ABSTRACT

Democracies expect citizens to engage actively in public life by making decisions about political issues that are frequently ambiguous, with strong moral and emotional implications, and often subject to misinformation and manipulation. Strong critical thinking (CT) appears therefore as a crucial component of a reflective democratic citizenship. This study identifies sociopolitical topics that are relevant to secondary Portuguese students and explores the interplay between emotions and cognition in their moral-political decision-making. Participants in two rounds of focus group discussions were asked to choose one sociopolitical topic and to report their emotions about that topic; in the second round, they discussed an ethical-moral dilemma about the most selected topic. The students’ emotions selection and their verbal explanations revealed that topics related to refugees, animal rights and environmental issues were the most engaging ones. The dilemma about refugees showed that a strong emotional engagement can lead to higher levels of conflict and that emotional ambivalence can have positive effects on CT. We conclude that pedagogical activities to educate critical citizens should explore social, humanitarian, and environmental issues, encouraging the expression of emotional ambivalence as a precursor to cognitive-moral conflict that is important to a truly engaging and reflective democratic citizenship education.

Introduction

Democratic societies require citizens to engage actively in political decision-making. This type of active citizenship implies that citizens position themselves between different options (Irvin & Stansbury, Citation2004) that, in many cases, involve a strong emotional component and demand making moral judgements. Since moral arguments are often used to manipulate citizens’ political opinions (Bakker et al., Citation2020), it becomes crucial that citizens base their decisions on the critical scrutiny of the available information and on how their own emotions and moral values may influence their decision-making processes. In this light, many democratic institutions claim that they seek to empower citizens by developing their critical thinking (CT) skills (Jennings et al., Citation2006), towards a model of critical democratic citizenship (Bartels et al., Citation2016; Council of Europe, Citation2016). This intention is backed by theoretical models of citizenship that increasingly advocate for the critical engagement of citizens with political decisions (Veugelers, Citation2007; Westheimer & Kahne, Citation2004). At the same time, empirical studies about citizens’ conceptions of democratic politics also confirm that, especially younger generations, see CT skills as crucial elements for political participation, that should be developed in school (Mathé, Citation2016).

CT is largely seen as a “reasonable reflective thinking focused on deciding what to believe or do” (Ennis, Citation1996, p. 166), that includes dispositions to mobilise specific cognitive (Facione, Citation1990) and metacognitive skills (Kuhn, Citation1999) when treating external information and personal knowledge that will shape personal opinions about a specific topic. Although this definition is not consensual, it reflects a general tendency to view CT as being almost exclusively determined by cognitive activity, preferably, freed from the disturbance of emotions. This is in part because affect is still seen by some as being associated with lower quality decision-making (Redlawsk, Citation2002). Although the complexity of the connections between cognitive and affective dimensions in decision-making processes needs further exploration (Lerner et al., Citation2015), the literature shows that cognition and emotions are deeply intertwined (Cohen, Citation2005; Damásio, Citation2003), that emotions can have a beneficial effect on reasoning and the quality of CT (Holma, Citation2015; Luo & Yu, Citation2015) and that there is a bidirectional influence of affective responses and cognitive skills over moral decisions (Van Den Bos, Citation2007) and political attitudes (Norris et al., Citation2003). The dual process model (Greene et al., Citation2008), for instance, proposes that cognition and emotions compete for priority in shaping moral judgements. Accordingly, this could lead to utilitarian or deontological (Gawronski & Beer, Citation2017) outcomes in moral decisions, with emotional responses usually resulting in deontological judgements while utilitarian judgements are usually associated with controlled cognitive processes (Greene, Citation2009). Therefore, democratic citizenship education (Pinto & Portelli, Citation2009) models should recognise the significant influence that emotions can exert over moral decision-making (Hoffman, Citation2000) and sociopolitical behaviour (Brader & Marcus, Citation2013) and action (Huebner et al., Citation2009).

This close connection between emotions, moral decision-making, CT and democratic citizenship, raises the important question of how can education help students to be critical citizens who feel civic and politically empowered to take social action when they perceive morally unjust situations? Since schools are pivotal institutions for CT development and citizenship education, emotions also need to be recognised as crucial in these educational processes (Shultz & Pekrun, Citation2007). More knowledge is needed about how emotions affect interactions in the classroom, especially since they seem to influence both the structure of knowledge and the process of learning alike (Moon, Citation2008). This can help teachers to better understand students’ behaviour and motivation to learn (Ratner, Citation2007), which, in turn, can help to achieve a model of critical citizenship education including pedagogical activities that require high levels of cognitive commitment from the students (Tsui, Citation2002).

Additionally, emotions can foster the students’ critical awareness about cases of social injustice against others, which is especially important in developing an inclusive and democratic model of citizenship (DeJaeghere, Citation2009). This awareness can be aided by positive social emotions, such as empathy, that can increase the students’ “ability to recognize and understand the feelings of others” (Alexander & Sandhal, Citation2016, p. 57) when facing discrimination. Empathy can help students to imagine themselves in similar situations and to understand how discriminatory behaviour can affect others, which is crucial to the education of inclusive and democratic citizens that are capable of “thinking within the viewpoints of others” (Paul & Elder, Citation2005, p. 34). Other emotions, usually described as negative, can also play a significant role in shaping citizens’ political attitudes. Anger and fear are two of the emotions that can significantly influence citizens’ political opinions and behaviour (Van der Does et al., Citation2021), especially regarding sociopolitical issues that involve a moral position about values of (un)fairness and (in)equality (Rutland et al., Citation2010), that can potentially sustain prejudice and social discrimination (Shepherd et al., Citation2017). Since the political outcomes resulting from the experience of positive and/or negative emotions can vary significantly according to the context in which these emotions are experienced (Mesquita & Boiger, Citation2014), the creation of safe spaces in schools for the expression and debate of these emotions is crucial for democratic citizenship education.

