ABSTRACT

Surrounded by an environment of constantly changing social, technological, and natural conditions, today’s schools must dynamically improve and adapt to these conditions in order to survive. In this context, school leaders play an important role as the main drivers of innovation and change in education, trusting their team of teachers, and encouraging teachers’ innovativeness. Against this background, our study highlights the importance of creating an innovative working climate characterised by trust and experimentation. Our study is based on a cross-sectional, randomised and representative data set of N = 411 school leaders in Germany and applies mediated structural equation modelling. It examines the effect of school leader trust in teachers on teachers’ collective innovativeness as a prerequisite for school improvement and change, and the mediating role of individual and organisational exploration and exploitation as components of ambidexterity. The results of our analysis point to three main findings: First, school leaders’ trust in teachers has a significant direct relationship with teachers’ collective innovativeness. Second, the mediating variables of both school leader and school exploration have significant relationships with collective teacher innovativeness. Third, school leader exploration and exploitation are micro-foundations of organisational ambidexterity. By identifying manageable levers of change and providing prescriptive guidance on how schools can respond to dynamically changing environments, our study has implications for a theory of school improvement and change, for the practice of school improvement and change, and for education policy and frameworks for the training and professional development of teachers in general and school leaders in particular.

Introduction

Schools have always faced social, technological and economic challenges. In recent years, these challenges appear to be particularly significant in the light of the COVID-19 pandemic, where school leaders and teachers have had to develop and implement new forms of distance teaching and learning at exceptionally short notice (Fotheringham et al., Citation2022; Harris & Jones, Citation2020). In addition, the huge migratory movements caused by conflicts and wars worldwide also pose major challenges for schools (Arar, Citation2020). Schools as organisations need to improve and adapt to meet these challenges (Bingham & Burch, Citation2019). They are called upon to engage in a continuous learning process, which includes developing the ability to generate, collect and share knowledge independently and to change based on new knowledge (Stoll & Kools, Citation2017). There is a need to achieve higher levels of learning in the sense of Argyris and Schön (Citation1978), i.e. double-loop learning and deutero learning.

School leaders play an important role in this organisational learning process. As leaders and managers, they shape, influence and even define critical characteristics of the school – i.e. visions, structures and processes, working conditions, and staff capacity (Hallinger, Citation2011; Leithwood et al., Citation2020a) – and thus act as key drivers of educational innovation and change (Bryk, Citation2010; Harris et al., Citation2013). Accordingly, the link between school leadership, innovation and change has received increasing attention over the last two decades (Kovačević & Hallinger, Citation2019). Meanwhile, leadership is considered to be one of the most influential predictors of innovation and change in educational settings (Buyukgoze et al., Citation2022; Manz et al., Citation1989; Mumford et al., Citation2002; Jansen et al., Citation2009; Nemanich & Vera, Citation2009).

Nevertheless, how and whether innovations are actually implemented in schools depends largely on teachers’ individual and collective innovativeness (Blömeke et al., Citation2021; Nguyen et al., Citation2021). In this context, teacher innovativeness refers to teachers’ reciprocity, openness, and willingness to embrace change. These include the development of new teaching ideas and ways of solving problems and mutually supporting and implementing new ideas (Fullan, Citation2016). It is seen as a critical component in creating an innovative working environment and potentially leading to innovation (Blömeke et al., Citation2021; Buyukgoze et al., Citation2022). Empirical research shows that school leadership influences teachers’ innovativeness, particularly through specific leadership styles (Buyukgoze et al., Citation2022; O’Shea, Citation2021).

However, innovation and change in schools are closely related to the feeling of trust. Trust is essential for learning and improvement (Moolenaar & Sleegers, Citation2010), generally regarded as a significant resource for social action (Luhmann, Citation1979), necessary in moments of uncertainty and decision-making, but remains insecure on behalf of individual and organisational expectations (Colquitt et al., Citation2011). Therefore, trust in others’ competence, reliability, and integrity comes with a certain risk. Accordingly, much school literature on learning processes and outcomes revealed that trust is an antecedent to critical education processes and outcomes, e.g. professional learning, instructional change and collaboration (Adams & Miskell, Citation2016). Nonetheless, trust phenomena from leaders’ perspectives play a minor role in the school context. This contribution will set off this point: In our study, we built on research that examined the relationship between trust and schools’ functioning, tying trust to schools’ innovation capacity (Cosner, Citation2009; Louis & Murphy, Citation2017; Tschannen-Moran, Citation2009). More concretely, we focussed on school leaders and examined the effects of school leader trust in teachers on collective teacher innovativeness as a precursor of school improvement and change. In doing so, we examined individual and organisational ambidexterity’s potential role as a complementary set of activities and processes in mediating these effects. The literature suggests that (organisational) ambidexterity – i.e. “the ability to simultaneously pursue both incremental and discontinuous innovation … from hosting multiple contradictory structures, processes and cultures within the same” (Tushman & O’Reilly, Citation1996, p. 24) organisation – mediates the trust-innovativeness relationship (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004).

Two central questions guided our research:

What is the relationship between school leader trust in teachers and collective teacher innovativeness?

How does individual and organisational ambidexterity mediate the relationship between school leader trust in teachers and collective teacher innovativeness?

The article aims to provide information on the value of principal trust in teachers for school development and the mediating role of ambidexterity in this context. Therefore, it aims to offer an understanding of/insights into the mechanisms at work within schools in building teachers’ collective innovativeness as an important predictor of school development. In this way, the knowledge gained contributes to the advancement of a theory of school development. Furthermore, our findings support schools in addressing the many challenges by improving school development activities in terms of school leadership behaviour and teacher team attitudes. Finally, our findings allow implications for optimising educational policies and their frameworks for the training and professional development of teachers in general and particuraly for school leaders.

The study is based on the following three concepts: school leader trust in teachers; collective teacher innovativeness; and individual and organisational ambidexterity. The following section discusses these concepts separately and then connects them with the study's aims.

Literature review

The examination of significant literature informs the development of the study’s conceptual framework, which will be explained afterward.

School leader trust in teachers

Busco et al. (Citation2006) defined the concept of trust “as risky engagement, where someone (the trustor – the subject of trust) has trust in someone or something (the trustee – the object of trust) in some respect and under certain conditions (the context)” (p. 18). Mayer et al. (Citation1995) described trust as “the willingness to be vulnerable to the actions of another party based on the expectation that the other will perform a particular action important to the trustor, irrespective of the ability to monitor or control the other party” (p. 172). According to this definition, trust is essential wherever people are free to choose their actions. In this way, the authors conceptualised trust as a psychological state, breaking with the previously prevailing view of trust exclusively as a stable personality trait, in which the characteristics of the person who receives trust are relevant (Schoorman et al., Citation2007). Generally, trust can be differentiated into trust in people and trust felt or perceived by people (Salamon & Robinson, Citation2008).

From the trustee’s perspective, perceived trustworthiness factors play a key role. A trustworthy trustee proves that they deserve the trust that they receive. Thus, the trustee's observed character traits and past actions determine whether they are viewed as trustworthy. Drivers of the perceived trustworthiness of a trustee include their perceived task- and situation-specific skills, benevolence and integrity towards the trustor (Mayer et al., Citation1995).

Reliability, honesty and openness are mentioned in the literature as further central characteristics (Tschannen-Moran & Hoy, Citation2000). Scholars presently agree on the facets stated above as general trust attributes (Adams & Miskell, Citation2016).

Unlike this cognition-based view, the affect-based perspective on trust argues that the emotional bonds between the two parties serve as affective foundations of trust, i.e. as long as an individual believes in the intrinsic virtue of trust relationships and invests in them emotionally by expressing genuine concern and care for others, the emotional ties that link individuals can ultimately provide the basis for trust (Byun et al., Citation2017). The distinction between cognitive trust (in capacities and professionalism) and affective trust (liking, personal affinity) is common in the literature and indicates the existence of two different conceptualisations of trust (Byun et al., Citation2017).

