ABSTRACT

This article reports the findings of a multi-site qualitative study of 31 Chinese homeschooling families in Taipei and Hong Kong. Homeschooling, a significant source of inspiration for school innovation, has been growing around the globe in recent years, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic highlighting the challenges facing mainstream schools. The findings reveal that the families under study chose to homeschool their children mainly because they were dissatisfied with mainstream schools in the Chinese context, which, as they described, were not sufficiently child-centric. Notably, their homeschooling practices were highly diversified and hybridised, including a variety of organisational methods, actors, and materials. Based on lessons learned from homeschooling, the findings indicate the need for mainstream schools to reimagine their relations with families and the outside world in terms of pedagogic time, space, relations, and resources to better respond to every student’s unique needs as well as the challenges ahead in the post-pandemic world.

Introduction

More than three decades ago, an American sociologist, Maralee Mayberry, in an article published in Educational Review (Citation1989), called for more policy and research on “building alliances between home schools and public schools” (p. 179). Despite social, cultural, and technological transformations in educational contexts across the globe over the intervening years, the importance of this call remains, particularly in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic. During COVID-19, mass school closures forced millions of children to learn at home, triggering a rethink about the role played by schools and families regarding the education of youth. During school closures, supporting children’s online learning at home often fell on the shoulders of parents and caregivers; younger children especially were less able to study independently (Lee, Citation2022). One aftershock of the pandemic has been an intensified focus on home-based learning and its implications for school models (Fletcher et al., Citation2022; Manca & Meluzzi, Citation2020). For example, based on a systematic review of the results of 81 studies of secondary schools from 38 countries, Bond and her colleagues (Citation2021) contend that the mode of home-based learning developed during COVID-19 may be a good complement to traditional methods of schooling. Further, an increasing number of parents in countries such as the US and UK have switched to homeschooling their children after the pandemic (Thompson, Citation2022).

Against this backdrop, the present qualitative study aims to uncover the implications of this rise in homeschooling to enlighten school policies and practices by investigating the views and experiences of Chinese homeschooling families in two Chinese cities – Taipei and Hong Kong. The growing phenomenon of homeschooling around the globe in recent years can be seen as a promising source of inspiration for school innovation (McShane, Citation2021). Specifically, any lessons learned from homeschooling may be used to help reimagine mainstream school models in the post-pandemic era. The Chinese context, where education has long been narrowly viewed as taking place in brick-and-mortar schools with standards-based curricula, teacher-centred pedagogy, and high-stakes testing (Chen, Citation2015; Ng & Wei, Citation2020), appears to provide a particularly appropriate lens for this reimagination.

Homeschooling as an educational choice

“Homeschooling” is difficult to define precisely because the term is historically, socially, and culturally bound (Greenwalt, Citation2019). However, for the purposes of this study, the focus is on elective and secular homeschooling, which, broadly construed, refers to an educational choice deliberately exercised by parents or guardians who assume sole responsibility for their children’s education, partially or entirely substituting attendance at institutional schools (Ray, Citation2022). In this sense, although media reports often describe pandemic-induced home learning as being identical to homeschooling (Lim, Citation2020), the term is misleading because during COVID-19, children and their families had no choice but to learn at home due to school closures. The shift to primarily relying on home-based learning during COVID-19 was involuntary, improvised and contingentFootnote1. Therefore, the problems related to physical and mental health, socialisation, and other learning difficulties experienced by students during school closures should not be considered typical of homeschooling, nor as an expression of educational choice.

Homeschooling as an educational choice is not a new topic. There are longstanding debates over this practice (Gaither, Citation2016). Critics have long voiced concerns over several risks and detrimental effects linked to homeschooling (Dwyer & Peters, Citation2019; Kunzman & Gaither, Citation2020). The concerns often raised are: (a) lacking regulations, which might result in children’s isolation from their peers and society at large (West, Citation2009); (b) privileging parental rights over children’s rights in education (Bartholet, Citation2020); (c) increasing risks of child abuse and maltreatment (Bartholet, Citation2020); (d) lacking reliable data on educational outcomes of homeschooled children (Reich, Citation2008); (e) undermining the social functions of education, such as fostering citizenship (Apple, Citation2000; Reich, Citation2002); (f) increasing mothers’ role strains and risks of emotional burnout (Lois, Citation2013); and (g) exacerbating existing social class inequality in education (Lubienski, Citation2003). Alternatively, proponents of homeschooling have attempted to address this long line of criticisms by providing more context and evidence around the debates (e.g. Hamilton, Citation2022; Isenberg, Citation2007; Kunzman, Citation2012; Kunzman & Gaither, Citation2020; Murphy, Citation2014; Ray & Shakeel, Citation2023). Despite myriad opinions, homeschooling has received increasing social and legal acceptance in the US, UK, Australia and many other countries in recent years (Gaither, Citation2016; Hamilton, Citation2022; Kunzman & Gaither, Citation2020).

