ABSTRACT

Chile’s Inclusion Law, passed in 2015, significantly increased government regulation of one of the most privatised education systems in the world and provided major redistributive benefits. How did Chile’s government succeed in passing and implementing this legislation in the face of a powerful and cohesive opposition? Our study finds that student protesters served as the initial impetus, shaping the education debate and increasing the political salience and urgency of education reform. In line with power resource theory, other left movement organisations and voters used their power to support redistributive education reform, and Bachelet’s centre-left coalition followed through on its mandate by proposing the Inclusion Law. Also, a well-connected policy network helped articulate problems with the status quo and shaped the specifics of the education bill. To develop this argument, the paper draws on historical information on the student movement in Chile, quantitative data on education stakeholder appearances in the press, public opinion surveys, and detailed analysis of the 13-month legislative proceedings – to explain the law’s passage in congress. To underscore the significance of the Inclusion Law and to contextualise the Chilean case, the paper also compares Chile to other countries with nation-wide school choice systems.

1. Introduction

Education in Chile is highly politicised. Since the mid-2000s, education has been at the centre of street demonstrations, school occupations, electoral politics, public opinion, pundit debate, ferment in civil society, and congressional activism. The highly contentious 2015 Inclusion Law mobilised all these actors and venues. The pre-2015 voucher system – with copayments, student selection by schools, and for-profit schools – was very effective in sorting students by social class. In Friedman’s (Citation1962) original voucher model – that directly inspired the founders of Chile’s pre-2015 voucher system – families were supposed to drive quality improvements by selecting better schools for their children. But, inverting Friedman’s formulation, in Chile’s model, schools improved performance by selecting “better”, richer students.

That is, as a mounting volume of research confirmed, the pre-2015 system provided incentives for private-voucher schools to select socioeconomically advantaged students and exclude others through various mechanisms (Zancajo, Citation2019b), rather than to increase their value-added in terms of educational achievement. In fact, Lara, Mizala, & Repetto (Citation2011) examined test score gains in private-voucher schools compared to public municipal schools and found positive but very small or insignificant effects. Also, Hofflinger and von Hippel (Citation2020) found that competition among schools did not raise children’s achievement. At the same time, the school choice policies were associated with substantial socioeconomic inequalities in educational achievement and socioeconomic segregation (Mizala & Torche Citation2012; Valenzuela et al., Citation2013).Footnote1

The aim of the 2015 Inclusion Law was to increase regulation of private educational provision, eliminate profits in government-subsidised schools, and remove market-based incentives for restricting educational opportunities through student selection and tuition fees. The Inclusion Law was part of a package of education reforms favouring poorer students that were all financed by a major tax increase to raise 3 percent of GDP, especially from the rich. Other redistributive features built into the Inclusion Law included: opening up more school choices for poorer students by prohibiting selection and co-payments, increasing the voucher funding that followed poorer students (the preferential voucher)Footnote2 and extending the preferential voucher to middle-class students, and outlawing profits for owners of private-voucher schools.

The sums involved were big. The Inclusion Law forbade for-profit schools, which constituted two thirds of private-voucher schools (Elacqua, Citation2012) and that had reaped, according to government estimates, US$400 million (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 235). Replacing the copaymentsFootnote3 charged by private-voucher schools was estimated to cost the government $1.2 billion or .4 percent of GDP per year over the long run (DIPRES, Citation2014). The new Inclusion Law was an educational reform (which increased regulation) with a significant redistributive impact.

How did the government in 2015 manage to pass this costly and divisive law, especially considering that Bachelet was unable in her first term to get a law through congress prohibiting profits and student selection? Our short answers are: 1) student protesters provided the initial impetus for the reform, 2) left movement organisations, voters, and a left party coalition used their power to push for a reform, and, 3) a well-articulated policy network influenced the specifics of reform design. As a result, Bachelet’s second government overcame strident opposition from the right-wing political coalition (Chile Vamos), well-established interest groups representing private-voucher schools, and civil society organisations that included parent groups and the Catholic Church.

Besides the theoretical contributions of our argument, why else might an education reform in a small country be of wider interest? Two features are key. First, many governments around the world have been moving to greater reliance on private providers of public services, from day care to elder care to prisons. Chilean education provides a revealing window into the sorts of post-privatisation politics – with a highly mobilised private sector – that other countries face or will face. Second, this policy change in Chile brought distributional politics into high relief. While education scholars may agree that education policy is distributive (Ansell, Citation2010) and sometimes redistributive, politics surrounding policy change in education rarely revolve so clearly around redistribution as they did with the Inclusion Law.

2. Arguments and evidence

Our argument highlights four key variables in the reform process. The first is not a step in the reform’s passage, but rather a factor that made the Inclusion Law challenging to pass. That is, the privatisation of education, resulting from the voucher system, spawned new and powerful interest groups of owners of private-voucher schools with keen interests in limiting government regulations in education like the Inclusion Law. Second, the student movement shaped education debate, influenced the second Bachelet government’s agenda, and increased the political salience of education policy. Third, as in power resource theory (PRT), socio-economically disadvantaged voters, other civil society and labour organisations, and a centre-left-party coalition (including from the Christian Democratic Party to the Communist Party) complemented the students in using their power to support redistributive education policy. And, fourth, Chile’s well-developed policy network provided empirical documentation of problems in the voucher model, and technical specifics for the Inclusion Law. This section covers each of these four groups in turn.

New interest groups. The privatisation of education in 1981 shifted education politics in Chile by creating what became a powerful lobby for private-voucher schools, putting “the state in a situation of relative impotence in the face of the power of owners of private schools (including the Catholic Church); one of the most influential interest groups in education in Chile” (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 242, our translation). Owners of private schools were well-connected not only with right-wing opposition parties, but also with prominent members of the centrist Christian Democratic Party that belonged to Bachelet’s Nueva Mayoría (New Majority) coalition. Furthermore, when services depend on voluntary investment by private firms – the necessary result of privatisation – then firms can threaten to defect (investment strike) to pressure policy makers to their preferred position, in an exercise of structural power (Fairfield, Citation2015). During congressional deliberations on the bill, private-voucher schools did just that to threaten the government by claiming that the reform would force schools to close or go fully private (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 238).Footnote4

Student protests. The perceived faults and inequities of the voucher system, and the specific remedies in the Inclusion Law would not have been so clearly and centrally placed on the electoral agenda were it not for the previous years of student demonstrations (Inzunza et al., Citation2019). The student protests shaped the education debate in Chile, influenced the second Bachelet government’s agenda, and increased the public salience of education reform.Footnote5 Student protests raised public awareness and concern about education reform ahead of Bachelet’s campaign and election. In this way, the Chilean case aligns with existing arguments that social movements can play a crucial role in increasing the political salience of particular issues and thus set the agenda for legislative politics (Burstein, Citation1998; Walgrave & Vliegenthart, Citation2012). As Culpepper (Citation2011) argues, salience is a critical variable in democratic politics: on issues of low salience, the “quiet politics” of business and interest groups have greater influence; on issues of high salience, the median voter wins out more often.

Power resource theory. Student protesters (along with policy networks discussed below) began the pressure for redistributive education reform in preceding years. However, the political trajectory of the Inclusion Law provides support for power resource theory (PRT) because actors on the left – social movement organisations, socioeconomically disadvantaged voters, and left parties – exercised their power to support redistributive education policy (Huber & Stephens, Citation2010; Korpi, Citation1989). Original formulations of PRT focused specifically on how workers used their labour market position and union organisation to push for expansion of social policies (Korpi, Citation1978). This bottom-up PRT model does not fare well in Latin America generally nor in overall distributive politics in Chile (which in income remains one of the most unequal countries in the region and in the OECD) due to the small relative size of the industrial working class and the related weakness of organised labour and labour-based parties (Huber & Stephens, Citation2012).