In fact, studies about critical models of democratic citizenship education have identified CT as a crucial element to deconstruct prejudice (Bennett & Pidcock, Citation2014) and to help citizens adopt specific moral values, like freedom or respect for ethnical and cultural diversity (Paul, Citation2000). Indeed, it has long been argued that critical reflections about citizenship “ought to be conditioned by the themes of democracy, dignity, and diversity” (Beane, Citation1990, p. 130). Although it is crucial that CT about any topic is not directed or intentionally skewed and that it welcomes and encourages the discussion of different opinions about that topic (Hedtke, Citation2016; Ribeiro et al., Citation2017), while making clear that CT “does not imply that some final truths can be reached” (Holma, Citation2015, p. 20), this does not mean that CT should be “value-neutral” (Pinto & Portelli, Citation2009, p. 300) and should not prevent teachers from making the importance and merits of certain moral (respect, equality, freedom) and political (democracy) values clear to their students (Quantz, Citation2015).

But how can critical citizenship education influence citizens’ moral and political values towards more agonistic (Mouffe, Citation2014), inclusive, humanistic (Veugelers, Citation2011) and democratic societies? Although research has demonstrated that pedagogical activities such as interactive discussions (Abrami et al., Citation2015), debates (Healey, Citation2012) and mock elections (De Groot, Citation2017) can be effective in educating critical citizens, less research has been done to identify specific topics to be approached in these activities. Studies that show that these activities should preferably focus on controversial issues (Mead & Scharmann, Citation1994), to promote cognitive conflict in the participants (Gronostay, Citation2016), do not explore the potential of what Horst Rittel and Melvin Webber (Citation1973) called “wicked problems” in CT and moral development. “Wicked problems” address “thorny issues” (Pinto & Portelli, Citation2009, p. 304) that are usually characterised by a significant level of ambiguity (Whyte & Thompson, Citation2012) and to which different perspectives and solutions can be equally plausible depending on the frame of reference used to approach them (Ludwig, Citation2001). In this paper, departing from the work of Termeer et al. (Citation2019), we consider “wicked problems” as elements of particular sociopolitical topics that, by their inherent complexity and ambiguity, can generate conflict (emotional, moral, cognitive), pushing people to consider these problems from different perspectives. In this paper, we show how some “wicked problems” with which the European Union (EU) is currently confronted can help to explore the role played by emotions in students’ critical engagement with specific sociopolitical issues, bringing light to how emotions influence the students’ thinking and moral decision-making about these problems.

We start by finding which emotions students associate to given sociopolitical topics, which cognitive strategies they use to analyse their own emotions, and if there is a connection between these emotional responses and the students’ motivation to participate in activities that promote collective critical reflection. Following previous research that indicates that moral dilemmas are a valuable tool for assessing moral cognition (Blatt & Kohlberg, Citation1975; Christensen & Gomila, Citation2012; Rest et al., Citation1974), we then use the results of a moral dilemma about one of these topics to understand how students cognitively deal with their own emotional connections with this topic and how these connections influence their moral decision-making processes and their views about “wicked problems” in contemporary EU policy.

Materials and methods

This study consisted of a set of two focus group discussions in each one of the participating schools, conducted before and shortly after (May and June) the 2019 European Parliament election. This schedule allowed us to see how political debates during the campaign for the elections influenced the opinions of the participants in the focus groups about some of the most “wicked problems” in the EU. The 35 participants were upper secondary (grades 10–12) students attending four Portuguese schools located in the Northern part of the country. The selection represents both regular (schools #1, #2 and #3) and vocational (school #4) education, as well as middle/high (schools #2 and #3) and lower (schools #1 and #4) socioeconomic backgrounds. The socioeconomic characterisation of schools is based on the percentage of students supported by social funds in previous years, as well as in the economic resources of the surrounding community.

A group of 6–11 students was selected by each school. These groups included participants enrolled in Humanities and Sciences, for regular tracks, and in different courses available in vocational education. The discussions were guided by a script that explored which European issues were more important for the participants and how they believe they should be addressed by the EU. The script also included the administration of the Geneva Emotion Wheel (GEW, Scherer, Citation2005), in the first session, and the presentation of a moral dilemma, in the second session. All the students’ names included in this paper are fictitious.

Data analysis involved descriptive statistics for the quantitative data, and content analysis of the qualitative data. To ensure the rigour of the analysis, verification strategies including iterative and interactive validation checks involving the various authors were performed (Morse et al., Citation2002), using observer triangulation, peer debriefing and reflexivity (Lietz & Zayas, Citation2010).

The GEW

Considering that “self-report is an indispensable method to assess human emotions” (Pekrun, Citation2016, p. 44), we decided to use a translated to Portuguese version of the GEW (Scherer, Citation2005). This data collection tool includes a set of 20 emotions that can vary in intensity from 1 (low intensity) to 6 (high intensity).Footnote1 Additionally, the participants could also choose to report not having any emotion or to specify an emotion that was not included in the set. The GEW was applied based on 10 photographs that were displayed in the room where the discussion would take place. These photographs were displayed before the participating students came into the room and without descriptions. Each photograph represented a sociopolitical topic that would probably be up for public discussion at the time and that illustrates “wicked problems” in contemporary EU policy: the refugee crisis; animal rights; environmental issues; democratic processes and Brexit; protests like the Yellow Vests in France, and the pro-independence demonstrations in Catalonia; other forms of civic and political engagement. The participants were then asked to choose one image and fill the GEW according to what they were feeling. Each participant was subsequently requested to verbally explain his/her choices and personal connections to the topic before the group discussion was initiated.

We performed a mixed analysis of the data that allowed us to compare the image and emotions selection with the verbal explanations of each participant. Taking into consideration that language is deeply connected with the ways in which young people “use ‘emotional repertoires’ to make sense of the world they live in” (Zembylas, Citation2012, p. 200), we used a content analysis of the students’ explanations about their selections which would allow us not only to look into the personal cognitive strategies they used to deal with their emotions, but also to clarify the role that those emotions may have in their political engagement with these topics.

The dilemma

Since previous research shows that “moral judgments of hypothetical real-life moral dilemmas provide the cognitive scientist with valuable insight into the foundational psychological processes that underlie human moral cognition” (Christensen & Gomila, Citation2012, p. 1250), we decided to confront the participants with a moral dilemma about the topic that most students selected in the GEW activity. Inspired by Rest et al. (Citation1974) and Kohlberg’s (Citation1975) research, the original dilemma was written in a way that would provoke a moral conflict among the participants:

Now imagine that you know a man called Antonio. He is a fisherman, married and has two small children. Although many of his colleagues complain that fishing in the area doesn’t allow them to survive anymore, Antonio usually makes small donations to a local association that helps refugees to integrate in the community and, more recently, bought a new car.