Contemporary homeschooling: diversity, flexibility, and hybridity of educational models and practices

The dominant conception derived from most debates surrounding homeschooling is that institutional schooling and homeschooling are strongly binary (Howell, Citation2013; Kunzman & Gaither, Citation2020; Saiger, Citation2016). However, homeschooling varies considerably, hardly making the binary conception valid in practice. There has been a trend among homeschooling families worldwide towards hybridisation and diversification in demographics, motivations, and educational approaches (Gaither, Citation2016; Hirsh, Citation2019; Jolly & Matthews, Citation2020; McShane, Citation2021; Wearne, Citation2019). Homeschooling in many regions is mainly motivated by ideological reasons, such as religious beliefs, and pedagogical reasons, such as dissatisfaction with existing school models and practices (Green-Hennessy & Mariotti, Citation2023; Maxwell et al., Citation2020; McIntyre-Bhatty, Citation2008; Slater et al., Citation2022). Homeschooling families have increasingly adopted both school-based and non-school-based educational approaches (Cheng & Hamlin, Citation2023; Saiger, Citation2016). Children who are homeschooled do not necessarily detach themselves from institutional schools. According to the 2016 National Household Education Surveys Program (NHES) data, nearly one-fifth (18%) of homeschooled students in the US also go to public schools, private schools, or universities to receive education (less than 25 hours per week), and approximately one-third (32%) of homeschooled students’ learning materials include curriculums and books adopted in public or private schools (Cui & Hanson, Citation2019). In some American states, children being homeschooled can register at mainstream schools in their respective school district so that they can receive public funds and flexibly participate in various learning activities such as classroom lessons, enrichment activities, and inter-school competitions (Hirsh, Citation2019; Saiger, Citation2016). Similarly, authorities in Taiwan offer benefits and subsidies for homeschooling families, allowing them flexibility and autonomy regarding the public financial support for their children’s education (Enforcement Act, Citation2018). Indeed, in many cases, homeschooling does not exclude, confront, or replace mainstream school education, but rather, is combined with it to form a “hybrid” model (McShane, Citation2021). Several innovative forms of hybrid schools exist in the US, such as the Charter Hybrid Homeschool, virtual charter schools, homeschool cooperatives (called “co-ops”), and micro-schools (McShane, Citation2021; Saiger, Citation2016; Wearne, Citation2019). Further, homeschoolers are often embedded in a complex network of homeschool support groups, including educational, civic, religious and cultural organisations, homeschool hubs, co-ops, virtual support groups, friendship circles, and extended families (Kunzman & Gaither, Citation2020; McShane, Citation2021).

Largely because of the Internet, many curricular and pedagogical options are now available to homeschooling families (Gaither, Citation2016; Jolly & Matthews, Citation2020). Considering the diverse contemporary context of homeschooling families, Jolly and Matthews (Citation2020) proposed what they call a “homeschool staircase framework” that defines homeschooling “based on a continuum that takes into consideration both the what of school and the how of schooling that homeschooling families employ” (p. 276). According to this framework, content, pedagogy, and curriculum can concurrently be transitioned along the autonomy continuum in relation to parental control. In a study of Australian homeschooling families, Burke and Cleaver (Citation2019) identified five specific strategies that home-educating parents adopted: Child-led learning, Resource-led learning, Outsourcing, Collaboration with other homeschooling families, and Integration of the arts. In another study of homeschooling families in the southern US, Carpenter and Gann (Citation2016) found increased flexibility in scheduling arrangements and a wide range of choices of instruction and curriculum during a typical homeschool day.

“Disruptively” innovating school education: lessons from Chinese homeschooling families

What can today’s schools learn from homeschooling models? Schooling encompasses a broad spectrum of forms; at one end, children’s education is fully controlled by the family (i.e. homeschooling), while at the other end institutional schools (i.e. public or private schooling) take the prime responsibility for children’s education (Neuman & Aviram, Citation2003). In this article, I contend that many possibilities between these two ends of the schooling spectrum can be unlocked by “disruptive innovations”, which “disrupt or overturn the traditional methods and practices” that have long been used in schools (Sornson, Citation2018, p. 9). Studies have revealed how homeschooling practices can facilitate individual and systemic reflections while stimulating innovative ideas benefitting public and private school models of education (Dahlquist et al., Citation2006; Isenberg, Citation2007; Neuman, Citation2019). Many concerns and goals of both homeschooling and institutional schooling coincide, such as how to: 1) respond and cater to learner diversity; 2) foster intrinsic motivation; and 3) realise personalised, curiosity-driven life-long learning (Neuman & Oz, Citation2021; Tan, Citation2020). Notably, shifting the conventional one-size-fits-all model to a personalised model of education is one common goal of today’s school reforms (Rose, Citation2016; Sornson, Citation2018).

In this connection, contemporary homeschooling in Chinese cities constitutes a strategic case for exploring school innovation. Schooling in Chinese cities has traditionally tended to be institutionally dominated. In Chinese society, the school occupies almost all the time in a student’s life. Chinese parents have traditionally passed on the responsibility of educating their children entirely to the school (Ng & Wei, Citation2020). The parents often expect the school to give them clear instructions on how to support their children’s education at home (Ng, Citation2007). However, in recent years, there has been a rising demand in Chinese cities for various non-traditional educational models, such as Montessori, Waldorf and Sudbury schools (Xu & Spruyt, Citation2022). Together with the movements of other non-traditional educational models, homeschooling in Chinese cities can be viewed as a counter current against the dominant discourse and practice of education in Chinese societies despite its relatively small scale.