However, the general analytical contribution of PRT is to “assess changes in the distribution and configuration of power resources for a given society (or sector or workplace) at a given point in history and use such changes to explain specific societal changes (such as levels of inequality, institutional reforms and labour conflicts)” (Refslund & Arnholtz, Citation2021, p. 4). The students initiated a change in power resources in the education sector through their associational power, socioeconomically-disadvantaged voters turned out to support the candidate committed to redistribution in education, and Bachelet’s centre-left coalition used its electoral mandate and majority to seek redistributive education reform through the Inclusion Law.Footnote6 Furthermore, some organised groups in civil society, like the teachers’ union, continued to pressure for the Inclusion Law once the bill entered the legislative process (see Section VI).

Policy networks. Policy networks are a general term for a cluster of concepts focusing on “sets of formal institutional and informal linkages between governmental and other actors structured around shared if endlessly negotiated beliefs and interests in public policy making and implementation” (Rhodes, Citation2006, pp. 1–2). Miller and Demir (Citation2007) add that the concept directs attention away from formal government structures and toward other meaningful interactions that influence policy activity. In Chile, the key policy network in education includes academics and researchers in universities, think tanks, and NGOs (covered in Section V) (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 237). This networks formed among elites and excluded social movements and unions.

Complementing student pressure, a growing accumulation of research – and the policy network associated with it – diagnosed problems with the voucher model and provided a compelling empirical rationale for reform that shaped many of the specific reform designs (Muñoz & Weinstein, Citation2020; Zancajo, Citation2019a). In the first annual presidential address during her second administration, on May 21, 2014, Bachelet mentions that “all of the international evidence shows that the best promoter of quality education is not the profit incentive, but the educational projects and the vocation to teach” (Bachelet, Citation2014a). Bachelet’s introduction to the Inclusion Law bill itself, which entered Congress in May 2014, cites various policy studies, organised around the three main tenets of the bill: no copayments (7 studies), no selection (10 studies), and no profits (11 studies) (Bachelet, Citation2014b). Section VI discusses the details of the evidence-based arguments for the reform that are developed in these studies and drawn from actors in the Chilean education policy network.

While drawing on existing theories in the literature on each of the four main factors, the key contribution of this paper is to develop a cohesive argument of how these factors related to each other and came together to cause the unlikely passage of a major education reform in Chile. In sum, we emphasise the importance of student movements especially in raising the salience of education inequality. This salience then fed into a bottom-up, PRT electoral campaign and mandate for Bachelet’s second government. Chile’s well-developed policy network provided both a diagnosis of problems in the voucher system as well as some prescriptions on how best to address those problems.

The comparative cases in Section III suggest that these factors may also be important in understanding educational reform in other contexts. For example, existing research suggests that policy networks were important in driving education reform in New Zealand. In line with PRT, it was the Left Party in Sweden that campaigned against profits in education and sought to build coalitions for education reform in recent years. On the other hand, some of the failures of the leftist party coalition in Sweden in passing reform suggest that other variables – like social movement pressure and favourable policy networks prominent in Chile – may also be important complementary factors to successfully passing regulatory education reform in other voucher-system contexts.

2.1. Empirical evidence

Section III uses secondary source material on Sweden, New Zealand, Denmark, and the Netherlands to compare Chile to other national school-choice systems. Section IV draws on both existing academic research on student protests in Chile and survey material from Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP), a Santiago-based think tank.Footnote7 Section V measures the engagement of educational stakeholders through quantitative analysis of daily press briefings prepared for the Ministry of Education (Mineduc) between 2014 and 2015 (a total of 1,153 press briefings). The authors used Nvivo software to calculate stakeholder appearances in the press reports related to the Inclusion Law (Mizala & Schneider, Citation2019). Section VI draws on reports of the legislative debates of the Inclusion Law directly from the Chilean Ministry of Education and on other academic sources. Lastly, one of the authors was a core member of the policy network with prior participation in government councils on education and advising in Mineduc, and thus brings an insider’s view to much of the policy process.Footnote8

3. The Inclusion Law in comparative perspective: from least to most regulated

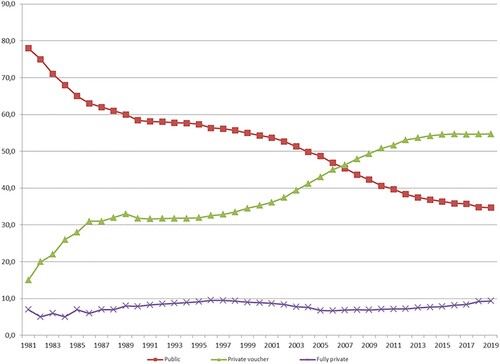

Before detailing how Chile passed this significant education reform in Sections IV-VI, this section discusses how Chile arrived at such a privatised system and contextualises the Chilean case by comparing Chile, pre- and post-2015 reform, to other democracies with nation-wide school-choice systems. In 1981, the military government radically transformed education by instituting a voucher system and transferring public schools to municipal governments. The new system had three types of schools: fully private schools with no state support, private-voucher schools with state funding, and municipal schools with state funding. After 1981, enrolments migrated steadily from municipal to private-voucher schools (). By 2014, on the eve of reform, the distribution of enrolment was 56 percent in private-voucher schools, 37 percent in municipal schools, and 8 percent in private-tuition schools.

Figure 1. Enrolment in public (municipal), private-voucher, and private schools, 1981-2019. Source: Unidad de Estadísticas, Ministerio de Educación.

The Chilean school system has been, by design, one the most market-based in the world. Private-voucher and municipal schools were funded on an equal per-student formula, but private-voucher schools could select their students and be explicitly for profit. Two thirds of private-voucher schools were for profit (Elacqua, Citation2012, p. 448). The capacity to select students and charge copayments on top of the voucher provided incentives for private-voucher schools to select richer students. Student selection based on family characteristics and academic performance was widespread (Grau, Hojman & Mizala Citation2018). In 2006, the share of vulnerable (poor) students was 40 percent in municipal schools and 37 percent in private-voucher schools without any copay, compared with only 14 percent in private-voucher schools with copayments, the vast majority of schools (Elacqua, Citation2012, p. 450).

Copayment has a revealing political history. In 1988, the military dictatorship rescinded the right of private-voucher schools to levy copayments. When they took over in 1990, the new, centre-left Concertación government wanted to increase taxes to finance new social welfare programmes, but they lacked a majority in congress. In negotiations, the right-wing party, Renovación Nacional (RN), made its support for the tax increase conditional on resurrecting copayments which became legal again in 1993 (Donoso, Citation2013; Burton Citation2012). Copayments expanded rapidly from covering 16 percent of private-voucher enrolments in 1993 to about 80 percent in 1998, stabilising thereafter (Mizala & Torche Citation2017). By 2015, copayments made up 16% of total spending in private-voucher schools (Bertoni et al., Citation2018, p. 5). This episode shows how valuable copayment was to the right-wing opposition and their supporters in private education and foreshadows the difficulty centre-left governments would have to restrict copayments until they gained solid majorities in congress in 2015.

How does Chile’s voucher system compare with the few other countries – Sweden, New Zealand, Denmark, and the Netherlands – that have nation-wide systems of school choice?Footnote9 In essence, the Inclusion Law moved Chile from the least regulated system (New Zealand) to the most regulated (like the Netherlands) (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 244). Although not as intense as in Chile, political contention continues in the most recently created systems for school choice in Sweden and New Zealand.

Along the main dimensions of the Inclusion Law, the other four systems vary (). Denmark and New Zealand allow non-public schools to charge fees. The Danish government subsidises approximately 80 percent of the average cost of independent (non-public) schools; these schools can either charge tuition or obtain external grants to cover the rest of their costs. New Zealand’s voucher varies in value across types of private schools as does their license to charge fees. In contrast, the Netherlands and Sweden (and Chile after the Inclusion Law) fully fund their private-school alternatives and prohibit extra fees.Footnote10

Table 1. Degrees of Regulation: Profits, Selection, and Fees in National School Choice Systems.

Sweden and the Netherlands also prohibit student selection in all schools, though schools in the Netherlands, as in Chile after 2015, can require that parents subscribe to the value system or religion of the school. Private schools in Denmark and non-public schools in New Zealand can select students. Sweden and New Zealand are comparable to Chile before the Inclusion Law in that they allow for-profit schools. Sweden even has several big companies that own large chains of schools. These countries also vary in policies on preferential vouchers, or providing additional funding for poor students. Chile, the Netherlands, and New Zealand have national policies to pay higher amounts for students from poorer backgrounds.Footnote11

Overall, New Zealand and Chile (pre 2015) were the most deregulated systems of school choice. Like Chile, New Zealand allowed schools to charge extra fees, select students, and make profits, though New Zealand had only a fifth of Chile’s enrolments in private-voucher schools. The approval of the Inclusion Law brought Chile closer to the most regulated system in the Netherlands.

