democratic and hierarchical control), although these should be clearly introduced as dependent sub-categories and, again, must be independent of each other.

2.4. Stage 4: corpus development

Now that we have developed an analytically sound classification that we can use as a coding frame, we can start extracting empirical instances of term use (coding units). To find these, we first must decide where (in which field) we want to look for them and, starting from there, retrieve literature (sampling units). When developing a corpus for a CSR, formulating appropriate search parameters is especially difficult. As tangled terms imply the polysemous use of a term, the term itself appears to be the only appropriate delimitation. Searching databases for texts that include a (tangled) term in their titles or abstracts is a common strategy in conceptual forms of systematic reviews (Gusenbauer & Haddaway, Citation2020a; Murphy & Alexander, Citation2000; Whitacre et al., Citation2020). A central delimitation of literature acquisition is the disciplinary field selected, as the interdisciplinary goal of a CSR points to the relevance of disentangling terms in and for certain disciplines. Delimiting the scope of a review in terms of language, geographic area, database, or time frame needs to be decided for each review separately and cannot be suggested generally (Reed & Baxter, Citation2009; White, Citation2009). When undertaking a CSR for a relatively current topic like digitalisation, it may not make sense to limit the time frame.

Due to the CSR’s goal of disentangling term use in a broad sense, we suggest not limiting the literature corpus to peer-reviewed journal publications but deliberately including additional types of literature, such as conference papers (Rothstein & Hopewell, Citation2009). Systematically excluding literature that does not adhere to the highest degree of scientific quality, as suggested in the “Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P)” (Nightingale, Citation2009) and many other guidelines (Thomas et al., Citation2011), might exclude precisely those publications that play a central role in tangling the term in the first place. Exclusion based on quality criteria would therefore remove certain term use dimensions from the final systematic of term use, undermining the systematic goal of disentangling term use in the broadest possible sense.

Once it is determined which texts will and will not be included in the literature corpus, the question of how to extract empirical instances of term use (coding units) comes to the fore: How are the data to be unitized? As the literature corpus of a CSR can be very large due to its relatively wide search criteria, we suggest invoking an element of automated term recognition (Moher, Shamseer, et al., Citation2015) to expedite this process of unitising (Krippendorff, Citation2019): lexical scanning of the literature for the tangled term, as every instance of the tangled term is a possible coding unit (Krippendorff, Citation2019). Lexical scanning can be undertaken in a wide range of computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software (CAQDAS). We suggest using the lexical search function of the CAQDAS selected to search for the tangled term and possible derivations. As not all texts are available in searchable text formats (older articles often must be scanned manually), image-to-text conversion will have to be implemented to make lexical scanning possible. These now automatically generated coding units (syntactic selection) are then examined to see if they can be interpreted as definitions or delimitations of the tangled term (semantic selection) and if they can be interpreted through the chosen perspectives. This procedure should be iterative, as an increasingly rich understanding of the term can lead to doubling back and examining possible coding units as many times as needed. Because coding units pertain only to the tangled term and its immediate context, they can be small, and context units may have to be examined to reliably code a given coding unit (Krippendorff, Citation2019). These context units are usually defined a priori as the abstract, the introduction, or corresponding parts of an article that focus on the introduction or definition of the term of interest. The selection of relevant context units should also be made transparent as they are central to testing interrater reliability.

In systematic research, it is essential to meticulously document the decision process of literature selection (e.g. adding a flowchart, selection and exclusion criteria, and full document lists), to make the rationale behind these decisions explicit, and to discuss what effects different parameters may have on the findings (Alexander, Citation2020). Relying on an iterative team approach to corpus development and making its procedure explicit can help reduce the ambiguity of broad research questions (Levac et al., Citation2010). Increasing rigor and reliability (and thus the criterion of empirical viability) in these steps could also imply reporting intercoder agreement through Krippendorff’s alpha for data charting, from database, timeframe, language, and field selection through the selection of texts (articles or other kinds of literature) to the selection of coding units (Krippendorff, Citation2019). Building on the understanding of corpus development as a systematic and iterative team effort (Levac et al., Citation2010), we see added value in making the why of corpus development explicit through a narrative record of the decision-making process (Cooper et al., Citation2018). In presenting both a flowchart and a narrative record of the search strategy, stage 4 of a CSR can be made maximally transparent.