In mainland China, homeschooling is not a legal option. The estimated number of families in mainland China who opted for homeschooling was approximately 6,000 in 2018 (Wang et al., Citation2018). Sheng (Citation2020) finds that some homeschooling families in Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou have chosen a Confucian reading course, Christian curriculum, or other forms of education for their children. Similarly, homeschooling is not legally regulated in Hong Kong – a Special Administrative Region (SAR) of China; thus, families are required by law to send their school-age children to school (Erlings, Citation2019). However, some better-off parents in Hong Kong have taken advantage of loopholes in the current legal framework which have allowed them to homeschool their children (Erlings, Citation2019). Given the absence of homeschooling regulations, no formal records of homeschoolers have been compiled in Hong Kong. According to a survey conducted in 2018 by the local homeschooling community, nearly 100 children were being homeschooled in Hong Kong, but this was believed to be a considerable underestimate (Sum, Citation2019). In a case study of one Chinese family in Hong Kong, Riley (Citation2016) documents how the family’s “unschooling” approach, as they described, allowed their child to follow her interests at her own pace. In contrast, Taipei, the capital of Taiwan, has been a pioneer in Chinese homeschooling movements since homeschooling in Taiwan was legalised in 1999. In 2014, three laws were promulgated in Taiwan, often labelled “Three Laws”, which applied to “non-school type experimental education”, “school-type experimental education”, and “public schools entrusted with private management” (Enforcement Act, Citation2018). These laws allow schools and non-school educators to try various kinds of experimental education (Chen, Citation2022). In 2020, an estimated 3,441 children were homeschooled in Taiwan (Home School Legal Defense Association, Citation2021). In Singapore, many Chinese homeschooling parents withdrawing their children from the mainstream school system emphasises elite education and hypercompetitive culture (Tan, Citation2020). Despite a limited amount of empirical work in the Chinese context (at least in English), Chinese homeschooling experiences may provide new perspectives for existing models, norms, and practices in formal school systems both regionally and globally.

Data and methods

The present study adopts a multi-site qualitative research design, primarily using semi-structured interviews, supplemented by family observations, to explore the perspectives and experiences of Chinese homeschooling families in two Chinese cities – Taipei and Hong Kong. The study was approved by the research ethics committee at the research team’s university. Using a snowball sampling strategy to reach out to typically inaccessible, secular Chinese homeschooling families (e.g. through professional networks and advocacy groups), the research team recruited 31 families in Taipei (n = 15) and Hong Kong (n = 16). Snowball sampling is a frequently used recruitment method in qualitative research to reach out to hard-to-reach populations; this method has strengths such as developing rapport with participants on a sensitive topic (Browne, Citation2005). The recruited families were local ethnic Chinese, with at least one school-aged child being homeschooled at the time of the interview. Interviews with mothers and/or fathers of the 31 families were conducted in person or via online meeting platforms (e.g. Zoom). Since mothers are traditionally the primary family caregivers and are often in charge of homeschooling (Lois, Citation2013), most interview respondents were mothers. Most of the families had both parents with a university degree and at least one parent working in a secure profession. presents the sociodemographic characteristics of parent participants in the two cities.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of parent participants in Hong Kong and Chinese Taipei (N = 31).

The interviews lasted one to two hours involving questions in eight broad categories, including child profiles, parents’ decision-making on homeschooling, regular homeschooling practices, obstacles encountered, parents’ values and philosophy on education, parents’ goals and expectations for their children, parents’ social networks and community ties, and parents’ formative histories. All the interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and translated from Chinese to English. To richly illuminate homeschooling experiences, the data collection was supplemented by further observations of actual homeschooling days and materials such as some homeschoolers’ study schedules, photographs, curriculum materials, and other supplementary materials collected from the respondents. Given the pandemic challenges and the related restrictions in both cities, not all but three families from the interview pool were willing to allow the research team to visit where their homeschooling activities frequently took place (i.e. the home or learning centre)Footnote2. During each visit, which lasted about one to three hours, the family was asked to offer a tour of their homeschooling environment and materials; interactions and informal conversations among parents and children were also observed. Observational fieldnotes and reflective memos were written as an integral part of data collection and documentation, offering contextual or confirming information to emerging themes of the homeschooling narratives derived from the analysis of interview data across all family cases.

Multiple sources of qualitative data consisting of the families’ detailed accounts of their homeschooling experiences solicited via interviews, observation, and nonverbal materials were organised, analysed, and triangulated using R-based Qualitative Data Analysis (RQDA) (Huang, Citation2016). The research team coded the textual data (e.g. interview transcripts) by undergoing an iterative process using both a priori and emergent coding frames to review, cross-check and refine codes, themes, and categories. Several theoretical pointers from the literature discussed earlier (e.g. main reasons for homeschooling and types of homeschooling activities) were used to develop an a priori coding framework addressing a range of thematic areas. The analysis involved generating codes, themes, and categories that were inductively derived from the data. Data was triangulated by linking and comparing the analysis of observational data to both the a priori and emerging themes and categories derived from the analysis of the interview data.

Findings

The findings are organised into four thematic questions according to the perspectives and practices of the homeschooling families in Taipei and Hong Kong: (i) Why did they choose to homeschool?; (ii) How did they organise homeschooling?; (iii) Who engaged in homeschooling?; and (iv) What did they do during the homeschooling? The first question centred around the aims and guiding ideals of education embraced by these families. The latter three questions were analysed using a framework of three intersecting dimensions of homeschooling practices: pedagogic organisation, pedagogic relations, and pedagogic materials.