One day, while you are walking on the beach, you see Antonio’s boat approaching. When it gets close to land, you see dozens of people getting out of the boat and trying to hide as soon as they reach the beach. Clearly Antonio’s boat should not be carrying so many people and you notice that some of them seem to be crying. This image intrigues you, so later you decide to talk to Antonio about what you have seen. Alone with him, Antonio confesses that he has been illegally transporting refugees in his boat, justifying it with the need to make more money than what fishing can provide. You ask him why some of those people were crying and Antonio admits that some of them had to leave family members behind because they could not afford to pay for their trip. While both of you are talking, one of the people that Antonio transported approaches you and thanks Antonio for getting him/her to Europe. As soon as the person walks away, Antonio asks you not to report him to the authorities. Do you report Antonio to the authorities?

Since some of the participants in the first focus group session were not able to join the second session, only a total of 25 students addressed this dilemma. Participants were informed that there were no right or wrong answers, but they were asked to explain the reasons for their option. During this explanation, each group engaged in a discussion about different arguments supporting either decision. To compensate for group bias, whenever there was unanimity, the moderator told the group that colleagues in other schools had chosen the opposite option. Both the final choices made by the students and their explanations were recorded and subject to a statistical and content analysis. In order to better understand the impact that their emotions had in their decisions, we decided to compare the arguments of students who had chosen the topic of refugees in the GEW activity with the explanations of students who had chosen other topics.

Results

Feeling and deciding about moral-political issues

As shown in , image 1 (refugees) was the one that most students chose in the GEW activity, followed by image 8 (Muslims and terrorism) and images 2 (animal rights) and 3 (environment). On the other hand, images related to Brexit and Catalonia independence protests were not chosen by any participant. These results indicate that topics like the refugee crisis and terrorism seem to be the most interesting and emotionally engaging for the participants, followed by issues related with animal rights and climate change.

Table 1. Image selection.

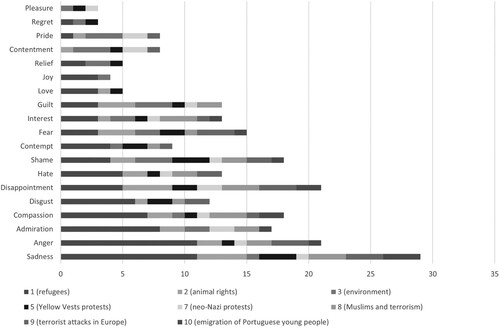

The participating students selected 19 out of the 20 emotions included in the GEW emotion set. In fact, the only emotion that none of the students selected was amusement. The emotion selected by most students was sadness, followed by disappointment and anger, and the least selected emotions were pleasure and regret. None of the students reported the absence of emotion and three felt the need to choose an emotion that was not included in the set of emotions given, describing feeling “revolt”, “concern” and “pity”, when looking at images 1, 3 and 5 respectively.

illustrates the emotions students associated with each image. Regarding image 1 (refugees) the emotions (sadness, anger, compassion, and admiration) already hint at a generally positive attitude of these students regarding refugees and a significant level of interest and empathy regarding their situation. As for image 8 (Muslims and terrorism), the findings (interest, sadness, disappointment, and anger) suggest that students have an ambivalent view regarding the common association between terrorist threats and the Muslim culture. In the case of image 2 (animal rights), all the students that chose this image associated it with sadness, fear, and guilt. Finally, in the case of image 3 (environment), students also report mixed feelings: altogether, students who chose this image are supportive of actions that aim at forcing political action against climate changes (hence the feelings of pride and contentment), while still recognising their own responsibility in the creation of social circumstances that led to current environmental issues (guilt and shame).

Considering that the topic “refugees” was the one that most participants selected in the GEW activity, the students were confronted with a moral dilemma about this topic. Although most participants admitted finding it difficult to reach a decision while facing such a conflicting dilemma, shows that there was a virtual in-group unanimity regarding whether to report Antonio to the authorities. This was especially valid for schools #1 and 4, while in schools #2 and 3 some students initially broke that consensus. In school#2, for instance, three students started by stating that they would not report Antonio (against five students who would). These three students would later change their decision when they remembered that Antonio had bought a new car, which, according to them, proved that Antonio was transporting the refugees simply because of greed. also shows that students from middle/high socioeconomic environments tended to choose to report Antonio to the authorities, while students from lower socioeconomic backgrounds chose not to report him.

Table 2. Participants’ choices in the dilemma.

Thinking critically about moral-political issues

The analysis of the discourses of the participants who chose image 1 seems to confirm a significant level of empathy regarding the situation of the refugees who try to reach Europe. This general feeling of empathy is often associated with negative feelings of anger, sadness and disappointment regarding the conditions that led to their situation and what they perceive as unsatisfactory action of several European countries. Simultaneously, these students also associated their empathic connection with the refugees’ situation with positive feelings of admiration and compassion.

I felt anger, admiration for those people who bring the entire family, children, pregnant women, etc., in boats in which they may die because their carry too many people. Compassion and sadness for them, for being in that situation. Disappointment because they are not as well received as they probably should be, and anger also because of that. (Iva, School#1)

In line with a previous study about the perceptions of Portuguese students regarding refugees (Piedade et al., Citation2021), and with a significant part of public debate surrounding these issues, the participants who chose image 1 also established connections between these migratory movements and a potential increase in the risk of terrorist attacks in the European countries which welcome refugees. While thinking about these issues, most participants were inclined, however, towards a humanitarian position, deconstructing common assumptions and prejudiced statements often used to justify a securitarian approach to these topics.