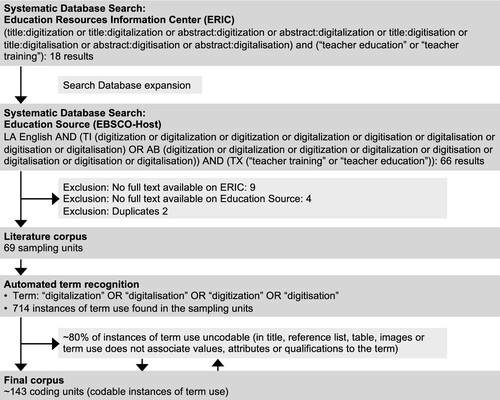

Returning to the digitalisation example, data collection is presented in a flowchart that documents each step of iteration and inclusion or exclusion (see ). After a first exploration of the term “digitalization”, the often synonymously used term “digitization” was added to the Boolean search phrase, as were appropriate alternative spellings. First, the search phrase was used on the ERIC database, as it is relevant for the selected field of teacher education. ERIC returned too few results to allow a CSR, forcing us to expand our database search. For demonstrating such a systematic search in this methodological context, we only included results that allowed rapid retrieval of a paper’s full text. Similarly, we relied on our experiences from our own exploratory CSRs to estimate the number of coding units to be found in relation to the frequency of term use (semantic selection). Usually, only around 20% of term use instances represent a coding unit. Stage 4 of a CSR (text retrieval and unitising) is the most tedious stage and accounts for most of the time invested.

Figure 3. CSR flowchart for a corpus retrieved through a systematic search of the online databases (Craven & Levay, Citation2011) ERIC (Education Resource Information Center) and Education Source (EBSCO-Host) with “digitalization” as the tangled term.

2.5. Stage 5: empirical systematization of classifications

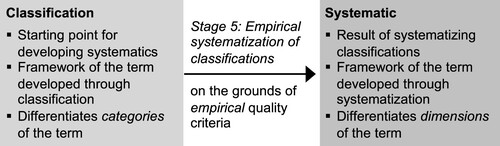

Now that we have a corpus of coding units and an analytically developed classification of the different term uses, the empirical systematization of the classification (see ) can begin. While the heuristics and classification in stages 2 and 3 were developed following deductive strategies, stage 5 involves inductive strategies, thus incorporation characteristics of both quantitative and qualitative content analysis (White & Marsh, Citation2006). The most prominent strategies of inductive coding frame development are as follows: summarising, subsumption, contrasting, and grounded theory (Schreier, Citation2012). If this step is skipped, the CSR would not fulfil its goal, as it would rely only on pre-existing heuristics. By using the analytically developed coding frame to analyse the literature, further term uses can be identified and used to inductively elaborate the term use systematic. It is at this point that a CSR leaves the positivist research tradition and enters a humanist – or in the broadest sense a hermeneutical – tradition “to capture the meanings, emphasis, and themes of messages and to understand the organisation and process of how they are presented” (Altheide, Citation1996, p. 33).

Only after the different forms of use are established can a researcher begin to quantify term use frequency and compare term use backgrounds and fields. The background of a term use can allude to the philosophical, theoretical, paradigmatic, or empirical underpinning of its use, while the field of a term use can refer to the disciplines, regions, or scientific communities in which a specific use is prominent. While discovering the background of a term use is both a central goal and a major interpretive challenge of a CSR, deciding on the fields to include in literature selection is answered beforehand (see stage 4).

In the terms of a CSR, the classifications developed in stage 3 are now subjected to inductive expansion (generality) and empirical validation (operationalizability) by using them to code the instances of term use found in the literature as reliably as possible (reliability). These three quality criteria are elaborated below.

Quality criterion 4: Generality means that each coding unit must be assigned to one category in one perspective. If a coding unit cannot be coded, a suitable category must be added inductively, alluding to the inductive aspect (Schreier, Citation2012) of a CSR. Also called exhaustiveness (Krippendorff, Citation2019), this criterion refers to the ability of a systematic of term use to represent all coding units without exception. To test the generality of a term use systematic, one must ask, “Can all coding units be coded using my current coding frame?” If they cannot, the coding frame must be expanded inductively. Returning to the example of digitalisation, we may find uses of “digitalization” that allude to performance enhancement through biohacking or uses that focus on sociological aspects of mediatisation. These uses of the term “digitalization” would have to be included in the coding frame to achieve generality.

Quality criterion 5: Operationalizability means that a coding unit can be clearly assigned to a perspective and a category based on the coding guidelines. This is ensured by clear coding guidelines (Krippendorff, Citation2019; Schreier, Citation2012). These guidelines contain the following: the names of the perspectives and their categories, definitions of the perspectives and their categories, typical examples of the categories in the literature, and, possibly, further operationalizations or notes. To test the operationalizability of a term use systematic, one must ask, “Can coding units be clearly coded using my current coding guidelines?” If they cannot, the coding guidelines must be further developed. For our digitalisation example, coding guidelines that give an account of operationalizability may take the form detailed in .

Table 2. Example of coding guidelines.