Extant organisational research has identified trust as a major factor in creating functioning norms within organisations, i.e. differences in levels of workforce satisfaction, cohesion and commitment can be explained by the (perceived) amount of trust, and has found that individual relationships embedded in trust are linked strongly to a positive working climate within organisations. However, the mechanisms involved remain largely unclear. In education research, trust has evolved into an important variable over the past two decades (Andersson & Liljenberg, Citation2020). Correlations have been identified between trust and school climate (e.g. Bryk et al., Citation2010; Hoy et al., Citation2008; Tschannen-Moran & Gareis, Citation2015), cooperation (Tschannen-Moran, Citation2014), loyalty and commitment among employees (Bryk et al., Citation2010), as well as school improvement (e.g. Louis, Citation2007).

Even though extant studies have focused so far on collegial (lateral) trust among teachers and – mainly – teachers’ trust in their school leaders (vertical), research attention is rarely paid to school leaders’ trust in their teachers (i.e. Bryk & Schneider, Citation2002; Colquitt et al., Citation2007; Cosner, Citation2009; Dietz & Hartog, Citation2006; Fulmer & Gelfand, Citation2012; Handford & Leithwood, Citation2013; Ladegard & Gjerde, Citation2014; Tschannen-Moran & Gareis, Citation2015). Nevertheless, the concept of trust often is multidimensional and distributed among different groups within an organisation (Louis & Murphy, Citation2017), and the dynamics of trust are characterised by reciprocity (Serva et al., Citation2005): If leaders do not embody trust in teachers, teachers are likely to view their leaders in the same negative light (Brower et al., Citation2000). The aspect of reciprocity is fundamental within the scope of our interest in knowledge. Trusting employees also have far-reaching consequences for the trustor in a leadership position and how they design the working environment. For example, leaders who trust their employees take more risks in their own capacity (Ladegard & Gjerde, Citation2014), give employees more freedom to experiment (Brower et al., Citation2009) and involve them more frequently in management decisions (Spreitzer & Mishra, Citation1999).

The empirical evidence on leaders’ trust in their subordinates indicates that trust which leaders place on subordinates is likely to encourage subordinates to be committed to their jobs or to work harder, thereby enhancing the quality of exchange relations between leaders and subordinates (Byun et al., Citation2017; Dulebohn et al., Citation2012; Liden et al., Citation2008). For example, the more leaders focus on discipline, the less they are viewed as supportive of risk-taking and the less trusting the climate, inhibiting learning (Edmondson et al., Citation2001).

For the first time, Louis and Murphy (Citation2017) drew attention to the relationship between school leaders’ trust in their teachers’ competence and schools’ organisational learning. It is defined as searching for new information, processing and evaluating information with others, incorporating and using new ideas, generating ideas within the organisation, and importing them from the outside in a habituated way. They found an indirect relationship between these variables.

In our study, we started from this point by focussing on the relationship between school leaders’ trust in their teachers and teachers’ collective innovativeness as a precursor for school improvement and change. In line with Louis and Murphy (Citation2017) and the empirical evidence stated above, we assumed that trust

may determine whether a … [school leader] adopts a bureaucratic and contractual approach to working with teachers or an approach that is more distributive and engaging … Where trust is low, the climate for strengthening teacher professionalism will be limited, and teachers are more likely to be disengaged. In contrast, when … [school leaders] trust their teachers, teachers are more likely to interpret school leaders’ behaviours as supportive and in their best interests. (p. 106)

In the subsequent section, the above-stated concepts – i.e. collective teacher innovativeness as a precursor for school improvement, change, exploration, and exploitation, as different approaches to dealing with tasks and challenges (ambidexterity) – are presented.

Collective teacher innovativeness

In the literature, teacher innovativeness is conceptualised as teachers’ receptivity, openness and willingness to adopt change (Fullan, Citation2016), as well as teachers’ continual participation in change-related professional activities (McGeown, Citation1980). It also is viewed as the degree of teachers’ capacity and ability to change (Lin, Citation2022). Based on a literature review, Blömeke et al. (Citation2021) identified several different operationalisations of innovativeness: (1) as an individual attitude; (2) as a psychological climate characteristic; (3) as an organisational climate characteristic; and (4) as an organisational leadership characteristic. Individual innovativeness refers to a personal attitude towards doing something via statements, e.g. “I am receptive to new ideas” (Hurt et al., Citation1977); psychological climate characteristics are identified through organisational members’ assessment of their organisations through statements, e.g. “This team is open and responsive to change” (Anderson & West, Citation1998), but the responses are analysed at the individual (member) level; organisational climate characteristics, again, are measured through statements, e.g. “This team is open and responsive to change”, which are assessed by individual members, then aggregated to and analysed on the organisational level; and organisational leadership characteristics can be viewed as organisational leaders’ innovativeness qualities (Buyukgoze et al., Citation2022).

These operationalisations indicate that innovativeness can be defined and measured at the individual level (Akar, Citation2019) and collective level (Buske, Citation2018; Schwabsky et al., Citation2019). At the individual level, innovativeness as an attitude (which is separate from actual behaviour, e.g. Venkatraman & Price, Citation1990) refers to a person’s openness to new ideas. However, collective innovativeness is classified as a characteristic of a group with a common awareness of its members’ focus on innovations. It can be viewed as a team or other organisation’s receptivity and readiness for change (Buske, Citation2018). Collective innovativeness is highly pronounced among the teaching staff when the individual teachers are highly willing to support and actively advance school improvement, perceive the need for improvement with regard to joint school development work and have set and pursue common goals for the entire teaching staff (Buske, Citation2018).

In our study, we define teacher innovativeness as an organisational climate characteristic for assessing teachers’ collective innovativeness at the school level and addressing it as the extent to which school leaders perceive their working climate and their team of teachers as innovative.

From a research perspective, teacher innovativeness functions as a critical factor that influences teachers’ innovative behaviours and is of paramount importance in the implementation, sustainment and proliferation of innovations in schools (Buske, Citation2018; Schwabsky et al., Citation2019). In this way, it is a prerequisite for innovation and change (Kern & Graber, Citation2018). So far, teacher innovativeness has mainly been studied at the individual level, i.e. studies focussing on collective innovativeness in schools are rare (Buske, Citation2018; Newman et al., Citation2020).

Empirical evidence indicates that teacher innovativeness is subject to a combination of individual and organisational factors. The literature has identified teacher autonomy (Lin, Citation2022; Nguyen et al., Citation2021), collaborative school culture and teacher professional learning (Nguyen et al., Citation2021) as potentially influential factors. According to school leaders, a distributed leadership style (Buyukgoze et al., Citation2022; Lin, Citation2022; O’Shea, Citation2021), as well as two complementary sets of leadership behaviours (explorative and exploitative) have been viewed as influencing collective teacher innovativeness. Investigative results revealed that explorative leadership activities positively predict collective innovativeness, whereas exploitative leadership activities do not exert a significant effect (Rosing et al., Citation2011). Notably, collective innovativeness is highest when both explorative and exploitative leadership activities are high, but lower when only one of these leadership activities is high or when both are low (Rosing et al., Citation2011; Zacher & Rosing, Citation2015).

Individual and organisational ambidexterity

Innovation always involves uncertainty and the insecurity of whether a creative idea will work in practice (Jalonen, Citation2012), with the degree of uncertainty varying with the environment’s complexity and changeability (Damanpour, Citation1996). In this context, innovativeness always is linked to the extent to which someone is willing to take risks (Hurt et al., Citation1977). Consequently, risk and uncertainty can be viewed as two ends of a continuum of environmental predictability (Hmieleski et al., Citation2015) that influences individual and collective opportunity exploration and exploitation (Magnani & Zucchella, Citation2018).