Pedagogic aims and ideals: why did they choose to homeschool?

summarises the main reasons for homeschooling among the interviewed families in the two cities. Responses revealed parents’ dissatisfaction with mainstream schools and preference for non-traditional educational models (e.g. Montessori, Waldorf and Sudbury models) mostly fuelled their motivations to homeschool. Many parents were dissatisfied with the overall school system in the Chinese context (e.g. over-drilling for examinations, spoon-feeding, standardisation, inflexibility, and other oft-criticised approaches in Chinese education). For example, when asked why she chose homeschooling, a mother (HK01) made it very clear, “[It is] because the pupils I see today are less and less happy. The school system is getting more and more distorted, destroying our children’s learning motivation or ability, and taking their freedom away.” The remark made by a father of three (TP10) is another example to illustrate the rationale often held by the parents:

Mainstream schools often rely on cramming. After a long time of cramming, even when going to university, you would be used to being given answers by others. When we chose homeschooling or Montessori education, we wanted to emphasise children’s ability to think independently and solve problems. You don’t have to wait until college to learn abilities like doing independent study projects. If you can ask questions yourself and have the ability to find answers yourself, I think all these will help you a lot in the future.

Table 2. Main Reasons for Homeschooling (N = 31).

Pedagogic organisation: how did they organise homeschooling?

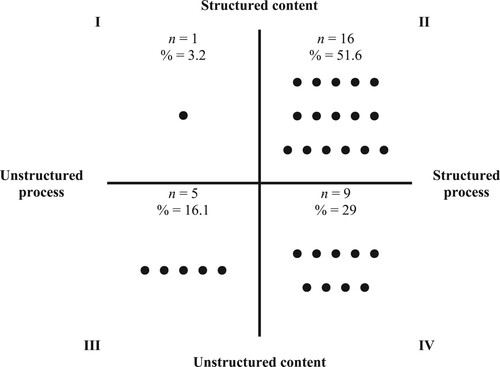

shows the diversity of the families’ typical practices in how homeschooling days were organised and mapped onto a spectrum between structured and unstructured learning approaches regarding processes (e.g. learning plans and procedures) and content (e.g. learning materials and settings) – a framework adapted from the findings of Neuman and Guterman’s (Citation2017) study in Israel. Examples of a structured approach were daily study schedules, pre-planned learning activities, and organised enrichment activities. An unstructured approach, however, allowed children to learn whatever they were interested in on their own time. While there was wide individual variation, just over half of the parents (51.6%) were inclined towards organising homeschooling activities closer to the structured end (“Type II” in ). One mother of three (HK03), running an education centre that her children frequently attended, explained:

A learning structure is essential, but on the other hand, the structure can’t be too detailed. I have a lesson plan for my children to learn different things every day. But I also leave some room for them to choose what they want to learn based on their interests. Never over-structure your child’s learning.

Pedagogic relations: who engaged in homeschooling?

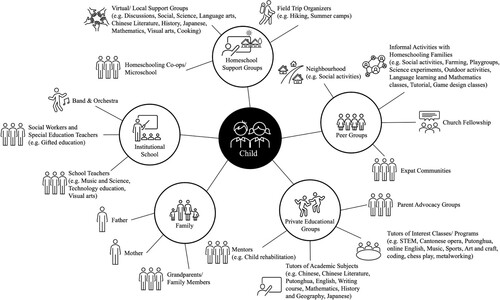

Among the participants from both cities, rather than simple learner-educator dyadic relations, multiple actors across at least five broad sectors and disciplines played a role in the process of homeschooling: the family, the institutional school, homeschool support groups, peer groups, and private educational groups (see ). The homeschooling experience involved multiple interactions among the homeschooled children, parents, instructors, peers, and the wider community. These interactions concerned the educational goals and plans, learning methods and activities, managing time, and progress in learning. Homeschoolers learned not just academically but socially. For example, a mother of two (TP03) explained:

I think in the real society, you do not always get along with people of the same age. So in fact, there are all kinds of friends of different ages in life. So getting to know and learn from friends of different age groups, and getting along with them is also very important.

Pedagogic materials: what did they do during the homeschooling?

illustrates how homeschooling families in the study used multiple educational resources, including conventional classroom learning, worksheets, pre-packaged curricula, reading, virtual learning, and everyday life lessons (e.g. volunteering and learning through living). A mother (HK01) described her strategies to offer a well-rounded education to her son:

To learn science, I bought children’s science series from Rightman Publishing. My son loves them. When he goes to the library, he mostly chooses science books or comics. We also cook together. As for sports, as he grows, he likes ice-skating, football, table tennis, badminton, roller, and different other sports. After age nine, we let him play video games for a limited time. He loves games like Minecraft and Brawl Stars. We often joined co-ops’ activities too. Also, we met “Uncle Danny” from “Forest Adventure”, a forest school up in the mountain. My son went there to play for two years. We joined the Waldorf group’s activities too.

Further, the parents stressed the need to create a good fit between schooling and their children’s personal and developmental needs. For example, a mother of three (TP01) said, “along the homeschooling journey, you could feel that learning depends on the child’s ability and development.” They explained that their children had unique needs at various stages of their emotional and intellectual development which prevented them from thriving in a single learning environment (e.g. an institutional school); thus, the parents believed that their homeschooling, which was rich in content and variety, fulfilled their children’s holistic development. For example, another mother of three (TP02) said, “I hope to return to the educational premise that everyone is different in nature, so that each child can have a suitable direction, resources and methods to grow.”

However, the parents did not completely reject mainstream schools. Rather, many hybridised their homeschooling practices and mainstream school practices. For example, a mother of two (TP05) explained:

My children’s learning of Mandarin and mathematics aligns with the pacing in regular schools, and the learning of other subjects is flexibly arranged by ourselves. My children would go to school to take monthly exams. The teacher is very nice. Although my children are homeschooled, the teacher would correct the homework they handed in. The teacher’s feedback is sufficient.