Political contention over school choice can be also, as in Chile, intense. Contemporary politics depends a lot on why and when governments created school-choice systems. Denmark (1855) and the Netherlands (1917) have the oldest systems, and both are settled and consolidated. In contrast, systems in New Zealand, Sweden, and Chile emerged much later in the late twentieth century. These were post-Friedman systems enacted by self-styled neoliberal governments and were thus less consensual and faced occasionally intense opposition from leftist movements and parties that have yet to accept neoliberalism as settled and consolidated.

The Dutch and Danish systems date back more than a century and resulted from struggles over central government control of education. In Denmark, since the Free School Act of 1855, parents and non-profit organisations have been entitled to set up their own schools. This Act grew out of opposition to excessive centralised control of the education system. The independent school sector is not as large as in the Netherlands, but the market share of independent schools in Denmark has been growing. The school-choice system in Denmark is not controversial (Justesen, Citation2002). The Dutch system came out of a historic political compromise that gave private denominational education funding equal to public schools (in exchange for Social Democrats’ demand for universal suffrage (Karsten, Citation1999)). The deep historical roots and the institutional protections of school autonomy, explicitly protected in the 1917 Constitution, have helped consolidate the school choice system (Ladd et al., Citation2010). However, increasing segregation in Dutch schools is generating more controversy.

In Sweden (core case of many original PRT theories) in the midst of debates on the crisis in education in the early 1990s, the right-wing government enacted the school-choice system (Bunar, Citation2010). By the 2010s profits in schools (and other welfare services) became a fulcrum of left-right electoral competition, and in surveys clear majorities opposed profits in education. The Left Party consistently campaigned against profits and in 2014 made joining a coalition government with the Greens and Social Democrats contingent on trying to limit profits. However, the coalition lacked the votes to pass the legislation. In comparison to Chile, Sweden lacks sustained student protests against profits. Unlike Sweden, Chile lacks big business (for example, the Wallenberg family) that invest in education and is active in politics. Nonetheless, the issue of profits in Sweden does not seem likely to fade away soon.

In New Zealand, a neoliberal government deregulated schools (known as Tomorrow’s Schools) in the early 1990s. Later in the 1990s, similarly to the elite side of the Chilean reform story, a policy network of stakeholders, independent researchers, and analysts within the Ministry of Education underscored the Tomorrow’s Schools problems related to equity, efficiency, and accountability. This analysis fed into a number of modifications that increased the role of government and created a more regulated accountability system (Maani, Citation2017). In recent years, New Zealand’s policy network has continued to drive reforms. The Tomorrow’s Schools Taskforce, appointed by the Minister of Education in 2018, held over 100 public and targeted meetings with stakeholders and submitted a final report of recommended reforms to the government in July 2019 (“Tomorrow’s Schools Review”, Citation2019). Based on the recommendations, in November 2019, the government announced the most significant reforms to date in re-regulating the system of school choice. Further education reforms continued to be debated in the 2020 elections (Cooke et al., Citation2020).

In sum, Chile is not the only place with intense education politics. Late twentieth century systems of school choice in Sweden, Chile, and New Zealand were closely associated with the neoliberal governments that enacted them. Left parties doing battle with neoliberalism were likely to attempt to regulate voucher systems when they had the votes in Congress. Furthermore, as noted in the previous section, some of the same factors highlighted as critical to reform in the Chilean case – such as PRT and policy networks – also seem relevant in other contexts.

The next section of this paper seeks to explain the factors that contributed to a left government in Chile succeeding in regulating the country’s voucher system. Whether the Inclusion Law and other reforms in Chile will lead ultimately to consolidation as in Denmark and the Netherlands remains to be seen, but for now the continued contentiousness of education politics in Chile signal that the system is not yet settled.

4. From student activism to presidential campaign, 2006–13

From 2006 through the estallido social (social irruption) of 2019, students – both secondary and university – have led hundreds of highly disruptive and visible protests: street demonstrations, school occupations, and university shutdowns. Both directly through their demands and indirectly through their support in broader public opinion (Inzunza et al., Citation2019, p. 495; Kubal & Fisher, Citation2016), the student protesters influenced the Inclusion Law proposal of the second Bachelet administration. These sustained protests are a revealing case of a social movement framing debate on education and ratcheting up its salience in politics.Footnote12 This bottom-up movement was the first step in our PRT argument.

In 2006, high school students, referred to as “Pingüinos” (because of their school uniforms), led the largest wave of protests in Chile since the country’s return to democracy in 1990. As expected in PRT, the central leaders of the movement were enrolled in municipal schools (Donoso, Citation2013) and “a great percentage of [participating students] were part of the lower and middle class” (Inzunza et al., Citation2019, p. 496). But a key characteristic of the 2006 protests was broad-based participation, and students from private-voucher and even some private schools joined in the protests (Gajardo, Citation2011; Silva, Citation2007). After two months, 80 percent of high schools were mobilised (Inzunza et al., Citation2019, p. 495).

Student demands focused initially on particular issues like school infrastructure and transportation subsidies but over time expanded to include more fundamental changes to the education system. Along with replacing the dictatorship’s education law, student demands touched on core tenets of the subsequent 2015 Inclusion Law, calling for the end of government subsidies to for-profit schools, a centralised state-funded system that prioritised public institutions, and measures to reform the discriminatory, socially-segregated education system (Donoso, Citation2013; Kubal & Fisher, Citation2016). By the end of May 2006, over 950 high schools were participating in protest demonstrations around these issues and nearly one million students and sympathisers turned out for nation-wide protests on May 30 (Ruíz, Citation2007).

Two days later, Bachelet – in her first government (2006-10) – created the Presidential Advisory Council for Quality Education. The eighty-member body incorporated all the principal actors in the education system, including student leaders, parents, school administrators, teacher union representatives, church representatives, education experts, and more (Kubal & Fisher, Citation2016). The council met for six months and published a report with recommendations for education reform. However, and significantly for later protests, students, parents, and representatives of teachers on the council – the so-called Social Bloc – did not endorse the final report (Mizala & Schneider Citation2014).

Undeterred by this lack of consensus, the first Bachelet government pushed ahead. The first reform bill in 2008 incorporated core Pingüino demands, including eliminating profits and student selection. However, in negotiations with the right-wing opposition, the government ceded ground and agreed to pass a watered-down General Law of Education (LGE) in 2009 that lacked provisions to end profits and student selection in secondary schools (Kubal & Fisher, Citation2016, p. 228). The ability of parties in Congress to block these core reforms demonstrated the power of opponents. Students saw the LGE as the illegitimate outcome of closed-door connivance and business as usual among political elites (Donoso, Citation2013).

In 2011, student protests erupted with even more force than in 2006, led this time by university students (including former Pingüinos who were now in university). The protests went on for seven months and included student occupations of 17 universities and 600 high schools (Inzunza et al., Citation2019, pp. 497–8). Many demands focused on higher education, but also reprised strengthening public education and outlawing profits (Bellei et al., Citation2014, pp. 432–433; Guzman-Concha Citation2012 as cited in Kubal & Fisher, Citation2016).

Students demonstrated their power through the magnitude and duration of protests for education reform. In 2011, higher education students more than tripled their previous annual peak in protest events since 2000 (Disi, Citation2018). The university students succeeded in drawing in diverse social actors with ties to education (Donoso, Citation2020) and in gaining support and coordinating collective actions with the National Union of Workers (Central Unitaria de Trabajadores), the teacher union Colegio de Profesores, parent groups, and other organisations (Silva, Citation2017, p. 265).