In this context, exploration refers to experimentation and innovation processes and, thus, to the search for new opportunities, while exploitation relates to efficiency and refinement processes and, thus, to the use of existing opportunities and resources (Koza & Lewin, Citation1998; March, Citation1991). Accordingly, as March (Citation1991) noted in his seminal work, “The essence of exploitation is the refinement and extension of existing competencies, technologies and paradigms …. The essence of exploration is experimentation with new alternatives” (p. 85). Drawing on earlier work by the Carnegie School on organisational learning, March understood organisations as social systems embedded in larger institutional and historical contexts (Augier, Citation2018) that need to continually adapt to their ever-changing environment through experimentation and learning (Augier, Citation2004). Consequently, he defined exploitation as activities that draw on existing knowledge, where “the people who engage in them ‘exploit’ what they already know” (Strober, Citation2011, p. 21), while people and organisations engaged in exploration move away from existing knowledge and seek new knowledge (Strober, Citation2011). The terms exploitation and exploration can thus be understood as allegories for mining companies that are engaged in the exploitation of existing resources (exploitation), consistently optimising their mining operations in order to get the last thing out of the existing properties, on the one hand, and searching for new resources to broaden their property portfolio (exploration), on the other, and where it can be assumed that a company can no longer survive if the existing resources are exhausted at some point and no new ones have been discovered. In this understanding, both exploitation and exploration include some kind of learning (Gupta et al., Citation2006), but follow different logics: While exploitation is about efficiency, control and variance reduction, exploration is about search, autonomy, and embracing variation (O’Reilly & Tushman, Citation2008). Consequently, exploitation is assiociated with mechanistic structures, tightly coupled systems, and stability, while exploration relates to organic structures, loosely coupled systems, and chaos (He & Wong, Citation2004). While exploitation primarily is concerned with the comparatively certain present, exploration is oriented towards the rather uncertain future (Papachroni et al., Citation2016). In organisations, both exploitation and exploration lead to change, with exploitation leading to incremental change and exploration leading to radical change (Maclean et al., Citation2021), i.e. they involve differences in the type and amount of learning (Gupta et al., Citation2006).

Thus, exploitation can be viewed as single-loop learning and exploration as double-loop learning (Brix, Citation2019; Papachroni et al., Citation2015) in the sense of Argyris and Schön (Citation1978), assuming that to ensure their longevity, organisations simultaneously must act effectively in the present and develop and implement innovative ideas and visions for the future (O'Reilly & Tushman, Citation2013; Raisch et al., Citation2009). Consequently, Levinthal and March (Citation1993) argued that

an organisation that engages exclusively in exploration will ordinarily suffer from the fact that it never gains the returns of its knowledge. An organisation that engages exclusively in exploitation will ordinarily suffer from obsolescence. The basic problem confronting an organisation is to engage in sufficient exploitation to ensure its current viability and, at the same time, to devote enough energy to exploration to ensure its future viability. Survival requires a balance, and the precise mix of exploitation and exploration that is optimal is hard to specify. (p. 105)

As O'Reilly and Tushman (Citation2013) show, organisational ambidexterity can be achieved sequentially and/or structurally and/or contextually. The sequential path to ambidexterity involves the dynamic realignment and temporal shifting of an organisation's structures and processes between exploration and exploitation over time, and is often characterised by “long periods of exploitation and short bursts of exploration” (Gupta et al., Citation2006, p. 698). The structural pathway to ambidexterity involves separate departments or work units within an organisation, such as research and development (R&D) and administrative departments, exploring and exploiting through different competencies, cultures, processes and structures that are internally aligned and managed by leaders (O’Reilly & Tushman, Citation2016). Both sequential and structural ambidexterity require structural measures in an organisation, i.e. the creation of specialised organisational (sub-)units or their dynamic transformation. The contextual route to ambidexterity, on the other hand, is achieved by creating a supportive work environment that encourages individuals in organisations to optimally allocate their time between exploratory and exploitative activities (Havermans et al., Citation2015). In essence, contextual ambidexterity emphasises the integration of exploration and exploitation within a single organisation, department or work unit, but allows for differentiated use of both activities by individuals (Wang & Rafiq, Citation2014). It is therefore less about the organisation itself and more about the individuals within it, with an organisational “context characterised by a combination of stretch, discipline, support and trust” (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004, p. 209).

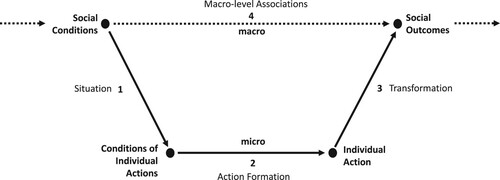

Accordingly, organisational and individual ambidexterity are related closely, as an organisation’s dynamic capabilities are constituted by the underlying actions of individuals within the organisation (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2010). This so-called micro-foundational perspective on organisational ambidexterity assumes that all explanations of organisational higher-level phenomena have lower-level phenomena or actors as proximate causes (Eisenhardt et al., Citation2010; Felin et al., Citation2015; Tarba et al., Citation2020). The point of reference is the bathtub model by Coleman (Citation1990, see ), according to which collective phenomena occur because organisational antecedents influence individuals’ conditions that, in turn, induce their actions, subsequently leading to social outcomes (Felin et al., Citation2015; Felin & Foss, Citation2020). As Felin and Foss (Citation2020) stated, the Coleman model is an example of a multilevel path diagram. Consequently, Linder and Foss (Citation2018) concluded:

More ambitiously, the micro-foundations argument involves a strong, full mediation claim: The effects of macro-entities (e.g. institutions) are always fully mediated through micro-actors and mechanisms. (p. 41)

Although the concept of ambidexterity has not been extensively explored in schools, the few educational research studies that have addressed the topic to date have consistently found that schools and school personnel are primarily exploitative in nature (Pietsch et al., Citation2022a), but that the exploration of both school leadership and schools in particular affects teacher creativity and innovation in schools (Pietsch et al., Citation2022b; Da’as, Citation2021, Citation2022). Here, the authors conceptualise individual and organisational ambidexterity in line with previous general organisational and management research and demonstrate the applicability of the concept to educational research and practice. As Bingham and Burch (Citation2019) argue, applying the concept of ambidexterity as a theoretical framework in educational research may help to identify descriptively manageable levers of change, provide prescriptive guidance on how schools as organisations can manage and respond to policy pressures, and consequently address the dilemmas of educational reform by answering the question: “How do school systems manage environmental pressures to reconstitute themselves as more coherent and instructionally effective organisations, while managing their inherited differentiated organisations and the environmental pressures that support them?” (Cohen et al., Citation2018, p. 208).

Linking school leader trust and collective teacher innovativeness via ambidexterity

As stated earlier, trust reduces complexity and uncertainty in personal relations (Luhmann, Citation1979); thus, organisational trust “is central to the development of an innovation-supportive culture because trust enables people to take risks without fear of or undue penalty for failure” (Chandler et al., Citation2000, p. 62). Consequently, trust is a key prerequisite for innovativeness within organisations (Sankowska, Citation2013).

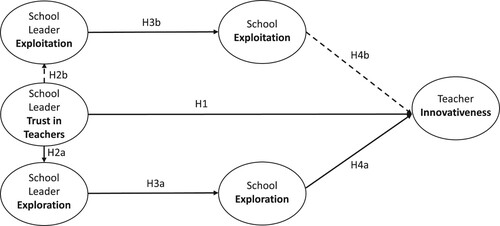

The presented empirical findings indicate that school leader trust directly and indirectly affects teachers’ exertions and collective teacher innovativeness. Especially, school leaders’ role in creating ambidextrous cultures, that enhance risk-taking and explorative activities while reducing exploitative activities, is highly relevant. Therefore, based on our literature review, we tested the mediation model in , which illustrates the relationships between the variables of interest in this study, namely school leader trust in teachers, school leader exploration and exploitation, school exploration and exploitation and collective teacher innovativeness. In this conceptual framework, school leader trust in teachers is the major independent variable. Its direct effects on collective teacher innovativeness are proposed based on the very first empirical evidence concerning the relationship between both variables. School leader exploration and exploitation are viewed as micro-foundations of school exploration and exploitation, which are viewed as predictors of collective teacher innovativeness. Thus, exploration and exploitation among school leaders and schools are posited as mediators between school leader trust and collective teacher innovativeness.