Quality criterion 6: Reliability means that a CSR should adhere to the scientific criteria of any systematic review: “methodical, logical, and transparent” (Alexander, Citation2020). As a CSR incorporates elements of quantitative and qualitative research paradigms, the criterion of reliability has two dimensions. Quantitative reliability means that all or a sample of the coding units should be coded by two or more coders (Krippendorff, Citation2019) in a random order to avoid primacy-recency effects until a sufficient level of intercoder agreement is reached. Krippendorff’s alpha (Hayes & Krippendorff, Citation2007) should be reported as the coefficient of intercoder agreement, as it can deal with a wide range of given scenarios – such as more than two coders, different interval scales, or missing data – and it provides a scaled value between 0 (complete absence of reliability) and 1 (perfect reliability). These advantages of this robust measure led us to propose Krippendorff’s alpha as a superior measure for reporting the reliability of coding. It goes far beyond simply giving percentages of agreement that would be confounded with several types of biases. Krippendorff’s alpha should be reported specifically for each perspective selected, as perspectives can vary in the number of categories and are independent of one another; hence, they could be understood as independent (sub-)systematics of term use. To test the reliability of a term use systematic in a quantitative sense means to ask, for example, “Is α > .667? Is the probability q of the failure to exceed this smallest acceptable reliability < .05?” If it is not, benchmarks can be adjusted to better reflect the validity requirements imposed on the research results (Krippendorff, Citation2019) or the term use systematic has to be reworked, ideally in the mode of a reflexive dialogue between coders.

This leads to the second dimension of reliability in a CSR. Qualitative reliability means researchers should offer insights into the iterative, creative, and often interpersonal processes of defining the perspective of a given heuristic, developing relevant categories inductively, extracting categories from the suggested heuristics, and the reflexive dialogue between coders that precedes the measurement of intercoder agreement. The development of a systematic of term use is usually not as straightforward as our example implies; it is not a business of certainty but has elements of creativity and thus requires inference. It can be seen as “the confluence of art and science” (Alexander, Citation2020, p. 8). To test the reliability of a term use systematic in a qualitative sense means to ask, “Have I sufficiently engaged in a reflexive dialogue with my fellow researchers?” Of course, researchers should always be asking themselves this question and we can provide no bright lines that indicate when a “sufficient level of reflection” has been reached; a sufficient Krippendorff’s alpha value can only be a starting point. In the digitalisation example, we need to ask one or more co-researchers to code instances of term use according to the developed systematic of term use. The results of coding are entered into a suitable software package (the syntax for calculating Krippendorff’s alpha is readily available (Hayes & Krippendorff, Citation2007)) and the value obtained is interpreted based on the reliability needs of our research focus. If the resulting value is unsatisfactory, a reflexive dialogue between the coders is initiated. This process of coding and reflection is iteratively resumed until a satisfactory level of agreement (both empirically and intuitively) is reached. This allows an empirically based proof and optimisation of the coding guidelines.

2.6. Stage 6: documentation and presentation

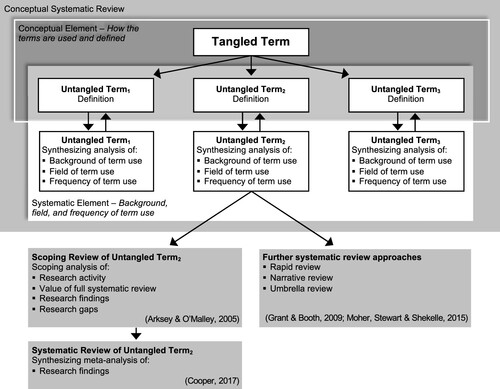

Now that we have developed a systematic of term use, we can present our results. Because a CSR involves qualitative and quantitative research methods, it always has two outcomes. The first is the qualitative systematization of the tangled term – the systematic of term use. This answers the first question of a CSR: “How are terms used and defined?” The second outcome is the quantitative presentation of the background, field, and frequency of term use. This answers the second question of a CSR: “In which background and/or in which field is which form of term use employed and how often?” and and show the presentation of the different outcomes of a CSR on a general level to allow for adaptation in different disciplines and contexts.

Figure 5. Structure of a systematic of term use and its reciprocal relation to instances of term use.

Figure 6. Conceptual and systematic elements of a CSR and possible further steps of systematic analysis.

Table 3. Presenting quantitative results of a systematic of term use.

The presentation of the systematic of term use (see ) as continuous text or text matrices (Schreier, Citation2012) should contain the chosen perspectives on the tangled term and the analytically and empirically developed dimensions of the tangled term regarding these perspectives. Krippendorff’s alpha should be presented for each perspective, and every dimension should be presented with a clear definition and quote (coding unit) and/or example (e.g. peer-reviewed journal article). Referring to the digitalisation example, the systematic of term use gives clear definitions of the goals and process perspectives and the provision, results, interaction, governance, and transformation dimensions.