What I felt was sadness and compassion because I put myself in those people’s shoes when they come from other countries and try to fit in a country that they don’t know. And anger in the sense that that is a little revolting because, again, I put myself in their shoes and I think that I would also find it difficult to fit in in a society that, in many cases, does not think well of me. […] they are mistaken with terrorists and people forget that many of those who come here are doctors, attorneys … they had good jobs in their own country, and they come here and have nothing. It’s basically starting everything from scratch. And I also felt admiration because of that. (Valentina, School#1)

The image mainly made me feel admiration because of the sacrifices that those people have to make because of the attacks they endure in their own land. Contempt and hate because of the attacks in their own countries, I don’t think that it is human at all. Disappointment also because of that. And sadness because of what they have to go through. They have to abandon their lives. Risk their own lives to get here, and many of them don’t even make it. (Alberto, School#2)

I selected sadness because I think that it’s very sad that someone has to feel threatened in their own country and is not able to live their normal lives. […] I think a person has to be really desperate to risk their own life and the lives of their children. Because most of them come here to provide a better life for their family. I selected anger because there are still wars and movements that lead to these displacements. And I have selected admiration for the struggle that these people carry on daily. And for the courage that they have to undergo such a radical change in their lives. (Helena, School#2)

I associate this image with the refugees coming to Europe and felt a lot of sadness for the fact that so many people feel the need to leave their own country because of wars and attacks. And I believe that, as a major power and privileged for living in Europe, we should welcome them, it is our duty. (Elsa, School#2)

I feel anger, repugnancy, shame, guilt and sadness because I believe it is our problem, caused by us. Many countries live off on selling weapons. […] I believe that we are guilty and that we do not care enough. And I think that we are looking at the problem from the wrong angle. We are trying to solve this upon their arrival when, maybe, we should try to solve it in a diplomatic and humanitarian way, in the countries in which these problems are occurring. And that is why they are coming here. I’ve checked another feeling that is not here, which is revolt. I added it for the same reasons. (Duarte, School#3)

One of the students who chose image 1 was even more specific when it came to the EU’s responsibilities regarding these international issues. In line with virtually all the other participants who chose this image, this student associated feeling negative emotions of disappointment, shame and repugnancy when he thought about the EU’s actions towards solving these problems. This general disappointment with European policies is also usually associated with other negative emotions, such as hate and anger, regarding all those who take advantage of the situation and of the vulnerability of the refugees.

I feel disappointed with the EU. An institution that is so well regarded, that talks about fraternity and human equality so much, but that is not doing its best – I don’t think that they’re doing their best – but the bare minimum to solve this problem. I don’t see a real interest. Repugnancy because this – I’m sorry about this word – but it is something that sickens me. And hate and anger. I feel hate, once again, for people who take advantage of these vulnerable human beings that deserve so much more than what they have now. (Lucas, School#3)

From all the emotions that I felt, anger was the main one. Because it angers me to see people like that! When they can’t do anything for themselves and all they can do is run away. […] It makes me feel hate. It makes me feel contempt. Not contempt in the sense that I despise that, but for the fact that those people who could help feel contempt and simply do not care. “Go your own way and live your lives somewhere else”. I feel pride for that person there holding his children […] I feel love for that image. Because it really moves me. And admiration. And I fear that one day it might happen here. Or that it may happen to someone close to me or to my family. You never know. We are never really safe from that, right? (Ivete, School#4)

Most of the participants showed the ability to imagine themselves and their families in the same scenarios as the refugees. This, combined with the positive emotions of admiration and compassion that they reported feeling for the refugees, led to an almost consensual empathy, even when they acknowledged the potential risks that welcoming more refugees might imply. In fact, the relative low levels of fear might be due to the fact that they generally dismissed a causal link between the entrance of refugees into European space and the occurrence of terrorist attacks, as shown in the following statement.

The admiration and compassion are also at the highest level because I also think that it takes a lot of courage from those people to abandon their homes like that and to cross the Mediterranean in a rubber boat, with very little hope for their lives. The compassion is also connected with guilt, I believe that, since we are also guilty, we have the obligation to feel compassion for the suffering of those people. […] But those people need our humanitarian aid because they are facing a serious problem in their countries. And fear, I have marked it at the lowest […] although they are from another culture, I don’t think that it is them who come here to carry out terrorist attacks. (Duarte, School#3)

This does not mean, however, a complete absence of fear amongst the participating students when they think about these issues. Although some students who chose image 8 (Muslims and terrorism) displayed a similar empathetic discourse towards the refugees, as visible in the following account:

I felt compassion because I feel pity for those people and I would like to help them, so I filled the largest circle. I also chose admiration because they are in places in which there is war and they still have the willpower to leave and to fight for a life with better conditions, in spite of all the prejudice. I chose anger because it angers me. And I’ve chosen guilt because I believe that the reason why they cannot have a better life is also our fault. But I’ve marked guilt in the smaller circle because it’s not my fault. It is everyone’s fault [laughter]! (Ana, School#1)

They convey that idea that ISIS is not a part of the Islamic religion. They claim that one thing has nothing to do with the other. And hence my contempt, not only for that religion as a whole, the Islamic religion, but also for what they are doing. (Moisés, School#4)

Although this difference in the opinions of students should be expected and used to open a critical discussion about a specific topic, what was even more interesting and surprising were the ways in which many of the students who chose image 8 tried to identify and deconstruct their own prejudiced views about cultural and religious differences. Some of these students reported feeling emotions of shame and guilt stemming from their own prejudices.

Because I don’t like prejudice. I also have my own prejudices too, obviously. Like we all do. But lately I’ve been trying to change that, so that I’m not prejudiced against other people. For this image I’ve chosen sadness, shame, disappointment, and also a little of guilt because, like I’ve said, I’m also prejudiced. We all are. And I feel guilty for that. (Eduardo, School#2)

A little bit of guilt because the current discrimination against Muslims, in fact, is because Europeans put everyone in the same bag and think that every Muslim is a terrorist. So, it’s also our fault. Also shame because there is a lot of people who believe that. And also a little bit of compassion for Muslims in general. (Valdemar, School#2)

Finally, this image has also led one of the students to confess his admiration for Muslim cultural characteristics, while also raging against prejudice towards Muslims and other minorities in European countries. Interestingly, this student, although he did not include fear in the emotions he felt while looking at image 8, mentioned feeling fear when thinking about far-right movements that spread xenophobic rhetoric against Muslims in several European countries.

I’m very interested in the Muslim culture. I think it’s a beautiful culture and that it is hugely underrated in our society. And I think that they suffer with prejudice. Like many other minority groups in Europe, like black people, etc., they have to deal with a lot of prejudice. I think that should change. […] And I fear extremist movements from the far-right. Because I’ve read some things on Twitter about the return of the Crusades. Which I find completely absurd. […] And I believe that a person who says that has absolutely no idea about what is going on in the world. (Filipe, School#2)

The situations of refugees led to the expression of stronger emotions that, in case of negative emotions (anger, sadness, disappointment), seem to be connected with a clash between sociopolitical actions and moral values. To understand how these emotional connections influenced their moral decision-making processes, the students were confronted with the dilemma. This activity revealed that students in vocational tracks and lower socioeconomic contexts differ from their colleagues in regular tracks and middle/high socioeconomic environments (the former choosing mostly to report Antonio to the authorities, while the latter chose not to do so), even if the majority of students in both groups displayed some level of empathy regarding the refugees’ situation. However, students in both groups used different cognitive and emotional strategies to deal with the moral conflict.