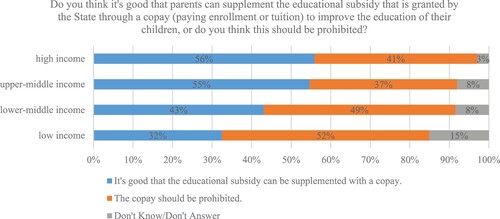

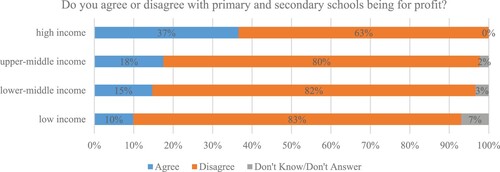

The demands of the students increased the salience of concerns about education among the wider population. Surveyed in September 2011, two thirds of respondents agreed with student demands and three quarters disapproved of the government’s handling of the protests (Tome, Citation2015, p. 194). By the end of 2011, a greater percentage of Chileans (53 percent) prioritised education as a major policy problem than ever before in surveys since 1990 and only slightly less than the top issue of crime (55 percent) (CEP, Citation2011b). Fully 80 percent of respondents opposed profits in education (CEP, Citation2011a); even 63 percent of high-income respondents rejected for-profit schools (see ) (Kubal & Fisher, Citation2016, p. 232). Ending copayments was less broadly supported, as 42 percent of Chileans thought it was good that parents could complement educational subsidies (CEP, Citation2011b); copayments approval ranged from 56 percent of high-income respondents to 32 percent of low-income respondents (). Both the increased prioritisation of education as an issue among Chileans and the overwhelming support for some of the students’ key demands demonstrates how the protests contributed to generating electoral issues for Bachelet’s campaign in 2013.

Figure 2. Views on Profits in Education (June/July 2011)Footnote13.

When she announced her candidacy in April 2013, Bachelet declared her first commitment was to end profits in education (Tome, Citation2015, p. 194). Later in the campaign in 2013, Bachelet made explicit the role of the student protests in raising the salience of education. In her words, “I think that today in Chile there is an awareness of how essential a reform of quality education is that did not exist among the majority before … it is partly thanks to the students themselves, who were in the street for almost a year, getting the support of many people” (La Tercera, Citation2013). Bachelet’s campaign platform picked up on core student demands, including eliminating student selection, converting education into a social right (where “the right to quality education does not depend on the capacity of families to pay”), and ending copayments (Bachelet, Citation2013, pp. 16–19).

In short, beginning with the Pingüino protests in 2006, relentless waves of student protests kept education reform in the public eye and on the agenda for party and electoral mobilisation.Footnote14 The first Bachelet government tried to respond in 2009 with LGE, but this law fell short on many student demands. These shortcomings fed into a more intense wave of protests that began in 2011 and extended through Bachelet’s campaign for president in 2013.

However, while it was students who initially increased issue salience and pressured for change, it was not sufficient to force major reform. In line with PRT, redistributive change required a combination of actors on the left exercising their power. Other organisations, like the teacher union, also mobilised in the street for change. The students’ demands reverberated in public opinion, and individuals from lower socioeconomic levels used their voting power to support the left coalition that promised education reform (Navia & Castro, Citation2015).Footnote15 Once in power, Bachelet’s government used its imposing electoral mandate (62% of the vote) and majorities in Congress to prioritise education reform.

5. From electoral promise to media debates, 2014–15

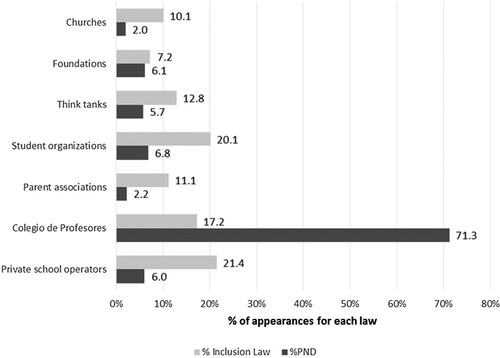

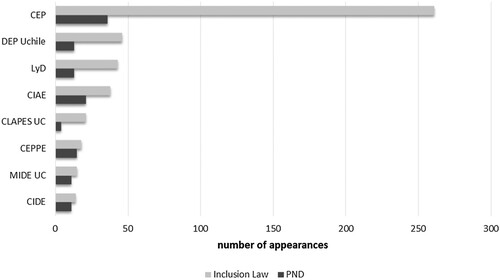

During Bachelet’s second government, key education stakeholders debated the Inclusion Law. This section measures the engagement of these reform politics by the number of times each group appeared in media reports related to the Inclusion Law.Footnote16 The number of mentions in the media does not tell us about the preferences or influence of each stakeholder, but it is a good indicator of how much stakeholders were engaged and willing to invest in making their preferences known. For example, the absence in the media, especially of business and international organisations, does correspond to their small roles in the policy process. The comparison in the graphs of PND (Política Nacional Docente, National Teacher Policy), another major education reform, with the Inclusion Law provides a benchmark and shows that many groups chose to invest much more in the latter. Overall, the media appearances are a particularly useful quantitative measure that give a concrete sense of how active interest groups and policy networks were.

provides evidence that civil society actors continued to be involved in the Inclusion Law debates during the period that the bill was in Congress. As a benchmark suggestive of the Inclusion Law’s relative importance, all groups in civil society other than the Colegio de Profesores were more visible on the Inclusion Law bill than a reform bill on teacher careers, PND. Most other countries also have well-organised teacher unions, foundations, and religious groups active in education. Where Chile differs is in its active student and parent organisations, think tanks, and associations of private schools. On the Inclusion Law the two groups most engaged were students and private schools, though on opposing sides.

Figure 4. Press Appearances by Civil Society Organisations (percentage of appearances by all groups for each law).

Over the past decades, private-voucher schools have become quite well organised. Founded in 1977, CONACEP (Corporación Nacional de Colegios Particulares, National Corporation of Private Schools) became an organisation primarily for private-voucher schools. FIDE (Federación de Instituciones de Educación Particular, Federation of Institutions of Private Education) was founded earlier in 1948 as an association of Catholic schools, but in the 1960s FIDE opened its membership to non-Catholic schools (Mizala & Schneider Citation2014). Private-voucher schools were the most powerful group in Chilean education with stalwart allies in the right-wing opposition as well as some members of the Christian Democratic Party (DC) belonging to Bachelet’s coalition (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 238, p. 242; Kubal & Fisher, Citation2016, p. 223). As noted earlier, their power was on display when, during Bachelet’s first term, they helped block a similar government proposal to outlaw profits and student selection. The Inclusion Law was designed explicitly to regulate private-voucher schools. As expected, the opposition of these associations was forceful and consistent (Mizala & Schneider Citation2019).

Other relevant civil society actors included the Colegio de Profesores, parent associations, and the Catholic Church. The Colegio organised teachers in municipal schools and supported the Inclusion Law because it reduced advantages private-voucher schools had in attracting students (and voucher financing) away from municipal schools. Some parent associations appeared 10 times more often in relation to the Inclusion Law than to PND. In fact, one of the associations emerged mainly to fight the Inclusion Law. The Catholic Church was affiliated with around a third of all private-voucher schools and cared deeply about schools being able to select students from appropriately Catholic families. The church staunchly opposed the no-selection element of the Inclusion Law.

Given the importance of policy networks in reform politics, further disaggregates foundations and think tanks. Think tanks and research centres were also more developed in Chile than elsewhere in Latin America (Mendizabal & Sample, Citation2009). A substantial group of well-established research centres were active in debates on the Inclusion Law.

Figure 5. Press Appearances by Think Tanks and Research Centres. CEP–Centro de Estudios Públicos (Centre of Public Studies), LyD – Libertad y Desarrollo (Liberty and Development), CEPPE– Centro de Estudios de Políticas y Prácticas en Educación (Centre for Research on Educational Policy and Practice) Universidad Catolica; CIAE – Centro de Investigación Avanzada en Educación (Centre for Advanced Research on Education) Universidad de Chile; CIDE – Centro de Investigación y Desarrollo de la Educación (Research Centre for Educational Development) Universidad Alberto Hurtado; CLAPES–Centro Latinoamericano de Políticas Económicas y Sociales (Latin American Centre for Economic and Social Policy) Universidad Católica; DEP-UChile – Departamento de Estudios Pedagógicos (Department of Pedagogical Studies) Universidad de Chile; MIDE Centro de Medición (Centre for Measurement) Universidad Católica.