The presentation of the background, field, and frequency of use (see ) depends on the specific tangled term and the perspectives chosen. Here, one can focus on showing the development of use over time or the frequency of different term uses in different backgrounds or fields. One could compare languages, different forms of literature (e.g. peer-reviewed articles vs. conference proceedings), different sub-disciplines involved in teacher education (e.g. psychology vs. sociology), or different lexical search terms (“digitalization” vs. “digitization”). As the structure presented in shows, a quantitative presentation of term use regarding “digitalization” could take the following form. In field 1 (teacher education) and background 1 (peer reviewed articles), considering perspective 1 (goals), dimension 1.1 (provision) of the term “digitalization” was found to have 46 uses (48.42%), dimension 1.2 (results) to have 32 uses (33.68%), and dimension 1.3 (interaction) to have 17 uses (17.89%).

By presenting both outcomes, the goals of a CSR are achieved: first and most importantly, the term “digitalization” in teacher education is now disentangled (systematic goal). This allows the term use systematic presented to function as a possible starting point for quantitatively oriented systematic reviews, as visualised in a general manner in , which can be adopted to different backgrounds and fields of research, as the various uses of the term “digitalization” are now sufficiently differentiated (preliminary goal). Definitions shared across different backgrounds and fields of term use can be explored to provide a better understanding in interdisciplinary fields (interdisciplinary goal). Finally, the tangled term “digitalization” is now more accessible, as it is no longer an umbrella term with diffuse boundaries. Different term uses are now clear, allowing researchers to reflect different uses of the term. This supports the development of professionality in researchers by helping them understand the background and possible pragmatics of different term uses in a meta-reflexive manner (Alexander, Citation2017) (didactic goal).

3. Discussion and conclusion

Following Arksey and O'Malley’s (Citation2005) seminal work regarding scoping reviews and further advances in this field by Levac et al. (Citation2010), we have proposed a novel method aimed at making the content-analytical steps taken in conceptual forms of systematic reviews transparent. The proposed methodological framework involves six stages, advancing from heuristics developed using narrative and expert reviews through analytically sound classifications to analytically and empirically founded systematics of term use. To further ensure the necessary rigor implied by undertaking such an endeavour systemically, six quality criteria were introduced: definiteness, selectivity, and independence (analytical quality criteria); and generality, operationalizability, and reliability (empirical quality criteria). By proposing a methodological framework for a CSR, we intend to further advance methodological reflection in the field of systematic reviews that incorporate elements of content analysis to facilitate navigational aims. The result of a CSR can therefore be seen as a starting point for further research approaches, like scoping reviews (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005), systematic reviews (Cooper, Citation2017), and/or other techniques that are related to systematic reviews (Grant & Booth, Citation2009; Moher, Stewart, et al., Citation2015). A CSR is not an alternative to these methods; in many cases, a CSR serves as a preliminary stage.

The proposed framework makes the content-analytical steps taken in conceptual forms of systematic reviews transparent by providing insights into the stages and quality criteria behind the complex and creative task of systematic reviews that incorporate elements of content analysis and are often shrouded behind narrative descriptions of a process reaching a “saturation point” (Whitacre et al., Citation2020, p. 100) or coding systems that “appeared stable” (Amundsen & Wilson, Citation2012, p. 97) in systematic reviews. In this sense, we believe that adhering to the framework of a CSR can be a step towards explicit, transparent, and replicable results, while still allowing enough art to allow for the more creative elements of content analysis. In addition to these methodological strengths, a CSR meets a wide range of goals. The resulting systematic of term use is the result of a bottom-up procedure and sheds light on fields of research that are prone to external influence. A CSR expounds term use dimensions and thereby helps researchers grasp these different dimensions of tangled terms in a systematic way, enabling a coherent understanding of tangled terms (systematic goal). In so doing, a CSR can aid the selection of specific term dimensions for further modes of systematic reviews (preliminary goal). It can support the identification of disciplinary individuality or overlap in term use across backgrounds or fields of use, advancing interdisciplinary discourse (interdisciplinary goal). Finally, a CSR can help researchers develop analytical rigor in the analysis of term use, as is found in the scientific field and beyond (didactic goal).

Next to a clear methodological framework, a further marker for rigor in research currently under discussion is preregistration. Although preregistration is primarily connected to testing hypotheses in quantitative research with a focus on prediction (Nosek et al., Citation2018), a recent debate pertains to its value for qualitative, postdictive research that is focused on generating hypotheses (Haven et al., Citation2020; Haven & Van Grootel, Citation2019; Kern & Gleditsch, Citation2017; Miguel et al., Citation2014; Piñeiro & Rosenblatt, Citation2016). We also hold that the fundamental idea of preregistration, namely “putting the study design and plan on an open platform for the (scientific) community to scrutinize” (Haven & Van Grootel, Citation2019, p. 236), can also apply to postdictive research. Hence, we suggest preregistering every CSR. While standard preregistration forms facilitate hypothesis-testing research, we hope that suggestions made to adapt preregistration forms to facilitate postdictive research (Haven & Van Grootel, Citation2019) more easily are implemented in the future. Regarding Open Science Framework (OSF), “design plans” and “analysis plans” can be uploaded in an open format as living documents (Haven & Van Grootel, Citation2019), allowing researchers to preregister systematic search criteria (stage 4) before corpus development (Kern & Gleditsch, Citation2017) and coding systems before testing reliability (stage 5). This allows other researchers to track the assumptions and development of a study. This can further advance the transparency and reproducibility of a CSR in two ways. First, preregistering systematic search criteria allows the authors of a CSR and other researchers to reflect on and discuss the validity of search term criteria in respect to (expected) term use, thus minimising selection bias (Gusenbauer & Haddaway, Citation2020b). Second, preregistering the procedure and conditions of the analysis of reliability through Krippendorff’s alpha can help reduce degrees of freedom by formulating a criterion; for example, that the reliability of coding is expected to αmin > 0.667 (95% CI).