Some students in the first group based their decision to report Antonio on deontological-humanitarian and highly emotional arguments that confirm a significant level of empathy towards the refugees.

But when [refugees] are already here what are we going to do? Send them away again? That would be inhuman. […] Because [Antonio] is doing a good thing, although he is doing it for his own good. But it’s still a good thing. (Cristina, School#1)

I feel bad about reporting Antonio because then those people wouldn’t come here. But Antonio is being stupid. […] I would need to have a longer conversation with him.

Moderator: What would you need to know in order to decide?

Ana: What happens to those people afterwards. If they end up homeless […] I would need to hear a refugee’s perspective. (Ana, School#1)

I’m not even saying that he [Antonio] should do it for free. But the children, for instance … it’s really bad for a mother to have to leave her children behind. […] [Antonio] is doing it to make money, that’s for sure. But, at the same time, he is also helping them [refugees]. Let’s say that it is a 50/50 situation. (Ivete, School#4)

We’re already being invaded by tourists. Now we would also be invaded by refugees. […] I think it’s stupid for them [refugees] to be stealing jobs from people who are already here! From our own country. And giving those jobs to people who come from abroad. […] If we let hundreds and hundreds of refugees come here, like you are saying, and if they are really good and we are only good, then the Portuguese would be swept aside and we would be the refugees. (Ivete, School#4)

Other students in Ivete’s group, that had not reported such strong and contradictory emotions regarding the refugees, did not seem to face the same difficulties. In fact, the only three students that reported finding no moral conflict in the situation presented in the dilemma were in this discussion group. In their views, Antonio was doing nothing wrong, and his actions were simply helping him, his family, his country and the refugees as well.

He [Antonio] is bringing money into the country. Even if he can’t pay taxes, because he would be caught doing illegal trading. I think that it would be good for him, at least. He is dealing with the situation and I believe that those people [the refugees] have every right to come here. […] I think [Antonio] can think more about the money than about the refugees’ issue. Just as long as he helps them. […] I believe that is much more important than hiring people simply because of their nationality, and not because of their skills, since [an employer] could have a better worker, only with the small detail of being a refugee. Which is simply prejudice. (Ivan, School#4)

Students in the second group (regular tracks and middle/high socioeconomic backgrounds) followed a similar pattern. Like in the first group, although the final decision to the dilemma was consensual, there was a significant heterogeneity in the moral grounds that supported the decision to report Antonio. Students who had chosen the refugees’ topic in the GEW activity split between those who based their decision on deontological-humanitarian arguments (like Helena), and those who, in spite of their emotional connection to the topic, supported a utilitarian approach to the dilemma with more rational arguments (like Duarte).

He’s [Antonio] thinking “the more money I make, the better”. But I think that I would report him too. In part because of that. Because he wasn’t looking for the well-being of the people he was transporting. (Helena, School#2)

The problem is that we should be doing this legally. Through the proper channels. For instance, a cooperation system for asylum seekers was just approved by the EU. A system in which we check if anyone has a criminal record. Why? Because if you are bringing them [refugees] illegally, you don’t know if they are coming to work or to do something else. […] I’m not saying that all immigrants are terrorists. They [terrorists] would find other ways to come here, I’m sure. […] Our problem is not with them coming. It’s with them coming illegally. (Duarte, School#3)

If I was where they are, maybe I would also want to come to Portugal. […] it’s easy because I have my bed and wake up in the morning with my breakfast on the table. Right? They don’t have that. And they are going to have to wait a long time and maybe even be poorly treated. (André, School#2)

So, I think I would report [Antonio]. Although it’s a shame and it would hurt me to do it. Because he is helping but bringing lots of problems that could be avoided if it was done legally and well organized. It’s like I have said before, it has to be organized. (André, School#2)

The issue here is that [Antonio] is bad. He brought them illegally. He doesn’t know who they are and took advantage of their situation to make more money […] But, on the other hand, he brought them. He saved them from the conflict. […] He had a good and a bad gesture. (Andreia, School#3)

Unless you find a faster way to act … then, its ok. […] If so, that’s ok. Because currently to leave Syria, or anywhere else, and come here … it is not acceptable the time they have to wait. (Andreia, School#3)

In general, students who were torn between deontological-humanitarian and utilitarian arguments seemed to be more willing to resort to specific cognitive skills, such as contrasting and analysing different opinions in order to resolve their moral conflict.

Discussion

The findings presented in this paper show that sociopolitical topics related to the situation of refugees, terrorism, animal rights and the environment trigger strong emotional responses that motivate the students to critically reflect about their implications. However, issues concerning the migratory flows towards the EU were the most appealing and emotionally engaging. Albeit the specific context in which the data was collected, before and shortly after the 2019 European Parliament elections, might have influenced the relevance given by the participants to each topic, the issue of refugees is, as the recent war in Ukraine has unfortunately revealed, once again at the core of European life.

Like in the case of Greek-Cypriot youth (Zembylas, Citation2012), our study also suggests the existence of emotional ambivalence, with participants reporting mixed emotions of sadness, compassion, admiration, fear, hate and disappointment. Students usually associated positive emotions of compassion and admiration with refugees and the difficulties they face, while negative emotions, like sadness and disappointment, are usually associated with their appraisal of the unsatisfactory social and political action taken towards solving these issues. The combination of positive emotions, like compassion and admiration, seems to be a significant precursor to empathy. In this case, such emotions appear to be the building blocks of a seemingly empathetic attitude regarding migrants and refugees. However, the introduction of a dilemma about this topic allowed us to probe deeper into the participants’ emotional and moral conflicts and to unveil some of the cognitive strategies used to overcome them.