Among think tanks, CEP (Centro de Estudios Públicos, Centre of Public Studies) appeared more frequently on the Inclusion Law than all the other centres combined. Among the think tanks, CEP and LyD (Libertad y Desarrollo, Liberty and Development) are right-wing and funded by, and closely associated with, big business. LyD opposition to Bachelet reforms was more ideological and against any restrictions on choice in the education system while CEP views were more technical and critical of elements of reform design. The many press appearances by research centres suggests a strong technical and evidence-based side to public debates, and qualitative research confirms the important role of academic arguments in the government’s public campaign for the reform (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 237).

While the impetus for, and design of, education reform came from Bachelet, press reports show that think tanks, foundations, and others in the policy network were also very engaged in often heated debates on these reforms. Business (despite its organisational depth) was conspicuous by its absence.Footnote17 Among interest groups in civil society, private school operators, student organisations, and the Colegio were the most visible on the Inclusion Law, aligned, respectively, with our arguments on privatisation (that created powerful and engaged groups of school owners, including the Church) and power resource theory (where students and the teacher union kept engaged with the reform process).Footnote18

6. Negotiations in congress and final passage into law, 2014–15

The legislative process lasted over 13 months, and 111 individuals and institutions participated in legislative debates (compared with 75 exponents during the discussion of the PND).Footnote19 The central goals of the Inclusion Law – no selection, no profits, and no copayments – were simple and straightforward, but the means to achieve them were not. It was not enough to declare all schools non-profit, because owners siphoned profits out through rental agreements (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 235). The legislation thus had to find ways to eliminate these rental profits. Likewise, it was easy to legislate that schools could not select students, but, if schools did not select, who instead would assign students to schools? The bill thus had to create a new admissions system. Finally, the challenge with eliminating co-payments was finding public replacement revenue. Both the simple goals and complicated solutions generated heated debates and disagreements among members of parliament and representatives of civil society.

In the end, though, despite the long and arduous debates and negotiations, the main thrust of the bill survived intact. The right-wing opposition in Congress, with intense backing from associations of private schools and the Catholic Church opposed nearly the entire bill. However, Chile Vamos was the minority coalition and lacked the votes to stop it. In fact, where negotiations yielded more concessions was within the Nueva Mayoría coalition where former student leaders on the left or DC members in the centre pushed for specific revisions.

Although much of the public debate centred on principles like discrimination, autonomy, and freedom to choose, the bill also had large distributional implications. Overall, the law was costly, and, as noted earlier, the government had made provisions for it in new taxes. The no selection and no copayment components had a first distributional consequence of opening up the great majority of private-voucher schools to poor families that previously could not have afforded the extra fees. More directly redistributive elements in the bill included increased values for preferential vouchers for the poorest 40 percent, a new preferential voucher for families in the middle quintiles of income distribution (40-80 percent), plus an additional per student subsidy to compensate for revenues schools would lose from ending copayments. The elimination of profits had large distributional consequences for school owners, though owners of school property were to receive market-value compensation for the buildings that schools were to purchase. In terms of PRT, Nueva Mayoría designed the Inclusion Law to substantially redistribute education resources to poorer constituents.

In all three key components of the Inclusion Law, the initial bill drew extensively on evidence from the Chilean policy network. Regarding selection, the bill pointed to evidence that Chilean schools had mechanisms for selecting students (Carrasco et al. 2014; Elacqua and Santos, 2013) and that improved results of these schools were due to the socioeconomic background of students and not the effectiveness of schools (Carrasco et al. 2014; Valenzuela y Allende 2012; MacLeod y Urquiola 2009; Contreras et al. 2011) (as cited in Bachelet, Citation2014b).

In Congress, the discussion of admissions and student selection focused on two disputes: non-discrimination versus freedom to choose, and social integration versus meritocracy. According to the Bachelet administration and supporters, prohibiting student selection would end discrimination against poorer students. In opposition, some parent organisations argued that randomising the selection process for oversubscribed schools restricted parent rights to select the best school for their children, as argued by the President of the Confederation of Parents of Private-Voucher Schools (CONFEPA), Erika Muñoz, in her presentation at the Chamber of Deputies.Footnote20 The opposition Chile Vamos coalition, as well as some DC senators, supported selection for academic merit and talent for artistic or sports schools (Holz & Medel, Citation2017).

On profits, the Inclusion bill pointed to evidence from academic studies in Chile that: 1) the opportunity for education establishments to profit had not led to a higher quality system (Zubizarreta, Paredes y Rosembaum 2014; Elacqua 2009; Elacqua 2011), and 2) for-profit private schools in Chile generally performed worse or the same as not-for-profit private schools. Internationally, the research showed that for-profit schools had performed the same or worse as public schools (Contreras et al. 2011; Salgren 2010), and were not more innovative (Levin 2002) (as cited in Bachelet, Citation2014b). A major implementation issue was regulating how school owners would get 12-year mortgages through the banking system (with government guarantees) to purchase their buildings. Invoking their structural power, CONACEP and other representatives of private voucher schools warned that requiring purchases could force some schools to close, and hundreds of private-voucher schools around the country confirmed this dire forecast (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 238).Footnote21

On copayments, the Inclusion bill’s introduction points to evidence that copayments increased segregation (Valenzuela et al., Citation2013; Elacqua, 2013; Flores and Carrasco, 2013; Gallegos and Hernando, 2009) without significantly contributing to quality (Mizala 2012; Valin, 2011; Saavedra, 2013) (as cited in Bachelet, Citation2014b). The opposition acknowledged the segregating effect of the copayment, but Chile Vamos, as well as parent groups like the CONFEPA, argued that copayments were a legitimate way for parents to demonstrate their commitment to their children and to support school quality for all. In October 2014, some parent groups even took to the streets – like so many students before them – for marches against eliminating copayments.Footnote22

On implementation, representatives of private-voucher schools and their affiliates (CONACEP, the Evangelical Church, the educational representative of the Archbishop of Santiago) claimed that the proposed increase in government subsidies would not be sufficient to replace parent fees, so the quality of schools would suffer (Holz & Medel, Citation2017; Report of the Education Commission Citation2014). The Catholic Church was also deeply involved in private-voucher schools (over a third were religious, mostly Catholic (Mizala & Torche Citation2012, p. 133) and opposed much of the bill. They expressed their worry about the elimination of the copayment, and the Episcopal Conference of Chile – an organisation of the country’s Catholic bishops – argued generally for school autonomy and against undue government interference.

In the elite institutional space of Congress, students, social movements, and poorer voters of PRT were not as active except through their elected representatives. More in evidence were interest groups (including the Catholic Church and the private education sector) and policy networks. Despite instances of intense opposition from multiple civil society actors and legislators from all sides (right-wing opposition, independent left, and in some cases from within the Nueva Mayoría coalition), the Bachelet government was able to get a law passed that maintained the three principal tenets of the original legislation that thoroughly reformed private-voucher schools, greatly extended government regulation of education, and that substantially allocated education resources to poorer families. After Bachelet’s term, the right-wing Piñera government (2018-22) wanted to change a lot in the Inclusion Law, but did not have the votes in Congress.

Conclusions

While the effects of some components were more immediate (no profits), effects on social segregation will take longer as new students enter the education system under the new rules. Social segregation is also difficult to reverse because most of it occurs among private-voucher schools (OECD Citation2019). And, some components phase in only gradually so that, for example, families still cannot choose between all the schools with public financing, because 15% of private-vouchers schools, which represent around 19% of total enrolment, still charge copayments.Footnote23

Still, researchers have noticed some progress. According to PISA data between the years 2009 and 2018, the strength of the relationship between education performance and socioeconomic background of students declined from above the OECD average to not statistically different (OECD Citation2010 & OECD Citation2019). The new School Admission System (SAE), a key component of the Inclusion Law, decreased by 16% the quality gap between the schools which poor and non-poor students attend, a positive effect comparable in magnitude to that of lengthening the school day in the 1990s (Asahi et al., Citation2021).