We propose the CSR method in light of the same difficulties for which the method of concept analysis was proposed (Wilson, Citation1963) and later adapted in the nursing sciences (Morse, Citation1995; Rodgers & Knafl, Citation2000): “Many concepts that are used in critical care nursing are vague or ambiguous” (Rodgers, Citation1991, p. 33). In denying essentialist approaches and seeing words as a “ubiquitous form for the expression of concepts” (Rodgers, Citation2000, p. 79), a CSR and evolutionary approaches to concept analysis (Rodgers, Citation1989) share philosophical underpinnings. The framework of both methods is similar, a “specific concept which is described by an associated term” (Rodgers, Citation1991, p. 29) is identified, literature regarding this term is selected, and definitions of the term are categorised. However, while concept analysis shies away from “umbrella terms that are so broad that they may encompass several meanings and confuse the analysis” (Walker & Avant, Citation2019, p. 171), a CSR focuses them. Umbrella terms are precisely the “tangled terms” that a CSR has been proposed to tackle.

The goals of a CSR bear a striking similarity to what is cited as an alternative to systematic reviews in research synthesis: the conceptual review (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2006). The conceptual review (also called conceptual synthesis) is a review that aims to synthesise areas of conceptual knowledge, thereby making these fields more accessible (Petticrew & Roberts, Citation2006). The goals of such an approach to research synthesis are to provide orientation in these areas of conceptual knowledge by mapping the main ideas, models, and debates (Nutley et al., Citation2002). We argue that, to a certain degree, a conceptual review – although it is often described as an alternative to a systematic review – is in fact a prerequisite of every systematic review. In most cases, the field of inquiry is simply so mature that reliable conceptual mapping is already given (Alexander, Citation2020). However, if a systematic review is to be carried out in a field of increased confusion, researchers are entrusted with the task of developing a reliable map of term use before they can begin with the empirical elements of a systematic review. It is for reviews under such conditions that we suggest a CSR.

When a researcher is confronted with a tangled field of research, he or she might be inclined to undertake a scoping review, which is sometimes called a scoping study or systematic mapping (Pham et al., Citation2014). Generally, four central reasons are put forth for undertaking scoping reviews (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005). They aim to examine the nature and extent of research in an area, determine the promise of undertaking a systematic review, summarise any research findings, and identify research gaps in the existing literature. As Arksey and O’Malley go on to acknowledge, a scoping review focuses on the research evidence of a field, its nature, and any gaps therein. A CSR focuses on term use itself and on gaps in term use rather than gaps in the scholarly literature (Arksey & O'Malley, Citation2005). While calls to include conceptual mapping (Anderson et al., Citation2008; Peters et al., Citation2015), reconnaissance (Davis et al., Citation2009), and clarification of key concepts and definitions (Munn et al., Citation2018) in systematic review research have been made, no consistent methodological frameworks (Chrastina, Citation2020) that focus on these conceptual goals have yet been proposed. Therefore, we provide and discuss a new methodological framework. We have implemented the proposed framework several times ourselves and have presented recommendations that we feel can help researchers interested in developing systematic reviews that focus on term use as opposed to the synthesis of research findings.

Of course, a CSR also has weaknesses. In our experience, a CSR is best implemented to analyse fields of polysemous term use. While synonymous term use can be incorporated (as in the example of “digitalization” and “digitization”), it implies an iterative expansion that aims at comprehensive inclusion of the tangled term beyond polysemous use (Thompson et al., Citation2014). It can further be asked whether a (systematic) justification of the selection of perspectives in Stage 3 is possible. At times, the procedure at this point may remind one of the art or bricolage described in qualitative research practice (Hammersley, Citation2004). In principle, the variety of perspectives that can be adopted when considering any subject is theoretically unlimited. The selection of specific perspectives is therefore unavoidable and necessary, but subject to justification. A challenge of any CSR that can be further addressed in the future development of the methodology in the proposed framework is the question of how to systematically operationalise what is to be understood as a case of term use (how exactly can a unit be defined and distinguished from surrounding text?). Defining what entails term use is crucial in the process of unitising in stage 4 of a CSR. Structuralist approaches to language analysis (Firth, Citation1957) could be a starting point for unitising in future research. A methodological difficulty of the CSR framework could also lie in the recommendation to include grey literature. This could lead to a dilution of meaningful units and render the result of a CSR too broad to interpret. A solution to this problem could then be to report results specifically for each (sub-)corpus. While we hope to have pointed out the benefits of preregistering certain elements of a CSR, we still think there is a long way to go until there are common standards for preregistering these forms of systematic reviews, and we see the need for continued efforts to advance these instruments of systematization.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alexander, P. A. (2017). Reflection and reflexivity in practice versus in theory: Challenges of conceptualization, complexity, and competence. Educational Psychologist, 52(4), 307–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2017.1350181