Since democratic decision-making is itself a communal process, the use of moral dilemmas in schools can be seen as an effective pedagogical activity for critical citizenship education, as proposed decades ago by Blatt and Kohlberg (Citation1975). It allows the participants to be exposed to opposing arguments and emotions with which they can contrast their own personal moral standards, which can foster moral-cognitive conflict and CT. In this study, we used the tradition of moral dilemmas as a tool for addressing controversial political issues – “wicked problems” in contemporary EU policy – that were particularly engaging in emotional terms, generating strong emotional ambivalence. While the discussion of controversial issues is also a classical strategy in citizenship education (Hess, Citation2009; Veugelers, Citation2007), our study shows that the emotionality of the controversies, far from being something to be feared or avoided, is an advantage for the quality of the debate and for the promotion of students’ CT and democratic engagement. However, “within education, as in the wider culture, emotions are a site of social control” (Boler, Citation1999, p. xiv) and many teachers avoid discussing emotional topics for fear of losing control over class dynamics (Piedade et al., Citation2021). In this sense, embracing a “pedagogy of discomfort” (Boler, 1999; Zembylas & Boler, Citation2002) and “risk-taking” (Pinto & Portelli, Citation2009) still emerge as unmet factors that limit the adoption of a model of critical democratic education in the Portuguese upper secondary school system.

Indeed, our findings suggest that the teachers’ role is essential in this process, to confront and deal with the risks inherent to class discussion. The in-group unanimity in the participants’ responses to the dilemma indicates that some students may have adjusted their responses “to present themselves favorably” (Roma & Conway, Citation2018, p. 34) to their colleagues, which can be seen as a limitation both of our study and of the use of moral dilemmas in groups. Therefore, it is important that teachers assume a critical moderation (Shapira-Lishchinsky, Citation2011) that can help the participants to question how their own opinions are being influenced by the opinions of the majority and to realise that “respecting another view is very different from accepting any view whatsoever” (Pinto & Portelli, Citation2009, p. 303).

Another significant aspect had to do with the role of the socioeconomic context in the participants’ decision-making, with participants from lower socioeconomic backgrounds more inclined to empathise with economic reasons, while students in middle/high socioeconomic backgrounds tended to adopt a more legal and moral approach. The students in the first group who had displayed an empathetic connection with the refugees were more prone to experience strong emotional ambivalence when confronted with Antonio’s character, arguably because their own personal socioeconomic circumstances had also led them to empathise with Antoniós financial difficulties. The fact that students in the second group were less receptive to Antonio’s situation and were more focused on abstract moral and legal issues, seems to indicate that empathy through personal experience (Lim & DeSteno, Citation2016) collides with and can eventually overcome abstract empathy (Stueber, Citation2016). As such, these results also show that using moral dilemmas as a pedagogical tool to develop the participants’ CT skills and moral and political development should preferably include students from different social backgrounds. This can stimulate the students to reflect about how their own personal stories influence their decisions – and again, the role of teachers in stimulating these reflections is extremely important.

Naturally, given the limited sample of this study, these findings should be followed by research combining emotions and other political topics viewed as “wicked problems”. Nevertheless, there was a significant heterogeneity in the arguments used to reach a decision and the combined analysis of the GEW and moral dilemma indicates that stronger emotional engagement with a moral issue can lead to high levels of conflict in decision-making. In the case of this dilemma, deontological-humanitarian arguments were usually associated with positive emotions, such as compassion and admiration for the refugees, while utilitarian arguments appear to be linked to negative emotions, such as fear. This confirms that both perspectives include an affective dimension (Manfrinati et al., Citation2013), and that students who had reported positive emotions regarding the refugees in the GEW, but had, nonetheless, taken a utilitarian approach to the dilemma, may have used emotional suppression (Lee & Gino, Citation2015) of negative emotions. Conversely, emotional ambivalence seems to increase moral conflict. Given that students who were morally torn between deontological-humanitarian and utilitarian arguments seemed to be more willing to resort to specific cognitive skills, such as contrasting and analysing different opinions, in order to resolve their moral conflict, emotional ambivalence can have positive effects on CT. This is in line with previous research that has already indicated that moral conflict can have positive effects on cognitive development (Bucciarelli & Daniele, Citation2015) and, consequently, on the ability to deconstruct the basis of prejudicial attitudes (Dhont & Hodson, Citation2014).

In a nutshell, our study suggests that educating critical citizens may involve relatively uncomfortable moments of emotional, moral and cognitive conflict, in which contentious discussions about controversial sociopolitical topics may arise. However, it is precisely this conflict that can lead students to develop their (meta)cognitive CT skills and to find solid and reflected moral basis for their political opinions and engagement (Hedtke, Citation2016; Ribeiro et al., Citation2017). Additionally, participating in these activities in school can train students to manage sociopolitical conflict agonistically (Mouffe, Citation2014), which will be crucial for the democratic negotiation of their social needs, moral standards and political opinions within their communities.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For more information about the original version of the GEW, see https://www.unige.ch/cisa/gew/.

References

- Abrami, P., Bernard, R., Borokhovski, E., Waddington, D., Wade, C. A., & Persson, T. (2015). Strategies for teaching students to think critically: A meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research, 85(2), 275–314. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314551063

- Alexander, J., & Sandhal, I. (2016). The Danish way of parenting: What the happiest people in the world know about raising confident, capable kids. Penguin Random House LLC.

- Bakker, B., Shumacher, G., & Rooduijn, M. (2020). Hot politics? Affective responses to political rhetoric. American Political Science Review, 115(1), 150–164. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055420000519

- Bartels, R., Onstenk, J., & Veugelers, W. (2016). Philosophy for democracy. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 46(5), 681–700. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2015.1041367

- Beane, J. (1990). Affect in the curriculum: Toward democracy, dignity, and diversity. Teachers College Press.

- Bennett, L., & Pidcock, L. (2014). Critical thinking and safe spaces – materials and methods for challenging prejudice. Race Equality Teaching, 32(2), 46–50. https://doi.org/10.18546/RET.32.2.09. https://access.portico.org/stable?au=phx2c2c2f38

- Blatt, M., & Kohlberg, L. (1975). The effects of classroom moral discussion upon children’s level of moral judgment. Journal of Moral Education, 4(2), 129–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305724750040207

- Boler, M. (1999). Feeling power: Emotions and education. Routledge.

- Brader, T., & Marcus, G. (2013). Emotion and political psychology. In L. Huddy, D. Sears, & J. Levy (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political psychology (pp. 165–204). Oxford University Press.