Differences in homeschooling narratives between Taipei and Hong Kong

While commonalities were evident in the narratives of homeschooling families in Taipei and Hong Kong, several differences did exist between these two Chinese cities, given their different social, legal, and institutional contexts. The decision to homeschool always required considerable thought among the respondents in both cities; however, the homeschooling choice involved heightened uncertainties for Hong Kong families due to the absence of homeschooling regulations and hence a lack of support from society at large. In Hong Kong cases, there was also a notable discord with mainstream schools; most parents prioritised their children’s individual pursuit of self-fulfilment. Comparatively, Taipei’s respondents often had connections with mainstream schools with more frequent mentions of civic responsibility and good citizenship. Furthermore, a larger proportion of Taipei families adopted a structured approach to homeschooling compared to their Hong Kong counterparts. This difference may have been because homeschooling in Taipei is highly institutionalised within a legal framework and the educational system there. While Hong Kong homeschooling families often collaborated with private schools and learning centres, many homeschooling families in Taipei incorporated the learning opportunities of public schools into their children’s larger educational journeys in life.

Discussion

The COVID-19 lockdown of schools, which posed unprecedented challenges to the traditional ways of running school education, provided the opportunity to re-assess what types of education are desired for the future (Sahlberg, Citation2021). Through the lens of Chinese homeschooling, the present study conveys a clear message that schools are essential; thus, the way forward should not entail any considerations of disestablishing schools as proposed by Illich (Citation1971) decades ago. Notably, the narratives of homeschooling families in this study offer useful insights into the future of school education, showing why, how, with whom, and what students learn.

Many respondents in this study had some shared vision with schools on the aims and guiding ideals of education (why students learn). As reflected in their main reasons to homeschool, they desired a personalised approach towards their children’s education. This aligns with the recent trend of school initiatives worldwide towards personsalisation, allowing each student to thrive based on their unique learning goals, attributes, and competencies (Sornson, Citation2018). In a similar vein, Rose (Citation2016) contends that to provide children with the same opportunities to achieve their full potential, education authorities must create an education system that treats children according to their unique characteristics (what Rose calls “equal fit”), rather than simply offering them equal access to educational opportunities. In this light, the educational pursuit of Chinese homeschoolers seems close to the concept of “equal fit.” This pursuit can be seen as an important challenge to the widely held belief in meritocracy and fairness about schooling, which is worth critical reflection in the post-pandemic era (Bradbury, Citation2021).

The next question, however, is how public or private schools can reimagine and transform themselves towards an education that is open to students’ personal needs and development. In light of pedagogic organisation (how students learn), many respondents’ homeschooling approach did not altogether dismiss the features of mainstream schooling such as its structured learning environment, subject-based curriculum, and performance-based assessment. In the same way, schools can learn from homeschooling families’ experiences to incorporate a variety of structured and unstructured approaches in learning content and processes (McShane, Citation2021).

To effectively hybridise structured and unstructured approaches in school education, it is crucial to extend our discussion to another question of pedagogic relations (with whom students learn). The findings of this study suggest that the family’s role can be repositioned closer to the centre of students’ education. Although it may be far-fetched to assume the family can become the centre of students’ education either in the Chinese school context or elsewhere as a new normal, joint responsibilities between families and schools regarding students’ learning time and space may be increasingly normalised (Fletcher et al., Citation2022). Schools can closely work with students’ families regarding students’ learning schedules. For example, students may spend less time at school to increase time for them to learn with their parents and other actors in non-school settings. To achieve this aim, educational policymakers may consider shortening the duration of each lesson leading to shorter days at school, or reducing weekly school days. A real example of this case can be found in a recent school policy change in Singapore. The Singapore Ministry of Education has introduced a blended learning initiative since 2021 that allows secondary schools and junior colleges to have a fortnightly home-based-learning day as a regular school policy to foster self-directed learning (Ng, Citation2022). In the US, there have also been discussions about moving from a five-to a four-day school week (Goldring, Citation2020). Although there is no strong evidence supporting either a positive or negative impact of a four-day week on academic achievement, recent research in the US shows that reduced weekly school time positively affects adolescents’ behaviour in school (Morton, Citation2023). Further, as the findings of this study imply, shortened school schedules, days or weeks, give students additional time to learn by themselves before or after school, or engage in learning activities initiated by cross-sectoral and cross-disciplinary teams from schools, families, and the wider community (e.g. parents, peers, community members, extramural tutors, and other professionals). To this end, instead of the mainstream, school-centric conception of parental involvement (e.g. only engaging parents/guardians in school activities or school-guided learning at home), school leaders and teachers need a significant shift not only in their thinking but in their actions regarding collaborations between schools, families and the wider community (Hill, Citation2022).

Such genuine school-family-community collaborations can significantly expand and diversify pedagogic materials (what students learn). In-school and home-based learning activities broaden the range of pedagogic approaches and learning materials as they are derived from multiple sources. As the findings clearly demonstrate, learning no longer takes place only within the confines of brick-and-mortar houses or schools. Thanks to the accelerating advance of online learning technologies during the COVID-19 pandemic, school-based and home-based/non-school-based learning modes have been diversified and hybridised in the light of pedagogic time, space, relations, and resources. During regular school days, for example, teachers can expand their existing flipped classroom practices by more frequently delivering learning materials online, allowing students to schedule their learning and facilitating discussion where students bring what they have learned at home and other non-school settings into the classroom. Under such an approach, students, perhaps mostly in higher grade levels, can have more flexibility and freedom regarding what and how they learn. In addition, schools may gradually find a way to make room for students of different grade levels to learn skills and knowledge in other contexts outside of regular school hours and space.