- Alexander, P. A. (2020). Methodological guidance paper: The art and science of quality systematic reviews. Review of Educational Research, 90(1), 6–23. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319854352

- Altheide, D. L. (1996). Qualitative media analysis. Sage. http://www.gbv.de/dms/hbz/toc/ht007328331.pdf

- Amundsen, C., & Wilson, M. (2012). Are we asking the right questions?: A conceptual review of the educational development literature in higher education. Review of Educational Research, 82(1), 90–126. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654312438409

- Anderson, S., Allen, P., Peckham, S., & Goodwin, N. (2008). Asking the right questions: Scoping studies in the commissioning of research on the organisation and delivery of health services. Health Research Policy and Systems / Biomed Central, 6(7), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4505-6-7

- Arksey, H., & O'Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616

- Berelson, B. (1952). Content analysis in communications research. Free Press.

- Binder, K., & Cramer, C. (2020). Digitalisierung im Lehrer*innenberuf. Heuristik der Bestimmung von Begriff und Gegenstand. In K. Kaspar, M. Becker-Mrotzek, S. Hofhues, J. König, & D. Schmeinck (Eds.), Bildung, Schule, Digitalisierung (pp. 401–407). Waxmann.

- Buhl, M., & Skov, K. (2020). Techart learning practices for 1st to 3rd grade in Danish schools. In C. Busch, M. Steinicke, & T. Wendler (Eds.), 19th European Conference on e-Learning (ECEL 2020) (pp. 73–79). Academic Conferences and Publishing International. https://doi.org/10.34190/EEL.20.047

- Chrastina, J. (2020). Title analysis of (systematic) scoping review studies: Chaos or consistency? Nursing & Health Sciences, 22(3), 557–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/nhs.12694

- Cochran-Smith, M. (2004). The problem of teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 55(4), 295–299. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487104268057

- Cooper, C., Dawson, S., Peters, J., Varley-Campbell, J., Cockcroft, E., Hendon, J., & Churchill, R. (2018). Revisiting the need for a literature search narrative: A brief methodological note. Research Synthesis Methods, 9(3), 361–365. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1315

- Cooper, H. M. (2017). Research synthesis and meta-analysis: A step-By-step approach (5th ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878644

- Cramer, C., & Schreiber, F. (2018). Subject didactics and educational sciences. Relationships and their implications for teacher education from the viewpoint of educational sciences. Research in Subject-Matter Teaching and Learning, 1(2), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.23770/rt1818

- Craven, J., & Levay, P. (2011). Recording database searches for systematic reviews - what is the value of adding a narrative to peer-review checklists? A case study of NICE interventional procedures guidance. Evidence-based Library and Information Practice, 6(4), 72–87. https://doi.org/10.18438/b8cd09

- Davis, K., Drey, N., & Gould, D. (2009). What are scoping studies? A review of the nursing literature. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(10), 1386–1400. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2009.02.010

- Decuypere, M. (2018). STS in/as education: Where do we stand and what is there (still) to gain? Some outlines for a future research agenda. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(1), 136–145. https://doi.org/10.1080/01596306.2018.1549709

- Firth, J. R. (1957). A synopsis of linguistic theory 1930-1955. In J. R. Firth (Ed.), Studies in Linguistic Analysis (pp. 1–32). Blackwell.

- Floridi, L. (2014). The fourth revolution: How the infosphere is reshaping humanity. OUP Oxford.