At the time, the Inclusion Law was one of the biggest legislative reversals of Pinochet-era neoliberal reforms, and the Bachelet government had to overcome staunch opposition to the Inclusion Law. This legislative coup is particularly remarkable in Chile in light of the comparatively high instrumental power of business elites and right-wing parties, and their policy wins in other areas. For example, cohesive business elites with strong ties to right parties thwarted attempts to raise taxes during the Lagos administration and helped keep tax reform off the agenda during first Bachelet administration (Fairfield Citation2015). Similarly, elite influence and the significant power of conservative sectors in Chile limited social security and health reform in Chile in the 2000s (Garay, Citation2016). The private pension funds warded off long-standing popular demands for reform (Bril-Mascarenhas & Maillet, Citation2019). Thus, overcoming opposition from right-wing parties, the private sector, and conservative groups in civil society in education was no mean feat.

What political factors made the passage of the Inclusion Law possible? The main factors that propelled the law were, in sequential and descending order of impact, student protests (social movement), electoral mandate (PRT), and policy networks. The student protests in the eight years prior to the second Bachelet government kept issues like banning selection, profits, and copayment at the centre of political debate and electoral competition. Counterfactually, without these protests, education probably would not have figured so centrally in Bachelet’s campaign, as neglect of education is the more common pattern in the rest of the region (Bruns, MacDonald, and Schneider Citation2019). Without the protests and electoral mandate, evidence of the need for reform from the policy network would not have been enough to overcome the forceful opposition in civil society and Congress. However, without the research and empirical evidence by members of the policy network regarding the voucher model, the specifics of the reform could have looked quite different.

Support for Bachelet and the Inclusion Law – especially the ban on profits – came from Chileans at all income levels, though support was concentrated among poorer voters. With higher taxes on the wealthy, and more resources for poor students, the Inclusion Law and associated tax hike were broadly redistributive. In broad brush strokes, this pattern fits power resource theory, though without strong overall union organisation characteristic of European cases. As noted earlier, the Colegio de Profesores, one of the largest and best organised labour associations in Chile, supported the law. However, relatively few workers in the rest of the economy are unionised.

Chile’s Inclusion Law is relevant in comparative contexts outside of Chile. Section III compared Chile to other democratic countries with national school choice systems in terms of the features of their voucher systems and the levels of contentiousness. Furthermore, although Chile’s education system may be extreme in its extent of privatisation, its experience nonetheless can hold potentially valuable lessons for other countries. The world-wide trend is toward larger enrolments in various kinds of private schools (Elacqua et al., Citation2018; Verger et al., Citation2018). Private education, often government subsidised, is growing across middle-income and low-income countries: from Argentina (Narodowski & Moschetti, Citation2015) to India (Jain et al., Citation2018). These and other countries are likely to confront some of the same actors and issues as in Chile as their education systems shift private. The emergence of new, sometimes well-organised, private actors in education is likely to make government regulation necessary, as well as contentious and complicated (Bellei, Citation2016).

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Andrea Campbell and Martin Liby Troein for comments on earlier versions. Schneider thanks J-WEL for research support.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Zancajo et al.’s (Citation2021) review of the literature provides international evidence that private subsidised schools worsen equity.

2 See Mizala and Torche (Citation2017) for a description of the preferential voucher.

3 Copayments were an additional monthly amount that some private-voucher schools charged to families over and above the government voucher. Copayments expanded rapidly from 16 percent of the private-voucher schools’ enrolments in 1993 to about 80 percent in 1998, stabilising thereafter (Mizala & Torche, Citation2017).

4 Increasing numbers of private-voucher schools took out full page newspaper ads claiming they would have to close. See Appendix C.

5 Zancajo (Citation2019a, p. 2017) argues that the students and others were also able “to develop discursive frames initiating profound debate on the education system model.” Donoso (Citation2020) also notes an ideational shift in the education debate because of the student protests. Regarding organisational factors, Snow et al.’s (Citation1986) concept of frame bridging – in which social movement organisations connect to ideologically receptive but previously unconnected individuals and groups – applies to the case of the student movement in Chile. Both the 2006 and 2011 student movements built linkages with previously demobilised or organisationally separate actors in order to form a more cohesive, massive, and confrontational movement.

6 Palacios-Valladares and Ondetti (Citation2019) provide details on how the student movement pushed the Nueva Mayoria and its policy platform left.

7 The CEP National Survey of Public Opinion is an academic analysis of the population's political, economic and social attitudes and perceptions. In 1998, CEP joined the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP), an international collaboration that conducts annual surveys on various topics related to the social sciences. CEP’s sampling method is random and probabilistic in each of its three stages (block-house-person) and is completely face to face. To date, 86 surveys have been carried out since 1987. For more information, see: https://www.cepchile.cl/opinion-publica/encuesta-cep/.

8 The insider perspective was of course from the side of the government, so we have tried to cover many of the criticisms and opposition to the reforms to counterbalance possible bias.

9 The most relevant policies to encourage school choice are vouchers, charter schools, and supply-side subsidies for private schools. Many other countries have some educational vouchers, but are only partial or targeted at particular groups or schools rather than system-wide.

10 For more discussion of the Dutch school choice system, see Ladd et al. (Citation2010); on Sweden, Bunar (Citation2010); on New Zealand, Maani (Citation2017); and on Denmark, Justesen (Citation2002).

11 In Sweden, poorer municipalities may get more funding, but the extra funds do not follow individual students.

12 Our interest is not in explaining the causes of student protests but rather in their consequences and impact on the reform process for the Inclusion Law.

13 The figures draw on surveys administered by the Santiago-based think tank, Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP). See Appendix B for a description of how the income categories were determined, and a note on potential bias on the copayments question.

14 Zancajo (Citation2019a) and Muñoz & Weinstein (Citation2020) also highlight the important role of the student mobilizations in pressuring for Bachelet’s education reform.

15 Although subject to the usual ecological caveats, a strong correlation exists across voting districts between the vote share for Bachelet and the percent of poor residents (Contreras & Morales, Citation2013). Rich districts in particular did not vote for Bachelet, making it easier to ignore parental opposition to the Inclusion Law.

16 The quantitative press analysis uses a daily press briefing prepared for the Ministry of Education to describes all actors involved in the discussion of the Inclusion Law and the relative importance of each of them. We reviewed the 1,153 press briefings from 2014 and 2015 when the Inclusion Law and the PND (Politica Nacional Docente) Law were designed and debated in Congress. These reports included references from many different written sources (newspapers, including online newspapers, magazines, etc.) and so have an advantage over using a single periodical that might bias reporting to concentrate on only certain actors.

17 Most of the national sectoral associations stayed out of the press, and only the peak-level confederation, CPC (Confederación de la Producción y del Comercio, Confederation for Production and Commerce), appeared, but only 38 times, far below all the other groups in civil society.

18 In another analysis, media coverage skewed negative. Of all news items on the Inclusion Law, 14% were positive and 23% negative, for a net favorability of -9 (other stories were neutral (Molina, Citation2017, p. 184). Among media, TV news had the most negative coverage ranging from -26 to -52 across major channels. These ratings give a better sense of the uphill struggle to pass the Inclusion Law.

19 For full reviews of these debates, see Holz and Medel (Citation2017) and Bellei (Citation2016).

20 Session 25, July 14, 2014, Report of the Education Commission, Chamber of Deputies, Bulletin No. 9366-04. Formed specifically to oppose the Inclusion Law, CONFEPA represents 2,400 parent associations nationwide (Bellei, Citation2016, p. 240).

21 Appendix C includes copies of newspaper ads threatening school closures. Other key actors opposing the end of profits were Corporación Aprender and COREDUC.

22 “Marchan en Chile contra reforma educativa” https://www.milenio.com/internacional/marchan-en-chile-contra-reforma-educativa.

23 There is also a shortage of quality educational supply in some areas of the country. The most prestigious schools are in excess demand; 74% of applicants in the 2020 admission process applied to a school with excess demand as their first option. At the same time there is excess supply (two vacancies for each applicant). Thus, some researchers point to the need to improve the territorial planning of education in Chile (Amaya et al., Citation2021).