- Bucciarelli, M., & Daniele, M. (2015). Reasoning in moral conflicts. Thinking & Reasoning, 21(3), 265–294. https://doi.org/10.1080/13546783.2014.970230

- Christensen, J., & Gomila, A. (2012). Moral dilemmas in cognitive neuroscience of moral decision-making: A principled review. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 36(4), 1249–1264. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.008

- Cohen, J. (2005). The vulcanization of the human brain: A neural perspective on interactions between cognition and emotion. Journal of Economic Perspectives, 19(4), 3–24. https://doi.org/10.1257/089533005775196750

- Council of Europe. (2016). Competences for democratic culture: Living together as equals in culturally diverse democratic societies. Council of Europe Publishing.

- Damásio, A. (2003). Ao encontro de Espinosa: As emoções sociais e a neurologia do sentir [Looking for Spinoza: Joy, sorrow, and the feeling brain] (ed. Port.). Publicações Europa-América.

- De Groot, I. (2017). Mock elections in civic education: A space for critical democratic citizenship development. Journal of Social Science Education, 16(3), 84–96. https://doi.org/10.2390/jsse-v16-i3-1584

- DeJaeghere, J. (2009). Critical citizenship education for multicultural societies. Interamerican Journal of Education for Democracy, 2(2), 223–236.

- Dhont, K., & Hodson, G. (2014). Does lower cognitive ability predict greater prejudice? Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23(6), 454–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963721414549750

- Ennis, R. (1996). Critical thinking dispositions: Their nature and assessability. Informal Logic, 18(2–3), 165–182. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v18i2.2378

- Facione, P. (1990). Critical thinking: A statement of expert consensus for purposes of educational assessment and instruction. Research findings and recommendations. American Philosophical Association.

- Gawronski, B., & Beer, J. (2017). What makes moral dilemma judgments “utilitarian” or “deontological”? Social Neuroscience, 12(6), 626–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470919.2016.1248787

- Greene, J. (2009). Dual-process morality and the personal/impersonal distinction: A reply to McGuire, Langdon, Coltheart, and Mackenzie. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45(3), 581–584. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2009.01.003

- Greene, J., Morelli, S., Lowenberg, K., Nystrom, L., & Cohen, J. (2008). Cognitive load selectively interferes with utilitarian moral judgment. Cognition, 107(3), 1144–1154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2007.11.004

- Gronostay, D. (2016). Argument, counterargument, and integration? Patterns of argument reappraisal in controversial classroom discussions. Journal of Social Science Education, 15(2), 42–56. https://doi.org/10.4119/UNIBI/jsse-v15-i2-1482

- Healey, R. (2012). The power of debate: Reflections on the potential of debates for engaging students in critical thinking about controversial geographical topics. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 36(2), 239–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.619522

- Hedtke, R. (2016). Education for participation: Subject didactics as an agent of politics? Educação, Sociedade & Culturas, 48, 7–30. https://doi.org/10.34626/esc.vi48.173

- Hess, D. (2009). Controversy in the classroom: The democratic power of discussion. Routledge.

- Hoffman, M. (2000). Empathy and moral development: Implications for caring and justice. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511805851

- Holma, K. (2015). The critical spirit: Emotional and moral dimensions of critical thinking. Studier I Pædagogisk Filosofi, 4, 17–28. https://doi.org/10.7146/spf.v4i1.18280

- Huebner, B., Dwyer, S., & Hauser, M. (2009). The role of emotion in moral psychology. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(1), 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2008.09.006

- Irvin, R., & Stansbury, J. (2004). Citizen participation in decision making: Is it worth the effort? Public Administration Review, 64(1), 55–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6210.2004.00346.x

- Jennings, L., Parra-Medina, D., Hilfinger-Messias, D., & McLoughlin, K. (2006). Toward a critical social theory of youth empowerment. Journal of Community Practice, 14(1–2), 31–55. https://doi.org/10.1300/J125v14n01_03

- Kohlberg, L. (1975). The cognitive-developmental approach to moral education. The Phi Delta Kappan, 56(10), 670–677. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20298084

- Kuhn, D. (1999). A developmental model of critical thinking. Educational Researcher, 28(2), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X028002016

- Lee, J., & Gino, F. (2015). Poker-faced morality: Concealing emotions leads to utilitarian decision making. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 126, 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2014.10.006

- Lerner, J., Li, Y., Valdesolo, P., & Kassam, K. (2015). Emotion and decision-making. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 799–823. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010213-115043

- Lietz, C., & Zayas, L. (2010). Evaluating qualitative research for social work practitioners. Advances in Social Work, 11(2), 188–202. https://doi.org/10.18060/589

- Lim, D., & DeSteno, D. (2016). Suffering and compassion: The links among adverse life experiences, empathy, compassion, and prosocial behavior. Emotion, 16(2), 175–182. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0000144

- Ludwig, D. (2001). The era of management is over. Ecosystems, 4(8), 758–764. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10021-001-0044-x

- Luo, J., & Yu, R. (2015). Follow the heart or the head? The interactive influence model of emotion and cognition. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 1–14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00573

- Manfrinati, A., Lotto, L., Sarlo, M., Palomba, D., & Rumiati, R. (2013). Moral dilemmas and moral principles: When emotion and cognition unite. Cognition and Emotion, 27(7), 1276–1291. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699931.2013.785388

- Mathé, N. (2016). Students’ understanding of the concept of democracy and implications for teacher education in social studies. Acta Didactica Norge, 10(2), 271–289. https://doi.org/10.5617/adno.2437

- Mead, J., & Scharmann, L. (1994). Enhancing critical thinking through structured academic controversy. The American Biology Teacher, 56(7), 416–419. https://doi.org/10.2307/4449872. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4449872

- Mesquita, B., & Boiger, M. (2014). Emotions in context: A sociodynamic model of emotions. Emotion Review, 6(4), 298–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914534480

- Moon, J. (2008). Critical thinking: An exploration of theory and practice. Routledge.

- Morse, J., Barrett, M., Mayan, M., Olson, K., & Spiers, J. (2002). Verification strategies for establishing reliability and validity in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 1(2), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690200100202

- Mouffe, C. (2014). Democratic politics and conflict: An agonistic approach. In M. Lakitsch (Ed.), Political power reconsidered: State power and civic activism between legitimacy and violence. Peace report 2013 (pp. 17–29). Lit Verlag.