- Fransson, G., Holmberg, J., Lindberg, O. J., & Olofsson, A. D. (2019). Digitalise and capitalise? Teachers’ self-understanding in 21st-century teaching contexts. Oxf Rev Educ, 45(1), 102–118. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2018.1500357

- Frolova, E. V., Ryabova, T. M., & Rogach, O. V. (2019). Digital technologies in education: Problems and prospects for “Moscow electronic school” project implementation. European Journal of Contemporary Education, 8(4), 779–789. https://doi.org/10.13187/ejced.2019.4.779

- Grant, M. J., & Booth, A. (2009). A typology of reviews: An analysis of 14 review types and associated methodologies. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 26(2), 91–108. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-1842.2009.00848.x

- Gusenbauer, M., & Haddaway, N. R. (2020a). What every researcher should know about searching - clarified concepts, search advice, and an agenda to improve finding in academia. Research Synthesis Methods, 12(2), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1457

- Gusenbauer, M., & Haddaway, N. R. (2020b). Which academic search systems are suitable for systematic reviews or meta-analyses? Evaluating retrieval qualities of google scholar, PubMed, and 26 other resources. Research Synthesis Methods, 11(2), 181–217. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1378

- Hammersley, M. (2004). Teaching qualitative methodology: Craft, profession or bricolage. In C. Seale, G. Gobo, J. F. Gubrium, & D. Silverman (Eds.), Qualitative research practice (pp. 549–560). Sage.

- Hattie, J. (2009). Visible learning. A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement. Routledge.

- Haven, T. L., Errington, T. M., Gleditsch, K. S., van Grootel, L., Jacobs, A. M., Kern, F. G., Piñeiro, R., Rosenblatt, F., & Mokkink, L. B. (2020). Preregistering qualitative research: A delphi study. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406920976417

- Haven, T. L., & Van Grootel, D. L. (2019). Preregistering qualitative research. Accountability in Research, 26(3), 229–244. https://doi.org/10.1080/08989621.2019.1580147

- Hayes, A. F., & Krippendorff, K. (2007). Answering the call for a standard reliability measure for coding data. Communication Methods and Measures, 1(1), 77–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/19312450709336664

- Hoogerheide, V., Visee, J., Lachner, A., & van Gog, T. (2019). Generating an instructional video as homework activity is both effective and enjoyable. Learning and Instruction, 64, 101226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101226

- Kern, F. G., & Gleditsch, K. S. (2017). Exploring pre-registration and pre-analysis plans for qualitative inference [Preprint ahead of publication]. https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.14428.69769

- Khirfan, L., Peck, M., & Mohtat, N. (2020). Systematic content analysis: A combined method to analyze the literature on the daylighting (de-culverting) of urban streams. MethodsX, 7, 100984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2020.100984

- Klette, K., Sahlström, F., Blikstad-Balas, M., Luoto, J., Tanner, M., Tengberg, M., Roe, A., & Slotte, A. (2018). Justice through participation: Student engagement in nordic classrooms. Education Inquiry (Co-Action Publishing), 9(1), 57–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/20004508.2018.1428036

- Kolbe, R. H., & Burnett, M. S. (1991). Content-Analysis research: An examination of applications with directives for improving research reliability and objectivity. Journal of Consumer Research, 18(2), 243–250. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2489559 https://doi.org/10.1086/209256

- Kracauer, S. (1952). The challenge of qualitative content analysis. Public Opinion Quarterly, 16(4), 631–642. https://doi.org/10.1086/266427

- Krippendorff, K. (2019). Content analysis. An introduction to Its methodology (4th ed.). Sage. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781071878781

- Kuhn, T. S. (1970). The structure of scientific revolutions (2nd ed.). University of Chicago Press.

- Labaree, D. F. (1998). Educational researchers: Living with a lesser form of knowledge. Educational Research, 27(8), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X027008004

- Larsen, K. R., Voronovich, Z. A., Cook, P. F., & Pedro, L. W. (2013). Addicted to constructs: Science in reverse? Addiction, 108(9), 1532–1533. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12227

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O'Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

- Lin, E., Wang, J., Klecka, C. L., Odell, S. J., & Spalding, E. (2010). Judging research in teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education, 61(4), 295–301. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110374013

- Loeckx, J. (2016). Blurring boundaries in education: Context and impact of MOOCs. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 17(3), 92–121. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v17i3.2395

- Lombard, M., Snyder-Duch, J., & Bracken, C. (2005). Practical resources for assessing and reporting intercoder reliability in content analysis research projects. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242785900_Practical_Resources_for_Assessing_and_Reporting_Intercoder_Reliability_in_Content_Analysis_Research_Projects/citations

- Mays, N., Roberts, E., & Popay, J. (2001). Synthesising research evidence. In N. Fulop, P. Allen, A. Clarke, & N. Black (Eds.), Studying the organisation and delivery of health services: Research methods (pp. 188–220). Routledge.