However, one impediment to expanding the family’s role in school education is likely to be the existing resource gap between the rich and the poor (Merry & Karsten, Citation2010). This may paradoxically jeopardise social justice that the “equal fit” model is presumed to bring about. Indeed, the present study shows that homeschooling families needed extensive financial and educational resources to satisfy their children’s personal needs in learning and development. Most respondents were well educated and appeared to have greater access to multiple resources useful for homeschooling. Therefore, the resource strategy of the public school financing system needs to be reinvented to alleviate the resource gap. Instead of the status quo where schools absorb all or most of the public funds, a portion of the public educational resources should be allotted to individual students and their families. The present study finds that some homeschooling families in Taipei received financial subsidies from the government. Thus, extending public funding to every student, regardless of their home-, public- or private-school status, needs to be considered. In addition to direct subsidies, there could be an option to offer a diverse range of discounted or free curriculum and instructional materials, publicly funded independent study programmes and distance learning programmes tailored to the specific needs of families, irrespective of their socio-economic backgrounds.

Conclusion

The present study revealed that Chinese homeschooling families in Taipei and Hong Kong chose to homeschool their children mainly because they were dissatisfied with mainstream schools, which, as they described, were mostly school-centric. Instead, the respondents embraced non-traditional education models to make their children’s education as child-centric as possible. The findings uncovered the ways that Chinese homeschooling families adopted highly diversified and hybridised strategies regarding pedagogic organisation, relations, and materials to fulfil their children’s unique needs. The analysis of the views and experiences of Chinese homeschooling families sets forth new perspectives for reimagining the future of school education, which exist near the centre of the homeschool-institutional school spectrum. Such new perspectives entail a significant shift in many assumptions underlying temporal, spatial, relational, and resource-related aspects of mainstream schooling.

Some limitations of this study should be noted. First, the views of the Chinese families presented in this article represent only a small sample and thus cannot be generalised to larger populations of homeschooling families who may have their own challenges in achieving their goals in practice (e.g. Fensham-Smith, Citation2021). As this article contends, however, the challenges and the criticisms unveiled in their narratives can be used to shed light on alternative conceptions for improving mainstream schools. Second, the findings should be interpreted with caution due to the potential respondent bias. In particular, the results were primarily derived from parents’ responses in the interviews, which might be biased due to social desirability, recall issues, and other subjective issues. To address this potential problem, the analysis was supplemented by other data sources, such as observations and non-verbal materials. Above all, one strength of this study is to provide an insider perspective and a context-specific understanding of how Chinese homeschooling families perceive, make sense of, and interpret their homeschooling models and practices.

Indeed, lessons learned from Chinese homeschooling families offer hope and imagination on school education for future generations particularly in the post-pandemic era. Building on the findings of the present study, future research might explore how socio-cultural factors shape homeschooling models and practices through a large-scale comparative analysis of homeschooling in different regions across the globe. Furthermore, little attention on the learner perspective in the existing literature (including the present study) might point researchers to another important direction for future research examining how homeschooled children from diverse backgrounds view and experience homeschooling.

Acknowledgements

The author wishes to thank the research assistants in Taipei and Hong Kong for assisting with the fieldwork involved in this study. He is also deeply grateful to all the generous research participants who donated their time. He would also like to thank three anonymous reviewers and the editor for commenting on earlier versions of this paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 One interviewed mother in the present study half-joked that the mode of home-based learning during COVID-19 should be called “lockdown schooling,” rather than homeschooling.

2 After obtaining informed consent for further observation from three families interviewed in Hong Kong, the research team visited the education centre (HK03) and the homes (HK09 and HK15) at the agreed-upon time. Unfortunately, no further observations were arranged for families in Taipei. The pandemic lockdowns made participant observation extremely difficult to arrange. Therefore, the research team had to adjust the fieldwork plan, e.g. scaling down the observation part. Strategies of flexibility and adaptation are often adopted in fieldwork research (Schoon, Citation2023).

References

- Apple, M. W. (2000). The cultural politics of home schooling. Peabody Journal of Education, 75(1-2), 256–271. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2000.9681944

- Bartholet, E. (2020). Homeschooling: Parent rights absolutism vs. child rights to education & protection. Arizona Law Review, 62(1), 1–80.

- Bond, M., Bergdahl, N., Mendizabal-Espinosa, R., Kneale, D., Bolan, F., Hull, P., & Ramadani, F. (2021). Global emergency remote education in secondary schools during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. EPPI Centre, UCL Social Research Institute, University College London.

- Bradbury, A. (2021). Ability, inequality and post-pandemic schools: Rethinking contemporary myths of meritocracy. Policy Press.