With these variables in mind, the following hypotheses were tested:

H1: School leader trust in teachers affects collective teacher innovativeness directly.

H2a: School leader trust in teachers affects school leader exploration.

H2b: School leader trust in teachers does not affect school leader exploitation.

H3a and H3b: School leader exploration and exploitation are micro-foundations of school exploration and exploitation and, therefore, affect them.

H4a: School exploration affects collective teacher innovativeness.

H4b: School exploitation does not affect collective teacher innovativeness.

Methods

Sample

For our research, we used data from the third wave of the Leadership in German Schools study, collected between August and November 2021 across Germany. Leadership in German Schools is a longitudinal study in which a random sample of school leaders, representative of Germany, has been surveyed during each wave (Pietsch et al., Citation2022a). In addition to longitudinal themes, wave-specific topics also were surveyed. In 2021, the focus was on innovation in schools. Field work was conducted by the forsa Institute for Social Research and Statistical Analysis (forsa Politik- und Sozialforschung GmbH, Berlin, Germany), a leading professional survey and polling company in Germany, via its omnibus and omninet panels, which interviewed a random sample of 1,000 people ages 14 and up on various topics by phone every working day, including their occupation. In this way, a random sample of N = 411 school leaders, also representative of Germany, was identified and given personalised access to an online questionnaire, which forsa also administered. Of these individuals, N = 103 already had participated in the previous two waves of the survey, and N = 308, a refreshment sample (Watson & Lynn, Citation2021), was being surveyed for the first time. In this study, we used cross-sectional data from these N = 411 school leaders.

N = 247 (63.3%) of the school leaders in our sample were female and N = 163 (36.7%) were male. The average age was 52.9 years, with a standard deviation of 6.9 years. Respondents had been working as school leaders for an average of 9.5 years at the time of the survey. N = 35 (8.5%) of the school leaders work in private schools, N = 374 (91.0%) work in public schools and N = 2 (0.5%) did not answer that question. Of the schools they lead, 63 (15.3%) are located in a village, hamlet or rural area (population less than 3,000); 106 (25.8%) are located in a small town (population 3,000 to approximately 15,000); 141 (34.3%) are located in a small city (population 15,000 to approximately 100,000); 75 (18.2%) are located in a medium size city (population 100,000 to approximately 1 million); and 25 (6.1%) are located in a large city (population over 1 million). For one school, contextual information was missing. On average, 381 students were enrolled in the participants’ schools, with a standard deviation of 316 and a 5 to 95th percentile range of 60–1,027 students.

Study context

The data were gathered in Germany, a state with a federal constitution, under which education is the responsibility of the 16 states (Länder); thus, this differed between states. However, all German states provide education for students ages 6–10 in comprehensive primary schools (Grundschulen). At about age 11, students enrol in fifth grade in secondary schools. At this transition point, students of varying abilities are tracked into different types of schools, which usually differ in both duration and curriculum. While German states traditionally have three different secondary school types – lower secondary (Hauptschule), middle secondary (Realschule) and upper secondary (Gymnasium) schools – most have introduced one or more types of comprehensive secondary schools in the course of various education reforms. German school leaders were long viewed primarily as administrators before their role shifted over the past two decades to include more management and leadership domains (Tulowitzki, Citation2015). Consequently, since the turn of the millennium, school leaders’ role has changed from head teachers to school improvement leaders, with corresponding expectations and demands placed on them (Klein & Schwanenberg, Citation2022).

Measures

The questionnaire comprised 35 item blocks, from which we used only a small part. To minimise common method bias (Podsakoff et al., Citation2012), measures were taken to counteract such bias, both in the instrument’s design and in data collection. For example, item wording and scale properties varied across scales, and both item blocks and individual items within blocks were rotated and scrambled randomly across individual surveys. We used the following variables as part of our study (also see Appendix):

School leader trust was measured following Mayer et al. (Citation1995) and Cunningham and MacGregor (Citation2000), thereby comprising four items assessing perceived benevolence (i.e. “I can, by and large, trust that the teachers at my school are committed to the future of my school”), competence (i.e. “I can, by and large, trust that the teachers at my school are very competent at their jobs”), honesty (i.e. “I can, by and large, trust the teachers at my school to be completely honest with me”) and integrity (i.e. “I can, by and large, trust that the teachers at my school will always keep their promises”) of the trustees, i.e. teachers. All items were measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”. The scale’s internal consistency, reported as McDonald’s omega (Citation1999), was ω = 0.87.

School leader exploitation was measured by applying three items developed by Mom et al. (Citation2009). These items intended to capture exploitation in the context of organisational learning, as defined by March (Citation1991), on the individual level (Pietsch et al., Citation2022a). Here, the school leader exploration scale captured the extent to which a school leader engaged in exploitation activities during the previous year (base question: “To what extent did you, during the last 12 months, engage in work-related activities that can be characterised as follows?”). All items were measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “to a small extent” to “to a large extent”. An example item: “Activities which you can properly conduct by using your present knowledge”. The leader exploitation scale’s internal consistency was ω = 0.84.

School leader exploration is based on the same preliminary work as the school leader exploitation scale. An example item: “Activities requiring you to learn new skills or knowledge”. The leader exploration scale’s internal consistency was ω = 0.77.

School exploitation also is based on the features by which March (Citation1991) characterised exploitation in the context of organisational learning. However, the items here do not refer to the school leader as a reference, but to the school as an organisation. Based on this and the work of Da’as (Citation2022), three items were developed to capture the school’s exploitative orientation. An example item: “Our school is continuously improving its quality”. All items were measured on a four-point Likert scale ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”. The school exploitation scale’s internal consistency was ω = 0.85.

School exploration was measured just like school exploitation. Again, three items were developed and used to capture the construct. An example item: “Our school is successful because we often try something new”. The school exploration scale’s internal consistency was ω = 0.87.

Teacher innovativeness was measured with a scale from the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development’s (OECD) Teaching and Learning International Survey (TALIS, OECD, Citation2019). The scale is a derivative of the team climate inventory (Ainley & Carstens, Citation2018; Anderson & West, Citation1998) and intends to assess teachers’ collective innovativeness at the school level. The scale comprises four items that could be rated by school leaders on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from “totally disagree” to “totally agree”. An example item: “Most teachers in this school strive to develop new ideas for teaching and learning”. The teacher innovativeness scale’s internal consistency was ω = 0.88.

Analytical strategy

To test our hypotheses, we estimated single-level mediated structural equation models in MPLUS 8.4 (Muthen & Muthen, Citation2017) using a maximum likelihood (ML) estimator and a maximum likelihood estimator with sandwich corrections (MLR). To avoid a confounding of structure and measurement in our model, we followed the two-step approach suggested by Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988). Accordingly, in a first step, we estimated the goodness of measurement models, and in a second step, we added the assumed structural relationships between model variables. Following Kline (Citation2016), model fit was tested using Steiger-Lind root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA), Bentler comparative fit index (CFI) and standardised root mean square residuals (SRMR). An acceptable model fit could be assumed if CFI ≥ .95, SRMR ≤ .08 and RMSEA ≤ .08 (Hu & Bentler, Citation1999; Marsh et al., Citation2004). We do not address the normed Χ2 statistic, as Kline (Citation2016, p. 272) explicitly dicourages it, stating “that it should have no role in global fit testing”.

Furthermore, we note that the RMSEA can be inflated in asymmetric data (Shi & Maydeu-Olivares, Citation2020), which is the case in our data for the trust scale. Possible non-normality was checked using SPSS, with missing cases deleted listwise. For the trust items, the bottom two categories were partly used only about 10% of the time and the skewness and kurtosis of the first item (i.e. “I can, by and large, trust that the teachers at my school are absolutely honest with me.”) suggest a moderate violation of the normal distribution assumption for that item (skewness: -.323; kurtosis: .812; Shapiro-Wilk-Test = 274.899 [df = 402], p < .001; Shapiro & Wilk, Citation1965). In this case, the SRMR statistic provides a better way to evaluate model fit of the principal trust scale (Shi & Maydeu-Olivares, Citation2020).