References

- Amaya, J., Canals, C., Mizala, A., Rodríguez, P., Uribe, P., & Valenzuela, J. P. (2021). Policy brief: Planificación territorial de la oferta escolar pública: avanzando en sustentabilidad y equidad. Universidad de Chile. https://doi.org/10.34720/01sb-0b03.

- Ansell, B. W. (2010). From the ballot to the blackboard: The redistributive political economy of education. Cambridge University Press.

- Asahi, K., Baloian, A., & Figueroa, N. (2021). Sistema de Admisión Escolar en Chile: efecto sobre la equidad y propuestas de mejora. In I. En Irarrázaval, E. Piña, y I. Casielles (Eds.), Propuestas para Chile. Concurso Políticas Públicas 2020 (pp. 79–106). Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

- Bachelet, M. (2013). “Chile de todos. Programa de gobierno Michelle Bachelet, 2014-2018.” http://www.subdere.gov.cl/sites/default/files/noticias/archivos/programamb_1_0.pdf.

- Bachelet, M. (2014a). “Mensaje Presidencial.” Presidential Address on May 21, 2014. https://www.camara.cl/camara/doc/archivo_historico/21mayo_2014.pdf.

- Bachelet, M. (2014b). “Mensaje No. 131-362: Mensaje que inicia Proyecto de Ley que regula la admisión de los y las estudiantes, elimina el financiamiento compartido y prohíbe el lucro en establecimientos educacionales que reciben aportes del Estado.” May 19, 2014. http://archivospresidenciales.archivonacional.cl/index.php/mensaje-que-inicia-proyecto-de-ley-que-regula-la-admision-de-los-y-las-estudiantes-elimina-el-financiamiento-compartido-y-prohibe-el-lucro-en-establecimientos-educacionales-que-reciben-aportes-del-estado.

- Bellei, C. (2016). Dificultades y Resistencias de Una Reforma Para Des-Mercantilizar La Educación. Revista de La Asociación de Sociología de La Educación (RASE), 9(2), 232–247. Universidad Complutense de Madrid.

- Bellei, C., Cabalin, C., & Orellana, V. (2014). The 2011 Chilean student movement against neoliberal educational policies. Studies in Higher Education, 39(3), 426–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.896179

- Bertoni, E., Elacqua, G., Jaimovich, A., Rodriguez, J., & Santos, H. (2018). Teacher policies, incentives, and labor markets in Chile, Colombia, and perú: Implications for equality. Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/en/teacher-policies-incentives-and-labor-markets-chile-colombia-and-peru-implications-equality (January 12, 2021).

- Bril-Mascarenhas, T., & Maillet, A. (2019). How to build and wield business power: The political economy of pension regulation in Chile, 1990–2018. Latin American Politics and Society, 61(1), 101–125. https://doi.org/10.1017/lap.2018.61

- Bunar, N. (2010). Choosing for quality or inequality: Current perspectives on the implementation of school choice policy in Sweden. Journal of Education Policy, 25(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680930903377415

- Bruns, B., Macdonald, I. H., & Schneider, B. R. (2019). The politics of quality reforms and the challenges for SDGs in education. World Development, 118, 27-38.

- Burstein, P. (1998). Discrimination, jobs, and politics: The struggle for equal employment opportunity in the United States since the New Deal. University of Chicago Press.

- Burton, G. (2012). Hegemony and frustration: education policy making in Chile under the Concertación, 1990–2010. Latin American Perspectives, 39(4), 34-52.

- Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP). (2011a). Estudio Nacional de Opinión Pública N° 64, Junio-Julio 2011. Centro de Estudios Públicos.

- Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP). (2011b). Estudio Nacional de Opinión Pública N° 65, Noviembre-Diciembre 2011. Centro de Estudios Públicos.

- Contreras, G., & Morales, M. (2013). “Precisiones sobre el sesgo de clase con voto voluntario.” CIPER. November 22, 2013. https://www.ciperchile.cl/2013/11/22/precisiones-sobre-el-sesgo-de-clase-con-voto-voluntario/.

- Cooke, H., Sharma, A., & Wiltshire, L. (2020). “Election 2020: Labour promises more school lunches, won’t extend fees-free programme.” Stuff. https://www.stuff.co.nz/national/politics/300107419/election-2020-labour-promises-more-school-lunches-wont-extend-feesfree-programme.

- Culpepper, P. D. (2011). Quiet politics and business power: Corporate control in Europe and Japan. Cambridge University Press.

- DIPRES. (2014). Informe Financiero Sustitutivo, I.F. N°84-08.09. Ministerio de Hacienda de Chile.

- Disi, R. (2018). Sentenced to debt: Explaining student mobilization in Chile. Latin American Research Review, 53(3), 448–465. https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.395

- Donoso, A. (2020). Movimiento estudiantil chileno de 2011 y la lógica educacional detrás de su crítica al neoliberalismo. Educação e Pesquisa, 46, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1678-4634202046

- Donoso, S. (2013). Dynamics of change in Chile: Explaining the emergence of the 2006 Pingüino movement. Journal of Latin American Studies, 45(1), 1–29. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0022216X12001228

- Elacqua, G. (2012). The impact of school choice and public policy on segregation: Evidence from Chile. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(3), 444–453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.08.003

- Elacqua, G., Iribarren, M. L., & Santos, H. (2018). Private schooling in Latin America: Trends and public policies. Technical Note N° IDB-TN-01555. Inter-American Development Bank. https://publications.iadb.org/en/handle/11319/9259.

- Fairfield, T. (2015). Private wealth and public revenue in Latin America: Business power and tax politics. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Friedman, M. (1962). Capitalism and freedom. University of Chicago Press.

- Gajardo, S. V. (2011). El resplandor de las mayorías y la dilatación de un doble conflicto: El movimiento estudiantil en Chile el 2011. Anuario del conflicto social, 1(1), 286–309. https://revistes.ub.edu/index.php/ACS/article/view/6256.

- Garay, C. (2016). Social policy expansion in Latin America. Cambridge University Press.

- Guzman-Concha, C. (2012). The students' rebellion in Chile: Occupy protest or classic social movement?. Social movement studies, 11(3-4), 408-415.

- Grau, N., Hojman, D., & Mizala, A. (2018). School closure and educational attainment: Evidence from a market-based system. Economics of Education Review, 65, 1-17.

- Hofflinger, A., & von Hippel, P. (2020). Does achievement rise fastest with school choice, school resources, or family resources? Chile from 2002 to 2013. Sociology of Education, 93(2), 132–152. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038040719899358

- Holz, M., & Medel, C. (2017). El debate parlamentario y de los actores sociales en sede legislativa. In El primer gran debate de la reforma educacional: Ley de inclusión escolar (pp. 134–169). Ministerio de Educación de Chile.

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2010). Development and crisis of the welfare state: Parties and policies in global markets. University of Chicago Press.

- Huber, E., & Stephens, J. D. (2012). Democracy and the left: Social policy and inequality in Latin America. University of Chicago Press.

- Inzunza, J., Assael, J., Cornejo, R., & Redondo, J. (2019). Public education and student movements: The Chilean rebellion under a neoliberal experiment. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 40(4), 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2019.1590179

- Jain, M. (2018). Public, private and education in India: A historical overview. In M. Jain, A. Mehendale, R. Mikhopadhyay, Sarangapani, & C. Winch (Eds.), School education in India: Market state and quality (31-66). NewDelhi: Routledge India.

- Justesen, M. K. (2002). Learning from Europe: The Dutch and Danish school systems. Adam Smith Institute.

- Karsten, S. (1999). Neoliberal education reform in The Netherlands. Comparative Education, 35(3), 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050069927847

- Korpi, W. (1978). The working class in welfare capitalism: Work, unions and politics in Sweden. Routledge & Kegan Paul.

- Korpi, W. (1989). Power, politics, and state autonomy in the development of social citizenship: Social rights during sickness in eighteen OECD countries since 1930. American Sociological Review, 54(3), 309–328. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095608

- Kubal, M. R., & Fisher, E. (2016). The politics of student protest and education reform in Chile: Challenging the neoliberal state. The Latin Americanist, 60(2), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1111/tla.12075

- Lara, B., Mizala, A., & Repetto, A. (2011). The effectiveness of private voucher education: Evidence from structural school switches. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis, 33(2), 119–137.