- Browne, K. (2005). Snowball sampling: Using social networks to research non-heterosexual women. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 47–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000081663

- Burke, K., & Cleaver, D. (2019). The art of home education: An investigation into the impact of context on arts teaching and learning in home education. Cambridge Journal of Education, 49(6), 771–788. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2019.1609416

- Carpenter, D., & Gann, C. (2016). Educational activities and the role of the parent in homeschool families with high school students. Educational Review, 68(3), 322–339. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2015.1087971

- Chen, C. C. (2022). Practice of leadership competencies by a principal: Case study of a public experimental school in Taiwan. Asia Pacific Education Review. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12564-022-09813-1

- Chen, J. (2015). Teachers’ conceptions of approaches to teaching: A Chinese perspective. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 24(2), 341–351. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-014-0184-3

- Cheng, A., & Hamlin, D. (2023). Contemporary homeschooling arrangements: An analysis of three waves of nationally representative data. Educational Policy, 37(5), 1444–1466. https://doi.org/10.1177/08959048221103795

- Cui, J., & Hanson, R. (2019). Homeschooling in the United States: Results from the 2012 and 2016 parent and family involvement survey (PFI-NHES: 2012 and 2016). Web Tables. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Dahlquist, K. L., York-Barr, L., & Hendel, D. D. (2006). The choice to homeschool: Home educator perspectives and school district options. Journal of School Leadership, 16(4), 354–385. https://doi.org/10.1177/105268460601600401

- Dwyer, J. G., & Peters, S. F. (2019). Homeschooling: The history and philosophy of a controversial practice. University of Chicago Press.

- Enforcement Act for Non-school-based Experimental Education at Senior High School Level or Below. (2018). https://law.moj.gov.tw/Eng/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?PCode=H0070059.

- Erlings, E. (2019). Don’t ask, do(n’t) tell: Homeschooling in Hong Kong. Asian Journal of Law and Society, 6(2), 307–319. https://doi.org/10.1017/als.2018.13

- Fensham-Smith, A. J. (2021). Invisible pedagogies in home education: Freedom, power and control. Journal of Pedagogy, 12(1), 5–27. https://doi.org/10.2478/jped-2021-0001

- Fletcher, J., Klopsch, B., Everatt, J., & Sliwka, A. (2022). Preparing student teachers post-pandemic: Lessons learnt from principals and teachers in New Zealand and Germany. Educational Review, 74(3), 609–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.2007053

- Gaither, M. (2016). The wiley handbook of home education. John Wiley & Sons.

- Gann, C., & Carpenter, D. (2019). STEM educational activities and the role of the parent in the home education of high school students. Educational Review, 71(2), 166–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1359149

- Goldring, R. (2020). Shortened school weeks in US public schools. Data point. NCES 2020-011. National Center for Education Statistics.

- Green-Hennessy, S., & Mariotti, E. C. (2023). The decision to homeschool: Potential factors influencing reactive homeschooling practice. Educational Review. Advance online publication, 75(4), 617–636. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1947196

- Greenwalt, K. (2019). Homeschooling in the United States. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.407

- Hamilton, L. B. (2022). Parent, child and state: Regulation in a new era of homeschooling. Journal of Law and Education, 51(2), 45–85. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4024629

- Hill, N. E. (2022). Parental involvement in education: Toward a more inclusive understanding of parents’ role construction. Educational Psychologist, 57(4), 309–314. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2022.2129652

- Hirsh, A. (2019). The changing landscape of homeschooling in the United States. Center on Reinventing Public Education.

- Home School Legal Defense Association. (2021, March 22). Homeschooling in Taiwan: A 2020 Recap. https://hslda.org/post/homeschooling-in-taiwan-a-2020-recap.

- Howell, C. (2013). Hostility or indifference? The marginalization of homeschooling in the education profession. Peabody Journal of Education, 88(3), 355–364. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2013.798510

- Huang, R. (2016). RQDA: R-based qualitative data analysis. R package version 0.2-8. http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org/.

- Illich, I. (1971). Deschooling society. Penguin.

- Isenberg, E. J. (2007). What have we learned about homeschooling? Peabody Journal of Education, 82(2-3), 387–409. https://doi.org/10.1080/01619560701312996

- Jolly, J. L., & Matthews, M. S. (2020). The shifting landscape of the homeschooling continuum. Educational Review, 72(3), 269–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1552661

- Kunzman, R. (2012). Education, schooling, and children’s rights: The complexity of homeschooling. Educational Theory, 62(1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2011.00436.x

- Kunzman, R., & Gaither, M. (2020). Homeschooling: An updated comprehensive survey of the research. Other Education: The Journal of Educational Alternative, 9(1), 253–336.

- Lee, T. T. (2022). Leadership for inclusive online learning in public primary schools during COVID-19: A multiple case study in Hong Kong. Educational Management Administration & Leadership. Advance online publication, https://doi.org/10.1177/17411432221135310

- Lim, L. (2020, Apr 15). How Covid-19 is changing the definition of ‘home-schooling’ – We are all doing it now. South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/magazines/post-magazine/short-reads/article/3079357/how-covid-19-changing-definition-home-schooling.

- Lois, J. (2013). Home is where the school is: The logic of homeschooling and the emotional labor of mothering. New York University Press.

- Lubienski, C. (2003). A critical view of home education. Evaluation & Research in Education, 17(2-3), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500790308668300

- Manca, F., & Meluzzi, F. (2020). Strengthening online learning when schools are closed: The role of families and teachers in supporting students during the COVID-19 crisis. OECD Policy Responses to Coronavirus (COVID-19). Paris: Secretary-General of the OECD. https://read.oecd-ilibrary.org/view/?ref=136_136615-o13(4bkowa&title=Strengthening-online-learning-when-schools-are-closed.