The amount of missing data was very low, with 1.2 percent missing values. Accordingly, we handled missing data by applying a full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation procedure. As we estimated an indirect path model, a model containing mediator variables, we tested mediation effects’ robustness by applying a bootstrapped mediation analysis, providing 95% bias-corrected bootstrap confidence intervals with 1,000 bootstrap replications (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008; Hayes, Citation2018). According to Hayes (Citation2018), the estimates of indirect effects can be viewed as statistically significant if the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) did not contain zero.

To examine the convergent and discriminant validity of our model and model variables we calculated the average variance extracted (AVE) of each construct (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981). The AVE is the average amount of variation that a latent construct can explain in the observed variables with which it is theoretically related. Convergent validity can be assumed if the AVE is above the threshold of .50 (Hair et al., Citation2010). Discriminant validity is assessed by comparing the AVE with the square root of the correlation coefficients of pairs of variables (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981), where the AVE for these variables must be greater than the shared variance (i.e. the square of the correlations) of the pairs of variables under consideration (Fornell & Larcker, Citation1981; Hair et al., Citation2010). Specifically, as Farrell (Citation2010) notes, the AVE estimates of both constructs examined must be greater than the estimate of the shared variance (and not the average of the AVE estimates).

As our data stemmed from a single instrument, we also tested for common method bias by conducting Harman’s single factor test (Harman, Citation1960) in advance. Thus, we loaded all model variables on a single unrotated factor and tested whether these variables explained a substantial amount of the factor variance. This procedure indicated that the items collectively explained 26.7 percent of this single factor, well below the threshold of 50 percent, above which substantial bias in further estimations through common method bias is expected (Lance et al., Citation2010). Accordingly, we took no further action in this regard.

Results

Descriptive statistics, correlations and univariate analyses

shows the descriptive statistics of the sample and the average variance extracted (AVE) as an indicator of convergent and discriminant validity. When reading the table, it should be noted that the data we used came from a random sample of school leaders, representative of Germany, who were surveyed in fall 2021. In the 12 preceding months, school leaders in Germany worked much more exploratively (m = 3.18) than exploitatively (m = 2.64), indicating that they were more concerned with experimenting with new alternatives than with refining and expanding existing conditions. Some months before the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, the values in Germany were m = 3.34 for school leader exploitation and m = 2.64 for school leader exploration (Pietsch et al., Citation2022a). Thus, it seems that as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, how school leaders in Germany explore and exploit knowledge and learning opportunities was completely reversed within two years. According to our data, schools in Germany, however, focussed on exploitative (m = 3.11) rather than explorative (m = 2.71) opportunities. As a result, schools were more focussed on incremental, rather than disruptive change. This is also reflected in teachers’ collective innovativeness, which school leaders rated quite highly (m = 3.12) and is associated with a high level of trust in teachers (m = 3.20). Most of the scales are highly correlated with each other, and it is striking that school leader exploration and exploitation indicated a negative correlation (r = -.303), indicating a trade-off. However, this is not found at the school level, i.e. school exploitation and exploration were highly positively correlated (r = .792).

Table 1. Means, standard deviations and latent correlations of model variables (lower triangle) and average variance extracted (AVE, diagonal).

The AVE of all measures exceeded the 0.50 threshold indicating adequate convergent validity. Furthermore, the squared correlation of each pair of constructs is in each case smaller than the associated AVE, supporting both the discreminant and the overall validity of the proposed conceptual model (Hair et al., Citation2010).

Structural equation model

Applying the two-step approach that Anderson and Gerbing (Citation1988) proposed, applying an ML estimator and treating indicators as continuous, we next inspected the quality of the measurement models, all of which indicated a good fit to the existing data (see ).

Table 2. Model fit indicators of latent constructs.

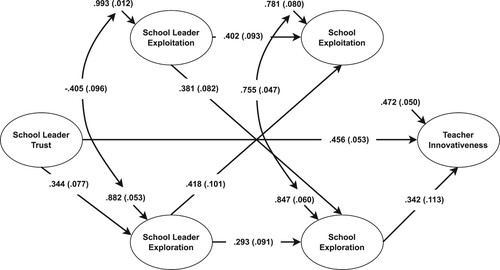

To test our hypotheses, we treated all indicator variables as continuous, and scrutinised a mediated structural equation model in MPLUS 8.4. The model assumed a direct path from leader trust to teacher innovativeness and indirect paths between these latent variables mediated by both school leader and school exploitation and exploration. As the theory assumed that interdependencies exist between exploration and exploitation, i.e. ambidexterity, we also added paths between school leader exploitation and school exploration and between school leader exploration and school exploitation. Additionally, we allowed correlations between school leader exploitation and exploration and between school exploitation and exploration. The proposed model demonstrated good fit to the data (χ2 = 274.899 [df = 159], p < .001, CFI = .95, RMSEA = .04, SRMR = .07). provides the standardised path coefficients and standard errors for each path, as well as the dependent latent variables’ residuals.

Figure 3. Structural equation model analysing the Leader Trust-Teacher Innovativeness relation.

Note: Only statistically significant paths are reported for clarity.

Overall, the model accounted for 53 percent of the variance in collective teacher innovativeness, demonstrating that school leader trust in teachers and both exploration on the level of leaders and the school level significantly influence teachers’ readiness for change. School leader trust was the strongest direct predictor (β = .456, SE = .053, p < .001), thereby confirming H1. We also found a significant effect (β = .342, SE = .113, p < .05) on school exploration, supporting H4a. Besides, school exploitation exerted no demonstrable influence on collective teacher innovativeness (β = .182, SE = .121, p > .10), confirming H4b. As expected, we found positive associations between school leader exploitation and exploration, and between school exploitation (βschool leader exploitation = .402, SE = .093, p < .001, βschool leader exploration = .418, SE = .101, p < .001) and exploration (βschool leader exploitation = .381, SE = .082, p < .001, βschool leader exploration = .293, SE = .091, p < .001), thereby supporting the theory-consistent assumption of micro-foundations of organisational ambidexterity and confirming H2a and H2b. Our findings also supported H3a and H3b: Thus, on the one hand, school leader trust exerted a positive significant effect on school leader exploration (β = .344, SE = .077, p < .001). On the other hand, the relationship between leader trust and school leader exploitation was small and insignificant (β = .084, SE = .069, p > .10).

Mediation analyses

To examine leader trust’s indirect effect on collective teacher innovativeness via school leader and school exploitation and exploration, we re-estimated the scrutinised model utilising a bootstrapping procedure with 1,000 replications and calculated total effects, i.e. the sum of direct and indirect effects. Here, the point estimates were similar to those estimated without bootstrapping, while the standard errors represent the standard deviation of the 1,000 estimates (Preacher & Hayes, Citation2008). School leader trust’s total effect on collective teacher innovativeness was statistically significant and meaningful (β = .534, CI [.330, .691], p < .001). The analysis further revealed that 85.4 percent of school leader trust’s effect on teacher innovativeness was direct and 14.6 percent was indirect. Of these 14.6, 11.4 percent could be attributed to school leader exploration (school leader trust -> school leader exploration -> school exploration -> collective teacher innovativeness = 6.5 percentage points (CI [.002; .155]); school leader trust -> school leader exploration -> school exploitation -> collective teacher innovativeness = 4.9 percentage points (CI [-.011; .207])). However, in this case, we were only able to demonstrate statistical significance for the effect involving both school leader and school exploration, as the bootstrap interval did not overlap with zero. Overall, the mediation analysis clearly indicated that in addition to leader trust’s strong direct effect on collective teacher innovativeness, an additional effect could be achieved if school leaders, as a consequence of trusting their teachers, take more risks themselves, act exploratively and, as a result, create an explorative working environment for teachers characterised by “search, variation, risk taking, experimentation, play, flexibility, discovery, innovation” (March, Citation1991, p. 71).