- Miguel, E., Camerer, C., Casey, K., Cohen, J., Esterling, K. M., Gerber, A., Glennerster, R., Green, D. P., Humphreys, M., Imbens, G., Laitin, D., Madon, T., Nelson, L., Nosek, B. A., Petersen, M., Sedlmayr, R., Simmons, J. P., Simonsohn, U., & Van der Laan, M. (2014). Social science. Promoting transparency in social science research. Science, 343(6166), 30–31. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1245317

- Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., Stewart, L. A., & Group, P.-P. (2015). Preferred reporting items for systematic review and meta-analysis protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

- Moher, D., Stewart, L., & Shekelle, P. (2015). All in the family: Systematic reviews, rapid reviews, scoping reviews, realist reviews, and more. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 183. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-015-0163-7

- Morse, J. M. (1995). Exploring the theoretical basis of nursing using advanced techniques of concept analysis. ANS. Advances in Nursing Science, 17(3), 31–46. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-199503000-00005

- Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

- Murphy, P. K., & Alexander, P. A. (2000). A motivated exploration of motivation terminology. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 3–53. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1019

- Murphy, P. K., Knight, S. L., & Dowd, A. C. (2017). Familiar paths and new directions. Review of Educational Research, 87(1), 3–6. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317691764

- Nightingale, A. (2009). A guide to systematic literature reviews. Surgery (Oxf), 27(9), 381–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpsur.2009.07.005

- Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C., & Mellor, D. T. (2018). The preregistration revolution. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(11), 2600–2606. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1708274114

- Nutley, S., Davies, H., & Walter, I. (2002). Conceptual synthesis 1: Learning from the diffusion of innovations. University of St. Andrews.

- Peters, M., Godfrey, C., McInerney, P., Soares, C., Khalil, H., & Parker, D. (2015). Methodology for JBI scoping reviews. In E. Aromataris (Ed.), The joanna briggs institute reviewers manual 2015 (pp. 3–24). Joanna Briggs Institute.

- Petticrew, M., & Roberts, H. (2006). Systematic reviews in the social sciences. A practical guide. Blackwell Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1002/9780470754887

- Pham, M. T., Rajic, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371–385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

- Piñeiro, R., & Rosenblatt, F. (2016). Pre-analysis plans for qualitative research. Revista de Ciencia Política (Santiago), 36(3), 785–796. https://doi.org/10.4067/s0718-090×2016000300009

- Reed, J. G., & Baxter, P. M. (2009). Using reference databases. In H. M. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed., pp. 73–102). Sage.

- Rodgers, B. L. (1989). Concepts, analysis and the development of nursing knowledge: The evolutionary cycle. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 14(4), 330–335. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.1989.tb03420.x

- Rodgers, B. L. (1991). Using concept analysis to enhance clinical practice and research. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 10(1), 28–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/00003465-199101000-00006

- Rodgers, B. L. (2000). Concept analysis. An evolutionary view. In B. L. Rodgers, & K. A. Knafl (Eds.), Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications (2nd ed., pp. 77–102). Saunders.

- Rodgers, B. L., & Knafl, K. A. (2000). Concept development in nursing: Foundations, techniques, and applications (2nd ed.). Saunders.

- Rothstein, H. R., & Hopewell, S. (2009). Grey literature. In H. M. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed., pp. 103–125). Sage. DE-576;DE-208 http://swbplus.bsz-bw.de/bsz304537101inh.htm.

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage.

- Singer, L. M., & Alexander, P. A. (2017). Reading on paper and digitally: What the past decades of empirical research reveal. Review of Educational Research, 87(6), 1007–1041. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654317722961

- Snook, I., O’Neill, J., Clark, J., O’Neill, A.-M., & Openshaw, R. (2009). Invisible learnings?: A commentary on John Hattie’s book ‘Visible learning: A synthesis of over 800 meta-analyses relating to achievement’. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 44(1), 93–106.

- Thomas, J., McNaught, J., & Ananiadou, S. (2011). Applications of text mining within systematic reviews. Research Synthesis Methods, 2(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.27

- Thompson, J., Davis, J., & Mazerolle, L. (2014). A systematic method for search term selection in systematic reviews. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(2), 87–97. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1096

- Torgerson, C., Hall, J., & Lewis-Light, K. (2017). Systematic reviews. In R. Coe, M. Waring, L. V. Hedges, & J. Arthur (Eds.), Research methods & methodologies in education (2nd ed., pp. 166–179). Sage.

- Walker, L. O., & Avant, K. C. (2019). Strategies for theory construction in nursing (6th ed.). Pearson.

- Whitacre, I., Henning, B., & Atabaș, Ș. (2020). Disentangling the research literature on number sense: Three constructs, One name. Review of Educational Research, 90(1), 95–134. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654319899706

- White, H. D. (2009). Scientific communication and literature retrieval. In H. M. Cooper, L. V. Hedges, & J. C. Valentine (Eds.), The handbook of research synthesis and meta-analysis (2nd ed., pp. 51–72). Sage. DE-576;DE-208 http://swbplus.bsz-bw.de/bsz304537101inh.htm.

- White, M. D., & Marsh, E. E. (2006). Content analysis: A flexible methodology. Library Trends, 55(1), 22–45. https://doi.org/10.1353/lib.2006.0053

- Wilson, J. (1963). Thinking with concepts. Cambridge University Press. http://search.ebscohost.com/login.aspx?direct=true&scope=site&db=nlebk&db=nlabk&AN=570401