- Myyry, L., & Helkama, K. (2007). Socio-cognitive conflict, emotions and complexity of thought in real-life morality. Scandinavian Journal of Psychology, 48(3), 247–259. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9450.2007.00579.x

- Norris, J., Squires, N., Taber, C., & Lodge, M. (2003). Activation of political attitudes: A psychophysiological examination of the hot cognition hypothesis. Political Psychology, 24(4), 727–745. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1467-9221.2003.00349.x

- Paul, R. (2000). Critical thinking, moral integrity and citizenship: Teaching for the intellectual virtues. In G. Axtell (Ed.), Knowledge, belief, and character: Readings in virtue epistemology (pp. 163–175). Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Paul, R., & Elder, L. (2005). Critical thinking competency standards: Standards, principles, performance indicators, and outcomes with a critical thinking master rubric. Foundation for Critical Thinking.

- Pekrun, R. (2016). Using self-report to assess emotions in education. In M. Zembylas & P. Schutz (Eds.), Methodological advances in research on emotion and education (pp. 43–54). Springer International Publishing.

- Piedade, F., Malafaia, C., Neves, T., Loff, M., & Menezes, I. (2020). Educating critical citizens? Portuguese teachers and students’ visions of critical thinking at school. Thinking Skills and Creativity, 37, Article 100690. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2020.100690

- Piedade, F., Malafaia, C., Neves, T., Loff, M., & Menezes, I. (2021). The role of emotions in critical thinking about European politics – confronting anti-immigration rhetoric in the classroom. (Paper submitted).

- Pinto, L., & Portelli, J. (2009). The role and impact of critical thinking in democratic education: Challenges and possibilities. In J. Sobocan, L. Groarke, R. Johnson, & F. Ellett (Eds.), Critical thinking education and assessment: Can higher order thinking be tested? (pp. 299–320). Althouse Press.

- Quantz, R. (2015). Sociocultural studies in education: Critical thinking for democracy. Routledge.

- Ratner, C. (2007). A macro cultural-psychological theory of emotions. In P. Shultz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 89–104). Elsevier.

- Redlawsk, D. (2002). Hot cognition or cool consideration? Testing the effects of motivated reasoning on political decision making. The Journal of Politics, 64(4), 1021–1044. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.00161

- Rest, J., Cooper, D., Coder, R., Masanz, J., & Anderson, D. (1974). Judging the important issues in moral dilemmas: An objective measure of development. Developmental Psychology, 10(4), 491–501. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0036598

- Ribeiro, N., Neves, T., & Menezes, I. (2017). An organization of the theoretical perspectives in the field of civic and political participation: Contributions to citizenship education. Journal of Political Science Education, 13(4), 426–446. https://doi.org/10.1080/15512169.2017.1354765

- Rittel, H., & Webber, M. (1973). Dilemmas in a general theory of planning. Policy Sciences, 4(2), 155–169. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01405730

- Roma, S., & Conway, P. (2018). The strategic moral self: Self-presentation shapes moral dilemma judgments. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 74, 24–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2017.08.003

- Rutland, A., Killen, M., & Abrams, D. (2010). A new social-cognitive developmental perspective on prejudice: The interplay between morality and group identity. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 5(3), 279–291. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691610369468

- Scherer, K. (2005). What are emotions? And how can they be measured? Social Science Information, 44(4), 695–729. https://doi.org/10.1177/0539018405058216

- Shapira-Lishchinsky, O. (2011). Teachers’ critical incidents: Ethical dilemmas in teaching practice. Teaching and Teacher Education, 27(3), 648–656. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2010.11.003

- Shepherd, L., Fasoli, F., Pereira, A., & Branscombe, N. (2017). The role of threat, emotions, and prejudice in promoting collective action against immigrant groups. European Journal of Social Psychology, 48(4), 447–459. https://doi.org/10.1002/ejsp.2346

- Shultz, P., & Pekrun, R. (2007). Introduction to emotion in education. In P. Shultz & R. Pekrun (Eds.), Emotion in education (pp. 3–10). Elsevier.

- Stueber, K. (2016). Empathy and the imagination. In A. Kind (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of philosophy of imagination (pp. 388–399). Routledge.

- Termeer, C., Dewulf, A., & Biesbroek, R. (2019). A critical assessment of the wicked problem concept: Relevance and usefulness for policy science and practice. Policy and Society, 38(2), 167–179. https://doi.org/10.1080/14494035.2019.1617971

- Tsui, L. (2002). Fostering critical thinking through effective pedagogy: Evidence from four institutional case studies. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(6), 740–763. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1558404?origin=JSTOR-pdf.

- Van Den Bos, K. (2007). Hot cognition and social justice judgements: The combined influence of cognitive and affective factors on the justice judgement process. In D. De Cremer (Ed.), Advances in the psychology of justice and affect (pp. 59–82). Information Age Publishing.

- Van der Does, R., Kantorowicz, J., Kuipers, S., & Liem, M. (2021). Does terrorism dominate citizens’ hearts or minds? The relationship between fear of terrorism and trust in government. Terrorism and Political Violence, 33(6), 1276–1294. https://doi.org/10.1080/09546553.2019.1608951

- Veugelers, W. (2007). Creating critical-democratic citizenship education: Empowering humanity and democracy in Dutch education. Compare. A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 37(1), 105–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057920601061893

- Veugelers, W. (2011). Introduction: Linking autonomy and humanity. In W. Veugelers (Ed.), Education and humanism: Linking autonomy and humanity (pp. 1–8). Sense Publishers.

- Westheimer, J., & Kahne, J. (2004). What kind of citizen? The politics of educating for democracy. American Educational Research Journal, 41(2), 237–269. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312041002237

- Whyte, K., & Thompson, P. (2012). Ideas for how to take wicked problems seriously. Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics, 25(4), 441–445. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10806-011-9348-9

- Zembylas, M. (2012). The politics of fear and empathy: Emotional ambivalence in “host” children and youth discourses about migrants in Cyprus. Intercultural Education, 23(3), 195–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14675986.2012.701426

- Zembylas, M., & Boler, M. (2002). On the spirit of patriotism: Challenges of a “pedagogy of discomfort.” Special issue on education and September 11. Teachers College Record On-Line. http://tcrecord.org