Robustness check for non-normality

As the item response distributions for the leadership trust indicators were partially skewed, we ultimately followed Li et al. (Citation2016) and Suh (Citation2015) and therefore treated the leadership trust indicators as categorical and applied an MLR estimator to examine the impact of potential misspecification and to validate the results of the joint model. Estimated as a categorical measurement model, the leadership trust construct fits the underlying data well (Pearson Chi-Square: χ2 = 241.242 [df = 238], p > .10; Likelihood Ratio Chi-Square: χ2 = 84.812 [df = 238], p > .10). Basically, this analysis confirms the previous results: 1. School leader trust (β = .462, SE = .077, p < .001) and school exploration (β = .337, SE = .130, p < .005) significantly affect teacher innovativeness; 2. both school leader exploration (β = .409, SE = .161, p < .05) and exploitation (β = .395, SE = .139, p < .05) affect school exploitation; 3. school leader exploration (β = .289, SE = .125, p < .05) and exploitation (β = .378, SE = .105, p < .001) affect school exploration; 4. school leader trust (β = .337, SE = .124, p < .05) affects school leader exploration; 5. school leader exploration and exploitation (r = -.397, SE = .131, p < .001) and school exploitation and exploration (r = .756, SE = .053, p < .001) are significantly correlated. For all other variables, as in the ML estimation, no statistically significant relationships were found. The mediation model indicates that the total effect of school leader trust on collective teacher innovativeness was statistically significant and meaningful (β = .536, p < .001). As bootstrapping with an MLR estimator is not possible in MPLUS, we do not report confidence intervals here.

Discussion and conclusions

Our study examined the effect of school leader trust in teachers on collective teacher innovativeness as a prerequisite for school improvement and change. It was based on a unique, randomised and representative data set of N = 411 school leaders in Germany. The mediating role of individual and organisational exploration and exploitation as components of ambidexterity was also investigated in the assumed relationship.

The results of our analysis point to three main findings: First, school leader trust in teachers has a significant direct association with collective teacher innovativeness. Second, the mediating variables of school leader and school exploration have significant relationships with collective teacher innovativeness. Third, school leader exploration and exploitation are micro-foundations of organisational ambidexterity.

Before interpreting these findings and discussing their possible implications, we would like to discuss our study’s limitations and offer suggestions for future research.

Limitations and future research

To the best of our knowledge, our study is the first to investigate the direct and indirect effects of leader trust in teachers on teacher innovativeness mediated by exploitation and exploration. In this context, we also used the concept of micro-foundations for the first time in education research. Accordingly, the study has many limitations, but also highlights many avenues for further research. The main limitation is that the data set used for our analyses only contains information provided by school leaders at one single point in time. As a result, causality only can be inferred, but cannot be demonstrated. We also were unable to investigate how ambidexterity emerges and develops over time, which would be helpful to better understand the dynamics of ambidexterity between the levels of leader and school, and between exploitation and exploration (Tarba et al., Citation2020). And even though it is quite common to ask leaders about innovation climate (Li et al., Citation2016; Loeb et al., Citation2022), it is well known that how leaders and other organisational members rate team and organisational climates can differ (Gibson et al., Citation2019), which, in turn, might affect the results of analyses due to leader-team perceptual distance (Tafvelin et al., Citation2017) and perceptual non-equivalence within organisations (Beus et al., Citation2012). Although rare to date, it is useful to examine the bathtub model that underpins the idea of micro-foundations using data from multiple levels (Distel, Citation2019), namely, school leaders and teachers. Furthermore, we did not measure teachers’ perceived trust directly, but inferred it indirectly, as no teacher data were available to us. These limitations can be addressed by surveying both leaders and teachers in schools longitudinally in future studies. Nevertheless, our study offers many opportunities for future research: First, because our results indicate that school leader trust influences leader functioning, future research should examine school leader trust in school stakeholders and the resulting effects at the individual level more intensively. Second, considering that we found that school leaders’ ambidexterity influences schools’ ambidexterity, and that higher-level organisational macro-phenomena emerge at lower micro-levels within schools, we recommend that the micro-foundations concept be brought into focus in education research. Third, ambidexterity at the individual (school leader) level seems to require a balance or specialisation in either exploitation or exploration (either/or logic), while ambidexterity at the school level seems to be orthogonal, with the consequence that exploitation and exploration can co-exist accordingly (both/and logic). Considering that the coupling of exploitation and exploration depends mainly on available resources, as well as the diversity of tasks or domains addressed (Gupta et al., Citation2006), any lack of resources (i.e. time, cognitive capacity etc.) and task complexities on the level of leaders prevent a corresponding coexistence of exploitation and exploration. How this occurs should be investigated too. Fourth, as school leader trust seems to be a main driver of teacher innovativeness, we recommend clarifying how school leaders can gain trust in their teachers and in this way set in motion an ever-evolving dynamic cycle of innovation in schools.

Interpretations and implications

Given that today’s schools are surrounded by an environment in which social, technological, and natural conditions are constantly changing, meaning that schools must dynamically adapt to these conditions in order to survive, our study underlines the importance of creating an innovative working climate characterised by trust and experimentation, and the important role that school leaders play in this context. More specifically, our results support the idea that school leader trust might play a role in promoting innovative teacher behaviour in schools. The established connection between school leader trust and collective teacher innovativeness corresponds with the very first empirical evidence on the subject (Louis & Murphy, Citation2017), but needs to be confirmed in further studies.

Broadening the current knowledge base, our results indicate that – as a consequence of school leaders’ explorative activities – the school itself becomes more open to innovations and alternative approaches, accompanied by increased collective teacher innovativeness. These findings contribute to an understanding of the mechanisms at work within schools in building collective teacher innovativeness, which have not been researched much so far. Through our analyses, it has thus been possible to shed some light on the black box of educational innovation and change (Blase & Björk, Citation2009) and to identify (some of) the underlying mechanisms, i.e. the nuts and bolts (Astbury & Leeuw, Citation2010; Weber, Citation2006) of educational innovation.

According to our results, the effect of school leader trust on collective teacher innovativeness is also mediated indirectly through school leaders’ explorative activities, which affect the school’s exploration, i.e. if school leaders trust their team of teachers, they are more likely to take risks and try new things themselves. This is in line with the literature, which suggests that trusting employees also has far-reaching consequences for the trustor in a leadership position and how they shape the work environment (Ladegard & Gjerde, Citation2014). In our view, the processes described above could be interpreted as a kind of feedback effect: because school leaders feel that they can trust their teachers, they themselves take risks and try new things, which is reflected in the (experimental) school culture and further reinforces the effect of school leaders’ trust in their teachers. Viewing school improvement as a dynamic process, these feedback loops could contribute to a continuous increase in the level of improvement and effectiveness of schools.

Thus, the concept of ambidexterity in the context of educational research – as suggested by Bingham and Burch (Citation2019) – can indeed help to identify vividly manageable levers for change in schools. In this regard, it is important to consider schools’ complexity. The micro-foundational perspective that we proposed offers a solid approach here, as it stresses the primacy of micro-foundations and highlights the role of individuals and groups’ actions and interactions as drivers for collective processes, results and outcomes (Felin & Foss, Citation2020). In this context, it will be necessary to take a closer look at the other actors and groups of actors in schools, i.e. teachers, as well as the interrelations between them across and within organisational levels, because organisations’ ambidextrous innovation requires that all organisational members contribute individualised management of exploration and exploitation (Gibson & Birkinshaw, Citation2004) across all organisational levels (Tarba et al., Citation2020).

In terms of Bingham and Burch’s (Citation2019) prescriptive guidance for how schools as organisations can manage educational change and respond to contextual pressures, our study has implications in several respects: for a theory of school improvement and change, for the practice of school improvement and change and for education policy and related frameworks for the training and professional development of teachers in general and school leaders in particular.