- Maxwell, N., Doughty, J., Slater, T., Forrester, D., & Rhodes, K. (2020). Home education for children with additional learning needs - a better choice or the only option? Educational Review, 72(4), 427–442. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2018.1532955

- Mayberry, M. (1989). Home-based education in the United States: Demographics, motivations and educational implications. Educational Review, 41(2), 171–180. https://doi.org/10.1080/0013191890410208

- McIntyre-Bhatty, K. (2008). Truancy and coercive consent: Is there an alternative? Educational Review, 60(4), 375–390. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131910802393407

- McShane, Q. M. (2021). Hybrid homeschooling: A guide to the future of education. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Merry, M. S., & Karsten, S. (2010). Restricted liberty, parental choice and homeschooling. Journal of Philosophy of Education, 44(4), 497–514. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9752.2010.00770.x

- Morton, E. (2023). Effects of 4-day school weeks on older adolescents: Examining impacts of the schedule on academic achievement, attendance, and behavior in high school. Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis. Advance online publication, 45(1), 52–78. https://doi.org/10.3102/01623737221097420

- Murphy, J. (2014). The social and educational outcomes of homeschooling. Sociological Spectrum, 34(3), 244–272. https://doi.org/10.1080/02732173.2014.895640

- Neuman, A. (2019). Criticism and education: Dissatisfaction of parents who homeschool and those who send their children to school with the education system. Educational Studies, 45(6), 726–741. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2018.1509786

- Neuman, A., & Aviram, A. (2003). Homeschooling as a fundamental change in lifestyle. Evaluation & Research in Education, 17(2-3), 132–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/09500790308668297

- Neuman, A., & Guterman, O. (2017). Structured and unstructured homeschooling: A proposal for broadening the taxonomy. Cambridge Journal of Education, 47(3), 355–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2016.1174190

- Neuman, A., & Oz, G. (2021). Different solutions to similar problems: Parents’ reasons for choosing to homeschool and social criticism of the education system. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 34(1), 37–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2020.1720852

- Ng, F. F. Y., & Wei, J. (2020). Delving into the minds of Chinese parents: What beliefs motivate their learning-related practices? Child Development Perspectives, 14(1), 61–67. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12358

- Ng, J. (2022, Sep 4). JC students in Raffles institution have four-day week. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/parenting-education/raffles-institution-jc-students-have-four-day-week.

- Ng, S. W. (2007). Development of parent– School partnerships in times of educational reform in Hong Kong. International Journal of Educational Reform, 16(4), 411–435. https://doi.org/10.1177/105678790701600406

- Ray, B. D. (2022). Homeschooling in the United States: Growth with diversity and more empirical evidence. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education, https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1643

- Ray, B. D., & Shakeel, M. D. (2023). Demographics are predictive of child abuse and neglect but homeschool versus conventional school is a non-issue: Evidence from a nationally representative survey. Journal of School Choice, 17(2), 176–213. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2022.2108879

- Reich, R. (2002). The civic perils of homeschooling. Educational Leadership, 59(7), 56–59.

- Reich, R. (2008). On regulating homeschooling: A reply to Glanzer. Educational Theory, 58(1), 17–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-5446.2007.00273.x

- Riley, G. (2016). Unschooling in Hong Kong: A case study. Journal of Unschooling and Alternative Learning, 10(20), 1–15.

- Rose, T. (2016). The end of average: How we succeed in a world that values sameness (1st ed.). Harper One, an imprint of Harper Collins Publishers.

- Sahlberg, P. (2021). Does the pandemic help us make education more equitable? Educational Research for Policy and Practice, 20(1), 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10671-020-09284-4

- Saiger, A. (2016). Homeschooling, virtual learning, and the eroding public/private binary. Journal of School Choice, 10(3), 297–319. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2016.1202070

- Schoon, E. W. (2023). Fieldwork disrupted: How researchers adapt to losing access to field sites. Sociological Methods & Research. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1177/00491241231156961

- Sheng, X. (2020). Home schooling in China: Culture, religion, politics, and gender. Routledge.

- Slater, E. V., Burton, K., & McKillop, D. (2022). Reasons for home educating in Australia: Who and why? Educational Review, 74(2), 263–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2020.1728232

- Sornson, B. (2018). Brainless sameness: The demise of one-size-fits-all instruction and the rise of competency based learning. Rowman & Littlefield.

- Sum, L. (2019, Apr 13). Home-schooling in Hong Kong: number of families opting out of system higher than thought, but do they risk running afoul of education authorities? South China Morning Post. https://www.scmp.com/news/hong-kong/education/article/3006014/home-schooling-hong-kong-number-families-opting-out-system.

- Tan, M. H. (2020). Homeschooling in Singaporean Chinese families: Beyond pedagogues and ideologues. Educational Studies, 46(2), 135–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2019.1584850

- Thompson, C. (2022). Homeschooling surge continues despite schools reopening. Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/covid-business-health-buffalo-education-d37f4f1d12e57b72e5ddf67d4f897d9a.

- Wang, J. J., Wang, B., & Wu, C. H. (2018). New trends in the development of ‘Homeschooling’ in China. In D. P. Yang (Ed.), Annual report on China’s education 2018 (pp. 291–305). Social Science Academic Press. [In Chinese].

- Wearne, E. (2019). A survey of families in a charter hybrid homeschool. Peabody Journal of Education, 94(3), 297–311. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2019.1617581

- West, R. L. (2009 Summer/Fall). The harms of homeschooling. Philosophy & Public Policy Quarterly, 29(3/4), 7–12. https://doi.org/10.13021/G8PPPQ.292009.104

- Xu, W., & Spruyt, B. (2022). ‘The road less travelled’: Towards a typology of alternative education in China. Comparative Education, 58(4), 434–450. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2022.2108615