- La Tercera. (2013). “Bachelet defiende la gestión en educación de su gobierno y afirma que entiende la desconfianza de los estudiantes” La Tercera. Sep. 17, 2013. Available at: https://www.latercera.com/noticia/bachelet-defiende-la-gestion-en-educacion-de-sugobierno-y-afirma-que-entiende-la-desconfianza-de-los-estudiantes/.

- Ladd, H. F., Fiske, E. B., & Ruijs, N. (2010). “Parental choice in The Netherlands: Growing concerns about segregation.” Stanford working paper series, SAN10-02. Stanford School of Public Policy.

- Maani, S. A. (2017). “Policy experimentation and impact evaluation: The case of a student voucher system in New Zealand.” Iza policy paper No. 137. IZA Institute of Labor Economics.

- Mendizabal, E., & Sample, K. (2009). Dime a quién escuchas … Think tanks y partidos en América Latina. ODI-IDEA.

- Miller, H. T., & Demir, T. (2007). Policy communities. In F. Fischer & G. J. Miller (Eds.), Handbook of public policy analysis (pp. 163–174). Routledge.

- Mizala, A., & Torche, F. (2012). Bringing the schools back in: the stratification of educational achievement in the Chilean voucher system. International Journal of Educational Development, 32(1), 132-144.

- Mizala, A., & Torche, F. (2017). Means-tested school vouchers and educational achievement: Evidence from Chile’s universal voucher system. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 674(1), 163–183.

- Mizala, A., & Schneider, B. (2019). Promoting quality education in Chile: the politics of reforming teacher careers. Journal of Education Policy, 35(4), 529–555. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2019.1585577

- Mizala, A., & Schneider, B. R. (2014). Negotiating education reform: teacher evaluations and incentives in Chile (1990–2010). Governance, 27(1), 87–109.

- Molina, S. (2017). La cobertura mediática durante la tramitación de la Ley de Inclusión Escolar. In El Primer Gran Debate de La Reforma Educacional: Ley de Inclusión Escolar (pp. 170–201). Ministerio de Educación de Chile.

- Muñoz, G., & Weinstein, J. (2020). Ley de inclusión: el difícil proceso para redefinir las reglas del juego de la educación particular subvencionada en Chile. In Carlos Ornelas (Ed.), Política educativa en América Latina: Reformas, resistencia y persistencia. Chapter 3. Siglo XXI Editores.

- Narodowski, M., & Moschetti, M. (2015). The growth of private education in Argentina: evidence and explanations. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 45(1), 47–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2013.829348

- Navia, P., & Castro, I. S. (2015). It’s not the economy, stupid.¿Qué tanto explica el voto económico los resultados en elecciones presidenciales en Chile, 1999-2013? Política, 53(1), 161–186. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-5338.2015.38154

- OECD. (2010). PISA 2009 Results: What Students Know and Can Do: Student Performance in Reading, Mathematics and Science, Vol. I. OECD Publishing. http://doi.org/10.1787/9789264091450-en

- OECD. (2019). PISA 2018 Results (Volume I): What Students Know and Can Do, PISA. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/5f07c754-en

- Palacios-Valladares, I., & Ondetti, G. (2019). Student protest and the Nueva Mayoría reforms in Chile. Bulletin of Latin American Research, 38(5), 638–653. https://doi.org/10.1111/blar.12886

- Refslund, B., & Arnholtz, J. (2021). Power resource theory revisited: The perils and promises for understanding contemporary labour politics. Economic and Industrial Democracy, 43(4), 1–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0143831X211053379

- Report of the Education Commission, N° 9366-04. (2014). Chamber of Deputies of the Republic of Chile. https://www.camara.cl/verDoc.aspx?prmID=12697&prmTipo=INFORME_COMISION.

- Rhodes, R. A. (2006). “Policy network analysis.” The Oxford Handbook of Public Policy.

- Ruíz, C. (2007). ¿Qué hay detrás del malestar con la educación? Revista Análisis del Año, 9, 33–72.

- Silva, B. (2007). La ‘Revolución Pingüina’ y el cambio cultural en Chile. CLACSO.

- Silva, E. (2017). Post-transition social movements in Chile in comparative perspective. In S. Donoso, & M. v. Bülow (Eds.), Social movements in Chile: Organization, trajectories, and political consequences (pp. 249–280). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Snow, D. A., Burke Rochford Jr, E., Worden, S. K., & Benford, R. D. (1986). Frame alignment processes, micromobilization, and movement participation. American Sociological Review, 51(4), 464–481. https://doi.org/10.2307/2095581

- Tome, C. (2015). ¡No lucro! … from protest catch cry to presidential policy: Is this the beginning of the end of the Chilean neoliberal model of education? Journal of Educational Administration and History, 47(2), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220620.2015.996865

- “Tomorrow’s Schools Review.”. (2019). Conversation. New Zealand Government. https://conversation.education.govt.nz/conversations/tomorrows-schools-review/.

- Valenzuela, J. P., Bellei, C., & de los Ríos, D. (2013). Socioeconomic school segregation in a market-oriented educational system. The case of Chile. Journal of Education Policy, 29(2), 217–241. https://doi.org/10.1080/02680939.2013.806995

- Verger, A., Moschetti, M., & Fontdevila, C. (2018). The expansion of private schooling in Latin America: Multiple manifestations and trajectories of a global education reform movement. In K. Saltman, & A. Means (Eds.), The wiley handbook of global educational reform (pp. 131–155). John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

- Walgrave, S., & Vliegenthart, R. (2012). The complex agenda-setting power of protest: Demonstrations, media, parliament, government, and legislation in Belgium, 1993-2000. Mobilization: An International Quarterly, 17(2), 129–156. https://doi.org/10.17813/maiq.17.2.pw053m281356572h

- Zancajo, A. (2019a). “Drivers and hurdles to the regulation of education markets: The political economy of Chilean reform”. Working paper 239. National center for the study of privatization in education, Teachers College, Columbia University.

- Zancajo, A. (2019b). Education markets and schools’ mechanisms of exclusion: The case of Chile. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 27. https://doi.org/10.14507/epaa.27.4318

- Zancajo, A., Fontdevila, C., Verger, A., & Bonal, X. (2021). Regulating Public-Private Partnerships, governing non-state schools: An equity perspective. United Nations Education, Scientific and Cultural Organization.

Appendix A.

Timelines Related to Inclusion Law

Appendix B.

Public Opinion Figures on Profits and Copayments

and draw on survey responses from the Centro de Estudios Públicos (CEP) surveys administered in June/July and November/December 2011. Regarding income, the surveys ask respondents to group themselves into 1 of 14 income ranges, in addition to giving respondents the options of “Don’t Know” or “Don’t Answer.” From the 14 income brackets, the authors regrouped respondents into the categories of high income, upper-middle income, lower-middle income, and low income. The high-income range includes individuals who report earning 1,271 USD per month or more, largely falling within the ABC 1 category, which represents about 6 percent of the respondents without considering the “Don’t Know/Don’t Answer” category. The upper-middle income group includes individuals who report earning between 370 and 1,271 USD per month, approximately the C2 category, which represents 27 percent of those who reported income. The lower-middle income group includes individuals who report earning between 227 and 370 USD per month, the C3 category, which represents 26 percent of those who reported income. The low-income group includes individuals who reported earning 226 USD per month or less, the D and E socioeconomic groups, which represents 42 percent of those who reported income in the survey.

It is also worth noting what might be a slight bias in favour of allowing copay in the CEP survey question. The question asks respondents if parents should be able to complement the State educational subsidy with a copay “to improve the education of their children.” The problem with this wording is that part of the argument in favour of the copay is improved education outcomes for children, so the authors think this phrasing should have been left out and may have increased the percentage of respondents who indicated support for copayments.

Appendix C:

Newspaper ads of private-voucher schools

El Mercurio, October 19th, 2014 “Schools forced by the reform to close or become private paid schools”

El Mercurio, October 26th, 2014 “Schools forced to close or become private paid schools due to the reform continue to add up”

El Mercurio, November 2nd, 2014 “Schools forced to close or become private paid schools because of the reform continue to add up”