First, the findings of our study contribute to the further development of a theory of school improvement. Hargreaves (Citation2001) notes that such a

theory of school improvement needs concepts of knowledge creation, innovation and transfer for teachers to generate new forms of high leverage for better teaching…and to promote knowledge creation and transfer as new forms of intellectual excellence as outcomes for students … to prepare them for the innovativeness they need for successful lives in a knowledge economy. (p. 498)

Second, our findings contribute to the development of school improvement practice in schools: gaining insights into the mechanisms described above is of high relevance for fostering a work environment that is conducive to collective teacher innovativeness. Nonetheless, we see starting points at the school leader level. Within the scope of personnel management activities, reflections about their relationships with their teachers and the trust placed in them are conceivable. Supervision and coaching seem to be appropriate formats to be sensitised to the amount of trust and reasons for missing trust in the relationship. Besides, activities at the teaching team level seem to be suitable. Within the organisational development scope, teambuilding measures to increase trust might be helpful.

Third, our results have implications for education policy and its framework for optimising education and professional development of teachers. So, it is conceivable to start with regular teacher training, as in Germany, the basic teacher education is divided into two phases (Terhart, Citation2019): The first phase takes place at the university – interrupted by some internships lasting several weeks. Lectures and seminars teach the theoretical foundations of the teaching profession. In this phase it is conceivable to introduce trust as an essential component of successful school improvement and to sensitise the students to the link between trust and school improvement. The second phase of teacher training takes place in schools and so-called study seminars. This is where the trainee teachers’ practical experiences are reflected upon in a professional manner. Practical experience with (present or absent) trust could be linked to the influencing factors known from research and reflected in the importance of innovation.

The training of school leaders could also be an issue. In many German federal states, teachers who want to become school leaders would have to attend an additional preparatory course in which they are familiarised with the new organisational, administrative and legal tasks and conditions (Tulowitzki, Citation2015). This should also include learning about the importance of trust and its scope. Finally, in-service training can also be used for school leaders who have been in office for a long time. In Germany – and beyond – they are expected to continue their education in order to cope with the constantly changing challenges in schools. An important point in this context is that school leaders should be enabled to move from personalised trust through relational exchange to general intra-organisational trust in the teaching staff (Bormann et al., Citation2021; Nee et al., Citation2018), as such a kind of trust can be learned and trained through social experience (Risse & Börzel, Citation2015). In our view, special emphasis should be placed on this, given the central importance of school leaders for school improvement and change, and the fact that trust can also be learned by organisations as a whole through symbolic representations of individuals within the organisation (Luhmann, Citation1979).

In the end, it should be mentioned that our model explained 53 percent of the total variation in collective teacher innovativeness. These findings provide strong evidence regarding the positive relationship between school leader trust in teachers and collective teacher innovativeness in terms of teacher reciprocity, openness and willingness to adopt change, e.g. by developing new instructional ideas and ways of problem-solving, and by mutually supporting and implementing new ideas. However, other factors should be considered to explain the remaining percentage of collective teacher innovativeness, e.g. commitment or participation, which seem to be plausible as mediators in the relationship between school leader trust in teachers and collective teacher innovativeness. Thus, their influence might be investigated in future research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adams, C. M., & Miskell, R. C. (2016). Teacher trust in district administration: A promising line of inquiry. Educational Administration Quarterly, 52(4), 675–706. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X16652202

- Ainley, J., & Carstens, R. (2018). Teaching and learning international survey (TALIS) 2018 Conceptual framework (OECD education working papers no. 187). OECD. https://doi.org/10.1787/799337c2-en

- Akar, S. G. M. (2019). Does it matter being innovative: Teachers’ technology acceptance. Education and Information Technologies, 24(6), 3415–3432. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-09933-z

- Anderson, J. C., & Gerbing, D. W. (1988). Structural equation modeling in practice: A review and recommended two-step approach. Psychological Bulletin, 103(3), 411–423. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.103.3.411

- Anderson, N., & West, M. A. (1998). Measuring climate for work group innovation: Development and validation of the team climate inventory. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 19(3), 235–258. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1379(199805)19:3%3C235::AID-JOB837%3E3.0.CO;2-C

- Andersson, K., & Liljenberg, M. (2020). ‘Tell us what, but not how’ – understanding intra-organisational trust among principals and LEA officials in a decentralised school system. School Leadership & Management, 40(5), 465–482. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2020.1832980

- Andriopoulos, C., & Lewis, M. W. (2009). Exploitation-exploration tensions and organizational ambidexterity: Managing paradoxes of innovation. Organization Science, 20(4), 696–717. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1287orsc.1080.0406.

- Arar, K. (2020). School leadership for refugees’ education: Social justice leadership for immigrant, migrants and refugees. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429021770

- Argyris, C., & Schön, D. (1978). Organizational learning: A theory of action perspective. Addison-Wesley.

- Astbury, B., & Leeuw, F. L. (2010). Unpacking black boxes: Mechanisms and theory building in evaluation. American Journal of Evaluation, 31(3), 363–381. https://doi.org/10.1177/1098214010371972

- Augier, M. (2004). James March on education, leadership, and Don Quixote: Introduction and interview. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 3(2), 169–177. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2004.13500521

- Augier, M. (2018). March, James G. (Born 1928). In M. Augier, & D. J. Teece (Eds.), The Palgrave encyclopedia of strategic management (pp. 960–967). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-00772-8_642

- Beus, J. M., Jarrett, S. M., Bergman, M. E., & Payne, S. C. (2012). Perceptual equivalence of psychological climates within groups: When agreement indices do not agree. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 85(3), 454–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8325.2011.02049.x

- Bingham, A. J., & Burch, P. (2019). Reimagining complexity: Exploring organizational ambidexterity as a lens for policy research. Policy Futures in Education, 17(3), 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210318813269

- Birkinshaw, J., & Gupta, K. (2013). Clarifying the distinctive contribution of ambidexterity to the field of organization studies. Academy of Management Perspectives, 27(4), 287–298. https://doi.org/10.5465/amp.2012.0167

- Blase, J., & Björk, L. (2009). The micropolitics of educational change and reform: Cracking open the black box. In A. Hargreaves, A. Lieberman, M. Fullan, & D. Hopkins (Eds.), Second international handbook of educational change (pp. 237–258). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-90-481-2660-6_14

- Blömeke, S., Nilsen, T., & Scherer, R. (2021). School innovativeness is associated with enhanced teacher collaboration, innovative classroom practices, and job satisfaction. Journal of Educational Psychology, 113(8), 1645–1667. http://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000668

- Bormann, I., Niedlich, S., & Würbel, I. (2021). Trust in educational settings—What it is and why it matters. European Perspectives. European Education, 53(3-4), 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/10564934.2022.2080564

- Brix, J. (2019). Ambidexterity and organizational learning: Revisiting and reconnecting the literatures. The Learning Organization, 26(4), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/TLO-02-2019-0034

- Brower, H. H., Lester, S. W., Korsgaard, M. A., & Dineen, B. R. (2009). A closer look at trust between managers and subordinates: Understanding the effects of both trusting and being trusted on subordinate outcomes. Journal of Management, 35(2), 327–347. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206307312511

- Brower, H. H., Schoorman, F. D., & Tan, H. H. (2000). A model of relational leadership: The integration of trust and leader–member exchange. The Leadership Quarterly, 11(2), 227–250. http://doi.org/10.1016/S1048-9843(00)00040-0

- Bryk, A. S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement. Phi Delta Kappan, 91(7), 23–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/003172171009100705

- Bryk, A. S., & Schneider, B. (2002). Trust in schools: A core resource for improvement. Russell Sage.

- Bryk, A. S., Sebring, P. B., Allensworth, E., Easton, J. Q., & Luppescu, S. (2010). Organizing schools for improvement: Lessons from Chicago. University of Chicago Press.

- Busco, C., Riccaboni, A., & Scapens, R. W. (2006). Trust for accounting and accounting for trust. Management Accounting Research, 17, 11–41. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mar.2005.08.001

- Buske, R. (2018). The principal as a key actor in promoting teachers’ innovativeness – Analyzing the innovativeness of teaching staff with variance-based partial least square modeling. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 29(2), 262–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1427606

- Buyukgoze, H., Caliskan, O., & Gümüs, S. (2022). Linking distributed leadership with collective teacher innovativeness: The mediating roles of job satisfaction and professional collaboration. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432221130879

- Byun, G., Dai, Y., Lee, S., & Kang, S. (2017). Leader trust, competence, LMX, and member performance: A moderated mediation framework. Psychological Reports, 120(6), 1137–1159. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033294117716465

- Cao, Q., Gedajlovic, E., & Zhang, H. (2009). Unpacking organizational ambidexterity: Dimensions, contingencies, and synergistic effects. Organization Science, 20(4), 781–796. http://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1090.0426

- Chams-Anturi, O., Moreno-Luzon, M. D., & Escorcia-Caballero, J. P. (2020). Linking organizational trust and performance through ambidexterity. Personnel Review, 49(4), 956–973. https://doi.org/10.1108/PR-07-2018-0239

- Chams-Anturi, O., Moreno-Luzon, M. D., & Romano, P. (2022). The role of formalization and organizational trust as antecedents of ambidexterity: An investigation on the organic agro-food industry. BRQ Business Research Quarterly, 25(3), 243–264. https://doi.org/10.1177/2340944420966331

- Chandler, G. N., Keller, C., & Lyon, D. W. (2000). Unraveling the determinants and consequences of an innovative-supportive organizational culture. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 25(1), 59–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/104225870002500106

- Cohen, D. K., Spillane, J. P., & Peurach, D. J. (2018). The dilemmas of educational reform. Educational Researcher, 47(3), 204–212. http://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X17743488

- Coleman, J. (1990). Foundations of social theory. Harvard University Press.

- Colquitt, J. A., LePine, J. A., Zapata, C. P., & Wild, R. (2011). Trust in typical and high-reliability contexts: Building and reacting to trust among firefighters. Academy of Management Journal, 54(5), 999–1015. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.0241

- Colquitt, J. A., Scott, B. A., & LePine, J. A. (2007). Trust, trustworthiness, and trust propensity: A meta-analytic test of their unique relationships with risk taking and job performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92(4), 909–927. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-9010.92.4.909

- Cosner, S. (2009). Building organizational capacity through trust. Educational Administration Quarterly, 45(2), 248–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08330502

- Cunningham, J. B., & MacGregor, J. (2000). Trust and the design of work complementary constructs in satisfaction and performance. Human Relations, 53(12), 1575–1591. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013161X08330502

- Da’as, R. A. (2021). The missing link: Principals’ ambidexterity and teacher creativity. Leadership and Policy in Schools. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/15700763.2021.1917621

- Da’as, R. A. (2022). Principals’ attentional scope and teacher creativity: The role of principals’ ambidexterity and knowledge sharing. International Journal of Leadership in Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2022.2027525

- Damanpour, F. (1996). Organizational complexity and innovation: Developing and testing multiple contingency models. Management Science, 42(5), 693–716. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.42.5.693

- Dietz, G., & Hartog, D. N. D. (2006). Measuring trust inside organisations. Personnel Review, 35(5), 557–588. https://doi.org/10.1108/00483480610682299

- Distel, A. P. (2019). Unveiling the microfoundations of absorptive capacity: A study of Coleman’s Bathtub model. Journal of Management, 45(5), 2014–2044. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920631774196

- Dulebohn, J. H., Bommer, W. H., Liden, R. C., Brouer, R. L., & Ferris, G. R. (2012). A meta-analysis of antecedents and consequences of leader-member exchange integrating the past with an eye toward the future. Journal of Management, 38, 1715–1759. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311415280

- Duncan, R. (1976). The ambidextrous organization: Designing dual structures for innovation. In R. H. Kilman, L. R. Pondy, & D. Slevin (Eds.), The management of organization (pp. 167–188). North-Holland.

- Edmondson, A. C., Bohmer, R. M., & Pisano, G. P. (2001). Disrupted routines: Team learning and new technology implementation in hospitals. Administrative Science Quarterly, 46(4), 685–716. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094828

- Eisenhardt, K. M., Furr, N. R., & Bingham, C. B. (2010). Microfoundations of performance: Balancing efficiency and flexibility in dynamic environments. Organization Science, 21(6), 1263–1273. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.1100.0564

- Ernst, C., & Yip, J. (2009). Boundary-spanning leadership: Tactics to bridge social identity groups in organizations. In T. Pittinsky (Ed.), Crossing the divide: Intergroup leadership in a world of difference (pp. 87–99). Harvard Business Publishing.

- Farrell, A. M. (2010). Insufficient discriminant validity: A comment on Bove, Pervan, Beatty, and Shiu (2009). Journal of Business Research, 63(3), 324–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2009.05.003

- Felin, T., & Foss, N. J. (2020). Microfoundations for institutional theory? Research in the Sociology of Organizations, 65, 393–408. https://doi.org/10.1108/S0733-558X2019000065B031

- Felin, T., Foss, N. J., & Ployhart, R. E. (2015). The microfoundations movement in strategy and organization theory. Academy of Management Annals, 9(1), 575–632. http://doi.org/10.1080/19416520.2015.1007651

- Fornell, C., & Larcker, D. F. (1981). Evaluating structural equation models with unobservable variables and measurement error. Journal of Marketing Research, 18(1), 39–50. https://doi.org/10.2307/3151312

- Fotheringham, P., Harriott, T., Healy, G., Arenge, G., & Wilson, E. (2022). Pressures and influences on school leaders navigating policy development during the COVID-19 pandemic. British Educational Research Journal, 48(2), 201–227. http://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3760

- Fullan, M. (2016). The new meaning of educational change. Teachers College Press.

- Fulmer, C. A., & Gelfand, M. J. (2012). At what level (and in whom) we trust: Trust across multiple organizational levels. Journal of Management, 38(4), 1167–1230. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206312439327

- Gibson, C. B., & Birkinshaw, J. (2004). The antecedents, consequences, and mediating role of organizational ambidexterity. Academy of Management Journal, 47(2), 209–226. https://doi.org/10.5465/20159573

- Gibson, C. B., Birkinshaw, J., McDaniel Sumpter, D., & Ambos, T. (2019). The hierarchical erosion effect: A new perspective on perceptual differences and business performance. Journal of Management Studies, 56(8), 1713–1747. https://doi.org/10.1111/joms.12443

- Gibson, C. B., Cooper, C. D., & Conger, J. A. (2009). Do you see what we see? The complex effects of perceptual distance between leaders and teams. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94, 62–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013073

- Grissom, J. A., Egalite, A. J., & Lindsay, C. A. (2021, February). How principals affect students and schools: A systematic synthesis of two decades of research. Wallace Foundation. https://www.wallacefoundation.org/knowledge-center/Documents/How-Principals-Affect-Students-and-Schools.pdf.

- Gupta, A. K., Smith, K. G., & Shalley, C. E. (2006). The interplay between exploration and exploitation. Academy of Management Journal, 49(4), 693–706. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.22083026

- Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis: A global perspective. Pearson Education.

- Hallinger, P. (2011). Leadership for learning: Lessons from 40 years of empirical research. Journal of Educational Administration, 49(2), 125–142. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231111116699

- Hallinger, P. (2016). Bringing context out of the shadows of leadership. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 46(1), 5–24. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143216670652

- Handford, V., & Leithwood, K. (2013). Why teachers trust school leaders. Journal of Educational Administration, 51(2), 194–212. https://doi.org/10.1108/09578231311304706

- Hargreaves, D. H. (2001). A capital theory of school effectiveness and improvement. British Educational Research Journal, 27(4), 487–503. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920120071489

- Harman, H. H. (1960). Modern factor analysis. University of Chicago Press.